After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

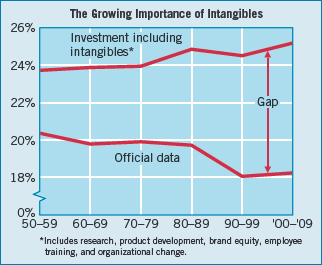

Gap Inc.'s most important asset is its brand image, not its store fixtures. The Coca-Cola Company's success comes from its secret formula for making Coca-Cola, not its plant facilities. America Online's subscriber base, not its Internet connection equipment, provides its most important asset. The U.S. economy is dominated by information and service providers. For these companies, their major assets are often intangible in nature.

What exactly are intangible assets? Intangible assets have two main characteristics. [1]

They lack physical existence. Tangible assets such as property, plant, and equipment have physical form. Intangible assets, in contrast, derive their value from the rights and privileges granted to the company using them.

They are not financial instruments. Assets such as bank deposits, accounts receivable, and long-term investments in bonds and stocks also lack physical substance. However, financial instruments derive their value from the right (claim) to receive cash or cash equivalents in the future. Financial instruments are not classified as intangibles.

In most cases, intangible assets provide benefits over a period of years. Therefore, companies normally classify them as long-term assets.

Following a discussion of the general valuation and accounting provisions for intangible assets, we present a more extensive discussion of the types of intangible assets and their accounting.

Companies record at cost intangibles purchased from another party. Cost includes all acquisition costs plus expenditures to make the intangible asset ready for its intended use. Typical costs include purchase price, legal fees, and other incidental expenses.

Sometimes companies acquire intangibles in exchange for stock or other assets. In such cases, the cost of the intangible is the fair value of the consideration given or the fair value of the intangible received, whichever is more clearly evident. What if a company buys several intangibles, or a combination of intangibles and tangibles? In such a "basket purchase," the company should allocate the cost on the basis of fair values. Essentially, the accounting treatment for purchased intangibles closely parallels that for purchased tangible assets.[164]

Sometimes a company may incur substantial research and development costs to create an intangible. For example, Google expensed the R&D costs incurred to develop its valuable search engine. Costs incurred internally to create intangibles are generally expensed.

How do companies justify this approach? Some argue that the costs incurred internally to create intangibles bear no relationship to their real value. Therefore, they reason, expensing these costs is appropriate. Others note that it is difficult to associate internal costs with a specific intangible. Still others contend that due to the underlying subjectivity related to intangibles, companies should follow a conservative approach—that is, expense as incurred. As a result, companies capitalize only direct costs incurred in developing the intangible, such as legal costs, and expense the rest.

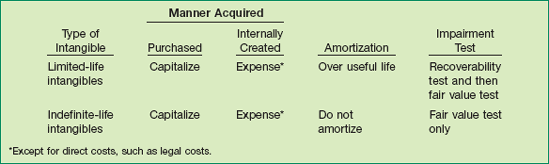

The allocation of the cost of intangible assets in a systematic way is called amortization. Intangibles have either a limited (finite) useful life or an indefinite useful life. For example, a company like Walt Disney has both types of intangibles. Walt Disney amortizes its limited-life intangible assets (e.g., copyrights on its movies and licenses related to its branded products). It does not amortize indefinite-life intangible assets (e.g., the Disney trade name or its Internet domain name).

Companies amortize their limited-life intangibles by systematic charges to expense over their useful life. The useful life should reflect the periods over which these assets will contribute to cash flows. Walt Disney, for example, considers these factors in determining useful life:

The expected use of the asset by the company.

The expected useful life of another asset or a group of assets to which the useful life of the intangible asset may relate (such as lease rights to a studio lot).

Any legal, regulatory, or contractual provisions that may limit the useful life.

Any provisions (legal, regulatory, or contractual) that enable renewal or extension of the asset's legal or contractual life without substantial cost. This factor assumes that there is evidence to support renewal or extension. Disney also must be able to accomplish renewal or extension without material modifications of the existing terms and conditions.

The effects of obsolescence, demand, competition, and other economic factors. Examples include the stability of the industry, known technological advances, legislative action that results in an uncertain or changing regulatory environment, and expected changes in distribution channels.

The level of maintenance expenditure required to obtain the expected future cash flows from the asset. For example, a material level of required maintenance in relation to the carrying amount of the asset may suggest a very limited useful life. [2]

The amount of amortization expense for a limited-life intangible asset should reflect the pattern in which the company consumes or uses up the asset, if the company can reliably determine that pattern. For example, assume that Second Wave, Inc. purchases a license to provide a specified quantity of a gene product, called Mega. Second Wave should amortize the cost of the license following the pattern of use of Mega. If Second Wave's license calls for it to provide 30 percent of the total the first year, 20 percent the second year, and 10 percent per year until the license expires, it would amortize the license cost using that pattern. If it cannot determine the pattern of production or consumption, Second Wave should use the straight-line method of amortization. (For homework problems, assume the use of the straight-line method unless stated otherwise.) When Second Wave amortizes these licenses, it should show the charges as expenses. It should credit either the appropriate asset accounts or separate accumulated amortization accounts.

The amount of an intangible asset to be amortized should be its cost less residual value. The residual value is assumed to be zero unless at the end of its useful life the intangible asset has value to another company. For example, if Hardy Co. commits to purchasing an intangible asset from U2D Co. at the end of the asset's useful life, U2D Co. should reduce the cost of its intangible asset by the residual value. Similarly, U2D Co. should consider fair values, if reliably determined, for residual values.

What happens if the life of a limited-life intangible asset changes? In that case the remaining carrying amount should be amortized over the revised remaining useful life. Companies should, on a regular basis, evaluate the limited-life intangibles for impairment. Similar to the accounting for property, plant, and equipment, an impairment loss should be recognized if the carrying amount of the intangible is not recoverable and its carrying amount exceeds its fair value. (We will cover impairment of intangibles in more detail later in the chapter.)

If no factors (legal, regulatory, contractual, competitive, or other) limit the useful life of an intangible asset, a company considers its useful life indefinite. An indefinite life means that there is no foreseeable limit on the period of time over which the intangible asset is expected to provide cash flows. A company does not amortize an intangible asset with an indefinite life. To illustrate, assume that Double Clik Inc. acquired a trademark that it uses to distinguish a leading consumer product. It renews the trademark every 10 years. All evidence indicates that this trademark product will generate cash flows for an indefinite period of time. In this case, the trademark has an indefinite life; Double Clik does not record any amortization.

Companies should test indefinite-life intangibles for impairment at least annually. As we will discuss in more detail later in the chapter, the impairment test for indefinite-life intangibles differs from the one for limited-life intangibles. Only the fair value test is performed for indefinite-life intangibles; there is no recoverability test for these intangibles. The reason: Indefinite-life intangible assets might never fail the undiscounted cash flows recoverability test because cash flows could extend indefinitely into the future.

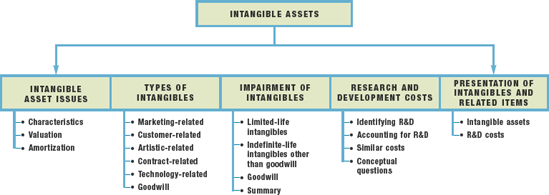

Illustration 12-1 summarizes the accounting treatment for intangible assets.

The importance of intangible asset classification as either limited-life or indefinite-life is illustrated in the experience of Outdoor Channel Holdings. Here's what happened: In 2004, Outdoor Channel recorded an intangible asset related to the value of an important distributor relationship, purchased from another company. At that time, it classified the relationship as indefinite-life. Thus, in 2004 and 2005 Outdoor Channel recorded no amortization expense on this asset. In 2006 investors were surprised to find that Outdoor Channel changed the classification of the distributor relationship to limited-life, with an expected life of 21.33 years (a fairly definite useful life) and, shortly after, wrote off this intangible completely.

Apparently, the company was overly optimistic about the expected future cash flows arising from the distributor relationship. As a result of that optimism, 2005 income was overstated by $9.5 million, or 14 percent, and the impairment recorded in 2006 amounted to 7 percent of 2005 year-end assets. From indefinite-life to limited-life to worthless in two short years—investors were surely hurt by Outdoor's aggressive intangible asset classification.

Source: Jack Ciesielski, The AAO Weblog, www.accountingobserver.com/blog/ (January 12, 2007).

As indicated, the accounting for intangible assets depends on whether the intangible has a limited or an indefinite life. There are many different types of intangibles, often classified into the following six major categories. [3]

Companies primarily use marketing-related intangible assets in the marketing or promotion of products or services. Examples are trademarks or trade names, newspaper mastheads, Internet domain names, and noncompetition agreements.

A trademark or trade name is a word, phrase, or symbol that distinguishes or identifies a particular company or product. Trade names like Kleenex, Pepsi-Cola, Buick, Excedrin, Wheaties, and Sunkist create immediate product identification in our minds, thereby enhancing marketability. Under common law, the right to use a trademark or trade name, whether registered or not, rests exclusively with the original user as long as the original user continues to use it. Registration with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office provides legal protection for an indefinite number of renewals for periods of 10 years each. Therefore a company that uses an established trademark or trade name may properly consider it to have an indefinite life and do not amortize its cost.

If a company buys a trademark or trade name, it capitalizes the cost at the purchase price. If a company develops a trademark or trade name, it capitalizes costs related to securing it, such as attorney fees, registration fees, design costs, consulting fees, and successful legal defense costs. However, it excludes research and development costs. When the total cost of a trademark or trade name is insignificant, a company simply expenses it.

The value of a marketing-related intangible can be substantial. Consider Internet domain names. The name Drugs.com at one time sold for $800,000. The bidding for the name Loans.com approached $500,000.

Company names themselves identify qualities and characteristics that companies work hard and spend much to develop. In a recent year an estimated 1,230 companies took on new names in an attempt to forge new identities and paid over $250 million to corporate-identity consultants. Among these were Primerica (formerly American Can), Navistar (formerly International Harvester), and Nissan (formerly Datsun).[165]

Or consider the use of the iPhone trade name. Cisco Systems sued Apple for using the iPhone trade name when Apple introduced its hot new phone in 2007. Not so fast, said Cisco, which had held the iPhone trade name since 2000 and was using it on its own voice-over-Internet products. The two companies came to an agreement for joint use of the name. It was not disclosed what Apple paid for this arrangement, but it is not surprising why Apple would want to settle—to avoid a costly delay to the launch of its highly anticipated iPhone.[166]

Customer-related intangible assets result from interactions with outside parties. Examples include customer lists, order or production backlogs, and both contractual and noncontractual customer relationships.

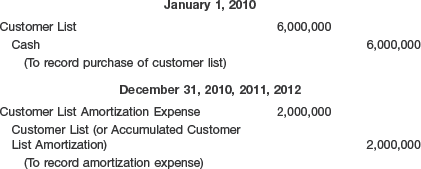

To illustrate, assume that Green Market Inc. acquires the customer list of a large newspaper for $6,000,000 on January 1, 2010. This customer database includes name, contact information, order history, and demographic information. Green Market expects to benefit from the information evenly over a three-year period. In this case, the customer list is a limited-life intangible that Green Market should amortize on a straight-line basis.

Green Market records the purchase of the customer list and the amortization of the customer list at the end of each year as follows.

The preceding example assumed no residual value for the customer list. But what if Green Market determines that it can sell the list for $60,000 to another company at the end of three years? In that case, Green Market should subtract this residual value from the cost in order to determine the amortization expense for each year. Amortization expense would be $1,980,000, as shown in Illustration 12-2.

Companies should assume a zero residual value unless the asset's useful life is less than the economic life and reliable evidence is available concerning the residual value. [4]

Artistic-related intangible assets involve ownership rights to plays, literary works, musical works, pictures, photographs, and video and audiovisual material. Copyrights protect these ownership rights.

A copyright is a federally granted right that all authors, painters, musicians, sculptors, and other artists have in their creations and expressions. A copyright is granted for the life of the creator plus 70 years. It gives the owner or heirs the exclusive right to reproduce and sell an artistic or published work. Copyrights are not renewable.

Copyrights can be valuable. In the late 1990s, Walt Disney Company faced the loss of its copyright on Mickey Mouse, which could have affected sales of billions of dollars of Mickey-related goods and services (including theme parks). This copyright was so important that Disney and many other big entertainment companies fought all the way to the Supreme Court—and won an extension of copyright lives from 50 to 70 years.

As another example, Really Useful Group owns copyrights on the musicals of Andrew Lloyd Webber—Cats, Phantom of the Opera, Jesus Christ-Superstar, and others. The company has little in the way of tangible assets, yet analysts value it at over $300 million.

Companies capitalize the costs of acquiring and defending a copyright. They amortize any capitalized costs over the useful life of the copyright if less than its legal life (life of the creator plus 70 years). For example, Really Useful Group should allocate the costs of its copyrights to the years in which it expects to receive the benefits. The difficulty of determining the number of years over which it will receive benefits typically encourages a company like Really Useful Group to write off these costs over a fairly short period of time. Companies must expense the research and development costs that lead to a copyright as those costs are incurred.

Contract-related intangible assets represent the value of rights that arise from contractual arrangements. Examples are franchise and licensing agreements, construction permits, broadcast rights, and service or supply contracts.

A franchise is a contractual arrangement under which the franchisor grants the franchisee the right to sell certain products or services, to use certain trademarks or trade names, or to perform certain functions, usually within a designated geographical area. We deal with franchises everyday: A Toyota dealer, a McDonald's restaurant, a Century 21 real estate broker, and a Marriott resort are all examples of franchises.

The franchisor, having developed a unique concept or product, protects its concept or product through a patent, copyright, or trademark or trade name. The franchisee acquires the right to exploit the franchisor's idea or product by signing a franchise agreement.

In another type of franchise arrangement, a municipality (or other governmental body) allows a privately owned company to use public property in performing its services. Examples are the use of public waterways for a ferry service, use of public land for telephone or electric lines, use of phone lines for cable TV, use of city streets for a bus line, or use of the airwaves for radio or TV broadcasting. Such operating rights, obtained through agreements with governmental units or agencies, are frequently referred to as licenses or permits.

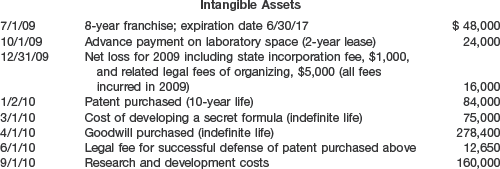

Franchises and licenses may be for a definite period of time, for an indefinite period of time, or perpetual. The company securing the franchise or license carries an intangible asset account (entitled Franchise or License) on its books, only when it can identify costs with the acquisition of the operating right. (Such costs might be legal fees or an advance lump-sum payment, for example.) A company should amortize the cost of a franchise (or license) with a limited life as operating expense over the life of the franchise. It should not amortize a franchise with an indefinite life nor a perpetual franchise; the company should instead carry such franchises at cost.

Annual payments made under a franchise agreement should be entered as operating expenses in the period in which they are incurred. These payments do not represent an asset since they do not relate to future rights to use the property.

Technology-related intangible assets relate to innovations or technological advances. Examples are patented technology and trade secrets granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

A patent gives the holder exclusive right to use, manufacture, and sell a product or process for a period of 20 years without interference or infringement by others. Companies such as Merck, Polaroid, and Xerox were founded on patents and built on the exclusive rights thus granted.[167] The two principal kinds of patents are product patents, which cover actual physical products, and process patents, which govern the process of making products.

If a company like Qualcomm purchases a patent from an inventor, the purchase price represents its cost. Qualcomm can capitalize other costs incurred in connection with securing a patent, as well as attorneys' fees and other unrecovered costs of a successful legal suit to protect the patent, as part of the patent cost. However, it must expense as incurred any research and development costs related to the development of the product, process, or idea that it subsequently patents. (We discuss accounting for research and development costs in more detail on pages 605–606.)

Companies should amortize the cost of a patent over its legal life or its useful life (the period in which benefits are received), whichever is shorter. If Qualcomm owns a patent from the date it is granted, and expects the patent to be useful during its entire legal life, the company should amortize it over 20 years. If it appears that the patent will be useful for a shorter period of time, say, for five years, it should amortize its cost over five years.

Changing demand, new inventions superseding old ones, inadequacy, and other factors often limit the useful life of a patent to less than the legal life. For example, the useful life of pharmaceutical patents is frequently less than the legal life because of the testing and approval period that follows their issuance. A typical drug patent has several years knocked off its 20-year legal life. Why? Because a drug-maker spends one to four years on animal tests, four to six years on human tests, and two to three years for the Food and Drug Administration to review the tests. All this time occurs after issuing the patent but before the product goes on pharmacists' shelves.

From bioengineering to software design to Wall Street, global competition is bringing to the boiling point battles over patents. For example, to protect its patented "one-click" shopping technology that saves your shipping and credit card information when you shop online, Amazon.com filed a complaint against Barnesandnoble.com, its rival in the Web-retailing wars. Amazon alleged infringement on its patent for one-click shopping. Similar patent skirmishes have sprung up on Wall Street. For example, eSpeed settled a dispute with several of the stock exchanges concerning the use of its patented computerized process for matching bids and offers on securities. Also, the Reuters Group sued Bloomberg over use of its automated trading technology. Although these companies have settled their disputes, patent battles continue amid ongoing debate over whether process patents held by companies like Amazon.com, eSpeed, and Reuters create an unfair competitive advantage.

Source: Adapted from L. Rohde, "Amazon, Barnes and Noble Settle Patent Dispute, CNN.com (March 8, 2002); and J. Creswell, "A Wall Street Rush to Patent Profit-Making Methods," New York Times, www.nytimes.com (August 11, 2006).

As mentioned earlier, companies capitalize the costs of defending copyrights. The accounting treatment for a patent defense is similar. A company charges all legal fees and other costs incurred in successfully defending a patent suit to Patents, an asset account. Such costs should be amortized along with acquisition cost over the remaining useful life of the patent.

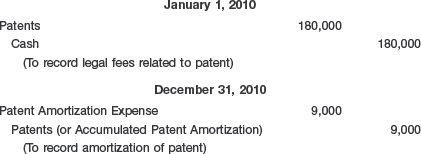

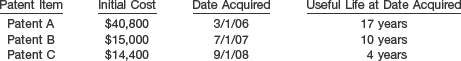

Amortization expense should reflect the pattern, if reliably determined, in which a company uses up the patent.[168] A company may credit amortization of patents directly to the Patents account or to an Accumulated Patent Amortization account. To illustrate, assume that Harcott Co. incurs $180,000 in legal costs on January 1, 2010, to successfully defend a patent. The patent's useful life is 20 years, amortized on a straight-line basis. Harcott records the legal fees and the amortization at the end of 2010 as follows.

We've indicated that a patent's useful life should not extend beyond its legal life of 20 years. However, companies often make small modifications or additions that lead to a new patent. For example, Astra Zeneca Plc filed for additional patents on minor modifications to its heartburn drug, Prilosec. The effect may be to extend the life of the old patent. If the new patent provides essentially the same benefits, Astra Zeneca can apply the unamortized costs of the old patent to the new patent.[169]

Alternatively, if a patent becomes impaired because demand drops for the product, the asset should be written down or written off immediately to expense.

After several espionage cases were uncovered, the secrets contained within the Los Alamos nuclear lab seemed easier to check out than a library book. But The Coca-Cola Company has managed to keep the recipe for the world's best-selling soft drink under wraps for more than 100 years. The company offers almost no information about its lifeblood, and the only written copy of the formula resides in a bank vault in Atlanta. This handwritten sheet is available to no one except by vote of Coca-Cola's board of directors.

Can't science offer some clues? Coke purportedly contains 17 to 18 ingredients. That includes the usual caramel color and corn syrup, as well as a blend of oils known as 7X (rumored to be a mix of orange, lemon, cinnamon, and others). Distilling natural products like these is complicated, since they are made of thousands of compounds. One ingredient you will not find, by the way, is cocaine. Although the original formula did contain trace amounts, today's Coke doesn't. When was it removed? That too is a secret.

Some experts indicate that the power of the Coca-Cola formula and related brand image account for almost $63 billion, or roughly 12 percent, of Coke's $538 billion stock value.

Source: Adapted from Reed Tucker, "How Has Coke's Formula Stayed a Secret?" Fortune (July 24, 2000), p. 42; and David Kiley, "Best Global Brands," BusinessWeek (August 6, 2007), p. 59.

Although companies may capitalize certain costs incurred in developing specifically identifiable assets such as patents and copyrights, the amounts capitalized are generally insignificant. But companies do record material amounts of intangible assets when purchasing intangible assets, particularly in situations involving a business combination (the purchase of another business).

To illustrate, assume that Portofino Company decides to purchase Aquinas Company. In this situation, Portofino measures the assets acquired and the liabilities assumed at fair value. In measuring these assets and liabilities, Portofino must identify all the assets and liabilities of Aquinas. As a result, Portofino may recognize some assets or liabilities not previously recognized by Aquinas. For example, Portofino may recognize intangible assets such as a brand name, patent, or customer list that were not recorded by Aquinas. In this case, Aquinas may not have recognized these assets because they were developed internally and charged to expense.[170]

In many business combinations, the purchasing company records goodwill. Goodwill is measured as the excess of the cost of the purchase over the fair value of the identifiable net assets (assets less liabilities) purchased. For example, if Portofino paid $2,000,000 to purchase Aquinas's identifiable net assets (with a fair value of $1,500,000), Portofino records goodwill of $500,000. Goodwill is therefore measured as a residual rather than measured directly. That is why goodwill is sometimes referred to as a plug, a gap filler, or a master valuation account.

Conceptually, goodwill represents the future economic benefits arising from the other assets acquired in a business combination that are not individually identified and separately recognized. It is often called "the most intangible of the intangible assets," because it is identified only with the business as a whole. The only way to sell goodwill is to sell the business.

Internally Created Goodwill. Goodwill generated internally should not be capitalized in the accounts. The reason? Measuring the components of goodwill is simply too complex, and associating any costs with future benefits is too difficult. The future benefits of goodwill may have no relationship to the costs incurred in the development of that goodwill. To add to the mystery, goodwill may even exist in the absence of specific costs to develop it. Finally, because no objective transaction with outside parties takes place, a great deal of subjectivity—even misrepresentation—may occur.

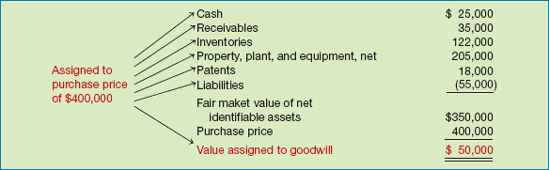

Purchased Goodwill. As indicated earlier, goodwill is recorded only when an entire business is purchased. To record goodwill, a company compares the fair value of the net tangible and identifiable intangible assets with the purchase price of the acquired business. The difference is considered goodwill. Goodwill is the residual—the excess of cost over fair value of the identifiable net assets acquired.

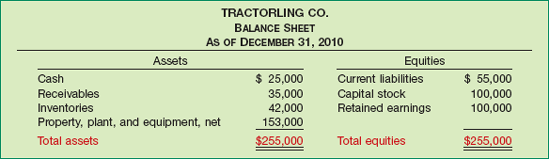

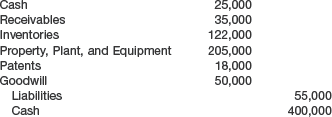

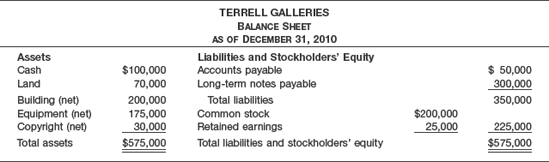

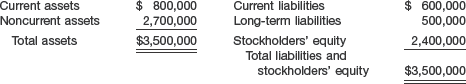

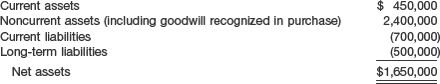

To illustrate, Multi-Diversified, Inc. decides that it needs a parts division to supplement its existing tractor distributorship. The president of Multi-Diversified is interested in buying Tractorling Company, a small concern in Chicago. Illustration 12-3 presents the balance sheet of Tractorling Company.

After considerable negotiation, Tractorling Company decides to accept Multi-Diversified's offer of $400,000. What, then, is the value of the goodwill, if any?

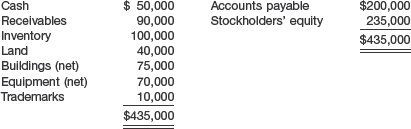

The answer is not obvious. Tractorling's historical cost-based balance sheet does not disclose the fair values of its identifiable assets. Suppose, though, that as the negotiations progress, Multi-Diversified investigates Tractorling's underlying assets to determine their fair values. Such an investigation may be accomplished either through a purchase audit undertaken by Multi-Diversified or by an independent appraisal from some other source. The investigation determines the valuations shown in Illustration 12-4.

Normally, differences between current fair value and book value are more common among long-term assets than among current assets. Cash obviously poses no problems as to value. Receivables normally are fairly close to current valuation, although they may at times need certain adjustments due to inadequate bad debt provisions. Liabilities usually are stated at book value. However, if interest rates have changed since the company incurred the liabilities, a different valuation (such as present value based on expected cash flows) is appropriate. Careful analysis must be made to determine that no unrecorded liabilities are present.

The $80,000 difference in Tractorling's inventories ($122,000 − $42,000) could result from a number of factors. The most likely is that the company uses LIFO. Recall that during periods of inflation, LIFO better matches expenses against revenues. However, it also creates a balance sheet distortion. Ending inventory consists of older layers costed at lower valuations.

In many cases, the values of long-term assets such as property, plant, and equipment, and intangibles may have increased substantially over the years. This difference could be due to inaccurate estimates of useful lives, continual expensing of small expenditures (say, less than $300), inaccurate estimates of salvage values, and the discovery of some unrecorded assets. (For example, in Tractorling's case, analysis determines Patents have a fair value of $18,000.) Or, fair values may have substantially increased.

Since the investigation now determines the fair value of net assets to be $350,000, why would Multi-Diversified pay $400,000? Undoubtedly, Tractorling points to its established reputation, good credit rating, top management team, well-trained employees, and so on. These factors make the value of the business greater than $350,000. Multi-Diversified places a premium on the future earning power of these attributes as well as on the basic asset structure of the company today.

Multi-Diversified labels the difference between the purchase price of $400,000 and the fair value of $350,000 as goodwill. Goodwill is viewed as one or a group of unidentifiable values (intangible assets), the cost of which "is measured by the difference between the cost of the group of assets or enterprise acquired and the sum of the assigned costs of individual tangible and identifiable intangible assets acquired less liabilities assumed."[171] This procedure for valuation is called a master valuation approach. It assumes goodwill covers all the values that cannot be specifically identified with any identifiable tangible or intangible asset. Illustration 12-5 (on the next page) shows this approach.

Multi-Diversified records this transaction as follows.

Companies often identify goodwill on the balance sheet as the excess of cost over the fair value of the net assets acquired.

Companies that recognize goodwill in a business combination consider it to have an indefinite life and therefore should not amortize it. Although goodwill may decrease in value over time, predicting the actual life of goodwill and an appropriate pattern of amortization is extremely difficult. In addition, investors find the amortization charge of little use in evaluating financial performance.

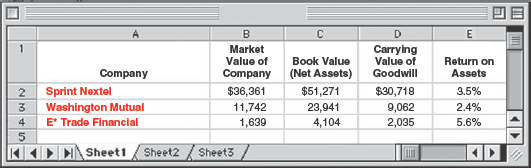

Furthermore, the investment community wants to know the amount invested in goodwill, which often is the largest intangible asset on a company's balance sheet. Therefore, companies adjust its carrying value only when goodwill is impaired. This approach significantly impacts the income statements of some companies.

Some believe that goodwill's value eventually disappears. Therefore, they argue, companies should charge goodwill to expense over the periods affected, to better match expense with revenues. Others note that the accounting treatment for purchased goodwill and goodwill created internally should be consistent. They point out that companies immediately expense goodwill created internally and should follow the same treatment for purchased goodwill. Though these arguments may have some merit, nonamortization of goodwill combined with an adequate impairment test should provide the most useful financial information to the investment community. We discuss the accounting for goodwill impairments later in the chapter.

In a few cases, the purchaser in a business combination pays less than the fair value of the identifiable net assets. Such a situation is referred to as a bargain purchase. A bargain purchase results from a market imperfection: That is, the seller would have been better off to sell the assets individually than in total. However, situations do occur (e.g., a forced liquidation or distressed sale due to the death of a company founder) in which the purchase price is less than the value of the net identifiable assets. This excess amount is recorded as a gain by the purchaser.

The FASB notes that an economic gain is inherent in a bargain purchase. The purchaser is better off by the amount by which the fair value of what is acquired exceeds the amount paid. Some expressed concern that some companies may attempt inappropriate gain recognition by making an intentional error in measurement of the assets or liabilities. As a result, the FASB requires companies to disclose the nature of this gain transaction. Such disclosure will help users to better evaluate the quality of the earnings reported.[172]

In some cases, the carrying amount of a long-lived asset (property, plant, and equipment or intangible assets) is not recoverable. Therefore, a company needs a write-off. As discussed in Chapter 11, this write-off is referred to as an impairment.

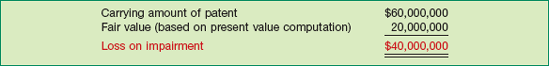

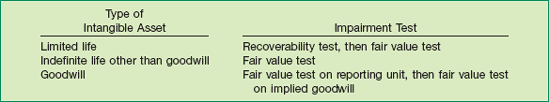

The rules that apply to impairments of property, plant, and equipment also apply to limited-life intangibles. As discussed in Chapter 11, a company should review property, plant, and equipment for impairment at certain points—whenever events or changes in circumstances indicate that the carrying amount of the assets may not be recoverable. In performing this recoverability test, the company estimates the future cash flows expected from use of the assets and its eventual disposal. If the sum of the expected future net cash flows (undiscounted) is less than the carrying amount of the asset, the company would measure and recognize an impairment loss. [8]

The company then uses the fair value test. This test measures the impairment loss by comparing the asset's fair value with its carrying amount. The impairment loss is the carrying amount of the asset less the fair value of the impaired asset. As with other impairments, the loss on the limited-life intangible is reported as part of income from continuing operations. The entry generally appears in the "Other expenses and losses" section.

To illustrate, assume that Lerch, Inc. has a patent on how to extract oil from shale rock. Unfortunately, several recent non-shale oil discoveries adversely affected the demand for shale-oil technology. Thus, the patent has provided little income to date. As a result, Lerch performs a recoverability test. It finds that the expected net future cash flows from this patent are $35 million. Lerch's patent has a carrying amount of $60 million. Because the expected future net cash flows of $35 million are less than the carrying amount of $60 million, Lerch must determine an impairment loss.

Discounting the expected net future cash flows at its market rate of interest, Lerch determines the fair value of its patent to be $20 million. Illustration 12-6 shows the impairment loss computation (based on fair value).

Lerch records this loss as follows:

After recognizing the impairment, the reduced carrying amount of the patents is its new cost basis. Lerch should amortize the patent's new cost over its remaining useful life or legal life, whichever is shorter. Even if shale-oil prices increase in subsequent periods and the value of the patent increases, Lerch may not recognize restoration of the previously recognized impairment loss.

Companies should test indefinite-life intangibles other than goodwill for impairment at least annually. The impairment test for an indefinite-life asset other than goodwill is a fair value test. This test compares the fair value of the intangible asset with the asset's carrying amount. If the fair value is less than the carrying amount, the company recognizes an impairment. Companies use this one-step test because many indefinite-life assets easily meet the recoverability test (because cash flows may extend many years into the future). Thus, companies do not use the recoverability test.

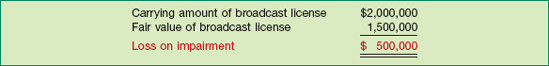

To illustrate, assume that Arcon Radio purchased a broadcast license for $2,000,000. The license is renewable every 10 years if the company provides appropriate service and does not violate Federal Communications Commission (FCC) rules. Arcon Radio has renewed the license with the FCC twice, at a minimal cost. Because it expects cash flows to last indefinitely, Arcon reports the license as an indefinite-life intangible asset. Recently the FCC decided to auction these licenses to the highest bidder instead of renewing them. Arcon Radio expects cash flows for the remaining two years of its existing license. It performs an impairment test and determines that the fair value of the intangible asset is $1,500,000. Arcon therefore reports an impairment loss of $500,000, computed as follows.

Arcon Radio now reports the license at $1,500,000, its fair value. Even if the value of the license increases in the remaining two years, Arcon may not restore the previously recognized impairment loss.

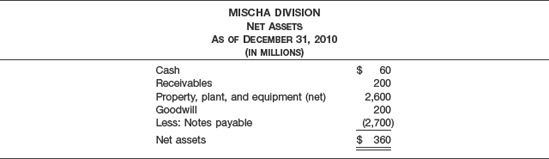

The impairment rule for goodwill is a two-step process. First, a company compares the fair value of the reporting unit to its carrying amount, including goodwill. If the fair value of the reporting unit exceeds the carrying amount, goodwill is not impaired. The company does not have to do anything else.

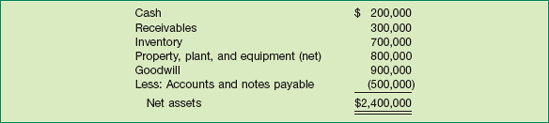

To illustrate, assume that Kohlbuy Corporation has three divisions. It purchased one division, Pritt Products, four years ago for $2 million. Unfortunately, Pritt experienced operating losses over the last three quarters. Kohlbuy management is now reviewing the division for purposes of recognizing an impairment. Illustration 12-8 lists the Pritt Division's net assets, including the associated goodwill of $900,000 from the purchase.

Kohlbuy determines that the fair value of Pritt Division is $2,800,000. Because the fair value of the division exceeds the carrying amount of the net assets, Kohlbuy does not recognize any impairment.

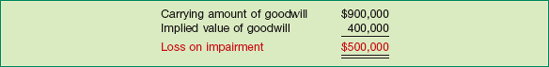

However, if the fair value of Pritt Division were less than the carrying amount of the net assets, then Kohlbuy would perform a second step to determine possible impairment. In the second step, Kohlbuy determines the fair value of the goodwill (implied value of goodwill) and compares it to its carrying amount. To illustrate, assume that the fair value of the Pritt Division is $1,900,000 instead of $2,800,000. Illustration 12-9 computes the implied value of the goodwill in this case.[173]

Kohlbuy then compares the implied value of the goodwill to the recorded goodwill to measure the impairment, as shown in Illustration 12-10.

Illustration 12-11 summarizes the impairment tests for various intangible assets.

Goodwill impairment issues have grabbed their share of business headlines. For example, Hewlett-Packard (H-P) received a fair amount of criticism for its failure to take impairment charges on goodwill arising from its merger with Compaq. H-P's chief financial officer acknowledged the issue, but played down its significance: "There's no question that if profitability doesn't improve, there will be an impairment charge."

Another example is Lee Enterprises Inc., owner of several major newspapers. Upon its acquisition of Pulitzer Inc. for $1.46 billion, Lee recorded additional goodwill; at the end of fiscal year 2007, it showed $1.6 billion of goodwill and other intangible assets. With things not going well in the newspaper business, some are waiting for "the other shoe to drop." The intangibles make up nearly 75 percent of Lee's total assets and Lee's book value (assets minus liabilities) and are about twice the company's current market value. Although no impairment had been recorded, the market seems to expect one is coming.

Lee's CFO indicates they will continue to evaluate these assets, and H-P's CFO makes the case that a goodwill impairment is no big deal. What do you think? Is an impairment charge just a bookkeeping entry, or can it provide some new information about the merits of H-P's merger with Compaq or Lee's acquisition of Pulitzer?

Source: Carol J. Loomis, "Why Carly's Big Bet Is Failing," Fortune (February 7, 2005), p. 50; and J. Weil, "Pulitzer's Owner Takes Prize of Frothy Numbers," www.bloomberg.com (January 9, 2008).

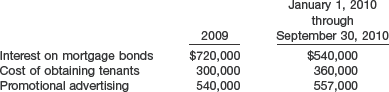

Research and development (R&D) costs are not in themselves intangible assets. However, we present the accounting for R&D costs here because R&D activities frequently result in the development of patents or copyrights (such as a new product, process, idea, formula, composition, or literary work) that may provide future value.

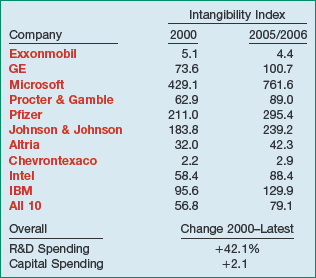

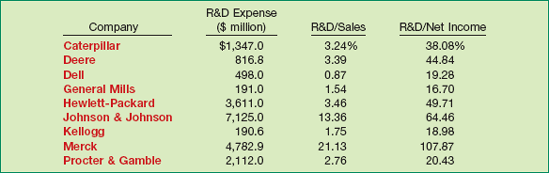

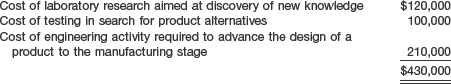

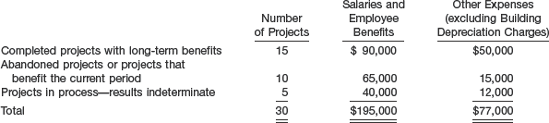

As indicated in the opening story, many companies spend considerable sums on research and development. Illustration 12-12 shows the outlays for R&D made by selected U.S. companies.

Two difficulties arise in accounting for R&D expenditures: (1) identifying the costs associated with particular activities, projects, or achievements, and (2) determining the magnitude of the future benefits and length of time over which such benefits may be realized. Because of these latter uncertainties, the FASB has simplified the accounting practice in this area. Companies must expense all research and development costs when incurred. [9]

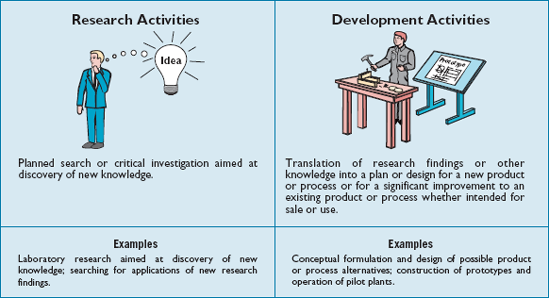

Illustration 12-13 shows the definitions for research activities and development activities. These definitions differentiate research and development costs from other similar costs. [10]

R&D activities do not include routine or periodic alterations to existing products, production lines, manufacturing processes, and other ongoing operations, even though these alterations may represent improvements. For example, routine ongoing efforts to refine, enrich, or improve the qualities of an existing product are not considered R&D activities.

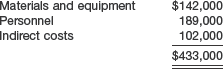

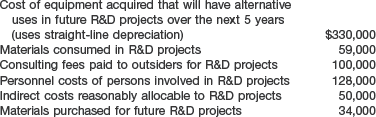

The costs associated with R&D activities and the accounting treatments accorded them are as follows.

Materials, Equipment, and Facilities. Expense the entire costs, unless the items have alternative future uses (in other R&D projects or otherwise). If there are alternative future uses, carry the items as inventory and allocate as consumed, or capitalize and depreciate as used.

Personnel. Expense as incurred salaries, wages, and other related costs of personnel engaged in R&D.

Purchased Intangibles. Recognize and measure at fair value. After initial recognition, account for in accordance with their nature (as either limited-life or indefinite-life intangibles).[174]

Contract Services. Expense the costs of services performed by others in connection with the R&D as incurred.

Indirect Costs. Include a reasonable allocation of indirect costs in R&D costs, except for general and administrative cost, which must be clearly related in order to be included in R&D. [12]

Consistent with item 1 above, if a company owns a research facility that conducts R&D activities and that has alternative future uses (in other R&D projects or otherwise), it should capitalize the facility as an operational asset. The company accounts for depreciation and other costs related to such research facilities as R&D expenses.[175]

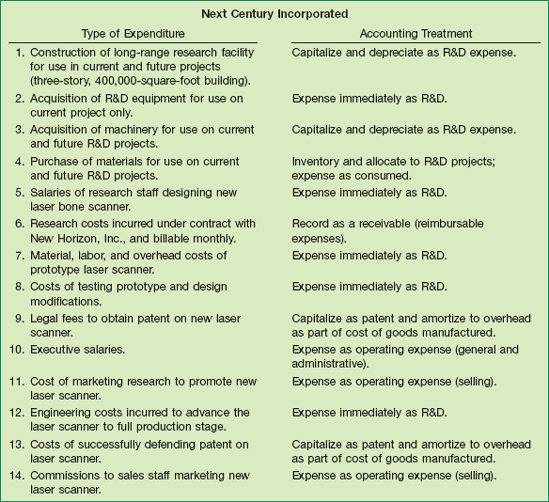

To illustrate, assume that Next Century Incorporated develops, produces, and markets laser machines for medical, industrial, and defense uses.[176] Illustration 12-14 (on the next page) lists the types of expenditures related to its laser-machine activities, along with the recommended accounting treatment.

Many costs have characteristics similar to research and development costs. Examples are:

For the most part, these costs are expensed as incurred, similar to the accounting for R&D costs. We briefly explain these costs in the following sections.

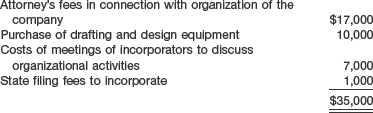

Start-up costs are incurred for one-time activities to start a new operation. Examples include opening a new plant, introducing a new product or service, or conducting business in a new territory. Start-up costs include organizational costs, such as legal and state fees incurred to organize a new business entity.

The accounting for start-up costs is straightforward: Expense start-up costs as incurred. The profession recognizes that companies incur start-up costs with the expectation of future revenues or increased efficiencies. However, to determine the amount and timing of future benefits is so difficult that a conservative approach—expensing these costs as incurred—is required. [14]

To illustrate examples of start-up costs, assume that U.S.-based Hilo Beverage Company decides to construct a new plant in Brazil. This represents Hilo's first entry into the Brazilian market. Hilo plans to introduce the company's major U.S. brands into Brazil, on a locally produced basis. The following costs might be involved:

Travel-related costs; costs related to employee salaries; and costs related to feasibility studies, accounting, tax, and government affairs.

Training of local employees related to product, maintenance, computer systems, finance, and operations.

Recruiting, organizing, and training related to establishing a distribution network.

Hilo Beverage should expense all these start-up costs as incurred.

Start-up activities commonly occur at the same time as activities involving the acquisition of assets. For example, as it is incurring start-up costs for the new plant, Hilo probably is also buying or building property, plant, equipment, and inventory. Hilo should not immediately expense the costs of these tangible assets. Instead, it should report them on the balance sheet using appropriate GAAP reporting guidelines.

Some contend that companies should be allowed to capitalize initial operating losses incurred in the start-up of a business. They argue that such operating losses are an unavoidable cost of starting a business.

For example, assume that Hilo lost money in its first year of operations and wishes to capitalize this loss. Hilo's CEO argues that as the company becomes profitable, it will offset these losses in future periods. What do you think? We believe that this approach is unsound, since losses have no future service potential and therefore cannot be considered an asset.

GAAP requires that operating losses during the early years should not be capitalized. In short, the accounting and reporting standards should be no different for an enterprise trying to establish a new business than they are for other enterprises. [15][177]

Over the years, PepsiCo has hired various pop stars, such as Justin Timberlake and Beyoncé, to advertise its products. How should it report such advertising costs related to its star spokespeople? Pepsi could expense the costs in various ways:

When they have completed their singing assignments.

The first time the advertising runs.

Over the estimated useful life of the advertising.

In an appropriate fashion to each of the three periods identified above.

Over the period revenues are expected to result.

For the most part, Pepsi must expense advertising costs as incurred or the first time the advertising takes place. Whichever of these two approaches is followed, the results are essentially the same. On the other hand, companies record as assets any tangible assets used in advertising, such as billboards or blimps. The rationale is that such assets do have alternative future uses. Again the profession has taken a conservative approach to recording advertising costs because defining and measuring the future benefits can be so difficult. [16][178]

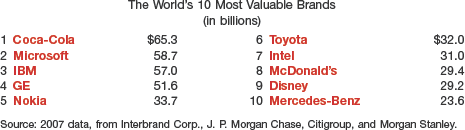

For many companies, developing a strong brand image is as important as developing the products they sell. Now more than ever, companies see the power of a strong brand, enhanced by significant and effective advertising investments.

As the following chart indicates, the value of brand investments is substantial. Coca-Cola heads the list with an estimated brand value of about $65 billion.

Occasionally you may find the value of a brand included in a company's financial statements under goodwill. But generally you will not find the estimated values of brands recorded in companies' balance sheets. The reason? The subjectivity that goes into estimating a brand's value. In some cases, analysts base an estimate of brand value on opinion polls or on some multiple of ad spending. For example, in estimating the brand values shown above, Interbrand Corp. estimates the percentage of the overall future revenues the brand will generate and then discounts the net cash flows, to arrive at a present value. Some analysts believe that information on brand values is relevant. Others voice valid concerns about the reliability of brand value estimates due to subjectivity in the estimates for revenues, costs, and the risk component of the discount rate.

Source: Adapted from David Kiley, "Best Global Brands," BusinessWeek (August 6, 2007), p. 59.

A special problem arises in distinguishing R&D costs from selling and administrative activities. The FASB's intent was that companies exclude from the definition of R&D activities the acquisition, development, or improvement of a product or process for use in their selling or administrative activities. For example, the costs of software incurred by an airline in improving its computerized reservation system, or the costs incurred in developing a company's management information system are not research and development costs.

Accounting for computer software costs is a specialized and complex accounting topic that we discuss and illustrate in Appendix 12A (pages 614–617).

The requirement that companies expense immediately all R&D costs (as well as start-up costs) incurred internally is a conservative, practical solution. It ensures consistency in practice and uniformity among companies. But the practice of immediately writing off expenditures made in the expectation of benefiting future periods is conceptually incorrect.

Proponents of immediate expensing contend that from an income statement standpoint, long-run application of this standard frequently makes little difference. They argue that because of the ongoing nature of most companies' R&D activities, the amount of R&D cost charged to expense each accounting period is about the same, whether there is immediate expensing or capitalization and subsequent amortization.

Others criticize this practice. They believe that the balance sheet should report an intangible asset related to expenditures that have future benefit. To preclude capitalization of all R&D expenditures removes from the balance sheet what may be a company's most valuable asset. This standard represents one of the many trade-offs made among relevance, reliability, and cost-benefit considerations.[179]

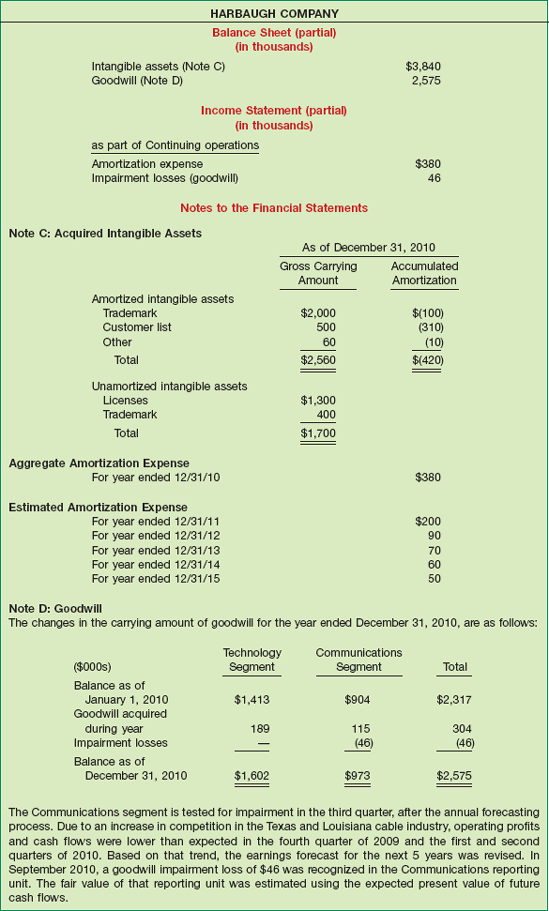

The reporting of intangible assets is similar to the reporting of property, plant, and equipment. However, contra accounts are not normally shown for intangibles on the balance sheet. As Illustration 12-15 (on page 610) shows, on the balance sheet companies should report as a separate item all intangible assets other than goodwill. If goodwill is present, companies should report it separately. The FASB concluded that since goodwill and other intangible assets differ significantly from other types of assets, such disclosure benefits users of the balance sheet.

On the income statement, companies should present amortization expense and impairment losses for intangible assets other than goodwill separately and as part of continuing operations. Again, see Illustration 12-15. Goodwill impairment losses should also be presented as a separate line item in the continuing operations section, unless the goodwill impairment is associated with a discontinued operation.

The notes to the financial statements should include information about acquired intangible assets, including the aggregate amortization expense for each of the succeeding five years. If separate accumulated amortization accounts are not used, accumulated amortization should be disclosed in the notes. The notes should include information about changes in the carrying amount of goodwill during the period.

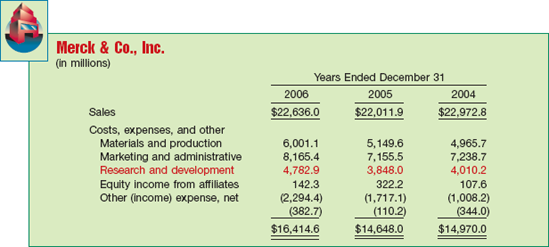

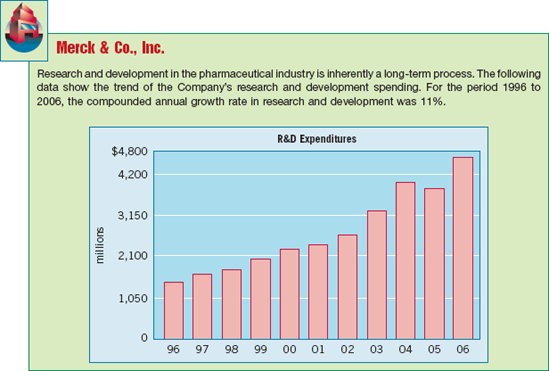

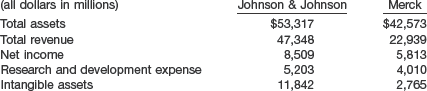

Companies should disclose in the financial statements (generally in the notes) the total R&D costs charged to expense each period for which they present an income statement. Merck & Co., Inc., a global research pharmaceutical company, reported both internal and acquired research and development in its recent income statement, as shown in Illustration 12-16.

In addition, Merck provides a discussion about R&D expenditures in its annual report, as shown in Illustration 12-17.

There are some significant differences between iGAAP and U.S. GAAP in the accounting for both intangible assets and impairments. iGAAP related to intangible assets is presented in IAS 38 ("Intangible Assets"). iGAAP related to impairments is found in IAS 36 ("Impairment of Assets").

As in U.S. GAAP, under iGAAP the costs associated with research and development are segregated into the two components. Costs in the research phase are always expensed under both iGAAP and U.S. GAAP. Under iGAAP, however, costs in the development phase are capitalized once technological feasibility is achieved.

iGAAP permits some capitalization of internally generated intangible assets (e.g., brand value), if it is probable there will be a future benefit and the amount can be reliably measured. U.S. GAAP requires expensing of all costs associated with internally generated intangibles.

iGAAP requires an impairment test at each reporting date for long-lived assets and intangibles and records an impairment if the asset's carrying amount exceeds its recoverable amount. The recoverable amount is the higher of the asset's fair value less costs to sell and its value in use. Value in use is the future cash flows to be derived from the particular assets, discounted to present value. Under U.S. GAAP, impairment loss is measured as the excess of the carrying amount over the asset's fair value.

iGAAP allows reversal of impairment losses when there has been a change in economic conditions or in the expected use of the asset. Under U.S. GAAP, impairment losses cannot be reversed for assets to be held and used; the impairment loss results in a new cost basis for the asset. iGAAP and U.S. GAAP are similar in the accounting for impairments of assets held for disposal.

With issuance of a recent converged statement on business combinations (IFRS 3 and SFAS No. 141—Revised), iGAAP and U.S. GAAP are very similar for intangibles acquired in a business combination. That is, companies recognize an intangible asset separately from goodwill if the intangible represents contractual or legal rights or is capable of being separated or divided and sold, transferred, licensed, rented, or exchanged. In addition, under both U.S. GAAP and iGAAP, companies recognize acquired in-process research and development (IPR&D) as a separate intangible asset if it meets the definition of an intangible asset and its fair value can be measured reliably.

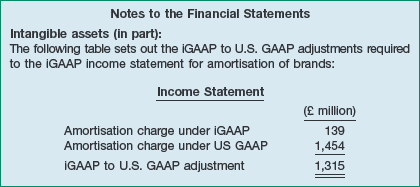

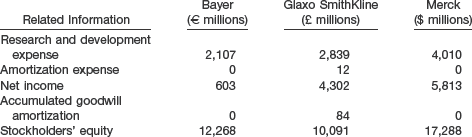

To illustrate the effect of differences in the accounting for brands, consider the following disclosure by GlaxoSmithKline plc in a recent annual report.

The IASB and FASB have identified a project that would consider expanded recognition of internally generated intangible assets. As indicated, iGAAP permits more recognition of intangibles compared to U.S. GAAP. Thus, it will be challenging to develop converged standards for intangible assets, given the long-standing prohibition on capitalizing internally generated intangible assets and research and development in U.S. GAAP. Learn more about the timeline for the intangible asset project at the IASB website: http://www.iasb.org/current+Projects/IASB+Projects/IASB+Work+Plan.htm.

Our economy is changing from a focus on manufacturing processes (tangible outputs) to a focus on information flow (intangible outputs). As a result, the accounting for computer software products becomes increasingly important.[180] This appendix discusses the basic issues involved in accounting for computer software.

Companies can either purchase computer software or create it. They may purchase or create software for external use (such as spreadsheet applications like Excel or Lotus 1-2-3) or for internal use (e.g., to establish a better internal accounting system).

How should companies account for the costs of developing software? Should they expense such costs immediately, or capitalize and amortize them in the future? At one time, some companies expensed all software costs, and others capitalized such costs. Still others differentiated such costs on the basis of whether the software was purchased or created, or whether it was used for external or internal purposes.

Another major question is whether the costs involved in developing software are research and development costs. If they are actually R&D costs, then companies should expense them as incurred. If they are not R&D costs, then a strong case can be made for capitalization. As one financial executive of a software company, who argues for capitalization, noted, "The key distinction between our spending and R&D is recoverability. We know we are developing something we can sell."

In an attempt to resolve the issue of how to account for software (at least for companies that sell computer software), the FASB issued the following rules. [17]

In short, the FASB has taken a conservative position in regard to computer software costs. For example, a company like Microsoft must expense all costs until it has completed the activities (planning, designing, coding, and testing) necessary to establish that it can produce the product to meet its design specifications. From that point on, Microsoft should capitalize subsequently incurred costs and amortize them to current and future periods.

Two additional points: First, if Microsoft purchases software and it has alternative future uses, then it may be capitalized. Second, this standard applies only to the development of software that is to be sold, leased, or otherwise marketed to third parties (i.e., for external use).

The profession has also indicated how to account for software to be used internally. Activities performed during the preliminary project stage of development (e.g., conceptual formulation and evaluation of alternatives) are similar to R&D costs. Companies should expense such costs immediately. Once the software is at the application development stage (e.g., at the coding or installation stages), its future economic benefits become probable. At that point, companies must capitalize the software costs. Finally, subsequent to the application development stage, costs related to training and application maintenance should be expensed as incurred. [18]

If companies are to capitalize software costs, then they must establish a proper amortization pattern for such costs. As a basis for amortization, one of two amounts is used: (1) the ratio of current revenues to current and anticipated revenues (the percent-of-revenue approach), or (2) the straight-line method over the remaining useful life of the asset (straight-line approach). A company must use whichever of these amounts is greater. This rule can result in the use of the percent-of-revenue method one year and the straight-line method in another.[181]

To illustrate, assume that AT&T has capitalized software costs of $10 million, and current (first-year) revenues from sales of this product of $4 million. AT&T anticipates earning $16 million in additional future revenues from this product; it estimates that the product has an economic life of four years. Under the two approaches, the calculations are as follows for the first year's amortization:

Percent-of-revenue approach:

Straight-line approach:

Thus AT&T uses the straight-line approach because it results in the greater amortization charge.

How reliable is software as an asset? Because of this concern, the FASB indicated that companies should value capitalized software costs at the lower of unamortized cost (book value) or net realizable value. If net realizable value is lower, then companies should write down the capitalized software costs to this value. Once companies have written down the costs, they may not write them back up.

In addition to the regular disclosures for R&D costs, companies should report in the financial statements the following information relating to software.

Unamortized software costs.

The total amount charged to expense and the amounts, if any, written down to net realizable value.

Again, these accounting and reporting requirements apply only to software developed for external purposes.

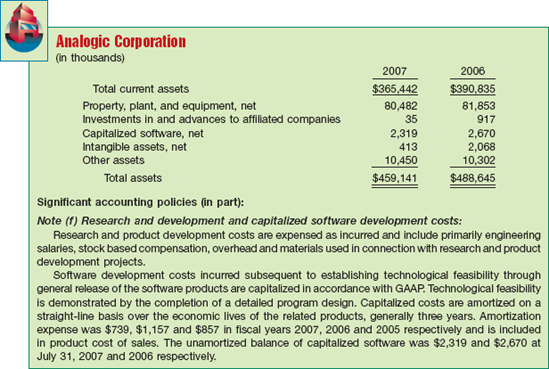

Illustration 12A-1 presents an example of software development cost disclosure, taken from the annual report of Analogic Corporation.

"It's unreasonable to expense all software costs, and it's unreasonable to capitalize all software costs," said IBM's director of financial reporting. "If you subscribe to those two statements, then it follows that there is somewhere in between where development ends and capitalization begins. Now you have to define that point."[182] The FASB defined that point as technological feasibility, which is established upon completion of a detailed program design or a working model.

The difficulty of applying this criterion to software is that "there is no such thing as a real, specific, baseline design. But you could make it look like you have one as early or as late as you like," says Osman Eralp of Hambrecht & Quist.[183] That is, if a company wishes to capitalize, it draws up a detailed program design quickly. If it wants to expense lots of development costs, it simply holds off writing a detailed program design. And, once capitalized, the costs are amortized over the useful life specified by the developer. Because of either constant redesign or supersession, software's useful life is generally quite short (two to four years).

As another example, some companies "manage by the numbers." That is, they are very careful to identify projects that are worthwhile and capitalize the computer software costs associated with them. They believe that good projects must be capitalized and amortized in the future; otherwise, the concept of properly matching expense and revenues is abused.

In contrast, other companies choose not to manage by the numbers. They simply expense all development costs. Companies that expense all these costs have no use for a standard that requires capitalization. In their view, it would mean only that they would need a more complex, more expensive cost accounting system, which would provide little if any benefit.

Financial analysts have reacted almost uniformly against any capitalization of software costs. They believe such costs should be expensed because of the rapid obsolescence of software and the potential for abuse that may result from capitalizing costs inappropriately. As Donald Kirk, a former chairman of the FASB, stated, "The Board is now faced with the problem of balancing what it thought was good theory with the costs for some companies of implementing a new accounting system with the concerns of users about the potential for abuse of the standard."[184]

The accounting for software development costs has been addressed in the authoritative literature. However, some of the issues debated may arise again, if accounting standard-setters propose expanded capitalization of development costs beyond those related to software. Such a debate is likely if the FASB converges to iGAAP, which permits expanded capitalization of development costs compared to U.S. GAAP.

SUMMARY OF LEARNING OBJECTIVE FOR APPENDIX 12A

FASB Codification References

FASB ASC 350-10-05. [Predecessor literature: "Goodwill and Other Intangible Assets," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 142 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2001).]

FASB ASC 350-30-35. [Predecessor literature: "Goodwill and Other Intangible Assets," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 142 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2001) par. 11.]

FASB ASC 805-10. [Predecessor literature: "Business Combinations," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 141R (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2007).]

FASB ASC 350-30-35. [Predecessor literature: "Goodwill and Other Intangible Assets," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 142 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2001), par. B55.]

FASB ASC 805-10-20. [Predecessor literature: "Business Combinations," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 141R (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2007).]

FASB ASC 805-10-30. [Predecessor literature: "Business Combinations," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 141R (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2007).]

FASB ASC 805-10-30. [Predecessor literature: "Business Combinations," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 141R (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2007).]

FASB ASC 360-10-05. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for the Impairment or Disposal of Long-lived Assets," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 144 (Norwalk, Conn.: 2001).]

FASB ASC 735-10-25-1. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Research and Development Costs," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 2 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1974), par. 12.]

FASB ASC Master Glossary. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Research and Development Costs," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 2 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1974), par. 8.]

FASB ASC 805-10. [Predecessor literature: "Business Combinations," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 141–Revised (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2007), par. E11.]

FASB ASC 730-10-25-2. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Research and Development Costs," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 2 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1974), par. 11.]

FASB ASC 730-20-05. [Predecessor literature: "Research and Development Arrangements," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 68 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1982).]

FASB ASC 720-15-25. [Predecessor literature: "Reporting on the Costs of Start-up Activities," Statement of Position 98-5 (New York: AICPA, 1998).]

FASB ASC 915-205-45-1. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting and Reporting by Development Stage Enterprises," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 7 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1975), par. 10.]

FASB ASC 720-35-05-3. [Predecessor literature: "Reporting on Advertising Costs," Statement of Position 93-7 (New York: AICPA, 1993).]

FASB ASC 985-20-05 [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for the Cost of Computer Software to Be Sold, Leased, or Otherwise Marketed," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 86 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1985).]

FASB ASC 350-10-05. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for the Costs of Computer Software Developed or Obtained for Internal Use," Statement of Position 98-1 (New York: AICPA, 1998).]

Note: All asterisked Questions, Exercises, and Problems relate to material in the appendices to the chapter.

What are the two main characteristics of intangible assets?

If intangibles are acquired for stock, how is the cost of the intangible determined?

Intangibles have either a limited useful life or an indefinite useful life. How should these two different types of intangibles be amortized?

Why does the accounting profession make a distinction between internally created intangibles and purchased intangibles?

In 2010 Ghostbusters Corp. spent $420,000 for "goodwill" visits by sales personnel to key customers. The purpose of these visits was to build a solid, friendly relationship for the future and to gain insight into the problems and needs of the companies served. How should this expenditure be reported?

What are factors to be considered in estimating the useful life of an intangible asset?

What should be the pattern of amortization for a limited-life intangible?

Columbia Sportswear Company acquired a trademark that is helpful in distinguishing one of its new products. The trademark is renewable every 10 years at minimal cost. All evidence indicates that this trademark product will generate cash flows for an indefinite period of time. How should this trademark be amortized?

McNabb Company spent $190,000 developing a new process, $45,000 in legal fees to obtain a patent, and $91,000 to market the process that was patented, all in the year 2010. How should these costs be accounted for in 2010?

Izzy Inc. purchased a patent for $350,000 which has an estimated useful life of 10 years. Its pattern of use or consumption cannot be reliably determined. Prepare the entry to record the amortization of the patent in its first year of use.

Explain the difference between artistic-related intangible assets and contract-related intangible assets.

What is goodwill? What is negative goodwill?

Under what circumstances is it appropriate to record goodwill in the accounts? How should goodwill, properly recorded on the books, be written off in order to conform with generally accepted accounting principles?

In examining financial statements, financial analysts often write off goodwill immediately. Comment on this procedure.

Braxton Inc. is considering the write-off of a limited life intangible because of its lack of profitability. Explain to the management of Braxton how to determine whether a write-off is permitted.

Last year Zeno Company recorded an impairment on an intangible asset held for use. Recent appraisals indicate that the asset has increased in value. Should Zeno record this recovery in value?

Explain how losses on impaired intangible assets should be reported in income.

Simon Company determines that its goodwill is impaired. It finds that its implied goodwill is $360,000 and its recorded goodwill is $400,000. The fair value of its identifiable assets is $1,450,000. What is the amount of goodwill impaired?

What is the nature of research and development costs?

Research and development activities may include (a) personnel costs, (b) materials and equipment costs, and (c) indirect costs. What is the recommended accounting treatment for these three types of R&D costs?

Which of the following activities should be expensed currently as R&D costs?

Testing in search for or evaluation of product or process alternatives.

Engineering follow-through in an early phase of commercial production.

Legal work in connection with patent applications or litigation, and the sale or licensing of patents.

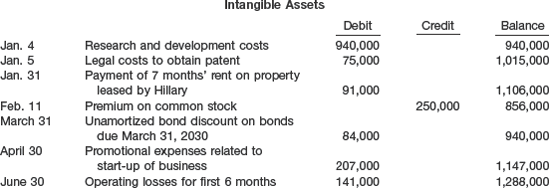

Indicate the proper accounting for the following items.

Organization costs.

Advertising costs.

Operating losses.

In 2009, Austin Powers Corporation developed a new product that will be marketed in 2010. In connection with the development of this product, the following costs were incurred in 2009: research and development costs $400,000; materials and supplies consumed $60,000; and compensation paid to research consultants $125,000. It is anticipated that these costs will be recovered in 2012. What is the amount of research and development costs that Austin Powers should record in 2009 as a charge to expense?

Recently, a group of university students decided to incorporate for the purposes of selling a process to recycle the waste product from manufacturing cheese. Some of the initial costs involved were legal fees and office expenses incurred in starting the business, state incorporation fees, and stamp taxes. One student wishes to charge these costs against revenue in the current period. Another wishes to defer these costs and amortize them in the future. Which student is correct?

An intangible asset with an estimated useful life of 30 years was acquired on January 1, 2000, for $540,000. On January 1, 2010, a review was made of intangible assets and their expected service lives, and it was determined that this asset had an estimated useful life of 30 more years from the date of the review. What is the amount of amortization for this intangible in 2010?

* An article in the financial press stated, "More than half of software maker Comserve's net worth is in a pile of tapes and ring-bound books. That raises some accountants' eyebrows." What is the profession's position regarding the incurrence of costs for computer software that will be sold?

* Garfunkel, Inc. has incurred $6 million in developing a computer software product for sale to third parties. Of the $6 million costs incurred, $4.5 million is capitalized. The product produced from this development work has generated $2 million of revenue in 2010 and is anticipated to generate another $8 million in future years. The estimated useful life of the project is 4 years. How much of the capitalized costs should be amortized in 2010?

* In 2010, EZ-Learn Software developed a software package for assisting calculus instruction in business colleges, at a cost of $2,000,000. Although there are tens of thousands of calculus students in the market, college instructors seem to change their minds frequently on the use of teaching aids. Not one package has yet been ordered or delivered. Prepare an argument to advocate expensing the development cost in the current year. Offer an argument for capitalizing the development cost over its estimated useful life. Which stakeholders are harmed or benefited by either approach?

Prepare the necessary 2010 journal entry or entries for Treasure Land.

Purchase cost of a patent from a competitor.

Research and development costs.

Organizational costs.

Costs incurred internally to create goodwill.

Investment in a subsidiary company.

Timberland.

Cost of engineering activity required to advance the design of a product to the manufacturing stage.

Lease prepayment (6 months' rent paid in advance).

Cost of equipment obtained.

Cost of searching for applications of new research findings.

Costs incurred in the formation of a corporation.

Operating losses incurred in the start-up of a business.

Training costs incurred in start-up of new operation.

Purchase cost of a franchise.

Goodwill generated internally.

Cost of testing in search for product alternatives.

Goodwill acquired in the purchase of a business.

Cost of developing a patent.

Cost of purchasing a patent from an inventor.

Legal costs incurred in securing a patent.

Unrecovered costs of a successful legal suit to protect the patent.

Cost of conceptual formulation of possible product alternatives.

Cost of purchasing a copyright.

Research and development costs.

Long-term receivables.

Cost of developing a trademark.

Cost of purchasing a trademark.

Instructions

Indicate which items on the list above would generally be reported as intangible assets in the balance sheet.

Indicate how, if at all, the items not reportable as intangible assets would be reported in the financial statements.

Cable television franchises

Film contract rights

Music copyrights

Customer lists

Research and development costs

Prepaid expenses

Goodwill

Covenants not to compete

Cash

Brand names

Discount on notes payable

Notes receivable

Accounts receivable

Investments in affiliated companies

Property, plant, and equipment

Organization costs

Internet domain name

Land

Instructions

Identify which items should be classified as an intangible asset. For those items not classified as an intangible asset, indicate where they would be reported in the financial statements.

Organization costs

$24,000

Trademarks

20,000

Discount on bonds payable

35,000

Deposits with advertising agency for ads to promote goodwill of company

10,000

Excess of cost over fair value of net identifiable assets of acquired subsidiary

75,000

Cost of equipment acquired for research and development projects; the equipment has an alternative future use

90,000

Costs of developing a secret formula for a product that is expected to be marketed for at least 20 years

70,000

Instructions

On the basis of the information above, compute the total amount to be reported by Langrova for intangible assets on its balance sheet at December 31, 2010. Equipment has alternative future use.

If an item is not to be included in intangible assets, explain its proper treatment for reporting purposes.

Palmiero purchased a patent from Vania Co. for $1,500,000 on January 1, 2008. The patent is being amortized over its remaining legal life of 10 years, expiring on January 1, 2018. During 2010, Palmiero determined that the economic benefits of the patent would not last longer than 6 years from the date of acquisition. What amount should be reported in the balance sheet for the patent, net of accumulated amortization, at December 31, 2010?

Palmiero bought a franchise from Dougherty Co. on January 1, 2009, for $350,000. The carrying amount of the franchise on Dougherty's books on January 1, 2009, was $500,000. The franchise agreement had an estimated useful life of 30 years. Because Palmiero must enter a competitive bidding at the end of 2018, it is unlikely that the franchise will be retained beyond 2018. What amount should be amortized for the year ended December 31, 2010?

On January 1, 2008, Palmiero incurred organization costs of $275,000. What amount of organization expense should be reported in 2010?