LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Accounting alternatives diminish the comparability of financial information between periods and between companies; they also obscure useful historical trend data. For example, if Ford revises its estimates for equipment useful lives, depreciation expense for the current year will not be comparable to depreciation expense reported by Ford in prior years. Similarly, if Best Buy changes to FIFO inventory pricing while Circuit City uses LIFO, it will be difficult to compare these companies' reported results. A reporting framework helps preserve comparability when there is an accounting change.

The FASB has established a reporting framework, which involves three types of accounting changes. [1] The three types of accounting changes are:

Change in Accounting Principle. A change from one generally accepted accounting principle to another one. For example, a company may change its inventory valuation method from LIFO to average cost.

Change in Accounting Estimate. A change that occurs as the result of new information or additional experience. For example, a company may change its estimate of the useful lives of depreciable assets.

Change in Reporting Entity. A change from reporting as one type of entity to another type of entity. As an example, a company might change the subsidiaries for which it prepares consolidated financial statements.

A fourth category necessitates changes in accounting, though it is not classified as an accounting change.

Errors in Financial Statements. Errors result from mathematical mistakes, mistakes in applying accounting principles, or oversight or misuse of facts that existed when preparing the financial statements. For example, a company may incorrectly apply the retail inventory method for determining its final inventory value.

The FASB classifies changes in these categories because each category involves different methods of recognizing changes in the financial statements. In this chapter we discuss these classifications. We also explain how to report each item in the accounts and how to disclose the information in comparative statements.

By definition, a change in accounting principle involves a change from one generally accepted accounting principle to another. For example, a company might change the basis of inventory pricing from average cost to LIFO. Or it might change its method of revenue recognition for long-term construction contracts from the completed-contract to the percentage-of-completion method.

Companies must carefully examine each circumstance to ensure that a change in principle has actually occurred. Adoption of a new principle in recognition of events that have occurred for the first time or that were previously immaterial is not an accounting change. For example, a change in accounting principle has not occurred when a company adopts an inventory method (e.g., FIFO) for newly acquired items of inventory, even if FIFO differs from that used for previously recorded inventory. Another example is certain marketing expenditures that were previously immaterial and expensed in the period incurred. It would not be considered a change in accounting principle if they become material and so may be acceptably deferred and amortized.

Finally, what if a company previously followed an accounting principle that was not acceptable? Or what if the company applied a principle incorrectly? In such cases, the profession considers a change to a generally accepted accounting principle a correction of an error. For example, a switch from the cash (income tax) basis of accounting to the accrual basis is a correction of an error. Or, if a company deducted salvage value when computing double-declining depreciation on plant assets and later recomputed depreciation without deducting estimated salvage value, it has corrected an error.

There are three possible approaches for reporting changes in accounting principles:

Report changes currently. In this approach, companies report the cumulative effect of the change in the current year's income statement as an irregular item. The cumulative effect is the difference in prior years' income between the newly adopted and prior accounting method. Under this approach, the effect of the change on prior years' income appears only in the current-year income statement. The company does not change prior-year financial statements.

Advocates of this position argue that changing prior years' financial statements results in a loss of confidence in financial reports. How do investors react when told that the earnings computed three years ago are now entirely different? Changing prior periods, if permitted, also might upset contractual arrangements based on the old figures. For example, profit-sharing arrangements computed on the old basis might have to be recomputed and completely new distributions made, creating numerous legal problems. Many practical difficulties also exist: The cost of changing prior-period financial statements may be excessive, or determining the amount of the prior-period effect may be impossible on the basis of available data. Report changes retrospectively. Retrospective application refers to the application of a different accounting principle to recast previously issued financial statements— as if the new principle had always been used. In other words, the company "goes back" and adjusts prior years' statements on a basis consistent with the newly adopted principle. The company shows any cumulative effect of the change as an adjustment to beginning retained earnings of the earliest year presented.

Advocates of this position argue that retrospective application ensures comparability. Think for a moment what happens if this approach is not used: The year previous to the change will be on the old method; the year of the change will report the entire cumulative adjustment; and the following year will present financial statements on the new basis without the cumulative effect of the change. Such lack of consistency fails to provide meaningful earnings-trend data and other financial relationships necessary to evaluate the business.

Report changes prospectively (in the future). In this approach, previously reported results remain. As a result, companies do not adjust opening balances to reflect the change in principle. Advocates of this position argue that once management presents financial statements based on acceptable accounting principles, they are final; management cannot change prior periods by adopting a new principle. According to this line of reasoning, the current-period cumulative adjustment is not appropriate, because that approach includes amounts that have little or no relationship to the current year's income or economic events.

Given these three possible approaches, which does the accounting profession prefer? The FASB requires that companies use the retrospective approach. Why? Because it provides financial statement users with more useful information than the cumulative-effect or prospective approaches. [2] The rationale is that changing the prior statements to be on the same basis as the newly adopted principle results in greater consistency across accounting periods. Users can then better compare results from one period to the next.[399]

The cumulative-effect approach results in a loss of comparability. Also, reporting the cumulative adjustment in the period of the change can significantly affect net income, resulting in a misleading income figure. For example, at one time Chrysler Corporation changed its inventory accounting from LIFO to FIFO. If Chrysler had used the cumulative-effect approach, it would have reported a $53,500,000 adjustment to net income. That adjustment would have resulted in net income of $45,900,000, instead of a net loss of $7,600,000.

A second case: In the early 1980s the railroad industry switched from the retirement-replacement method of depreciating railroad equipment to more generally used methods such as straight-line depreciation. Using cumulative treatment, railroad companies would have made substantial adjustments to income in the period of change. Many in the industry argued that including such large cumulative-effect adjustments in the current year would distort the information and make it less useful.

Such situations lend support to retrospective application so that comparability is maintained.

A presumption exists that once a company adopts an accounting principle, it should not change. That presumption is understandable, given the idea that consistent use of an accounting principle enhances the usefulness of financial statements. However, the environment continually changes, and companies change in response. Recent standards on such subjects as stock options, exchanges of non-monetary assets, and derivatives indicate that changes in accounting principle will continue to occur.

When a company changes an accounting principle, it should report the change using retrospective application. In general terms, here is what it must do:

It adjusts its financial statements for each prior period presented. Thus, financial statement information about prior periods is on the same basis as the new accounting principle.

It adjusts the carrying amounts of assets and liabilities as of the beginning of the first year presented. By doing so, these accounts reflect the cumulative effect on periods prior to those presented of the change to the new accounting principle. The company also makes an offsetting adjustment to the opening balance of retained earnings or other appropriate component of stockholders' equity or net assets as of the beginning of the first year presented.

For example, assume that Target decides to change its inventory valuation method in 2010 from the retail inventory method (FIFO) to the retail inventory (average cost). It provides comparative information for 2008 and 2009 based on the new method. Target would adjust its assets, liabilities, and retained earnings for periods prior to 2008 and report these amounts in the 2008 financial statements, when it prepares comparative financial statements.

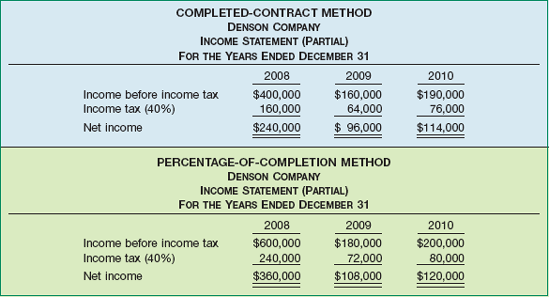

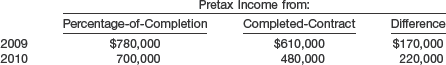

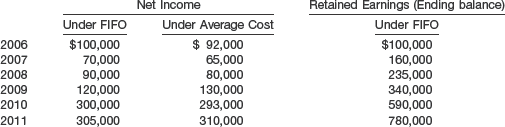

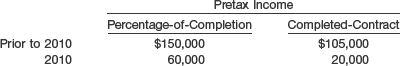

To illustrate the retrospective approach, assume that Denson Company has accounted for its income from long-term construction contracts using the completed-contract method. In 2010 the company changed to the percentage-of-completion method. Management believes this approach provides a more appropriate measure of the income earned. For tax purposes, the company uses the completed-contract method and plans to continue doing so in the future. (We assume a 40 percent enacted tax rate.)

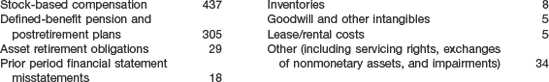

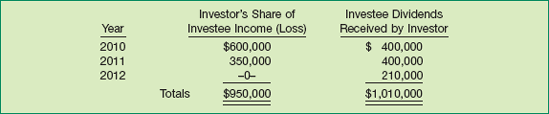

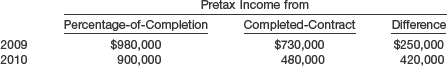

Illustration 22-1 shows portions of three income statements for 2008–2010—for both the completed-contract and percentage-of-completion methods.

Figure 22-1. Comparative Income Statements for Completed-Contract versus Percentage-of-Completion Methods

To record a change from the completed-contract to the percentage-of-completion method, we analyze the various effects, as Illustration 22-2 shows.

The entry to record the change at the beginning of 2010 would be:

The Construction in Process account increases by $220,000 (as indicated in the first column under "Difference in Income" in Illustration 22-2). The credit to Retained Earnings of $132,000 reflects the cumulative income effects prior to 2010 (third column under "Difference in Income" in Illustration 22-2). The company credits Retained Earnings because prior years' income is closed to this account each year. The credit to Deferred Tax Liability represents the adjustment to prior years' tax expense. The company now recognizes that amount, $88,000, as a tax liability for future taxable amounts. That is, in future periods, taxable income will be higher than book income as a result of current temporary differences. Therefore, Denson must report a deferred tax liability in the current year.

Halliburton offers a case study in the importance of good reporting of an accounting change. Recall from Chapter 18 that Halliburton uses percentage-of-completion accounting for its long-term construction-services contracts. Recently, the SEC questioned the company about its change in accounting for disputed claims.

Prior to 1998 Halliburton took a very conservative approach to its accounting for disputed claims. That is, the company waited until all disputes were resolved before recognizing associated revenues. In contrast, in 1998 the company recognized revenue for disputed claims before their resolution, using estimates of amounts expected to be recovered. Such revenue and its related profit are more tentative and subject to possible later adjustment. The accounting method adopted in 1998 is more aggressive than the company's former policy but is within the boundaries of GAAP.

It appears that the problem with Halliburton's accounting stems more from how the company handled its accounting change than from the new method itself. That is, Halliburton did not provide in its 1998 annual report an explicit reference to its change in accounting method. In fact, rather than stating its new policy, the company simply deleted the sentence that described how it accounted for disputed claims. Then later, in its 1999 annual report, the company stated its new accounting policy.

When companies make such changes in accounting, investors need to be informed about the change and about its effects on the financial results. With such information, investors and analysts can compare current results with those of prior periods and can make a more informed assessment about the company's future prospects.

Source: Adapted from "Accounting Ace Charles Mulford Answers Accounting Questions," Wall Street Journal Online (June 7, 2002).

Reporting a Change in Principle. The disclosure of accounting changes is particularly important. Users of the financial statements want consistent information from one period to the next. Such consistency ensures the usefulness of financial statements. The major disclosure requirements are as follows.

The nature of and reason for the change in accounting principle. This must include an explanation of why the newly adopted accounting principle is preferable.

The method of applying the change, and:

A description of the prior-period information that has been retrospectively adjusted, if any.

The effect of the change on income from continuing operations, net income (or other appropriate captions of changes in net assets or performance indicators), any other affected line item, and any affected per-share amounts for the current period and for any prior periods retrospectively adjusted.

The cumulative effect of the change on retained earnings or other components of equity or net assets in the statement of financial position as of the beginning of the earliest period presented.[400]

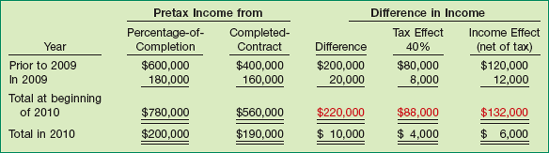

To illustrate, Denson will prepare comparative financial statements for 2009 and 2010 using the percentage-of-completion method (the new-construction accounting method). Illustration 22-3 (on page 1187) indicates how Denson presents this information.

As Illustration 22-3 shows, Denson Company reports net income under the newly adopted percentage-of-completion method for both 2009 and 2010. The company retrospectively adjusted the 2009 income statement to report the information on a percentage-of-completion basis. Also, the note to the financial statements indicates the nature of the change, why the company made the change, and the years affected.

In addition, companies are required to provide data on important differences between the amounts reported under percentage-of-completion versus completed-contract. When identifying the significant differences, some companies show the entire financial statements and line-by-line differences between percentage-of-completion and completed-contract. However, most companies will show only line-by-line differences. For example, Denson would show the differences in construction in process, retained earnings, gross profit, and net income for 2009 and 2010 under the completed-contract and percentage-of-completion methods.

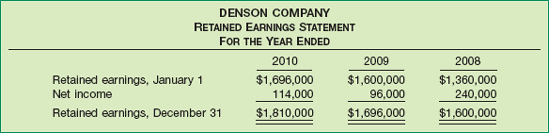

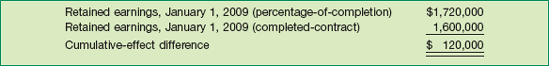

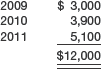

Retained Earnings Adjustment. As indicated earlier, one of the disclosure requirements is to show the cumulative effect of the change on retained earnings as of the beginning of the earliest period presented. For Denson Company, that date is January 1, 2009. Denson disclosed that information by means of a narrative description (see Note A in Illustration 22-3). Denson also would disclose this information in its retained earnings statement. Assuming a retained earnings balance of $1,360,000 at the beginning of 2008, Illustration 22-4 shows Denson's retained earnings statement under the completed-contract method—that is, before giving effect to the change in accounting principle. (The income information comes from Illustration 22-1 on page 1185.)

If Denson presents comparative statements for 2009 and 2010 under percentage-of-completion, then it must change the beginning balance of retained earnings at January 1, 2009. The difference between the retained earnings balances under completed-contract and percentage-of-completion is computed as follows.

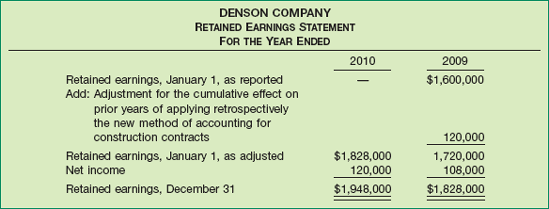

The $120,000 difference is the cumulative effect. Illustration 22-5 shows a comparative retained earnings statement for 2009 and 2010, giving effect to the change in accounting principle to percentage-of-completion.

Denson adjusted the beginning balance of retained earnings on January 1, 2009, for the excess of percentage-of-completion net income over completed-contract net income in 2008. This comparative presentation indicates the type of adjustment that a company needs to make. It follows that this adjustment would be much larger if a number of prior periods were involved.

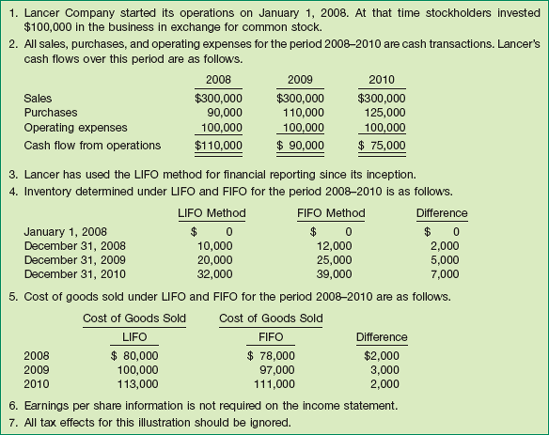

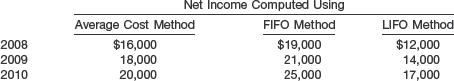

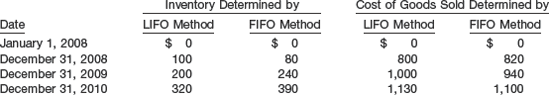

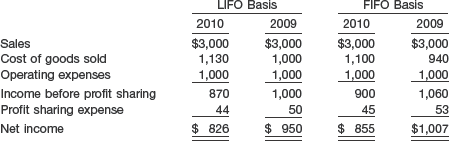

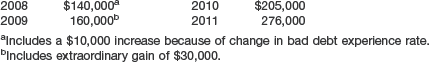

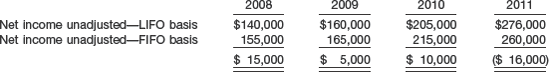

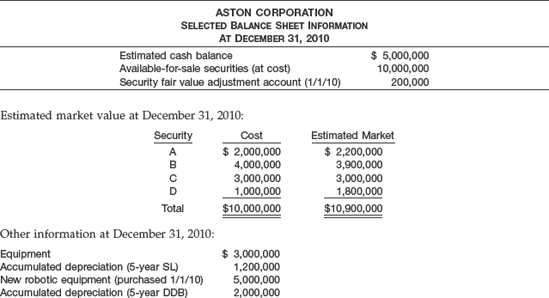

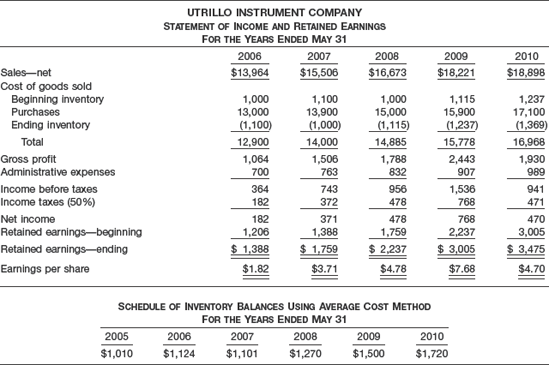

As a second illustration of the retrospective approach, assume that Lancer Company has accounted for its inventory using the LIFO method. In 2010, the company changes to the FIFO method because management believes this approach provides a more appropriate measure of its inventory costs. Illustration 22-6 provides additional information related to Lancer Company.

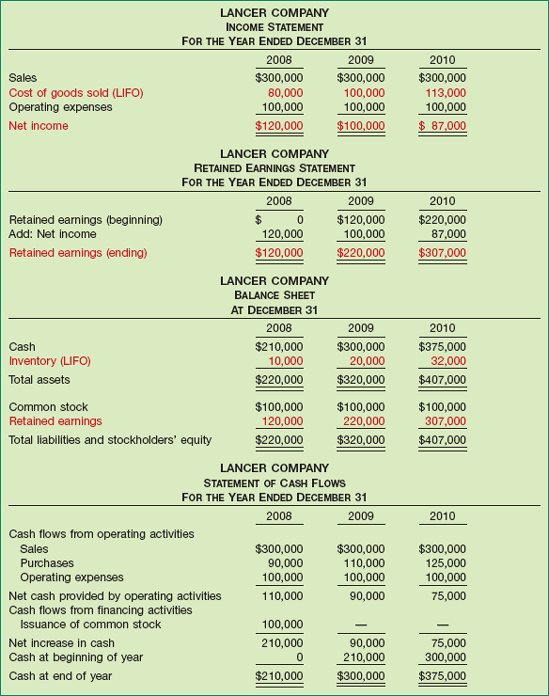

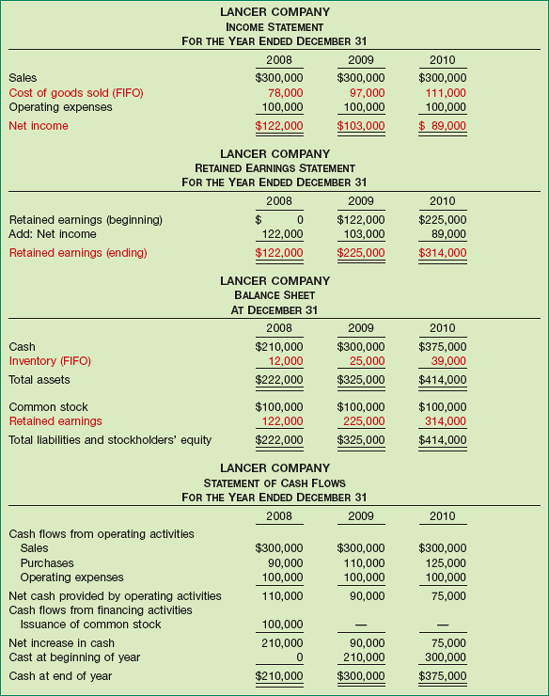

Given the information about Lancer Company, Illustration 22-7 shows its income statement, retained earnings statement, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows for 2008–2010 under LIFO.

As Illustration 22-7 indicates, under LIFO Lancer Company reports $120,000 net income in 2008, $100,000 net income in 2009, and $87,000 net income in 2010. The amount of inventory reported on Lancer's balance sheet reflects LIFO costing.

Illustration 22-8 shows Lancer's income statement, retained earnings statement, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows for 2008–2010 under FIFO. You can see that the cash flow statement under FIFO is the same as under LIFO. Although the net incomes are different in each period, there is no cash flow effect from these differences in net income. (If we considered income taxes, a cash flow effect would result.)

Compare the financial statements reported in Illustration 22-7 and Illustration 22-8. You can see that, under retrospective application, the change to FIFO inventory valuation affects reported inventories, cost of goods sold, net income, and retained earnings. In the following sections we discuss the accounting and reporting of Lancer's accounting change from LIFO to FIFO.

Given the information provided in Illustrations 22-6, 22-7, and 22-8, we now are ready to account for and report on the accounting change.

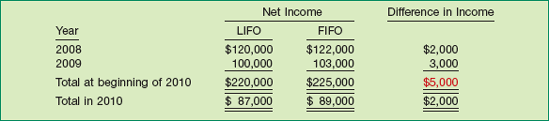

Our first step is to adjust the financial records for the change from LIFO to FIFO. To do so, we perform the analysis in Illustration 22-9.

The entry to record the change to the FIFO method at the beginning of 2010 is as follows.

The change increases the inventory account by $5,000. This amount represents the difference between the ending inventory at December 31, 2009, under LIFO ($20,000) and the ending inventory under FIFO ($25,000). The credit to Retained Earnings indicates the amount needed to change prior-year's income, assuming that Lancer had used FIFO in previous periods.

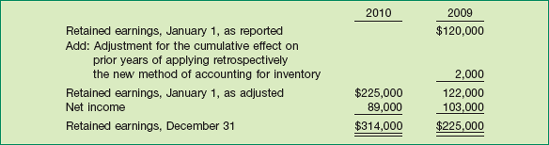

Reporting a Change in Principle. Lancer Company will prepare comparative financial statements for 2009 and 2010 using FIFO (the new inventory method). Illustration 22-10 indicates how Lancer might present this information.

As Illustration 22-10 shows, Lancer Company reports net income under the newly adopted FIFO method for both 2009 and 2010. The company retrospectively adjusted the 2009 income statement to report the information on a FIFO basis. In addition, the note to the financial statements indicates the nature of the change, why the company made the change, and the years affected. The note also provides data on important differences between the amounts reported under LIFO versus FIFO. (When identifying the significant differences, some companies show the entire financial statements and line-by-line differences between LIFO and FIFO.)

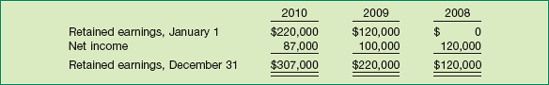

Retained Earnings Adjustment. As indicated earlier, one of the disclosure requirements is to show the cumulative effect of the change on retained earnings as of the beginning of the earliest period presented. For Lancer Company, that date is January 1, 2009. Lancer disclosed that information by means of a narrative description (see Note A in Illustration 22-10). Lancer also would disclose this information in its retained earnings statement. Illustration 22-11 shows Lancer's retained earnings statement under LIFO— that is, before giving effect to the change in accounting principle. (This information comes from Illustration 22-7 on page 1189.)

If Lancer presents comparative statements for 2009 and 2010 under FIFO, then it must change the beginning balance of retained earnings at January 1, 2009. The difference between the retained earnings balances under LIFO and FIFO is computed as follows.

The $2,000 difference is the cumulative effect. Illustration 22-12 shows a comparative retained earnings statement for 2009 and 2010, giving effect to the change in accounting principle to FIFO.

Lancer adjusted the beginning balance of retained earnings on January 1, 2009, for the excess of FIFO net income over LIFO net income in 2008. This comparative presentation indicates the type of adjustment that a company needs to make. It follows that the amount of this adjustment would be much larger if a number of prior periods were involved.

Are there other effects that a company should report when it makes a change in accounting principle? For example, what happens when a company like Lancer has a bonus plan based on net income and the prior year's net income changes when FIFO is retrospectively applied? Should Lancer also change the reported amount of bonus expense? Or what happens if we had not ignored income taxes in the Lancer example? Should Lancer adjust net income, given that taxes will be different under LIFO and FIFO in prior periods? The answers depend on whether the effects are direct or indirect.

Direct Effects. The FASB takes the position that companies should retrospectively apply the direct effects of a change in accounting principle. An example of a direct effect is an adjustment to an inventory balance as a result of a change in the inventory valuation method. For example, Lancer Company should change the inventory amounts in prior periods to indicate the change to the FIFO method of inventory valuation. Another inventory-related example would be an impairment adjustment resulting from applying the lower-of-cost-or-market test to the adjusted inventory balance. Related changes, such as deferred income tax effects of the impairment adjustment, are also considered direct effects. This entry was illustrated in the Denson example, in which the change to percentage-of-completion accounting resulted in recording a deferred tax liability.

Indirect Effects. In addition to direct effects, companies can have indirect effects related to a change in accounting principle. An indirect effect is any change to current or future cash flows of a company that result from making a change in accounting principle that is applied retrospectively. An example of an indirect effect is a change in profit-sharing or royalty payment that is based on a reported amount such as revenue or net income. Indirect effects do not change prior-period amounts.

For example, let's assume that Lancer has an employee profit-sharing plan based on net income. As Illustration 22-9 (on page 1191) showed, Lancer would report higher income in 2008 and 2009 if it used the FIFO method. In addition, let's assume that the profit-sharing plan requires that Lancer pay the incremental amount due based on the FIFO income amounts. In this situation, Lancer reports this additional expense in the current period; it would not change prior periods for this expense. If the company prepares comparative financial statements, it follows that it does not recast the prior periods for this additional expense.[401]

If the terms of the profit-sharing plan indicate that no payment is necessary in the current period due to this change, then the company need not recognize additional profit-sharing expense in the current period. Neither does it change amounts reported for prior periods.

When a company recognizes the indirect effects of a change in accounting principle, it includes in the financial statements a description of the indirect effects. In doing so, it discloses the amounts recognized in the current period and related per share information.

It is not always possible for companies to determine how they would have reported prior periods' financial information under retrospective application of an accounting principle change. Retrospective application is considered impracticable if a company cannot determine the prior-period effects using every reasonable effort to do so.

Companies should not use retrospective application if one of the following conditions exists:

The company cannot determine the effects of the retrospective application.

Retrospective application requires assumptions about management's intent in a prior period.

Retrospective application requires significant estimates for a prior period, and the company cannot objectively verify the necessary information to develop these estimates.

If any of the above conditions exists, it is deemed impracticable to apply the retrospective approach. In this case, the company prospectively applies the new accounting principle as of the earliest date it is practicable to do so. [5]

For example, assume that Williams Company changed its inventory method from FIFO to LIFO, effective January 1, 2011. Williams prepares statements on a calendar-year basis and has used the FIFO method since its inception. Williams judges it impracticable to retrospectively apply the new method. Determining prior-period effects would require subjective assumptions about the LIFO layers established in prior periods. These assumptions would ordinarily result in the computation of a number of different earnings figures.

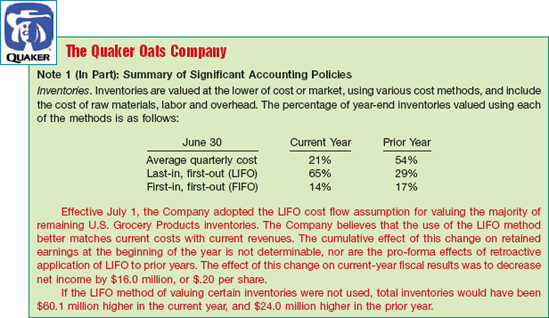

As a result, the only adjustment necessary may be to restate the beginning inventory to a cost basis from a lower-of-cost-or-market approach. Williams must disclose only the effect of the change on the results of operations in the period of change. Also, the company should explain the reasons for omitting the computations of the cumulative effect for prior years. Finally, it should disclose the justification for the change to LIFO. [6][402] Illustration 22-13, from the annual report of Quaker Oats Company, shows the type of disclosure needed.

To prepare financial statements, companies must estimate the effects of future conditions and events. For example, the following items require estimates.

Uncollectible receivables.

Inventory obsolescence.

Useful lives and salvage values of assets.

Periods benefited by deferred costs.

Liabilities for warranty costs and income taxes.

Recoverable mineral reserves.

Change in depreciation methods.

A company cannot perceive future conditions and events and their effects with certainty. Therefore, estimating requires the exercise of judgment. Accounting estimates will change as new events occur, as a company acquires more experience, or as it obtains additional information.

Companies report prospectively changes in accounting estimates. That is, companies should not adjust previously reported results for changes in estimates. Instead, they account for the effects of all changes in estimates in (1) the period of change if the change affects that period only, or (2) the period of change and future periods if the change affects both. The FASB views changes in estimates as normal recurring corrections and adjustments, the natural result of the accounting process. It prohibits retrospective treatment.

The circumstances related to a change in estimate differ from those for a change in accounting principle. If companies reported changes in estimates retrospectively, continual adjustments of prior years' income would occur. It seems proper to accept the view that, because new conditions or circumstances exist, the revision fits the new situation (not the old one). Companies should therefore handle such a revision in the current and future periods.

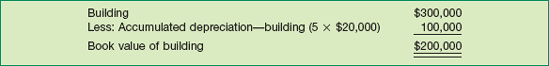

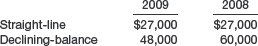

To illustrate, Underwriters Labs Inc. purchased for $300,000 a building that it originally estimated to have a useful life of 15 years and no salvage value. It recorded depreciation for 5 years on a straight-line basis. On January 1, 2010, Underwriters Labs revises the estimate of the useful life. It now considers the asset to have a total life of 25 years. (Assume that the useful life for financial reporting and tax purposes and depreciation method are the same.) Illustration 22-14 shows the accounts at the beginning of the sixth year.

Underwriters Labs records depreciation for the year 2010 as follows:

The company computes the $10,000 depreciation charge as shown in Illustration 22-15.

Companies sometime find it difficult to differentiate between a change in estimate and a change in accounting principle. Is it a change in principle or a change in estimate when a company changes from deferring and amortizing marketing costs to expensing them as incurred because future benefits of these costs have become doubtful? If it is impossible to determine whether a change in principle or a change in estimate has occurred, the rule is this: Consider the change as a change in estimate. This is often referred to as a change in estimate effected by a change in accounting principle.

Another example of a change in estimate effected by a change in principle is a change in depreciation (as well as amortization or depletion) methods. Because companies change depreciation methods based on changes in estimates about future benefits from long-lived assets, it is not possible to separate the effect of the accounting principle change from that of the estimates. As a result, companies account for a change in depreciation methods as a change in estimate effected by a change in accounting principle. [7]

A similar problem occurs in differentiating between a change in estimate and a correction of an error, although here the answer is more clear-cut. How does a company determine whether it overlooked the information in earlier periods (an error), or whether it obtained new information (a change in estimate)? Proper classification is important because the accounting treatment differs for corrections of errors versus changes in estimates. The general rule is this: Companies should consider careful estimates that later prove to be incorrect as changes in estimate. Only when a company obviously computed the estimate incorrectly because of lack of expertise or in bad faith should it consider the adjustment an error. There is no clear demarcation line here. Companies must use good judgment in light of all the circumstances.[403]

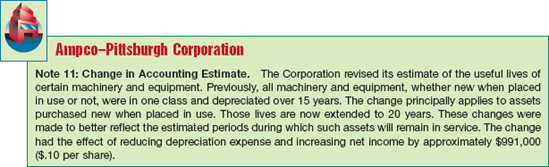

Illustration 22-16 shows disclosure of a change in estimated useful lives, which appeared in the annual report of Ampco–Pittsburgh Corporation.

For the most part, companies need not disclose changes in accounting estimate made as part of normal operations, such as bad debt allowances or inventory obsolescence, unless such changes are material. However, for a change in estimate that affects several periods (such as a change in the service lives of depreciable assets), companies should disclose the effect on income from continuing operations and related per-share amounts of the current period. When a company has a change in estimate effected by a change in accounting principle, it must indicate why the new method is preferable. In addition, companies are subject to all other disclosure guidelines established for changes in accounting principle.

Occasionally companies make changes that result in different reporting entities. In such cases, companies report the change by changing the financial statements of all prior periods presented. The revised statements show the financial information for the new reporting entity for all periods.

Examples of a change in reporting entity are:

Presenting consolidated statements in place of statements of individual companies.

Changing specific subsidiaries that constitute the group of companies for which the entity presents consolidated financial statements.

Changing the companies included in combined financial statements.

Changing the cost, equity, or consolidation method of accounting for subsidiaries and investments.[404] In this case, a change in the reporting entity does not result from creation, cessation, purchase, or disposition of a subsidiary or other business unit.

In the year in which a company changes a reporting entity, it should disclose in the financial statements the nature of the change and the reason for it. It also should report, for all periods presented, the effect of the change on income before extraordinary items, net income, and earnings per share. These disclosures need not be repeated in subsequent periods' financial statements.

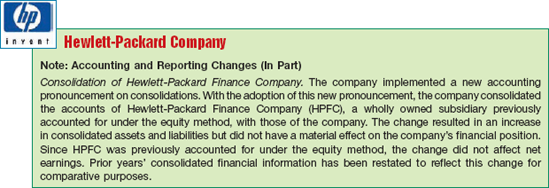

Illustration 22-17 shows a note disclosing a change in reporting entity, from the annual report of Hewlett-Packard Company.

No business, large or small, is immune from errors. As the opening story discussed, the number of accounting errors that lead to restatement are beginning to decline. However, without accounting and disclosure guidelines for the reporting of errors, investors can be left in the dark about the effects of errors.

Certain errors, such as misclassifications of balances within a financial statement, are not as significant to investors as other errors. Significant errors would be those resulting in overstating assets or income, for example. However, investors should know the potential impact of all errors. Even "harmless" misclassifications can affect important ratios. Also, some errors could signal important weaknesses in internal controls that could lead to more significant errors.

In general, accounting errors include the following types:

A change from an accounting principle that is not generally accepted to an accounting principle that is acceptable. The rationale is that the company incorrectly presented prior periods because of the application of an improper accounting principle. For example, a company may change from the cash (income tax) basis of accounting to the accrual basis.

Mathematical mistakes, such as incorrectly totaling the inventory count sheets when computing the inventory value.

Changes in estimates that occur because a company did not prepare the estimates in good faith. For example, a company may have adopted a clearly unrealistic depreciation rate.

An oversight, such as the failure to accrue or defer certain expenses and revenues at the end of the period.

A misuse of facts, such as the failure to use salvage value in computing the depreciation base for the straight-line approach.

The incorrect classification of a cost as an expense instead of an asset, and vice versa.

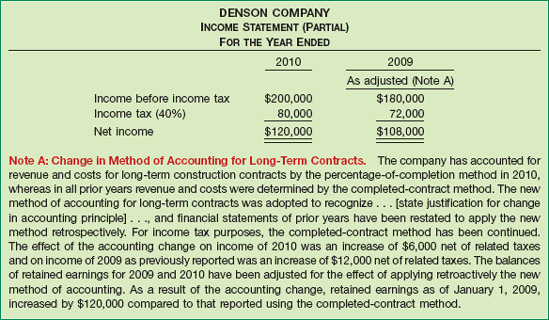

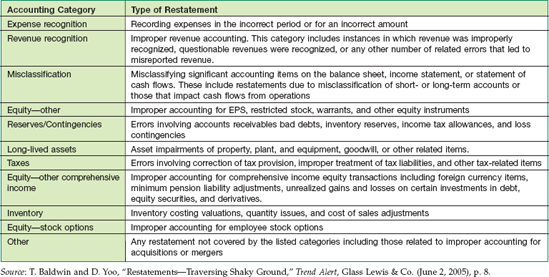

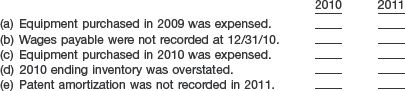

Accounting errors occur for a variety of reasons. Illustration 22-18 indicates 11 major categories of accounting errors that drive restatements.

As soon as a company discovers an error, it must correct the error. Companies record corrections of errors from prior periods as an adjustment to the beginning balance of retained earnings in the current period. Such corrections are called prior period adjustments.[405][8]

If it presents comparative statements, a company should restate the prior statements affected, to correct for the error.[406] The company need not repeat the disclosures in the financial statements of subsequent periods.

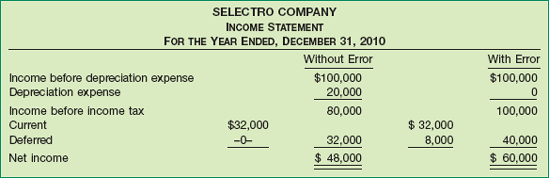

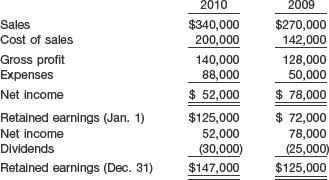

To illustrate, in 2011 the bookkeeper for Selectro Company discovered an error: In 2010 the company failed to record $20,000 of depreciation expense on a newly constructed building. This building is the only depreciable asset Selectro owns. The company correctly included the depreciation expense in its tax return and correctly reported its income taxes payable. Illustration 22-19 presents Selectro's income statement for 2010 (starting with income before depreciation expense) with and without the error.

Illustration 22-20 shows the entries that Selectro should have made and did make for recording depreciation expense and income taxes.

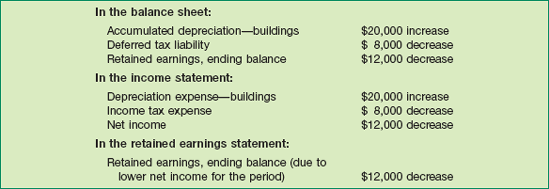

As Illustration 22-20 indicates, the $20,000 omission error in 2010 results in the following effects.

Income Statement Effects

Depreciation expense (2010) is understated $20,000.

Income tax expense (2010) is overstated $8,000 ($20,000 × 40%).

Net income (2010) is overstated $12,000 ($20,000 − $8,000).

Balance Sheet Effects

Accumulated depreciation—buildings is understated $20,000.

Deferred tax liability is overstated $8,000 ($20,000 × 40%).

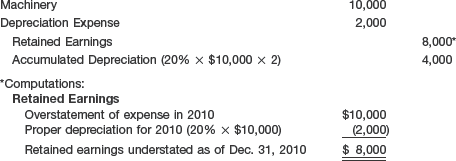

To make the proper correcting entry in 2011, Selectro should recognize that net income in 2010 is overstated by $12,000, the Deferred Tax Liability is overstated by $8,000, and Accumulated Depreciation—Buildings is understated by $20,000. The entry to correct this error in 2011 is as follows:

The debit to Retained Earnings results because net income for 2010 is overstated. The debit to the Deferred Tax Liability is made to remove this account, which was caused by the error. The credit to Accumulated Depreciation—Buildings reduces the book value of the building to its proper amount. Selectro will make the same journal entry to record the correction of the error in 2011 whether it prepares single-period (noncomparative) or comparative financial statements.

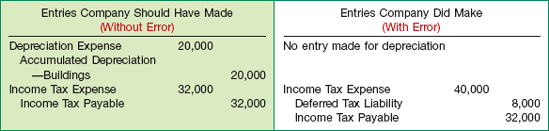

To demonstrate how to show this information in a single-period statement, assume that Selectro Company has a beginning retained earnings balance at January 1, 2011, of $350,000. The company reports net income of $400,000 in 2011. Illustration 22-21 shows Selectro's retained earnings statement for 2011.

The balance sheet in 2011 would not have any deferred tax liability related to the building, and Accumulated Depreciation—Buildings is now restated at a higher amount. The income statement would not be affected.

If preparing comparative financial statements, a company should make adjustments to correct the amounts for all affected accounts reported in the statements for all periods reported. The company should restate the data to the correct basis for each year presented. It should show any catch-up adjustment as a prior period adjustment to retained earnings for the earliest period it reported. These requirements are essentially the same as those for reporting a change in accounting principle.

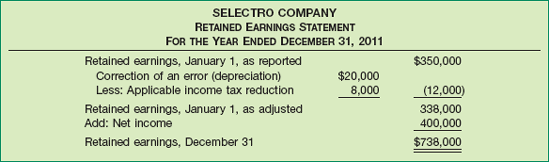

For example, in the case of Selectro, the error of omitting the depreciation of $20,000 in 2010, discovered in 2011, results in the restatement of the 2010 financial statements. Illustration 22-22 shows the accounts that Selectro restates in the 2010 financial statements.

Selectro prepares the 2011 financial statements in comparative form with those of 2010 as if the error had not occurred. In addition, Selectro must disclose that it has restated its previously issued financial statements, and it describes the nature of the error. Selectro also must disclose the following:

The effect of the correction on each financial statement line item and any per-share amounts affected for each prior period presented.

The cumulative effect of the change on retained earnings or other appropriate components of equity or net assets in the statement of financial position, as of the beginning of the earliest period presented. [10]

Having guidelines for reporting accounting changes and corrections has helped resolve several significant and long-standing accounting problems. Yet, because of diversity in situations and characteristics of the items encountered in practice, use of professional judgment is of paramount importance. In applying these guidelines, the primary objective is to serve the users of the financial statements. Achieving this objective requires accuracy, full disclosure, and an absence of misleading inferences.

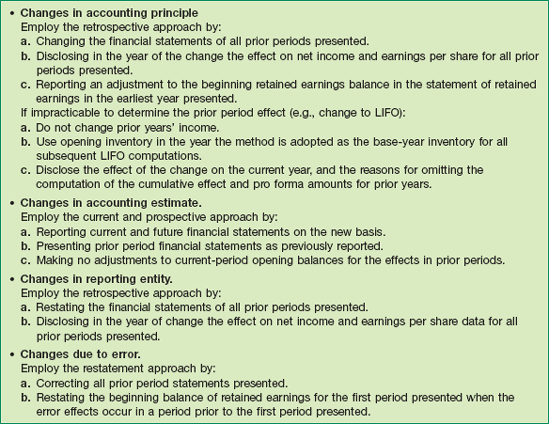

Illustration 22-23 summarizes the main distinctions and treatments presented in the discussion in this chapter.

Changes in accounting principle are appropriate only when a company demonstrates that the newly adopted generally accepted accounting principle is preferable to the existing one. Companies and accountants determine preferability on the basis of whether the new principle constitutes an improvement in financial reporting, not on the basis of the income tax effect alone.[407]

But it is not always easy to determine an improvement in financial reporting. How does one measure preferability or improvement? Such measurement varies from company to company. Quaker Oats Company, for example, argued that a change in accounting principle to LIFO inventory valuation "better matches current costs with current revenues" (see Illustration 22-13, page 1194). Conversely, another company might change from LIFO to FIFO because it wishes to report a more realistic ending inventory. How do you determine which is the better of these two arguments? Determining the preferable method requires some "standard" or "objective." Because no universal standard or objective is generally accepted, the problem of determining preferability continues to be difficult.

Initially the SEC took the position that the auditor should indicate whether a change in accounting principle was preferable. The SEC has since modified this approach, noting that greater reliance may be placed on management's judgment in assessing preferability. Even though the preferability criterion is difficult to apply, the general guidelines have acted as a deterrent to capricious changes in accounting principles.[408] If a FASB rule creates a new principle, expresses preference for, or rejects a specific accounting principle, a change is considered clearly acceptable.

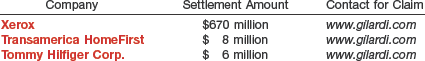

When companies report restatements, investors usually lose money. What should investors do if a company misleads them by misstating its financial results? Join other investors in a class-action suit against the company and in some cases, the auditor.

Class-action activity has picked up in recent years, and settlements can be large. To find out about class actions, investors can go online to see if they are eligible to join any class actions. Below are some recent examples.

The amounts reported are before attorney's fees, which can range from 15 to 30 percent of the total. Also, investors may owe taxes if the settlement results in a capital gain on the investment. Thus, investors can get back some of the money they lost due to restatements, but they should be prepared to pay an attorney and the government first.

Source: Adapted from C. Coolidge, "Lost and Found," Forbes (October 1, 2001), pp. 124–125; data from www.gilardi.com as of 8/14/08.

Difficult as it is to determine which accounting standards have the strongest conceptual support, other complications make the process even more complex. These complications stem from the fact that managers have self-interest in how the financial statements make the company look. They naturally wish to show their financial performance in the best light. A favorable profit picture can influence investors, and a strong liquidity position can influence creditors. Too favorable a profit picture, however, can provide union negotiators and government regulators with ammunition during bargaining talks. Hence, managers might have varying motives for reporting income numbers.

Research has provided additional insight into why companies may prefer certain accounting methods.[409] Some of these reasons are as follows:

Political Costs. As companies become larger and more politically visible, politicians and regulators devote more attention to them. The larger the firm, the more likely it is to become subject to regulation such as antitrust, and the more likely it is to be required to pay higher taxes. Therefore, companies that are politically visible may seek to report low income numbers, to avoid the scrutiny of regulators. In addition, other constituents, such as labor unions, may be less willing to ask for wage increases if reported income is low. Researchers have found that the larger the company, the more likely it is to adopt income-decreasing approaches in selecting accounting methods.

Capital Structure. A number of studies have indicated that the capital structure of the company can affect the selection of accounting methods. For example, a company with a high debt-to-equity ratio is more likely to be constrained by debt covenants. The debt covenant may indicate that the company cannot pay dividends if retained earnings fall below a certain level. As a result, such a company is more likely to select accounting methods that will increase net income.

Bonus Payments. Studies have found that if compensation plans tie managers' bonus payments to income, management will select accounting methods that maximize their bonus payments.

Smooth Earnings. Substantial earnings increases attract the attention of politicians, regulators, and competitors. In addition, large increases in income are difficult to achieve in following years. Further, executive compensation plans would use these higher numbers as a baseline and make it difficult for managers to earn bonuses in subsequent years. Conversely, investors and competitors might view large decreases in earnings as a signal that the company is in financial trouble. Also, substantial decreases in income raise concerns on the part of stockholders, lenders, and other interested parties about the competency of management. For all these reasons, companies have an incentive to "manage" or "smooth" earnings. In general, management tends to believe that a steady 10 percent growth a year is much better than a 30 percent growth one year and a 10 percent decline the next.[410] In other words, managers usually prefer a gradually increasing income report and sometimes change accounting methods to ensure such a result.

Management pays careful attention to the accounting it follows and often changes accounting methods, not for conceptual reasons, but for economic reasons. As indicated throughout this textbook, such arguments have come to be known as economic consequences arguments. These arguments focus on the supposed impact of the accounting method on the behavior of investors, creditors, competitors, governments, or managers of the reporting companies themselves.[411]

To counter these pressures, standard-setters such as the FASB have declared, as part of their conceptual framework, that they will assess the merits of proposed standards from a position of neutrality. That is, they evaluate the soundness of standards on the basis of conceptual soundness, not on the grounds of possible impact on behavior. It is not the FASB's place to choose standards according to the kinds of behavior it wishes to promote and the kinds it wishes to discourage. At the same time, it must be admitted that some standards often will have the effect of influencing behavior. Yet their justification should be conceptual, and not viewed in terms of their economic impact.

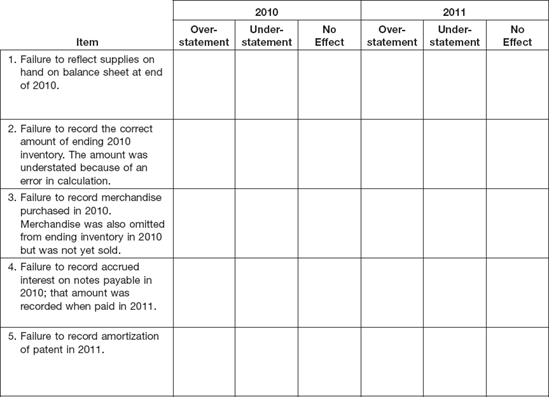

In this section, we show some additional types of accounting errors. Companies generally do not correct for errors that do not have a significant effect on the presentation of the financial statements. For example, should a company with a total annual payroll of $1,750,000 and net income of $940,000 correct its financial statements if it finds it failed to record accrued wages of $5,000? No—it would not consider this error significant.

Obviously, defining materiality is difficult, and managers and auditors must use experience and judgment to determine whether adjustment is necessary for a given error. We assume all errors discussed in this section to be material and to require adjustment. (Also, we ignore all tax effects in this section.)

Companies must answer three questions in error analysis:

What type of error is involved?

What entries are needed to correct for the error?

After discovery of the error, how are financial statements to be restated?

As indicated earlier, companies treat errors as prior-period adjustments and report them in the current year as adjustments to the beginning balance of Retained Earnings. If a company presents comparative statements, it restates the prior affected statements to correct for the error.

Balance sheet errors affect only the presentation of an asset, liability, or stockholders' equity account. Examples are the classification of a short-term receivable as part of the investment section, the classification of a note payable as an account payable, and the classification of plant assets as inventory.

When the error is discovered, the company reclassifies the item to its proper position. If the company prepares comparative statements that include the error year, it should correctly restate the balance sheet for the error year.

Income statement errors involve the improper classification of revenues or expenses. Examples include recording interest revenue as part of sales, purchases as bad debt expense, and depreciation expense as interest expense. An income statement classification error has no effect on the balance sheet and no effect on net income.

A company must make a reclassification entry when it discovers the error, if it makes the discovery in the same year in which the error occurs. If the error occurred in prior periods, the company does not need to make a reclassification entry at the date of discovery because the accounts for the current year are correctly stated. (Remember that the company has closed the income statement accounts from the prior period to retained earnings.) If the company prepares comparative statements that include the error year, it restates the income statement for the error year.

The third type of error involves both the balance sheet and income statement. For example, assume that the bookkeeper overlooked accrued wages payable at the end of the accounting period. The effect of this error is to understate expenses, understate liabilities, and overstate net income for that period of time. This type of error affects both the balance sheet and the income statement. We classify this type of error in one of two ways—counterbalancing or noncounterbalancing.

Counterbalancing errors are those that will be offset or corrected over two periods. For example, the failure to record accrued wages is a counterbalancing error because over a two-year period the error will no longer be present. In other words, the failure to record accrued wages in the previous period means: (1) net income for the first period is overstated; (2) accrued wages payable (a liability) is understated, and (3) wages expense is understated. In the next period, net income is understated; accrued wages payable (a liability) is correctly stated; and wages expense is overstated. For the two years combined: (1) net income is correct; (2) wages expense is correct; and (3) accrued wages payable at the end of the second year is correct. Most errors in accounting that affect both the balance sheet and income statement are counterbalancing errors.

Noncounterbalancing errors are those that are not offset in the next accounting period. An example would be the failure to capitalize equipment that has a useful life of five years. If we expense this asset immediately, expenses will be overstated in the first period but understated in the next four periods. At the end of the second period, the effect of the error is not fully offset. Net income is correct in the aggregate only at the end of five years, because the asset is fully depreciated at this point. Thus, noncounterbalancing errors are those that take longer than two periods to correct themselves.

Only in rare instances is an error never reversed. An example would be if a company initially expenses land. Because land is not depreciable, theoretically the error is never offset, unless the land is sold.

We illustrate the usual types of counterbalancing errors on the following pages. In studying these illustrations, keep in mind a couple of points, discussed below.

First, determine whether the company has closed the books for the period in which the error is found:

If the company has closed the books in the current year:

If the error is already counterbalanced, no entry is necessary.

If the error is not yet counterbalanced, make an entry to adjust the present balance of retained earnings.

If the company has not closed the books in the current year:

If the error is already counterbalanced, make an entry to correct the error in the current period and to adjust the beginning balance of Retained Earnings.

If the error is not yet counterbalanced, make an entry to adjust the beginning balance of Retained Earnings.

Second, if the company presents comparative statements, it must restate the amounts for comparative purposes. Restatement is necessary even if a correcting journal entry is not required.

To illustrate, assume that Sanford's Cement Co. failed to accrue revenue in 2008 when earned, but recorded the revenue in 2009 when received. The company discovered the error in 2011. It does not need to make an entry to correct for this error because the effects have been counterbalanced by the time Sanford discovered the error in 2011. However, if Sanford presents comparative financial statements for 2008 through 2011, it must restate the accounts and related amounts for the years 2008 and 2009 for financial reporting purposes.

The sections that follow demonstrate the accounting for the usual types of counterbalancing errors.

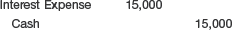

On December 31, 2010, Hurley Enterprises did not accrue wages in the amount of $1,500. The entry in 2011 to correct this error, assuming Hurley has not closed the books for 2011, is:

The rationale for this entry is as follows: (1) When Hurley pays the 2010 accrued wages in 2011, it makes an additional debit of $1,500 to 2011 Wages Expense. (2) Wages Expense—2011 is overstated by $1,500. (3) Because the company did not record 2010 accrued wages as Wages Expense in 2010, the net income for 2010 was overstated by $1,500. (4) Because 2010 net income is overstated by $1,500, the Retained Earnings account is overstated by $1,500 (because net income is closed to Retained Earnings).

If Hurley has closed the books for 2011, it makes no entry, because the error is counterbalanced.

In January 2010 Hurley Enterprises purchased a two-year insurance policy costing $1,000. It debited Insurance Expense, and credited Cash. The company made no adjusting entries at the end of 2010.

The entry on December 31, 2011, to correct this error, assuming Hurley has not closed the books for 2011, is:

If Hurley has closed the books for 2011, it makes no entry, because the error is counterbalanced.

On December 31, 2010, Hurley Enterprises received $50,000 as a prepayment for renting certain office space for the following year. At the time of receipt of the rent payment, the company recorded a debit to Cash and a credit to Rent Revenue. It made no adjusting entry as of December 31, 2010. The entry on December 31, 2011, to correct for this error, assuming that Hurley has not closed the books for 2011, is:

If Hurley has closed the books for 2011, it makes no entry, because the error is counterbalanced.

On December 31, 2010, Hurley Enterprises accrued as interest revenue $8,000 that applied to 2011. On that date, the company recorded a debit to Interest Receivable and a credit to Interest Revenue. The entry on December 31, 2011, to correct for this error, assuming that Hurley has not closed the books for 2011, is:

If Hurley has closed the books for 2011, it makes no entry, because the error is counterbalanced.

Hurley's accountant recorded a purchase of merchandise for $9,000 in 2010 that applied to 2011. The physical inventory for 2010 was correctly stated. The company uses the periodic inventory method. The entry on December 31, 2011, to correct for this error, assuming that Harley has not closed the books for 2011, is:

If Hurley has closed the books for 2011, it makes no entry, because the error is counterbalanced.

The entries for noncounterbalancing errors are more complex. Companies must make correcting entries, even if they have closed the books.

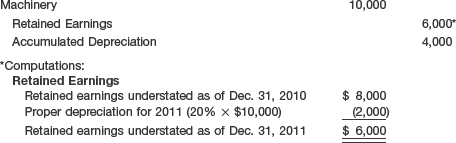

Assume that on January 1, 2010, Hurley Enterprises purchased a machine for $10,000 that had an estimated useful life of five years. The accountant incorrectly expensed this machine in 2010, but discovered the error in 2011. If we assume that Hurley uses straight-line depreciation on this asset, the entry on December 31, 2011, to correct for this error, given that Hurley has not closed the books, is:

If Hurley has closed the books for 2011, the entry is:

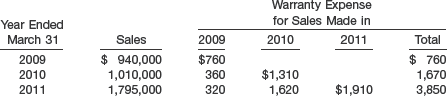

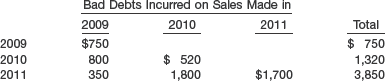

Companies sometimes use a specific charge-off method in accounting for bad debt expense when a percentage of sales is more appropriate. They then make adjustments to change from the specific write-off to some type of allowance method. For example, assume that Hurley Enterprises has recognized bad debt expense when it has the following uncollectible debts.

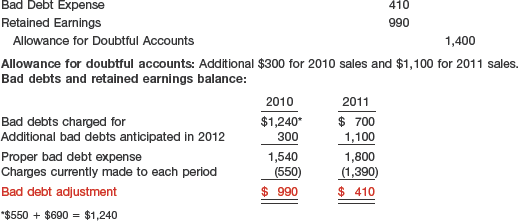

Hurley estimates that it will charge off an additional $1,400 in 2012, of which $300 is applicable to 2010 sales and $1,100 to 2011 sales. The entry on December 31, 2011, assuming that Hurley has not closed the books for 2011, is:

If Hurley has closed the books for 2011, the entry is:

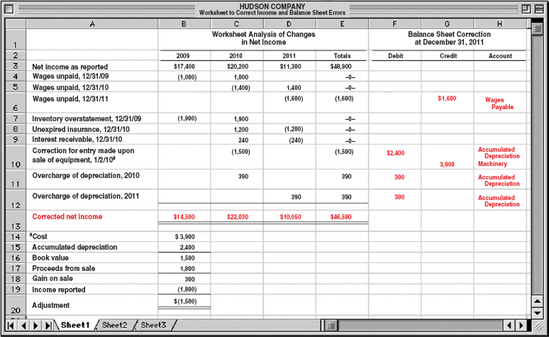

In some circumstances a combination of errors occurs. The company therefore prepares a worksheet to facilitate the analysis. The following problem demonstrates use of the worksheet. The mechanics of its preparation should be obvious from the solution format. The income statements of Hudson Company for the years ended December 31, 2009, 2010, and 2011 indicate the following net incomes.

2009 | $17,400 |

2010 | 20,200 |

2011 | 11,300 |

An examination of the accounting records for these years indicates that Hudson Company made several errors in arriving at the net income amounts reported:

The company consistently omitted from the records wages earned by workers but not paid at December 31. The amounts omitted were:

December 31, 2009

$1,000

December 31, 2010

$1,400

December 31, 2011

$1,600

When paid in the year following that in which they were earned, Hudson recorded these amounts as expenses.

The company overstated merchandise inventory on December 31, 2009, by $1,900 as the result of errors made in the footings and extensions on the inventory sheets.

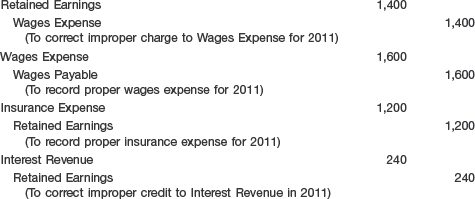

On December 31, 2010, Hudson expensed unexpired insurance of $1,200, applicable to 2011.

The company did not record on December 31, 2010, interest receivable in the amount of $240.

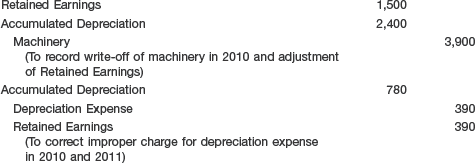

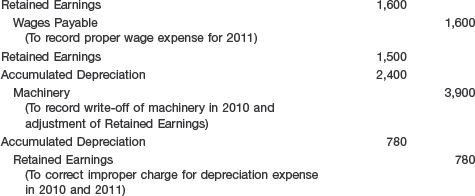

On January 2, 2010, Hudson sold for $1,800 a piece of equipment costing $3,900. At the date of sale the equipment had accumulated depreciation of $2,400. The company recorded the cash received as Miscellaneous Income in 2010. In addition, the company continued to record depreciation for this equipment in both 2010 and 2011 at the rate of 10 percent of cost.

The first step in preparing the worksheet is to prepare a schedule showing the corrected net income amounts for the years ended December 31, 2009, 2010, and 2011. Each correction of the amount originally reported is clearly labeled. The next step is to indicate the balance sheet accounts affected as of December 31, 2011. Illustration 22-24 shows the completed worksheet for Hudson Company.

Assuming that Hudson Company has not closed the books, correcting entries on December 31, 2011, are:

If Hudson Company has closed the books for 2011, the correcting entries are:

Up to now, our discussion of error analysis has focused on identifying the type of error involved and accounting for its correction in the records. We have noted that companies must present the correction of the error on comparative financial statements.

The following example illustrates how a company would restate a typical year's financial statements, given many different errors.

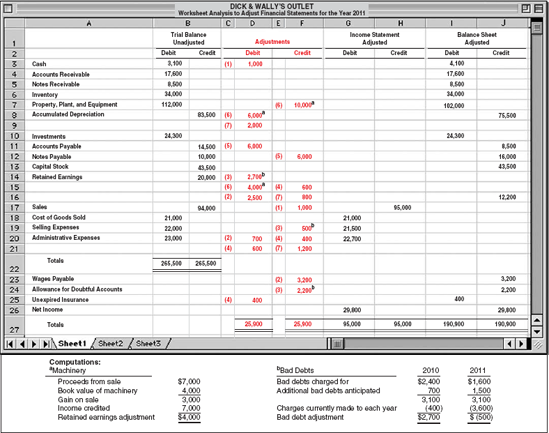

Dick & Wally's Outlet is a small retail outlet in the town of Holiday. Lacking expertise in accounting, the company does not keep adequate records, and numerous errors occurred in recording accounting information.

The bookkeeper inadvertently failed to record a cash receipt of $1,000 on the sale of merchandise in 2011.

Accrued wages expense at the end of 2010 was $2,500; at the end of 2011, $3,200. The company does not accrue for wages; all wages are charged to Administrative Expenses.

The company had not set up an allowance for estimated uncollectible receivables. Dick and Wally decided to set up such an allowance for the estimated probable losses, as of December 31, 2011, for 2010 accounts of $700, and for 2011 accounts of $1,500. They also decided to correct the charge against each year so that it shows the losses (actual and estimated) relating to that year's sales. The company has written off accounts to bad debt expense (selling expense) as follows.

Unexpired insurance not recorded at the end of 2010 was $600, and at the end of 2011, $400. All insurance is charged to Administrative Expenses.

An account payable of $6,000 should have been a note payable.

During 2010, the company sold for $7,000 an asset that cost $10,000 and had a book value of $4,000. At the time of sale Cash was debited, and Miscellaneous Income was credited for $7,000.

As a result of the last transaction, the company overstated depreciation expense (an administrative expense) in 2010 by $800 and in 2011 by $1,200.

Illustration 22-25 presents a worksheet that begins with the unadjusted trial balance of Dick & Wally's Outlet. You can determine the correcting entries and their effect on the financial statements by examining the worksheet.

The iGAAP standard addressing accounting and reporting for changes in accounting principles, changes in estimates, and errors is IAS 8 ("Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors"). Various presentation issues related to restatements are addressed in IAS 1 ("Presentation of Financial Statements"). As indicated in the chapter, the FASB has issued guidance on changes in accounting principles, changes in estimates, and corrections of errors, which essentially converges U.S. GAAP to IAS 8.

One area in which iGAAP and U.S. GAAP differ is the reporting of error corrections in previously issued financial statements. While both GAAPs require restatement, U.S. GAAP is an absolute standard—that is, there is no exception to this rule.

The accounting for changes in estimates is similar between U.S. GAAP and iGAAP.

Under U.S. GAAP and iGAAP, if determining the effect of a change in accounting principle is considered impracticable, then a company should report the effect of the change in the period in which it believes it practicable to do so, which may be the current period.

Under iGAAP, the impracticality exception applies both to changes in accounting principles and to the correction of errors. Under U.S. GAAP, this exception applies only to changes in accounting principle.

IAS 8 does not specifically address the accounting and reporting for indirect effects of changes in accounting principles. As indicated in the chapter, U.S. GAAP has detailed guidance on the accounting and reporting of indirect effects.

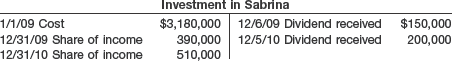

An interesting sidelight to our discussion of accounting changes involves how companies that follow iGAAP report financial information related to the equity method of accounting. Under the equity method of accounting, the investor increases its investment for the pro-rata share of the net income of the investee (often referred to as an associated company under iGAAP). On the other hand, the investor reduces its investment for any dividends received from the investee. Both iGAAP and U.S. GAAP follow this accounting approach.

However, there is a subtle difference between iGAAP and U.S. GAAP related to how the investor evaluates the accounting policies of the investee. To illustrate, assume that Kirkland Company (the investor company) uses the FIFO inventory method, and Margo Company (the investee company) uses average cost for its inventory valuation. If Kirkland follows iGAAP, Kirkland must conform the accounting policies of Margo to its own accounting policies. Therefore Kirkland adjusts the net income of Margo so its net income is reported on the FIFO basis.

This procedure is not used under U.S. GAAP. Under U.S. GAAP Kirkland ignores the fact that Margo uses a different method of inventory valuation. Kirkland records its pro-rata share of the net income of Margo without adjusting for the fact that Margo uses a different inventory valuation method. As a result, there is a lack of comparability in the inventory methods used to report net income for Kirkland Company under U.S. GAAP.

For the most part, iGAAP and U.S. GAAP are similar in the area of accounting changes and reporting the effects of errors. Thus, there is no active project in this area. A related development involves the presentation of comparative data. Under iGAAP, when a company prepares financial statements on a new basis, 2 years of comparative data are reported. U.S. GAAP requires comparative information for a 3-year period. Use of the shorter comparative data period must be addressed before U.S. companies can adopt iGAAP.

As an aid to understanding accounting changes, we provide the following glossary.

As noted in the chapter, companies generally should report an accounting change that results in financial statements for a different entity by changing the financial statements of all prior periods presented.

An example of a change in reporting entity is when a company's level of ownership or influence changes, such as when it changes from or to the equity method. When changing to the equity method, companies use retrospective application. Companies treat a change from the equity method prospectively. We present examples of these changes in entity in the following two sections.

If the investor level of influence or ownership falls below that necessary for continued use of the equity method, a company must change from the equity method to the fair value method. The earnings or losses that the investor previously recognized under the equity method should remain as part of the carrying amount of the investment, with no retrospective application to the new method.

When a company changes from the equity method to the fair value method, the cost basis for accounting purposes is the carrying amount of the investment at the date of the change. The investor applies the new method in its entirety once the equity method is no longer appropriate. At the next reporting date, the investor should record the unrealized holding gain or loss to recognize the difference between the carrying amount and fair value.[412]

In subsequent periods, dividends received by the investor company may exceed its share of the investee's earnings for such periods (all periods following the change in method). To the extent that they do so, the investor company should account for such dividends as a reduction of the investment carrying amount, rather than as revenue. The reason: dividends in excess of earnings are viewed as a liquidating dividend with this excess then accounted for as a reduction of the equity investment.

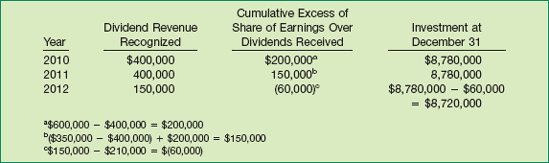

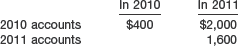

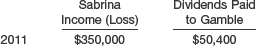

To illustrate, assume that on January 1, 2009, Investor Company purchased 250,000 shares of Investee Company's 1,000,000 shares of outstanding stock for $8,500,000. Investor correctly accounted for this investment using the equity method. After accounting for dividends received and investee net income, in 2009, Investor reported its investment in Investee Company at $8,780,000 at December 31, 2009. On January 2, 2010, Investee Company sold 1,500,000 additional shares of its own common stock to the public, thereby reducing Investor Company's ownership from 25 percent to 10 percent. Illustration 22A-1 shows the net income (or loss) and dividends of Investee Company for the years 2010 through 2012.

Assuming a change from the equity method to the fair value method as of January 2, 2010, Investor Company's reported investment in Investee Company and its reported income would be as shown in Illustration 22A-2.

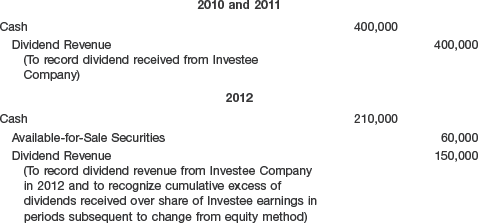

Investor Company would record the dividends and earnings data for the three years subsequent to the change in methods as shown by the following entries.

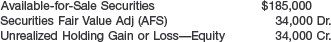

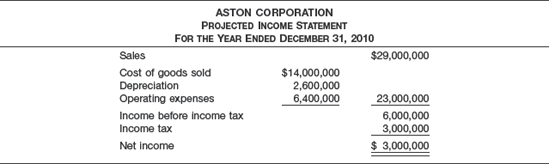

When converting to the equity method, companies use retrospective application. Such a change involves adjusting the carrying amount of the investment, results of current and prior operations, and retained earnings of the investor as if the equity method has been in effect during all of the previous periods in which this investment was held. [12] When changing from the fair value method to the equity method, companies also must eliminate any balances in the Unrealized Holding Gain or Loss—Equity account and the Securities Fair Value Adjustment account. In addition, they eliminate the available-for-sale classification for this investment, and they record the investment under the equity method.

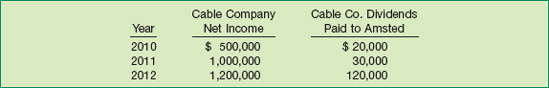

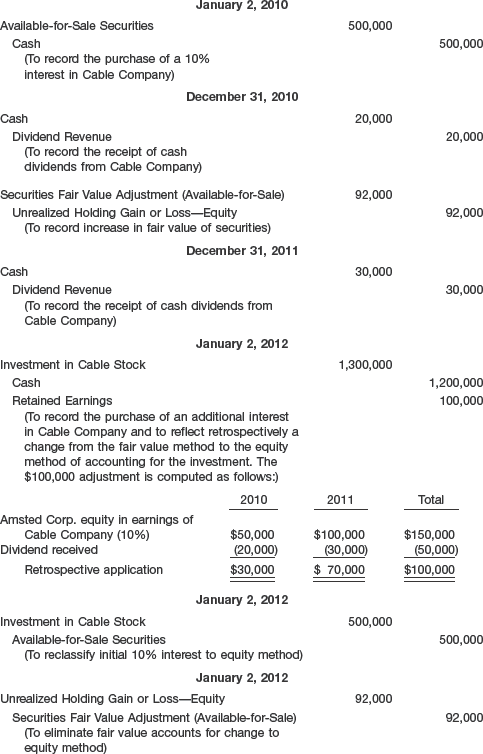

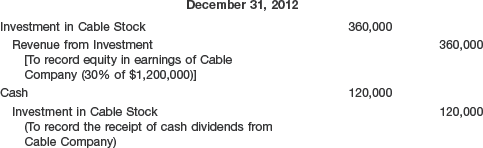

For example, on January 2, 2010, Amsted Corp. purchased, for $500,000 cash, 10 percent of the outstanding shares of Cable Company common stock. On that date, the net identifiable assets of Cable Company had a fair value of $3,000,000. The excess of cost over the underlying equity in the net identifiable assets of Cable Company is goodwill. On January 2, 2012, Amsted Corp. purchased an additional 20 percent of Cable Company's stock for $1,200,000 cash when the fair value of Cable's net identifiable assets was $4,000,000. The excess of cost over fair value related to this additional investment is goodwill. Now having a 30 percent interest, Amsted Corp. must use the equity method.

From January 2, 2010, to January 2, 2012, Amsted Corp. used the fair value method and categorized these securities as available-for-sale. At January 2, 2012, Amsted has a credit balance of $92,000 in its Unrealized Holding Gain or Loss—Equity account and a debit balance in its Securities Fair Value Adjustment account of the same amount. This change in fair value occurred in 2010 (Income tax effects are ignored.) Illustration 22A-3 (page 1217) shows the net income reported by Cable Company and the Cable Company dividends received by Amsted during the period 2010 through 2012.

Amsted makes the following journal entries from January 2, 2010, through December 31, 2012, relative to Amsted Corp.'s investment in Cable Company, reflecting the data above and a change from the fair value method to the equity method.[413]

Companies change to the equity method by placing the accounts related to and affected by the investment on the same basis as if the equity method had always been the basis of accounting for that investment. Thus, they report the effects of this accounting change using the retrospective approach.[414]

SUMMARY OF LEARNING OBJECTIVES FOR APPENDIX 22A

FASB Codification References

FASB ASC 250-10-05-1. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting Changes and Error Corrections," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 154 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 2005).]

FASB ASC 250-10-05-2. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting Changes and Error Corrections," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 154 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 2005).]

FASB ASC 250-10-50-1. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting Changes and Error Corrections," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 154 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 2005), par. 17.]

FASB ASC 250-10-50-1. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting Changes and Error Corrections," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 154 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 2005), par. B19.]

FASB ASC 250-10-45-6. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting Changes and Error Corrections," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 154 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 2005), pars. 8–11.]

FASB ASC 250-10-50-1. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting Changes and Error Corrections," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 154 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 2005), par. 17.]

FASB ASC 250-10-45-18. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting Changes and Error Corrections," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 154 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 2005), par. 20.]

FASB ASC 250-10-45-24. [Predecessor literature: "Prior Period Adjustments," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 16 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1977), p. 5.]

FASB ASC 250-10-50-4. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting Changes and Error Corrections," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 154 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 2005), par. 2.]

FASB ASC 250-10-50-7. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting Changes and Error Corrections," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 154 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 2005), par. 26.]

FASB ASC 250-10-50-1. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting Changes and Error Corrections," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 154 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 2005), par. 2.]

FASB ASC 323-10-35-33. [Predecessor literature: "The Equity Method of Accounting for Investments in Common Stock," Opinions of the Accounting Principles Board No. 18 (New York: AICPA, 1971), par. 17.]

Note: All asterisked Questions, Exercises, and Problems relate to material in the appendix to the chapter.

In recent years, the Wall Street Journal has indicated that many companies have changed their accounting principles. What are the major reasons why companies change accounting methods?

State how each of the following items is reflected in the financial statements.

Change from FIFO to LIFO method for inventory valuation purposes.

Charge for failure to record depreciation in a previous period.

Litigation won in current year, related to prior period.

Change in the realizability of certain receivables.

Write-off of receivables.

Change from the percentage-of-completion to the completed-contract method for reporting net income.

Discuss briefly the three approaches that have been suggested for reporting changes in accounting principles.

Identify and describe the approach the FASB requires for reporting changes in accounting principles.

What is the indirect effect of a change in accounting principle? Briefly describe the reporting of the indirect effects of a change in accounting principle.

Define a change in estimate and provide an illustration. When is a change in accounting estimate effected by a change in accounting principle?

Lenexa State Bank has followed the practice of capitalizing certain marketing costs and amortizing these costs over their expected life. In the current year, the bank determined that the future benefits from these costs were doubtful. Consequently, the bank adopted the policy of expensing these costs as incurred. How should the bank report this accounting change in the comparative financial statements?

Indicate how the following items are recorded in the accounting records in the current year of Coronet Co.

Impairment of goodwill.

A change in depreciating plant assets from accelerated to the straight-line method.

Large write-off of inventories because of obsolescence.

Change from the cash basis to accrual basis of accounting.

Change from LIFO to FIFO method for inventory valuation purposes.

Change in the estimate of service lives for plant assets.

Whittier Construction Co. had followed the practice of expensing all materials assigned to a construction job without recognizing any salvage inventory. On December 31, 2010, it was determined that salvage inventory should be valued at $52,000. Of this amount, $29,000 arose during the current year. How does this information affect the financial statements to be prepared at the end of 2010?

Parsons Inc. wishes to change from the completed-contract to the percentage-of-completion method for financial reporting purposes. The auditor indicates that a change would be permitted only if it is to a preferable method. What difficulties develop in assessing preferability?

Discuss how a change to the LIFO method of inventory valuation is handled when it is impracticable to determine previous LIFO inventory amounts.

How should consolidated financial statements be reported this year when statements of individual companies were presented last year?

Simms Corp. controlled four domestic subsidiaries and one foreign subsidiary. Prior to the current year, Simms Corp. had excluded the foreign subsidiary from consolidation. During the current year, the foreign subsidiary was included in the financial statements. How should this change in accounting entity be reflected in the financial statements?

Distinguish between counterbalancing and noncounter-balancing errors. Give an example of each.

Discuss and illustrate how a correction of an error in previously issued financial statements should be handled.

Prior to 2010, Heberling Inc. excluded manufacturing overhead costs from work in process and finished goods inventory. These costs have been expensed as incurred. In 2010, the company decided to change its accounting methods for manufacturing inventories to full costing by including these costs as product costs. Assuming that these costs are material, how should this change be reflected in the financial statements for 2009 and 2010?

Elliott Corp. failed to record accrued salaries for 2009, $2,000; 2010, $2,100; and 2011, $3,900. What is the amount of the overstatement or understatement of Retained Earnings at December 31, 2012?