LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

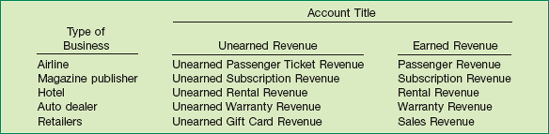

The question, "What is a liability?" is not easy to answer. For example, is preferred stock a liability or an ownership claim? The first reaction is to say that preferred stock is in fact an ownership claim, and companies should report it as part of stockholders' equity. In fact, preferred stock has many elements of debt as well.[186] The issuer (and in some cases the holder) often has the right to call the stock within a specific period of time—making it similar to a repayment of principal. The dividend on the preferred stock is in many cases almost guaranteed (the cumulative provision)—making it look like interest. As a result, preferred stock is but one of many financial instruments that are difficult to classify.[187]

To help resolve some of these controversies, the FASB, as part of its conceptual framework study, defined liabilities as "probable future sacrifices of economic benefits arising from present obligations of a particular entity to transfer assets or provide services to other entities in the future as a result of past transactions or events."[188] In other words, a liability has three essential characteristics:

It is a present obligation that entails settlement by probable future transfer or use of cash, goods, or services.

It is an unavoidable obligation.

The transaction or other event creating the obligation has already occurred.

Because liabilities involve future disbursements of assets or services, one of their most important features is the date on which they are payable. A company must satisfy currently maturing obligations in the ordinary course of business to continue operating. Liabilities with a more distant due date do not, as a rule, represent a claim on the company's current resources. They are therefore in a slightly different category. This feature gives rise to the basic division of liabilities into (1) current liabilities and (2) long-term debt.

Recall that current assets are cash or other assets that companies reasonably expect to convert into cash, sell, or consume in operations within a single operating cycle or within a year (if completing more than one cycle each year). Current liabilities are "obligations whose liquidation is reasonably expected to require use of existing resources properly classified as current assets, or the creation of other current liabilities." [2] This definition has gained wide acceptance because it recognizes operating cycles of varying lengths in different industries. This definition also considers the important relationship between current assets and current liabilities. [3]

The operating cycle is the period of time elapsing between the acquisition of goods and services involved in the manufacturing process and the final cash realization resulting from sales and subsequent collections. Industries that manufacture products requiring an aging process, and certain capital-intensive industries, have an operating cycle of considerably more than one year. On the other hand, most retail and service establishments have several operating cycles within a year.

Here are some typical current liabilities:

Accounts payable, or trade accounts payable, are balances owed to others for goods, supplies, or services purchased on open account. Accounts payable arise because of the time lag between the receipt of services or acquisition of title to assets and the payment for them. The terms of the sale (e.g., 2/10, n/30 or 1/10, E.O.M.) usually state this period of extended credit, commonly 30 to 60 days.

Most companies record liabilities for purchases of goods upon receipt of the goods. If title has passed to the purchaser before receipt of the goods, the company should record the transaction at the time of title passage. A company must pay special attention to transactions occurring near the end of one accounting period and at the beginning of the next. It needs to ascertain that the record of goods received (the inventory) agrees with the liability (accounts payable), and that it records both in the proper period.

Measuring the amount of an account payable poses no particular difficulty. The invoice received from the creditor specifies the due date and the exact outlay in money that is necessary to settle the account. The only calculation that may be necessary concerns the amount of cash discount. See Chapter 8 for illustrations of entries related to accounts payable and purchase discounts.

Notes payable are written promises to pay a certain sum of money on a specified future date. They may arise from purchases, financing, or other transactions. Some industries require notes (often referred to as trade notes payable) as part of the sales/purchases transaction in lieu of the normal extension of open account credit. Notes payable to banks or loan companies generally arise from cash loans. Companies classify notes as short-term or long-term, depending on the payment due date. Notes may also be interest-bearing or zero-interest-bearing.

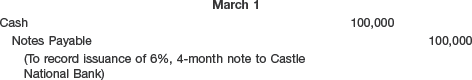

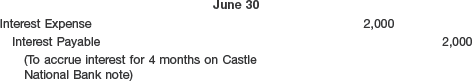

Assume that Castle National Bank agrees to lend $100,000 on March 1, 2010, to Landscape Co. if Landscape signs a $100,000, 6 percent, four-month note. Landscape records the cash received on March 1 as follows:

If Landscape prepares financial statements semiannually, it makes the following adjusting entry to recognize interest expense and interest payable of $2,000 ($100,000 × 6% × 4/12) at June 30:

If Landscape prepares financial statements monthly, its adjusting entry at the end of each month is $500 ($100,000 × 6% × 1/12).

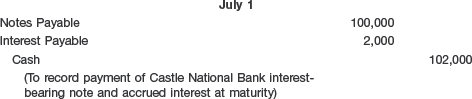

At maturity (July 1), Landscape must pay the face value of the note ($100,000) plus $2,000 interest ($100,000 × 6% × 4/12). Landscape records payment of the note and accrued interest as follows.

A company may issue a zero-interest-bearing note instead of an interest-bearing note. A zero-interest-bearing note does not explicitly state an interest rate on the face of the note. Interest is still charged, however. At maturity the borrower must pay back an amount greater than the cash received at the issuance date. In other words, the borrower receives in cash the present value of the note. The present value equals the face value of the note at maturity minus the interest or discount charged by the lender for the term of the note. In essence, the bank takes its fee "up front" rather than on the date the note matures.

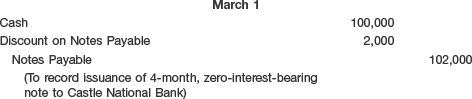

To illustrate, assume that Landscape issues a $102,000, four-month, zero-interest-bearing note to Castle National Bank. The present value of the note is $100,000.[189] Landscape records this transaction as follows.

Landscape credits the Notes Payable account for the face value of the note, which is $2,000 more than the actual cash received. It debits the difference between the cash received and the face value of the note to Discount on Notes Payable. Discount on Notes Payable is a contra account to Notes Payable, and therefore is subtracted from Notes Payable on the balance sheet. Illustration 13-1 shows the balance sheet presentation on March 1.

The amount of the discount, $2,000 in this case, represents the cost of borrowing $100,000 for 4 months. Accordingly, Landscape charges the discount to interest expense over the life of the note. That is, the Discount on Notes Payable balance represents interest expense chargeable to future periods. Thus, Landscape should not debit Interest Expense for $2,000 at the time of obtaining the loan. We discuss additional accounting issues related to notes payable in Chapter 14.

PepsiCo reports as part of its current liabilities the portion of bonds, mortgage notes, and other long-term indebtedness that matures within the next fiscal year. It categorizes this amount as current maturities of long-term debt. Companies, like PepsiCo, exclude long-term debts maturing currently as current liabilities if they are to be:

retired by assets accumulated for this purpose that properly have not been shown as current assets,

refinanced, or retired from the proceeds of a new debt issue, or

converted into capital stock.

In these situations, the use of current assets or the creation of other current liabilities does not occur. Therefore, classification as a current liability is inappropriate. A company should disclose the plan for liquidation of such a debt either parenthetically or by a note to the financial statements. When only a part of a long-term debt is to be paid within the next 12 months, as in the case of serial bonds that it retires through a series of annual installments, the company reports the maturing portion of long-term debt as a current liability, and the remaining portion as a long-term debt.

However, a company should classify as current any liability that is due on demand (callable by the creditor) or will be due on demand within a year (or operating cycle, if longer). Liabilities often become callable by the creditor when there is a violation of the debt agreement. For example, most debt agreements specify a given level of equity to debt be maintained, or specify that working capital be of a minimum amount. If the company violates an agreement, it must classify the debt as current because it is a reasonable expectation that existing working capital will be used to satisfy the debt. Only if a company can show that it is probable that it will cure (satisfy) the violation within the grace period specified in the agreements can it classify the debt as noncurrent. [4]

Short-term obligations are debts scheduled to mature within one year after the date of a company's balance sheet or within its operating cycle, whichever is longer. Some short-term obligations are expected to be refinanced on a long-term basis. These short-term obligations will not require the use of working capital during the next year (or operating cycle).[190]

At one time, the accounting profession generally supported the exclusion of short-term obligations from current liabilities if they were "expected to be refinanced." But the profession provided no specific guidelines, so companies determined whether a short-term obligation was "expected to be refinanced" based solely on management's intent to refinance on a long-term basis. Classification was not clear-cut. For example, a company might obtain a five-year bank loan but handle the actual financing with 90-day notes, which it must keep turning over (renewing). In this case, is the loan a long-term debt or a current liability? Another example was the Penn Central Railroad before it went bankrupt. The railroad was deep into short-term debt but classified it as long-term debt. Why? Because the railroad believed it had commitments from lenders to keep refinancing the short-term debt. When those commitments suddenly disappeared, it was "good-bye Pennsy." As the Greek philosopher Epictetus once said, "Some things in this world are not and yet appear to be."

To resolve these classification problems, the accounting profession has developed authoritative criteria for determining the circumstances under which short-term obligations may be properly excluded from current liabilities. A company is required to exclude a short-term obligation from current liabilities if both of the following conditions are met:

It must intend to refinance the obligation on a long-term basis.

It must demonstrate an ability to consummate the refinancing. [5]

Intention to refinance on a long-term basis means that the company intends to refinance the short-term obligation so that it will not require the use of working capital during the ensuing fiscal year (or operating cycle, if longer).

The company demonstrates the ability to consummate the refinancing by:

Actually refinancing the short-term obligation by issuing a long-term obligation or equity securities after the date of the balance sheet but before it is issued; or

Entering into a financing agreement that clearly permits the company to refinance the debt on a long-term basis on terms that are readily determinable.

If an actual refinancing occurs, the portion of the short-term obligation to be excluded from current liabilities may not exceed the proceeds from the new obligation or equity securities used to retire the short-term obligation. For example, Montavon Winery had $3,000,000 of short-term debt. Subsequent to the balance sheet date, but before issuing the balance sheet, the company issued 100,000 shares of common stock, intending to use the proceeds to liquidate the short-term debt at its maturity. If Montavon's net proceeds from the sale of the 100,000 shares total $2,000,000, it can exclude from current liabilities only $2,000,000 of the short-term debt.

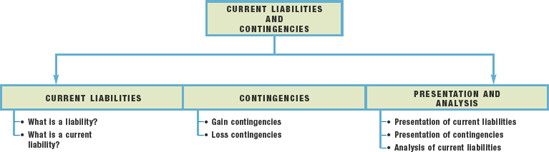

An additional question is whether a company should exclude from current liabilities a short-term obligation if it is paid off after the balance sheet date and replaced by long-term debt before the balance sheet is issued. To illustrate, Marquardt Company pays off short-term debt of $40,000 on January 17, 2011, and issues long-term debt of $100,000 on February 3, 2011. Marquardt's financial statements, dated December 31, 2010, are to be issued March 1, 2011. Should Marquardt exclude the $40,000 short-term debt from current liabilities? No—here's why: Repayment of the short-term obligation required the use of existing current assets before the company obtained funds through long-term financing. Therefore, Marquardt must include the short-term obligations in current liabilities at the balance sheet date (see graphical presentation below).

The evaluation of credit quality involves more than simply assessing a company's ability to repay loans. Credit analysts also evaluate debt management strategies. Analysts and investors will reward what they view as prudent management decisions with lower debt service costs and a higher stock price. The wrong decisions can bring higher debt costs and lower stock prices.

General Electric Capital Corp., a subsidiary of General Electric, experienced the negative effects of market scrutiny of its debt management policies. Analysts complained that GE had been slow to refinance its mountains of short-term debt. GE had issued these current obligations, with maturities of 270 days or less, when interest rates were low. However, in light of expectations that the Fed would raise interest rates, analysts began to worry about the higher interest costs GE would pay when it refinanced these loans. Some analysts recommended that it was time to reduce dependence on short-term credit. The reasoning goes that a shift to more dependable long-term debt, thereby locking in slightly higher rates for the long-term, is the better way to go.

Thus, scrutiny of GE debt strategies led to analysts' concerns about GE's earnings prospects. Investors took the analysis to heart, and GE experienced a 2-day 6 percent drop in its stock price.

Source: Adapted from Steven Vames, "Credit Quality, Stock Investing Seem to Go Hand in Hand," Wall Street Journal (April 1, 2002), p. R4.

A cash dividend payable is an amount owed by a corporation to its stockholders as a result of board of directors' authorization. At the date of declaration the corporation assumes a liability that places the stockholders in the position of creditors in the amount of dividends declared. Because companies always pay cash dividends within one year of declaration (generally within three months), they classify them as current liabilities.

On the other hand, companies do not recognize accumulated but undeclared dividends on cumulative preferred stock as a liability. Why? Because preferred dividends in arrears are not an obligation until the board of directors authorizes the payment. Nevertheless, companies should disclose the amount of cumulative dividends unpaid in a note, or show it parenthetically in the capital stock section.

Dividends payable in the form of additional shares of stock are not recognized as a liability. Such stock dividends (as we discuss in Chapter 15) do not require future outlays of assets or services. Companies generally report such undistributed stock dividends in the stockholders' equity section because they represent retained earnings in the process of transfer to paid-in capital.

Current liabilities may include returnable cash deposits received from customers and employees. Companies may receive deposits from customers to guarantee performance of a contract or service or as guarantees to cover payment of expected future obligations. For example, a company like Alltel Corp. often requires a deposit on equipment that customers use to connect to the Internet or to access its other services. Alltel also may receive deposits from customers as guarantees for possible damage to property. Additionally, some companies require their employees to make deposits for the return of keys or other company property.

The classification of these items as current or noncurrent liabilities depends on the time between the date of the deposit and the termination of the relationship that required the deposit.

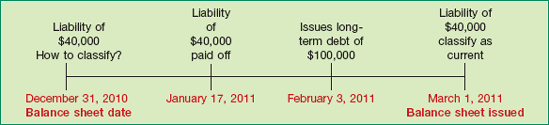

A magazine publisher, such as Golf Digest, receives payment when a customer subscribes to its magazines. An airline company, such as American Airlines, sells tickets for future flights. And software companies, like Microsoft, issue coupons that allow customers to upgrade to the next version of their software. How do these companies account for unearned revenues that they receive before delivering goods or rendering services?

Upon receipt of the advance, debit Cash, and credit a current liability account identifying the source of the unearned revenue.

Upon earning the revenue, debit the unearned revenue account, and credit an earned revenue account.

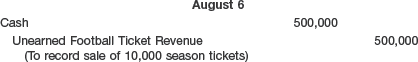

To illustrate, assume that Allstate University sells 10,000 season football tickets at $50 each for its five-game home schedule. Allstate University records the sales of season tickets as follows:

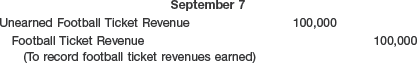

After each game, Allstate University makes the following entry.

Unearned Football Ticket Revenue is, therefore, unearned revenue. Allstate University reports it as a current liability in the balance sheet. As revenue is earned, a transfer from unearned revenue to earned revenue occurs. Unearned revenue is material for some companies: In the airline industry, tickets sold for future flights represent almost 50 percent of total current liabilities.

Illustration 13-3 shows specific unearned and earned revenue accounts used in selected types of businesses.

The balance sheet should report obligations for any commitments that are redeemable in goods and services. The income statement should report revenues earned during the period.

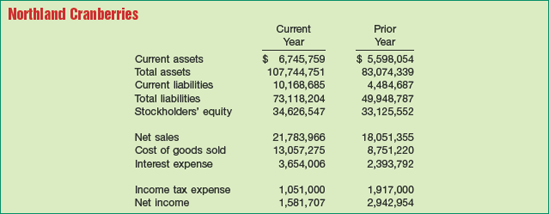

Users of financial statements generally examine current liabilities to assess a company's liquidity and overall financial flexibility. Companies must pay many current liabilities, such as accounts payable, wages payable, and taxes payable, sooner rather than later. A substantial increase in these liabilities should raise a red flag about a company's financial position.

This is not the case for all current liabilities. For example, Microsoft has a current liability entitled "Unearned revenue" that has increased substantially year after year. Unearned revenue is a liability that arises from sales of Microsoft products such as Windows and Office. Microsoft also has provided coupons for upgrades to its programs to bolster sales of its Xbox consoles. At the time of a sale, customers pay not only for the current version of the software but also for future upgrades. Microsoft recognizes sales revenue from the current version of the software and records as a liability (unearned revenue) the value of future upgrades to the software that it "owes" to customers.

Market analysts read such an increase in unearned revenue as a positive signal about Microsoft's sales and profitability. When Microsoft's sales are growing, its unearned revenue account increases. Thus, an increase in a liability is good news about Microsoft sales. At the same time, a decline in unearned revenue is bad news. As one analyst noted, a slowdown or reversal of the growth in Microsoft's unearned revenues indicates slowing sales, which is bad news for investors. Thus, increases in current liabilities can sometimes be viewed as good signs instead of bad.

Source: Adapted from David Bank, "Some Fans Cool to Microsoft, Citing Drop in Old Indicator," Wall Street Journal (October 28, 1999); and Bloomberg News, "Microsoft Profit Hit by Deferred Sales; Forecast Raised," The Globe and Mail (January 26, 2007), p. B8.

Retailers like Wal-Mart, Circuit City, and GAP must collect sales taxes from customers on transfers of tangible personal property and on certain services and then must remit these taxes to the proper governmental authority. GAP, for example, sets up a liability to provide for taxes collected from customers but not yet remitted to the tax authority. The Sales Taxes Payable account should reflect the liability for sales taxes due various governments.

The entry below illustrates use of the Sales Taxes Payable account on a sale of $3,000 when a 4 percent sales tax is in effect.

Sometimes the sales tax collections credited to the liability account are not equal to the liability as computed by the governmental formula. In such a case, GAP makes an adjustment of the liability account by recognizing a gain or a loss on sales tax collections.

Many companies do not segregate the sales tax and the amount of the sale at the time of sale. Instead, the company credits both amounts in total in the Sales account. Then, to reflect correctly the actual amount of sales and the liability for sales taxes, the company would debit the Sales account for the amount of the sales taxes due the government on these sales, and would credit the Sales Taxes Payable account for the same amount.

To illustrate, assume that the Sales account balance of $150,000 includes sales taxes of 4 percent. Thus, the amount recorded in the Sales account is comprised of the sales amount plus sales tax of 4 percent of the sales amount. Sales therefore are $144,230.77 ($150,000 ÷ 1.04) and the sales tax liability is $5,769.23 ($144,230.77 × 0.04; or $150,000 − $144,230.77). The following entry would record the amount due the taxing unit.

Any federal or state income tax varies in proportion to the amount of annual income. Using the best information and advice available, a business must prepare an income tax return and compute the income tax payable resulting from the operations of the current period. Corporations should classify as a current liability the taxes payable on net income, as computed per the tax return.[191] Unlike a corporation, proprietorships and partnerships are not taxable entities. Because the individual proprietor and the members of a partnership are subject to personal income taxes on their share of the business's taxable income, income tax liabilities do not appear on the financial statements of proprietorships and partnerships.

Most corporations must make periodic tax payments throughout the year in an authorized bank depository or a Federal Reserve Bank. These payments are based upon estimates of the total annual tax liability. As the estimated total tax liability changes, the periodic contributions also change. If in a later year the taxing authority assesses an additional tax on the income of an earlier year, the company should credit Income Taxes Payable and charge the related debit to current operations.

Differences between taxable income under the tax laws and accounting income under generally accepted accounting principles sometimes occur. Because of these differences, the amount of income tax payable to the government in any given year may differ substantially from income tax expense as reported on the financial statements. Chapter 19 is devoted solely to income tax matters and presents an extensive discussion of this complex topic.

Companies also report as a current liability amounts owed to employees for salaries or wages at the end of an accounting period. In addition, they often also report as current liabilities the following items related to employee compensation.

Payroll deductions.

Compensated absences.

Bonuses.

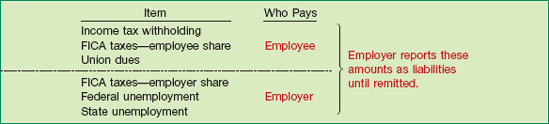

The most common types of payroll deductions are taxes, insurance premiums, employee savings, and union dues. To the extent that a company has not remitted the amounts deducted to the proper authority at the end of the accounting period, it should recognize them as current liabilities.

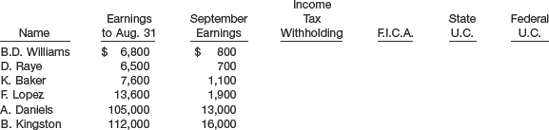

Social Security Taxes. Since January 1, 1937, Social Security legislation has provided federal Old Age, Survivor, and Disability Insurance (O.A.S.D.I.) benefits for certain individuals and their families. Funds for these payments come from taxes levied on both the employer and the employee. Employers collect the employee's share of this tax by deducting it from the employee's gross pay, and remit it to the government along with their share. The government taxes both the employer and the employee at the same rate, currently 6.2 percent based on the employee's gross pay up to a $102,000 annual limit. The O.A.S.D.I. tax is usually referred to as F.I.C.A. (the Federal Insurance Contribution Act).

In 1965 Congress passed the first federal health insurance program for the aged—popularly known as Medicare. This two-part program alleviates the high cost of medical care for those over age 65. A separate Hospital Insurance tax, paid by both the employee and the employer at the rate of 1.45 percent on the employee's total compensation, finances the Basic Plan, which provides hospital and other institutional services. The Voluntary Plan covers the major part of doctors' bills and other medical and health services. Monthly payments from all who enroll, plus matching funds from the federal government, finance this plan.

The combination of the O.A.S.D.I. tax (F.I.C.A.) and the federal Hospital Insurance Tax is commonly referred to as the Social Security tax. The combined rate for these taxes, 7.65 percent on an employee's wages to $102,000 and 1.45 percent in excess of $102,000, changes intermittently by acts of Congress. Companies should report the amount of unremitted employee and employer Social Security tax on gross wages paid as a current liability.

Unemployment Taxes. Another payroll tax levied by the federal government in cooperation with state governments provides a system of unemployment insurance. All employers who meet the following criteria are subject to the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (F.U.T.A.): (1) those who paid wages of $1,500 or more during any calendar quarter in the year or preceding year, or (2) those who employed at least one individual on at least one day in each of 20 weeks during the current or preceding calendar year.

Only employers pay the unemployment tax. The rate of this tax is 6.2 percent on the first $7,000 of compensation paid to each employee during the calendar year. The employer receives a tax credit not to exceed 5.4 percent for contributions paid to a state plan for unemployment compensation. Thus, if an employer is subject to a state unemployment tax of 5.4 percent or more, it pays only 0.8 percent tax to the federal government.

State unemployment compensation laws differ both from the federal law and among various states. Therefore, employers must refer to the unemployment tax laws in each state in which they pay wages and salaries. The normal state tax may range from 3 percent to 7 percent or higher. However, all states provide for some form of merit rating, which reduces the state contribution rate. Employers who display by their benefit and contribution experience that they provide steady employment may receive this reduction—if the size of the state fund is adequate. In order not to penalize an employer who has earned a reduction in the state contribution rate, federal law allows a credit of 5.4 percent, even when the effective state contribution rate is less than 5.4 percent.

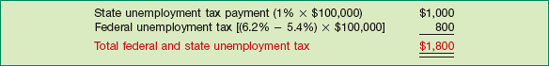

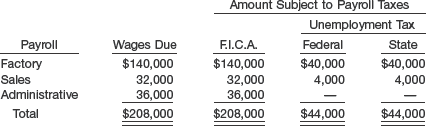

To illustrate, Appliance Repair Co. has a taxable payroll of $100,000. It is subject to a federal rate of 6.2 percent and a state contribution rate of 5.7 percent. However, its stable employment experience reduces the company's state rate to 1 percent. Appliance Repair computes its federal and state unemployment taxes as shown in Illustration 13-4.

Companies pay federal unemployment tax quarterly, and file a tax form annually. Companies also generally pay state contributions quarterly as well. Because both the federal and the state unemployment taxes accrue on earned compensation, companies should record the amount of accrued but unpaid employer contributions as an operating expense and as a current liability when preparing financial statements at year-end.

Income Tax Withholding. Federal and some state income tax laws require employers to withhold from each employee's pay the applicable income tax due on those wages. The employer computes the amount of income tax to withhold according to a government-prescribed formula or withholding tax table. That amount depends on the length of the pay period and each employee's taxable wages, marital status, and claimed dependents. If the income tax withheld plus the employee and the employer Social Security taxes exceeds specified amounts per month, the employer must make remittances to the government during the month. Illustration 13-5 summarizes payroll deductions and liabilities.

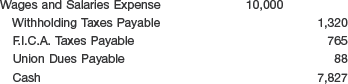

Payroll Deductions Example. Assume a weekly payroll of $10,000 entirely subject to F.I.C.A. and Medicare (7.65%), federal (0.8%) and state (4%) unemployment taxes, with income tax withholding of $1,320 and union dues of $88 deducted. The company records the wages and salaries paid and the employee payroll deductions as follows:

It records the employer payroll taxes as follows:

The employer must remit to the government its share of F.I.C.A. tax along with the amount of F.I.C.A. tax deducted from each employee's gross compensation. It should record all unremitted employer F.I.C.A. taxes as payroll tax expense and payroll tax payable.[192]

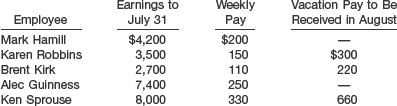

Compensated absences are paid absences from employment—such as vacation, illness, and holidays. Companies should accrue a liability for the cost of compensation for future absences if all of the following conditions exist. [6]

The employer's obligation relating to employees' rights to receive compensation for future absences is attributable to employees' services already rendered.

The obligation relates to the rights that vest or accumulate.

Payment of the compensation is probable.

The amount can be reasonably estimated. [7][193]

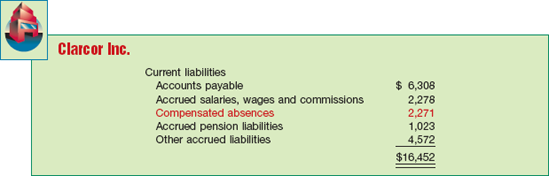

Illustration 13-6 shows an example of an accrual for compensated absences, in an excerpt from the balance sheet of Clarcor Inc.

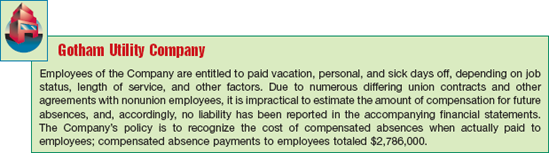

If an employer meets conditions (a), (b), and (c) but does not accrue a liability because of a failure to meet condition (d), it should disclose that fact. Illustration 13-7 shows an example of such a disclosure, in a note from the financial statements of Gotham Utility Company.

The following considerations are relevant to the accounting for compensated absences.

Vested rights exist when an employer has an obligation to make payment to an employee even after terminating his or her employment. Thus, vested rights are not contingent on an employee's future service. Accumulated rights are those that employees can carry forward to future periods if not used in the period in which earned. For example, assume that you earn four days of vacation pay as of December 31, the end of your employer's fiscal year. Company policy is that you will be paid for this vacation time even if you terminate employment. In this situation, your four days of vacation pay are vested, and your employer must accrue the amount.

Now assume that your vacation days are not vested, but that you can carry the four days over into later periods. Although the rights are not vested, they are accumulated rights for which the employer must make an accrual. However, the amount of the accrual is adjusted to allow for estimated forfeitures due to turnover.

A modification of the general rules relates to the issue of sick pay. If sick pay benefits vest, a company must accrue them. If sick pay benefits accumulate but do not vest, a company may choose whether to accrue them. Why this distinction? Companies may administer compensation designated as sick pay in one of two ways. In some companies, employees receive sick pay only if illness causes their absence. Therefore, these companies may or may not accrue a liability because its payment depends on future employee illness. Other companies allow employees to accumulate unused sick pay and take compensated time off from work even when not ill. For this type of sick pay, a company must accrue a liability because the company will pay it, regardless of whether employees become ill.

Companies should recognize the expense and related liability for compensated absences in the year earned by employees. For example, if new employees receive rights to two weeks' paid vacation at the beginning of their second year of employment, a company considers the vacation pay to be earned during the first year of employment.

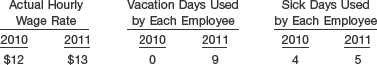

What rate should a company use to accrue the compensated absence cost—the current rate or an estimated future rate? GAAP is silent on this subject. Therefore, companies will likely use the current rather than future rate. The future rate is less certain and raises time value of money issues. To illustrate, assume that Amutron Inc. began operations on January 1, 2010. The company employs 10 individuals and pays each $480 per week. Employees earned 20 unused vacation weeks in 2010. In 2011, the employees used the vacation weeks, but now they each earn $540 per week. Amutron accrues the accumulated vacation pay on December 31, 2010, as follows.

At December 31, 2010, the company reports on its balance sheet a liability of $9,600. In 2011, it records the payment of vacation pay as follows.

In 2011 the use of the vacation weeks extinguishes the liability. Note that Amutron records the difference between the amount of cash paid and the reduction in the liability account as an adjustment to Wages Expense in the period when paid. This difference arises because it accrues the liability account at the rates of pay in effect during the period when employees earned the compensated time. The cash paid, however, depends on the rates in effect during the period when employees used the compensated time. If Amutron used the future rates of pay to compute the accrual in 2010, then the cash paid in 2011 would equal the liability.[194]

Many companies give a bonus to certain or all employees in addition to their regular salaries or wages. Frequently the bonus amount depends on the company's yearly profit. For example, employees at Ford Motor Company share in the success of the company's operations on the basis of a complicated formula using net income as its primary basis for computation. A company may consider bonus payments to employees as additional wages and should include them as a deduction in determining the net income for the year.

To illustrate the entries for an employee bonus, assume that Palmer Inc. shows income for the year 2010 of $100,000. It will pay out bonuses of $10,700 in January 2011. Palmer makes an adjusting entry dated December 31, 2010, to record the bonuses as follows.

In January 2011, when Palmer pays the bonus, it makes this journal entry:

Palmer should show the expense account in the income statement as an operating expense. The liability, Profit-Sharing Bonus Payable, is usually payable within a short period of time. Companies should include it as a current liability in the balance sheet. Similar to bonus agreements are contractual agreements for conditional expenses. Examples would be agreements covering rents or royalty payments conditional on the amount of revenues earned or the quantity of product produced or extracted. Conditional expenses based on revenues or units produced are usually less difficult to compute than bonus arrangements.

For example, assume that a lease calls for a fixed rent payment of $500 per month and 1 percent of all sales over $300,000 per year. The company's annual rent obligation would amount to $6,000 plus $0.01 of each dollar of revenue over $300,000. Or, a royalty agreement may give to a patent owner $1 for every ton of product resulting from the patented process, or give to a mineral rights owner $0.50 on every barrel of oil extracted. As the company produces or extracts each additional unit of product, it creates an additional obligation, usually a current liability.

Companies often are involved in situations where uncertainty exists about whether an obligation to transfer cash or other assets has arisen and/or the amount that will be required to settle the obligation. For example:

Merck may be a defendant in a lawsuit, and any payment is contingent upon the outcome of a settlement or an administrative or court proceeding.

Ford Motor Co. provides a warranty for a car it sells, and any payments are contingent on the number of cars that qualify for benefits under the warranty.

Briggs & Stratton acts as a guarantor on a loan for another entity, and any payment is contingent on whether the other entity defaults.

Broadly, these situations are called contingencies. A contingency is "an existing condition, situation, or set of circumstances involving uncertainty as to possible gain (gain contingency) or loss (loss contingency) to an enterprise that will ultimately be resolved when one or more future events occur or fail to occur." [8][195]

Gain contingencies are claims or rights to receive assets (or have a liability reduced) whose existence is uncertain but which may become valid eventually. The typical gain contingencies are:

Possible receipts of monies from gifts, donations, bonuses, and so on.

Possible refunds from the government in tax disputes.

Pending court cases with a probable favorable outcome.

Tax loss carryforwards (discussed in Chapter 19).

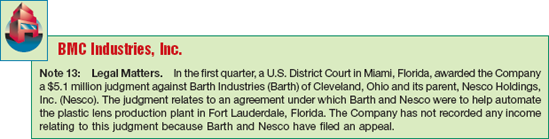

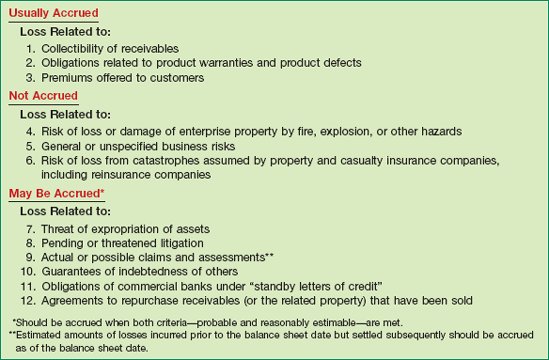

Companies follow a conservative policy in this area. Except for tax loss carryforwards, they do not record gain contingencies. A company discloses gain contingencies in the notes only when a high probability exists for realizing them. As a result, it is unusual to find information about contingent gains in the financial statements and the accompanying notes. Illustration 13-8 presents an example of a gain contingency disclosure.

Loss contingencies involve possible losses. A liability incurred as a result of a loss contingency is by definition a contingent liability. Contingent liabilities depend on the occurrence of one or more future events to confirm either the amount payable, the payee, the date payable, or its existence. That is, these factors depend on a contingency.

When a loss contingency exists, the likelihood that the future event or events will confirm the incurrence of a liability can range from probable to remote. The FASB uses the terms probable, reasonably possible, and remote to identify three areas within that range and assigns the following meanings.

Probable. The future event or events are likely to occur.

Reasonably possible. The chance of the future event or events occurring is more than remote but less than likely.

Remote. The chance of the future event or events occurring is slight.

Companies should accrue an estimated loss from a loss contingency by a charge to expense and a liability recorded only if both of the following conditions are met.[196]

Information available prior to the issuance of the financial statements indicates that it is probable that a liability has been incurred at the date of the financial statements.

The amount of the loss can be reasonably estimated.

To record a liability, a company does not need to know the exact payee nor the exact date payable. What a company must know is whether it is probable that it incurred a liability.

To meet the second criterion, a company needs to be able to reasonably determine an amount for the liability. To determine a reasonable estimate of the liability, a company may use its own experience, experience of other companies in the industry, engineering or research studies, legal advice, or educated guesses by qualified personnel. Illustration 13-9 shows an accrual recorded for a loss contingency, from the annual report of Quaker State Oil Refining Company.

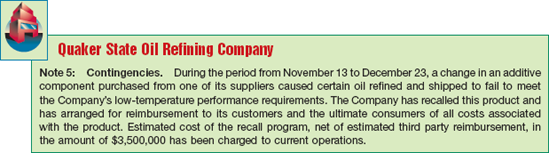

Use of the terms probable, reasonably possible, and remote to classify contingencies involves judgment and subjectivity. Illustration 13-10 lists examples of loss contingencies and the general accounting treatment accorded them.

Practicing accountants express concern over the diversity that now exists in the interpretation of "probable," "reasonably possible," and "remote." Current practice relies heavily on the exact language used in responses received from lawyers (such language is necessarily biased and protective rather than predictive). As a result, accruals and disclosures of contingencies vary considerably in practice. Some of the more common loss contingencies are:[197]

Litigation, claims, and assessments.

Guarantee and warranty costs.

Premiums and coupons.

Environmental liabilities.

As discussed in the opening story, companies do not record or report in the notes to the financial statements general risk contingencies inherent in business operations (e.g., the possibility of war, strike, uninsurable catastrophes, or a business recession).

Companies must consider the following factors, among others, in determining whether to record a liability with respect to pending or threatened litigation and actual or possible claims and assessments.

The time period in which the underlying cause of action occurred.

The probability of an unfavorable outcome.

The ability to make a reasonable estimate of the amount of loss.

To report a loss and a liability in the financial statements, the cause for litigation must have occurred on or before the date of the financial statements. It does not matter that the company became aware of the existence or possibility of the lawsuit or claims after the date of the financial statements but before issuing them. To evaluate the probability of an unfavorable outcome, a company considers the following: the nature of the litigation; the progress of the case; the opinion of legal counsel; its own and others' experience in similar cases; and any management response to the lawsuit.

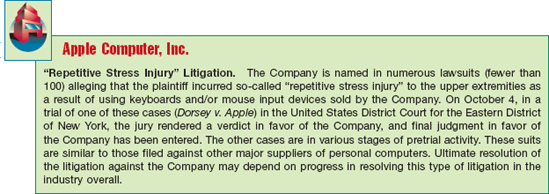

Companies can seldom predict the outcome of pending litigation, however, with any assurance. And, even if evidence available at the balance sheet date does not favor the company, it is hardly reasonable to expect the company to publish in its financial statements a dollar estimate of the probable negative outcome. Such specific disclosures might weaken the company's position in the dispute and encourage the plaintiff to intensify its efforts. A typical example of the wording of such a disclosure is the note to the financial statements of Apple Computer, Inc., relating to its litigation concerning repetitive stress injuries, as shown in Illustration 13-11.

With respect to unfiled suits and unasserted claims and assessments, a company must determine (1) the degree of probability that a suit may be filed or a claim or assessment may be asserted, and (2) the probability of an unfavorable outcome. For example, assume that the Federal Trade Commission investigates the Nawtee Company for restraint of trade, and institutes enforcement proceedings. Private claims of triple damages for redress often follow such proceedings. In this case, Nawtee must determine the probability of the claims being asserted and the probability of triple damages being awarded. If both are probable, if the loss is reasonably estimable, and if the cause for action is dated on or before the date of the financial statements, then Nawtee should accrue the liability.[198]

A warranty (product guarantee) is a promise made by a seller to a buyer to make good on a deficiency of quantity, quality, or performance in a product. Manufacturers commonly use it as a sales promotion technique. Automakers, for instance, "hyped" their sales by extending their new-car warranty to seven years or 100,000 miles. For a specified period of time following the date of sale to the consumer, the manufacturer may promise to bear all or part of the cost of replacing defective parts, to perform any necessary repairs or servicing without charge, to refund the purchase price, or even to "double your money back."

Warranties and guarantees entail future costs. These additional costs, sometimes called "after costs" or "post-sale costs," frequently are significant. Although the future cost is indefinite as to amount, due date, and even customer, a liability is probable in most cases. Companies should recognize this liability in the accounts if they can reasonably estimate it. The estimated amount of the liability includes all the costs that the company will incur after sale and delivery and that are incident to the correction of defects or deficiencies required under the warranty provisions. Warranty costs are a classic example of a loss contingency.

Companies use two basic methods of accounting for warranty costs: (1) the cash-basis method and (2) the accrual method.

Under the cash-basis method, companies expense warranty costs as incurred. In other words, a seller or manufacturer charges warranty costs to the period in which it complies with the warranty. The company does not record a liability for future costs arising from warranties, nor does it charge the period of sale. Companies frequently justify use of this method, the only one recognized for income tax purposes, on the basis of expediency when warranty costs are immaterial or when the warranty period is relatively short. A company must use the cash-basis method when it does not accrue a warranty liability in the year of sale either because:

it is not probable that a liability has been incurred, or

it cannot reasonably estimate the amount of the liability.

If it is probable that customers will make warranty claims and a company can reasonably estimate the costs involved, the company must use the accrual method. Under the accrual method, companies charge warranty costs to operating expense in the year of sale. The accrual method is the generally accepted method. Companies should use it whenever the warranty is an integral and inseparable part of the sale and is viewed as a loss contingency. We refer to this approach as the expense warranty approach.

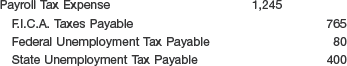

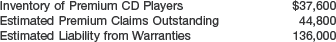

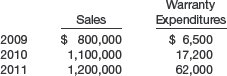

Example of Expense Warranty Approach. To illustrate the expense warranty method, assume that Denson Machinery Company begins production on a new machine in July 2010, and sells 100 units at $5,000 each by its year-end, December 31, 2010. Each machine is under warranty for one year. Denson estimates, based on past experience with a similar machine, that the warranty cost will average $200 per unit. Further, as a result of parts replacements and services rendered in compliance with machinery warranties, it incurs $4,000 in warranty costs in 2010 and $16,000 in 2011.

Sale of 100 machines at $5,000 each, July through December 2010:

Recognition of warranty expense, July through December 2010:

The December 31, 2010, balance sheet reports "Estimated liability under warranties" as a current liability of $16,000, and the income statement for 2010 reports "Warranty expense" of $20,000.

Recognition of warranty costs incurred in 2011 (on 2010 machinery sales):

If Denson Machinery applies the cash-basis method, it reports $4,000 as warranty expense in 2010 and $16,000 as warranty expense in 2011. It records all of the sale price as revenue in 2010. In many instances, application of the cash-basis method fails to match the warranty costs relating to the products sold during a given period with the revenues derived from such products. As such, it violates the expense recognition principle. Where ongoing warranty policies exist year after year, the differences between the cash and the expense warranty bases probably would not be so great.

Sales Warranty Approach. A warranty is sometimes sold separately from the product. For example, when you purchase a television set or DVD player, you are entitled to the manufacturer's warranty. You also will undoubtedly be offered an extended warranty on the product at an additional cost.[199]

In this case, the seller should recognize separately the sale of the television or DVD player, with the manufacturer's warranty and the sale of the extended warranty. [9] This approach is referred to as the sales warranty approach. Companies defer revenue on the sale of the extended warranty and generally recognize it on a straight-line basis over the life of the contract. The seller of the warranty defers revenue because it has an obligation to perform services over the life of the contract. The seller should only defer and amortize costs that vary with and are directly related to the sale of the contracts (mainly commissions). It expenses those costs, such as employees' salaries, advertising, and general and administrative expenses, that it would have incurred even if it did not sell a contract.

To illustrate, assume you purchase a new automobile from Hanlin Auto for $20,000. In addition to the regular warranty on the auto (the manufacturer will pay for all repairs for the first 36,000 miles or three years, whichever comes first), you purchase at a cost of $600 an extended warranty that protects you for an additional three years or 36,000 miles. Hanlin Auto records the sale of the automobile (with the regular warranty) and the sale of the extended warranty on January 2, 2010, as follows:

It recognizes revenue at the end of the fourth year (using straight-line amortization) as follows.

Because the extended warranty contract only starts after the regular warranty expires, Hanlin Auto defers revenue recognition until the fourth year. If it incurs the costs of performing services under the extended warranty contract on other than a straight-line basis (as historical evidence might indicate), Hanlin Auto should recognize revenue over the contract period in proportion to the costs it expected to incur in performing services under the contract. [10][200]

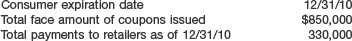

Numerous companies offer premiums (either on a limited or continuing basis) to customers in return for boxtops, certificates, coupons, labels, or wrappers. The premium may be silverware, dishes, a small appliance, a toy, or free transportation. Also, printed coupons that can be redeemed for a cash discount on items purchased are extremely popular. A more recent marketing innovation is the cash rebate, which the buyer can obtain by returning the store receipt, a rebate coupon, and Universal Product Code (UPC label) or "bar code" to the manufacturer.[201]

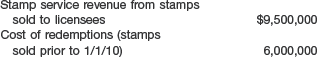

Companies offer premiums, coupon offers, and rebates to stimulate sales. Thus companies should charge the costs of premiums and coupons to expense in the period of the sale that benefits from the plan. The period that benefits is not necessarily the period in which the company offered the premium. At the end of the accounting period many premium offers may be outstanding and must be redeemed when presented in subsequent periods. In order to reflect the existing current liability and to match costs with revenues, the company estimates the number of outstanding premium offers that customers will present for redemption. The company then charges the cost of premium offers to Premium Expense. It credits the outstanding obligations to an account titled Liability for Premiums or Premium Liability.

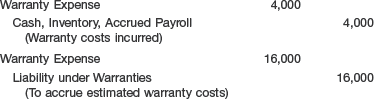

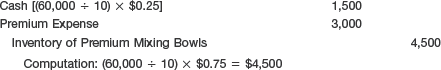

The following example illustrates the accounting treatment for a premium offer. Fluffy Cakemix Company offered its customers a large nonbreakable mixing bowl in exchange for 25 cents and 10 boxtops. The mixing bowl costs Fluffy Cakemix Company 75 cents, and the company estimates that customers will redeem 60 percent of the boxtops. The premium offer began in June 2010 and resulted in the transactions journalized below. Fluffy Cakemix Company records purchase of 20,000 mixing bowls at 75 cents as follows.

The entry to record sales of 300,000 boxes of cake mix at 80 cents would be:

Fluffy records the actual redemption of 60,000 boxtops, the receipt of 25 cents per 10 boxtops, and the delivery of the mixing bowls as follows.

Finally, Fluffy makes an end-of-period adjusting entry for estimated liability for outstanding premium offers (boxtops) as follows.

The December 31, 2010, balance sheet of Fluffy Cakemix Company reports an "Inventory of premium mixing bowls" of $10,500 as a current asset and "Liability for premiums" of $6,000 as a current liability. The 2010 income statement reports a $9,000 "Premium expense" among the selling expenses.

Numerous companies offer premiums to customers in the form of a promise of future goods or services as an incentive for purchases today. Premium plans that have widespread adoption are the frequent-flyer programs used by all major airlines. On the basis of mileage accumulated, frequent-flyer members receive discounted or free airline tickets. Airline customers can earn miles toward free travel by making long-distance phone calls, staying in hotels, and charging gasoline and groceries on a credit card. Those free tickets represent an enormous potential liability because people using them may displace paying passengers.

When airlines first started offering frequent-flyer bonuses, everyone assumed that they could accommodate the free-ticket holders with otherwise-empty seats. That made the additional cost of the program so minimal that airlines didn't accrue it or report the small liability. But, as more and more paying passengers have been crowded off flights by frequent-flyer awardees, the loss of revenues has grown enormously. For example, United Airlines at one time reported a liability of $1.4 billion for advance ticket sales, some of which pertains to free frequent-flyer tickets.

Although the profession has studied the accounting for this transaction, no authoritative guidelines have been issued.

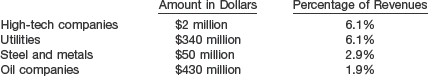

Estimates to clean up existing toxic waste sites total upward of $752 billion over a 30-year period. In addition, cost estimates of cleaning up our air and preventing future deterioration of the environment run even higher. Consider some average environmental costs per company for various industries:

These costs are likely to only grow, considering "Superfund legislation." This federal legislation provides the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) with the power to clean up waste sites and charge the clean-up costs to parties the EPA deems responsible for contaminating the site. These potentially responsible parties can have a significant liability.

In many industries, the construction and operation of long-lived assets involves obligations for the retirement of those assets. When a mining company opens up a strip mine, it may also commit to restore the land once it completes mining. Similarly, when an oil company erects an offshore drilling platform, it may be legally obligated to dismantle and remove the platform at the end of its useful life.

A company must recognize an asset retirement obligation (ARO) when it has an existing legal obligation associated with the retirement of a long-lived asset and when it can reasonably estimate the amount of the liability. Companies should record the ARO at fair value. [12]

Obligating Events. Examples of existing legal obligations, which require recognition of a liability include, but are not limited to:

decommissioning nuclear facilities,

dismantling, restoring, and reclamation of oil and gas properties,

certain closure, reclamation, and removal costs of mining facilities,

closure and post-closure costs of landfills.

In order to capture the benefits of these long-lived assets, the company is generally legally obligated for the costs associated with retirement of the asset, whether the company hires another party to perform the retirement activities or performs the activities with its own workforce and equipment. AROs give rise to various recognition patterns. For example, the obligation may arise at the outset of the asset's use (e.g., erection of an oil-rig), or it may build over time (e.g., a landfill that expands over time).

Measurement. A company initially measures an ARO at fair value, which is defined as the amount that the company would pay in an active market to settle the ARO. While active markets do not exist for many AROs, companies should estimate fair value based on the best information available. Such information could include market prices of similar liabilities, if available. Alternatively, companies may use present value techniques to estimate fair value.

Recognition and Allocation. To record an ARO in the financial statements, a company includes the cost associated with the ARO in the carrying amount of the related long-lived asset, and records a liability for the same amount. It records an asset retirement cost as part of the related asset because these costs are tied to operating the asset and are necessary to prepare the asset for its intended use. Therefore, the specific asset (e.g., mine, drilling platform, nuclear power plant) should be increased because the future economic benefit comes from the use of this productive asset. Companies should not record the capitalized asset retirement costs in a separate account because there is no future economic benefit that can be associated with these costs alone.

In subsequent periods, companies allocate the cost of the ARO to expense over the period of the related asset's useful life. Companies may use the straight-line method for this allocation, as well as other systematic and rational allocations.

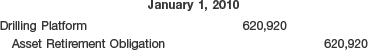

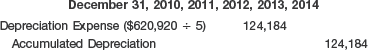

Example of ARO Accounting Provisions. To illustrate the accounting for AROs, assume that on January 1, 2010, Wildcat Oil Company erected an oil platform in the Gulf of Mexico. Wildcat is legally required to dismantle and remove the platform at the end of its useful life, estimated to be five years. Wildcat estimates that dismantling and removal will cost $1,000,000. Based on a 10 percent discount rate, the fair value of the asset retirement obligation is estimated to be $620,920 ($1,000,000 × .62092). Wildcat records this ARO as follows.

During the life of the asset, Wildcat allocates the asset retirement cost to expense. Using the straight-line method, Wildcat makes the following entries to record this expense.

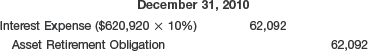

In addition, Wildcat must accrue interest expense each period. Wildcat records interest expense and the related increase in the asset retirement obligation on December 31, 2010, as follows.

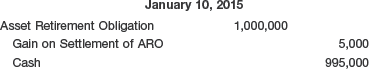

On January 10, 2015, Wildcat contracts with Rig Reclaimers, Inc. to dismantle the platform at a contract price of $995,000. Wildcat makes the following journal entry to record settlement of the ARO.

Companies need to provide more extensive disclosure regarding environmental liabilities. In addition, companies should record more of these liabilities. The SEC believes that companies should not delay recognition of a liability due to significant uncertainty. The SEC argues that if the liability is within a range, and no amount within the range is the best estimate, then management should recognize the minimum amount of the range. That treatment is in accordance with GAAP. The SEC also believes that companies should report environmental liabilities in the balance sheet independent of recoveries from third parties. Thus, companies may not net possible insurance recoveries against liabilities but must show them separately. Because there is much litigation regarding recovery of insurance proceeds, these "assets" appear to be gain contingencies. Therefore, companies should not report these on the balance sheet.[202]

On November 19, 2001, Enron filed its third-quarter financial statements and reported on its balance sheet debt of approximately $13 billion. Yet on the same day, at a meeting to discuss its liquidity crisis, Enron informed its bankers that its debt was approximately $38 billion. Company officers described the difference of $25 billion as being either off-balance-sheet or on the balance sheet other than debt.

As a result of the Enron bankruptcy and other financial reporting scandals, Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. One of its provisions mandates that the Securities and Exchange Commission conduct a study to determine the extent of off-balance-sheet transactions occurring in U.S. businesses.

Table 1 below indicates the extent of disclosure and recognition of contingent liabilities. The study classified contingent liabilities into three categories (1) litigation contingent liabilities, (2) environmental liabilities, and (3) guarantees. The statistics provided relate to reports filed by 10,100 companies listed on the U.S. stock exchanges in 2005.

Table 1. Table 1

Type of Contingency | Companies Disclosing | Companies Recording |

|---|---|---|

Litigation contingent liabilities | 46.3% | 5.1% |

Environmental contingent liabilities | 10.2% | 5.1% |

Guarantees | 35.4% | 10.2% |

As Table 1 indicates, approximately 46 percent of companies disclosed litigation contingent liabilities, but only 5.1 percent recorded any liability related to these contingencies. On the other hand, 35 percent of the companies disclosed guarantees but a third of these companies (10.2 percent) recorded a liability for these contingencies.

Table 2 below shows the dollar amounts of the contingent liabilities companies disclosed and recorded.

Table 2. Table 2

Type of Contingency | Companies Disclosing ($ millions) | Companies Recording ($ millions) |

|---|---|---|

Litigation contingent liabilities | $52,354 | $11,814 |

Environmental contingent liabilities | $23,414 | $18,723 |

Guarantees | $46,535,399 | $123,949 |

Table 2 indicates that companies disclosed litigation contingent liabilities of approximately $52 billion, but recorded only $11.8 billion as liabilities. Incredibly, companies disclosed more than $46 trillion of guarantees, a small fraction of which (just $124 billion) they recorded as liabilities.

The results of this study suggest that the FASB must continue to address the issue of contingencies to ensure that companies provide relevant and reliable information for these types of financial events.

Source: "Report and Recommendations Pursuant to Section 401(c) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 on Arrangements with Off-Balance Sheet Implications, Special Purpose Entities, and Transparency of Filings by Issuers," United States Securities and Exchange Commission, Office of Chief Accountant, Office of Economic Analyses, Division of Corporation Finance (June 2005).

As discussed earlier, contingencies are not recorded for general risks (e.g., losses that might arise due to poor expected economic conditions). Similarly, companies do not record contingencies for more specific future risks such as allowances for repairs. The reason: These items do meet the definition of a liability because they do not arise from a past transaction but instead relate to future events.

Some companies take out insurance policies against the potential losses from fire, flood, storm, and accident. Other companies do not. The reasons: Some risks are not insurable, the insurance rates are prohibitive (e.g., earthquakes and riots), or they make a business decision to self-insure. Self-insurance is another item that is not recognized as a contingency.

Despite its name, self-insurance is not insurance, but risk assumption. Any company that assumes its own risks puts itself in the position of incurring expenses or losses as they occur. There is little theoretical justification for the establishment of a liability based on a hypothetical charge to insurance expense. This is "as if" accounting. The conditions for accrual stated in GAAP are not satisfied prior to the occurrence of the event. Until that time there is no diminution in the value of the property. And unlike an insurance company, which has contractual obligations to reimburse policyholders for losses, a company can have no such obligation to itself and, hence, no liability either before or after the occurrence of damage. [15][203]

The note shown in Illustration 13-12 from the annual report of Adolph Coors Company is typical of the self-insurance disclosure.

Exposure to risks of loss resulting from uninsured past injury to others, however, is an existing condition involving uncertainty about the amount and timing of losses that may develop. In such a case, a contingency exists. A company with a fleet of vehicles for example, would have to accrue uninsured losses resulting from injury to others or damage to the property of others that took place prior to the date of the financial statements (if the experience of the company or other information enables it to make a reasonable estimate of the liability). However, it should not establish a liability for expected future injury to others or damage to the property of others, even if it can reasonably estimate the amount of losses.

In practice, current liabilities are usually recorded and reported in financial statements at their full maturity value. Because of the short time periods involved, frequently less than one year, the difference between the present value of a current liability and the maturity value is usually not large. The profession accepts as immaterial any slight overstatement of liabilities that results from carrying current liabilities at maturity value. [16][204]

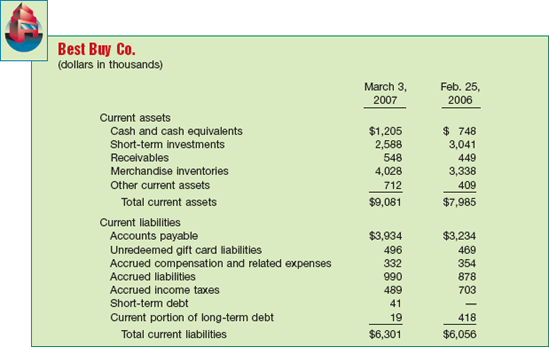

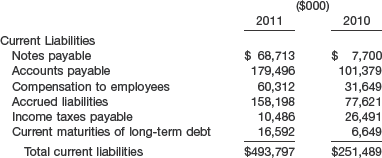

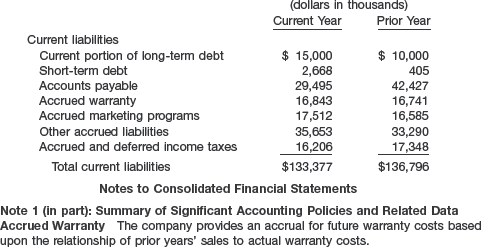

The current liabilities accounts are commonly presented as the first classification in the liabilities and stockholders' equity section of the balance sheet. Within the current liabilities section, companies may list the accounts in order of maturity, in descending order of amount, or in order of liquidation preference. Illustration 13-13 presents an excerpt of Best Buy Company's financial statements that is representative of the reports of large corporations.

Detail and supplemental information concerning current liabilities should be sufficient to meet the requirement of full disclosure. Companies should clearly identify secured liabilities, as well as indicate the related assets pledged as collateral. If the due date of any liability can be extended, a company should disclose the details. Companies should not offset current liabilities against assets that it will apply to their liquidation. Finally, current maturities of long-term debt are classified as current liabilities.

A major exception exists when a company will pay a currently maturing obligation from assets classified as long-term. For example, if a company will retire a bond payable using a bond sinking fund that is classified as a long-term asset, it should report the bonds payable in the long-term liabilities section. Presentation of this debt in the current liabilities section would distort the working capital position of the enterprise.

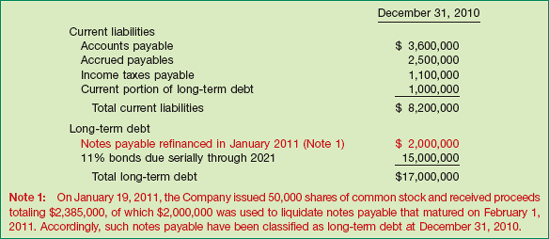

If a company excludes a short-term obligation from current liabilities because of refinancing, it should include the following in the note to the financial statements:

A general description of the financing agreement.

The terms of any new obligation incurred or to be incurred.

The terms of any equity security issued or to be issued.

When a company expects to refinance on a long-term basis by issuing equity securities, it is not appropriate to include the short-term obligation in stockholders' equity. At the date of the balance sheet, the obligation is a liability and not stockholders' equity. Illustration 13-14 (on page 664) shows the disclosure requirements for an actual refinancing situation.

A company records a loss contingency and a liability if the loss is both probable and estimable. But, if the loss is either probable or estimable but not both, and if there is at least a reasonable possibility that a company may have incurred a liability, it must disclose the following in the notes.

The nature of the contingency.

An estimate of the possible loss or range of loss or a statement that an estimate cannot be made.

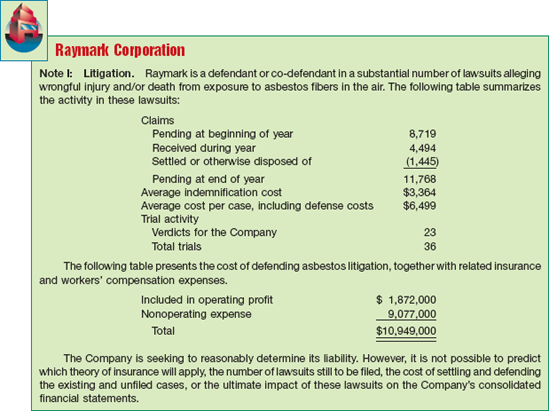

Illustration 13-15 presents an extensive litigation disclosure note from the financial statements of Raymark Corporation. The note indicates that Raymark charged actual losses to operations and that a further liability may exist, but that the company cannot currently estimate this liability.

Companies should disclose certain other contingent liabilities, even though the possibility of loss may be remote, as follows.

Guarantees of indebtedness of others.

Obligations of commercial banks under "stand-by letters of credit."

Guarantees to repurchase receivables (or any related property) that have been sold or assigned.

Disclosure should include the nature and amount of the guarantee and, if estimable, the amount that the company can recover from outside parties.[205] Cities Service Company disclosed its guarantees of others' indebtedness in the following note.

The distinction between current liabilities and long-term debt is important. It provides information about the liquidity of the company. Liquidity regarding a liability is the expected time to elapse before its payment. In other words, a liability soon to be paid is a current liability. A liquid company is better able to withstand a financial downturn. Also, it has a better chance of taking advantage of investment opportunities that develop.

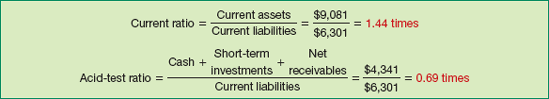

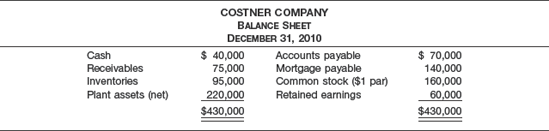

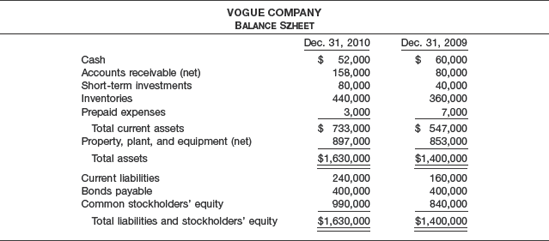

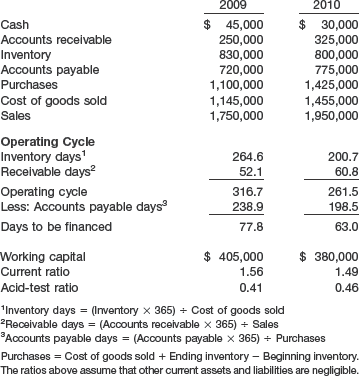

Analysts use certain basic ratios such as net cash flow provided by operating activities to current liabilities, and the turnover ratios for receivables and inventory, to assess liquidity. Two other ratios used to examine liquidity are the current ratio and the acid-test ratio.

The current ratio is the ratio of total current assets to total current liabilities. Illustration 13-17 shows its formula.

The ratio is frequently expressed as a coverage of so many times. Sometimes it is called the working capital ratio because working capital is the excess of current assets over current liabilities.

A satisfactory current ratio does not disclose that a portion of the current assets may be tied up in slow-moving inventories. With inventories, especially raw materials and work in process, there is a question of how long it will take to transform them into the finished product and what ultimately will be realized in the sale of the merchandise. Eliminating the inventories, along with any prepaid expenses, from the amount of current assets might provide better information for short-term creditors. Therefore, some analysts use the acid-test ratio in place of the current ratio.

Many analysts favor an acid-test or quick ratio that relates total current liabilities to cash, marketable securities, and receivables. Illustration 13-18 shows the formula for this ratio. As you can see, the acid-test ratio does not include inventories.

To illustrate the computation of these two ratios, we use the information for Best Buy Co. in Illustration 13-13 (on page 663). Illustration 13-19 shows the computation of the current and acid-test ratios for Best Buy.

From this information, it appears that Best Buy's current position is adequate. However, the acid-test ratio is well below 1. A comparison to another retailer, Circuit City, whose current ratio is 1.68 and whose acid-test ratio is 0.65, indicates that Best Buy is carrying less inventory than its industry counterparts.

There are several types of current liabilities, such as: (1) accounts payable, (2) notes payable, (3) current maturities of long-term debt, (4) dividends payable, (5) customer advances and deposits, (6) unearned revenues, (7) taxes payable, and (8) employee-related liabilities.

If it is probable that customers will make claims under warranties relating to goods or services that have been sold and it can reasonably estimate the costs involved, the company uses the accrual method. It charges warranty costs under the accrual basis to operating expense in the year of sale.

Premiums, coupon offers, and rebates are made to stimulate sales. Companies should charge their costs to expense in the period of the sale that benefits from the premium plan.

A company must recognize asset retirement obligations when it has an existing legal obligation related to the retirement of a long-lived asset and it can reasonably estimate the amount.

FASB Codification References

FASB ASC 480-10-05. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Certain Financial Instruments with Characteristics of Both Liabilities and Equity," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 150 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2003).]

FASB ASC 210-10-45-6. [Predecessor literature: Committee on Accounting Procedure, American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, "Accounting Research and Terminology Bulletins," Final Edition (New York: AICPA, 1961), p. 21.]

FASB ASC 470-10-05-7. [Predecessor literature: "Classification of Short-term Obligations Expected to Be Refinanced," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 6 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1975), par. 2.]

FASB ASC 470-10-45-11. [Predecessor literature: "Classification of Obligations That Are Callable by the Creditor," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 78 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1983).]

FASB ASC 470-10-45-14. [Predecessor literature: "Classification of Short-term Obligations Expected to Be Refinanced," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 6 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1975), pars. 10 and 11.]

FASB ASC 710-10-25-1. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Compensated Absences," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 43 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1980), par. 6.]

FASB ASC 712-10-05. [Predecessor literature: "Employers' Accounting for Postemployment Benefits," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 112 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, November 1992), par. 18.]

FASB ASC 450-10-05-4. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Contingencies," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 5 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1975), par. 1.]

FASB ASC 605-20-25. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Separately Extended Warranty and Product Maintenance Contracts," FASB Technical Bulletin No. 90-1 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1990).]

FASB ASC 605-20-25-3. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Separately Extended Warranty and Product Maintenance Contracts," FASB Technical Bulletin No. 90-1 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1990).]

FASB ASC 460-10-50-8. [Predecessor literature: "Guarantor's Accounting and Disclosure Requirements for Guarantees, Including Indirect Guarantees of Indebtedness of Others," FASB Interpretation No. 45 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2002).]

FASB ASC 410-20-05. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Asset Retirement Obligations," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 143 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2001).]

FASB ASC 450-20-30-1. [Predecessor literature: "Reasonable Estimation of the Amount of a Loss," FASB Interpretation No. 14 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1976), par. 3.]

FASB ASC 450-10-05. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Contingencies," FASB Statement No. 5 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1975).]

FASB ASC 450-20-55-5. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Contingencies," FASB Statement No. 5 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1975), par. 28.]

FASB ASC 835-30-15-3. [Predecessor literature: "Interest on Receivables and Payables," Opinions of the Accounting Principles Board No. 21 (New York: AICPA, 1971), par. 3.]

FASB ASC 460-10-50-8. [Predecessor literature: "Guarantor's Accounting and Disclosure Requirements for Guarantees, Including Indirect Guarantees of Indebtedness of Others," FASB Interpretation No. 45 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2002).]

Distinguish between a current liability and a long-term debt.

Assume that your friend Will Morris, who is a music major, asks you to define and discuss the nature of a liability. Assist him by preparing a definition of a liability and by explaining to him what you believe are the elements or factors inherent in the concept of a liability.

Why is the liabilities section of the balance sheet of primary significance to bankers?

How are current liabilities related by definition to current assets? How are current liabilities related to a company's operating cycle?

Leon Wight, a newly hired loan analyst, is examining the current liabilities of a corporate loan applicant. He observes that unearned revenues have declined in the current year compared to the prior year. Is this a positive indicator about the client's liquidity? Explain.

How is present value related to the concept of a liability?

What is the nature of a "discount" on notes payable?

How should a debt callable by the creditor be reported in the debtor's financial statements?

Under what conditions should a short-term obligation be excluded from current liabilities?

What evidence is necessary to demonstrate the ability to consummate the refinancing of short-term debt?

Discuss the accounting treatment or disclosure that should be accorded a declared but unpaid cash dividend; an accumulated but undeclared dividend on cumulative preferred stock; a stock dividend distributable.

How does unearned revenue arise? Why can it be classified properly as a current liability? Give several examples of business activities that result in unearned revenues.

What are compensated absences?

Under what conditions must an employer accrue a liability for the cost of compensated absences?

Under what conditions is an employer required to accrue a liability for sick pay? Under what conditions is an employer permitted but not required to accrue a liability for sick pay?

Faith Battle operates a health food store, and she has been the only employee. Her business is growing, and she is considering hiring some additional staff to help her in the store. Explain to her the various payroll deductions that she will have to account for, including their potential impact on her financial statements, if she hires additional staff.

Define (a) a contingency and (b) a contingent liability.

Under what conditions should a contingent liability be recorded?

Distinguish between a current liability and a contingent liability. Give two examples of each type.

How are the terms "probable," "reasonably possible," and "remote" related to contingent liabilities?

Contrast the cash-basis method and the accrual method of accounting for warranty costs.