LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

A conceptual framework is like a constitution: It is "a coherent system of interrelated objectives and fundamentals that can lead to consistent rules and that prescribes the nature, function, and limits of financial accounting and financial statements."[13] Many consider the FASB's real contribution to depend on the quality and utility of the conceptual framework.

Why do we need a conceptual framework? First, to be useful, rule-making should build on and relate to an established body of concepts and objectives. A soundly developed conceptual framework thus enables the FASB to issue more useful and consistent pronouncements over time. A coherent set of GAAP should result. The framework should increase financial statement users' understanding of and confidence in financial reporting. It should enhance comparability among companies' financial statements.

Second, the profession should be able to more quickly solve new and emerging practical problems by referring to an existing framework of basic theory. For example, Sunshine Mining (a silver-mining company) sold two issues of bonds. It can redeem them either with $1,000 in cash or with 50 ounces of silver, whichever is worth more at maturity. Both bond issues have a stated interest rate of 8.5 percent. At what amounts should Sunshine or the buyers of the bonds record them? What is the amount of the premium or discount on the bonds? And how should Sunshine amortize this amount, if the bond redemption payments are to be made in silver (the future value of which is unknown at the date of issuance?) Consider that Sunshine cannot know, at the date of issuance, the value of future silver bond redemption payments.

It is difficult, if not impossible, for the FASB to prescribe the proper accounting treatment quickly for situations like this. Practicing accountants, however, must resolve such problems on a daily basis. How? Through good judgment and with the help of a universally accepted conceptual framework, practitioners can quickly focus on an acceptable treatment.

The need for a conceptual framework is highlighted by recent accounting scandals such as those at Enron, Healthsouth, and other companies. To restore public confidence in the financial reporting process, Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 ("SOX"). One of its provisions requires the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to evaluate the usefulness of "principles-based" accounting rules relative to current GAAP (which many argue are too "rules-based").

Some have suggested a move toward principles-based rules. They believe that companies exploited the detailed provisions in rules-based pronouncements to manage accounting reports, rather than report the economic substance of transactions. For example, many of the off-balance-sheet arrangements of Enron avoided transparent reporting by barely achieving 3 percent outside equity ownership, a requirement in an obscure accounting rule interpretation. Enron's financial engineers were able to structure transactions to achieve a desired accounting treatment, even if that accounting treatment did not reflect the transaction's true nature.

In 2003 the SEC issued a report recommending that accounting rule-makers move away from a rules-based approach toward a more principles-based approach ("Study Pursuant to Section 108(d) ..."). If the profession adopts this approach, GAAP will be more conceptual in nature, and the financial reporting objective of each pronouncement will be more clearly stated. Top manage-ment's financial reporting responsibility will shift from demonstrating compliance with rules to demonstrating that a company has attained financial reporting objectives.

Source: "Study Pursuant to Section 108(d) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 on the Adoption by the United States Financial Reporting System of a Principles-Based Accounting System," www.sec.gov/news/studies/principlesbasedstand.htm.

Over the years, numerous organizations developed and published their own conceptual frameworks, but no single framework was universally accepted and relied on in practice. In 1976 the FASB began to develop a conceptual framework that would be a basis for setting accounting rules and for resolving financial reporting controversies. The FASB has since issued seven Statements of Financial Accounting Concepts that relate to financial reporting for business enterprises.[14] They are as follows.

SFAC No. 1, "Objectives of Financial Reporting by Business Enterprises," presents the goals and purposes of accounting.

SFAC No. 2, "Qualitative Characteristics of Accounting Information," examines the characteristics that make accounting information useful.

SFAC No. 3, "Elements of Financial Statements of Business Enterprises," provides definitions of items in financial statements, such as assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses.

SFAC No. 5, "Recognition and Measurement in Financial Statements of Business Enterprises," sets forth fundamental recognition and measurement criteria and guidance on what information should be formally incorporated into financial statements and when.

SFAC No. 6, "Elements of Financial Statements," replaces SFAC No. 3 and expands its scope to include not-for-profit organizations.

SFAC No. 7, "Using Cash Flow Information and Present Value in Accounting Measurements," provides a framework for using expected future cash flows and present values as a basis for measurement.

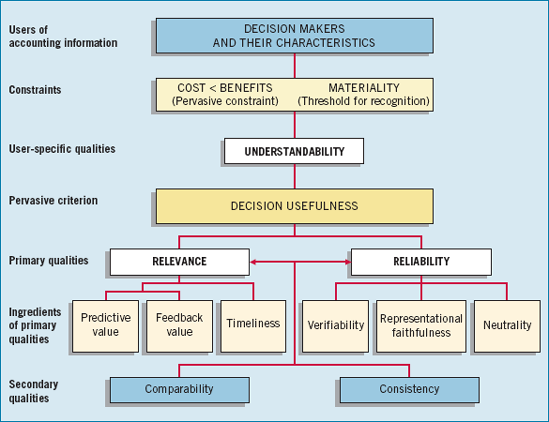

Illustration 2-1 (on page 34) provides an overview of the conceptual framework.[15] The first level lists the objectives—that is, the goals and purposes of accounting. Ideally, accounting standards developed according to a conceptual framework will result in more useful accounting reports.

The second level provides the qualitative characteristics that make accounting information useful and the elements of financial statements (assets, liabilities, and so on). The third level identifies the recognition and measurement concepts used in establishing and applying accounting standards. These concepts include assumptions, principles, and constraints that describe the present reporting environment. We examine these three levels of the conceptual framework next.

As we discussed in Chapter 1, the objectives of financial reporting are to provide information that is: (1) useful to those making investment and credit decisions, who have a reasonable understanding of business and economic activities; (2) helpful to present and potential investors, creditors, and other users in assessing the amounts, timing, and uncertainty of future cash flows; and (3) about economic resources, the claims to those resources, and the changes in them.

The objectives, therefore, broadly concern information that is useful to investor and creditor decisions. That concern narrows to the investors' and creditors' interest in receiving cash from their investments in, or loans to, business enterprises. Finally, the objectives focus on the financial statements, which provide information useful in assessing future cash flows. This approach is referred to as decision usefulness.

To provide information to decision makers, companies prepare general-purpose financial statements. These statements provide the most useful information possible at the least cost. However, users do need reasonable knowledge of business and financial accounting matters to understand the information contained in financial statements. This point is important. It means that financial statement preparers assume a level of competence on the part of users. This assumption impacts the way and the extent to which companies report information.

The objectives (first level) focus on the goals and purposes of accounting. Later, we will discuss the ways these goals and purposes are implemented (third level). What, then, is the purpose of the second level? The second level provides conceptual building blocks that explain the qualitative characteristics of accounting information and define the elements of financial statements. That is, the second level forms a bridge between the why of accounting (the objectives) and the how of accounting (recognition and measurement).

Should companies like Walt Disney or Kellogg's provide information in their financial statements on how much it costs them to acquire their assets (historical cost basis) or how much the assets are currently worth (fair value basis)? Should PepsiCo combine and show as one company the four main segments of its business, or should it report PepsiCo Beverages, Frito Lay, Quaker Foods, and PepsiCo International as four separate segments?

How does a company choose an acceptable accounting method, the amount and types of information to disclose, and the format in which to present it? The answer: By determining which alternative provides the most useful information for decision-making purposes (decision usefulness). The FASB identified the qualitative characteristics of accounting information that distinguish better (more useful) information from inferior (less useful) information for decision-making purposes.[16] In addition, the FASB identified certain constraints (cost-benefit and materiality) as part of the conceptual framework (discussed later in the chapter). As Illustration 2-2 shows, the characteristics may be viewed as a hierarchy.

Decision makers vary widely in the types of decisions they make, how they make decisions, the information they already possess or can obtain from other sources, and their ability to process the information. For information to be useful, there must be a connection (linkage) between these users and the decisions they make. This link, understandability, is the quality of information that lets reasonably informed users see its significance.

For example, assume that IBM Corp. issues a three-months' report that shows interim earnings have declined significantly. This interim report provides relevant and reliable information for decision-making purposes. Now say that some users, upon reading the report, decide to sell their stock. Other users, however, do not understand the report's content and significance. They are surprised when IBM declares a smaller year-end dividend and the value of the stock declines. Thus, although IBM presented highly relevant and reliable information, it was useless to those who did not understand it.

Relevance and reliability are the two primary qualities that make accounting information useful for decision making. As stated in FASB Concepts Statement No. 2, "the qualities that distinguish 'better' (more useful) information from 'inferior' (less useful) information are primarily the qualities of relevance and reliability, with some other characteristics that those qualities imply."[17]

Relevance. To be relevant, accounting information must be capable of making a difference in a decision.[18] Information with no bearing on a decision is irrelevant. Relevant information helps users predict the ultimate outcome of past, present, and future events. That is, it has predictive value. Relevant information also helps users confirm or correct prior expectations; it has feedback value. For example, when UPS (United Parcel Service) issues an interim report, the information in it is relevant because it provides both a basis for forecasting annual earnings and feedback on past performance.

Finally, relevant information is available to decision makers before it loses its capacity to influence their decisions. It has timeliness. If UPS waited to report its interim results until six months after the end of the period, the information would be much less useful for decision-making purposes. For information to be relevant, it needs predictive or feedback value, presented on a timely basis.

Reliability. Accounting information is reliable to the extent that it is verifiable, is a faithful representation, and is reasonably free of error and bias. Reliability is a necessity, because most users have neither the time nor the expertise to evaluate the factual content of the information.

Verifiability occurs when independent measurers, using the same methods, obtain similar results. For example, would several independent auditors reach the same conclusion about a set of financial statements? If not, then the statements are not verifiable. Auditors could not render an opinion on such statements.

Representational faithfulness means that the numbers and descriptions match what really existed or happened. If General Motors' income statement reports sales of $225 billion when it had sales of $193.5 billion, then the statement fails to faithfully represent the proper sales amount.

Neutrality means that a company cannot select information to favor one set of interested parties over another. Unbiased information must be the overriding consideration. For example, in the notes to financial statements, tobacco companies such as R. J. Reynolds should not suppress information about the numerous lawsuits that have been filed because of tobacco-related health concerns—even though such disclosure is damaging to the company.

Neutrality in rule-making has come under increasing attack. Some argue that the FASB should not issue pronouncements that cause undesirable economic effects on an industry or company. We disagree. GAAP must be free from bias, or we will no longer have credible financial statements. Without credible financial statements, individuals will no longer use this information. An analogy demonstrates the point: In the United States, many individuals bet on boxing matches because such contests are assumed not to be fixed. But nobody bets on wrestling matches. Why? Because the public assumes that wrestling matches are rigged. If financial information is biased (rigged), the public will lose confidence and no longer use it.

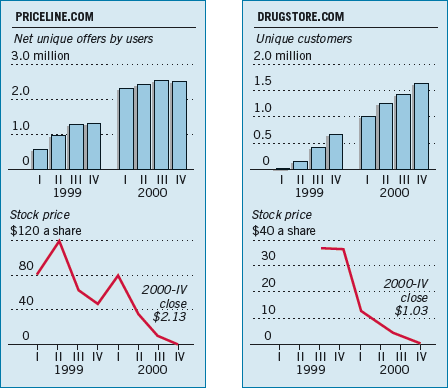

The growth of new-economy business on the Internet has led to the development of new measures of performance. When Priceline.com splashed on the dot-com scene, it touted steady growth in a measure called "unique offers by users" to explain its heady stock price. To draw investors to its stock, Drugstore.com focused on the number of "unique customers" at its website. After all, new businesses call for new performance measures, right?

Not necessarily. In fact, these indicators failed to show any consistent relationship between profits and website visits. Eventually, as the graphs below show, the profits never materialized, stock prices fell, and the dot-com bubble burst.

The lesson here: Although the new economy may require some new measures, investors need to be careful not to forget the reliable traditional ones.

Source: Story and graphs adapted from Gretchen Morgenson, "How Did They Value Stocks? Count the Absurd Ways," New York Times (March 18, 2001), section 3, p. 1.

Information about a company is more useful if decision makers can compare it with similar information about another company and with similar information about the same company at other points in time. The first of these qualities is comparability, and the second is consistency.

Comparability. Information that is measured and reported in a similar manner for different companies is considered comparable. Comparability enables users to identify the real similarities and differences in economic events between companies.

For example, historically the accounting for pensions in the United States differs from that in Japan. U.S. companies record pension cost as incurred. In Japan, companies generally recorded little or no charge to income for these costs. As a result, it is difficult to compare and evaluate the financial results of General Motors or Ford to Japanese competitors. Also, resource allocation decisions involve evaluating alternatives. A valid evaluation can be made only if comparable information is available.

Consistency. When a company applies the same accounting treatment to similar events, from period to period, the company shows consistent use of accounting standards. The idea of consistency does not mean, however, that companies cannot switch from one accounting method to another. A company can change methods, but it must first demonstrate that the newly adopted method is preferable to the old. If approved, the company must then disclose the nature and effect of the accounting change, as well as the justification for it, in the financial statements for the period in which it made the change.[19] When a change in accounting principles occurs, the auditor refers to it in an explanatory paragraph of the audit report. This paragraph identifies the nature of the change and refers the reader to the note in the financial statements that discusses the change in detail.[20]

An important aspect of developing any theoretical structure is the body of basic elements or definitions to be included in it. Accounting uses many terms with distinctive and specific meanings. These terms constitute the language of business or the jargon of accounting.

One such term is asset. Is it merely something we own? Or is an asset something we have the right to use, as in the case of leased equipment? Or is it anything of value used by a company to generate revenues—in which case, should we also consider the managers of a company as an asset?

As this example and the lottery ticket example in the opening story illustrate, it seems necessary, therefore, to develop basic definitions for the elements of financial statements. Concepts Statement No. 6 defines the ten interrelated elements that most directly relate to measuring the performance and financial status of a business enterprise. We list them on the next page for review and information purposes; you need not memorize these definitions at this point. We will explain and examine each of these elements in more detail in subsequent chapters.

The FASB classifies the elements into two distinct groups. The first group of three elements—assets, liabilities, and equity—describes amounts of resources and claims to resources at a moment in time. The other seven elements describe transactions, events, and circumstances that affect a company during a period of time. The first class, affected by elements of the second class, provides at any time the cumulative result of all changes. This interaction is referred to as "articulation." That is, key figures in one financial statement correspond to balances in another.

The third level of the framework consists of concepts that implement the basic objectives of level one. These concepts explain how companies should recognize, measure, and report financial elements and events. The FASB sets forth most of these in its Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 5, "Recognition and Measurement in Financial Statements of Business Enterprises." According to SFAC No. 5, to be recognized, an item (event or transaction) must meet the definition of an "element of financial statements" as defined in SFAC No. 6 and must be measurable. Most aspects of current practice follow these recognition and measurement concepts.

The accounting profession continues to use the concepts in SFAC No. 5 as operational guidelines. Here, we identify the concepts as basic assumptions, principles, and constraints. Not everyone uses this classification system, so focus your attention more on understanding the concepts than on how we classify and organize them. These concepts serve as guidelines in responding to controversial financial reporting issues.

Four basic assumptions underlie the financial accounting structure: (1) economic entity, (2) going concern, (3) monetary unit, and (4) periodicity. We'll look at each in turn.

The economic entity assumption means that economic activity can be identified with a particular unit of accountability. In other words, a company keeps its activity separate and distinct from its owners and any other business unit. At the most basic level, the economic entity assumption dictates that Panera Bread Company record the company's financial activities separate from those of its owners and managers. Equally important, financial statement users need to be able to distinguish the activities and elements of different companies, such as General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler. If users could not distinguish the activities of different companies, how would they know which company financially outperformed the other?

The entity concept does not apply solely to the segregation of activities among competing companies, such as Best Buy and Circuit City. An individual, department, division, or an entire industry could be considered a separate entity if we choose to define it in this manner. Thus, the entity concept does not necessarily refer to a legal entity. A parent and its subsidiaries are separate legal entities, but merging their activities for accounting and reporting purposes does not violate the economic entity assumption.[22]

The importance of the entity assumption is illustrated by scandals involving W. R. Grace and, more recently, Adelphia. In both cases, senior company employees entered into transactions that blurred the line between the employee's financial interests and those of the company. At Adelphia, among many other self-dealings, the company guaranteed over $2 billion of loans to the founding family. W. R. Grace used company funds to pay for an apartment and chef for the company chairman. As a result of these transactions, these insiders benefitted at the expense of shareholders. Additionally, the financial statements failed to disclose the transactions. Such disclosure would have allowed shareholders to sort out the impact of the employee transactions on company results.

Most accounting methods rely on the going concern assumption—that the company will have a long life. Despite numerous business failures, most companies have a fairly high continuance rate. As a rule, we expect companies to last long enough to fulfill their objectives and commitments.

This assumption has significant implications. The historical cost principle would be of limited usefulness if we assume eventual liquidation. Under a liquidation approach, for example, a company would better state asset values at net realizable value (sales price less costs of disposal) than at acquisition cost. Depreciation and amortization policies are justifiable and appropriate only if we assume some permanence to the company. If a company adopts the liquidation approach, the current/non-current classification of assets and liabilities loses much of its significance. Labeling anything a fixed or long-term asset would be difficult to justify. Indeed, listing liabilities on the basis of priority in liquidation would be more reasonable.

The going concern assumption applies in most business situations. Only where liquidation appears imminent is the assumption inapplicable. In these cases a total revaluation of assets and liabilities can provide information that closely approximates the company's net realizable value. You will learn more about accounting problems related to a company in liquidation in advanced accounting courses.

The monetary unit assumption means that money is the common denominator of economic activity and provides an appropriate basis for accounting measurement and analysis. That is, the monetary unit is the most effective means of expressing to interested parties changes in capital and exchanges of goods and services. The monetary unit is relevant, simple, universally available, understandable, and useful. Application of this assumption depends on the even more basic assumption that quantitative data are useful in communicating economic information and in making rational economic decisions.

In the United States, accounting ignores price-level changes (inflation and deflation) and assumes that the unit of measure—the dollar—remains reasonably stable. We therefore use the monetary unit assumption to justify adding 1980 dollars to 2010 dollars without any adjustment. The FASB in SFAC No. 5 indicated that it expects the dollar, unadjusted for inflation or deflation, to continue to be used to measure items recognized in financial statements. Only if circumstances change dramatically (such as if the United States experiences high inflation similar to that in many South American countries) will the FASB again consider "inflation accounting."

To measure the results of a company's activity accurately, we would need to wait until it liquidates. Decision makers, however, cannot wait that long for such information. Users need to know a company's performance and economic status on a timely basis so that they can evaluate and compare firms, and take appropriate actions. Therefore, companies must report information periodically.

The periodicity (or time period) assumption implies that a company can divide its economic activities into artificial time periods. These time periods vary, but the most common are monthly, quarterly, and yearly.

The shorter the time period, the more difficult it is to determine the proper net income for the period. A month's results usually prove less reliable than a quarter's results, and a quarter's results are likely to be less reliable than a year's results. Investors desire and demand that a company quickly process and disseminate information. Yet the quicker a company releases the information, the more likely the information will include errors. This phenomenon provides an interesting example of the trade-off between relevance and reliability in preparing financial data.

The problem of defining the time period becomes more serious as product cycles shorten and products become obsolete more quickly. Many believe that, given technology advances, companies need to provide more online, real-time financial information to ensure the availability of relevant information.

We generally use four basic principles of accounting to record and report transactions: (1) measurement, (2) revenue recognition, (3) expense recognition, and (4) full disclosure. We look at each in turn.

We presently have a "mixed-attribute" system that permits the use of various measurement bases. The most commonly used measurements are based on historical cost and fair value. Here, we discuss each.

Historical Cost. GAAP requires that companies account for and report many assets and liabilities on the basis of acquisition price. This is often referred to as the historical cost principle. Historical cost has an important advantage over other valuations: It is generally thought to be reliable.

To illustrate this advantage, consider the problems if companies select current selling price instead. Companies might have difficulty establishing a value for unsold items. Every member of the accounting department might value the assets differently. Further, how often would it be necessary to establish sales value? All companies close their accounts at least annually. But some compute their net income every month. Those companies would have to place a sales value on every asset each time they wished to determine income. Critics raise similar objections against current cost (replacement cost, present value of future cash flows) and any other basis of valuation except historical cost.

What about liabilities? Do companies account for them on a cost basis? Yes, they do. Companies issue liabilities, such as bonds, notes, and accounts payable, in exchange for assets (or services), for an agreed-upon price. This price, established by the exchange transaction, is the "cost" of the liability. A company uses this amount to record the liability in the accounts and report it in financial statements. Thus, many users prefer historical cost because it provides them with a verifiable benchmark for measuring historical trends.

Fair Value. Fair value is defined as "the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date." Fair value is therefore a market-based measure. [1] Recently GAAP has increasingly called for use of fair value measurements in the financial statements. This is often referred to as the fair value principle. Fair value information may be more useful than historical cost for certain types of assets and liabilities and in certain industries. For example, companies report many financial instruments, including derivatives, at fair value. Certain industries, such as brokerage houses and mutual funds, prepare their basic financial statements on a fair value basis.

At initial acquisition, historical cost equals fair value. In subsequent periods, as market and economic conditions change, historical cost and fair value often diverge. Thus, fair value measures or estimates often provide more relevant information about the expected future cash flows related to the asset or liability. For example, when long-lived assets decline in value, a fair value measure determines any impairment loss. The FASB believes that fair value information is more relevant to users than historical cost. Fair value measurement, it is argued, provides better insight into the value of a company's asset and liabilities (its financial position) and a better basis for assessing future cash flow prospects.

Recently the Board has taken the additional step of giving companies the option to use fair value (referred to as the fair value option) as the basis for measurement of financial assets and financial liabilities. [2] The Board considers fair value more relevant than historical cost because it reflects the current cash equivalent value of financial instruments. As a result companies now have the option to record fair value in their accounts for most financial instruments, including such items as receivables, investments, and debt securities.

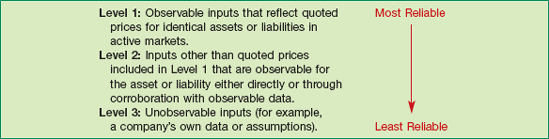

Use of fair value in financial reporting is increasing. However, measurement based on fair value introduces increased subjectivity into accounting reports, when fair value information is not readily available. To increase consistency and comparability in fair value measures, the FASB established a fair value hierarchy that provides insight into the priority of valuation techniques to use to determine fair value. As shown in Illustration 2-3, the fair value hierarchy is divided into three broad levels.

As Illustration 2-3 indicates, Level 1 is the most reliable because it is based on quoted prices, like a closing stock price in the Wall Street Journal. Level 2 is the next most reliable and would rely on evaluating similar assets or liabilities in active markets. At the least-reliable level, Level 3, much judgment is needed based on the best information available, to arrive at a relevant and reliable fair value measurement.[23]

It is easy to arrive at fair values when markets are liquid with many traders, but fair value answers are not readily available in other situations. For example, how do you value the mortgage assets of subprime lenders, like Countrywide and New Century, given that the market for these securities has essentially disappeared? A great deal of expertise and sound judgment will be needed to arrive at appropriate answers. GAAP also provides guidance on estimating fair values when market-related data is not available. In general, these valuation issues relate to Level 3 fair value measurements. These measurements may be developed using expected cash flow and present value techniques, as described in Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 7, "Using Cash Flow Information and Present Value in Accounting," discussed in Chapter 6.

As indicated above, we presently have a "mixed-attribute" system that permits the use of historical cost and fair value. Although the historical cost principle continues to be an important basis for valuation, recording and reporting of fair value information is increasing. The recent measurement and disclosure guidance should increase consistency and comparability when fair value measurements are used in the financial statements and related notes.

A crucial question for many companies is when to recognize revenue. Revenue recognition generally occurs (1) when realized or realizable and (2) when earned. This approach has often been referred to as the revenue recognition principle.

A company realizes revenues when it exchanges products (goods or services), merchandise, or other assets for cash or claims to cash. Revenues are realizable when assets received or held are readily convertible into cash or claims to cash. Assets are readily convertible when they are salable or interchangeable in an active market at readily determinable prices without significant additional cost.

In addition to the first test (realized or realizable), a company delays recognition of revenues until earned. Revenues are considered earned when the company substantially accomplishes what it must do to be entitled to the benefits represented by the revenues.[24] Generally, an objective test, such as a sale, indicates the point at which a company recognizes revenue. The sale provides an objective and verifiable measure of revenue—the sales price. Any basis for revenue recognition short of actual sale opens the door to wide variations in practice. Recognition at the time of sale provides a uniform and reasonable test.

However, as Illustration 2-4 shows, exceptions to the rule exist. We discuss these exceptions in the following sections.

During Production. A company can recognize revenue before it completes the job in certain long-term construction contracts. In this method, a company recognizes revenue periodically, based on the percentage of the job it has completed. Although technically a transfer of ownership has not occurred, the earning process is considered substantially completed at various stages of construction. If it is not possible to obtain dependable estimates of cost and progress, then a company delays revenue recognition until it completes the job.

At End of Production. At times, a company may recognize revenue after completion of the production cycle but before the sale takes place. This occurs if products or other assets are salable in an active market at readily determinable prices without significant additional cost. An example is the mining of certain minerals. Once a company mines the mineral, a ready market at a quoted price exists. The same holds true for some agricultural products.

Upon Receipt of Cash. Receipt of cash is another basis for revenue recognition. Companies use the cash-basis approach only when collection is uncertain at the time of sale.

One form of the cash basis is the installment-sales method. Here, a company requires payment in periodic installments over a long period of time. Its most common use is in retail, such as for farm and home equipment and furnishings. Companies frequently justify the installment-sales method based on the high risk of not collecting an account receivable. In some instances, this reasoning may be valid. Generally, though, if a sale has been completed, the company should recognize the sale; if bad debts are expected, the company should record them as separate estimates.

To summarize, a company records revenue in the period when realized or realizable and when earned. Normally, this is the date of sale. But circumstances may dictate application of the percentage-of-completion approach, the end-of-production approach, or the receipt-of-cash approach.

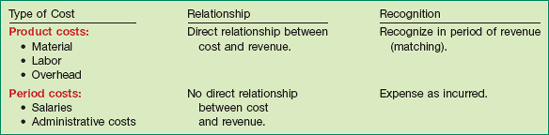

As indicated in the discussion of financial statement elements, expenses are defined as outflows or other "using up" of assets or incurring of liabilities (or a combination of both) during a period as a result of delivering or producing goods and/or rendering services. It follows then that recognition of expenses is related to net changes in assets and earning revenues. In practice, the approach for recognizing expenses is, "Let the expense follow the revenues." This approach is the expense recognition principle.

To illustrate, companies recognize expenses not when they pay wages or make a product, but when the work (service) or the product actually contributes to revenue. Thus, companies tie expense recognition to revenue recognition. That is, by matching efforts (expenses) with accomplishment (revenues), the expense recognition principle is implemented in accordance with the definition of expense (outflows or other using up of assets or incurring of liabilities).[25]

Some costs, however, are difficult to associate with revenue. As a result, some other approach must be developed. Often, companies use a "rational and systematic" allocation policy that will approximate the expense recognition principle. This type of expense recognition involves assumptions about the benefits that a company receives as well as the cost associated with those benefits. For example, a company like Intel or Motorola allocates the cost of a long-lived asset over all of the accounting periods during which it uses the asset because the asset contributes to the generation of revenue throughout its useful life.

Companies charge some costs to the current period as expenses (or losses) simply because they cannot determine a connection with revenue. Examples of these types of costs are officers' salaries and other administrative expenses.

Costs are generally classified into two groups: product costs and period costs. Product costs, such as material, labor, and overhead, attach to the product. Companies carry these costs into future periods if they recognize the revenue from the product in subsequent periods. Period costs, such as officers' salaries and other administrative expenses, attach to the period. Companies charge off such costs in the immediate period, even though benefits associated with these costs may occur in the future. Why? Because companies cannot determine a direct relationship between period costs and revenue. Illustration 2-5 summarizes these expense recognition procedures.

In deciding what information to report, companies follow the general practice of providing information that is of sufficient importance to influence the judgment and decisions of an informed user. Often referred to as the full disclosure principle, it recognizes that the nature and amount of information included in financial reports reflects a series of judgmental trade-offs. These trade-offs strive for (1) sufficient detail to disclose matters that make a difference to users, yet (2) sufficient condensation to make the information understandable, keeping in mind costs of preparing and using it.

Users find information about financial position, income, cash flows, and investments in one of three places: (1) within the main body of financial statements, (2) in the notes to those statements, or (3) as supplementary information.

As discussed in Chapter 1, the financial statements are the balance sheet, income statement, statement of cash flows, and statement of owners' equity. They are a structured means of communicating financial information. To be recognized in the main body of financial statements, an item should meet the definition of a basic element, be measurable with sufficient certainty, and be relevant and reliable.[26]

Disclosure is not a substitute for proper accounting. As a former chief accountant of the SEC noted, "Good disclosure does not cure bad accounting any more than an adjective or adverb can be used without, or in place of, a noun or verb." Thus, for example, cash-basis accounting for cost of goods sold is misleading, even if a company discloses accrual-basis amounts in the notes to the financial statements.

The notes to financial statements generally amplify or explain the items presented in the main body of the statements. If the main body of the financial statements gives an incomplete picture of the performance and position of the company, the notes should provide the additional information needed. Information in the notes does not have to be quantifiable, nor does it need to qualify as an element. Notes can be partially or totally narrative. Examples of notes include descriptions of the accounting policies and methods used in measuring the elements reported in the statements, explanations of uncertainties and contingencies, and statistics and details too voluminous for inclusion in the statements. The notes can be essential to understanding the company's performance and position.

Supplementary information may include details or amounts that present a different perspective from that adopted in the financial statements. It may be quantifiable information that is high in relevance but low in reliability. For example, oil and gas companies typically provide information on proven reserves as well as the related discounted cash flows.

Supplementary information may also include management's explanation of the financial information and its discussion of the significance of that information. For example, many business combinations have produced financing arrangements that demand new accounting and reporting practices and principles. In each of these situations, the same problem must be faced: making sure the company presents enough information to ensure that the reasonably prudent investor will not be misled.

We discuss the content, arrangement, and display of financial statements, along with other facets of full disclosure, in Chapters 4, 5, and 24.

In providing information with the qualitative characteristics that make it useful, companies must consider two overriding factors that limit (constrain) the reporting. These constraints are: (1) the cost-benefit relationship and (2) materiality. We also review two other less-dominant yet important constraints that are part of the reporting environment: industry practices and conservatism.

Beyond touting nonfinancial measures to investors (see box on page 37), many companies increasingly promote the performance of their companies through the reporting of various "pro-forma" earnings measures. A recent survey of newswire reports found 36 instances of the reporting of proforma measures in just a three-day period.

Pro-forma measures are standard measures (such as earnings) that companies adjust, usually for one-time or nonrecurring items. For example, companies usually adjust earnings for the effects of an extraordinary item. Such adjustments make the numbers more comparable to numbers reported in periods without the unusual item.

However, rather than increasing comparability, it appears that some companies use pro-forma reporting to accentuate the positive in their results. Examples include Yahoo Inc. and Cisco, which define pro-forma income after adding back payroll tax expense. Level 8 Systems transformed an operating loss into a pro-forma profit by adding back expenses for depreciation and amortization of intangible assets.

Lynn Turner, former Chief Accountant at the SEC, calls such earnings measures EBS—"Everything but Bad Stuff." To provide investors a more complete picture of company profitability, not the story preferred by management, the SEC issued Regulation G (REG G). REG G requires companies to reconcile non-GAAP financial measures to GAAP, thereby giving investors a roadmap to analyze adjustments companies make to their GAAP numbers to arrive at pro-forma results.

Sources: Adapted from Gretchen Morgenson, "How Did They Value Stocks? Count the Absurd Ways," New York Times (March 18, 2001), section 3, p. 1; and Gretchen Morgenson, "Expert Advice: Focus on Profit," New York Times (March 18, 2001), section 3, p. 14. See also SEC Regulation G, "Conditions for Use of Non-GAAP Financial Measures, "Release No. 33–8176 (March 28, 2003).

Too often, users assume that information is free. But preparers and providers of accounting information know that it is not. Therefore, companies must consider the cost-benefit relationship: They must weigh the costs of providing the information against the benefits that can be derived from using it. Rule-making bodies and governmental agencies use cost-benefit analysis before making final their informational requirements. In order to justify requiring a particular measurement or disclosure, the benefits perceived to be derived from it must exceed the costs perceived to be associated with it.

A corporate executive made the following remark to the FASB about a proposed rule: "In all my years in the financial arena, I have never seen such an absolutely ridiculous proposal. ... To dignify these 'actuarial' estimates by recording them as assets and liabilities would be virtually unthinkable except for the fact that the FASB has done equally stupid things in the past. ... For God's sake, use common sense just this once."[27] Although extreme, this remark indicates the frustration expressed by members of the business community about rule-making, and whether the benefits of a given pronouncement exceed the costs.

The difficulty in cost-benefit analysis is that the costs and especially the benefits are not always evident or measurable. The costs are of several kinds: costs of collecting and processing, of disseminating, of auditing, of potential litigation, of disclosure to competitors, and of analysis and interpretation. Benefits to preparers may include greater management control and access to capital at a lower cost. Users may receive better information for allocation of resources, tax assessment, and rate regulation. As noted earlier, benefits are generally more difficult to quantify than are costs.

The recent implementation of the provisions of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 illustrates the challenges in assessing costs and benefits of standards. One study estimated the increased costs of complying with the new internal-control standards related to the financial reporting process to be an average of $7.8 million per company. However, the study concluded that "... quantifying the benefits of improved more reliable financial reporting is not fully possible."[28]

Despite the difficulty in assessing the costs and benefits of its rules, the FASB attempts to determine that each proposed pronouncement will fill a significant need and that the costs imposed to meet the rule are justified in relation to overall benefits of the resulting information. In addition, the Board seeks input on costs and benefits as part of its due process.[29]

The materiality constraint concerns an item's impact on a company's overall financial operations. An item is material if its inclusion or omission would influence or change the judgment of a reasonable person.[30] It is immaterial, and therefore irrelevant, if it would have no impact on a decision maker. In short, it must make a difference or a company need not disclose it.

The point involved here is of relative size and importance. If the amount involved is significant when compared with the other revenues and expenses, assets and liabilities, or net income of the company, sound and acceptable standards should be followed in reporting it. If the amount is so small that it is unimportant when compared with other items, applying a particular standard may be considered of less importance.

It is difficult to provide firm guidelines in judging when a given item is or is not material. Materiality varies both with relative amount and with relative importance. For example, the two sets of numbers in Illustration 2-6 indicate relative size.

During the period in question, the revenues and expenses, and therefore the net incomes of Company A and Company B, are proportional. Each reported an unusual gain. In looking at the abbreviated income figures for Company A, it appears insignificant whether the amount of the unusual gain is set out separately or merged with the regular operating income. The gain is only 2 percent of the net income. If merged, it would not seriously distort the net income figure. Company B has had an unusual gain of only $5,000. However, it is relatively much more significant than the larger gain realized by A. For Company B, an item of $5,000 amounts to 50 percent of its income from operations. Obviously, the inclusion of such an item in ordinary operating income would affect the amount of that income materially. Thus we see the importance of the relative size of an item in determining its materiality.

Companies and their auditors generally adopt the rule of thumb that anything under 5 percent of net income is considered immaterial. However, the SEC indicates that a company may use this percentage for an initial assessment of materiality, but it must also consider other factors.[31] For example, companies can no longer fail to record items in order to meet consensus analysts' earnings numbers, preserve a positive earnings trend, convert a loss to a profit or vice versa, increase management compensation, or hide an illegal transaction like a bribe. In other words, companies must consider both quantitative and qualitative factors in determining whether an item is material.

The SEC also indicated that in determining materiality, companies must consider each misstatement separately and the aggregate effect of all misstatements. For example, at one time, General Dynamics disclosed that its Resources Group improved its earnings by $5.8 million. At the same time, it disclosed that one of its other subsidiaries had taken write-offs of $6.7 million. Although both numbers exceeded the $2.5 million that General Dynamics as a whole earned for the year, the company disclosed neither as unusual because it considered the net effect on earnings as immaterial. This practice is prohibited because each item must be considered separately. In addition, even though an individual item may be immaterial, it may be considered material when added to other immaterial items. Companies must disclose such items.

Materiality factors in a great many internal accounting decisions, too. Examples of such judgments that companies must make include: the amount of classification required in a subsidiary expense ledger, the degree of accuracy required in prorating expenses among the departments of a company, and the extent to which adjustments should be made for accrued and deferred items. Only by the exercise of good judgment and professional expertise can reasonable and appropriate answers be found, which is the materiality constraint sensibly applied.

The first line of defense for many companies caught "cooking the books" had been to argue that a questionable accounting item is immaterial. That defense did not work so well in the wake of accounting meltdowns at Enron and Global Crossing and the tougher rules on materiality issued by the SEC (SAB 99).

For example, the SEC alleged in a case against Sunbeam that the company's many immaterial adjustments added up to a material misstatement that misled investors about the company's financial position. More recently, the SEC called for a number of companies, such as Jack in the Box, McDonald's, and AIG, to restate prior financial statements for the effects of incorrect accounting. In some cases, the restatements did not meet traditional materiality thresholds. Don Nicholaisen, then SEC Chief Accountant, observed that whether the amount is material or not-material, some transactions appear to be "flat out intended to mislead investors." In essence he is saying that any wrong accounting for a transaction can represent important information to the users of financial statements.

Responding to new concerns about materiality, blue-chip companies such as IBM and General Electric are providing expanded disclosures of transactions that used to fall below the materiality radar. As a result, some good may yet come from the recent accounting failures.

Source: Adapted from K. Brown and J. Weil, "A Lot More Information Is 'Material' After Enron," Wall Street Journal Online Edition (February 22, 2002); S. D. Jones and R. Gibson, "Restaurants Serve Up Restatements," Wall Street Journal (January 26, 2005), p. C3; and R. McTauge, "Nicholaisen Says Restatement Needed When Deal Lacks Business Purpose," Securities Regulation & Law Reporter (May 9, 2005).

Another practical consideration is industry practices. The peculiar nature of some industries and business concerns sometimes requires departure from basic theory. For example, public-utility companies report noncurrent assets first on the balance sheet to highlight the industry's capital-intensive nature. Agricultural companies often report crops at fair value because it is costly to develop accurate cost figures on individual crops.

Such variations from basic theory are infrequent, yet they do exist. Whenever we find what appears to be a violation of basic accounting theory, we should determine whether some peculiarity of the industry explains the violation before we criticize the procedures followed.

Few conventions in accounting are as misunderstood as the constraint of conservatism. Conservatism means when in doubt, choose the solution that will be least likely to overstate assets and income. Note that the conservatism convention does not urge that net assets or net income be understated. Unfortunately, some interpret conservatism to mean just that.

All that conservatism does, properly applied, is provide a reasonable guide in difficult situations: Refrain from overstatement of net income and net assets. Examples of conservatism in accounting are the use of the lower-of-cost-or-market approach in valuing inventories, and the rule that companies recognize accrued net losses on firm purchase commitments for goods for inventory. When in doubt, it is better to understate than overstate net income and net assets. Of course, if no doubt exists, there is no need to apply this constraint.

Illustration 2-7 presents the conceptual framework discussed in this chapter. It is similar to Illustration 2-1, except that it provides additional information for each level. We cannot overemphasize the usefulness of this conceptual framework in helping to understand many of the problem areas that we examine in later chapters.

In 2005, the IASB and the FASB agreed to work on a joint project to develop a common conceptual framework. This framework is based on the existing conceptual frameworks underlying U.S. GAAP and iGAAP. The objective of this joint project is to develop a conceptual framework that leads to developing standards that are principle-based and internally consistent and that leads to the most useful financial reporting.

The existing conceptual frameworks underlying U.S. GAAP and iGAAP are very similar. That is, they are organized in a similar manner (objectives, elements, qualitative characteristics, etc.). There is no real need to change many aspects of the existing frameworks, other than to converge different ways of discussing essentially the same concepts.

The converged framework should be a single document, unlike the two conceptual frameworks that presently exist; it is unlikely that the basic structure related to the concepts will change.

The IASB framework makes two assumptions. One assumption is that financial statements are prepared on an accrual basis; the other is that the reporting entity is a going concern. The FASB framework discusses accrual accounting extensively but does not identify it as an assumption, and it only briefly discusses the going concern concept.

There is some agreement that the role of financial reporting is to assist users in decision making. However, others note that another objective is to provide information on management's performance, often referred to as stewardship. It is likely that there will be much debate about the role of stewardship in the conceptual framework.

The work on the conceptual framework is being done in phases. As indicated in the chart below, an exposure draft (ED) of phase A related to objectives and qualitative characteristics was issued in 2007. In addition, a discussion paper (DP) related to the reporting entity (phase D) was also issued in 2007.

The IASB and the FASB face a difficult task in attempting to update, modify, and complete a converged conceptual framework. There are many difficult issues. For example: How do we trade off characteristics such as highly relevant information that is difficult to verify? How do we define control when we are developing a definition of an asset? Is a liability the future sacrifice itself or the obligation to make the sacrifice? Should a single measurement method, such as historical cost or fair value, be used, or does it depend on whether it is an asset or liability that is being measured? We are optimistic that the new document will be a significant improvement over its predecessors and will lead to principle-based standards that help users of the financial statements make better decisions.

FASB Codification References

FASB ASC 820-10. [Predecessor literature: Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 157, "Fair Value Measurement"(Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, September 2006).]

FASB ASC 825-10-25. [Predecessor literature: "The Fair Value Option for Financial Assets and Liabilities," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 159 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2007).]

FASB ASC 718-10. [Predecessor literature: "Share-Based Payment," Financial Accounting Standards No. 123(R) (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2004).]

What is a conceptual framework? Why is a conceptual framework necessary in financial accounting?

What are the primary objectives of financial reporting as indicated in Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 1?

What is meant by the term "qualitative characteristics of accounting information"?

Briefly describe the two primary qualities of useful accounting information.

According to the FASB conceptual framework, the objectives of financial reporting for business enterprises are based on the needs of the users of financial statements. Explain the level of sophistication that the Board assumes about the users of financial statements.

What is the distinction between comparability and consistency?

Why is it necessary to develop a definitional framework for the basic elements of accounting?

Expenses, losses, and distributions to owners are all decreases in net assets. What are the distinctions among them?

Revenues, gains, and investments by owners are all increases in net assets. What are the distinctions among them?

What are the four basic assumptions that underlie the financial accounting structure?

The life of a business is divided into specific time periods, usually a year, to measure results of operations for each such time period and to portray financial conditions at the end of each period.

This practice is based on the accounting assumption that the life of the business consists of a series of time periods and that it is possible to measure accurately the results of operations for each period. Comment on the validity and necessity of this assumption.

What has been the effect of this practice on accounting? What is its relation to the accrual system? What influence has it had on accounting entries and methodology?

What is the basic accounting problem created by the monetary unit assumption when there is significant inflation? What appears to be the FASB position on a stable monetary unit?

The chairman of the board of directors of the company for which you are chief accountant has told you that he has little use for accounting figures based on cost. He believes that replacement values are of far more significance to the board of directors than "out-of-date costs." Present some arguments to convince him that accounting data should still be based on cost.

What is the definition of fair value?

What is the fair value option? Explain how use of the fair value option reflects application of the fair value principle.

Briefly describe the fair value hierarchy.

When is revenue generally recognized? Why has that date been chosen as the point at which to recognize the revenue resulting from the entire producing and selling process?

Selane Eatery operates a catering service specializing in business luncheons for large corporations. Selane requires customers to place their orders 2 weeks in advance of the scheduled events. Selane bills its customers on the tenth day of the month following the date of service and requires that payment be made within 30 days of the billing date. Conceptually, when should Selane recognize revenue related to its catering service?

What is the difference between realized and realizable? Give an example of where the concept of realizable is used to recognize revenue.

What is the justification for the following deviations from recognizing revenue at the time of sale?

Installment sales method of recognizing revenue.

Recognition of revenue at completion of production for certain agricultural products.

The percentage-of-completion basis in long-term construction contracts.

Mogilny Company paid $135,000 for a machine in 2010. The Accumulated Depreciation account has a balance of $46,500 at the present time. The company could sell the machine today for $150,000. The company president believes that the company has a "right to this gain." What does the president mean by this statement? Do you agree?

Three expense recognition methods (associating cause and effect, systematic and rational allocation, and immediate recognition) were discussed in the text under the expense recognition principle. Indicate the basic nature of each of these expense recognition methods and give two examples of each.

Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 5 identifies four characteristics that an item must have before it is recognized in the financial statements. What are these four characteristics?

Briefly describe the types of information concerning financial position, income, and cash flows that might be provided: (a) within the main body of the financial statements, (b) in the notes to the financial statements, or (c) as supplementary information.

In January 2011, Janeway Inc. doubled the amount of its outstanding stock by selling on the market an additional 10,000 shares to finance an expansion of the business. You propose that this information be shown by a footnote on the balance sheet as of December 31, 2010. The president objects, claiming that this sale took place after December 31, 2010, and, therefore, should not be shown. Explain your position.

Describe the two major constraints inherent in the presentation of accounting information.

What are some of the costs of providing accounting information? What are some of the benefits of accounting information? Describe the cost-benefit factors that should be considered when new accounting standards are being proposed.

How are materiality (and immateriality) related to the proper presentation of financial statements? What factors and measures should be considered in assessing the materiality of a misstatement in the presentation of a financial statement?

The treasurer of Landowska Co. has heard that conservatism is a doctrine that is followed in accounting and, therefore, proposes that several policies be followed that are conservative in nature. State your opinion with respect to each of the policies listed below.

The company gives a 2-year warranty to its customers on all products sold. The estimated warranty costs incurred from this year's sales should be entered as an expense this year instead of an expense in the period in the future when the warranty is made good.

When sales are made on account, there is always uncertainty about whether the accounts are collectible. Therefore, the treasurer recommends recording the sale when the cash is received from the customers.

A personal liability lawsuit is pending against the company. The treasurer believes there is an even chance that the company will lose the suit and have to pay damages of $200,000 to $300,000. The treasurer recommends that a loss be recorded and a liability created in the amount of $300,000.

The inventory should be valued at "cost or market, whichever is lower" because the losses from price declines should be recognized in the accounts in the period in which the price decline takes place.

The company changed its inventory method to FIFO from weighted-average, which had been used in prior years.

The company disposed of one of the two subsidiaries that had been included in its consolidated statements for prior years.

The estimated remaining useful life of plant property was reduced because of obsolescence.

The company is using an inventory valuation method that is different from those used by all other companies in its industry.

The annual reports of Best Buy Co. are audited by certified public accountants.

Black & Decker and Cannondale Corporation both use the FIFO cost flow assumption.

Starbucks Corporation has used straight-line depreciation since it began operations.

Motorola issues its quarterly reports immediately after each quarter ends.

Retained earnings

Sales

Additional paid-in capital

Inventory

Depreciation

Loss on sale of equipment

Interest payable

Dividends

Gain on sale of investment

Issuance of common stock

The economic activities of FedEx Corporation are divided into 12-month periods for the purpose of issuing annual reports.

Solectron Corporation, Inc. does not adjust amounts in its financial statements for the effects of inflation.

Walgreen Co. reports current and noncurrent classifications in its balance sheet.

The economic activities of General Electric and its subsidiaries are merged for accounting and reporting purposes.

Norfolk Southern Corporation reports revenue in its income statement when it is earned instead of when the cash is collected.

Yahoo, Inc. recognizes depreciation expense for a machine over the 2-year period during which that machine helps the company earn revenue.

Oracle Corporation reports information about pending lawsuits in the notes to its financial statements.

Eastman Kodak Company reports land on its balance sheet at the amount paid to acquire it, even though the estimated fair value is greater.

Greco's Farms, Inc. reports agricultural crops on its balance sheet at fair value.

Rafael Corporation does not accrue a contingent lawsuit gain of $650,000.

Willis Company does not disclose any information in the notes to the financial statements unless the value of the information to financial statement users exceeds the expense of gathering it.

Favre Corporation expenses the cost of wastebaskets in the year they are acquired.

Blair Co. has reported a positive trend in earnings over the last 3 years. In the current year, it reduces its bad debt allowance to ensure another positive earnings year. The impact of this adjustment is equal to 3% of net income.

Hindi Co. has an extraordinary gain of $3.1 million on the sale of plant assets and a $3.3 million loss on the sale of investments. It decides to net the gain and loss because the net effect is considered immaterial. Hindi Co.'s income for the current year was $10 million.

Damon Co. expenses all capital equipment under $25,000 on the basis that it is immaterial. The company has followed this practice for a number of years.

Land.

Unamortized bond premium.

Depreciation expense on equipment.

Merchandise inventory.

Prepaid insurance.

Target uses the lower of cost or market basis to value inventories.

Target was involved in litigation over the last year. This litigation is disclosed in the financial statements.

Target allocates the cost of its depreciable assets over the life it expects to receive revenue from these assets.

Target records the purchase of a new Dell PC at its cash equivalent price.

Legal fees paid in connection with the purchase of land are $1,500.

Eduardo, Inc. paves the driveway leading to the office building at a cost of $21,000.

A meat market purchases a meat-grinding machine at a cost of $3,500.

On June 30, Monroe and Meno, medical doctors, pay 6 months' office rent to cover the month of July and the next 5 months.

Smith's Hardware Company pays $9,000 in wages to laborers for construction on a building to be used in the business.

Alvarez's Florists pays wages of $2,100 for November to an employee who serves as driver of their delivery truck.

What is the quality of information that enables users to confirm or correct prior expectations?

Identify the two overall or pervasive constraints developed in SFAC No. 2.

The chairman of the SEC at one time noted, "If it becomes accepted or expected that accounting principles are determined or modified in order to secure purposes other than economic measurement, we assume a grave risk that confidence in the credibility of our financial information system will be undermined." Which qualitative characteristic of accounting information should ensure that such a situation will not occur? (Do not use reliability.)

Muruyama Corp. switches from FIFO to average cost to FIFO over a 2-year period. Which qualitative characteristic of accounting information is not followed?

Assume that the profession permits the savings and loan industry to defer losses on investments it sells, because immediate recognition of the loss may have adverse economic consequences on the industry. Which qualitative characteristic of accounting information is not followed? (Do not use relevance or reliability.)

What are the two primary qualities that make accounting information useful for decision making?

Watteau Inc. does not issue its first-quarter report until after the second quarter's results are reported. Which qualitative characteristic of accounting is not followed? (Do not use relevance.)

Predictive value is an ingredient of which of the two primary qualities that make accounting information useful for decision-making purposes?

Duggan, Inc. is the only company in its industry to depreciate its plant assets on a straight-line basis. Which qualitative characteristic of accounting information may not be followed? (Do not use industry practices.)

Roddick Company has attempted to determine the replacement cost of its inventory. Three different appraisers arrive at substantially different amounts for this value. The president, nevertheless, decides to report the middle value for external reporting purposes. Which qualitative characteristic of information is lacking in these data? (Do not use reliability or representational faithfulness.)

Relevance

Timeliness

Representational faithfulness

Reliability

Verifiability

Comparability

Predictive value

Neutrality

Consistency

Feedback value

Instructions

Identify the appropriate qualitative characteristic(s) to be used given the information provided below.

Qualitative characteristic being employed when companies in the same industry are using the same accounting principles.

Quality of information that confirms users' earlier expectations.

Imperative for providing comparisons of a company from period to period.

Ignores the economic consequences of a standard or rule.

Requires a high degree of consensus among individuals on a given measurement.

Predictive value is an ingredient of this primary quality of information.

Two qualitative characteristics that are related to both relevance and reliability.

Neutrality is an ingredient of this primary quality of accounting information.

Two primary qualities that make accounting information useful for decision-making purposes.

Issuance of interim reports is an example of what primary ingredient of relevance?

Assets

Distributions to owners

Expenses

Liabilities

Comprehensive income

Gains

Equity

Revenues

Losses

Investments by owners

Instructions

Identify the element or elements associated with the 12 items below.

Arises from peripheral or incidental transactions.

Obligation to transfer resources arising from a past transaction.

Increases ownership interest.

Declares and pays cash dividends to owners.

Increases in net assets in a period from nonowner sources.

Items characterized by service potential or future economic benefit.

Equals increase in assets less liabilities during the year, after adding distributions to owners and subtracting investments by owners.

Arises from income statement activities that constitute the entity's ongoing major or central operations.

Residual interest in the assets of the enterprise after deducting its liabilities.

Increases assets during a period through sale of product.

Decreases assets during the period by purchasing the company's own stock.

Includes all changes in equity during the period, except those resulting from investments by owners and distributions to owners.

Economic entity assumption

Going concern assumption

Monetary unit assumption

Periodicity assumption

Historical cost principle

Fair value principle

Expense recognition principle

Full disclosure principle

Cost-benefit relationship

Materiality

Industry practices

Conservatism

Instructions

Identify by number the accounting assumption, principle, or constraint that describes each situation on the next page. Do not use a number more than once.

Allocates expenses to revenues in the proper period.

Indicates that fair value changes subsequent to purchase are not recorded in the accounts. (Do not use revenue recognition principle.)

Ensures that all relevant financial information is reported.

Rationale why plant assets are not reported at liquidation value. (Do not use historical cost principle.)

Anticipates all losses, but reports no gains.

Indicates that personal and business record keeping should be separately maintained.

Separates financial information into time periods for reporting purposes.

Permits the use of fair value valuation in certain industries. (Do not use fair value principle.)

Requires that information significant enough to affect the decision of reasonably informed users should be disclosed. (Do not use full disclosure principle.)

Assumes that the dollar is the "measuring stick" used to report on financial performance.

Instructions

Select the assumption, principle, or constraint that most appropriately justifies these procedures and practices. (Do not use qualitative characteristics.)

Fair value changes are not recognized in the accounting records.

Lower of cost or market is used to value inventories.

Financial information is presented so that investors will not be misled.

Intangible assets are capitalized and amortized over periods benefited.

Repair tools are expensed when purchased.

Agricultural companies use fair value for purposes of valuing crops.

Each enterprise is kept as a unit distinct from its owner or owners.

All significant postbalance sheet events are reported.

Revenue is recorded at point of sale.

All important aspects of bond indentures are presented in financial statements.

Rationale for accrual accounting.

The use of consolidated statements is justified.

Reporting must be done at defined time intervals.

An allowance for doubtful accounts is established.

All payments out of petty cash are charged to Miscellaneous Expense. (Do not use conservatism.)

Goodwill is recorded only at time of purchase.

No profits are anticipated and all possible losses are recognized.

A company charges its sales commission costs to expense.

Instructions

Assume that you are the auditor of Weller, Inc. and that you have been asked to explain the appropriate accounting and related disclosure necessary for each of these items.

The company decided that, for the sake of conciseness, only net income should be reported on the income statement. Details as to revenues, cost of goods sold, and expenses were omitted.

Equipment purchases of $170,000 were partly financed during the year through the issuance of a $110,000 notes payable. The company offset the equipment against the notes payable and reported plant assets at $60,000.

Weller has reported its ending inventory at $2,100,000 in the financial statements. No other information related to inventories is presented in the financial statements and related notes.

The company changed its method of valuing inventories from weighted-average to FIFO. No mention of this change was made in the financial statements.

In each of the situations, discuss the appropriateness of the journal entries in terms of generally accepted accounting principles.

The president of Gonzales, Inc. used his expense account to purchase a new Suburban solely for personal use. The following journal entry was made.

Merchandise inventory that cost $620,000 is reported on the balance sheet at $690,000, the expected selling price less estimated selling costs. The following entry was made to record this increase in value.

The company is being sued for $500,000 by a customer who claims damages for personal injury apparently caused by a defective product. Company attorneys feel extremely confident that the company will have no liability for damages resulting from the situation. Nevertheless, the company decides to make the following entry.

Because the general level of prices increased during the current year, Gonzales, Inc. determined that there was a $16,000 understatement of depreciation expense on its equipment and decided to record it in its accounts. The following entry was made.

Gonzales, Inc. has been concerned about whether intangible assets could generate cash in case of liquidation. As a consequence, goodwill arising from a purchase transaction during the current year and recorded at $800,000 was written off as follows.

Because of a "fire sale," equipment obviously worth $200,000 was acquired at a cost of $155,000. The following entry was made.

Instructions

Depreciation expense on the building for the year was $60,000. Because the building was increasing in value during the year, the controller decided to charge the depreciation expense to retained earnings instead of to net income. The following entry is recorded.

Materials were purchased on January 1, 2010, for $120,000 and this amount was entered in the Materials account. On December 31, 2010, the materials would have cost $141,000, so the following entry is made.