Chapter 10

The mix, the music and the monitors

10.1 Physics or psychology?

The recording personnel in many small studios seem endlessly to be searching for that magic pair of loudspeakers that they can trust for whatever type of music they mix on them. They swear by one pair of loudspeakers as being their ultimate reference, then after the first mix that fails to sound as good on another system – say at home, or in the A&R department office – they lose all faith in them and seek a new ‘reference’. Until they find that new reference, they may live in a state of unease, and even panic, as their perceived anchor to ‘reality’ loses its grip. Why such well-trusted loudspeakers could suddenly lose their authority has long puzzled many people, but the fact is that the loudspeakers, themselves, rarely are the sources of the problems. They usually have not changed at all between the days when they were used to make the ‘magic’ mixes and the days when the mixes were not perceived to travel so well. As often as not, the problem lies not in the loudspeakers, but in the music, as we shall see later. However, many other things can also change along the way, such as the perception of the recording engineers who are using them. They often seem to pass through the following phases during the period of use of any, one type of loudspeaker system:

1) First audition – forming an initial opinion.

2) Getting to know them – evaluating and refining the opinion.

3) Increase in worries about minor aspects of the sound.

4) Boredom with the sound and doubts about its ‘accuracy’.

In so many instances, after finding a new, favourite loudspeaker, people say that they have finally found a monitor to which they can accurately refer their recordings and mixes, only to find that six months later they again declare them to be ‘wrong’ and unusable. If in reality nothing in the control room had changed in six months, and it is very doubtful that a pair of good quality loudspeakers would have changed their characteristics in such a short time of use, then the only thing which could have changed is the way in which the users were perceiving the sound.

Sounds exist only in peoples’ brains. We all hear differently – we all perceive the sounds differently – so it is difficult to compare musical perceptions, and no doubt we all have our individual hierarchies of priorities in terms of what is important in any given musical rendition. Furthermore, almost any experienced recording engineer or producer would freely admit that on any given day, the ‘accuracy’ of the monitor system or the ‘rightness’ of a mix can seem to be dependent upon things such as the general mood the day before, or how well they have slept. Less experienced people, however, often believe that their hearing system is always accurate and ‘highly tuned’. If, one day, a monitor system does not sound ‘right’ to them, or even when somebody else tells them that they do not sound right, they call people in to carry out a thorough test of the system, and it is often some absurd response change, carried out by the person or persons called in to make the adjustments, which ultimately placates them. But perhaps something is heard with the new settings that were not noticed the day before, so in the minds of the recordists, this signifies that more detail is now being perceived. The confirmation by measurement that all was previously well with the loudspeakers frequently does nothing to deter the requests for something to be changed.

In fact, quite often, rather than the measurements confirming that all was well, they can induce a sense of even greater insecurity, because some recording staff may feel that their comments were not being listened to, and that their integrity and reputation were being undermined. At this point something must be found so that honour and credibility can be restored. Therefore, under growing pressure to come up with something, and whilst being influenced by what are often misleading descriptions of the perceived problems, perhaps some illogical change will be made to the monitoring response which nonetheless seems to provide a credible ‘re-alignment’ of the loudspeaker. The change has a novelty value which brings a new ‘reality’ with it. Honour has also been satisfied, because a problem was found and rectified, yet the probability is that in almost all cases, no physical problem existed and no aspect of the loudspeaker response had actually changed until the adjustment was made. The only problem that the adjustment really fixed was the one in the mind of the person reporting the problem, and it possibly, in reality, took the loudspeaker response in a direction away from absolute accuracy.

So what underlies this sort of insecurity and variability of perception? There is little doubt that mood can affect perception. The stress resulting from a rejection of a mix by a recording company can certainly deflate the confidence, especially of less experienced sound recordists, and once doubt and insecurity sets in it develops a momentum of its own. Nevertheless, the problem under discussion here is too frequent and widespread to be simply a case of a confidence crisis, because even when good moods are restored for all parties, the problem of the mix being incompatible between a number of loudspeaker systems may still remain, even though other mixes done on the same monitor system may not have suffered from the same problem.

10.2 The musical dependence of compatibility

The symptoms of a very common problem tend to be that a mix which was done on a certain monitor system, in which the mixing personnel used to have great confidence, and which sounded great in the control room, did not sound good on the radio, or in some other important reference place. They then compare this situation to that of a mix which had been done some months earlier, (of a different piece of music – in almost all cases) on the selfsame monitor system, which sounded great in all the places in which it had been checked.

The perceived implication is normally that if the earlier mix sounded good in the control room, and then proceeded to sound good in several other ‘trusted’ locations, then it must be the case that the later mix, which did not sound good in the other locations, must have been incorrectly mixed. This is usually thought to be due to a changed control room monitor system performance misleading the mixing personnel into making erroneous judgements. However, if a new monitor system is used, and a more compatible mix results, it almost never seems to be the case that anybody then bothers to remix the earlier music, which showed good general compatibility, on the new reference system, and then play it back in the other reference places to see if it still sounded good on all the systems. This is a crucial test, because the musical source material can be very influential in terms of the compatibility between loudspeaker systems. It could be the case that the musical arrangement was the source of the compatibility problems. This fact can easily be demonstrated. Two monitor systems in a control room can often be adjusted to sound almost identical on one voice or instrument, only to then sound very different from each other on a different musical signal.

It is also common knowledge that some music, mixed by certain people in certain famous studios, seems to sound good wherever it is played, yet many mixes, done by lesser mortals, only sound good on a few types of loudspeaker. Many people seem to think that some special skills or equipment are being used in the recording, mixing or mastering processes by the people producing the ‘sound good anywhere’ mixes. They believe that they must have some special, ‘truthful’, monitor systems, and wonder what they can be. But what people often fail to remember is that the top people in the top studios are also often working with very highly skilled and experienced musicians, who also have a lot of experience in how to achieve well-arranged, musically balanced recordings, which show a remarkable degree of tolerance to minor level or equalisation changes.

When working in recording studios, up until the early 1970s, an almost universally present member of the recording team was the musical arranger. Things were worked out and rehearsed in advance, and each instrument had its own place in both the time and the frequency domains. It was very much a part of the job of the musical arranger to make sure that instruments did not clash with one another either in terms of time, pitch, or timbre. However, as things have progressed, the recording process had gradually become somewhat more anarchic, and this had led to mixes in which many instruments may be fighting for the same time and frequency spaces. They need to be so delicately balanced in order to sound ‘right’ that even minor differences in any aspect of the response of another loudspeaker system can be sufficient to render the balance unsatisfactory. Quite arbitrarily, the loudspeakers on which music is mixed can often be declared to be inaccurate, but from the plots of Figure 11.1, we can see quite clearly how no loudspeakers are technically accurate.

10.2.1 Sine waves and pink noise

Let us think of the compatibility problem this way. If we put a mid frequency sine wave into five good quality loudspeakers in turn, then adjust all the levels to give the same sound pressure, it is probable, unless serious distortion is present in any of the systems, that the sine wave will sound the same in each case. The sine wave represents just about the simplest signal source that could be used. Now let us go to the other extreme, and use a signal that contains all frequencies, such a pink noise. Almost certainly, even after the most careful adjustments, the pink noise would sound noticeably different when reproduced by each of the five different loudspeakers – its tone colour would certainly change – and it may even sound different if played alternately through the two loudspeakers of a matched stereo pair.

The significance of this, in musical terms, is that the more that a musical mix tends towards a noise signal (in many cases this means the more complicated that it becomes) the more it will tend to sound different when switched from one loudspeaker to another. A lightly blown flute will therefore tend to sound more similar when reproduced by a wide range of loudspeakers than would be the case for a fuzz guitar. The latter could noticeably change in timbre, or even in pitch, even when played on relatively similar loudspeakers.

So, the more information that exists in a musical mix, the more of it there is to get upset by minor response differences. Clean and simple mixes, or mixes of music which is well arranged in terms of the temporal and frequency distribution of the different musical parts, will tend to be more robust than mixes which are highly congested and/or heavily processed. Many of the recordings of Dire Straits always seem to sound musically balanced no matter on whatever systems they are played, from an audiophile hi-fi system to a hotel radio alarm clock. Further consideration of their excellent musical arrangements surely goes some way to explaining why this is the case. This situation can puzzle many people who have gone to great lengths to ensure that their monitors are well set up, and they are very respectably flat when analysed with pink noise. However, as discussed in Chapter 9, there is far more to a loudspeaker response than its steady-state pressure amplitude response.

10.3 Real responses vs. preconceived ideas

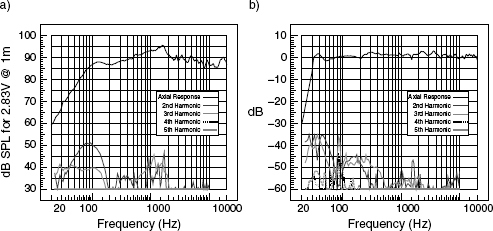

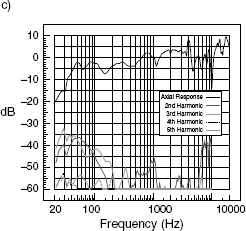

There is a tendency in much of the music recording world to believe that the responses of all ‘good’ loudspeakers are more or less the same, and that it is merely the precise application of their proprietary construction techniques which makes the minor differences between them, but the reality is somewhat brutally different, as Figures 10.1 to 10.5 show. The plots show five aspects of the responses of a Yamaha NS10M and two of its ‘competitors’ in the field of close-range music monitoring. These measurements were all made in one, fixed position in the same, large, anechoic chamber. Even before any room response anomalies could be considered, such as those given rise to by directivity differences, the simple, on-axis, anechoic responses of the three loudspeakers, as shown in Figure 10.1, are different to the point of absurdity if they are all ostensibly for the same sort of professional use. The levels of harmonic distortion are also quite different. Given their disparate responses, there is simply no way that a wide range of musical mixes could sound similar when alternately played on each of the three loudspeakers, but the degree to which they do sound different may well be largely a question of instrumentation and arrangement, rather than simply a matter of the balance of the mix.

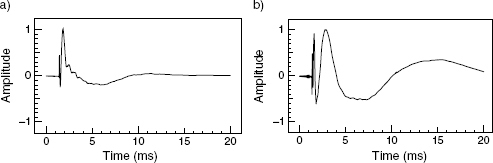

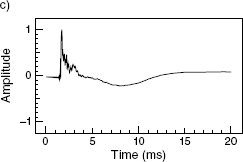

Figure 10.1 Pressure amplitude and harmonic distortion responses of three loudspeakers. a) Yamaha NS10M. b) Genelec S30D. c) SAE TM160A

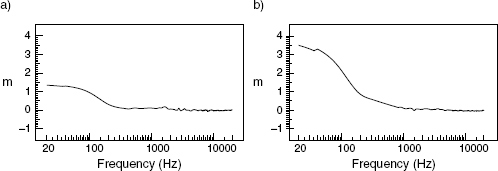

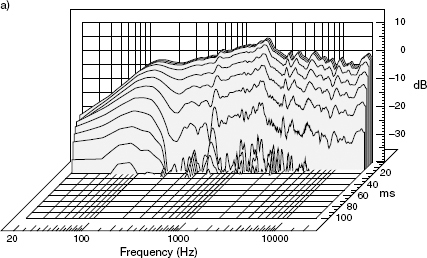

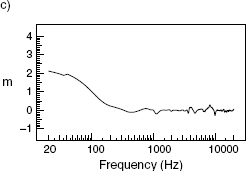

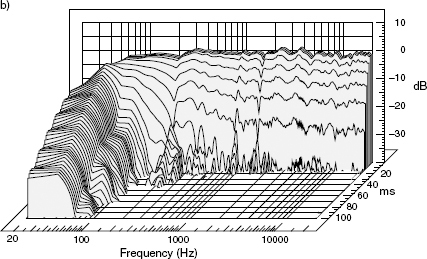

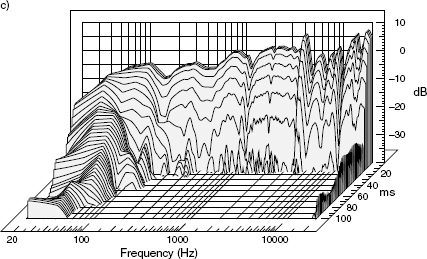

Figure 10.2 shows the acoustic source plots of the same three loudspeakers referred to in the previous paragraph. As each metre on the vertical scale represents about 3 milliseconds, it can be seen that from the Yamaha the 50 Hz component of the signal is delayed by about 4 ms (about 1.3 metres). From the SAE the delay is around 6ms, and for the Genelec, the delay is in the order of ten milliseconds. The plots of Figure 10.2 show the delay in the attack of the low frequencies, but by contrast, Figure 10.3 shows the delay in the decays. The waterfall plots show how the different frequencies decay in response to any signal which excites the loudspeakers. Again, the temporal response variations are enormous. On these plots, the 60 Hz component from the Yamaha is 30 dB down by 20 ms; the Genelec is barely down by 30 dB even after 100 ms, and the SAE response lies somewhere in-between. How can a bass drum sound the same on each loudspeaker? These longer responses can play havoc with the balance between bass drums and bass guitars.

Figure 10.2 Acoustic source plots. a) Yamaha NS10M. b) Genelec S30D. c) SAE TM160A

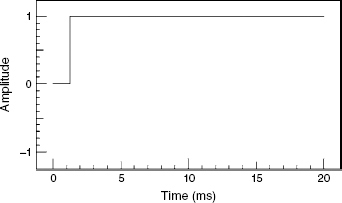

Figure 10.4 shows an electrical step function. An easy way of generating such a function would be to connect a 11/2 volt battery to the input terminals of a loudspeaker – active or passive. Figure 10.5 shows the time response (which is in fact the waveform response) of the same three loudspeakers as shown in Figures 10.1 to 10.3 when subjected to a step-function stimulus. Once again, the resulting waveforms are very different. They could hardly be expected to sound the same, and indeed they do not sound the same. How a mix would ‘travel’ from one pair of these loudspeakers to another would depend on the musical arrangement, the frequency range which the music covered, and many other factors. The musical style, or genre, may determine on which loudspeakers the mix was deemed to sound most right, and this may, in turn, lead people to false conclusions about which loudspeaker was generally most right. Surely, though, such vaguearies can hardly be considered to be a desirable part of any ‘reference monitoring’ process. From Figures 10.1 to 10.3 it is easy to understand how pink noise would sound very different if played through each pair of loudspeakers in turn. It should be equally easy to appreciate how spectrally complex music would suffer a similar fate.

With such a widely varying range of loudspeakers in use as so-called ‘references’, there is little wonder that no, one, mix, done on any set of monitor loudspeakers, can be expected to sound equal on all of them. Nevertheless, a well-distributed musical balance, of well-arranged music, can go some considerable way to ameliorate the problems, but much modern music is very complex. Especially when music has been produced entirely on one set of loudspeakers, it is inevitable that it will tend to sound wrong on many other systems in many different rooms. The fact that so many different references are available seems to devalue the very concept of their use as references. Furthermore, the ear, itself, especially as part of an overall system of musical perception, has also been shown to be a rather variable reference, and it is usually only a combination of experience and confidence which can solve this problem. This is exactly what people are usually paying for when they engage the services of a reputable mastering engineer.

Figure 10.3 Waterfall plots. a) Yamaha NS10M. b) Genelec S30D. c) SAE TM160A

Figure 10.4 An electrical step-function waveform

Figure 10.5 Step-function responses of the three loudspeakers shown in Figures 10.1 to 10.3. a) Yamaha NS10M. b) Genelec S30D. c) SAE TM160A

It is also interesting to note that in general, classical recordists tend to use different loudspeakers to rock music recordists. This fact serves to highlight how far we are from perfection in loudspeaker design, because a perfect loudspeaker would be an incontrovertible reference, unless, that is, the buyers of one type of music recording had a general trend towards all using a specific genre of imperfect loudspeaker in their homes, and to which it seemed appropriate to make mixing compromises. To some extent this case actually exists, with the vast majority of domestic listeners to rock music using small, bass reflex enclosures, the problems of which will be discussed further in the next chapter.

It seems to be the case that highly experienced and successful recording personnel stick tightly to their chosen monitor systems, and they are very reluctant to change them – even when they know them to be lacking. Conversely, many inexperienced recording personnel provide the bread and butter for the mid-priced monitor loudspeaker industry, rushing to change their references every time that somebody complains about the failure of a mix to travel well. The reality is that in the latter case, the problem usually lies in the music and the mix, and not in the loudspeakers. A robust musical arrangement, well played and well mixed, will travel. A complex mix of a poor arrangement will probably not fare so well.

Acknowledgement

This chapter was partly inspired by the following paper which, although on a different subject, highlighted many parallel concepts.

Bailey, Mark; ‘Perception of Music: The Element of Surprise’, Proceedings of the Institute of Acoustics, Vol 24, Part 8, Reproduced Sound 18 conference, Stratford-upon-Avon, UK (November 2002)