4

The process of mixing

Mixing and the production chain

There are differences between the production processes of recorded music and sequenced music, and these differences affect the mixing process.

Recorded music

Figure 4.1 Common production chain for recorded music.

Figure 4.1 illustrates the common production chain for recorded music. Producers may give input at each stage, but they are mostly concerned with the arrangement and recording stages. Each stage has an impact on the subsequent stage but each of the stages can be carried out by different people.

Mixing is largely dependent on both the arrangement and recording stages. For example, an arrangement might involve only one percussion instrument, a shaker, for example. If panned center in a busy mix, it is most likely to be masked by other instruments. But panning it to one side can create an imbalanced stereo image. It might be easier for the mixing engineer to have a second percussion instrument, say a tambourine, so the two can be panned left and right. A wrongly placed microphone during the recording stage can result in a lack of body for the acoustic guitar. Recreating this missing body during mixdown is a challenge. Some recording decisions are, to be sure, mixing decisions. For example, the choice of stereo-miking technique for drum overheads determines the localization and depth of the various drums in the final mix. Altering these aspects during mixdown takes effort.

Mixing engineers, when a separate entity in the production chain, commonly face arrangement or recording issues such as those mentioned above. There is such a strong link between the arrangement, recordings, and mix that it is actually unreasonable for a producer or a recording engineer to have no mixing experience whatsoever. A good producer anticipates the mix. There is an enormous advantage to having a single person helping with the arrangement, observing the recording process, and mixing the production. This ensures that the mix is borne in mind throughout the production process.

There is some contradiction between the nature of the recording and mixing stages. The recording stage is mostly concerned with the capturing of each instrument so that the sound is as good as it possibly can be (although to a varying degree, instruments are recorded so their sound fits existing sounds). During the mixing stage, different instruments have to be combined, and their individual sounds might not work perfectly well in the context of a mix. For example, the kick and bass might sound unbelievably good when each is played in isolation, but combined they might mask one another. Filtering the bass might make it thinner, but will work better in the mix context. Mixing often involves altering recordings to fit into the mix—no matter how well instruments were recorded.

Sequenced music

The production process of sequenced music (Figure 4.2) is very different in nature to that of recorded music. In a way, it is a mixture of songwriting, arranging, and mixing—producing for short. This affects mixing in two principal ways. First, today’s DAWs, on which most sequenced music is produced, make it easy to mix as you go. The mix is an integral part of the project file, unlike a console mix that is stored separately from the multitrack. Second, producers commonly select samples or new sounds while the mix is playing along; unconsciously, they choose sounds based on how well they fit into the existing mix. A specific bass preset might be dismissed if it lacks definition in the mix, and a lead synth might be chosen based on the reverb that it brings with it. Some harmonies and melodies might be transposed so they blend better into the mix. The overall outcome of this is that sequenced music arrives at the mixing stage partly mixed.

Figure 4.2 Common production chain for sequenced music.

As natural and positive as this practice may seem, it causes a few mixing problems that are common to sequenced music. To begin with, synthesizer manufacturers and sample-library publishers often add reverb (or delay) to presets in order to make them sound bigger. These reverbs are permanently imprinted into the multitrack submission and have restricted depth, stereo images, and frequency spectrums that might not integrate well with the mix. Generally speaking, dry, synthesized sounds and mono samples offer more possi bilities during mixdown. In addition, producers sometimes get attached to a specific mixing treatment they have applied, such as the limiting of a snare drum, and leave these treat ments intact. Very often, the processing is done using inferior plugins, in a relatively short time, and with very little attention to how the processing affects the overall mix. Flat dynamics due to over-compression or ear-piercing highs are just two issues that might have to be rectified during the separate mixing stage.

Sequenced music often arrives at the mixing stage partly mixed—which could be more of a hindrance and less of a help.

Recording

They say that all you need to get killer drum sounds is a good drum kit in a good room, fresh skins, a good drummer, good microphones, good preamps, some good EQs, nice gates, nicer compressors, and a couple of good reverbs. Remove one of these elements and you will probably find it harder to achieve that killer sound; remove three and you may never achieve it.

The quality of the recorded material has an enormous influence on the mixing stage. A famous saying is “garbage in; garbage out.” Flawed recordings can be rectified to a certain extent during mixing, but there are limitations. Good recordings leave the final mix quality to the talent of the mixing engineer, and offer greater creative opportunities.

Nevertheless, experienced mixing engineers can testify to how drastically the process of mixing can improve poor recordings, and how even low-budget recordings can be turned into an impressive mix. Much of this is thanks to the time, talent, and passion of the mixing engineer, and sometimes involves a few mixing “cheats,” such as the triggering of drum samples and re-amping of guitars.

Garbage in; garbage out. Still, a lot can be improved during mixdown.

Arrangement

The arrangement (or instrumentation) largely determines which instruments play, when, and how. Mixing-wise, the most relevant factor of the arrangement is its density. A sparse arrangement (Figure 4.3a) will call for a mix that fills various gaps in the frequency, stereo, and time domains. An example of this would be an arrangement based solely on an acoustic guitar and one vocal track. The mixing engineer’s role in such a case is to create something out of very little, or, at the other extreme, a busy arrangement (Figure 4.3b), where the challenge is to create a space in the mix for each instrument. It is harder to lay emphasis on a specific instrument, or emphasize fine details in a busy mix. Technically speaking, masking is the cause.

Figure 4.3 Sparse vs. dense arrangement.

![]()

Both Andy Wallace and Nigel Godrich faced sparse arrangements consisting of a guitar and vocal only in sections of “Polly” by Nirvana and “Exit Music” by Radiohead. Each tackled it in a different way—Wallace chose a plain, intimate mix, with fairly dry vocal and a subtle stereo enhancement for the guitar. Godrich chose to use very dominant reverbs on both the guitar and vocal. It is interesting to note that Wallace chose the latter, reverberant approach on his inspiring mix for “Hallelujah” by Jeff Buckley—an almost seven-minute song with an electric guitar and a single vocal track.

It is not uncommon for the final multitrack to include extra instrumentation along with takes that were recorded as try-outs, or in order to give some choices during mixdown. It is possible, for example, to receive eight power-guitar overdubs for just one song. This is done with the belief that layering eight takes of the same performance will result in an enormous sound. Enormousness aside, properly mixing just two of the eight tracks can sometimes sound much better. There are always opposite situations, where the arrangement is so minimalist that it is very hard to produce a rich, dynamic mix. In such cases, nothing should stop the mixing engineer from adding instruments to the mix—as long as time, talent and ability allow this, and the client approves the additions.

It is acceptable to remove or add to the arrangement during mixdown.

It is worth remembering that the core process of mixing involves both alteration and addition of sounds—a reverb, for example, is an additional sound that occupies space in the frequency, stereo, and time domains. It would therefore be perfectly valid to say that a mix can add to the arrangement. Some producers take this well into account by “leaving a place for the mix”—the famous vocal echo on Pink Floyd’s “Us and Them” is a good example of this. One production philosophy is to keep the arrangements simple, so that greatness can be achieved at the mixing stage.

The mix can add sonic elements to the arrangement.

Editing

Generally, on projects that are not purely sequenced, editing is the final stage before mixing. Editing is subdivided into two types: selective and corrective. Selective editing is primarily concerned with choosing the right takes, and the practice of comping—combining multiple takes into a composite master take. Corrective editing is done to repair a bad performance.

Anyone who has ever engineered or produced in a studio knows that session and professional musicians are a true asset. But as technology is moving forward, enabling more sophisticated performance corrections, mediocre performance is becoming more acceptable—why should we spend money on vocal tuition and studio time when a plugin can make the singer sound in tune? (More than a few audio engineers believe that the general public perception of pitch has sharpened in recent years due to the excessive use of pitch correction.) Drum correction has also become common practice. On big projects, a dedicated editor might work with the producer to do this job. Unfortunately, though, sometimes it is the mixing engineer who is expected to do such a job (although mostly this is done for an additional editing fee).

A lot of corrective editing can be done mechanically. Most drums can be quantized to metronomic precision, and vocals can be made perfectly in tune. Although many pop albums feature such extreme edits, many advocate a more humanized approach that calls for little more than an acceptable performance (perhaps ironically, sequenced music is often humanized to give it feel and swing). Some argue that over-correcting is against all genuine musical values. It is also worth remembering that corrective editing always involves some quality penalty. In addition, audio engineers are much more sensitive to subtle details than most listeners. To give an example, the chorus vocals on Beyoncé’s “Crazy in Love” are late and offbeat, but many listeners don’t notice it.

The mix as a composite

Do individual elements constitute the mix, or does the mix consist of individual elements? Those who believe that individual elements constitute the mix might give more attention to how the individual elements sound, but those who think that the mix consists of individual elements care about how the sound of individual elements contributes to the overall mix. It is worth remembering that the mix—as a whole—is the final product. This is not to say that the sound of individual elements is not important, but the overall mix takes priority.

A few examples would be appropriate here. It is very common to apply a high-pass filter on a vocal in order to remove muddiness and increase its definition. This type of treatment, which is done to various degrees, can sometimes make the vocals sound utterly unnatural, especially when soloed. However, this unnatural sound often works extremely well in mix context. Another example: vocals can be compressed while soloed, but the compression can only be perfected when the rest of the mix is playing as well—level variations might become more noticeable with the mix as a reference. Overheads compression should also be evaluated against the general dynamics and intensity of the mix.

The question even goes into the realm of psychoacoustics—our brain can separate one sound from a group of sounds. So, for example, while equalizing a kick we can isolate it from the rest of the mix in our head. However, we can just as well listen to the whole mix while equalizing a kick, and by doing so improve the likelihood of the kick sounding better in mix context. This might seem a bit abstract and unnatural—while we manipulate something, it is normal to want to clearly hear the effect. The temptation to focus on the manipulated element always exists, but there’s a benefit to listening to how the manipulation affects the mix as a whole.

It can be beneficial to employ mix-perspective rather than element-perspective, even when treating individual elements.

Where to start

Preparations

Projects submitted to mixing engineers are usually accompanied by documentation— session notes, track sheets, edit notes, etc.—and all have to be examined before mixing commences. Clients often have their ideas, guidelines, or requirements regarding the mix, which are often discussed at this stage. In addition, there are various technical tasks that might need to be accomplished; these will be discussed shortly.

Auditioning and the rough mix

Unless we were involved in earlier production stages and are thus fluent with the raw tracks, we must listen to what is about to be mixed. Auditioning the raw tracks allows us to learn the musical piece, capture its mood and emotional features, and identify important elements, moments, or problems we will need to rectify. We study our ingredients before we start cooking.

Often, a rough mix (or a monitor mix) is provided with the raw tracks. It can teach much about the song and inspire a particular mixing direction. Even when a rough mix is submitted, creating our own can be extremely useful—in doing so, we familiarize ourselves with the arrangement, structure, quality of recording, and, maybe most importantly, how the musical qualities can be conveyed. Our own rough mix is a noncommittal chance to learn much of what we are dealing with, what has to be dealt with, and how; it can help us to start formulating a mixing plan or vision.

Rough mixes, especially our own, are beneficial.

One issue to be aware of is that it is not unheard of for the artist(s) and/or mixing engineer to unwittingly become so familiar with the rough mix that they use it as an archetype for the final mix. This unconscious adoption of the rough mix is only natural since it often provides the first opportunity to hear how different elements transform and begin to sound like the real thing. However, this could be dangerous territory since rough mixes, by nature, are just that—rough. They are done with little attention to small details, and sometimes involve random try-outs that make little technical or artistic sense. Yet, once accustomed to them, we find it hard without them—a point worth remembering.

The plan

Just bringing faders up and doing whatever seems right is arguably not very effective— a bit like playing a football match without tactics. Every mix is different, and different pieces of music require different approaches. Once we are familiar with the raw material, a plan of action is developed, either in the mind or on paper (putting a plan to paper, often as a bullet list, means we need to expand less effort remembering it, unlike when we keep it in mind). Such a plan can help even when the mixing engineer recorded or produced the musical pieces—it resets the mind from any sonic prejudgments and creates a fresh start to the mixing process. Below is an example of the beginning of a rough plan before mixing commences. As you can see, this plan includes various ideas, from panning positions to the actual equipment to be used; there are virtually no limits to what such a plan might include:

I am going to start by mixing the drumbeat at the climax section. In this production the kick should be loud and in-your-face; I’ll be compressing it using the Distressor, accenting its attack, then adding some sub-bass. The pads will be panned roughly halfway to the extremes and should sit behind everything else. I should also try and distort the lead to tuck in some aggression. I would like it to sound roughly like “Stronger” by Kanye.

It might be hard to get the feel of the mix at the very early stages. Understandably, it is impossible to write a plan that includes each and every step that should be performed. Moreover, such a detailed plan can limit creativity and chance, which are important aspects of mixing. Therefore, instead of one big plan, it can be easier to work using small plans—whenever a small plan is finished, a new evaluation of the mix takes place and a new plan is established. Here is a real-life example of a partial task list from a late mixing stage:

- Kick sounds flat

- Snare too far during the chorus—replace with triggers (chorus only)

- Stereo imbalance for the violins—amend panning

- Solo section: violin reverb is not impressive enough

- Haas guitar still not defined

- Automate snare reverbs

Not every mixing engineer approaches mixing with a detailed plan; some do it spontaneously and in their heads. Yet, there is always some methodology, some procedure being followed.

Mixing is rarely a case of “whatever seems right next.” Have a plan, and make sure you identify what’s important.

Technical vs. creative

The mixing process involves both technical and creative tasks. Technical tasks are generally those that do not actually affect the sound, or those that relate to technical problems with the raw material. They usually require little sonic expertise. Here are a few examples:

- Neutralizing (resetting) the desk—analog desks should be neutralized at the end of each session, but this is not always the case. Line gains and aux sends are the usual suspects that can later cause trouble. Line gains can lead to unbalanced stereo image or unwanted distortion. Aux sends can result in unwanted signals being sent to effects units.

- Housekeeping—projects might require some additional care, sometimes simply for our own convenience. For example, file renaming, removing unused files, consolidating edits, etc.

- Track layout—organizing the appearance order of the tracks so they are convenient to work with. For example, making all the background vocals or drum tracks consecutive in appearance, or having the sub-oscillator next to the kick. Sometimes the tracks are organized in the order in which they will be mixed; sometimes the most important tracks are placed in the center of a large console. Different mixing engineers have different layout preferences to which they usually adhere. This enables faster navigation around the mixer, and increased accessibility.

- Phase check—recorded material can suffer from various phase issues (these are described in detail in Chapter 12). Phase problems can have subtle to profound effects on sounds, and it is therefore important to deal with them at the beginning of the mixing process.

- Control/audio grouping—setting any logical group of instruments as control or audio groups. Common groups are drums, guitars, vocals, etc.

- Editing—any editing or performance correction that might be required.

- Cleaning up—many recordings require the cleaning up of unwanted sounds, such as the buzz from guitar amplifiers. Cleaning up can also include the removal of extraneous sounds such as count-ins, musicians talking, pre-singing coughs, etc. These unwanted sounds are often filtered either by gating, a strip-silence process, or region trimming. (Some of these tasks, if not all, are performed at the end of the mixing stage.)

- Restoration—unfortunately, raw tracks can incorporate noise, hiss, buzz, or clicks. These are more common in low-budget recordings, but can also appear due to degradation issues. It is important to note that clicks might be visible but not audible (inaudible clicks can become audible if being processed by devices such as enhancers or if being played through different D/A converters). Some restoration treatment, de-noising for example, might be applied to solve these problems.

Creative tasks are essentially those that allow us to craft the mix. These might include:

- Using a gate to shape the timbre of a floor tom.

- Tweaking a reverb preset to sweeten a saxophone.

- Equalizing vocals in order to give them more presence.

While mixing, we have a flow of thoughts and actions. The creative process, which consists of many creative tasks, requires a high degree of concentration. Any technical task can distract from or break the creative flow. If, while equalizing a double bass, you find that it is offbeat on the third chorus, you might be tempted to fix the performance straight away (after all, a bad performance can be really disturbing). By the time the editing is done, you might have switched off from the equalizing process or the creative process altogether. It can take some time to get back into the creative mood. It is therefore beneficial to go through all the technical tasks first, which clears the path for a distraction-free creative process.

Technical tasks can interrupt the creative flow. It is better to complete them first.

Which instrument?

Different engineers have a different order in which they mix the different component tracks. There are lots of differences in this business. Some engineers are not committed to one order or another—each production might be mixed in the order they think is most suitable. Here is a summary of some common approaches, and their possible advantages and disadvantages:

- The serial approach—starting with very few tracks, we listen to them in isolation and mix them first, then gradually more and more tracks are added and mixed. This divide-and-conquer approach enables us to focus well on individual elements (or stems). The danger with this approach is that as more tracks are introduced, there is less space in the mix.

- Rhythm, harmony, melody—we start by mixing the rhythm tracks in isolation (drums, beat, and bass), then other harmonic instruments (rhythm guitars, pads, and keyboards), and finally the melodic tracks (vocals and solo instruments). This method often follows what might have been the overdubbing order. It can feel a bit odd to work on drums and vocals without any harmonic backing. But arguably, from a mixing point of view, it makes little sense mixing an organ before the lead vocal.

- In order of importance—tracks are brought up and mixed in order of importance. So, for instance, a hip-hop mix might start with the beat, then lead vocals, then additional vocals, and then all the other tracks. The advantage here is that important tracks are mixed at early stages when there is still space in the mix and so they can be made bigger. The least important tracks are mixed last into a crowded mix, but there is less of a consequence in making them smaller.

- Parallel approach—this involves bringing all the faders up (of key tracks), setting a rough level balance, rough panning, and then mixing individual instruments in whatever order one desires. The advantage with such an approach is that nothing is being mixed in isolation. It can work well with small arrangements but can be problematic if many tracks are involved—it can be very hard to focus on individual elements or even make sense of the overall mix at its initial stages. As an analogy, it would be like playing football with eight balls on the pitch.

There are endless variations to each of these approaches. Some, for example, start by mixing the drums (the rhythmical spine), then progress to the vocals (most important), then craft the rest of the mix around these two important elements. Another approach, which is more likely to be taken when an electronic mix makes strong usage of the depth field, involves mixing the front instruments first, then adding the instruments panned to the back of the mix.

There are also different approaches to drum mixing. Here are a few things to consider:

- Overheads—the overheads are a form of reference for all the other drums. For example, the panning position of the snare might be dictated by its position on the overheads. Changes made to the overheads might affect other drums, so there is some advantage in mixing them first. Nonetheless, many engineers prefer to start from the kick, then progress to the snare, and only then perhaps mix the overheads. Sometimes the overheads are the last drum track to be mixed.

- Kick—being the most predominant rhythm element in most productions, the kick is often mixed before any other individual drum and sometimes even before the overheads. Following the kick, the bass might be mixed and only then other drums.

- Snare—as the second most important rhythm element in most productions, the snare is often mixed after the kick.

- Toms—as they are generally only played occasionally, they are often the least important contributors to the overall sound of the drums (and yet their effect in the mix can be vital). Some leave the toms to be mixed at a very late stage, when the core or most of the mix is already done.

- Cymbals—the hi-hats, ride, crashes, or any other cymbals might have a sufficient presence on the overheads. Often in such cases, the cymbals are used to support the overheads, or only mixed at specific sections of the song for interest’s sake. Sometimes these tracks are not mixed at all.

Which section?

With rare exceptions, the process of mixing involves working separately on the various sections. Each section is likely to involve different mixing challenges and a slightly different arrangement (choruses are commonly denser than verses). And so, mixing engineers usually loop one section, mix it, then move on to the next section and mix it based on the existing mix. The question is: Which section should be first? There are two approaches here:

- Chronologically—starting from the first section (intro) and slowly advancing to succeeding sections (verse, chorus). It seems very logical to work this way since this is the order in which music is played and recorded. However, while we might mix the verse perfectly—creating a rich and balanced mix—there will be very little place in the mix for new instruments introduced during the paramount chorus.

- In order of importance—the most important section of the song is mixed first, followed by the less important sections. For a recorded production, this section is usually the chorus; for some electronic productions, it will be the climax. Very often, the most important sections are also the busiest ones, therefore mixing them first can be beneficial.

Which treatment?

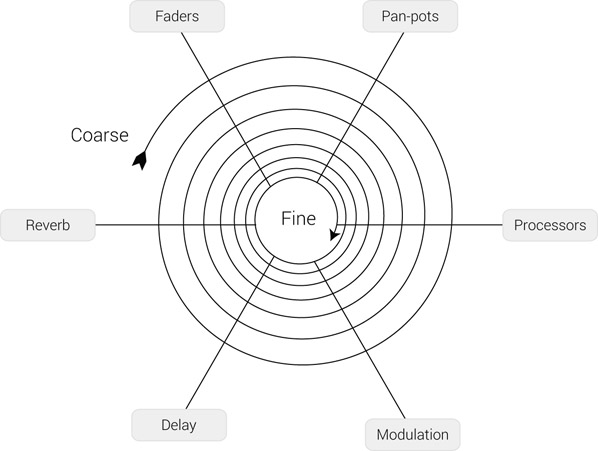

The “standard” guideline for treatment order is shown in Figure 4.4. With the exception of faders (which need to be up for sound to be heard), there is no reason to adhere to this order. Later in the book, we will encounter a few techniques that involve a different order. However, there is some logic in the standard.

Figure 4.4 The “standard” treatment order guideline.

If we skip panning and mix in mono, we lose both the width and depth dimensions. Yet, since masking is more pronounced in mono, a few engineers choose to resolve masking by equalizing while listening in mono. This might be done before panning, but more frequently done using mono summing. Since processing replaces the original sound, it comes before any effects that add to the sound (modulation, delay, or reverb). The assumption is that we would like to have the processed signal sent to the effects, rather than what might be a problematic unprocessed signal. Similarly, it is usually desirable to have a modulated sound delayed, rather than having the delays modulated. Finally, since reverb is generally a natural effect, we normally like to have it untreated; treated reverbs are considered a creative effect. In some cases, automation is the last major stage in a mix.

There is also the dry-wet approach, in which all the tracks are first mixed using dry treatment only (faders, pan pots, and processors), and only then wet treatment is applied (modulation, delay, and reverb). This way, the existing sounds are all dealt with before adding new sounds to the mix. It also leaves any depth or time manipulations (reverbs and delays) for a later stage, which can simplify the mixing process for some. However, some claim that it is very hard to get the real feel and the direction of the mix without depth or ambiance.

The iterative approach

Back in the days of two-, four-, and eight-track tape recorders, mixing was an integral part of the recording process. For example, engineers used to record drums onto six tracks, then mix and bounce them to two tracks and use the previous six tracks for additional overdubs. The only thing that limited the number of tracks to be recorded was the accumulative noise added in each bounce. Back then, engineers had to commit their mix, time and again, throughout the recording process—once bouncing took place and new material overwrote the previous tracks, there was no way to revert to the original drum tracks. Such a process required enormous forward planning from the production team— they had to mix while considering something that hadn’t been recorded yet. Diligence, imagination, and experience were key.

Today’s technology offers hundreds of tracks. Even when submix bouncing is needed (due to channel shortage on a desk or processing shortage on a DAW), the original tracks can be reloaded at later times and a new submix can be created. This practically means that everything can be altered at any stage of the mixing process, and nothing has to be committed before the final mix is printed.

Figure 4.5 The iterative coarse-to-fine mixing approach. 40

Flexibility to undo mixing decisions at any point in the mixing process is a great asset since mixing is a correlative process. The existing mix should normally be retouched to accommodate newly introduced tracks. For example, no matter how good the drums sound when mixed in isolation, the introduction of distorted guitars into the mix might require additional drum treatment (the kick might lose its attack, the cymbals might lose definition, and so forth). Plus, treatment in one area might require subsequent treatment elsewhere. For instance, when brightening the vocal by boosting the highs, high frequencies may linger on the reverb tail in an unwanted way, so the damping control on the reverb might need to be adjusted. The equalization might also make the vocal seem louder in the mix and so the fader might need to be adjusted. If the vocal is first equalized and then compressed, the compression settings might need to be altered as well.

Since mixing is such a correlative process, it can benefit from an iterative coarse-to-fine approach (Figure 4.5). This means starting with a coarse treatment on which we spend less time, then as the mix progresses continually refining previous mixing decisions. Most of the attention is given to the late mixing stages, where the subtlest changes are made. There is little justification in trying to get everything perfect before these late stages— what sounds fine at one point might not be so later.

Start with coarse and finish with fine.

Deadlocks

The evaluation block

This is probably the most common and frustrating deadlock for the novice. It involves listening to the mix and sensing that something is wrong, but not being able to specify what. Reference tracks are a true asset in these situations—they give us the opportunity to compare aspects of our mix with an established work. This comparison can reveal what is wrong with our mix, or at least point us in the right direction.

The circular deadlock

As we mix, we define and execute various tasks—from small tasks such as equalizing a shaker to big tasks such as solving masking issues or introducing ambiance. The problem is that in the process, we naturally tend to remember our most recent actions. While in the moment we might not pay any attention to a specific compression applied two days before, we might be tempted to reconsider an equalization applied an hour previously. Thus, it is possible to enter a frustrating deadlock in which recent actions are repeatedly evaluated—instead of pushing the mix forward, the mix goes around in circles. An easy way out of this stalemate situation is often a short break. We might also want to listen to the mix as whole, and re-establish a plan based on what really needs to be done.

Be mindful of reassessing recent mixing decisions.

The raw tracks factor

Life has it that sometimes the quality of the raw tracks is poor to an extent that makes them impossible to work with. For instance, distorted guitars that exhibit strong comb filtering will often take blood to fix. A common saying is: “What you can’t fix you can hide, trash, or break even more.” For example, if an electric guitar was recorded with a horrible pedal monophonic reverb that just does not fit into the mix, maybe over-equalizing it and ducking it with relation to a delayed version of the drums will yield such an unusual effect that nobody will notice the mono reverb anymore. Clearly there is a limit to how many instruments can receive such dramatic treatment so sometimes rerecording is inevitable.

In other cases, it is the arrangement that is to blame, as when the recorded tracks involve a limited frequency content or the absence of a rhythmical backbone. Again, there is nothing to stop the mixing engineer from adding new sounds, or even rerecording instruments; nothing, apart from time availability and ability.

What you can’t fix you can hide, trash, or break even more.

Milestones

The mixing process can have many milestones. On the macro-level, there are a few that are potentially key (Figure 4.6). The first involves bringing the mix into an adequate state. Once this milestone is reached, the mix is expected to be free of any issues—whether they existed on the raw tracks or were introduced during the actual process of mixing. Such problems can range from basic issues such as relative levels (e.g., solo guitar too quiet) to more advanced concepts such as untidy ambiance.

Nevertheless, a problem-free mix is not necessarily a good one. The next milestone is making the mix distinctive. The definition of a distinctive mix is abstract and varies between one mix and another, but the general objective is to make the mix notable— memorable—whether by means of interest, power, feel, or any other sonic property.

Figure 4.6 Possible milestones in the mixing process.

The final milestone, which often only applies to the inexperienced engineer, is stabilizing the mix. This step is discussed in detail in the next section.

Finalizing and stabilizing the mix

All the decisions we make while mixing are based on the evaluation of what we hear at the listening position, otherwise known as the sweet spot. But mixes can sound radically different once one leaves this sweet spot. Here are some prime examples:

- Different speakers reproduce mixes differently—each speaker model (sometimes in combination with its amplifier) has its own frequency response, which also affects perceived loudness. While listening on a different set of speakers, the vocals might not sound as loud and the hi-hats might sound harsh. Different monitor positions also affect the overall sound of the mix, mainly with relation to aspects such as stereo image and depth.

- Mixes sound different in different rooms—each room has its own sonic stamp that affects the music played within it. Frequency response, which is affected by both room modes and comb filtering, is the most notable factor, but the room response (reverberation) also plays a part.

- Mixes sound different in different points in a room—both room modes and comb filtering alter our frequency perception as we move around the room. A mix will sound different when we stand next to the wall and when we are in the middle of the room. (This issue is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 8.)

- Mixes sound different at different playback levels—as per our discussion on equal-loudness curves.

Many people are familiar with the situation where their mix sounds great in their home studio but translates badly when played in their car. It would be impossible to have a mix sounding the same in different listening environments for the reasons explained above. This is worth repeating: mixes do sound very different in different places. What we can do is ensure that our mixes are problem-free in other listening environments. This is much the idea behind stabilizing the mix.

The reason that it is usually the novice that has to go through this practice is that the veteran mixing engineer knows his or her mixing environment so well that he or she can predict how well the mix will sound in other places. Also, in comparison to a professional studio, the sweet spot in a home studio is actually quite sour. Acoustic problems in home studios can be very profound, while in a professional studio these are rectified by expensive construction and acoustic design, carried out by experts.

The process of stabilizing the mix involves listening to the mix in different locations, different points within those locations, and at varying levels. Based on what we observe, we can finalize the mix by fine-tuning some of its aspects. Normally, this involves subtle level and equalization adjustments. Here is how and where mixes should be listened to during the stabilizing phase:

- Quiet levels—the quieter the level, the less prominent the room and any deficiencies it exhibits become. Listening quietly also alters the perceived loudness of the lows and highs, and it is always a good sign if the relative level balance in the mix hardly changes as the mix is played at different levels. Listening at loud levels is also an option, but can be misleading as mixes usually sound better when played louder.

- At the room opening—also known as “outside the door.” Many find this listening position highly useful. When listening at its opening, the room becomes the sound source, and instead of listening to highly directional sound coming from the (relatively) small speakers we listen to reflections that come from many points in the room. This reduces many acoustic problems caused by the room itself. The monophonic nature of this position can also be an advantage.

- Car stereo—a car is a small, relatively dry listening environment that many people find useful. In the same way as the room-opening position, the car provides a very different acoustic environment that can reveal problems.

- Headphones—with the growing popularity of MP3 players comes the growing importance of checking mixes using headphones. With the use of headphones, we will sacrifice some aspects of stereo image and depth but not have to worry about room modes, acoustic comb filtering, and left/right phase issues. We can regard listening via headphones as listening to the two channels in isolation, and it is a known fact that headphones can reveal noises, clicks, or other types of problems that may not be as noticeable when the mix is played through speakers. The main issue with headphones is that most of them have an extremely uneven frequency response, with strong highs and weak lows. Therefore, most are not regarded as a critical listening tool.

- Specific points in the room—many home studios present poor acoustics, and very often there are issues at the sweet spot. Moving out of this spot can result in an extended bass response and many other level or frequency revelations. Also, the level balance of the mix changes as we move off-axis and out of the monitors’ close range. Beyond a certain point (the critical distance), the room’s combined reflections become louder than the direct sound—most end listeners will listen to mixes under such conditions, so it is important to hear what happens away from the sweet spot.

Evaluating the mix using any of these methods can be misleading if caution is not exercised. While listening in a specific point in a room, it might seem that the bass disappears and subsequently we might be tempted to boost it in the mix. But there is a chance that it is that point in the room causing the bass deficiency, while the mix itself is fine. How, then, can we trust what we hear in any of these places? The answer is that we should focus on specific places and learn the characteristics of each. Usually, rather than going to random points, people evaluate mixes in the exact same point of the room every time. In addition, playing a familiar reference track to see how it sounds in each of these places is a great way to learn the sonic nature of each location.

While listening to the mix in different places, it would be wise to make a note of what issues you notice and which require further attention, and then go back to the mixing board. In some cases, comments cancel one another out. For example, if while using headphones it seems that the cymbals are too harsh but when listening at the room opening they sound dull, perhaps nothing should be adjusted.

As a final piece of advice, it should be mentioned that listening in different locations is not reserved for final mix stabilization—it can also be beneficial at other stages of the mixing process, especially when decisions seem hard to make.