CHAPTER 5

The Volatility Risk Premium

Over the long run, options cost more than they are worth. Period. Academics have studied the how much and the when to death, but the what is pretty much a given. Options, as measured by implied volatility, cost more than they are ultimately worth, as measured by realized volatility. The difference is the volatility risk premium.

Intuitively, this makes tremendous sense in part because option payoffs are hugely asymmetrical. Option buyers have a relatively small risk, the price paid for the option, and have a theoretically gigantic potential return; if they’ve bought a call option then the potential return is essentially infinite. On the other hand, option sellers have a relatively small potential return, the amount received for selling the option, and a theoretically gigantic potential risk; if they’ve sold a call option then the potential risk is essentially infinite. We’d expect the option sellers to make some profit to compensate for this asymmetry, and most people wouldn’t begrudge them a reasonable one. But what is a reasonable profit? Why don’t some who are willing to reap a smaller profit sell down option prices? Why does this volatility risk premium continue to exist, and is there an empirical reason that it is what it is?

VOLATILITY RISK PREMIUM, THE WHAT

For option buyers, implied volatility is what they pay. For option buyers the realized volatility is what they actually get. The volatility risk premium is the difference between the two—the volatility risk premium is generally considered to be implied volatility minus realized volatility.

As we’ve seen, the real value of an option isn’t how much it’s in-the-money at expiration, it’s how bumpy the path to expiration was. Even if we think an option will expire worthless, we can use the bumpiness of the path the underlying takes to get to the expiration date. The result is that we can “extract” the realized volatility of the underlying through this trading.

If the path ends up being very bumpy then option buyers have gotten a lot from their option. Professional traders or market maker have gotten a lot because they were able to extract money through this bumpiness by trading the underlying against their position. What if you’re not a professional? Even if we don’t take advantage of that bumpiness by trading the underlying, then we’ve gotten lots of value from our option. Maybe we’ve gotten a lot because we had the luxury of waiting, the luxury of being able to make a more informed decision. We didn’t have to confront every meteoric rise and sickening gap in the underlying price. Maybe it was simply being able to stand aside confidently, knowing that we had protected the value of our underlying thanks to owning a put option. Maybe it was simply knowing that we had bought time, that we could wait to make a decision on expiration day. As we’ve discussed, all those sound like things that someone would be willing to pay extra for.

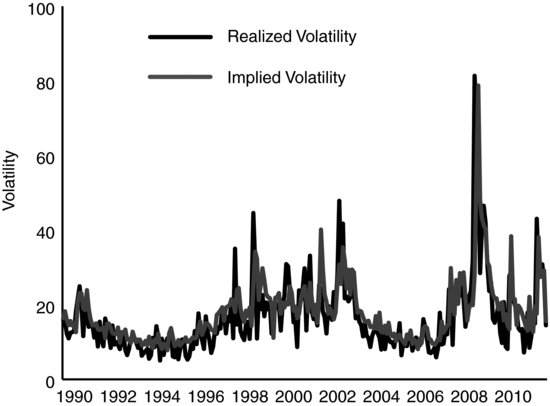

Figure 5.1 shows just how much extra option buyers have been willing to pay for SPX options over time. The darker line represents implied volatility, which is the cost, for the first out-of-the-money, 30-day-to-expiration call option. The lighter line shows the realized volatility, which is the value of that option, for the S&P 500 over the same periods.

FIGURE 5.1 SPX Implied and Realized Volatility

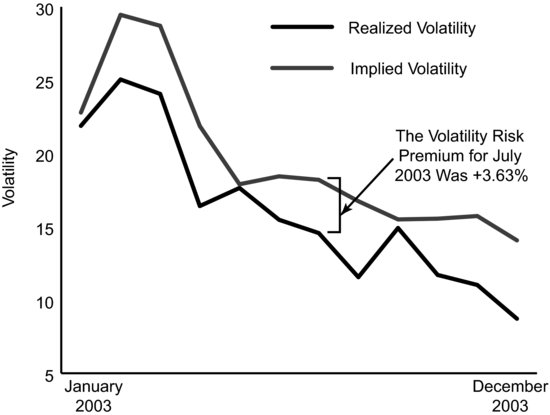

Figure 5.2 shows the same information, the implied volatility and realized volatility, for just 2003. In Figure 5.2 it’s easier to recognize the difference between the two volatilities.

FIGURE 5.2 SPX Implied and Realized Volatility for 2003

In Figure 5.2 you can see that implied volatility was consistently higher than the ultimate realized volatility. This difference was the volatility risk premium and it would have compensated option sellers for the asymmetry in their risk and reward. For example, in July 2003, the 30-day at-the-money SPX call option had an implied volatility of 18.21 percent. Over the next 30 days the realized volatility of the S&P 500 Index was just 14.58 percent, a volatility risk premium of 3.63 percent.

If implied volatility, an option’s price, is generally higher than the ultimate realized volatility, an option’s value, why wouldn’t a steely-eyed option professional say, “I don’t care about peace of mind, much like a casino executive doesn’t care about someone winning an occasional big jackpot at the slot machines. I’m willing to forgo peace of mind for money if I know that over time I’m selling something for more than it’s worth.” The result would be selling down the implied volatility so that it’s just fractionally above realized volatility. Think of a Walmart for options. A systematic option seller could extract the realized volatility by trading the underlying and pocket the very small difference over time and grow wealthy. The realized volatility can’t be over the implied volatility by very much, can it? Don’t they tend to track each other?

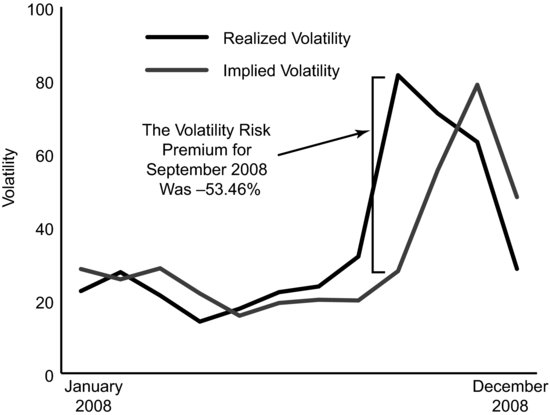

One answer is that realized volatility, the ultimate value of the option, can be over implied volatility, the cost of the option, by a huge amount. That huge amount can be staggering, physically and financially, for the trader who blindly and constantly sells options. The volatility risk premium is something to be used carefully. If we look at the same underlying (SPX) in 2008 we see in Figure 5.3 that in September of that year the realized volatility was 81.39 percent while the implied volatility had been only 27.93 percent at the start of the period. The realized volatility ended up being at least 5,346 basis points higher than expected. We might have expected it to correct the next month because option sellers might have dramatically increased the price they demanded for options. In fact, they did just that. In October they demanded an implied volatility of 55.44 percent, almost double the previous month’s price. It still wasn’t enough. Realized volatility that period ended up being 70.97 percent. A volatility seller for either of those two periods would have been punished by the volatility risk premium.

FIGURE 5.3 SPX Implied and Realized Volatility for 2008

THE ASSUMPTIONS, THE WHY OF THE VOLATILITY RISK PREMIUM

A skeptic has to ask—and every good trader needs to be a little skeptical, whether it’s being skeptical of conventional wisdom or of the opinion of the crowd—is implied volatility really higher than realized volatility? We calculate the implied volatility of an option by plugging the option price and other specifics (expiration, strike price, etc.) into a model that generates an implied volatility. It’s easy to forget while doing the option math the following caveat: Implied volatility is subject to all the assumptions inherent in that particular option model.

Several of the phenomena that we discuss in this book (and which option traders can take advantage of, including the volatility risk premium), exist partly because the assumptions inherent in theoretical option pricing models simply don’t hold in the real world. Option models make these assumptions because the problem of pricing an option would simply be unmanageable otherwise.

One of the assumptions is that the prices of the underlying are continuous, meaning that there are no jumps or gaps and there is no bid/ask spread in the stock price. This assumption exists because option pricing models assume volatility can be captured through hedging. Just as there are an infinite number of paths for volatility and interest rates, there are an infinite number of paths for the underlying. Instead of saying the stock price is unchanged (like we assume for volatility and interest rates) defeating the need for options at all, by saying that the stock prices are continuous (meaning constantly tradable at every price, in any quantity, even as prices change), hedging in microscopic amounts at each and every price is possible; we have eliminated one variable and are now able to construct our model.

However, anyone who’s watched the real-time prices of a stock immediately after an earnings report knows that this assumption is fundamentally at odds with the real world. The price often jumps several percent without trading even once. Then it’s likely to bounce about in a wide range with significant gaps in trading.

This is the actual course of the first five trades in one U.S. stock immediately after an earnings announcement (data from NationsShares).

This market is clearly not continuous, and the assumption that it is continuous is flawed.

Black-Scholes, in fact all option pricing models, would have assumed that a trader trying to capture realized volatility would have been able to offset his option position by selling a little of this stock at $30.27, then a little more at $30.26, and a little more at $30.25, selling a little at each price all the way down to $29.85. Oh, if it were only that easy.

Hence, even for the smartest, best-equipped professional, it isn’t possible to capture the realized volatility by trading in the underlying to the degree imagined by the model.

The volatility risk premium acknowledges this real-world inability to capture the realized volatility.

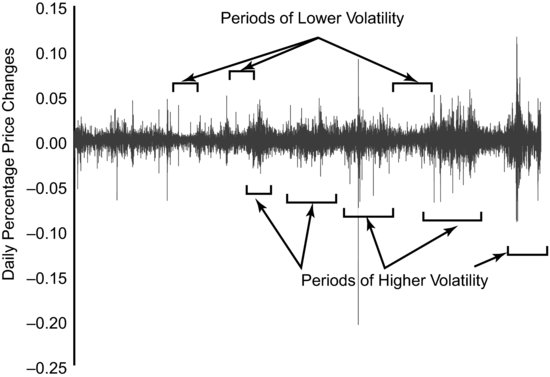

Another related and commonly violated assumption is that volatility is constant for the life of an option. This is simply not so. Volatility is lumpy (the technical term is heteroskedastic) meaning that periods of higher than average volatility, such as the period immediately following an earnings announcement or a period of geopolitical turmoil for stock indexes, are followed by periods of lower than average volatility. These periods may last days or weeks. Figure 5.4 shows realized volatility for the S&P 500 from 1955 to 2011. It’s clear that there are clumps representing periods when realized volatility was high, and there are troughs representing periods when realized volatility was low.

FIGURE 5.4 Heteroskedasticity

The violation of these assumptions means the cost for someone trying to capture the realized volatility is higher than an option model would predict. If all of the assumptions held, then the option seller could extract the realized volatility from the underlying, as we’ve discussed, and the profit or loss would be solely determined by how good a guess of realized volatility the implied volatility of our option was. As it is, option sellers have to worry about that guess, about hedging out the realized volatility (in the face of jumps in both stock price and volatility), about interest rates changing, about the dividend stream, and about the cost of doing business. As a result, option sellers will add a margin of error to their best guess of an option’s ultimate value. To this they add a little bit more for profit. This becomes the implied volatility seen in the market. Therefore, think of the volatility risk premium as the margin of error and the profit for the option seller. Just as a homeowner’s insurance company charges slightly more than the coverage is worth—that slight difference covers their overhead and is the source of profit—option sellers demand slightly more than options are ultimately going to be worth.

THE VOLATILITY RISK PREMIUM—HOW MUCH

The volatility risk premium for any particular underlying is an incredibly elusive moving target. It might exist for a period of time and then disappear unexpectedly. It will expand and contract, ebb and flow. For some periods for some assets it will be negative. It will be negative because the realized volatility will end up being higher than was predicted by implied volatility. In this case the option buyer got a bargain; they got more than they paid for.

The volatility risk premium is a little like an abstract painting: Only when we step back to look at it from a distance, in our case the distance of time, does the form and magnitude become apparent.

SPX options on the S&P 500 Index show a profound volatility risk premium but the size becomes most apparent when viewed over a long time period. For example, Table 5.1 shows the volatility risk premium for the SPX 30-day at-the-money (ATM) call from December 1989 to December 2011.

Table 5.1 Volatility Risk Premium for the SPX 30-Day ATM Call

| Average Implied Volatility | 25.37% | |

| Average Ultimate Realized Volatility of S&P 500 Index | 16.44% | |

| Average Cost of Option as Percentage of the Index | 1.890% | |

| Average Value of the Option as Percentage of the Index | 1.726% | |

| Average Difference Between Cost and Value | 0.164% | |

| Average Dollar Difference | $1.26 | |

| Source: NationsShares | ||

This is an apples-to-apples comparison because the ultimate realized volatility was calculated over the exact same time period as the implied volatility.

As we’ve seen in Chapter 1, the time value of an option is greatest when the option is at-the-money. Does that mean that the volatility risk premium is greatest for an at-the-money option? See Table 5.2 for the volatility risk premium for the SPX 30-day 5-percent out-of-the-money (OTM) put.

Table 5.2 Volatility Risk Premium for the SPX 30-Day 5% OTM Put

| Average Implied Volatility | 25.37% | |

| Average Ultimate Realized Volatility of S&P 500 Index | 16.44% | |

| Average Cost of Option as Percentage of the Index | 0.785% | |

| Average Value of the Option as Percentage of the Index | 0.498% | |

| Average Difference between Cost and Value | 0.287% | |

| Average Dollar Difference | $2.87 | |

| Source: NationsShares | ||

Time value is greatest at-the-money, but that’s not necessarily where the greatest volatility risk premium, at least in volatility terms, will be found. In fact, the greatest volatility risk premium, in volatility terms, is closely related to the concept of skew, which we’ll discuss in Chapter 6. This means that it might be in at-the-money options, it might be in out-of-the-money puts (generally the case for equity index options), it might be in calls (generally the case for commodities), or it might not exist for a period.

HOW TO THINK ABOUT THE VOLATILITY RISK PREMIUM

The volatility risk premium is compensation for option sellers taking additional risk (risk that is asymmetrical), and for the fact that the assumptions inherent in an option model don’t hold. It’s the price option buyers pay to achieve the following objectives:

- Define risk and free themselves from the vagaries of option pricing models

- Generate leverage

- Protect their investment

- Reduce the volatility of a portfolio

Option buyers thus free themselves from worry about our world when it contradicts the assumptions of option pricing models.

THE VOLATILITY RISK PREMIUM BY ASSET CLASS

The general size of the volatility risk premium, its location (at-the-money, or below or above at-the-money levels), and its persistence varies by asset class. This makes sense as certain commodities (e.g., crude oil) tend to gap higher when unforeseen events occur unlike equity indexes that tend to gap lower; crude oil’s tendency to gap higher may mean that upside calls display the greatest volatility risk premium. This is closely related to skew, a term discussed in Chapter 6. For an individual equity, gaps and jumps are likely in either direction so the greatest volatility risk premium, in dollar terms, is usually at-the-money but if puts get really expensive due to bad news or if calls get really expensive due to takeover talk then the volatility risk premium for an individual equity can shift from at-the-money. Tables 5.3, 5.4, and 5.5 show the volatility risk premium for several asset classes over a recent two-year period.

Table 5.3 Volatility Risk Premium for USO (Crude Oil)

| Average Implied Volatility | 33.33% |

| Average Realized Volatility | 29.38% |

| Average Volatility Risk Premium (I.V. minus R.V.) | 3.95% |

| Highest Volatility Risk Premium (I.V. minus R.V.) | 18.53% |

| Lowest Volatility Risk Premium (I.V. minus R.V.) | −14.43% |

Table 5.4 Volatility Risk Premium for GOOG (Google Inc.)

| Average Implied Volatility | 28.81% |

| Average Realized Volatility | 27.82% |

| Average Volatility Risk Premium (I.V. minus R.V.) | 0.99% |

| Highest Volatility Risk Premium (I.V. minus R.V.) | 20.55% |

| Lowest Volatility Risk Premium (I.V. minus R.V.) | −21.21% |

Table 5.5 Volatility Risk Premium for TLT (U.S. Treasury Bond ETF)

| Average Implied Volatility | 16.69% |

| Average Realized Volatility | 17.10% |

| Average Volatility Risk Premium (I.V. minus R.V.) | −0.41% |

| Highest Volatility Risk Premium (I.V. minus R.V.) | 8.29% |

| Lowest Volatility Risk Premium (I.V. minus R.V.) | −18.82% |

If you’d been short options for United States Oil (a crude oil ETF, ticker symbol USO) during this period and used the underlying to capture the realized volatility, you’d likely have made money because the volatility risk premium was strongly positive, particularly as a percentage of implied volatility. However, there was at least one month that would have been a sickening ride. That’s the month when implied volatility at the start of the month predicted movement for that month translating to an annualized volatility of 31.01 percent, only to see the realized volatility for that month to turn out to be 45.44 percent.

If you’d been short Google Inc. (GOOG) options during this period and used the underlying to capture the realized volatility, you’d likely have made money because the volatility risk premium was positive. However, there was a two-month period that would have left a volatility seller pretty queasy. It started with the month when implied volatility was below the ultimate realized volatility by 21.21 percent, which was followed up by a month that saw realized volatility come in 19.85 percent higher than implied volatility had been at the start of the month. Be prepared. This is the sort of price action that can lead to a trader swearing off short option positions forever.

If you’d been short Barclays 20+ Year U.S. Treasury Bond Exchange Traded Fund (TLT) options during this period and used the underlying to capture the realized volatility, you’d likely have lost money. It’s unusual for the volatility risk premium to be negative over such a long period, but the market can stay volatile longer than people think and longer than option sellers can stay solvent. The largest volatility risk premium of 8.29 percent occurred in a month when implied volatility was 25.73 percent at the start of the month and realized volatility ended up being only 17.44 percent. However, that month wouldn’t have made up for either of the two worst months.

THE VOLATILITY RISK PREMIUM OVER TIME

Nothing about option trading is fixed. Realized volatility changes constantly. Implied volatility does as well. The participants’ appetite for risk increases and decreases. Similarly, the volatility risk premium isn’t static. It expands and contracts, and for long periods it can be negative, meaning that realized volatility is higher than implied option volatility.

Over time, the volatility risk premium is self-correcting, meaning that ultimately, if realized volatility is higher than implied for a long-enough period, traders will stop selling options at those implied volatilities. Instead, they’ll adjust the price of options (and hence the volatility implied by those prices) higher, until they think implied volatility is now high enough to cover their expenses (realized volatility being the most important expense, but also including the margin of error to account for the failure of assumptions in option pricing models plus profit). In fact, option sellers are always trying to sell options so that the implied volatility is higher than realized volatility is going to be. Sometimes they’re just wrong.

Likewise, if implied volatility is too high relative to realized volatility, then traders will be more willing to sell options and get short implied volatility at those levels. In fact, additional participants may enter the market for those options and do so by selling.

Just as someone can enter the home insurance market and drive down the price of insurance and profit margins (we assume claims wouldn’t change) for home insurers—until the point where the next potential insurer realizes they’d drive prices down such that the profit isn’t worth the trouble and risk—additional potential option sellers may think that the volatility risk premium isn’t high enough to compensate for the effort and risk. Thus the volatility risk premium is much like anything else; it’s subject to supply and demand. If more hedgers are willing to pay a higher volatility risk premium, then the volatility risk premium will increase. Option prices may be too high, but the result is that over time they’re generally as low as they’re going to get unless additional option sellers enter the market or the realized volatility regime changes substantially and for a significant period.

This is why having the volatility risk premium working on your behalf as an option seller is a little like having the odds on your side at a casino. Over the long run and assuming enough discrete chances, you’ll come out ahead. That doesn’t mean that in the short run you won’t lose, and that some of those losses won’t be pretty sickening.

- Over time, the volatility risk premium is positive, meaning that implied volatility (the cost of options) is greater than realized volatility (the value of options).

- The volatility risk premium exists in part due to the failure of assumptions in option models, and in part due to demand from option buyers seeking protection or the asymmetry of option returns. The volatility risk premium is also the compensation demanded by option sellers for their willingness to face the asymmetry of option returns.

- The volatility risk premium exists in options on every asset class but not in any asset all the time.

- The volatility risk premium is self-correcting. If it disappears then option buyers will be willing to pay more for options, and option sellers will demand more for options, which will drive option prices (implied volatility) higher while having no impact on option values (realized volatility).

- Being very wrong about the volatility risk premium, that is, being short implied volatility when realized volatility is much higher, can lead to sickening results.

- The way to collect the volatility risk premium is to be short options, but every option seller should use the volatility risk premium sensibly.