CHAPTER 11

Selling Puts

Selling puts can be a great strategy: It collects premium and offers the potential to buy stock at a discount. Selling a put takes advantage of several of the phenomena we discussed in Part Two, mainly the volatility risk premium, and since we’ll sell short-dated options, it will take maximum advantage of time decay.

As we discuss selling puts, it won’t be for speculation and it won’t be levered; rather it will be fully funded, meaning the put seller will have the cash set aside to pay for the stock if it’s put to him.

Almost every trader has entered a limit order to buy stock. It’s a great way to buy stock at a discount, at a price that’s more palatable then the current market price, which may have simply been too expensive. One of the problems with a limit order to buy stock is obviously the potential to never buy the stock and see it appreciate substantially.

The same problem exists for the option trader when selling puts with the added wrinkle that the stock has to be below our limit price (i.e., the put option strike price) at option expiration—so timing is an issue as well. If we’ve entered a limit order to buy shares then if the stock is below that limit price, for a month or a minute, we’re going to get our buy order filled. When selling puts to buy stock it’s not the amount of time the stock is below our strike price, it’s when that occurs. It has to occur at expiration.

While this is a deterrent to selling puts if a trader’s sole goal is to buy stock, by selling puts we’re paid to wait to buy the stock and we’re often paid very handsomely. Think of selling puts as a way to get paid for waiting to see our buy order filled, although it’s entirely possible that we’ll wait until expiration and never get filled.

In selling puts, we agree to buy the underlying stock at the strike price if the put option buyer exercises their option. We’ll be paid the option premium for agreeing to do so. The maximum profit is that premium received. The breakeven point is the strike price minus the premium received. The maximum loss occurs if the stock goes to zero at expiration. Figure 11.1 shows the typical risk and reward for a short put at expiration.

FIGURE 11.1 Short Put Risk and Reward

SELLING PUTS IS BEST FOR STOCKS YOU WANT TO OWN AT A DISCOUNT

Selling puts to buy stock that you want to own at a discount is a wonderful strategy for great stocks that you think aren’t likely to fall or appreciate significantly during the term of the option. If you thought that the stock was going to fall, you certainly wouldn’t sell a put. In that situation you’d be better off buying a put. If you thought the stock was going to appreciate sharply, selling puts isn’t the optimal strategy. In that situation you’d be better off buying call options or buying the stock outright. However, on some occasions great stocks get stuck in neutral.

Selling puts should only be done on great “names” that you want to own at a discount. Don’t get into the habit of selling expensive puts on bad stocks just because the options are expensive and you think you’d be willing to buy anything at a 15 percent discount. When that bad stock falls, as they tend to do, you might end up buying something you don’t like at an effective price higher than its current market price. The discount from the initial price isn’t so attractive now, since you own a bad stock at a higher price. In that instance you should be looking to puke it (sell it at a loss) just as soon as you get it put to you.

Selling puts should be done on stocks that you don’t currently own or on stocks that you’d like to own more of. Be careful in this second case. It potentially violates a cardinal rule of trading by adding to a loser, and getting long more stock through a put sale generally means the stock is at least slightly lower than it was.

We’ll always consider selling puts as a great way to buy stock at a discount. As such you’ll always have the cash ready to go in order to buy the stock, and it will preferably be in the same account you’re selling the put option in. Don’t sell naked puts, that is, don’t plan to rely on margin to buy the stock if it gets put to you. We’re getting paid to wait to buy the stock, not to dodge a bullet.

As in a covered call, we get to keep the premium received whether the put option we’re short gets assigned, meaning the stock is put to us and we’re required to buy it at the strike price, or not. Keeping this premium means that we might buy the stock at an effective price (strike price minus premium received) lower than the stock ever traded.

When selling puts to buy stock at a discount, or to at least get paid for trying to, there are four possible outcomes, as shown in Table 11.1. One is good, one is less good, one is great, and one is less bad.

Table 11.1 Relative Outcome from Selling Puts

| Relative | ||

| Stock Price Action | Position Result | Outcome |

| Stock Rallies Slightly | Keep Premium, Don’t Buy Stock, Gain Greater Than Buying Stock | Good |

| Stock Rallies Sharply | Keep Premium, Don’t Buy Stock, Regret Not Buying Stock | Less Good |

| Stock Falls Slightly | Keep Premium, Don’t Buy Stock, Maximum Profit Achieved | Great |

| Stock Falls Sharply | Keep Premium, Buy Stock, Premium Cushions Loss | Less Bad |

Having the stock rally slightly means we get to keep the premium received for selling the put, and since the stock is near its original price, we’re money ahead.

If the stock rallies sharply the outcome is good, we get to keep the premium received, but it’s less good than simply buying the stock would have been.

The stock falling slightly is the best possible outcome assuming it stays above the strike price. This is because the put will expire worthless and the put seller will get to keep the premium received, but the stock we like will cost slightly less than it did. The next trade can be to sell the same strike price in the next expiration and probably receive more in premium than the initial put sale, or to sell a lower strike put while collecting a reasonable amount of premium.

Having the stock fall sharply, enough so that it’s below the strike price, is less bad than simply buying the stock would have been. The effective purchase price will certainly be lower than the market price for the stock when we sold the put. The current stock price may be below our effect purchase price, meaning we’re facing a loss, which is bad, but it will be a smaller loss than if we’d just bought the stock outright.

THE PHENOMENA

Of all the phenomena we discussed in Part Two, the volatility risk premium is the most important for selling puts. Over time, put sellers are receiving more (implied volatility) than they’re giving (realized volatility). It’s this excess that generates additional return and can make selling puts superior to simply buying stocks on the offer price. Table 11.2 shows the volatility risk premium for some S&P put options going back to 1989. These are the SPX options we discussed in Part Two.

Table 11.2 Volatility Risk Premium for SPX Put Options

The difference in volatility risk premium for the two puts is a result of skew. Out-of-the-money put options tend to be relatively more expensive than at-the-money options due to hedgers buying out-of-the-money puts as we discussed in Part Two. Skew can help a put sale at initiation; it obviously helps the seller of that 5 percent out-of-the-money SPX put option. Skew is likely to be less obvious and less steep in individual equities. You can use the implied volatility calculator at OptionMath.com to calculate the implied volatilities for the puts you’re considering selling.

Time decay is the way put sellers collect their premium. Since daily time decay is greater for short-dated options, those are the put options that a put seller should focus on. As we saw in Part Two, the put seller is better off selling a series of three 30-day put options rather than selling a single 90-day option. The accelerating time decay from short-term puts is a great way to get the option math working in your favor.

The bid/ask spread can make very little difference in the profitability of very liquid options with tight bid/ask spreads. Again, in this case, it generally makes sense to simply sell the put option at the bid. The tiny amount of edge (the difference between the option’s fair value and the realized selling price) given up isn’t likely to impact the outcome of the trade. When bid/ask spreads are wide but the options are fairly active and liquid, getting the put sale executed at a reasonable price can be more difficult. The midpoint of the bid/ask spread is a reasonable proxy for fair value, but that doesn’t mean the market will want to buy your put there. Illiquid options, which almost always have wide bid/ask spreads, are an opportunity to use the spread to your advantage. The fair value is likely to be closer to the bid than the offer, and this is an opportunity to offer your put for sale at higher than fair value by offering it for sale at the midpoint of the bid/ask. If a market maker needs to buy options to offset some he has already sold, then he’s likely to buy your offer. The guide to execution of covered calls in Chapter 10 applies to selling puts as well.

Volatility slope can help in closing out the trade early if the stock moves higher. If that happens the volatility slope will bring implied volatility, and option prices, down for all strike prices. Volatility slope can make closing out the trade early more difficult if the stock moves lower. All implied volatilities will increase, so delta (the increase in the put price as the underlying price falls), as well as vega (the increase in the put price as implied volatility increases), both work against the put seller.

SELLING PUTS IS IDENTICAL TO A BUYWRITE

Observant readers will have noticed that selling a put results in a position that seems a lot like the hybrid position that resulted from selling a covered call. The payoff chart for a short put, Figure 11.1, looks very similar to the covered call hybrid charts we saw in Chapter 10. The outcome for a short put is affected by the same phenomena, which tend to have the same sort of impact. While we sold covered calls on stock we already owned, if we made it a point to buy stock just so we could sell covered calls on it, the similarities would be even more striking.

That’s because selling a put and doing a buywrite (simultaneously buying stock and selling covered calls) are identical positions. Assuming the strike price and expiration date of the put and covered call are the same, the maximum potential profit is the same, the maximum potential loss is the same, and the breakeven and regret points are the same.

SELLING PUTS TO BUY STOCK AT A DISCOUNT

Selling puts is a great way to collect premium while waiting to buy a good stock at a discount if it drops. One risk is that the stock will rally and we’ll never get ownership. Another risk is that we’re forced to buy the stock (i.e., we have it put to us) when the stock has dropped substantially such that it’s well below our breakeven point. The put seller has to be ready and able to buy the stock, but should think it’s stuck in neutral for a while.

Table 11.3 shows some SPY puts we might consider selling in order to buy SPY at a discount.

Table 11.3 Selling Puts to Buy SPY at a Discount

The breakeven point is similar to the one we discussed in selling covered calls. If the underlying stock is below this point at expiration, then we’ll have been better off not having sold the put option. We will have lost money. The regret point is also similar to that discussed in the covered call chapter. Above this regret point we would have been better off simply buying the stock.

At the regret point the stock is above the strike price of our put option at expiration, so the owner of the put option won’t exercise and the put seller won’t buy the stock. The premium received is now equal to the profit we would have enjoyed from buying the stock. Above this point we regret not buying the stock outright.

The put seller should always look at shorter-term options like these 30-day options since longer-term options don’t erode as quickly. If we sold the 130 strike put we’d likely sell it at $0.35. That’s a 0.25 percent yield for the 30 days, or about 3.00 percent annualized. If we sold the 140 strike put we’d likely sell it at $1.99. That’s a 1.4 percent yield, or about 17 percent annualized. The 150 strike put is a little different. Since it’s in-the-money we can’t calculate the yield in the traditional way because so much of its value is inherent. If we sold the 150 put at the midpoint of the bid/ask spread, the time value would be 0.04 and the additional yield would be very small, about 0.025 percent monthly or about 0.3 percent annually.

We know that a put seller is trying to capture the volatility risk premium and will be paid through the daily erosion but the goal of selling a put option is to buy a stock at a discount and to get paid for waiting to see if we get filled. What is the likelihood that these SPY options will be exercised meaning that we buy SPY at the strike price? That would be the delta of each option. How much would we be paid today for waiting to see if we get our order filled to buy SPY? That would be the daily erosion (theta) for each option. Table 11.4 details each of these variables.

Table 11.4 Selling Puts and the Greeks

At-the-Money

The at-the-money put (in the SPY example it’s the 140 put), will always have the greatest amount of time value, as we saw in Part Two. As such, it will also have the highest daily time decay.

The at-the-money put will also have a so-called fair implied volatility, meaning that skew will have little impact on the price of the option. Since the at-the-money put is likely to actually be somewhat out-of-the-money (as the SPY 140 put is in this example), there may be a tiny bit of skew included in the implied volatility, but this effect will be very minor.

If there’s a problem with selling the at-the-money put, it’s that actually buying the stock usually occurs less than 50 percent of the time. This likelihood is the delta we discussed in Part Two. For the SPY 140 put the delta was about 46, meaning there’s about a 46 percent chance of being in-the-money at expiration. If this likelihood isn’t sufficient for the trader considering a put sale, then this isn’t the best strategy—although selling a slightly in-the-money put is also a possibility, since the time value of that option is likely to be close to that of the at-the-money option. In this SPY example the in-the-money put would be the 141 put, which was trading at $2.42. The inherent value is about $0.60 and the time value is $1.82 versus time value for the 140 put of $1.99. The delta of the 141 put was 54, meaning there was a 54 percent chance it would be in-the-money at expiration. Moving to more in-the-money options will increase the likelihood of being in-the-money at expiration but will do so at the cost of time value, which will decrease fairly quickly.

In-the-Money

An in-the-money put will have a strike price that is above the current market price for the underlying stock. The implied volatility for an in-the-money put will generally be lower than for the at-the-money or out-of-the-money puts, meaning that they are relatively less expensive (although in absolute terms they’ll be more expensive due to the inherent value) and will have relatively less time value; time value is what the put seller wants more of. Selling the in-the-money put can drastically increase the likelihood of buying the stock: In the SPY example the delta of the 150 strike put was 97, meaning there’s a 97 percent chance of it being in-the-money at expiration. However, the bid price for this option is actually below parity. With SPY at $140.40/$140.41, the 150 put should be worth at least $9.60 but the issues surrounding the bid/ask spread for deeply in-the-money options discussed in Part Two result in a bid price lower than $9.60. Selling this 150 put option at $9.50 may be a lot like just buying SPY shares outright, but it’s a lot like paying $140.50 for them.

Even if we would sell the midpoint of the $9.50 bid/$9.78 ask for the 150 put ($9.64) we’re only collecting $0.04 of time value. We’re not being paid very much to wait. In-the-money puts aren’t usually a great sale and skew is a big reason why.

Out-of-the-Money

Selling out-of-the-money puts offers the best (lowest) effective purchase price, but the likelihood of actually getting the stock bought is pretty small. In the SPY example the effective purchase price (if we sold that 130 put) would be $129.65 ($130 – $0.35) but the 130 put has a delta of 9, meaning the likelihood of actually having the stock put to you is only 9 percent. Add the fact that the premium received is only $0.35, and the fact that we’re tying up the capital needed to pay for the stock if it’s put to us, and the yield from selling that put is only about 3.2 percent annually. That’s not terrible, but there’s the potential for loss if SPY is below the breakeven point at option expiration. Since so little premium is generated, the difference between the strike price and the breakeven point is very small. If we get the stock put to us it’s likely to be below the breakeven price, and our put sale would be facing a loss. Clearly selling deep out-of-the-money puts faces some problems. Remember also that an out-of-the-money option may have seen the majority of its time value already eroded away. At some point an option is so far out-of-the-money that erosion will actually slow down as expiration approaches as we discussed in Chapter 7 and saw in Figure 7.4.

As for the phenomena, skew will be a huge help to out-of-the-money puts, as we discussed in Part Two. They’ll be more expensive in the manner that counts, (i.e., in implied volatility terms), as they’ll be “rich” to the at-the-money implied volatility, but in real-dollar terms put options that are substantially out-of-the-money still end up being pretty cheap.

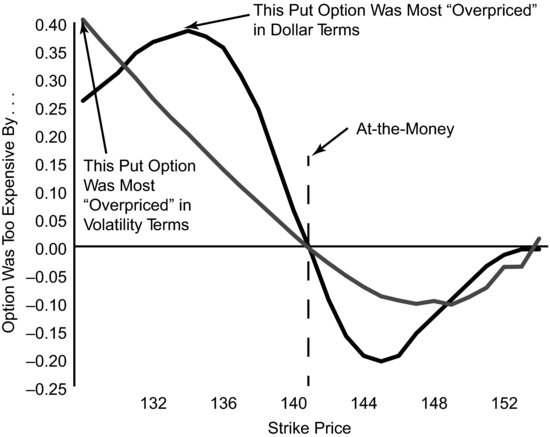

For this SPY 130 put, the effect of skew in volatility terms is about 5.90 volatility points, so if the 130 put had the same implied volatility as the 140 put it would trade for about $0.06, the option price error is $0.29. This means skew adds about $0.29 to the price of the 130 put. The most expensive SPY put in terms of implied volatility terms would be the 128 put, as shown in Figure 11.2, but the observed price was only $0.27, and that’s not much premium. The most overpriced put in dollar terms would be the 134 put which was “too expensive” by $0.39.

FIGURE 11.2 SPY Put Price Error

The volatility risk premium for out-of-the-money puts in volatility terms is gigantic, but in real-dollar terms it trails off pretty quickly as we get further out-of-the-money.

Follow-Up Action

As with covered calls and any other option position, you always have the right and the opportunity to make better informed trades that can lock in a profit, increase the potential profit, or reduce the risk from any existing trade. Not only do you have this right, you have an obligation to yourself to always make the best possible trade, even if it means taking a loss.

No option trade requires that you take it to expiration. Some generally work out best that way, and this is especially true for short option positions, but if the better informed trade is to buy back your short put, then do so.

Follow-up action for a short put usually takes one of two forms, buying back the put or rolling. Rolling a short put is a little like the rolling of a covered call that we discussed in Chapter 10, with a few differences. In rolling our short put option down we’ll buy back the strike price we’re short and sell a put with a lower strike price. This will cost additional premium. In rolling down and out we’ll buy back the put option we’re short and sell a put option with a lower strike price and more time to expiration. This may either cost or generate premium. The goal is to keep the net paid or received close to zero. In rolling up we’ll buy back the put option we’re short and sell a put option with a higher strike price. This will generate additional premium received.

Buying Back a Short Put Option

If most of the time value has come out of a short put, particularly if there is still a significant amount of time to expiration and the underlying stock is above the strike price, it generally makes sense to buy back the put if it can be done cheaply. Cheaply usually means for less than $0.10.

It might also make sense to buy back the short put, even if it has a significant amount of time value left, if the fundamental story for the underlying stock has changed dramatically. If this is the case then the option will usually be in-the-money and buying the option back will usually result in realizing a loss. But traders like to say that “your first loss is your best loss,” meaning that taking the loss if the picture has changed is much better than hoping that the trade works out while running the risk of greater losses while you are continuing to allocate capital and devote time to a losing trade as well. If the fundamental picture has indeed changed, then we’re no longer short a put on a great name that we want to own at a discount; we’re short a put on a name that we don’t particularly like and don’t want to own at anything like the current price.

Buying back a short put if the stock has dropped significantly is likely to be expensive. The option will be more costly because it’s now in-the-money. This is the impact of delta on the option price. Implied volatility is also likely to be higher, making the put more costly than it would be otherwise. This is the impact of vega and the volatility slope on the option’s price. Implied volatility is higher because the stock is seen as being riskier and because the entire volatility skew has ridden the volatility slope higher.

This doesn’t mean that we should lose our nerve just because the stock is lower and is going to be put to us. Unless something fundamental has changed this is what we wanted; we wanted to buy a good stock at a discount. It’s possible that three months from now the stock will be higher and the price we paid will be seen as a great entry point; that fleeting buying opportunity will have vanished. If as option traders we are disciplined enough to only sell puts on good stocks that we want to own at a discount, then this is an opportunity for us to discipline our fear. If something fundamental has changed, then the smart option trader will use the opportunity to reevaluate the stock and make a better informed trade. Simply having the price of the stock drop, absent some other issue, isn’t a fundamental change.

One thing not to do in the situation where the short put is now in-the-money and likely to be exercised, which would leave you long the stock at the strike price, is to sell a call option. You don’t own the stock yet and will never own it if the stock rallies back above the put strike price at expiration. This means the call would be uncovered or naked. This isn’t the time for stock rehabilitation via call selling. Not yet anyway.

ROLLING

While a buywrite is identical to a short put of the same strike price and expiration, when rolling the directions are reversed: Rolling up for a covered call becomes rolling down. For a short put we’ll discuss rolling down, rolling down and out and rolling up.

Rolling Down

Sellers of a put option expect the underlying stock to trade sideways to slightly higher or lower. If they thought it was going to move substantially in either direction they’d use a different strategy. Rather, they’re willing to sell a put in an effort to buy the stock at a discount while getting paid for waiting. If the stock has fallen, put sellers might very well think it’s still a good stock but that short-term circumstances are temporarily depressing the share price. In this situation they might want to reduce the effective price they’re willing to pay for the stock. This is a little like lowering the limit bid price if they were using a limit order to buy the stock.

Trying to buy stock at a discount by selling a put is a great strategy and we don’t want to lose our nerve just because the price of the stock has dropped, but that doesn’t mean we have to be sitting ducks.

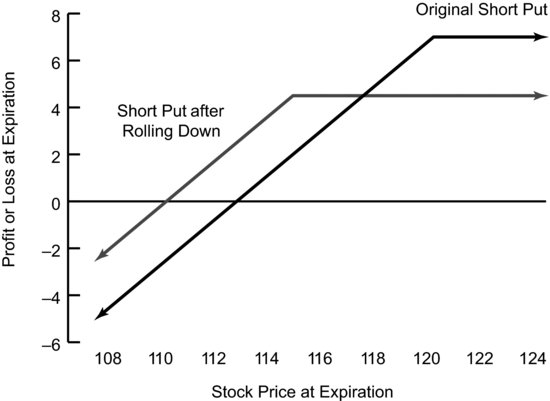

In this situation put sellers can roll the strike price of the put option down. In rolling down the put sellers repurchase the put option they are short and sell another put option with the same expiration date but with a lower strike price.

Rolling the short put down will always cost the trader money, since the put being repurchased is always going to be more expensive than the lower strike put sold. This net premium paid will reduce the maximum potential profit from the trade, which was originally the put premium received. It’s possible for the net premium paid to roll down to exceed the initial premium received, making the best potential outcome a loss. The result is that the effective price potentially paid for the stock will be lower than the effective price would have been if the put hadn’t been rolled down but the net premium collected will be reduced by the cost of the put spread bought to roll down. The effective purchase price of the stock is lower but the profit if the new put option expires worthless is reduced.

For example, if put sellers think very highly of STU Inc., which is trading at $125.00, they might think that current price is reasonable given the company’s prospects, but they’d like to buy it at a discount if they can. If they can’t buy it at a lower price, they’d be willing to forgo buying the stock at all, but they’d like to get paid while waiting to see if their order is going to get filled, as shown in Table 11.5.

Table 11.5 Rolling Down

| Initial Short Put | |

| STU Price | 125.00 |

| Put Strike Price | 120 |

| Put Premium Received | 7.00 |

| Downside Breakeven | 113.00 |

| Upside Regret Point | 132.00 |

| After STU Falls to 120.00 | |

| Follow-Up Trade | Buy 115/120 Put Spread to Roll Down |

| Premium Paid | 2.50 |

| Total Premium Received | 4.50 |

| New Downside Breakeven | 110.50 |

| New Upside Regret Point | 129.50 |

In this case put sellers can sell the 120 strike put at $7.00. That $7.00 would be the maximum profit from the put sale and would be realized with STU at or above $120 at option expiration. The downside breakeven would be $113.00 and this would also be the effective price paid for STU stock if it’s put to them. The regret point, the price at which buying the stock outright would be just as profitable as selling the put, is $132.00.

If STU has fallen slightly and is trading at $120.00 with two weeks to expiration, our put sellers can reexamine the trade and the prospects for STU with the goal of making a better informed trade if one is available. If they realize that the cause of the drop in STU’s stock price is transient trouble for another company in the same space, our put sellers might decide that the possibility exists to buy STU for even less than they had originally been willing to pay. They’ve done analysis of fear versus greed and determine that rolling the short put down slightly is the better informed trade.

STU is now at $120.00 and the 120 strike put might now cost $8.00 while the 115 strike put might now cost $5.50. The put seller can roll down by buying the 120 strike put back at $8.00 while simultaneously selling the 115 put at $5.50. The trade should be executed as a spread for the reasons we’ve already discussed. The net premium paid for this spread is $2.50. This reduces the maximum potential profit on the trade to $4.50 but has reduced the effective purchase price, if assigned, to $110.50.

If STU is below this new strike price of 115 at expiration, then the put seller will be put the stock at an effective price of $110.50 regardless of the stock price at the time. If STU is above $115 at expiration then the new maximum profit of $4.50 will be realized, but the put seller won’t buy the stock. If STU is between $115, the new strike price, and $120, the original strike price, the put seller will have missed the chance to buy the stock and will have paid out $2.50 adding insult to injury.

Figure 11.3 shows the payoff chart for the original trade and for the rolled down trade.

FIGURE 11.3 Original Short Put and Rolled Down Put

Rolling a short put down generally takes advantage of skew since the implied volatility of the new strike should be higher than that of the original strike, but implied volatility in general is likely to be higher making the spread more expensive than it would be otherwise. The daily erosion for the new put is likely to be less than for the original put.

Rolling down will always decrease the maximum potential profit and will cost money to execute, but rolling down generates a lower (better) breakeven point and a lower effective purchase price if the short put is assigned.

Rolling Up

A put seller should be thinking that the underlying stock isn’t going to rally substantially during the term of the option. As we’ve said before, if a rally is your thesis then there are better strategies than selling a put. However, as a put seller you will focus on good companies that you want to own at a discount, so it shouldn’t be too surprising if the underlying stock does rally.

When the stock rallies, the effect of the delta on the option price means the put option price should drop. The effect of vega and the volatility slope will also likely drive down the cost of the option, but even the combined effect might not be enough to make up for a missed opportunity. As you reexamine the landscape for this stock you may decide that a potential headwind hasn’t become the problem you thought it might, or that the market has discounted some other problem. If this is the case you might be willing to pay more than your original effective purchase price but don’t want to simply buy the stock at the current market price.

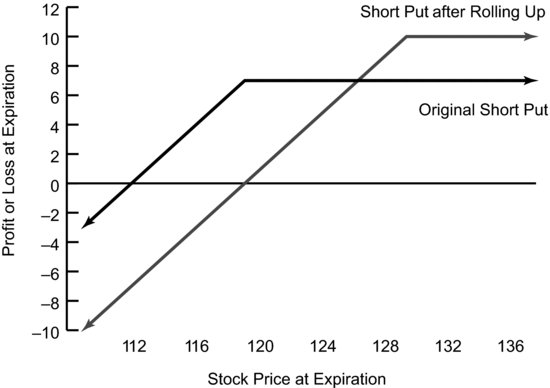

One follow-up strategy that would work in these circumstances would be to roll the short put up to a higher strike price. In rolling up a short put, the trader buys back the original put and sells a higher strike put with the same expiration. The trade should be executed as a spread and will generate additional premium since the new, higher strike price put option sold will cost more than the original lower strike price put.

In our STU example, the stock was at $125.00 when our put seller sold the 120 put for $7.00. If we had the stock put to us in this situation the effective price would be $113.00. This is the downside breakeven point. The upside regret point is $132.00. Above this point we’d regret not buying the stock outright.

If STU rallies to $135 it is now above the original regret point of $132. The original 120 put might now be worth only $1.00. As put sellers we may digest the new information and decide that the potential problem that we thought would keep STU from appreciating is not being viewed as a problem by the market. We may decide that we’re willing to pay a higher effective price but don’t want to pay $135.00. If the 130 put is now trading at $4.00 we can roll up by buying back the 120 put at $1.00 and selling a new 130 put at $4.00. We’re collecting an additional $3.00 in premium to add to the original $7.00 received. We have raised the effective price we would pay for the stock if it is put to us. That effective price is now $120.00, the 130 strike price minus the $10.00 in total premium received. We’ve also increased our maximum potential profit to $10.00, but at the cost of increasing our maximum potential loss and raising our breakeven point from $113.00 to $120.00. Table 11.6 shows the initial short put and the result of rolling up.

Table 11.6 Rolling Up

| Initial Short Put | |

| STU Price | 125.00 |

| Put Strike Price | 120 |

| Put Premium Received | 7.00 |

| Downside Breakeven | 113.00 |

| Upside Regret Point | 132.00 |

| After STU Rallies to 135.00 | |

| Follow-Up Trade | Sell 120/130 Put Spread to Roll Up |

| Premium Received | 3.00 |

| Total Premium Received | 10.00 |

| New Downside Breakeven | 120.00 |

| New Upside Regret Point | 140.00 |

Rolling a short put up is generally hurt by skew; the implied volatility of the old put repurchased is greater than the implied volatility of the new put sold.

Rolling up a short put is also likely to be hurt by volatility slope as the entire volatility curve is likely to have fallen to lower implied volatilities as the stock has rallied. Rolling up leaves us short a put option that is closer to at-the-money so the daily erosion will be greater as we’d expect since our new short put has the same expiration date but has more time value to erode away.

Rolling a short put up will always increase the maximum profit, and does so by increasing the breakeven point and the effective price paid for the stock if assigned.

Figure 11.4 shows the payout graph for the original short put and the position after rolling up.

FIGURE 11.4 Original Short Put and Rolled Up Put

Rolling Down and Out

Rolling a short put down eats into the potential profit of the trade, so the put seller may hesitate to do so, particularly if the underlying stock decreased only slightly in price. This is the sort of scenario the put seller was hoping for, buying the stock at a discount. But if the stock has fallen more than expected or if the price action was troubling, the put seller may not want to give up on the trade but may like to decrease the breakeven point, and the effective purchase price, without spending the premium required to roll down. The way to decrease the breakeven point and the effective purchase price without spending premium is to roll down and out.

In rolling down and out the trader buys back the short put and sells a put that is further out-of-the-money and with more time to expiration. The additional life of the new option should compensate for the lower strike price, resulting in a spread that can be done for little or no net premium.

In our STU rolling down example, STU was trading at $125 and our put seller sold the 30-day 120 strike put option for $7.00. After STU fell to $120.00, the 120 put, now with two weeks to expiration, was trading at $8.00. Instead of rolling down to the 115 strike put of the same expiration and spending $2.50 to do so, the put seller could roll down and out by buying back the 120 strike put at $8.00 and selling a new 6-week 115 strike put for $8.00. There is no net premium spent so the maximum potential profit is still $7.00. The breakeven point has now been lowered to $108.00, which would be the effective purchase price if STU is below $115 at the new expiration, meaning the stock is put to the put seller.

Rolling down and out will always lower the breakeven point and the effective purchase price, but does so by decreasing the daily erosion from the short put. It also can result in buying back the option with the greatest time value remaining, if the original short put is now at-the-money. As our put seller originally wanted to buy the underlying stock at a discount, that’s now more difficult because the stock now has to be below the new lower strike price at expiration.

The smart put seller treats a short put position as a great way to potentially buy a good stock at a discount while getting paid to wait. It’s entirely possible to never get long the stock and that can lead to some big misses but, over time, selling puts will be a great strategy and can be a wonderful way to build a portfolio of stocks for the long term.

- The phenomena and how they impact the initial put option sale and any follow-up action.

- The return from selling the put versus the amount of capital set aside to buy the underlying stock if assigned.

- The effective purchase price and the discount from the existing stock price if assigned.

- The option math generally favors selling shorter-dated, at-the-money puts. We earn our money when we sell the put; we get paid via the daily erosion or theta.

- Getting assigned to buy the stock isn’t necessarily something to fear. It’s a great stock, right? We want to get it put to us but we’re fine collecting and keeping the premium as an alternative.

- Short puts should collect the volatility risk premium.

- Skew helps at initiation if selling out-of-the-money puts.