CHAPTER 10

Covered Calls

Selling a covered call is often the first trade a new option trader executes, and with good reason. Covered calls, sometimes called overwrites, take advantage of several of the phenomena we discussed in Part Two, the volatility risk premium being the most important of the phenomena.

A covered call is executed when you sell a call option against stock that you own. The risk from the short calls is “covered” by ownership of the underlying stock. Importantly, you sell calls representing a number of shares that is equal to or less than the number of shares you own.

It’s important to stress that we’d never sell uncovered or “naked” call options. The risk is just too great, but owning the underlying stock in an amount at least equal to the shares represented by the calls we sell means we’ve defined our risk if the stock rallies, even if the stock rallies tremendously. If the underlying stock rallies then ultimately the price of the call option our trader is short will rally $1 for each $1 in the price of the underlying stock. Each $1 increase in the price of the call option will cost our trader $100 per option shorted. However, each $1 increase in the price of the underlying will earn our trader $100 per round lot of 100 shares even if the stock rallies hugely. As long as our trader has sold calls representing the number of shares of stock owned, the stock will cover the short calls. Table 10.1 shows the relationship between covered and naked calls for a trader short 5, 10, and 15 call options with a long position of 1,000 shares.

Table 10.1 Covered and Naked Calls

| Long 1,000 Shares | |

| Short 10 Call Options | Calls Are Covered |

| Long 1,000 Shares | |

| Short 5 Call Options | Calls Are Covered |

| Long 1,000 Shares | |

| Short 15 Call Options | 10 Calls Are Covered, 5 Calls Are Naked |

Our trader’s risk is defined because no matter how much the stock rallies, the worst that can happen is the stock will be called away. This happens when the owner of the call options that have been sold exercises the calls, and our trader is forced to sell the stock at the strike price of the call.

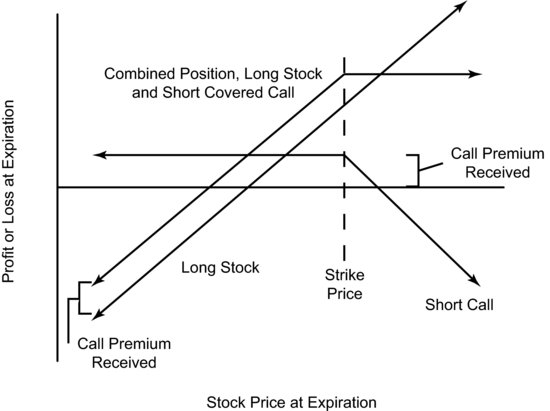

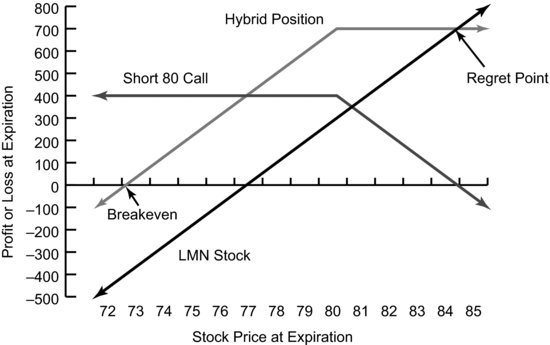

Regardless of whether the owner of the call options exercises them, our trader gets to keep the premium for selling those call options. Because traders get to keep this premium no matter what, it’s actually possible to make money on the stock owned and collect and keep all of this premium. More about that later. Figure 10.1 shows the payoff for the stock our trader owns, the call option sold, and the hybrid covered call position.

FIGURE 10.1 Generic Covered Call Payoff

COVERED CALLS ARE BEST FOR STOCKS YOU ALREADY OWN AND WANT TO KEEP

While it’s entirely possible to have your stock called away if you sell covered calls—if you use the strategy often enough it’s just a matter of time before getting called away happens—covered calls work best on a stock that you like and believe will ultimately rally, but that you think is stuck in neutral for some time.

If you owned a stock and didn’t like it, and didn’t think it would ultimately rally, or if you thought it faced short-term problems that would weigh on the stock price, then selling covered calls wouldn’t be the right strategy. You’d probably be better off simply selling the stock and then thinking about bearish option strategies to profit from the expected break in the stock price. If selling the stock would have adverse tax consequences, then you’d want to hedge the downside exposure using another strategy. While covered calls offer some downside protection in the form of the premium received, that’s not the best way to think about covered calls or to use them. We’ll talk more about covered calls and how to prevent adverse tax consequences of getting called away later in this chapter. For now, Table 10.2 shows the four scenarios that result from selling covered calls when the stock either rallies or falls, sharply or slightly.

Table 10.2 Relative Outcome from Selling Covered Calls

| Stock Price Action | Position Result | Relative Outcome |

| Stock Rallies Slightly | Keep Premium, Don’t Sell Stock, Maximum Profit Achieved | Great |

| Stock Rallies Sharply | Keep Premium, Sell Stock, Regret Selling Covered Call | Less Good |

| Stock Falls Slightly | Keep Premium, Don’t Sell Stock, Premium Cushions Drop | Good |

| Stock Falls Sharply | Keep Premium, Don’t Sell Stock, Loss on Stock Exceeds Premium | Less Bad |

Covered calls or overwrites should always be done on stock you already own. There’s absolutely no reason to buy stock just so you can sell calls on it. Buying the stock and simultaneously selling covered calls, sometimes called a buywrite, is just a way to spend twice as much as necessary in commissions. If you don’t already own the stock, then the next chapter will discuss cash-covered puts, which offer precisely the same risk/reward as a buywrite and don’t require you to pay two commissions. Don’t believe the risk/reward for a buywrite and a cash-covered put are identical? We’ll do the option math in the next chapter to prove it.

THE PHENOMENA AND COVERED CALLS

Of the phenomena we discussed in Part Two, the volatility risk premium is the most important for covered calls. It’s this risk premium that, over time, will lead to returns that are superior to just buying and holding stocks.

Time decay should help drive profitability for a covered call as well, particularly if we make it a point to sell options that have greater daily time decay (i.e., theta). For this reason selling shorter-dated covered calls is almost always better than selling longer-dated covered calls, and selling the weekly options, which are available on a limited selection of indexes, ETFs, and individual equities, is an even better way to get the option math of time decay working in our favor.

The bid/ask spread for our covered call can help make our position more profitable. For very liquid options with narrow bid/ask spreads, selling the covered call at the bid price won’t hurt us too much. The SPY options we discussed in Part Two had bid/ask spreads that were only $0.01 wide, so selling a covered call on SPY at the bid price will cost us only half that amount, since it’s reasonable to think that the fair value of our call option is the midpoint of the bid/ask spread. That’s not likely to significantly impact the ultimate profitability of our trade.

For options that are liquid but with wider bid/ask spreads like the Google options we examined in Part Two, there is a real danger for the width of the bid/ask spread to have a negative impact on our covered call if we simply sell the bid price. Going back to the Google example, the at-the-money call (the 585 strike) had a bid price of $8.40 and an ask price of $8.70. If that means the fair value of the call is $8.55, then simply selling the bid price would cost $0.15 which is nearly 2 percent of the call’s value, too much to simply give away.

In illiquid options with wider bid/ask spreads, we can offer our covered call in the top half of the bid/ask spread and actually use the bid/ask spread and illiquidity to our advantage. We’ll discuss all of these situations later in this chapter.

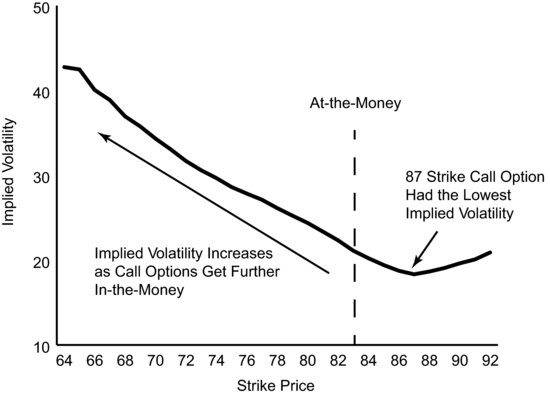

Skew may hurt our covered call trade if we choose to sell an out-of-the-money call that falls in the trough of the skew that we saw in Part Two. Figure 10.2 is similar to Figure 6.1, which displayed option skew for IWM options, options on the Russell 2000 ETF.

FIGURE 10.2 Skew and the Covered Call

If we were long the Russell 2000 ETF (IWM) and wanted to sell a covered call, then selling the 87 strike call would result in selling the lowest implied volatility, the real measure of how expensive options are. Likewise, skew may help our covered call if we chose to sell an in-the-money call option that has an implied volatility that is greater than the at-the-money call option. If we sold the 75 strike call then we’d really be taking advantage of skew. We’d be selling an option with an implied volatility that is significantly higher than that of the at-the-money call. That 75 call has other issues that mean it may not be the best covered call to sell, but skew isn’t one of them. It’s important to remember that skew will help or hurt our covered call trade when we initially execute it.

Volatility slope may make taking our trade off before expiration easier or more difficult depending on whether our stock has moved up or down since we initiated our position. Similarly, volatility slope may help or hinder our efforts to make a follow-up trade, as we’ll discuss later in this chapter. If our stock has fallen significantly since we sold our covered call, then the resulting general increase in implied volatility means that our call may be more expensive than it would be if the stock hadn’t moved and if the volatility skew curve hadn’t moved up the volatility slope. If the stock has fallen enough, then the call may be worthless or nearly so; if the stock has only dropped slightly then it’ll still have some value, and it will have more value than it would otherwise and thus be more expensive to repurchase than it would be otherwise.

If we had sold an out-of-the-money call option and the stock rallied slightly, then volatility slope will have likely helped our trade, since the entire skew graph rides the volatility slope lower. If our call is still out-of-the-money or is at-the-money, then it’s possible that the combination of time-decay and volatility-slope would result in our option being worth less than we sold it for, despite being closer to at-the-money. One exception will be if we sold the strike price at the bottom of the skew trough. In that case, no matter which way the stock moves, our strike price will move up the volatility slope. The passage of time may mean that our option is worth less than we sold it for, but in this case that’s due to erosion, not skew.

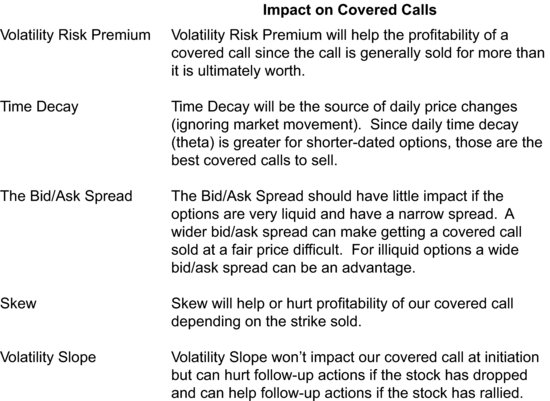

Figure 10.3 provides the general impact of all of the phenomena on our covered call. Any of these can be overwhelmed by the others and by other factors, such as movement of the underlying stock or a change in the general level of implied volatility.

FIGURE 10.3 General Impact of the Phenomena on Covered Call

Ultimately the goal of a covered call is to enjoy the natural diversification that the hybrid position offers and to collect the volatility risk premium incorporated in the price of the option.

BREAKEVEN POINTS

Since we’re always going to sell covered calls on stocks we already own, it doesn’t make much sense to use the purchase price of the stock in calculating breakeven points or return figures. We may have bought the stock years ago at a price much lower (or higher) than the current market price. Since our call option price is a function of the current market price for the stock, and since we’re really only long our stock from the current market price (because we’ve made, in one way or another, the decision not to sell our stock right now), the current market price is the proper price for calculating breakeven levels and return figures.

The downside breakeven point is the price of the stock when we executed our option minus the premium we received for selling the covered call. (See Table 10.3.) If the stock is above this level at expiration but below the upside regret point, then we’ve come out ahead by selling the covered call. (See Table 10.4 for data describing the upside regret point of a covered call.) Since we’re selling covered calls only on stock we want to own anyway, this downside breakeven level is really just for our information. We’d own the stock anyway, but as long as the stock is above that breakeven point at expiration we’ve come out ahead by selling the covered call.

Table 10.3 Covered Call Downside Breakeven Point

| Breakeven Point Calculation | |

| Market Price of Stock | 98.75 |

| Covered Call Strike Price | 100 |

| Covered Call Premium Received | 4.50 |

| Downside Breakeven Point | 94.25 (Stock Price Minus Premium) |

Table 10.4 Covered Call Upside Regret Point

| Regret Point Calculation | |

| Market Price of Stock | 98.75 |

| Covered Call Strike Price | 100 |

| Covered Call Premium Received | 4.50 |

| Upside Regret Point | 104.50 (Strike Price Plus Premium) |

The upside breakeven point isn’t really a breakeven point since we’ll have made money on our stock and we’ll have kept the call premium we received. It’s better to call this point the regret point, since that more fully explains what it means to us: Above this point we will regret having sold our covered call because our stock will be called away and the forgone profit on the stock is greater than the premium received from selling the call option. The regret point is the strike price of our option plus the premium received. At precisely this point we’re exactly as well off having sold our covered call as we would be if we hadn’t. Above this point we’re worse off for having sold the covered call. Below this point we’re better off having sold the covered call.

Let’s look at a broader example to determine not only the downside breakeven point and the upside regret point, but the profit and loss at any price for the underlying stock. To do that let’s assume a trader owns 100 shares of LMN Corporation, which is currently trading at $77 per share. The trader sells an 80 strike call option on LMN for $4.00; by doing so he’s executed a covered call. His ownership of 100 shares covers the upside risk in being short one call option. If LMN is below $80 at expiration, the call option expires worthless and the trader’s potential responsibility to sell his LMN stock at $80 expires as well. He keeps the $4.00 he received for selling the call and he’s $4.00 better off than if he hadn’t sold the call.

If LMN is above $80 at option expiration, then the owner of the option is going to exercise his right to buy the shares at $80. Assuming our trader didn’t buy back this call prior to expiration he’s going to be assigned to sell the shares. Assignment is the opposite side of exercise. The trader long the option exercises it and, in the case of a call option, buys the underlying stock at the strike price. The trader short the option is assigned, more or less randomly, to sell the underlying stock at the strike price. If LMN is trading at $83 at option expiration, the call option will be exercised by the option owner and, in the case of our trader’s covered call option, the owner of the call option will buy LMN at $80 per share. Our trader will be required to deliver his 100 shares and he’ll receive $80 for each of them. Our trader will also get to keep the $4.00 initially received for selling the covered call, and will be better off by $1.00 than if he hadn’t sold the covered call, even though the stock got called away.

Table 10.5 shows the profit and loss for a range of prices at expiration for this covered call position. From this it’s easy to see how the breakeven and regret points are calculated. Creating a table like this is often the best way to understand any option trade. Pay particular attention to the profit or loss at inflection points, such as the strike price (or strike prices for strategies with more than one option) and breakeven and regret points. Soon you’ll understand these issues instinctively and won’t have to create a chart each time, but it’s a great way to learn. In this situation the breakeven price is $73. That’s the price where the total profit or loss is zero. The regret point is $84. Above that level our trader is worse off for having sold the covered call.

Table 10.5 Profit and Loss from LMN Covered Call

Figure 10.4 highlights the covered call breakeven and regret points for LMN Corporation.

FIGURE 10.4 Covered Call Breakeven and Regret Points

The maximum profit from any covered call position occurs when the underlying stock is at the strike price at expiration. In the case of the LMN covered call the maximum profit occurs when LMN is at $80 at option expiration. The maximum profit is also achieved when the underlying stock is above the strike price at expiration. This relationship, maximum profit occurring with the underlying stock at the short strike price at expiration, holds for nearly every option strategy, not just covered calls. We’ll discuss this later in Part Three.

An important element of a covered call is that it limits the profit potential from ownership of the underlying stock. You’re selling much of this profit potential for cash. As we’ve seen when discussing the volatility risk premium, over time, we’re selling this potential for more than it’s worth, but that doesn’t mean it won’t feel like a swift kick to the head when we’ve sold a covered call only to see our stock rally well past the regret point. A central element to successful option trading is to remain disciplined when this happens and make the best possible follow-up trade if there is one. If there isn’t a good follow-up trade then the best tactic is to learn from the situation; again, be disciplined enough to realize that this sort of thing will happen from time to time, but if we have the option math on our side, over time good things are going to happen.

BREAKEVEN POINTS AND RATES OF RETURN

It’s usually helpful to normalize the breakeven point, the regret point, and the amount of premium received so that we can compare them rigorously rather than subjectively. It’s also helpful to turn the rates of return into annualized numbers to remove the number of days to expiration as a factor.

Option Premium Yield

The easiest and possibly most important rate is the yield that the covered call will generate. If the covered call is at-the-money or out-of-the-money, then the yield is simply the premium received divided by the stock price. In the case of the LMN call we discussed, the yield would be $4/$77 or 5.20 percent. (See Table 10.6.) To annualize this number quickly we’d simply multiply this 5.20 percent by the number of time periods in a year. If our 80 strike call was a 30-day option, then the annualized yield would be 5.2 percent times 12, or 62.4 percent. This number is an approximation since it doesn’t take compounding into account, but it will provide a useful guide to the annualized yield that can be compared to other structures. The formula for precisely annualizing yield can be found in the Appendix.

Table 10.6 Option Premium Yield

| Option Premium Yield | |

| Current Stock Price | 77.00 |

| Call Premium Received | 4.00 |

| Option Premium Yield | 5.20% (4.00/77.00) |

| Annualized Yield | 62.40% (5.20% x 12) |

If we use an option pricing model like the one available at the website OptionMath.com we’d find that this option had an implied volatility of about 60 percent so these options are pretty expensive. We’d expect a high annualized yield from a high implied volatility.

If our covered call is in-the-money, then the yield is correctly calculated by using only the time value of the option. To use the entire option premium would be to include the inherent value as part of the option premium yield, which would overstate the yield; it’s stealing from Peter to pay Paul because we’ll be called away at a price lower than the current market price. In the LMN example, if the 75 strike call had been worth $5, then $2 is inherent value. The yield from selling that covered call would be $3/$77, or 3.90 percent. To say it was $5/$77, or 6.49 percent, would be like stealing $2, the amount by which the $75 is in-the-money, from the value of the stock and adding it to the call.

This option yield as we’ve calculated it is the best number to use because it assumes that the underlying stock doesn’t move for the term of our option. This is in line with the analysis that leads us to consider selling covered calls in the first place—that we own a quality stock but it’s not going anywhere for the term of our option.

Return if Called Away

The return if called away is simply the difference between where the stock is trading currently and the regret point compared to the current price of the stock. For our LMN covered call the regret point was 84 and the stock was currently trading at $77.00. The difference is 7 points. This 7 points can also be calculated by adding the amount by which the option is out-of-the-money to the premium received. (See Table 10.7.) The return if called away is thus $7/$77 or 9.1 percent. If we were to annualize this it would be a 109.2 percent annual return. Again, this annualized number is an approximation, since it doesn’t take compounding into effect.

Table 10.7 Return if Called Away

| Return if Called Away | |

| Current Stock Price | 77.00 |

| Upside Regret Point | 84.00 |

| Difference | 7.00 |

| Return if Called Away | 9.10% (7.00/77.00) |

| Annualized Return if Called Away | 109.20% (9.10%×12) |

These annualized numbers should be used for comparison purposes only. There’s no assurance that a covered call seller would be able to get the same level of yield next month as they received this month.

USING COVERED CALLS FOR DOWNSIDE PROTECTION

Many option traders believe covered calls should be used to provide downside protection. This is dangerous, as it suggests more protection than is really offered and leaves the owner of the stock with a false sense of security. In our LMN example, the $4 received in the form of call premium only protected ownership of the stock down to the breakeven point of 73, a drop of about 5 percent. Given 60 percent implied volatility and 30 days to expiration the option math tells us there’s about a 41 percent likelihood LMN will be below 73 at option expiration. That’s an awful big likelihood that our covered call isn’t going to provide enough protection. If we’re worried about LMN dropping, there are better strategies, starting with selling the stock, which can be employed. One problem with using covered calls for downside protection is that if the stock does drop, then the volatility slope will make closing the position by buying the call back more expensive than we might expect.

An option trader is better off thinking of a covered call as a way to generate income by taking advantage of the phenomena we discussed in Part Two while generating a breakeven point that is below the current stock price.

If we consider covered calls to be downside protection the risk is that the stock falls by more than the option premium received. Since we’re only selling covered calls on good stocks, stocks that we want to own anyway, we’re certainly better off than if we hadn’t sold the covered call, but this is a little like falling down and breaking a leg but being happy that we found money on the ground while we were rolling around in pain. Finding the money is a positive, but it may not be a net positive.

The more important risk in a covered call is if the underlying stock rallies to a price that’s greater than the strike price plus the option premium received. This is the regret point we’ve already discussed. Since we’re writing covered calls on stock we like, it seems logical that this is the more likely outcome. Since our effort to prevent this occurrence changes the math of the breakeven point, we’re naturally going to sacrifice some downside protection to decrease the likelihood of being called away. If we think of covered calls as downside protection, we’ll tend to go the other way and sacrifice the upside in search of greater downside protection. That doesn’t make much sense for stocks we like.

IF OUR STOCK RALLIES

If the underlying stock rallies then we might find our stock called away. This is not necessarily bad, and prior to expiration we have alternatives to simply sitting back and getting the notice of assignment.

Prior to expiration or assignment you always have the right to buy your option back. In doing so you have extinguished your responsibility to sell your stock at the strike price but at the cost of the premium you have to pay. This premium might be more or less than the premium you initially received.

Just because our stock has rallied doesn’t mean we will necessarily get called away. If LMN rallies from $77 to $79 at option expiration, then the 80 call option our trader sold will have no inherent value and the owner of the option will not exercise it. Why would the owner do that—meaning why pay $80 (the call option’s strike price) for stock that could be bought at $79 in the open market? Our covered call trader has made money on both sides of this trade. The LMN stock has appreciated by $2 and the call option sold for $4 will expire worthless. With LMN at $79 at option expiration, our trader is $600 better off.

If the stock does rally enough then our covered call trader will indeed find the stock called away. Getting called away might actually result in the maximum potential profit from this hybrid covered call position. In the LMN example we looked at previously, if LMN is at 81 at expiration, then we’ll find that the owner of the 80 call will exercise the option—to not exercise would be to forgo the $1 of inherent value of the option—but the covered call seller will have made the maximum amount of profit: $400 on LMN stock as it has rallied from $77 to $81, and $300 on the call option as it was initially sold for $4 and is worth $1 at expiration.

SELECTING THE COVERED CALL

In-the-Money, At-the-Money and Out-of-the-Money

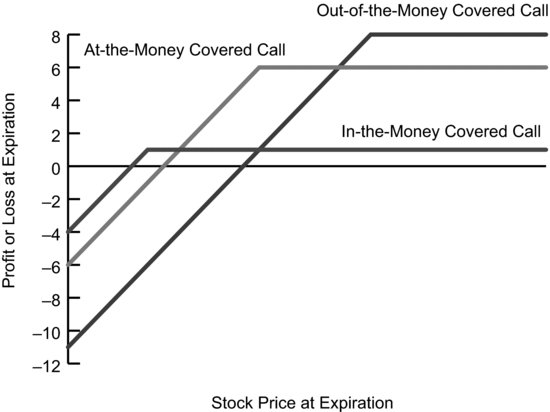

As we saw in Part One, at-the-money options have the greatest amount of time value and thus the greatest daily erosion (i.e., theta). In-the-money call options have the highest implied volatility thanks to skew, and out-of-the-money call options have the least likelihood of losing the stock that we want to keep. Which one should we sell?

As we said in Part One, there’s no right answer, and even in using an option pricing model like the one at OptionMath.com we can only compare the likelihood of getting called away (the delta) and the daily erosion (the theta) rather than find the best call option to sell.

The difference between these three moneyness alternatives isn’t so much the difference in the options but rather it’s the difference in the resulting hybrid position.

A covered call that’s significantly in-the-money results in a hybrid position that’s very much like a bond. The odds of getting our stock called away are very high, but in that case we’ll be left to collect cash based on the strike price and the time value of the call when we sold it. This total amount of cash is unlikely to change, so the total payoff is likely to be very stable, much like a bond. As the likelihood that the call option will end up in-the-money (i.e., delta) increases, this bond-like nature of our position increases. Figure 10.5, a profit-and-loss chart for covered calls that are in-the-money (ITM), at-the-money (ATM), and out-of-the-money (OTM), shows the payoff for a deeply in-the-money covered call. There’s very little additional profit generated but there’s also very low probability of a loss. A loss occurs at a much lower price, further left in the chart, than for the other covered calls.

FIGURE 10.5 Payoff chart for ITM, ATM, and OTM Covered Calls

A covered call that’s significantly out-of-the-money results in a combined position that’s very much like the outright ownership of the stock. The bulk of the returns from the hybrid position will come from the underlying stock, and very little of the returns will come from the option. The only contribution the option will make is the premium received, and if the option is significantly out-of-the-money then this premium will be very small. If the delta of our call option is very low, meaning the likelihood of getting called away is very low, this increases the stock-like nature of the returns of the hybrid position. Figure 10.5 also shows an out-of-the-money covered call as the highest payoff chart. It has a very high potential profit, but this requires the stock to rally substantially and provides very little additional profit if the stock is unchanged. It also offers very little downside protection. A loss occurs for an out-of-the-money covered call at a higher price (further right on Figure 10.5) than for the other two types of covered calls.

A covered call that is at-the-money results in a combined position that’s as different as possible from either a bond or stock. As much of the return as possible will be generated by the time value of the option. The day-to-day returns will fluctuate, as the time decay is greatest with an at-the-money option. A covered call that is at-the-money offers the greatest amount of time value, but the likelihood of getting called away is near 50 percent, which may be too high.

One important word about the at-the-money option—option pricing models assume that the underlying asset or stock is going to appreciate by the risk-free interest rate for the term of the option. This means that the truly at-the-money option may not be what you think it is.

If another stock was trading at $100 and the risk-free interest rate was 12 percent, then an option pricing model would expect the stock to appreciate by 12 percent annually, or about 1 percent monthly. In this case, with 30 days to expiration, the real at-the-money call option would be the 101 strike call option. This is the call option that would have a delta (i.e., the likelihood of finishing in-the-money) of 50. This will also be the call option with the greatest amount of time value and the greatest amount of daily price erosion.

When interest rates are low the effect will be very small but interest rates won’t always be low, so it’s important to identify the “real” at-the-money strike price.

In-the-Money

An in-the-money covered call will have a greater implied volatility than an at-the-money or out-of-the-money call, as we’ve seen in Part Two in our discussion of skew. This means that an in-the-money call option, that’s a call option with a strike price below the current market price of the stock, will have more time value than a call option that’s out-of-the-money by an equal amount. This additional time value and greater option premium will work to increase the profitability of this covered call, but selling an in-the-money call option, particularly one that’s deeply in-the-money, is really a lot like putting in an order to sell the stock. The price received is very likely to be the strike price plus the premium received. The only way this is not the amount received is if the stock drops below the strike price and the owner of the option does not exercise.

Many novice covered call sellers will look at a deeply in-the-money call and think that’s the one they want to sell because it’s more expensive than an at-the-money call or an out-of-the-money call. The problem with this thinking is that most of that option premium is inherent value, which doesn’t do the covered call seller any good. Selling a covered call to capture the inherent value is just a function of taking value from the stock we own and transferring it to the call option we’re selling. I don’t gain anything by selling a call option that’s $20 in-the-money for $20. I collect $20 for selling the option but it’ll end up getting called away from me at a strike price that’s $20 below the current market value. I’m no better off by doing this than I am from taking a $20 bill from one pocket and moving it to another pocket.

Some option practitioners say that an in-the-money covered call is the most conservative covered call but again, this is the equivalent of selling our stock and it’s certainly true that selling our stock and keeping the proceeds in cash is a pretty conservative move. It’s also one that makes earning a profit pretty tough.

Selling an in-the-money covered call, particularly a deeply in-the-money call, generates a hybrid position that’s very bond-like.

Out-of-the-Money

Out-of-the-money covered calls offer the maximum profit potential for the combined structure, but this maximum profit is only realized if the underlying stock rallies and the point of maximum profit, as it usually does, occurs when the stock is at the strike price we’ve sold. The problem with this potentially greater upside is that the option premium received is reduced as the call option gets further out-of-the-money.

Of the phenomena we discussed in Part Two, skew is the largest potential problem for selling out-of-the-money covered calls. Implied volatility generally falls as we move to strike prices that are above the at-the-money strike price, as we saw in Figure 10.2. Eventually the implied volatility will turn upward again, but in the IWM skew we examined that only occurred once the call price was below $0.25, and in the case of our IWM 87 call option the last price as quoted was $0.22. That was less than 0.3 percent of the price of the underlying, so any gain from selling the 87 strike call would have been minimal. Even if we were satisfied with $0.22 in premium it would likely be reduced by the commission charged to execute that trade.

As we discussed in Chapter 6, one of the reasons skew exists is that owners are willing to sell covered calls and they thereby drive down the price (and the implied volatility) of these out-of-the-money calls. The smart option trader will stay away from selling this cheapest call for two reasons. First, it doesn’t get the math of the phenomena working for us, and second, we don’t want to follow the herd.

Selling an out-of-the-money covered call, particularly one that’s significantly out-of-the-money, generates a hybrid position that’s very stock-like.

At-the-Money

The at-the-money covered call has many elements working for it. It has the greatest amount of time value, so it has the greatest amount of daily erosion of all the options that share that expiration date. The at-the-money call has a fair implied volatility and the volatility risk premium means that, over time, we’re selling the call for more than it will ultimately be worth. We could sell calls with a greater implied volatility but, as we’ve seen, that would drastically increase the likelihood of getting called away, which means that, in many ways, selling an in-the-money covered call is like selling our stock.

The true at-the-money covered call has about a 50 percent likelihood of being exercised, so we’re as likely to keep our stock as to have it called away. Since we like the stock, a 50 percent chance of getting called away may seem like too much, but we always have the opportunity to make a better informed decision later. We’ll discuss those tactics later in this chapter when discussing follow-up trades.

Of the phenomena we discussed in Part Two, the volatility risk premium is the biggest driver of the ultimate profit of our covered call trade, with the daily erosion being related as the daily erosion is how we collect the time value, which includes the volatility risk premium.

Since the at-the-money call option has the greatest amount of time value, it also offers the potential for the greatest additional return. (See Table 10.8.) Looking back at the IWM options, IWM was at $82.64 when those prices were quoted. That would make the at-the-money call the 83 strike call. The 83 call was quoted at $1.46 bid/$1.48 ask. Let’s assume that the fair value was $1.47 and let’s assume that is the price we received. That means that the return from selling that covered call would be 1.78 percent ($1.47/$82.64) or nearly 7 times greater than the return from selling the out-of-the-money call we looked at, the 87 strike call. Since the 83 strike call is actually a little out of the money, the delta of the 83 call would be slightly less than 50. The actual delta was 47, meaning there was about a 47 percent chance that the option would be in-the-money at expiration.

Table 10.8 Selling the At-the-Money Covered Call

| IWM Price | 82.64 |

| 83 Strike Call Bid/Ask | 1.46/1.48 |

| 83 Strike Call Fair Value | 1.47 |

| 83 Call Yield | 1.78% ($1.47/$82.64) |

| 83 Call Option Delta | 47 |

This leads us to one of the elements that the at-the-money covered call has working against it: the likelihood of getting our stock called away and the potential need for a follow-up trade to keep that from happening.

Ideally, if we’d sold the 83 strike covered call, IWM would rally only very slightly and would be just below 83 at expiration. We’d make the maximum amount from our covered call in that we’d collect and keep the entire $1.47 received, and because IWM is just below the strike price we wouldn’t be assigned to sell our stock. We could then analyze IWM again and potentially sell it, sell another covered call, do nothing or do something else.

Selling the at-the-money covered call generates a hybrid position that takes the maximum advantage of time value and daily erosion and also generates a position that has the best of the qualities of a bond and the best of the qualities of a stock.

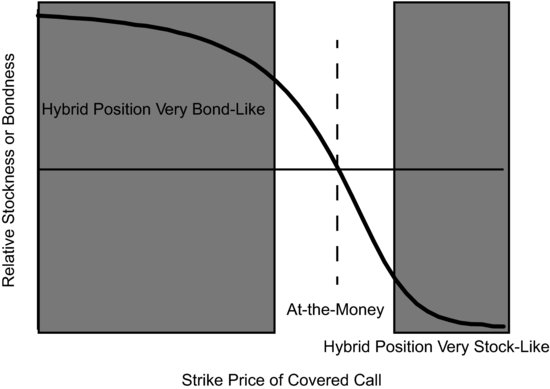

Stock-Like or Bond-Like

The easiest way to determine whether your hybrid position will be stock-like or bond-like is simply to look at the delta of the option you’re thinking of selling. The pricing models at OptionMath.com can calculate the deltas of the call options that are candidates for selling as a covered call. If it has a high delta, then the hybrid position will be very bond-like. If it has a low delta, then the hybrid position will be very stock-like. If it has a delta near 50 then the hybrid position will enjoy the best of both worlds. Figure 10.6 shows this in graph form.

FIGURE 10.6 Covered Call Bondness or Stockness

COVERED CALLS AND DAILY PRICE EROSION

Daily price erosion will theoretically be how we collect the value from the covered call we sell. Since daily erosion, also called theta, increases as time to expiration nears, a call seller (actually any option seller) is generally better off selling shorter-dated calls than longer-dated calls.

The LMN 80 strike price call option that our theoretical covered call seller wants to execute has time value of $4.00, an implied volatility of about 60 percent, and theoretical daily price erosion of $0.086, meaning that today we’d expect the price to decline to $3.914 solely due to the effect of time decay. The exact same option with 60 percent implied volatility but 60 days to expiration would be worth about $6.20 and have daily erosion of only $0.063. (See Table 10.9). These calculations can be made using the tools at OptionMath.com.

Table 10.9 Covered Call, Daily Erosion, and Time to Expiration

| LMN 30-Day 80 Strike Call Option | |

| Price | 4.00 |

| Expected Daily Erosion | 0.086 |

| Delta (Likelihood of Getting Called Away) | 45 |

| LMN 60-Day 80 Strike Call Option | |

| Price | 6.20 |

| Expected Daily Erosion | 0.063 |

| Delta (Likelihood of Getting Called Away) | 49 |

In this case, as in almost every covered call situation, the covered call seller would be better off selling a series of 30-day covered calls rather than a single 60-day covered call. With LMN calls the effect of selling a series of calls would be to collect $4.00 now and $4.00 in 30 days, assuming that all else stays the same, or a total of $8.00. Compare this to the $6.20 collected if our covered call seller were to sell a 60-day call option. In addition, the delta of that 60-day option is greater, reflecting a slightly greater likelihood of getting called away than from selling a series of 30-day calls.

Because theta stops increasing for options that are significantly distant from at-the-money, this may not be the case for deeply in-the-money or out-of-the-money calls, but this is only one of many reasons not to use calls that are significantly distant from at-the-money.

COVERED CALLS AND THE VOLATILITY RISK PREMIUM

The volatility risk premium is the real source of the additional return generated by covered calls. As we discussed in Part Two, the volatility risk premium for options can be substantial. For SPX options (options on the S&P 500), the volatility risk premium has added to the price of the at-the-money call options and generated additional return for the covered call seller. Going back to 1990, the at-the-money SPX call was priced at 1.890 percent of the S&P 500, yet it only ended up being worth 1.726 percent of the S&P 500. That translated to these calls being overpriced by an average of $1.26 each month. (See Table 10.10.)

Table 10.10 SPX 30-Day At-the-Money Call Option Volatility Risk Premium

| Average Call Price as Percentage of the S&P | 1.890% |

| Average Value of Call Option as Percentage of the S&P | 1.726% |

| Call Option Was Overpriced by an Average of | 0.16% of the S&P |

| Greatest Overpricing (October 1998) | 2.69% of the S&P |

| Greatest Underpricing (September 2008) | 6.03% of the S&P |

Notice the asymmetry inherent in the greatest overpricing of the call of 2.69 percent versus the greatest underpricing of the call of 6.03 percent.

PLACING YOUR COVERED CALL ORDER

Your covered call order generally will need to be executed in the same account that owns the underlying, covering stock. This will be a requirement of your broker to make certain that the stock exists if it has to be delivered in order to satisfy an assignment notice and to make certain the stock can be freely delivered and isn’t encumbered.

If the options we want to sell are generally liquid with a narrow bid/ask spread, then there’s very little to be gained with a complicated execution. For example, Table 10.11 shows a recent SPY market.

Table 10.11 SPY Covered Call Execution

| SPY Last Trade 138.75 | ||

| Bid Price | Ask Price | |

| 35-Day 139 Call Option | 2.00 | 2.01 |

In this case it’s reasonable to assume that the market’s estimation of fair value of this option is $2.005. It’s also reasonable to offer the option for sale at $2.01 using a limit order, particularly if the market was higher that day. It would also be reasonable to simply sell the call at $2.00. The difference between our realized price of $2.00 and the fair value of $2.005 is as small as is possible and that $0.005 is unlikely to have much of an impact on the profitability of our trade.

However, even though we want to sell our call at the market bid, it’s always a good idea to enter this order as a limit order to sell at $2.00 rather than as a market order to sell. Remember that a market order will sell your call at the highest current bid, but if something unusual happens it’s possible that the market will drop suddenly and a market order to sell might get filled at $1.90 or even lower. If you enter a limit order to sell at $2.00 and the market for these calls drops, then you can leave your order to get filled at $2.00 or you can reexamine the situation in light of this volatility.

If the option we want to sell is in a liquid option market with wide bid/ask spreads like the Google options we reviewed in Part Two, then we want to be a little more careful in our execution.

Again in this case it’s reasonable to assume that the fair value of this call option is the midpoint of the bid and the offer, $19.60 in this case. Many traders would place a limit order to sell the covered all at $19.60 and it would be tough to argue against that type of order. If Google were to rally just $0.10, then the fair value of this option would be about $19.65. Since this call is very close to at-the-money, the delta is very close to 50. Remember that because delta equals the option’s price movement relative to the underlying’s price movement, we know that if the stock rallies by $0.10 the at-the-money call option price will increase by $0.05, and it’s likely a market maker would buy the call at our $19.60 limit price. However, the only way that $19.60 limit will be filled is if Google does indeed increase in price. In this situation, particularly for those who don’t want to monitor their execution, it would be perfectly acceptable to sell the covered call at the $19.50 bid price. Again we would use a limit order to make certain we received the $19.50 we expected but the $0.10 difference from the fair value is only a tiny fraction of the total option value and is unlikely to substantially impact the profitability of our trade. (See Table 10.12.)

Table 10.12 GOOG Covered Call Execution

| GOOG Last Trade 610.45 | ||

| Bid Price | Ask Price | |

| 35-Day 615 Call Option | 19.50 | 19.70 |

If our option is rarely traded and has a wide bid/ask spread then we need to be very careful in our execution, and we can use the fact that we’re providing liquidity to our advantage and demand to be paid for doing so. Table 10.13 shows such a market.

Table 10.13 Onyx (ONXX) Pharmaceutical Covered Call Execution

| ONXX Last Trade 37.37 | ||

| Bid Price | Ask Price | |

| 35-Day 38 Call Option | 1.45 | 1.65 |

In this case the options rarely trade, the total daily option volume at the time was less than 2,500, and the fear for market makers is that if they sell an option they may not be able to reduce or close that risk without paying the ask price of someone else. If unexpected news is released and the market maker wanted to pay the ask price to close the position, he may find that the news has chased other market makers from offering. The market maker may not be able to buy the option back at any price. Because of this, the market maker would rather be a buyer than a seller of thinly traded options and will adjust his bids and offers accordingly. We can assume that the fair value of this option is below the midpoint of the bid/ask. It’s probably very close to $1.50.

In this situation we can offer our call for sale at the midpoint, or $1.55, and actually be selling the option for more than its fair value. We could even get a little greedier and offer it for sale at $1.60. Regardless, in this situation we’d have to use a limit offer and would likely have to monitor the execution with the goal of canceling our order if a $0.20 rally in ONXX didn’t result in getting our order filled, since a $0.20 rally should increase the value of our 50 delta option by $0.10. If you left your $1.55 offer in the market indefinitely, then the few market makers paying attention would have no reason to buy that option before they absolutely had to. They would “lean” on your offer until buying the call at $1.55 means paying well below fair value.

FOLLOW-UP ACTION

Just because you’ve executed an option trade doesn’t mean you have to take it all the way to execution. That’s often the best solution but you always have the right to make a better trade or, in the case of a covered call, to make a follow-up trade that improves your original trade.

Follow-up action generally falls into two categories, buying back the call we’re short and rolling into another option by buying back the option we’re short, and selling another option. While rolling there are essentially four alternatives: rolling up, rolling down, rolling up and out, and rolling down and out.

In rolling up we buy back the option we’re short and sell an option with the same expiration but a higher strike price. In rolling down we buy back the option we’re short and sell an option with the same expiration but a lower strike price. In rolling up and out, we buy back the option we’re short and sell a higher strike call that expires later. In rolling down and out we buy back the option we’re short and sell a lower strike call that expires later. The first three all have their place. The fourth, rolling down and out, is rarely the right solution.

Buying Back

There’s no reason to remain short a covered call if the call has very little time value left and if there’s a significant amount of time until expiration. This will generally happen if the stock has fallen since executing the covered call. It might also happen if some time has passed and implied volatility and option prices have fallen. In the first case there is probably little reason to buy back this option. We own a stock we want to own, so the drop in price is a risk we would have borne even if we weren’t short the covered call. Assuming we sold a fairly short-dated covered call there can’t be more than two or three weeks until expiration. Getting called away now that the stock has dropped is a very remote possibility and given the recent weakness might actually be a bonus, since we could move on to another stock without the wild swings.

In the second situation, where implied volatility and option prices have fallen without the underlying stock dropping, buying back the covered call is likely to make sense, particularly if we don’t spend much for it. Remember that the bulk of the price erosion will take place close to expiration, and if there’s significant time value left we don’t want to forgo that. Buying back a covered call in this instance generally makes sense only if the option can be purchased for less than $0.10 and if there is a fair amount of time to expiration (i.e., at least a week).

A final situation where buying back our covered call can make sense is when allowing our stock to be called away would be a taxable event and force us to realize, and pay taxes on, gains that were previously unrealized. In this situation it might very well make sense to buy back the call, but if realizing a gain is so onerous that you’d buy back covered calls every time it appears they’ll expire in-the-money, you should probably not be selling covered calls against that stock to begin with.

GETTING ASSIGNED

For those worried about realizing a taxable gain, it’s important to know when we’re likely to be assigned to sell our stock at the strike price.

If our covered call has any time value at all then it’s unlikely we’ll get assigned, with one exception. If the covered call has time value, even if it’s just a few cents, the owner would be better off simply selling the call out and thereby collecting that remaining time value. If the owner exercises the option he forgoes any time value remaining in the option price. Table 10.14 provides an example.

Table 10.14 Getting Assigned

| Stock Price | 58.42 |

| 50 Strike Call Option with 15 Days to Expiration | 8.55 |

| Time Value | 0.13 |

| Value from Selling Call Option | 8.55 |

| Value from Exercising the Call Option | 8.42 |

In this simple example, exercising the call option early would mean losing the $0.13 of time value included in the price. The exerciser would own stock at $50.00, the strike price, but at the cost of the call option, which is worth $8.55. The stock is now worth $58.42, a difference of $8.42. On the other hand, simply selling the call option for $8.55 and buying the stock at $58.42 results in collecting the $0.13 in time value and coming out $0.13 ahead.

The one important exception is when a dividend is looming. In this situation it makes sense for the owner of the call option to exercise it early if the amount of the dividend he’ll collect is greater than the time value of the option.

In this situation, as shown in Table 10.15 for the HGIJ Corporation, it would seem the likelihood of early assignment is remote since there’s the possibility that the stock would drop back below $55 before expiration and because the option has time value. If the owner of the call option exercised his 55 call he’d buy the stock at $55 but no longer have his option. He would have paid $55 plus the $7.15 option price, or $62.15, for stock worth $62.11. By exercising his call he’s abandoned the luxury of waiting. Why would anyone do this by exercising early?

Table 10.15 Dividends and Early Assignment of Call Options

| HGIJ Corp. Last Trade 62.11 | ||

| Bid Price | Ask Price | |

| June 55 Call Option | 7.15 | 7.20 |

| A Dividend of 1.00 Is Due to be Paid to Those Who Own the Stock Tomorrow |

Because the owner of the stock collects the $1 dividend that’s due to be paid, while the owner of the call option does not.

The owner of the call option has three alternatives:

What should this call owner do?

If he holds the option, which is the first alternative, his position is unchanged, but tomorrow the stock will go ex-dividend, meaning an owner is no longer entitled to the $1.00 per share. The $1.00 dividend is deducted from the stock price. The stock will open tomorrow at $61.11 and the call option will open at $6.15. Simply staying long the option will have cost the owner of the call option $100.

If the owner of the option exercises early and pays the 55 strike price for HGIJ, which is the second alternative, he loses the $7.15 value of the option and essentially purchases the stock at $62.15 (the 55 strike price plus the $7.15 option value). When the stock opens ex-dividend tomorrow the owner will see the stock drop to $61.11, but he will receive the $1.00 per-share dividend and he will have stock and cash worth $62.11. The owner of the call will have lost the $0.04 in time value, but that’s better than losing the $1.00 that would have been lost if nothing had been done, and so the owner is better off exercising the option early rather than holding it.

The third alternative is selling the option and buying stock. Since the option is trading for $0.04 over its inherent value the result of selling the option and buying the stock is nearly identical to the second alternative, which is early exercise. Again, the owner of the call won’t have come out very much ahead but he won’t have lost anything either.

The result of a looming dividend is that early exercise of in-the-money call options is a very real possibility, particularly if they’re trading for just their inherent value or if the time value remaining is less than the amount of the dividend. If having your stock called away would be a real burden, then paying attention to dividend timing is an important element in the likelihood of early exercise.

ROLLING

Rolling your covered call to another strike and potentially to another expiration is how traders take advantage of the opportunity to make a smarter, better informed trade as more information becomes available. In the case of rolling up, it will cost some of the premium previously received, but will reduce the likelihood of having our stock called away. In the case of rolling down it will generate additional premium at the cost of being short a lower strike price and thus having a greater chance of being called away. In the case of rolling up and out it will reduce the likelihood of having stock called away without surrendering any of the premium initially received but resets some of the option math against us.

Even though you always have the right to make a better-informed trade, good traders know that just wanting to trade isn’t a good enough reason to make a follow-up trade. In determining whether to roll and how to roll, discipline and a little steely-eyed analysis is necessary.

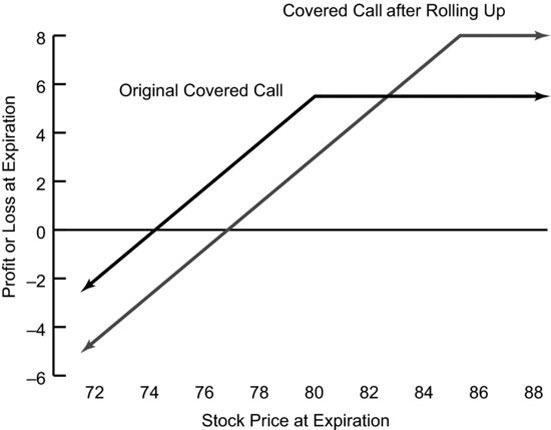

Rolling Up

The covered call writer expects the stock he owns to trade sideways or appreciate slightly. If he thought it was going to turn lower he would likely sell the stock or look for another strategy that provides more protection than a covered call. As we’ve seen, if the stock rallies slightly this is the best of all possible worlds for the covered call writer. He can make a little bit on the stock and make all of the premium received for selling the call. On the other hand, if the stock is now near the strike price with the potential to be above the strike price at expiration, or if the stock rallies sharply, our covered call seller might want to take some action to be certain to keep the stock. The most straightforward trade would be to buy back the call, but that causes certain problems as we’ve discussed, including buying an option just as the daily erosion reaches its maximum point.

Another strategy is to roll the strike price up. In rolling up, call sellers buy back the call option they are short and sell another call option with the same expiration date but with a higher strike price.

For example, if our covered call seller was long 100 shares of PQR Corporation, which was trading at $77.50, and sold the 80 call option for $3, the downside breakeven would be $74.50 and the regret point would be $83.00. The maximum profit would be $5.50, $2.50 on the stock the option seller is long and $3.00 on the call the option seller is short. This maximum profit would be realized with PQR at or above $80 at expiration. Inside the range of $74.50 to $83.00 he is better off having sold the covered call but if PQR is above 80 at expiration he’s going to have his stock called away.

If PQR is at $80 with two weeks to expiration our covered call seller may want to take some action to reduce the likelihood of seeing the stock called away and might decide to roll the 80 call up to a higher strike price with the same expiration.

With PQR at $80 the 80 call might now cost $4.00 and the 85 call might cost $1.50. The covered call writer can roll up by buying back the 80 call at $4.00 and selling the 85 call at $1.50. In buying the 80 call and selling the 85 call, the covered call writer has bought the 80/85 call spread.

Now PQR must be above $85 at expiration in order for the stock to be called away. Rolling up will cost $2.50 ($4.00 − $1.50). Rolling up will always cost money as the lower strike call, the call option our trader is buying back, will always cost more than the higher strike call, the call option the trader sells and ends up short. Rolling up should always be executed as a spread, buying the lower strike call and selling the higher strike call, for the reasons we discussed in Part Two.

If PQR is at or above $85 at expiration, the profit on the entire position would now be $8.00.

Covered call sellers in this position would have both increased the maximum profit and raised the price at which they were called away. How?

These traders would have increased the maximum profit while simultaneously raising the price at which they’re called away in two ways, first by raising the downside breakeven point such that the stock only has to fall to $77.00 to reach breakeven and thus increasing the likelihood it’s reached, and second, by raising the level at which the maximum profit is achieved and thus reducing the likelihood that it’s reached. In this case it’s raised from $80 to $85 meaning PQR stock now has to rally further, to $85.00, to achieve this maximum profit.

The downside breakeven is always raised by the amount spent to roll up. In this case the 80/85 call spread our trader bought cost $2.50, so the downside breakeven is raised by $2.50, from $74.50 to $77.00. Table 10.16 shows the rolling up data we’ve tracked for the PQR Corporation.

Table 10.16 Rolling Up

| Initial Covered Call | |

| PQR Price | 77.50 |

| Call Strike Price | 80 |

| Call Premium Received | 3.00 |

| Downside Breakeven Point | 74.50 |

| Upside Regret Point | 83.00 |

| After PQR Rises to 80.00 | |

| Follow-up Trade | Buy 80/85 Call Spread to Roll Up |

| Premium Paid | 2.50 |

| Total Premium Received | 0.50 |

| New Downside Breakeven Point | 77.00 |

| New Upside Regret Point | 85.50 |

Figure 10.7 shows the risk/reward for the original position and the risk/reward for the position after it has been rolled up.

FIGURE 10.7 Original Covered Call and Rolled Up

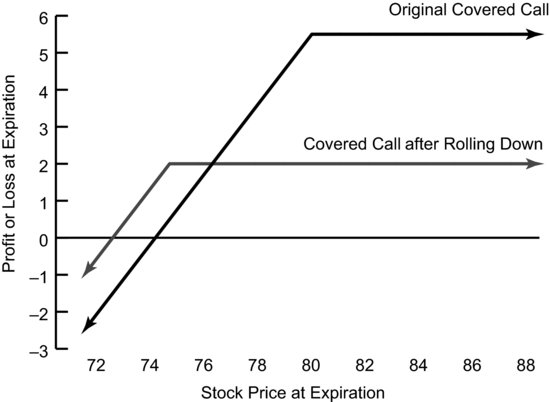

Rolling Down

Since smart covered call writers only write calls on stocks that they already own and therefore like, having the stock drop after selling the call is likely to be a bit of a surprise. They expected the stock to trade sideways for some time, at least until option expiration. If they’d thought the stock was likely to head lower, they would have sold the stock and/or established a bearish option position.

When the stock does head lower the subsequent decrease in the value of the call option will cushion some of the loss, but since we don’t sell covered calls for their insurance virtues, this is small comfort. So, if the stock drops should the option trader take follow-up action?

The initial covered call position had a range in which it realized a profit. That range was from the regret point of $83.00 down to the breakeven point of $74.50. Above the regret point it starts to forgo additional profit. Below the breakeven point it is a net loser. This being the case, limited return potential and risk all the way down to a stock price of zero, it’s important to not let a covered call position experience a huge loss.

A covered call position has the added complication in that traders can’t simply sell the stock if it drops. This would leave them naked short the call, a position that has to be avoided. This means that covered call sellers need to examine alternatives if the stock drops. They don’t have to do anything, but they should examine what strategies they might use to make a better, more informed trade.

Covered call sellers have more information than they had when they initially executed their call sale. They have to use this information; they can be assured that other market participants are using this information to inform their trades. Again, it doesn’t mean that covered call sellers have to take any action, it simply means that the action they do take will be better informed than the original trade.

One follow-up trade if the stock has dropped is to roll the covered call down. In rolling down, traders buy back the call option they are short and sell an option with the same expiration, but with a lower strike price.

For example, our covered call seller is long 100 shares of PQR Corporation, which is trading at $77.50, and has sold the 80 call option for $3. The downside breakeven is $74.50. The regret point is $83.00. Table 10.17 shows the initial PQR covered call and the result of rolling down.

Table 10.17 Rolling Down

| Initial Covered Call | |

| PQR Price | 77.50 |

| Call Strike Price | 80 |

| Call Premium Received | 3.00 |

| Downside Breakeven | 74.50 |

| Upside Regret Point | 83.00 |

| After PQR Falls to 73.00 | |

| Follow-Up Trade | Sell 75/80 Call Spread to Roll Down |

| Additional Premium Received | 2.00 |

| Total Premium Received | 5.00 |

| New Downside Breakeven | 72.50 |

| New Upside Regret Point | 80.00 |

If PQR falls to $73.00 with two weeks to expiration, our trader is facing a loss of $1.50. Traders in this situation might use this new information along with any other data gleaned during this period and decide that they’re less certain of PQR’s prospects going forward. As such, they might demand an additional call premium and might be more willing to have their stock called away. This being the case, they decide to roll down the 80 call.

With PQR now at $73.00, the 80 call might be worth $0.50 (implied volatility has likely increased, as the entire skew curve has ridden the volatility slope higher; if it hadn’t this call would be worth even less). The 75 call might now be worth $2.50. In order to roll down, traders would buy back the 80 call they’re short and sell a 75 call. This trade, selling the 75/80 call spread, which should be executed as a spread for the reasons discussed in Part Two, would generate a premium credit of $2.00 ($2.50 − $0.50). Rolling down will always generate a credit, since the call option sold will cost more than the call option bought back.

The breakeven point for this trade is now $72.50, which is below the current stock price. The new breakeven point for a rolled down covered call is always the original breakeven point minus the additional premium received.

The new regret point is $80.00.

The new maximum profit now occurs at $75.00, again we see the maximum profit occur with the stock price at the short strike At this point the maximum profit is $2.50, which represents the $5.00 in total option premium received less the $2.50 loss on PQR stock as it fell from $77.50 to $75.00. Rolling down has lowered the breakeven point, but it has also lowered the regret point.

Figure 10.8 shows the profit profile for the original trade as well as the trade after it’s been rolled down.

FIGURE 10.8 Original Covered Call and Rolled Down Covered Call

Rolling down may be the right solution, but it subjects the trader to being constantly whipsawed and drastically increases the likelihood of getting called away. This may be okay for traders if the drop in price has made them reconsider ownership of this stock, but it may simply result in selling a good stock near a temporary low.

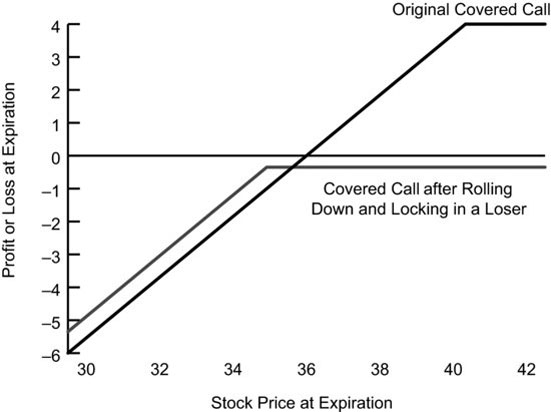

Locking In a Loser

If a stock has dropped enough, rolling down will reduce the maximum profit so much that the maximum profit is actually a loss. There will be no price for the underlying stock at option expiration that will generate a profit. The covered call seller would have locked in a loss.

For example, our covered call writer is long FED Incorporated, which is currently trading at $38.00, and might decide to sell the 40 strike call for $2.00. The downside breakeven point is 36.00 and the regret point is 42.00. Table 10.18 describes locking in a loser in FED.

Table 10.18 Locking in a Loser

| Initial Covered Call | |

| FED Price | 38.00 |

| Call Strike Price | 40 |

| Call Premium Received | 2.00 |

| Downside Breakeven | 36.00 |

| Upside Regret Point | 42.00 |

| After FED Falls to 33.00 | |

| Follow-Up Trade | Sell 35/40 Call Spread to Roll Down |

| Additional Premium Received | 0.65 |

| Total Premium Received | 2.65 |

| New Downside Breakeven | None—Locked-In Loss |

| New Upside Regret Point | 37.65 |

If, after selling the covered call, FED drops to 33.00, our covered call seller might decide to roll down. In this case the 35 call might now be worth $0.75, while the 40 call might now be worth $0.10. If traders choose to roll down in this situation they will sell the 35/40 call spread by selling the 35 call at $0.75 and paying $0.10 to buy back the 40 call. They must buy back the 40 call; they can’t simply sell the 35 call because that would leave them naked a call. These covered call sellers would receive an additional $0.65 for selling this 35/40 call spread.

But the result is that these traders have now guaranteed themselves a loss. If FED is at or above 35 at option expiration, they will have their stock called away at a loss of $3.00 ($38.00 − $35.00). This will only partially be offset by the $2.65 received in option premium ($2.00+$0.65). The very best these traders can do on this trade is a loss of $0.35. They have locked in a loser.

Figure 10.9 shows the initial trade and the position after the trader has locked in a loser.

FIGURE 10.9 Locking in a Loser

Locking in a loser sounds painful and it is, but that doesn’t mean it’s the wrong trade. If our trader has reevaluated FED Inc. and is determined not to own it any longer, then rolling down, even if it means locking in a loser, may be the best course of action. The traders rolling down because they don’t want to own the stock any longer need to be mindful of two caveats.

Rolling down, even rolling down and locking in a loser, doesn’t guarantee getting your stock called away. Don’t think of rolling down as the same thing as selling your stock. Selling an at-the-money call certainly increases the likelihood of getting called away, but it’s entirely possible for the stock to keep dropping and for it to be below the new strike price at expiration. If that happens covered call sellers will continue to own a stock they might not want to own. In these situations they might be better to simply buy back their call option and sell the stock outright.

Second, selling covered call options has limited utility as a vehicle for stock rehabilitation. If your stock is trading below your purchase price, then you might sell covered calls to make back the unrealized loss and hope to have the stock called away. This only works if the stock is within a reasonable distance of the initial purchase price. If you are deeply under water on the stock then the limited income generated by covered calls is unlikely to get you back to even. Again, there’s no assurance that the stock won’t continue to drop. In this case the loss compounds and you would have been better off buying back your covered call and selling the stock outright.

Rolling Up and Out

One reason that some traders hesitate to roll a covered call up is the requirement to pay premium to buy the call spread. Some hate to take premium they think they’ve already earned and pay it back out. This is the wrong outlook, as the premium isn’t earned until the call has expired, but there is a way to reduce the likelihood of being called away without paying for a spread. The way to accomplish this is to roll up and out. In rolling up and out, traders buy back the call option they are short while simultaneously selling another call with a higher strike price and more time to expiration. The goal is generally to use the additional time to expiration of the call option being sold so that the spread can be done for no additional premium.

For example, in our rolling-up example in Table 10.16, PQR was trading at $77.50 and our covered call seller sold the 80 call for $3.00. The regret point was $83.00. PQR rallied to $80 with two weeks to option expiration. A trader wanting to roll up might pay $2.50 to buy the 80/85 call spread, but that $2.50 would reduce the potential profit if PQR didn’t rally any further.

Another strategy would be to roll up and out in time by buying back the 80 call with 2 weeks to expiration and selling the 85 call with 6 weeks to expiration. You would be able to do this for no net premium if the 6-week 85 call is trading for the same $4.00 you have to pay for the 2-week 80 call. (See Table 10.19.)

Table 10.19 Rolling Up and Out

| Initial Covered Call | |

| PQR Price | 77.50 |

| Call Strike Price | 80 |

| Call Premium Received | 3.00 |

| Downside Breakeven Point | 74.50 |

| Upside Regret Point | 83.00 |

| After PQR Rises to 80.00 | |

| Follow-Up Trade | Buy 80 Call with 2 Weeks to Expiration / Sell 85 Call with 6 Weeks to Expiration |

| Premium Paid | 0.00 |

| Total Premium Received | 3.00 |

| New Downside Breakeven Point | 74.50 |

| New Upside Regret Point | 88.00 |

Rolling up and out increases the regret point—it’s now the new strike price plus the total premium received—but also extends the time the trader will be short the covered call. If the trader is rolling up and out because the stock is rallying, then it may simply delay the inevitable assignment.

Rolling up and out also resets the option math against the call seller. As we’ve seen, short-dated options like the original 2-week option erode more quickly than the new 6-week option. Despite having different strike prices, traders who roll up and out are paying more for each day in the option they’re buying back than they’re collecting for each day in the new option they’re selling. This is the most convincing argument against rolling up and out, but that doesn’t mean it should never be done, just that it should be done carefully.

In this example the call seller is able to roll up and out for no net premium, but the daily erosion of the new option is about half that of the old option. This is the cost for increasing the strike price at which the stock is called. Unfortunately, this also means we’ve raised the price at which the maximum profit occurs and we’ve increased the regret point. Table 10.20 shows data for the daily erosion (theta) after rolling up and out.

Table 10.20 Daily Erosion After Rolling Up and Out

| Option Price | Daily Erosion (Theta) | |

| Stock Price 80.00 | ||

| 80 Strike Call with 2 Weeks to Expiration | 3.00 | 0.109 |

| 85 Strike Call with 6 Weeks to Expiration | 3.00 | 0.059 |

Since our trader initially sold the covered call based on the thought that the underlying stock was stuck in neutral for some time, rolling up and out may make sense because it can allow the rally to run out of steam. But since traders often write covered calls on a stock they like to begin with, maybe a rally is simply a manifestation of all the reasons they liked the stock.

- Return if the underlying stock doesn’t move during the term of the option.

- Return if the underlying stock is called away.

- The yield from selling the call.

- The option math and how successful option selling favors at-the-money, shorter-dated options (although that doesn’t require selling the short-dated, at-the-money option).

- Using the bid/ask spread to our advantage in illiquid options.

- Getting called away isn’t a defeat, particularly if we’ve sold our stock at a big profit.

- We’re trying to collect the volatility risk premium.

- We make our money when we sell the call, and we collect it through the daily price erosion, so try to sell shorter-dated options that maximize theta.

- We always have the right to execute a more informed follow-up trade.