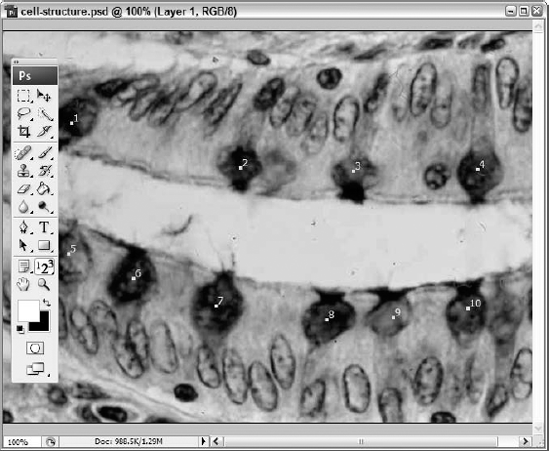

The colored pixels that make up an image work much like the tiles in a mosaic. When you view a mosaic up close, you may not be able to tell what the overall image is supposed to be — move far enough away, however, and the mosaic's tiles blend together to make a complete image. If you enlarge the pixels in an image in Photoshop, they look like an unrelated collection of colored squares. Reduce the size of the pixels, and they blend together to form an image that looks like a standard photograph. Photoshop deceives the eye, counting on the distance that printing or normal onscreen viewing puts between the person's eye and the image pixels, and in most cases, the deception works quite well.

Of course, there are differences between pixels and mosaic tiles. Pixels come in 16 million distinct colors. Also, you can resample, color separate, and crop electronic images, often working at a very zoomed-in, you-can-see-the-individual-pixels level. Luckily, you can get extremely close to the image to make changes that have a very subtle impact when viewed at that aforementioned eye-deceiving distance.

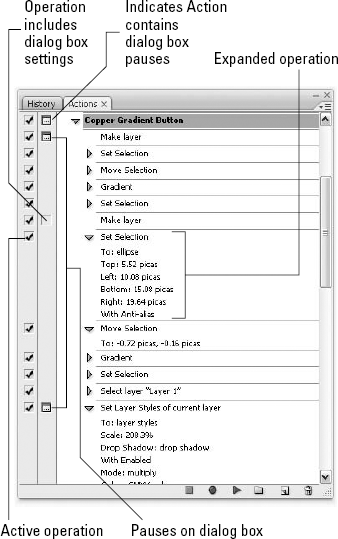

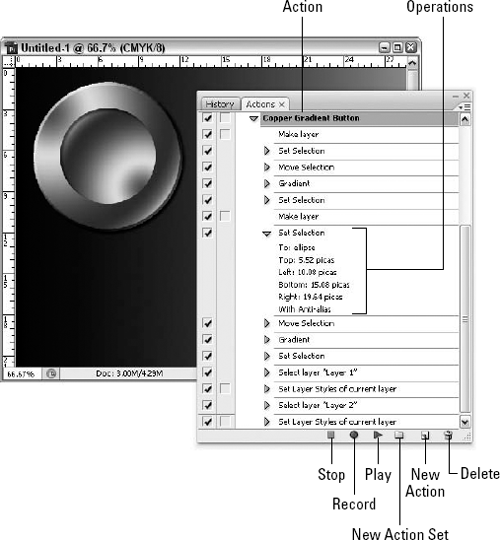

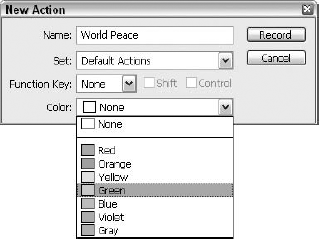

In this chapter, you learn about how images are constructed, how to change their resolution, how to crop out what you don't want, how to save your files (including an exhaustive discussion of file formats and choosing the right ones for the way your files will be used), and ways to better organize and view your saved images. You also learn about automating the use of Photoshop, finding out more about actions and how you can use them to record often-performed and/or complex tasks over and over again, with the press of a button or the click of an icon.

If you haven't already guessed, the term image size describes the physical dimensions of an image. Resolution is the number of pixels per linear inch in the final printed image. The term linear is used because you measure pixels in a straight line. If the resolution of an image is 72 ppi — that is, pixels per inch — you get 5,184 pixels per square inch (72 pixels wide × 72 pixels tall = 5,184).

Assuming the number of pixels in an image is fixed, increasing the size of an image decreases its resolution, and vice versa. An image that looks good when printed on a postage stamp, therefore, probably looks jagged when printed as an 11×17-inch poster.

Figure 3.1 shows a single image printed at three different sizes and resolutions. The smallest image is printed at twice the resolution of the medium-sized image; the medium-sized image is printed at twice the resolution of the largest image.

Figure 3.1. These three images contain the same number of pixels but are printed at different resolutions. Doubling the resolution of an image reduces it to 25 percent of its original size.

One inch in the smallest image includes twice as many pixels vertically and twice as many pixels horizontally as an inch in the medium-sized image, for a total of four times as many pixels per square inch. Therefore, the smallest image covers one-fourth the area of the medium-sized image.

The same relationships exist between the medium-sized image and the largest image. An inch in the medium-sized image comprises four times as many pixels as an inch in the largest image. Consequently, the medium-sized image consumes one-fourth the area of the largest image.

When printing an image, a higher resolution translates to a sharper image with greater clarity. Photoshop lets you change the resolution of a printed image in one of two ways:

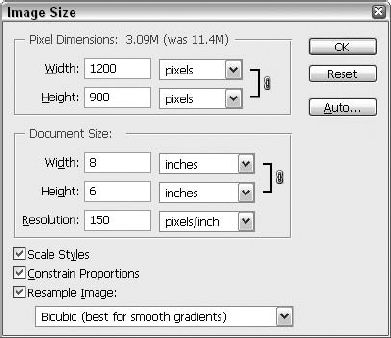

Choose Image

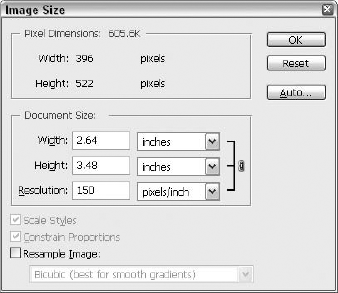

A good idea (although not essential) is to deselect the Resample Image option, as demonstrated in Figure 3.2. If you leave it selected, Photoshop may add or subtract pixels, as discussed later in this chapter. Of course, if you're shrinking an image for posting on the Web, resampling the image is necessary. For non-Web images, deselecting resampling instructs Photoshop to leave the pixels intact but change how many of them print per inch. This is especially important when going from a lower resolution to a higher one.

Alternatively, you can ask Photoshop to scale an image during the print cycle. You hand down this edict with the Print command. Choose File

Photoshop saves the Resolution setting with the image; the scale settings in the Print dialog box affect only the current print job. Together, the two determine the printed resolution. Photoshop divides the Resolution value in the Image Size dialog box by the Scale percentage from the Print dialog box. For example, if the image resolution is set to 72 ppi and you reduce the image to 48 percent, the final printed image has a resolution of 150 ppi (72 divided by 0.48).

Note

With apologies to the non-mathematically inclined readers out there, it's important to remind you that whenever you use a percentage in an equation, you first convert it to a decimal. For example, 100 percent is 1.0, 64 percent is 0.64, and 5 percent is 0.05. This little tip can help you make sense of the discussions of image size, resolution, and so on throughout this chapter and the rest of the book.

Tip

To avoid confusion, most people rely exclusively on the Resolution value and leave the Print dialog box Scale value set to 100 percent. The only exception is when printing tests and proofs. Because inkjet and other consumer printers offer lower-resolution output than high-end commercial devices, you may find it helpful to proof larger images so that you can see more pixels. Raising the Scale value lets you accomplish this without upsetting the Resolution value. Just be sure to restore the value to 100 percent after you make your test print.

Note

When you view the list of Resample Image options in the Image Size dialog box, you now get tips as to which resampling method might work best for your current image or goals for resizing it. For example, you are reminded that Bicubic resampling works well for smooth gradients, while Bicubic Smoother is your best choice if you're enlarging an image.

The Scale value in the Print dialog box value has no effect on the size and resolution of an image imported into an object-oriented application, such as QuarkXPress or Illustrator. But these same applications do observe the Resolution setting from the Image Size dialog box.

Specifying the resolution in Photoshop is a handy way to avoid resizing operations and printing complications in your page-layout program. For example, when images were created for this book, their resolution was preset so the production team had only to import the images in preparation for the printing process.

Photoshop is as good as or better than any other program at adjusting pixels. It's a good idea, therefore, to take advantage of its considerable powers and prepare your images as completely as possible in Photoshop before importing them into another program.

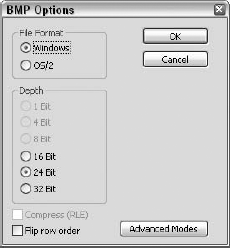

After all this explanation of pixels and resolution, you may still be wondering what the best resolution would be for any image — images that will be printed, displayed onscreen, or both. The answer is a frustrating "non-answer" to some and a liberating "whatever you want!" to others: The resolution is entirely up to you, and there's no hard and fast rule. You're best off using the highest resolution possible, of course, because the higher the resolution, the cleaner, crisper, and more detailed the image is, but there are no absolute right answers. The images in this book vary from 150 ppi for figures that show black-and-white images, dialog boxes, and other parts of the workspace to 300 ppi for the images that appear in color. Now, despite the lack of an established rule for determining resolution, here's a little help to assist you in making effective choices for your images:

Most experts recommend that you set the Resolution value to somewhere between 150 percent and 200 percent of the screen frequency of the final output device. The screen frequency is the number of halftone dots per linear inch, measured in lpi (short for lines per inch). So ask your commercial printer what screen frequency he uses — generally 120 lpi to 150 lpi — and multiply that times 1.5 or 2.

More specifically, for high-end photographic print work, it's hard to go wrong with the standard Resolution value of 267 ppi. That's around 200 percent of 133 lpi, arguably the most popular screen frequency. When in doubt, most professionals aim for 267 ppi.

If you're printing on a home or small-office printer, the rules change slightly. Different manufacturers recommend different optimum resolutions for their various models, but the average is 250 to 300 ppi. Experiment to see how low you can go, though — sometimes you can get by with fewer pixels than the manufacturer suggests. And don't forget that the quality of the paper you use may be more to blame than a lack of pixels for a lousy print — copier-quality paper absorbs the ink and colors, and detail can be lost to that. You want bright white paper that won't suck up all the ink. Most papers you can buy at the office-supply store or printer will be marked clearly as to what kind of printing they're best used for — photos, brochures, flyers, informal publications, and so on.

What if you don't have enough pixels for 267 ppi? Say that you shoot a digital photograph that measures 768×1024 pixels and you want to print it at 6×8 inches. That works out to a measly 128 ppi. Won't that look grainy? Probably. Should you add pixels with Image Size or some other command? No, that typically won't help. You have a finite number of pixels to work with, so you can print the image large and a little grainy, or sharp and small. The choice is yours.

What if you have a photograph or slide and you can scan it at any resolution you want? Flatbed scanners typically offer two maximum resolutions: a true optical maximum and an interpolated digital enhancement. The lower of the two values is invariably the true optical resolution. Scan at this lower maximum setting. Then use Image

Finally, just take the pixels you have and try to make them look the best you can. Then print the image at the size you want it to appear, or for images that will be viewed solely online or onscreen, make sure they look good on the monitor and leave it at that — the Save for Web dialog box (discussed later in this chapter and again in Chapter 20) can help you make sure your image is both visually appealing and browser-friendly in terms of fast-loading for your onsite patrons. Overall, if you focus on the function of your image first and worry about resolution and other technical issues second, you'll produce better art.

Tip

While it's often a case of making the best of what you've got, you can improve images prior to printing and onscreen display. Check out Chapters 10, 11, and 12 for ideas on using filters to blur, sharpen, and otherwise manipulate your image content — from subtle changes that smooth out noise and graininess to others that apply fancy-schmancy artistic effects, some of which can creatively mask a low-resolution, otherwise shabby-looking image.

Regardless of the Resolution and Scale values, Photoshop displays each pixel onscreen according to the zoom ratio (covered in Chapter 2). If the zoom ratio is 100 percent, for example, each image pixel takes up a single screen pixel. Zoom ratio and printer output are unrelated.

This same rule applies outside Photoshop as well. Other programs that display screen images — including multimedia development applications, presentation programs, and Web browsers — default to showing one image pixel for every screen pixel. This means that when you're creating an image for the screen, the Resolution value has limited impact. Some people might recommend that screen images should be set to 72 ppi on the Mac or 96 ppi for Windows, and while there's nothing wrong with doing this, anything at or over 72 ppi should be fine, considering that the load time is king when it comes to Web images — unlike print, where the image quality is primary. On the Web, you want the image to look good, but to load fast — even if that means sacrificing image quality somewhat.

When publishing for the screen, just scan or capture at a high resolution — 300 ppi or more — make your corrections, retouches, edits, and so on — and then use the Save for Web dialog box to optimize the image for the Web. The dialog box contains a preview that lets you choose the right format, quality, and color range, and the software does the work of setting the resolution for you. You also get a load-time estimate so you can decide whether you want to sacrifice some of the clarity in order for your image to load in under a minute. The Save for Web dialog box is discussed later in this chapter, and also in Chapter 20.

So, in the end, all that counts is the 100 percent view. That means you want the image to fit inside the prospective monitor when you choose View

Believe it or not, before you can work on an image in Photoshop — whether you're creating a brand-new document or opening an image from disk — you must first load the image into an image window. Here are the basic ways to create an image window:

File

New: Create a new window by choosing File

Note

If you opt to choose Transparent or Background Color from the Background Contents drop list, you'll either see a dim checkerboard effect or the currently-selected background color (see the toolbox for what's currently chosen).

File

Open: Choose File

File

Browse: This command opens the Bridge, a separate workspace that allows you to organize and print your images.

Note

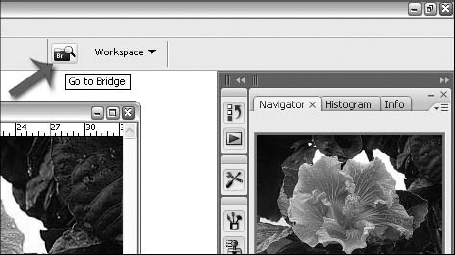

You also can open the Bridge by clicking the Go To Bridge button (found just to the left of the Workspace drop list on the Options bar). The Bridge is discussed later in this chapter and also in Chapter 20.

File

Open Recent: A variation on the Open command, Open Recent displays a list of the images that you recently opened. Click an image name to crack open the image file without taking that tedious trip to the Open dialog box. You can set the number of files that you want to appear in this list in the File Handling panel of the Preferences dialog box.

Edit

Paste: Photoshop automatically adapts a new image window to the contents of the Clipboard (provided that those contents are bitmapped). So if you copy an image in a different application or in Photoshop and then choose File

File

Import: This command's submenu, as it relates to opening images, includes commands for opening a digital camera image, grabbing an image from your scanner, or bringing in video frames as layers. Typically, if you have a scanner or camera, your installation of that device (for using the device with your computer) has made Photoshop "aware" of the device and enabled it to support it. You also may have to deal with the device's plug-in module, which lets you transfer an image directly into Photoshop. Just copy the module into Photoshop's Plug-Ins folder and then run or relaunch the Photoshop application. To initiate a scan or to load an image into Photoshop, choose the already set-up scanner from the File

After you choose the command, Photoshop launches the device's download software. If you're scanning, select the scanner settings and initiate the scan as usual; the scanned picture appears in a new image window in Photoshop. If you're transferring images from a digital camera, the camera software typically creates thumbnail previews of images in the camera's memory so that you can select the ones you want to transfer to Photoshop. If you're bringing in video frames to be viewed as layers in an image, you are presented with a dialog box through which you can choose the video file and the frames within that video for import.

Tip

Save your images to disk immediately after you scan or download them; unlike some other programs, Photoshop doesn't automatically take this step for you. Also, if your digital camera stores images on removable memory cards (CompactFlash, SmartMedia, Memory Stick, and the like), it's a good idea to invest in a card reader or adapter that enables your computer to see the memory card as just another hard drive — if your computer didn't already come with a built in reader. You can then just drag and drop images from the memory card to your computer's hard drive, a process that, depending on your camera, may be much faster and more convenient than transferring images using a cable connection.

Note

Open as Smart Object is another command on the File menu, and it does two jobs. It opens an image, but it also opens it as a Smart Object, which prepares the image for use with Smart Filters, among other benefits. Find out more about Smart Objects as they relate to Blend Modes in Chapter 14 and as they relate to Filters in Chapter 10.

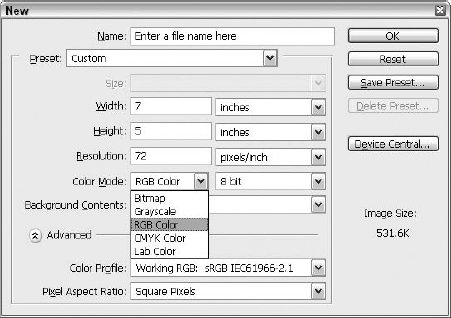

Whether you're creating an image from scratch or transferring the contents of the Clipboard to a new image window, choose File

Figure 3.4. Use the New dialog box to specify the size, resolution, and color mode of your new image. You can even give the file a name at this stage, if you want.

Tip

When in doubt about the size of your new image, go for bigger rather than smaller. If you have a general sense that the image needs to print at 3 inches by 4 inches, go for 4 inches by 5 inches, or even use one of the preset sizes, such as 4×6. You can always crop away unwanted periphery, and it's better to have too much room than not enough.

The Preset pop-up menu gives you easy access to several popular document sizes, common settings for working in print or on the Web, and several presets for video and film formats such as NTSC, PAL, and HDTV. Photoshop also lets you select the pixel aspect ratio of your document. You find more information about pixel aspect ratios later in this chapter.

Tip

You also have the New Document Preset Resolutions settings in the Units & Rulers panel of the Preferences dialog box, which let you set a default resolution for print or screen; the resolutions you set in the Preferences dialog box appear when you select certain options from the Preset menu.

Note

When you select one of the video presets from the Preset pop-up menu, Photoshop automatically adds guides to your image that are specific to that setting. These guides delineate areas known in the video industry as the action-safe and title-safe zones. Because most television screens crop a certain amount off the borders of a video image, it's extremely helpful to be aware of what will and won't be visible on any given television set. These days, you'll be safe on most televisions if you keep your graphics within the outermost, or action-safe, zone. You can quickly toggle the visibility of these guides on and off by pressing Ctrl+; (semicolon) (

Note

Device Central, represented by a button in the New dialog box as well as the File menu (File

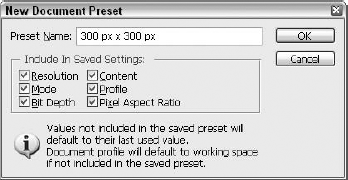

If you don't like Photoshop's preset document sizes, you can easily create your own. The moment you make any sort of change to one of Photoshop CS3's predefined presets, you get access to the Save Preset button. Click it to open the New Document Preset dialog box, shown in Figure 3.5. Here you can type a name for the new preset and specify which of your current settings you'd like to include. This is a great feature that can be a huge timesaver when you're creating a large batch of identically sized files. If you later decide that you want to delete a custom document preset, simply select it from the Preset pop-up menu in the New dialog box and click Delete Preset.

Figure 3.5. The New Document Preset dialog box lets you name and save custom document presets for future convenient use.

The Width and Height pop-up menus contain the six common units of measure mentioned earlier: pixels, inches, centimeters, millimeters, points, and picas. But the Width pop-up menu offers one more: Columns. If you want to create an image that fits exactly within a certain number of columns when it's imported into a desktop-publishing program, select this option. You can specify the width of a column and the gutter between columns by pressing Ctrl+K and Ctrl+6 (

The Gutter value affects multiple-column images. For example, if you accept the default setting of a 15-pica column width and a 1-pica gutter, and you specify a one-column image in the New dialog box, Photoshop makes it 15 picas wide. If you ask for a two-column image, Photoshop adds the width of the gutter to the width of the two columns and creates an image 31 picas wide.

The Height pop-up menu in the New dialog box lacks a Column option because vertical columns have nothing to do with the image height.

In most cases, the onscreen dimensions of an image depend on your entries in the Width, Height, and Resolution option boxes. If you set both the Width and Height values to 10 inches and the Resolution to 72 ppi, the new image measures 720×720 pixels. An exception occurs if you choose pixels as your unit of measurement. In this case, the onscreen dimensions depend solely on the Width and Height options, and the Resolution value only determines the size at which the image prints.

Use the Color Mode pop-up menu to specify the number of colors that can appear in your image. Choose Bitmap to create an image consisting of only black and white pixels, and choose Grayscale to access only gray values. RGB Color, CMYK Color, and Lab Color all provide access to a full range of colors, although their methods of doing so differ. You can read all about these color modes and how they work in Chapters 4, 17, and 18.

In addition to specifying the color mode, Photoshop lets you set the bit depth of your image in the New dialog box. The bit depth determines the amount of color information available to each individual pixel in the image. Choosing 1 bit limits your image to black and white pixels and thus can be used only in Bitmap mode. The option you'll probably use most often is 8 bit, which is standard fare for most full-color images. Choosing 16 bit gives your image a much greater number of available colors, providing you with a more accurate color representation and finer color controls. But the 16-bit option also greatly increases the file size and limits your editing options. For more information on using 16-bit mode, see Chapter 4, where you also can read about taking an existing image and bumping it up to 32-bit mode, using the Image

Note

RGB stands for red-green-blue, CMYK for cyan-magenta-yellow-black, and Lab for luminosity and two abstract color variables: a and b. To learn how each of these color modes work, read Chapter 4.

The New dialog box also provides a Background Contents pop-up menu that enables you to change the color of the background for the new image. You can fill the new image with white, with the current background color (which may be white anyway, of course), or with no color at all. This last setting, Transparent, results in a floating layer with no background image whatsoever (represented by a gray and white checkerboard pattern), which can be useful when editing one layer independently of the rest of an image or when preparing a layer to be composited with an image. For an in-depth examination of layering, see Chapter 13.

If you do select a transparent background, you must later flatten the layers if you want to save the image to a format that doesn't support layers. (See the upcoming discussion on saving an image to disk for information about options that retain layers when saving.) The advantage of the Transparent setting, however, is that Photoshop doesn't create a new layer when you press Ctrl+V (

At the very bottom of the New dialog box, you find an Advanced option (click the button to the left of the word Advanced). The Advanced settings offer options for selecting a Color Profile and the Pixel Aspect Ratio for your image.

In the first option, Color Profile, you can determine the color space in which your new image will exist. Essentially, the color profile of an image provides the information necessary to make sense of how an image should be displayed or printed based on the circumstances under which the image was created. For an in-depth look at the sometimes daunting world of color management, check out Chapter 17.

The second and final setting in the Advanced section of the New dialog box lets you set the Pixel Aspect Ratio for your image. Computer monitors display images with an assortment of perfectly square pixels. The pixels that make up an image on a television, however, are of a more rectangular nature. The result is that an image created with square pixels in Photoshop looks somewhat squashed when imported into video-editing software and output onto a television screen.

Luckily, Photoshop can help. By selecting a non-square pixel aspect ratio or choosing any of the non-square video presets, you can work with a preview of the image that more accurately represents its appearance in your final film or video project. It's important to note, however, that these settings don't actually alter the pixels in your image. They simply present them to you in a way that more closely matches your specific destination. You always have the option of displaying the pixels in a square ratio by choosing View

Tip

If you decide to change the pixel aspect ratio of an image after you've begun to edit it, simply choose Image

Note

It's important to note that choosing a non-square aspect ratio affects the behavior of many tools. For example, if you Shift-drag with the Elliptical Marquee tool to draw a circular selection outline, a different number of pixels are selected depending on whether you're working with square or non-square pixels. This pertains to all shape tools and even brushes. A 90-pixel circular brush used on an NTSC image, for example, paints a circle 90 pixels tall and 100 pixels wide.

Photoshop provides a File menu command, Open Recent, which displays a list of the images you worked on in recent Photoshop sessions. Click the name of the image you want to open. You set the number of files that appear on the list by typing a value in the Recent File List Contains option box, found on the File Handling panel of the Preferences dialog box, which you access by pressing Ctrl+K and then Ctrl+3 (

Tip

Some tricks for Mac people:

Also, the icon in the title bar gives you an instant hint as to whether your image has been edited since it was last saved. If the image has unsaved changes, the title bar icon appears faded. (Mac OS 10.X users also can look at the red Close button in the title bar; if it contains a black dot, the image has been edited since it was last saved.)

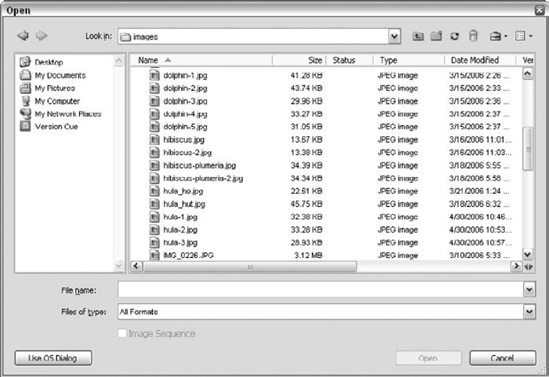

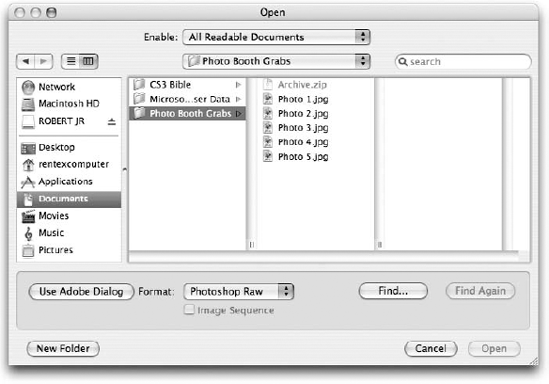

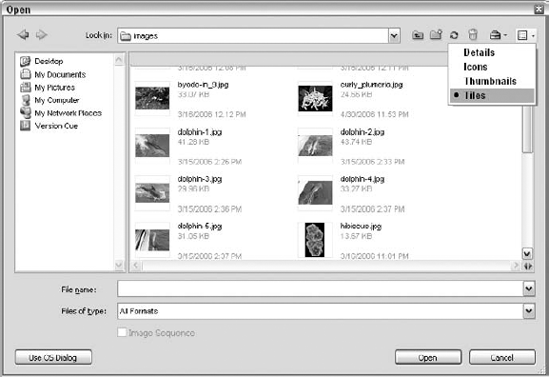

Of course, you can always open images the old-fashioned way by choosing File

The default Open dialog box behaves just like the ones in other Windows and Macintosh applications, with a folder bar at the top, a scrolling list of files, and the usual file management and navigation options. You also can open multiple files at one time. To select a range of files on the PC and in Mac OS 10.X, click the first file name and then Shift-click the last file in the range. Ctrl-click (

The Photoshop version of the Open dialog box (not to be confused with the Adobe Open dialog box, discussed just a few paragraphs from here) also includes a few controls that most other programs lack. You can read about these options in the next sections. But first, a few other brief notes about opening files:

When you choose File

When you open an image, Photoshop may display a dialog box telling you that the color profile of the image doesn't match the default color profile you've established. You have the option of converting the image to the default profile or leaving well enough alone. See Chapter 17 for help with this issue.

Tip

When opening an image, you may occasionally encounter a dialog box warning you that some data in the file cannot be read and will be ignored. Well, it's a bunch of bunk. If this happens to you, just click OK to dismiss the warning and open the image as usual.

The Adobe Open dialog box (displayed by clicking the Use Adobe Dialog button in the lower-left corner of the default Open dialog box) offers the same options as the default Open dialog box. You can click the Look in drop-down list to choose from disks, drives, and other places to look for your file. You also can click the icons on the left side of the dialog box to look on the Desktop and in particular folders. In the main area of the dialog box, shown in Figure 3.6, you can view the images in the open folder or drive in the same ways that you can in the default Open dialog box — in Details view, where file name, size, status, type, and date modified are displayed, Icons, Thumbnails, or Tiles view. Wait — Tiles? Yes, as shown in Figure 3.6, Tiles view shows an icon for the image — indicating format — and some basic stats for the image, including name, size, and date/time modified.

Tip

Click the Tools button (looks like a little briefcase) in the upper right of the dialog box to access a menu that includes commands for accessing the Bridge, creating a new project, editing file properties, creating new folders, and looking at or restoring deleted files. This menu also offers a command for going back to the "OS Dialog" (OS standing for Operating System), which you also can do by clicking the Use OS Dialog button that has replaced the Use Adobe Dialog button in the lower-left corner of the dialog box. There also is an Adobe dialog version of the Save and Save As dialog boxes — look for coverage of these later in this chapter.

Figure 3.6. The Tiles view in the Adobe version of the Open dialog box offers enlarged image icons and file information that rivals the familiar Details view's list of file statistics.

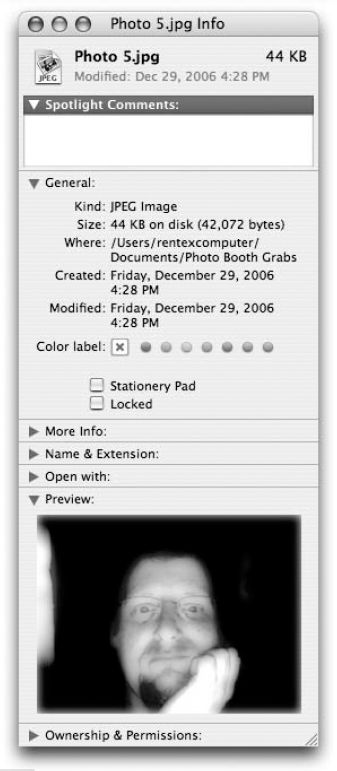

To help you assess an image before you open it, Photoshop displays a thumbnail preview of the selected file in the Open dialog box, as shown in Figure 3.7. On the Mac, the column view found in Open dialog boxes automatically displays a preview of graphic files. On the PC, Photoshop automatically displays thumbnails for any files saved in the native format (PSD). If you're running Windows XP, the operating system may generate thumbnails for files saved in other formats.

On the Mac, the thumbnail space may appear empty, which means the file does not contain a Photoshop-compatible preview. The file may have been created by a piece of hardware or software that doesn't support thumbnails, or the thumbnail feature may have simply been turned off when the image file was saved. To generate thumbnails when saving images in Photoshop, press Ctrl+K and then Ctrl+3 (

Figure 3.7. You can see a preview of an image if you previously saved it in Photoshop with the thumbnails option selected.

Note

What's that Image Sequence check box in the Open dialog box all about? This option pertains to video and image sequence files. Photoshop CS3 allows users to open and edit video, frame by frame, and to open sequential image files. Find out more about Photoshop CS3's video image support in Chapter 19.

Mac OS 10.X is pretty clever about generating previews of graphic files all on its own. Depending on the file format, you can generally get a preview of a graphic file, no matter what the thumbnail saving settings were. Select an image in the Finder and press

Figure 3.8. The Get Info command in Mac OS X can show previews of many different graphic file types.

Tip

The Open dialog box isn't the only place where you can preview an image before you open it. To preview an image file directly in Windows Explorer under Windows XP or 2000, simply navigate to the folder in which the image is located and click the file to highlight it. A section on the left side of the folder window, labeled Details under Windows XP, displays a high-quality image preview, provided a preview was saved along with the image. Alternatively, you can view thumbnail previews for an entire folder of images by choosing View

The scrolling list in the Open dialog box contains the names of the documents that Photoshop recognizes it can open. If you can't find a desired document on your PC, it may be because the Files of Type pop-up menu is set to the wrong file format. To view all supported formats, either select All Formats from the Files of Type pop-up or type *.* in the File Name option box and press Enter.

If a file lacks an extension, the Open dialog box won't be able to identify it. This unusual situation may arise in one of two ways. On rare occasions, a file transmitted electronically (through the Internet, for example) loses its extension en route. But more likely, the file comes from a Macintosh computer. The Mac doesn't need file extensions — the file type identification resides in the resource fork — so many Mac users never give a thought to three-character extensions.

You can solve this problem by renaming the file and adding the proper extension or by choosing File

If you can't find a document in the Open dialog box on your Mac, it may be because Photoshop doesn't recognize the document's four-character type code. The type code for a document created or last edited on a Macintosh computer corresponds to the file format under which the image was saved (as explained in the upcoming section on file formats).

For example, TIFF is the type code for a TIFF image, JPEG is the code for a JPEG image, GIF is the code for a GIF image, and so on. However, if you transferred a document from another platform, such as a Windows machine or a Unix workstation, it probably lacks a type code. In the absence of a type code, Photoshop looks for a three-character extension at the end of the file name, such as .tif or .jpg or .gif. But if the extension is as much as a character off — .tff or .jpe or .jif, for example — Photoshop won't know what to do.

To see all documents regardless of their type code or extension, select All Documents from the Show pop-up menu in the Open dialog box, as shown in Figure 3.9. When you click a document in the scrolling list, the Format option displays the format that Photoshop thinks the file was saved in — if it has any thoughts to offer. If you disagree, click the Format option and select the correct file format from the pop-up menu. As long as the image conforms to the selected format option, Photoshop opens the image when you press Return. If you get an error message instead, either select a different format or try to open the document in a different application.

If you know the name of a file — or at least part of the name — but you can't remember where you put it, click the Find button, type some text in the resulting option box, and press Return. Photoshop searches the disk in a fairly random fashion and takes you to the first file name that contains the exact characters you typed.

If the first file name isn't the one you're looking for, click the Find button again to find the next file name that contains your text. If you want to search for a different string of characters, click Find and type some different text.

The Bridge, introduced with Photoshop CS2 and enhanced for CS3, replaces the File Browser for accessing, organizing, and storing data about your images. To call the Bridge a feature seems like a gross understatement. The Bridge is really an application unto itself — it has its own workspace, menus, and tools, and it opens as a separate application in terms of how the operating system (Windows or Mac) sees it.

You can access the Bridge without opening Photoshop at all, or you can use any one of these methods for opening it from within Photoshop:

The Go to Bridge button: Click this button, shown in Figure 3.10, found to the left of the palette dock. The Bridge opens in its own window shortly thereafter.

Choose File

Browse: This opens the Bridge in its own window.

Choose File

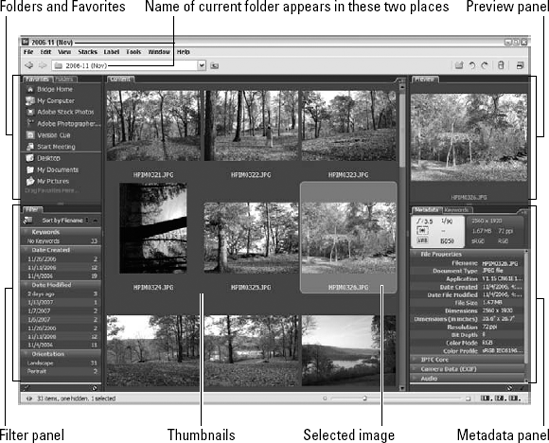

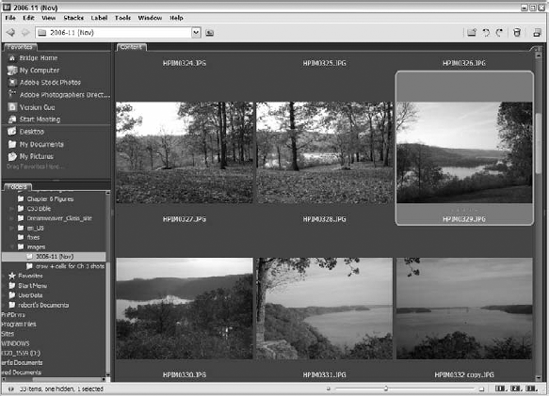

Close and Go to Bridge: This closes the active image and opens the Bridge in its own window. You would do this when you're finished with an image and ready to go find another one, using the Bridge tools for accessing images. The Bridge interface appears in Figure 3.11.

The sequence of events that takes you to and through the Bridge might go something like this: You remember that you need to find a particular photo, but you're not sure of the file name. Or, you want to check whether you have all the photos you should have stored in a particular folder or on a particular CD. The Open dialog box doesn't show you all your photos at once, and hopping out to the Finder (Mac) or Explorer (Windows) to look at thumbnails is too time-consuming. What to do? Fire up the Bridge.

Using any of the aforementioned methods — clicking the Go to Bridge button or using the File

Tip

You can resize the different parts of the Bridge workspace by clicking and dragging the walls of the various panels. Drag to the right to widen the panel of tabs on the left; drag up and down on the dividers between the Favorites/Folders, Content, and Metadata/Keyword panel areas. By resizing different areas of the workspace, you can rob space from information that you don't care about to make more room for the stuff you need to see more clearly or in its uncluttered entirety.

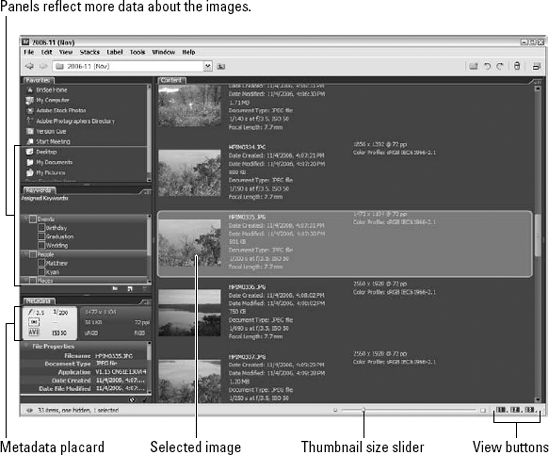

Assuming that you're now looking at an array of thumbnails of the subfolders and images within the folder, drive, or disk you've chosen from the tree, you can click an individual photo and view its data (see the Metadata panel in the upper right, shown in Figure 3.13) or change your view to Details — by choosing View

If you want to open a particular file, just double-click it. If Photoshop was not already open, it opens in its own window (the Bridge remains open, too), with the selected file open in its own image window. If Photoshop was already open, it becomes the active application and displays the selected file in its own image window — so the final outcome is the same, whether the Bridge tells Photoshop to open and show you your image, or if you had Photoshop open, ready, and waiting.

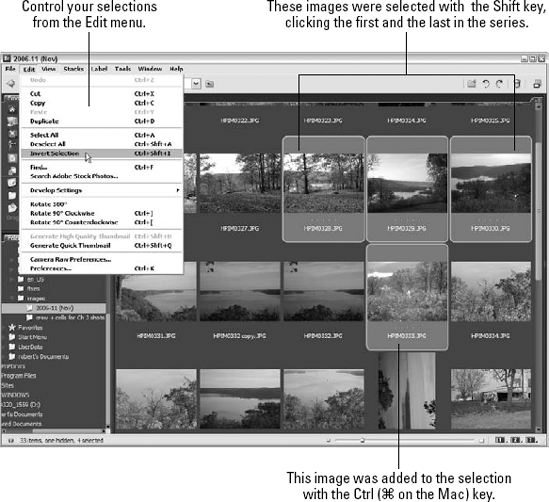

You also can select multiple images, too — just click them and press Shift to select a series of files, or Ctrl (Windows) or

Tip

If you want to open or move everything but the file or files you have selected, choose Edit

Note

The Bridge in CS3 now has a Stacks menu, which should not be confused with Stack Mode in Photoshop (see Chapter 14). You can stack a group of photos [select them with the Shift or Ctrl (

The whole point of the Bridge is to give you a powerful, yet simple way to view your images and access information about them. Of course, being able to open the files after viewing them is important, too, but you can do that through Photoshop itself. No, the big plus to the Bridge are the image viewing options, each accessible through the View menu (big surprise, eh?). You also can use the view buttons in the lower-right corner of the workspace.

In the View menu, you have these choices:

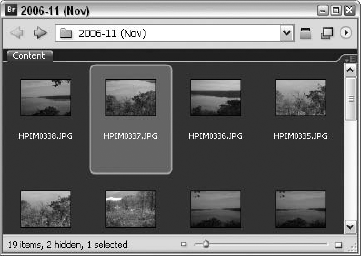

Compact Mode: Choose this, and the Bridge workspace is reduced to a small window, without a menu, as shown in Figure 3.14, and it moves to the lower right of your desktop. You can resize it with your mouse, but the idea is for it to be small and out of the way. Double-click the title bar (or click the Maximize/Restore button) to return it to its original size.

Slide show: Choose View

Tip

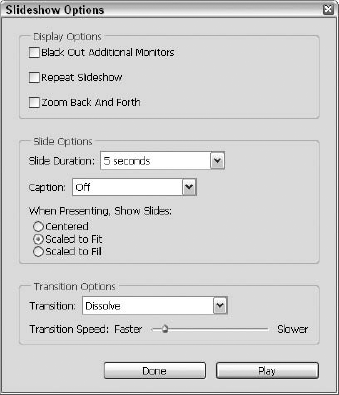

The next command after Slideshow is Slideshow Options. Choose this to change how your slideshow looks and works. As shown in Figure 3.16, you can customize the Display, the way the slides run (and how the whole show runs, including choosing how long individual slides stay onscreen), and how the slides transition from one to the next.

Figure 3.15. Want to have your images shown to you one at a time? Choose View

Slideshow. Your images take up the full screen, for maximum preview power.

That's it in the View menu, in terms of choices for how your images display in the Bridge. Now let's look at the numbered buttons in the lower-right corner of the Bridge workspace. By default, you see three buttons — 1, 2, and 3 — and if you click any one of them and hold the mouse (or click the tiny triangle in the lower-right corner of the button), the pop-up menu shown in Figure 3.17 appears. These eight viewing options offer something for everyone:

Default: That's the view we first showed you, with Content in the middle, Folders/Favorites in the upper left, Filter information in the lower left, and Metadata/Keywords on the right. You can see this view back in Figure 3.12.

Light Table: This view shows you just your images, in thumbnails that you can resize with the slider in the lower right, next to the numbered view buttons.

File Navigator: Choose this view if finding files is your big issue — maybe you don't know where the one you want is hiding, or you need to get a better sense of your overall file storage system — assuming you have one, that is! Figure 3.18 shows this view, with thumbnails taking up the entire right 2/3rds of the Bridge, and navigational tools — Favorites and Folders broken out into their own separate panels — on the left.

Metadata Focus: This view is the opposite of File Navigator, in that on the left, instead of Folders and Favorites, you see the Metadata and Keywords tabs broken out into two panels, and the rest of the window is your image thumbnails. This view assumes you know where your files are, but want to look at and edit the information stored about them.

Horizontal and Vertical Filmstrips: These two views give you just what you'd expect — a strip of images, running either horizontally or vertically, in sizes that you can control with the slider on the lower right, next to the numbered view buttons. As shown in Figure 3.19 (Horizontal Filmstrip view only, but you get the idea), a strip of images appears along the bottom, and a larger thumbnail appears singly, above the strip. To see a large version of any image in the scrollable strip, click the thumbnail in the strip, and the large image appears in the Preview area. The left panels are Favorites and Filter in this view.

VCStart Page: Again, you have a very simple view, this time with only Favorites and Folders tabs on the left and resizable thumbnails in the remaining majority of the window.

Figure 3.19. View your images one at a time, selecting them from a filmstrip that either runs along the bottom (as shown here) or down the right side of the window (Vertical Filmstrip, not shown).

Note

You can move and resize the panels on the left side of the Bridge workspace much like you can move and resize the palettes in Photoshop. Click the panel's tab itself and drag it up or down to regroup the tabs within the right-hand panel. You can group the palettes in any configuration you want — for example, you can drag them all so that they share a single box so less vertical space is taken up in the left-hand panel. To determine which tabs are displayed, use the View menu to select and deselect them by name. A check mark indicates that the panel is currently displayed.

You can select images — choosing from those displayed in the main viewing area — by clicking them with your mouse, as shown in Figure 3.20, or by making selection command choices from the Edit menu. You also can select images by searching for them (see coverage of the Find dialog box later in this section of this chapter). Once found, the images meeting your Find dialog box criteria can be selected en masse or by clicking the one that you really wanted to find.

To select images with your mouse, click once on the single image you want, or to gather more images, press Shift to select a series — as shown in Figure 3.20 — or press Ctrl (

Figure 3.20. Select a contiguous group of images with the Shift key, or use Ctrl (

Warning

If yours is not the latest and greatest computer with lots of memory, you may want to avoid opening several images at once. Start small: Open one or two images, and if things don't slow down too much, you can open additional images until you notice the application becoming a bit clumsy. You may be prompted that your virtual memory setting is too low, and if you're a Windows user, Windows beefs up the memory allocation to meet your needs at the time.

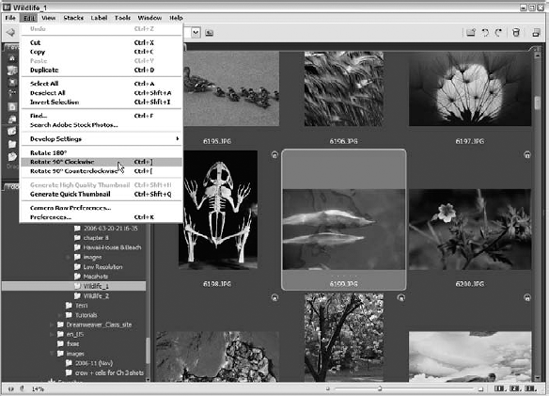

In Photoshop, you can rotate the image canvas, turning an image that was scanned lengthwise or upside down that you want to see turned around. The change made through the Image

As shown in Figure 3.21, you can select an image and then choose Edit

Figure 3.21. Rotate an image thumbnail for easier viewing, without actually rotating the image itself.

Tip

In the upper-right corner of the workspace is a series of buttons — New Folder, and then the two rotation buttons: Rotate 90 Clockwise and Rotate 90 Counterclockwise. You can use these on whichever image is selected at the time — or use them to rotate multiple selected images all at once. There's also a trash can button for deleting images, and the last one gives you quick access to Compact Mode.

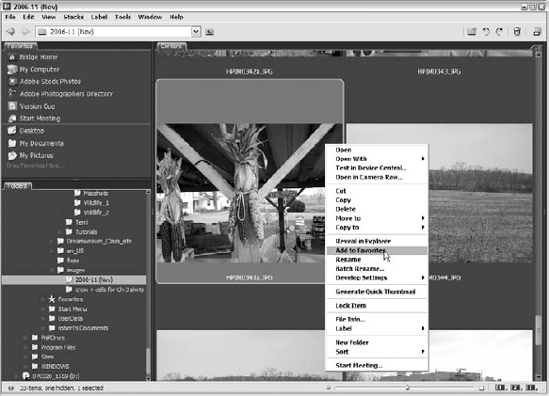

Like the sites you've added to your Favorites (or Bookmarks) in your Web browser, images that you want to be able to come back to quickly and easily (and frequently) also can be turned into Favorites, accessible through the Favorites panel on the left side of the Bridge workspace. Figure 3.22 shows the Favorites list, which includes locations on the computer, folders, and images.

Figure 3.22. Are there images you use often and navigating to them via the Open dialog box is a pain? Add them to the Bridge Favorites list, and they're always right where you need them.

Tip

If you're not a big Bridge user and want your oft-used images to be easily accessible, increase the number of files that can be included in the File

To add an image to Favorites, just right-click (Control-click on the Mac) and choose Add to Favorites from the pop-up menu. You also can choose File

Tip

When you click an image in the Favorites list, the Bridge assumes you want to open it in Photoshop, so don't click the image in the list unless you want that to happen.

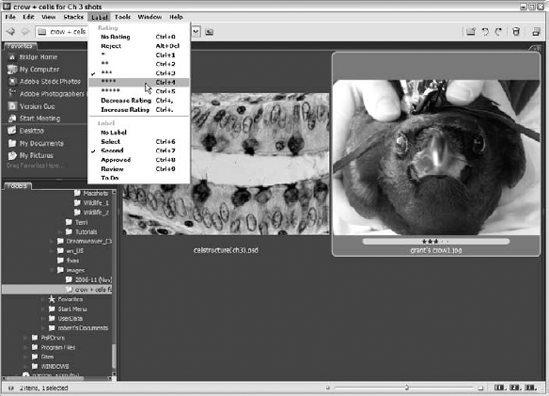

Humans' affinity for ranking and rating things is obvious — there are entire books of top-ten lists, and a popular late-night talk host compiles a funny top-ten list for each show. Applying value, even if it's totally subjective, is something most of us can't resist. The Bridge, being aware of this, gives you the ability to rate and label your images — ranking them with stars (from one star to five stars) and applying color-coded labels. As shown in Figure 3.23, the Label menu offers five ratings and five color labels, plus the ability to incrementally increase and decrease the existing rating for any image. You also can right-click (Control-click on the Mac) an image and use the Image command in the pop-up menu to access the Label color options.

Metadata, as described earlier in this chapter, is a cornucopia of file information, divided into three sections. You can scroll through them in the Metadata panel, shown in Figure 3.24. You can look at File Properties (the most commonly used and therefore visible without scrolling), IPTC Core data, and Camera Data (EXIF). As stated earlier, in CS3, there's also DICOM data, for medical imaging (storing patient's name, gender, etc.).

For many of your files, the vast majority of these bits of data will be blank; clicking the little pencil icon next to any currently blank or editable fields opens a text box into which you can type the appropriate information. Actually, for many users, this area may be entirely ignored, because either the file name or one glance at the image itself tells you all you need to know. On the other hand, if you need to keep track of things like when the picture was taken, how big a file it is, what its width and height are, and its pixel depth, the File Properties section is there for you, ready to house that sort of thing.

Figure 3.24. "Intellectual Genre"? Okay, maybe somebody needs that field, but information about the photographer and the date the picture was taken are the fields most of us will use.

The IPTC Core data houses even more information that you may or may not care about — usually stuff that pertains to other people's images — so if you typically work with other artists' images, you'll find plenty of places to keep their facts straight. Camera Data is just that — data about the camera used to take the image, which is right there and filled in if you took the picture with a digital camera. If you (or someone else) took the picture the old-fashioned way, the camera data will have to be entered manually.

Whether or not you use some or all of the data in these categories in the Metadata panel, you may have need of what little is there. The Bridge makes it easy to use the data, as desired, and one of the ways you can do so is through the Metadata panel's options menu button (triangle button on the top right of the panel's tab), where you're presented with the following commands/options:

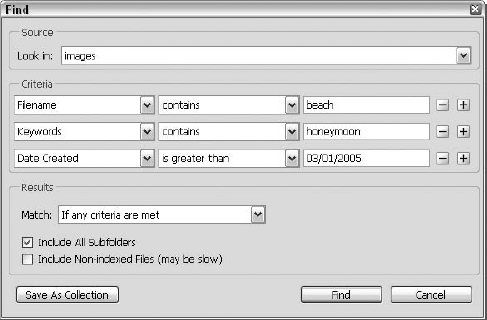

Find: This command opens the Find dialog box (now there's a surprise), through which you can search for files based on various criteria and locations, and you can customize the results you want to see included. You set up your search from the top of the dialog box, shown in Figure 3.25, starting with Look In, where you can choose from all the folders and drives to which you have access on and through your computer. You also can click Browse at the foot of that folder to open a navigation window that makes it easier to search for the drive/folders in which you want to search.

Next, enter your search Criteria through the three fields in that section. You can select the field to look in (a list of the fields in the Metadata section of the Bridge window appears), choose the standard (contains, does not contain, exists, does not exist), and then type the text that should be compared to your criteria. Click the plus sign to add multiple criteria levels [such as Date Created is greater than (after) 03/01/2005 AND Filename contains "Beach"]. You can have up to 13 criteria levels (use the minus sign to remove extra criteria levels from your search), and for each type of criteria, the appropriate choices for matching records and entering in your values change, helping you fill things in a way that'll make sense to the software.

Figure 3.25. Use the Find dialog box to locate a file based on any of the stored information about the file.

After you have your search set up, use the Results section to fine-tune your results. Include Subfolders is a good one to turn on, and of course the Match setting allows you to decide how stringently your criteria settings are followed (if any criteria are met versus if all criteria are met). Click Find to send the Bridge sniffing for your files, or click Cancel to scrap the whole enterprise.

Increase Font Size and Decrease Font Size: These commands change the display font size for the data in the Metadata panel.

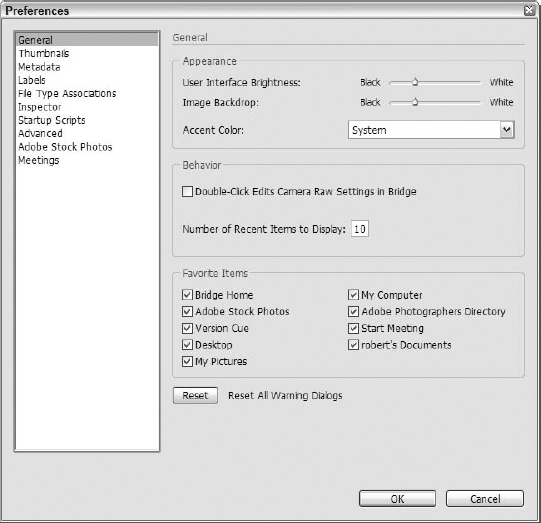

Preferences: This opens the Preferences dialog box, shown in Figure 3.26, through which you can customize the Bridge. You can customize the settings for nine different areas of the Bridge, including General (basic Bridge settings) to Thumbnails (how they look) to Labels (what the colors mean) to File Type Associations (which applications fire up automatically for which file types).

Show Metadata Placard: You know that little graphic on the upper left of the Metadata panel, with a gray background (it's shown in any view of the Metadata panel)? Well here's your chance to say sayonara to that little item if you find it bothersome. Maybe it takes up too much room, or maybe you don't care about the data it displays (camera settings). Whatever your reason, you can turn the placard on and off through this command.

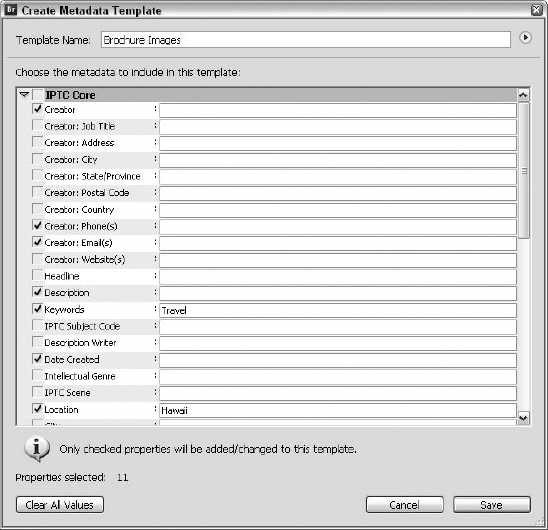

Create Metadata template: Choose this if you want to pick and choose the fields that show in the Metadata panel and save your own set of fields as a template. For any fields where you want something to always appear, enter those values into the boxes on the right of the individual fields. After you've done this, the following two commands become available, and their submenus list your saved templates. Figure 3.27 shows the IPTC Core data list of fields.

Append Metadata: Using preset templates, you can establish new data that will be stored about individual files.

Replace Metadata: Instead of adding to the metadata, this command allows you to choose from data templates that replace the metadata that appears by default.

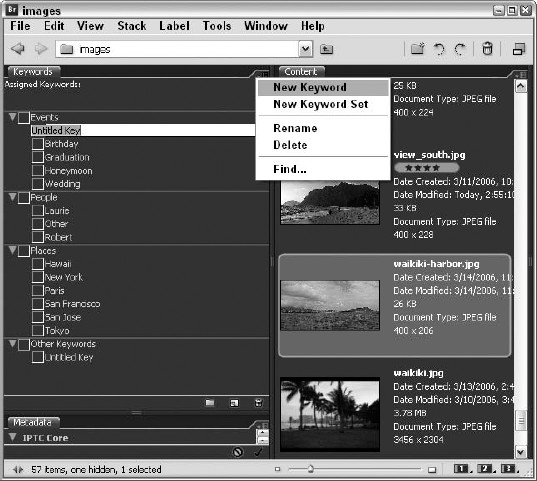

Next to the Metadata panel tab is the Keywords panel tab, shown in Figure 3.28. Keywords are searchable text that is associated with individual images and stored with the file's data to help you locate files easily. Keywords are one of the Criteria you can set in the Find dialog box used to search for files. For example, if you're looking for all your wedding photos, you can tell Photoshop to find all files with "Wedding" in the Keyword list.

To view the Keywords for any file, click the file in the main display area and then click the Keywords tab on the left. A list of words — names, places, and categories such as "Birthday" and "Graduation" — appears with check boxes next to them. Boxes with check marks indicate an association with that keyword.

To add your own keywords to the list, click within the Keyword Set you want to add a keyword to and click the Keywords panel options menu button (that triangle again). Choose New Keyword, and an "Untitled Key" entry appears in the list (see the menu and the resulting Untitled Key in Figure 3.28) and becomes highlighted; you can type a new keyword to replace the sample text. In this case, a new keyword is being added to the Events Keyword Set.

To set up a new category, click the Options button and choose New Keyword Set. As shown in Figure 3.29, an Untitled Set appears, and you can again replace the sample text with a set name of your choice. After making a new set, you need to use the New Keywords command to create keywords for the set. For example, if you create a set called "Family," you can create keywords for individual people ("Mom" or "Uncle Emil") and/or you can create keywords for family events, like "Christmas" or "Bar Mitzvahs."

After you've created your own keywords and sets, additional commands become available in the Keywords panel options menu. The Rename and Delete commands appear, and you can use them to do just what you'd expect — rename a selected keyword or set, or delete a keyword or set you no longer need.

Note

The Find command appears in the Keywords options menu, just as it does in the Metadata menu. The resulting dialog box is the same as the one described earlier in our discussion of the Metadata options menu commands.

To apply a keyword to an individual image, select the image and then place check marks in the boxes next to one or more of the words in the Keywords panel. You can check as many boxes as you want, and if you think of any other words that you might want to use in searching for the selected image in the future, use the New Keyword command to create them.

The Creative Suite (referenced by the "CS" in Photoshop CS3) is a group of Adobe applications that are typically used — if not at the same time — together in terms of sharing files. The movie clips edited in Adobe Premiere may end up edited as still shots in Photoshop, for example, or the still photos you edit in Photoshop might end up in a Dreamweaver Web site or used for page layout with InDesign. You get the idea.

Figure 3.29. Choose to create a new Keyword Set to give yourself even more ways to categorize and organize your images — for your use and to simplify things for other people who use your images, too.

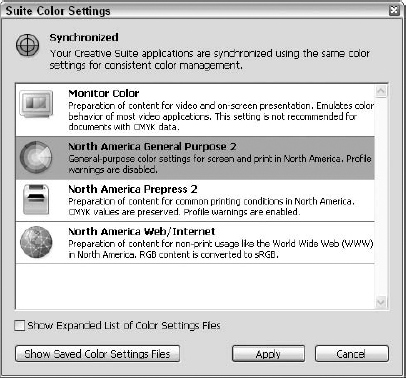

What assists the suite in operating as a cohesive unit is the synchronization of color settings. Through the Bridge, you can make sure that Photoshop holds up its end of the bargain, working with the dialog box shown in Figure 3.30. To display and work with this dialog box, choose Edit

To synchronize the settings, you can select one from within the dialog box. This sets up the suite applications — as many as you have installed on your computer from the same version of the suite — to work together with the same color settings.

Tip

To access the settings files, click the Show Saved Color Settings Files button, which opens an Explorer window with a folder tree on the left and the settings files on the right. If the right side of the window is empty, you have no saved color settings files.

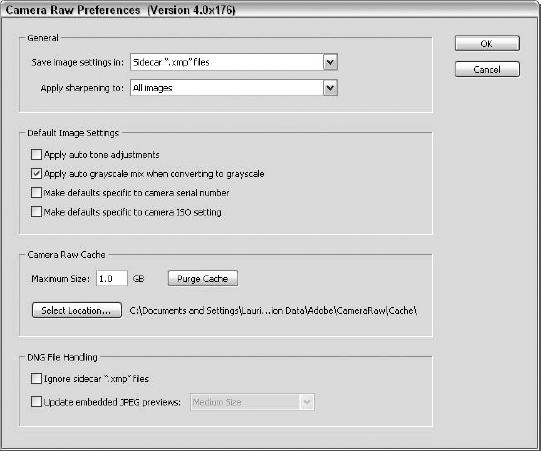

Camera Raw, a file format supported by Photoshop, is discussed later in this chapter and elsewhere in this book (see Chapter 18). You can set your Camera Raw preferences through the Bridge, using the Edit menu (or the Bridge CS3 menu if you're on a Mac). After the Camera Raw Preferences dialog box, shown in Figure 3.31, is open, you can choose how image settings are saved (pick a format; Sidecar ".xmp" files is the default), choose how sharpening is applied, set the Default Image Settings, and set up the Camera Raw cache, which includes deciding where the cache file is saved (find out more about cache later in this chapter) and how much space to allocate to cache files. You also can choose how CS3 deals with DNG files. After you like your settings, click OK.

The old saying "A place for everything, and everything in its place" is a philosophy that many tidy people live by. It's also a good motto for Photoshop users, because productivity hinges on easy access to the tools you need. Keyboard shortcuts can help put things at your fingertips (literally), but they don't always help enough when it comes to using palettes, tools, and so forth. Photoshop is sensitive to this and gives you the Window

When you choose this command, the Save Workspace dialog box appears, giving you the chance to apply a relevant name to the workspace and to choose a keyboard shortcut (Ctrl + any of the function keys from F6 through F12, except F10, for Windows users, cmd + the F1 through F6 keys if you're on the Mac) that invokes the saved workspace configuration. You also have an option to Save Window Location as Part of Workspace — meaning if you have the Bridge window sized and positioned the way you want it, you can save that position, too.

Note

"What about preset workspaces?" you may ask. Good question. If you choose Window

You may spend several minutes generating previews, rotating thumbnails, and ranking images inside the Bridge. Because not a single one of these functions or their impact on the image display in the Bridge is saved with the image file, you might wonder how Photoshop prevents you from losing your work. It does this by saving a cache file that records all changes made to an entire folder full of images.

This all happens in the background without any assistance from you, but problems can crop up, and if Photoshop didn't have some sort of plan in the works, you'd lose your work if anything went wrong while you were trying to juggle multiple open images, view new images on a CD, share files over a network, or any other combination of common, often concurrent activities.

It can't be that you have to lose all your work at the slightest change in display or other settings, nor can it be that you have to spend all your time worrying about this caching process. There is, in fact, a backup plan, in the form of two commands that can help ease the burden and prevent the loss of your work — just choose Tools

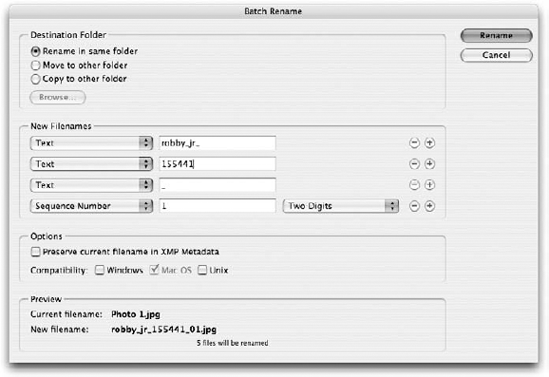

To rename a handful of specific files, click and Shift-click their thumbnails to select them. To rename all files in a folder, choose Select All or Deselect All from the Edit menu. Then right-click (Control-click on the Mac) and choose Batch Rename (or choose Tools

You have the option of renaming files in the folder where they currently reside (the most common choice) or moving them to a different folder. If you click Move to New Folder, the File Browser asks you to select a destination. Note that moving means just that — Photoshop relocates the files as opposed to copying them to the new location.

You can specify up to six File Naming variables, though two or three are usually sufficient. The three Document Name options retain or change the case of the name currently assigned to the file. Alternatively, you can type your own name in an option box.

Figure 3.32. Use the Batch Rename command to rename multiple files in a single operation. You can select naming options from a pop-up menu or type your own name.

Warning

To ensure that your images are named so that they'll work on any computer, select all three Compatibility options. (Either Windows or Mac OS is already selected, depending on your platform.) Then click OK to apply your changes. Note that, as with other File Browser operations, renaming is not undoable. So be sure that all settings are correct before you click OK. If you have any doubt about how the command works, experiment on a few trial images before renaming important files.

As we've seen, an image file can contain much more information than the image data. On top of pixels, alpha channels, color profiles, and all the other image data you can cram into your image files, you can add a variety of reference information — where you shot the picture, who owns the image copyright, your thoughts on the photo, potential uses for the prints, and so on.

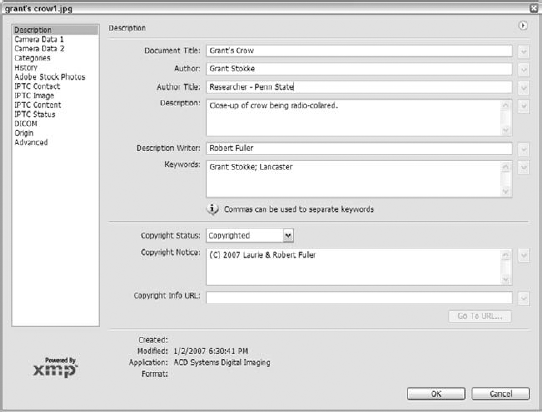

Despite the abundance of data already available to you through the Bridge Metadata panel, sometimes you need to be able to edit and access more information than a little panel can hold. That's when you should choose File

To switch from one File Info area to another, press Ctrl+1 through Ctrl+8 (

Description: The options in this panel are fairly straightforward. For example, if you want to create a caption, type it in the Description option box, which can hold up to 2,000 characters. If you select Description in the Output section of the Print dialog box, the caption appears below the image when you print it from Photoshop. You also can add a copyright notice to your image. If you choose Copyrighted Work from the Copyright Status pop-up menu, a copyright symbol (©) appears in the image window title bar and in the information box at the bottom of the screen on the PC or at the bottom of the image window on the Mac. This symbol tells people viewing the image that they can go to the Description panel to get more information about the owner of the image copyright. Choose Public Domain if you want to make it clear that the work isn't copyrighted (an Unmarked image might actually be a neglected copyrighted one).

You also can include the URL for your Web site, if you have one. Then, when people have your image open in Photoshop, they can come to this panel and click Go to URL to launch their Web browser and jump to the URL.

Tip

Click the down arrow to the right of an option to reveal a pop-up menu containing information that you've previously entered for the option in other images. For example, if you've listed yourself as the author of another image you recently worked on, you can click the arrow next to the Author option and select your name.

Note

Because only people who open your image in Photoshop have access to the information in the File Info dialog box, you may want to embed a digital watermark in your image as well. Many watermarking programs exist, ranging from simple tools that merely imprint copyright data to those that build in protection features designed to prevent illegal downloading and reproduction of images. Photoshop provides a watermarking utility from Digimarc as a plug-in on the Filters menu; before using the plug-in, visit the Digimarc Web site (

www.digimarc.com) to find out which, if any, of the Digimarc watermarking schemes best suits the type of work you do.Camera Data: Following the Description options you'll find two panels of Camera Data values. This is where the EXIF information discussed earlier in the chapter is displayed. EXIF data is written by the digital camera, not the user, so these fields cannot be altered.

Categories: The Categories panel may seem foreign to anyone who hasn't worked with a news service. Many large news services use a system of three-character categories to file and organize stories and photographs. If you're familiar with this system, you can type the three-character code in the Category option box and even throw in a few supplemental categories up to 32 characters long.

History: If you've selected the History Log option in the General panel of the Preferences dialog box, this panel displays the history data for the image. Otherwise, it's blank. (For complete details on setting up the History Log, see Chapter 2.)

Origin: This panel provides more option boxes for entering specific information about how the image came to be, including the date, the location, and a headline. Click the Today button to automatically enter the current date and time in the Date Created field. You can use the Urgency pop-up menu to indicate the editorial timeliness of the photo.

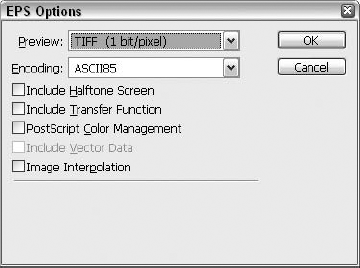

Advanced: The Advanced panel displays all the information you've set for the image in metadata's XMP format. On a PC, file information is saved only in image file formats that support saving extra data with the file. This includes the native Photoshop (.psd) format, EPS, PDF, JPEG, and TIFF. On a Mac, file information is saved with an image regardless of the format you use. Photoshop merely tacks the text onto the image's resource fork. If you need the metadata of an image to travel with the image file, regardless of platform, application, or operating system, saving an XMP file is the way to go. XMP, which stands for eXtensible Metadata Platform, is essentially a text file containing metadata that can be assigned to an image and read by many applications. The Advanced panel lets you save this type of file with the metadata you're currently viewing. From this panel, you also can open an XMP file and use it in place of your current metadata, as well as add the information from an XMP file on top of your image's metadata. Selecting any of the categories of metadata in the Advanced panel and clicking Delete clears that specific data from your image file.

Perhaps the most useful metadata-related feature in Photoshop is the capability to create metadata templates. If you have a collection of images with the same author or origin information, you don't want to have to go through the task of opening the File Info dialog box and manually entering metadata (or importing an XMP file) for each and every one. Photoshop can take care of this for you. Creating a metadata template is simple: Just open the File Info dialog box for any one of the images, and enter the common characteristics of the group. Next, click the right-pointing arrowhead in the upper-right corner of the dialog box, and choose Save Metadata Template. You'll be asked to type a name but not a location (Photoshop does that for you). Click Save, and you're finished. Photoshop automatically adds the metadata template to the pop-up menu in the File Info dialog box, so you can easily access it.

You can assign your saved metadata templates to multiple files at once in the File Browser. Simply select the files to which you want to assign the metadata and choose Edit

Have you ever wanted to try an effect without permanently damaging an image? Photoshop offers multiple undos, and you'll get a kick out of using the History palette to see before and after views of your image (as explained in Chapter 7). But what if you want to apply a series of effects to an image independently and compare them side by side? And save the variations as separate files? Or perhaps even merge them? This is a job for image duplication.

To create a new window with an independent version of the foreground image, choose Edit

The first rule of image editing — and of working on computers in general — is to save the file frequently. If your computer or Photoshop crashes while you're working on an image, all edits made during the current editing session are lost.

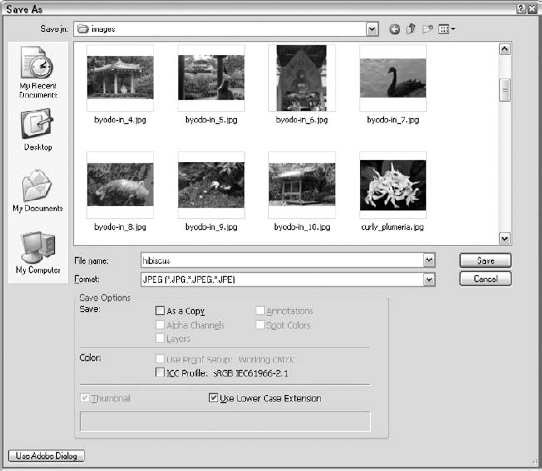

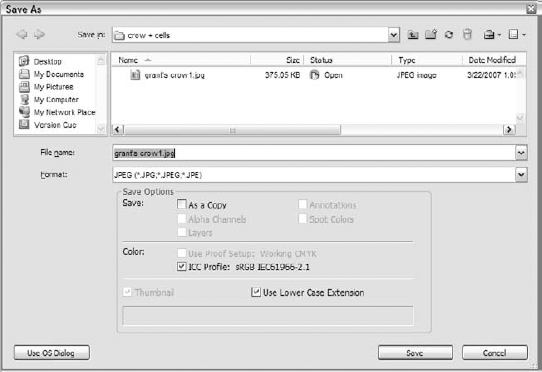

To save an image for the first time, choose File

After you save the image once, choosing the Save command updates the file without bringing up the Save dialog box. To save the image with a different name, location, or format, choose File

You also can execute the Save As command by pressing Ctrl+Shift+S (

Tip

To speed the save process, you may want to save an image in Photoshop's native format until you've finished working on it. Then, when the file is all ready to go, you can choose File

If you have multiple files open, you can close them in one step by choosing File

On the Mac, the Preferences dialog box includes an option that lets you append a three-character file extension to your files. Again, this option is located in the File Handling panel, so press

Why add PC file extensions on a Mac? Obviously, it makes life easier when sharing images with Windows users, and for Mac users, if you're working with an application that uses file extensions to indicate the source application (such as iPhoto, for example), you'll find it to be very helpful. More importantly, it's another form of insurance. If you're a Mac person and you ever find yourself using a PC, you're going to have tons and tons of old Macintosh image files that you'd like to open and reuse. With file extensions, you'll have no problem. Without them, good luck. The file extension is the only way a Windows application has to identify the file format. If there's no file extension, you have to tell the application which format to use. Although I don't question the basic record-keeping capabilities of your brain, you probably have better things to remember than what file format you used five years ago.

Tip

As mentioned in Chapter 2, you can automatically append an extension from the Save dialog box regardless of your preference settings. Press Option, choose an option from the Format pop-up menu, and there it is.

Certain save options that once upon a time were available only through the Save a Copy command now appear in the Save dialog box all the time. You also get access to these options when you choose Save As or press its keyboard shortcut, Ctrl+Shift+S (

Figure 3.34. Here's a look at the default Save As dialog box, which incorporates the Save a Copy command (previously a separate File menu command) as a save option.

There's a Use Adobe Dialog button in the Save As dialog box, which opens the Adobe Save dialog box — just like there's an Open dialog box in Adobe format, as described earlier in this chapter. After you click the Use Adobe Dialog button, the dialog box changes and you see the version shown in Figure 3.35. Note that the dialog box has a Use OS Dialog button that you can click to go back to the default Save As dialog box.

Figure 3.35. Should you use the Adobe Save As dialog box? Sure, why not? Its layout is a little different, and you may prefer it to the OS Dialog box, especially if you have to work in both Mac and Windows versions of Photoshop.

Note that the options you can select vary depending on the image file and the selected file format. If an option is dimmed, it either doesn't apply to your image or isn't supported by the file format you chose. And if your image includes features that won't be saved if you go forward with the current dialog box settings, Photoshop gives you the heads up by displaying a warning message at the bottom of the dialog box.

As a Copy: Select this option to save a copy of the image while leaving the original open and unchanged — in other words, to do what the Save a Copy command did in Photoshop 5.5 and earlier. The result is the same as duplicating an image, saving it, and closing the duplicate all in one step.

The whole point of this option is to enable you to save a flattened version of a layered image or to dump other extraneous data, such as masks. Just select the file format you want to use, and let Photoshop do the rest for you.

Annotations: Select this option to include any annotations that you created using the notes and audio annotation tools. You can find out how to annotate your images in the section "Adding Annotations" later in this chapter.

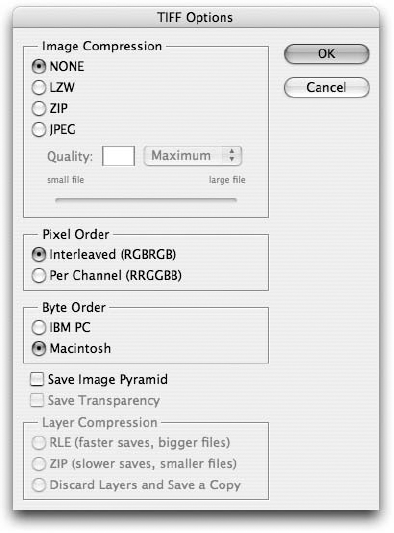

Alpha Channels: If your image contains an alpha channel — Photoshop's techy name for an extra channel, such as a mask (discussed in Chapter 9) — select the Alpha option to retain the channel. Only a few formats — notably Photoshop, PDF, PICT, PICT Resource, TIFF, and DCS 2.0 — support extra channels.

Spot Colors: Did you create an image that incorporates spot colors? If so, select this option to retain the spot-color channels in the saved image file. You must save the file in the native Photoshop, PDF, TIFF, or DCS 2.0 format to use this option.

Layers: TIFF and PDF can retain independent image layers, as can the native Photoshop format. Select the option to retain layers; deselect it to flatten the image.

Warning

If you're working with a layered image and select a file format that doesn't support layers, a cautionary message appears at the bottom of the dialog box. However, Photoshop doesn't prevent you from going through with the save, so be careful. All layers are automatically merged when you save the file in a nonlayer format. However, when you close the file, Photoshop reminds you that you haven't saved a version of the image that retains all data and gives you the opportunity to do so.

Use Proof Setup: This option relates to Photoshop's color profile options. If the current view's proof setup is a "convert to" proof, Photoshop converts the image to the selected proofing space when saving.

ICC Profile (Win)/Embed Color Profile (Mac): If you're saving your image in a file format that supports embedded ICC profiles, selecting this option embeds the profile. The current profile appears next to the option name. See Chapter 17 for advice about working with color profiles.

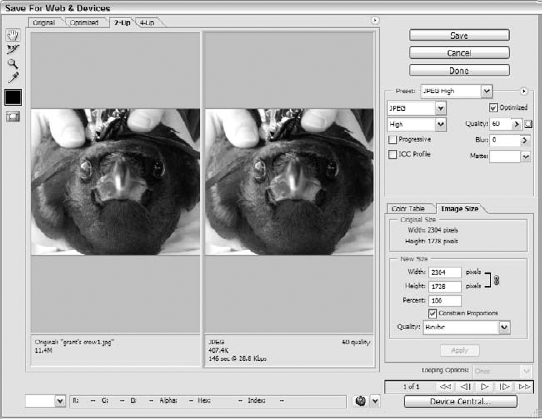

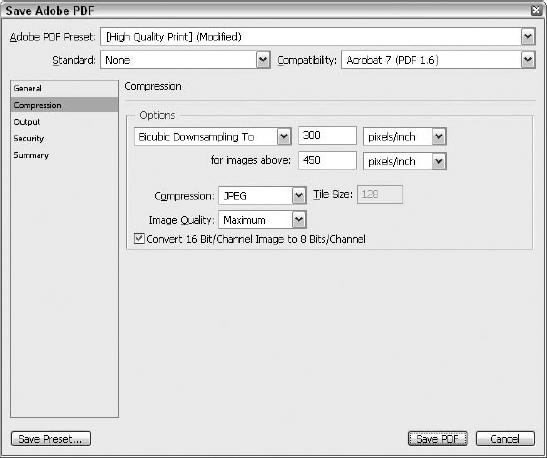

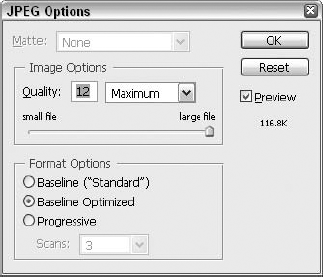

If your image is bound for the Web, you want to use the File

View side-by-side versions of the image: On the left, as shown in Figure 3.36, is the original; on the right (in the 2-up view), the optimized version. This enables you to see whether the optimization process has degraded the file at all.

Preview File Sizes and Load Times: Under the optimized view, the current file format, the file size, and how long that file would take to load for a site visitor using a 28.8 Kbps modem are displayed. The quality setting chosen on the upper-right side of the dialog box also appears in this area. Note that if you're using Windows, Preset options appear in a drop-down list, and on the Mac, they appear in a pop-up menu.

Choose the right format for the file: GIF, JPG, or PNG? Although these options are discussed later in this chapter, you can make your pick through the Preset options in the Save for Web dialog box. From GIF 128 Dithered to PNG-8 128 Dithered (with 10 options in between), you can choose from any Web-safe format, in any configuration.

Set the file quality or color density: If you've opted to save the file as a JPEG (which you should if it's a photo), there's a Quality slider. If you chose GIF (for line art or drawings with solid colors), you have a Colors option that allows you to set the image to display from 2 to 256 colors.

Customize the image: Using options that vary depending on which Preset you chose, you can totally customize the quality and display behavior of the file. Choose the Transparency, Dither, Lossy, and Matte settings (for GIF images), or choose to make your JPEG appear in Progressive fashion, with or without Blur.

Animate your GIF images: If the image is already saved as a GIF file, you can use the buttons along the bottom-right side of the dialog box (in the Color Table tab) to animate the image, layer by layer. You can create animated GIF images from simple on-off affairs to more elaborate movie-like graphics. Read more about this in Chapter 20.

After making your choices in the Save for Web dialog box, all you have to do is click Save, which opens a Save dialog box through which you can name and choose a location for your file. By default, if the file is already saved in PSD or another format (prior to your opening the Save for Web dialog box), Photoshop attempts to give the file that same name — with the extension for the format you chose for the Web-bound file. If the file name you gave it previously is not Web-friendly — bearing capital letters and punctuation other than dashes — edit the name accordingly.

And speaking of file formats, in the next section you learn more about different formats supported by Photoshop, their uses, benefits, and possible drawbacks.

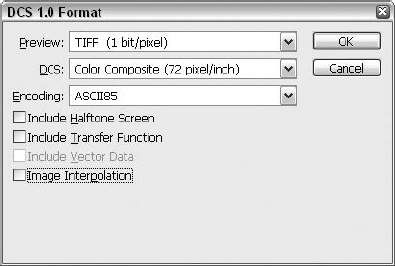

Photoshop CS3 supports more than 25 file formats from inside both the OS and Adobe versions of the Open and Save dialog boxes. It can support even more through the addition of plug-in modules that attach commands to the File

File formats represent different ways to save a file to disk. Some formats provide unique image-compression schemes that save an image in a manner that consumes less space on a hard drive. Other formats enable Photoshop to trade images with different applications running under Windows, the Mac, or some other platform.

Like most programs, Photoshop offers its own native format — that is, a format optimized for Photoshop's particular capabilities and functions. This PSD format saves every attribute that you can apply in Photoshop — including layers, extra channels, file info, and so on — and is compatible with versions 3 and later of the program. Of course, when you open files in earlier versions of Photoshop, you lose file attributes related to later versions, such as annotations, color proof options, and so on.

Note

Photoshop isn't the only application that uses PSD as its native format; PSD also is the native format for the "lite" version of Photoshop, called Photoshop Elements.

Tip

Perhaps not surprisingly, Photoshop can open and save more quickly in its native format than in any other format. The native format also offers image compression. Like TIFF's LZW compression, the Photoshop compression scheme does not result in any loss of data. But Photoshop can compress and decompress its native format much more quickly than it can TIFF, and the compression scheme is better able to minimize the size of mask channels (as explained in Chapter 9).