B

Badges and Identification Cards

A metallic badge is universally recognized as a symbol of lawful authority. In the classic film “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” the Mexican outlaw identified himself and his gang to the prospector (Humphrey Bogart) as a “federales.” The prospector then asked, “If you’re the police, where are your badges?” The bad guy responded, “Badges!? We ain’t got no badges. We don’t need no badges! I don’t have to show you any stinking badges!” That line, often quoted, has proven over time to be a classic touch of humor, but failure to display credentials doesn’t bode well in the retail industry.

Perhaps one of the most common reasons given by a detainee for his or her refusal to comply with the request or instructions to return to the store is, “I didn’t know who this person (loss prevention, or LP, agent) was; he didn’t identify himself”. “I thought maybe I was going to be mugged.” In reality, customers who are challenged outside the store are entitled to know the individual confronting them is a bona fide representative of the company and is authorized by state law to stop and question persons involved in what appears to be suspicious conduct. The display of credentials such as a badge and identification card speaks volumes about that authority. A badge is universally instantly recognized as a symbol of authority. Its display immediately upon a detention should remove any doubts as to the holder’s authority and remove any fears the detainees may have that their safety is at risk.

Typical examples of LP badges are shown in Figures B-1 and B-2.

Hence, we encourage every retailer to provide such credentials for their LP/security employees. These company badges should bear a number and be controlled and signed for in a department badge control ledger. When an employee leaves the company, termination procedures must require the turning in of the badge. Promotions within the department should allow for the exchange of badges to the next rank. If a badge is reported lost or stolen, the ledger is so noted, and the employee should be required to pay the costs for replacement. The badges, while shaped like those of law enforcement, should clearly indicate that the holder is not a law enforcement officer but represents private security/loss prevention.

Coincidentally, while we were consulting with a large and prestigious department store chain in Mexico, the LP employees complained they were denied the use of badges, and that posed a problem for them when making detentions. Further investigation revealed there was a cultural objection to private sector personnel possessing “police-type” badges, and the company was guided by that sentiment. But the agents needed identification; their complaint was valid. What to do? We designed a gold metallic card, the size of a regular ID card, inscribed with the word “SEGURIDAD” and the name of the company and encased the card behind a plastic window in a two-window folded leather case. When the case was opened and presented to a shoplifter, the suspect saw the gold card and a colored identification card with photo and description of the agent. The issue was therefore resolved to everyone’s satisfaction.

There’s no one right or wrong way for agents to carry and exhibit their badge. We’ve noted some agents carry the badge on their waist belt, whereas others wear the badge like a necklace and pull it out from their shirt, blouse, or jacket when needed. Others, more commonly, carry the badge along with their ID card in a leather case designed for that purpose and produce the opened case when needed. A note of warning: Badges worn like a necklace must have a “break-away” chain or cord in the event that necklace is seized by a combative subject.

Over the years some retailers have established rules that prohibit LP employees from taking the badge home, but the majority have no such restriction. However, written policy should spell out the restrictions on the badge’s use; e.g., it must never be displayed, except while “on the clock” and in the line of duty when confronting a detainee.

Loss prevention identification cards are separate from any company ID cards, and are designed specifically for the LP department. The name of the department—Loss Prevention, Loss Control, Security, Security and Safety, or Assets Protection—should be in color and the dominant feature of the card. The secondary feature should be a colored “driver’s license” type photo. The balance of information on the card would be boilerplate, name, age, description, etc., and issuer’s signature (vice president of LP).

Balancing a Cash Register

It is important that cash registers be balanced daily. Following is one example of how that is achieved. The store owner or manager should begin with the amount of cash in the till at the start of the day and end with the amount of cash at the end of the day (accounting for any funds removed during the day, “drops”). The amount of sales, “returns” (or cash paid out to vendors etc.), is then calculated, and when all data is factored in, the register condition (over, short, or balanced) is arrived at.

| End Reading (Detail tape) | 13249.00 |

| Start Reading | 12345.00 |

| [Register records both sales and credits] | |

| - - - - - - - - - - - | |

| TOTAL Sales: | $ 904.00 |

| Cash Sales $ 829.00 | |

| Credit Sales $ 75.00 | |

| SALES CASH TO ACCOUNT FOR | $ 829.00 |

| PLUS SETUP | $ 100.00 |

| TOTAL GROSS CASH TO ACCOUNT FOR | $ 929.00 |

| TOTAL PAYOUTS | 120.00 |

| Bottle Refunds $ 20 | |

| (Documented by paper records*) | |

| Refunds* $ 50 | |

| Pay Vendor* $ 50 | |

| (Documented by bottles) | |

| Bottle Refunds $ 20 | |

| TOTAL DEDUCTIONS FROM CASH SALES | $ 120.00 |

| TOTAL CASH TO ACCOUNT FOR | $ 809.00 |

| Less Drops | 500.00 |

| NET CASH TO ACCOUNT FOR | $ 309.00 |

| Cash turned in end of shift | $ 209.00 |

| Cash left for Set-up | $ 100.00 |

| Total | $ 309.00 |

| NET CASH ACCOUNTED FOR | $ 309.00 |

| REGISTER IN BALANCE |

Bank Deposits

Making the Deposit

My first experience in making bank deposits was working part time for the security department of an amusement park. Every day, except Sundays, we would drive the cash receipts, at times totaling several million dollars, to the bank and return with the change order.

The responsibility for making the deposits rested with the security department and was a major event. We were escorted to the bank by no fewer than eight municipal police officers in four marked cars, and all officers were armed with either shotguns or Smith and Wesson 9mm submachine guns. Why the amusement park never used an armored service was beyond me.

Making bank deposits in the retail environment can be a stressful event. Many companies choose to have their management teams make them. This decision is usually made as a cost-saving factor, as armored car services are expensive. The newspapers are full of crime stories where employees have been robbed, injured, or killed while making bank deposits. Employees even stage fake robberies at deposit boxes to cover up an employee theft. One such incident occurred when a management employee making a bank deposit on a Sunday morning reported being stabbed, with a knife, in the back by a robber who took the bank bag containing $15,000. Several things were wrong with this robbery, as he had his mother drive him to the bank, parking on the opposite corner from the drop box. It just didn’t sound right. There was even a “witness” standing across the street who observed the entire robbery. As it turned out, he staged the robbery, having his “witness” friend, a well-known local criminal, stab him in the back. It did not take long for the manager’s girlfriend, who worked in another store, to start bragging about the robbery and how much money her boyfriend received.

Safety in Numbers

If a company chooses to make its own bank deposits, there should always be two members of management making the deposit. Deposits should be made during the daytime, as it is safer to do so. If deposits must be made during the nighttime hours, after closing, the following safety suggestions must be considered:

• Always make deposits after the store is closed. You do not want customers in the store.

• Remove your name badge or cover your company uniform. You do not need to advertise your company while going to the bank.

• Always drive your deposit to the bank, even if your bank is close by in the same shopping center. Always have two people making the deposit.

• One person should exit the store with the second person remaining inside with the doors locked.

• Drive around the parking lot checking for suspicious cars or people. The person conducting the parking lot check should have a cell phone. If you see anything suspicious, drive to a safe location and call the police department.

• If all is clear, drive to main entrance; shine the headlights on the door. The other employee, with the cash, should now exit and immediately enter the vehicle. This is not the time to have a casual smoke before going to the bank.

• Proceed directly to the bank. Drive around the bank, again looking for anything suspicious. If all is clear, proceed to the drop box.

Your Deposit Is Missing

Many thoughts come to mind when you get the phone call from your company’s Treasury or Finance department advising you of a missing bank deposit. The first questions you ask yourself are, “Is it cash and checks or just missing cash, and were the checks deposited?” Was it an internal theft, or was the money taken by a bank employee? In the case of robbery at the deposit drop box, was it really a robbery? After you have interviewed the employees responsible for making the deposit and are reasonably comfortable that the deposit was made, it’s now time to call the bank.

Where’s My Money?

When you are investigating missing bank deposits, it’s key to remember that the money may be at the bank. One of the first steps is to call the bank and ask if it has any “unclaimed” funds for the date of your missing deposit. Banks keep unaccounted for funds for one year. At the end of their accounting year, banks will claim the money as assets of the bank. It never hurts to ask if the bank has unaccounted for or unclaimed cash on the date of your deposit; if so, the bank will give you the money.

When contacting the bank, ask for the branch manager. The bank representative should be willing to fully cooperate with you; you’re the customer. Ask questions regarding the processing of night deposits. Make careful notes of the answers to your questions, as during your investigation you may find that the bank is not following its own internal policies. Following are some questions to ask.

What Are Your Policies for Checking in Deposits?

Most banks require two people to check in deposits from the drop box. Both employees are required to sign the check in-log. Banks use a log sheet, recording the date and time your deposit was removed from the box and if the integrity of the deposit bag was intact. In one “missing deposit” case, the bank manager boldly stated, “My bank did not receive the deposit.” Two weeks later the same manager called stating the bank was crediting the missing funds. When asked why, he replied, “One of my tellers went on vacation, and when they returned, our deposit was located in one of their unlocked desk drawers.”

Where Are Deposit Bags Held While Waiting to Be Checked In?

Surprisingly, some banks keep your deposit on a counter or cart in the teller area of the bank while waiting to be counted. In one such investigation, when we were visiting the bank, the “checked-in” deposits were sitting on a counter within easy reach of bank customers. When this discrepancy was brought to the attention of the bank officials, our account was quickly credited, as they were in violation of their own internal cash-handling policies.

When Is My Deposit Verified?

Normally, banks verify deposits later in the afternoon and have a difficult time detailing what happened to your bag. In one such case, the bank received the deposit at 9:00 a.m., as verified by its check-in log. At 3:00 p.m. when the teller conducted the bag examination, prior to counting the funds, he found the cash portion of the bag ripped open and the cash was missing. The bank launched an investigation and discovered who took the cash.

Where Is the Deposit Verified?

If your deposit is not processed at the depositing bank, it is transported to an offsite location or “cash vault” to be counted. Take the time to make an appointment to visit and tour this location. If you can, visit the vault with your finance or operations executives. You may find discrepancies such a poor video quality of the cash count cages. On one tour, it was found that individual cash count booths were only on camera for a 3-second period, every 27 seconds, and cash counters were allowed to keep their coats and purses in their booths. When asked about the coats and purses, the vault manager stated that the union had fought to let the counters keep their personal articles in the counting booths, and the bank was unable to change its policies. Other security discrepancies were discovered, and our company quickly moved the account to another banking operation. Amazingly, our missing cash problems stopped.

How Long Do You Keep Your Trash?

Most bank policies require branches to bag and keep their deposit verification trash for 7–10 days. If you find the bank has not followed its own internal policy, you have an excellent chance of getting your credit.

When Was the Last Time a Physical Inspection of Your Drop Box Was Made?

Many times the deposit is still in the drop box. A bank in the Boston area advised that it would cost $1,000 to have the drop box dismantled to see if our six missing deposits were still in the box. (The actual cost to the bank to dismantle and inspect the box was $70.) They stated that if the deposits were found they would pay the costs, and if not, my company would be charged. After the drop box was opened, all six deposits were found. The practice of charging customers to dismantle the deposit drop box is becoming more popular with banks. The charge of $1,000 is the highest I have encountered. Usually, the cost, if any, is around $65. If a bank wants to charge for a deposit box inspection, it’s to discourage you from having the bank do it. If you have developed a solid business relationship with the bank manager, there should be no charge.

Involving the Police

A police report should be made regarding every missing deposit case. Managers have called and confessed to taking deposits after the police have left the store. Just the police showing up and taking an initial report has an effect and tells store staff that you take the matter seriously. Often, when talking by telephone to the person responsible for making the deposit, they ask, “Is it really necessary to involve the police?” This type of response may indicate the problem is at the store. After having this discussion, managers have called back within 15 minutes to say, “I made a mistake.”

When the police visit the bank, in response to your complaint to a missing deposit, they ask many of the same questions you do. Often, you will get a call from the bank after the police leave, telling you, “Your company is such a good customer; we don’t know if the deposit was made or not, but we’re going to credit your account.” From a law enforcement point of view, the last thing a bank wants is the police asking questions about its internal operations. It’s not that the bank has anything to hide; it is just uncomfortable with the whole process.

In Summary

It is important to remember banks have operational issues, just as your stores have. Make the effort to contact and introduce yourself to your bank security officials; they are there to help you solve your issues. In the rare instance when a bank branch is unwilling to cooperate, contact the bank’s security department. You will receive immediate attention to your problem. In one case, a bank’s deposit box had a loose screw on the inside. The screw, protruding about one-half inch, was in danger of snaring the plastic deposit bags as they traveled down the chute. The store manager stated he contacted the bank manager several times about the screw, and his efforts were ignored. After the store manager contacted the bank’s security department, the deposit box was repaired on the day of his telephone call. Remember, you’re the customer.

Best Practice: Shoplifting

Best Practice #1: Detaining Shoplifting Suspects

The only known “best practice” that applies to or in any way has been accepted in the Loss Prevention industry is the 1999 “best practice #1” propounded by the IAPSC, and its committee members who developed this “practice” include your authors.”

The International Association of Professional Security Consultants is issuing this consensus-based best practice for the guidance of and voluntary use by businesses and individuals who deal or may deal with the issues addressed herein.

A. Background

Definition: As used in this bulletin, the term “security person(s)” is intended to include only store proprietors and managers, store plainclothes security agents sometimes called “detectives,” and uniformed security officers also called “security guards” (either proprietary or contract). The term does not include sales clerks, maintenance persons, or stockers, for example. The term “security person(s)” is not intended to apply to off-duty public law enforcement or special police personnel unless they have been instructed by store management to follow the same procedures required of ordinary citizens, which procedures do not include police powers of arrest.

1. Shoplifting is a serious threat to the profitability of retail stores. Losses in stores from shoplifting amount to billions of dollars a year. The public is affected by the increases in prices resulting from shoplifting losses.

2. The ultimate purpose of security precautions in stores is to keep merchandise items in the stores unless they have been paid for by customers. Loss prevention practices and procedures both deter and detect the theft of merchandise. Detention for further arrest and prosecution is a last resort to be used only when other security precautions have failed to keep unpaid-for-merchandise in the store.

3. In almost all jurisdictions in the United States, merchants are legally empowered to detain shoplifting suspects for investigation and possible arrest and prosecution in the criminal justice system. This power is called “merchant’s privilege.”

4. In some circumstances shoplifting suspects are treated incorrectly by store management and security persons. Such treatment may cause results varying from simple mistakes to the violation of civil rights of suspects. If a best practice is not used, it is better not to detain a suspect than to risk the high cost of a civil liability suit. Two kinds of questionable detentions will illustrate this point. One kind applies to the customer who is truly an innocent party but whose conduct, for any number of reasons, led the security person to believe that a theft had occurred. People in this kind of detention are innocent victims of circumstance. The other kind applies to the customer who is not truly an innocent party, but for any number of reasons is not in possession of stolen merchandise when stopped by a security person.

5. Security persons usually do not actually “arrest” shoplifters but simply detain them for police authorities. Exceptions arise to this practice in those states where private persons’ arrest powers exist concurrent with but separate from the “privilege” statutes discussed previously. In these exceptional cases, security persons arrest after proof of the offense of theft.

6. Security persons cannot look into the minds of suspects. Security persons can only observe actions of suspects and completely and accurately report such actions. It is up to a judge or trier of fact to determine intent to deprive a merchant permanently of a taken item. See the discussion in 3.a. Step 6 exists to help the judge or trier of fact determine the intent of the customer because the cash registers inside a store are normally the last place a person would have to pay for an item before departing a store. Reports by security persons are normally detailed enough to include other observations which would tend to establish intent.

The International Association of Professional Security Consultants, Inc. (IAPSC) has examined the methods of detaining suspects recommended by security professionals and practiced by merchants throughout the United States. IAPSC sets forth in the following section what it believes to be the best practices.

B. Best Practices

1. Practice. Security persons using best practices detain a suspect only if they have personally seen the suspect approach the merchandise.

Rationale. The suspect may have entered the store with the merchandise already in hand or otherwise on or about his or her person (say, in a shopping bag or purse).

2. Practice. Security persons using best practices detain a suspect only if they have personally observed the suspect select or take possession of or conceal the merchandise.

Rationale. Security persons trust their own eyes and do not rely on reports by others.

3. Practice. Security persons using best practices detain a suspect only if they have observed the suspect with the merchandise continually from the point of selection to the point where the suspect has gone beyond the last checkout station without paying for the item. If the surveillance has been broken, or if the person has gotten rid of the merchandise, the security person breaks off following for that offense but may continue surveillance if it appears the suspect may commit theft again.

Rationale. The suspect may have “ditched” the merchandise or concealed it. By continually observing the suspect, the security person can observe whether or not the suspect still has the merchandise even if it has been concealed on the suspect’s person.

4. Practice. Security persons using best practices detain a suspect outside the store after the suspect has passed the last checkout station and has failed to pay for an item of merchandise. At this point security persons using this best practice immediately investigate to verify or refute a suspect’s claim of innocence. Special care and consideration are exercised when merchandise is displayed for sale outside the store, such as garden supplies, sidewalk sales, etc., or which is displayed for sale inside the store, but beyond the last sales point.

Rationale. The security person does not do only what is required to meet the minimum requirements of theft laws. The actions of a suspect make it easier to prove intent to deprive the merchant of an item of merchandise. The farther from the actual taking a suspect is detained, the clearer the offense will appear to a judge or trier of fact. The security person is aware of suspects who might claim they were looking for a matching item or looking for someone to give an opinion on the merchandise before it is purchased. A suspect may, however, offer a logical explanation for actions that initially appeared to the security person to be acts of shoplifting, but which may require only a limited investigation to verify the suspect’s explanation.

5. Practice. Security persons using best practices normally do not “chase” suspects by running inside a store or in shopping centers that are occupied by customers. Exceptions occur when necessary, but only in such areas as parking lots, and then only when few people are in the area and it is unlikely a bystander could get hurt. Such foot pursuits never leave the property on which the store is located. If a suspect runs, the best practice is for the security person to make a mental note of the appearance of the suspect and the merchandise that appears to have been taken and then to make a written report for the store’s files.

Rationale. Running may create more problems than it solves. When a suspect runs and a security person chases that person by also running, clients and employees of the store and store employees are endangered more by the combination of two persons running than by the suspect’s running alone. Handicapped clients may be knocked off their feet. Wheelchairs may be overturned. Store employees who may intervene to help may be injured by security persons in pursuit, or by running into counters or display devices, or by slipping on polished floors. When clerks leave their posts, they leave their own merchandise exposed to theft. An exception to this best practice may exist when it is necessary to chase down a suspect to protect customers and store employees from ongoing violence by the suspect.

6. Practice. Security persons using best practices treat suspects equally and fairly regardless of a suspect’s race, color, creed, gender, or national origin.

Rationale. Anecdotal information suggests certain groups have been marked by some store management and security persons for more surveillance and/or more aggressive antishoplifting measures. Color, religious or national dress, gender, and “race” are alleged to have been used to identify persons in such groups. However, there is no scientific evidence regarding the validity of such “profiling,” and this practice is avoided by security persons using best practices. Suspicion of shoplifting depends on observed actions, not appearance. All law-abiding persons have the right to be treated the same as any other person in the marketplace.

7. Practice. Security persons using best practices do not use weapons such as firearms, batons (“nightsticks”), or restraining devices such as thumb cuffs, “come-alongs,” mace, or pepper spray in order to apprehend or detain a shoplifting suspect. Stores using best practices occasionally permit the use of handcuffs by security persons whose training has included instruction in the proper use of handcuffs when necessary to prevent injury to customers or store personnel. Security persons using best practices use handcuffs only when a suspected shoplifter is physically threatening violence or otherwise resisting detention; or there is, in the good judgment of the security person, the risk of imminent serious harm absent their use.

Rationale. There is no merchandise of such value that it warrants a security person’s injuring a suspect or an innocent customer. Use of weapons and restraining devices except handcuffs should be left to on-duty public law enforcement officers. If it is not possible to get the suspect’s willing cooperation, it is better to let the suspect go free than to risk injuring a suspect or other customer. Risk avoidance is a factor considered in apprehending and detaining suspects. Because handcuffs are restraining devices, they can be painful if improperly applied and can cause injury. Not all persons caught need restraining. Many people caught shoplifting are humiliated by the incident and are cooperative; hence, in such cases restraint is not necessary.

8. Practice. Security persons using best practices limit the use of force to “holding” or “restraining” to effect a detention. Security persons using best practices do not use actions such as striking, tackling, sitting on a suspect’s body, or any other action that might cause physical injury to the suspect.

Rationale. Use of force is subject to criticism, and assaultive use of force is typically unnecessary and unacceptable in the private sector. However, some holding or restraining may be necessary lest potential thieves learn that by simply resisting they may come and steal with impunity. Use of limited holding or restraining force is sometimes necessary to detain a suspect until police arrive, or to prevent a suspect from injuring security persons. Under no circumstances should the force applied be that which may result in injury or death to a suspect. No merchandise is of such value as to justify physical injury to a suspect. The better practice is to allow the suspect to depart the premises rather than to cause any injury by the use of force in detaining the suspect. Assuming the suspect can be identified, the merchant can file a complaint; then the public police have the option of apprehending the suspect at a later time.

Legal Notice/Disclaimer: Copyright © 1999–2006. The International Association of Professional Security Consultants (IAPSC), All Rights Reserved. The IAPSC makes no representations concerning the guidelines contained herein which are provided for informational and educational purposes only, and which are not to be considered as legal advice. The IAPSC specifically disclaims all liability for any damages alleged to result from or arise out of any use or misuse of these guidelines.

Bomb Threats

Bomb threats are generally received by larger big box stores rather than the “Mom and Pop” stores. The reason is that the larger stores not only provide more opportunity and locations for hiding bombs but also because they have the potential for paying larger amounts of money when bombs are planted for extortion purposes. Why are bombs planted within retail establishments? There are several possible reasons:

• To create a situation which demands a store evacuation, sometimes done to provide an employee legitimate time off or by an outsider who gets satisfaction from the excitement such situations create.

• To create confusion or uncertainty within a store, which, if it receives publicity, may lead to reduced sales; this situation has been known to be a technique used by disgruntled employees or those who are in the midst of divisive labor negotiations.

• To create confusion and disruption to achieve some sought-after objective by an advocacy group, such as the animal rights organizations, who seek an objective of the discontinuance of fur sales.

• As a means of creating fear for extortion purposes.

• Security personnel have also been known to have been responsible for bomb threats (and fires) and then become “heroes” when they “discover” the threat.

How should bomb threats be dealt with? The answer depends on a variety of factors. You must attempt to verify the reliability of the source of the threat. Was it by phone or letter? Was there specific information regarding the nature of the device or the reason it was allegedly planted? Any written letter, envelope, or note should be handled with care to preserve any evidentiary value it may have.

The level of the threat must be assessed. If the threat is carried out, who would be harmed and how badly? Is the threat against people or property? How easy would it be to get access to the threatened target? What is known (or can be learned) about the person making the threat and his or her motivation for doing so?

Let me describe some actual cases and how they were handled.

In the first case, an individual who was a member of a bargaining unit and was, unfortunately, one of the last persons hired for Christmas help was also one of the first persons laid off after the holidays. Shortly after being laid off, this person lost his girl friend, was thrown out of his apartment for failure to pay his rent, and had his car stolen, which contained most of his personal belongings. He was then rehired again but, after a very short period of employment, was laid off again. He blamed the company for his misfortunes and was heard to say when being laid off the second time that he was going to get a gun and shoot up the Human Resources department.

When this information came to light, we had some decisions to make. We obviously had a responsibility to keep the members of the HR department from harm. We decided to do several things to help us assess the level of the threat and its likelihood of performance. We immediately initiated a thorough background investigation of the subject and learned the subject had previously been successfully prosecuted for a weapons violation and was a likely narcotics user. This investigation was completed within 4 hours; we determined the subject had the ability to perform and the level of threat was quite high.

Our next step was to locate the subject, who was now living on the street. We established surveillances (we obtained extra manpower from outside agencies) on places where the subject was likely to show up. We utilized a recent photo taken for his employee ID badge. We also hired armed off-duty police officers to maintain a stakeout of his former work area in the store and the HR area.

Out subject was located within 24 hours, and we maintained a round-the-clock surveillance of him for the next 2 weeks. With the first few days, we discontinued the surveillances within the store, but we were in radio contact with the surveillance teams working the subject. We arranged for armed response if the subject got within one block of the store.

The entire effort was terminated after 2 weeks because the subject showed absolutely no indication he intended to do us any harm and, in fact, had obtained employment some distance from our store. An agent who was able to converse with the subject at a bar was convinced the subject had no intention of carrying out his threat.

Our efforts in this case cost the company about $40,000. However, in such cases cost should not be an issue; the company’s legal liability was tremendous, particularly with the foreseeability which existed.

The second case involved an employee who literally jumped over the personnel manager’s desk during his termination interview and began beating the female manager with his fists. Her cries drew help, and the employee was arrested, charged with battery, and imprisoned. The personnel manager was sent to the hospital for treatment and released.

We ascertained the suspect would be released from the city jail with a day; we then established a surveillance at his residence. We also posted armed off-duty police in the HR area of the store.

We then learned that the subject intended to leave the state as soon as he was legally permitted to do so. We worked with the district attorney and our subject’s attorney to facilitate his move and were able to conclude our protective services at the end of a week. It was also important in this case to spend a considerable amount of time with our personnel manager reassuring her that she was safe and her home was also secure. Again, we had arrangements made to respond to her home if the subject moved in that direction, but we also had every reason to believe he did not know where she lived and that he would not be able to easily obtain that information.

The final case was not really a threat but rather an “incident.”

At a major company function, an employee, about to retire, ran up to the stage, grabbed the podium microphone, and began exhorting the audience to listen to some imagined wrong he had suffered. The master of ceremonies was able to get the mic back, and since the event was just about over, our subject proceeded to corner our chairman and tell him his story. Security responded and removed the chairman from the area. No threats were made, but the incident did shake up several people, and the question arose as to what further action might be expected from our retiring (or not so retiring) employee.

Our objective in this case was to protect our chairman from any untoward incidents. We again conducted a background investigation of our subject; he had no criminal record. We determined that, while he was quite vocal, he was not a violent person. We did alert the local police in the town where the chairman lived and arranged for extra police patrols of his residence. In this case, that was the extent of our efforts.

In most cases, threats from outsiders or nonemployees are harder to deal with because it is more difficult to obtain detailed information about the subject.

Whenever these types of incidents arise, they should be handled in such a manner as to protect the individuals involved with as little disruption to their normal routine as possible. We must also, while protecting the company and its personnel, protect the privacy of the subjects, since, in many cases, they have committed no crime. True, they have made threatening statements (which do not rise to the level of an assault) or taken some legal but disquieting action which gives rise to potential harm. Through the use of normal investigative tools and resources, most such threats can be neutralized, people and property protected, liability limited, and one hopes, the subjects will never know how much attention they have attracted.

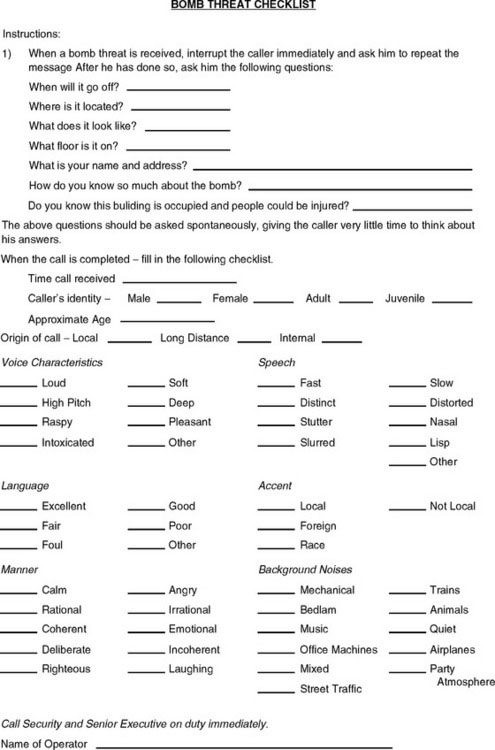

In the case of bomb threats, which arrive either by letter or by phone, we must attempt to ascertain as much information about the threat as quickly as possible.

If the threat specifies a location where the bomb is planted, that area should be discreetly cordoned off (a water leak can be used as a nonthreatening reason for the area’s evacuation), and a search for any suspicious packages should be made. Persons doing the searching should be cautioned that, if anything suspicious is found, not to touch it or attempt to move it, both for safety and evidentiary reasons.

The police should always be alerted to any bomb threats received, and if a suspicious package or device is found, they should be the ones to deal with it.

The question always arises as to whether to evacuate the store. Generally, stores are not evacuated based on a threat only unless, of course, there is other information which makes the threat more creditable. This decision is a management decision, one hopes, made after consultation with security personnel or the police. Experience has shown the police will not recommend evacuation if a search is underway. If a device or suspicious package is found, an area within a radius of 300 feet should be cleared. If the police recommend evacuation, their advice is normally followed, recognizing that store management must make this decision.

We suggest that, for larger stores, a “bomb board” be created. This board, located in a management office, consists of a series of 3 × 5 search cards, each defining a specific area and/or objects (e.g., trash receptacles) to be searched. These cards should be distributed to those conducting the search to assure that no search area will be missed. Every effort should be made to use volunteers for the search who are familiar with the search area and can recognize which “do not belong.” The bomb board also contains the procedures to be followed when bomb threats are received.

Recommended procedures are as follows:

1. Complete the Bomb Threat Checklist (see Figure B-3). Record all descriptive data about the caller, such as age, sex, mannerisms, accents, exact words used, etc.

2. Person receiving the phoned bomb treat should be attentive for any identifiable background noises.

3. Person taking the call should press the caller for a specific location of the bomb and/or the general area of its location. Attempt to keep caller on the line as long as possible.

4. If a device is found, and it has been determined to evacuate the store, such evacuation should be done in a manner that does not create a panic. We suggest the following language:

This message should be repeated twice. If the building is evacuated, the building must be properly secured and all cash registers must be closed and locked. In addition, any cash rooms, vaults, safes, etc., should be secured.

It must be kept in mind that bombs may also include incendiary devices.

One of your authors had the experience of dealing with five incendiary devices planted in three stores in the greater Bay Area between Thanksgiving 1989 and January 1990. The devices were designed to start a fire, not explode. An investigation by store security, local police, and federal agencies never produced positive identification of the person(s) responsible. It was established, however, that the devices were constructed identical to devices described in a United Kingdom publication promulgated by an activist group; it was only because our devices were made with a minor flaw that none ever reached their intended potential.

In this situation, we notified all store personnel at all nearby locations of the problem and sought their assistance in being alert to and reporting any strange or seemingly out-of-place objects to store security. We also prepared and had a senior security executive give a TV news interview in which he stated: “A nonexplosive, fire-starting device was found in (store named) today. It was discovered in the furniture department by our security personnel, who are familiar with this type of incendiary device. As a purely precautionary measure to ensure the safety of our customers and employees, who were not in any immediate danger, we evacuated the floor. The device was then removed by ATF [Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms], a federal agency.

BURGLARY (24-hour stores, e.g., Convenience Stores, Gas Stations, Drug, Grocery, and Liquor Stores)

“Commercial burglary” is generally defined as the unauthorized entry by force or stealth into any portion of a business for the purpose of stealing anything of value or, in some states, committing any felony.

Today, the majority of convenience stores and gas stations operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Some drug, grocery, and liquor stores also remain open around the clock. As such, except for stealthy trespass into stock areas or break-ins of isolated storage areas or sheds, they are not subject to commercial burglary risks. Even when planned to operate 24/7, however, they may be at risk if they close on a holiday, or in the event of a weather or other emergency. And some stores do, of course, have non-24-hour operations or regular closings.

There are two primary defenses against a burglary: physical barriers to deter or slow entry and measures to detect a break-in if it does occur and summon appropriate response. Most burglars enter through an existing door or window.

While most owners can’t do much about the plate glass windows and glass doors common on the front of stores, side and rear doors and windows are another matter. Such doors should

• Be of hollow metal securely attached to a metal doorframe, which should be firmly attached to the building walls (the door “system” is only as strong as its weakest part).

• Use a spring latch, plus a key-operated deadbolt with at least a 1-inch bolt throw. A latch-guard should cover the locking area.

• If possible, use one or two hand-operated bolts or bars attached to the inside of the door to increase its resistance to forceful entry.

Check for other “easy” openings into back areas, such as windows, which can be broken, and wall-mounted air conditioners, which can be pushed in. Both should be replaced with cinder block or other solid building materials. Check for exterior entry restrooms that may have drop-ceilings, permitting entry into the store, or roof entry points.

Safes, including time-delay safes, should be bolted or cemented to the floor to prevent their being simply taken away for later break-in.

High-value stock such as cigarette cartons should be stored in interior “safe rooms” equipped with locked doors.

Slowing down a burglar doesn’t do any good if he or she still has hours in which to commit the crime. Detection of entry is essential. Magnetic alarm contacts on the doors, including interior “safe rooms,” is a basic requirement. Front doors should also be equipped with glass-break tape or sensors. They should be supplemented with interior motion detectors in the front sales area and the rear stockroom area. Do not rely on an alarm signal being transmitted only over the store’s telephone line. Backup signals can be sent using either a radio signal or by cell phone signal. Consult with your alarm company to ensure that, when you need it, your alarm signal will be transmitted under any circumstance. All except the most amateur burglars know to cut the phone lines before trying to enter.

In some situations, stores routinely close using roll-down type metal covers to protect their front doors and windows. These are good, but still need backup at other possible entry points, plus alarms to detect and report any actual intrusion.

Because they are usually not present, the risk of injury or death to employees or customers usually doesn’t exist in a commercial burglary. Damages to the building and loss of stock can, however, severely cripple or even bankrupt the business. If a burglar can’t be deterred by a business’s security measures, detection devices can often summon police or contact security response in time to reduce losses, or even apprehend the burglar before he or she escapes.