C

Cables

The use of clear plastic-coated 1/8- or 3/16-inch steel airplane cable to secure expensive ready-to-wear (RTW) merchandise to fixtures is an effective antitheft technique. The cables are placed through a sleeve, passed over the fixture hanging rod, and have loops at each end which can then be secured together with a small padlock. This arrangement prevents the merchandise from being removed and carried away from the fixture. Merchandise typically secured by this physical control strategy means includes leather jackets and men’s suits.

An alternative to the preceding technique is using cables with one end with a ball-like fitting, which in turn fits into a slot in a lockable box-like receptacle. When this arrangement is used, the ball end of the cable is inserted through the loop and then secured in the lockable receptacle.

A third variation of cable-securing devices is the use of small diameter (1/16 or 3/16 inch) electrical two-conductor cable, which connects into a fixture that completes an electrical circuit when the cable is in place. The cable is affixed to the merchandise in the same manner as the nonelectrical cable. If, however, the cable is cut or otherwise removed from its retaining receptacle, an audible alarm sounds, alerting sales associates to the fact that some merchandise is no longer secured.

Modified forms of both the electrical and nonelectrical cables are frequently used to secure electronic equipment such as laptops, digital cameras, and other expensive electronics.

Case Management and Electronic Incident Reporting

In recent years, we have seen an explosive growth in the area of loss prevention (LP) technology. Retailers are choosing to implement expensive solutions like digital video systems and exception-based reporting software in hopes that these solutions will help investigators to control shrink more effectively.

Recently, loss prevention departments have begun to invest in centralized incident reporting systems. Incident reporting tools can help an organization to collect, process, and analyze incident data in a way that traditional methods cannot offer.

Elements of an Incident Report

Regardless of whether an incident report is completed on paper or electronically in an incident reporting system, it includes several universal elements:

• Who: The report contains information about the principal subject and witnesses. This typically includes contact information and a review of that person’s involvement in the incident.

• What: Details about what happened. Generally, this is in narrative form and is written by the report taker. Often witness statements are included in the incident report.

• When: What date and time the initial incident occurred as well as other major milestones (i.e., interview and court dates).

• Where: Information about where an incident occurred. This would include street address, physical location within a store, etc.

Loss prevention professionals are probably very familiar with writing incident reports for the typical shoplifting and internal theft cases. Almost all reports contain who stole it, what they stole, when they stole it, where they stole it from, and why they stole it.

Interestingly, this same methodology is used by many other departments in the retail organization. For example, the human resources department typically handles reports of violation of company policy. The human resource representative’s report will include who violated the policy, what policy they violated, when they violated the policy, where they violated the policy, and why they violated the policy.

Another example is the risk management department. This department is typically tasked with providing a safe work environment but is also responsible for processing customer and employee accident reports when things go wrong. Who had the accident, what kind of accident occurred, when did the accident occur, where did the accident occur, and why did the accident occur?

Get the idea? Incident reporting systems are not just for loss prevention. The flexibility provided by many solutions allows for the system to be utilized by other parts of the retail organization. Incident reporting systems can help the risk management team to manage accident reports just as easily as it can help the loss prevention group to manage theft investigations.

Benefits of Electronic Incident Reporting

Besides the ability to store incident data for many different groups within the retail organization, an incident reporting system has several other benefits. Most importantly, an incident reporting system has the ability to store the incident data in an electronic format at a central location. This seems obvious, but it actually represents the fundamental difference between centralized incident management and traditional methods of collecting and storing incident data. The data collected by an incident reporting system (database) can be a very powerful tool.

Incident reporting systems can be configured to interact with other business systems, such as

• Internal employee databases: Link to the HR department’s employee master file for enhanced statistical reports.

• Civil collection providers: Transmit theft incidents electronically to the collection agency.

• Background screening providers: Transmit a prospective employee’s (or suspect’s) information to the vendor and order a background check.

• POS exception-based reporting tools: Start an incident from within an exception-based reporting tool.

• Digital CCTV systems: Easily attach video clips to an incident report.

The database can be used to generate statistical reports that can help an organization to gauge various metrics. When combined with other data sources, the data in the incident reporting system can be used to identify trends that otherwise would not be visible.

For example, when linked with data from an HR system, it would be possible to pull a report to analyze the relationship between store shrink, employee turnover, and theft incidents. Another possibility would be to analyze the department in which a suspect was first observed compared to the time of day in shoplifting cases. These types of reports would require significant resources if compiled by hand, but with the use of an electronic incident reporting system, the data are easily accessible.

Pitfalls of Incident Reporting

The benefits of using a centralized incident reporting system can be numerous but require more than just a financial investment in order to be achieved.

The successful implementation of an incident reporting system requires planning, communication, and follow-through. During the implementation process, it is important to maintain partnerships with the departments that will be utilizing the system, the IT department, and the vendor’s technical staff. With communication, the vendor can provide a solution that is tailored to the needs of everyone involved.

After a solution is implemented, it is critical that management support the system. It is important that managers train end users on system operations. No matter how easy the system is to use, end users should be taught the proper way to input, retrieve, and report on incident data.

Finally, it is important that the system be kept up-to-date with changes in corporate policies. Invariably, with time, things change. Make sure that the system is reconfigured as needed to accommodate these changes.

Cash Control: Automated

One much-repeated maxim in the loss prevention community goes something like this: “The more rapidly cash tender is recycled or deposited, the lesser the risk of cashier error and internal shrink.” At the same time, especially with retailers who see a high volume of cash transactions, the labor expenses and bank fees associated with handling cash are consistently on the rise. So how can retailers impose measures to control cashier errors and reduce theft, while stemming the increase of labor expenses and bank fees?

The issue becomes how to build the infrastructure to return the highest efficiency possible for cash management while striking a balance between the use of manpower and affordable technology. Finding the right formula will positively impact any end user retailer’s return on investment (ROI). This business problem led New Albany, Indiana-based FireKing Security Group to develop and bring to market the “PerfectCash” comprehensive cash handling solution suite with both hardware (safe with cash recycler) and software elements, all tied together with IP/LAN-based reporting capabilities (see Figure C-1).

PerfectCash takes cash handling and revenue room activities to the next level of security, efficiency, and automation. According to the company, the PerfectCash solution is “ideal for large retailers, department stores, and mass merchandisers who routinely process tens of thousands of dollars in cash each day.”

The vision behind PerfectCash is to move cash collection and processing functions closer to the point-of-sale, which serves to reduce double handling, errors, and opportunities for employee theft. PerfectCash is an enclosed system (similar but smaller scale than that of a bank or back office casino process), combining the preparation of opening tills, verification/preparation of end-of-day deposits, and general ledger reporting.

Via the automation of these processes that PerfectCash enables, end users of the solution, including one of the nation’s largest operators of department stores, have realized cost-labor savings that equal many times the purchase price during the first year of installment. With PerfectCash, there is also the added issue of the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act of 2002. PerfectCash give retailers added control over accounting and treasury functions, which leads to smoother compliance with SOX financial audit and reporting requirements.

Benefits to retailers who implement Perfect Cash are as follows:

• Reduced labor for deposit preparation

• Check truncation (Check 21 compliant)

• Reduced change order size and frequency

• Accurate and quicker deposits

• Automated and accurate “make ready” for registers

• Interface to back room settlement software providing real-time information about cash/check activity

By way of example, FireKing recently provided Macy’s West a customized PerfectCash solution for automating the deposit process and creating register replenishments, reducing processing time by 50%. PerfectCash can combine all the functions, and it works in a similar (but smaller) scale than that of a bank or back office casino process. Savings are realized through reducing the time to process and increasing accuracy.

For more information about PerfectCash, contact [email protected]

Cash Office Security

Nearly all retailers, large and small, have what serves as a cash office—a place where not only cash is kept, but in many cases accounting records, invoices, employees’ schedules, and other miscellaneous business records as well.

All cash offices have some sort of cash storage container, ranging from massive and alarmed safes to simple locking file cabinets, which many or may not have a “lockable strong box” for the cash itself.

Cash offices are as varied in their design and construction as the type of merchandise sold by a big box retailer. Small “Mom and Pop” retailers often use a walled or curtained-off area of the “back room” for a cash office. A major national department store may utilize a room built almost to the standards of a bank vault, complete with bulletproof glass, bulletproof walls, and a “bandit barrier” entrance. We should point out that, while there is normally only one way of ingress and egress into a cash vault, there should exist a breakout panel somewhere within the cash office so that in the case of a fire or other emergency, there is a means of escape.

A “bandit barrier” is a double door (inner and outer door) entrance with a small space between the doors. This is also known as or is called a “man trap” configuration. The doors are electrically controlled from inside the cash office (vault). Each door has a small window so the person seeking entrance (after pressing the “doorbell” to announce his or her presence and desire to enter the vault) can be visually identified. The outer door is electrically unlocked, and the visitor enters the interior space between the doors, closing the outer door behind him or her, since the inner door cannot open if the outer door is also open. Once inside the “barrier,” the inner door is then “buzzed” (unlocked electronically) open. More sophisticated vaults also have a phone by the outer door to the bandit barrier (with a corresponding phone just inside the vault by the inner door). This arrangement permits the person seeking entry to announce the purpose of his or her need for entry, which is a step beyond mere visual identification.

Grocery stores and some drug stores (and some other specialty stores) place their “office” on a raised platform above the store floor level; this office is enclosed on at least two (generally three) sides with windows at a height at which someone seated at a desk within the office can see through to the selling floor. This office generally serves as both a cash and paperwork space, as well as the store manager’s office. The fact that it is raised above the selling floor level permits anyone working in the office to observe the activities on the selling floor. In this scenario, the bulk of the store’s cash is kept in a floor safe and/or a heavy standard safe located near the front windows of the store. The floor safe is buried in the concrete of the selling floor and is extremely difficult to break into. The standard safe, which is on the floor generally, has a time lock and requires two keys to open in addition to the combination lock. One key is held by the store and one by the armored car pickup driver. The time lock prevents the safe from being opened except at specific times during the day, even if the proper combination is used. Many of these safes also have an electronic alarm, which is activated if the dialed combination is dialed incorrectly. For example, if the last number of the correct combination is 30 and the number 40 is intentionally dialed instead, this will automatically send a hold-up signal to the alarm monitoring company.

In large stores, where a vault-like cash office exists, we find no objection to leaving the main safe door closed, but with the combination in an unlocked position. In smaller stores, which do not have a vault-type cash office, we suggest that the safe be kept locked at all times. We must mention one caution here: The combination to any safe in the vault needs to be memorized. If the combination to the safe must be written down, it should be kept in a sealed envelope in an office away from the cash office, for example.

If any portion of the cash office serves an area where customers can obtain refunds, cash checks, and/or pay bills, we then suggest that drawers be built under the counter of the service window and utilized for the receipt and disbursement of cash. Such drawers should be equipped with a “hold-up” alarm triggering device. This device may take the form of a “finger pull” switch or a “bill trap,” a device which holds a piece of currency that, if removed, triggers the silent alarm. At one time “kick-bars” located on the floor, which could be activated by a cashier’s foot, were popular, but they have fallen out of favor because of the high rate if accidental false alarms. Cashiers and other vault personnel must be trained, however, as to conditions and circumstances under which these alarms should be triggered. They should be taught never to do anything which may provoke the robber. Their best course of action is to carefully observe the robber and get a good physical description, which can later be given to the police, utilizing the Robbery form (which is found in the “Forms” section of this book). Training on the proper actions to take when being held up should be periodically reviewed with all personnel, particularly new cash office employees.

Periodic audits of all with funds and a cash office should be made. We do not suggest the frequency for these audits; that should be determined by the chief of finance or head of the internal audit department. We do suggest, however, that when an audit of the funds in the safe is done, each bill in a bundled (banded) stack be counted. It is not unheard of for an employee in the cash office to steal funds by removing one or two bills from each bundled stack. If the bills in a bundled stack are not individually counted, such thefts could go undetected for extended periods of time.

Cash offices should be adequately alarmed. It is beyond the scope of this book to provide specific details with respect to such alarms, but suffice it to say, a qualified expert should be consulted to determine the most effective way to accomplish alarming the cash office.

It should also go without saying (but we will anyway) that all employees who will have access to the cash office be fully vetted.

A final word about cash deposits: We discuss in the section “Escort Policy and Procedure” (elsewhere in this book) their use when making bank deposits. However, we strongly suggest that if any significant amounts of money are involved, the use of an armored car service be considered. We have seen too many cases where, in the interest of saving the few dollars involved in the cost of an armored car service, the store owner or an employee personally made bank deposits only to be robbed going to or coming from the bank, and in many cases, was injured as well. We do not suggest being penny wise and pound foolish.

Cash Register Manipulations

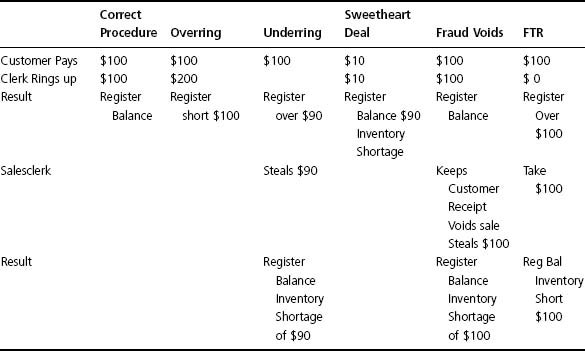

Table C-1 demonstrates the results of various types of cash register manipulations by dishonest employees acting alone or in concert with others.

To use this chart to understand cash register manipulations, you must use the left column in combination with the various situations along the top row of comments. For example, for the Correct Procedure, read down the column noted as “Correct Procedure,” while noting the actions of the customer and clerk on the left column. If the correct procedure is followed, the customer will pay $100 for $100 of merchandise, which results in a balanced register.

Consider, however, the results when a “Sweetheart Deal” (one in which the clerk sells a friend merchandise below the actual value of the goods). Here, the clerk sells $100 of goods for $10, which results in the clerk ringing up $10, causing the register to now balance. However, since $100 in merchandise left the store for a payment of only $10, the store now has a $90 inventory shortage. The other manipulations shown can be followed in the same manner.

CCTV: An Historical Perspective in Retailing

The use of visual surveillance by closed-circuit television (CCTV) in business began in the 1960s. Initially, the cameras were large and quite expensive. In large department stores, the initial use of a camera was for internal investigations. Even large chains had only one or two cameras. Smaller retail establishments (such as grocery and drug stores) also used CCTV as an antishoplifting device. Usually, the retailer would install one or two working CCTVs in a manner so that customers could view themselves on a nearby monitor. “Smile, you’re on candid camera” signs often hung beneath the monitors; other decals announced “This store utilizes closed-circuit television.” This arrangement sought to achieve two objectives: (a) Notify customers about the CCTV to minimize invasion of privacy complaints and (b) imply to the customer that other, less obvious cameras were monitoring and detecting illicit activity throughout the store. In actuality, most if not all other cameras were “dummies,” i.e., simply plastic camera body shells with ersatz lenses, blinking red lights, and wires simulating a working camera. The high cost of live CCTV necessitated this approach.

During the intervening 40 plus years, the development of CCTV paralleled the sophistication, miniaturization, and cost reductions reflected in the electronics and computer worlds. Today, color CCTV cameras are as small as a box of matches or the cap of a fountain pen. Their pictures can be transmitted to monitors over almost limitless distances via coax cable, telephone lines, microwave, optic fiber, and just plain wire. Monitors can display images from a dozen cameras simultaneously. Video tape recorders (VTRs) can now record the cameras’ images for periods up to 24 hours on one tape; the newest equipment is computerized digital VTRs, which can record on floppy disks and CDs over long periods of time. Modern cameras are capable of panning, tilting, and zooming in on a target, either by manual control or computerized response to predetermined events, such as motion or alarm signals.

Together with the technical developments of CCTV equipment and the significant reduction in its costs, new and effective uses of CCTV are constantly being found. CCTV is used by the Golden Gate Bridge to monitor traffic; by hotel lobbies, museums, and Amtrak stations to monitor patrons; by parking lots and garages to detect criminal activity; by bank ATMs as both a robbery deterrent and to identify those using the machines. Hundreds of businesses, from casinos to convenience stores, utilize CCTV for surveillance and security purposes.

Retailers have found CCTV valuable in not only deterring and detecting shoplifting, but also in investigating and documenting internal theft. They found that stores which installed CCTV had a perceptible drop in theft from shoplifting. One security agent, by monitoring an adequate number of properly placed cameras, could observe virtually the entire store, thus saving manpower costs.

Over 83% of retail establishments of all types utilize live CCTV. Today, retailers plan for CCTV installation in the same fashion as they do for cashiering facilities, merchandise displays, service areas, etc. Computer-controlled cameras are contained in opaque domes in ceilings; it is common to find major stores with dozens of cameras and CCTV monitoring rooms containing banks of dozens of TV screens, any one of which can be switched to a large viewing screen whose picture is simultaneously recorded. I have personally planned numerous such installations, recently having done so for the campus bookstores at major universities such as Stanford, Duke, and the University of California at San Diego. Retailing establishments found that CCTV perceptibly reduced shoplifting. More importantly, when shoplifting, robbery, burglary, or internal theft did occur, what better evidence to help convict the thief than videotape of the person actually committing the crime.

In retailing, CCTV performs many functions:

2. As a means of detecting theft

3. As an investigative tool, especially with regard to internal theft and fraud

5. As a means of preserving evidence of events which may later become the subject of litigation

The question is often asked what triggers a shopper becoming a subject of CCTV observation and monitoring. The answer is that many things can legitimately result in observation by a loss prevention agent monitoring the store’s CCTV system. Among these “triggers” are

• Random monitoring which results in loss prevention recognizing a person as a previously suspected or known shoplifter

• Random monitoring which results in the observation of suspicious behavior by a shopper, which may include:

While the retail industry was the first major user of CCTV for security purposes, its value as a crime deterrent was quickly recognized by others, and its use began pervading all aspects of society, as was alluded to earlier. It has been reported that the UK has found street surveillance by CCTV to be an effective crime deterrent, and such use is being proliferated throughout England. American businesses are also finding value in utilizing CCTV to surveil parking lots and building exteriors; CCTV is being used and can be seen (and in some cases not seen) in venues ranging from sports stadiums to casinos.

The continuing drop in CCTV prices has also contributed to the increased utilization of this technology. The use of miniaturized and disguised CCTV cameras connected to home VCRs (or the use of self-contained “camcorders”) has popularized the use of this technology by parents to monitor the activities of baby-sitters left in charge of their children in the parents’ absence.

We cannot discuss the widespread use of CCTV without concomitantly discussing the legal aspects of its use. The emphasis, increasing exponentially, on privacy rights has brought the increasing widespread use of CCTV into question from a privacy standpoint.

The consensus is, at least at the present time, no right to privacy exists when the subject of visual surveillance is in a public place. Obviously, covert surveillance in private areas of public buildings, such as restrooms and fitting rooms, is illegal. Even private office spaces, if occupants have a key and can lock the door, or otherwise make the case that they had a reasonable expectation of privacy, are more than likely off-limits to covert CCTV surveillance. Any time covert CCTV surveillance is planned, care should be taken to ascertain its proposed use is legal, and the opinion of knowledgeable legal counsel should be obtained. We must also emphasize that our discussion involves only visual surveillance; audio surveillance is an entirely different matter and brings into play a whole new set of rules, laws, and restrictions.

So what does the future hold with regard to visual public surveillance in general and the use of CCTV in particular? In our view, the foreseeable future will see increased visual surveillance. Technical developments, coupled with the increase in security needs of all sorts after September 11, 2001, foretell the ever-increasing use of CCTV by both the civilian, law enforcement, and military communities. We read of surveillance drones replacing manned surveillance aircraft in Afghanistan; we’ve seen TV shots of the wall-to-wall coverage by CCTV at the Winter Olympics and Super Bowl XLI; we see more advanced uses of technical surveillance such as facial recognition in use at public events and suggested for widespread use at airports to detect and deny access to aircraft for persons on official watch lists. If September 11, as horrendous as it was, had one good result, it was that “security” is no longer a dirty four-letter (times 2) word. This increased emphasis on security throughout the world can only harbinger the ever-increasing use of reasonable surveillance in all aspects of our lives, and in my view, a willingness of a vast majority of the public to forgo some privacy for increased safety.

Celebrity Appearances and Special Events

One aspect of loss prevention, although not common, is the need to address protection considerations when “celebrities” either visit stores or the retailer plays a significant role in such appearances.

Your authors have been responsible for the security at large “special events” (many for a local charity) and/or smaller personal appearances, both of which involved the presence of celebrities. In some cases these events involved multiday activities including fashion shows at local venues outside the store. This complicated the security aspects because large quantities of expensive merchandise (RTW, furs, fine jewelry) would have to be moved and stored (sometimes for several days) at a remote location, where it would be exposed to perhaps dozens of models, make-up artists, and other nonstore personnel. In other cases, the simple appearance of a celebrity (e.g., Elizabeth Taylor, Cher, Christie Brinkley, Catherine Deneuve) in the store created security problems ranging from crowd control to the physical protection of the celebrity, who, in some cases, was a vocal advocate for very controversial causes. Often, a private reception followed the celebrity’s public appearance, which added unique considerations.

Some celebrities have their own security personnel with whom a working relationship must be established. It is essential that “who will call the shots” must be sorted out in advance to prevent disagreements and confusion in the midst of the event. In other cases, public figures (e.g., Corazon Aquino, Rosalynn Carter) required coordination with the Secret Service (USSS) and/or department of state security (DSS).

The State department played a big role in Prince Charles’s visit to the Broadway Department Stores’ flagship store and worked closely and coordinated with that store’s security staff as well as the Los Angeles Police Department. The rules of the game included that the store was responsible for such in-store functional considerations as control over which elevators would and could operate and/or be used by the prince while inside the store. There was concern an elevator might stop and open on a floor that could compromise security. Such kinds of “proprietary knowledge” makes the private sector an invaluable partner with governmental agents as well as the celebrity’s own protection staff.

Additionally, security plans had to be coordinated with the stores’ publicity and merchandising departments. Security had to be not only effective, but also as invisible as possible so as not to detract from the visual/promotional aspects of the event. While all these challenges were interesting, they also consumed lots of time with the knowledge that any untoward event would receive national publicity and damage to the company’s reputation. Fortunately, my associates were both imaginative and practical in their planning and implementation of the security aspects of these events.

Let me cite just two examples of how celebrity events were dealt with from the security point of view.

Elizabeth Taylor appeared at Macy’s San Francisco promoting her “White Diamonds” fragrance. This event was overseen by Ms. Taylor’s publicist and the store’s public relations and special events departments; security aspects were determined by consultations between Ms. Taylor’s own security detail and the store’s security department. Based on Ms. Taylor’s request, all mail received at the store for her prior to the event and gifts for her during the event were given to store security and examined prior to delivery to Ms. Taylor. At all times during the public appearance, an ambulance (with paramedic crew) was available at the closet exit to the event. Credentials were issued to the press, store nonsecurity personnel, and security personnel. These credentials were color-coded to facilitate the wearer gaining or being denied access to specific areas.

Without my detailing all the specific security precautions, suffice it to say every contingency was planned for, and all security personnel had specific assignments should an untoward event occur. Every aspect of Ms. Taylor’s visit—from the arrival of her plane at the airport, her arrival at the store, the event itself, until she reboarded the plane at the conclusion of her visit—was preplanned. This planning included a suitable place for her to relax in the store, backup vehicles, radio communications, hotel security, travel routes, decoy limo, and prescreening of those receiving credentials. All planning was reduced to writing: floor plans for the event venue showing the location of stanchions, travel routes, press areas, holding areas, and security guard locations. A minute-by-minute time table was prepared to assure a smooth-running event.

In previsit correspondence from Ms. Taylor’s publicist, the following was noted: “Security control is the most important consideration for Miss Taylor’s personal appearance in your store.”

While the bulk of the security was performed by the store’s security staff (with added personnel from nearby stores), it was prudent to contract with a local guard service to provide approximately 30 uniformed (blazers) personnel, who were stationed at exits and throughout the crowd area. Each of these contracted personnel was prescreened and issued very precise post orders as to exact duties and responsibilities. The aspect of crowd control cannot be overstated: Always allow for more crowd control officers than you think will be needed. It’s better to be safe than have an untoward incident.

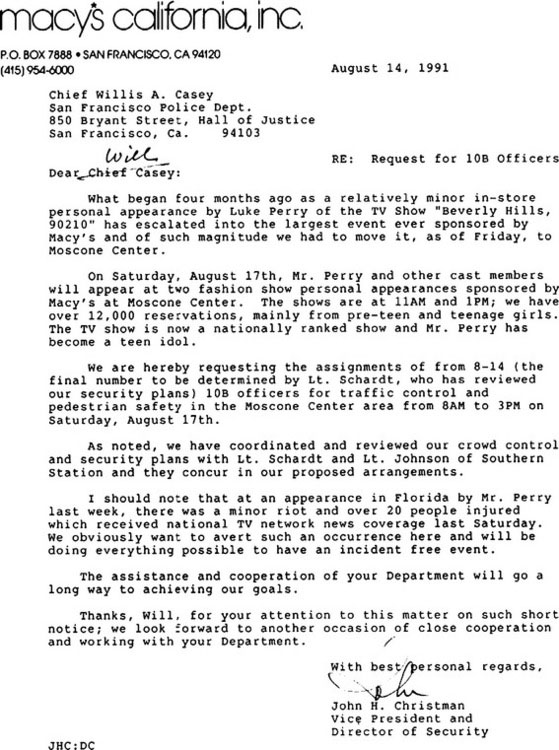

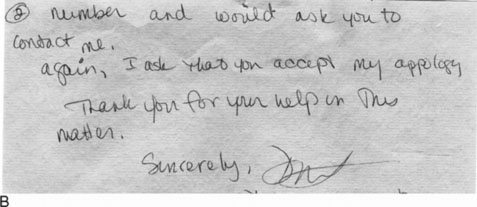

The second event I’d like to describe was the personal appearance of Luke Perry of the TV show Beverly Hills 90210. Figure C-02 shows the letter to the San Francisco Chief of Police that sets the stage for the extensive security arrangements for this event. As background for the letter, you should be aware that over 106,000 phone calls requesting tickets for this event were received; the volume of calls in a 2½ hour period actually “blew up” the switchboard and disrupted phone calls to the store until the switchboard could be replaced.

Security planning for this event was extensive. As the San Francisco Examiner reported: “Moscone Center hasn’t seen such security measures since the 1984 Democratic National Convention.”

The letter resulted in the use of 18 officers from the SFPD being assigned and paid for by Macy’s. (Note that 10B officers are those assigned by the police department but paid for by private [other than city] funds.) It also produced a four-page memorandum from the commanding officer of the detail with assignments, equipment required, and instructions for executing appropriate police action (e.g., arrests) if necessary.

For the event (two shows of about 1 hour each) itself within Moscone Center, we hired 120 uniformed security personnel from area security providers with experience dealing with large crowds (such as at the San Francisco 49ers football games). We assigned 30 of our own security personnel to the event.

Again, we had to plan for decoy units, communications, issuance of post orders, crowd control, barricades for the stage area, travel routes, medical emergencies, portable restroom facilities, security jackets, bullhorns, observation areas, fire lanes and zones, and credentials for personnel authorized in backstage areas.

The security budget for this event was $36,600, not including the cost of our own personnel.

Lessons Learned

Special events and celebrity appearances present challenging security problems, but the application of basic techniques and procedures, adjusted to meet the peculiar circumstances involved, with some imagination thrown in, will provide solutions.

What are some of the more important considerations in planning for a special event or celebrity appearance? We suggest the following:

Pre-planning: Who knows all the event details?

• Can drawings of the venue be obtained?

• Always overestimate number of security personnel needed.

• Establish an emergency evacuation route.

• Plan on how to detain/confine drunks and disorderlies.

• How will security personnel be fed if needed?

• Consult with and obtain OK from fire marshall.

• Will it be necessary to screen for weapons/explosives

• Need for undercover personnel in crowd?

• Arrange for adequate communications.

• Solidify transportation requirements.

• What communications are needed, frequencies, etc.?

• Adequate relaxation and hold areas for celebrity?

• How to deal with inebriated celebrities? (This does happen.)

The venue: public area or within private property?

• Can access be readily controlled?

• Is admittance by ticket or first-come first-in basis?

The celebrity: well-liked or controversial person?

• Does the celebrity have any input into security needs?

• Can the celebrity veto security plans?

• Are any governmental agencies involved?

• Does the celebrity have any of his or her own security personnel?

• Must valuables (merchandise, furs, fine jewelry) be left overnight?

• Black tie? Arrange for proper attire for security.

• How to authenticate legitimate attendees?

• Will food be served? If so, hors d’oeuvres or sitdown dinner?

Post event: Review event and conduct after-action review for lessons learned.

Celebrity and other “Sensitive” Arrest

There’s an inherent risk that a retailer may find himself or herself with a celebrity in custody for shoplifting. We define a “celebrity” as a person who is a public official, athlete, film personality, musician, or other type of figure with high public visibility. The question is: Now what to do? Should a celebrity be treated any differently than Jane or John Q. Public?

Celebrities may either attempt to hide their identity or use it to overpower employees with their importance and influence.

As soon as it is discovered that a celebrity has been apprehended, it is important to minimize the confusion which will naturally occur and to secure the area and the suspect to prevent any loss of evidence. Senior loss prevention and store management must be promptly informed of the situation for their information and counsel. If the celebrity has not at this point relinquished the item(s) stolen, he or she should now be requested to do so. Be sure that this surrender of merchandise is done in the presence of a witness. At this point, company policy for dealing with celebrities should be followed.

What should that policy be? That is a decision only senior management of the company can make. Management must realize that if an arrest is made, it will become a matter of public record and, most likely, extensive publicity, as best exemplified by Winona Ryder’s arrest in 2001, which is a classic and showcase example of the public interest and frenzy over this kind of incident. You can count on publicity if a celebrity is booked for shoplifting. The other side of the coin is why should a celebrity be treated differently than any other shoplifter? Written policy on how to deal with these rare events will dictate the course of action to be followed. And that action must be consistent to avoid subsequent claims of discrimination.

The range of options reflected in the policy could include, but is not limited to the following:

• If the celebrity offers to pay for the merchandise, after receiving an admission of guilt and release, accept payment by having the sale rung up on the selling floor in the normal manner.

• Decline the celebrity’s offer to pay, recover the goods, and obtain a written admission of guilt and release.

• Process the celebrity just as any other citizen who has been taken into custody for shoplifting and exercise one of the three normal dispositions; i.e., call the police, arrange for a conditional release, or release.

The other question which often arises is how to deal with law enforcement officers, senior public officials, and members of the celebrity’s immediate family. Local customs and the political realities must be taken into account. We suggest that if LEOs are apprehended, the head of the department be contacted and his or her advice followed. If spouses or children of LEOs are apprehended, contact the LEO and advise him or her of the situation and asked for a recommendation.

In the final analysis, however, the owner or senior management of the store must make the final decisions, and such decisions should be reflected in written policy.

Chase/Chasing Policy

Every retailer who has a policy authorizing employees to engage in the legal “merchant’s privilege” of detaining suspected shoplifters must have a clear written policy specifically addressing the issue of chasing or pursuing those who refuse to cooperate or otherwise attempt to escape. Injuries drive civil lawsuits, and the two most common causes of injuries evolve around (a) use of force and (b) pursuits. Indeed, out of concern over these two integral aspects of a detention process, some retailers have adopted policies which prohibit the use of force and “no touch no chase,” which we view as a virtual oxymoron. It simply makes no sense to charge employees with catching shoplifters but to deny them the necessary tools to do the job. This issue is addressed more fully in the No ‘Touch’ “Policy” section of this book.

Suffice it to say the majority of detentions for shoplifting are made with the understanding that legal, nondeadly force may be used, and if a person pushes or attempts to strike a loss prevention agent or otherwise bolts to escape, a reasonable and measured effort will be made to take that fleeing thief into custody. We subscribe to this strategy.

The chase/pursuit policy then must spell out what is “reasonable” and what is a “measured effort,” and that policy, because of the nature and dynamics of the process, must include aspects of the use of force.

The drafting or redrafting of the policy should include the following:

1. Agents charged with the task of detaining customers must undergo structured and professional training in how to approach a person about to be detained so as to minimize the risk of violence and effort to escape. Agents who have not been so trained or “certified” to make detentions should be prohibited from making detentions under any circumstances.

2. Ideally, no touching of the customer will be made while escorting the subject back into the store.

3. Minimal touching, such as guiding the subject with one hand on the subject’s upper arm or elbow, is the next level up from no physical contact.

4. Should the subject stop and simply refuse to move or continue, the agent should be authorized to use just that amount of force to overcome the resistance.

5. Should the subject bolt, the agent must make an immediate on-the-spot determination whether a pursuit can safely be made without running into or striking some innocent bystander.

6. If, at the outset of the escape, the subject drops the merchandise, policy must dictate if such action precludes further involvement, i.e., a pursuit, or not. If further pursuit is permitted, it must be kept in mind that any subsequent injuries to the suspect, a bystander, or the agent, the store will have a more difficult time defending a lawsuit, since the merchandise has been recovered and the store has now suffered no loss.

7. No running inside the store.

8. No running in a crowded mall or shopping center.

9. No running in a parking lot if the lot is crowded with pedestrian customers.

10. No pursuit across streets. We note that deaths from shoplifting suspects running into the street and being hit by cars occurs with regrettable frequency. Both of the authors have consulted in such cases and can attest to the utter heartbreak such incidents produce for all concerned parties.

11. Pursuit should not extend beyond the boundaries of the store’s property or shopping center limits.

12. If the fleeing subject is seized and goes to the ground, only holding force may be used until assistance arrives, i.e., no striking, kicking, punching, or choking.

13. No “piling on” a prone subject to avoid possible asphyxiation.

14. Handcuffs should quickly be applied and the subject helped to his or her feet and escorted back to the store.

The policy is necessary for several reasons:

• The agent must understand what his or her company expects in terms of performance and has taken reasonable steps to prepare that agent for this important responsibility.

• The safety and welfare of the general public are important to the company.

• The safety and welfare of the agent are important to the company.

• The safety and welfare of the shoplifting suspect are important.

In the event of civil litigation, the policies in place and the actions taken by the agents in making the apprehension must be demonstrably reasonable under the totality of the circumstances.

Check Fraud

Historically, suspects of check fraud have focused on stealing blank checks, mailed by banks, from unsuspecting customers’ unlocked mailboxes. This once-popular type of check fraud is making a comeback, aided by the fact that most bank customers do not include any preprinted information on their checks, such as Social Security numbers, addresses, or phone numbers. This type of information is added at the point of sale, verified by the merchant who is relying on the fraudulent identification manufactured by the criminals. This bogus identification often includes drivers’ licenses or state-issued identification cards that, with today’s technology, can be easily created.

The thieves continue to cash checks until one is rejected for insufficient funds—that is, if a clerk actually contacts the bank to verify funds. The culprits simply say they don’t know why the check was rejected, “I have plenty of money in the bank; I’ll get the cash and come back later to pay for it.” They never do. The thief just moves on to the next victim.

Although retailers have become more advanced in antifraud techniques, so have the criminals. Most check scams today involve a more detailed execution. Today’s fraud has evolved along with the technology, often using colored copiers, high-tech scanners, and over-the-counter solvents. Some of these new fraud techniques are described next.

Check Washing

Using a process known as “check washing,” suspects erase the ink on checks using chemicals that can be found on the shelves of a local supermarket:

It is estimated that check washing accounts for over $815 million of fraud losses every year in the United States.

Here’s the way the scam works: A suspect removes checks that are often left in an unattended mailbox that the consumer has used to pay personal bills. The suspect then washes the ink from the check, leaving the original signature, but altering the payee and the dollar amount. The suspect often cashes the check at supermarket chains, small gas stations, check cashing outlets, and credit unions using a fraudulent identification.

Despite the fact that check manufactures have tried to prevent check washing and fraud by making checks difficult to wash or copy, many suspects have become so good at check washing that retailers and consumers are unaware until they are given notice from the bank that they were victims.

As a consumer, you can protect yourself by not leaving your mail unattended, using a postal drop box when possible, and using a “gel” pen when writing a check.

As a retailer, you can look for the security features that check manufacturers have used when ordering company checks. Security features may include the following:

• Watermarks: Watermarks are made by applying different degrees of pressure during the manufacturing process. Watermarks are subtle and can be seen when a check is held up to the light. This feature is helpful when detecting a counterfeit check because most copiers and scanners that are used to make the counterfeit checks cannot accurately copy the watermark feature.

• Security inks: Security inks react with common chemicals that are often used to wash checks, making the check unusable.

• Chemical voids: The paper used to make checks is treated with a chemical that is not detectable until mixed with a solvent used to wash the check, producing the word “void” across the check.

• High-resolution micro printing: This is small printing that cannot be seen with the naked eye and is most often used in the signature line of the check. When magnified, the series of words becomes visible; if altered, the series of words becomes illegible.

• Gel-based pens: When writing a check, consumers should use a gel-based pen. Most gel-based pens have been found extremely difficult to wash from the original check. Ballpoint pens and markers are produced with dye-based ink that is easily washed with the average household product.

• Holostripe: Similar to the hologram on a credit card, this feature is inserted into the check and is difficult to duplicate using a color copier or scanner.

Counterfeit Checks

Retailers often fall victim to counterfeit checks and again are not aware the check was counterfeit until they are given notice by their financial institution. Due to the advancement in color copying and desktop publishing, this is also become a fast-growing scam.

Suspects often get their check printing material at a local office supply store where the check writing paper is readily available. (Most over-the-counter paper does not contain the security features mentioned previously.) The suspect then uses an active checking account number and makes several blank checks using a color copier or scanner that is located at his or her home or local printing warehouse. The suspect is then able to use the home-made checks at any retailer that accepts checks. The suspect will frequently write the check for an amount over the purchase price to obtain cash as well as the merchandise.

Suspects also make up checks which appear to be payroll checks from known companies, since major supermarket chains cash payroll checks.

Many retailers combat the check fraud issue by, for a fee, using outside companies that guarantee their checks if the retailer follows certain steps when accepting a check. The benefit of using an outside company is that it guarantees the checks will be paid, regardless whether they are subsequently found to be a fraud. The outside company compares the check data against its database to determine if the company should accept the check from the consumer.

The retailer’s responsibility is to download the program, train its employees to take accurate information, and leave the rest to the outside company. Most large retailers are not equipped to investigate and attempt to collect bad checks. By using an outside agency that guarantees the check, that agency then becomes responsible for investigating, collecting, and perhaps prosecuting the perpetrator.

Citizen’s Arrest (Private Person’s Arrest)

Citizen’s arrest is a concept that dates back to English Common Law. Prior to the development of modern police agencies, responsibility for law enforcement rested with the members of the community. When a crime occurred, every citizen had the right and the responsibility to arrest the criminal and deliver him or her to the local sheriff or other authority.

With the establishment of organized police departments, the need for individual citizens to make arrests has diminished. Still, the right of private citizens to make arrests remains.

Where and When Permitted

Black’s Law Dictionary defines an arrest as “The apprehending or detaining of a person in order to be forthcoming to answer an alleged or suspected crime.”(1) Ex parte Sherwood, (29 Tex. App. 334, 15 S.W. 812).

Usually, arrests are made by police officers acting as agents of the government. The law gives these officers broad authority and a high degree of immunity while carrying out their duties. There are, however, times when ordinary citizens are confronted by criminal activity and no police officer is available to intervene. Because of this possibility, the laws of every state define certain circumstances under which private citizens are authorized to arrest or detain another person.

Some states permit arrest for a wide range of crimes. Others place strict limits on the type of offenses subject to citizen arrest and on the conditions under which the arrest can be made.

The exact circumstance under which an arrest is authorized varies with each state. Some authorize private citizens to make arrests for felony crimes committed in their presence. Others also allow for the arrest of felons even when the crime was not committed in the presence of the arresting person, as long as there is reasonable cause to believe that the person arrested committed the crime. Many states also permit private citizens to make arrests for other less serious public offenses committed in their presence.

A sampling of citizen’s arrest laws shows the following:

• In California: A private person may arrest another:

• In New York State: Arrest without a warrant; by any person:

• In North Carolina: G.S. 15A-404 Detention of offenders by private persons.

In most cases the person making a citizen’s arrest must actually witness the crime. However, many states have enacted so-called Merchant Privilege Statutes. These laws expand the authority of merchants to detain persons for shoplifting and certain other crimes based on a reasonable belief that a crime occurred.

Who Can Make an Arrest?

Although usually referred to as a “citizen’s arrest,” a more accurate description is “private person arrest.” In most jurisdictions where these arrests are permitted, the language of the law extends the authority to any “private person.” This may include noncitizens and even those in the country illegally.

Liability

Under the laws of most states, police officers acting lawfully in their official capacity enjoy considerable immunity from lawsuits arising from their actions during arrests. The same is generally not true for private citizens. Performing a citizen’s arrest exposes the arresting party to both civil liability and criminal penalties if their actions are later found to be in error or in violation of the law. Where they apply, “Merchant Privilege” laws often provide for limited immunity from civil liability if there is reasonable cause to believe that a crime was committed and the arrest was made in a legal manner.

Before someone makes a citizen’s arrest, it is important to fully understand what the law permits in the state where the arrest is to be made.

Civil Disturbances

September 11, 2001, placed a whole new perspective to “civil disturbances”; it now includes terrorism attacks. Since the nature and extent of any such attacks, civil or terror, cannot be predicted and may take a variety of forms, we limit or discussion to some general precautions.

Do’s and Don’ts

• All executives and loss prevention/security personnel have keys to lock doors as necessary.

• All executives and loss prevention/security personnel are in possession of the following telephone numbers:

• Assure trash is removed from the dumpsters on a daily basis, if possible.

• Assure that only “necessary” terminals are opened once threat of civil disturbance is known.

• Both store manager and operations manager should carry one of the security radios at the first sign of any disturbance, if possible.

• Make sure your store command center telephone is staffed at all times by security, senior management, or some other responsible individual at the first sign of any disturbance, if available.

• Have a portable radio available so that local news broadcasts can me monitored.

• Assign a team of store volunteers that would include members from security, stock, dock, etc., to be available to board up windows with premeasured and cut ¾-inch plywood sheets. Assure an ample supply of nails, hammers, gloves, and eye protection is available to handle this task safely.

• Predetermine whether the store will be evacuated upon reasonable belief that it may be in the immediate area of any riot or civil disturbance. This determination should also factor in whether any personnel will remain, to protect the store and its contents, after the general evacuation order is given. If some personnel are to remain, assure they have adequate means to communicate with designated senior management and whether any other special equipment, in the use of which they have been trained, will be issued.

• Determine, in advance, what the pay policy will be for evacuated employees for the period(s) of time off normal work schedules due to an evacuation of the store and/or inability to obtain transportation to work.

• In the extreme event that your store is over run with demonstrators while customers and employees are still present, establish a safe haven such as your office, dock, etc., to shelter these individuals until order is restored. As soon as possible, notify mall security, law enforcement, and regional command for assistance.

• If you are ordered to evacuate the building, obtain the name of the person and the agency he or she represents for insurance purposes.

• Assure all flashlights are in good working order; keep a spare set of batteries.

• Conduct an emergency generator test (if applicable) and assure there is an adequate supply of fuel available.

• Determine, in advance, whether to leave the lights on or off if the store is totally evacuated.

• Do not chain or lock fire doors or emergency exits for any reason while employees and customers are in the building.

• Do not allow firearms on the property, unless armed contract guards have been hired (or previously trained armed proprietary personnel) will be on premises to protect company assets.

• Do not attempt to engage in physical altercations with any demonstrators who may enter or attempt to enter the store, unless those on the property have been given specific directions to the contrary detailing the amount and type of force they are permitted to use.

• Do not disobey the orders of any police or government official, i.e., National Guard.

• Stores should not directly communicate with other stores; this will only tie up the phone lines. All communication outward from stores should be restricted to their regional command center or local emergency services.

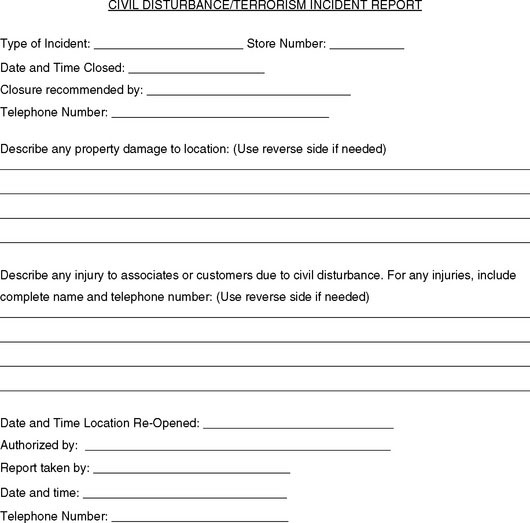

Figures C-3 and C-4 are forms which may prove beneficial.

Civil Recovery

Background

Since the early 1970s states have been passing civil legislation designed to penalize anyone who removes merchandise offered for sale from a store or distribution center without payment. Each state law varies with regard to the penalty amount, damages, and if there is a criminal matter pending.

These laws have proven themselves to be very effective in helping to reduce shrinkage by generating resources for retail loss prevention departments as well as providing a financial deterrent. This income stream helps defray the costs of preventing theft to those who incur it or, in the case of a minor, to the parents.

The language of a few of these laws seems to indicate their intent is to be an alternative to criminal prosecution. Most of the civil recovery laws are not used as an alternative but rather as a consequence to a criminal act. Each of these crimes has a victim. The victims in these cases are retailers, but mainly their good customers who in the past have paid in the form of higher prices.

These laws are currently being used by retailers as an add-on to their loss prevention toolbox. These tools, when added to the entire picture, complement controls and procedures to help bring down shrink.

Generally, theft is a crime of opportunity, and nobody has more of that than employees. Those who are terminated for theft are liable civilly in all states. The major difference between internal and external cases has to do with the condition of the merchandise. Customers are usually caught “red-handed” still in possession of stolen merchandise, which is returned to the retailer once the matter has been dispositioned, either in-house or by the courts. In most employee situations, the case is often built from investigation of past theft, and merchandise is often unrecov-ered. In this situation the retail value of the loss is added to the penalty. The maximum amount is determined by the small claims maximum in the state where the incident occurred.

For best results, case work should contain a narrative, but the crucial element is the theft admission statement signed by the former employee. This process allows the person to pay back the losses incurred through restitution as well as a portion of the investigative cost involved through the civil penalty.

Recovered expense dollars bring 100% to the bottom line, income previously unattainable, and losses which had been previously written off are now being regenerated.

Procedure

Each case must be reviewed by someone who has been properly trained in the area of case review. The condition of the recovered merchandise should be noted, specifically if it was recovered in unsaleable condition or unrecovered. A complete narrative should exist, keeping in compliance with shopkeeper’s privilege and private person’s arrest procedures. Responsible parent information on minor cases should also indicate to whom the child was released. In all cases, the subject disposition should be indicated. The preceding conditions, together with state law, will determine whether a demand should be issued and for which amount.

A series of letters is then sent to the individual demanding payment, which is either preset by the law or based on loss prevention costs. This process is known as “civil demand.” It is an attempt to resolve a financial matter prior to a court action. Once the matter moves to civil court, copies of the demand letters are provided as proof of an attempt to settle this between the parties.

Since there has been no judgment made prior to the civil demand process, care must be taken to limit exposure to liability when engaging a nonadjudicated individual by making outbound calls. In other words, this situation should not be treated as a debt-collection exercise. Once an arrangement has been made between the parties, calls to the individuals are best cast as follow-up to those arrangements.

Recommendations

Upon release of the individual, a notice should be given. The notice should contain language which indicates the state law, the incident, the fact that the store may seek a penalty, and a phone number to call with any questions. Store personnel should not try to explain the notice. They should refer all calls to the recovery agency or suggest the person seek legal counseling.

Store personnel should separate themselves from the collection process. Penalties assessed should be done after the entire case has been reviewed.

A central point for collections and case review should be established so payments, calls, and correspondence can be controlled. A company attorney should be designated to handle inquiries and research.

It is wise to find out what limitations are contained in the individual state statutes. For instance, there are a few states in which a civil demand cannot be issued if there is a criminal matter pending. Understanding the specific criteria to be met on a state-by-state basis is essential.

Effectiveness

The most effective use of civil recovery laws comes in the way of dealing with recidivism. Especially among minors, although most states hold parents responsible, a good way of handling minor cases is by helping parents to exercise control. By allowing the son or daughter to make payments, the consequence for his or her action is realized. Also, this process will not alienate the parents, who are, many times, good customers.

Our internal studies show a rate of recidivism of less than 1% in cases in which the people paid the civil demand. More importantly, in a case study of a major retailer, the overall shrinkage was significantly reduced upon the introduction of a civil demand program.

Outsourcing Collection Services

When a decision is made to create a partnership with a firm to handle any portion of civil collections, several factors should be considered. The first element in this choice should be the services offered by the firm. Many firms today will offer to collect civil recoveries as a return on the services offered by their firm, such as investigation, sale data analysis, and interview costs. Others are law firms, which will add attorney fees to the amount collected and at some point will be retaining more funds than the retailer. Still other firms have the best interest of the industry in mind. They will bring experience in law, loss prevention, and retail. They make the connection between software manufacturers, loss prevention departments, and collection attorneys.

When doing diligence on potential partners, ask for references and also include a request for names of clients lost and why. These requests should also be included in any request for proposal (RFP). Also, some firms will advertise, showing the names of retailers which are only servicing a portion of the cases. Investigate the ownership of the firm, the length of time in the industry, and the amount of litigation encountered along the way.

Currently, there are a few companies active in this arena. My apologies if I have left out any:

Civil Restitution

Civil restitution is a remedy that operates by state statute and is available to the injured party in addition to sums due by way of other restitution remedies.

One of the many challenges retail loss prevention professionals have faced over the years is balancing their efforts to reduce shrinkage against the organization’s need to reduce costs. Civil restitution initially came about as a bright idea to balance the expenses of store detective payroll by passing those costs along to the people who caused the expenditures in the first place—the shoplifters.

Some History of Civil Restitution

In the early 1970s, the state of Nevada enacted a statute involving the theft of library books and civil remedies available to the victims of these thefts. Later, 10 Western states enacted similar statutes, but specific to the act of shoplifting. At the forefront of this legislation was Ron Clark, then Loss Prevention Director of Payless Drugs in Oregon. Ron recognized the opportunities such legislation offered to loss prevention departments and their retail organizations. It was definitely a useful tool to “manage” shoplifting expenses by passing such costs along to those who caused the losses. Additionally, many loss prevention professionals observed that criminal prosecution of shoplifters was being sidelined by reduced budgets in law enforcement, prosecutors, and what appeared to be an apathetic attitude by some jurisdictions.

In the early 1980s, more and more companies jumped on the bandwagon, after initial court challenges were overturned and the path smoothed by the early pioneers. Many members of ASIS International (then the American Society for Industrial Security) Retail Loss Prevention Council proselytized these laws nationally, and we saw additional states enacting such legislation.

Additionally, many states amended their laws to include parents of juvenile shoplifters.

However, these statutes did vary in language and recovery amounts. This occurred because they were enacted by legislators who had to be sensitive to the individual needs, concerns, and the laws of their various jurisdictions.

Most professionals regarded civil restitution as a business tool, rather than punishment.

To Utilize Civil Restitution or Not

Whether a company decides to process civil restitution paperwork internally or opts to use one of the many qualified outside services, several decisions should be considered prior to the adoption of such a program.

First and foremost, upper management must buy into the process. To facilitate this, educate them on the laws appropriate in the area in which you do business and what remedies you have under these laws. Besides running a cost-benefit analysis of using such remedies, it would behoove the loss prevention professional to cover such issues as possible loss of business from irate parents who have received demand letters for their miscreant children’s illegal acts.

If upper management is adverse to such exposure, one alternative is to send demand letters only to adult shoplifters.

Either way, though, you need to make a decision on just to whom you will send demand letters. Will it be all shoplifters? Just those you prosecute? Just those you convict? Just those shoplifters stealing more than a specific dollar amount? Once you have made these decisions, you are ready to proceed further.

Once you have the buy-in and decided to whom you will send these demand letters, you need to decide what amount you should demand. Working closely with your attorneys and financial staff, develop what your average cost of handling a shoplifter may entail and document this information.

Costs relevant to shoplifting prevention in your stores may include such items as electronic article surveillance (EAS) systems, electronic and mechanical shoplift prevention devices (such as cables and the like), and labor costs of plainclothes or uniformed shoplift prevention/detention personnel.

Also, in some jurisdictions, you are allowed to ask for a civil penalty and add on the actual cost of the item stolen. In these jurisdictions, the more the shoplifter steals, the more he or she will have to pay for civil restitution!

Prosecute Versus Catch and Release and the Issue of Extortion

Some jurisdictions require you to prosecute the individuals before requesting a demand amount. Most do not. You have the option of catching the shoplifter and releasing him or her, and still making a civil demand for your costs.

Upon review with upper management and your legal department, it will become obvious what tack your company wishes to pursue regarding the issue of prosecution. Every company must make this decision based on what it feel is best for the company, in each individual state’s jurisdiction.

Additionally, the issue of catch and release may cause some concern regarding juvenile shoplifters. Most companies will require either law enforcement contact or, in the case of release, parental/guardian response to the location prior to release of a juvenile. Again, this is a matter for each individual company to address.

It is recommended that you never present the demand for civil restitution at the time of detention. Any monies gathered at that time could be the basis for allegations of extortion from hungry attorneys who are always on the prowl for a lawsuit against “deep pocket” companies.

However, it is advisable that you give the shoplifter some written document or oral statement backed up in the report that will inform him or her of the possibility of civil demands to be made at a later date. This avoids “surprises” when your demand letter arrives.

Who Decides Who Gets the Demand?

Deciding who gets the demand is an option many companies have agonized about. Many will train their line shoplift detention personnel as to the company’s guidelines on sending a civil demand and leave it up to the agent to recommend or not recommend the issuance of such a letter. This approach seems to work best that way, as the person most knowledgeable of the case, with all the facts in hand and with good education of the company’s civil demand letter guideline template in hand, calls the shots.

Whoever makes this decision, however, must be cognizant of the company’s policy or guideline on the parameters of what qualifies a situation for a civil demand letter and must approve the release of such a letter. This would apply whether the letters are created in-house or outside the company.

Setting Up Your Demand and Collection System

If you decide to create demand letters in-house, you will need to staff up. Consider that you will have to develop a system that will identify which shoplift detentions will merit a demand letter, send a letter on these detentions, track collection or nonpayment, and take further action.

Depending on your jurisdiction and laws, you may wish to pursue nonpayers in civil court. If you decide to follow this course of action, you certainly must first make a decision as to whether it is cost effective to do so. As with decisions to send letters, it is important to be consistent in the application of your decisions. All of this will require time, labor, and systems.

Should you decide to use an outside agency to send your demand letters, your major chore will be to select which detentions merit a demand letter and forward that information to your outside civil restitution agency. In most cases, these agencies will require either a set rate per letter or a percentage of the monies collected. They will follow up on nonpayers, and, in many cases, will function like a collection agency in this matter, sending several letters and even, possibly, making telephone contact with the nonpayers to elicit a payment of the monies due.

It is up to you to determine which will be the most cost-effective method for your company.

In any event, it is always wise to ensure that you are consistent in to whom you send demand letters, and to adhere to your program. This may avoid some legal problems in the future.

Once It Is Up and Running, What Other Issues May Arise?

One major issue is to set up a mechanism that will raise a red flag if a shoplifter is prosecuted and found not guilty. In those cases, it may be advisable to rescind your demand letter. However, you may wish to consult with your company attorney for his or her advice.

Also, it is always advisable to regularly review your cost-benefit analysis regarding costs per shoplifter and, if necessary, change your demand amounts to reflect this cost.

Don’t forget to ensure your upper management, who supported your program, receives regular reports on the income generated from your civil restitution program.

In some cases, loss prevention departments will credit part of the costs, or all, back to the retail location which incurred the expenses. Or, it is used to reduce the costs of the loss prevention department. Either way, the company’s bottom line is enhanced, and everyone likes that!

Collusion

Collusion is best defined as a secretive agreement between two or more people to commit an illegal or deceitful act. In the retail setting, collusion could be an agreement between

• Two or more “customers” to shoplift (as one example),

• A customer and an employee to transact a bogus or otherwise dishonest sales transaction (as a second example), or

• An executive, buyer, or purchasing agent and a second party to bill and pay for goods or services not delivered (as a third example).

We reference “examples” here because the wide range of types of “collusion” is worthy of and is the stuff mystery and crime books are written about. Suffice it then to focus on three examples which should set the stage of understanding for the loss prevention practitioner and/or manager’s role in dealing with collusion.

Collusion Between Two Customers to Successfully Shoplift

Customer A attracts some attention to himself in the selection of a relatively small but expensive item of merchandise and “palms” it in his hand. He walks away from the display still carrying the item. Loss prevention takes up the pursuit, following discreetly in anticipation of his leaving the store with the goods in his hand, unpaid for. As this Customer A turns the corner heading toward the door, Customer B, in a group of other customers, passes Customer A. Customer B is carrying a shopping bag. As the two pass, Customer A surreptitiously drops the merchandise into the shopping bag. Both, without acknowledging each other, proceed in different directions. Customer A is stopped outside the store by LP, and he has no merchandise in his possession. Customer B exits by another door with the stolen goods in her shopping bag, unbeknownst to Loss Prevention. The stage is now set for a “false arrest” lawsuit.

Another scenario could be that Customer A intentionally creates a distraction in the middle of the store causing customers and employees to draw toward that area, while a colleague (Customer B) in the corner hides merchandise and subsequently carries it out of the store.

Collusion Between a Customer and an Employee to Commit Theft

Customer A is the roommate of Employee A. Customer A fills her shopping cart with various items of merchandise and enters the checkout lane leading to the checkout cashier, Employee A. Employee A intentionally fails to record the prices of various items. The total sale may reflect the correct price of 20 items of merchandise, but 9 items of merchandise were never rung up or paid for, as intended in this collusive plan.

A second example: Customer B is Employee D’s sister-in-law. Customer B brings into the store a store bag and a receipt for $60 worth of merchandise charged to her account, but no merchandise. Employee D writes a fraudulent charge credit for the amount reflected on the charge receipt, which amounts to a theft of $60. The prior agreement between B and D to this scheme for committing this theft is also the crime of collusion.

Collusion Between a Second Party and an Executive, Buyer, or Purchasing Agent for Payment of Goods, Supplies, Materials, or Services Not Received and/or Rendered

The chief engineer of the warehouse and distribution center receives an invoice from a “painting contractor” for painting jobs around the facility. In reality, the painter painted the engineer’s mountain cabin and prepared the invoice reflecting work completed on company property, which was never done. The chief engineer approves the invoice and the painter is paid.

The buyer for hardware makes a deal with the stepladder supplier to inflate the invoice by $6 for each ladder purchased by the retailer, with the agreement they will subsequently split the $6 difference between the correct price and the inflated price paid by the company.

The store manager approves an in-store purchase of Christmas decorations, and the invoice is prepared by his brother-in-law. No decorations were received. His brother-in-law isn’t in the business of selling decorations. This arrangement represents collusion between the two to cheat the store and illegitimately receive money to which they were not entitled.

Two actual collusion cases are reviewed in the “Fraudulent Outsourcing and Invoicing” section in this book.

In the retail environment, there are endless possibilities for collusion between employees themselves, employees and customers, and between employees and vendors. The possibilities are limited only by imagination and creativeness. This potential for losses, which can easily reach into the thousands of dollars, is but one, albeit an important one, of the reasons for instituting a system of checks and balances and frequent audits, including the vetting of vendors, particularly those of the small independent contractor variety.

Company Property