S

Security and Emergency Communications

Perhaps nothing is as important to a security/LP department than the ability of staff to communicate among themselves. This is particularly true because portions of LP’s responsibilities involve actions which may be adversarial and confrontational, as well as involve emergencies, and the ability to contact assistance or relay time-sensitive information is essential. For these reasons, a quick, reliable, and secure method of communication is vital.

Years ago, when security staff (or even earlier, when it was known as the “Protection Department”) were needed on the selling floor, the “bell” system was used to page them. The procedure was as follows: The person needing LP called the store telephone operator and verbally requested LP in a given area of the store. The telephone operator would then cause chime-like “bells” to sound throughout the store. When LP staff heard their designated bell call, they would call the store operator, who would direct them to the area where their services were required. This bell system was also used to contact store managers and other executives, each of which had a distinctive bell call, which was generally a series of sounds in groups of five or fewer bells. For example, LP may have been assigned 5-1 bells, sounding in several distinct series of xxxxx x, xxxxx x, xxxxx x.

In the 1970s, most LP departments converted to portable radios for in-store communications. These battery-operated radios permitted LP agents to be called by the store telephone operator and/or by any other portable radio on the same frequency. Thus, not only were LP agents able to be paged to a given area of the store, but they could also communicate among themselves. “Privacy” channels (frequencies) enabled them to restrict some communications to specific radios so that “outsiders” like telephone operators could not hear their conversations. Each portable radio had at least two rechargeable batteries so that while one was in use, the other could be charging. Most LP agents choose to use the standard “Ten Code” for their transmissions because it saves time and is easily understood.

Later on, security/LP executives who traveled between stores were issued pagers so that they could be contacted at any time their pager was turned on, which by tradition was almost every waking hour (and when emergency conditions existed, any waking or nonwaking hour). Larger stores eventually installed systems whereby a sales associate or other store personnel could call LP agents over their radios simply by dialing a special number on the store phone system.

The advent of so-called trunked radio systems permitted the use of relay towers scattered throughout the state to permit long-distance radio communication with radios of relatively low power. By utilizing additional equipment, retailers were also able to broadcast through this system from telephones by dialing the correct connection code.

Whatever radio system is selected, it is important to provide for powering it and recharging its batteries from both 110VAC power as well as 12VDC power. In emergencies, local power often goes out, and if radios can be powered/recharged only by 110VAC (house current), their life will be limited to available battery life. If, however, there is a converter or other means of plugging into and powering/recharging from 12VDC (automobile cigarette lighter sockets), then the radio can realistically be used as long as there is a vehicle available.

The latest communication devices utilized by security personnel are cell phones and cell phones capable of “walkie-talkie” operation. These phones can almost communicate instantaneously and privately from one coast to the other.

Modern communications prove indispensable during major emergencies. We can attest to the fact that, during the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, the security radio system, which enabled long-distance communications, proved a godsend. Because both local landline and cellular phone systems, as well as local power, were interrupted, the security department’s radios, with their ability to be powered by vehicle batteries, were the only method of communication available between affected stores.

Security Mirrors

The use of convex mirrors as a security tool is perhaps one of the oldest such tools still in use today. Convex mirrors are utilized to permit viewing specific areas of the store or aisles from a distant location without, one hopes, disclosing the fact that such viewing is occurring. In most situations, however, anyone who is knowledgeable about the use of convex mirrors can easily determine if he is under observation. For this reason, these mirrors present a double-edged sword for the store owner: Not only can the owner see a potential shoplifter, but the potential thief can also see that he is under observation.

It has been our experience that while such mirrors are not particularly useful as operational antishoplifting devices, their existence in a store does send the message to potential thieves that the store has at least some degree of security awareness and in this way may serve as a deterrent to shoplifting.

Another mirror used in retailing is the so-called two-way mirror, which allows representatives of the store, i.e., management or a loss prevention professional, to view the selling floor from such areas as stockrooms or a “Trojan horse,” while the opposite or public side of that mirror appears to be no more or less than an actual functional mirror.

A cautionary word about two-way mirrors: During the long history of retail security and loss prevention, there have been instances in which these devices were used in areas with high expectations for privacy, such as fitting rooms and restrooms. Those days have long passed, and two-way mirrors should never be used in those areas today. In most jurisdictions, such use is actually illegal.

Security Surveys

Introduction to Security Surveys: A University Bookstore Security Survey

While the trend appears to be for colleges and universities to outsource the operation of their bookstores to companies such as Barnes & Noble, many schools still continue to operate their campus stores. Some universities have ancillary services whose operations fall under the bookstore management. Examples of such ancillary services are Technical Books (e.g., Medical, Legal), Fax and Sales Services, Office Products, Computer Repair Facilities, Vending Operations, Copy Centers, Laundromats, Retail Operations (Clothing, Gifts, and Insignia merchandise), and Food Vending Services. The loss prevention aspects of a college bookstore are generally much like those of any other retail operation, with some aspects which are unique to the college campus environment. We feel the best way to present both a broad picture of the loss prevention aspects of college/university bookstores as well as provide an introduction to security surveys is to reproduce an actual security/loss prevention survey done at a major university (whose name and personnel identities have been disguised). By reviewing the survey, you will gather not only the LP concerns of this venue, but also the format, scope, and details of an actual security survey, which can be adapted and applied to any venue.

CONFIDENTIAL SECURITY SURVEY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Copy 1 of 5 CONSULTANT’S REPORT

SECURITY SURVEY FOR THE UNIVERSAL STORE

SCOPE

This report is the documentation of my survey of the existing security/loss prevention policies, procedures, organization and operations at The Universal Store [hereinafter referred to as THE STORE] and its ancillary stores and Warehouse as authorized by Mr. Thomas Martin, CEO and Director. The objective of the survey was to assess existing physical and functional security and to recommend changes or improvements where appropriate to ensure

a. That efforts to provide a safe working and shopping environment are adequate and reasonable, and that appropriate emergency plans are in place.

b. That security policies, procedures, and operations comply with all applicable laws and are legally justifiable.

c. That appropriate checks and balances exist to both deter and detect internal dishonesty.

d. That adequate programs are in place to minimize losses from shoplifting and customer fraud, and to effectively and reasonably deal with offenders.

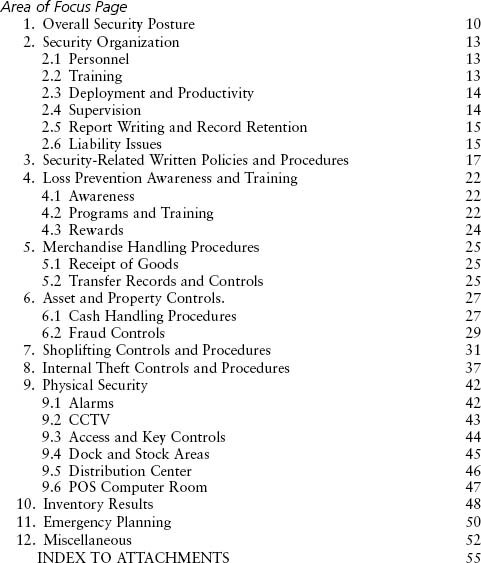

The survey identified twelve (12) Areas of Focus, which are

3. Security-Related Written Policies and Procedures

4. Loss Prevention Awareness and Training

5. Merchandise Handling Procedures

6. Asset and Property Controls

7. Shoplifting Controls and Procedures

The 12 areas are not necessarily distinctly separate one from the other, but each does tend to blend with and/or augment another so the totality of the security strategies achieves the desired effect. For ease in presentation and comprehension, they are hereinafter referred to as Areas of Focus, some of which may have subareas. Under each Area of Focus is a listing of Findings, most of which are immediately followed by a Recommendation. Recommendations are consecutively numbered by Area of Focus for ease in referencing. The Areas of Focus are preceded by an Executive Summary.

METHODOLOGY

The Findings in this report resulted from my inspections of the facilities concerned; personal interviews with THE STORE employees; and review of documents, records, and statistics relating to security operations and personnel, inventory shortage, organizational policy, procedures and structure, receipt and distribution of merchandise, and control of cash. We have purposely not included in this report maps, organization charts, statistical summaries, etc., obtained from and readily available to bookstore management unless such documents are integral to this report.

While every recommendation contained herein is a practical enhancement of existing security, some are optional in nature and not absolutely essential to meet the objectives of the Survey; they are presented to provide the reader with a range of solutions and options available.

In all cases the optimal recommendation, in my opinion, is presented first, followed, in some cases, by less than optimal but still useful alternatives which may be temporarily utilized.

It must also be noted that my Survey was conducted shortly after the end of Fall Rush and while THE STORE was still in the process of “getting back to normal.” Admittedly, some deficiencies noted herein may well automatically be corrected when THE STORE returns to “normal” operations; however, loss prevention vulnerabilities are the greatest during Rush, so in this sense this survey may actually be more meaningful than if conducted in mid-semester.

Finally, we recognize that there may be inherent conflict between the establishment of some appropriate security procedures for a retail business of the size and type of THE STORE and the requirements, real or perceived, of operating on the campus of a prestigious and world-renowned research university in the somewhat cloistered environment of academia. In these instances, management must be the final arbiter.

The cooperation and assistance of the following persons who were interviewed is noted:

• Mr. Rich Jones, Vice President, Universal University

• Mr. T, Martin, CSP, Director

• Ms. S. Xxxxxxx, Operations General Manager

• Ms. D. Xxxxxx, Human Relations Manager

• Mr. J. Xxxxxx, Warehouse and MIS Manager

• Mr. K. Xxxxxx, Head, Computer Sales and Technology

• Mr. B. Xxxxxx, Security and Retail Supervisor

• Mr. S. Xxxxxx, Buyer—All Text and Trade books

• Mr. B. Xxxxx, Print Shop Manager

• Ms. R. Xxxxxxxxx, Warehouse Supervisor

• Ms. D. Xxxxxxxxxxxxx, Account Representative

• Ms. D. Xxxxxxx, Head Cashier, Sales Audit and Payroll Clerk

• Mr. S. Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx, Retail Manager (Clothing and Memorabilia)

• Mr. P. Xxxxxxxxx, Retail Manager (Supplies, Electronics, and Gifts)

• Ms. M. Xxxxx, Esq., Judicial Administrator, Universal University

• Mr. G. Xxxxxx, Business Solutions, Program Consulting Manager

• Mr. R. Xxxxxxx, Investigator, Universal Police Department (Crime Prevention

• Mr. G. Xxxxxxxx, Investigator, Universal Police Department (Crime Prevention)

Special Thanks to Jane Sxxxxx, Secretary to the Director, for her courtesies and help.

Executive Summary

Universal University is situated in Middleton, New York, a city with a population of approximately 30,000 people. The Universal community, during the school year, consists of 20,000 students and 10,000 faculty and staff.

THE STORE, with $30+ million of annual sales, operates under the overall supervision of Mr. Rich Jones, who, before being appointed a University Vice President several years ago, was THE STORE CEO and Director for many years. While part of the University system, THE STORE is financially self-supporting and pays 5% of its gross sales (with some minor exceptions) as a “royalty” to the University. It is housed in a two- story facility located near the center of the University campus. Its design is unique; University esthetics’ requirements [preserving a view] preclude any design changes to the building. This prohibition effectively precludes any expansion, both outward and upward, which is desperately needed.

THE STORE comprises 43,000 square feet of primarily selling space with minimal nonselling support and office space. THE STORE is open 5 days [closed Sundays] for 50 hours a week. THE STORE also operates three remote retail locations: a very small outlet at the Veterinary School, a small outlet in the Xxxxx Hotel lobby, and a brand new retail section added to the Best Copy Center. Additionally, THE STORE operates a Print Shop and a 12,000 square foot Warehouse, which houses the Universal Business Center [Travel Service, Sales Audit, and Accounting Departments] in a 3,800 square foot second floor area. In all, THE STORE has 72 career and from 10–60 part-time student employees and, as needed, from 5 to 65 temporary agency personnel.

The store is open Monday through Friday from 8:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. and Saturdays from noon until 5:00 p.m.; a total of 50 hours per week.

The existing security and loss prevention policies, procedures, organization, and operations are inadequate to meet the stated shortage objectives of management.

The security organization is essentially nonexistent. Mr. Ben Johnson, a Retail Manager, was tasked early this year with the responsibility for security/loss prevention. To his credit, Mr. Johnson, with no background in loss prevention, began to acquire some of the fundamental precepts of loss prevention, primarily by using the Web and reading a security magazine. While these efforts are laudatory, this approach is doomed to failure, particularly when his retail operations responsibilities have not diminished and demand his full-time attention. Mr. Johnson’s status as a nonmember of senior management coupled with his lack of any formal security/loss prevention training assures not only a mediocre loss prevention effort at best, but a real danger of inadvertently creating civil liability resulting from well-intentioned but legally erroneous procedures.

Shoplifting detection and apprehension had been accomplished by a part-time employee who monitored THE STORE’s closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras. This person is no longer employed and his employment violated New York state law; he has not been replaced. Consequently, the sole shoplifting detection relies on sales associate’s response to alarms of the electronic article surveillance (EAS) system at the store exits, a procedure which currently is essentially ineffective.

There is no Security/Loss Prevention Operations Manual. Mr. Johnson, again to his credit, has written a document titled “Security and Operations: Responsibility and Policy Manual.” Unfortunately, as a result of Mr. Johnson’s lack of training, this document contains numerous procedural and legal errors, which places THE STORE in legal jeopardy. Additionally, this document is totally silent on retail loss prevention techniques, fraud prevention, and internal theft.

Most employees felt THE STORE was “wide open” to shoplifting; nearly all suggested that THE STORE’s CCTVs should be monitored and that backpacks/book bags not be allowed in the store. Merchandise handling and distribution procedures seem adequate, but there are no procedures in place to either deter or evidence theft.

Some buyers felt that the computerized inventory control system had glitches resulting in reporting nonexistent missing inventory and exaggerating shrinkage. An examination of THE STORE’s back office equipment [laptops, printers, copiers, etc.] disclosed that many had no serialized property tags affixed. It is doubtful that an exact inventory of THE STORE’s equipment exists or that losses could, if noticed, be substantiated. Shoplifting controls need improvement; the antishoplifting closed-circuit television (CCTV) system, while in the process of being upgraded, remains below par. The EAS system needs maintenance; portals operate erratically, alarms are not loud enough, and the red alarm lights do not all work. It appeared that even tagged items could pass through the system undetected. Cashiers at registers cannot adequately respond to alarms when they do occur. Successful shoplifting creates the opportunity for fraudulent returns, primarily of textbooks, and there is no procedure currently in place to detect this activity.

Internal theft is a subject which apparently has received little attention. There have been few employees apprehended for stealing and, at least one that was, was reportedly allowed to continue working. Suspicions of internal theft are not referred to Mr. Johnson but rather “investigated” by the Operations Manager. CCTV surveillance of cash register checkout areas is lacking. This is an area which requires a significant increase in emphasis, the adoption of techniques to identify and surface any problems, and the acquisition of personnel trained to investigate and resolve these issues.

Physical security requires considerable attention. Physical protection of reserve stock merchandise and offices containing merchandise all create loss vulnerabilities. The continued upgrading of CCTV will improve both internal and external theft detection and provide management with a valuable tool for improved customer service and staffing evaluation. The fire sprinkler head in the ceiling of the POS computer room should be capped off; an accidental or intentional discharge of the water sprinkler would ruin the computers and put those systems out of business until replacement equipment could be installed. The door to this space should be locked when the room is unoccupied; backup tapes should be stored in a fireproof container. Alarm systems, while adequate, contain capabilities which are being underutilized. Management, therefore, does not gain the advantage of available, but unused, features providing additional safeguards and controls. Testing of alarm systems is not done; there is no exception reporting. Key controls and issuance and deletion of access control codes require written documentation; all keys should be stamped “Do Not Duplicate.” Employee package checks are rarely performed, and there have never been any real-time janitor surveillances or checks, even though they are in the store after hours and have keys and alarm codes.

Inventory figures reflect generally increasing shortages over the past several years. In FY 02 [excluding computer sales and shrink], textbooks and educational supplies represented approximately 90% of the shrinkage dollars while responsible for only 55% of sales. It is the consensus that the bulk of these losses occur during Fall and Spring Rush, where space needs and limitations result in the virtual inability to deter and detect shoplifting. Textbook shortages at nearly 6% is triple the industry average.

Dock security in THE STORE is unacceptable and offers opportunities for increased security and minimizing potential loss situations. The lack of security controls and disciplines on the dock present serious vulnerabilities; there is often unrestricted access to the dock, mechanical equipment room, and employee-only areas. The location and accessibility of the employee badges to nonemployees should be eliminated. The University has a comprehensive Emergency Preparedness Plan, and the Universal Business Services (THE STORE) plan has been integrated into it. It was indicated the Emergency Plan is available on campus computer terminals; this policy should be reviewed as to whether having the plan universally available (without password) on terminals for legitimate reference outweighs its general availability to a potential miscreant, particularly since the printed document is marked Confidential.

University Police resources, such as their crime prevention officers, are underutilized.

Housekeeping and neatness in general needs significant improvement.

The entire issue of security, loss prevention, and the protection of assets appears, until recently, to have been largely ignored. Efforts to establish better controls for protecting assets must be undertaken. Interestingly, no employees suggested that the community at Universal is, unlike the general population, not subject to human frailties and temptations, which include acts of dishonesty. It is, therefore, management’s responsibility to insist that procedures be in place and that they be followed to adequately protect the assets of THE STORE.

It is noted that existing policies, procedures, controls and disciplines within the various areas of focus not mentioned herein have been found to be adequate to meet currently recognized minimum security standards and practices.

The recommendations and suggestions contained in this report should help position THE STORE’s management in addressing the security needs of this vital facility to assure that THE STORE can continue not only to meet its mission. but to do so at increased profitability.

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

| AREA OF FOCUS #1 | |

| Overall Security Posture | |

| FINDING: | It is the consensus of those interviewed and the observation of this consultant that security at THE STORE is less than adequate. This situation is a matter of concern to nearly every employee interviewed, but most seemed unwilling or unable to grant the solutions and disciplines required for correction a high priority. This inaction appears to stem from two basic factors: (1) lack of time and other pressing priorities, and (2) the absence of the expertise required to develop and implement loss prevention training, procedures and programs |

| RECOMMENDATION 1.1: | Loss prevention training, programs, and awareness must become an integral part of THE STORE environment. This will require the employment of a security/loss prevention professional whose basic duties and responsibilities are limited to his area of expertise. |

| FINDING: | Responses to written questionnaires and personal interviews make it apparent that there are numerous misconceptions and misunderstandings regarding some of the University’s and THE STORE’s policies, procedures, and operating standards with respect to security issues among store management. |

| RECOMMENDATION 1.2: | Management must assure that security standards, after adoption by senior management, are adequately promulgated, understood, and followed by all employees. |

| FINDING: | Senior merchants and department managers must be an integral part of the process toward shortage reduction, and should be intimately aware of the shortage percentages and dollars down to the classification level. Any lack of knowledge about shortage detail does not permit managers to design and then implement the necessary shortage reduction strategies specific to merchandise classifications. |

| RECOMMENDATION 1.3: | Each department manager should be given all available data regarding his department’s shortage. After each inventory, this data should be discussed with the appropriate senior member of management, and shortage reduction strategies and goals for the coming inventory period should be agreed upon in writing. Periodic follow-up should be made to assure implementation of agreed-upon action. |

| FINDING: | The entire thrust of THE STORE’s security program is the apprehension of shoplifters. |

| The broad concept of loss prevention is totally absent. Basic loss prevention activities as employee security orientations, return/refund analysis, inventory shortage review, merchandise movement control, developing minimum security standards for merchandise presentation, audits of security-sensitive areas, employee package checks, and the development and implementation of security/loss prevention policies and procedures are either completely lacking or barely adequate. | |

| RECOMMENDATION 1.4: | The thrust of THE STORE’s shortage control and security activities must be prevention. It is essential the program be redesigned to make prevention of loss a priority with apprehension by security considered a necessary activity only after the prevention efforts fail or are ignored. This effort should (a) start at the top and permeate through all employee levels, (b) establish defined shortage reduction goals, and (c) require that managers and supervisors be held accountable for results. A culture of discipline and controls must be established. While designated security personnel will play a key role in prevention efforts, all employees must be involved for the effort to succeed. |

| FINDING: | THE STORE has assigned the security function as one of the responsibilities of a Retail Manager, which is not a senior management level position. This organizational position of the security/loss prevention function, coupled with the Retail Manager’s lack of any formal security training, has, perhaps inadvertently, relegated the perception of the importance of security to a rather subordinate and unimportant role. |

| RECOMMENDATION 1.5: | THE STORE should recruit and hire an experienced professional security manager who will function at a senior management level. The proper candidate can assume responsibility for new employee security/safety training covering external theft, internal theft, and fraud; supervise and train the security staff; assist in inventory preparation; conduct audits; establish a meaningful shortage control and loss prevention program which functions throughout the year; and be a fully contributing member of senior management. |

| FINDING: | There is no Loss Prevention Manual. |

| RECOMMENDATION 1.6: | A comprehensive compilation of all policies and procedures designed for loss prevention and shortage control should be prepared as “the Bible” for security/loss prevention personnel as well as guidance to store management. |

| FINDING: | THE STORE currently has no one dedicated to the loss prevention function. |

| RECOMMENDATION 1.7: | A qualified Security Manager [see Recommendation 1.5 supra] will possess advanced investigative skills and can effectively train, schedule, and supervise subordinates to monitor CCTVs and assist in other security/loss prevention activities. The goal of a close working relationship between security agents and other store personnel is essential to effective loss prevention and shortage control. |

| FINDING: | THE STORE does not have in place procedures which both deter and provide for early detection of internal dishonesty |

| RECOMMENDATION 1.8: | That procedures and techniques, such as register “salting,” introduced errors, extraction programs in the distribution system, and random surprise audits and inspections be implemented. |

| FINDING: | THE STORE has no in-house capability to properly and successfully detect and investigate any but the most obvious, basic, and straightforward indicia of employee dishonesty or fraud. |

| RECOMMENDATION 1.9: | This finding further mandates the hiring of a security professional. |

| AREA OF FOCUS #2 | |

| Security Organization | |

| FINDING: | THE STORE has essentially no security/loss prevention personnel. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.1: | Recruit and hire a security professional and adequate subordinate personnel. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.2: | Loss prevention personnel below the Manager should be referred to as Security Agents or Loss Prevention Agents. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.3: | Devote at least 106 hours a week to dedicated nonstudent loss prevention personnel; typically a 40-hour Manager and 66 hours of Agent’s time. |

Note: The importance of implementing RECOMMENDATIONS 1.5, 1.7, 2.1 and 2.2 will become evident as the balance of the findings under this and Area of Focus #4 are studied.

2.2 Training

Note: This section will be also referenced in Section 2.7, “Liability Issues.”

| FINDING: | The lack of a professional security manager subjects THE STORE to civil liability as well as potential criminal liability. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.4: | THE STORE must employ a security professional. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.5: | A written test should be required to establish comprehension of the training materials given security personnel, and follow-up training should be required at least yearly to update them regarding any new legal issues, shoplifting techniques, etc. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.6: | A security professional should be responsible for training security personnel who will be making detentions/apprehensions. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.7: | Anyone hired to monitor CCTVs should also be fully trained to make detentions and perform essentially other loss prevention functions, such as audits, loss analysis, surveillances etc. |

2.3 Deployment and Productivity

| FINDING: | There are no dedicated loss prevention personnel. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.8: | By utilizing properly trained full-time security agents, performing under the supervision of a qualified security manager, their role could be proactive with all the concomitant benefits deriving therefrom. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.9: | Security personnel should be scheduled 15 minutes before store opening and until all personnel have left THE STORE at closing. |

2.4 Supervision

| FINDING: | Mr. Johnson is supervised by the Operations Manager, who is questionable with respect to his loss prevention duties. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.10: | When a security professional is hired, they should report to the Store Director. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.11: | Agent personnel should report only to the Security Manager. |

2.5 Report Writing and Record Retention

| FINDING: | At present, THE STORE’s apprehension reports are prepared on Mr. Johnson’s computer terminal. There should be a written report of all detentions, not just apprehensions. It is the detention where no stolen merchandise is found which are the troublesome ones. These must be documented and given thorough review to minimize this liability exposure and to determine if retraining is needed. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.12: | Detention reports should be reviewed periodically by someone in the University legal office to assure compliance with all codes and statutes. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.13: | Mr. Johnson’s computer should require a password to access Apprehension Reports; this information should not be available to unauthorized persons. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.14: | A copy of the security access password should be placed in a sealed envelope and kept in a secure location for use in emergencies. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.15: | Arrest report information should be retained for seven (7) years and then destroyed. |

2.6 Liability Issues

| FINDING: | Existing Security Policies contain inaccuracies. (See FINDING and RECOMMENDATION 2.5 supra.) |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.16: | A security professional should prepare the |

| Security Manual; it should be reviewed by University legal counsel. | |

| FINDING: | Christopher Extra, who monitored THE STORE’s CCTV [no longer employed or replaced] violated New York General Business Law Article 7-A [Security Guard Act] § 89-e et seq. by not having the required training and registration required by this act. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.17: | Conduct all security activities in compliance with state law. A security professional would have known of this law and prevented its violation by THE STORE. |

| FINDING: | As noted in several sections above, various of my findings point out potential liability exposure for THE STORE/University. These exposures are inherent in the activities of any security department, but by careful and proper selection of personnel, coupled with adequate training and supervision, these risks can be minimized. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.18: | The entire security function, when its structure is ultimately determined, should be reviewed with the University’s legal counsel. |

| FINDING: | Mr. Johnson does not have a lockable office or a locked file cabinet. |

| RECOMMENDATION 2.19: | Mr. Johnson [or any subsequent Security Manager] requires an office which is private and a file cabinet which locks. This protects THE STORE from civil suits for invasion of privacy or defamation. |

| For example: If the Security Manager interviews an employee about any issue in an area which is not private, others observing this conversation may draw erroneous conclusions as to the reasons for the interview. | |

| Further, sensitive documents, which may be on his desk, are less open to compromise. | |

| Similarly, arrest reports, investigative reports, and other security information must be securely stored to prevent unauthorized access. |

| Area of Focus #3 | |

| Security-Related Written Policies and Procedures | |

| FINDING: | The use of the current “Security and Operations: Responsibility and Policy Manual” prepared by Mr. Johnson contains various errors, omissions, and inappropriate instructions. |

| For example: Under the section “Job Description” A and B state the security employee is responsible for “the maintenance of daily store activities,” including such things as “Store errands, clearing rooms, washing vans and doing odd jobs.” If loss prevention is to be effective, its personnel cannot also be janitors. There is no mention that, if a suspect is female, the industry standard is always have a female witness present. | |

| The policy states there is a duty to apprehend customers when they conceal merchandise and leave the sales floor without purchasing it. This statement should provide that the employee must know that the concealed merchandise belongs to THE STORE and was not previously purchased. | |

| The policy provides for an apprehension when another employee states he witnessed a shop-lift and is willing to provide a written statement. The industry rule is “If you didn’t see it, it didn’t happen.” Additionally, New York Criminal Procedure Law § 140.30 provides that for a misdemeanor arrest (under $1000) the crime must be committed in the presence of the arresting person. There is no mention in the Policy of the Industry standard of meeting the “six steps” prior to an apprehension. SEE ATTACHMENT I. | |

| RECOMMENDATION 3.1: | That use of the current Security Manual be discontinued immediately until it is revised to meet acceptable standards. |

| RECOMMENDATION 3.2: | That all training materials utilized in training store security personnel be thoroughly examined for content and approved by University legal counsel. |

| FINDING: |

There is no document such as “WELCOME TO THE STORE” which contains the work rules, policies, and procedures expected to be followed by employees. A draft document, intended for student employees, titled “Policy Manual,” which covers some work rules, dress code, use of time clock, breaks, absenteeism, name badges, and other similar topics, awaits final publication approval. This draft document has, in my view, several deficiencies, namely: (2) There is no mention of the consequences of violating the rules against ringing up your own sale or making your own change.

|

| RECOMMENDATION 3.3: | |

| RECOMMENDATION 3.4: |

Develop a written set of Rules and Regulations governing employee behavior. State with specificity that any act of theft or fraud against THE STORE will result in immediate dismissal and possible criminal prosecution. (This is covered in the University’s “Policy Notebook for Universal Community” given to all students.) However, it does not reach temporary agency personnel employed by THE STORE). A thorough review of all employee rules and regulations is suggested, since employer liability for employee actions is expanding as a result of statutory law and court decisions. Employee rules must be both comprehensive and clear with regard to the penalty for violations. With regard to register procedures, specific rules regarding: |

| FINDING: | I found no specific regulations covering Buyers. |

| RECOMMENDATION 3.5: | |

| FINDING: | I found no document covering “CUSTOMER SERVICE.” |

| RECOMMENDATION 3.6: |

It is well established that the best defense to shoplifting is good customer service. While it is not always possible to service each customer immediately, it is possible to immediately establish eye contact, and by words [“I’ll be right with you”] or body language let the customer know that her presence is known. These actions provide an effective shoplifting deterrent; the sales associate should never wait until approached by the customer to initiate these actions. Establish a rule or statement (and perhaps signs in back office areas) to the effect that employees are expected to: Recognize each customer immediately; Establish eye contact; Smile and be pleasant; Give each customer excellent service. |

| FINDING: | The Emergency Preparedness Plan for Universal Business Services on page 18 refers to the appropriate actions to take in case of criminal activity or bomb threats. While the information contained in these sections is accurate, it is unlikely an employee would have the time to refer to these pages should such an event occur. |

| RECOMMENDATION 3.7: | |

| RECOMMENDATION 3.8: | |

| FINDING: |

The Draft document titled “The Universal Store Employee Policy Handbook” corrects many of the deficiencies noted above in the draft “Policy Manual.” This Handbook document is quite detailed and should be published and distributed to all employees. My comments for suggested changes are minor, but include (a) The statement regarding the keeping of personal belongings at the cash register should be stronger; it should state is prohibited.

(b) The term “immediate family” in the employee purchases section needs definition; what constitutes “immediate family” should be clearly defined. Under the section on Holding of Merchandise, the term “any length of time” should be stated more specifically in terms of hours or days. |

| RECOMMENDATION 3.9: | Make changes suggested in (a) through (f) supra. |

| FINDING: | Neither the draft “Policy Manual” nor the draft “Policy Handbook” makes provision for the employees to certify they have read, understand, and agree to its provisions. |

| RECOMMENDATION 3.10: | Have only one “Policy Manual.” Whatever document is finally approved and issued, it should contain a tear-off portion at the end which contains language similar to: “I certify that I have read the above, fully understand it, and agree to it. I further understand that any violations may result in disciplinary action, up to and including termination without prior warning.” This statement should then be signed by the employee, removed from the main document (which should be retained by the employee), and filed in the employee’s personnel file. |

| RECOMMENDATION 3.11: | Establish a “tickler” system to assure the return and proper filing in the employee’s personnel file of this signed form from every new employee. |

| Area of Focus #5 | |

| Merchandise Handling Procedures | |

| 5.1 Receipt of Goods | |

| FINDING: | Receipt of goods at the warehouse appears to meet required security standards. |

| RECOMMENDATION 5.1: | None. |

| FINDING: | While opinions differ, it is evident that there is less than a tight control over and accounting for individual units of merchandise received from the warehouse by THE STORE. The best evidence indicates store receivings are not matched against transfer manifests. |

| RECOMMENDATION 5.2: | This deficiency should be corrected. |

| FINDING: | There is no physical separation between incoming and outgoing shipments at the warehouse or THE STORE. |

| RECOMMENDATION 5.3: | The physical design of the warehouse dock makes physical separation of receivings from outgoing merchandise extremely difficult. To the extent possible, goods should be staged away from the dock areas as soon as possible to minimize theft potential and inadvertent intermixing. |

| 5.2 Transfer Records and Controls | |

| FINDING: | As noted above, little, if any, attention is paid to manifests relating to shipments from the warehouse to THE STORE. |

| RECOMMENDATION 5.4: | All merchandise received at THE STORE should be checked against receiving documents. |

| FINDING: | There is no “extraction” program in use at the warehouse. An extraction program periodically and surreptitiously either adds or removes goods from shipments [assuming the paperwork cannot be easily manipulated to accomplish the same results]. The objective of these manipulations is to see how accurately the receiving personnel check in manifested merchandise and report discrepancies. |

| RECOMMENDATION 5.5: | Consider an extraction program. |

| FINDING: | The physical handling of warehouse receivings and the documentation and ticketing functions appear to be in order. Some additions to the physical security aspects of the warehouse will be noted under Area of Focus # 9. |

| FINDING: | University trucks (vans) are used to move merchandise from the warehouse to THE STORE, but there is no way to determine if merchandise has been removed between the warehouse and THE STORE. |

| RECOMMENDATION 5.6: | At least during Rush, seal the cages so that, if they are opened before arriving at THE STORE, it will be evident. The extraction program would also be useful in this regard. See Recommendation 5.5 supra. |

| AREA OF FOCUS #8 | |

| Internal Theft Cont rols and Procedures | |

| FINDING: | Employee package checks are rarely, if ever, done. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.1: | Routine but surprise package checks are a proven deterrent to internal theft and should be conducted. THE STORE’s draft policies provide for such checks by “management or operations/security.” We suggest such checks should be done exclusively by management or security; it is not a good practice to have peers doing such inspections. |

| FINDING: | There is no auditing of employee purchases made under the generous employee discount program. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.2: | Employee purchase records should be audited for both the absence of purchasing as well as an extremely heavy volume of purchases; such anomalies should be investigated, since they may indicate either a theft problem or an abuse of the discount program. |

| FINDING: | There exists no honesty shopping program. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.3: | Honesty shoppers should be employed periodically. Such a program not only may provide indications of dishonesty, but also serve to provide an assessment of the level of customer service being given. |

| FINDING: | There have been very few identified dishonest employee cases in the past 3 years. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.4: | Institute those loss prevention/security measures and procedures [recommended throughout this report]. Employ a professional security manager who possesses the knowledge and skills to legally and effectively investigate and resolve internal dishonesty problems. |

| FINDING: | Bonding forms are not used. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.5: | A bonding form should be used for all nonstudent employees. Answers to bonding form questions, executed after employment, provide an easy means of comparison with answers to similar background questions contained on employment applications. The use of a bonding form does not require actual bonding of employees. The form itself has been shown to produce more truthful or accurate answers than those submitted on employment applications. |

| Note: A “bonding form” should contain many of the same basic questions as the employment application, but in a different order. The theory behind this technique is that most persons who lie on an employment application cannot remember the exact nature of their untruths, and thus these will show up as discrepancies. The new employee should be questioned regarding these discrepancies, and if the application was falsified in any material way, it is well established that such falsification is grounds for immediate dismissal. | |

| FINDING: | Senior management and “sensitive” positions within THE STORE should received some type of background investigation by the Universal Police Department, consistent with New York and federal law. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.6: | Consideration should be given to a more thorough vetting of new career personnel and particularly those in cash handling or other sensitive positions. Thought should be given to utilizing additional screening tools for these applicants. The judiciousness of more thorough screening would appear to be more than justified as statutory demands for workplace security increase. |

| Note: Any use of additional pre-employment screening techniques should be cleared with the University Human Relations office and with legal counsel. | |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.7: | Vetting should include

(b) Job offers to applicants can be made under two scenarios: [1] A job offer is not made until favorable background check results are obtained, or [2] the job offer is made contingent on a favorable background check.

(c) For all applicants subject to a background investigation, the University will obtain the necessary releases. [Currently covered with University Employment Application]. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.8: | Anyone driving Bookstore vehicles should be subject to annual DMV checks. |

| FINDING: | No surprise audits are conducted of any of THE STORE’s operations. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.9: | A program of surprise audits of THE STORE, remote facilities, and the warehouse should be scheduled. These audits should not be confrontational or adversarial in nature, but more of a “Hi, how ya doin’?” approach, during which appropriate auditing can be accomplished in a casual but thorough way. |

| FINDING: | THE STORE has no covert CCTV, “Trojan horses” (covert observation areas), or two-way mirrors for investigating either shoplifting or suspected internal theft. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.10: | Adequate equipment and facilities should be acquired to permit appropriate investigations to be conducted effectively. (See comments in § 9.2 below.) |

| FINDING: | There is no reported mention of internal dishonesty as part of new employee indoctrination. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.11: | The security portion of the new employee orientation should include the topic of internal dishonesty. It is suggested this orientation include the video The Best Defense (covering shoplifting) and its companion, Choices (covering employee dishonesty.) The security aspects of the orientation can be made into a positive event by including some information on personal security issues such as buddy systems, personal security awareness, etc. |

| Note: These videos can be obtained by contacting ETC (Excellence in Training Corporation), 11358 Aurora Avenue, Des Moines, IA 50322-7979, 1-800-747-6569. | |

| FINDING: | There is no procedure for the intentional introduction of errors into control systems. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.12: | A procedure for the introduction of errors into control systems is desirable. Such a procedure tests whether such systems are in fact working as designed, and if so, by whom, when, and how the error surfaced. |

| FINDING: | There is no “hard and fast” prohibition against employee purses and packages on the selling floor. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.13: | Implement such a policy and require strict and consistent enforcement. See Recommendation 3.8. |

| FINDING: | Custodial personnel work essentially unsupervised. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.14: | A program of periodic surveillance of custodians is needed. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.15: | Occasional package/equipment checks should be made when janitorial personnel leave THE STORE at night. |

| FINDING: | THE STORE uses common register drawers. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.16: | If registers are ever replaced, individual drawers are always preferable to common drawers. Individual drawers significantly increase personal responsibility for cash accountability. |

| FINDING: | THE STORE has no Reward Program. |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.17: | |

| FINDING: | THE STORE has no “Hot Line.” |

| RECOMMENDATION 8.18: | Consider either a commercially available service which provides a confidential means for employees to telephone information to management or an in-house program which accomplished this objective by a post office box. Investigation should be conducted toward perhaps utilizing the University’s “Silent Witness” program through www.cupolice.Universal.edu/witness. |

| SEE ATTACHMENT V. |

| AREA OF FOCUS #10 | |

| Inventory Results | |

| FINDING: | Shortage over the past few years shows a disturbing upward trend, with the bulk of the shortage in textbooks and writing instruments. |

| FINDING: | Reduction of shrinkage does not seem to be a high-priority item with some merchants and managers. |

| RECOMMENDATION 10.1: | Inventory results should be disseminated and discussed in detail with individual department managers. Departmental shortage reduction goals should be set and progress toward achievement monitored throughout the inventory period. |

| RECOMMENDATION 10.2: | Assure that all merchants and managers fully understand the effect of shortage on THE STORE’s bottom line and their performance reviews. |

| FINDING: | There is concern among merchants that missed markdowns and RTVs have resulted in artificially high shortage. |

| RECOMMENDATION 10.3: | Do what is required to not only assure merchants that all markdowns and RTVs are captured, but also audit to guarantee that they, in fact, are captured. |

| FINDING: | There is a concern among some merchants that the price lookup (PLU) system contains pricing errors. |

| RECOMMENDATION 10.4: | Take necessary actions to assure accuracy of the PLU system, and assure merchants of its accuracy. In reviewing the system, if possible, assure that |

| FINDING: | It was reported that known losses are written off as markdowns. |

| RECOMMENDATION 10.5: | If true, this should be considered when reviewing shrinkage figures. |

| FINDING: | As noted elsewhere in this report, retail merchandise is stored in back office areas, and housekeeping is less than desirable. |

| RECOMMENDATION 10.6: | Assure that all merchandise is counted at inventory. |

| FINDING: | Two managers suggested that the inventory system shows more items on hand than physical counts indicate when merchandise is first received. |

| RECOMMENDATION 10.7: | It is essential that everything be done to ensure that merchants have faith in the accuracy of the inventory control system. |

| FINDING: | It was reported that changes can be made to the inventory control system by merchants without any audit trail as to who made the adjustment or when it was done. |

| RECOMMENDATION 10.8: | If such adjustments are permitted, there should be an audit trail identifying not only who did it, when it was done, but also the justification for doing it. |

| FINDING: | It was reported that outdated merchandise which remains unsold is given to employees. |

| RECOMMENDATION 10.9: | Discontinue this practice; give it to charity. |

| Attachment Number and Name | Cited on Page | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | The “Six Steps” | 17II |

| II. | Robbery Checklist | 20, 51III |

| III. | Bomb Threat Checklist | 20, 51IV |

| IV. | Security Violation Notice | 23V |

| V. | Reward Program | 24, 41VI |

| VI. | Civil Remedy Law—New York | 31VII |

| VII. | Photo—Textbook cages during Rush | 33VIII |

| VIII. | Voluntary Admission Form | 35IX |

| IX. | Detention Report | 35X |

| X. | THE STORE First Floor Plan—CCTV revisions | 43XI |

| XI. | THE STORE Second Floor Plan—CCTV revisions | 43XII |

| XII. | Best Copy Center Pan – Proposed CCTV | 43XIII |

| XIII. | Warehouse Plan—First Floor—CCTV proposal | 44XIV |

| XIV. | Photos—THE STORE Receiving Dock | 45XV |

| XV. | Photos—THE STORE – Back areas | 46XVI |

| XVI. | Photos—Unrestricted back area access from selling floor | 46XVII |

| XVII. | Warehouse (Business Office) Plan – 2nd Floor | 46XVIII |

| XVIII. | THE STORE—POS Computer Room | 47XIX |

| XIX. | THE STORE—Fire Extinguisher | 51XX |

| XX. | Photos—THE STORE—Housekeeping | 52 |

Security Technology and the Retail Industry: A Glimpse into the Future of Loss Prevention

We need not look much further than the latest crime drama on television to see the direction of security technology in the near future. Whether the episode involves DNA evidence from a piece of chewing gum or the analysis of gunshot residue on a suspect’s hand, the primetime network line-up is a perfect place for amateur detectives to learn about the latest advances in investigative technology. Whether or not each of the tests is possible, one category of futuristic technology is very real and has already started to work its way into mainstream society.

This technology is called “biometrics,” or automated methods of identifying an individual using unique physical or behavioral characteristics. The most familiar example of biometrics, fingerprint identification, is used in law enforcement practices to identify a potential suspect. Though the technology has been limited to the government arena since its inception, modern improvements and decreasing prices have resulted in the appearance of biometrics in everyday life. This section looks at biometrics and its potential relevance in the loss prevention industry.

First, an introduction. “Biometrics” is the general term given to the science of utilizing unique human characteristics to identify an individual or verify his identity. Biometrics are categorized into different modalities, or types, depending on the physical characteristic used for the identification process. Biometrics are based on the presumption that as humans, our physical traits (such as our fingerprints) are unique only to us and that they can be analyzed, measured, and compared to another set of physical traits with a reliable level of accuracy. The most popular modalities include fingerprint recognition, iris scan, hand geometry, and our focus later on in this piece, facial recognition. Fingerprint technology has been widely accepted by law enforcement agencies as a reliable tool when identifying a suspect. Many times you will hear your favorite crime scene investigator talk about “running a fingerprint through AFIS,” or Automated Fingerprint Identification System. AFIS is a common methodology of automatically scanning a database of fingerprints in search of a match, or a “hit” as they call it.

Biometric matching is broken down into two general categories: 1-to-1 matching, or “verification,” and 1-to-many matching, or “identification.” In 1-to-1 matching, a single biometric, for instance, your fingerprint, is used to verify your identity. This type of matching requires you to first present a “token,” such as an ID card, pin code, or password, which informs the system that you, or someone claiming to be you, is trying to gain access. The system then waits for you to present your fingerprint to verify “you are who you say you are.”

In today’s security environment, 1-to-1 matching is most often seen in a physical access control system, for instance, as an enhancement over standard electronic entry systems for an office, home, or any other protected space. In these instances, biometrics are used for reasons of superior protection as well as convenience. A simple pin code and biometric combination means that the user will never again have to suffer the frustration of forgetting his keys.

The second type of matching, 1-to-many, uses largely the same hardware and software as 1-to-1 matching though the purpose is quite different. In 1-to-many matching, a single biometric, again a fingerprint, is used to identify an individual against a database of previously enrolled fingerprints. (Note: In the world of biometrics, “enrollment” refers to the actual process of inserting an individual’s biometric template into a database or associating an individual’s biometric with their identity.) This type of matching is most frequently associated with the AFIS matching referenced above: A single fingerprint is used to figure out the identity of a criminal suspect).

Biometrics have been “almost here,” meaning commercially deployable, for quite some time. Few other technologies have been so eagerly anticipated. The reason is simple. Biometrics solve security gaps that have existed since the advent of the modern security era. Now that the price of the technology has decreased to a commercially affordable level, we have finally reached the true launch point for this exciting technology.

An example of a relatively large-scale biometric deployment is a company known as “Pay By Touch.” At the time of this writing, Pay By Touch is one of the most publicized usages of biometrics in the world. Pay By Touch is considered a leader in engineering the biometrics crossover from the government sector into our everyday lives. Pay By Touch utilizes fingerprint verification for secure transactions in a retail environment. An alternative to cash or credit cards, Pay By Touch capitalizes on our society’s growing desire to become more efficient and, for a lack of better term, more “high tech.” Because you need only a unique pin number (likely your home phone number) and your fingerprint, Pay By Touch allows you to leave your cash and cards at home.

Aside from the conveniences offered by such a program, Pay By Touch is also a great example of how biometrics can be used to prevent identity theft. Because your fingerprint must be verified to process the transaction, the risk of credit card fraud is virtually eliminated. As time goes on, we can expect many other companies to leverage the unique benefits of biometrics to achieve a business purpose.(1)

Facial Recognition Technology

Facial recognition technology is one of the most intriguing yet widely used technologies in the field of biometrics, if not security as a whole. Facial recognition technology involves the measuring of facial features to identify an individual or verify his identity. Similar to other biometric modalities, facial recognition algorithms encode a subject’s facial image from a standard headshot photograph into a biometric template, based on the dimensions of his face. The template is then used to match against a specific template (1-to-1 matching) or database of templates (1-to-many matching). One of the main reasons facial recognition technology has received so much attention is the potential of widescale deployment with little or no subject authorization. Unlike most other biometric modalities, facial recognition does not require participation and/or cooperation. In certain environments facial recognition software can be integrated with standard CCTV cameras, which look no different from the cameras in your parking garage, the lobby of your office, or a sports arena.

Perhaps the most widely publicized usage of facial recognition in recent history was the 2001 Super Bowl in Tampa, Florida. The administrators of the program compiled a database of facial images of known criminal suspects. The facial recognition software was incorporated into the surveillance cameras that were fixed on the incoming traffic of Super Bowl goers. Presumably, the facial image of each attendee was matched against the watch list database. The system turned up a handful of accurate matches though many more false matches.

After the tragic events of September 11, 2001, the facial recognition community received a tremendous amount of attention. Was there a possibility that this technology could have identified the hijackers as known terrorists prior to their boarding the planes? While this still remains a question, the need for accurate facial recognition technology was spawned.

The Achilles heel of facial recognition technology, more than any other biometric technology, is the occurrence of false matches. False matches are quite simply the facial recognition software mistaking one person for another. The problem arises, however, when too many false matches result in a “boy who cried wolf” situation.

If you think about it, the concept of false matches is quite familiar to us. Many people look alike. How many times have you thought, “Boy, doesn’t she look like …?” A false match is the software’s way of telling you that it thinks it found someone who looks very much like a particular person. Now, to our human eye, the people may not look anything alike, but to the facial recognition matching algorithm, they are very similar.

The question arises, then, in the balance of false matches to positive matches. How many false matches are you willing to view and dismiss as a trade-off to finding one accurate match of a potentially dangerous person? At what point do you ignore the alerts and disregard the system?

While the government sector will continue to evaluate facial recognition technologies for use in the War on Terror, these same technologies have applications for everyday usage. At the time this piece was written, quite a few companies are beginning to evaluate facial recognition technology in the private sector as a way to combat problems that have plagued them for years. One such application is the retail security market and the fight against shoplifting.

Current loss prevention measures vary from retailer to retailer, from industry to industry. Some of the most common security tactics include electronic article surveillance (EAS) tags, CCTV camera networks, and human security guards. For most shoppers, these measures are enough of a deterrent to steer clear of any temptation. But for experienced thieves, there are always methods of circumventing the system and more sophisticated deterrents are needed to truly make an impact. Enter facial recognition technology.

Many retailers have different procedures when dealing with shoplifters. Certain retailers are interested only in getting the merchandise back. Other retailers prosecute to the fullest extent of the law. Regardless of protocol, the goal is to prevent the shoplifter from ever coming back into the store.

Whether you manage a small retail shop or are a loss prevention professional in a large department store, it is unrealistic to expect your staff to study the facial characteristics of each customer and compare them to a printed list of headshot images. While you would expect them to stop someone in the act, a preemptive measure of this sort is not feasible. In essence, facial recognition technology is handling this job for you.

Because there is no known widescale usage of facial recognition within the retail market at the time of this writing, the following is a theoretical description of usage. A typical facial recognition identification system would include a standard CCTV camera fixed on the incoming flow of human traffic into your store. Each frame captured by the camera would be automatically searched for the presence of any facial images. If any images are found, the images would be converted into a biometric template and matched against a database of previously apprehended shoplifters. If the system finds a match, your staff is notified and, in most cases, given the opportunity to visually compare the match.

How is this database compiled in the first place? The answer to this question depends on the procedures in place for each retailer. In an ideal environment, the shoplifter is apprehended and formally processed. This gives store management the opportunity to capture multiple images of the individual for the enrollment process. If this is not possible, certain facial recognition systems allow you to search through video feeds obtained that day and isolate the facial image of the individual. This is helpful for the scenarios when it is not practical to detain the subject, or, during post-event analysis.

The potential for facial recognition within the retail industry is tremendous. By identifying known shoplifters as they enter the store, management is given the opportunity to trail the person, follow him on camera, or even refuse service. As with any security technology, however, facial recognition deployments must be coupled with human participation to be able to realize the full benefits.

Privacy Concerns

No discussion of facial recognition would be complete without acknowledging the privacy implications of the technology. The word “biometrics” raises eyebrows for many people because there is a growing concern that the move toward a biometrically enabled society will ultimately result in our personal information—financial data, medical history—being connected to our fingerprint, iris pattern, or our facial features. In addition, the increase in surveillance cameras has led people to believe that we are being tracked everywhere we go and that we are one small step from an Orwellian society.

It is important to remember, however, that biometrics are not inherently privacy invasive. As with many other security technologies, the privacy danger lies in the purpose for which they are used and the manner in which they are deployed. For the purpose of tracking citizens from street to street, location to location, facial recognition biometrics poses a serious threat to privacy. For the purposes described previously, namely the identification of shoplifters within a retail environment, the usage of facial recognition is less concerning. But it still does not necessarily mean that customers will be agreeable to their favorite retail store’s usage of facial recognition.

Even though the system is not operated or monitored by some sort of centralized tracking agency, the fear of the technology lies in the fear of the unknown. Are the facial images gathered from the entrance cameras linked with other cameras around the city? Are these images being shared with public agencies to help track citizens?

The best method of addressing these questions is by proactively informing your customers as they walk through the door and offering additional information if necessary. There is no risk in being transparent. Shoplifting affects everyone, and to keep prices competitive, the store must try to reduce shoplifting as much as possible. Facial recognition is simply the means to do this.

Summary

As the search continues for effective loss prevention measures, security technology will maintain its major role in the battle against shoplifting. Facial recognition presents a unique advantage in that it is the only practical method of identifying a potential thief as he walks in the door. By deploying such a system, retail stores of all types and sizes will be armed with preemptive knowledge that has never before been offered.

Regardless of performance enhancements, the major barriers to entry will remain largely political. Fears of a surveillance society are very real. We must remember though that facial recognition technology, when used appropriately, is no different from an enhancement to the CCTV cameras that are already in place. It is not the technology that threatens privacy; it is the usage. An active dialogue between privacy advocates and the biometrics community will be a necessary component of introducing the technology into the retail environment.

Selected Security-Related Organizations

• American Polygraph Association: Organization dedicated to providing a valid and reliable means to verify the truth and establish the highest standards of moral, ethical, and professional conduct in the polygraph field. www.polygraph.org

• American Society for Industrial Security, International (ASIS): The world’s largest security organization, which is dedicated to increasing the effectiveness and productivity of security practices via educational programs and materials. www.asisonline.org

• Association of Certified Fraud Examiners: Organization dedicated to combating fraud and white-collar crime. www.cfenet.com

• Association of Christian Investigators: Organization whose mission is to integrate the private security investigative profession with Christian values. www.a-c-i.org

• Canadian Society for Industrial Security: A professional association for persons engaged in security in Canada. www.csis-scsi.org

• High Technology Crime Investigation Association: Association of high-technology criminal investigators. www.htcia.org

• International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety: Professional security management association. www.iahss.org

• International Association of Auto Theft Investigators: Organization formed to improve communication and coordination among professional auto theft investigators. www.iaati.org

• International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators: Informational website regarding university and college security. www.iaclea.org

• International Association of Personal Protection Agents: Informational site for international bodyguards www.iappa.org

• International Association of Professional Security Consultants: Members are independent, non-product-affiliated consultants pledged to meet client needs with professional consulting services. www.iapsc.org

• International CPTED Association (ICA): Crime prevention through environmental design practitioners. www.cpted.net

• International Foundation for Protection Officers: Training and certification of line protection security officers. www.ifpo.org

• International Process Servers Association: An online resource designed to assist process servers, private investigators, skip tracers, attorneys, and paralegals. www.serveprocess.org

• International Professional Security Association: Organization that promotes security professionalism in the United Kingdom. www.ipsa.org.uk

• International Security Management Association: Organization of senior security executives. www.ismanet.com

• International Society of Crime Prevention Practitioners, Inc.: Crime prevention organization. www.crimeprevent.com

• Investigating Associated Locksmiths of America: Professionals engaged in locksmithing business. www.aloa.org

• Jewelers’ Security Alliance: A nonprofit trade association that has been providing crime prevention information and assistance to the jewelry industry and law enforcement since 1883. www.jewelerssecurity.org

• National Alliance for Safe Schools: Organization promotes safe environments for students. www.safeschools.org

• National Association of Professional Process Servers: A worldwide organization that provides a newsletter as well as conferences and training. www.napps.com

• National Australian Security Providers Association: Australian industry association. www.naspa.com.au

• National Burglar and Fire Alarm Association: Organization that represents the electronic security and life safety industry. www.alarm.org

• National Classification Management Society: Classification management and information security organization. www.classmgmt.com

• National Council of Investigation and Security Services: Organization for the investigation and guard industry. www.nciss.com

• National Fire Protection Association: National Life Safety codes. www.nfpa.org

• National Society of Professional Insurance Investigators: Membership, education, and recognition information. www.nspii.com

• Security Industry Online: Organization that represents manufacturers of security products and services. www.siaonline.org

• Security on Campus, Inc.: Resource for college and university campus crime safety and security issues. www.campussafefy.org

• Society of Competitive Intelligence Professionals: The premier online community for knowledge professionals all around the world. www.scip.org

• Society of Former Special Agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation: Publications and member information. www.socxfbi.org

• South African Security Industry Associations: Directory listing of South African security associations. www.security.co.za

• Spanish Association of Private Detectives: Spanish organization for private investigators and process servers. www.detectives-spain.org/english

• Women Investigators Association: An association geared to the special needs of women investigators. www.w-i-a.org

• World Association of Professional Investigators: New investigation organization in London. www.wapi.com

Selecting and Hiring Loss Prevention Personnel

Having concise policies and procedures is important, but if you don’t select loss prevention people with care, those policies alone won’t protect you. Particularly those who are entrusted with the mission of detecting shoplifting and other crimes, and possibly apprehending those responsible, must be carefully chosen and trained before they are cleared to make apprehensions.

The ideal loss prevention agent is a person of good moral character, excellent communication skills, both verbal and written, and with good judgment. The list of desirable attributes we want this person to possess is lengthy, and who wouldn’t want all employees to live up to these standards? There is no formula for completely ensuring the candidate you select will work out successfully, but by following a consistent, well-conceived process, you greatly increase the odds of developing a good agent. Close evaluation and regular, ongoing training are a must. A candidate who interviews quite well may prove, over a short time, not to possess the acumen, drive, or instincts to detect suspicious activity on the sales floor or in the back rooms. In that case, deal with the issue by providing additional coaching or, if that is not effective, by removing the agent from the position. A probationary period of 3 months or longer is recommended, if consistent with what your HR department and the laws of your state allow.

Recognizing we must recruit from the human race, it may not be possible to recruit a sufficient number of candidates who fully meet your criteria. The liability for selecting the wrong person in a loss prevention agent capacity is so damaging that, only when a candidate meets your high standards should he be hired.

One way to address a shortage of cleared LP agents is to assign the majority of your loss prevention people involved as a visible deterrent. They might be in a uniform or other easily recognized outfit.

They might be called inventory control specialists. These specialists, whether employees or contract workers, deter crime by acknowledging and greeting customers as they enter and exit high theft areas.

They can be trained to “burn out” a suspect by making their presence and observation obvious, but the risks of civil litigation are greatly reduced by not allowing detention or apprehension, unless specifically instructed to assist by a “cleared” loss prevention agent.

Both covert and overt loss prevention staff should receive regular training in the civil and criminal laws pertaining to arrest and detention, as well as store policies and procedures regarding all aspects of behavior that violate either store policy or criminal codes. A good loss prevention agent is assertive but not aggressive. Finding the right person or persons requires careful scrutiny and a clear understanding of the skills and traits desirable for the position.

If you already have a good loss prevention team of professionals, it is worthwhile to have members of the team individually interview the candidate and provide their input on the candidate. Often, they can get a sense of whether the prospect will be a good fit with the team. Ultimately, it is the others on the loss prevention team who must be able to fully rely on observations, judgment, and signals of each cleared agent in making a detention. Such trust comes only from actually working together as a team and through regular training together.

Having a series of interviewers independently asking the same question “So, tell me about yourself” is not that revealing. Instead, give each interviewer a specific objective to explore. For example, one person might concentrate on the person’s temperament. “When was the last time you lost your temper?” “What happened?” “When was the last time you were in a fight?” “What irritates you the most in life?” Another person could ask questions about training and experience, and so forth. Taking the time to delve into each candidate’s background in a well-planned process not only helps you make the right choice, but also sends a loud and clear message to the candidate that this position is important.

Good candidates want to be challenged. This process changes the candidate’s focus from, “Is this position good enough for me?” to “Am I good enough to make the team?” That’s what you want to happen. All too often, even in good companies, the people who first interview candidates appear to be unprepared, short on time, and disorganized, asking shallow or nonrevealing questions, or they spend most of the “interview” talking about themselves instead of learning about the candidate. A good interview establishes a balance between listening and giving information. It should be a casual, two-way conversation, but with a clear objective to reveal as much as possible about the way the candidate thinks and acts.

From the ranks of the uniformed LP specialists, some may demonstrate the kind of alertness, judgment, and skill to be considered for promotion to the LP agent team that is cleared to make detentions when appropriate.