U

Uniform Crime Reporting System

The vast majority of law enforcement agencies across the country contribute their crime statistics to the Federal Bureau of Investigation for use in a national crime statistics database known as the Uniform Crime Report (UCR). For retailers, the UCR helps determine the level of specific crime threats that exist in different cities. More importantly, the UCR provides per capita crime rates for eight crimes known as Part 1 offenses. Part 1 offenses include murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, theft, motor vehicle theft, and arson. Since legal crime definitions vary by state, the UCR uses standardized offense definitions by which law enforcement agencies submit crime data without regard for local and state crime definitions. These uniform definitions allow accurate comparisons across the many jurisdictions in the nation. The eight crimes were selected because they are serious by nature, occur frequently, are likely to be reported to law enforcement, can be confirmed by means of investigation, and occur across all jurisdictions in the country.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s annual publication Crime in the United States is the result of the approximately 17,000 law enforcement agencies that provide their crime data to the UCR program. Crime in the United States supplies retailers with summary crime information for most cities and counties in the country. The book compiles crime volume and crime rate for the nation, each state, and individual agencies along with arrest and clearance information. Ten years’ worth of Crime in the United States books can be downloaded from the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s website, www.fbi.gov. Another source of crime data is the Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics, which provides raw crime data available for download in portable document format (PDF) and in spreadsheet format. The Sourcebook may be accessed via www.albany.edu/sourcebook/. A guide to the use of the Uniform Crime Report data by retail security professionals can be found in the chapter titled “Threat Assessments in the Retail Environment.”

While the Uniform Crime Report system has been in use since the late 1920s, the need for an even more robust national crime reporting system has increased in recent years. This need has prompted the development of the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS). While the new program is not yet fully operational, the National Incident-Based Reporting System will eventually provide a wealth of information to law enforcement agencies, policy makers, researchers, students, and security professionals. According to the FBI, “Although participation grows steadily, data is still not pervasive enough to make broad generalizations about crime in the United States.”

The National Incident-Based Reporting System collects data on each incident and arrest within 22 offense categories made up of 46 specific crimes called “Group A offenses.” For each incident known to police within these categories, law enforcement collects administrative, offense, victim, property, offender, and arrestee information. In addition to the Group A offenses, there are 11 “Group B offenses” for which only arrest data are collected. The goal of NIBRS is to make better use of the detailed and comprehensive crime data collected and maintained by law enforcement agencies.

Use of Force: A Primer

If you’re going to make policy, it helps to know the language. As a guide, it is good to know the private sector generally adopts the law enforcement model when creating force policy.

That does not mean things are the same in healthcare as they were 20 or 30 years ago. At that time many security directors came directly from the police experience into their position. The resulting “hard-core” enforcement style scared administrators who supported a more benign and socially oriented method. What evolved in many cases, and is still the norm in some locations, is the “Observe and Report” and the “Don’t get involved; you’re not a police officer” response, which let that mentality take over. This idea, coupled with other limitations, low pay, and lack of respect given some officers, had generally bad results. Security was not effective in times of extreme need.

As the security director has become more professional, the need to provide a more effective response became more important. Even the most conservative administrator can be convinced in time to support the need to physically intervene in cases of imminent threat to employees, visitors, or patients. This does not mean throwing the security officer under the knife of the attacker, and this is not meant to be a debate about carrying weapons. What it does mean is to have a policy and training that will support the first responding officer so that the officer knows what his or her options are and that he or she can take control of the situation and limit the damage until the police can arrive on the scene.

The goal here is to provide for an effective security policy that will let the officers carry out their duties in a controlled, supervised, and responsible manner.

There is no national standard for private security use of force. Many local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies have developed and written a use-of-force policy. Many use a matrix or relationship model as a guide for the officers in use-of-force incidents. Paralleling local law enforcement policy can be beneficial, assuming similar or same criteria are used. The difficulty is that many security directors don’t have or see the need in most cases for a SWAT-type unit that routinely engages in high-risk operations. What to do until the SWAT team gets there is more the norm.

That brings us back to “Observe and Report.” The news is replete with violent incidents involving patients, visitors, and employees being accosted, victimized, and in some cases, being the ones doing the assaulting. The question is: Do you want security officers intervening in emergency situations in which a physical assault is imminent or happening? If the answer is “yes,” there should be a written policy for the officer’s response to the subject’s actions. That response is at the heart of the use-of-force policy. What follows may be considered an introduction on how to develop such a policy.

Knowing what you want and what the administration will support is an obvious first concern. You can’t have the vice president calling about the SWAT truck with the hospital logo parked in the back lot unless he or she agreed you need it. Directors do ongoing audits to determine risk, probability of occurrence, and so on. Having the support and budget to implement a basic plan has to be in place before the policy is written.

Things to know beforehand include whether you want the officer getting involved in property crimes. Do you want the officer, assuming he or she has the authority in your state, to detain someone who has just committed an aggravated assault (a felony in most jurisdictions) but who is on his or her way out? If we are shooting for a middle of the road policy here, we might say no to the property crime detention, no to detaining the subject who just committed the aggravated assault, but definitely doing what he can to keep the crime from getting worse. This would include the officer getting involved physically up to and including using force to defend himself or herself or a third party.

Determining whether the officers will carry weapons is something that has to be known upfront. Most supporting organizations recommend leaving that decision to the individual facility. To carry or not and what to carry often depend on location, crime rate, administration philosophy, etc. If weapons, including aerosols and/or batons, are carried, ongoing training and certification must be documented.

Know the legalities of the power of the officer. There is a big difference in the authority of a sworn officer versus a nonsworn officer. Check the applicable state laws and regional court precedents for references to “citizen’s arrest.” I did a Basic Hospital Security class years ago and had an 8-year veteran tell me at the end, “Now I know what I can do.” Imagine the officer wandering and wondering for 8 years unsure of what his authority was. He had been told, “Do what you have to do.” That advice would not have gone over well in court.

Security officers can be an integral part of the administration’s conforming to the OSHA General Duty clause. Since we are going to mimic law enforcement, the Graham v. Conner case is very important. The Supreme Court’s ruling in Graham v. Conner 490 U.S. 386 104 L. Ed. 2d 443, 190 S. Ct. 1865 (1989) established the phrase “objectively reasonable” in the minds of all use-of-force trainers and should be kept in mind when developing policy.

The policy could have a disclaimer stating the administration supports the proper implementation of the policy. The idea of using force as a last resort and the need to communicate and practice effective “customer service” skills should be endorsed. The policy definitely should not have any wording that demands “minimum force” be used prior to the escalation to the next step. There are too many examples of when a higher level of force is justified right away to trap the officer with this policy. The phrase “use only the force that reasonably appears necessary to effectively bring an incident under control …” appears in several highlevel organizational policies and is recommended.

Don’t confuse the policy with training. The policy document should not have all the “how are we going to get there?” information. The policy is an outline, speaking to the overall objective of the institution. It is not a step-by-step process of how the goal is to be accomplished. That being said, the policy has to be specific enough to protect from generalities. “Doing what has to be done” is not what we are looking for. Generating specifics that can be identified and trained to is the goal. Knowing the language is a basic step.

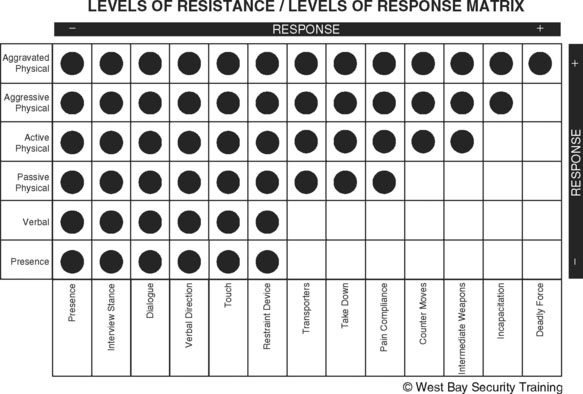

The use-of-force model can be a matrix, circle, steps, or a 90-degree angle diagram with a diagonal line indicating escalation. Models come in shades, colors, and lots of “X’s.” The common element is the relationship between what the subject does and what the officer does.

How things are described can make a difference in their being accepted by the population. Some call the “Use-of-Force Matrix” a “Response Matrix.” Many are shying away from terms that use the word “force.” “Level of Resistance” would be preferred to “Level of Force.” I once had a nurse tell me she wouldn’t use a “pain compliance technique” because “We don’t cause pain.” That same nurse had no problem doing the same technique but calling it a “sensory discouragement adjustment.” Today’s use-of-force guidelines generally include a “Level of Resistance” describing what the subject does and a “Level of Response” describing what the officer does.

Common descriptions of well-known behaviors include the following:

Levels of Resistance

1. Presence: A subject is present. Many times an officer can come onto the scene and recognize who he was called about just by seeing this person. The subject may be agitated, upset, pacing, or physically clasping and unclasping her hands. She may react when she sees the uniformed officer. If the officer had a description, he would key in on this person. It is important to realize the officer may not have complete information at this point. The person may be upset and causing a problem for a variety of reasons, not all of them criminal or with disorder in mind.

2. Verbal Resistance: A subject verbally refuses to do what the officer asked him to do. This may be in word only, refusing to leave, for example, or even refusing to speak with the officer. The speech may or may not be obscene, and the tone and volume might vary. This may be attended by aggressive body language, raised voice, and belligerent manner.

3. Passive Physical Resistance: At this point the subject is physically nonresponsive. In the case of a protester, she could be dead weight blocking a doorway. She physically refuses to obey but does not offer further resistance. Here, a police response might be called for if the officer’s communication skills are not effective.

4. Active Physical Resistance: A subject tries to get away from the officer’s attempts to control him. This could include “bracing or tensing” flailing the arms and running to elude capture. At this point the subject is not attacking the officer but is actively trying to get away. He might knock the officer down, but this act is clearly in an attempt to escape. At this point, many law enforcement officers are allowed to escalate to aerosol use.

5. Aggressive Physical Resistance: A subject attacks the officer. The subject is trying to do more than just get away at this point. The officer is clearly targeted and, from a legal standpoint, becomes a victim. The actions of the subject may cause injury but are not likely to cause death or great bodily harm. Verbal threats are common at this stage.

6. Aggravated Physical Resistance: A subject attacks the officer with or without a weapon with the intent and apparent ability to cause great bodily harm or death. This could be evidenced by great rage with threats and wild erratic body movements actively seeking to engage the officer.

Levels of Response

1. Presence: The officer is there in uniform and easily identifiable. Many times, this alone is sufficient to de-escalate the situation. A nonuniformed officer has the burden of establishing his authority and has to jump to dialogue immediately

2. I nterview Stance: The officer stands in a bladed position, strong side away with his hands in front of him. He stands outside the reach of the subject.

3. Dialogue: This response is a nonemotional two-way conversation with the subject and is considered investigatory. The officer is trying to find out what is going on, and the subject is expressing himself.

4. Verbal Direction: The officer tells a subject or gives a command to the subject to do or not do a specific action.

5. Touch: The officer guides with a gentle social touching or uses a firmer grip prior to escalating to a higher level of force. The officer must exercise good judgment at this stage because “social touching—the guiding on the arm or shoulder” might be offensive and counterproductive to some. Other guidelines eliminate this step altogether and go right to “custodial touching,” such as a transporter.

6. Transporters: The officer uses a control technique to guide the subject from point A to point B with minimal effort. Transporters include a “straight-arm escort” and a “bentwrist” technique.

7. Pain Compliance: The officer uses pressure-point techniques to encourage the subject to comply with the officer’s wishes. The “lateral thigh” technique and the “center ear control point” are two of these techniques.

8. Take Down: The officer directs the subject to the ground in a controlled manner. Takedowns include the “straight-arm technique” and the “bent-elbow push.”

9. Restraint Device: The officer uses restraint devices to temporarily restrain a resistive or potentially resistive subject to protect the citizens, the officer, and the subject. Restraint devices include handcuffs, leather restraints, flex cuffs, and Velcro restraints. Checking that restraints are properly applied and double-locking are critically important in this phase.

10. Counter Moves: An officer uses counter moves to impede a subject’s movement toward the officer. Counter moves include blocking, striking, kicking, and redirecting. Counter moves are followed up by controlling techniques such as a takedown.

11. Intermediate Weapons: Historically, intermediate weapons have been classified as batons and electrical and chemical weapons. Here, batons are used to control rather than strike the individual. Some put the taser in this category. The chemical weapons (aerosols) are often broken down into OC (pepper) sprays and all the other sprays. OC historically can be used at a much lower level than CS or CN sprays.

12. Incapacitation: In this phase the officer stuns or renders the subject unable to resist with nonlethal strikes. Batons are commonly used at this level. Tasers could be placed here also.

13. Deadly Force: Any force which is likely to cause death, great bodily harm, or in some cases, permanent disfigurement could be classified as deadly force. Strikes to the head, groin, or spine may be deadly force, and firearms are generally considered deadly force.

Many times the Levels of Response are grouped together under one number. For example, presence and interview stance are number 1. Dialogue, verbal direction, and touch are Number 2, etc. This allows for six Levels of Resistance and six Levels of Response.

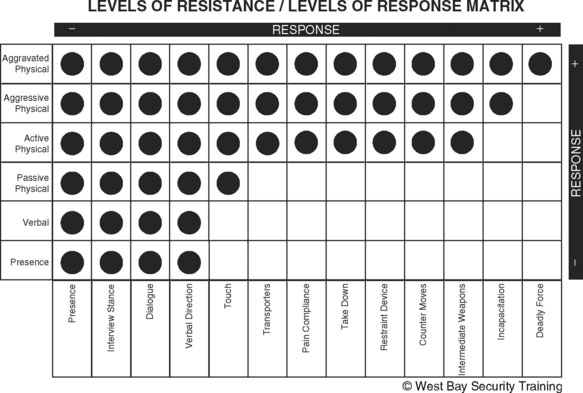

Now that we have identified the Levels of Resistance and Levels of Response, we need to know how to coordinate the two. This is where the matrix comes in (see Figures U-1 and U-2).

FIGURE U-2 A private security matrix. Fewer boxes are checked due to a more restrained response. For example, I have several clients who carry aerosol sprays and want them used only as a last resort when someone is being attacked. That changes which boxes are checked. Another example is that if you don’t use restraints at all, that category would not be on the matrix.

Training will address how the officers are going to respond with appropriate demeanor and defensive tactics as noted on the Levels of Response. The training should be regular, ongoing, and documented. If the training is not documented, then it did not happen. The training should be done by certified trainers with a documentable expertise in this particular field. This could be done by in-house staff that have attended “Train the Trainer” seminars or by bringing in outside subject matter experts. All documentation should be prepared and maintained as if it is subject to the “discovery” process of the legal community. Timed certifications are highly endorsed. State and federal guidelines, including but not limited to CMS and other regulatory agencies, must be obeyed. The legal units of the administration will have signed off on the policy.

Use-of-force training routinely involves helping the officer decide what type of response is justified. “Officer and Subject Variables” need to be considered when the officer is deciding how to respond. Some common factors include

1. Age: If the subject is old and the officer is young, the Level of Response might be appropriately less. If the officer is old and the subject is young, the age difference might justify a different response. The goal is to control.

2. Gender: The general public harbors the idea that females are weaker and therefore must be treated with less of a response than a man.

3. Size: Big subject, little officer could dictate a justified strong response.

4. Influence of drugs or alcohol: We know that 70% of the subjects arrested by police are under the influence of drugs or alcohol. The subject might not be comprehending the lower levels of communication attempted by the officer.

5. Previous history or known subject: This could determine the involvement and the Level of Response due to being able to get with the subject later. This could be a patient with a known history of aggressive behavior.

6. Injury or exhaustion of the officer or the subject: The average 35-year-old police officer has 45 seconds of full-blown fight in him. This might justify an escalation by the officer to apprehend or even being able to disengage.

7. Multiple offenders or multiple officers: It is not good to have the officer outnumbered. Multiple officers with a single subject would minimize the Level of Response.

This is the basic material used to construct a responsible use of force (Level of Response) to perceived threats. Think of it as a puzzle. Some parts you will use, others not. Cut and paste if you will, but remember the entire process must be blessed both by the administration and legal counsel. With such a policy in place, the facility can demonstrate a proactive posture toward maintaining a safe and secure campus.

Florida Department of Law Enforcement Criminal Justice Standards and Training Commission Basic Law Enforcement Defensive Tactics Curriculum

St. Petersburg College Criminal Justice Institute

Personal Protections Consultants, Inc.

IACP National Law Enforcement Policy Center Use of Force Model Policy

The Federal Law Enforcement Training Center Use-of-Force Model

Use of Off-Duty Police Officers in Loss Prevention

For several decades there’s been the on-going debate on the issue of using armed off-duty police officers to supplement the Loss Prevention staff in protecting a store. We refer to “armed” versus “unarmed” because, typically a police officer will not work unless he has his weapon. This issue of being “armed” is but one factor to consider when using police personnel. Your authors have had an off-duty officer shoot and kill a shoplifter and on another occasion an officer had his gun taken from him during a struggle and was shot with his own gun. Another situation saw a shoplifter take both the officer and LP agents hostage in the security office after taking the officer’s weapon. These are but three of many similar serious if not fatal events involving the use of off-duty police officers. If for no other reason, we are of the opinion the presence of firearms in a retail setting poses an unacceptable and unnecessary risk.

Historically, sworn officers are hired by various entities in the private sector specifically because their training is in keeping with special tasks, such controlling traffic for a film production, labor disputes, crowd control, temporary protection of high-profile dignitaries, etc. We urge their use be restricted to those type situations unless their use is clearly demanded and security cannot be achieved by traditional means.

But their use in mainstream loss prevention duties, such as detecting dishonest employees and shoplifters, often conflicts with the officer’s training and they tend to act on “suspicion”, quite appropriately in the general public, but not acceptable in the retail environment. One major big box retailer who has chosen to use off duty officers exclusively for LP functions has encountered national adverse publicity and numerous law suits resulting from the alleged use of excessive force (frequently resulting in death) by officer’s apprehending shoplifters. Following are other factors which mitigate against the use of off-duty officers:

• Police officers are not trained to consider “customer service”

• Police officers are trained to be reactive, not proactive.

• Police officers’ pay is generally much higher than that of LP personnel, tending to create some animosity when both are doing the same job.

• Police officers tend to follow police procedures and not the LP procedures of the retailer employer.

• Police officers have their primary loyalty to their city or county employer, and in times of emergency will be unavailable to the retailer.

• Police officer’s utilized as LP agents create a variety of complicated legal issues when engaged in making any but basic and “routine” shoplifter or dishonest employee apprehensions, including such issues as the officer’s obligation to “Mirandize” detainees whereas the “civilian” LP agent has no such requirement.

• The time required and wholehearted acceptance of store LP training of off duty officers is often missing.

The following is an excerpt from a posting made on a Loss Prevention website forum. It’s not to be construed as a universal attitude, but does subtlely underscore a not uncommon mindset of public sector officer’s commitment to what the retailer’s needs are:

“I once caught an off duty police officer sitting in the food court, reading a book, instead of patrolling the mall area I had hired him for. He told me, “You don’t pay me for what I do, you pay me for what I might have to do “.”

As security/loss prevention consultants, we advise caution in the use of off-duty police officers in the Loss Prevention setting.

However, all that said, it should be noted that our concerns are directed toward the use of police officers as line level store agents. Many police officers have made a career transition to middle and senior management in the retail LP industry, bringing with them the expertise gleaned from their public sector training, experience and responsibilities.

Use of Private Investigators by Retailers

Most but not all states have specific statutes for licensing private investigators (PIs) and private patrol operators (PPOs). Licensees must meet minimum experience levels designated by their respective states. PIs must pass a test administered by the state licensing authority. Licensees must pass a background investigation conducted by the licensing authority or other government agency statutorily authorized to do so. Most states require companies that provide investigative or security services to have a minimum amount of liability insurance, and some states require licensed companies to possess Errors and Omissions insurance.

It is wise for prospective clients to check with the licensing authority in their state to ensure that the licensee that they are planning to contract with is properly licensed and insured in the state that they are working in. Some clients take an additional step and require investigative and security companies to have their insurance carriers name the client as an additional insured.

Retailers’ use of private investigators (PIs) depends largely on a company’s size and culture and structure. Small business owners including retailers often contract with PIs to perform due diligence investigations when they plan on purchasing an existing business. PIs conduct background investigations on the business owners and their businesses to help determine if the information presented by the seller is true and if the prospective business is viable.

Small retailers use licensed investigators as loss prevention consultants when designing their security systems and policies. PIs conduct background investigations on prospective and existing employees and perform honesty and courtesy shops. Investigators often are hired to investigate internal dishonesty and various types of external frauds.

Mid-sized and large retailers generally employ security directors whose job it is to design security programs based on the company’s culture and needs. Security directors generally report to upper management and often to the company president or CEO.

Security directors are responsible for directing the company’s loss prevention efforts and developing and directing programs that are dedicated to identifying potential and actual shortage causing issues and responding appropriately to decrease retail shortage, often called “shrinkage,” and protecting the company’s assets and reputation. Security directors who are employed by companies with a proactive loss prevention culture usually control a substantial loss prevention budget. Private investigators are often part of the security director’s arsenal to supplement proprietary retail security department staffs.

PIs have years of investigative experience and provide specialized services like honesty shopping, interviewing suspected dishonest employees, and providing undercover operatives. Many PIs also provide loss prevention consulting, background investigations, certified fraud examiners, paleographers, security consulting, and a host of other specialties.

Private investigators have special skills sets, contacts, training, experience, and equipment that make them ideal for this task. By utilizing outside investigators, retailers take advantage of the expertise of PIs only when they require their services and don’t have to pay the high cost of salaries and benefits that would be required if the investigators were part of the retailers’ permanent staff.

PIs are often used for internal investigations because they may be viewed as more objective when investigating internal theft or other sensitive cases like threats of workplace violence, sexual harassment, hostile work environments, and executive misconduct.

I have worked a variety of internal cases for mid-sized retailers and reported directly to the CEO or the company president. In these instances, the companies did not have a security director on staff or the security director was a fairly low-level position more akin to a security supervisor, and the company did not feel confident that the security director had the experience or the ability to deal confidentially with sensitive internal investigations.

Small retailers use private investigators to investigate specific problems, or they may use them as security consultants or as liaisons with law enforcement. Some companies, large and small, outsource their entire security operation and investigative duties to licensed PIs and PPOs.

In most states private patrol operators are licensed to protect property and people. Private investigator licenses permit investigators to conduct investigations to identify a potential or existing problem so that the company’s management team can take the appropriate action to resolve the problem. Many private investigators have dual licenses and perform both investigative and preventative tasks.

Security directors who use PIs or PPOs often set aside a portion of their budget to employ PIs and PPOs to assist them in accomplishing their objective. By hiring outside professionals, they get a fresh set of eyes and skill sets that allows them to identify issues from a different frame of reference. They also reduce civil exposure because generally PIs and PPOs carry liability insurance that a retailer can subrogate against if the PI or PPO made an error and the retailer suffered damages.

Employment Background Investigation

Private investigators are often called upon to conduct background investigations on potential or current employees. PIs are considered credit reporting agencies (CRAs) when conducting most employment-related investigations. CRAs must follow the Fair Credit and Reporting Act (FCRA) and other applicable state and federal laws when conducting employment background investigations. Employers and their proprietary employees are not considered CRAs, and they do not fall under the FCRA when conducting employment background investigations unless they obtain information from a CRA.

The FCRA was written to protect the rights of consumers, which includes employees and potential employees. It was amended in 2003. FCRA rules prohibit CRAs from furnishing “consumer reports” for employment purposes unless the “consumer” is notified and consents in writing to the disclosure of the report. The signed release must be on a separate sheet of paper and cannot be mixed with any other forms, including an employment application.

At the time of this writing, if an employer has a properly worded and signed background investigation release, it is valid for the entire period that the employee works for the company. Employers and investigators should not utilize release forms that require prospective or current employees to waive their rights against an employer or CRA because these waivers have been ruled unlawful when challenged in the courts.

If adverse information is discovered as a result of the CRA’s investigation, and the employer intends to use the information for a personnel action including not hiring, terminating, demoting, or transferring the employee, or performing some other type of discipline, then the employer is required to provide a pre-adverse action letter to the employee, and the employee must be provided with a copy of the credit report. The applicant/employee is then given a reasonable amount of time to refute the information in the credit report prior to the employer taking adverse action. The applicant/employee may request that the CRA reinvestigate the matter and correct the credit report if the information that the CRA reported was incorrect. If adverse action is taken against the employee, an “adverse action letter” and a copy of the credit report must be provided to the employee who received the adverse action. There are additional requirements of the FCRA, and employers should familiarize themselves with the FCRA.

Two types of reports relative to background investigations may be requested from a CRA: consumer reports and investigative consumer reports.

Consumer Reports

Consumer reports are reports that a CRA gathers from public records like Department of Motor Vehicle records, court records, and credit reports that bear on a consumer’s creditwor-thiness, credit standing, credit capacity, character, personal characteristics, or mode of living. These reports are to be used or are expected to be used for employment purposes.

Investigative Consumer Reports

Investigative consumer reports contain information on a consumer’s creditworthiness, credit standing, credit capacity, character, personal characteristics, or mode of living, which will be used or is expected to be used for employment purposes. An investigative consumer report is produced from information gathered from interviews with friends, relatives, coworkers, former employers’ neighbors, and a host of other sources that might have information on the consumer/applicant/employee relative to the preceding criteria. Investigative consumer reports are generally more subjective than consumer reports.

It is legal for an employer who has obtained a valid release from the consumer to order both a consumer report and an investigative consumer report; however, the two reports must be separate and may not be blended together as one report. The Federal Trade Commission has been designated as the lead federal agency in enforcing the FCRA in employment matters. The Federal Fair Credit Reporting Act can be obtained online from the Federal Trade Commission’s website at http://www.ftc.gov/os/statutes/fcra.htm.

The FCRA has severe civil and criminal penalties if an employer or a CRA violates the FCRA. The FCRA has been changed several times in recent years. CRAs and employers must always be aware of the changes and apply the rules set forth in the current version of the FCRA. If a retailer does not have an active human resources department, it is recommended that the retailer become a member of an employers’ association or contract with a law firm that specializes in labor law to stay abreast of current labor laws.

Employers must ensure that the investigator that they are going to hire has a working knowledge of the FCRA before they hire him or her to proceed with an employment investigation. An employer’s representative must certify in writing to the CRA/investigator that the company will follow the FCRA before the CRA/investigator can proceed with the investigation. I have discovered that many employers and many attorneys who are advising employers are not familiar with the obligations and responsibilities of employers and CRAs under the FCRA.

Some states, including California, have their own version of the FCRA that has specific procedures written into the law that must be followed when dealing with employee cases. State versions of the FCRA are generally more strict than the federal FCRA. They sometimes have restrictions on the time periods for reporting information, and some states dictate what types of items can and cannot be reported on.

Undercover Operations/UCs

Retailers often hire private investigators to conduct temporary “undercover operations” when they suspect drug use, theft, or breaches of confidentially. There are advantages and disadvantages to using private investigators to work undercover.

The primary advantage of hiring a private investigator for UC services is that the retailer can place a fresh face in the business who can observe and report on activities of employees when company management does not inhibit the employees. UCs provide an accurate picture of employees’ activities and loyalties. The retailer can then take action as needed to resolve any problem that was discovered during the UC operation.

Licensed investigators meet with the employee, the UC, frequently to guide and direct his or her activity. The investigator must provide a method for the UC to make contact on short notice for guidance. A competent UC should be able to establish good enough rapport with the retailer’s employees that he or she is viewed as a confidant and may even take a passive role in the employees’ improper activities to obtain their confidence. The UC must do this without compromising the case or exposing the retailer or licensee to legal exposure. Retailers are able to change UCs or have the services of the UC terminated without fear of unemployment claims.

Disadvantages are that hiring a private investigative company to perform UC services is an expense. The retailer is paying the investigative company, and it pays the investigator performing the UC service. The retailer also pays the UC the going rate for the retail job being performed. The private investigator supervises the UC investigative activities, and the retailer supervises the retail activities.

Private investigators often hire investigators to perform UC investigations from locations that are a distance away from the retailer’s location, so there is little chance of the UC being recognized by one or more of the retailer’s employees. This adds to the expense for the retailer because the retailer is charged travel and housing expenses for the UC during the period he or she is working for the retailer. The retailer’s representative responsible for hiring the private investigator should interview the UC the investigators intends to place in the retailer’s business to make sure that he or she is compatible with the culture of the retailer’s business and properly understands the purpose for the undercover investigation.

The private investigator should perform a thorough background investigation on the UC and ensure that he or she is properly trained prior to being placed in the client’s business. The UC must take care not to report on union organizing activities or invade the privacy of coworkers, as these are violations of state and federal law. Retailers that have collective bargaining agreements with their employees must review their contracts to ensure that conducting undercover operations does not violate the collective bargaining agreement.

We have conducted a number of successful undercover operations for retailers. In one case, in his second week on the job our UC identified six associates that were stealing merchandise from their employer and violating numerous policies and procedures, including leaving early and having others punch them out on a time clock.

In another case, our UC worked at a large retail establishment for 5 months. During that time, he socialized with associates and was invited into their homes. He developed substantial information about associates who were violating numerous company policies and stealing and selling the merchant’s product on eBay. We concluded the case by interviewing the associates and obtaining written and tape-recorded confessions. Two of the associates were prosecuted, and several were terminated, along with our UC, for violating company policies.

Frauds

Private investigators are sometimes hired by retailers to investigate frauds that have been perpetrated against their retail businesses. Criminals who defraud retailers can be employees, outside people, or a combination of both.

Video surveillance systems are widely used in retail stores and shopping centers and have been successful in identifying many perpetrators of fraud. Private investigators can sometimes obtain valuable leads and even identify people who have committed a fraud by reviewing video of the area where the fraud occurred. Accepting proper identification when a customer passes a check and requiring customers to place their index fingerprint on checks are also means of deterring and identifying people who commit retail fraud.

The typical fraud that retailers suffer involves passing nonsufficient funds (NSF), account closed, or counterfeit checks. Perpetrators of fraud often pass a series of checks or a high-value check. Because law enforcement is reluctant to pursue these cases unless they meet the law enforcement’s minimum value threshold, PIs are sometimes hired to combine a serious of bad checks from one passer so that they cumulatively meet the agency’s cases. Even after an arrest warrant has been issued for bad checks, the perpetrators are sometimes arrested only if they are stopped by law enforcement for traffic or other violation of law.

Most areas of the United States have a team of law enforcement officers from city, county, and federal agencies. The teams are called a “fugitive task force” and led by a Deputy U.S. Marshal. They are charged with locating and arresting suspects who have outstanding felony arrest warrants. I have an agreement with the Supervising U.S. Marshal in my community that if I locate a person with a felony warrant and the marshal is able to confirm the warrant, the task force will arrest the suspect.

Many states have adopted Bad Check Diversion Programs for NSF checks. If a retailer accepts a check within the guidelines set by the local prosecutor’s office, and the retailer has notified the check passer that his or her check did not clear, the prosecutor’s office will send a letter to the check passer advising that person that if he or she does not make the check good within a limited amount of time, he or she will be prosecuted.

Generally, Bad Check Diversion Programs also require the check passer to pay the merchant for the check plus protest fees and involve paying a fee to the prosecutor’s office for processing and the case. In addition, check passers are required to pay an additional fee and attend a class to learn how to manage their checking account.

Check Diversion Programs usually limit the number of times that the check passer can go through a check diversion program to one time. If the person persists in passing bad checks, the prosecutor’s office may file charges against the check passer.

Unless check cases involve a significant loss, most metropolitan law enforcement agencies are hesitant to investigate these frauds unless the perpetrator is being detained or there are significant solvability factors to indicate that there is likelihood that the perpetrator will be identified. In recent years, law enforcement agencies has been inundated with violent crimes, and they generally do not have the personal assets or the time to investigate minor check frauds.

Law enforcement agencies and prosecutors’ offices often set a minimum limit on the amount of the check before they will investigate; sometimes in metropolitan communities the threshold is as high as $25,000. PIs sometimes fill in the gaps of the justice system and investigate fraud cases and identify the perpetrators. As a result of their investigation, PIs can often convince a criminal justice agency to pursue the case even though it is below the agency’s threshold.

Counterfeit Checks

PIs are sometimes hired to investigate counterfeit check cases in which a retailer has accepted the check. All that is needed to counterfeit a check is some basic knowledge of the banking system, a computer, a color copier, and check paper. These tools can be obtained at most office supply stores. Because these tools are easy to obtain, check counterfeiting has become popular. PIs are sometimes hired by retailers to conduct interviews, run down leads, and network with other investigators and law enforcement agencies in an attempt to develop a case against a counterfeiter. Counterfeiting of checks is often perpetrated by drug users and organized criminal gangs. People caught for counterfeiting checks usually are discovered because they pass numerous checks in a small geographical area in a short period of time or are arrested for some other crime.

Requiring the people writing checks to place their fingerprint on the check is a good means of deterring people from passing counterfeit checks and identifying them if they do. Note: A common trick of the criminal passing a counterfeit check is to place clear super glue on his or her index finger prior to entering a business to fill in all or part of the fingerprint and make it difficult or impossible for law enforcement to make a positive identification from the fingerprint.

Check Forgeries

Dishonest people who know the true account holder or have gained access to the account holder’s check supply often perpetrate check forgeries. They are frequently family members, friends, coworkers, or people who have access to the account holder’s business or residence. A common technique of the check forger is to steal checks from the center of the account holder’s check pad so that the account holder does not realize that checks are missing.

Retail employees should ensure that when taking checks for payment, they accept only official current government-issued identification. They must also make sure that the check passer is the person whose name and photograph appear on the identification.

These procedures will not protect a retailer against a person who has obtained the true account holder’s identity and has obtained valid government-issued ID in the victim’s name, but it will protect the merchant against the novice criminal who stole and passed the checks because he or she took advantage of the access opportunity and a relationship with the account holder.

Fraudulent Credit Card Investigations

Federal law says that in most instances a credit card holder is responsible for a maximum of $50 per credit card if the card is used fraudulently and the card holder follows established guidelines. Most credit card issuers waive the $50 fee as a customer service if the customer reported the loss of the card when he or she became aware of it.

Credit card companies have strict guidelines that merchants must follow; otherwise, they will not be paid if a perpetrator fraudulently purchases products or services with a credit card. Because storeowners, managers, and sales associates are customer oriented, they often waive one or more of the credit card company’s dictates. Because they can charge back the merchant for the fraudulent purchases, credit card issuers have little incentive to investigate the fraud. Private investigators are sometimes hired by retailers to investigate these cases. Investigators examine documents, interview witnesses, review video, and attempt to determine who actually committed the crime. If a suspect is identified, a case is put together and referred to the local police.

I investigated one credit card case in which a merchant transposed a number when inputting the customer’s credit card number into a point of sale cash register and a different person was charged for the purchase. This was due to an employee error and not theft.

When the account holder received his bill and was charged for items that he did not purchase, he filed an affidavit of fraud. We were able to identify the person who actually made the purchase with the assistance of the credit card company through the customer’s name and signature. The purchase was then charged to the correct cardholder.

In another case, a former employee of a mid-sized retailer obtained his roommate’s newly issued credit card from the U.S. mail while his roommate was traveling on business. The criminal used the card to make a large purchase from his former employer and was not recognized because he had not worked for the retailer in recent years. The perpetrator had been in the navy for the past 4 years. The roommate who had not opened an account eventually received a letter from the retailer and a gift certificate thanking him for his purchase. The roommate called the retailer and discovered that someone had obtained his identity, opened an account, and charged several thousand dollars’ worth of merchandise to him. The perpetrator had ordered the merchandise by telephone and came into the retail business and picked up the merchandise.

When the local police were contacted by the retailer, the police showed little interest in the case, which is fairly common in fraud cases. We were retained to investigate the case and discovered that the retailer has a sophisticated telephone system that logs incoming telephone numbers. We traced the cellular telephone number used to order the merchandise, and we identified and located the owner of the telephone who was not the perpetrator.

This retailer also had a video surveillance system in the store that photographed the perpetrator when he entered the store, picked up the merchandise, and when he left the store.

We made photos from the video and interviewed the owner of the telephone, who reluctantly led us to the perpetrator. We brought the case to U.S. postal inspectors, who are now perusing this case because the credit card had been sent by U.S. mail. Postal inspectors are also perusing charges against the same person for identity theft because he opened numerous charge accounts using his roommate’s name and information. The perpetrator and several of his associates made numerous purchases in northern Nevada and California using several fraudulently obtained credit cards in the roommate’s name.

Civil Cases

I have investigated a variety of cases for retailers and their insurance carriers. The most common retail civil cases have been for false arrest, slips and falls, worker’s compensation, and sexual harassment.

False Arrest/Unlawful Detention

Most states have laws that permit merchants to reasonably detain people that they suspect of shoplifting to determine whether the items that the suspect have in their possession have been shoplifted. When I have investigated these cases, the main issue has been whether the merchant saw the person remove the product from the shelf, conceal it, and exit without paying for the product. Taking a product without the intent to steal it is not a crime.

If a retailer cannot show intent by the suspect’s actions, like looking around, removing price tags, concealing product under clothing, leaving his or her own shoes in the new shoe box, and a host of other actions that tend to show intent, then it is probably unwise to attempt to prosecute someone or detain that person for a significant period of time. The merchant can detain the person to recover the product, but once the product is recovered, the clock starts ticking.

The false arrest cases that I have been involved in usually occurred because the person detained felt that he or she was treated unreasonably. Often the person placed the merchant’s product on another shelf and did not take it out of the store and the merchant’s agent placed him or her in handcuffs or embarrassed him or her in front of customers and employees.

I have investigated a couple of cases in which a security officer was apparently mistaken and did not see what he thought he saw. This sometimes happens to people who have years of experience in surveillance techniques. Light and shadows, distance, and obstructions sometimes create an optical illusion whereby a person thinks that he or she saw something, and the facts don’t confirm the vision. In one case a security officer caused minor injury to a person while trying to physically restrain and handcuff the suspect. The suspect, a juvenile, had not resisted and had not attempted to flee. There was no video in the area where the suspicious activity occurred or where the suspect was stopped.

When investigating these cases, I generally look at the scene and any evidence. I examine the company policy for detaining shoplifters. Was the policy reasonable? Did the agent follow the policy? Was the agent properly trained? Were witnesses present, and are their observations positive or negative for the retailer? Were the alleged suspicious activity and the arrest captured on video? I look at the agent’s training, experience, and work history. Had the agent made mistakes in the past, and were they similar in nature?

In this case, the suspect was a 13-year-old boy who was being accused of stealing a pair of sunglasses that retailed for under $10. He was detained for about 15 minutes until his parents were located. His parents and careful examination of the sunglasses confirmed that the glasses were not the merchant’s product, and they belonged to the juvenile.

The plain clothes security officer (agent) was a 19-year-old criminal justice major in his freshman year of college.

The company that employed the security officer rented retail booth space to small merchants at a weekend flea market. The business structure was a sole proprietorship. The agent had no security experience or training. There was no video, and the suspect’s 14-year-old friend was the only witness who had been identified.

I checked the civil history of the suspect’s immediate family and could not locate any prior lawsuits. In this case the suspect came from working class law-abiding family. According to his family, he had never been in serious trouble—only minor mischief. I spoke with a school police officer who described the juvenile as a good kid. The suspect was not seriously injured when he was detained, and he suffered only a sore wrist and some minor scratches, but he and his family were embarrassed.

The company did not have written policies but told the agent to detain anyone that he saw shoplifting and hold the suspect for the police. The security officer involved in the case had not been trained, and he purchased and was using his own handcuffs.

In this case the company was able to settle the case out of court a week after the detention for what the retailer and his attorney considered a token amount. The flea market owner was satisfied with the outcome, and he hired a licensed guard service for future events.

Slips and Falls

Slips and falls are common in retail stores and parking areas. Generally, if a person falls and is injured on a retailer’s premises solely due to the customer wearing inappropriate footwear or not paying attention, the retailer is not responsible for damages. Unfortunately, customers sometimes erroneously feel if they were injured on a retailer’s property, the retailer is responsible and they make a demand for damages. I have investigated numerous slip-and-fall cases. In some instances, the retailer created a hazard with poor lighting, lack of maintenance, or not cleaning up displays after customers have rummaged through the retailer’s merchandise.

In other cases, the floor was slippery and caused a customer to fall because the janitorial crew used a product on the floor that was not compatible with the flooring, and use of the product created a coefficient of friction of less then .05. In some cases, the floor was wet due to mopping and the retailer failed to properly identify and notify customers of the hazard and to block off the area until the floor dried, or the janitorial crew had left an electrical cord pulled across the floor and the customer tripped over it.

If a retailer created the hazard or failed to correct a problem that had occurred in the past when it should have been able to foresee the danger, the retailer will generally be held responsible in a court of law for the injured person’s damages.

I had one case that showed that the product was not compatible with the flooring that had been installed and it should not have been applied to the that type of flooring material.

In another case, the retailer, a franchise restaurant, had different levels of flooring and steps going to the various platforms. The stairs did not meet the uniform building code standard for steps. A customer who was wearing footwear that was slippery tripped and fell, severely injuring her arm. A paramedic who responded to the accident also stumbled on the steps where the customer fell. When I interviewed the paramedic at a later date, she told me that approximately 3 months prior to the customer being injured, she was patronizing the restaurant with her husband. At that time the off-duty paramedic tripped and fell on the same steps where the customer had fallen. In this case, there were uniform building code violations and a prior history of falls at the same location. As a result, the restaurant paid a significant settlement to the injured customer.

Worker’s Compensation Cases

In most if not all states in the United States, if a worker is injured on the job, his or her medical costs are paid for by the business’s worker’s compensation insurance policy, or if it is a large business, it may be self-insured. The company’s experience rating influences the employer’s cost because the insurance rates increase. If a company has few claims, then its rates are fairly low. If a company has an inordinate number of accidents or serious accidents with high medical cost or continuing medical treatment, its rates will be high.

Employers, including retailers, try to get their injured employees back to work as soon as possible even if they have to place the employees temporarily in a light-duty job so that they can be productive. This way, the employers or the worker’s compensation insurance carrier do not have to pay the employees when they are not contributing to the company’s success.

Some employees are malingerers, and they take advantage of their employers by embellishing their injuries and obtaining medical restrictions that they don’t really need or extending the amount of time that it takes to recover from their injuries when they have already healed.

I recently completed a job for a retailer whose employee suffered an on-the-job shoulder injury. The retailer brought the employee back to work in a light-duty job created just for him. He was in the light-duty job 16 months. The injured worker constantly complained that he was in pain and had to take frequent breaks; he called in sick many times due to the pain that he said he had from his injury. The injured worker’s employer knew that the injured worker had been a drummer in a local band prior to his injury. The employer requested that we perform a “Subrosa” investigation on the injured worker in an attempt to determine if he was physically performing beyond his medical restrictions when he was not working. “Subrosa” is a Latin term that means “Under the rose” or “undercover.” The injured worker had medical restrictions that prohibited him from lifting more than 15 pounds or raising his right arm above his shoulder.

I conducted Internet research on the injured worker’s band and located a photograph of the injured worker. The band’s web page contained a schedule of dates, times, and locations where the band was scheduled to play. I set up a mobile video surveillance outside the injured worker’s residence 2 hours prior to the next scheduled band appearance and observed him carrying and loading a complete drum set into his vehicle.

I followed the injured worker to the nightclub where the band was scheduled to play and videotaped him unloading his drum set and carrying it into the club. I paid the fee to enter the club and videotaped the injured worker setting up his equipment and assisting other band members with unloading, carrying, and setting up their equipment. When the band was performing, I videotaped the injured worker playing his drums for almost an hour and then breaking down his equipment and carrying it to his car.

Two days later I provided two copies of the video to the injured worker’s employer. The employer provided a copy of the video to the injured worker’s physician who had established his medical restrictions. The physician was embarrassed that the injured worker had duped him and immediately removed the medical restrictions. When the employee showed up to work Monday morning, his employer played the video of his band performance for him and then terminated his employment.

Worker’s Compensation/Subrogation Case

A 25-year-old female who was married and had four small children was working at a rural Nevada convenience store that had a gas and propane station. The oldest of the woman’s children was 5 years old.

A man brought in an empty 5-gallon propane tank to the store and requested that it be filled. The tank was within code and looked like it was new. It was early evening and beginning to get dark. The customer accompanied the clerk to the propane pump, and she began filling the customer’s propane tank. The clerk and the customer apparently heard propane escaping, so the customer backed off. The clerk turned the 5-gallon propane tank over, and the tank exploded. The bottom portion of the tank was propelled upward, and it blew the clerk’s face off. The clerk expired at the scene almost immediately.

Investigation by the local sheriff’s department, Nevada State Fire Marshal, and the Nevada Propane Board disclosed that the bottom of the 5-gallon propane tank had been cut and caulked in place and painted over to hide the caulking.

When law enforcement officers interviewed the customer, he said that his propane tank was out of date, so he went to his neighbor’s residence and asked if he could borrow a propane tank. His neighbor located a tank in her garage and gave it to the customer.

Propane tanks that are caulked on the bottom are sometimes used to smuggle drugs into the country. An interview by law enforcement officers confirmed that the woman had given the propane tank to the customer. The woman’s husband was serving a term in Nevada State Prison for possession of drugs for sale and selling drugs. When the husband was interviewed at the prison, he said that he had purchased the propane tank at a flea market and was not aware that it had been modified.

Investigators from the worker’s compensation insurance carrier, a state agency, conducted a subrogation investigation. Their investigation determined that the customer and the woman who lent the customer the tank did not have sufficient assets for the state to subrogate against. I received the case one and a half years later with a request to re-investigate and attempt to determine where there was an opportunity for subrogation. I discovered that the customer had died of a heart attack and left only a small trailer to his elderly parents. The woman who lent the propane tank to the customer was a renter, and she had few assets and a husband in prison.

I interviewed the retailers and discovered that there was a contract with the propane company. I read the contract and discovered that the propane vendor, a large corporation, was responsible for training the managers and owners of the store in proper procedures for filling propane tanks. This training is necessary because propane is a hazardous product.

The contract spelled out exactly how the vendor was to train the owners and management of the convenience store and that the training must be documented on the propane vending company’s forms and kept on file by the propane vending company.

The contract also required that the owners and managers of the store train their subordinates in the proper procedures for safely filling propane tanks. The training was to be recorded on the propane company’s forms, and a copy was supposed to be sent to the propane company to be reviewed and filed.

I examined copies of the training records and interviewed the station owners and their employees. The interviews disclosed that the propane company had not properly trained the owners and managers who were training their employees. The propane company’s policies and forms required that the people being trained demonstrate proficiency by checking and properly filling a certain number of propane tanks in the presence of the instructor. In this case the instructor cut the number of training cycles from 7 to 3, and the instructor scratched off 7 from the form and wrote in 3 and initialed the forms.

This accident could have been prevented if the deceased employee had properly inspected the propane tank. As a result of training deficiencies on the part of the propane company, it settled with the state and the family of the deceased worker for $1,000,000.

Had the case not been subrogated, the insurance carrier—in this case, the State of Nevada—would have been responsible for all damages and support of the deceased’s four small children until they were 18 years old. The retailer’s workman’s compensation insurance cost had been raised significantly because of the death claim. After the settlement, the insurance company reduced the retailer’s insurance rate to the former amount and repaid the retailer the additional monies that had already been paid as a result of the claim.

Sexual Harassment Investigations

Private investigators are often hired to perform sexual harassment investigations when an employee makes a complaint that his or her employer, manager, or supervisor has made unwanted sexual comments, touched him or her inappropriately, or sexually harassed him or her in some other way as defined by state and federal laws.

Private investigators are often retained to conduct an unbiased investigation to determine if the allegation is true. Investigators review the complaint and interview any witnesses and in some cases other employees who are subordinate to the accused.

I conducted one investigation for a restaurant where the manager was accused of constantly touching, making lewd comments, propositioning female employees for sexual favors, and telling sexual jokes. All these things were against company policy.

One of the accusers was terminated prior to her complaint for excessive cash register shortages. After her termination, she filed a sexual harassment complaint with the State Equal Rights Commission. She said that she had verbally notified her employer of prior instances of sexual harassment and requested that they speak with the manager.

The restaurant group’s CEO and the female human resource manager visited the restaurant weekly and always spoke to all the employees. They said that they had not received any complaints of sexual harassment until after the employee was terminated for cash register shortages. The former female employee returned to the restaurant several times after she no longer worked there, and she talked to female employees, encouraging them to join her in a lawsuit against the company for sexual harassment. No one else joined her. About a month later, another female employee told the restaurant manager that her family circumstances required her to request a schedule change. The manager was not able to grant her request, and the employee resigned. Soon after, she complained to the company that her manager had sexually harassed her, and she filed a case with the Equal Opportunity Commission.

I interviewed all the restaurant’s employees individually at an off-premises location. I provided them with the definition of sexual harassment and asked if they had ever been victims or witnessed anyone sexual harassing anyone at the restaurant. A few of the female employees said that customers had harassed them, but they dealt with the problem without telling management. They said that they would sometimes hear and tell sexually oriented jokes among themselves, but these jokes were not usually told in the presence of their manager. None of the employees heard or saw their manager do or say anything that could be considered sexual harassment.

After the initial accuser was terminated, she told several of the employees that she had been sexually harassed. She told them this when she tried to get them to join her lawsuit. She also said that if they joined her lawsuit, they could get a bundle of money. The employees said that they did not believe her and said that she often told lies.

I interviewed the manager. He denied the complaint and said that the complaints were made in retaliation for terminating the initial accuser and for not granting a schedule change to the second accuser. I conducted background investigations on the manager and his accusers. The manager did not have a criminal record. A female employee at a former job had accused him of sexual harassment; however, the complaint was never substantiated, and it did not go beyond his former employer.

Investigation disclosed that both of the accusers were currently admitted drug users who were in a court-supervised drug program at the time of their complaints. The initial accuser had an active felony arrest warrant for failure to comply with a drug court order.

I interviewed the accuser’s former employers and found that neither of them had made complaints of sexual harassment; however, both had been terminated for company policy violations. I located and interviewed the initial accuser’s ex-husband; he described the accuser as being extremely promiscuous and constantly lying. He said that he had married her because she was pregnant with his child. He introduced me to several friends of his who have known the accuser for many years. They also described her as extremely promiscuous and constantly lying.

This case was eventually tried in U.S. District Court, and the court found in favor of the employer.