L

Labor Disputes: Managing Them

Introduction

Few events tax an organization at the level of a labor dispute. Most critical incidents—natural disasters, bomb threats, workplace violence incidents, and the like—quickly move from the “acute” phase of the crisis situation to the resolution and recovery phases. Not so with labor disputes, which can carry on for days, weeks, or even months with, at times, seemingly no end in sight. Moreover, labor disputes can rapidly alternate from relative calm to, at times, full-scale riotous situations, only to return to a manageable level once again. This constant state of “alert” causes an enormous drain on many branches within an organization, not the least of which is the loss prevention or security department.

A key distinction, however, between the crisis events cited here and a labor dispute is that with the latter there is almost always ample warning. In the security and crisis management world, ample warning unequivocally means preparation time.

Preparation Is Key

It is important to keep in mind why we prepare for a strike. Our objective is to protect lives, protect property, and maintain business continuity to the extent possible. Therefore, the preparation phase is the most important phase of a labor dispute. Many problems can be mitigated or averted altogether with an exhaustive preparation and contingency plan in place.

Given that most strike-related activity centers around company facilities (offices, stores, plants, warehouses), these should be the main areas of focus when preparing for a labor dispute situation. The following are a number of pre-strike preparation areas to consider for company facilities. Note that these are all areas to address prior to a strike even beginning (time permitting).

1. Key control: Make certain you know the location of all facility keys. Collect those not in use and secure them in a safe.

2. Lock protection: The age-old gimmick of squirting glue into keyholes lives on. This problem can generally be mitigated by applying petroleum jelly into keyholes because most glues do not stick to this lubricant.

3. Sensitive interior rooms: Most facilities have one or more “high-risk” rooms (e.g., manager’s office, cash room, computer room, motor room). For these, make certain that all doors can be locked and are functioning. If you have double louvered doors, make certain that deadbolt locks are installed. Have a locksmith respond if time allows.

4. Armored safes and lock boxes: Open only when necessary, namely only to transfer funds to an armored transport. Keep in mind that armored transport personnel generally have a second key. Place important documents inside a safe or lock box.

5. Personal safety: Labor disputes are emotional and traumatic events. People involved oftentimes act in a manner quite different from their “normal” behavior. Educate employees not involved in the dispute regarding personal safety and security. Remind them to be on alert and avoid “routines,” such as travel routes home.

6. Receiving dock: This area is oftentimes more isolated and thus presents a tempting target for acts of arson, vandalism, or attempted break-in. The area should be made clear of extraneous items, such as bales, pallets, and totes. The area should be well lighted, kept secure, and, if at all possible, under video surveillance.

7. Lighting: Ensure that all parking lights, signs, and perimeter building lights are in working order. Re-inspect frequently.

8. CCTV: If so equipped, ensure that all cameras and recording systems are in working order. If time permits, add cameras as deemed necessary. A minimum camera standard should include all points of ingress/egress, building perimeters, and “high-risk” areas (e.g., parking areas, loading dock).

9. Alarms: Ensure that all alarms (intrusion, fire) are in working order. Ensure that fire extinguishers are available and accessible.

10. Front doors and windows: Items that obstruct external viewing should be removed from doors and windows. This also allows patrolling law enforcement visibility into the facility.

11. Facility perimeter: Ensure that all emergency exits are not accessible from the outside. Make certain that tree branches, fences, etc., do not allow access to the roof. Ensure that external phone lines, if present, are shielded to protect against cutting.

12. Strike incident forms: Draft and produce strike incident forms for local management personnel to use in documenting strike-related incidents. Include specific instructions as to what should and should not be documented. Assign incident “levels” to help in minimizing data overload. Online incident forms also assist in quick and uniform data collection.

13. Strike “kits”: Build a strike kit to include multiple disposable cameras with flash, flashlight and batteries, strike incident forms (discussed later), pens/pencils, petroleum jelly, emergency phone numbers (fire, police, security or loss prevention, management personnel).

14. 24-hour hotline: Establish, disseminate, and post a 24-hour hotline for reporting of emergency strike incidents. Ensure that this can be manned 24/7.

During a Strike

Once a strike begins, there are additional steps to take. These steps can be broken into two categories: steps to follow immediately after the strike begins and best practices for the duration of the event.

Once the Labor Dispute Begins

• As striking employees leave at the end of their shifts, retrieve and secure keys, access cards, and other company-owned property

• Be mindful that some employees may attempt to sabotage or tamper with equipment, stock replenishment orders, product displays, and security systems on their way out.

• Ensure that all “preparation” steps described previously have been considered and implemented, where possible.

• Make arrangements to have all lights (inside and outside) remain on throughout the night.

• Verify that there are no flammables outside the facility, such as cardboard bales, trays, crates, pallets, or boxes.

• Bring in merchandise or other property as able.

• Secure all perimeter doors, roof hatches, and interior “high-risk” doors (see preceding description).

Best Practices Throughout the Strike

• Documenting strike incidents: Begin the strike incident reporting process immediately (see previous comments). It is important to maintain accurate and timely records of all strike-related incidents. Make certain that all assaults, vandalism, and other crimes are reported to local law enforcement and to security or loss prevention. Obtain full names, complete addresses, and all other pertinent information of witnesses and victims (the strike incident form should contain boxes for this information). Document license plate numbers, if applicable, and take photographs when illegal strike activity is witnessed (before ordering the perpetrators to stop). Illegal strike activity may include, but is not limited to, the following:

• Physical threats: In the event that an employee, customer, or vendor/contractor is verbally or physically threatened, the person-in-charge of the incident location should contact local law enforcement.

• Bomb threats: Expect an increase in bomb threats. Follow established bomb threat procedures.

• Property damage: Expect an increase in vandalism incidents. Remember that employee and customer safety and business continuity have priority, and that minor vandalism incidents can be dealt with when/if time permits.

• Temporary personnel: Many labor disputes involve temporary employees. Make every effort to ensure temporary employee safety and security. If the employee parking area cannot be observed from the store, have employees park offsite and carpool to the work facility. Provide a secured area for storage of employees’ purses and personal property.

Obtaining and Enforcing Injunctions

At some point during the labor dispute, it may become necessary to seek a restraining order or an injunction. There are certain considerations to keep in mind.

The Right to Strike and Picket

Employees have the right to strike in support of their bargaining demands or to protest alleged unfair labor practices. Employees and unions also have the right to engage in peaceful, nondisruptive picketing to publicize their strike. Companies mush respects these rights and must not do anything that unlawfully interferes with them.

Limits on the Right to Picket and Injunctions Against Unlawful Conduct

The right to engage in picketing and other activities to publicize or support a strike is not absolute. For example, picketers may not engage in violence, make threats, unreasonably interfere with ingress or egress to or from private property, or engage in other unlawful conduct. If a company can prove that picketers or other individuals, acting at the union’s direction or with the union’s knowledge, engaged in any of these prohibited activities, it may request that a court issue a temporary restraining order (TRO) to stop such activities. (TROs and injunctions do not necessarily prohibit picketing altogether. The union and its supporters may still engage in peaceful, nonthreatening, and nondisruptive activities in support of their strike.) A TRO generally remains in effect for 10 to 30 days, after which time the company may seek a preliminary injunction, and ultimately, a permanent injunction. Violations of such court orders constitute contempt of court.

The Procedure for Obtaining Injunctions

Courts are generally very reluctant to limit anyone’s free speech rights, and some states, such as California, have made it even more difficult to secure an injunction limiting the number or conduct of picketers in support of a labor dispute. For example, in many instances an employer must now present live testimony in court to obtain a TRO. This has changed from earlier procedures wherein mere written declarations would suffice. Moreover, law enforcement has generally refrained from becoming involved unless and until a TRO or injunction is in effect.

Preparing to Get an Injunction

The foregoing requirements are very strict, and the evidence that you must present to convince a court to issue a TRO or injunction must be very specific. Whenever possible, you should cite the names of wrongdoers and the union representatives who were present when unlawful conduct occurred. In addition to describing said conduct in as much detail as possible based on eyewitness observations, the employer must also be prepared to present evidence which establishes that the union directed, condoned, or was present when the unlawful conduct occurred and did nothing to stop it. Hearsay, speculation, rumor, and innuendo are not sufficient to convince a court to issue a TRO.

Enforcement of Injunctions: Dealing with Law Enforcement

TROs or injunctions normally contain specific limitations on the number of picketers and/or prohibit certain conduct by the picketers and by union representatives and other supporters. The union, its representatives, and its supporters who are served with these court orders are legally obligated to comply with their limits and prohibitions.

Law enforcement agencies’ policies and practices regarding the enforcement of TROs and injunctions vary by jurisdiction. Some will actively enforce the TRO, whereas others will refrain from doing so because they do not want to be perceived as taking sides in the dispute. The Vons’ experience demonstrated that establishing a good relationship with law enforcement could make all the difference in determining whether they will enforce any TROs and injunctions. There are three steps a company can take to improve such relations with law enforcement:

Citizen’s Arrests

Some law enforcement agencies will arrest individuals who knowingly violate the limits or prohibitions of a TRO or injunction. Others may require that company personnel make a “citizen’s arrest,” especially if officers did not observe the unlawful conduct themselves. Employers should become aware of the various practices of the law enforcement agencies in their area.

Labor Disputes: Some Considerations

Having gone through a major labor dispute involving hundreds of retails clerks from a headquarters store of a national chain, I discovered, primarily through trial and error, some techniques that proved most helpful. These “tips” are listed here by subject matter.

Identification of Replacement Workers

During a labor dispute when the regular employees go out on strike, replacement workers, consisting of executives, friends, and relatives, are usually used as replacements for the regular staff. Since a strike rarely occurs without some warning, these replacements can be identified and trained prior to their first day of work.

These replacements should be instructed where to report for work, and after being positively identified, they should be issued some form of identification. In addition to issuing a company “pin-on” name badge, we found that also issuing a distinctive pin, the design and/or color of which changed daily, served as a second security measure to help assure that only legitimate persons were operating cash registers or POS terminals. We found we could obtain from a variety of sources (which should also be changed frequently) small pins which were issued each day after replacements were positively identified. Security/LP personnel were aware of the “pin of the day” and could challenge any worker who was not displaying one. Frankly, this procedure was copied from the Secret Service’s routine use of such a procedure.

Employee Entrance

We found maintaining more than one employee entrance helped eliminate the replacement workers having to go through the gauntlet of jeering, shouting, and rarely overly aggressive strikers massed outside the store’s regular employee entrance.

Temporary Restraining Orders (TROs)

The company’s labor attorneys should, at the first opportunity, seek a temporary restraining order (TRO) limiting the number and location where picketers are permitted. Obviously, every effort should be made to minimize the picketers’ ability to interfere with customers attempting to enter the store. We were successful in obtaining a TRO which limited the number and distance from store entrances picketers were permitted. We also found it helpful to use an orange color spray paint to mark the areas denied to picketers, as spelled out by the TROs. This procedure eliminated arguments between labor leaders, picket captains, and store security agents in maintaining the terms of the TRO. In those few cases in which the restrictions were violated, this arrangement also help the police when called to enforce the TRO.

Police Liaison

It is essential that liaison with the local police department be established, since it is the police who are responsible for enforcing TROs. A TRO is a court order and has the full force and effect of law. Violators are subject to arrest for TRO violations, and while this ultimate means of enforcing them is most often not required, we have seen arrests for TRO violations.

Merchandise Delivery to Stores and DCs

Depending on which unions recognize the dispute and choose to honor picket lines, pre-arrangements for delivery of merchandise and supplies by nonunion drivers will assure both adequate replenishment of stock but also minimize the potential for disputes and/or violence. Again, police presence, arranged for in advance, will prove beneficial.

Planning

The follow items were on a pre-event planning checklist; a specified security executive was assigned responsibility for each item:

• Have coordination meeting with key security personnel.

• Review security department personnel availability; review vacation schedule.

• Issue standby order for all or part of security staff.

• Coordinate with outside contracted guard companies for labor dispute locations and offsite or temporary locations.

• Obtain and have on hand sufficient security equipment, such as bullhorns, video, still photography equipment, and portable recorders. Also provide training for personnel who will use equipment.

• Determine number, placement, and dates for contract guard placement.

• Develop and conduct contract guard orientation.

• Develop contract guard post orders.

• Perform total in-store inspection of sensitive areas and emergency equipment; note deficiencies.

• Coordinate armored car money pickup.

• Assign official recorder at all affected sites.

• Secure panel rooms and cabinets.

• Obtain distinctive identification badges.

• Establish extra employee entrances.

• Place nonstriking security managers and other security personnel from stores on standby.

• Ensure exterior window covering availability, i.e., precut and sized plywood panels.

• Coordinate possible alarm company schedule changes.

• Check radio for control center.

• Obtain extra beepers for key command center or executive committee members and security executives.

• Provide security orientation for new hires.

• Update emergency phone numbers at guard office.

• Establish data processing center access control and security.

• Install external guard phones at distribution centers.

• Verify physical security of temporary distribution centers.

• Obtain and have on hand special security equipment and supplies for running temporary distribution centers, e.g., cameras, videos, bullhorns, etc.

• Ensure security of staged trucks and sites.

• Establish liaison with police department senior officers and dispatch.

Special Equipment

Arrange for the availability of any special equipment which it is anticipated may be needed, including

2. Two portable battery-operated camcorders and replay equipment; these items are required to record any untoward events taking place by pickets, for use both to obtain injunctive relief and for possible later legal action.

3. Pocket cards with emergency phone numbers.

5. Topographical map of blocks containing buildings with distances and all entrances shown.

7. Portable battery-operated bullhorns.

8. 35 mm automatic camera, with telephoto lens, and supply of ASA 200 film.

9. Portable battery-operated tape recorders.

10. A direct telephone line between the control center and the divisional security office.

11. An adequate number of outside line and internal line telephones for the control center.

12. A supply of “incident cards.”

13. A chalkboard for titling, dating, and showing other ID data for videotapes.

It is important to assure that qualified and properly trained personnel are available to operate the special equipment listed here; any training of such personnel should take place well in advance of the anticipated need for the use of such equipment.

Law Enforcement Officers as LP Agents

Some companies hire law enforcement officers (LEOs) to augment their regular LP staff, some hire only off-duty LEOs for the LP staff, while still others have a prohibition against using LEOs as LP agents. If used, should these officers be in uniform or plainclothes? Is there a police department policy regarding working off duty in uniform? What happens if the officers are injured? Who is responsible for medical and disability benefits? What is the correct position to take on these issues?

We believe that with rare exceptions (special events, executive protection, or other unusual situations) the practice of using LEOs as LP agents should be avoided.

Why? It is our experience that the training of LEOs is reactive in nature, whereas LP training is preventive in nature. Additionally, LEOs have a different mindset than LP agents: LEOs tend to obtain their objectives through the authority and power of their peace officer status, whereas LP agents tend to recognize their restricted limitations and hence rely more on persuasion.

In most jurisdictions LEOs are required to be armed at all times—on duty or off. This means armed LP agents—a situation which is not recommended.

Another consideration: LEOs are rarely willing (or able) to put in the hours we suggest are necessary for training in LP procedures and policies and thus are poorly trained for their LP responsibilities. Contrary to common belief, police academy training does not prepare a person for the legal issues and responsibilities in the private sector.

If LEOs are employed to work with proprietary LP agents, we have found this arrangement produces a real potential for a contentious relationship between them. The company agents are upset over the normally higher pay given to LEOs for the same work and, as noted, with less total knowledge of the job.

Finally, law enforcement officers’ primary loyalty is to their public sector department, not to the part-time employer and that can create conflict in judgment calls. Also of concern is the fact that in times of a civil emergency, off-duty police officers must report to their department at a time when they are also needed at their secondary employer.

In summary, we believe that, as a rule, the disadvantages significantly outweigh the advantages of utilizing LEOs as loss prevention agents; therefore, we do not recommend this practice.

Law Enforcement Retail Partnership Network

LERPnet.com: Getting Connected

Within the United States, thousands of public and private sector databases collect information about people, crimes, and retail. Many of these systems draw from publicly available data sources such as credit, court, property, and personal data records maintained by consumer reporting agencies. Others, such as mutual associations, share information about employees dismissed from retailers or shoplifters apprehended, regardless of prosecution. All of these data sources serve as a tool for us to identify repeat offenders or employees who fail to disclose incidents in their background. The Law Enforcement Retail Partnership Network (LERPnet) will serve as a national repository for major retail incidents, linking retailers and law enforcement across the nation to this valuable source.

Drawing on the experience of law enforcement to share information in near real-time, LERPnet was modeled on the National Crime Information Center (NCIC); see http://www.fbi.gov/hq/cjisd/ncic.htm. On January 20, 1967, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) created the NCIC to provide a computerized database for ready access by a criminal justice agency making an inquiry and for prompt disclosure of information in the system from other criminal justice agencies about crimes and criminals. This information assists authorized agencies in criminal justice objectives, such as apprehending fugitives, locating missing persons, locating and returning stolen property, as well as in the protection of the law enforcement officers encountering the individuals described in the system.

[Legal background: The system is established and maintained in accordance with 28 U.S.C. 534; Department of Justice Appropriation Act, 1973, Pub. L. 92–544, 86 Stat. 1115, Securities Acts Amendment of 1975, Pub. L. 94–29, 89 Stat. 97; and 18 U.S.C. Sec. 924 (e). Exec. Order No. 10450, 3 CFR (1974).]

An everyday use of the NCIC data:. Law enforcement agencies enter records into the NCIC, which are, in turn, accessible to law enforcement agencies nationwide. For example, a law enforcement officer can conduct an inquiry of NCIC during a traffic stop to determine if the vehicle in question is stolen or if the driver is a wanted person, and the NCIC system responds instantly. However, a positive response from the NCIC is not probable cause for an officer to take action. NCIC policy requires the inquiring agency to make contact with the entering agency to verify the information is accurate and up-to-date. Once the record is confirmed, the inquiring agency may take action to arrest a fugitive, return a missing person, charge a subject with violation of a protection order, or recover stolen property.

Unfortunately, the losses suffered as a result of burglaries, organized retail crime, robberies, etc., may never be entered into NCIC. If a store is burglarized in one city, the local agency will take a report and, as resources allow, investigate the crime. In larger cities, hundreds of cases may be filed each day, so the retailer suffers a significant financial loss without much hope of recovering any product, or making an arrest.

Smart criminals may commit the same crime over several cities, counties, or states and at a variety of retailers. Without good communication and coordination, they could do so for months or years before anyone would connect the dots.

Over the past decade we have seen a transformation within our industry. The ability and need to share information on a near real-time basis with hundreds or even thousands of users has become a minimum standard of any technology application. To create a system to share crime data within the private sector and between traditional competitors would require precedent-setting work on behalf of the private and public sector, many with competitive corporate philosophies, not to mention the financial support.

According to the National Retail Security Survey, produced by Dr. Richard Hollinger at the University of Florida, shrinkage in 2005 was $37.4 billion, the largest loss in the history of his report.

When you look at the latest official crime statistics available, in 2004 the FBI Uniform Crime Report claimed losses from auto theft at $7.6 billion, burglary $3.5 billion, larceny $5.1 billion, and cargo theft between $12 and $15 billion. These crime categories combined do not total the annual shrinkage rates suffered by the retail industry. In fact, since crimes like fraud and cargo theft are not included as company shrinkage, the $37.4 billion is much, much higher.

The current efforts to combat retail crime are a collection of disparate and redundant deployments and efforts, with some successes, between various retail segments and individual companies. Unfortunately, the loss prevention and law enforcement community data, systems, and efforts are not coordinated and integrated to address common goals.

Since there is no commonly used standard, schema, taxonomy, or directory for finding, integrating, and linking data elements and content, there are insufficient ways to selectively share or widely disseminate information about retail crime to all parties.

Retail crime intelligence is not widely available or used by law enforcement to fight retail crime. Most data-sharing opportunities do not provide sufficient flexibility as to what is shared and how it is shared to allow corporate managers and legal departments to approve participation.

In January 2006, the Federal Bureau of Investigation announced LERPnet as the single national database to prevent, detect, and investigate major retail crime incidents. LERPnet connects traditional competitors and law enforcement nationwide, using a high-security web interface with links to retail case management systems. The system developed by retailers and law enforcement officials was designed to

• Prevent crime and apprehend criminals;

• Reduce the cost of retailing by reducing crime against retailers and their customers;

• Provide a safe shopping experience and excellent customer service;

• Serve as a data source to educate legislators, the public, and the media about retail crime across the country.

The core platform, designed by members of the retail community, were led and supported by the National Retail Federation loss prevention team, Richard J. Varn, and a group of talented information technology folks at ABC Virtual.

Richard Varn, the former CIO of Iowa and currently the president and CEO of RJV Consulting, was the perfect person to lead the technology aspect of this effort. Mr. Varn has extensive experience serving both government and private sector clients, making him an ideal project manager. He served as a state representative for 4 years and served as a state senator for 8 years. During that time, he was twice elected majority whip; created and chaired the first Communications and Information Policy Committee; and chaired the Education Appropriations, Human Services Appropriations, and Judiciary Committees. In addition, he was the director of Telecommunications and IT Production Services at the University of Northern Iowa. Mr. Varn brought a wealth of technical knowledge and background to this project, given his public sector background and work in the private sector, specifically with retailers.

ABC Virtual (ABCV) was selected based on its experience with the public and private sector. What impressed us was their experience building systems to share information across diverse entities in the financial and local government communities. Al Baker, Adrienn Lanczos, and Jim Howard at ABCV designed LERPnet to support millions of records with a clean front- and back-end interface. In addition, their experience in the financial community gave us the ability to apply top-tier security.

There were many law enforcement advisors during the development stage; however, three played a major role in their feedback and support of the system: FBI Major Theft Unit Chief, Eric Ives; FBI Supervisory Special Agent, Brian Nadeau; and Montgomery County Police Department, Detective David Hill. Without the exceptional effort of these dedicated folks, LERPnet would not have obtained a national presence in the law enforcement community.

LERPnet was launched with high expectations:

• Provide the retail loss prevention and law enforcement communities with information, data, and analysis to prevent, detect, respond to, prosecute, and recover from retail crime;

• Provide a forum and technology platform for the exchange of information and data;

• Enable the retail LP community to work together toward common goals as much as possible in a competitive environment;

• Develop systems and processes for maintaining strict adherence to participants’ wishes regarding the ownership, access, privacy, security, and integrity of the information and data provided;

• Maintain a high standard of excellence in the provision of services in their availability, reliability, accuracy, interoperability, and usability.

Three extremely important factors were unanimously voiced during the initial meetings with retailers and law enforcement.

First were system security levels. One of our steering committee members had just been involved with the theft of proprietary data for a contracted company. This raised the concern that retailers would be entering not just proprietary information, but also their ugliest secrets about robberies and other major crimes taking place. In response, we deployed the system with a mandatory third-level authentication schema.

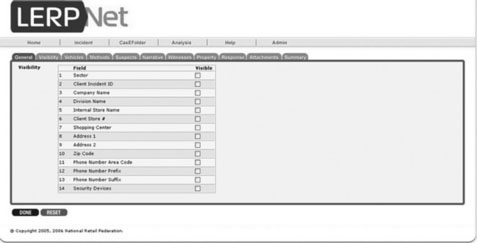

Second was the need to suppress, or hide, data elements by the submitting company. This would allow companies to report large losses without fear of their out-of-stock position being disclosed to a competitor or users of the system inadvertently releasing confidential information (see Figure L-1).

Finally was the need for vendor neutrality. During the discussion about financing the system, several individuals proposed having key vendor partners fund the system on behalf of retailers. As the discussion progressed, it became clear this was a contentious issue. Loss prevention executives are somewhat partial to their existing vendors, and we recognized early on that LERPnet would need to connect to all the various commercial and proprietary case management platforms.

Following the initial meetings we began working on the project in three ways:

Design and Implementation

Using a comprehensive development model, the programmers coded the system to the specifications our steering committee members provided. Simultaneously, the system was reviewed by retailers and legal experts to validate the process and make recommendations along the way.

We utilized several legal experts during the development and deployment process. The system needed to exceed the standards of security and data privacy and remain unregulated by the Fair Credit Reporting Act. Our ultimate goal was to provide loss prevention executives with every argument for supporting the system with public relations (users can suppress any data about their company), general counsel (most data are already public record with police agencies, and LERPnet secures the data even further), and operations (providing a tool for preventing, detecting, and investigating losses within the company).

Current State

The first version of LERPnet was originally shown to NRF Loss Prevention Conference attendees on June 28, 2005 (then under the name the Retail Loss Prevention Intelligence Network, or RLPIN). The pilot system was not operational; however, the screenshots gave attendees a good feel for the future functionality and the feedback was overwhelmingly positive. We were also able to discuss the system functionality with attendees and gain additional requirements before the public pilot period.

Basic Operating Protocols

Since LERPnet was developed with busy loss prevention and law enforcement professionals in mind, the system is largely made up of check boxes, drop-down menus, and quick entry fields (see Figure L-2). Anyone who works with databases today understands a misspelled word or inconsistent data capture techniques can seriously impact the results of a query or report.

Our steering panel of retailers recommended we focus on major retail crime incidents to start and expand the content over time. Information in LERPnet is classified by sector and incident type, as shown in Table L-1.

| Sectors | Incident Types |

|---|---|

Data are fed into the system using three different techniques:

• Direct entry: Users can enter data directly into the system using a series of friendly web-based forms.

• Import: Knowing a majority of retailers already capture incident information using Excel, Access, or a case management program, LERPnet is set up so that companies can export case information from their system and the technical gurus can upload the data into LERPnet.

• Automatic feed: Several companies are developing direct data feeds into LERPnet. For example, one large department store chain is developing a check box on each company incident report that instructs its internal system to automatically send the information to LERPnet.

The benefits of feeding data into LERPnet work both ways. Today, when a company examines incidents by month, it has exposure only to data within its system. With LERPnet data, that company can compare internal statistics to stores within its sector or the industry as a whole. We see this capability as having residual benefits in resource acquisition and deployment nationwide.

Each incident has unique attributes, so it was important to build intuitive screens to guide users throughout the reporting process. When a user enters incident details about an organized retail crime incident, the system requests information about how the crime was completed (distracted associate, booster bag, lookout, removed sensor tags, etc.). If the user changes this incident to a robbery, the attributes change (displayed weapon, took employee hostage, threatened customers, etc.). The attributes for each type of incident are different, so LERPnet keeps users on track through these structured forms.

The page layout was designed to capture every important detail about an incident and structures the information in a manner easily understood by law enforcement or loss prevention professionals from other retailers.

One of the big benefits of developing LERPnet with public and private sector input was our ability to capture diverse data elements. For example, when capturing information about suspects, you would expect to find information about height, weight, clothing, and weapons used. Law enforcement would want to capture information about tattoos, street names, and any link back to NCIC records (Federal ID #). While some of this information would be useful to retail professionals, they are also interested in items like email address, instant messenger screen name, and auction/seller ID. All these elements are attributes captured in LERPnet.

The core system today allows users to upload photographs into the system. We are working with several technology experts to allow video uploads and have the streams return to users through a common format (such as Windows Media Player). Another module in the development plan is what we call “photo array.” Imagine taking a group of incidents with like methods and photos and displaying them side by side to see if the suspects look alike. All of this is possible in LERPnet.

Some other features that users find very useful are custom email alerts, queries, and reports. Each user can develop a library of commonly request data elements:

• Email alerts: If you work in specialty retail and are responsible for stores in California, you may want to see only incidents in California occurring in specialty stores. When an incident matches the criteria you specify, an email is sent to your computer, cell phone, or pager.

• Queries: Everyone loves to benchmark and LERPnet is the ultimate tool. Based on the data today, California leads the country for ORC cases, followed by New York. With LERPnet, you can identify the best/worst sector, incident type, and with enhanced reporting tools, you can find the worst city and state for each incident type. Whether you are in the public or private sector, imagine using this type of information when presenting a case to your boss about getting more resources.

• Reports: From a “top-down” perspective, look at the entire industry or just pick a sector. As the results come back, they are hyperlinked to the data below, so you just have to point and click to see the detailed data you’re looking for in LERPnet.

Law Enforcement Access/Support

When the LERPnet system was built, it was decided that law enforcement needed free access to the system. Working with the FBI, approved public sector officials will access LERPnet through Law Enforcement Online (LEO.gov), a secure system the FBI uses to share information between agencies.

Law enforcement officials will simply access LEO.gov and go to the Organized Retail Theft section on the site. From there, each user can request access to LERPnet. Once approved by the FBI Headquarters team, the user will have access from any secure terminal at the station or patrol vehicle with the proper permission to enter the system.

The National Retail Federation is the world’s largest retail trade association, with membership that comprises all retail formats and channels of distribution, including department, specialty, discount, catalog, Internet, independent stores, chain restaurants, drug stores, and grocery stores, as well as the industry’s key trading partners of retail goods and services. NRF represents an industry with more than 1.6 million U.S. retail establishments, more than 24 million employees (about one in five American workers), and 2006 sales of $4.7 trillion. As the industry umbrella group, NRF also represents more than 100 state, national, and international retail associations. See www.nrf.com for more details.

Legal Cases by Subject Matter (Case Law)

Fermino v. FEDCO, 30 Cal Rptr 2d 18 (1994)

Parrott v. Bank of America, 97 C.A. 2d, 14 (1950)

Ware v. Dunn, 80 C.AS. 2d 936 (1947)

Scofield v. Critical Air Medicine, Inc, 45 Cal App 4th 990 (1996)

Legal Considerations

Our legal system attempts to strike a balance between the rights of persons and private organizations to protect their lives and property and the rights of citizens to be free from the power or intrusion of others. This balancing act is nowhere more evident than in the field of security.

In the security business, many of our “tools of the trade” may easily and unintentionally become the catalyst for a civil lawsuit. How is the injured party redressed or made “whole”? In our system, money is the means of redress; a court or jury decides how much money will adequately compensate the injured party to basically put that person in the position he was in before the injury or damage. Our tort system is really a “redistribution of wealth” system.

Damages awarded in security-related lawsuits have skyrocketed in recent years; 20 years ago, suing for tens of thousands or even thousands of dollars was considered high; today suing for hundreds of thousands and millions of dollars is almost commonplace. Let’s examine how these awards reach these levels.

• Special damages are awarded to replace actual out-of-pocket expenses of the plaintiff, e.g., medical bills, lost wages, attorney fees, etc.

• General damages are awarded to “make the plaintiff whole”; these are the monies awarded to compensate for pain and suffering, emotional distress, mental anguish, loss of consortium, etc. The more the jury is outraged by the defendant’s conduct, and the greater the injury or damage to the defendant, the higher these awards will be.

• The combination of special and general damages is commonly referred to as compensatory damages; i.e., they compensate the plaintiff for injury.

• Punitive damages are awarded when the plaintiff can establish that the defendant was grossly negligent, wanton, or was motivated by malice. For punitive damages to be awarded, there must be clear and convincing evidence that the defendant’s conduct was not merely negligent or the result of honest error, but rather that he acted with malice, fraud, gross negligence, or oppression. Punitive damages are designed to punish and/or set an example to others to avoid such conduct.

While compensatory damages can be covered by insurance, in California (and most other states) it is against public policy for insurance to cover the cost of punitive damages.

Now that we’ve seen the severe damage that can result from successful and even unsuccessful civil lawsuits resulting from the alleged tortious conduct of security personnel, the next question is this: Why is the employer held accountable for the wrongdoing of an employee, particularly if the employee is acting against the instructions or directions of the employer? After all, don’t we as employers instruct our security personnel as to how we want them to behave and conduct themselves? Don’t we tell them to be polite, not use excessive force, not make “bad stops”? So why are we held accountable?

The reality is that most security employees are not wealthy and don’t have the financial resources or assets to provide any significant (or even insignificant) amount of money damages. Therefore, the plaintiff seeks a corporate “deep pocket” (or someone of financial stature) to sue so that the money is available to pay any damages awarded. This quest for big dollar assets usually brings the plaintiff to the employer who has assets or is at least insured for big dollar policy limits. So how do the misdeeds of employees get imputed to their employers? Several legal theories are utilized to impute employee liability to the employer.

Ratification

If an employee commits a tort and the employer, upon learning of it, doesn’t take appropriate corrective action, which many will argue means termination, then the employer may be said to have “ratified” or approved of the act. the employer is therefore just as liable as if the employer had directed or committed the tort.

Respondeat Superior

Respondeat superior is a legal doctrine which holds that an employer (principal) is vicariously liable for the acts and omissions of its employee (agent) committed “within the scope of employment” but not generally liable for acts committed outside the scope of employment. The primary questions which determine if the employee was within or without the “scope” are as follows: Did the employer benefit from the act of the employee? Was the employee acting under the authority or direction of the employer?

A relatively new theory in the law, that of negligent hiring, may be used to circumvent the respondeat superior defense that the employer is not liable because the employee acted outside the scope of employment.

Agency

Agency is a relationship wherein one party is empowered to represent or act for the other under the authority of the other. Agency means more than tacit permission; it involves a request, instruction, or command. There are three types of agency relationships: principal and agent, master and servant, and proprietor and independent contractor.

• A principal directs or permits another to act for his benefit; e.g., a real estate or insurance agent acting for the broker or company.

• A master is a principal who employs another and has the right to control the servant’s physical conduct.

• A proprietor owns or operates a business; an independent contractor contracts with another to do a job but is not controlled by or subject to the other’s right to control the physical conduct in the performance of the job.

Course and Scope of Employment

Is the act of the employee either directed by or for the benefit of the employer? Obviously, liability for an employee who assaults his neighbor on his own time cannot be imputed to the employer. But what about the employee who, on his own time, invades the privacy of another in furtherance of an investigation connected with his employment? Is the employer liable?

These are complicated legal issues. When such questions are raised in lawsuits, they will be answered by the court if the question is a legal issue or the jury if it is a factual issue.

What Is a Tort?

A tort, or civil wrong or injury excluding breach of contract, is a violation of a duty owed to the individual who claims to have been injured or damaged. Tort law governs the civil relationships between people in any given situation. Some of these relationships that may become the focus of tort law arise from

• The U.S. Constitution: search, arrest, etc.

• Federal statutes: Civil rights violations

• Agency law: When an employee acts for his employer.

• State law: Criminal statutes, which are also torts, e.g., battery, assault and false imprisonment, invasion of privacy.

• Other administrative, regulatory, or state and federal statutes which may regulate security activities: Citizen’s arrests, merchant’s detention laws, licensing, insurance, use of force, privacy (eavesdropping), etc.

Unintentional Tort

The only unintentional tort is negligence, although there can be many alleged negligent acts.

The California Supreme Court, in a case involving a retailer, instructed the jury as follows regarding negligence:

Negligence is the doing of something which a reasonably prudent person would not do or the failure to do something which a reasonably prudent would do under the circumstances similar to those shown by the evidence.

It is the failure to use ordinary or reasonable care.

Ordinary or reasonable care is that care which persons of ordinary prudence would use in order to avoid damages to themselves or others under circumstances similar to those shown by the evidence.

You will note that the person whose conduct is set up as a standard is not the extraordinarily cautious individual, nor the exceptionally skillful one, but a person of reasonable and ordinary prudence.

A test that is helpful in determining whether or not a person is negligent is to ask and answer whether or not if a person of ordinary prudence had been in the same situation and possessed of the same knowledge, he would have foreseen or anticipated that someone might have been damaged by or as a result of his action or inaction.

If that answer is “yes,” and if the action or inaction reasonably could be avoided, then not to avoid it would be negligence. [Pool v. City of Oakland, 42 Cal 3d 1051 (1986)]

Simply put, a store owner has a duty to provide customers (legally, business invitees) with a safe shopping environment. If that duty is breached, and if it was for foreseeable that harm might arise from the breach, and that “but for” that breach the victim would have suffered no injury or damage, then we have negligence.

For example, is it foreseeable that a shoplifter being chased by a store detective may run into a customer and injure that person? Yes. If this happens, is the shopkeeper negligent? Maybe. Does this mean that store security should never chase shoplifters? Not necessarily, but it is an element of store security procedures which should be well thought out and perhaps some perimeters established.

It is curious that courts have ruled both ways on this issue; the majority of courts have held the likelihood of customer injury is not so great that stores should refrain from chasing shoplifters. What, however, if the store employee is the one knocking over and injuring the customer? Here, this issue is much clearer.

When the employee acts outside the scope of employment, the employer may be insulated from liability. Since most employees are not of adequate financial stature to pay large awards, attorneys have developed a relatively new body of negligence law designed to bring liability to the employer where previously it would not have fallen. These cases are the various negligent hiring, training, supervision, entrustment and retention cases.

How do you avoid negligence? By conducting yourself in a reasonable manner and doing those things which a prudent person would do to avoid the foreseeable injury or damage to someone which could arise by failing to do those reasonable and prudent things.

Negligence torts require no intent.

Intentional Torts

It is the reasonable subjective view of the victim of intentional torts which is normally determinative of tortious conduct. In other words, it is not what the actor thought or intended, but rather what the victim thought or felt.

False Imprisonment/Arrest

False imprisonment is the intentional, unjustified detention or confinement of a person; false arrest is the unlawful restraint of another’s person’s liberty or freedom of locomotion. Note: This may also be a criminal offense.

In shoplifting situations, you can avoid false arrest allegations by being certain your cause to believe shoplifting is taking place is based on reasonable observations, not mere suspicion.

Merchant’s Privilege

Many states, recognizing the tremendous shoplifting problem, have enacted so-called Merchant’s Privilege statutes, which grant merchants and their agents the right, under specified conditions, to detain suspected shoplifters and which grant them protection from certain civil suits, provided that all the provisions of the statutes have been met.

While the exact language of the Merchant’s Privilege or Merchant’s Detention statutes varies from state to state, in general, such statutes require that

• The detention be based on probable cause that the person to be detained was committing a theft;

• The detention be for the purpose of investigation;

Additionally, many such statutes limit the use of force to nondeadly force and prohibit or limit searches of the person.

If the merchant meets all the statutes requirements in making the detention, these statutes then provide that in a civil action resulting from a detention, the merchant has a statutory defense to such action, provided he acted reasonably under all the circumstances and that the detention was based on probable cause to believe the person detained had stolen or attempted to steal merchandise.

All these laws require that the merchant act reasonably and on probable cause in making the detention, so the issue becomes how the merchant can clearly establish probable cause. We believe that the long recognized “Six Steps” to a shoplifting detention, if followed, clearly establish probable cause for the detention.

Six Steps for Shoplifting Detentions

1. You must see the suspect approach the merchandise.

2. You must see the suspect take possession of the merchandise.

3. You must see where the suspect conceals the merchandise.

4. You must maintain an uninterrupted surveillance to ensure that the suspect doesn’t dispose of the merchandise.

5. You must see the suspect fail to pay for the merchandise,

As stated, the merchant must also have acted reasonably. How is this behavior established?

In torts, the element of “reasonableness” is a key factor. Just what is this concept of reasonableness? Essentially, actions which are reasonable are those that a hypothetically prudent, reasonably intelligent person would consider to meet the judgment that society requires of its members for the protection of their own interests and the interests of others. Conversely, actions which outrage, vex, appear malicious or excessive, or tend to make one angry when considering the alternatives available may be considered “unreasonable.”

Torts Alleged as a Result of Shoplifting Detention

What are the torts which may be alleged as the result of a shoplifting detention? They are

• Assault/battery: Unconsented to or unprivileged physical contact or privileged contact which becomes unreasonable. Note: This may also be a criminal offense.

• Malicious prosecution: Prosecution (civil or criminal) with malice (evil intent). To succeed, prosecution must have resulted in a verdict for defendant and prosecution initiated without probable cause.

• Invasion of privacy: Invading someone’s reasonable expectation of privacy.

• Defamation (libel-slander): Written or spoken words that tend to damage another’s reputation. Defenses: Truth, privileges (qualified and absolute).

• Tortious interference with employment: Maliciously interfering with the employment of another.

• Tortious infliction of emotional distress: Intentionally and maliciously inflicting emotional distress on another.

Since the test of negligence or appropriate behavior when reviewing intentional torts is reasonableness, the ability to avoid unreasonableness is essential. How do you avoid being unreasonable? Since the question of reasonable behavior is one of fact for a jury to decide, no black-and-white answer can be given. However, if you know the concept and limit your behavior to actions that are demonstratively necessary and prudent, and which do not exceed the bounds of propriety, which would not be offensive to the average person under the circumstances, then chances are those actions, if reviewed, will be considered reasonable.

Malice, as mentioned earlier, is something done solely to annoy or vex; something that is done out of ill will with no justification and in wanton and willful disregard of the likelihood that harm will result. Malicious acts can never be reasonable

Why Is All This Important?

In today’s litigious society, avoidance of expensive lawsuits (whether won or lost) is important. We are in the business of loss prevention, and creating situations resulting in civil suits results not only in adverse publicity for our companies, but in unnecessary financial expense and losses as well.

Little we do in the retail environment can so easily result in lawsuits as the activities involved in loss prevention. Shoplifting detentions are, by their very nature, adversarial and confrontational. Dealing with employee dishonesty enters domains which may be the subject of federal and state regulations, privacy issues, and labor relations.

Thus, when taking loss prevention actions, it is essential we know who should do it, what should be done, when it should be done, where it should be done, and how it should be done.

The ultimate object is to convince a jury that we acted reasonably under all the circumstances and our actions were commenced based on probable cause.

Civil Litigation: Avoidance and Cost Control

It goes without saying that the best way to avoid civil litigation is to avoid doing the things that result in injury to others for which they seek remedy through civil lawsuits.

However, as Alexander Pope wrote in the 18th century “To err is human; to forgive divine.” We can anticipate that mistakes will be made and that, in many cases, they will not be forgiven; hence, lawsuits are inevitable, and the ability to control their cost becomes important.

The time to start controlling civil suit costs is before the suit is a reality. When an improper or inept loss prevention action insults or injures a customer, one of several things will likely happen:

• The retailer will receive a phone call or letter from the customer.

• The customer’s attorney may call or write.

• The store is served a summons and complaint noticing a lawsuit.

How should these actions be dealt with?

In the case of a phone call or letter from the customer complaining of mistreatment during a loss prevention incident, the store should immediately contact the customer and state its concern over the allegations and advise the customer that an immediate inquiry will be made into the complaint and he will be contacted within a short period of time. This contact with the customer should be made by a company executive, and while no specific commitment should be made, the company’s sincere concern over the complaint should be stressed.

If, after a thorough investigation into the complaint, it is determined that there is no merit to the complaint, the customer should be contacted an advised that an unbiased inquiry has determined his complaint lacks merit, but that in the interests of maintaining the customer’s good will, the store is willing to … here, the store must determine what action it will take. It is noted that in some cases the complaint is totally without merit and the store may simply relay this to the customer. In other cases, where there was a good faith and reasonable basis for the store’s action, but nevertheless the action was unjustifiable, the store may offer a letter of apology or some monetary compensation. Obviously, if the action was totally unjustifiable (e.g., store policies were violated), the extent to which the store will go to satisfy the customer will be more generous and extensive.

The secret, however, is to do everything within reason to keep the customer from contacting an attorney. When attorneys get involved, costs automatically escalate, since now both the attorney and customer require compensation, and attorneys recognize that most retailers hate adverse publicity and have “deep pockets”; i.e., they have insurance and the ability pay large monetary awards. Stores should avoid having their own attorney or insurance carrier make the initial contact with the customer because the customer may then feel the need, in self-defense, to seek legal advise.

We note that any written apologies should be relatively general in nature, apologizing for any embarrassment or inconvenience the customer suffered. Such letters should avoid language which could establish legal admissions of tortious or criminal conduct. We suggest that such letters be cleared by company counsel before being mailed.

If a phone call or letter is received from the customer’s attorney, the same general strategy as described previously should be followed. It is important that the attorney be assured that the store is sincerely interested in resolving this matter as quickly and fairly as possible and that any resolution will be achieved by dealing with the attorney rather than directly with the customer. This caveat assures the attorney that any monetary settlement will go through him, assuring him he will not be bypassed or uncompensated for his efforts.

If a summons & complaint (or other formal means of advising that you are being sued) is received, the store should contact its insurance carrier at once and let the carrier and its designed lawyer deal with the issue from that point forward.

A final thought: In dealing with the customer, his attorney, or your insurance carrier, it is vital that you are as forthright as possible. Nothing is gained (and there is much to lose) if facts are withheld, distorted, or manipulated. Document everything completely, beginning with the initial report covering the action which caused the complaint, and every subsequent action taken in an effort to resolve it. If a suit is filed, it may take years to reach court, and complete documentation, together with evidence of your sincerity and honest efforts at resolution, constitutes one of the best defenses and damage mitigation in such suits.

Liaison with Law Enforcement

The question frequently arises as to the proper relationship between loss prevention and law enforcement (LE). The answer is: It depends on several factors, including

• The size of the city/town and its LE department;

• The attitude of LP toward law enforcement;

• The attitude of law enforcement toward LP;

• The policy of the company toward cooperation with law enforcement.

We have found, throughout our careers in various venues, that an honest effort toward establishing a close relationship with law enforcement had a real benefit to LP efforts. Several examples of these benefits will underscore this point.

Local law enforcement officers (LEOs) recover obvious stolen merchandise during an unrelated investigation. If they know and have confidence in the professionalism of the local head of LP, they are likely to call him and report their find of stolen merchandise, which may alert LP to a serious problem as well as a recovery.

In another venue, LP’s relationship with local LE was so close that LP agents were frequently invited to participate in raids on fencing operations known to deal in merchandise carried by that store. In addition, the store often “loaned” fairly significant amounts of merchandise to LE for use in sting operations. I found this close relationship with the local LE’s fencing unit to be mutually rewarding and beneficial.

I had a colleague who was formerly employed by a leading federal investigative agency, and this fact resulted in another beneficial relationship with that agency.

Finally, knowing not only working LE officers but also senior LE personnel, from the chief on down, on a first-name basis was found to helpful; when the assistance of LE was needed, it was certainly not a disadvantage to be able to call the chief of police by his first name and make a request for assistance.

We realize that some LP senior executives feel that LE “looks down” on LP and feel that they represent “a bunch of wannabes” who were unsuccessful in their efforts to join the ranks of LE. It is true that some LE personnel, both of senior and lower rank, harbor these views. We also believe, however, that one way to convince LE that these views are misguided is to establish a working relationship with LE and demonstrate that LP personnel can be just as professional as their counterparts in public LE.

While we do not, as a general rule, support hiring LE personnel as security/LP agents, (See “Law Enforcement Officers as LP Agents”), in some situations the hiring of a retired senior law enforcement officer who is otherwise qualified by education and experience for a staff position in the LP department may prove to be a good investment. If such a hiring is considered, it must be done with great care, since my experience has been that very few LEOs at any rank make successful LP agents. Occasionally, however, a young command-level LEO with a college degree who has demonstrated management skills may be a wise hire. Such a person can often help both LP and LE to appreciate the skills and professionalism of both groups to their mutual benefit.

Lighting: Outside

The need for adequately illuminated parking areas is discussed in the “Parking Area Crimes” section of this book, and the thrust of that piece deals with lighting while customers and employees use the parking area. However, there’s a need for some outside lighting when the store is closed. Some exterior lighting should be provided to the dock or receiving area, to the dock pedestrian door, any emergency exits, and to the employees’ entrance. The latter is to accommodate early morning employees, such as housekeeping personnel, who arrive before sunrise.

There are risks at these locations, albeit not high, but they include entry made by cutting an opening in the closed and locked metal dock doors with an acetylene torch, and interception of early morning employees by gunmen intent on a major robbery of the cashier’s cage. Additionally, lighting these areas makes it easier for routine police patrols to spot any suspicious activity, and the light itself will act as a deterrent to criminal activity. Failure to light such areas, should a major crime occur, would be a form of security negligence.

Lockers

Employee Lockers

Many employers provide lockers for their employees to store personal items while at work. The problem is that such lockers can also be used to stash stolen property and/or items whose possession is prohibited in the workplace, such a drugs, weapons, or pornography.

How can the misuse of employee lockers be minimized? By utilizing the following procedures:

• Do not permit employees to provide their own locks; provide company locks and have the employees sign for them. This should be spelled out as policy, and we suggest the topic be a part of the employee handbook. The policy should state that if private locks are used, employees must remove the lock in the presence of a supervisor or LP and replace it with a company-provided lock. Private locks are subject to being cut and removed.

• Locks provided should be of the type which permits a master key to open them.

• Post signs in the locker area stating: “Employee lockers are subject to inspection at any time with or without prior notice; use grants permission.”

• When conducting locker inspections, always have a witness, preferably a nonexecutive staff associate.

Public (Coin Operated) Lockers

We strongly recommend that all coin-operated lockers be removed. We urged this position prior to 9/11, and do so even more adamantly now. The potential for use for illicit or terror-related purposes is too great to overcome any so-called customer convenience or income generated by their use.

The “terror” threat means an explosive or otherwise dangerous device could be placed in the locker and be armed to detonate at any given time.

The “illicit” threat, best exemplified years ago when they were common in large stores, was that lockers would be loaded with unpaid-for merchandise by employees who worked inside the building while the store was closed to the public, such as janitors, and the key to such lockers would be passed to a friend or relative who entered the store when open and removed the goods.

Loss Prevention as a Concept

Historically, retail security departments focused primarily on apprehending shoplifters and dishonest employees. Although continuing, and rightly so, to place a major emphasis on deterring and detecting employee theft, studies have been less than convincing that there is any correlation between apprehension statistics and shortage. Therefore, to totally address shortage reduction, which, after all, is the main objective of a protection program, the focus had to be modified. This was accomplished by the concept of “loss prevention”; i.e., the protection efforts should be directed toward shortage reduction, which in turn increases profitability.

Four elements are necessary for a successful loss prevention program:

1. Total support from top management

2. A positive employee attitude

3. Maximum use of all available resources

4. A system which establishes both responsibility and accountability for loss prevention through evaluations that are consistent and progressive

There are many loss prevention programs, but we suggest that to maximize the shortage reduction potential, the program must include several key elements, including

• The program must be ongoing and have an impact on shortage throughout the inventory period.

• The program must have a consistent method of addressing shortage such that any new executive or employee can immediately pick up where the former employee left off.

• A process must be in place which enables total loss prevention efforts and involvement on the part of all employees, from the officers of the company down to the newest hires, as well as individual efforts toward shortage reduction to be evaluated.

The preceding elements can be achieved by a program which targets those areas or merchandise groups which comprise 50–60% of total shortage. These areas are audited frequently on a set schedule, with consistent audit topics, covering all conditions which contribute to shortage. Such conditions include (but are not limited to) neatness, evidence of missing merchandise, missed markdowns, salvage, found EAS tags, fitting room conditions, misrung merchandise, missed price changes, employee awareness, staffing levels, missing price tags, etc.

By frequent auditing of high-shortage areas and responding with appropriate fixes to problems found, shortage cannot help but be reduced.

Loss Prevention Manuals: Content & Preparation

Recognizing that loss prevention manuals are obtainable through legal discovery procedures in the event of a civil suit, we suggest that, with the approval of legal counsel, the following subjects be included in a security/LP manual:

Loss Prevention: Theory and Procedures

LP Policies and Procedures as They Relate To

While we have suggested some subtopics under the Introduction section, we have not endeavored to do so for the other sections, since each company’s philosophy and operating procedures will vary, and any such attempt by us would not only be presumptuous, but inapplicable to many readers.

What we do suggest, however, is that a manual be prepared by major categories of operations, with pages numbered by a numerical system that allows for periodic updating and the insertion of new pages, which can be properly indexed. For example, the Introduction section may start with Page 1.00. The first subtopic, the LP Mission, would be numbered 1.1.0, followed by the Role of the LP Chief Executive numbered 1.2.0, etc. The next major section, Loss Prevention: Theory and Procedures, would be numbered 2.00, with subtopics following the numbering system for Section 1. Should an additional page be subsequently required, for example, The Role of the LP Chief Executive in 1.2.0, that page could be easily inserted as page 1.2.1 without necessitating completely renumbering the entire section.

It is also important that a permanent record be kept of revisions or additions to the manual by topics, page number, and date. This information is extremely important should the manual (and its contents) ever be used in court when a particular policy or procedure, and adherence thereto, comes into question.

Every loss prevention employee, from new-hire entry personnel to new employees who come to the company with prior LP experience, should be required to read the LP manual and sign and date a statement they did read and do understand the material contained therein. That statement should be made a part of each employee’s training or personnel file.

A copy of the manual should be available in each of the company’s facilities for easy reference by LP personnel.

Since manuals are discoverable and contain proprietary information, we strongly suggest making every effort to protect this information from becoming public, and that the procedures outlined in our section on “Proprietary Information” form the basis for this protection.

Lost or Unaccompanied Children

Lost children are defined as preteenage boys or girls down to toddlers who clearly are separated from their parents and appear to be without adult supervision in the store.

The merchant has a duty to take reasonable steps to ensure harm does not befall customers or children while in the store, and youngsters wandering in the store pose a risk of harm to themselves, i.e., are vulnerable to abduction or sexual assault while in the confines of the store. There is also the potential risk of injury from using escalators or knocking down mannequins or other items that could injure them or others. Abductions and assaults are not common fare but, on the other hand, are not unknown. Aside from the shear tragedy of any untoward incident victimizing a child, the store would be exposed to the a risk of civil liability.

Policy, then, should require the training of all store associates to approach such children and determine where their parents are. Parents engaged in shopping can and do lose sight of their children, and often the associate can guide the child back to a grateful (and often an abashed) parent.

In the event a parent cannot be immediately located, a member of management or LP must be contacted, and two or more either should search the store with the child in tow or retire to the office and announce over the store’s paging system that a little boy named Charlie is looking for his Mom, for example. In the unlikely event no parent can be located, the police should be called.

We strongly recommend these suggestions be covered by written policies and procedures.