E

Electronic Article Surveillance (EAS)

“Electronic article surveillance” (EAS) is the tem used to describe retail antishoplifting protection systems for apparel and packaged consumer products. These systems have been successfully implemented in hundreds of thousands of stores worldwide over the past 40 years. In short, an electronically detectable element (tag/label) is either pinned or affixed via adhesive to the item to be protected. Transmitters and receivers are placed at store exits to detect the presence of the tags as shoppers leave the stores. At the point of purchase, these tags are either removed or rendered inoperative so that the customer may exit the premises without setting off an alarm. If someone were to attempt to leave the store with items containing “live” electronic elements, the detection equipment at the exit would sound an alarm, and store management could take appropriate action.

These systems have proven to be an effective psychological and physical deterrent to shoplifting. In recent years, technological improvements have provided more reliable, smaller, and less expensive products.

The apparel industry was among the first markets for EAS. The primary method of protecting clothing was (and still is) the application of reusable plastic tags at the store or somewhere in the distribution chain. The original tags were large, heavy (27 grams), and costly ($1.40 each), and were pinned to the garments by store personnel as the merchandise was placed out on the sales floor. Even though they were obtrusive and could damage apparel if misapplied, these tags were tolerated because they effectively thwarted shoplifters and reduced inventory losses.

Over the years, the size, shape, and weight of the tags have been steadily reduced. At present, the lightest tag weighs about 7 grams, and the least expensive tag can be purchased in large quantities for about $0.15.

In the past 20 years, thin, label-like electronic circuits have been designed to provide a similar deterrent against the theft of packaged products, such as health and beauty aids, cosmetics, hardware items, toys, electronic media, and other high-volume, high-risk items. The basic principles of use remain the same as with plastic tags, except that the labels are not generally removed at the point of purchase; they are electronically disabled (deactivated) so that they won’t activate an alarm as a customer exits the stores. These labels can be mass-produced at high volume for a fraction of the cost of plastic EAS tags. In addition, they can be applied to merchandise packaging using high-speed automated equipment and deactivated with little or no disruption to the checkout process.

Terminology

EAS industry jargon is not necessarily standardized. Following are definitions of major terms:

• EAS system: A pair of detection pedestals, or a single transceiver that transmits and receives the basic electronic signals. At certain times, the word “system” may be used to describe all the components of EAS in a store, not just the electronic detection equipment.

• Tags: The generic term used for individual EAS circuits of any technology. In some contexts “tag” refers to either a reusable or disposable product. Here, the term is used specifically to describe reusable plastic products, used for protecting apparel, containing an EAS circuit, a pin, and a locking mechanism. It will also be used to describe benefit denial products, such as ink tags.

• Labels: The specific term used to describe disposable paper/plastic laminated products, used on packaging, containing an EAS circuit and adhesive.

• Detacher: A removal device used for reusable plastic tags and benefit denial devices.

• Deactivator: A device used to destroy or distort the EAS circuit in a disposable EAS label.

• Circuit: The generic term used to describe the “working” component of an EAS tag or label.

• Source tagging: The generic term adopted by the industry to describe the affixation of disposable EAS labels onto merchandise at a convenient point in the manufacturing process, rather than after it reaches the retail store.

• Tag and label geometry: The term used to describe the basic shape and dimensions, or footprint, of a disposable label or the circuitry enclosed in a plastic tag.

• Contact and proximity deactivation: Contact deactivation is the act of incapacitating a label as it is touched by magnetic material—eliminating the circuit’s ability to respond with a recognizable signal. Proximity deactivation is the act of incapacitating a label at a distance—without directly touching the circuit.

Basic Technology Comparison

Worldwide, there are three EAS technologies with a significant share of the market: electromagnetic (EM), radio frequency (RF), and acousto-magnetic (AM). Each is capable of supporting conventional EAS usage, where tags or labels are affixed at the retail store, or source tagging. Additionally, retailers have chosen to include benefit denial devices, such as ink tags, as an adjunct to EAS programs. Since benefit denial products are an important segment in the North American market, basic information about the technology is included under the heading “Benefit Denial Devices” later in this section.

All types of EAS systems operate from a simple principle: A transmitter sends a signal at a defined frequency to a receiver. This establishes a surveillance field. When an EAS tag or label enters the field, it creates an electronic disturbance that is detected by the receiver. By design, each EAS technology has its own method by which the tag disrupts the signal. Each of the three major technologies occupies a particular space on the frequency spectrum and has its own set of strengths and weaknesses imposed on it by the laws of physics. While they may be similar in appearance and function, and provide the same general benefits, the technologies could hardly be more different.

The electro-magnetic (EM) transmitter creates a low-frequency (between 70 Hz and 1 kHz) electro-magnetic field between the two pedestals. Hertz (Hz) is a measurement of wave cycles per second, and 1 kilohertz is 1,000 cycles per second. The field continuously varies in strength and polarity, repeating a cycle from positive to negative and back to positive again. With each half cycle, the alignment of the magnetic field between the pedestals changes. EM EAS “circuits” are made of a strip of wire cut to a specific length. When the circuit enters the magnetic field created by the transmitter, its magnetic characteristics are changed, and the wire generates a momentary signal that is rich in the harmonics of the base frequency. In layman’s terms, a harmonic signal is a precise integral multiple of the base signal from the transmitter. The receiver detects the harmonic signal, and an alarm is sounded. Unfortunately, the circuit’s signal strength is so weak that the pedestal width restrictions are a maximum of 36 inches. The narrower the pedestal width, the better the receiver can “hear” the harmonic transmission from the tag. A transceiver (combination transmitter and receiver) is available, but effective detection is limited to about 24 inches. Label deactivation is achieved by magnetizing segments of the wire.

For radio frequency (RF) systems, the transmitter sends a signal that sweeps back and forth between certain frequency ranges. Currently, the most popular center frequency is 8.2 MHz, with a sweep range of between 7.4 and 8.8 MHz (megahertz = millions of cycles per second). A swept transmit signal is required because tight frequency tolerances cannot be precisely controlled during high-speed manufacturing of disposable EAS labels. The transmit signal energizes the EAS label, which is composed of an etched aluminum circuit containing a capacitor and an inductor, both of which store electrical energy. The EAS circuit in a plastic tag is composed of a tuned coil of wires and a capacitor. When connected together in a loop, the capacitor and etched circuit (or coil) can pass energy back and forth, or resonate. Matching the storage capacity of the two components controls the resonant frequency. The target center frequency, which is at the midpoint of the sweep, is 8.2 MHz. The circuit responds by emitting a signal that is detected by a wideband receiver, meaning a receiver that monitors for signals over a wide frequency range. The wideband receiver is required because of the lack of precision in the mass manufacturing of EAS labels. It is useful to think of this wideband receiver as fishing net carried by a shrimp boat (very large). These nets catch much more than just shrimp. Similarly, a wide band receiver picks up more than just the tag signal. The strength of the RF transmission from the circuit depends on the aperture of the loop (diameter). The larger the loop diameter, the wider apart the pedestal can be mounted. Reusable plastic EAS tags may have a loop diameter of as much as 3 inches—allowing adequate detection at almost 2 meters. The standard label size is about 2 inches square, limiting the practical detection distance to about 4 feet or under. A few of the RF EAS manufacturers have introduced a transceiver that can be mounted either as a pedestal or underneath flooring, but detection is limited to about 3 feet.

To support deactivation in disposable RF EAS labels, a dimple is added to the etched capacitor. The purpose of the dimple is to encourage a short circuit, which is caused by a strong burst of a signal of the same frequency used in detection. This burst causes an arc, which completes the short circuit. Permanent circuits in plastic tags cannot be deactivated. Deactivation can be achieved at a maximum distance of around 12 inches from the circuit.

RF reusable plastic tags are also available with a transponder, instead of the conventional tuned coil. A transponder is made up of a ferrite rod antenna for reception/transmission and a capacitor—forming a resonant circuit. Thin wire is wound around the ferrite. These products can be detected by AM transmitters/receivers, but the performance characteristics differ from those exhibited by acousto-magnetic material.

The acousto-magnetic (AM) technology, offered exclusively until 2003 by ADT (trade name is Ultra*Max®), contains a transmitter which sends a signal at a frequency of 58 kHz, but the frequency is sent in pulses. The signal energizes the circuit, and when the transmission ends, the circuit responds, emitting a single frequency signal like a tuning fork. The circuit’s transmission is at the same frequency as the system’s transmission, not a harmonic like the EM system. While the system’s transmitter is “off” between pulses, a narrow band receiver detects the circuit’s signal. A narrow band receiver can be used because the AM tag frequency tolerance is just 600 Hz. Compare this with the 1,400,000 Hz tolerance required with swept RF. In the fishing analogy used earlier, a narrow band receiver would be akin to a handheld casting net. Very little other than the target fish will be caught.

AM technology supports both a reusable plastic tag and a disposable, deactivatable label. The “circuit” is a strip of precision-cut amorphous alloy metal called METGLAS®, with exceptional magnetic properties and a noncrystalline structure—like glass. When aligned atop a magnet, the METGLAS® vibrates when it is exposed to the transmit signal. Since the signal is pulsed, when the transmit signal stops, the METGLAS® continues to vibrate. The accurate frequency response of the tags and labels results from the precision cutting of each strip. This “acousto-magnetic” effect, where resonance and magnetism create a unique signal, helps to explain why AM technology is somewhat immune to false alarms from objects that imitate similar electronic characteristics.

AM reusable plastic tags are available with a transponder, instead of acousto-magnetic material. A transponder is made up of a ferrite rod antenna for reception/transmission and a capacitor—forming a resonant circuit. Thin wire is wound around the ferrite. These products can be detected by AM transmitter/receivers, but the performance characteristics differ from those exhibited by acousto-magnetic material.

Apart from the physics involved, label geometry plays an important part in the detection and deactivation performance of AM tag/label circuits. A clearly defined cavity is required to guarantee that the resonance can take place when the circuits receive the signal from the transmitter. AM disposable labels must contain enough of a height dimension to ensure vibration.

In addition to the METGLAS®, AM disposable labels contain a bias magnet which is made from material similar to razor blades. The AM deactivation process actually increases the intensity of the bias magnet, thereby attracting the METGLAS® and inhibiting it from resonating. This effectively deactivates AM disposable labels. The labels can be deactivated by touch on a pad containing magnetic material (similar to deactivation in EM systems) or by using an electro-magnet intensify the magnetic properties of the metal bias strip inside. The requirement for magnetic field changes creates some issues at the point-of-sale. For example, the deactivators can erase information on bank and credit cards.

EAS Source Tagging

Starting in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Sensormatic/ADT and Checkpoint began working in partnership with retailers, consumer product manufacturers, and packaging experts to develop automated, integrated systems to affix disposable EAS labels somewhere toward the beginning of the product manufacturing process—either by a distributor, packaging provider, or the manufacturer itself. The key perceived benefit to the retailer was to transfer the cost of EAS label procurement and the merchandise tagging itself to a “source” in the manufacturing process where the process could be accomplished most cost effectively. The EAS companies saw source tagging as a “razor and blade” strategy, with the EAS system as the “razor” and the labels as the “blades”—eventually generating endless recurring revenue from label sales. Both companies began marketing source tagging to the largest retail chains in North America, reasoning that once a few nationally recognized retailers adopted the strategy, others could easily follow.

The EAS market is neatly divided into two major subsets according to merchandise type: packaged products (commonly referred to as “hardlines”) and apparel. In the developmental stages of source tagging, most of the effort was directed toward hardlines because both EAS manufacturers had developed reasonably inexpensive disposable labels that could be integrated into the packaging process fairly easily. Historically, reusable plastic EAS tags that aren’t suitable for source tagging have protected apparel. Efforts to develop security products for apparel that would be suitable for source tagging started in the mid 1990s.

EAS executives had three main objectives in the early marketing of source tagging. First, they had to convince retailers that source tagging was the most effective method of implementing an EAS program. They used a two-pronged approach: the elimination of tagging labor and the prospect of lower shortage and incremental sales as items were preserved from theft and sold instead of stolen. If retailers accepted that logic, then it would be easier for retailers to install EAS detection equipment in all stores (a prerequisite to source tagging). Second, they had to get the retailers to use their influence over merchandise manufacturers to get them to accept the burden of label procurement and placement. This turned out to be a difficult task and gave rise to the Consumer Products Manufacturers Association’s efforts to forestall source tagging. Simultaneously, the EAS companies lobbied merchandise manufacturers to embrace source tagging as a customer service. They argued that accepting the task of source tagging would eventually result in more shelf space, or a wider assortment. Third, the EAS companies established in-house organizations whose purpose was to facilitate the actual process of source tagging among the partners. Resources were devoted to establishing standards; assisting in the design, development, and procurement of high-speed tagging equipment; entering into licensing arrangements with packagers and purveyors of specialty security equipment; and providing other necessary assistance to both retailers and manufacturers. In addition to in-house source tagging management, both EAS manufacturers have funded and supported trade association groups that function to promote source tagging and educate retailers, manufacturers, packagers, and other interested parties. The Sensormatic/ADT-sponsored organization is called the Source Tagging Council, and the Checkpoint-sponsored organization is called the RF Inventory Management Conference. Each of these organizations schedules user group meetings where all pertinent source tagging issues are discussed.

Early Successes

Both Sensormatic/ADT and Checkpoint had early success in convincing a “marquee” retailer to implement a source tagging program. Sensormatic’s classic case study is The Home Depot, U.S.A., and Checkpoint’s is Eckerd Corporation. Both embarked on source tagging programs at approximately the same time—1993. Home Depot’s source tagging program is the model on which most other AM programs have been built. Home Depot probably has more source tagging experience than any retailer in the world. The chain installed EAS for the first time with the proviso that absolutely no tagging would take place inside Home Depot stores. Any and all tagging had to be achieved somewhere in the manufacturing or distribution chain. Home Depot accomplished its goals by establishing a three-phase program. The first phase consisted of the topical application of EAS labels to the outside of packaging. The second phase mandated that the labels be concealed within the packaging. And the third phase suggested (rather than mandated) that EAS labels be incorporated within the merchandise itself, not just the packaging. Currently, Home Depot has converted the vast majority of vendors to phase two tagging, which has become a de facto standard.

At the outset, Home Depot started the program by isolating stock keeping units (SKUs) that incurred high shortages. Targeting SKUs was one of the most practical methods to justify source tagging because isolated shortage statistics could be shown to the manufacturer. Home Depot was saying, “Look at our shortage statistics for your power tool. We’re losing money and we want you to help both of us make more money by applying the EAS label for us.” As time passed, however, Home Depot realized that focusing on the SKU was an inefficient method of source tagging. In the first place, shoplifters tended to stop stealing the source tagged item, but they began stealing similar products made by vendors that were not yet source tagging. Home Depot management saw this trend reflected in its inventory shortage statistics. Second, Home Depot routinely adds and drops vendors and SKUs, so isolating high-shortage items became more difficult—particularly for seasonal or promotional merchandise.

Recently, Home Depot has broadened its perspective by source tagging by merchandise category. In other words, when management discovers that a particular type of merchandise has become a target for shoplifters, it endeavors to have all like merchandise source tagged—not just the SKUs with high shortage. This shift in philosophy has provided Home Depot with several benefits. First, category source tagging management is easier to administer than SKU or vendor management. Second, broadening the tagging guidelines to include all “at risk” items serves as insurance against high inventory shortage. For example, thieves learn that every power tool is tagged, not just a specific brand. This prevents a low-shortage item from becoming a high-shortage item in the future.

Eckerd Corporation was the drugstore division of J.C. Penney. It was sold to CVS and the Jean Coutu Group in 2004. At the time its source tagging program was started, however, it was an independent public corporation. Under Checkpoint’s guidance, Eckerd established most of the same management parameters that were used in Home Depot. There are two concepts for which Eckerd is most noted. It was the first chain to assign a merchandising executive the responsibility of managing the source tagging efforts for the entire chain. This was, and continues to be, a key aspect of a successful program. The manager is able to serve the interests of parties—the Eckerd buyer responsible for the merchandise, the merchandise manufacturer, and the loss prevention department. It has been a vital benefit to the smooth operation of the program. The second concept is called “fractional tagging.” In cases where the EAS label is concealed under the product packaging, Eckerd’s allows manufacturers to source tag a preset fraction of the merchandise, say 33%. Since the security label is concealed within the packaging, it is logical to infer that shoplifters would not know which items are protected, and the deterrent qualities of the system will remain intact. In practice, fractional tagging has worked well and has helped lower the per-unit cost of the merchandise.

The Economics of Source Tagging

Since the mid-1990s, retailers have been assessing the value of an investment in EAS based on a classical cost versus benefit analysis. Will the reduction in inventory shortage offset the costs? As the EAS industry has matured, improved product offerings have broadened the scope of the asset protection role and changed the basic business model. Originally, a retailer’s economic decision with respect to EAS was (a) to invest or not and (b) choose a technology. An EAS program was strictly an internal decision, requiring no outside help from others—except the EAS vendor. Circumstances have now changed. Many retailers are now long-term users of EAS, and technological advancements are forcing conversions from old to new systems.

Additionally, the recent emphasis on source tagging has created an “open system” requirement that was unnecessary in the past. “Open systems,” in this context, means the collaboration among EAS provider, retailer, and merchandise manufacturer to work in harmony to ensure the success of the program. Retailers desiring to start a source tagging program must embrace a “wholesale adoption” mindset for the EAS program. EAS should be installed in all stores at the outset. Excess profit contributions from the high-volume, high-theft stores should be used to subsidize the smaller, less-theft-prone units, so the entire chain enjoys the economic benefits of source tagging: the elimination of tagging labor costs, the assimilation of tagging cost out of expense and into the cost of goods, and incremental sales from the role of EAS as a capable guardian of the merchandise assortment.

These developments have altered the risk-to-reward equation and complicated the EAS business model and the cost-justification process. Perhaps the most drastic alteration is that merchandise manufacturers are now, in a sense, EAS users in that they buy tags directly from EAS vendors and apply them to merchandise for retailers. Going forward, a much wider array of business issues must be addressed by groups other than the retailer. The more obvious issues are

• Can a new technology replacement EAS system be cost justified?

• Due to the requirements of source tagging, can EAS be cost justified in all stores, regardless of need (as defined by unacceptable shortage levels)?

• What are the economic issues facing merchandise manufacturers? Can they be quantified, and do the benefits outweigh the costs?

• How does the merchandise manufacturer’s source tagging business model impact the wholesale cost of the merchandise?

These complexities are forcing all participants to revisit the issues surrounding ROI calculations. The simple arithmetic of “payback” undertaken in years past isn’t sophisticated enough to provide the proper economic answer. Several major financial issues must be fully understood to obtain a full understanding of source tagging:

• EAS is difficult to cost justify for all locations at current pricing structures. The vast majority of EAS users apply the technology of their choice to high-theft items in stores exhibiting an inventory shortage crisis. They obtain a return on capital investment on a store-by-store basis. As a rule, they do not freely spend the money on EAS if the pro forma ROI calculations in an individual branch store don’t justify the expenditure. The Home Depot case in which EAS was installed chainwide at the inception of the program was clearly an exception. Few other North American retailers have been as innovative. For source tagging to be universally recognized as the appropriate platform for EAS, the store-by-store mindset must be changed.

• Individual equipment procurements are depreciated for up to 10 years. New purchases are added regularly, increasing the equipment replacement time horizon. The useful life of EAS equipment generally exceeds its “accounting” life. After the depreciation schedule ends, continued EAS protection is essentially “free.” This inhibits technology conversions. In fact, The May Department Stores Company has successfully slowed its conversion from MW to AM.

• North American retailers generally favor operating a single technology in “user” stores. It is too costly to manage competing systems. Consequently, EAS tag and label procurement and the concomitant tagging labor costs are generally the retailer’s highest variable costs associated with an ongoing (non-source-tagged) EAS program. In high tagging volume situations, or in areas with high wage rates, these costs significantly dampen the ROI. From the perspective of the retailer, source tagging provides the opportunity to transfer these costs directly to the merchandise manufacturer. The absorption of source tagging costs creates a new set of inventory management problems for merchandise manufacturers. They must now procure EAS labels, redesign the manufacturing process to absorb the tagging process, and perhaps procure capital equipment for high-speed, automated tagging. The most onerous problem, however, is in the segregation of tagged versus untagged inventory. When a merchandise manufacturer commits to source tagging, three subsets of a single SKU must be managed: untagged, RF tagged, and AM tagged. The magnitude of these costs, and the lack of a clearcut way to recover them, has been the single biggest stumbling block in gaining manufacturers’ support for source tagging.

Benefit Denial Devices

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, as the first-generation electronic article surveillance products matured, they began to lose their effectiveness, and losses from shoplifting began to rise precipitously. At the time, retailers were beginning to realize that the existing EAS technologies weren’t deterring as many thieves as they had previously. The rewards of successful theft had begun to exceed the risk of detection from the EAS alarm. Retail loss prevention executives began searching for better solutions, and they were willing to try something more radical. Thanks to two enterprising and visionary security equipment manufacturers—Colour Tag of Sweden and Security Tag Systems, Inc., of the United States—the concept of “benefit denial” was born and commercialized.

Thieves routinely steal personal property or retail merchandise either for personal use or to sell the items for cash. The radical idea behind benefit denial is to provide physical protection that would destroy an item instead of allowing thieves to obtain any economic benefit from it. Dr. Read Hayes, the well-known retail security consultant, coined the term “benefit denial” in early 1993, and it has become the universally accepted name for a growing category of security products used in retail and nonretail item-level protection.

There are a few noteworthy examples of benefit denial devices in society at large that explain the concept and that acted as catalysts for the products developed for use in retail.

• Exploding dye packs used by banks to identify stolen currency. Robbers who attempt to spend the currency can be readily identified.

• Clothes hangers in many hotel room closets have closed loops and ball joints that allow separation between the loop and the hanger, so the entire unit cannot be stolen and used in any conventional closet.

• “Breakaway” electronic switch connectors that disable car radio/CD players if they are removed from the dashboard of the vehicle.

• Car security systems that disable a vehicle’s electronic fuel pump a few seconds after a theft attempt.

History

The benefit denial phenomenon in retail loss prevention began in the late 1980s when Colour Tag’s original system was introduced at a trade show in Europe. Spawned by the bank dye packs, Colour Tag developed a “dye pack” to protect apparel from thieves. The original tags were heavy, large, and expensive (about $6 each). While this design set the current industry standard by using pharmaceutical-grade glass vials, the dye was toxic and the vials were filled under pressure. The tags were rugged and were able to withstand the rigors of repeated use within retail stores. Unfortunately, they were too well engineered and were difficult to break with force, but easy to defeat with common implements, such as a paper clip. When the tags did break, however, the garments were indeed ruined, as the vials tended to explode. As with conventional EAS tags, Colour Tags were removed at the point of sale. The “remover” was a portable air compressor that usurped precious space at the checkout stand, required a dedicated electric outlet, and cost $800.

Notwithstanding the safety, liability, and operational issues surrounding the product, and the general lack of understanding of the deterrence concept behind the idea, Color Tag successfully marketed the products in several European countries, and a few visionary American retailers conducted small-scale trials.

Security Tag was a small manufacturer of EAS and access control products. In 1989, its founder returned from a European trade show with samples of the Color Tag and commissioned a more user-friendly design. To succeed, Security Tag management had two tasks. First, the original products were unsuitable for the American retail market place and had to be redesigned. Engineers had to devise a product that was cost effective, easy to affix and remove, would withstand the rigors of apparel retailing without accidental breakage, did not exhibit the safety and liability issues evident in the Color Tag product, and still damaged apparel during tampering. Equally as importantly, Security Tag’s marketing organization had to develop a working definition of the deterrent qualities of benefit denial products and full descriptions of the relevant features, functions, and benefits.

Through these efforts, the terms “ink tag,” “inkmate,” and “benefit denial device” became part of the retail loss prevention lexicon. The first benefit denial product, Inktag I, was introduced in the summer of 1991. Over the next 3 years, Security Tag introduced second- and third-generation ink tags and products designed to mate with EAS tags. The company also applied the benefit denial principles to make products to protect other retail merchandise, such as jewelry, neckties, and leather products. The program became so successful that by the time it was acquired by Sensormatic in 1993, Security Tag had set the industry standards and become the world’s largest producer and seller of benefit denial devices.

By the late 1990s, several other companies began to either develop new benefit denial concepts or copy existing ones. These products are made and sold by at least six different security equipment providers, including ADT/Sensormatic, Checkpoint Systems, Inc., EAS SensorSense, Unisen, and Universal Surveillance Systems, among others.

Over time, the ink tag, and its derivatives, has become a popular and effective anti-shoplifting countermeasure. According to a 2004 study of EAS market penetration conducted regularly by a well-known security equipment manufacturer, among the top 25 department store chains in North America, over 68% of the branch stores use benefit denial devices in some form, but only 48% of the stores use EAS (all technologies). By this measure, benefit denial products have penetrated more department stores locations in 15 years than EAS has penetrated in 40 years.

Ink Tags

The original retail security version of a benefit denial product was designed as a two-piece reusable plastic tag without an EAS circuit. One side contains the locking mechanism. The other side contains the pin and one or more glass vials containing a nontoxic, nonflammable dye or stain. The best-designed products also include an internal breakage mechanism that aids in the breakage of the vials and a diffusion pad that disperses the ink onto the fabric after the vials break. This product was originally designed to deter shoplifters in stores without EAS and is known as a “standalone” ink tag. Typically, the tag has a warning label printed on one side.

Combination Ink/EAS Tags

The most popular benefit denial product for apparel is known as an “inkmate.” It is a one-piece reusable plastic tag that contains the pin an done or more glass vials containing a nontoxic, nonflammable dye or stain. The more effective products also contain an internal breakage mechanism and a diffusion pad that aids in the dispersal of ink on the fabric. These products are substitutes for EAS pins and are “mated” with reusable EAS tags to form a double deterrent. They are much more popular than conventional standalone ink tags because of their compatibility with EAS systems.

Loss prevention executives soon realized that the combination of EAS and benefit denial forced the thief to “do something” with the tag inside the store or run the risk, however insignificant, that the alarm would cause a problem as he left the store. This turned out to be a very powerful deterrent. The inclusion of inkmates added longevity to inferior and first-generation EAS technology. In fact, the success of the inkmate caused at least one major U.S. department store retailer to delay a conversion to second-generation EAS technology—a strategy that is employed to this day.

What began as a case of “field expedience” turned into a lasting legacy of benefit denial for apparel retailers. The combination of an EAS tag mated with ink provided a device that offered the physical security of a clamp, the threat of an EAS alarm, and the certainty that tampering with the tag would ruin the merchandise. The EAS/ink combination remains a “capable guardian” of apparel.

Specialty Tags, Clamps, and Harnesses

Specialty benefit denial tags (not necessarily containing ink vials) have been designed using a variety of methods to protect other categories of merchandise. A small, magnetic release “padlock” was designed to protect jewelry, lingerie, and eyewear. Other lock and clamp arrangements protect accessories and various types of sporting goods.

A stainless steel clip was designed to protect neckwear, lingerie, and scarves. This device, shaped like a man’s tie clasp, clamped onto a portion of a necktie and was held in place by a plastic locking mechanism. A similar device shaped like a money clip was made from specially bent stainless steel. A special hand tool, shaped like a pair of pliers, was required to both affix and remove the tag. It protected small leather goods.

At least two manufacturers provide wire harnesses that are wrapped around consumer packaging to prevent thieves from taking the product from the package. These products can be either EAS or non-EAS inclusive. They have gained a measure of popularity in the small electronics merchandise category. At least two manufacturers offer a benefit denial device that clamps CDs, DVDs, game software, and other media products to their primary packaging.

In an effort to emulate the switches employed by the auto industry to deter auto theft, a patent has been issued on an electronic device that disables video game players that were not properly deactivated at the point-of-sale.

DiLonardo, R.L. (1993). Fluid tag deterrents. Retail Business Review. June.

DiLonardo, R.L. (1997). Source tagging issues and answers.

DiLonardo R.L. The economics of EAS. Loss Prevention Magazine. 2003;November-December:21–26.

DiLonardo R.L., Clarke R.V. Reducing the rewards of shoplifting: An analysis of ink tags. Security Journal. 1996;7:11–14.

Embezzlement: 17 Rules to Prevent Losses

1. Never hire an applicant unless his background has been verified.

2. Know your employees to the extent that you may be able to detect signs of financial or other personal problems.

7. Inspect all canceled checks.

9. Audit your financial transactions.

10. Control special and exceptional financial transactions.

11. Control all disbursements.

15. Control blank checks and any other negotiable instruments.

16. Periodically “SALT” cash registers and cash bags to see whether overages are reported.

17. To check your controls and checks and balances, purposely introduce “errors” into the system to see if, when, and by whom they are reported.

Emergency Planning for Retail Businesses

Background

Emergency planning for retail businesses is essentially the same as it is for any other kind of business. To be sure, the retail trade has its own jargon and terminology; however, the basic principles of emergency planning apply regardless of the type of business. Even though there are hundreds of different types of retail businesses from large department stores to kiosks and push carts, the planning principles remain the same.

Why plan for emergencies? This short anecdote will give an answer to the question. The former country director (vice president) of a large international corporation told me this story. War was looming. The country he was in was a target of the forces planning an invasion. The lease for the corporation’s main manufacturing facility was up for renewal. The company planned to have a meeting of its governing board to approve the renewal of the lease. In the meantime, the country was invaded. Although no damage was done to the company’s facilities, the international borders of the country were closed. Therefore, the outside directors from a variety of countries covered by this international corporation were unable to travel to this country to have a meeting. Thus, the lease was never approved. It soon expired. The result: The large international corporation had to close down its operations in that country until the international borders were reopened 4 years later. What went wrong? The answer is something very simple. There was no plan existing that would have allowed the local country management to approve the renewal of the lease under emergency conditions and for the duration of the closing of the international borders. These same conditions could apply to a retail store chain which had its main storage and distribution center in a country which had to close its international borders because of a belligerent situation; no goods in, no goods out, no one authorized to take action to ameliorate the situation, no governing board to approve or disapprove an action.

Keep It Simple, Stupid

The most important thing I believe I have learned from emergency planning experience is to keep things simple. You cannot imagine the failures I have seen because plans were too complex for retail security managers to carry out and even more complex for line and store managers to carry out. I have seen emergency plans 2 inches thick gather dust on store managers’ office shelves because the plans were too complex to be carried out expeditiously. Because of their complexity, emergency plans became obsolete, as the difficulty of keeping them updated and current was just too great to be practicable. When plans are not read or implemented under emergency conditions, things always go wrong. There is a generally-accepted principle in business called KISS, which basically stands for KEEP IT SIMPLE, STUPID. There is a saying in the Navy, “Ships are designed and built by geniuses to be operated by idiots.” Although that is an exaggeration, the key element is obvious. The other side of the coin tells us if a plan is too complex and impracticable, it is folly to expect it to be carried out efficiently if at all. Therefore, what follows applies the KISS principle throughout. You can take these simple suggestions and apply them to any kind of retail business.

The Basic Emergency Plan

The basic reason for creating emergency plans in retail businesses is to keep enterprises functioning even under extreme emergency conditions. Management has to be able to shift from normal, day-to-day operations to an extraordinarily stressful environment while keeping the enterprise running with reduced resources in communications, transportation, manpower, and funds. If the company is national or international, the emergency conditions create additional burdens in operating on a 24-hour basis across multiple time zones. A basic plan can be created that will be tailored to the size and complexity of the organization. A “mom-and-pop” store will have a very thin plan; an international store chain will have a thicker plan, but everyone must resist the temptation to make the plan more complicated just because it is longer. What follows is the outline of a basic plan that can be used to shift to emergency, sustained operations by any size company.

Outline of a Plan

The following outline can be useful to help publish an emergency plan in the corporation as a General or Special Instruction or their equivalents applying to every element of the enterprise. There should be separate, simple sections covering every principle of emergency operations that can be reasonably anticipated.

Purposes of the Plan. Purposes of an emergency plan are to provide a means of transition from normal to emergency operations efficiently, to delegate emergency authority, to assign emergency responsibilities, to assure continuity of operations, and to provide authorizations for actions contained in the plan.

Execution Instructions. The board of directors or its equivalent delegates authority to execute the plan as an operations instruction. Logically, this can be done in the following order: chief executive officer (CEO), officers who report directly to the CEO, local managers, and senior managers of branches of the enterprise. The plan may be executed partially under these conditions: bomb threat, kidnapping or hostage taking, severe weather, or flood. The plan may be executed fully under these conditions: civil disturbance, major riot, insurrection, explosion or major fire in corporate facilities, severe earthquake causing major structural damage to a corporate facility (store, warehouse, distribution center, office building, etc.).

Command and Control. The principal center for command and control is the corporate office. If the enterprise is a group of stores, then the alternate principal center should be the nearest branch office, or, in case there are no branch offices, the nearest store to the emergency condition that is not directly affected by the emergency directly. The controlling person should be the one nearest to the emergency; i.e., a person who can easily travel to the scene of the emergency, take control, and render reports to the corporate office of the conditions observed and actions taken. Corporate board resolutions must be in place at all times to give the person on the spot the authority to implement the plan and carry on actions to benefit the corporation. Only the chief executive officer of the enterprise should be allowed to countermand instructions to persons in the emergency area who are under the command and control of the enterprise’s local authority. The chain of command must be absolutely clear: Regardless of his corporate rank, the local person in charge of the emergency area has absolute authority to carry out actions beneficial to the enterprise in accordance with general policies of the enterprise. He is supervised by the chief executive officer (or in some organizations, the chief operating officer), who can countermand orders only when they are clearly not beneficial to the operation of the enterprise in the local emergency area, which could be anything from a single store to many stores, warehouses, and distribution centers. The chief executive officer assures that there is an emergency operations line item in the budget of the enterprise. The line item should take into account security, emergency planning, training, and special funds for operating under emergency conditions. The local person in charge coordinates with local fire, police, and other emergency agencies; informs persons in the emergency area of their various roles according to the plan; and disseminates applicable portions of the plan. Corporate and district managers should have already conducted training, rehearsals, and reviews of insurance against potential loss or obligations resulting from destructive events. Such actions should be started as soon as the corporate office has promulgated the plan. Every person who might be in a managerial or supervisory role in carrying out the emergency plan must have at least one backup person—two are better—trained to be backup(s) and emergency replacement(s).

Continuity of Management. The local manager of the emergency area shall determine which units of the enterprise in the area shall remain functioning. Some criteria for such a decision are availability of local public utilities at the site(s)—e.g., water, sewer, fire suppression, electricity; damage to structures, conditions in streets, availability of emergency medical assistance; morale and welfare of employees; etc.

Coordination and Liaison When the Plan Is Fully Implemented. The local person in charge is responsible for coordinating with local, state, and federal officials. To help with security and around-the-clock operations, it is advisable to keep a list of reliable private security agencies in the areas where the enterprise has facilities. At least one private security agency should be on retainer to help out in emergencies. A private security service can take on the task of coordinating with fire, police, and other emergency services. The person in charge should designate a company employee to be responsible for coordination with adjacent or nearby firms and facilities suppliers. One person only should be authorized to coordinate relations with news media.

Communications. You should expect breakdowns in communication systems for hours, days, or weeks. Alternate communication measures should be arranged before an emergency. If land-line telephone systems go down, you can substitute voice messages and email sent by computer through cell phone towers or satellites. Citizen band or other public band radios can be used locally. It may be necessary to employ messengers, employees, or professional messenger services to travel to the nearest operating communications areas to communicate with corporate offices. One employee per day can be designated to hand-carry important and urgent messages by automobile or airplane.

Personnel. Local and regional managers should maintain an informal list of the secondary skills of employees within their normal areas of responsibility. The secondary skills may become very useful in case of emergencies. For example, a stock clerk may be an emergency response medical specialist off-duty and can apply those skills to help injured fellow employees when necessary and when no other medical support is available. Local and regional managers should conduct periodic training, internally or by contract, to ensure minimum skills are available to operate under emergency conditions. No one knows when, where, or what kind of emergency may occur; therefore, at least rudimentary lists should be kept at the local and regional level of notification procedures, reporting points, and transportation resources. These lists should be kept simple and up-to-date. There should be procedures in place to brief other employees of the daily situation when under emergency conditions. There should be a procedure for notifying employees of evacuation routes in case it is deemed impossible to continue operations in a certain location or area. It should also be expected that when a major natural disaster strikes, most, if not all, employees will feel compelled to give their first priority to the safety of their families and not to the mission of the enterprise.

Utilities. Every corporate facility should have at least one standby generator in expectation of failure of the public electrical power system. Large facilities can use generators powered by natural gas that come on automatically when electrical power fails. Alternatively, there can be a permanent standby diesel-powered generator at large facilities. Small facilities should have small standby generators and an ample supply of fuel for generators to last for several days of operation. Battery-powered lighting such as emergency lights and flashlights should be available for emergencies. Flashlights powered by induction (shaking) can have a long shelf life and are handy in emergencies. Candles should never be used when the water utility has failed. To prepare for failure of the public water supply, 5-gallon containers of water can be kept on hand and be exchanged periodically to keep them fresh. Such emergency water sources can be used also to flush toilets.

Security. As discussed earlier, private commercial security forces that have been retained on a standby basis should be procured on an active contract basis by corporate elements when conditions warrant it. Security forces on a standby, as-needed basis should be invited to participate in all rehearsals of the security plans. Keep in mind that private security forces will be going through almost the same personnel crisis as the employees of the enterprise in the emergency area. If and when security forces are contracted, they should be put under the command and control of the person in charge of the area where the emergency conditions exist. Depending on the nature of the emergency, simple, letter-sized plans can be drawn up in advance to help coordinate the enterprise’s employees with the security augmentation. A contract guard agency can assist in the preparation of such plans. In large corporations, there may be a professional security manager who can assist lower elements in preparing such plans. These letter plans become operational directives when an emergency condition is in being. The person in charge of the emergency area may designate a corporate employee to assist him in the following: establishing liaison with local law authorities and reporting to police all actual or suspected acts of espionage, sabotage, or terrorism. Establish alternate record storage sites for all corporate elements. Screen all applicants requesting employment for possible security risks. Brief all new employees on general security procedures and security consciousness.

Fire Prevention. All new employees should be briefed by their supervisors on techniques of and the need for fire prevention. Designate a fire marshal in every enterprise facility no matter how small. The fire marshal should be made responsible for fire detection and suppression. Detectors that recognize the various traits of fires should be installed in all enterprise facilities, especially rooms that are normally not occupied during normal business hours, such as cooking areas, photocopy rooms, conference rooms, visitors’ offices, etc. Post fire extinguishers in conspicuous places and have fire extinguishers checked and filled by an outside contractor at least once a year or as often as local ordinances require. Store copies of electronic and paper records critical to operations, large amounts of cash and securities, and insurance policies in fire-resistant containers with the longest fire rating period available. The best place to store such materials is at an off site location.

Here is another anecdote to illustrate the importance of offsite locations. The place is a factory in a foreign country. The security consultant recommended the company make backup copies at least once daily of all computer records. The factory was later expanded and modernized. A contractor accidentally started a fire. The fire destroyed the central computer system and the manager’s office. Instead of using an offsite storage facility, the manager had kept the backup copies of the computer records in his office. All records, originals and backups, were destroyed. The company moved its offices to an adjacent site. To restore its records, the company had to depend on records kept by its customers, clients, and suppliers to determine its accounts payable and receivable. Tax records helped to fill in the gaps in data.

Emergency Supplies. In addition to items previously listed, designate persons to be responsible at each enterprise facility for procurement and caring for an industrial-type medical supply and first aid kit and a toolbox with common hand tools for emergency mechanical and electrical repairs.

Testing the Plan. The purpose of tests is to assure completeness of the plan and to correct weaknesses found in carrying out the plan. Tests should not be announced in advance except under extraordinary circumstances. Regional and local managers should have partial tests of the enterprise’s emergency plan conducted as they see the need, except that there should be, at a minimum, a full test of the plan every 2 years.

Customizing the Plan. Plans can be supplemented by materials (addenda, enclosures, attachments, annexes, etc.). Each supplement discusses a single topic and usually contains material that changes from time to time. By committing transient information to supplements, you can rewrite materials without having to rewrite the whole emergency plan. Following are examples of some material covered in supplemental documents:

• Civil Disturbance. Civil disturbances, riots, and insurrections can occur almost anywhere, even in small towns. Such events can cause severe disruptions of communications and transport, interruptions to the supplying of utilities—water, gas, electricity; shortages of food and like problems that can have serious effects on even the simplest of operations. Normal access routes may be blocked; therefore, employees must plan for alternate routes to reach the corporate facilities where they normally work. Wallet-size emergency identification cards can be issued to assist employees in getting through police lines and to travel to and from the work sites and their homes. Use of such cards should be coordinated in advance with local police authorities by regional managers. Employees should be warned by supervisors not to get involved in discussions or arguments with dissident persons, as this may make employees and the enterprise targets of violence.

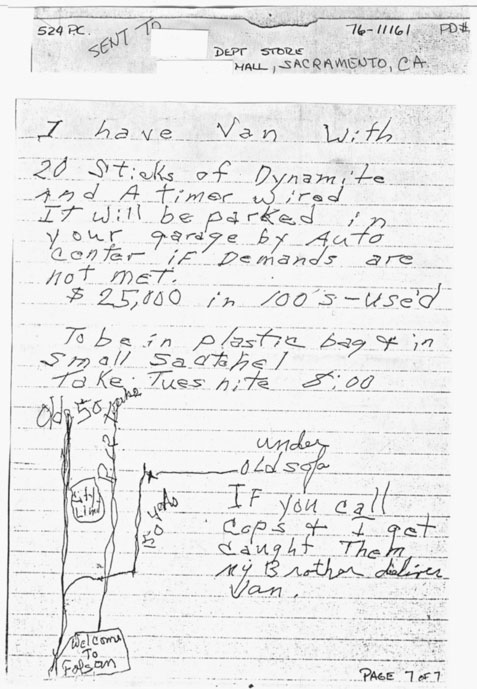

• Bomb Threats. Bombings and threats of bombings are too frequent to ignore. You might recall the bombing of the Federal Building in Oklahoma City, the bombing of the U.S. Forest Service Office in Carson City, the letter bombings by a crazed serial bomber, the bombing of the World Trade Center in 1993, and the destruction of the World Trade Center by passenger aircraft used as aerial bombs in 2001. The mere threat of bombing can cause consternation and distress. Each time a school gets a bomb threat, the school has to be evacuated and searched. In 1995, the mere threat of a bomb closed down the air mail facility at Lost Angeles International Airport. How would such occurrences affect your enterprise? If a bomb threat is received, the senior person in the facility (store, warehouse, distribution center, office) calls the police. When a special bomb threat number is available, keep it on file; otherwise, use the general police emergency number (normally 911 in the United States). There are basically three methods of attacking with a bomb outside of open warfare: putting a bomb in a motor vehicle or adjacent building, putting a bomb in a letter or package, and suicide bombing. Before calling the police, however, attempt to get the following information: date and time of a threat; any clues which might aid the police in identifying the location of the caller and the telephone number; any mention of the location, type, or time of detonation; voice characteristics—male or female. What kinds of background noises are there at the caller’s end of the line? Are there machinery noises, traffic, radio, TV? Do you believe the caller is sincere? Call the police and give them the information you have. Follow their advice. Local human resources people, managers, and supervisors should keep records of discharged employees, especially those who may have threatened to “get even.” If there is reason to believe the threat is sincere, or if a bomb is discovered, the senior person present should order an evacuation of the enterprise’s facility, or that part of a facility controlled by the enterprise. The corporate office should have a standard, clear, simple procedure published to managers at all levels well in advance about when an evacuation may be ordered. If an evacuation order is issued without due cause or clumsily, panic may occur. In an evacuation, use stairs because elevator shafts are prime locations for explosive devices. Warn other facility occupants. The local manager (store, warehouse, distribution center, office, etc.) should keep track of the results of threats or actual bombings in the local area, including actions involving nonenterprise facilities. Knowing the underlying reasons for threats and bombings of other facilities is important because they may indicate your own facilities could be future targets.

• Letter Bombs. Letter bombs are sometimes employed against businesses. If any such bombings are occurring in the local area, the local manager should institute a procedure for screening incoming mail and packages. Get prior advice from local police. Characteristics of letter bombs are origin outside the country; return address, none or fake; addressee is by name; and size, letter size but thicker or simply a large, thick envelope. Trigger devices: envelope—triggered by pressure release activated by cutting open or tearing open an envelope; package—triggered by an electrical circuit breaker activated by opening the package or cutting the tape.

• Countermeasures: awareness, alertness, care; separate mail facilities; X-ray, and similar procedures. Take photographs of the letter or package for identification and follow-up.

• Recommendations. Keep in mind that an attacker picks the time and place of a bombing or calling in a bomb threat. It adds an extra protection against revenge bombings if discharged employees or laid-off persons are given the most care possible not to offend their dignity or to treat them disrespectfully. Can you protect against car bombs and suicide bombers? The answer is clear. A retail establishment can build in so much security that it looks like a fortress. People do not like to shop in fortresses. However, in a warehouse, distribution center, or office, especially when the enterprise controls all the space immediately around it, there can be strict security against most kinds of threats. Persons must agree to surveillance, even searches to get into the facility. How open an office, warehouse, or distribution center may be depends on its type and location. Many retail enterprises would not survive unless they foster a welcoming and open image. Preparing in advance to cope with a variety of threats can help control damage and loss, but the amount of security must be balanced against the retail enterprise’s image, which is part of its marketing program.

• Earthquake. In most of the United States, the prospect of a serious earthquake is remote. In some parts of the country, earthquakes happen fairly often. In many foreign lands, there are regions where earthquakes are common. It is wise to have an earthquake plan just in case. After an earthquake, outside assistance may be cut off. Employees in the earthquake zone may have to “make do” with what is on hand. When serious damage occurs, the damaged enterprise facilities should be shut down so employees can get to their homes and families. However, leaving the facilities and going into the streets may be more hazardous than staying in the building. Bridges and telephone lines will be damaged. There will be fires. Debris will block roads. Because of the enormous physical forces generated, an earthquake can be the most terrifying experience possible. Therefore, cool heads must prevail. Other than the forces of nature, panic is the worst enemy during an earthquake and afterward.

• Severe Weather and Flood. After a severe storm (rain, snow, ice, wind) or flood, if employees are still in the enterprise’s facilities, they should be released as early as possible to get to their homes before access routes are cut off. When the decision is made to maintain operations, as many employees as possible should be released. If employees are at home, they should be informed through a planned notification procedure whether they should report to work.

• Explosion or Major Fire. If an explosion or major fire occurs in one of the enterprise’s facilities, operations should be transferred to the nearest enterprise unit. In case of explosion in a store, the whole operation cannot be transferred; however, the “back office” functions can be transferred to another site. Although sales will probably need to be suspended, some store personnel will be necessary for helping in cleanup, restocking, and preparing for reopening. If there is a small fire, it should be fought using available extinguishers. However, small fires have a way of getting out of control. Use common sense. Call the fire department for assistance at the earliest possible time. Even if the fire has been extinguished when fire department elements arrive, the fire experts can determine if the fire is still smoldering and what further needs to be done. No attempt should be made to fight a major fire or operate where there has been an explosion. When ordered to do so by the senior person on duty in the facility, all persons onsite should obey fully a command to evacuate the premises. Do not use elevators as evacuation routes. Practice fire and explosion emergency procedures to keep order in case of evacuation.

• Kidnapping and Extortion. This part of the plan sets forth a methodology that can be used to help protect senior executives and their families from kidnapping and extortion. How many of these methods are used and what their composition will be should be determined by the situation existing at any particular time. Some factors determining vulnerability are public exposure; residence; business and social status; finances; political situation; and the type of organization. Kidnapping and extortion are more prevalent in some foreign countries than in the United States, so special precautions need to be taken for executives of the enterprise living in those places. The United States Department of State maintains country profiles that can be used to keep current information on conditions in foreign countries. If management in the enterprise feel executives need special protection, then they should contact professional security consultants and the Department of State. Other countries also publish data on conditions in other countries (e.g., Australia). Many of these publications can be found online. Professional security consultants can provide advice on travel, protection of children, and home security. If a kidnapping occurs, the crisis management team (CMT) is activated to conduct negotiations and to coordinate with police authorities. If a kidnap or extortion call should come into the enterprise at any level, the information should be passed immediately to the head of the CMT.

• Crisis Management Team. The crisis management team (CMT) should be activated in case of a long-term emergency situation that can threaten the basic structure of the company. The term “crisis” applies only to situations beyond the scope of ordinary business, e.g., a kidnapping of a key official of the enterprise or a major explosion, flood, or fire at one of the enterprises’ facilities. The CMT analyzes threats, develops responses to threats, organizes the responses to the threats, and assigns human resources and material assets to cope with the threats. In situations in which a designated person is in charge of a certain area or facility of the enterprise during an emergency that has risen to a crisis, the role of the CMT is to make human and financial resources available to the person in charge. The CMT does not interfere with the operation in the field but pushes resources down to the emergency area through its relationship with the governing board, its chairman, and the chief executive officer. Members of a CMT must be assigned permanently to it as an extra duty and be trained to minimize losses to the assets of the enterprise. People working on the CMT will be stressed to their utmost because of emotional drain connected with responsibility for human life, dearth of information, time constraints and pressures, strategic implications for the enterprise, and public and employee relations. A decision must be made at the highest corporate level as to the functions of a CMT in a crisis. Some specific functions to be considered are public relations, communication, negotiation, legal matters, control of financial assets, leadership, and health of persons involved in a crisis. The leader of the CMT is responsible for leading, orienting other members on their duties, keeping up on all past and current threats to the enterprise, and training in and simulating crises. There should be created a CMT charter that is then approved by the governing board of the enterprise which specifies the references and authority to delegate and from where it is derived, usually a specific paragraph contained in corporate statutes. Some items to be included in a CMT charter are under what conditions the charter takes effect, which is usually a delegation of authority from the governing board to the CMT; assignment of persons to the CMT from the various functional areas comprising the enterprise, e.g., finance, insurance, store operations, human resources, public relations, security, communications, and legal; the authority to commit company resources; and the primary mission of the CMT, which is normally protection of assets, both human and material. See the addenda to this section for a sample resolution delegating authority to a CMT.

• Contract Security Services. Under certain circumstances, it may be necessary to employ contract guard services to assist the enterprise in continuing operations when there are emergency conditions. Contract guard services may already be employed throughout the enterprise. If so, then it is a relatively simple matter to expand their contract to include the additional emergency services. If there is no contract guard service being used, one should be on permanent retainer in each region of the enterprise to provide services under emergency conditions. Guard services can assist in helping to coordinate with fire and police services; providing after-hours office security and fire checks; identifying and registering visitors; preventing unwanted visitors from entering; keeping a log of events; providing bodyguards; providing backup communications; and providing replacement personnel for around-the-clock operation. Regional managers should keep a list, including contact names and telephone numbers, of local contract guard agencies having the capability of providing the needed services on relatively short notice. A sample letter order to the guard service is contained in the addenda to this section.

Summary

In this section, we have seen the planning process for emergency plans and why we plan for emergencies. We reviewed the KISS principle, which reminds us to keep things simple so that anyone can read, understand, and carry out the plan as an operations document. We put forth an outline of a plan that covered every subject from execution instructions to the use of contract security services. At every step of the process, we have seen the necessity for having one person in charge of all corporate assets and actions to deter damage to the enterprise from natural and manmade disasters. When an emergency becomes a crisis, we have seen how a crisis management team can function to deter losses in the enterprise and to protect not only its physical assets, but its human resources as well. Keeping emergency plans simple and up-to-date helps protect the corporation from losses.

Published Works Consulted

Protection of Assets Manual. (2007). Some elements adapted by permission, copyright American Society for Industrial Security International.

Ryan, J. H. (1995). Before the bomb drops,” Management Review, August. Some elements adapted by permission, copyright 1995, American Management Association, www.amanet.org.

Recommended Sources for Further Information

ASIS Disaster Preparation Guide. (2003). American Society for Industrial Security International. Call: 703-519-6200.

Sample Emergency Plan. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Download available at www.ready.gov.

Call-Em-All Voice Broadcasting Service. www.call-em-all.com.

ADDENDUM A: SAMPLE CRISIS MANAGEMENT TEAM CHARTER LIMITED DISTRIBUTION—CLOSE HOLD

Title: Delegation of Authority to the Crisis Management Team RESOLUTION OF

The Board of Directors, First Ark Corporation

On this____________th day of__________, 200X, the Board of Directors of First Ark Corporation hereby delegates to the Crisis Management Team, organized at the corporate headquarters office in Ararat, Pennsylvania, the following powers in accordance with Article____________of the Corporation Statutes:

To analyze, develop responses to, organize responses to, and fix responsibility for responses to threats to the Corporation that create long-term emergency conditions. A long-term emergency condition is defined as one that threatens the life of an executive of the Corporation or his or her family, or that threatens the existence or ability to function of the Corporation, or one of its parts, due to the following types of circumstances: war, civil disturbance, riot, insurrection, bomb threat, major natural disaster, explosion, major fire, kidnapping, extortion, or loss of physical contact with a subsidiary.

The Crisis Management Team shall take authority under this resolution to commit Corporate Resources up to $______________.

ADDENDUM B: SAMPLE LETTER ORDER FIRST ARK CORPORATION ARARAT, PENNSYLVANIA

TITLE: Letter of Instruction: Contract Security Services

This Letter of Instruction is made in accordance with the retaining agreement between First Ark Corporation and Chronos Security Services dated ______________.

Chronos Security is authorized immediately to carry out duties for First Ark Corporation in the area of Manhasset, New Jersey, which is now operating under emergency conditions. Your point of contact is our person in charge of the area, Johnny N.

Spott, who can be reached at______________cell phone and at 2120 North Concorde St., Manhassett, NJ.

Chronos Security Services is authorized to provide the following services for Mr. Spott:

• Helping to coordinate with fire and police services and providing after-hours facility security and fire checks.

• Identifying and registering visitors. Preventing unwanted visitors from entering.

• Providing around-the-clock watchman service. Notifying responsible persons when there are unusual occurrences.

• Keeping a daily log of events. “All OK” or its equivalent is not a valid log entry.

Signed____________, Manager, New Jersey Operations, First Ark Corporation

Author’s note: The following piece about the Oreck vacuum cleaner business’s response to the Katrina disaster is not retail LP specific but is deemed of value here in this Emergency Planning “section” of the book. You are directed to the thrust of an important message and that is the value and importance of employees in helping survive a catastrophic event. Remember, employees are our most important asset!

One-on-One with Tom Oreck

When Tom Oreck took over the family vacuum cleaner business seven years ago, his biggest challenge was to transform the firm from an entrepreneurial “one man band” founded by his father, David, in 1963 into “a symphony orchestra.” Under the elder Oreck’s guidance, New Orleans-based Oreck Corporation had steadily grown into a national brand known for its lightweight, powerful vacuums. As it prospered, the company acquired a manufacturing plant eighty miles east in coastal Long Beach, Mississippi.

Tom Oreck took center stage with solid grounding in every aspect of the business. “I like to tell people that I rose up the ranks through the sheer force of nepotism,” he deadpans with self-deprecating humor. He made HBS his last training stop before taking over as president and CEO in 1999. Since then, the privately held firm has expanded its home-cleaning product line, opened nearly 500 company stores, and doubled sales (it doesn’t disclose figures). The future looked bright—until last August 29.

That’s when Hurricane Katrina almost ruined everything. In the storm’s aftermath, Oreck, 54, faced a crisis he never imagined possible: Katrina knocked out operations at the New Orleans headquarters and the Long Beach plant, pushing the business to the brink. Advanced planning saved vital data and operations, but Oreck credits employees with actually saving the company. Incredibly, the Long Beach facility, where half of the company’s 1,200 employees work, reopened just ten days after Katrina wrought destruction of “biblical proportions” on the Gulf Coast community. Oreck recently talked about that experience and the future.

“Our first responsibility was to our employees—period. The business could wait; the people could not.”

Were you prepared for Katrina?

We had always planned on the possibility that either our New Orleans headquarters or our Long Beach facility could be taken out by a hurricane. One of the things we didn’t anticipate was a storm that was massive enough to take out both locations simultaneously.

Ahead of the storm, we backed up and shut down our computer systems and transferred all the data to a site in Boulder, Colorado. The building next door to our Long Beach plant is our call center. We shut that down and transferred that function to third-party centers in Phoenix and Denver. We also did a planned shutdown at the plant and moved certain critical components off-site.

From the Houston hotel where you evacuated with your family, how did you learn that the Long Beach plant withstood an almost direct hit?

In a day or so we got a report from one of our employees who had chain-sawed a path through trees on the roads to check on the plant. He found it was damaged but not destroyed. Once we heard that, we knew we were going to be able to put it all together again. We told people, “If you had a job at Oreck before the storm, you still have a job at Oreck.” And we continued to pay people even as we were trying to put things together.

What was your reaction when you heard that the levees in New Orleans had been breached?

Our employees had evacuated New Orleans, as they had in advance of previous storms. I left my home with only three changes of clothes. And when I heard that the city was filling with water, I thought, “OK, returning is not a matter of days any longer. This is months. Who knows, maybe never.”

Did you ever consider declaring the business a total loss?

As bad as it was, and as great as the uncertainty was, there was never a question about whether we were going to get up and running. No one on the management team ever said, “What’s the point? This is a lost cause.”

The first thing we did was try to find our people. And of course, one of the problems was that cell phones didn’t work. So we immediately set up an 8 a.m. company-wide conference call on an 800 number. We did that every day, seven days a week, for more than two months until we were back in our New Orleans office. Any employee could dial into the conference call. And we did what you’re supposed to do, which is to give people the facts. That communication was vital.

What role did the company play in helping its employees recover?

Our first responsibility was to our employees—period. The business could wait; the people could not. The Long Beach plant’s parking lot was turned into what we called Oreckville. We very quickly purchased trailer homes from all over the country and brought them in. We delivered food and water by truck almost immediately. We brought in trauma doctors, and we brought in insurance specialists to help people make insurance and FEMA claims.

When you reopened the Long Beach plant on September 9, did everyone get right back to work?

The first thing we did when the lights went on [powered by hastily purchased generators from Florida] was invite employees and their families to a cookout. The idea was that in the middle of this train wreck people could do something normal that would give them hope.

You clearly put people ahead of the business in the aftermath of the storm. Had that been part of your advance planning?

The people issues involved in this were certainly the one thing we had not been prepared for. It never occurred to us that we would have to deal with such personal devastation. We put people first because it was the right thing to do. As a result, they saved our business. That’s the bottom line. We did the right things for our people, and they in turn saved the business. I’m not overstating it. If our employees had not done the heroic things they did here [in Long Beach] and elsewhere, Katrina could easily have put us out of business.

How did you keep the New Orleans headquarters operations functioning?

There was no power in New Orleans, but more importantly, there was no access and no housing. Within five days of the storm, we were operating in an IBM business recovery center in Dallas, where we sent about 120 employees and their families. We had 100 computer terminals there, and they were connected with our backup computer system in Boulder.

What’s currently your biggest challenge?