T

Taking Over a Loss Prevention Department

You have just started in your new position as a director of loss prevention. It doesn’t matter whether you were hired from the outside or promoted internally: You face the same challenges. The first several months will determine your success or failure. So what do you do?

Start by identifying how you will focus your efforts. What are the company’s expectations for you? In most situations you recently went through an interview process with the senior management of your company. What were their expectations for an LP director? They usually have a high-level view of the role of loss prevention; however, their perspectives will help you understand what they would like to see from you. For example, is their focus on shortage reduction/control, apprehensions, investigations, auditing, physical security, or a combination of some or all of them? You can also identify loss prevention challengers and supporters during this process. This can help you better prepare for interactions with senior management in the future.

The next step, which is critical to your success, is to determine what your direct supervisor expects of you. Once you are in place, try to set up a meeting with your supervisor as soon as possible. The quicker you understand his expectations, the quicker you can start developing your action plans. Initially, the best way to do this is simply to ask. Because you’re new to the organization, people expect you to ask a lot of questions. Take advantage of that. Usually, your new supervisor will have a list of things that are a priority for him. What are they? The hope is that, by asking, you will start a dialogue that will clearly define these expectations. If not, schedule additional meetings until you fully understand what your supervisor expects from you. Obviously, these priorities should be high on your list of action items.

An important factor for you to consider is the company’s reporting structure. Whom do you report to? The CEO, president, COO, store operations, finance? Each of these reporting structures will impact how you approach your job. The executive level that the LP director reports to will dictate how the company perceives LP. The higher the executive level, the more cooperation LP will get throughout the company. Ideally, you want to report to the highest ranking executive in the company. However, this is not always the case. Here are two examples of challenges you may face if you report to either store operations or finance. If you report to store operations, you will be able to effectively impact stores but may be less involved in corporate processes that impact shortage like buying, merchandising, allocation, information technology (IT), etc. If you report to finance, you may be viewed more as an auditor than a partner with store operations. You can be effective in any reporting structure, but make sure you incorporate an understanding of your reporting structure into your planning.

Another part of the company’s reporting structure that is important is who your coworkers are? Who are your peers? To be most effective, you need the support from directors in all other areas of the company. Set up “meet-and-greets” with as many department heads as possible to introduce yourself and understand their expectations of LP. Identify their opinions on strengths and areas of opportunity for the LP department. You should also specifically identify whom you need to partner with to achieve maximum results. For example, directors of store operations are critical to running effective LP programs in the stores, human resources people are important to investigations, etc. Make sure you cultivate these relationships.

Now it’s time to look at your own department. The first thing to evaluate is the structure. How many direct reports do you have? What are their functions? How many field people do you have? What are their functions? Whom do they report to? For example, some report to LP management, whereas others report to store/distribution center management. Where are they located? The answers to these questions will give you a good idea of the resources you have available to you from a personnel standpoint. Keep in mind that if you have limited LP people or even if you don’t have any, your company employees are a great resource to help support and drive your programs.

Meet with your direct reports as quickly as possible. A good approach is to meet them first as a group. This helps to understand the synergy in the group and identify common issues. Then meet with each one individually. This will enable you to understand the specific issues each one is facing. A helpful insight into your direct reports can come from past performance reviews. Take the time to read each one and understand what past supervisors thought of their performance and capabilities.

Schedule visits to your stores, distribution centers, and any other facilities your company maintains. You must observe firsthand how the business looks and works. If your company has a large number of stores, visit a representative sample—for example, different geographical areas, high sales volume stores, low sales volume stores, high-shortage stores, low-shortage stores, unique stores that do not fit the company’s standard setup, etc. You do not need to visit every store in the chain during the first few months in your new job; it is more important to understand how stores are physically laid out and operate. However, if you have a small number of distribution centers and ancillary facilities, visit all of them. Since distribution centers and ancillary facilities are usually unique, it is important to understand, similar to the stores, how they are laid out and operate.

Mix up the people you travel with. Visit stores with your LP people, senior management, district managers, regional vice presidents, human resources, etc. Visit your DCs with your LP people and distribution center management. You learn a lot about people when you travel together. Take advantage of the travel time to ask questions and get their perspectives on all areas of the company. You will gain valuable information because they are all great resources.

Many times directors will go into a new company and quickly assess the LP department. Based on their assessment, they quickly roll out new programs. Often these programs fail because the new director has not taken the time to understand the culture and the history of the company. Existing programs are in place for a reason. Existing employees will resent being treated as if what they did before was ineffective. LP people operate the way they do because they were trained and directed by previous LP management to operate that way. Spend the time to understand why current programs are in place. What is the best way to do this? Ask questions and listen. Listening is becoming a lost art. You will roll out more effective programs with less resistance if you take the time to understand the culture and history. Knowing the history of your company will help you to avoid mistakes made by previous management. Even though you are looking forward, learn from the past. You may want to change the culture you find, but it is usually more of an evolutionary process than a revolutionary process. Changing the thought processes of your department and the company takes time and effort, but it can be done. Just take it one step at a time.

During this initial time in your new position, you will be exposed to a tremendous amount of information. It is important to take notes from every one of your meetings. Unless you write it down, you will forget a lot of what you have learned. Write down what you see as opportunities. This list will enable you to develop action plans based on prioritizing the input from company management. Refer to this list every month and add new opportunities that you identify.

It’s time to start developing your action plans. You’ve heard what your supervisor’s, senior management’s and your direct reports’ perspectives are on LP; now how are you going to focus the LP department? Internal investigations? External investigations? Shortage reduction/control? Auditing? Asset protection? An effective loss prevention program is best achieved through a balanced approach.

Your two primary objectives should be to protect the assets of the company and reduce shortage. The assets of the company include people, property, merchandise, money (cash, credit, checks, etc.), information, and the company’s reputation.

Reducing shortage will add profitability to your company. The three major areas that contribute to shortage are internal theft, external theft (vendor theft can be categorized as external theft), and operational execution. These three areas cover almost everything you will deal with in your role as an LP director. Numerous categories fall into these three areas, and it is difficult to control everything. However, if you focus on only one or two of these major areas, the one (s) you don’t focus on will increase and could cancel out the success you’ve gained in the other areas.

Your vision and strategy should incorporate protecting the assets of the company and the three major areas that can cause shortage. Within your vision and strategy, you must identify your focus areas. Loss prevention can be a very reactionary business. It is important to develop an organization that can react accordingly to the incidents that occur in a retail environment; however, you must also ensure that you are working toward your vision. Sometimes you can spend weeks doing nothing but reacting to the needs of the business, but you must always bring yourself back to your vision. LP directors who do nothing but react may keep their supervisor and business partners happy in the short term, but they won’t improve the overall operations of the LP department.

Almost everything you work on should fall into your vision and strategy. Once you define your vision and strategy, you should review it with your supervisor to ensure that you are both in agreement.

You are now ready to get into the details. The first thing to look at is the LP department metrics. What statistics do they measure and hold themselves accountable to? Measurements can include shortage, internal cases, external cases, cash over/shorts, merchandise recovery, credit card fraud, bad checks, counterfeits, etc. Determine how the statistics are trending for the year in each category. Look at the past 3–5 years to understand the history. This will enable you to gauge the productivity of your department and identify areas of opportunity where you can focus your efforts.

How does your LP department track its statistics? Is there daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly, or annual reporting? It is important to have LP statistical measurement reports at least once a month. Does your department track statistics manually or using a case management system? If these reports are not system generated, it is worth the time and energy to develop them. This can be done within your own department if you have the expertise, or you may have to work with your IT people. If you have a case management system, these reports can be easily created. Either way, make it happen. It will definitely enable you to better manage your department.

Does your LP Department look at productivity by individual? One of the most effective tools to monitor and increase productivity is ranking reports. By ranking each person against his peers in every measurable category, you can identify top performers and poor performers. It is not unusual to discover that a small portion of your staff is producing the majority of your statistics. This is especially true with internal and external cases. By improving or replacing poor performers, you can raise the bar for everyone and increase overall productivity. Specifically, these reports will enable you to recognize good performance. A recognition program directly tied into individual productivity is generally well received by investigative personnel. It creates competition, which most LP people thrive on, without creating quotas. Quotas have resulted in numerous civil litigations and should be avoided.

Ranking reports also help you identify areas that might need additional training. For example, if all your investigators have low internal case productivity, what training is needed to improve their performance?

Recognition should be an ongoing component of your department. People are your most important asset. They need to be cultivated on a frequent basis. Do you appreciate being recognized for your performance? Of course, you do. Well, your people do too! If they don’t already exist, develop multiple ways to recognize good performance. This can be for statistical performance, effectively handling a specific incident, leadership, or any type of metrics. Just be sure to make this recognition meaningful. Too much recognition can take away the value to the employee. This is a good area to partner with HR. The HR staff usually have a number of programs that they can share with you. A good recognition program encourages people to strive for better performance. The better your people’s performance, the better your results.

It is critical that you manage your LP data effectively. All incident reports (internal and external apprehensions, investigations, recoveries, robberies, burglaries, unusual incidents, etc.) must be maintained and accessible. When you are taking over an LP department, it would be unusual to find that it does not already have an existing methodology for documenting and tracking its activities. Understand how it works to make sure you are comfortable that it does what you need it to do. For example, how do you request and receive an investigative report for an outlying store or location?

If you do not have IT capabilities for your LP people, you must have paper reports that capture all relevant information surrounding your areas of responsibility. If you use a systems-based case management program, evaluate its capabilities. Ensure that it provides you with the data analysis tools that you need. If you don’t have a systems-based case management system, you should make the effort to get one. Many case management systems are available. By working in partnership with your IT department, you should select the software and system that are compatible with your company’s existing IT platform. If you purchase a systems-based LP case management program, make sure it is able to feed external systems, e.g., civil recovery/demand.

If you have a staff that catches shoplifters, most states have statutes that allow merchants to civilly recover damages from adults or the parents/legal guardians of juveniles who shoplift from that merchant. It is usually called “civil recovery” or “civil demand.” The collection of restitution and civil recovery/demand should be pursued in all applicable internal and external cases. The amount that can be collected varies by state and statute. You should make sure you have your legal counsel approve the requested amount of damages in each state.

In situations in which employees steal from the company, a promissory note or restitution procedure should be in place. If an employee admits to causing a specific amount of loss to the company and is willing to pay it back, he should be asked to sign a promissory note. This form creates a legal agreement with the employee that enables you to pursue him civilly if he does not pay you back in accordance with the terms and conditions of the promissory note. Again, you should make sure your legal counsel has reviewed and approved this form.

Many companies use external vendors to handle the collection efforts for them. Some companies have their own internal collection departments. Again, in most companies, one of these processes should already be in place. Either way, review the process to make sure that you are maximizing the collection of civil remedy/demand and restitution dollars. The collected funds can be used to purchase LP equipment and services that will deter future losses. By utilizing the collected dollars in LP deterrent programs, you can more easily justify outside legal challenges that you are using civil demand/remedy as a profit center for your company.

Another important area to review is the LP budget. First, understand what your annual budget is and how it was developed. How is the department trending for the year? Is it on budget? Is it over budget? Is it under budget? Are expenses being managed properly? Poor expense management will usually put you under an unwelcome spotlight, so make sure you understand the finance methodology of your company. It is critical that you have mechanisms in place that will alert you to over-budget and under-budget situations before you receive summary reports from the finance department.

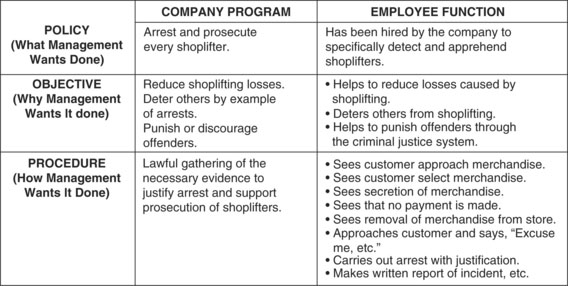

The next step is for you to understand how the LP department in your new company operates. The best way to do this is by reviewing the department’s existing policies and procedures. Is there an LP department operations manual or just a collection of memos and directives which define the operating platform for the department? Having a comprehensive and detailed operations manual is critical to the success of an LP department. An operations manual should define the expectations for the LP department. It should also contain all the policies and procedures necessary to execute the expectations for the department. The content should include internal investigative procedures, e.g., evidence collection and retention, case development, interview techniques, prosecution guidelines, etc. It should include external theft procedures, e.g., the steps necessary to make an apprehension for shoplifting, use of force, evidence collection and retention, prosecution guidelines, etc. It should also include operational procedures, e.g., audits, checklists, etc. The LP operations manual should be the foundation for the daily operations of the department. It will ensure consistency throughout your LP organization. All training should be developed from the policies and procedures contained in the operations manual.

If there is no LP operations manual, create one. If one already exists, you should revise it in accordance with your philosophy and approach. The LP operations manual should always be a “work in progress.” As you grow in the job, you should constantly revise it as you develop your department. Once created or revised, the manual should be made available to all levels of your department.

When creating or revising LP policies and procedures, involve members of the LP department in the process. An effective methodology is to create task forces composed of members of the LP department. Assign these groups to write new or revise existing polices and procedures. This enables you to take advantage of their experience within the department and the company, as well as have them be part of the process. This leads to ownership and makes it easier to facilitate change. This concept works very well if you decide to create or rewrite the LP operations manual.

Are there LP personnel training programs in place? If a training program doesn’t exist, develop one. This should become a top priority for you. An effective training program is absolutely essential. Well-trained people enable you to execute your operations effectively and consistently.

If there is an existing LP training program in place, review the content. Is it comprehensive? Does it cover all the areas that are covered in the LP operations manual? Will it keep the company protected from legal challenges of inadequate training? Are the training programs managed by the LP department or the company’s training department? Either way, the high risk that goes along with conducting internal and external investigations can be mitigated with thorough training. Multiple methods for training should be utilized—for example, written, video, e-learning, on-the-job, classroom, etc. All training should be documented, and individual training records should be maintained on each LP person. Training should be updated along with new policies and procedures.

The best way to ensure compliance to your policies and procedures by LP personnel is to have a disciplinary action process. If LP people violate the policies and procedures you put into place, there should be accountability. This will allow you to remove nonconforming employees who can put the company at risk by their actions. Effectively managing a disciplinary process will result in better consistency in your operations.

Effective communication is extremely critical to the success of an LP department. You must have some method of communicating timely information to the LP organization. This information can include new LP and/or company policies and procedures, investigative alerts, open jobs, etc. Some type of “communication binder” should be maintained in all field locations. This communication binder can be an actual binder or an electronic folder. An electronic folder that serves this purpose will depend on your company’s IT infrastructure.

One concept that helps to develop a team is to create an identity for the LP department. This can include an LP department logo, tag line, and mission statement or any combination of the three. Many companies have a mission statement, but it is not specific to LP. Use the basic concepts from the company mission statement but tailor it to the LP department. Here is an example of an LP department mission statement:

Company XYZ Loss Prevention is committed to consistently driving processes that will improve profitability by reducing losses through investigations and operational compliance while providing a safe environment for our Employees and Customers.

A fun way to create an LP logo or tagline is to hold a contest within the LP department. Your own people can come up with some great concepts that you can turn into the LP department identifiers. The fact that they created the logo and/or tagline themselves will cause them to take ownership. If your LP people can’t come up with anything that fits your vision, work with your marketing department or, if you don’t have a marketing department, use an outside vendor.

Another concept that helps develop a team and holds your people to a higher level of accountability is a “standards of conduct.” A standards of conduct should clearly define your expectations for your LP people. It is an add-on to the company’s employee handbook. By spelling out your expectations, you can raise the performance level of your people. Because it sets a higher standard for LP people above that of the regular employees, you must work with human resources staff to gain their support. That way, if an LP person violates the standards of conduct, he can be disciplined in accordance with the standards of conduct, not the employee handbook. It will enable you to foster a higher level of ethics and integrity in your LP team. Here is an example of a loss prevention standards of conduct.

Standards of Conduct

A Company XYZ Loss Prevention employee’s conduct must be above reproach at all times. Their conduct must comply both with applicable state and federal laws which define the legal limits of their conduct and with Company XYZ policies and procedures which, at times, are more restrictive than state and federal law.

All Company XYZ Loss Prevention personnel are required to read and sign the “Standards of Conduct” form.

These standards are not intended to cover all situations, rules, policies, regulations, etc., and should not be construed as such. They are, however, indicative of the spirit and intent of Company XYZ policy and the expectation of your conduct and behavior. These standards are of such importance that any person failing to comply with them will be subject to disciplinary actions, up to and including termination without prior warning.

Maintaining the standards outlined on the following pages and the philosophical spirit reflected by them, should be the guideline in each loss prevention employee’s professional approach to their daily activities.

These standards are in addition to the policies and procedures defined in the Employee Handbook.

The original, signed “Standards of Conduct” form must be maintained in the loss prevention employee’s personnel file. (Copy Attached)

Standards of Conduct

These Standards of Conduct are expected of all Loss Prevention personnel so that no person will have cause to question our professionalism, integrity, credibility, and objectivity. In the performance of our job, we must be highly professional and must meet more exacting standards of behavior and adherence to rules. The nature of our function, authority, and responsibility requires this higher standard.

The following type of behavior is not in keeping with Company XYZ Loss Prevention Standards of Conduct:

1. Any activity, which reflects adversely on the ethical or professional stature of Company XYZ Loss Prevention Department. Covered under this statement are such activities as

2. Failure to objectively and factually report information required or obtained within the scope of employment. This statement covers not only the willful misstatement of facts, but also knowingly omitting pertinent information from reports and/or the purposeful “slanting” or “coloring” of reports.

3. The failure to report any information, however obtained, which could conceivably bear on or be pertinent to any Loss Prevention investigation or be of legitimate interest to company management. For example, any customer or Employee detention must be reported to your Supervisor in accordance with established time frames.

4. Failure to submit reports as required by Company XYZ Loss Prevention policies and procedures.

5. Violation of any of the provisions of Company XYZ “Use of Force and Weapons” policy.

6. Any misuse, careless or improper handling of funds, evidence, or records entrusted to our care.

7. Any misuse of company equipment or property, misuse of position or authority, or agreement to accept “favors” not granted others and available or offered us because of our position is prohibited. Covered under this statement are such things as the following:

8. Failure to follow Company XYZ Loss Prevention policies and procedures with regard to stopping, questioning, and/or apprehending both Employees and the customers.

9. The failure to be completely truthful and candid in response to any official request for information.

10. Inappropriate use of CCTV cameras and equipment. CCTV cameras and equipment must be used for work-related purposes only.

11. Failure to follow policies and procedures outlined in the Loss Prevention Department Operations Manual or directed by the Director of Loss Prevention in the form of a memo.

The above statements are not intended to cover all situations, rules, policies, regulations, etc., and should not be construed as such. They are, however, indicative of the spirit and intent of Company XYZ Loss Prevention policy and the expectations of your conduct and behavior. These standards are of such importance that any person failing to comply with them will be subject to disciplinary action up to and including termination of employment without prior warning.

Maintaining the standards above and the philosophical framework created by them should be the guideline in your professional approach to your daily activities.

I HAVE READ AND UNDERSTAND Company XYZ Loss Prevention Standards of Conduct. I understand these standards are not intended to establish any expressed or implied contractual rights. I also understand that any violation of these standards may result in disciplinary action, up to and including termination of my employment without prior warning. These standards are in addition to the policies and procedures defined in the Employee Handbook.

| NAME (PRINT) Employee NO. | ___________________________ |

| SIGNATURE DATE | ___________________________ |

Technology should not determine your LP strategies. Technology should help you achieve your LP strategies. As part of your assessment process, you need to evaluate the technology currently available to your department. Do you have CCTV? If so, how is it utilized? Are there fixed cameras; Pan, Tilt, and Zoom (PTZ) cameras; or both? Is it overt, covert, or both? Do you have digital video recording (DVR) technology or analog video recording technology (VHS)? Are there remote monitoring capabilities? Do your people have desktop computers or laptops with docking stations? Do they have access to LP/company systems for investigative purposes?

Physical security is a responsibility that most likely falls directly onto your shoulders: burglar and fire alarm systems, lock strategies for doors, access control (if applicable), cabling of high-value apparel, locking caselines, locking fixtures, safes, securing of high-value products (pharmacy, fine jewelry), protecting of merchandise trailers, etc. There is information available on these topics in this book. You should learn about each category so that you can incorporate your physical security strategies into your overall vision for your LP department. When it comes to physical security, the simpler, the better. The easier a physical security system is to use, the better compliance you will get from the users. This is important because, even if you have a great physical security system, if no one uses it, it has little value.

Now ask yourself, does your current equipment and technology enable you to accomplish your vision for the LP department? If not, determine what you need. How do you know what’s available? Simple, talk to the LP vendor community. There are hundreds of vendors who sell and service LP equipment and technology. All of them would be interested in educating you on their product(s). Once you have learned about and are ready to choose a type of equipment or technology, reach out to fellow LP directors that use the particular product(s) and ask them for feedback. Most will be happy to give it to you. Or, reach out to your fellow directors first and then talk to the vendors. Whichever approach you take, other LP directors are a great resource.

Now you’ve done your homework on the equipment and/or technology you want to buy, and you’re ready to start the process to purchase it. The first step is to learn what your finance department requires to justify an expenditure. All companies have different methodologies for this process, but all require that you demonstrate a return on investment (ROI). Learn the formula for your company and incorporate it into all your proposals.

Exception reporting is an essential LP tool. Strategically using exception reporting will improve your efficiency because you can focus on problem (exception) resolution. You don’t need to know when things are working as expected, only if there is a problem. Of course, the most common exception reporting systems for LP are POS based; however, exception reports on almost any company process that impacts shortage are valuable. Knowing which stores have high or low results in comparison to the entire store population enables you to focus on areas and locations that are exceptions. For example, for Mark Out of Stock (MOS) percentages, a high number could mean that the store is not handling MOS merchandise properly or there is some other issue. By investigating that high number, you can identify, address, and correct the issue which will reduce the MOS. Reduced MOS improves profitability. If a store has a low MOS number, it could mean that it is not processing MOS properly or possibly even throwing it away. This would cause shortage, and the store would not be replenished for the damaged merchandise. Use exception reporting to identify anomalies and investigate the anomalies. You will be able to spend less time and get better results because you are addressing exceptions only.

To stop return fraud, a refund control program is absolutely necessary. Without an effective refund control program, your company is at risk. Poor refund control can lead to internal theft (fraudulent returns by employees) and external theft (shoplifting for the specific intent to return.) It can also allow duplicate receipts, counterfeit receipts, and the reuse of the same receipt multiple times.

Thieves find ways to circumvent polices at individual stores. The best defense is a corporatewide system to track returns. The main focus should be on nonreceipted returns. If your POS system allows a way for cash to be obtained without a receipt, the thieves will find it. A refund control system that stops nonreceipted returns works by requesting IDs from individuals returning merchandise without receipts. You set the parameters for how many returns you will allow before you shut them down. This is called “velocity.” The system should also identify counterfeit receipts and previously used receipts and stop them as well.

Refund control systems can be developed internally or purchased from an outside vendor. Either way, refund control is a must have.

One of the issues that you will face when it comes to the implementation of new company systems is where and when the LP requirements are included in the process. For example, a new POS system needs your involvement to make sure the proper controls are included to prevent losses at the registers and in the cash office. Many times, the LP requirements are scheduled to be implemented at a future date. This future date is often called “Phase 2.” Be aggressive in having the LP requirements included in “Phase 1.” “Phase 2” may be delayed or even canceled, and you will have lost your opportunity to get the LP components you need. Developing an effective partnership with the IT department will enable you to always be part of “Phase 1.”

Organized retail crime (ORC) is a significant part of external theft losses in most retail environments. Evaluate the extent to which your company is a target of ORC. Based on this analysis, determine how to use your LP and store resources to minimize this threat. Do you lock up your targeted product? Do you place it behind counters? Do you work with law enforcement to apprehend the thieves? Do you allocate some of your LP personnel to focus only on ORC? Whatever plan of action you develop, be sure to include ORC in your strategies to control losses.

Shortage programs are an integral part of any LP program. Controlling shortage is a process. You must have all areas of the company working together to control shortage. There must be daily attention to all shortage control procedures. For this to happen, there must be support for reducing shortage that comes from the senior management of the company; otherwise, it will not be a priority.

The first step in creating a shortage program or enhancing an existing one is an Executive Shortage Committee. This committee should include senior management and director-level people. The higher the management levels in these meetings, the better. Representation should include LP, finance, operations, distribution, buying line, IT, internal audit, inventory management, human resources, etc. You want people on the committee who can go back to their departments and make things happen. This committee should focus on all areas of the business that can impact shortage. It should develop action plans that the people on the committee can go out and execute. Examples include store/DC LP standards, focus on high-shortage stores, focus on high-shortage merchandise, EAS tagging standards, etc.

A shortage program should include monthly shortage meetings in all stores and DCs. These meetings should include the facility manager and key people in the location. The monthly topics should focus on high-shortage areas and processes. All facility employees should be made aware of the focus topic each month. This can be done through separate meetings held at different times throughout the day. Retail schedules rarely allow for store-wide meetings, so the individual meetings should be scheduled so that all employees are given the necessary information.

Another effective method is the development and implementation of individual store shortage “action plans.” These action plans should be based on the shortage results from the most recent inventory. Focus areas can be companywide, store specific, or a combination of both. The plans should define what each store is going to do to address the high-shortage areas. District/regional store operations and LP managers should be required to approve the action plans. The action plans should be inspected throughout the year, and stores must be held accountable for not executing their plans.

Some companies focus their efforts on high-shortage or “target” stores. These “target store” programs are based on the concept that reducing shortage in the highest shortage stores will be the best return on the investment of resources. This approach is usually very successful in those stores. The challenge with this approach is that “nontarget” stores can experience increased shortage because there is not a focus on them. Those stores can then become the new “target” stores.

An effective shortage program must include employee awareness training. Employee awareness starts with educating employees on their role in controlling losses in the company. What can they do every day to positively impact shortage? You must define the expectations for every employee. They need to take ownership for controlling losses. If they have “ownership” for controlling losses, they will be more likely to help than if they don’t feel they have any responsibility. This can be done by communicating your message(s) in new hire orientations, company newsletters, posters, etc. Developing a shortage logo and tagline will “brand” your program. As with an LP department logo and tagline, create a companywide contest to get ideas. Your company employees can often come up with some great concepts. If your company employees can’t come up with anything that fits your vision, work with your marketing department or, if you don’t have a marketing department, use an outside vendor.

Since shortage control requires daily attention, your goal should be to create a culture of loss prevention. You want all employees doing the right things every day. Doing the right things means not stealing, reporting those that do steal, and following established procedures to prevent loss. A loss prevention culture takes time to develop, but it will pay off every year in low shortage if it is maintained throughout the company.

A quote that has been around for a while is “a well run store equals low shortage.” This makes perfect sense, but how do you ensure that a store is running well? How about another quote? “You get what you inspect.” An LP audit program enables you to monitor store compliance to shortage control policies and procedures on a periodic basis. By monitoring store performance and correcting identified deficiencies throughout the year, you can prevent a poor shortage result.

If your company does not have an LP audit program, you should consider putting one in place. If your company does have an existing audit program, you should evaluate its effectiveness. Often you will find the existing audit program does not have a true impact on controlling shortage.

The two keys to a successful LP audit program are objectivity and accountability. The first key is objectivity. The audits must give an accurate picture of what is actually happening in a store. If they don’t, they have limited value. To be able to correct issues, you must know what they are. Auditors must be able to objectively report their findings. Of course, that makes sense, but it doesn’t always happen. Here is something to consider. If the person who conducts the audits reports directly to the district manager or regional manager who is responsible for running the stores, can he truly audit objectively? Will this “partnership” be jeopardized if the LP person fails them in an audit? Will performance evaluations be negatively impacted? Review audits for the past year. Are all stores passing? If they are, it is an indicator that the audits may not be objective. It would be a very well run company indeed if every store passed every audit. Try to set up your LP auditors so that they report independently from the people who run the facilities they are auditing.

The second key is accountability. If a store fails an audit, are there consequences? Are the consequences serious enough to get the attention of the person being audited? For example, if a store fails an audit, does it result in disciplinary action? Does it impact its performance evaluation or bonus? If the consequences aren’t meaningful, store management will not focus the appropriate attention on taking the actions necessary to pass the audits. You must elicit senior management’s support in developing the appropriate consequences so that store management knows that it is a company priority.

If you don’t have an effective store audit program or don’t have one at all, how do you get started? Create a task force that includes loss prevention executives and store line senior management. If store management is included in this process, there will be more of a sense of ownership, and the audit will have more credibility. Develop an audit that addresses shortage control in all areas of store operations. This does not normally include creating new polices and procedures, but just selecting those that will make a difference in reducing shortage. The contents of an LP audit should include cash office, receiving, point of sale (POS), physical security, EAS tagging compliance (if applicable), and anything else that impacts shortage. As a side benefit, this process can result in strengthening controls in almost all existing store procedures, because when the task force reviews all procedures, they will usually find ways to improve them.

To ensure that the new audit works effectively, make sure you “field test” it. This enables you to identify problem questions and correct them before you roll out the entire program.

Once finalized, the revised procedures and new audit forms should be provided to all stores. Stores should be given some time to “ramp up” before the new audits are scheduled to begin.

One way to ensure auditing consistency is to create a loss prevention auditor’s manual which contains detailed explanations of what the auditor should be reviewing for every question on the audit. This manual will ensure that all auditors review the same areas in exactly the same way. The completed manual should also be provided to every store so that they also know every question and the audit instructions. Communicating this information to the stores will eliminate many of the challenges when points are not awarded.

To help stores pass their audits, which is, of course, the goal of the program, stores should be required to complete daily or weekly checklists. These checklists are tools to ensure daily attention to the policies and procedures that are reviewed on the audit. Checklists can be created directly from the audit. Many times stores will break the audit into sections and use them as checklists.

Another component of an audit program that gets results is a random and unannounced audit schedule. The only way to get a true picture of what is really happening in a store is to show up when the store doesn’t expect you. Another benefit of a random and unannounced audit schedule is that all stores will operate more consistently on a daily basis in expectation of receiving an audit.

Audits must be conducted often enough to allow “course correction” during the year. Many companies take once-a-year inventories. It is the consistent execution of shortage control policies and procedures that provides the positive end-of-year results. One formula that works well is a quarterly audit in all stores and a monthly audit in high-shortage stores. Of course, your program must fit your company’s structure and budget. Timely reporting of audits is also important. As soon as an audit is completed, the results should be communicated to the store and the district manager. After that, audit scores should be tracked along with all the other company performance measurements and be included in annual performance evaluations.

Cash control is an important part of any LP program. Review the existing procedures: “Follow the money.” What are the controls in the cash office? Are all cash office personnel background-screened? Is the physical security of the cash office (locks, safe, camera coverage, etc.) adequate? How are the basic funds for each register drawer set up? How are they transported to the sales floor? What are the controls at the registers? How is change handled? How are cash pickups done? Who counts the daily sales and creates the deposits? Who verifies the deposits? Are the deposits taken to the bank by sales personnel, or are they picked up by an armored carrier service? Are there controls in place to make sure that the deposits arrive at the bank? If a deposit does not make it to the bank or there are discrepancies with the deposits that are identified by the bank, how is it communicated and to whom? The answers to these questions will enable you to identify the effectiveness of your company’s cash control procedures.

Timely notification of cash register overages and/or shorts to LP is essential. Determine how stores communicate register shortages to LP for investigation. Make sure that LP is notified as quickly as possible. Once notified, how do the LP personnel keep track of the shortages by store? Cash shortage investigations should always be a high priority for your LP personnel. Employees who steal cash are usually stealing in other ways, too.

Credit card fraud, fraudulent and/or bad checks, fraudulent traveler’s checks, and counterfeit currency are other concerns that should not be ignored. Each of these areas has available controls that can be utilized by retailers. Meet with your finance department to learn about the controls that are currently in place. Ask the finance staff to provide you with regular reports on fraud losses. Review how employees are trained to accept checks. Is there a check guarantee program? Are ultraviolet lights used to check for counterfeit currency, traveler’s checks, and credit cards? Do employees check for identification? Are imprinters used for credit cards that won’t scan? The best way to prevent fraud is by having well-trained and alert employees. Train employees to follow all the required steps when accepting credit cards, checks, traveler’s checks, and currency.

One of the most effective ways to get information regarding people or issues that are causing theft or shortage is an employee hotline. Implementing a confidential way that employees can communicate information will increase your chances of identifying where and how losses are occurring in your organization. In addition, by paying out cash awards for information that leads to correcting the cause (s) of the loss, you will increase the information flow. Although most people don’t call specifically to get the money, they appreciate getting the award.

Employee hotlines can be managed internally or by an outside vendor. As long as the information can be provided and managed confidentially, either way will work. However, make sure it is an 800 number so that employees can call from anywhere. Many companies use an outside vendor because they believe it makes the employees more comfortable in making the call knowing it is not going to a person inside the company.

Once you have established an employee hotline, publicize it through all available methods—employee training and orientations, newsletters, the company website, paychecks, wallet cards, posters, employee handbook, etc. One effective way to ensure that all employees always have access to the number is to print it on their discount cards. In addition to the LP hotline, make sure that you get all your LP messages out using the same methods.

When rolling out LP programs, always use the company’s current communication protocol. For example, if you roll out a new procedure on controlling credit card fraud to the stores, use the existing company communication vehicles. If the stores get a weekly operational hardcopy communication, include your LP procedures. If the stores get a weekly email communication, include your LP messages. This way, the stores receive the LP information as part of the other information that is rolled out that week. Incorporating LP information into the communication vehicles of the business is the best way to get your messages out to your audience.

Background screening is the best way to prevent hiring dishonest employees before they even walk onto the selling floor. Review your company’s existing background screening program. Do you have one? If you do, is there drug screening? Are there criminal checks? Credit checks? Employment verification? Education verification?

Because of the high turnover in retailing, background screening is expensive, so implement a strategy that is cost effective. Determine the risk levels of your employees. Management and cash office personnel should be at the top of your list in terms of risk level. People in these positions have the most access to cash, merchandise, and company property. Evaluate all the positions in your company and develop a background screening strategy that fits. HR is an excellent partner in this evaluation process.

Participation in a national retail database is an absolute. National retail databases include dishonest employees and shoplifters from fellow retailers. This information is the most specific to the retail industry. They are relatively low cost and usually have a higher “hit” rate than the other checks and verifications. However, these databases are only as good as the information that is submitted to them. Talk to other LP directors and find the national database that includes the most retailers that you are likely to hire your employees from. If your company does not participate in one of these databases, you should definitely consider joining one.

Threat Assessment and Management: An Integrative Approach

John K. Tsukayama and Gary M. Farkas

Introduction

Prevention of crime in the workplace typically is the sole province of the security professional. In the retail sector, internal dishonesty and shoplifting offenses are the primary loss prevention concerns of in-house or contracted security agencies. Aside from those occasions when advanced technology needs to be adopted or mystery shoppers employed, external consultants are rarely used in the typical retail establishment’s loss prevention efforts.

Workplace violence is a unique concern in the retail environment. While industrial facilities and many service businesses can establish basic perimeter defenses against suspected threats, the retail establishment’s need for open access creates vulnerabilities not seen in other industries. The unrestricted environment of the retail sector allows both the general public as well as former and current employees (some of whom may have hostile intent) to closely approach intended targets.

Because of the unique demands of workplace violence prevention efforts, the retail security professional needs to be aware of the specialized and generally accepted principles of Threat Assessment and Management (TAM). This approach blends the expertise of the security professional with those of other consultants. In this section, we discuss how psychological and security professionals, working closely together, can add value to a retail organization’s efforts to reduce the risk of workplace violence due to disgruntled employees or known outsiders.

A Special Loss Prevention Problem

Traditionally, loss prevention investigators have had the task of gathering evidence relating to a known crime that has already occurred, or one that is believed to be already occurring. In those cases, either normal reconstructive or constructive methods will be applied. The who, what, where, when, why, and how aspects of the process of investigation will guide the investigator to collect and present evidence that can be used to justify appropriate action. In the private sector, the goals of loss prevention, economic recovery, and employment termination are typical, whereas in the public sector, the goal is normally the bringing of criminal charges.

There is, however, one kind of investigative problem that differs significantly from these norms. This type of investigation centers on the problem of targeted violence and has received increasing attention in the past 20 years. The relevant questions are not merely “What happened?” or “What is happening?” Rather, they are “What is likely to happen in the future?” and “What can be done to prevent it?”

The approach that has developed since the early 1990s is known as Threat Assessment and Management, or TAM. For our purposes, we will concentrate on the application of TAM to workplace violence prevention because this is an area of frequent occurrence in which loss prevention professionals can make important contributions. Therefore, knowledge of workplace violence is essential.

Types of Workplace Violence

There are generally considered to be four categories of workplace violence.(1) They are

• Type I: Violence by criminals with no other connection to the workplace. Entry is solely for the purpose of committing a crime such as robbery.

• Type II: Violence by customers, patients, students, clients, inmates, or others receiving goods or services from the organization.

• Type III: Violence by present or former employees against supervisors, employees, or managers.

• Type IV: Violence by persons who have a personal relationship with an employee but who do not themselves work in the organization.

The first two types of violence will tend to be addressed through normal crime prevention strategies and are typically investigated in a post-incident or reactive context. These violent incidents tend not to involve perpetrators who are targeting specific individuals for violence. One example is the convenience store or gas station robbery, an act whose criminal motive is not violence, but monetary gain. Another example is the outburst of anger that a drunken patron may direct at a bartender. This type of outburst is known as affective violence and is typically an immediate emotional reaction to a stressor, devoid of criminal motive.

In the last two categories, there is much more likely to be a specific individual who is being selected for violent victimization by the perpetrator. This is known as “targeted violence” and is the kind of violence that frequently exhibits a number of warning signs. If those warning signs are properly detected and assessed, they can give the organization the opportunity to steer the situation away from a violent outcome.

This kind of violence will tend to be what is known as predatory violence, which is violence that is planned, purposeful, and emotionless. The perpetrator will engage in behavior that is akin to hunting the intended victim(s) and may provide clues to intentions, methods, and targets prior to an actual attack. It is in these situations that TAM is intended to be used. Our focus will be on predatory violence relating to type II, III, and IV workplace violence.

Threats

The topic of threats is an area in targeted violence prevention that carries great potential for misunderstanding that leads to ineffective action or overreaction. In many organizations there exist workplace violence policies that prohibit employees from making verbal threats against others. The statement “I’m going to kill you” will generally be understood as a threat, and action will be taken. Consider, too, the statement “Unless something around here changes, people are going to get hurt.” Is that a threat or not?

The ambiguity involved in these situations requires refinement. The term “threat” tends to be used in two ways:

• Threats Made: The purest form of threat is an unconditional statement of intent to do harm. It is characterized as a communication.

• Threats Posed: A person, situation, or act that is regarded as a menace. It is characterized as a danger.

Another term we will use here is “instigator,” by which is meant a person who has either made a threat or poses a threat to the targeted victim(s).

Threats Made

There has been some significant research completed regarding threats to do harm that indicates the need to take a more thoughtful approach to threats made. For many years, it was believed that the persons most likely to carry out attacks are those who make direct threats. In the 1990s the U.S. Secret Service, the national Institute of Justice, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons studied the behavior of 83 persons who carried out actual attacks, or came close to attacks, on prominent public figures. As a result of that research, it was concluded that “persons who pose an actual threat often do not make threats, especially direct threats.”(2) It was further concluded that, “although some threateners may pose a real threat, usually they do not.”(3)

This is not to imply that because a direct threat has been made that you can discount it as an indicator of future violence. In the areas of school violence, domestic violence, and workplace violence, it is not uncommon for direct threats to precede violence. Loss prevention professionals need to heed all threats, both made and posed.

Threat management experts Frederick S. Calhoun and Stephen W. Weston provide a means of sorting the confusion regarding threats. In their book Contemporary Threat Management, they introduce the concept of what they term the “Intimacy Effect.”(4) Essentially, it is believed that greater intimacy between the instigator and the target will make direct threats more reliable as pre-incident behavior. Therefore, where there has been some degree of intimacy, such as between coworkers or spouses, a verbalized threat should be taken more seriously than one spoken about a public figure not personally known to the instigator.

Threats Posed

While many who make direct threats never attempt an attack, the lack of any threats made cannot lead the investigator to necessarily conclude that there is no threat posed. The central concept of a threat assessment investigation is to attempt to determine whether, at the present time, it appears that the instigator poses a threat to the target.

Persons known to possess all f the following should be considered threats posed to the target (s):

Lacking one or more of these factors probably lessens the threat posed, although movement toward target proximity would not necessarily be relevant if the means exist to create and deploy a mail bomb (or other similar device) delivered by a third party.

Red Flags

It should be clearly understood that there are no reliable profiles that can be of meaningful use to TAM practitioners. No set of attributes will be present in all those who perpetrate lethal targeted violence. Likewise, the absence of those attributes should not be taken as a signal that the instigator does not pose a danger to a particular target. For these reasons, “profiling” is not a responsible approach to take when considering potential targeted violence.

Some factors have been identified in cases involving targeted violence that do bear attention. Organizations should train supervisors and employees to be aware of these red flag items.

If they are present, the red flags should not be used to conclude that a danger is actually posed. In fact, in the majority of instances, individuals who exhibit one or more of these items never will carry out, or even desire to carry out, targeted violence.

The presence of the red flags should signal to the organization that some level of assessment should be performed to determine whether further concern is justified. Only after an adequate TAM process is completed is it wise to specify appropriate action by the organization. In many cases, TAM investigation will determine that the person of concern lacks the grievance, violent ideation, inclination, means, or preparation necessary to carry out an attack.

Employees should be encouraged to report the red flags (or any other reasons that cause them concern) to the TAM team with the understanding that no negative action will be taken against the person of concern solely on the basis of their report. To do otherwise may make employees hesitant to share information at an early stage when there still exists ample opportunity to address the situation while the instigator is still capable of being diverted.

Red Flags

Following is a list of red flags employees should be aware of:

4. Recently acquiring weapons, especially in conjunction with dispute events.

6. Hypersensitivity to normal criticism.

7. Harboring grudges in conjunction with imagined or actual grievances.

8. Preoccupation with themes of violence.

10. Interest in highly publicized incidents of violence.

11. Loss of significant relationships, including marriage or other intimate relationship.

12. Legal or financial problems.

13. Ominous, specific threats.

14. Suicidal/homicidal thoughts or speech.

15. Stalking or placing employees under observation.

16. Verbalizing a strongly held belief that others mean him harm.

17. Being frequently sad, angry, or depressed.

19. Marked changes in behavior or deteriorating hygiene.

No list of red flags or warning signs can be exhaustive, and the fact that something of concern to employees does not appear on this list should not prevent the TAM team from considering it when deciding to proceed with a formal assessment.

TAM Teams

TAM is a complex undertaking that has the twin objectives of determining whether the current situation is apparently moving toward a violent act and specifying a set of measures the organization can undertake to divert the instigator away from violence.

The practice of creating specially trained teams has arisen to provide the talents of a multidisciplinary group to both sort out the complexities and handle the numerous tasks associated with quality assessment and planning in the high-stakes endeavor of targeted violence prevention.

These teams are known by a variety of names. They may be called threat management teams, incident management teams, threat assessment teams, crisis management teams or go by any number of “committee” names. In any case, the teams will often include TAM-trained representatives from the following parts of the organization:

In addition, someone in the management chain above the affected employees will often be included so that the team has sufficient information regarding the day-to-day operations of the relevant department.

Certain outside consultants will often be contacted to assist the team in its assessment and planning duties. Some such consultants may include

• Psychiatrists or psychologists experienced in violence risk assessments;

• Investigators who specialize in TAM work;

Finally, the TAM team should be headed by a manager with the authority to fully commit the organization’s resources to the effort and expense necessary to take meaningful protective measures immediately upon determining that they are essential. This TAM team leader should make the final decision on the organization’s response if the team cannot reach consensus. If either the authority to proceed or sufficient decisiveness is lacking in this key person on the team, undue delay, inaction, and very possibly physical harm may ensue.

TAM Principles

While it is common to react to news of a mass workplace murder by assuming that the act was entirely unpredictable and thereby unpreventable, the process of threat assessment investigations relies on a number of major principles that represent an absolutely opposite view:

1. Targeted violence results from a process of thinking and behavior that can be understood and often detected in advance. To be able to carry out an act of targeted violence, the perpetrator must pass through a series of steps along the way. He must develop a sense of grievance or injustice that motivates him. He must hit upon violence as the only or best option available to him to redress his grievance. He must select the individual or organization to target. He must choose the method of attack as well as the date and time for an attack. To do so, he may conduct research on the target, including stalking the targeted individual or placing the target site under surveillance. He may need to acquire the means to approach the target, breach any security measures in place protecting the target, and carry out the intended attack to the desired conclusion. The instigator’s dispute with the target and subsequent planned violence may take center stage in his life and rise to the level of an overriding obsession that the instigator readily and compulsively talks about to those around him.

2. Targeted violence takes place in the interplay between the instigator, past stressful events, the target, and the current situation. It is considered useful to determine how the instigator has reacted to prior instances of unbearable stress. If, in earlier situations involving significant losses (home, family, job, position, etc.), the instigator attempted acts of violence (including directed at himself), this information may be crucial to an understanding of how he may perceive his present situation. Likewise, other information regarding the instigator’s background may be critical to the assessment process. Where he lives; his vehicles; his access to or familiarity with weapons; his educational, medical, and employment histories are all among the information about the instigator that the TAM team may require. Information regarding the target will also be critical. The TAM team should seek answers to the following questions. Is the target known to the instigator? Can the target be easily approached at work, home, or other obvious locations? Does the target take the threat posed seriously? Can the target’s normal locations be “hardened” (receive additional security measures)? Will the target accept and follow security advice? Finally, the current situation, both in terms of any event likely to trigger untoward acts and the overall atmosphere, environment, and influences acting on the instigator must be examined. Whether the instigator is surrounded by a culture, family, group of associates, or counselors that encourage or discourage violence as a means of conflict resolution is also important to determine.

3. Addressing targeted violence requires determining the “attack-related” actions of the instigator. As noted previously, the instigator will normally travel a path leading to an eventual attack. At each stage of this journey, he may communicate information or be observed in behavior that signals his thinking, planning, and preparation. Searching for information regarding these factors is key to the proper assessment of a situation, to determining whether the instigator poses a present danger to the target (s). If, for instance, the instigator is known to dislike a coworker with whom she has exchanged angry words, is this sufficient reason to consider her to pose a threat to the target? An assessment investigation that determines that the instigator recently has acquired a firearm and was seen sitting outside the targeted employee’s home in her car would clearly support an assessment that the situation should be of serious concern.

The Role of the Loss Prevention Professional in Threat Assessment and Management

The conduct of TAM assessment investigations relies on the same skills, techniques, and aptitudes of any other kind of investigation. The loss prevention professional should take steps to prevent the investigation itself from becoming a factor that contributes to an attack. Therefore, much of the work of the TAM team should be kept from becoming obvious to the instigator.

The following should all be considered in TAM assessment investigations by the loss prevention professional:

• Reviewing records. If the instigator is an employee, all available files must be reviewed, including employment application; background reference checks that were completed at the time of hire; all evaluations by supervisors, coworkers, or subordinates; records of counseling or discipline; any complaints, grievances, or even lawsuits against the employer, coworkers, and others; attendance and leave records; training records; and any prior safety or misconduct investigations involving the instigator. Examining the context in which the instigator first became of interest to the TAM team. Care should be taken to understand the reasons for the initial report concerning the instigator and determining the credibility of the complainant. The first notice to the TAM team that the instigator concerns a coworker, supervisor, or other company-related person may contain information that will help the TAM team understand the nature of the dispute or injustice that may be at the heart of any motivation to commit violence.

• Researching in the public record any history of court actions (civil or criminal) involving the instigator. If the instigator is involved in a years-long dispute with an individual supervisor or store, the record may be rich in information that describes the degree of anger that the instigator may harbor against the target (s). Similarly, if the instigator has elevated the grievance to a “cause” or “crusade” against perceived perpetrators of great injustice, the TAM team should carefully consider how committed the instigator may be to punishing the target, regardless of the cost, to himself or others.

• Interviewing persons with historical or current information on the instigator’s thinking, capabilities, motives, and plans. Care should be taken that anyone interviewed by the TAM team can be relied on not to disclose to the instigator that the assessment investigation is being conducted.

• Examining the instigator’s workspace. In the case of instigators who are employed by the retailer, and if consistent with established company policy, examining the instigator’s immediate work areas may be of immense value to the assessment. If the examination can include a review of the company computer files accessed by the instigator, it may be possible to uncover information relating to the underlying grievance held by the instigator, pre-attack planning and actions, ritual settlement of his affairs and disposing of his property, and the identity of intended targets. Also if permitted, the TAM team should try to view the instigator’s email traffic on the organization’s computer system.

• Making direct contact with the instigator. At some point, the TAM team may decide that the benefits of speaking directly with the instigator outweigh any risks of initiating such contact. Contact with the instigator may allow him to vent his frustrations and reduce his sense that only violence can give voice to his grievance. The instigator may provide a clear view of his intentions to actually cause violence and accept the attendant consequences. An instigator may reveal the amount of research, surveillance, and other attack preparation he has completed. The instigator may convince the TAM team that he lacks the organization, means, or capability to launch an attack during direct contact.

The focus of the TAM investigation should always be on seeking answers to the question of whether the instigator is progressing toward violence and, if so, how far advanced that progress may be. The answers to those questions are the heart of the actual threat assessment.

All the information that the loss prevention investigator is able to develop should be provided to the team and especially to the consulting psychologist. It is critical for the security professional to understand the ways in which the psychologist can contribute to the accuracy of the TAM team assessment and the active management of the instigator.

The security profession can provide the target hardening, investigation, and research capabilities to the overall TAM effort while the psychological profession offers insight into pathology and the likely effectiveness of treatments and health and social service diversions.

Unless the professions see themselves as allied in the TAM process, they are likely to work independently, possibly to cross-purposes. This can lead at best to uncoordinated actions of limited effect, and at worst to a string of actions that create a sequence of frustration, distrust, and hostility in the instigator that together can trigger actions that the instigator might not have otherwise felt compelled to undertake.

Without the TAM team approach, a security investigator could undertake a standard investigation interviewing coworkers, searching the instigator’s locker, and admonishing the instigator without knowing that the company human resources department had referred the instigator to a fitness for duty evaluation with a local psychologist. In such a case, the organization may be sending two messages to the instigator. On the one hand, he is likely to believe that he is being viewed as a criminal, while on the other, he is being told that the fitness for duty is intended to assess his suitability for return to work. One message may be perceived as confrontational and threatening, whereas the other may be viewed as collaborative and nonthreatening.

The instigator will likely consider the company to be double-dealing, insincere, and the psychologist to be simply trying to make a case for termination. With such a viewpoint, the instigator will be far less likely to be open to cooperative or therapeutic initiatives proposed by the company. He may also receive reinforcement for paranoid ideas that everyone at the company is “out to get him” and begin to add names to an internal list of people who deserve his retribution.

A key figure in the prevention of targeted violence is the psychologist who may be an active part of the TAM team or may assume other roles. Those roles and important considerations regarding those roles are discussed next.

The Role of the Psychologist in Threat Assessment and Management

Many experts in the field of workplace violence risk management suggest that mental health professionals, particularly psychologists, should be available as consultants to TAM teams.(5) Inclusion in this process acknowledges the necessity of having a better understanding of the mental status of the instigator, and the critical role that psychologists serve in acquiring and using this knowledge.

Psychologists are typically used by TAM teams in one of three capacities: background consultants, co-interviewers, and referral resources. In each capacity, the right psychologist can add value to the TAM effort by sharing their knowledge of mental illnesses, risk assessment, diversion techniques, and community treatment resources.

Background Consultant

As background consultants, psychologists are provided with investigative information. The TAM decision makers may benefit from insights drawn by the psychologist related to the likely mental status, possible future behavior of the instigator, and potential approaches that could be used to divert the instigator. Psychologists acting in this role are drawing on secondary sources of information, as they have no direct contact with the instigator. They are basing their advice on training and experience, combined with intelligence developed about the instigator. Their informed speculation can help guide the deliberations of the TAM decision makers.

Co-Interviewer

As a co-interviewer, the psychologist becomes a TAM investigator, typically partnering with a security professional to more directly assess the needs, motives, and capabilities of the instigator (for an excellent description of risks and benefits of interviewing instigators, see Calhoun & Weston [6]). Clearly, when employed as a co-investigator, the psychologist’s direct access to the instigator allows for a more comprehensive consideration of the instigator’s mental status. When practical, some interviewers (7, 8) may do this through telephonic interviews with the instigator, although face-to-face interviews must be considered a preferred—if riskier—methodology.

Referral Resource

TAM teams often find mental health professionals as useful referral resources. Psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers may provide psychotherapy for instigators, helping them to learn socially appropriate ways of directing and managing their hostilities. Professionals used in this capacity are acting as part of a diversion effort. Selecting the right doctor for this job is critical because TAM investigators will want to have a continuous dialogue with the professional. While all mental health doctors will release information with their patients’ consent, there is a considerable difference in the information flow obtained by a professional who has a comprehensive understanding of TAM needs, compared to the doctor who rigidly guards what he believes is in the best interests of the instigator/client. The TAM effort can be impeded by a mental health professional randomly chosen or selected just because an opening in the schedule exists.

Having referral resources responsive to TAM needs requires knowing the community and developing a list of cooperating professionals. It is essential to create incentives so that the professional will give priority to your request. In some communities, it can be weeks or months before professionals have openings in their calendars. We have managed to have professionals create space in their busy schedules by having the organization pay them directly their full rate, bypassing insurance programs. This makes payment easier for the professional, and billing at the full rate provides a supplement to the contracted and lower rate typically paid by an insurer.