P

Parking Area Crimes

Parking lots and garages represent a fruitful hunting ground for robbers, rapists, auto thieves, and purse snatchers. While often lucrative, they also represent a huge potential legal liability for operators, plus damaging publicity if pictured on the evening news in connection with a horrible crime.

Because of their layout and construction, there is no “one size fits all” security program for lots and garages. The keys to security are

To the extent that access can be controlled by the operator of the garage or lot, many criminals can be deterred or prevented from entering. This typically requires perimeter barriers such as fencing and/or walls at ground level. If walls and fences cannot be used, lesser demarcation of the lot boundaries with partial fencing, hedges, planters or shrubs, etc., can provide a psychological barrier to criminals and a clear indication of where the “private” property begins.

In many lots and garages, access to the garage can be controlled or closely monitored. A parking attendant can view the occupants of cars entering and leaving, and a closed-circuit television (CCTV) camera can record license numbers and drivers’ faces—both major deterrents to criminals.

The threat to persons and property in covered/enclosed parking garages can be very high. To limit access to garages, ground-level doors away from any parking attendant should not be accessible from the exterior of the building. There should not be any openings in the building walls within 15 feet of the ground through which a person could enter.

Isolated garage floors and garage and lot locations often make effective surveillance or monitoring difficult; however, live and recorded CCTV monitoring can reduce the risk (Note: If the CCTV cameras are not monitored live—and instead only recorded for later review and prosecution—prominent signage should state this so that customers do not rely on cameras which they think are being monitored and will produce immediate help).

When CCTV is used, good-quality color cameras that can operate in low light, along with high-resolution color monitoring/recording systems, are essential. Black-and-white monitors offer poor detail definition, a critical issue when attempting to identify suspects or potential problems.

Adequate lighting not only helps people recognize and avoid dangers, but also in many cases deters criminals by creating in them the fear of detection, identification, and apprehension.

Interior garage lighting should be a minimum of six foot-candles (measured both vertically and horizontally) throughout the garage, 24 hours per day. Sunlight seldom enters garage interiors and cannot be relied upon for lighting. If the facility has a significant history of crime or a recent history of violent crime, a higher level of illumination may be needed.

Energy-efficient metal-halide lighting provides reasonable color rendition for CCTV and direct viewing. Interior walls and ceilings should be painted with a glossy or semiglossy white paint to increase light reflection. This also increases the ability of parkers to observe movement and potential threats. Pillars and ramp corners should be painted in contrasting colors for driving safety.

Where appropriate, the use of a parking lot attendant can also serve as a powerful deterrent, if the attendant is able to view the lot and be seen. However, if there is no CCTV for remote viewing on large lots, and with the attendant’s booth facing out toward the street with his head often stuck in a book or portable TV, some attendants can’t see much of anything and don’t provide much, if any, security.

A key element of security in many surface parking lots is visibility, for employees, customers, and passers-by. Within the lot, trees and shrubs should not obstruct viewing. Tree branches and leaves should not be lower than 10 feet above the lot surface, and interior shrubs and bushes should not be higher than 18 inches above ground or curb so as not to obstruct vision or provide concealment for a robber or rapist.

A significant part of visibility is lighting. Lighting should enable parkers and employees to note individuals at night at a distance of 75 feet or more, and to identify a human face at about 30 feet, a distance that will allow them, if necessary, to take defensive action or avoidance while still at a safe distance. A minimum maintained illumination throughout open parking lots of not less than three foot-candles (measured vertically and horizontally) is recommended. This will also provide adequate illumination for driving purposes. Lighting at the entry/exit points should be at least 20 to 30 foot-candles for safety and security, and for adequate direct observation by employees or CCTV monitoring. Energy-efficient metal-halide lighting offers good color recognition.

Parking Lot Crimes and Other Problems

Use of the term “parking lots” does convey the nature of the problem to be addressed here, but more properly, the topic should be “Parking Environment Crimes and Other Problems” because not all parking is in “lots.” Parking environments are divided into three distinct parking facilities:

• Parking lots, which are outside surface parking areas, typically at grade level with the business or institution they serve, like the parking lots common around shopping centers.

• Parking ramps, which are typically multistory above-ground parking “garages” and may be

• Subterranean parking garages, which may or may not be part of an above-grade ramp complex.

Too few loss prevention practitioners, especially those at the store level, have an understanding of or an appreciation for the inherent risks in parking environments and how those risks impact on the retailer’s business. The security and LP industry concerns itself with two general areas of risks: crimes and torts which occur in the store’s parking areas. The impact of crimes in the parking areas, which really has no direct bearing on the nature of the retail business, is the victim of a crime, who, in our modern times, may commence a legal action against the retailer if the retailer has any control over or responsibility for the parking area. Civil lawsuits as a result of crime victimization in a store’s lot are commonly based on such theories as inadequate security or negligence in not providing sufficient security to prevent crimes, a condition which our society has come to expect when they park and walk in a store’s parking area. The second risk is the threat of crime (or other tortious conduct) may scare or drive away customers who will shop at other locations where the general perception is that it’s safer there.

Common Parking Lot Crimes

Crimes Against Persons in Parking Environments

2. Murder connected with spousal abuse

3. Murder connected with violence in the workplace

4. Serious injury to victim caused by an assault by an armed robber

6. Rape in the shrubbery/landscaping of the parking area or other remote areas of the parking complex

7. Abduction of a customer or employee

8. Armed robbery, no physical injury to the victim

9. “Mugging” (robbery) with injury

10. Purse snatching with injury to victim

11. Purse snatching without injury

13. Indecent exposure to female customers and employees

14. Assaults on car owners who accidentally come upon a thief entering or inside their auto

Crimes Against Property in Parking Facilities

2. Theft of auto parts, such as batteries, wheels, emblems, etc.

3. Theft of auto accessory or after-market equipment inside the vehicle

4. Theft of packages and other personal property from the interior of autos

5. Theft of equipment, supplies, materials, and tools from trucks

6. Vandalism to autos, such as “keying” a car or truck, puncturing/deflating tires, etc.

Victims may, and do, sue stores, and those victims who do not sue tend thereafter to shop elsewhere. And they certainly share the story of their victimization with many other people.

Courts across the land have universally held that parking environments are “inherently dangerous” because of the concentration of wealth in terms of property which is easily sold on the street and the sheer remoteness and isolated areas of such environments, with limited foot traffic. Further, the very nature of the environment is tolerant of lone males wandering among the cars, presumably “looking for” their own vehicle. But some are looking for victims or objects of theft.

Other Problems in Parking Environments

3. Solicitations for various causes

6. Teenagers or other unique groups who gather for social contact

An interesting example of “solicitations” took place in Los Angeles in the 1970s when a Muslim mosque became active in distributing its paper Mohamed Speaks, which then was a centerpiece of the Black Muslim community. Their efforts to distribute the newspaper were focused on the Crenshaw Shopping Center. The young men dressed in black suits, white shirts, and ties were universally well groomed and were passionate about their faith. The paper was free, but there was an air of expectation for a donation for the “free” paper, and many customers began to complain to store management that they felt intimidated by these young men and reported they were becoming too aggressive. The customers further informed management they would not return if something wasn’t done to shield them from the confrontations; they would shop elsewhere.

The security department was charged with gathering the necessary evidence to prove to the court the solicitors were threatening. Evidence was gathered and presented, and a restraining order was granted which denied these young men access to the parking lots. The problem was solved.

What Can Be Done at the Store Level?

Retail LP/Security practitioners aren’t expected to be experts in parking environment security, but there are some basic principles everyone should be aware of. Such basics include

• Parking areas must be well illuminated. Some daily/nightly effort should be taken to check the lights, and if a lamp is burned out, it must be reported and replaced.

• Exterior CCTV cameras, conspicuously mounted, should monitor the parking areas. They need not be monitored at all times, but they should part of a system which records the activity in the lot.

• We recommend signage in the lots which state, essentially, the area is monitored by CCTV for the safety of all.

• Large parking areas require some form of patrol by security personnel, either by foot or motorized. Vehicles used for this purpose should be distinctively and conspicuously marked and be equipped with some form of flashing light and voice communication equipment.

• A policy must exist wherein any “parking lot incident” is memorialized and maintained by LP personnel; i.e., if a sales associate reports her battery was stolen during her shift, that must be reported to LP and a report made and filed. Such incidents are just as important as is the report of a shoplifting detention.

• Monthly LP statistical reports should always reflect the number of parking lot incidents so the frequency of the crime is perpetually monitored (for corrective action if deemed appropriate or necessary).

• Every incident of a criminal nature that occurs in the parking area must be reported to the police.

• The store should have an after-dark “parking area escort service” if requested by a female customer.

• Female employees leaving the store at night, at either the conclusion of their shift or upon store closing, should be escorted to the employee parking area or required/encouraged to walk to the area in groups for their mutual safety.

• Designated employee parking areas must be illuminated as brightly as all other parking areas or, depending on geographical location, enjoy a greater level of lighting.

What Is the Store’s Role If the Parking Areas Are Not Specifically Under the Control of the Retailer/Store?

Let’s assume the store is in a mall, and the shopping center management is responsible for the common areas, including parking. Within reason, the store should nonetheless be aware of and concerned that the basic protection of the lots is in line with the points listed previously. We encourage an ongoing and regular meeting between store loss prevention and shopping center management, including the mall’s security director, to review and discuss security in the parking areas and known incidents of criminal attacks, as well as any other behavior or conduct of concern. Records of such meetings should be maintained by the store. The store is paying a common area maintenance fee for the overall management of the mall, including security, and is entitled to have a voice in making the parking safe for its employees and customers. To abrogate this responsibility is not only a moral failure, but could be construed as tortious, under certain circumstances.

Case in point: A medium-size retailer was a tenant in a large strip center. Doors to the store were on opposite sides of the selling floor; that is, one set of doors opened onto the interior of the mall, and the second set of doors opened onto the surface parking lot that surrounded the mall. Shopping center management was responsible for the maintenance and security of the parking lots.

One night two teenage girls entered the store through the parking lot doors. After shopping, they exited the store and entered their pickup truck, which was parked approximately 75 feet directly in front of the store. Several other vehicles were clustered in the same area. As the driver attempted to close her door, a man appeared, seized the door, forced his way into the cab of the truck, and drove the girls to a remote location, where he sexually molested them. A lawsuit was filed against the shopping center and the store for maintaining an unsecured and dangerous place to shop and inadequate security.

Upon examination of the lighting at the center, it was determined to be below the Illuminating Engineering Society’s minimum recommendations, hence inadequate. However, the store in question, upon recommendations made 5 years earlier by a security management consultant, had mounted extra lights to increase illumination in the immediate parking area outside the doors, shining into the lot. As a consequence, the suit against the store was dropped. The suit against the shopping center succeeded.

Performance and Development Review Process

When supervisory staff think of doing performance reviews, they often think of a time-consuming process and dislike the confrontations that often arise during the process. Those being evaluated sometimes view the process as one-sided and often see limited or no value in the process. There was a time in the not-too-distant past when it was acceptable for a retail loss prevention supervisor to do an employee’s evaluation, call the loss prevention employee into the office, have the employee read the evaluation, and then ask the employee to sign it. The employee had little or no input. It was little wonder the employee felt the process was one-sided. When done correctly, the performance evaluation process can be both positive and productive for both employee and supervisory staff.

The employee is often the most valuable resource in an organization.(1) The performance review process for a retail loss prevention organization should be designed so that it requires the employee and supervisor to work together at formalizing a plan to enhance the performance of the employee. Enhanced performance leads to greater job satisfaction for the employee and improvement in the organization’s performance. For that reason, the process should be more appropriately called a “Performance and Development Review Process.”

There are five main objectives in any effective performance evaluation process. They are

1. Evaluate performance since the last performance evaluation.

2. Recognize the areas where the employee has demonstrated strong performance.

3. Identify and address those areas where the employee needs to improve.

If everyone involved follows a step-by-step process, all five objectives can be successfully attained, and the employee, the supervisor, and loss prevention organization will benefit.

Benefits of an Effective Process

To get people, whether management, supervisors, or employees, to buy into any process, they have to see some benefit from it. So let’s start with the retail loss prevention employee.

A well-defined performance and development review process revolves around communication between the supervisor and the employee. The process will benefit the employee in two ways. First, it will benefit the employee by providing him with a clear understanding of what is expected and what needs to be done to meet those expectations.(2) During the process, the supervisor will discuss what specific performance factors the retail loss prevention employee will be evaluated on and what rating scale will be used. Second, it will also allow the employee an opportunity to discuss aspirations and get support and/or training needed to fulfill those aspirations.

The supervisor also benefits from the process in three ways. First, the process establishes a means for forming a more productive relationship with the retail loss prevention staff. Second, it provides an opportunity to clarify the expectations the supervisor has of the employee. Third, the process can provide a means to clarify the relationship between effective performance and the potential for promotions or merit increases.

The retail loss prevention organization stands to benefit in two important ways. First, the process will assist in identification of training and development needs to better enable employees to work toward the organization’s goals. Second, the process will assist in identification of employee potential so career development plans can be formulated. Many companies keep a list of where employees rank in the organization based on their evaluations. When opportunities for promotion open up, the evaluation results are weighed into the decision-making process. Third, the process can also serve as documentation in cases where employees are ultimately dismissed for poor performance.(3)

What Performance Gets Measured

Every employee position in the retail loss prevention organization should have a job description. The job description should detail the tasks the job holder is expected to undertake and how the job contributes to the overall mission of the organization. The Performance and Development Review form should define performance standards for the tasks associated with each employee’s job description. Therefore, the performance review factors will vary depending on the various tasks performed by the different occupations and levels of management.(4) The first line supervisor’s performance factors will differ from those of the loss prevention officer, the performance factors for the loss prevention officer will differ from those of the investigator, the investigator’s performance factors will differ from those of the secretary, and so on.

The factors used to measure performance should focus on results and be based on observable behavior. Action verbs should be used to describe the desired behavior. Table P-1 illustrates a few performance factors that could be used on a Performance and Development Review worksheet form for the loss prevention officer in a retail establishment.

Table P-1 Loss Prevention Officer Performance Factors

| FACTOR | TASK | RATING |

|---|---|---|

| JOB KNOWLEDGE | ||

| APPEARANCE | ||

| COMMUNICATION SKILLS | ||

| INVESTIGATIVE SKILLS | ||

| REPORT WRITING SKILLS |

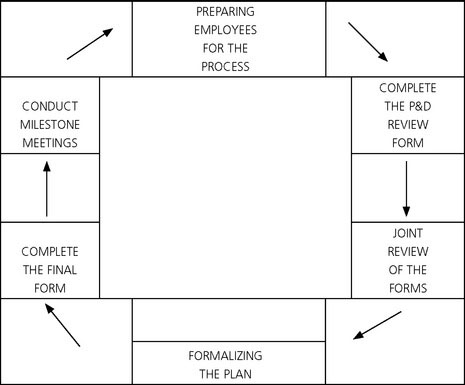

The Six-Step Performance Review Process

An effective Performance and Development Review process in a retail loss prevention environment is designed around a six-step process. Those steps are shown in a circular diagram (see Table P-2) because the steps must be taken in order, and like any process, it is ongoing. The process should be done every year or more often if needed, as each individual’s circumstances require. There will be more discussion on that part of the process later.

Table P-2 The Performance and Development Review Process

|

Step 1: Prepare Employee for the Review

The process should not be a surprise to the employee being evaluated. Contact the employee and arrange a time and date to meet to start the process. It is very important to make sure the supervisor keeps the appointment. Not keeping the appointment can send a signal that the process is not important.(5)

Give the employee being evaluated a copy of the Performance and Development Review worksheet. The worksheet will list the performance factors he will be evaluated on. If there will be any additional performance factors discussed in addition to the standard factors, they should be listed on the copy provided to the employee. Explain to the employee that he is to perform a self-evaluation on his performance during the period from his last evaluation forward to that date. In most cases, that time frame will be approximately 1 year. It should be explained to the employee that he will be rated on how he typically performs in the retail loss prevention environment, not how the employee performs compared to other employees.

Make expectations clear as to what the employee is to do with the forms. Encourage the employee to make notes on the form and write the rating somewhere near each performance factor. If a rating scale will be used, provide the employee with the rating scale. Review the rating scale to make sure the employee understands the definition of each rating. Keep the process simple by making the rating scale easy to understand. Table P-3 and Table P-4 provide examples of rating scales used by several organizations.

Table P-3 Example of Simple Rating Scale

| RATING | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| UNSATISFACTORY | CONSISTENTLY FAILS TO MEET EXPECTATIONS REQUIRED OF THE POSITION |

| NEEDS IMPROVEMENT | OCCASIONALY MEETS EXPECTATIONS BUT NEEDS TO DO SO MORE CONSISTENTLY |

| MEETS EXPECTATIONS | CONSISTENTLY MEETS EXPECTATIONS OF THE POSITION |

| EXCEEDS EXPECTATIONS | FREQUENTLY EXCEEDS EXPECTATIONS OF THE POSITION |

Table P-4 Example of Rating Scale with Points

| POINTS | RATING | DEFINITION |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | UNSATISFACTORY | CONSISTENTLY FAILS TO MEET EXPECTATIONS REQUIRED OF THE POSITION |

| 2 | NEEDS IMPROVEMENT | OCCASIONALY MEETS EXPECTATIONS BUT NEEDS TO DO SO MORE CONSISTENTLY |

| 3 | MEETS EXPECTATIONS | CONSISTENTLY MEETS EXPECTATIONS OF THE POSITION |

| 4 | EXCEEDS EXPECTATIONS | FREQUENTLY EXCEEDS EXPECTATIONS OF THE POSITION |

Once the process is explained to the employee, agree on a place, date, and time to meet again to go over the self-evaluation part of the Performance and Development Review form, as well as the form you will have completed. Be sure to allow at least 7–10 days for completion of the forms. To allow more time than that can result in procrastination on the part of the employee or supervisor. Sufficient time should be allowed for both the supervisor and the employee to do their evaluations without rushing through it. The key to this step in the process is educating the employee on the process and getting the employee to participate.

Step 2: Complete the Performance and Development Review Forms

Before starting the Performance and Development Review form, the supervisor needs to do three things. First, review the employee’s last performance review. Check to see if the employee has taken action to improve in the areas where improvement was needed. Check to see if the short-term goals listed by the employee have been achieved. Has progress been made toward long-term goals?

Second, the supervisor should review the incident file kept on the employee. Supervisors should establish an incident file for all retail loss prevention employees.(6) Some supervisors keep an employee journal where they make notations on specific events that involve the employee. The incident file or journal should contain both positive and negative documentation of the employee’s performance.

The incident file is very important. It provides the documentation to support the rating. Employees should be encouraged to also keep an incident file or journal. The employee should use it during the self-evaluation process. When they are reviewing information in the incident file, it is important that the supervisor and the employee are reviewing only the performance taking place since the last evaluation.

Third, the supervisor should review some of the most common problems encountered when conducting performance reviews. One common problem is rushing through the process. Do not wait until the day before the scheduled meeting with the employee to start completing the review form. Another common problem is evaluating personalities instead of performance. Be aware of your feelings toward each employee and avoid being biased. Refrain from using the word “weakness” when referring to a performance area where improvement is needed.

Now the supervisor is ready to complete the Performance and Development Review worksheet in preparation for the meeting with the employee. The worksheet will list the performance factors the employee is being rated on as well as the various task associated with that performance factor. The supervisor should rate the employee on each performance factor based on how the employee typically performed since the last review. If a point system is used in conjunction with the rating scale, the point total should be noted after each performance factor. If just the rating is used, note it after the performance factor. The supervisor should feel free to make notes on the form for support of the rating or for discussion with the employee. This form should be considered a worksheet. The final form will be cleaned up and not have all the notes.

If a point system is used, the points should then be totaled up and divided by the number of performance factors to produce an average rating. The overall average will indicate the employee’s overall performance rating. Tenths of a point should be rounded off on the scale as follows:

1. 49 and below = UNSATISFACTORY

1. 50 and above = NEEDS IMPROVEMENT

2. 49 and below = NEEDS IMPROVEMENT

2. 50 and above = MEETS EXPECTATIONS

A system may be used wherein each factor’s rating stands alone and there is not an average used. Many times the size of the retail loss prevention organization dictates the method used. The important point is not to get too hung up on the numbers game. The objective is to evaluate performance and communicate to the employee what he can do to make himself a greater asset to the organization. It is important to remember that the performance review process is about managing and improving performance in the retail loss prevention environment and not about completing forms (7)

The last item to complete prior to meeting with employee is the area where the supervisor will list first areas of strengths and then areas where improvement is needed. There should be two or three areas listed for each. The area where strengths have been demonstrated is listed first so it can be discussed first. You want to reinforce the positive performance before starting a discussion on what areas the employee needs to work on before the next performance review.

After completing the performance and development review form and prior to discussion with the employee, be sure to give consideration to the employee’s reaction to those ratings where there may be disagreement. Make sure you have proper documentation to support your rating for those areas that may generate unfavorable reaction by the employee. Disagreement usually results from the employee thinking he is meeting expectations when he is not. The performance and review process is designed to correct that situation.

Step 3: Joint Review of the Evaluation Forms

There are steps the supervisor can take to make the employee feel more at ease when the time comes for the employee and supervisor to meet for review of the Performance and Development Review forms. If possible, schedule the meeting in a conference room or location other than the supervisor’s office. It is important to have the meeting on neutral ground. The location should afford privacy and be free from interruptions such as telephone calls and other employees barging in. Cell phones should be put on vibrate and not answered unless there is an emergency. The process is important and should be taken seriously.

The supervisor should state the purpose of the meeting. It should be made clear from the start that only the performance and development review will be discussed during the meeting. There should not be any discussion of salary issues. If the employee has questions or wants to discuss salary issues, arrangements should be made to do so at another time. The focus of this meeting needs to be on the employee’s performance.

Start the process by reviewing the last Performance and Development Review with the employee. If the organization’s Performance and Development Review includes a place for goals, review them as well. Did the employee accomplish the short-term (1-year) goals? Was significant process made toward long-term (5-year) goals? Did the employee take the steps planned for improvement in the last review?

The supervisor should also explain to the employee that both will review each performance factor one at a time. Do not exchange the performance factor worksheets. That can be done later. Let the employee go first by asking what rating he assigned to the first performance factor. The supervisor should encourage the employee to explain how the rating was decided on. This is an excellent opportunity to let the employee talk about himself. The supervisor then explains what rating he gave for the same factor and why. The supervisor should avoid using the term “weakness” when pointing out an area where improvement is needed. Documentation should be used by both to support the rating in cases where a disagreement arises. As both parties work their way through the performance factors, they can make notes on their worksheets. The supervisor should let the employee do most of the talking. A lot can be learned by being a good listener in this setting. The supervisor will be responsible for keeping the focus on the task at hand.

When a performance factor is reached where the rating is UNSATISFACTORY or NEEDS IMPROVEMENT, there should be discussion by both the employee and the supervisor as to why that situation exists and what can be done to help the employee improve. This process is designed to open up communication between the employee and the supervisor. It is an excellent opportunity for both to clarify expectations each has of the other.

It is not all that unusual for the employee’s self-rating to be lower than the evaluator’s. When ratings are not close, there should be discussion to point out why that might be. Documentation kept in the employee’s incident file or journal should be referred to in an effort to support the rating. Once all the performance factors have been reviewed and the ratings on each discussed, the overall rating should be agreed on.

The supervisor and the employee should then review the two or three areas where each feels there has been strong performance demonstrated and where improvement is needed. Once again, let the employee go first. The employee should review the areas where he feels he demonstrated an area of strength. An example might be a loss prevention officer who feels investigative skills is an area of strength. The supervisor would encourage the employee to explain why he feels that way. The supervisor then reviews the areas he feels is an area of strength. It would not be unusual for the supervisor to have the same areas listed. The same process is followed with the two or three areas where each feels improvement is needed. These same areas should already have been discussed while working through each performance factor. Doing it again at this point sets the stage to formulate a plan for development of the employee. The important part of the exercise is for quality communication between the employee and the supervisor that will clarify expectations each has of the other.

Step 4: Formalizing a Plan

Now that the employee and the supervisor have identified two or three performance factors where the employee needs improvement, they can both put together a plan with a goal of raising the employee’s performance from NEEDS IMPROVEMENT to MEETS EXPECTATIONS. If the employee’s performance is rated at MEETS EXPECTATIONS or better in all performance factors, two or three areas can still be picked where the employee can strengthen the MEETS

EXPECTATIONS performance or elevate it to the EXCEEDS EXPECTATIONS level of performance.

The plan developed by the employee and supervisor should include actions that can be implemented by both and designed to improve the employee’s performance in each of the specified factors. Those actions should be measurable so that each can review the plan during the course of the year to make sure a sincere effort is being made and the employee’s progress is on track for improvement. An example of development actions that can be implemented are as follows.

The Loss Prevention Officer is rated NEEDS IMPROVEMENT in the area of Job Knowledge. The plan could require the employee to take training related to increase job knowledge in retail loss prevention, either in-house or through an outside agency (college or career training institution). The supervisor’s commitment to the plan would be to locate retail loss prevention training that is available, secure funding for it, and/or arrange time in the work schedule for the employee to attend the training. The expected actions of each are measurable and easy to monitor for progress.

If the performance and development review process in place has a section for short-term and long-term goals, they should be discussed at this time as well. Both the short-term (1-year) and long-term (5-year) goals should be career-related goals that the employee hopes to accomplish. Examples of short-term goals would be to attend some specialized loss prevention training of personal interest to the employee or complete the last couple of classes needed for degree work at a college. Examples of long-term goals might be to get promoted to a supervisory position or complete work on a master’s degree. The supervisor can play an important part in assisting the employee with both short-term and long-term goals. This area is also important for the development of the employee.

Once this portion of the process is completed, the supervisor should explain to the employee that he will be transferring the results of their review, with their plan for improvement, onto a final Performance and Development Review form. It is that final form that goes into the employee’s Personnel File and gets forwarded to the human resources department. A date should be agreed on for the supervisor to meet back with the employee for the employee’s review of the finalized form. The supervisor should allow sufficient time prior to the next planned meeting date for completion of the final form. This is also an excellent opportunity to seek comments from the employee on his thoughts about the performance review process.

Step 5: Complete the Final Form

Now that the meat of the performance review process has been completed, the plan agreed upon by both should now be transferred from the worksheet to the final form that will be filed with the human resources department. A copy of the completed form will also be placed in the employee’s personnel file. The final form can take whatever design the organization chooses to use. It should be typed or computer-generated so it is neat and legible. The supervisor should meet with the employee again and allow him to review the final form.

The final form should contain the following information:

• All the performance factors reviewed should be listed. There should be a space next to each factor for the employee’s rating and a space for supporting comments for that rating. (See Table P-5 for an example)

• The form may have a place for the employee to list short-term and long-term goals.

• There should be a section of the form reserved for the employee to add his plan for improvement in those factors agreed on, as well as a section for the supervisor to add what actions will be taken to assist the employee in his improvement efforts.

• The form should have a section that will allow the employee to write in his comments about the performance review process. This area will also be where the employee can add comments if he disagrees with any ratings and why.

• There should be a place for the employee and the supervisor to sign and date each page of the form.

Table P-5 Example of Performance Factor Section on Final form

| PERFORMANCE FACTOR | RATING | SUPPORTING COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|

| DECISION MAKING | MEETS EXPECTATIONS | Makes sound decisions based on utilization of all information available at the time. Will seek advice of others before making decisions. |

| CARE OF EQUIPMENT | EXCEEDS EXPECTATIONS | Keeps equipment in excellent condition. Orders equipment when needed. Updates inventory in timely manner. |

| COMMUNICATION SKILLS | MEETS EXPECTATIONS | Communicates effectively with public and other loss prevention officers. Utilizes correct grammar in oral communication |

The employee should be given a copy of the completed, signed form. The supervisor should attach his worksheet used to his copy of the final form and place it in the employee’s incident file. It will be used as a reference during the course of the next review period and when training opportunities arise.

Step 6: Conduct Milestone Meetings

“Milestone meetings” should be arranged periodically throughout the year to review the retail loss prevention employee’s progress at reaching goals and taking steps agreed upon to improve performance. Ideally, the milestone meetings should take place quarterly or at a minimum of twice a year. The meetings do not need to be of a formal nature but should be documented by the supervisor. The meeting can be done over a cup of coffee or during a visit with the employee in the supervisor’s office. The important aspect of conducting the milestone meetings is to let the employee know you take his development serious enough to check on his progress. It also affords an excellent opportunity to monitor training agreed upon or for the employee to discuss any new concerns or problems he might have.

Summary

Conducting performance appraisals can be productive for both the employee and management in any retail loss prevention organization if they are thought of as a developmental tool. The time the employee and supervisor spend together to review the employee’s performance should provide an excellent opportunity for both to communicate and clarify expectations each has of the other. This is especially important in the retail environment where performance directly affects the organization’s bottom line.

Performance appraisals or evaluations should be done as often as needed and at least once a year. They should be a review of the employee’s performance since the last appraisal or evaluation. Some keys to the process would be for the supervisor to explain it to the employee; encourage participation from the employee; review and evaluate performance, not personality; and document positive performance as well as negative performance. Effective performance and development reviews are part of a continuing process all retail loss prevention organizations should be using to increase the value of the most important asset—their employees.

(1) Sachs R.T. The productive appraisal. New York: American Management Association, 1992.

(2) Fisher M. Performance appraisals. London: Kogan Page Limited, 1996.

(3) Sachs R.T. The productive appraisal. New York: American Management Association, 1992.

(4) Fisher M. Performance appraisals. London: Kogan Page Limited, 1996.

(5) Fisher M. Performance appraisals. London: Kogan Page Limited, 1996.

(6) Fisher M. Performance appraisals. London: Kogan Page Limited, 1996.

(7) Fisher M. Performance appraisals. London: Kogan Page Limited, 1996.

Pharmacy LP Investigations

Introduction

The operation of a pharmacy is one of the most complex businesses in retail. The pharmacy provides critical patient care that requires a special level of customer service. Customers visiting a pharmacy are comforted by seeing the same pharmacists and drug technicians because this is truly a relationship business. While the customer’s interaction is brief, the operation, as a whole, is a complex machine that is full of opportunity for shrinkage and theft.

For the loss prevention practitioner, the pharmacy can be an intimidating and even unfriendly place to work. My observations over the years is that knowledge of the operation, and therefore knowledge of the causes of shrink, can be gained only by being immersed in the pharmacy itself. Some loss prevention department staff are required to become certified pharmacy technicians in an effort to familiarize them with everything from the filling process to potential drug interactions. It is a highly technical business that is closely regulated by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). It is a business of trust that a customer builds with the pharmacy staff. Most importantly, it is a business that cannot afford mistakes in the prescription filling process. Misfilling a prescription can be extremely harmful to the patient and could ultimately cause death.

What is important to understand about pharmacy shrinkage is that the traditional areas for loss are comparable to other retail sectors, but there are many more additional opportunities for shrink through insurance accounting issues, returning expired drugs for credit, acquisition costs of pharmaceuticals, LIFO inventories, and an endless list of other, more subtle areas. With the pharmacy of a typical drug store generating about half the sales of the entire store, shrinkage is critical from a financial standpoint. The twist that makes shrink wholly different in this case is that the shortage could be medication.

The true depth of internal thefts is unknown but pharmacy shrink is comparatively low to the rest of the store. Beneath the surface of that shrink, though, lies an unfathomable thirst for pharmaceutical narcotics bought on the street. In 2005 a Reuters report cited the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University survey that showed that more Americans were abusing controlled substances than cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, and heroin combined. According to that same Reuters article, the number of prescription drug abusers doubled from 1992 to 2003 to nearly 15 million.

A 100-count bottle of OxyContin 80 mg (street named Oxy’s, OC’s, Killers, Poor Man’s Heroin, and Hillbilly Heroin), the brand name of a powerful prescription pain medication, has an average street value of about $8,000, or $80 per tablet. A 500-count bottle of hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/500, the generic name of another prescription pain medication with multiple brand names, the most common being Vicodin, has a value of ab out $2,500, or $5 per tablet.

Auburn University’s Harrison School of Pharmacy conducted a study in July 2004 that reported approximately 10% of pharmacists become chemically impaired at some point in their professional career. The University of Georgia in 2002 reported that 40% of the pharmacists they surveyed voluntarily admitted to taking a regulated prescription substance without a prescription, and 20% admitted to repeated use.(1)

Loss prevention’s role in the investigation of drug loss due to theft is a highly specialized combination of art and science. Shrink causation as a whole is deeply rooted in accounting and may not be ascertainable only at the store level. Shrink reduction in the pharmacy must be attacked from a corporation standpoint and not left to the imagination of only those at store level.

The Growing Addiction Problem

It is estimated that 8–12% of healthcare workers have substance abuse problems. Furthermore, 11–15% of pharmacists, at some time in their career, are confronted with alcohol and/or drug dependency problems, and the median age of recovering pharmacists is 43 years.(2)

Drug abuse has become a national health epidemic among young people. Diverted pain medications are widely sold across the United States and are second only to marijuana in illicit sales. The quantity of pharmaceuticals diverted through theft from legitimate sources, particularly pharmacies, is approximately 6.8 million dosage units (excluding liquids and powders) each year.(3)

According to the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, approximately 3 million persons aged 12 or older had used OxyContin nonmedically at least once in their lifetime. This is a statistically significant increase from the 2.8 million lifetime users in 2003.(4)

A questionnaire about OxyContin was included in the 2006 Monitoring the Future Study for the first time. During 2005, 1.8% of 8th graders, 3.2% of 10th graders, and 5.5% of 12th graders reported using OxyContin within the past year. During 2004, 1.7% of 8th graders, 3.5% of 10th graders, and 5.0% of 12th graders reported using OxyContin within the past year.(5)

During 2004, 2.5% of college students and 3.1% of young adults (ages 19–28) reported using OxyContin at least once during the past year. This is up from 2.2% and 2.6%, respectively, during 2003.(6)

Primer on Controlled Drugs

A controlled (scheduled) drug is one whose use and distribution is tightly controlled because of its abuse potential or risk. Controlled drugs are rated in the order of their abuse risk and placed in Schedules by the Federal Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

• Schedule I: Drugs with a high abuse risk. These drugs have no safe, accepted medical use in the United States.

• Schedule II: Drugs with a high abuse risk, but also have safe and accepted medical uses in the United States. These drugs can cause severe psychological or physical dependence. Schedule II drugs include certain narcotic, stimulant, and depressant drugs.

• Schedule III, IV, or V: Drugs with an abuse risk less than Schedule II. These drugs also have safe and accepted medical uses in the United States. Schedule III, IV, or V drugs include those containing smaller amounts of certain narcotic and non-narcotic drugs, antianxiety drugs, tranquilizers, sedatives, stimulants, and non-narcotic analgesics.(7)

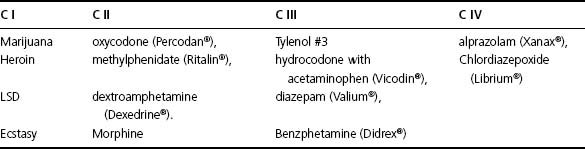

There is not a state or federal requirement that a pill-to-pill perpetual inventory be kept of all narcotics. Narcotics are grouped by class of 2 through 5 and are represented as here: CII, CIII, CIV, CV (see Table P-6). CII drugs are the most addictive and are generally pain medication. All drugs are regulated by the DEA, but CII is the only drug class that the DEA closely regulates and monitors as far as ordering and dispensing. OxyContin, as mentioned previously, is a CII.

Theft of Controlled Drugs

Basic Pharmacy Inventory

Drugs, just like clothes on a rack, are simply merchandise items as far as inventory accounting is concerned. Pills come from the manufacturer in bottles of 100 or 500 or even 1000, and liquids are usually shipped in bottles containing 480 milliliters (1 pint) or 960 ml (2 pints).

Controlled drugs are on the shelves with the other drugs and are in alphabetical order. There is not a federal or state requirement to keep the CII drugs under lock and key; therefore, they can be dispersed (kept on the shelves). Retail chains will generally maintain the CIIs under lock and key, but that is a company requirement and not a mandate by administrative order. Dispersing the CII drugs has a distinct advantage when considering loss mitigation against burglary or robbery. If kept in a locked drawer, all the most theft-prone drugs are simply in one place. There are specially made drug safes, but they are normally used in hospitals and require dual control. These are simply impractical for a pharmacy due to its size and the staffing requirements needed to manage its use.

The inventory replenishment/ordering is fairly basic: Each drug has a specified quantity on the shelf that is based on the volume of sales for that item. As prescriptions are filled, the physical and book inventory are decremented. When that quantity meets a specified threshold, more is ordered (automatically or manually) to replenish the stock. It is the common min/max concept. In a perfect world, it would be a perfect system.

Most drugs have a “name brand” product and a generic equivalent. As an example, Ritalin© is also sold under the generic as methylphenidate. While both are chemically the same, generic brands are manufactured by various companies and are generally less expensive than the name-brand product. Some insurance plans will not allow dispensing namebrand products if a generic is available, so doctors must designate that the prescription be “dispensed as written” or DAW.

The significance of this basic environment (brand versus generic) is that it allows for the appearance of shortages when in actuality one was probably substituted for another. These false variances would only cause investigative time to be spent needlessly. There are times when pharmacists change the prescribed medication to generic because the name brand is out or the customer’s insurance plan will pay only for generic and the doctor wrote for name brand. This is a common practice, but once the prescription is entered into the computer for generic, the inventory will be adjusted accordingly. If the record is not changed in the pharmacy system to properly reflect the correct medication dispensed, it will create “paper” variances. These factors and others make the detection of theft extremely challenging. Without an internal or commercially available inventory variance software, identifying theft is nearly impossible. As with any enterprisewide system, it would be impossible to investigate all shortages that are detected by a variance software. This truly creates an investigative process that deals with only “high” variances that surpass a certain threshold. Defining “high variance” is different for nearly every store.

Once Filled

Once the prescription is entered into the computer, the medication is removed from the shelf and staged for the pharmacy tech or pharmacist to fill. The prescription is filled, bagged, and placed in a “will call” bin. This process can be repeated as many a 1,000 times a day or more, and in the 24-hour stores, it’s repeated at all hours.

From an inventory accounting standpoint, the filled prescriptions are still considered to be in the physical inventory and are not relieved from inventory until they are rung through a register. Ideally, this would be accomplished through a bar-coding system of the bag’s label that was created by the pharmacy system. When the register transaction is completed, the inventory is relieved. This creates an end-to-end transaction process. This, too, depending on the system, assists in maintaining a proper stock amount so that the pharmacy does not run out of that particular drug.

Point of Sale

The final step of the sales process is at the register. This point provides the means to use subterfuge to pass stolen drugs and, more frequently, presents the opportunity to fail to properly record a transaction and steal cash. The cash register is an enormous point of theft of cash because the sales are predominantly insurance co-pays that are even dollar amounts such as $10, $20, etc. Prescription bags have large labels attached to them which include literature for the drugs. Customers would not be suspicious of not receiving a register receipt and, as such, the cashier would not need higher level math skills to manipulate a register. The No-Sale function on a pharmacy register can prove to be disastrous if not properly managed.

Register manipulations through voids of any kind and refunds are equal opportunity offenders. Refunding a prescription is rare, but the highest dollar merchandise in the store can be found near the pharmacy. Cash register exception reporting must be fine-tuned for the pharmacy. The number of transactions is much lower than the front end, but they are, by average, much higher average transactions. A successful search for theft tracks can be accomplished only if the pharmacy sales transactions are separated from the rest of the store. Their transactions are unique and would skew any reporting system if included within the store as a whole.

Many POS systems are tied to the pharmacy dispensing system to maintain an accurate perpetual inventory. Rigorous enforcement of policy and procedure will always act as a deterrent. However, work flow in a pharmacy tends to break down those standards during peak pickup times. This is especially true in high-volume pharmacies.

Return to Stock

The desired final destination for all filled prescriptions is in the customer’s hands. Surprisingly, many prescriptions are never picked up, and the medication must be returned to the shelves. This process is accomplished through the pharmacy management system to correct the inventory accuracy. The actual bottle or vial is placed back in the location from which it was filled and can be used again to fill later prescriptions. It is a violation of law to combine the contents of a returned prescription with the contents of what is on the shelf. The shelf contents may have a different manufacturer or a different lot number, and therefore the vial or bottle is placed on the shelf. This practice allows for easy monitoring of how return-to-stock procedures are being handled. If there are no containers on the shelves from previously filled prescriptions, then the contents are being mixed.

The shrinkage and theft opportunity here is that a person can indicate that the prescription was returned to the shelves and then actually steal it. Again, this will create a variance in the system but does little to point an investigation in the right direction. Additionally, as with all theft, detection is severely limited if the subject steals small amounts of drugs at a time.

Drug Diversion Investigation

Stealing drugs is just a variation of a old theme. Whether with narcotics or some other medication, the pharmacy business is no different from any other retail sector as far as theft is concerned. The primary concerns are as follows:

1. Theft can be of a filled customer’s prescription, either partially or in total.

2. Fictitious or forged prescriptions can be created, and the drug is then either passed or actually paid for at the register.

3. The automated or manual ordering system can be overridden to bring in more drugs than the order should be.

4. Large quantities of drugs are purchased through a licensed pharmacy and sold on the street. Part of the proceeds are used to purchase more drugs, and the rest of the money must be laundered through shell companies or other cooperating pharmacies. This is a multimillion dollar enterprise.

Diversion as described in point 4 is large-scale fraud. It is as pervasive as the trafficking in illicit drugs, and there is no centralized database that can be tapped into either on the state or federal level that would assist investigators to be proactive. Investigations begin through normal law enforcement activity and audits conducted by the DEA and State Boards of Pharmacy. Retail pharmacy chains have a great deal of exposure if diversion occurs within their stores. For that reason, operations and loss prevention must work hand in glove to properly monitor and investigate unusual drug movement. That is not to say that large pharmacy cases do not exist, but they are the exception and not the rule. Diversion of “small” quantities for sale will be the primary topic here.

It should be stated that diversion can occur with any drug and it does not necessarily have to be sold on the street. Drugs can be diverted to a privately owned independent pharmacy to be sold to defraud Medicare. A pharmacist who normally works at a hospital and is diverting drugs there can use the retailer’s pharmacy as a method of replacing those stolen.

Second, there is theft of narcotics for personal use due to addiction, also known as “impairment.” A percentage of healthcare workers are addicted to narcotics to which they have access. In the sense that theft is theft, there are some extenuating circumstances that should be discussed.

The scenarios are endless, but the major areas of vulnerability are fairly common. How could there be so much vulnerability in an area of such confined space? The truth is that the confined space adds to the opportunity for theft. A pharmacy, during high traffic times, is a beehive of activity with little time to notice the behavior of those around you.

Discovery Phase

Identification of potential drug loss is really simple inventory math. In its most basic description, the suspect must order more drugs than is being used to fill prescriptions. Diversion on a large scale is rare in a chain drug store because of the monitoring that takes place. Unusual ordering activity, P&L book inventory values spiking, and other areas might also give some insight to operations. Being able to detect a problem across numerous stores or across an entire chain would be impossible without software monitoring.

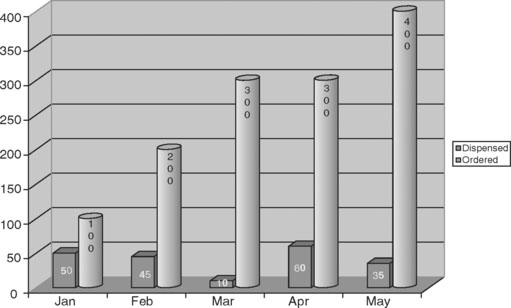

Following is the typical scenario that initiates an investigation. This is a generalization as every company has different methods to order drugs: A pharmacy orders two bottles of Drug A. The bottles contain 100 tablets each. The order can be entered manually through a handheld device, or it can be ordered through an automated replenishment system. Its source can be a company distribution center or an outside vendor. Two bottles of 100 tablets are sent to the store, where it is received and placed on the shelf. Over a period of time, the pharmacy fills prescriptions that equal 100 tablets. In a perfect scenario, there would be one bottle of 100 left (see Figure P-1). Either through auto replenishment or through manual orders, more bottles are ordered. To successfully steal drugs, the normal order quantity must be overridden in the system. Over time the number of bottles (or number of dosage units, in this case tablets) ordered begins to exceed the amount needed for filled prescriptions. A data mining program would begin to alert the investigator that the pharmacy was experiencing ordering activity that was not justified for the number for actual prescriptions. According to a report, over the period of time reviewed, the pharmacy had ordered 13 bottles (1300 dosage units) and had dispensed only 2 bottles (200 dosage units). Again, in our sample case, there should be 11 bottles of tablets on the shelf. A visual inspection of that specific drug reveals there are only 2 bottles. The next phase of the investigation begins.

Investigative Phase

Pharmacy drug loss investigations are initially highly confidential because the number of potential suspects includes anyone who has access to the pharmacy or who can potentially gain access to the pharmacy. The one saving grace of these types of investigations is that if the suspect is a pharmacy employee, the thief is usually going to be the person who is overriding the internal systems replenishment process. However, even with that group narrowed, it is unknown as to how the drugs are leaving the pharmacy. This could involve accomplices, multiple suspects, or outside vendors. Carrying out one bottle of pills is fairly easy to do on your person, especially if the pills are no longer in the bottle. Diverting large quantities may present a challenge but may be overcome by simply using the mail or commercial carrier to ship them home.

Once a loss has been determined, the DEA must be notified in writing within 1 business day. This can be accomplished by faxing a simple memo to the local DEA office regarding the initial reporting of a loss. Further investigation would be needed to confirm the actual loss. The DEA has very stringent administrative policies regarding loss reporting, but unless it is a special circumstance, the agency will not become actively involved. Every state also has a State Board of Pharmacy that regulates the licensing of the pharmacists and the pharmacy itself. The reporting requirements vary for each state, but, in general, there is no requirement to inform them of any investigation. However, it is a good practice to do so.

Narrowing the scope of the investigation to an individual takes a thorough review of store-level paperwork, schedules, or through any technological means. Again, the sensitive nature of the investigation generally prohibits the usual hands-on investigative techniques at the outset. Unless a trusted individual is cooperating with loss prevention, a great deal of work must be done before store opening or after store closing. To reinforce the sensitive nature of the investigation, a confidentiality agreement can be requested of any assisting employee. Breaking the confidentiality agreement would result in termination.

CCTV is almost paramount, and it may require multiple cameras. The layout of the pharmacy makes camera placement difficult, as an overhead view of the target drug severely limits view. Theft of one bottle of pills from shelf to pocket takes 2 seconds, but there is no need to review video unless there is a known shortage. This will required frequent, if not daily, reconciliations of that drug to determine if there is a shortage.

Investigative Scenario

Whether detected by automated means, audit, or tip, the investigative process can be very long. However, with proper preparation, these cases are likely to last no more than a few weeks.

When surveillance is begun, there is a period of time when it requires total confidentiality. Operations staff should be notified, however, because they may have to escort you in to the pharmacy during nonoperating hours. A licensed pharmacist must be present if you are entering the pharmacy. Entering the pharmacy is key obviously to physically recording the on-hand count of any targeted drugs. Using an automated system allows decisions to be made as to where to position a camera(s) to get the most likely theft.

The difficulty of these investigations is confirming a loss. An actual pill/liquid count is generally not necessary, as the theft usually involves full bottles. Nonetheless, it requires surveillance to determine where suspicious activity is occurring. In the multistore environment of retail drug establishments, there is not always the luxury of having stores closely clustered together. Pharmacies at great distances from the investigator’s home may require a revised approach to complete the investigation. Retrieval of video may be an issue if a DVR is used. Using time-lapse VCR may be of more benefit if the investigation is being assisted by a member of store management.

If the amount of stolen drugs is high, it is very likely that that local authorities or the DEA will be involved. There may be requests to allow the thefts to continue to occur while their criminal investigation proceeds. This should obviously be reviewed by a corporate legal department.

Apprehension Stage

Closing out an investigation can occur with or without an apprehension. In both instances, several administrative items must be concluded.

If a company employee is apprehended, the usual internal steps should be taken regarding evidence and statements. Prosecution has several variations that are of interest. Drugs are generally inventoried at cost and may be converted to retail for physical inventory purposes. This sometimes presents a challenge to local authorities as to how to assess value. This is important because most jurisdictions will charge the individual with theft because there is no statue that provides for illegally taking of controlled drugs. This truly points out the value of having the DEA or State Board of Pharmacy involved even if just as an advisor. Those agencies can assist in the proper framing of criminal charges if necessary. In the case of a pharmacist and in some states a drug tech, the State Board of Pharmacy will hold an administrative hearing to determine the fate of the offender’s license. More importantly, the state can sanction the license of the store’s pharmacy too and levy a fine against the company. While the pharmacy’s license could be revoked, it would be extremely rare in a chain drug store.

If a good relationship exists between the investigator and law enforcement, loss prevention should be allowed to complete the internal investigation. This allows the company to fulfill all obligations to protect company assets and at the same time still provides law enforcement with a prosecutable case. Collaboration is the key to successfully investigate any drug loss.

Drug Testing and Polygraph as an Investigative Tool

Because narcotics are involved, there are two additional investigative avenues afforded: drug testing and polygraph. Despite common belief, the use of the polygraph is still viable. The Employee Polygraph Protection Act of 1989 allows pre-employment and investigative use of polygraph. This is a thorny subject. Policy and procedure for its use should be well planned and distributed to all employees. There should be a formal review process in place that includes the legal department and loss prevention senior management for requesting the use of polygraph. It is recommended that the polygraph request is presented to the employee in writing. That request should outline why the examination is being requested and should outline both company policy and the Employee Polygraph Protection Act of 1988 (EPPA) for the employee’s review. The employee should be allowed to keep a copy of this document as well. If considering the use of polygraph, keep in mind that neither refusal to take the polygraph nor the results of the polygraph can be used solely as justification for termination. The polygraph is simply a tool within the totality of the investigation. It has been my experience that it is rare when an employee actually appears for the process.

Note: While we believe the polygraph is a valuable investigative tool, as noted in the preceding text, the nuances of the EPPA are many and complicated, and the penalties for violation of its provisions can be severe. Therefore, before any mention of the use of the polygraph is made during an investigation, we strongly suggest competent legal counsel be consulted. CAS/JHC.

Employee Polygraph Protection Act(7)

Prohibitions

Employers are generally prohibited from requiring or requesting any employee or job applicant to take a lie detector test, and from discharging, disciplining, or discriminating against an employee or prospective employee for refusing to take a test or for exercising other rights under the act.

Examinee Rights

The act permits polygraph (a kind of lie detector) tests to be administered in the private sector subject to restrictions, to certain prospective employees of security service firms (armored car, alarm, and guard), and of pharmaceutical manufacturers, distributors, and dispensers.

The act also permits polygraph testing of certain employees of private firms who are reasonably suspected of involvement in a workplace incident (theft, embezzlement, etc.) that resulted in economic loss to the employer.

Drug Testing

Drug testing can also be employed, but it must comply with the Federal Workplace Drug Testing Guidelines. If a drug test is conducted for a pharmacy investigation involving personal use or addiction, it is recommended that the test be administered after the investigation target has been on duty for a few hours. Most companies have very clear drug testing policies, and retail drug chains have fundamental policies and procedures firmly in place. Those policies will generally state that failure to submit to a drug test is basis for termination. Due to the nature of the test, it will be unannounced, and proper relief of staff is critical to maintain the operation of the pharmacy. If an employee refuses to submit to a drug test, there should be sufficient policy in place to seek termination.

Confirming the Loss and Conducting an Audit

Regardless of the end result of the investigation, an inventory is recommended for all controlled drugs at the conclusion of the internal investigation. This should be done for two reasons:

There are variables as to how the inventory is performed to ensure that the pharmacy’s record keeping is in compliance. There is somewhat of a Catch-22 with this process, however. By law, the initial loss was reported to the DEA and possibly the State Board of Pharmacy. They can accept your internal inventory results or conduct independent audits of their own. The State Boards of Pharmacy have the power to adjudicate any violations of record keeping found during an audit. Even though their audits were initiated by the company itself, penalties such as fines can be assessed. Obviously, if a pharmacist is involved, the board will take action against his license.

This is truly an end-to-end investigation that provides a paper trail and a reconcilable inventory to determine exact loss. These cases require extreme patience that may even dictate that thefts are allowed to occur to expand the investigation as needed.

Forged Prescriptions(8)

Signs to aid in the detection of fraudulent prescriptions: Forged prescriptions are a significant problem for today’s pharmacies. Pharmacists should be aware of the various kinds of fraudulent prescriptions which may be presented for dispensing:

• Legitimate prescription pads are stolen from physicians’ offices, and prescriptions are written for fictitious patients.

• Some patients, in an effort to obtain additional amounts of legitimately prescribed drugs, alter the physician’s prescription.

• Some drug abusers will have prescription pads from a legitimate doctor printed with a different call-back number that is answered by an accomplice to verify the prescription.

• Some drug abusers will call in their own prescriptions and give their own telephone number as a call-back confirmation.

• Computers are often used to create prescriptions for nonexistent doctors or to copy legitimate doctors’ prescriptions.

Characteristics of Forged Prescriptions

1. The prescription looks “too good”; the prescriber’s handwriting is too legible.

2. Quantities, directions, or dosages differ from usual medical usage.

3. The prescription does not comply with the acceptable standard abbreviations or appears to be textbook presentations.

4. The prescription appears to be photocopied.

5. Directions are written in full with no abbreviations.

6. The prescription is written in different color inks or written in different handwriting.

Theft and the Impaired Pharmacist

Impaired pharmacists are no different from any other person with an addictive disease. The addiction may start with taking pills to take the edge off the day or to help with backache from standing all day. Taking the drugs may initially be circumstance driven, but then the drugs may be taken in anticipation of the original problem. As the body increases its tolerance, larger doses or more powerful drugs are needed to obtain the same effect. The early stages are difficult to detect unless it involves CII drugs, as there is a requirement of perpetual inventory on these.

These types of thefts are long term, however, and the loss begins to accumulate. The pharmacist or drug tech knows that continued abuse of one specific drug will eventually be detected, so he begins stealing a variety of drugs that deliver the same effect. A unique factor to the investigation of impairment thefts is that some pharmacists “float.” They are not assigned to a specific store, or they act as part-time pharmacists who are called in for staffing reasons. These are absolute moving targets who take advantage of the variety of stores they work. Now the situation is complicated by a person stealing multiple drugs and multiple locations. However, once a possible suspect is identified, that person can be moved to one store for surveillance purposes.

Narcotics, specifically pain medication, are the most abused type of drug. Whether liquid cough syrups with codeine or heavy pain management pills such as Vicodin or OxyContin, the theft methodology is fairly consistent. Drugs must be brought into the pharmacy by any means available and then be hidden or must be removed from the pharmacy as quickly as possible. Liquids are often drunk directly from a bottle and then placed back on the shelf. The consumed liquid is then replaced by adding distilled water to the container. This practice creates an obvious health risk for patients.

The impaired pharmacist has a disease that cannot be addressed through awareness meetings or poster campaigns. These individuals need professional help and, like most addicts, are reluctant to come forward to get the help they need. Their biggest fear is that their license to practice pharmacy may be in jeopardy. Pharmacies should have available the phone numbers of the state’s impaired pharmacist hotline so they can get immediate help. One of the primary organizations that deal with pharmacist rehabilitation is the Pharmacy Recovery Network (www.usaprn.org). The success rate for many of the PRN programs is as high as 85%.

Understanding addiction as a disease will help the loss prevention professional a great deal in this industry. This is somewhat of a learning curve for those coming from other types of retail. The interplay between the theft of narcotics and the need to satisfy an addiction is important to understand. An impaired pharmacist may seek medical treatment on his own, and it may be through that process he will divulge the amount of drugs stolen. Even though the pharmacist stole from the company for his own use, restitution may be the final outcome. In short, a pharmacist may be allowed to enter into a rehabilitation program, make restitution for the drugs stolen, and be returned to work upon successful completion of treatment.

This situation is not to be confused with a theft investigation whereby the offending pharmacist is identified and apprehended. There is no “get out of jail free” card for the pharmacist by announcing that he wants to go into a rehabilitation program after he has been caught. Theft cases are handled just as any other.

Reinstating an impaired pharmacist is not as problematic as you might think. Every state has special programs legislated for health professionals with addictions, where the treatment is rigorous and the penalty for relapse is the possibility of permanent loss of license to practice. While the risks are high, the rewards are substantial, as these highly successful state-sponsored programs allow professionals to regain their health and their careers.

These voluntary programs, paid for through health professional license renewal fees, operate on the same basic requirements in each state. The health professional undergoes detoxification before signing a contract agreeing to 3 years of monitoring and random drug tests between 3 and 10 times each month. Weekly group therapy meetings, regular sessions with an addiction physician, at least three 12-step meetings per week are also required. The patient also identifies a sponsor and a work-site monitor.

Approximately 95% of participants in state health professional recovery programs remain sober for at least 5 years, which is a remarkable success rate, especially when compared to other treatment programs that display relapse rates of 66% or higher.(9)

Additionally, reinstatement is a sound business decision because, quite simply, there is a shortage of pharmacists. If the retailer did not reinstate the pharmacist, the pharmacist would certainly work for another company. It is an issue of supply and demand.

Conclusion

The pharmacy is a valuable resource for the community and, when properly managed, can build sales and profit for the retailer. However, this business sector demands great internal care regarding theft, shrinkage, and compliancy. It is an attractant for criminal activity on many levels that requires special investigative strategies and techniques. It requires detailed knowledge of systems and procedures unlike any other retail sector. The challenges for loss prevention staff are enormous because of the complexity of just the business aspects that need to be understood.

Investigations must be concluded quickly and with precision so that the public’s interests are not harmed. At the same time, however, there must be insight into addiction as a disease to allow the practitioner to be somewhat proactive while in the stores. It is a novel business sector that will continue to demand skills and technology that are outside the scope of traditional loss prevention.

(1) Muha, J. (2006, September 1). Drug diversion—Preventing retail pharmacy theft. Loss Prevention Magazine and LossPreventionMagazine.com.

(2) Terrie Y.C. Pharmacy times lean on me: Help for the impaired pharmacist. http://www.pharmacytimes.com/Article.cfm?Menu=1&ID=4115, 2006, November.

(3) Drug Enforcement Administration. National drug threat assessment, DEA, Pharmaceutical Drugs. http://www.dea.gov/concern/18862/pharm.htm.

(4) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2005, September). Results from the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings.

(5) National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2006, April). Monitoring the future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2005.

(6) National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2005, October). Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2004. Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–45.

(7) Texas State Board of Pharmacy. Controlled drugs. http://www.tsbp.state.tx.us/consumer/broch2.htm.

(8) WH Publication 1462. (2003, June). www.dol.gov/esa/regs/compliance/posters/pdf/eppac.pdf.