V

Vandalism

Vandalism is best defined as the willful and malicious destruction, infliction of damage, or defacement of public or private property. The various acts of vandalism are frequently referred to or known as acts of “malicious mischief.” We know of no empirical data about what institution or enterprise is victimized more often than another, but we suspect retailers probably head the list.

The loss prevention professional is ultimately responsible for the prevention of such acts against company property and merchandise as well as employee and customer property when on company premises. It only stands to reason that if employee vehicles are vandalized, especially if parked in specified areas (it is a common practice in big store environments to designated employee parking areas) and the vandalism continues despite reports made to the police, something must be done to halt the problem. It also only stands to reason, if customers’ cars are broken into or otherwise damaged by vandals, something must be done. Reporting such crimes to the police is necessary but doesn’t necessarily guarantee relief from an ongoing problem.

How do loss prevention professionals discharge that “responsibility” to protect property and merchandise, inside as well as outside the store? They bring to the problem the same expertise and tools used to deal with shoplifting and other forms of theft, i.e., surveillance and detention of persons engaged in criminal acts.

The range and diversity of acts of vandalism in the retail environment almost defy imagination. We’ve prepared lists based on our own professional experience, but surely other experienced loss prevention practitioners and executives could add to our list. We’ve divided the acts into those which have commonly occurred inside the store and then outside the store. The purpose and challenge of the lists is to inform and challenge you to consider your strategy if faced with a series of any of the acts listed.

Inside the Store

• Randomly slashing merchandise with a razor-sharp instrument

• Slashing merchandise methodically, e.g., an entire rack of men’s suits

• Spraying an acid solution on merchandise

• Spraying paint on merchandise

• Placing paper bags containing rats or mice among merchandise, and when knocked over, the pests disperse, terrorizing customers (and employees)

• Placing small uncapped bottles of butyl mercaptan among goods, and when knocked over, the chemical emits a strong odor similar to vomit

• Writing or scratching obscene words and images in public restrooms

• Defacing/scratching mirrors in public restrooms

• Intentionally plugging up sinks and toilets, causing them to flood

• Defacing/scratching interiors of elevators and elevator doors

• Draping toilet paper over sprinkler heads, igniting the paper, and activating the sprinkler

• Writing or scratching obscene words and images in fitting rooms

• Urinating or defecating in fitting rooms or trash containers

• Demonstrators in conga-chain weaving through the store, knocking over displays and trampling or breaking goods

Outside the Store

• Random intentional breaking of glass windows

• Systematic breaking of glass windows with slingshots or air guns

• Throwing or spraying of paint on buildings

• Writing obscenities in paint on buildings

• Applying graffiti to buildings

• Destroying the landscape in flower beds and flower boxes

• Applying paint or graffiti to parking light stanchions

• Shooting out stanchion lamps

Vendor Fraud, Badging, and Control

Vendors (and vendors’ representatives) play an important role in many retail operations. They may stock or restock goods, fulfill some inventory-taking functions, rotate or exchange goods or products, and/or otherwise provide retailers with an extra pair of hands in the daily operations of a store.

Many vendors are seen and accepted as part of the store team and, as such, are accepted without question as they come and go pushing or carrying in merchandise and leaving with “merchandise.”

According to the annual National Retail Security Survey, so-called vendor frauds amount to over a billion dollars in inventory shrinkage in the industry each year. Part of those vendor frauds include vendor reps engaged in the theft of their own line, which the store has purchased and which the rep will resell, or carrying out other unpaid-for merchandise which the rep has opportunistically picked up while engaged in otherwise legitimate access to goods in the store or store’s stockrooms.

One example of vendor fraud which is not uncommon to grocery stores is the vendor who delivers his or her merchandise in bulk cartons, such as dairy products and baked goods, and leaves a void in the center of the stacked goods, thus delivering less than the apparent quantity. Prevention of these thefts requires that, when checking in goods susceptible to this theft technique, all cartons be broken down and a piece count be made of all receivings.

A store doesn’t know who the vendor representative really is, nor is that rep’s background and work history known. And the very nature of the vendor’s in-store tasks precludes serious loss prevention or manager oversight. Clearly, then, some reasonable controls must be in place. The following suggested “controls” may not be applicable to the bread delivery man or similar daily reps who access the store through the receiving area, but where otherwise applicable, they should be in place:

• Vendor reps and any assistants are required to “sign in” in the store’s vendor log, which should be maintained in the store manager’s office.

That log requires the following information:

• Vendors will be issued a vendor’s badge, which must be worn at all times in the store.

• If employees are prohibited from taking their purses into merchandise areas, the same rule should apply to vendor reps. Lockers should be provided for vendors’ briefcases, large handbags, or other personal containers.

• When vendors are through with their in-store tasks, they should present themselves at the manager’s office to sign out and turn in their badge.

• If the store has a designed employee entrance, vendor reps should be required to enter and leave the store through that door unless the logic of their tasks dictate the use of the dock. However, the need to access the store through the dock does not preclude following the specified badging procedure.

• Vendors and/or their representatives must understand that any and all containers are subject to inspection, just like all store employees, upon exiting the store.

Vendor Relations

Communication Is Your Bottom Line

On May 10, 1869, the nation was connected by rail at Promontory Summit, Utah. The Golden Spike marked the completion of rail service from Sacramento, California, to Omaha, Nebraska. These 2000 miles of track laid in the 1800s were, by far, the greatest physical and engineering undertaking in this country’s history. Just picture the logistical nightmare to be in touch with your vendors without even the use of a telephone, which was only patented in 1876.

The one tool available besides the written or printed letter was the telegraph. Samuel Morse’s first message, sent from Washington to Baltimore, was “what hath God wrought.” This was the communication means to order supplies, labor, and capital to pursue this project. “Telegraph,” from the Greek words tele = far and graphein = write, is the transmission of written messages with physical transport of letters. How far has the transportation of letters, numbers, and words come since the telegraph, and how can we best utilize it for communications?

What made this railroad project successful without all the tools we have available in this day and age? The simple answer is clear and concise communications with vendors. Sitting on both sides of desk has given me a fairly concise insight into how important spoken words and the transmission of words are needed to reach your purchasing goals.

A checklist is very important. By using one, your vendor can give you the answers you need for presentations or budgets. Being precise in the direction you want to take your company is key to having a successful program. The motivational speaker Anthony Robbins said “successful people ask better questions and as a result they get better answers.” Vendors have their own list of product priorities they would like to follow, which are directed by their management. Having a clear information path to your desk will help you make the right decision. This is accomplished by having various vendors with similar products visit or spending adequate time at their offices or convention platforms. Having the knowledge to integrate similar products, from different vendors, helps you realize your goals. In this day of changing technologies, it’s important to be updated constantly to make sure you are deciding on the best products available.

There are a number of points which should always be followed when deciding on a product or service.

• Always get at least three company references.

• Determine if the sales rep is avoiding your needs just to put you in another product or service.

• Ask for new concepts and request real R&D information.

• Ensure contracts are clear and concise to determine cost responsibility of installation and removal, if necessary, of products being tested at a facility.

• Work within a critical path for timely goals. They should lead to realistic timelines that tie into penalties if goods and services are not realized.

• Work with your vendors to furnish a way out of contracts that is fair to both parties. The customer should have a termination clause in a contract, since it gives the customer more clout in contract renewals and the vendor understands that contracts are not forever.

• Ensure warranties and maintenance policies are in writing versus verbal assurances.

The bottom line is not always the bottom line. Just as your company runs on making a profit, your vendors are no different. Calling on your peers is important to make sure that you are working and communicating with vendors who are honest with their pricing and the quality of their products or services. When you want to trigger their response, you want be in the position to give the vendors a true picture of the product you will be purchasing. Find out were you have to be, in dollars, to maximize the budget you have or will be requesting. When you work with your staff or persons you know in the industry, channels will open which give you knowledge of how products or services are priced.

Never hold back on asking questions such as “Where is my product being manufactured and shipped?” Simple questions can save you the agonizing feeling of waiting for a product that is sitting in customs, delaying your store openings or renovations.

Sometimes your vendors do not have all the answers. Service questions usually are easier to resolve than products. Services are a true interpersonal resource, and you should look to their efficiencies. Whether you’re dealing with a product or service, the answer you receive should always be an honest answer. Working with your vendors’ logistics, warranties, shipping schedules, pricing, and installation times is based on their honesty in replying back with concise answers. Vendors who will call you with a disruption of a time line, instead of letting it lie dormant, are your partners, and you should thank them in replying to their honesty.

You should always keep an open communication portal, be it email, letters, telephone, or any transmissions from vendors you might not be doing business with at the present time.

Choice is key in addressing the best interests for your company. New relationships should be continually built, even if you are not doing business with a particular vendor.

We all have time constraints, but time should be spent for new vendor presentations, so you always maintain the best knowledge base possible. It really does not matter if you have a single- or multiple-person operation. The flow of information that is now available should be utilized to maximize benefits. When you communicate with knowledge, it will make your vendors react with the vigor that you expect.

Video Surveillance: From CCTV to IP and Beyond

The use of video surveillance has been evolving since the mid-1970s and escalated in the 1980s with the development of Charge Couples Device (CCD) image technology. CCD technology has led to an evolution in the use of video cameras in security surveillance applications such as government, banking and finance, manufacturing and industry, transportation, retail, and education.

The traditional video surveillance infrastructure, commonly known as closed-circuit television (CCTV) systems, has become commonplace over the past two decades and accepted technology for most video security surveillance applications.

CCTV systems in the mid-1970s started with a simple hardwired environment of analog security cameras to image multiplexers that would combine several cameras into one analog image to a video cassette recorder (VCR) for storage and playback (see Figure V-1).

As the acceptance of a hardware video camera system in surveillance became more commonplace, products such as the VCR with a built-in multiplexer were developed (see Figure V-2).

These CCTV systems allowed the capture and storage of video events that provided security personnel with the capability of viewing an event after the occurrence but did not provide for immediate access and assessment of events unless viewed and monitored by security personnel at the time of the occurrence. Once an event occurred, in order to review the event, security personnel would need to take the recorder offline to view the video. This created an instance in which no video surveillance would occur. This period of time would leave the system user vulnerable with no video surveillance.

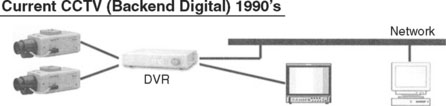

Continued CCTV system evolution, along with the acceptance of IT network infrastructure, saw the creation of the digital video recorder (DVR). It provided the same recorder capabilities of recording the cameras, but also provided a network interface that allowed for the simultaneous recording of events and viewing and monitoring of events by an individual and/or a group of individuals who had access to the back-end surveillance network (see Figure V-3).

These CCTV environments provided for expandability to multiple cameras and allowed for the development of larger enterprise security camera systems with multiple DVRs and multiple analog CCTV cameras tied to a local area network (LAN) and a large-scale monitoring environment that was utilized by security teams with larger facility deployments of security cameras, such as large corporations and government (see Figure V-4).

Although this system architecture was accepted and implemented in many security system environments, there continued to be several drawbacks to the architectures that precluded the end user from utilizing the information being captured.

For one, CCTV systems rely on single-purpose cameras, cabling, recorders, and monitoring, which provides a complex point-to-point infrastructure in which expansion of the system can increase cost for installation, expansion, and maintenance of the system.

Monitoring of the system has been made available with the development of the DVR. The system design is limited to lack of information control, which needs to flow into the DVR and then convert the image into a digital signal that can be monitored over an IP network. The DVR becomes the limiting technology point of the CCTV system as the end user has limited access to the camera control, limited scalability due to the DVR input capabilities, limited remote access, limited system mobility as the system is hardwired back to the DVR, and as the typical DVR uses time-division multiplexing, the record/refresh capabilities are limited to the global refresh capability of the overall system.

The CCTV to IP Surveillance System Evolution

With the IT revolution of 2000, continuous growth and acceptance of network technologies and high-speed IP networks fueled the movement of businesses and institutions to add new applications which benefited the network capabilities of the emerging IP network infrastructure.

The addition of IP video surveillance applications leveraged the same IP network system infrastructure which already was in existence to move data. In addition, the acceptance of compression standards for digital video applications over IT networks helped to increase the use of video as an acceptable IT application.

The first step of IP surveillance into the IP network system was analog CCTV camera technology attached to a network server, which converted the camera image to a compressed image that could be moved around on an IP network without compromising network traffic and without decreasing the available network bandwidth that businesses and institutions used to move data.

This approach provided a link between the traditional CCTV system and the networked IT systems. These network server products provided for the video to be changed into an IP stream and feed out over the network. Further advancements in server technology allowed for the loop-though of the analog video to allow for the continued use of the DVR (see Figure V-5).

Further camera development created IP cameras with built-in web servers and Ethernet connectivity, which can feed an IP network, provided system flexibility is beyond the traditional CCTV system technology.

IP surveillance systems can generate the same high-quality images as analog cameras but provide simplicity when increasing the cameras connected to the network by leveraging the LAN already in place. When the existing LAN is leveraged, the addition of new IP cameras provides for easy scalability without the addition of new hardwire cabling. This provides for easy and faster additions to the IP surveillance system.

By using this distributed network architecture, the system user can configure control of the system to be centralized or distributed to various users, and with a single server, with a software application, can record and run the entire system. The server environment can also store the recorder IP surveillance video and have network-attached storage such as tape backup or reside on a storage area network (SAN) system for increased capabilities. In addition, the use of server technology provides for future upgrades with faster processing power, larger storage disk drives, and new software application.

As the use of IP surveillance systems has grown, increased development of software applications has also grown to accommodate the expanding need for instant access to IP video surveillance to be used in rapid deployment and collaborative communications of events as they are occurring. The user can configure the system to provide permission levels which allow remote access to authorized clients who have received permission for monitoring the IP camera video.

Lastly, IP networking allows for the addition of bidirectional audio, which allows for two-way communication from the camera to the security control station if a microphone and speaker are added. These developments deliver high-quality images over an IP network. Going beyond the IP network is also possible.

Additional advancements to the IP system such as Power over Ethernet (POE) provide for easy, rapid deployment of cameras in various environments (see Figure V-6).

POE use of CAT5E or CAT6 cables delivers data and power to IP cameras via a mid span unit, which injects the power into the CAT5E or CAT6 cable to IP cameras that are enabled to accept such. In addition, cameras that cannot accept the POE directly to the camera can be powered using a splitter adapter. The POE is limited, though, by the CAT5/6 cabling to a distance of 100 meters from the mid span unit. However, the benefit of POE—such as no AC outlet required for each IP camera, reduced installation cost, and flexibility to reposition cameras by moving the CAT5/6 cable—has increased the use of such systems in schools and small business facilities, for example.

Wireless system capabilities have also allowed for the use of IP cameras without the need for cabling installation for video and control, which saves both time and money. From a simple 802.11 wireless transmission from a light pole in a parking lot to the guard station, to mesh networks that provide multiple cameras to link together wirelessly feeding video to hotspots in a given area or a facility network, wireless systems have been used in many different applications.

Video analytics are also becoming a large part of IP surveillance system technologies that end users can obtain great benefits from. Analytics will continue to grow within the security industry over the foreseeable future as new software and hardware products come to serve the expanding IP surveillance market. IP surveillance system video analytics will allow end users to overcome the limitations found in traditional “back-end heavy” CCTV video analytics systems, such as the high cost of the system, and the limitations to post-recording search and processing performance of the analytic system. Whether such video analytics will become accepted in the market will depend on the ease of use and affordability of such technology.

IP camera products are available today and can provide preprocessing to the video image, such as intelligent motion or nonmotion detection, that creates the necessary metadata to feed the back-end video analytic processing systems. This preprocessing of the video image by the IP camera, as an intelligent edge device, can be found in products in the market today. This camera edge device intelligence can help conserve infrastructure bandwidth and save the processing power of the video analytic system back-end processing, which in a traditional CCTV systems requires full-time video streaming in order to obtain the same results. The preprocessing information combined with the post-processing use of the generated metadata can greatly improve the accuracy and performance of the video analytic system. This infrastructure provides the user a distributed and enhanced processing architecture that can greatly benefit him or her.

A wide range of these applications products is coming to market today. These products range from highly specific deep data analysis packages to general-purpose security suites. These products will enable the growth in the IP surveillance market that will allow intelligent video-based analytics to be deployed in a variety of settings by a large number of security operations.

However, the creation of an infrastructure for broad-based, economical deployment of these advanced video analytic capabilities is necessary to support the use of the expanding IP surveillance systems. Security system professionals need to review and determine if their existing security system strategy can support the expanding requirement of such video analytic applications that are becoming available and to begin planning for the migration of existing CCTV system architecture to an IP-based surveillance architecture that can take advantage of these applications.

In conclusion, continued utilization of the traditional CCTV systems will benefit from advancements in camera technologies that will enhance the use of the existing systems. Network server bridge products will allow CCTV system users to migrate and integrate their existing CCTV system to become a part of the expanding IP surveillance system architectures that are being implemented today and into the future. The increase in the quality and functionality of IP-based security systems will quickly establish a new standard for the use of video surveillance systems. In the post 9/11 world, heightened expectations for rapid response to events with increased use and quick access to the event video information that can be made available by an IP surveillance infrastructure will drive the increased use and demand for IP systems across many industries, schools, transportation hubs, and municipalities.

Visitor Badging and Control

Visitors to a retail facility such as a store, corporate headquarters, buying offices, or distribution center should be required to sign a “visitor log” and be issued a “visitor badge.” The issuer need not be a security or loss prevention employee; any receptionist or representative of management may undertake this task. The purpose of the visitor badge program is to maintain a historical record of nonemployees who access the facility in question in terms of

Visitors must be escorted at all times by their host and must not be allowed to wander through merchandise areas or office complexes at will. Vendors may be an exception to this rule. Please refer to “Vendor Fraud, Badging, and Control.”

The badge itself may be fabricated in a hard material, prenumbered format, to be returned and retained for subsequent reuse. Such numbering serves as an inventory control. Visitor badges may also be of a temporary paper or fabric material, on which is printed (in ink) the name of the visitor and the date and time the badge was issued; these badges are intended for one-time use and are to be disposed of at the end of the visit. There is also a temporary badge which “self-destructs” by turning black after a predetermined period of time.

Any person observed in nonpublic areas of the facility, such as store stockrooms, who isn’t known or identified as an employee should be challenged regarding presence. If it’s determined the individual is a bona fide visitor but somehow bypassed the signing-in process, such visitor must be escorted to the reception desk, manager’s office, or other appropriate area (depending on the nature of the facility) and issued a badge. An effort should also be made to determine what enabled the visitor to bypass the visitor control procedures, and the deficiency corrected.

VSOs vs. Plainclothes

Which strategy is most effective: deploying a visible security officer in some form of uniform or utilize agents in plainclothes? Clearly, the logic behind the visible agent is the hoped-for benefit of deterring shoplifting because of the presence of a representative of management dedicated to security of the store and its contents. The visible officer is a reminder of security just like the sudden appearance of a black-and-white state patrol car causes motorists to check their speed and thereafter be mindful of their speed, at least for a while.

The logic behind the plainclothes agent is to surreptitiously blend the protection staff in with the customers in hopes they won’t be identified as representatives of management and enable them to observe and subsequently detain those customers who choose to steal merchandise.

The use of the former is unquestionably a loss prevention technique. The latter is more of a security technique, albeit there are advocates whose stance is that detection and apprehension are just two of many forms of “loss prevention.”

To put the issue in the proper prospective, we need to go back and look at the historical background of protection strategies in retailing.

Up through the 1960s, major retailers staffed “Protection Departments” (which evolved into “Security Departments”) with “floor walkers,” “store detectives,” “operatives,” and “agents.” The emphasis of such departments was solely the detection and apprehension of shoplifters and dishonest employees, and this was achieved through a covert strategy (plain-clothes). Plainclothes staffs were augmented from time to time, principally during major sales or holiday periods, with off-duty police officers in uniform or uniform contract guards, but such use was more for crowd control and assistance in arrest cases.

The measure of success and the justification for security budgets was directly related to “production,” i.e., the number of shoplifters apprehended, the number of dishonest employees caught and terminated, the number of credit card forgers jailed, and, in some cases, the level of inventory shortage. And store security departments at multistore companies unofficially competed for the most arrests each year.

The year that proved to be pivotal for one retailer was 1969. The company, a leading fashion department store chain headquartered in Los Angeles, California, had a remarkably successful production record of shoplifter and employee detections; however, amazingly, the company experienced the worst inventory shrinkage performance in its history—3.2% of sales! We use the word “amazingly” because there was then a belief, which still exists today, that there’s a relationship between theft and shrinkage; i.e., the less theft, the less shrinkage. And there was also the belief, which still exists today, that the more thieves a store identifies and removes, there will be less theft and hence less shrinkage.

However, the reality was just the opposite. Management didn’t care how many crooks its security department caught, but it did care about the loss of profits reflected in the high inventory shortage. So, for the first time, the presumptive value of the security department’s contribution to the benefit of the enterprise (the department store company) was challenged. Security management had to come up with a better plan. What to do?

In casting about for some answers, some insight into a new strategy, one thought occurred over and over. We knew, and everyone in the security business knew, that one problem on the floor which impeded catching shoplifters was some innocent customer or sales associate coming on the scene and inadvertently “burning” what surely was going to be an arrest. The eye contact was all that was necessary to spoil a shoplifting act in progress.

In the 1970s, this was labeled the “Oh Shit Syndrome”, i.e., the emotional and personal reaction on the part of a person engaged in an evil deed who rightly or wrongly believes he or she has been detected in that act by virtue of seeing someone looking at him or her. It wasn’t a “scientifically” proven phenomenon, but rather, the recognition of reality.

Senior management of the Broadway was concerned about the language but acquiesced to the production of an internal video production explaining the syndrome for use in training.

We also knew many man-hours were consumed when a detention was made by the processing and waiting for the police to respond to the store and dispose of the detainee, be it by citation or transportation to the station. And all the while the store detective was in this processing mode, many acts of shoplifting could be ongoing, uninterrupted. With this knowledge, we determined that for the time required to process one detection (and the processing), we could intentionally burn approximately 30 would-be acts of theft (depending on the size, volume, and location of a given store), giving us a ratio of up to 1:30.

This was the genesis of a whole new strategy, which we titled “Loss Prevention”; i.e., what can we do to prevent the acts of theft, rather than try to catch them all, because it was apparent that we couldn’t stop or even slow down the thefts through a detection program. Indeed, we knew that when we “blitzed” a store (assigned an entire team of store detectives to saturate one store), we could increase the number of arrests, and we never reached a saturation level. Put another way, the more store detectives we assigned to a store, the more arrests were made. So if 5 store detectives in a one million square foot store could generate 12 shoplifting arrests in 1 day, could 1 or 2 “loss prevention” agents potentially deter over 300 would-be thefts? And this was right after a nationally published survey which suggested that 1 in every 10 customers shoplifted. With literally thousands of customers coming into the store, was 300 an unrealistic possibility?

This strategy led to the first and often-copied “Red Coat” program, wherein about 80% of the store detective staff was retrained to prevent shoplifting by being highly visible (wearing a tailored red sport coat with a gold cloth pocket badge reading “Security”) and constantly moving about the store with a pleasant expression on their face, making eye contact with as many customers as possible. The retraining included how to deal with or respond to “Are you watching me?” “Are you following me?” to “Here, I didn’t want this anyhow “(as the customer pulled an item out of her purse and handed it to the loss prevention agent). “Loss prevention,” which meant “burning” the would-be thief, worked in most cases. The balance of the staff (20%) continued in plainclothes and continued in their detection and apprehension mode. Those who couldn’t or wouldn’t be deterred, and felt confident they could succeed in a theft because they knew where the Red Coats were, wound up being arrested. It was a balancing act that worked.

At the end of the first full year, this radical program and departure from the universal retail security practice across the industry and across the country resulted in less than half the detentions of the infamous 1969 figures, but the inventory shrinkage dropped from 3.2% to 1.7% of sales, representing many millions of dollars. Year after year for the next 10 years, with the Red Coat program in use, orchestrated with a variety of other “shortage awareness” activities and programs, the shrinkage continued to decline.

The program was introduced in annual national meetings, and many in the industry replaced the title “Security Departments” for the then-modern and apparently successful “Loss Prevention Department” program. The name given the function is really immaterial; it’s how the department operates which is important.

With the passage of time and personnel, the philosophy of deterrence over detection lost momentum and the majority of programs in existence today are “loss prevention” in name only.

Back to the original question: Which strategy is most effective: deploying a visible security officer in some form of uniform or placing agents in plainclothes? The first answer is: In these times, a balance of the two could be effective. The second answer is: It depends on whom you ask.