CHAPTER 43

Building Organizational Project Management Capability

Learning from Engineering and Construction

The construction industry is widely accepted to have the most mature project management processes. Information technology (IT) project managers envy the accuracy with which their construction colleagues can estimate and predict progress on a building. They borrow their tools and techniques but struggle to emulate their results. They fall back on the conviction that “it’s different in IT.” Thus, they resign themselves to continuing levels of underperformance.

This is a strange response when even IT project managers would agree that there is a core of project management knowledge that is common to all projects. Who would doubt the wisdom of scope control in any project circumstance? Failure to leverage the learning of one industry into another is therefore normally explained by appeal to the need for domain knowledge. For example, the rate of change of technology, the volatility of requirements, and the invisibility of software are all supposed to make IT project management radically different. Fortunately, we do not need to resolve the debate about the importance of domain knowledge in order to improve learning.

The central point of this chapter is that industries can improve their own capabilities by adopting a model of project management capability development from the construction and engineering sector. Domain specifics may apply to projects, but they do not apply to the structures and processes by which project management itself is managed within an organization; mentoring can be effective in both construction and IT even though the learning may be different in certain respects. The domain independence of the model can be seen from its application to high-tech product development.1 Research has shown that the construction industry has improved its performance over the last twenty years.2 Despite embarrassing blips from time to time, it has managed down its performance variance. Many high-profile mega-projects are today successfully delivered against demanding specifications and stretch targets. These range from Hong Kong’s International Airport, which met its multibillion-dollar budget, to the Sydney and London Olympic facilities that were in service twelve months before the start of their respective games, to the first half of the $8 billion Channel Tunnel Rail Link project installing a high-speed rail infrastructure and service from the Channel Tunnel to London. During the 1980s and 1990s and into this century, new ways of managing projects at the enterprise level have been adopted. This has had the effect of creating enhanced capability through support for performance and learning.3 Transfer of consruction’s new ways to other industries will allow them to learn from their own experience so that any uniqueness of domain will be irrelevant. The benchmark for improvement will not be comparability with projects in other industries but improvement against your own organization’s past performance and that of your industry peers.

A model of the organizational and management system by which construction and engineering companies manage project management is presented in this chapter. The model includes such practices as recruitment and development of talent, employment policies, role design, reporting processes, performance management, and organizational learning.

Engineering and construction are project-centric industries—that is, businesses that earn their revenues through projects. Transferability of the practices common to construction and engineering is an important issue covered below. There are two targets for transfer—companies in other project-centric industries, such as management consultancies and systems integrators, and companies in industries where projects are only a part of their total activity, such as new product development by an automotive manufacturer or policy development by an industry regulator.

Finally, we assess developments that indicate progress toward adoption of the capability development model, and examine new challenges for project-centric and non–project-centric organizations as the performance demands on project managers grow.

BUILDING PROJECT MANAGEMENT CAPABILITY: THE CONSTRUCTION AND ENGINEERING EXAMPLE

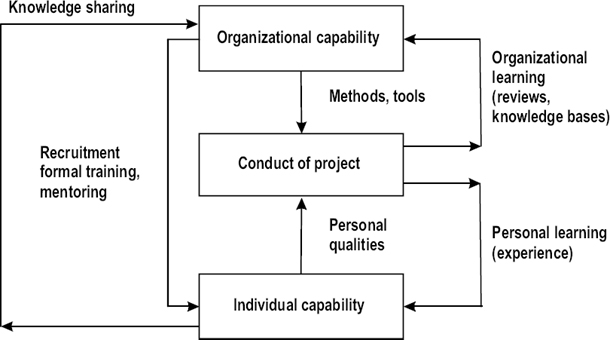

Project management capability operates at three levels:

1. Project level

2. Individual level

3. Organizational level

The project is both the start point and the end point. It is the focus for the application of individual and organizational capability. It is the source of experience on which learning is based.

The individual project manager is the linchpin, the essential ingredient. No project of any size or complexity can hope to be successful without an appropriately competent project manager. Equally, without project managers contributing their ideas and experience to the common pool of knowledge, organizations cannot expect to improve from project to project.

Organizational capability contributes to improving project performance by providing supports for the manager working on a project. It also assists the individual to learn, and grows the organization’s communal knowledge of projects.

FIGURE 43-1. MODEL OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT CAPABILITY DEVELOPMENT

Figure 43-1 summarizes our model of project management capability development with examples of how the three levels interact.

Organizational capability consists of a number of elements. These were identified in an earlier research study in which we intensively interviewed project managers and directors of a number of top-level Australian construction companies.1 None of the companies fully employed all the elements described, but together they amount to a coherent set of practices that support both performance improvement and the development of lasting project management capability. These capability elements have been subject to continued verification subsequently and include the following:

• Organizational structure

• Role design

• Knowledgeable superiors

• Values

• Human resource management

• Methods and procedures

• Individuals’ personal characteristics

• Conduct of the project

We see these elements of capability working in a number of ways:

• Making the job easier

• Facilitating the application of knowledge

• Ensuring a supply of capable project managers

• Developing individual knowledge

• Developing organizational knowledge

• Motivating learning

Organizational Structure

Business units in construction and engineering companies typically have flat structures that serve two main purposes. They place project managers and their projects close to the locus of power and decision making in their organization, which gives them high visibility and access to resources and decisions as needed. They de-emphasize other functions, such as finance, design, and estimation, so that by contrast with non–project-centric organizations, these are clearly support functions, not internal competitors for resources and attention. By placing projects at the center of the structure, these companies eliminate a lot of possible organizational noise, and thereby make the job of project management easier.

Role Design

The crucial element of role design involves balancing responsibility with accountability, resourcing, and authority. This equation is crucial to making the job easier and facilitating the application of knowledge. Plainly, having resources and authority are necessary to making a project doable. Without them it is hard to hold the project manager to account. To penalize a project manager who has not been given the wherewithal to succeed sends a message to others that the organization does not understand the challenge of project management and that it is not an organization in which projects represent a realistic career. Learning is likely to be retained by the individual rather than shared.

Knowledgeable Superiors

Project managers’ superiors in construction have three important characteristics. First, because of the flat structure, they are likely to be people with authority and access to resources that can help solve unexpected problems. They can thus make the project easier. Second, they are typically highly knowledgeable, having graduated from many years in the project manager role themselves. This means that they understand progress reporting and have a nose for potential problems. They are thus able to prevent problems from getting out of hand and are equipped to guide their project managers through difficulties, thus enabling knowledge to be successfully applied. Third, project managers’ superiors usually are involved in the client relationship from the start. They will have sold the project to the client and will have helped shape its initial stages. Because they accept responsibility for the project and will themselves be held accountable by the executives, they are highly motivated to share their knowledge with the project manager and do everything they can to help make the project successful.

Values

Three values underpin project capability in construction companies—a focus on performance, relationships, and knowledge. The focus on performance is evident in the reputational advantages that accrue with success—“X built the tallest high rise in Western Europe,” or “Y installed the first horizontally suspended bridge.” Conversely, it is also apparent in the careful weeding out of nonperforming project managers. Thus, performance management has become more sophisticated over recent years in recognizing the value of mistakes. While repetition of the same mistake will not be tolerated, the recognition that errors represent an opportunity for learning and that admission of mistakes will not necessarily be punished encourages individual and organizational learning through openness and sharing of lessons.

The focus on relationships relates to customers, partners, and subcontractors. Greater awareness that customers usually represent opportunities for future business and that retaining an existing customer is easier than winning a new one has led to contractors trying to establish contracts and relationships that encourage win–win situations. In some cases this has been extended to their supply chain. The result is that project managers see value in investing in understanding the customer, and partners and subcontractors see value in sharing their ideas and knowledge. So not only is useful knowledge shared, but the job is made easier for the project manager because of a less adversarial environment. And, as several companies have noted, because of less litigation, there is a further benefit in being able to close out projects sooner.

Focus on knowledge is apparent in the explicit recognition of project managers as an asset. In the recession of the early 1990s, a number of the companies with deep pockets kept their better managers on the payroll despite a lack of revenue-earning projects. Symbolically, this sent a strong message that the retained managers were valued, leading them to see it as worth their while to develop new and better ways of working. At the same time, these project managers had more opportunity than they had ever previously had to reflect and share their ideas. Once initiated, the practice of continual improvement has remained. So both individual and organizational learning have been encouraged.

Human Resource Management

Construction and engineering companies do not always have substantial human resources (HR) departments, but they typically do have significant HR practices designed to create and sustain a talent pool of project managers. These practices include recruitment, development, and career-appropriate talent, often at a graduate level. Development involves a managed progress through different project roles to a junior project management position. From there, subject to performance management, the project manager moves into progressively more difficult challenges. Mentoring is built into the reporting relationship because the manager’s superior has a shared accountability that encourages knowledge and experience sharing. So individual capability development is strongly supported by HR practices. The availability of a career path that sees project managers in their fifties and sixties valued and rewarded for performance also encourages individuals to take the long view and to invest in building and sharing knowledge.

Few, if any, companies offer the kind of highly incentivized financial package so common among bankers and software salespeople. Project managers are paid a decent salary and may receive a bonus, although it is usually paid annually and not on the basis of performance on any single project. In fact, by selecting “project people,” companies typically populate their project manager roles with individuals whose biggest motivation is to take on ever-greater challenges. Thus continual learning by the individual is built in.

Methods and Procedures

Companies typically have their own set of methods and procedures for project management. These are internalized and used with discretion rather than slavishly followed. Their principal role is to provide structure and commonality of practice so that reporting can be reliably monitored. They also provide a shared language with which to talk about projects that facilitates sharing of experience and the development of new methods.

Individuals’ Characteristics

Many of the elements of organizational project management capability we have described encourage the acquisition and development of individuals with the right skills and competencies. These include the classic competencies in planning, monitoring, controlling, forming and leading teams, communicating, managing stakeholders, negotiating problem solving, and leading. These are necessary to the effective conduct of projects. But they are not sufficient. Three personal characteristics stand out as driving personal performance—a thirst for experience, personal commitment to delivering projects, and the desire to enhance one’s reputation through association with a successful outcome. One project manager encapsulated the project manager mindset:

In the construction industry, you’ll find that for a lot of project managers it’s a heart-and-soul type thing. It’s a lifestyle. You live, sleep, and eat project. You’re here six days a week. Sometimes you’re working the night shift. Sometimes you’re in here seven days a week. So it’s a lifestyle and it’s a total commitment.

All three personal characteristics are powerful motivators of individual learning.

Conduct of the Project

In describing organizational and individual capability above, we have shown how both provide essential inputs to the conduct of projects through the individual competencies of the project manager applied to the project, and through oversight, support, and intervention by knowledgeable superiors. However, projects are also the source of much learning and some companies act to capture that through encouraging informal interaction among project managers on a regular basis. Others conduct reviews and maintain more formal databases of experience that can be uniformly shared across the business and that can be used to inform future projects even when the original project manager has moved on.

The following case study shows how one leading international construction company exemplifies the model.

CASE STUDY: MULTIPLEX—THE WELL-BUILT AUSTRALIAN

Multiplex is a diversified property business, employing over 1,500 people across four divisions: construction, property development, facilities management, and investment management. Based in Australia, it has a presence in Southeast Asia and Europe. Its core construction business involves managing the design and construction of urban developments, such as office buildings, shopping centers, apartment buildings, hotels, hospitals, and sporting complexes. Landmark projects have included the $430 million Sydney Olympic Stadium and the United Kingdom’s iconic sporting venue Wembley National Stadium.

Multiplex is highly regarded for its ability to compete on cost, but it does so without damage to client satisfaction and as a result seeks to secure repeat business. It operates a flat structure. The board of directors is usually fully aware of what is happening at the construction project “coalface.” Head office functional managers support projects in specialist disciplines including design, contract administration, estimation, employee relations, finance, and legal affairs.

Multiplex’s project managers are highly experienced in construction and project management. The company sets high performance standards, requiring its managers to deliver the building or facility to the client and continue responsibility for any subsequent modification once in service. The company gives project managers control over resources and, within broad limits, the authority to make whatever decisions are necessary to complete the project; they “can make a large number of decisions related to the project with complete autonomy.”

Because performance matters, so too accountability is important. But accountability is exercised in a rounded manner. Reasonable mistakes are understood and recognized as a learning opportunity. While management does focus on project outcomes, overall performance is assessed relative to the challenge. Thus retrieving a potentially damaging situation may be valued more than the final outcome against targets. Small financial bonuses are paid against annual performance rather than specific projects. But the company recognizes that for most of its managers association with a success and the challenge of something new are the key motivators.

Control against project schedule, cost, and quality is tight. The board receives reports monthly. Formal reporting to the project director is done weekly and informal reporting daily. Senior managers actively follow progress also through site visits.

The project directors and construction managers to whom project managers report are highly knowledgeable about project management. Their involvement in business development ensures that their projects can be successfully achieved with commercial returns. The company’s recognition of the challenges of projects means that project managers feel comfortable sharing difficulties with their superiors. As a result, problems are rapidly dealt with before they accumulate long-term consequences.

Recruitment and development of aspiring project managers is based on an apprenticeship model to build long-term commitment to the company and to demonstrate its own commitment to project managers. Consequently, retention is high and turnover is low. Development includes on-the-job-training, mentoring, and formal management development courses. The company’s commitment to its project managers and hence its ability to build organizational capability is reinforced by its preference for internal promotion.

Discussion

Each of the capability elements described in the Multiplex case study makes sense on its own. However, much of the power of this model to make a difference derives from the interlocking reinforcement among its elements. For example, greater tolerance of mistakes encourages openness that permits knowledgeable superiors to assist at an early stage so performance is sustained while learning is enabled. At the same time, this tolerance reflects a fairer form of performance management that in turn supports retention of individuals and retention of their knowledge.

Another way of putting this is to say that by managing the talent pool and making the job easier, the right people are given time in which to learn. By motivating learning, they are encouraged to develop individual and organizational knowledge. Through the application of knowledge, that learning is internalized. Through organizational processes, the learning is externalized and so made available throughout the company.

TRANSFER AND ADOPTION

Our model for developing project management capability has been synthesized from practice in the engineering and construction sector. For those in other sectors, the questions remain: How transferable is the model? How readily can it be adopted?

There are no in-principle barriers to transferring substantial elements of the model to other industries because it focuses on learning and support for performance within an individual company. So while a biotech company developing new drugs and an IT systems integrator implementing enterprise software systems may face radically different challenges in terms of the technologies they employ, the regulatory regime they confront, the demands of trials and testing, and so forth, each can develop its own learning, including whatever knowledge is sector- or company-specific. As we shall see in the next section, a number of IT companies have started to transfer the model to their own situation.

The one area of the model that can be problematic is transfer of those elements that are more dependent on the project-centric nature of the organization. For non–project-centric organizations, such as retail banks, supermarkets, and logistics companies, it will not be thought desirable to emulate structural characteristics that we have seen create visibility, enable executive attention, and deliver necessary resources, at the expense of the focus on day-to-day operations.

Our model was derived from the practices of large companies. This raises the concern that size may be a barrier to transfer. Obviously, large companies are to some extent better positioned—for example, for a company undertaking one hundred projects per year, the return to scale of investing in project management capability development is greater than for a company undertaking just ten each year. But the investment need not be a fixed cost regardless of size. As we noted earlier, none of the engineering and construction companies we studied exhibited all the characteristics described in the model. Learning can be seeded and performance improved even in small companies by such simple and cheap devices as organizing Friday evening drinks for project managers once a month. Celebrating their successes can be as potent a reward as financial bonuses. So, while larger companies may have the resources to dedicate to developing formal supports for project management capability, smaller companies can still gain benefit from the model.

How then should companies set about adopting the model or elements of it? Identifying an organizational lead and focal point is the first priority. For a larger company this may involve the creation of a corporate project/program office. For a smaller company, it may be the nomination of an individual, either a senior project manager or an executive responsible for project managers. In either case, an individual should be tasked with developing organizational project management capability and evaluated accordingly. The task itself should include providing processes to support existing projects, a common set of tools and knowledge bases, structures and processes to permit learning, motivation and support for the capture and sharing of learning, and support for the development of a set of performance management and HR practices to grow the talent pool of project managers.

Even with organizational commitment and resources behind the organizational lead, it takes years to design, introduce, and embed all the relevant practices. This is not a quick fix. That said, once achieved, it need not be a continuing direct cost. Some organizations we researched, such as Multiplex, had no corporate project office but had embedded the relevant practices in their everyday organizational processes.

EMERGING DEVELOPMENTS

The project environment is dynamic and it is worth reviewing a number of new developments that are now with us or just around the corner. These are extending the scope and challenge of traditional project management, extending the need for capability development to more complex organizational forms, and extending the focus of development beyond the project manager.

Though the IT sector’s reputation for project performance and its track record in developing project management capability are equally poor,4 diffusion of the capability development model is occurring. A United Kingdom government department recently asked one of its international IT suppliers what it was doing to improve its project performance. The company’s inability to answer the question galvanized it into action.

In the last few years, we have seen more large IT companies, as well as hardware, software, and systems integrators, adopting some form of capability development initiative. For example, the UK arm of one major European IT company identified a project management champion as the lead for capability development. She has instituted a project management career structure, assessed its project manager pool, undertaken appraisal and mentoring, defined development paths for individuals, implemented a recruitment and selection process, and instituted a code of practice for the conduct of projects as well as for training staff in a standard methodology. And confirming that the champion role need not be an ongoing cost, she explained, “It’s my aim to work myself out of a job.” This kind of example suggests that much of the model is transferable.

But even while the model is diffused more widely, the environment is changing and placing new and greater demands on many project managers. Customers are increasingly demanding not merely a delivered project but the tangible benefits for which the project investment was made. In construction, BOOT (build–own–operate–transfer) contracts require the successful operation of a building or infrastructure, which implies responsibility for operational services, such as heating and elevators, and for continuing maintenance. In defense, governments require not merely the delivery of aircraft but the ability to destroy enemy targets, which implies responsibility for maintenance, spare parts logistics, and munitions. In IT, customers demand not just delivery of a system but also the achievement of cost or revenue benefits, which implies responsibility for business process change. Many companies see that, as a result, they must involve the project manager more closely in the development and selling of the business so as to ensure that the end result is deliverable. Thus, project managers are being called upon to extend their skills both at the front end and back end of projects.

Two implications are worth noting. First, as the scope of the role extends, so our model needs to reflect the new competences required. This in turn may require adjustments to performance management systems, to career structures, to tool sets, and so forth. Second, members of the current pool of project managers may no longer be suitable for the new role. Therefore, there may need to be an exit strategy for them or a reconceptualization of the role so that their skills can be exploited within the framework of the extended project.

A further dimension of added complexity for capability development is the consequence of joint venturing. Joint ventures are usually established for a quite limited duration among companies that in other circumstances may be thought of as competitors. Thus, not only may there be no long-term payoff from learning, but also sharing of knowledge may be seen as counterproductive. However, win–win contracting can counter these tendencies. In the United Kingdom, the Channel Tunnel Rail Link project has been widely seen as exemplary. A complex joint venture to deliver the railway in two sections, it created a common culture such that there were no external signs of which member company any individual works for. Identification with this enormous project was strong. Although lasting more than ten years in duration, it was necessary to have as much knowledge as possible available at the start. Learning was brought in through a policy of recruiting people with experience on two major rail projects of recent years—the Channel Tunnel itself and London Underground’s Jubilee Line. Within the project, a thriving lessons-learned program generated a mass of knowledge. When the project for the second section was launched, kick-off days were organized to ensure no learning from the first section was lost. Thus where a joint venture has a long-enough life and where there are commercial advantages, capability development may still be a worthwhile investment.

Finally, two future developments are worth watching for. First, project contractors are increasingly focusing on their clients as a point of leverage for improvement. They argue that the client gets the projects it deserves. Poor contracting by clients engenders counterproductive behaviors from contractors. A better-educated client will make for better projects. The plausibility of this argument was borne out recently by an IT project manager who invested in teaching her client how to estimate a project. Subsequently, she found renegotiation of the contract much easier because she could hold a more informed conversation with the client. So it is likely that we will start to see capability development efforts extending beyond the boundaries of the contracting organization.

Second, non–project-centric businesses are becoming more dependent on projects. Recently, an insurance company conducted a work audit and discovered that its managers spent more than 50 percent of their time on projects.5 With large-scale operational businesses of this kind finding themselves continually pressed to change and improve, they are obliged to undertake more and more projects. Over time, it is possible that the financial markets will increasingly value these companies according to their project portfolio and their capability to execute successfully. Organizing in a more project-centric way may then become common among supermarkets, banks, and insurance companies, as well as those in construction, engineering, and IT. In the meantime, there is no reason why non–project-centric businesses that nevertheless conduct projects as a continuing aspect of business improvement should not adopt and adapt elements of our model. While internal organizational structures may impede role design that balances authority and resourcing with responsibility, thereby limiting accountability, HR processes that focus on recruitment and development, mentoring, and the creation of knowledge bases can all be implemented. What is typically lacking is the organizational will to invest in project management because it is seen as noncore, but as we have just suggested, even this attitude may be about to change.

The model of project management capability development presented here, therefore, represents a solid foundation on which any organization in any industry can base its own initiative. The emerging developments we have described amplify the need for organizations to pay explicit attention to project management capability.

![]() Thinking about companies that you know, how well do they manage the continuing development of their project management capabilities? What more could they do?

Thinking about companies that you know, how well do they manage the continuing development of their project management capabilities? What more could they do?

![]() What issues would you envisage in the acquisition and maintenance of adequate project management capability in a multiyear, multi-project joint venture? How might you tackle these issues?

What issues would you envisage in the acquisition and maintenance of adequate project management capability in a multiyear, multi-project joint venture? How might you tackle these issues?

![]() In what ways do extensions of the project manager’s role into activities such as business case development and postimplementation benefit delivery and require capability development? What management initiatives would you take to ensure that they are adequately included in a company’s capability development practices?

In what ways do extensions of the project manager’s role into activities such as business case development and postimplementation benefit delivery and require capability development? What management initiatives would you take to ensure that they are adequately included in a company’s capability development practices?

REFERENCES

1 Christopher Sauer, L. Liu, and K. Johnston, “Where project managers are kings,” PM Network 32, No. 4 (2001), pp. 39–49.

2 Robert J. Grahamand and R.L. Englund, Creating an Environment for Successful Projects: The Quest to Manage Project Management (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1997).

3 A. Vlasic and P. Yetton, “Delivering Successful Projects: The Evolution of Practice at Lend Lease (Australia),” 16th International Project Management Association World Congress, Berlin, 2002, pp. 4–6; D.H.T. Walker and A. C. Sidwell, “Improved construction time performance in Australia.” Australian Institute of Quantity Surveyors Refereed Journal (AIQS, Canberra) 2, No. 1 (1998), pp. 23–33.

4 Sauer et al, 1999.

5 Christopher Sauer and C. Cuthbertson, “The State of Project Management in the UK,” http://www.computerweeklyms.com/pmsurveyresults/surveyresults, 2003.