Chapter 2

Walking through the Decision-Making Process

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Identifying why a decision needs to be made

Identifying why a decision needs to be made

![]() Amassing and analyzing data

Amassing and analyzing data

![]() Generating viable options and making the final decision

Generating viable options and making the final decision

![]() Communicating and implementing the decision

Communicating and implementing the decision

![]() Understanding intuitive decision-making

Understanding intuitive decision-making

As a decision-maker, you face all kinds of situations in your business, and each situation calls for a different decision-making approach. Some approaches are rational and analytical; some are more intuitive. Despite their differences, both rational thought and intuitive thought gather and make sense of information in an attempt to arrive at the best course of action.

Whatever approach you use, you can benefit from understanding the basic steps to making sound decisions. In fact, for every decision you make, you’ll touch on — accidentally or intentionally — the steps we outline in this chapter. We also show how your intuition enables you to make rapid-fire decisions in quickly changing, high-risk situations.

Clarifying the Purpose of the Decision

Being clear on why you’re taking action guides implementation. Establishing purpose (the why) is a must-do, front-end task because you reduce the risk of mistakes and misunderstandings when circumstances change. Purpose provides the focus for thinking, action, and all the micro-decisions that lead to the result.

Identifying the reason for the decision

Decisions are made for several reasons. In business, the two most common reasons for making a decision and taking action are to address a problem or to seize an opportunity:

- Addressing a problem: Operationally, when equipment isn’t working, products aren’t delivered on time, or customers don’t receive what they ordered when you promised it, it’s a problem. When problems occur, you need to take action to find out why the problem exists. In a flower shop, for example, having the fridge that supposed to store today’s shipment break down and not having a backup is a problem. The question is, is this simply a mechanical glitch or is the situation far more serious?

- Seizing an opportunity: Opportunities take many forms: a serendipitous encounter with someone who has the potential to become your biggest buyer, for example, or a change in zoning laws in an area where you want to expand. Other opportunities come dressed as problems: Employee disengagement, for example, is an opportunity to create a better workplace. Recognizing opportunities means seeing situations like these not as problems to be solved, but as a chance to do things differently.

When the reason for making the decision is clarified, being super clear about what you’re hoping to achieve (the outcome or result) provides the focus for getting there. Make sure you can articulate the following:

- Why you’re taking action now and not later

- What will be in place when the action plan is complete

- What conditions you want the solution to meet

Taking a tactical or strategic approach

Actions can be propelled by urgency (you need to do something fast) or inspired by vision and opportunity in the longer term. Articulating what you want the decision to achieve gives you a good idea about whether you need to take a tactical or strategic approach.

To understand the difference between strategic and tactical actions, consider this situation: The workload at your company has become intolerable, and your employees are stressed and requesting overtime pay. In addressing the problem, you can take a tactical approach or a strategic approach:

- Tactical: You look at options that solve the immediate problem, such as outsourcing some of the work or hiring someone to alleviate the burden on your employees.

- Strategic: You step back to observe how work is being delegated and communicated, how existing resources are being used, and so on, so that you can discover and address what is creating the pressure in the first place. With this knowledge, you can institute changes that in the long run will reduce employees’ stress and workload.

Eliciting All Relevant Info

Many decisions that fail do so because they were made using narrow thinking. You don’t know what you don’t know. Narrow thinking can torpedo your business decisions. Consider the business owner who, when her decisions were questioned, always answered, “I know what I’m doing.” She carried on … right into bankruptcy. To avoid the dangers of limited thinking, try to gather relevant information from as many different perspectives as possible, especially the ones you disagree with.

In this section, we outline sources of information and tell you how to vet the info you find.

Doing your research

Depending on the issue you’re confronting or the reason you’re taking action, you may have to conduct extensive research, consult with colleagues who have already successfully faced a similar question, and consult with employees and customers. When doing so, your intention must be to learn rather than to confirm that your own ideas are right. A genuine inquiry builds trust and uncovers key factors critical to decision-making.

The primary goal at this stage of the decision-making process is to look at the situation from as many different angles as you possibly can. Sometimes this task can be difficult, especially when you don’t agree with the ideas you hear, but it is well worth doing nonetheless. Doing a thorough job of gathering information gives you a wide variety of viewpoints to consider, uncovers potential pitfalls, and reveals unstated needs that must be addressed if your decision is to be effective.

Following are some ways you can gain the varied insight and information you seek:

- Monitor and participate in LinkedIn discussions relevant to your business.

- Subscribe to online newsfeeds such as the Huffington Post or other international, national, and regional news outlets.

- Participate in professional associations where you find your clients and customers.

- Ask employees, customers, and clients for input and information by using focus groups or surveys.

- Host information sessions to find out how constituent groups see the situation.

- Consult with colleagues to find out their views on the project or initiative.

- Give employees an opportunity to ask questions of people in leadership and management positions in an open and honest fashion.

Gaining distance to stay objective

You can see a situation more clearly when you haven’t got your nose in it. For that reason, when you gather information, you want to maintain some distance. Doing so helps you objectively assess the information you receive. You’ll be better able to see which questions you need to ask and to recognize who needs to be involved.

Gaining distance is easier said than done, for two reasons:

- You have to remember to pull back and reflect. If you don’t build time to reflect into your decision-making process, it won’t happen.

- You have a blind side — unknown biases or, worse, prejudices — that work against your decision-making. Chances are you’re unaware of these biases in yourself but can spot them easily in others. To avoid being blindsided by what you can’t see in yourself, ask someone you trust to point out when you’re overlooking the obvious.

- Remain curious. Approaching each situation with an inquisitive mind expands perception.

- Notice when you’re being defensive or feel compelled to prove that you’re right. Take these emotional reactions as signals that you’re thinking rigidly or feel threatened. They’re good indicators that you’re overlooking important information that can change how you lead.

Paying attention to different perspectives

Gathering accurate information in a highly interconnected communication environment is challenging, especially because each person can see only a part of the overall picture. What people see depends on their unique perspectives, and what they understand is determined by what they know about their part of the picture. For this reason, you need to pay attention to as many different perspectives as possible. When gathering intelligence, try to do the following:

- Use as many different sources as you can. Take into account personal experience, factual data, and the social and emotional factors that will affect both the decision-making environment and the implementation situation.

- Pay attention to conflicting information. Conflicting info points to holes in the picture and is a signal that you need to keep seeking information from different people. Try asking the kinds of questions a person completely unfamiliar with the topic would ask. This strategy can shine a light on how the different views converge to form the big picture.

- Incorporate diverse perspectives, especially ones you may not agree with, into your thinking. Such perspectives highlight the things you need to consider when making the decision. They also provide insight into the factors that should be addressed when putting together the action and implementation plans.

Separating fact from speculation

Facts — such as the amount of money allocated for a project and the amount spent, the number of employees who work for the company, and the employee turnover rate — can be verified and proven. At some point, however, facts can get mixed up with opinions (based on perceptions) and ideas. The key is being able to discern between them, and the challenge is being able to do so in the midst of change.

When people are in the midst of change and the future is unknown or uncertain, they start guessing about what will happen to feel more certain about what lies ahead. Before long, speculation is running amok because people don’t know what to expect or lose confidence in where and how they fit into the changing world.

You can address speculation in two ways:

- Find out what people are saying. Do they see the consequences of the initiative in a positive or negative light? Discover important concerns related to the decision’s outcome so that you can address them, if necessary.

- Communicate. Outline what is known and not known. Explain the direction. Doing so helps reduce worry.

Including feelings as information

The idea that humans are logical beings is nice, but it’s not realistic. Although facts appeal to the rational mind, feelings guide what people do. Therefore, when you’re gathering information, you want to include the emotional environment. Doing so can provide valuable data.

You don’t find this kind of information in reports or data charts. You find it by making connections with people, being genuinely curious, and listening actively, with your mind — not your mouth — wide open.

Whether you use surveys combined with in-person relationships, engage in joint projects, or facilitate open lines of communication with employees and customers, you can follow these simple strategies to discover what matters to your employees and customers:

- Ask questions about what works and what doesn’t. If you’re testing a new product, the best way to elicit useful information is to give staff or potential customers the product and find out how it works for them both practically (“Did your clothes come out clean?”) and in terms of meeting values or specific preferences (“How did you feel about using the product?”). The responses offer insight into what works and what doesn’t for the market you’re reaching.

- Build trust with your employees so they don’t fear reprisal or punishment when they tell you things you’d rather not hear. Not every business owner is prepared to hear that he or she sounds like Attila the Hun. But you must be able to receive difficult-to-hear information without breaking down into a pool of tears or going into a fit of rage. Neither approach builds confidence or credibility.

- Engage with the community by building partnerships with local non-profits and other local businesses. Such partnerships provide a steady stream of information on what matters. For example, in the Sustainable Food Lab (

https://sustainablefoodlab.org/), companies partner with nonprofits to insert sustainable practices into the food supply chain. This large collaboration, in which the partners bring totally different mind-sets, develops internal leadership skills while simultaneously tackling a bigger issue.

Knowing when you have enough

Gathering information isn’t about feeling absolutely certain or waiting until everything is perfect before you act. It is about feeling 80 percent satisfied that you’ve looked at the situation from as many directions as possible and that you have enough information to make a good decision. Then you’re ready to move on. When determining how much information is enough, consider the following factors:

- The amount of time you have available: Stay open to new information until the full-stop deadline for making the final choice arrives.

- Whether you’re satisfied that you’ve asked enough questions and have enough information: You’ll know by answering the question, “Do we have enough information to analyze the merits of each option or scenario under consideration?” If your answer is yes, you’re good to go.

Sifting and Sorting Data: Analysis

After you gather information, the next step is to make sense of it. In short, it’s time to analyze the data. Factors that determine how you’ll proceed include how much time is available and whether you need to justify your decision to investors, customers, employees, or shareholders.

Conducting your analysis

Follow these steps to sort and analyze the information you’ve gathered:

-

Identify the facts, data, and raw numbers relevant to the decision and determine how you’ll crunch the numbers so they can inform the decision or selection of options.

Big data is the term given to the proliferation and abundance of data decision-makers must consider. Computer programs available for analyzing complex data include spatial, visual, and cloud-based presentations. For an example, see

Big data is the term given to the proliferation and abundance of data decision-makers must consider. Computer programs available for analyzing complex data include spatial, visual, and cloud-based presentations. For an example, see www.spatialdatamining.org/software. You can find a list of the top free data analysis software atwww.predictiveanalyticstoday.com/top-data-analysis-software/. -

Sort the social and emotional information into themes.

The themes can be trends (the direction for societal preferences), dynamics (the interrelationships that exist), and needs or preferences (which point to the underlying values that inform decisions), for example. These things tell you about what lies ahead so that you can predict what the response will be to your decision. Use them as a lens to identify what you need to consider in choosing options, or to ensure that you meet social and emotional needs during the implementation process.

-

Identify the considerations you see as relevant to either making the decision or implementing it.

To synthesize what’s important to consider in your decision-making, explore the facts (the rational-logical portion) and what is going on in the situation (feelings/emotions or relationships/social). Pull out the main ideas to use in subsequent steps. You can either use a mind map (a method to visually map related ideas) or you can tuck related ideas under the key points so you can see the relationships between the information you’ve gathered.

For example, if you were launching into a new market, as Target did into Canada, you’d want to ask Canadian customers what Target products they prefer. Customer preferences would be a theme; the product, price point, and customer expectations for service would form a part of the background decision-making.

-

Map out consequences — how the decision will affect staff, customers, employees, and suppliers, for example.

Knowing the consequences helps you make adjustments and informs what and how you’ll communicate any changes to your listeners, based on what they currently expect or are familiar with.

-

If you’re using a rational decision-making process, select criteria you’ll use to consider options before making a final selection.

You need to identify the criteria you’ll use to assess the options under consideration. Refer to the later section “Establishing and weighing criteria” for details.

By now, you’ll know which information is most relevant, whether you’re relying exclusively on analysis of the data or combining it with your intuitive know-how. If you’re making your decision purely intuitively, you’ll use what you perceive to be important and will rely on how the data is presented to pull out key points.

Critically evaluating your data

Mistakes get made when critical thinking isn’t applied. When you think critically, you become your own devil’s advocate, so to speak. You examine and reflect on your own thinking and question assumptions or conclusions. If you find critical thinking hard to do solo, enlist a colleague’s help or engage the entire team by doing some individual reflection first and then coming together to exchange observations.

To critically evaluate your data, ask these questions:

- What aren’t we saying? What are we overlooking?

- Where are we making assumptions, or what assumptions are we making?

- Where are we superimposing our own values and views on top of the information we are looking at?

- What could possibly go wrong?

Making assumptions intentionally … or not

Decisions get made all the time based on assumptions. Assumptions can be calculated guesses you make when you’re missing essential information, or they can be ideas you accept as true without proof and without thought. Depending on what kind of assumption you’re making — the educated-guess kind or the I-believe-it-just-because kind — assumptions can help or hinder your decision-making.

Using assumptions works under these conditions:

- You know you’re making them. When essential information is missing, you intentionally convert the unknowns into assumptions. Suppose, for example, that your office is planning to move to a larger location. You don’t have data regarding your company’s growth rate or the number of telecommuters it employs — information you need when determining which of the new sites has enough room to accommodate your work force. Therefore, you make the assumption that, over the next five years, the staff count will double and that telecommuters will be physically in the office one day each week. These assumptions let you fill in the blanks and move on.

- You adjust your assumptions as new data becomes available. As conditions change, you review your assumptions and adjust them to fit the emerging reality. If the information you needed in the first place becomes available, you can eliminate the assumption altogether.

Establishing and weighing criteria

In a rational decision-making process, you use the information you gather to establish criteria that specify what each of the alternatives under consideration must meet to accomplish your goal. You can create the criteria on your own (for personal decisions) or collectively, as you do when you work in a team or in a collaborative venture.

Establishing a list of criteria by which to judge the options in front of you offers benefits such as the following:

- Helps you think the decision through

- Brings the most practical alternatives to the surface

- Provides a clear structure that guides the evaluation process

- Helps the decision-making team agree on what it is looking for

- Makes the thinking behind your final choice visible, clear, and precise — which is especially important when you make decisions that are subject to open scrutiny

Criteria specify the conditions that must be met for an option to be considered. We explain how to establish and weigh criteria in this section.

Listing and sorting your criteria

Start by making a short yet complete list of the conditions that must be met. If you’re hiring, for example, list the criteria any viable candidate must have. You don’t want to be the company who hired a VP only to find out he is afraid of flying!

Sort the list items into one of the following two categories:

-

Must Haves category: Think of the Must Haves category as the go or no go category. The option being considered (or the candidate in the case of a hiring decision) either meets the criteria or doesn’t. If it meets the criteria, it moves on in the review process. If it doesn’t meet the criteria, it’s out.

Be sure to test the items on the Must Haves list to make sure list they’re essential. For example, imagine that you’re hiring a new sales manager, and you think a degree is essential. To test this criterion, ask, “If a candidate comes along who brings experience worth far more than a degree or who lacks a degree but has a proven track record, do we still reject that candidate because of his or her lack of degree?” If you say that you would still consider this candidate, even without the degree, the criterion of having a degree is comparative, not essential.

Be sure to test the items on the Must Haves list to make sure list they’re essential. For example, imagine that you’re hiring a new sales manager, and you think a degree is essential. To test this criterion, ask, “If a candidate comes along who brings experience worth far more than a degree or who lacks a degree but has a proven track record, do we still reject that candidate because of his or her lack of degree?” If you say that you would still consider this candidate, even without the degree, the criterion of having a degree is comparative, not essential. - Comparative category: The Comparative category holds the measures you’ll apply to options that pass through the first screen (the Must Haves). You assign each criterion a rating (weight) based on how important you or your team think it is. We explain how to assign and use ratings in the next section.

Weighing your criteria

Comparative criteria are usually assigned a weighting from 1 to 10, with 1 indicating not important and 10 indicating very important. (Anything below 6 probably isn’t important enough to be a criterion.) In this section, we give you two tools to help you apply criteria in your decision-making.

SCORING YOUR OPTIONS WITH A LITTLE MATH

When you’re considering several comparative criteria, each with a different relative importance, follow these steps to see how the different options stack up:

-

Create a table in which you list each comparative criterion and assign each a numeric value out of a total possible 10 points.

Importance, or relative value, is determined relative to the other criterion.

-

For each option being considered, assign a score assessing how well the option meets that criteria.

Measure each option against the criteria, scoring each by using the relative weighting you’ve assigned. If the comparative criteria has a high possible score of 8, for example, and the option under consideration fully meets the criteria, give it an 8. If it doesn’t meet the criteria, give it a lower score.

-

After you score each of the options, multiply the option’s score by the criterion’s relative value and — voila! — you have a final tally.

For example, if the relative value of a criterion is 8, and the option was scored a 6, the final tally is 48. Table 2-1 illustrates how to use criteria’s’ relative values to evaluate the options. Place the option at the top of the table and evaluate each alternative, using the scoring sheet. When you’re finished, you’ll have a score that tells you how well the option did against the criteria you set.

-

Add the scores for each option to get a total for each alternative.

Taking this extra step lets you compare, at a glance, the total scores to see which of all your options has the highest score.

TABLE 2-1 Scoring Option A — an Example

Criteria |

Relative Value |

Option #1 Score |

Final Tally for Option #1 |

User-friendly for the customer |

10 |

8 |

80 |

Easy to repeat |

8 |

5 |

40 |

Fits into an airplane storage space |

8 |

6 |

48 |

APPLYING THINKING TOOLS: THE PUGH MATRIX

The Pugh Matrix, designed by Professor Stuart Pugh, answers the question, “Which option will most improve what is in place now?” by including a baseline in the calculations used to weigh comparative criteria. The use of the baseline indicates whether the option will positively improve or negatively subtract from what is currently in place.

To use the Pugh Matrix, follow these steps:

-

Make a list of five or fewer of your most important criteria or conditions.

More than five and the list gets cumbersome. Ten is way too many.

-

As you consider each criterion and each option, ask, “Will the result be better or worse than the current system?”

If the option is better than the current system, assign it a +1. If it is worse, assign it a –1. Table 2-2 shows an example of the Pugh Matrix in action.

-

Tally the pluses and minuses to see which is the best option.

In this example, Option 3 dominates with three pluses and one minus, making it the logical choice.

TABLE 2-2 Assessing Options by Using the Pugh Matrix

Criteria |

Baseline (What We Have Now) |

Option 1 |

Option 2 |

Option 3 |

1 |

0 |

+1 |

–1 |

+1 |

2 |

0 |

+1 |

+1 |

–1 |

3 |

0 |

–1 |

–1 |

+1 |

4 |

0 |

–1 |

–1 |

+1 |

Avoiding analysis paralysis

An organization that delays making a decision for too long is most likely stuck in the analysis stage. If you were to ask why a decision hadn’t been made, you’d hear reasons such as, “There isn’t enough information,” or “Conditions are changing too quickly,” or “We have too many options to choose from.” The result? No decision is made or no option chosen.

Companies and people find themselves in this predicament for a few reasons:

- They overthink and overanalyze the information, the options, or the implications of the decision.

- They operate from an underlying fear of making a mistake.

- They are totally overwhelmed by uncertainty or internal chaos from too much change.

- They see either no clear option or far too many options to choose from.

How do you shift out of analysis paralysis? What can you do to restore employee morale? Start by recognizing that conditions are changing constantly. To regain control and pave a path that enables you to make concrete decisions and action plans, follow these suggestions:

- Identify decisions that are easy and ready to go, and take action. A bit of success will build momentum, and these low-stakes, low-risk decisions are not hard to implement. So take action on them.

- Make one decision at a time. Limiting yourself to one decision at a time allows for the smoke of confusion and frustration to clear. Solve one problem and then move on to the next.

-

Get a fresh new perspective on the decisions under consideration. Ask someone from outside the unit what he or she would do. Or change your environment to see the decision from a different context.

Research shows that more information doesn’t necessarily mean better decisions. Hesitating to make the decision because you don’t have the absolute best information is a trap. It means that you need to be perfect or right. Avoid it.

Research shows that more information doesn’t necessarily mean better decisions. Hesitating to make the decision because you don’t have the absolute best information is a trap. It means that you need to be perfect or right. Avoid it. - Trust in yourself and your colleagues. Working from a base of trust is much easier than working from a base of fear. Sure, it may require a leap of faith, but let go of hesitation and move forward. Although a bit unsettling initially, if you take gradual steps, you can help build momentum and restore confidence, and soon things will get rolling again.

Generating Options

In decision-making, the term options refers to the different alternatives or solutions under consideration. Whether you’re buying a computer, upgrading office space, or hiring an accountant, for example, you must decide which alternative offers the best solution. Some decisions, such as purchasing equipment, must result in the selection of only one out of several alternatives. Other decisions may benefit from working with more than one option simultaneously.

In this section, we explain how to come up with options, how to work with the risk of uncertainty, and what to do when you have too few or too many options to choose from.

Avoiding the one-option-only trap

When you’re making a decision, having only one option to consider isn’t really an option. When you focus on only one idea to address your dilemma, you face two risks: that your (or your team’s) tunnel vision has bypassed potentially better solutions and that any decision you make will keep you safely, and potentially stagnantly, in the status quo.

People think that they have only one choice for the following reasons:

- Narrow thinking: You consider only what has been done before, regardless of whether it’s worked. You disregard creative or unproven ideas.

- Fearful thinking: The decision is being triggered by fear, or the decision-making environment is characterized by fear or being afraid to take a risk.

Tapping into others’ creativity

The solution to overcoming narrow or fearful thinking is to reawaken and apply creativity. Seek ideas and additional options by involving employees, customers, suppliers, and other involved parties (and don’t forget to give credit where credit is due!). Tapping into additional sources’ creative ideas helps you avoid missing an optimal solution no one has thought of yet.

Brainstorming has long been used to come up with ideas, but in brainstorming, strong-willed people too often end up pressuring others to conform to one view — theirs! Because creative work is best accomplished privately — many brilliant ideas come up in the shower or when you’re gardening — we recommend that you take a different approach. Follow these steps:

-

Ask team members to identify one or more solutions on their own.

Independently coming up with ideas enables creative ideas to come forward that might otherwise not be heard in a group setting.

-

Collate potential solutions so that you have access to a wider range of possibilities.

Bringing the ideas together allows the team, whether working remotely or in the same location, to see which alternatives fit.

-

Discuss the merits of top ideas.

Bring the top ideas forward to work with. Solicit team members’ perspectives on which alternative appeals and why it has merit. Include any risks associated with the option, as well as its pros and cons.

Always consider dissenting views because they hold valued insights. Collaborating may result in creating a new solution or, at minimum, identifying the most viable alternatives.

Always consider dissenting views because they hold valued insights. Collaborating may result in creating a new solution or, at minimum, identifying the most viable alternatives. -

After discussion, short-list the alternatives — have participants select their top three choices, for example — and then gain consensus from the team.

An easy and reliable way to short-list is to use dot voting, in which you give participants dots (you can buy these little dots from stationary stores) that they then use to identify the alternative(s) they find most appealing.

Dot voting is a great way to rank ideas or to see where the preferences lie. It’s not used to make the final decision. Dot voting has several rules, such as how many dots you hand out (this number is based on how many people you’re working with and how many choices are under consideration) and whether you can let participants load up their dots on one idea (it’s generally a no-no!). For detailed instructions on dot voting, go to

Dot voting is a great way to rank ideas or to see where the preferences lie. It’s not used to make the final decision. Dot voting has several rules, such as how many dots you hand out (this number is based on how many people you’re working with and how many choices are under consideration) and whether you can let participants load up their dots on one idea (it’s generally a no-no!). For detailed instructions on dot voting, go to http://dotmocracy.org/dot-voting/.

At this point, you should have a short list of viable options that you keep open as you move forward.

Vetting your top options

If you’re using a criteria-based decision-making process, you can now match your options against the criteria you set earlier on. Refer to the earlier section “Establishing and weighing criteria” for details. Otherwise, you can select one or several to move forward on simultaneously. Keep reading for the details.

And the winner is! Selecting one option

Looking for one option or solution works best when you need only one solution, such as when you buy a software package, select a new location for your office, and so on. In these cases, you need to select the single, best option that meets your needs.

A super-rational decision-making process works well in predictable environments where the information isn’t moving at breakneck speed and you can take the time to deliberate. The process we outline in the earlier section “Establishing and weighting criteria” — especially in regards to using a scoring sheet or the Pugh Matrix to discover the best option in front of you — can help you do that.

Using scenario forecasting

In the case of project implementation or, at a higher level, determining strategic direction, new information pops up all the time. The situation is unpredictable and quite fluid. Selecting a single option to adhere to is like trying to put a foot down while the train is still moving. Instead, view your options as scenarios. Doing so helps in situations where there are multiple possibilities in fast-changing circumstances.

Scenario forecasting, an approach to risk management, is a way to keep options open by exploring scenarios and changing how you allocate resources. In scenario forecasting, you prepare for a world with multiple possible futures by creating a concrete plan for dealing with an abstract but probable future event.

When you use scenarios to prepare for future events, you’re truly thinking big and mitigating risk exposure. Fortune favors the prepared. Consider FedEx, for example, which relies on petroleum as its energy source. If the global forecast predicts a world shortage of petroleum, rising gas prices will increase FedEx’s risk of relying solely on one fuel source. By working through this kind of scenario — imagining a world in which petroleum is in short supply or imagining options that address the problems caused by a shortage of petroleum — FedEx can identify various ways to mitigate its risk. It may look at strategies that reduce energy use, identify reliable sources of alternative energy such as biofuels, or investigate other options that alleviate reliance on petroleum.

Assessing Immediate and Future Risk

Working with risk is risky. Although your mind can assess risk logically, psychologically, you handle risk in a totally different way. In this section, we explain how to calculate risk in your mind, look at how human psychology works when facing risk, and, finally, show you how to avoid underestimating risk.

Identifying risks

Calculating risk rationally engages your mind in a way that identifies the risk and assigns a value to how serious that risk is. Follow these steps:

-

Start by asking the question, “What can possibly go wrong?”

The answer identifies potential risks arising from different sources. These are unique to the situation. For instance, in bridge building, one way you’d use this lens is to uncover potential engineering flaws. In marketing, you’d use it to identify assumptions being made about the market.

-

Ask yourself, “What is the probability of this event happening?”

Assign the probability a high, medium, or low rating. This step separates the big risks from the tiny ones and helps you identify the likelihood that you’ll face the risk in reality.

If you detect a risk that is lying on the periphery of what everyone is paying attention to, name it.

If you detect a risk that is lying on the periphery of what everyone is paying attention to, name it. -

Identify the seriousness of the event’s effect on your business, using the high, medium, or low rating.

This step isolates the risks that may have a low probability of happening but very serious consequences if they do — a reactor failure in a nuclear power plant, for example. On the other hand, a number of risks may surface that have both high probability and high seriousness.

By looking at probability and seriousness together, you identify risks that you need to address in the decision-making process, either by making a contingency plan or by addressing the risk early on in the process to prevent it entirely or mitigate its effects.

-

Develop and incorporate ways to prevent, mitigate, or eliminate the risk into your decision-making process.

If you can’t prevent it, plan to have a backup plan. For instance, in the case of electrical outage, most buildings have a backup generator. How far you take efforts to mitigate risk depends on the seriousness of the consequences.

Considering people’s response to risk

When a risk is real, specific, concrete, or immediate, it is much easier to relate to. For instance, when you jaywalk across the street in a high traffic zone, the risk of being hit by a car is pretty real. Conversely, a risk that is possible but not tangible — such as the chance of needing trip interruption insurance — is treated differently. Why? Human psychology. Consider the following points:

- People naturally tend to focus on the tangible and discount the theoretical. In other words, you’re more likely to pay attention to a specific risk you’re facing in the moment than to anticipate a risk that may happen in the future. This tendency explains why attention goes to what actresses wear to the Oscars rather than rising sea levels, or why a contractor substitutes inferior, low-cost materials to meet budget rather than focus on probable future risk (the stability of the building and the possibility that the inferior product may fail).

-

Especially when making complex decisions, few people see unintended consequences, the unanticipated, wider effects that result from an action. Think of a spider web. If you jiggle one strand, the whole system is affected. The decisions you make can have similar effects. If you limit your attention to only one strand — that is, you make a decision looking only at one part of the whole picture — you won’t see how the strands are interconnected. Such tunnel vision causes decision-making errors.

When you see the big picture, you can more accurately identify the direct consequences of a decision and action plans, and you can predict the indirect effects. Doing so reduces the chance that you’ll be blindsided or make a decision that takes a nosedive. Use a mind-mapping process to see how a decision may play out and to see who will be affected directly and indirectly.

When you see the big picture, you can more accurately identify the direct consequences of a decision and action plans, and you can predict the indirect effects. Doing so reduces the chance that you’ll be blindsided or make a decision that takes a nosedive. Use a mind-mapping process to see how a decision may play out and to see who will be affected directly and indirectly. - People perceive the future as distant, unknown, and not concrete. Traditionally, the majority of companies have operated on the assumption that climate change wasn’t relevant to business sustainability over the longer term. The probability of climate change, given the way risk is assessed psychologically, has not traditionally been factored into decisions about how resources are used or the carbon footprint of business activity. Consequently, actions that could have reduced carbon outputs were not taken. Now, according to the Carbon Disclosure Project’s survey, S&P 500 companies estimate that 45 percent of the risk will surface in the next one to five years, with some costs of production already being felt. The effect of the psychological tendency to see potential futures as a slide show is that action is delayed, resulting in a higher cost later on.

Mapping the Consequences: Knowing Who Is Affected and How

Most decisions that backfire do so for two reasons:

- The people who must implement them aren’t involved in the decision-making.

- The decision fails to take into account the emotional needs and values of the customer (or anyone else affected by the implementation). These needs and values aren’t limited solely to the effect that the decision has on people. The effect of the decision on the environment and on the community the business resides in is also an important consideration.

A popular tool for mapping out whom or what the decision affects is a mind map (the brainchild of Tony Buzan, expert on the brain, memory, creativity, and innovation). Mind maps are incredibly useful because they help participants tap into both creative thinking and linear-logical thinking. Mind maps graphically represent the various aspects of a topic. In the case of decision-making, they can bring the pieces of the puzzle or process into one visible picture.

Making the Decision

An effective decision has these characteristics:

-

Reflects a positive attitude: Negativity is like glue. It slows everything down, saps energy, and undermines momentum. If your attitude is negative during the decision-making process, or if the decision-making environment is highly stressful, you’ll make a poor choice. Period.

Negative attitudes and critical thinking are not the same thing. Critical thinking improves a decision. Head to the earlier section “Critically evaluating your data” for an explanation of the difference.

Negative attitudes and critical thinking are not the same thing. Critical thinking improves a decision. Head to the earlier section “Critically evaluating your data” for an explanation of the difference. - Aligns what you think and how you feel about the final choice: Pushing forward because you feel obligated is draining. When your heart just isn’t in it, even if you think the idea is a good one, nothing happens, or if it does, it takes a lot of effort and can feel quite depleting.

- Balances your intuition with your rational, analytical work: Ideally, you want your gut and your mind working together, each providing a check and balance to the other. One entrepreneur told us, for example, that he’d been to an investor’s meeting where the pitch sounded good and the numbers looked sound, but he didn’t opt in because he had a bad feeling about the deal.

- Includes time to contemplate and reflect: Time can be your ally when you’re deciding on a course of action. Often the best ideas occur when you’re relaxed and doing something other than concentrating on the decision.

- Doubt: Doubt simply signals that a hidden fear is getting in your way. Ask yourself, “What’s the worry?” When you put the fear out in the open, you often find that the doubts and worry lose their power over you.

- Bias and prejudice: Prejudice and bias create a blind side, and you need help from others who can point out what you can’t see. To minimize the chances that unseen bias and prejudice are influencing your choices, notice when you’re leaning toward one solution or perspective over another.

Communicating the Decision Effectively

Transparency of information creates trust, which is important in business environments and vital when change is being made. Decisions made behind closed doors are always suspect. Therefore, after the decision is made, you need to communicate it. How you communicate the decision is everything. Basically, you want your message to summarize the decision you’ve made, why you’ve made it, and what it means for the audience you’re addressing. When you communicate your decision, include the following:

- The reason the decision was necessary: Include a brief summary of the opportunity or issue the decision and action plan address. Explain the “why.”

- The final decision: Pretty straightforward.

-

The implications: What the decision means to both your internal network and your customers or clientele. Address how the solutions will help and speak directly to the changes that these groups would be likely to see as losses.

Few things are worse than hearing that tired old phrase “Out with the old, in with the new.” People fear loss and change more than they value gain. Meeting emotional needs when you’re both making and communicating a decision is frequently overlooked but of vital importance. People are less interested in the decision itself and more interested in what that decision means to them.

Few things are worse than hearing that tired old phrase “Out with the old, in with the new.” People fear loss and change more than they value gain. Meeting emotional needs when you’re both making and communicating a decision is frequently overlooked but of vital importance. People are less interested in the decision itself and more interested in what that decision means to them. - What will happen next and what you need them to do to support the decision: Feedback and feed-forward information allows for adjusting to change.

Implementing the Decision

Finally — it’s time for action (as if you’ve been sitting around all this time)! Getting things done is where rational and logical thinking really delivers. So what do you do? You create an action plan. This section has the details.

Putting together your action plan

An action plan guides the implementation of the decision and helps monitor progress. The more complex the task, the more people involved and the more key activities and sub-activities are needed. In an action plan, you list the tasks that need to get done, identify the parties responsible for each task, set timelines for completion, and indicate what successful completion of a task looks like.

To put together your action plan, follow these steps:

-

Individually or collectively list all the steps that need to be accomplished to get the job done.

Involve the team and any other units that will be involved in the implementation of the decision. Doing so ensures that no task gets inadvertently left out.

If you’re doing this task in person, put one action step on a sticky note or 3-x-5-inch index card. Then you can rearrange them easily to get the timing and order worked out.

If you’re doing this task in person, put one action step on a sticky note or 3-x-5-inch index card. Then you can rearrange them easily to get the timing and order worked out. -

Set priorities.

Some actions are immediate and some can wait. To establish which decisions or parts of an action plan are more critical, set priorities. For additional information on priorities, refer to the next section.

-

Pull out higher-level action items and then rearrange the sub-activities so that each appears below the higher-level action with which it is associated.

The higher-level actions are like parents to the rest; taking care of them resolves other issues down the line. (The term parent-child refers to actions that are related to one another. By taking action on the parent, you look after the child. Noticing such relationships allows you to leverage your efforts.)

For instance, if you’re starting a company, the higher-level action may be to get the company legally registered. Sub-activities could include deciding what legal registration fits, generating and submitting names for the company so that your company’s name isn’t already taken, and so on.

This step lets you see how each sub-activity contributes toward your overall goal; it also helps you identify the tasks associated with each action step.

- For each task, indicate who is responsible for the task.

-

Set time frames for completion or, at minimum, checkpoints for review.

Avoid the label “ongoing,” which may lead people to assume that things are moving along on this action item when, in fact, it may be stalled or overlooked.

-

Define what the task will accomplish so that the endpoint is clear.

Agree on what successful completion will fulfill. Everyone involved in implementation needs to be on the same page, holding the same picture of what the result must accomplish so that everyone can adapt during implementation as conditions change.

- For a list of top ten free (open source) project management software programs, go to

www.cyberciti.biz/tips/open-source-project-management-software.html. - For programs for remote teams, visit

www.hongkiat.com/blog/project-management-software/. - For general project management programs, go to

https://www.softwareadvice.com/project-management/.

In addition, social collaboration tools help facilitate information exchange. A range of solutions is available, and new software products pop up all the time. Companies such as http://www.Nooq.co.uk facilitate rapid information exchange in small to medium-sized companies. IBM social platforms or Microsoft’s products, such as SharePoint, offer large-scale content management solutions. Go to http://mashable.com/2012/09/07/social-collaboration-tools/ for details.

Deciding what is important: Metrics

You’ve probably heard the business maxim, “What gets measured, gets managed.” In short, metrics matter. Establishing the measures you’ll use to track performance ensures you pay attention to what matters and to whom — the customer or internal operations. Choose the right metrics, and you get information that helps you make good decisions; choose the wrong metrics, and you may inadvertently create issues that you then have to deal with. In this section, we offer two examples of how your choice of metric can support or undermine your business goals.

Example 1: Customer service

Getting the metric right can take awhile, but knowing what you want to achieve is the place to start. Suppose, for example, that you work for a telecommunications company, and your company wants to improve customer retention. To achieve that goal, it targets the customer service function and decides to use length of call time as its metric, assuming that shortened call time will result in greater customer satisfaction and retention. Sounds reasonable, right? After all, no one likes being on a customer service line for what seems like an eternity.

Now put yourself in the customers’ shoes. Imagine being on a call with your mobile provider where your problem never got solved but they had you off the line in less than five minutes. Do you, as the customer, consider the call a success? Not a chance. If customer service performance is measured by the length of call time rather than whether the customer’s problem was successfully resolved, you have not improved customer satisfaction or retention, although you may have improved call time. The customer will be a long way from feeling delighted. In fact, you may have annoyed the customer so much that he looks for another provider.

Now suppose that the metric you use is whether the customer’s problem was solved to his or her satisfaction. Chances are your company would have happier customers who are more likely to continue to use your service.

Example 2: Employee retention

Suppose that you want to reduce turnover rate because you know that replacing people is costly. The metrics you use to measure the actual costs of losing an employee direct the focus of your efforts to retain people:

- Viewing the situation from a mathematical perspective: When an employee resigns, you can calculate the costs in a relatively simple mathematical equation:

- cost of one lost employee = that employee’s salary + replacement cost + training time

With this calculation, you may discover, for example, that having to replace an employee costs you 2.5 times the lost employee’s salary.

- Taking a holistic view of the costs: Note that the preceding equation misses the hidden costs. How much, for example, does it cost to replace the knowledge and experience that walked out the door? The lost clients? The customer loyalty to staff? The damage to your company’s reputation? These factors can’t be measured and yet are important for weighing how well things are working.

Setting priorities

To ensure that you do the tasks in the correct order and to allocate resources, which tend to be in chronically short supply in most businesses, you must set priorities. By setting priorities, you know what to pay attention to first and where to direction your attention so that you don’t try to do everything at once.

In establishing priorities, think in terms of these three categories:

- Essential (1): These action items must be started immediately after the decision and action plan are finalized. Indicate essential action items by using the number 1.

- Important (2): These action items are not essential but are still important to the overall success of the plan. Indicate these by using the number 2.

- Nice (3): Think of these action items as frosting on the cake. They’re not essential but would be nice to implement. Assign them a 3.

Learning from the implementation process

As the implementation of the decision unfolds, you’ll find yourself making adjustments to your plan due to practical and emerging realities as unintended consequences and changing conditions unfold.

Adapting to changing realities

As you implement your changes, monitor the consequences of the decision and adjust the implementation plan to reflect what is happening. Here are some suggestions:

- Pay attention to whether too many negative results show up and you find your red flags working overtime. So that you can adapt quickly to the emerging realities, try these tactics:

- Agree with the team ahead of time that any team member can call a review meeting in the event that a concern or opportunity to improve the action plan arises. During this meeting, the team can collectively decide how to respond to the changing conditions.

- Have a contingency plan ready. This is one way you can use the scenarios developed during your planning phase. You can also develop contingency plans out of your risk assessment. See the earlier section “Using scenario forecasting” for details.

- Treat unexpected occurrences as a potential opportunity to creatively improve the work you’re doing. Some unexpected events might be negative consequences, but a creative approach can convert a potential problem into a creative opportunity.

Reflecting on what happened

Unless you and your company are devoted to learning, you’ll fall into a pattern of recycling the same decisions over and over again. You can use self- and organizational awareness to avoid this fate. Companies that develop this awareness have a clear edge. One way to increase self- and organizational awareness is to take time for reflection. Following are two approaches:

-

For bigger decisions that went badly sideways, collectively reflect on each part of the decision-making process. Ask probing questions, such as

- What kind of thinking was applied (analytical, big picture, causal, and so on)?

- What assumptions were made?

- What questions weren’t asked?

- What flags were ignored?

Applying a critical and constructive review allows the organization to learn from the decision-making process.

- Schedule a time weekly or monthly to engage in reflection within the business unit. As a group, ask questions such as, “What do we need to stop (or start) doing?” and “What do we need to improve?” Then incorporate results back into your day-to-day work. This systematic method lets you stay on top of what’s going on and gives you an opportunity to identify actions that are habitual but useless as conditions change.

Decision-Making on Auto-Pilot

Most decisions happen instantly (the whole decision-making process may be over in milliseconds) and are made entirely without your conscious knowledge. When you don’t have time to consciously work through the decision-making process, what do you do — take a wild guess? No, you use your intuition.

Intuition is the ability to know or identify a solution without conscious thought. And where does this ability come from? One source is from experience you gain by making decisions, something called implicit knowledge. With implicit knowledge, the most recognized form of intuition, the more experience you have making decisions in diverse, complex, unstructured situations, the faster and more accurate your decisions are. In this section, we provide more details into how intuition works in both stable and highly volatile situations.

Grasping intuitive decision-making

When you’re under pressure, you may not have time to mentally generate different options, evaluate their practicality, and then choose one. You need to act quickly! Intuition equips you to make fast, accurate, and workable decisions in complex, dynamically changing, and unfamiliar conditions. Higher-level strategic decisions rely heavily on intuitive intelligence, for instance. Here is how your supercomputer, your intuition, operates:

- Processes incoming information at high speeds.

- Selects pertinent factual and situational information from a ton of data.

- Scans for cues and patterns you’ve come across before.

- Decides whether this situation is typical or unfamiliar.

- Runs scenarios from your inventory of what has worked before to see how the solution will play out in the current situation and then adjusts the solution to fit the situation.

- Chooses one and — shazaam! — the decision is made.

And it does all of this in milliseconds!

Examining intuition in different situations

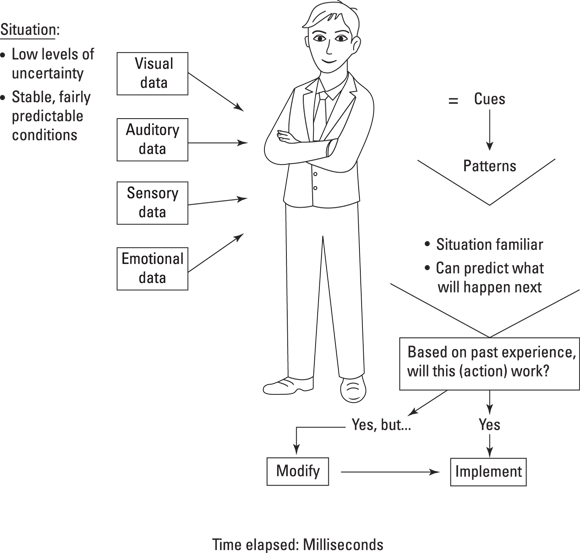

As the preceding steps indicate, part of the intuitive decision-making process is an assessment of whether the situation is typical or atypical. If the situation is typical, your supercomputer retrieves options that have worked before, rapidly tests them, scans them for weaknesses, and modifies them if necessary before selecting one. This process, described by Gary Klein in several of his books, most notably Streetlights and Shadows: Searching for the Keys to Adaptive Decision Making (Bradford), is illustrated in Figure 2-1.

FIGURE 2-1: Intuitive decision-making in stable, fairly predictable conditions.

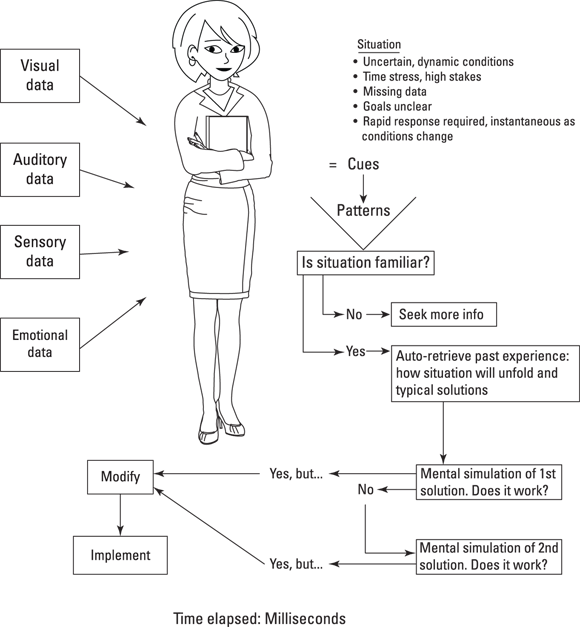

If the situation isn’t typical, your supercomputer goes into overdrive. This is where experience matters. Your internal supercomputer looks for more information until it senses that enough has been gathered, and then it runs through some scenarios to see which one will work, makes any necessary adjustments, and then the decision is made. Figure 2-2 shows this process.

FIGURE 2-2: Intuitive decision-making in highly dynamic, uncertain conditions.

Quite frankly, neuroscientists still aren’t sure how the brain selects the right information from so many signals. One thing is for sure: Intuition is efficient, and it works, especially when there isn’t any structure to lean on, when you aren’t really sure what will happen next, when conditions are volatile or ambiguous, and when there is an immediate reaction to events.

It’s easy to make the pain go away by taking action quickly before you truly understand the situation. Doing so can result in having to revisit the problem when the solution proves to be ineffective. Companies, for example, sometimes fix undesirable employee behavior by sending them off to training rather than exploring what is creating the situation in the system (culture) itself.

It’s easy to make the pain go away by taking action quickly before you truly understand the situation. Doing so can result in having to revisit the problem when the solution proves to be ineffective. Companies, for example, sometimes fix undesirable employee behavior by sending them off to training rather than exploring what is creating the situation in the system (culture) itself.