Chapter 3

Reporting Financial Condition in the Balance Sheet

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Reading the balance sheet

Reading the balance sheet

![]() Categorizing business transactions

Categorizing business transactions

![]() Connecting revenue and expenses with their assets and liabilities

Connecting revenue and expenses with their assets and liabilities

![]() Examining where businesses go for capital

Examining where businesses go for capital

![]() Understanding values in balance sheets

Understanding values in balance sheets

This chapter explores one of the three primary financial statements reported by business and not-for-profit entities: the balance sheet, which is also called the statement of financial condition and the statement of financial position. This financial statement summarizes the assets of a business and its liabilities and owners’ equity sources at a point in time. The balance sheet is a two-sided financial statement.

The balance sheet may seem to stand alone because it’s presented on a separate page in a financial report, but keep in mind that the assets and liabilities reported in a balance sheet are the results of the activities, or transactions, of the business. Transactions are economic exchanges between the business and the parties it deals with: customers, employees, vendors, government agencies, and sources of capital. The other two financial statements — the income statement and the statement of cash flows (see Book 1, Chapter 4) — report transactions, whereas the balance sheet reports values at an instant in time. The balance sheet is prepared at the end of the income statement period.

Unlike the income statement, the balance sheet doesn’t have a natural bottom line, or one key figure that’s the focus of attention. The balance sheet reports various assets, liabilities, and sources of owners’ equity. Cash is the most important asset, but other assets are important as well. Short-term liabilities are compared to cash and assets that can be converted into cash quickly. The balance sheet, as we explain in this chapter, has to be read as a whole — you can’t focus only on one or two items in this financial summary of the business. You shouldn’t put on blinders in reading a balance sheet by looking only at two or three items. You might miss important information by not perusing the whole balance sheet.

Expanding the Accounting Equation

The accounting equation is a condensed version of a balance sheet. In its most concise form, the accounting equation is as follows:

Figure 3-1 expands the accounting equation to identify the basic accounts reported in a balance sheet.

FIGURE 3-1: Expanded accounting equation.

Many of the balance sheet accounts you see in Figure 3-1 are introduced in Book 1, Chapter 2, which explains the income statement and the profit-making activities of a business. In fact, most balance sheet accounts are driven by profit-making transactions.

Presenting a Proper Balance Sheet

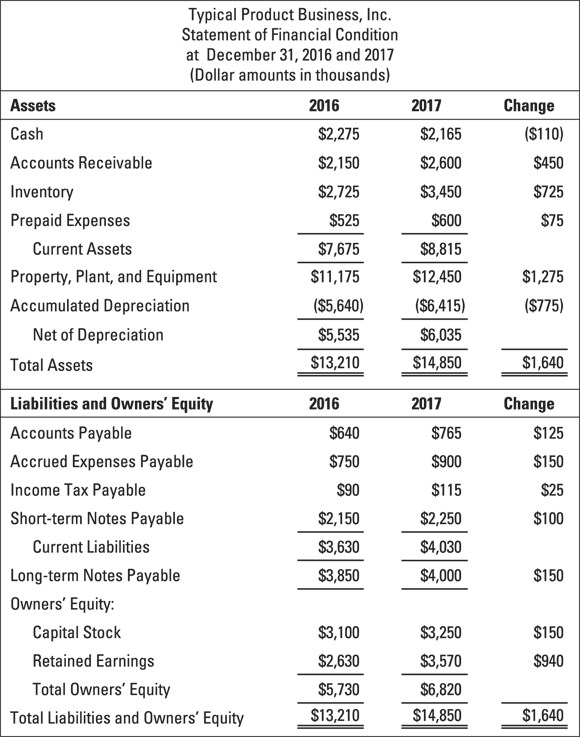

Figure 3-2 presents a two-year comparative balance sheet for the business example introduced in Chapter 2 of this minibook. This business sells products and makes sales on credit to its customers. The balance sheet is at the close of business, December 31, 2016 and 2017. In most cases, financial statements are not completed and released until a few weeks after the balance sheet date. Therefore, by the time you read this financial statement, it’s already somewhat out of date, because the business has continued to engage in transactions since December 31, 2017. When significant changes have occurred in the interim between the closing date of the balance sheet and the date of releasing its financial report, a business should disclose these subsequent developments in the footnotes to the financial statements.

FIGURE 3-2: Illustrative two-year comparative balance sheet for a product business.

The balance sheet in Figure 3-2 is in the vertical (portrait) layout, with assets on top and liabilities and owners’ equity on the bottom. Alternatively, a balance sheet may be in the horizontal (landscape) mode, with liabilities and owners’ equity on the right side and assets on the left.

Doing an initial reading of the balance sheet

Now suppose you own the business whose balance sheet is in Figure 3-2. (Most likely, you wouldn’t own 100 percent of the ownership shares of the business; you’d own the majority of shares, giving you working control of the business.) You’ve already digested your most recent annual income statement (refer to Book 1, Chapter 2’s Figure 2-1), which reports that you earned $1,690,000 net income on annual sales of $26,000,000. What more do you need to know? Well, you need to check your financial condition, which is reported in the balance sheet.

Is your financial condition viable and sustainable to continue your profit-making endeavor? The balance sheet helps answer this critical question. Perhaps you’re on the edge of going bankrupt, even though you’re making a profit. Your balance sheet is where to look for telltale information about possible financial troubles.

In reading through a balance sheet, you may notice that it doesn’t have a punchline like the income statement does. The income statement’s punchline is the net income line, which is rarely humorous to the business itself but can cause some snickers among analysts. (Earnings per share is also important for public corporations.) You can’t look at just one item on the balance sheet, murmur an appreciative “ah-ha,” and rush home to watch the game. You have to read the whole thing (sigh) and make comparisons among the items. Book 1, Chapter 5 offers information on interpreting financial statements.

At first glance, you might be somewhat alarmed that your cash balance decreased $110,000 during the year (refer to Figure 3-2). Didn’t you make a tidy profit? Why would your cash balance go down? Well, think about it. Many other transactions affect your cash balance. For example, did you invest in new long-term operating assets (called property, plant, and equipment in the balance sheet)? Yes you did, as a matter of fact. These fixed assets increased $1,275,000 during the year.

Overall, your total assets increased $1,640,000. All assets except cash increased during the year. One big reason is the $940,000 increase in your retained earnings owners’ equity. We explain in Book 1, Chapter 2 that earning profit increases retained earnings. Profit was $1,690,000 for the year, but retained earnings increased only $940,000. Therefore, part of profit was distributed to the owners, decreasing retained earnings. We discuss these things and other balance sheet interpretations as you move through the chapter. For now, the preliminary read of the balance sheet doesn’t indicate any earth-shattering financial problems facing your business.

Kicking balance sheets out into the real world

The statement of financial condition, or balance sheet, in Figure 3-2 is about as lean and mean as you’ll ever read. In the real world, many businesses are fat and complex. Also, we should make clear that Figure 3-2 shows the content and format for an external balance sheet, which means a balance sheet that’s included in a financial report released outside a business to its owners and creditors. Balance sheets that stay within a business can be quite different.

Internal balance sheets

As another example, the balance sheet in Figure 3-2 includes just one total amount for accounts receivable, but managers need details on which customers owe money and whether any major amounts are past due. Greater detail allows for better control, analysis, and decision-making. Internal balance sheets and their supporting schedules should provide all the detail that managers need to make good business decisions.

External balance sheets

Balance sheets presented in external financial reports (which go out to investors and lenders) don’t include a whole lot more detail than the balance sheet in Figure 3-2. However, as mentioned, external balance sheets must classify (or group together) short-term assets and liabilities. These are called current assets and current liabilities, as you see in Figure 3-2. Internal balance sheets for management use only don’t have to be classified if the managers don’t want the information.

Let us make clear that the NSA (National Security Agency) doesn’t vet balance sheets to prevent the disclosure of secrets that would harm national security. The term classified, when applied to a balance sheet, means that assets and liabilities are sorted into basic classes, or groups, for external reporting. Classifying certain assets and liabilities into current categories is done mainly to help readers of a balance sheet compare current assets with current liabilities for the purpose of judging the short-term solvency of a business.

Judging Liquidity and Solvency

If current liabilities become too high relative to current assets — which constitute the first line of defense for paying current liabilities — managers should move quickly to resolve the problem. A perceived shortage of current assets relative to current liabilities could ring alarm bells in the minds of the company’s creditors and owners.

Therefore, notice the following points in Figure 3-2 (dollar amounts refer to year-end 2017):

- Current assets: The first four asset accounts (cash, accounts receivable, inventory, and prepaid expenses) are added to give the $8,815,000 subtotal for current assets.

- Current liabilities: The first four liability accounts (accounts payable, accrued expenses payable, income tax payable, and short-term notes payable) are added to give the $4.03 million subtotal for current liabilities.

- Notes payable: The total interest-bearing debt of the business is divided between $2.25 million in short-term notes payable (those due in one year or sooner) and $4 million in long-term notes payable (those due after one year).

Read on for details on current assets and liabilities and on the current and quick ratios.

Current assets and liabilities

Short-term, or current, assets include the following:

- Cash

- Marketable securities that can be immediately converted into cash

- Assets converted into cash within one operating cycle, the main components being accounts receivable and inventory

The operating cycle refers to the repetitive process of putting cash into inventory, holding products in inventory until they’re sold, selling products on credit (which generates accounts receivable), and collecting the receivables in cash. In other words, the operating cycle is the “from cash, through inventory and accounts receivable, back to cash” sequence. The operating cycles of businesses vary from a few weeks to several months, depending on how long inventory is held before being sold and how long it takes to collect cash from sales made on credit.

Short-term, or current, liabilities include non-interest-bearing liabilities that arise from the operating (sales and expense) activities of the business. A typical business keeps many accounts for these liabilities — a separate account for each vendor, for example. In an external balance sheet, you usually find only three or four operating liabilities, and they aren’t labeled as non-interest-bearing. We assume that you know that these operating liabilities don’t bear interest (unless the liability is seriously overdue and the creditor has started charging interest because of the delay in paying the liability).

The balance sheet example in Figure 3-2 discloses three operating liabilities: accounts payable, accrued expenses payable, and income tax payable. Be warned that the terminology for these short-term operating liabilities varies from business to business.

In addition to operating liabilities, interest-bearing notes payable that have maturity dates one year or less from the balance sheet date are included in the current liabilities section. The current liabilities section may also include certain other liabilities that must be paid in the short run (which are too varied and technical to discuss here).

Current and quick ratios

The sources of cash for paying current liabilities are the company’s current assets. That is, current assets are the first source of money to pay current liabilities when these liabilities come due. Remember that current assets consist of cash and assets that will be converted into cash in the short run.

Generally, businesses do not provide their current ratio on the face of their balance sheets or in the footnotes to their financial statements — they leave it to the reader to calculate this number. On the other hand, many businesses present a financial highlights section in their financial report, which often includes the current ratio.

The quick ratio is more restrictive. Only cash and assets that can be immediately converted into cash are included, which excludes accounts receivable, inventory, and prepaid expenses. The business in this example doesn’t have any short-term marketable investments that could be sold on a moment’s notice, so only cash is included for the ratio. You compute the quick ratio as follows (see Figure 3-2):

Folklore has it that a company’s current ratio should be at least 2.0, and its quick ratio, 1.0. However, business managers know that acceptable ratios depend a great deal on general practices in the industry for short-term borrowing. Some businesses do well with current ratios less than 2.0 and quick ratios less than 1.0, so take these benchmarks with a grain of salt. Lower ratios don’t necessarily mean that the business won’t be able to pay its short-term (current) liabilities on time. Chapter 5 of this minibook explains solvency in more detail.

Understanding That Transactions Drive the Balance Sheet

This freeze-frame nature of a balance sheet may make it appear that a balance sheet is static. Nothing is further from the truth. A business doesn’t shut down to prepare its balance sheet. The financial condition of a business is in constant motion because the activities of the business go on nonstop.

Transactions change the makeup of a company’s balance sheet — that is, its assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity. The transactions of a business fall into three fundamental types:

-

Operating activities, which also can be called profit-making activities: This category refers to making sales and incurring expenses, and it also includes accompanying transactions that lead or follow the recording of sales and expenses. For example, a business records sales revenue when sales are made on credit and then, later, records cash collections from customers. The transaction of collecting cash is the indispensable follow-up to making the sale on credit.

For another example, a business purchases products that are placed in its inventory (its stock of products awaiting sale), at which time it records an entry for the purchase. The expense (the cost of goods sold) is not recorded until the products are actually sold to customers. Keep in mind that the term operating activities includes the associated transactions that precede or are subsequent to the recording of sales and expense transactions.

- Investing activities: This term refers to making investments in assets and (eventually) disposing of the assets when the business no longer needs them. The primary examples of investing activities for businesses that sell products and services are capital expenditures, which are the amounts spent to modernize, expand, and replace the long-term operating assets of a business. A business may also invest in financial assets, such as bonds and stocks or other types of debt and equity instruments. Purchases and sales of financial assets are also included in this category of transactions.

- Financing activities: These activities include securing money from debt and equity sources of capital, returning capital to these sources, and making distributions from profit to owners. Note that distributing profit to owners is treated as a financing transaction. For example, when a business corporation pays cash dividends to its stockholders, the distribution is treated as a financing transaction. The decision of whether to distribute some of its profit depends on whether the business needs more capital from its owners to grow the business or to strengthen its solvency. Retaining part or all of the profit for the year is one way of increasing the owners’ equity in the business. We discuss this topic later in “Financing a Business: Sources of Cash and Capital.”

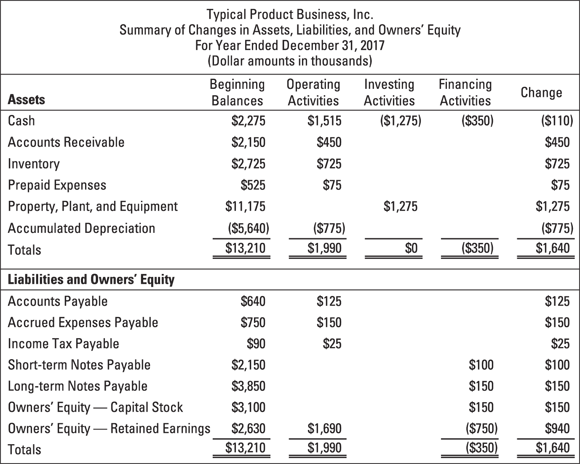

Figure 3-3 presents a summary of changes in assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity during the year for the business example introduced in Book 1, Chapter 2 and continued in this chapter. Notice the middle three columns, which show each of the three basic types of transactions of a business. One column is for changes caused by its revenue and expenses and their connected transactions during the year, which collectively are called operating activities (although we prefer to call them profit-making activities). The second column is for changes caused by its investing activities during the year. The third column is for the changes caused by its financing activities.

FIGURE 3-3: Summary of changes in assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity during the year according to basic types of transactions.

Note: Figure 3-3 doesn’t include subtotals for current assets and liabilities; the formal balance sheet for this business is in Figure 3-2. Businesses don’t report a summary of changes in their assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity (though we think such a summary would be helpful to users of financial reports). The purpose of Figure 3-3 is to demonstrate how the three major types of transactions during the year change the assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity accounts of the business during the year.

The 2017 income statement of the business is shown in Book 1, Chapter 2’s Figure 2-1. You may want to flip back to this financial statement. On sales revenue of $26 million, the business earned $1.69 million bottom-line profit (net income) for the year. The sales and expense transactions of the business during the year plus the associated transactions connected with sales and expenses cause the changes shown in the operating-activities column in Figure 3-3. You can see that the $1.69 million net income has increased the business’s owners’ equity–retained earnings by the same amount. (The business paid $750,000 distributions from profit to its owners during the year, which decreases the balance in retained earnings.)

The summary of changes in Figure 3-3 gives you a sense of the balance sheet in motion, or how the business got from the start of the year to the end of the year. Having a good sense of how transactions propel the balance sheet is important. This kind of summary of balance sheet changes can be helpful to business managers who plan and control changes in the assets and liabilities of the business. Managers need a solid understanding of how the three basic types of transactions change assets and liabilities. Figure 3-3 also provides a useful platform for the statement of cash flow in Book 1, Chapter 4.

Sizing Up Assets and Liabilities

Although the business example we use in this chapter is hypothetical, we didn’t make up the numbers at random. We use a modest-sized business that has $26 million in annual sales revenue. The other numbers in its income statement and balance sheet are realistic relative to each other. We assume that the business earns 45 percent gross margin ($11.7 million gross margin ÷ $26 million sales revenue = 45 percent), which means its cost of goods sold expense is 55 percent of sales revenue. The sizes of particular assets and liabilities compared with their relevant income statement numbers vary from industry to industry and even from business to business in the same industry.

Based on the business’s history and operating policies, the managers of a business can estimate what the size of each asset and liability should be; these estimates provide useful control benchmarks to which the actual balances of the assets and liabilities are compared. Assets (and liabilities, too) can be too high or too low relative to the sales revenue and expenses that drive them, and these deviations can cause problems that managers should try to remedy.

For example, based on the credit terms extended to its customers and the company’s actual policies regarding how aggressively it acts in collecting past-due receivables, a manager determines the range for the proper, or within-the-boundaries, balance of accounts receivable. This figure is the control benchmark. If the actual balance is reasonably close to this control benchmark, accounts receivable is under control. If not, the manager should investigate why accounts receivable is smaller or larger than it should be.

This section discusses the relative sizes of the assets and liabilities in the balance sheet that result from sales and expenses (for the fiscal year 2017). The sales and expenses are the drivers, or causes, of the assets and liabilities. If a business earned profit simply by investing in stocks and bonds, it wouldn’t need all the various assets and liabilities explained in this chapter. Such a business — a mutual fund, for example — would have just one income-producing asset: investments in securities. This chapter focuses on businesses that sell products on credit.

Sales revenue and accounts receivable

Annual sales revenue for the year 2017 is $26 million in our example (see Book 1, Chapter 2’s Figure 2-1). The year-end accounts receivable is one-tenth of this, or $2.6 million (see Figure 3-2). So the average customer’s credit period is roughly 36 days: 365 days in the year times the 10 percent ratio of ending accounts receivable balance to annual sales revenue. Of course, some customers’ balances are past 36 days, and some are quite new; you want to focus on the average. The key question is whether a customer credit period averaging 36 days is reasonable.

Suppose that the business offers all customers a 30-day credit period, which is common in business-to-business selling (although not for a retailer selling to individual consumers). The relatively small deviation of about 6 days (36 days average credit period versus 30 days normal credit terms) probably isn’t a significant cause for concern. But suppose that, at the end of the period, the accounts receivable had been $3.9 million, which is 15 percent of annual sales, or about a 55-day average credit period. Such an abnormally high balance should raise a red flag; the responsible manager should look into the reasons for the abnormally high accounts receivable balance. Perhaps several customers are seriously late in paying and shouldn’t be extended new credit until they pay up.

Cost of goods sold expense and inventory

In the example, the cost of goods sold expense for the year 2017 is $14.3 million. The year-end inventory is $3.45 million, or about 24 percent. In rough terms, the average product’s inventory holding period is 88 days — 365 days in the year times the 24 percent ratio of ending inventory to annual cost of goods sold. Of course, some products may remain in inventory longer than the 88-day average, and some products may sell in a much shorter period than 88 days. You need to focus on the overall average. Is an 88-day average inventory holding period reasonable?

The managers should know what the company’s average inventory holding period should be — they should know what the control benchmark is for the inventory holding period. If inventory is much above this control benchmark, managers should take prompt action to get inventory back in line (which is easier said than done, of course). If inventory is at abnormally low levels, this should be investigated as well. Perhaps some products are out of stock and should be restocked to avoid lost sales.

Fixed assets and depreciation expense

Depreciation is like other expenses in that all expenses are deducted from sales revenue to determine profit. Other than this, however, depreciation is different from most other expenses. (Amortization expense, which we get to later, is a kissing cousin of depreciation.) When a business buys or builds a long-term operating asset, the cost of the asset is recorded in a specific fixed asset account. Fixed is an overstatement; although the assets may last a long time, eventually they’re retired from service. The main point is that the cost of a long-term operating or fixed asset is spread out, or allocated, over its expected useful life to the business. Each year of use bears some portion of the cost of the fixed asset.

The depreciation expense recorded in the period doesn’t require any cash outlay during the period. (The cash outlay occurred when the fixed asset was acquired, or perhaps later when a loan was secured for part of the total cost.) Rather, depreciation expense for the period is that quota of the total cost of a business’s fixed assets that is allocated to the period to record the cost of using the assets during the period. Depreciation depends on which method is used to allocate the cost of fixed assets over their estimated useful lives.

The higher the total cost of a business’s fixed assets (called property, plant, and equipment in a formal balance sheet), the higher its depreciation expense. However, there’s no standard ratio of depreciation expense to the cost of fixed assets. The annual total depreciation expense of a business seldom is more than 10 to 15 percent of the original cost of its fixed assets. Either the depreciation expense for the year is reported as a separate expense in the income statement, or the amount is disclosed in a footnote.

In the example in this chapter, the business has, over several years, invested $12,450,000 in its fixed assets (that it still owns and uses), and it has recorded total depreciation of $6,415,000 through the end of the most recent fiscal year, December 31, 2017. The business recorded $775,000 depreciation expense in its most recent year.

You can tell that the company’s collection of fixed assets includes some old assets because the company has recorded $6,415,000 total depreciation since assets were bought — a fairly sizable percent of original cost (more than half). But many businesses use accelerated depreciation methods that pile up a lot of the depreciation expense in the early years and less in the back years, so it’s hard to estimate the average age of the company’s assets. A business could discuss the actual ages of its fixed assets in the footnotes to its financial statements, but hardly any businesses disclose this information — although they do identify which depreciation methods they’re using.

Operating expenses and their balance sheet accounts

The sales, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses of a business connect with three balance sheet accounts: the prepaid expenses asset account, the accounts payable liability account, and the accrued expenses payable liability account (see Figure 3-2). The broad SG&A expense category includes many types of expenses in making sales and operating the business. (Separate detailed expense accounts are maintained for specific expenses; depending on the size of the business and the needs of its various managers, hundreds or thousands of specific expense accounts are established.)

Many expenses are recorded when paid. For example, wage and salary expenses are recorded on payday. However, this record-as-you-pay method doesn’t work for many expenses. For example, insurance and office supplies costs are prepaid and then released to expense gradually over time. The cost is initially put in the prepaid expenses asset account. (Yes, we know that prepaid expenses doesn’t sound like an asset account, but it is.) Other expenses aren’t paid until weeks after the expenses are recorded. The amounts owed for these unpaid expenses are recorded in an accounts payable or in an accrued expenses payable liability account.

For details regarding the use of these accounts in recording expenses, see Book 1, Chapter 2. Remember that the accounting objective is to match expenses with sales revenue for the year, and only in this way can the amount of profit be measured for the year. So expenses recorded for the year should be the correct amounts, regardless of when they’re paid.

Intangible assets and amortization expense

Although our business example doesn’t include tangible assets, many businesses invest in them. Intangible means without physical existence, in contrast to tangible assets like buildings, vehicles, and computers. Here are some examples of intangible assets:

- A business may purchase the customer list of another company that’s going out of business.

- A business may buy patent rights from the inventor of a new product or process.

- A business may buy another business lock, stock, and barrel and may pay more than the individual assets of the company being bought are worth — even after adjusting the particular assets to their current values. The extra amount is for goodwill, which may consist of a trained and efficient workforce, an established product with a reputation for high quality, or a valuable location.

The cost of an intangible asset is recorded in an appropriate asset account, just like the cost of a tangible asset is recorded in a fixed asset account. Whether or when to allocate the cost of an intangible asset to expense has proven to be a difficult issue in practice, not easily amenable to accounting rules. At one time, the cost of most intangible assets were charged off according to some systematic method. The fraction of the total cost charged off in one period is called amortization expense.

Currently, however, the cost of an intangible asset isn’t charged to expense unless its value has been impaired. A study of 8,700 public companies found that they collectively recorded $26 billion of write-downs for goodwill impairment in 2014. Testing for impairment is a messy process. The practical difficulties of determining whether impairment has occurred and the amount of the loss in value of an intangible asset have proven to be a real challenge to accountants. For the latest developments, search for impairment of intangible assets on the Internet, which will lead you to several sources. We don’t go into the technical details here; because our business example doesn’t include any intangible assets, there’s no amortization expense.

Debt and interest expense

Look back at the balance sheet shown in Figure 3-2. Notice that the sum of this business’s short-term (current) and long-term notes payable at year-end 2017 is $6.25 million. From the income statement in Book 1, Chapter 2’s Figure 2-1, you see that the business’s interest expense for the year is $400,000. Based on the year-end amount of debt, the annual interest rate is about 6.4 percent. (The business may have had more or less borrowed at certain times during the year, of course, and the actual interest rate depends on the debt levels from month to month.)

For most businesses, a small part of their total annual interest is unpaid at year-end; the unpaid part is recorded to bring interest expense up to the correct total amount for the year. In Figure 3-2, the accrued amount of interest is included in the accrued expenses payable liability account. In most balance sheets, you don’t find accrued interest payable on a separate line; rather, it’s included in the accrued expenses payable liability account. However, if unpaid interest at year-end happens to be a rather large amount, or if the business is seriously behind in paying interest on its debt, it should report the accrued interest payable as a separate liability.

Income tax expense and income tax payable

In its 2017 income statement, the business reports $2.6 million earnings before income tax — after deducting interest and all other expenses from sales revenue. The actual taxable income of the business for the year probably is different from this amount because of the many complexities in the income tax law. In the example, we use a realistic 35 percent tax rate, so the income tax expense is $910,000 of the pretax income of $2.6 million.

A large part of the federal and state income tax amounts for the year must be paid before the end of the year. But a small part is usually still owed at the end of the year. The unpaid part is recorded in the income tax payable liability account, as you see in Figure 3-2. In the example, the unpaid part is $115,000 of the total $910,000 income tax for the year, but we don’t mean to suggest that this ratio is typical. Generally, the unpaid income tax at the end of the year is fairly small, but just how small depends on several technical factors.

Net income and cash dividends (if any)

The business in our example earned $1.69 million net income for the year (see Book 1, Chapter 2’s Figure 2-1). Earning profit increases the owners’ equity account retained earnings by the same amount. Either the $1.69 million profit (here we go again using profit instead of net income) stays in the business, or some of it is paid out and divided among the owners of the business.

During the year, the business paid out $750,000 total cash distributions from its annual profit. This is included in Figure 3-3’s summary of transactions — look in the financing-activities column on the retained earnings line. If you own 10 percent of the shares, you’d receive one-tenth, or $75,000 cash, as your share of the total distributions. Distributions from profit to owners (shareholders) are not expenses. In other words, bottom-line net income is before any distributions to owners. Despite the importance of distributions from profit, you can’t tell from the income statement or the balance sheet the amount of cash dividends. You have to look in the statement of cash flows for this information (which we explain in Book 1, Chapter 4). You can also find distributions from profit (if any) in the statement of changes in stockholders’ equity.

Financing a Business: Sources of Cash and Capital

How did the business whose balance sheet is shown in Figure 3-2 finance its assets? Its total assets are $14,850,000 at fiscal year-end 2017. The company’s profit-making activities generated three liabilities — accounts payable, accrued expenses payable, and income tax payable — and in total these three liabilities provided $1,780,000 of the total assets of the business. Debt provided $6,250,000, and the two sources of owners’ equity provided the other $6,820,000. All three sources add up to $14,850,000, which equals total assets, of course. Otherwise, its books would be out of balance, which is a definite no-no.

Accounts payable, accrued expenses payable, and income tax payable are short-term, non-interest-bearing liabilities that are sometimes called spontaneous liabilities because they arise directly from a business’s expense activities — they aren’t the result of borrowing money but rather are the result of buying things on credit or delaying payment of certain expenses.

It’s hard to avoid these three liabilities in running a business; they’re generated naturally in the process of carrying on operations. In contrast, the mix of debt (interest-bearing liabilities) and equity (invested owners’ capital and retained earnings) requires careful thought and high-level decisions by a business. There’s no natural or automatic answer to the debt-versus-equity question. The business in the example has a large amount of debt relative to its owners’ equity, which would make many business owners uncomfortable.

Debt is both good and bad, and in extreme situations, it can get very ugly. The advantages of debt are as follows:

- Most businesses can’t raise all the capital they need from owners’ equity sources, and debt offers another source of capital (though, of course, many lenders are willing to provide only part of the capital that a business needs).

- Interest rates charged by lenders are lower than rates of return expected by owners. Owners expect a higher rate of return because they’re taking a greater risk with their money — the business isn’t required to pay them back the same way that it’s required to pay back a lender. For example, a business may pay 6 percent annual interest on its debt and be expected to earn a 12 percent annual rate of return on its owners’ equity. (See Book 1, Chapter 5 for more on earning profit for owners.)

Here are the disadvantages of debt:

- A business must pay the fixed rate of interest for the period even if it suffers a loss for the period or earns a lower rate of return on its assets.

- A business must be ready to pay back the debt on the specified due date, which can cause some pressure on the business to come up with the money on time. (Of course, a business may be able to roll over or renew its debt, meaning that it replaces its old debt with an equivalent amount of new debt, but the lender has the right to demand that the old debt be paid and not rolled over.)

Recognizing the Hodgepodge of Values Reported in a Balance Sheet

In our experience, the values reported for assets in a balance sheet can be a source of confusion for business managers and investors, who tend to put all dollar amounts on the same value basis. In their minds, a dollar is a dollar, whether it’s in accounts receivable; inventory; property, plant, and equipment; accounts payable; or retained earnings. But some dollars are much older than other dollars.

The dollar amounts reported in a balance sheet are the result of the transactions recorded in the assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity accounts. (Hmm, where have you heard this before?) Some transactions from years ago may still have life in the present balances of certain assets. For example, the land owned by the business that is reported in the balance sheet goes back to the transaction for the purchase of the land, which could be 20 or 30 years ago. The balance in the land asset is standing in the same asset column, for example, as the balance in the accounts receivable asset, which likely is only 1 or 2 months old.

Also, keep in mind that a business may have unrecorded assets. These off-balance-sheet assets include such things as a well-known reputation for quality products and excellent service, secret formulas (think Coca-Cola here), patents that are the result of its research and development over the years, and a better trained workforce than its competitors. These are intangible assets that the business did not purchase from outside sources but, rather, accumulated over the years through its own efforts. These assets, though not reported in the balance sheet, should show up in better-than-average profit performance in the business’s income statement.

Businesses are not permitted to write up the book values of their assets to current market or replacement values. (Well, investments in marketable securities held for sale or available for sale have to be written up, or down, but this is an exception to the general rule.) Although recording current market values may have intuitive appeal, a market-to-market valuation model isn’t practical or appropriate for businesses that sell products and services. These businesses do not stand ready to sell their assets (other than inventory); they need their assets for operating the business into the future. At the end of their useful lives, assets are sold for their disposable values (or traded in for new assets).

Don’t think that the market value of a business is simply equal to its owners’ equity reported in its most recent balance sheet. Putting a value on a business depends on several factors in addition to the latest balance sheet of the business.

Certain balance sheet accounts are not involved in recording the profit-making transactions of a business. Short- and long-term debt accounts aren’t used in recording revenue and expenses, and neither is the invested capital account, which records the investment of capital from the owners of the business. Transactions involving debt and owners’ invested capital accounts have to do with financing the business — that is, securing the capital needed to run the business.

Certain balance sheet accounts are not involved in recording the profit-making transactions of a business. Short- and long-term debt accounts aren’t used in recording revenue and expenses, and neither is the invested capital account, which records the investment of capital from the owners of the business. Transactions involving debt and owners’ invested capital accounts have to do with financing the business — that is, securing the capital needed to run the business. If a business doesn’t release its annual financial report within a few weeks after the close of its fiscal year, you should be alarmed. The reasons for such a delay are all bad. One reason might be that the business’s accounting system isn’t functioning well and the controller (chief accounting officer) has to do a lot of work at year-end to get the accounts up to date and accurate for preparing its financial statements. Another reason is that the business is facing serious problems and can’t decide on how to account for the problems. Perhaps a business is delaying the reporting of bad news. Or the business may have a serious dispute with its independent CPA auditor that hasn’t been resolved.

If a business doesn’t release its annual financial report within a few weeks after the close of its fiscal year, you should be alarmed. The reasons for such a delay are all bad. One reason might be that the business’s accounting system isn’t functioning well and the controller (chief accounting officer) has to do a lot of work at year-end to get the accounts up to date and accurate for preparing its financial statements. Another reason is that the business is facing serious problems and can’t decide on how to account for the problems. Perhaps a business is delaying the reporting of bad news. Or the business may have a serious dispute with its independent CPA auditor that hasn’t been resolved. The balance sheet in

The balance sheet in