CHAPTER 15

The Importance of the Incident Response Process

In this chapter you will learn:

• The importance of establishing communications processes

• Which factors contribute to data criticality

• How unauthorized disclosure may create serious adverse effects

I am prepared for the worst, but hope for the best.

—Benjamin Disraeli

While it’s hard to predict when and how an incident will occur, it’s certain that it will happen at some point. Good security teams will have taken measures to minimize the likelihood of an incident by hardening the network and addressing vulnerabilities, but great teams will go a step further and outline the exact steps necessary to address an incident when the time comes. The activities necessary to accomplish the goals of detecting and recovering from an incident are collectively referred to as the incident response process. For it to be effective, the overall process should be well documented, tailored to your organization, and well understood by all stakeholders across the organization, from your response team to public relations to the C-suite. Each incident starts with the detection of some potentially malicious security event—an event which may generate an alert that may require further investigation, analysis, and remediation. A well-designed IR process makes it more likely that your organization moves efficiently from initial detection to resumption of normal operations, while also keeping stakeholder apprised of progress.

Establishing a Communication Process

A variety of team members and stakeholders are involved in incident responses, each with different capabilities and priorities. Maintaining effective communications with them all can help you make the experience of responding to an incident far more manageable. Ineffective communication processes with internal and/or external stakeholders can endanger your entire organization, even if you have a textbook-perfect response to an incident.

We cannot be exhaustive in our treatment of how best to communicate during incident responses in this chapter, but we hope to convey the importance of interpersonal and interorganizational communications in these few pages. Even the best-handled technical incident response can be overshadowed very quickly by an organization’s inability to communicate effectively—internally and/or externally.

Internal Communications

One of the key parts of any incident response plan is the process by which trusted internal parties are kept abreast of and consulted about an incident and how it will be dealt with. It is not uncommon, at least for the more significant incidents, to designate a war room where key decision-makers and stakeholders can meet for periodic updates and feedback regarding the incident response. In between these meetings, the room can serve as a clearinghouse for information about the response activities, where at least one knowledgeable member of the incident response (IR) team will be stationed for the duration of the response activity. The war room can be a physical space, but a virtual one may work as well, depending on your organization.

In addition to hosting regular meetings (formal or otherwise) in the war room, it may be necessary to establish a secure communications channel with which to keep key personnel up-to-date on the progress of the response. This could involve group texts, e-mails, or a chat room—but it must include all the key personnel who may have a role or stake in the issue. When it comes to internal communications with stakeholders after an incident, there is no such thing as too much information.

External Communications

Communications outside of the organization, on the other hand, must be carefully controlled. Sensible reports have a way of getting turned into misleading and potentially damaging sound bites. For this reason, a trained professional should be assigned the role of handling external communications. Some of these communications, after all, may be restricted by regulatory or statutory requirements.

The first and most important sector for external communications comprises government entities, which could include the US Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), or some other government entity. If your organization is required to communicate with these entities in the course of an incident response, your legal team must assist in crafting any and all messages. If you manage to ignore these communication requirements, your organization will pay a price. This is not to say that government stakeholders are adversarial, but that when the process is regulated by laws or regulations, the stakes are much higher.

Next on the list of importance are customers. Though your organization may be affected by regulatory requirements with regard to compromised customer data, our focus here is on keeping the public informed so that it perceives transparency and trustworthiness from the organization. This is particularly important when the situation is interesting enough to make headlines or “go viral” on social media. Just as lawyers are critical to government communications, the organization’s media relations (or equivalent) team will carry the day when it comes to communicating with the masses. The goal here is to assuage fears and concerns as well as control the narrative to keep it factually correct. To this end, press releases and social media posts should be templated even before an event occurs to make it easier to push out information quickly.

Another group with which we may have to communicate deliberately and effectively includes the key partners, such as business collaborators, select shareholders, and investors. The goal of this communications thrust is to convey the impact of the incident on the business’s bottom line. If the event could drive down the price of the company’s stock, the conversation has to include ways in which the company will mitigate such losses. If the event could spread to the systems of partner organizations, the focus should be on how to mitigate that risk. In any event, the business leaders should carry on these conversations, albeit with substantial support from the senior response team leaders.

Response Coordination with Relevant Entities

In the midst of an incident response, it is all too easy to get so focused on the technical challenges that we forget about the human element, which is arguably at least as important. Here, we focus our discussion on the various roles involved and the manner in which we must ensure that these roles are communicating effectively with one another and with those outside the organization.

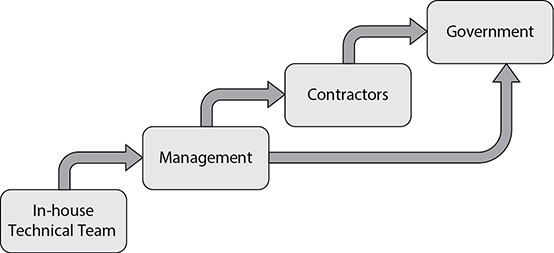

The key roles required in incident responses can be determined beforehand based on established escalation thresholds. The in-house technical team will always be involved, of course, but when and how are others brought in? This depends on the analysis that your organization performed as part of developing the IR plan. Figure 15-1 shows a typical escalation model used by many organizations.

Figure 15-1 Typical role escalation model

The technical team is unlikely to involve management in routine responses, such as a response to an e-mail with a malicious link or attachment that somehow gets to a user’s inbox, but is not clicked. You still have to respond to this and will probably notify others (such as the user, supervisor, and threat intelligence team) of the attempt, but management will not be in the loop at every step of the response. The situation is different, however, when the incident or response has a direct impact on the organization, such as when you have to reboot a production server to eradicate malware installed on it. Management needs to be closely involved in decision-making in this more serious scenario.

At some point, the skills and abilities of the in-house team will probably be insufficient to deal effectively with an incident; this is when the response is escalated and you bring in contractors to augment your team or even take over aspects of the response. Obviously, this is an expensive move, so you want to consider this option carefully, and management will almost certainly be involved in that decision. Finally, some incidents require government involvement. Typically, though not always, this comes in the form of notifying and perhaps bringing in a law enforcement agency such as the FBI or Secret Service. This may happen with or without your organization calling in external contractors, but it will always involve senior leadership. Whatever the process, it’s important to publish the specific escalation paths for your analysts and maintain a call list, or contact information for those required to be notified or involved in case of an incident. Let’s take a look at some of the issues involved with each of the roles involved.

The term stakeholder is broad and could include a very large set of people. Each stakeholder has a critical role to play in some (maybe even most), but not all, responses. These supporting stakeholders normally will not be accustomed to executing response operations, as the direct players are. You and the IR team must make extra efforts to ensure that each stakeholder knows what to do and how to do it when bad things happen.

Legal Counsel

Whenever an incident response escalates to the point of involving government agencies such as law enforcement, you will almost certainly be coordinating with your organization’s legal counsel. Apart from requirements to report criminal or state-sponsored attacks on your systems, your organization may be affected by regulatory considerations such as those discussed in Chapter 5. For instance, if you work in an organization covered by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and you are responding to an incident that compromised the protected health information (PHI) of 500 or more people, your organization will have some very specific reporting requirements that will have to be reviewed by your legal and/or compliance team(s).

The law is a remarkably complicated field, so even actions that may seem innocuous to many of us can have some onerous legal implications. Though some lawyers are very knowledgeable in complex technological and cybersecurity issues, most have only a cursory familiarity with them. In our experience, starting a dialogue early with the legal team and then maintaining a regular, ongoing conversation are critical to staying out of career-ending trouble.

Human Resources

The likeliest involvement of human resources (HR) staff in a response occurs when the team determines that a member of the organization probably had a role in the incident. The role need not be malicious, mind you, because it could involve a failure to comply with policies (for example, connecting a thumb drive into a computer when that is not allowed) or repeated failures to apply security awareness training (for example, clicking a link in an e-mail even after a few rounds of remedial security training). Malicious, careless, or otherwise, the actions of our teammates can and do lead to serious incidents. Disciplinary action in those cases requires HR involvement.

In other situations, as well, you may need to involve HR in the response, such as when overtime is required to deal with the response, or when key people need to be called in from time off or vacation. The safest bet is to involve HR in your IR planning process and especially in your drills, and let them tell you what, if any, involvement they should have in various scenarios.

Public Relations

Managing communications with your customers and investors is critical to recovering from an incident successfully. What, when, and how you divulge information is of strategic importance, so you’re better off leaving it to the professionals who, most likely, reside in your organization’s marketing or public relations (PR) department. If your organization has a dedicated strategic communications, media, or public affairs team, it should also be involved in the response process.

As with every other aspect of IR, planning and practice are the keys to success. When it comes to the PR team, this fact may be more applicable than it is with some other teams. These individuals, who are probably only vaguely aware of the intricate technical details of a compromise and incident response, will be the public face of the incident to the broad community. Their main goal is to mitigate any damage to the customers’ and investors’ trust in the organization. To do this, they need to have just the right amount of technical information, must be able to present it in a manner that is approachable to broad audiences, and must present information that can be dissected into effective sound bites (or “tweets”). For this, the PR team will rely heavily on members of the technical team who are able to translate “techno-speak” into something the average person can understand.

Internal Staff

The composition of the technical team that responds to an incident will usually depend on the incident itself. Some responses will involve a single analyst, while others may involve dozens of technical personnel from many different departments. Clearly, there is no one-size-fits-all team; you need to pull in the right people to deal with each problem. The part that should be prescribed ahead of time is the manner in which we assemble the team and, most importantly, who is calling the shots during the various stages of incident response. If you don’t build this into your plan, and then periodically test it, you will likely lose precious hours (or even days) in the “food fight” that will likely ensue during a major incident.

A best practice is to leverage your risk management plan to identify likely threats to your systems. Then, for every threat possibility (or at least the major ones), you can “wargame” a response in a handful of ways. At each major decision point in the process, you should ask, who decides? Whatever your answer, the next question should be, does that person have the required authority? If the person is lacking authority, you have to determine whether someone else should make the decision or whether that authority should be delegated in writing to the decider. These are important determinations: you don’t want to be in the midst of an incident response and have to sit on your hands for a few hours while the decision is vetted up and down the corporate chain.

Contractors and External Parties

No matter how skilled or well-resourced an internal technical team is, you may have to bring in “hired guns” at some point. Very few organizations, for example, are capable of responding to incidents involving nation-state offensive operators. Calling in the cavalry, however, requires a significant degree of prior coordination and communication. Apart from the obvious service contract with the IR firm, you have to plan and test exactly how they would come into your facility, what they would have access to, who would be watching and supporting them, and what (if any) parts of your system are off limits to them. These IR companies are very experienced in doing this sort of thing and can usually provide a step-by-step guide as well as templates for nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) and contracts. What they cannot do for you is train your staff (technical or otherwise) on how to deal with them once they descend upon your networks. This is where rehearsals and tests come in handy—in communicating to every stakeholder in your organization what a contractor response would look like and what each role would be.

It is possible to go too far in embedding IR contractors, however. Some organizations outsource all IR as a perceived cost-saving measure. Their rationale is that they pay only for what they need, because qualified personnel are hard to find, slow to develop in-house, and expensive. The truth of the matter, however, is that this approach is fundamentally flawed in at least two ways: First, incident response is inextricably linked with critical business processes whose nuances are difficult for third parties to grasp. This is why you will always need at least one qualified, hands-on incident responder who is part of the organization and can at least translate technical actions into business impacts. Second, IR can be at least as much about interpersonal communications and trust as it is about technical controls. External parties will have a much more difficult time dealing with the many individuals involved. One way or another, you are better off having some internal IR capability and augmenting it to a lesser or greater degree with external contractors.

Law Enforcement

A number of incidents will require you to involve a law enforcement agency (LEA). Sometimes, the laws that establish these requirements also have very specific timelines, lest you incur civil or even criminal penalties. In other cases, there may not be a requirement to involve an LEA, but it may be a very good idea to do so. If you (or your team) don’t know which incidents fall into the two categories of required and recommended reporting, you may want to put that pretty high on your priority conversations list with your leadership and legal counsel.

When an LEA is involved, they will bring their own perspective on the response process. Whereas you are focused on mitigation and recovery, and management is keen on business continuity, the LEA will be driven by the need to preserve evidence (which should be, but is not always, an element of your IR plan anyway). These three sets of goals can be at odds with each other, particularly if you don’t have a thorough, realistic, and rehearsed plan in place. If your first meeting with representatives from an LEA occurs during an actual incident response, you will likely struggle with it more than you would if you rehearse this part of the plan before an incident occurs.

Senior Leadership

Incident response almost always has some level of direct impact (sometimes catastrophic) on an organization’s business processes. For this reason, the IR team should include key senior leaders from every affected business unit. Their involvement is more than about providing support; it will help shape the response process to minimize disruptions, address regulatory issues, and provide an interface into the affected personnel in their units as well as to higher level leaders within the organization. Effective incident response efforts almost always require the direct and active involvement of management as part of a multidisciplinary response team.

Integrating these business leaders into the team is not a trivial effort. Even if they are as knowledgeable and passionate about cybersecurity as you are (which is exceptionally rare in the wild), their priorities will oftentimes be at odds with yours. Consider a compromise of a server that is responsible for interfacing with your internal accounting systems and your external payment processing gateway. You know that every second you keep that compromised box on the network, you risk further compromises or massive exfiltration of customer data. Still, every second the box is off the network will cause the company significantly in terms of lost sales and revenue. If you approach the appropriate business managers for the first time when you are facing this serious situation, things will not go well for anybody. If, on the other hand, there is a process in place with which they’re all familiar and supportive, the outcome will be better, faster, and less risky.

It’s not always required for senior leaders to get involved in incidents. In fact, they are unlikely to be involved in any but the most serious of incidents, but you still need their buy-in and support to ensure that you get the appropriate resources from other business areas. Keeping leaders informed of situations in which you may need their support is a balancing act—you don’t want to take too much of their time (or bring them into an active role), but they need to have enough awareness of the incident that a short call to them for help will make things happen.

Another way in which members of management are stakeholders for IR is not so much in what they do, but in what they don’t do. Consider an incident that takes priority over some routine upgrades you were supposed to do for one of your business units. If that unit’s leadership is not aware of what IR is in general, or of the importance of the ongoing response in particular, it could create unnecessary distractions at a time when you can least afford them. Effective communications with leadership can build trust and provide you a buffer in times of need.

Factors Contributing to Data Criticality

Although we take measures to protect all kinds of data on our networks, there are some types of data that need special consideration with regard to storage and transmission. Unauthorized disclosure of the following types of data may have serious, adverse effects on the associated business, government, or individual.

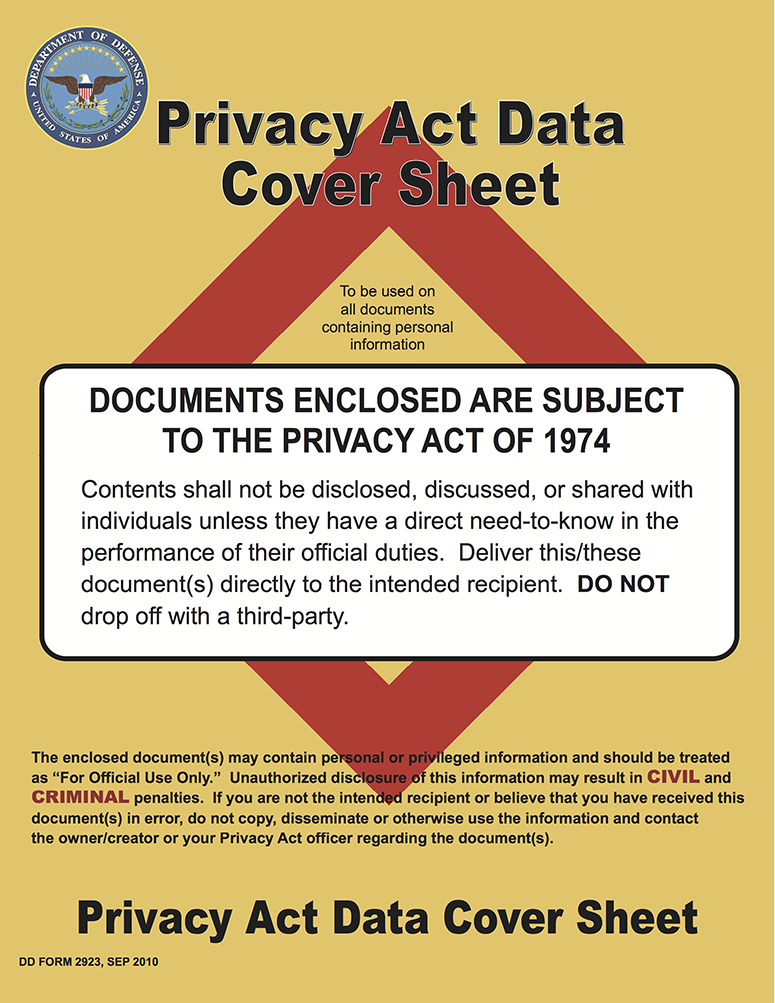

Personally Identifiable Information

Personally identifiable information (PII) is data that can be used to identify an individual. This information can be unique, such as a Social Security number or biometric profile, or it may be used with other data to trace back to an individual, as is the case with name and date of birth. This information is often used by criminals to conduct identity theft, fraud, or any other crime that targets an individual. Depending on the regulatory environment in which your organization operates, you may have to meet additional requirements with respect to the handling of PII, in addition to following federal and state laws. The US Privacy Act of 1974, for example, established strict rules regarding the collection, storage, use, and sharing of PII when it is provided to federal entities. In the US Department of Defense (DoD), documents that contain PII are required to have appropriate markings or a data cover sheet, which is shown in Figure 15-2.

Figure 15-2 Department of Defense Form 2923, Privacy Act Data Cover Sheet

PII is sometimes referred to as sensitive personal information. Often used in a government or military context, this type of data may include biometric data, genetic information, sexual orientation, and membership in professional or union groups. This data requires protection because of the risk of personal harm that could result from its disclosure, alteration, or destruction.

Personal Health Information

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) is a law that establishes standards to protect individuals’ personal health information (PHI). PHI is any data that relates to an individual’s past, present, or future physical or mental health conditions. Usually, this information is handled by a healthcare provider, employer, public health authority, or school. HIPAA requires appropriate safeguards to protect the privacy of PHI, and it regulates what can be shared and with whom with and without patient authorization. HIPAA prescribes specific reporting requirements for violations, with significant penalties for HIPAA violations and the unauthorized disclosure of PHI, including fines and jail sentences for criminally liable parties.

High-Value Assets

High value assets (HVAs) include information or systems that are critical to the function of an organization. Loss of access to this data would have catastrophic impact to the organization’s ability to operate because of the presence of sensitive controls, instructions, or operating data housed in the system. Given its importance, this data is often targeted by adversaries seeking to disrupt an organization via data destruction or ransomware attacks.

Payment Card Information

Consumer privacy and the protection of financial data has been an increasingly visible topic in recent years. Mandates by the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), for example, have introduced a sweeping number of protections for the handling of personal data, which includes financial information. Although similar modern legislation is being developed in the United States, some existing rules apply to US financial services companies and the way they handle this information. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) of 1999, for example, covers all US-regulated financial services corporations. The GLBA applies to banks, securities firms, and most entities handling financial data and requires that these entities take measures to protect their customers’ data from threats to its confidentiality and integrity. The Federal Trade Commission’s Financial Privacy Rule governs the collection of customers’ personal financial information and identifies requirements regarding privacy disclosure on a recurring basis. Penalties for noncompliance include fines for institutions of up to $100,000 for each violation. Individuals found in violation may face fines of up to $10,000 for each violation and imprisonment for up to five years.

In previous chapters, we discussed the importance of having technical controls in place to remain compliant with standards such as the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). PCI DSS was created to reduce credit card fraud and protect cardholder information. As a global standard for protecting stored, processed, or transmitted data, it prescribes general guidelines based on industry best practices, as shown in Figure 15-3.

Figure 15-3 PCI DSS goals and requirements for merchants and other entities involved in payment card processing

PCI DSS does not specifically identify what technologies should be used to achieve the associated goals. Rather, it offers broad requirements that may have multiple options for compliance. Though used globally, PCI DSS is not federally mandated in the United States. Although some US states enact their own laws to prevent unauthorized disclosure and abuse of payment card information, PCI DSS remains the de facto standard for payment card information protection.

Intellectual Property

Intellectual property, the lifeblood of a business, includes the business’s collective knowledge about how to create some unique thing, or the actual unique creations that enable an organization to distinguish itself from its competition. As with tangible property owners, there are laws that govern the rights of an intellectual property owner. As a security professional, you should be aware of the intellectual property that resides on the network so that you can implement appropriate measures to prevent its unauthorized disclosure. Even with the best technical measures in place to protect their intellectual property, companies are still vulnerable to its exposure. Your IR policy must incorporate the latest legal guidance to ensure that employees understand the importance of protecting this information as well as the consequences of unauthorized disclosure for both the company and themselves.

Corporate Confidential Information

Information about the internal operations of a company, or corporate confidential information, may include correspondence about upcoming changes to the company hierarchy, details about a marketing campaign, or any other information that may not be suitable for public consumption. Corporate confidential information is often referred to as proprietary information. You will often see the markings on corporate documents indicating that dissemination of the information should be tightly controlled.

Accounting Data

Financial data about a company requires special handling and protection in a similar way to other sensitive data, even if it may not reveal PHI or PII. In a way, financial data gives insight into the health of an organization and should be treated similarly to PHI. Corporate policies and legal guidance may dictate the general procedures for handling and storing the information, but you should take extra steps to protect accounting data from those within the company who do not have a “need to know.”

Mergers and Acquisitions

Data about upcoming company mergers and acquisitions is another type of sensitive corporate information whose misuse is most often associated with fraud and conspiracy. If information about an upcoming acquisition were to be prematurely disclosed because of a malicious actor, it could have grave consequences on the finances of both companies. Companies about to be acquired may be vulnerable to manipulation or loss of their competitive advantage. If an employee trades a public company’s stock because of privileged knowledge about a company’s finances or a pending acquisition that is not yet public knowledge, he has committed a serious crime called insider trading, which can incur both civil and criminal penalties. The US Securities and Exchange Commission’s Fair Disclosure regulation mandates that if special knowledge about a company is disclosed to one shareholder, it must be disclosed to the public.

Chapter Review

Regardless of the size of your organization, it will eventually be a target of an attacker. The methods used by attackers to conduct their campaigns and the nature of the attacks are constantly evolving. Individual actors, activist groups, and nation-states have far easier access to malicious software than ever before. The question becomes less if you will have an incident and more when. Ignoring this fact will place you and your organization in a precarious position.

Proper IR planning will indicate to your customers, stakeholders, and key leadership that you take security seriously and will instill confidence in the company. Should an incident occur, your preparation will enable you to identify the scope of damage quickly, because you will have identified the data that requires special handling and protection, including PII, PHI, intellectual property, corporate confidential information, and financial information about your organization.

Certain types of security incidents are affected by a variety of regulatory requirements that must be addressed. Between laws that require organizations to notify customers that their information was put at risk and stipulations of the rules of your organization’s regulatory environment, preparation and response isn’t just an effort for your security team. You must assist organizational leadership in communicating the goals of the security policy and the importance of the employees’ roles in supporting it. Aside from the benefit of having a smoother recovery, having a comprehensive incident-handling process regarding special data may protect you, your company, and company leaders from civil or criminal procedures should your organization be brought to court for failing to protect sensitive data. Once you’ve gotten buy-in from organization leadership for your IR plan, you need to continue to refine and improve it as threats evolve. If an unfortunate situation occurs and you need to put the plan into play, you will have the confidence and support to meet the challenge successfully.

Questions

1. Of the following types of data, which is likeliest to require notification of US government entities if it is compromised, lest your organization incur fines or jail sentences?

A. Personally identifiable information (PII)

B. Accounting data

C. Personal health information (PHI)

D. Intellectual property

2. Which of the following is not one of the four categories of protected intellectual property?

A. Patents

B. Trade secrets

C. Items covered by the fair use doctrine

D. Copyrights

3. What makes disclosure of information about mergers and acquisitions so important?

A. Its disclosure may violate Securities and Exchange Commission’s regulations and trigger notification requirements.

B. The information is regulated by the PCI DSS.

C. If the information is disclosed to the public, it could lead to charges of insider trading.

D. The information can give an unfair advantage to the company being acquired.

4. When decisions are made to make changes that will incur significant costs or to involve law enforcement organizations in an incident, which of the following parties will be notified?

A. Senior leaders

B. Contractors

C. Public relations staff

D. Technical staff

5. When would you consult your legal department as a part of an incident response?

A. In the case of a loss of more than 1 terabyte of data

B. Immediately after the discovery of the incident

C. In cases of compromise of sensitive information such as PHI

D. When business processes are at risk because of a failed recovery operation

6. What term refers to members of your organization who have a role in helping with some aspects of some incident responses?

A. Public relations

B. Insiders

C. Shareholders

D. Stakeholders

7. What is the most appropriate course of action regarding communication with organizational leadership in the event of an incident?

A. Provide details only if you’re unable to restore services.

B. Provide details until after law enforcement is notified.

C. Forward the full technical details on the affected server(s).

D. Provide updates on your progress and estimated time of service restoration.

8. What incident response tool should be in place to ensure that the appropriate staff is alerted when it is determined that they may be needed?

A. Indicators of compromise list

B. Call list

C. Triage playbook

D. Developers’ e-mails

Answers

1. C. The protection of personal health information (PHI) is strictly regulated in the United States, and its disclosure could result in civil or criminal penalties. None of the other types of information listed is normally afforded this level of sensitivity.

2. C. Items covered by the fair use doctrine are not one of the four categories of intellectual property, though they are protected by copyright. Intellectual property comprises four categories: patents, copyrights, trademarks, and trade secrets.

3. A. The Securities and Exchange Commission’s Fair Disclosure regulation mandates that if information about a company merger or acquisition is disclosed to one shareholder, it must be disclosed to the public as well; otherwise, the shareholder has an unfair advantage and could be charged with insider trading. This type of information must be carefully controlled.

4. A. Decisions to employ changes that will incur significant costs or to involve external law enforcement agencies will likely require the involvement of organizational senior leadership. Senior leaders will provide guidance with regard to company priorities, will assist in addressing regulatory issues, and will provide the support necessary to move through the IR process.

5. C. Regulatory reporting requirements must be met when dealing with compromises of sensitive data such as protected health information. Because compromises of PHI can lead to civil penalties or even criminal charges, it is important that you consult legal counsel.

6. D. Stakeholders are individuals and teams who are part of your organization and have a role in helping with some aspects of some incident response.

7. D. Organizational leadership should be given enough information to enable them to provide guidance and support. Management needs to be closely involved in critical decision-making points.

8. B. A call list provides escalation guidance and contact information for personnel who should be contacted in the event of an incident.