CHAPTER 20

Security Concepts in Support of Organizational Risk Mitigation

In this chapter you will learn:

• The importance of a business impact analysis

• How to perform risk assessments to select effective controls

• How to evaluate the effectiveness of security staff and controls

• Important sources of supply chain risk

Risk comes from not knowing what you’re doing.

—Warren Buffett

Risk is a constant companion in life. We can take measures to reduce it or transfer it. We might even accept it as inevitable and all but ignore it, but in the end, it is always there. As a cybersecurity analyst, part of your job is to manage risk consciously for your organization. This means that you must understand the business of your organization and determine how it relies on the information systems you are defending before you can assess the risks you face. Armed with an understanding of the risks within the context of your specific organization, you can then select and implement controls to mitigate them. These controls will, of course, have to be assessed periodically to ensure that they remain effective and, just as importantly, your team will have to be periodically tested on their ability to identify and respond to the risks that do manifest themselves in your organization.

Business Impact Analysis

A business impact analysis (BIA) is a functional analysis in which a team collects data through interviews and documentary sources; documents business functions, activities, and transactions; develops a hierarchy of business functions; and finally applies a classification scheme to indicate each individual function’s criticality level. In creating a BIA, you consider the following issues:

• Maximum tolerable downtime and disruption for activities

• Operational disruption and productivity

• Financial considerations

• Regulatory responsibilities

• Reputation

As a cybersecurity analyst, you may not fully understand all business processes, the steps that must take place, or the resources and supplies these processes require. So you need to gather this information from the people who do know—department managers and specific employees throughout the organization. The first step is identifying the people who will be part of the BIA data-gathering sessions. You then have to figure out how you will collect the data from the selected employees, through surveys, interviews, or workshops. Next, you need to collect the information by actually conducting surveys, interviews, and/or workshops. Later on, during analysis, you’ll use data points obtained as part of the information gathering. It is important that you ask about how different tasks—whether processes, transactions, or services, along with any relevant dependencies—are accomplished within the organization. Process flow diagrams are great tools to help visualize this.

Upon completion of the data collection phase, you need to classify the business functions according to their criticality. For instance, your organization may be able to tolerate a few days of downtime in personnel management processes, but if it loses the ability to process customer orders for even a few hours, it could be dead in the water. For each function, you conduct a risk assessment in which you identify the required assets as well as their respective vulnerabilities and threats. After conducting a BIA, you will know what technology assets are critical to the business as well as how long they could be offline without crippling your organization.

Risk Assessment

Through a risk assessment, you can identify vulnerabilities and threats and assess their possible impacts to determine what security controls to implement where. The goal is to ensure that security is cost-effective, relevant, timely, and responsive to threats. It is easy to apply too much security, not enough security, or the wrong security controls and to spend too much money in the process without attaining the necessary objectives. Risk assessments help companies prioritize their risks and show management the amount of resources that should be applied to protecting against risks in a sensible manner.

Before we get started, let’s talk about exactly what risk is. Back in Chapter 8, we discussed that assets are defined as anything of worth to our organizations, including people, partners, equipment, facilities, reputation, and information. Getting back to BIA, we implicitly treat our critical business functions as assets and, for each, we need a risk assessment. The point to remember is that before we can assess risk, we have to ask ourselves, what, exactly, is at risk? Once we have identified what may be at risk, we can look for vulnerabilities in that asset.

We also need to know the source of the threat. Recall that we discussed threat modeling in Chapter 2. Are we concerned with natural events such as hurricanes? Employee errors? Cyber criminals? Collectively, these threats may deliberately or accidentally exploit vulnerabilities in our assets.

A risk assessment has at least four main goals:

• Identify vulnerabilities.

• Determine the probability that a threat will exploit a vulnerability.

• Determine the potential business impact of each threat, should it materialize.

• Provide an economic balance between the impact of the threat and the cost of the countermeasure.

A risk assessment helps integrate the security program objectives with the company’s business objectives and requirements. The more the business and security objectives are in alignment, the more successful both will be. The assessment also helps the company draft a proper budget for a security program and its constituent security components. Once a company knows how much it could lose from the impact of threats exploiting vulnerabilities, it can make intelligent decisions about how much money it should spend protecting against those threats.

A risk assessment program must be supported and directed by senior management if it is to be successful. Management must define the purpose and scope of the effort, appoint a team to carry out the assessment, and allocate the necessary time and funds to conduct it. It is essential for senior management to review the outcome of the risk assessment and to act on its findings. After all, what good is it to go through all the trouble of a risk assessment and not react to its findings? Unfortunately, this does happen all too often.

Risk Identification Process

Let’s circle back to the first three goals of a risk assessment: identifying vulnerabilities, determining the likelihood that a threat agent will exploit them, and determining the business impact of such exploitations. Risk identification is all about figuring out what could happen, how likely it is to actually happen, and how bad that would be for the organization. So how do we come up with the “what could happen” part of that statement? Most organizations leverage one or more of the following sources:

• Cyber threat intelligence If you have a threat intelligence program (or even read the news to see how other organizations are being attacked), then you’ll have no shortage of potential risks to consider.

• Vulnerability assessment This is a staple for most organizations. Run a vulnerability scan, and for each finding, answer this question: What could an adversary do with that?

• Cybersecurity operations There is a lot to be learned in terms of risk from just watching events on your own systems. Failed attacks can provide useful information about adversaries’ capabilities and objectives.

• Brainstorming sessions Put together a small group of people who can think like adversaries and ask them, “How would you attack our organization?” This works best if you keep the session length short (to put pressure on them) and don’t discard any ideas (to keep them from self-censoring).

The risk identification process is an ongoing effort, not a one-time thing. A good approach is to establish a threat working group (TWG) that meets periodically (such as monthly) to discuss new risks that have been identified since the last meeting. This approach enables the organization to have a steady cadence for risk identification that leverages the various information sources at its disposal. This TWG meeting can also help keep the spotlight on severe risks until they are properly mitigated.

A critical tool for tracking risks is the risk register. This is simply a formal list of risks that an organization has identified. Each risk in the register typically includes the following fields:

• Unique identifier

• Short name

• Description

• Owner

• Probability

• Magnitude

• Risk value (or rating)

• Disposition

A bunch of other fields may also be included, but these are the fields we’ve seen most often being used. It is important to assign an owner to each risk, so that someone is held accountable for tracking it and ensuring that it is addressed. Of course, there are many ways of dealing with a particular risk. If its rating is pretty low, you can accept the risk, which means you do nothing (except maybe monitoring and responding) and hope it is never realized. This may sound silly, but keep in mind that you may have identified some pretty small risks along the way. On the other end of the spectrum, a risk’s disposition may require significant investments of staff hours and money. Most risks fall somewhere in between and require some minor configuration changes or patches that someone needs to ensure happen in a timely manner.

Whatever approach you use to identify risks, you should end up with a pretty lengthy risk register. Don’t feel overwhelmed; no organization is able to address every possible risk it faces. The goal is to identify as many risks as you can, and then figure out which ones you care most about. That’s where calculation comes in.

Risk Calculation

There are two approaches to calculating risks: quantitative and qualitative. A quantitative approach is the most rigorous and is used to assign monetary and numeric values to all elements of the risk assessment process. Each element within the analysis (such as threat frequency, impact damage) is quantified and entered into equations to determine total risk. For example, suppose you identify a hundred small organizations that are similar to yours, and on average, eight of them experience ransomware incidents every year. You can determine from industry studies that the average cost per incident is $713,000. So you have an 8 percent chance of suffering a ransomware attack. Using the formula of probability times impact, you could determine that your quantitative risk due to ransomware is $57,040 (0.08 × $713,000) per year.

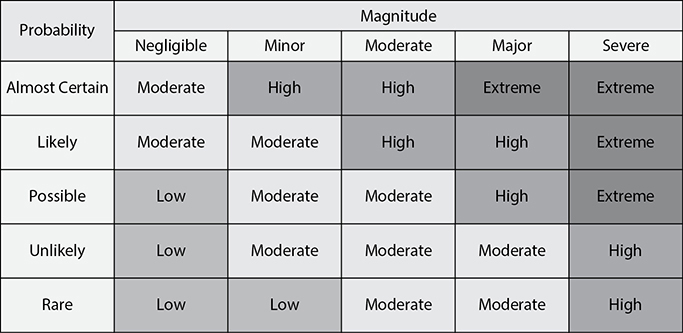

A qualitative risk analysis uses a “softer” approach to the data elements of a risk analysis. It does not quantify that data, which means that it does not assign precise numeric values to the data so that it can be used in equations. Instead, it uses categories that describe the qualities of risk elements. For instance, the probability of the ransomware risk can be categorized as unlikely, but its impact is severe, which could yield a high risk for that incident. Figure 20-1 shows a matrix that is typically used to calculate risk qualitatively.

Figure 20-1 Qualitative risk matrix

It is worth noting that some organizations use a quasi-quantitative approach by assigning values to the probability and magnitude classifications. For example, a Negligible magnitude impact could be assigned a value of 1, a Minor impact is 2, and so on, until reaching a value of 5 for a Severe impact. Likewise, a Rare probability could be given a value of 1, while an Almost Certain one would get a 5. This enables the assignment of numeric values to risks so that a Likely (4) risk with a Moderate (3) magnitude would be valued at 12, while a Possible (3) one with a Severe (5) impact would get a 15. Despite the fact that this approach uses numbers and a bit of arithmetic, it is still qualitative and should not to be confused with a much more thorough quantitative analysis.

Probability

So far, we’ve established that a risk is defined by the likelihood of an incident and the magnitude of its impact on an organization. Let’s turn our attention to the first factor: the probability of a given incident. There are many ways to estimate this, but, again, they follow either a quantitative or a qualitative approach. (And you really shouldn’t mix those two.) You already saw one way of applying a quantitative approach to determining probability in our earlier example about a ransomware attack. In that example, we counted the frequency of such attacks on organizations similar to ours and came up with eight successful attacks per year. This let us know that, on average, organizations like yours have an 8 percent chance of suffering a ransomware incident.

It may be tempting to use this approach, but it is not without some challenges. For starters, you may not have good data on a particular risk. Ransomware is not always reported, which means you would be underestimating its frequency if you rely on public information. It also doesn’t take into account (at least in the way we’ve used it in the example) the fact that some organizations may have better defenses against it. What if all eight organizations that got hit last year were those without good controls in place? Then the 8 percent probability would have no bearing on you, because you would either be way likelier to get hit (if your controls are poor) or way less likely (if you have good defenses). Finally, using last year’s statistics fails to take into account the ever-changing threat landscape. There are ways to deal with all these issues, but they require a level of maturity in risk management that most organizations lack. This is why most of us end up using a qualitative approach.

When dealing with risk probability qualitatively, most organizations rely on expert opinions and, quite honestly, intuition. There are three common approaches to estimating the probability of a risk. The first is simply to have an open discussion (typically in the TWG) and agree on the likelihood. This is probably the fastest way to estimate the probability but is prone to groupthink, which could skew the results. An alternative approach, the Delphi technique, involves sharing anonymous opinions repeatedly until consensus is reached. This avoids groupthink while allowing individuals to be persuaded to change their opinions along the way. It does, however, require more time than the other two approaches. Finally, a common middle ground between open discussion and the Delphi technique is to ask everyone to submit his or her own probability estimate secretly. All the estimates are then averaged out to assign a final probability.

Magnitude

Estimating the magnitude of the impact of a risk using a quantitative approach is a bit easier than doing so to determine the probability of the risk, because the organization already knows a lot of the factors that would be needed. For example, if a core business function is online sales, then a denial-of-service attack of a certain duration against the website would interrupt a predictable volume of sales. The dollar value of those lost (or, at least, delayed) sales is fairly easy to calculate. Things get a bit more complex when dealing with less-tangible assets such as reputation or intellectual property, but, again, there are ways for mature risk management programs to estimate these impacts. Still, most organizations follow a qualitative approach, so let’s focus on that.

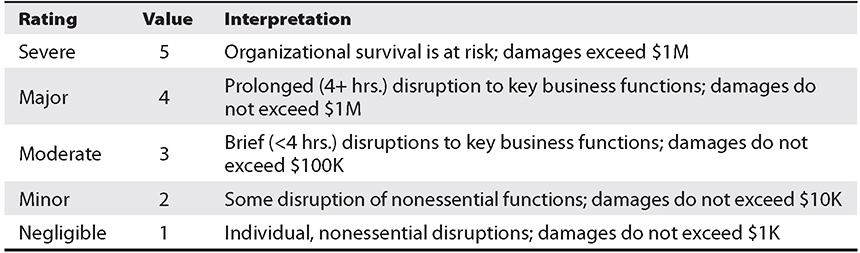

The same three approaches we described earlier for qualitatively estimating probability (open discussion, Delphi technique, and secret voting) can be used for estimating risk magnitude. The trick is to have a shared and fairly precise definition of what each magnitude category means. These definitions are sometimes displayed in an impact interpretation map. Table 20-1 provides an example of one.

Table 20-1 Sample Impact Interpretation Map

The criteria for interpreting the magnitude of a risk’s impact will vary among organizations. These could include impacts on the health and welfare of people, staff hours to remediate, or the number of customers affected. The point is that you should establish the criteria early as part of your risk identification process and then update it periodically as needed.

Putting It All Together

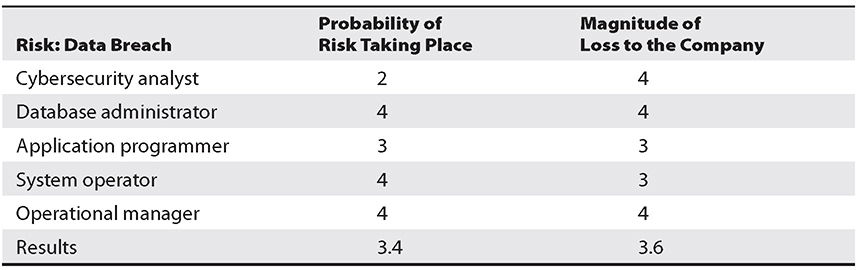

Let’s look at a simple example of a qualitative risk calculation using the secret-voting approach. The risk analysis team presents a scenario explaining the threat of a hacker accessing confidential information held on the five file servers within the company. The risk analysis team then distributes the scenario in a written format to a team of five people (the cybersecurity analyst, database administrator, application programmer, system operator, and operational manager), who are also given a sheet to rank the risk’s probability and magnitude. Table 20-2 shows the results.

Table 20-2 Example of a Qualitative Risk Calculation

Communication of Risk Factors

It is worth repeating that a risk assessment is intended to integrate the security program objectives with the company’s business objectives and requirements. The team involved in this process includes a variety of technical, security, and business stakeholders (among others), so it is important to be able to present the risk factors to a variety of audiences. If you follow the risk identification and risk calculation approaches we just covered, you’ll be most of the way there. The risk matrix will provide a high-level view of risks, how likely they are to occur, and how they may affect the business. If a stakeholder wants to drill down into the probabilities, you should have either meeting minutes (from an open discussion) or the scores and notes provided by individual members of the team (from the Delphi technique or secret voting and tabulation). The other risk factor is the magnitude, the meaning of which is documented in the impact interpretation map. How the factors are combined is dictated by the qualitative risk matrix. Together, these products document and communicate the risk factors in ways that should be understandable to technical and nontechnical staff alike.

Risk Prioritization

It may seem obvious at this point how we’d prioritize the risks we’ve identified. After all, each risk has a risk value that is documented in the risk register. Wouldn’t that be enough to prioritize risks and assign resources to controlling them? Maybe, but we have to keep in mind that risk can be dealt with in four basic ways: transfer it, avoid it, reduce it, or accept it. If a company decides the total risk is too high to gamble with, it can purchase insurance, which would transfer the risk to the insurance company. If a company decides to terminate the activity that is introducing the risk, this is known as risk avoidance. For example, if a company allows employees to use instant messaging (IM), there are many risks surrounding this technology. The company could decide not to allow any IM activity by users because there is not a strong enough business need for its continued use. Discontinuing this service is an example of risk avoidance. Another approach is risk mitigation, where the risk is reduced to a level considered acceptable enough to continue conducting business. The implementation of firewalls, training, and intrusion detection/prevention systems or other control types represent types of risk mitigation efforts. The last approach is to accept the risk, which means the company understands the level of risk it is faced with, as well as the potential cost of damage, and decides to just live with it and not implement the countermeasure. Many companies will accept risk when the cost/benefit ratio indicates that the cost of the countermeasure outweighs the potential loss of value if the risk becomes a reality.

Keep in mind that risk can never be completely eliminated. This means that, even after we implement the best controls, there is still some residual risk left. Risk acceptance, therefore, can happen after each of the other treatment options is employed.

Security Controls

Security controls are put into place to mitigate the risk an organization faces, and they can come in three main flavors: administrative, technical, and physical. Administrative controls are commonly referred to as soft controls, because they are more management oriented. Examples of administrative controls are policies, procedures, personnel security, and training. Technical controls (also called logical controls) are software or hardware components, as in firewalls, IDSs, encryption, and identification and authentication mechanisms. And physical controls are items put into place to protect facility, personnel, and resources. Examples of physical controls are security guards, locks, fencing, and lighting.

Once we have our risks prioritized and separated according to how we want to handle them (transfer, avoid, mitigate, or accept), we finally get to talk about what specific controls we should have (or should put) in place for the risks we want to mitigate. There are three important concepts to consider here: The first is that the cure cannot be worse than the disease. If we think a particular risk could have a magnitude of, say, just under $10,000, but the control to mitigate it will cost us more than that, then it is not a cost-effective control and it makes no sense from business perspective to use it. The other important concept to keep in mind is that the risk will never completely go away, regardless of how effective our controls may be. We can reduce the probability and/or magnitude of a risk, but never to zero. Finally, the third consideration is that, even if the controls are cost-effective and mitigate the risks to the degree that you want them to, over time, they may become less effective as the risk landscape changes. For that reason, it is essential to review the controls’ effectiveness periodically.

Technical Control Review

A technical control review is a deliberate assessment of the effectiveness of technical controls and how they are implemented and managed. You may have decided during your risk evaluation that a firewall may be the best control against a particular risk, but several months later, how do you know it is working as you intended it to? Apart from ensuring that it is still the best choice against a given risk, the review considers issues like these:

• Is the control version up-to-date?

• Is it configured properly to handle the risk?

• Do the right people (and no others) have access to manage the control?

• Are licenses and/or support contracts current?

Even in organizations that practice strict configuration management, it is common to find hardware or software that were forgotten or that still have account access for individuals who are no longer affiliated with the organization. Additionally, the effectiveness of a technical control can be degraded or even annulled if the threat actor changes procedures. These are just some of the reasons why it makes sense to review technical controls periodically.

Administrative Control Review

Like technical controls, our policies can become outdated. Furthermore, it is possible that people are just not following them or that they are attempting to do so in the wrong way. An administrative control review is a deliberate assessment of operational control choices and how they are implemented and managed. The review first validates that the controls are still the best choices against a given risk, and then considers issues like these:

• Is the control consistent with all applicable laws, regulations, policies, and directives?

• Are all affected members of the organization aware of the control?

• Is the control part of newcomer or periodic refresher trainer for the affected personnel?

• Are all affected staff members abiding by the control?

Administrative controls, like technical ones, can become ineffective with time. Taking the time to review their effectiveness and completeness is an important part of any security program.

Engineering Tradeoffs

Security controls have costs that are measured not only in dollars or staff hours. Perhaps one of the trickiest aspects of selecting and implementing technical security controls is that of balancing their impact on the performance of our systems. For example, to protect our endpoints, we may deploy a robust endpoint detection and response (EDR) solution that is constantly scanning memory and disks for patterns of malicious activity. With all its features activated (so as to provide maximum security), the EDR solution may cause noticeable system slowdown for the users, particularly those using older devices. An engineering tradeoff is a deliberate balancing of system security and performance aimed at ensuring that, while neither solution option is optimal, both are acceptable to the organization. We see this also with rule-based IDSs that have very large rule bases. We want to process as many rules as we can get away with, without bogging down the network.

Documented Compensating Controls

As we discussed earlier, sometimes leaders will knowingly choose to take actions that leave vulnerabilities in their information systems. This usually happens either because the fix is too costly (perhaps, for example, a patch would break a critical business process), or because there is no feasible way to fix the vulnerability directly (for example, with an older X-ray machine at a hospital). Compensating security controls are not directly applied to a vulnerable system, but they compensate for the lack of a direct control. For example, if you have a vulnerable system that is no longer supported by its vendor, you may put it in its own VLAN and create ACLs that allow it to communicate with only one other host, which has been hardened against attacks. You may also want to deploy additional sensors to monitor traffic on that VLAN and activity on the hardened host. The process by which these decisions are made and the compensation controls developed should be documented in a separate procedure or included in another, related procedure.

Systems Assessment

We all know the old Russian proverb, “Trust, but verify.” It is not uncommon for organizations to put significant amounts of effort into selecting and implementing controls only to discover (sometimes years later) that their security posture is not what they thought. Every implementation should be followed with verification to ensure that it was done properly. Just as importantly, there should be an ongoing periodic effort to ensure that the safeguards are still being done right and that they are still effective in the face of ever-changing threats.

An assessment is any process that gathers information and makes determinations based on it. This rather general term encompasses audits and a host of other evaluations such as vulnerability scans and penetration tests. More important than your remembering this definition is your understanding the importance of continuous assessments to ensure that the security of your systems remains adequate to mitigate the risks in your environment. Among the more popular assessments are these:

• Vulnerability assessment

• Penetration test

• Red team assessment

• Risk assessment

• Tabletop exercises

Every organization should have a formal assessment program that specifies how, when, where, why, and with whom the different aspects of its security will be evaluated. This is a key component that drives organizations toward continuous improvement and optimization. This program is also an insurance policy against the threat of obsolescence caused by an ever-changing environment.

Supply Chain Risk Assessment

Many organizations fail to consider their supply chain when assessing their risks, despite the fact that it often presents a convenient and easier backdoor to an attacker. So what is a supply chain anyway? A supply chain is a sequence of suppliers involved in delivering some good or service. If your company manufactures laptops, your supply chain will include the vendor that supplies your video cards. It will also include whoever makes the integrated circuits that go on those cards, as well as the supplier of the raw chemicals that are involved in that process. The supply chain also includes suppliers of services, such as the company that maintains the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems needed to keep your assembly line employees comfortable.

The various organizations that make up your supply chain will have a different outlook on security than you do. For one thing, their threats are probably different from yours. Why would a criminal looking to steal credit card information target an HVAC service provider? This is exactly what happened in 2013 when chain discount store Target had more than 40 million credit cards compromised. Target had done a reasonable job at securing its perimeter, but not its internal networks. The attacker, unable (or maybe just unwilling) to penetrate Target’s outer shell head-on, decided to exploit the vulnerable network of one of Target’s HVAC service providers and steal its credentials. Armed with this information, the thieves were able to gain access to the point-of-sale terminals and, from there, to the credit card information.

The basic processes you’ll need to assess risk in your supply chain are the same ones you use in the rest of your risk management program. The differences are mainly in what you look at (that is, the scope of your assessments) and what you can do about it (legally and contractually). One of the first things you’ll need to do is to create a supply chain map for your organization. This is essentially a network diagram of who supplies what to whom down to your ultimate customers. Figure 20-2 depicts a simplified systems integrator company (named Your Company). A hardware components manufacturer supplies its hardware, which, in turn, is supplied by a materials supplier. Your Company receives software from a developer and receives managed security from an external service provider. The hardware and software components are integrated and configured into Your Company’s product, which is then shipped to its distributor and then on to its customers. In this example, Your Company has four suppliers on which to base its supply chain risk assessment. It is also considered a supplier to its distributor.

Figure 20-2 A simplified supply chain

Vendor Due Diligence

Most organizations rely on a multitude of vendors that enable them to perform their core business functions. Companies rely on hardware and software suppliers to provide their IT systems, hosting companies to maintain websites and e-mail servers, service providers for various telecommunication connections, disaster recovery companies for colocation capabilities, cloud computing providers for infrastructure or application services, developers for software creation, and security companies to carry out vulnerability management. It is important to realize that although you can outsource goods and services, you cannot outsource risk.

Due diligence is the exercise of care that a reasonable person is expected to take in a particular situation, and failing to exercise it could leave an organization legally liable for someone else’s losses. So if one of your vendors is not duly diligent and this results in your losses, you may be able to recover damages after the fact. But wouldn’t it be better to ensure that the vendor is duly diligent before a crisis ensues?

This is a key part of performing supply chain risk assessments: to determine your risk that results from what your vendors and suppliers are or are not doing to protect themselves. Let’s look at some things an organization may look at to determine whether its vendors are practicing due diligence and, if not, what the level of risk might be:

• Review references and communicate with former and existing customers.

• Review Better Business Bureau reports.

• Ensure that contracts/agreements include requirements for adequate security controls.

• Ensure that service level agreements are in place if appropriate.

• Review the vendor’s security program before signing an agreement, and periodically thereafter.

• Review internal and external audit reports and third-party reviews.

• Conduct onsite inspection and interviews after signing the agreement.

• Ensure that the vendor has a business continuity plan (BCP) in place.

• Implement a nondisclosure agreement (NDA).

Vendor relationships are prevalent within organizations today, but they are commonly forgotten about when it comes to assessing risks. It is very important to check, before and after getting into a contract or agreement with any vendor, to ensure that they are exercising due diligence when it comes to cybersecurity.

Hardware Source Authenticity

Another frequently overlooked source of risk is acquired hardware, particularly when it could be (or may actually be known to be) counterfeit. In 2012, there were multiple reports in the media of counterfeit networking products finding their way into critical networks in both industry and government. By one account, some of these fakes were even found in sensitive military networks. Source authenticity, or the assurance that a product was sourced from an authentic manufacturer, is important for all of us, but particularly so if we handle sensitive information. Two particular problems with fake products affect a cybersecurity analyst: malicious features and lower quality.

It is not hard to imagine organizations or governments that would want to insert their own fake or modified version of a popular router into a variety of networks. Apart from a source of intelligence or data theft, it could also provide them with remote “kill” switches that could be leveraged for blackmail or in case of hostilities. The problem, of course, is that detecting these hidden features in hardware is often well beyond the means of most organizations. Ensuring that your devices are legitimate and came directly from the vendor can greatly decrease this risk.

Another problem with counterfeit hardware is that, even if there is no malicious design, it is probably not built to the same standard as the genuine hardware. It makes no sense for a counterfeiter to invest the same amount of resources into quality assurance and quality control as the genuine manufacturer. Doing so would increase their footprint (and chance of detection) as well as drive their costs up and profit margins down. For most of us, the greatest risk in using counterfeits is that they will fail at a higher rate and in more unexpected ways than the originals. And when they do fail, you won’t be able to get support from the legitimate manufacturer.

Training and Exercises

General George Patton is famously quoted as having said, “You fight like you train,” but this idea, in various forms, has spread to a multitude of groups beyond the Army. It speaks to the fact that each of us has two mental systems: the first is a fast and reflexive one, and the second is slow and analytical. Periodic, realistic training develops and maintains the “muscle memory” of the first system, ensuring that reflexive actions are good ones. In the thick of a fight, bombarded by environmental information in the form of sights, sounds, smells, and pain, soldiers don’t have the luxury of processing it all and must almost instantly make the right calls. So do we, when we are responding to security incidents on our networks.

Admittedly, the decision times in combat and incident response are orders of magnitude apart, but you cannot afford to learn or rediscover the standard operating procedures when you are faced with a real incident. We have worked with organizations in which seconds can literally mean the loss of millions of dollars. The goal of your programs for training and exercises should then be to ensure that all team members have the muscle memory to handle the predictable issues quickly and, in so doing, create the time to be deliberate and analytical about the others.

The general purpose of a training event is to develop or maintain a specific set of skills, knowledge, or attributes that enable individuals or groups to do their jobs effectively or better. An exercise is an event in which individuals or groups apply relevant skills, knowledge, or attributes in a particular scenario. Although it could seem that training is a prerequisite for exercises (and, indeed, many organizations take this approach), it is also possible for exercises to be training events in their own right.

All training events and exercises should start with a set of goals or outcomes, as well as a way to assess whether or not those were achieved. This makes sense on at least two levels: at an operational level, it tells you whether you were successful in your endeavor or need to do it again (perhaps in a different way), and at a managerial level, it tells decision-makers whether or not the investment of resources is worth the results. Training and exercises tend to be resource-intensive and should be applied with prudence.

Types of Exercises

Though cybersecurity exercises can have a large number of potential goals, they tend to be focused on testing tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) for dealing with incidents and/or assessing the effectiveness of defensive teams in dealing with incidents. Either way, a key to success is to choose scenarios that facilitate the assessment process. The two major types of cybersecurity exercises are tabletop and live-fire.

Tabletop Exercises

Tabletop exercises (TTXs) may or may not happen at a tabletop, but they do not involve a technical control infrastructure. TTXs can happen at the executive level (for example, CEO, CIO, or CFO), at the team level (for example, security operations center or SOC), or anywhere in between. The idea is usually to test out procedures and ensure that they actually do what they’re intended to and that everyone knows their role in responding to an event. TTXs require relatively few resources apart from deliberate planning by qualified individuals and the undisturbed time and attention of the participants.

After determining the goals of the exercise and vetting them with the senior leadership of the organization, the planning team develops a scenario that touches on the important aspects of the response plan. The idea is normally not to cover every contingency but to ensure that the team is able to respond to the likeliest and/or most dangerous scenarios. As they develop the exercise, the planning team will consider branches and sequels at every point in the scenario. A branch is a point at which the participants may choose one of multiple approaches to the response. If the branches are not carefully managed and controlled, the TTX could wander into uncharted and unproductive directions. Conversely, a sequel is a follow-on to a given action in the response. For instance, as part of the response, the strategic communications team may issue statements to the news media. A sequel to that could involve a media outlet challenging the statement, which in turn would require a response by the team. Like branches, sequels must be carefully used in order to keep the exercise on course. Senior leadership support and good scenario development are critical ingredients to attract and engage the right participants. Like any contest, a TTX is only as good as the folks who show up to play.

Live-Fire Exercises

In a live-fire exercise (LFX), the participants are defending real or simulated information systems against real (though friendly) attackers. There are many challenges in organizing one of these events, but the major ones are developing an infrastructure that is representative of the real systems, getting a good red (adversary) team, and getting the right blue (defending) team members in the room for the duration of the exercise. Any one of these, by itself, is a costly proposition. However, you need all three for a successful event.

On the surface, getting a good cyber range does not seem like a major challenge. After all, many or our systems are virtualized to begin with, so cloning several boxes should be easy. The main problem is that you cannot use production boxes for a cyber exercise because you would compromise the confidentiality, integrity, and perhaps availability of real-world information and systems. Manually creating a replica of even one of your subnets takes time and resources, but it is doable given the right level of support. Still, you won’t have any pattern-of-life (POL) traffic on the network. POL is what makes networks realistic. It’s the usual chatter of users visiting myriads of websites, exchanging e-mail messages, and interacting with data stores. Absent POL traffic, every packet on the network can be assumed to come from the red team.

A possible solution would be to have a separate team of individuals who simply provide this by simulating real-world work for the duration of the event. Unless you have a bunch of interns with nothing better to do, this gets cost-prohibitive really fast. A reasonable compromise is to have a limited number of individuals logged into many accounts, thus multiplying the effect. Another approach is to invest in a traffic generator that automatically injects packets. Your mileage will vary, but these solutions are not very realistic and will be revealed as fake by even a cursory examination. A promising area of research is in the creation of autonomous agents that interact with the various nodes on the network and simulate real users. Through the use of artificial intelligence, the state of the art is improving, but we are not there just yet.

Red Team

A red team is a group that acts as adversaries during an exercise. The red team need not be “hands on keyboard” because red-teaming extends to TTXs as well as LFXs. These individuals need to be very skilled at whatever area they are trying to disrupt. If they are part of a TTX and trying to commit fraud, they need to know fraud and anti-fraud activities at least as well as the exercise participants. If the defenders (or blue team members) as a group are more skilled than the red team, the exercise will not be effective or well received.

This requirement for a highly skilled red team is problematic for a number of reasons. First of all, skills and pay tend to go hand-in-hand, which means these individuals will be expensive. Because their skills are so sought after, they may not even be available for the event. Additionally, some organizations may not be willing or able to bring in external personnel to exploit flaws in their systems, even if they have signed a nondisclosure agreement (NDA). These challenges sometimes cause organizations to use their own staff for the red team. If your organization has people whose full-time job is to red team or pen test, then this is probably fine. However, few organizations have such individuals on their staff, which means that using internal assets may be less expensive but will probably reduce the value of the event. In the end, you get what you pay for.

Blue Team

The blue team is the group of participants who are the focus of an exercise. They perform the same tasks during a notional event as they would perform in their real jobs if the scenario was real. Though others will probably also benefit from the exercise, it is the blue team that is tested and/or trained the most. The team’s composition depends on the scope of the event. However, because responding to events and incidents typically requires coordinated actions by multiple groups within an organization, it is important to ensure that each of these groups is represented in the blue team.

The biggest challenge in assembling the blue team is that they will not be available to perform their daily duties for the duration of the exercise as well as for any pre- or post-event activities. For some organizations, the cost of doing this is too high, and they end up sending the people they can afford to be without, rather than those who really should be participating. If this happens, the exercise may be of great training value for these participants, but it may not enable the organization as a whole to assess its level of readiness. Senior or executive leadership involvement and support will be critical to keep this from happening.

White Team

The white team consists of anyone who will plan, document, assess, or moderate the exercise. Although it is tempting to think of the members of the white team as the referees, they do a lot more than that. These individuals come up with the scenario, working in concert with business unit leads and other key advisors. They structure the schedule so that the goals of the exercise are accomplished and every participant is gainfully employed. During the conduct of the event, the white team documents the actions of the participants and interferes as necessary to ensure they don’t stray from the flow of the exercise. They may also delay some participants’ actions to maintain synchronization. Finally, the white team is normally in charge of conducting an after-action review by documenting and sharing their observations (and, potentially, assessments) with key personnel.

Chapter Review

This chapter was all about proactive steps you can take to ensure the security of your corporate environment. The implication of this discussion is that risk is not something you address once and then walk away from. It is something that needs to be revisited periodically and deliberately. You may have done a very through risk assessment and implemented appropriate controls, but six months later many of those may be moot. You wouldn’t know this to be the case unless you periodically (and formally) review your controls for continued effectiveness. It is also wise to conduct periodic systems assessments to ensure that the more analytical exercise of managing risks actually translates to practical results on the real systems. Finally, the human component of your information systems must also be considered. Training is absolutely essential both to maintain skills and to update awareness to current issues of concern. However, simply putting the right information into the heads of your colleagues is not necessarily enough. It is best to test their performance under conditions that are as realistic as possible in either table-top or live-fire exercises. This is where you will best be able to tell whether the people are as prepared as the devices and software to combat the ever-changing threats to your organization.

Questions

1. Which of the following is one of the key reasons why you would perform a business impact analysis?

A. Determine the company’s market penetration.

B. Balance the impact of security controls on the business functions.

C. Identify effective technical controls for the critical business functions.

D. Identify the company’s critical business functions.

2. Which document is typically used to list all known risks to an organization and show their probabilities and magnitudes?

A. Delphi ledger

B. Qualitative risk matrix

C. Impact interpretation map

D. Risk register

3. Which of the following is true about a qualitative risk assessment?

A. It is of higher quality than other types of assessment.

B. It is more rigorous than a quantitative one.

C. It is not as rigorous as a quantitative one.

D. It is not commonly used.

4. In an exercise, which type of team is the focus of the exercise, performing their duties as they would normally in day-to-day operations?

A. Gray team

B. White team

C. Red team

D. Blue team

Use the following scenario to answer Questions 5–8:

Your company does not have a risk management program in place, but your boss is concerned about the risk of a data breach. Nobody has the necessary experience, but she knows that organizational risk mitigation was covered in your CySA+ certification exam, so she asks you to lead a risk assessment and ensure that appropriate security controls are in place.

5. You decide to begin with a business impact analysis (BIA). Which of following would not be part of this analysis?

A. The company’s critical business functions

B. Calculating risks

C. Identifying vulnerabilities

D. Reviewing administrative controls

6. Which approach would you follow in performing a risk assessment?

A. Delphi

B. Quantitative

C. Qualitative

D. Hybrid

7. You determine that the risk of a data breach is severe but also discover that you already have security appliances in place that are supposed to mitigate this risk. What could help you determine whether the risk is truly mitigated?

A. Engineering tradeoff analysis

B. Technical control review

C. Administrative control review

D. Tabletop exercise

8. Satisfied that the security appliances are working as expected, you decide to assess whether your staff, policies, and procedures are also up to the task of handling a data breach incident. Which of the following would be least effective in this effort?

A. Administrative control review

B. Tabletop exercises

C. Live-fire exercises

D. Red team

Answers

1. D. A business impact analysis (BIA) is a functional analysis that develops a hierarchy of business functions and determines each individual function’s criticality level. It should eventually inform the selection of both technical and administrative controls, but that is not part of the BIA.

2. D. A risk register is a formal list of risks that an organization has identified. Qualitative risk matrix is normally a table that assigns a risk category to each possible combination of probabilities and magnitudes.

3. C. A qualitative risk analysis uses a “softer” approach that, unlike the more rigorous quantitative analysis, does not attempt to assign precise values to the variables.

4. D. The blue team is the group of participants who are the focus of an exercise and will be tested the most while performing the same tasks in a notional event as they would perform in their real jobs.

5. D. Security controls are not normally part of a business impact analysis. Instead, you will focus on understanding the critical business functions, their required resources, what vulnerabilities may impact either, and what the overall risk is for each critical function.

6. C. Since the organization is very immature with regard to risk management, it is probably best to follow a qualitative approach, which is not as rigorous as other approaches and doesn’t require extensive expertise or data.

7. B. A technical control review is a deliberate assessment of the effectiveness of technical controls and how they are implemented and managed. This is what you would do to verify your level or risk mitigation with regard to a technical control such as a security appliance.

8. C. While a live-fire exercise could potentially assess the effectiveness of administrative controls, it would require an investment of significant resources. Administrative control reviews and tabletop exercises are both focused on assessing staff, policies, and procedures. Red teams can support either live-fire or tabletop exercises, so if you have one, they would definitely be effective in this effort.