Chapter 6. The Creative Bazaar Model

Sometimes, instead of creating an innovative product from scratch, firms might choose to “shop” for innovative ideas available from the Global Brain. Shopping in the “Creative Bazaar”—the global marketplace of ideas, products, and technologies—is particularly useful when time to market is an important consideration, and when the firm’s external environment is rich with creative potential.

Shopping for innovation is not unlike shopping for food to satisfy your hunger. You basically have two very different options before you. You could go to a grocery store, buy the ingredients, and cook a meal yourself. Alternatively, you could order a fully cooked meal at a restaurant. Cooking a meal yourself would likely cost less, but it would take more time and effort. Moreover, the quality of the meal would be a little uncertain if you aren’t an expert cook. On the other hand, ordering a fully cooked meal from a restaurant would be quick and easy and in most cases would ensure reliable quality. However, your choices will be limited to what’s on the menu, and further, you would have to pay a higher price for the convenience and the reduced risk.

Likewise, when a company shops for innovation, it has similar options. It can source “raw” new product and technology ideas from inventors and then go about “cooking” these ideas into commercial products and services. Alternatively, it can acquire “market-ready” products, technologies, or startup firms. As in the food analogy, these options have very different implications for cost, reach, risk, and time to market.

Regardless of the option the firm chooses to shop for innovation, it needs to partner with a network of inventors and innovation intermediaries. In this chapter, we describe the different options that firms have in shopping for innovation in the Creative Bazaar. As we noted in Chapter 3, “The Four Models of Network-Centric Innovation,” the Creative Bazaar model involves a large firm sourcing innovative product ideas and technologies from external sources and using its proprietary commercialization infrastructure (including its brands, design capabilities, and access to distribution channels) to build on the ideas and make them market-ready.

The “Creative Bazaar” Continuum

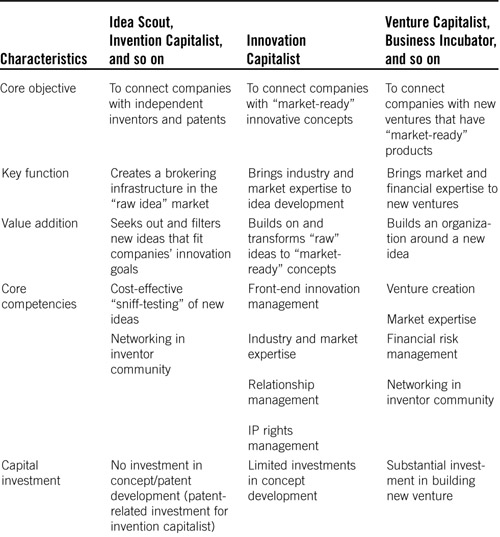

Innovative product or technology ideas can be acquired at different levels of maturity, ranging from “raw” ideas or concepts to “market-ready” products. And companies can use different mechanisms or different types of intermediaries for sourcing such innovation. These mechanisms differ in terms of the cost of acquiring the innovative idea and the risk mitigation that the mechanism allows. In addition, there are additional considerations such as the reach of the mechanism (how many ideas can be sourced) and the time to market (how much time it will take to commercialize the idea). Figure 6.1 depicts the continuum of innovation sourcing mechanisms. These sourcing mechanisms represent the Creative Bazaar continuum.

Figure 6.1. The Creative Bazaar Continuum

Adapted from fig. “The External Sourcing Continuum,” on pg. 111 of “A Buyer’s Guide to the Innovation Bazaar” by Satish Nambisan and Mohanbir Sawhney. Harvard Business Review, June 2007. ©2007 Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved.

Looking at the left end of the continuum, companies can source relatively undeveloped or “raw” product or technology ideas. They can do this by reaching out directly to individual inventors, as Procter & Gamble has done through its Connect+Develop initiative.1 P&G invites individual inventors to submit patented product or technology ideas that can potentially be commercialized by the company.2 Companies such as Kraft, Kimberly Clark, and so on have also announced such initiatives to invite ideas from external entities through their Web site.

Such “raw” ideas or patented inventions can also be sourced through a set of innovation intermediaries that include patent brokers and electronic R&D marketplaces (for example, NineSigma and Yet2.com). These intermediaries largely focus on connecting large firms with individual inventors (or their patents). They are pure brokers, in that they play a matchmaking role, and have limited involvement in the development of the innovative ideas.3 Similarly, another type of intermediary, idea scouts—entities who trawl for innovative ideas in the inventor community on behalf of large firms—utilize domain or market knowledge to locate promising new ideas without much input into the innovation process. While such brokers and middlemen broaden the reach and range of idea sourcing and lower the cost of acquiring ideas, they typically deal with rather immature ideas that are a long way from being ready for primetime. As such, there is still a lot of market risk that the firm has to mitigate through further development and market testing.

Now, consider the other end of the continuum. The mechanisms at this end for buying innovation include internal incubators (such as Salesforce.com AppExchange Central Business Incubator), external incubators (for example, university-based incubators), and venture capitalists—entities that invest in and/or incubate new ventures with the purpose of offering these ventures as acquisition candidates for large firms. Typically, the innovative ideas underlying such new ventures are fully developed, market-demonstrated, and married with matching organizational infrastructure.

The classic example here is P&G’s acquisition of the SpinBrush product (the novel, low-cost battery-operated toothbrush). The SpinBrush was developed and launched in 1999 by a startup (Dr. Johns Products Ltd.) led by entrepreneur John Osher and the principals of Nottingham-Spirk (a Cleveland-based industrial design firm) and their in-house patent lawyer. By the time P&G acquired SpinBrush in 2001, the product had been test-marketed and proclaimed a commercial success based on its initial sales performance in Wal-Mart stores.

The sourcing mechanisms at this end of the continuum enable the development of the product concept to a stage where it can be taken to the market directly, that is, a “market-ready” product. Consequently, the large firm can benefit from lower innovation risk and faster time to market. However, these benefits come at a cost. Acquisition costs are high (for example, P&G had to shell out $475 million for the SpinBrush). And the reach of the firm is limited because few ideas make it far enough in the innovation pipeline to be market-ready. Further, the routes to market, the sales organization, and the other commercialization infrastructure that gets added to the product concept might not be needed by the acquiring firms, and often might need to be discarded at a cost.

The Innovation Capitalist—Filling the Gap in the Middle

Having looked at both ends of the continuum, we find that neither extreme provides an appetizing solution to the trade-offs in shopping for innovation. Idea scouts and other such intermediaries at the left end of the continuum sell “raw ideas” whereas venture capitalists and incubators sell “market-ready products” or “fully baked” companies. Raw ideas are too risky, whereas fully baked companies are too costly. As every shrewd politician likes to say—there has to be a third way—a mechanism that represents the best of both worlds. Indeed, there is such an entity that fills the gap in the middle of the Creative Bazaar continuum and allows firms to achieve a balance among the reach, the innovation cost, the innovation risk, and the time to market.

We call this entity that represents this “third way” an innovation capitalist (IC). An innovation capitalist is an organization that seeks out promising new ideas from individual inventors, transforms those ideas into market-ready concepts, and sells the related intellectual property to large firms. In effect, the IC offers a “market-ready idea” as opposed to a “raw idea” or a “market-ready product.” In so doing, an IC adds significant value beyond the brokering function provided by idea scouts and R&D marketplaces. Specifically, an IC invests in the idea, assumes risk, and shares in the rents generated from selling the intellectual property.

ICs act as the extension of the “fuzzy front-end” (that is the initial, unstructured part) of the innovation process of large firms, by allowing them to make effective tradeoffs between innovation reach and business-readiness in innovation sourcing. Revisiting our cooking analogy, ICs sell “step-saver meals”—ingredients that have been assembled into a recipe that looks promising, and only needs a few more steps to make a delicious meal!

Before we discuss the innovation capitalists (and how companies can partner with them) in more detail, let us first consider the two options that companies have to source “raw ideas” at the left-end of the creative bazaar continuum: (a) partnering with the inventor community and (b) partnering with idea scouts (and other such intermediaries). We omit the right-hand extreme of the continuum because the acquisition of a startup firm is traditional M&A, and is outside the scope of network-centric innovation.

Partnering with the Inventor Community: Dial Corporation and the “Partners in Innovation” Initiative

Partnering with inventors involves going directly to the source—to individuals who have creative ideas. To understand how this approach works, consider how Dial Corporation, a large consumer product company based in Scottsdale, Arizona, has successfully reached out to inventors through its “Partners in Innovation” initiative. Dial has a presence in three core markets: personal care, laundry care, and home care. Some of its well-known brands include Dial, Purex, Right Guard, Pure & Natural, Borax, and Soft Scrub. Its products have been in the American market for more than 130 years. In 1953, Dial launched one of the best-known marketing slogans ever—“Aren’t you glad you use Dial?”—to establish Dial as the nation’s best antibacterial soap.

In March 2004, Dial became a subsidiary of Henkel KGaA, a German consumer products conglomerate based in Düsseldorf, Germany. While the parent company afforded it a greater global reach and presence, in the U.S. market, Dial remained a mid-sized company competing against much larger consumer companies such as P&G and J&J. This size disadvantage necessitated that Dial be very aggressive in innovation to stay competitive. In recent years, this drive for innovation has led to a more open approach to sourcing innovation from external sources, and more specifically to the launch of its partnership with the inventor community called the “Partners in Innovation” initiative.

Dial’s story of its partnership with the external inventors started with the establishment of a separate organizational unit called the Technology Acquisition group in 2003. Debra Park was appointed as the director of the group with the mandate to seek out new product and technology ideas from external sources and to feed the organization’s R&D pipeline with commercially feasible innovative ideas.

The “Partners in Innovation” initiative launched in 2004 was the first step. It originated as a Web site where individual inventors could go and submit patented ideas that Dial would then evaluate for commercialization potential. If ideas were found to be commercially attractive, Dial would pursue those ideas with the individual inventor—in most cases, buying outright the patented idea from the inventor. In 2004, as part of this initiative, Dial launched a contest for individual inventors called the “Quest for the Best.” In this contest, individual inventors were invited to submit patented (or patent pending) ideas to Dial. Dial specified the product categories in which it was seeking innovative ideas.

The number of submissions ran into the hundreds. A panel of judges within Dial then screened those ideas and narrowed the list down to 60 inventions. Dial then asked these inventors to create a five-minute video of their idea so that Dial could get a first-hand feel for the idea. Dial asked inventors to answer two key questions—“How does the idea work? And how is it better than what’s out there?” Based on these video submissions, Dial further narrowed the list down to the top ten inventors. These inventors were then invited to Dial’s corporate campus in Arizona to showcase their inventions to top Dial executives.

Each inventor was assigned a booth to exhibit the prototype of their invention. Judges selected three ideas and the inventors were given awards. Dial agreed to pursue these three top ideas for more formal market evaluation and feasibility analysis. The agreement was that if Dial decided that one of these ideas was commercially attractive, it would buy the patented idea from the inventor.

In 2005, Dial ran another version of the Quest for the Best contest and garnered a fresh set of innovative product ideas for internal evaluation. In the same year, it added another element to the Partners in Innovation program by establishing the “Submit & Win” sweepstakes for online idea submissions. All submissions that met the basic criteria (for example, patented or patent pending idea) were entered into a sweepstake and three winners selected at random were awarded $1,000 each. The objective was to keep inventors coming to the company’s Web site and submitting their innovative ideas. So far, the Partners in Innovation program has generated at least five new product concepts that have made it into the official Dial product development pipeline. This feat is quite impressive for a consumer packaged goods company in relatively mature markets.

Dial’s initiative embodies several best practices worth noting. The first relates to the nature of the innovation network. The members of Dial’s innovation network primarily consist of individual inventors. They are a diverse lot. As Debra Park notes, “Some of them are retirees who have mulled over these things and now they have time to work on it. But for some of them, it’s a side passion. One gave a presentation at the local inventor association here in Arizona. And, these people are from all walks of life.”4

Dial was able to reach out to such a diverse and widely distributed set of inventors by partnering with local and national associations of inventors. It decided early on that establishing credibility with the inventor community was critical. Partnering with inventor associations signals that Dial is a credible and trustworthy partner. Dial sought and got the support of two inventor associations—the United Inventor Association (UIA), a national body, and the Inventor Association of Arizona, the local association. UIA was instrumental in getting the word out in the inventor community about Dial’s “Quest for the Best” contest and other initiatives. According to Debra, “UIA is a much respected organization within the inventor community. So, hearing it from them made inventors feel more comfortable ... in their eyes, Dial is a big corporate entity.”

Dial also provided the commercialization platform for getting the innovative ideas to the market. We call this role the innovation portal—a role that involves serving as the portal to the market for new ideas and concepts. As the dominant player in the network, Dial made the crucial decisions regarding the commercial feasibility of the innovation and the approach it should take to develop and market the new product. And if the idea or the patent was licensed, Dial assumed the responsibility for appropriating the value from the innovation and sharing it with the inventor.

A key to the success of Dial’s initiative was to establish itself as the preferred innovation portal for individual inventors with neat ideas. As Debra Park notes, “To me, one of the mantras of the Partners in Innovation program is—‘think of Dial first.’ Come to us first with your idea, not to our competitors, and set up Dial as a company that you would want to do business with.” To achieve this goal, Dial had to make the process as transparent as possible and also build a long-term, trust-based relationship with the inventor community. For example, it made sure that it communicated the outcomes of the ideas submitted promptly and in a respectful manner to the inventors. Such actions enabled the company to establish and maintain a network of inventors who are likely to bring their ideas to the company in the future.

Although Dial does not use intermediaries, preferring to interact directly with individual inventors, the inventor associations do play a supporting role by facilitating those interactions and promoting Dial’s initiatives in the community. For example, they helped to communicate details of Dial’s contest and other initiatives to the different chapters of the association across the country. Inventor associations have an incentive to play such a facilitating role as they spend a lot of their resources educating their members on how not to get ripped off by fraudulent patent brokers and agents. By partnering with a reputed and established company like Dial, the association is able to offer a safe and trusted avenue for inventors to shop their ideas. In return, Dial also sponsored some of the associations’ educational activities to cement its perception as a “good citizen” of the inventor community.

In partnering with individual inventors, there are no formal linkages among the members in the network, so governance is largely based on trust and reputation. Most individual inventors have limited knowledge about patents or product commercialization. Thus, their trust-based relationship with Dial is crucial in their dealings with the company. On the other hand, Dial has a critical need to maintain its credibility and reputation in the inventor community. Any bad experience that an individual inventor might have with the company would likely travel fast within the inventor community via word of mouth and damage Dial’s long-term objective of becoming the preferred portal of innovative ideas.

Dial also made sure that a clear organizational mandate existed to take the promising external ideas into the formal product development channels within the organization. For example, Dial instituted internal systems whereby innovative ideas could be funded for the proof of principle stage even if initial evaluations did not match with Dial’s current product portfolio. Without such a mandate and associated systems, externally sourced ideas would likely stagnate within the company and not see the light of the day in the marketplace—thereby discouraging inventors from bringing their ideas to Dial in the future.

Furthermore, with the acquisition of Dial by Henkel, the scope of both idea collection as well as idea utilization has become more global. For example, in early 2007, Henkel launched the Henkel Innovation Trophy, a global contest for innovative product ideas. The program was launched in collaboration with U.S. and international inventor associations, including the United Inventor Association in the U.S. and the Deutscher Erfinderverband, the German inventors association. Further, innovative ideas sourced by Dial from the inventor community (in the U.S.) that do not have a direct fit with Dial’s current product strategy are shopped around among Henkel’s other business units worldwide. In the words of Debra, “We are now not only sourcing ideas for Dial but for Henkel, too.” Such a global reach enhances the attractiveness of Dial as the preferred portal for individual inventors.

Dial uses several metrics to evaluate the success of its Partnership in Innovation program. For example, the company tracks the ideas as they progress through the development pipeline—how many ideas were brought in, how many proceeded to concept test, how many were incorporated into a project, and how many actually went into the market. Of course, the ultimate success metric is whether the idea got into the market. As Debra notes, “All of this boils down to that something was put out into the market under the Dial name—that to me is the only meaningful measure of whether I am doing a good job here.”

While Dial is definitely one of the pioneers in employing this form of the Creative Bazaar model, other companies such as P&G, Kimberly Clark, and Kraft Foods have also started similar initiatives. The case of Dial, however, suggests that success in this approach requires patiently building trust-based, long-term relationships with the inventor community and seeking the help of inventor associations and other such entities.

Partnering with Idea Scouts: The Big Idea Group and “Idea Hunts”

Another form of the Creative Bazaar model eschews direct interactions with inventors, relying instead on the services of an intermediary, such as an idea scout to seek out innovative ideas or technologies.

The Big Idea Group (BIG), located in Manchester, New Hampshire, is a firm that focuses on identifying innovative product concepts for large companies, particularly in the areas of consumer packaged goods, food and beverages, and personal media and technology. The company was founded by Mike Collins, a former venture capitalist and toy industry entrepreneur, in 2000. Over the years, the company has built a large network of independent inventors, which it mines for new ideas and concepts.

Reminiscent of the popular public television show, “Antiques Roadshow,” where antique experts offer appraisals for antiques that people bring in from their homes, BIG conducts “roadshows”—events at different locations of the country where inventors can walk in and present their ideas to a panel of experts who provide a quick and free evaluation of the idea. There are no obligations on the part of the company or the inventor for this preliminary idea evaluation. If the initial evaluation shows that the idea might have potential, the company invites the inventor to submit the idea in a more formal manner and sign a representation agreement with BIG, wherein it takes the responsibility for shopping the idea to large client companies who might be interested in commercializing it. If a company is interested in licensing the idea, BIG splits royalties with the inventor (in most cases, the split is 50-50).

BIG achieves several objectives through the roadshows:

• It provides a free service to individual inventors and establishes its reputation in the inventor community as a trustworthy partner.

• Each inventor who participates in a roadshow—whether or not the ideas get pursued further—becomes part of the “inventor network” that BIG maintains. The roadshows help build BIG’s most important resource—its inventor network. As of July 2007, BIG’s inventor network was 12,000 strong—an impressive pool of creative talent for any client company.

• Within its vast inventor network, BIG has identified a more focused set of around 500 “strong” inventors—individuals that BIG has evaluated as “highly creative” and whose talent is particularly relevant for the more focused discovery of innovative ideas that the company pursues for client firms.

Such focused discoveries are called idea hunts. BIG conducts the idea hunts on behalf of large clients firms such as Gillette, Staples, Sunbeam, and Bell Sports, as well as toolmakers such as Skil-Bosch and Dremel. These “idea hunts” are essentially an exercise in mining BIG’s inventor network for promising ideas related to a specific theme or market need that the client firm has expressed. For example, a client firm might specify a broad market need or the need for a particular type of product; BIG then communicates this need to its inventor network, seeking potential product ideas. After the ideas are submitted (usually online), BIG does an initial screening and then forwards them to the sponsoring firm. Such idea hunts might cost the sponsoring firm anywhere from $40,000 and up.5 So far, these initiatives have led to the creation of more than 60 new products for companies like Staples, General Mills, eToys, Sunbeam, and QVC.6

BIG is not the only firm playing the role of such an intermediary. Another idea scout is the Product Development Group (PDG) LLC.7 PDG plays the role of an idea screener—it receives, compiles, and reviews new product ideas on behalf of companies such as Staples. Its objective is to determine the likelihood of a potential match between the product idea and Staples’ needs. PDG does not do any market research on the viability of the ideas. It only screens and aggregates the ideas that it receives before forwarding them to client firms.

A similar role is also played by electronic R&D marketplaces, such as InnoCentive and Yet2.com. Independent inventors list their patented technologies on such sites, which companies can browse through and then evaluate for potential commercialization. A number of other new types of entities have entered this space (see the following sidebar, “Intellectual Ventures: An Invention Capitalist”).

The role of innovation intermediaries such as BIG and PDG is to mediate between the inventor network and the large company seeking the innovation. As BIG founder Collins says, “Corporations don’t want to deal with inventors one-on-one. We saw the need to bridge between all these inventors and clients who wanted innovation,”10 These intermediaries do not invest any money in developing or validating the innovative ideas. Instead, they add value to the process by seeking out and filtering the promising ideas.

To do this, however, they have to first get access to the inventor community. Thus, the key capability for an intermediary such as BIG is the ability to establish and maintain a network of independent inventors from which the company can source innovative ideas. The larger the network, the more successful the innovation sourcing is likely to be. However, because no formal ties exist between any of the entities in this network, social mechanisms of governance—trust and reputation-based systems—form the glue that holds the network together. Information technology—for example, Web-based forums—can be used to communicate, interact, and share knowledge with individual inventors. Finally, formal agreements based on the sale or licensing of patents form the primary mechanism for the appropriation and sharing of value from the innovative idea.

Partnering with Innovation Capitalists

An innovation capitalist (IC) is an organization that seeks out and evaluates innovative technology and product concepts from the inventor community and other external sources, develops and refines these ideas to a stage where their market potential is validated, and then markets these technology and product concepts to large client firms. In other words, an IC firm transforms the ideas to a stage where a large firm can make a much better judgment of their market potential (see the following sidebar, “Profiles of Innovation Capitalist Firms”).

ICs help companies outsource the early stage ideation and development processes, often the most risky and time-consuming stage of the development cycle. Their value proposition centers on four themes—greater reach, lower risk, greater speed, and lower cost. ICs enable large firms to broaden their innovation reach—the range of ideas they can consider—without requiring direct interaction with the inventor community and the associated investment in relationship management or risks related to IP rights and knowledge spill-over. Further, they provide client firms with access to innovative product or technology ideas that are much farther along on the maturity scale (that is, more “market-ready” ideas), thereby mitigating early-stage innovation risks as well as lowering the time to market without significantly increasing the innovation acquisition cost. By selectively investing in and building on promising ideas, ICs allow large firms to lower the overall business risks related to the innovation. Also, ICs lower the cost of acquiring the innovation by not adding any management or other commercialization infrastructure to the innovation, relying instead on the existing brand and operational infrastructure of the client firm for market exploitation. Moreover, ICs source innovation at a fairly early stage, allowing for cheaper acquisitions than buying a fully baked startup firm. In return for this unique value proposition, ICs expect a share of the proceeds from the innovation from the client firm.

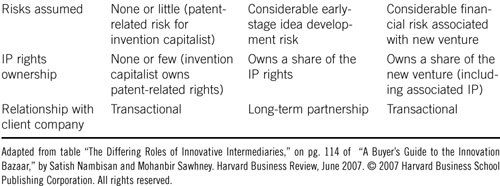

How different is an IC from other innovation sourcing mechanisms we have discussed in this chapter? In Table 6.1, we summarize the key differences between an innovation capitalist and other innovation sourcing mechanisms. As we discussed earlier, an IC differs from an idea scout or patent broker in that it invests in and adds value to the innovation. And although an IC shares some traits with venture capitalist firms, it is different from them in that its capital investment tends to be very limited and the investment focused only on refining the product idea and not on building an organization (or management infrastructure) around that idea. Further, most of the projects (product concepts or technology ideas) that ICs pursue typically do not fit the “business model” of VCs. They don’t have the “size” to justify additional management overheads or the creation of new market channels. Also, the expected payoff tends to fall below the threshold of most VCs—that is, the projects don’t exploit or warrant the core competencies of VCs nor do they provide sufficient returns. As Stephan Mallenbaum, a partner at New York–based Jones Day, notes, an “innovation capitalist can serve as an extension of a large client company’s innovation engine. Such a service provided by (an innovation capitalist) is really unique and VCs are just not equipped to serve large firms in that manner.”11

Table 6.1. Comparison of Innovation Capitalist with Other Innovation Sourcing Mechanisms

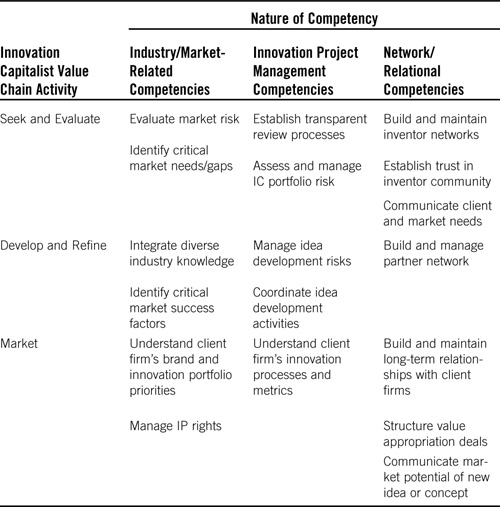

Value Chain and Competencies for Innovation Capitalists

To deliver such a value proposition, an innovation capitalist has to implement a value chain with three components: Seek and Evaluate, Develop and Refine, and Market the new product/technology concept. Figure 6.2 shows the value chain of an innovation capitalist and Table 6.2 lists the key competencies needed. Let us examine these value chain activities and associated competencies in more detail.

Figure 6.2. The value chain of an innovation capitalist

Table 6.2. Competencies for Innovation Capitalist

Seek and Evaluate

The Seek and Evaluate activity relates to sourcing innovative ideas (or patents) from the inventor community and selecting those that have the best potential to develop into a marketable product or technology.

This activity requires two competencies. One is that the IC has to establish and maintain deep roots in different types of inventor communities to allow it to source ideas from a wide range of places. Some of the IC firms are active in attending regional and local inventor club meetings and sponsoring and participating in inventor education events. This direct outreach to inventor clubs builds awareness of the IC firm and establishes a long-term, trust-based relationship with the inventor community. Trust is crucial because historically, intermediaries like patent brokers have earned an unsavory reputation by ripping off inventors who have limited knowledge of the patenting and commercialization processes. Building trust and offering a fair and just idea review process are essential to attract good ideas from inventors. As Brandon Williams, the managing director and co-founder of IgniteIP notes, “The overall approach should be—we win when you win.”

The second competency relates to the ability to screen or identify ideas that are worth further consideration and investment. Typically, the first screening is a qualitative analysis of the key value proposition of the idea and the potential for building sufficient IP—a five-minute “sniff test.” Given the volume of ideas to be screened, it is critical that the IC firm be able to do this as cost effectively as possible. As you saw earlier in the example of the BIG, pre-scheduled events (such as “roadshows”) held in different parts of the country where individual inventors can come and present their ideas to a panel of experts for preliminary screening is one such cost-effective mechanism. Evergreen IP, on the other hand, pursues a more community-centric approach—it sends out its “scouts” to places that inventors frequent and provides idea assessments then and there itself. This technique allows EIP to find out through word of mouth “where the ideas are located” and provide rapid assessments, which might help the inventor to further refine the idea and induce him/her to come back to the company later on. The overall objective is to offer a transparent and fair process by which the business potential of new ideas can be quickly evaluated.

The initial evaluation is often followed by a more rigorous quantitative benchmarking test of the market/business viability of the product or technology concept. EIP, for example, uses an idea handicapping tool such as Merwin, a benchmarking database from Eureka Ranch, the market research firm, for this screening. It evaluates and provides a score for an idea that reflects its potential market success. John Funk, a co-founder of EIP, describes this initial screening:

The average market success score is 100 on that scale. The CPG companies that use Merwin, which there’s a fair number that do, they get excited when they’re at about 120. So we’ve handicapped ourselves to say it’s got to be really north of that. We’re looking for 170. And that’s our first screen for identifying. And then we use a “spiral risk reduction” model. What’s the big show stopper? Is there a protectable asset here? Because if we don’t have a protectable asset, we don’t have anything to transact around, a license agreement. So sometimes we’ll go there first, do the patent search to see if we’ve got enough green space.

Is it a big enough idea? Is the size of prize going to be meaningful enough that our royalty stream is going to be worth a hill of beans? And this is where the research tool comes into play. So we can both clarify the product, enhance the product with design in figuring out how to do it, and iterate that through a research loop that’ll make sure that we’ve got the right purchase intent to make it meaningful and to get somebody’s attention.

When we go into a large client company, we can have a wonderful relationship with them. Everybody knows us and likes us and we can get a meeting. But if we don’t have something that is worth jumping the queue, nothing will happen .... The inertia factor is huge in these large companies. So we’ve got to have something that they say this is worth screwing up, or creating chaos internally for me.12

Develop and Refine

After the ideas are sourced, they need to be developed or transformed to a stage where there is greater clarity about the commercialization potential, and the ideas can be marketed to a large firm. Typically, this activity starts with the IC firm negotiating a deal with the inventor to own part of the idea as a prerequisite for making further investments in it. Thus, at this stage, the idea becomes a project in the IC firm’s portfolio and the firm’s ability to manage this project from here on determines its success rate.

While many of the capabilities to develop and refine the product/technology concept can be acquired from outside, an IC firm needs two in-house competencies: relevant domain knowledge and an exceptional market focus. The transformation process often progresses iteratively by identifying and resolving the key risk areas in the innovative idea. Such risks might relate to market risks (which in turn would require market validation), manufacturing risks (which might require prototyping and addressing manufacturability issues), asset protection risks (which might require evaluating the quality of the patent), and so on. The degree or the extent of idea transformation depends on the nature of the product concept or idea, the nature of the industry or market, and the nature of the client firm for which the idea is targeted.

Consider a project that Evergreen IP pursued recently. An inventor brought an idea for a collapsible plastic trash collector—as a solution for temporary trash situations such as parties, picnics, and in community events. The initial evaluation showed that while the idea was promising, the particular solution that the inventor came up with was not economically feasible. EIP checked with a few potential client firms and realized that the inventor had indeed identified a very unique problem—a $250 million product opportunity—although the proposed solution was not the best way to tap into the opportunity. So EIP invested capital in transforming the solution to make it commercially more feasible. The resulting work produced a product design and prototype that attracted serious attention from several large manufacturers in that product market. In this case, the transformation was comprehensive—it involved the development of a new solution.

More interestingly, the preceding example also shows that individual inventors might not always have great product inventions from the outset. However, they can often be excellent “sensing mechanisms” for product opportunities. As such, the IC needs to remain flexible and adapt its strategy to build on and transform the inventor’s innovative contribution, whatever be the starting point—a great working product prototype or an important market need.

Market

This part of the value chain relates to placing the product or technology concept (or related IP) within a client firm—in other words, appropriating the value from the innovation through licensing agreements or sale of the patent or other such mechanisms. It calls for seeking out the firm that is most likely to be interested in the innovative idea and marketing and negotiating the IP sale or placement.

This activity requires two competencies. For one, the IC has to have excellent relational skills—they have to establish and maintain long-term relationships with large client firms. An IC firm’s understanding of a client firm’s competitive context enables it to conduct better analysis of the potential fit of an innovative idea vis-à-vis the firm’s commercialization infrastructure. As Dave Bayless of Evergreen IP notes, “It is all about the client’s brand window—gaps in the brand portfolio—and their internal hurdle rate. And, we spend considerable effort in getting to know our potential clients ... what are their priorities now, what are they looking out for, and what kind of market size will they accept?” Such an understanding can also enable IC firms to customize their back-end processes to integrate well with the client firm’s open innovation processes. The IC firm also needs to develop a trust-based relationship that can help the negotiation process.

Another competency relates to the management of intellectual property rights related to the product concept. ICs have to possess knowledge and capabilities to navigate the IP placement process and to ensure that equitable share of the IP are appropriated. For example, IgniteIP recently assessed a new technology for removing heavy metals from water, which could reduce hazardous waste in the mining industry. The inventors had tried unsuccessfully to create a new business around the technology. When IgniteIP took over the project, it evaluated the market and decided that the greatest challenge lay in overcoming the mining industry’s inertia around adopting a new technology like this. So, in addition to modifying the technology to clarify its potential, Ignite constructed an innovative licensing scheme that provided sufficient incentives for a client company to acquire the new technology and also ensured that Ignite and the inventors would receive sufficient return on their investment.

IC firms need to have appropriate skills to negotiate effectively in asymmetrical power situations (that is, with large client firms) to appropriate a fair share of the returns from the innovation. Given that only around 2% of the ideas that an IC firm reviews makes it to the commercialization stage, it is critical that the firm has excellent capabilities to appropriate value from those ideas that do finally get placed within a large firm.

Unlike early-stage innomediaries, IC firms do not operate on service-based fees. Instead, they share the returns from the innovation with the inventor. While this might be structured in different ways, the typical method is to pre-specify the proportion of the licensing royalties (or proceeds from the sale of the IP) that the IC firm will retain. IC firms retain anywhere from 40% to 70% of the revenue stream.

The scale of capital investments that IC firms make in their projects vary widely based on the size of the potential market for the product or the technology, but they range anywhere from $50,000 to $500,000. According to Brandon Williams of IgniteIP, “(our) objective is not to add value through capital investments as venture capitalists tend to do. Instead, we add value through a unique combination of our domain/market, networking, and innovation management skills.” It is also important for IC firms to shape this value addition so as to complement the innovation strategies and initiatives of large firms. Thus, the IC firm’s ability to meld together its varied competencies in a way that complements the internal innovation infrastructure of the large firm is the most important factor in determining its long-term success as an innovation partner of the client firms.

Having examined the IC’s value proposition and competencies in some detail, we now look at the IC from the perspective of the large client firm by considering the approaches that large firms such as P&G, J&J, and Unilever can adopt to partner with IC firms.

Building Winning Partnerships with Innovation Capitalists

An IC can serve as a very effective partner to strengthen the innovation pipeline of a large firm. However, for these partnerships to succeed, the client firm has to play an effective role on its part as a partner.

The first important task the large firm has to undertake is to build and nurture a special relationship with a few selected IC firms (and their associated inventor communities). Another task is to direct or drive the innovation in the network—either by seeking out ideas for specific product markets or by driving the innovative idea using the firm’s internal commercialization engine. Let us look at some strategies related to these two tasks.

Client firms need to acknowledge that there are no standing formal ties between any of the members in the innovation network—either between the IC firm and individual inventors or between the IC firm and the client firm. The importance of trust and understanding in the relationship between a large client firm and an IC thus cannot be overstated. One way to achieve this goal is to establish long-term relationships with a selected set of IC firms. This step ensures a smoother negotiation process for product or technology commercialization deals as both partners are aware of each other’s decision criteria and processes. Further, a large firm can also build into its relationship an informal agreement that it will give all the proposals brought forward by an IC firm serious consideration, in return for giving the company the first chance to evaluate new ideas—in other words, become the “preferred innovation portal” for the IC firm and its associated inventor community.

Another way to enhance trust in the relationship is for a large firm to share information more openly with ICs. For example, the firm can provide ICs with a window into its product gaps, innovation priorities, and business goals. A shared understanding of the innovation priorities enables the IC firm to match promising ideas and concepts from their inventor networks with the requirements of the large company. It also allows ICs to make better judgments on whether or not a potential idea would meet the internal threshold of the large firm (in terms of market size, profit margins, and so on). The eventual goal of information sharing is to develop a shared world view of the large firm’s innovation environment.

It is also important for the large firm to educate its internal units (particularly the R&D unit) on the unique role and value proposition of the IC firm. Such internal evangelism (or building the organization’s faith in the value of the innovation capitalist) helps to overcome the “Not Invented Here” syndrome that tends to bias internal R&D units against externally sourced ideas. And it promotes better alignment of the firm’s internal innovation decision processes with the role played by the innovation capitalist. By integrating the front-end work done by the IC with the back-end development done by the large firm internally, time to market can be further reduced and success rates can be enhanced. For example, one of the ICs we studied used product concept evaluation systems and tools (for example, the Product Lifecycle Management tool) that were already being used by their “preferred” client firm. This allowed faster project transitions from the IC firm to the client firm.

Large firms can also strengthen their partnership with IC firms by adopting a “reverse flow” model—that is, becoming the source of innovative ideas for the IC firm. Often, large companies have product or technology concepts that they have developed to different stages (including working prototypes), but for varied strategic or market reasons are not considered high priority and hence sit on the shelf.

John Funk of EIP notes, “Often, when we have gone to our client companies, they tell us that they have something which they would like us to take a look at. These are ideas that they (client firm) have let their people incubate that might not fit with their brands at the time or they have sold off the brand that they originally incubated it under. Sometimes as (these ideas) get farther along they don’t fit—strategic reasons, brand fit, resource, size of prize, hurdle rates, whatever it might be. They put them on the shelf. And there’s nowhere for those to go today. We come on it and we say we’ll take those on. We will develop them further and market to other firms.” In other words, the large client firm now becomes the “inventor.”

For example, P&G’s External Business Development (EBD) group recently initiated such a project with one of the IC firms. P&G had developed a product concept but found that the target market was only around $35 to $50 million worth (well below P&G’s internal threshold and also the concept didn’t have a natural fit with any of its existing brand portfolio). Because the concept required further work, it negotiated a deal with an IC firm to develop the concept further and market it to other large firms in that product market.

As Tom Cripe, associate director of the EBD group of P&G notes, “We are definitely interested in such deals as they allow us to potentially derive revenue from ideas that are sitting on our shelves but require more concept work before they are business-ready. Such deals also allow us to strengthen our relationship with specific IC firms. ... And, in turn, we want those IC firms to consider P&G as the preferred destination when they come across interesting ideas in the (inventor) community.” So this approach for monetizing stranded assets (whether those are patents or just product concepts) has two payoffs—potential new product revenues, and a stronger relationship with the IC firm to become the “preferred innovation portal.”

Are there any downsides to partnering with an innovation capitalist? Well, there are definitely some risks that client firms need to keep in mind. Precisely because they are new on the scene, innovation capitalists are still refining their business models and thus must work out some wrinkles. For example, they get much more modest returns than do, say, venture capitalists. That means they need enough ongoing projects in their portfolios to sustain the business. But an overlarge portfolio will reduce the value an IC firm can add in developing any given idea and also threaten its relationships with both client companies and the inventor community. Another risk for the client firm is relational risk. On the one hand, to benefit from the IC firm’s capabilities, a client firm has to open up and share its innovation priorities; on the other hand, building the trust needed for such sharing of information will take some time. Thus, this poses some risk for the client firm especially if the IC firm is still very young and not well established.

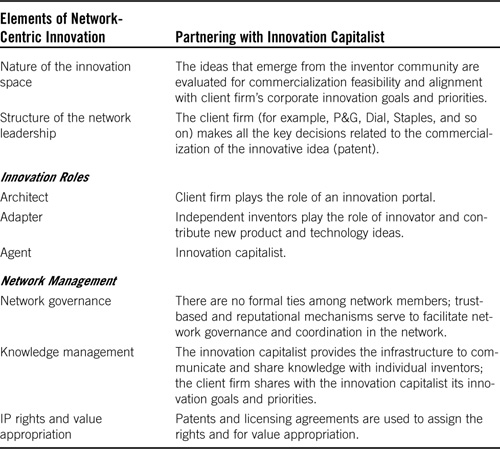

Table 6.3 shows some of the key elements of this form of the Creative Bazaar model that involves partnering with ICs. The key observation that bears repetition—success in partnering with ICs—depends on the closeness of the partnership the client firm can build with ICs.

Table 6.3. The Creative Bazaar Model & The Innovation Capitalist

In the words of David Duncan, the head of R&D for Unilever’s home and personal care division, at best such relationships offer more than a pipeline of new projects and become “a collaborative effort at building the innovation capability” of a client company.13

Conclusion

The Creative Bazaar model involves a large firm “shopping” for innovative ideas by establishing a network of partners that might range from individual inventors and inventor communities to different types of innovation intermediaries. You explored three partnering models on the Creative Bazaar continuum that represent different points on the continuum of risk and cost and considered the important role played by an emerging class of entities called innovation capitalists.

Although the innovation capitalist is a powerful approach to sourcing innovative ideas, it is just one weapon in the arsenal of a large firm. Most large firms need to pursue not just one but a combination of the different options we have discussed so far. In other words, they need to implement a portfolio of innovation sourcing mechanisms. The question then is, how should a large firm go about selecting the appropriate set of sourcing mechanisms and making sure that its overall portfolio of innovation sourcing is balanced? What does the optimal portfolio look like? These are important questions, and while we can state the obvious by saying that the answers would be dictated by industry and market factors, we will address these issues in more detail in Chapter 9, “Deciding Where and How to Play,” when we discuss how a firm can identify opportunities in network-centric innovation.