CHAPTER 3

![]()

Surviving Success in the Midi: Growers, Merchants, and the State

A SERIES OF LARGE DEMONSTRATIONS took place in the Midi during the summer of 1907 protesting against low prices and the sale of artificial wines. At the same time, many of Bordeaux’s leading quality wine producers were forced to look to their merchants for financial help, while growers of cheaper wines lobbied local and national governments to establish a regional Bordeaux appellation or brand. A few years later, in 1911, troops were needed to stop the destruction of large quantities of wines that had been brought from outside the Champagne region to Reims and Épernay for making into “champagne.” Phylloxera and the market instability that followed in its wake were the economic origins of these very different events. Vine diseases, technological change, and market integration altered the distribution of power in the commodity chain, weakening the position of most growers while strengthening that of the merchants. This challenge was met by growers who, benefiting from changes in political organization that led to an increase in their political voice, obtained government support to create new institutions to protect their market interests and guarantee that the region would retain a reputation for militancy to this day.

Very different commodity chains were required to produce and sell French wines that were as diverse as vintage champagne, fine old claret, and cheap commodity wines. Chapter 2 showed that falling transport costs, urbanization, and rising real wages led to a significant increase in the domestic consumption of cheap wines and contributed, along with new wine-making technologies, to regional specialization. Merchants played a crucial role in organizing markets by blending wines from different areas to create a standardized product, and the major shortages caused by phylloxera after 1875 forced them to search for new sources of supply, often in foreign countries or through the production of artificial wines. As the recovery in domestic wine production was not accompanied by a significant reduction in these alternative supplies, prices and growers’ profitability fell sharply, leading to demands that government intervene.

This chapter looks at the experience of the Midi, France’s cheapest wine producer. After examining long-run changes in France’s domestic wine supply, and in particular merchants’ attempts to augment supply during the phylloxera epidemic by adulteration, it shows how the changes in political strength of small farmers and workers increased during the Third Republic, especially after the 1884 law permitting the formation of syndicates. Despite the presence of large vineyards in the Midi, the wine industry was relatively united in its attempt first to tackle phylloxera and replant, and then to demand state intervention to control fraud. Finally, the chapter considers how smaller growers started to establish cooperatives in response to another threat to their livelihood, namely, the increasing economies of scale and skills required for wine production and marketing.

PHYLLOXERA AND WINE ADULTERATION

The major wine shortages and high prices in France caused by phylloxera not only led to a rapid increase in production in countries such as Spain and Algeria but also encouraged both growers and merchants to look for domestic substitutes, which the authorities often tolerated because of the exceptional circumstances. One product that became popular from around 1879–80 was the manufacture of wine from raisins and currants, and in 1890 it was estimated that 300 liters of wine with an alcoholic strength of 8 percent could be produced from 100 kilos of raisins or currants, at the cost of just 0.15 franc a liter, considerably less than the price of real wine.1 The first factories were established in the Midi, especially Hérault, but the fact that raisins were cheaper to transport than wine encouraged their location in, or near, major markets, and in 1890 there were reportedly twenty factories in Paris.2

The use of sugar in wine production also became very popular. Chaptal had shown that the addition of sugar to crushed grapes in years with poor summers, especially in northern Europe, improved quality. Output increased indirectly as viticulture was encouraged in otherwise marginal regions and the increase in the wine’s alcohol content saved it from deteriorating. Sugar was also traditionally added with water to the remains of the grapes after their first pressing and repressed to produce second wines or piquettes. Coloring was sometimes added, with fuchsine being especially popular.3 This practice was normally limited to wines for family consumption, “in theory by law and in fact by the abundance of good cheap wine and the relatively high price of sugar.”4 However, the wine shortages and desperate economic situation facing many growers led to the government’s relaxing of the laws, and large quantities of piquettes were sold. By 1890 raisin and sugar wines together accounted officially for a sixth of total French consumption, although the real figure may have been considerably higher.

Most wines kept badly prior to phylloxera, and any surplus wine at the end of the year was distilled. Growers might suffer from low prices after an exceptional large harvest, but there were few incentives for them or merchants to carry stocks from one year to the next. The improved wine-making technologies in areas such as Algeria or the Midi allowed wines to be kept longer, but chemicals were also used to preserve poor-quality ones. These changes, together with the high wine prices caused by phylloxera, led to a sharp decline in wine distilling, with production falling from an annual average of 8 million hectoliters in 1865–69 to 1 million in 1895–99.5 At the same time technical developments in commercial distilling and the appearance of cheaper raw materials (grains, beets, and potatoes) produced a significant fall in the price of industrial alcohol. When French domestic wine supplies recovered and overproduction threatened in the late 1890s, the market to distill surplus wines had practically disappeared. Some of the industrial alcohol was used to manufacture artificial wines, but some also went to create new alcoholic beverages to be drunk in the assommoir or dram shops that competed directly with wine. The exact size of this competition is impossible to establish, but it was believed to have been extensive. For example, official wine consumption in Paris in 1903 was 185 liters per capita, half the 354 liters found in its suburbs. To reduce the incidence of taxation, wines were strengthened with alcohol to the legal maximum before being brought into the city and then watered down and adulterated with industrial alcohol once inside.6 One report to the Chamber of Deputies in 1905 suggested that 20 million hectoliters of manufactured wine were circulating, while another gave a figure of between 10 and 12 million. In the same year the municipal laboratory in Paris randomly tested 617 wine samples and found that 500 had been doctored or adulterated.7

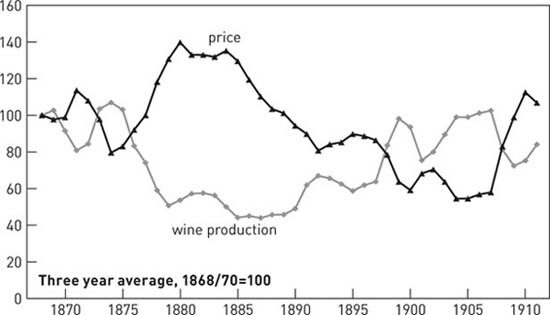

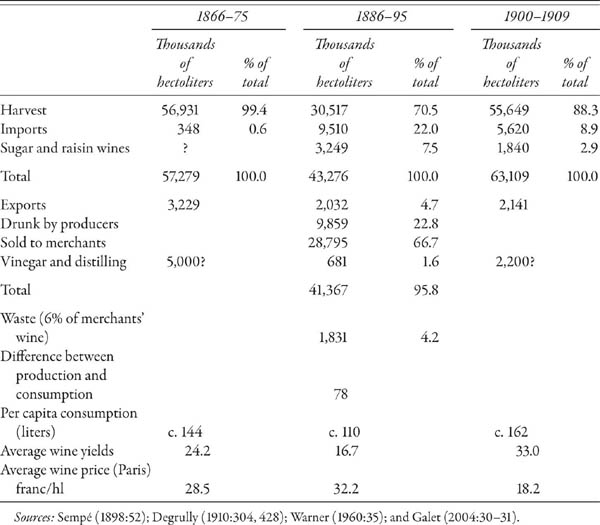

Finally, growers responded to higher prices by increasing the output of genuine wines. The area of vines in France peaked in 1874 at almost 2.5 million hectares and by 1914 had declined by almost a million hectares, or 40 percent. However, the new vineyards were more productive, and yields increased from 22 hectoliters per hectare in the 1870s to 33 in the 1900s. The 1893 harvest was the first in fourteen years to be above the long-term average of 1871–1913 (fig. 3.1). Faced with steeply falling prices, producers looked to the state for help to eliminate substitutes (imported and adulterated wines) and increase consumption of genuine ones (by reducing taxes and transport costs), rather than face the prospect of uprooting their vines and exiting the industry (table 3.1).

The tariff war of the late 1880s provided an excuse to raise duties on Italian wines, and from 1892 those from Spain were also increased, although the impact of this measure was initially limited by the use of free ports and the depreciation of the peseta.8 Spanish exports to France in the 1890s were still 81 percent of what they had been in the 1880s but then fell sharply to 14 percent in 1900s. However, the decline from these markets was offset by the growth of Algerian imports, so that total French imports in the 1900s were still 5.6 million hectoliters, equivalent to 60 percent of the figure in the 1880s. In addition, with the recovery in domestic production, merchants found that many of their old export markets were now protected by tariffs, restricting demand for French wines, despite their lower prices.9

Figure 3.1. French wine production, consumption, and prices, 1851–1912. Source: France. Annuaire statistique année 1938 (1939:62–63)

The production of raisin wines was a second area that legislators looked to control. The Griffe law of 1889 defined wine as being only made from fresh grapes but did not prohibit the manufacture or sale of raisin wines, so long as the consumer was aware of the drink’s true content.10 The Brousse Law of 1891 required that when substances such as raisin wine or gypsum were added to wines, this was marked on the casks and bottles. However, the real cause of the decline in raisin wine production was the succession of tax measures on imports, their manufacture, and the alcohol required to strengthen them. By 1897 Henri Sempé estimated that taxes alone worked out at 25 francs per hectoliter, equivalent to the farm gate price for wines, so the trade virtually disappeared.11 Finally, in 1894 the watering down of wines was made illegal, regardless of whether the consumer was aware of the situation.12

TABLE 3.1

French Wine Supplies and Consumption, 1866–1909

The reduction of imports and piecemeal legislation on imitation wines did not resolve the problem of low prices. As on previous occasions when overproduction threatened, the long productive life of the vine, the low opportunity cost of much of the land on which it was cultivated, and the specialized skills that were required in its production made growers reluctant to uproot healthy vines. Markets had changed, however, as stocks could now be carried over from one harvest to the next with greater ease, restricting the ability of prices to recover after poor harvests. The postphylloxera vines had also required many growers to go deep into debt, so it was no longer sufficient to cover just their variable costs, as after a poor harvest the banks required interest and capital to be repaid, a problem that became especially acute on the Midi’s and Algeria’s large estates. Finally, the economic viability of small producers was threatened not just by competition from low-cost industrial wineries, but also from the market power of merchants who could source their wines from an increasingly greater geographical area.

POLITICS, PHYLLOXERA, AND THE VINEYARD DURING FRANCE’S THIRD REPUBLIC

The response of Europe’s producers to problems such as adulteration, overproduction, and loss of competitiveness after 1900 varied significantly. Both political institutions and the ability of growers, winemakers, and merchants to organize collectively and establish new economic institutions differed across countries and over time. Continental Europe remained essentially rural long after the bases of an industrial society had been established. In France however, growers were able to influence government policy from a much earlier date than their counterparts elsewhere. As Tony Judt has written of this country, “the political organisations and doctrines which responded to the growth of an industrial and capitalist economy had a large and increasingly discontented rural population to whom they could also appeal (indeed, in conditions of a precociously established universal male suffrage, to whom they had to appeal).”13 Although European peasants were attracted to a wide variety of different causes and supported parties across the spectrum, vine growers were more inclined to lean toward radical and socialist politics. A second factor was the extent and nature of vertical integration between grape growers and winemakers, and between winemakers and merchants, which could shape incentives to cooperate on some occasions or pursue strictly sectoral interests on others. The potential for conflict existed at a number of different levels: between small and large growers within a particular region, between growers within different regions, and between growers and merchants.

In 1907 the French economist Charles Gide wrote that “of all the industries in France, whether agricultural or manufacturing, the culture of the vine stands foremost.”14 Yet despite this claim, the exact numbers employed in the sector are difficult to establish. In 1868 Jules Guyot argued that the vine employed 1.5 million vigneron families, or six million inhabitants, and when auxiliary workers were included the figure reached two million.15 By the end of the century the figure was almost identical, at a time when the active male population was still only thirteen million.16 Even though many laborers and other professionals often owned only a very small plot of vines, it seems likely that these figures are inflated because some growers were also counted several times. Gide himself notes that the “number of vinegrowers is very great, is certainly over half a million for the whole of France,” and gives a similar figure for the number of men who were employed full-time in the vineyards, which increased to two million during the harvest.17 In addition, there were over 450,000 retail outlets (débitants) and 28,000 wholesalers.18 Whatever the exact figures, the sector was a major source of employment, and of potential voters for politicians.

The rural nature of society was reflected in its political organization, and the electoral laws in France’s Third Republic (1871–1940) implied that “at least half of the electoral districts for the Chamber of Deputies were predominantly rural, and many others contained a sizeable minority of peasant voters,” while the Senate came to be known as la grande assemblée des ruraux.19 Although the first mass-based political party was not established until 1901, politicians now had to take into consideration the interests of the small farmer, and to get elected they had to indulge, rather than penalize, the peasant producers. As Jules Ferry famously declared in 1884, “the republic will be a peasants’ republic or it will cease to exist.”20 Even phylloxera was politicized, as Bonapartist and royalists whipped up antirepublican sentiment against republican governments that passed legislation giving officials the right to enter vineyards and uproot vines on the suspicion of infection. The bishop of Montpellier in 1876 “sanctioned devotional processions among the vineyards, not just to ward off the phylloxera but also against the ‘republican menace.”21

A decisive change for small producers and workers came with the 1884 Waldeck-Rousseau law on association in France, which removed the need for governmental consent for any association of more than twenty people. Originally designed to encourage moderate workers to join trade unions so that they would cease to be a vehicle for extremists, it had its biggest impact in the countryside among farmers and laborers. Agrarian syndicates were important because they allowed farmers to establish their own list of priorities rather than the large landowners or the church. Both the conservative and antirepublican Société des agriculteurs de la France (the umbrella organization of the syndicates was the Union centrale des syndicats agricole) and the republican Société nationale d’encouragement à l’agriculture looked to extend their political influence in the countryside, and by 1910 there were 5,146 agrarian syndicates with 777,066 members throughout France.22 In 1881 Gambetta created a new ministry devoted solely to agricultural affairs in France and expanded the system of agricultural institutions and administration.23 According to Sheingate, because French political parties were still weak, “farm organizations enjoyed a competitive advantage vis-àvis parties and became important players in national politics.”24 Winegrowers were especially quick to take advantage of the new legislation in their fight against phylloxera, a problem that growers could not solve individually. Syndicates collected and circulated information among members on the best way to deal with the disease and provided information and instructions on the use of new root-stock and grafting. A second area was the purchase of the vines, chemicals, and fertilizers, which benefited growers not just because bulk purchases were cheaper, but because the syndicate was able to control quality, especially important as fraud was a major problem in all countries until the 1920s. In France syndicates were also instrumental in checking another form of fraud, namely, the production and sale of artificial wines, which southern wine producers believed was the prime reason for the collapse in wine prices after 1900.

Conflicts within the wine community were present during the phylloxera epidemic and can often be explained by the timing of the disease’s arrival in a locality. In particular, areas that were still free lobbied hard for a total ban on the entry of new vines (especially American rootstock) in their department, while those areas already infected wanted imports and government-funded nurseries to allow them to replant as quickly as possible. Once replanting was under way, the levels of cooperation between large and small grower, and wine-maker and grower also varied, being relatively strong in the Midi but weak in Bordeaux. In the Midi, the fight against phylloxera provided a useful rehearsal for interest groups for when they faced low wine prices and fraud from the turn of the twentieth century.

THE MIDI: FROM SHORTAGE TO OVERPRODUCTION

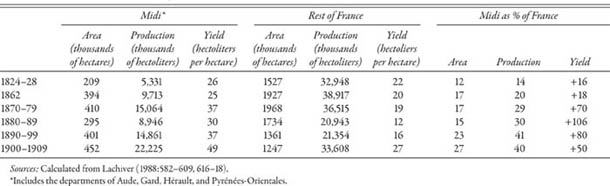

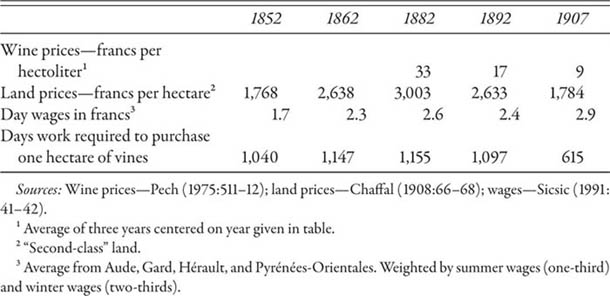

High prices caused by powdery mildew and the major drop in transport costs produced by the railways acted as a catalyst for the Midi’s viticulture, although while the area of vines virtually doubled between the late 1820s and early 1860s, yields changed little and the region continued to produce about a fifth of France’s output (table 3.2).25 Over the following two decades output increased to 30 percent of the national total, but this was now achieved by higher yields rather than extending the area planted. Phylloxera caused the area of vines to fall from its peak of 450,000 hectares in 1872 to 268,000 in 1886, but the exceptionally high wine prices and competitive nature of the region’s viticulture led to recovery of the area planted to 462,000 hectares in 1900.26 By the early twentieth century the Midi was responsible for two-fifths of French output and half of taxed wines sold, with the area under vines increasing by 15 percent compared with before phylloxera (1862); production growing by 130 percent; and yields being 50 percent more than the national average. The debate concerning overproduction from the turn of the century was linked specifically to the growth in output in Midi, as growers there were caught, more than elsewhere in France, between three adverse price movements: falling wine prices, declining land values, and rising labor costs (table 3.3). Small growers had problems to sell their wine even at the prevailing low prices.27

TABLE 3.2

Wine Production in the Midi and France, 1824–1909

TABLE 3.3

Movements in Factor and Wine Prices in the Midi, 1852–1907

Land prices are notoriously difficult to measure, but the drop of 40 percent for vineyards between 1882 and 1907 given by Chaffal in table 3.3 is perhaps an underestimate. The Fédération des syndicats agricoles du Gard, which represented seventy-two syndicates, argued that between 1895 and 1907 the value of vineyards had fallen by two-thirds; the Chambre de Commerce de Béziers gave a fall of 80 percent between 1900 and 1907; and the Société centrale d’agriculture de l’Hérault a fall of 75 percent between 1895 and 1907.28 The decline can also be seen by looking at individual properties. Thus the owner of one vineyard at Matelles (Hérault) of 144 hectares was offered 800,000 francs in 1896, but by 1900 it was valued at only 69 percent this figure. It was finally sold in 1905 at 28 percent of the 1896 figure, although the price had recovered to 47 percent when it came on the market again in 1912. Other vineyards tell a similar story.29 Falling prices were of particular concern to the large vineyard owners who had borrowed heavily, as the interest and loans had to be repaid in full.30

By contrast, labor costs rose 20 percent from an average of 2.4 francs a day to 2.9 francs. Vineyard owners responded by cutting labor requirements to a minimum, and wage labor was employed only 230 days a year. When wine prices briefly recovered, the workers struck for higher pay, and the Office du Travail recorded close to 150 strikes between November 1903 and July 1904 in the Midi, involving almost fifty thousand workers.31 The extent of the problems of higher wages and falling wine prices for estate owners can be clearly seen in table 3.3. While the wage:land price ratio remained relatively stable between 1852 and 1892, with slightly over a thousand days of labor needed to purchase a hectare of vines, this collapsed to little more than half the figure in the 1900s. In theory higher wages and lower wine prices should have been good for consumers. However, the importance of viticulture for employment and the depressed wine prices severely affected the rest of the local economy, and the number of vacant stalls at Béziers’s market, for example, rose from twenty in 1904 to thirty-three in 1905, sixty-two in 1906, and sixty-eight by February 1907.32 Despite this background of labor conflict, the large producers in the Midi successfully managed to identify their own economic problems with those of the whole region, making it easier to search for a political solution when prices collapsed in the first decade of the twentieth century.33

In the decade 1890–1900 wine in the Midi cost between 12 and 16 francs to produce and was sold for 18–20 francs per hectoliter.34 Between 1900 and 1906 prices fell to as low as 5 francs, and growers sold at cost or below in five out of seven harvests.35 Yet the causes of the crisis (la mévente) were not obvious. As some commentators noted, the net supply of wines in France in the early 1900s was not so different from the level immediately prior to phylloxera (table 3.1). What many believed had changed was the increased sale of artificial wines. As already noted, the financial difficulties caused by phylloxera had led to the authorities tolerating, if not encouraging, the production of artificial wines. After the Brussels Sugar Agreement of 1902, which reduced taxes from 60 to 25 francs per 100 kilos, there followed what one writer has described as “an orgy of fraud” in the Midi.36 Official wine production in thirty-five communities in Hérault totaled 1,004,915 hectoliters in 1903, but 2,284,848 hectoliters were actually sold, the difference being supposedly fraudulent wines. Nationally fraud was estimated at over 15 million hectoliters, equivalent to some 40 percent of the official harvest.37 The high level of fraud in 1903–4 was unusual, however, and caused by a combination of a poor wine harvest, which led to prices reaching their highest since 1887, and the very low tax on sugar. Wine harvests quickly recovered, pushing prices down to very low levels once more, and the government restricted the amount of sugar that growers could use and increased taxes. Unless growers could obtain sugar illegally, the profitability of sucrage after 1904 was greatly reduced.

Yet even if this form of adulteration temporarily declined, problems remained. In particular, growers were aware that any increase in wine prices was now likely to lead to a return of widespread adulteration. A second complaint was the lack of statistical information on production and stocks that made it difficult to know accurately the supply of genuine wines. Finally, if low prices discouraged growers from carrying out fraud, others in the commodity chain still found it profitable to do so. Thus the 1907 commission looking into the causes of the crisis argued that it was not the result of overproduction, but of the fact that the price of genuine wines was driven down to those of the artificially manufactured ones, which had been made from poor wines that would have previously been distilled but since 1903 were being treated by la chimie vinicole.38

As the Midi growers competed on price rather than quality, they demanded an increase in national consumption by lowering taxes and transport costs. The reduction in rail tariffs in 1896 increased the region’s competiveness against those from Spain and Algeria in the Bordeaux or Paris markets, which were transported by boat.39 The Loi des Boissons in 1900 lowered taxes, and that of 1901 removed the octroi, halving the tax revenues from wine.40 However, with per capita consumption at 168 liters in 1900–1904, there were obvious limits to a demand-side solution for low wine prices, especially as consumption of alternatives such as absinthe and beer had increased. For the 154,954 growers in the Midi, the continued sale of artificial wines was an obvious and visible explanation for low prices.41

Low prices hurt all producers, large and small, as well as those merchants who dealt with genuine wines. The major political influence in the Midi after 1901 was the Radicals, which defended the small producers, favored political democracy, and demanded greater social equality. Yet as Leo Loubère has noted, the wine defense group cut across party lines “and included deputies and senators who were moderate republicans, some who were royalists, and, after 1900, some socialists.”42 In particular, the wine crisis of 1907 showed relatively little of the class conscience that developed among industrial workers.43 Modern forms of political organization, such as public demonstrations, accompanied more traditional ways of protest, including the mass resignation of local political officers and tax strikes. Starting on March 24 with a meeting of 300 people in Sallèlesd’Aude, Sunday protests in 1907 quickly grew in size, and by May 5 some 80,000 took to the streets in Narbonne. A week later the numbers were 120,000 in Béziers, followed by 170,000 in Perpignan. By May 26 the figures had reached 220,000 in Carcassone; almost 300,000 marched in Nimes seven days later; and, finally, over half a million in Montepellier on June 9.44 Demonstrations of this scale were previously unknown in France and can be explained both by the large numbers of people in the Midi who depended directly or indirectly on viticulture and by the fact that the sector was united in its demands against the government in Paris.

The government had in fact already begun to respond, and the laws of August 1905 and June 1907 significantly reduced the amount of sugar that could legally be used in wine making, made it easier to prosecute fraudulent producers, and introduced measures to record growers’ production.45 The Confédération générale des vignerons du Midi (CGV) was created and became, in the words of Leo Loubère, “the wineman’s bulldog in the fight against fraud” as in 1912 the state officially allowed its agents to sue for, and collect damages from, those convicted of fraud.46 The broad base of its support within the wine communities was crucial to its success, and the CGV’s thirty agents in 1911–12 carried out 3,042 investigations that led to 601 successful prosecutions for fraud. For every ten cases initiated and involving wine fraud, the public prosecutor was responsible for just two, and the CGV of the Midi eight.47

FROM INFORMAL TO FORMAL COOPERATION:

LA CAVE COOPÉRATIVE VINICOLE

The CGV was also instrumental in encouraging growers to form wine-making cooperatives to take advantage of the cheap credit that the government made available to these groups after December 1906.48 Family grape producers could compete with large producers because of the high transaction costs associated with using wage labor in the vineyards, and because if necessary they simply worked longer hours. However, this was not the case in the winery, and they became increasingly uncompetitive because of their lack of scientific wine-making skills and capital to purchase adequate equipment and cellar facilities. In addition, wholesale merchants faced much lower costs when buying from one or two big wineries rather than having to collect from large numbers of different growers scattered over a wide territory, and transportation costs were lower when wines was shipped in bulk.

The result was that large wineries sold their wine at higher prices. For example, the huge Compagnie des Salins du Midi, with facilities to produce 100,000 hectoliters, was paid an average of 19.25 francs per hectoliter of wine in the period 1893–1913, against a regional average of 16 francs. By contrast, one small producer of just 400 hectoliters (Gélly) received 27 percent less than the CSM during the period 1893–1906. This difference was even greater in years with the lowest prices, with Gélly being paid only 4.8 francs in 1904, against 11.5 francs received by the CSM.49

Lack of cellar space was another problem facing a number of small growers (the non-logés). In some cases this arose because the area planted after phylloxera did not coincide with the old area of vines and small growers failed to build cellars, preferring to sell their wines directly from the vat. In other cases, they lacked the necessary capital to increase the capacity of their wineries to cope with the larger yields from the new vines or failed to maintain capital investment in their cellars when they were producing little or no wine during phylloxera. In the village of Marsillargues (Hérault), for example, growers only had storage for around 85 percent of the production (300,000 hectoliters); in Saint-Laurent d’Aigouzes (Gard) it was 75 percent (of 160,000 hectoliters); and in Bompas (Pyrénées-Orientales) only 47 of the village’s 227 winegrowers had cellar space to keep wines over the winter.50 Consequently growers in Marsillargues in 1897 sold 55 percent of their harvest in September, 14 percent in October, and just 31 percent over the following ten months.51

The crise de mévente of the early 1900s led a number of influential French writers, including Charles Gide, Michel Augé-Laribé, and Adrien Berget, to encourage the creation of wine cooperatives to reduce small growers’ production costs, and integrate vertically to absorb some of the marketing functions of merchants. By combining their scarce capital, several hundred family grape producers could build and equip a large winery to cut costs, pay for a skilled enologist to produce better-quality wines, and store these cheaply to be sold later in the year at higher prices. Wine cooperatives could also distill the remains of the grapes, and produce tartaric acid. Finally, they could act as banks, providing loans to their members.

The lower production costs associated with the new large, modern wineries were achieved by substituting capital for labor, an important factor even for family producers as labor requirements soared at the harvest time because of the need to rapidly collect the grapes, transport them to the winery, and crush them using labor-intensive methods. The state-of-the-art Flassans cooperative winery, for example, with a capacity of 5,000 hectoliters, required just nine workers employed for about twenty-five days to process 65,000–75,000 kilos of grapes daily, significantly less than the labor requirements for the 180 individual cooperative members if each had processed their grapes.52

The first attempt to establish a wine cooperative in France took place in Champagne in 1893 and ended in failure, but those from the turn of the century, especially in the South, were more successful.53 Although the low prices between 1900 and 1907 encouraged the formation of wine cooperatives (referred to at the time as filles de la misère), there were still only thirteen in all of France in 1908. However, rapid growth followed the law of December 29, 1906, and decrees of May 30 and August 26, 1907, which allowed wine cooperatives access to long-term credit at the almost uniform rate of 2 percent interest over twenty-five years.54 Capital was provided by the state but lent through regional credit banks, which were responsible for the loans. Transaction costs were greatly reduced because cooperatives were required to establish a specific legal structure to qualify. Between 1907 and 1914 around fifty cooperatives in southern France obtained loans covering an average of 47 percent of their capital costs, and the state gave subsidies of 815 thousand francs, or an additional 14 percent.55 In 1914 the twenty-one cooperatives that had been created between 1903 and 1910 had an average of 160.6 members and a cellar capacity of 13,100 hectoliters, and in 1913 they produced 7.9 thousand hectoliters of wine, or about 50 hectoliters per member, equivalent to about 1 hectare of vines.56

Perhaps the most famous cooperative was that of Maraussan (Hérault) of the vignerons libres. This was originally established in December 1901 to sell wine to consumer cooperatives in Paris, although as early as 1906 the members had constructed and equipped a modern winery, with an initial capacity of 15,000 hectoliters, and at a cost of 175,000 francs. The Ministry of Agriculture contributed 30,000 francs, the local regional bank (under the 1906 Law) provided a long-term loan of 109,000 francs, and a further 30,000 francs was raised from consumer cooperatives in Paris. The subscription of the 120 members was just 25 francs each.57 Therefore not only did growers in Maraussan and other cooperatives benefit from the economies of scale found in the larger wineries, but construction costs and the purchase of equipment were subsidized by the state.

There was widespread interest in Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in cooperatives, and although there were some spectacular successes, such as the Danish creameries, these were in general the exception. By 1914 there were still just seventy-nine wine cooperatives in France, of which fifty were found in the South, and their total production represented at most 1 percent of the nation’s output.58 Certainly winegrowers were “individualistic” and unwilling to trust some of their neighbors, as some contemporaries argued, but this was often for sound business reasons rather than any “cultural failing.” Spacious, clean, and scientific wineries promised to improve wine quality, but cooperative members required them also to be profitable and to be operated “fairly.” Two areas of potential conflict quickly appeared: the price to be paid for the grapes and the sale of the wine.

As discussed in chapter 1, many vineyards contained a number of different grape varieties as growers tried to reduce the risks of adverse climate conditions and disease. Grape quality also varied significantly from one year to the next, and winegrowers expected to receive a price that reflected these variables. However, cooperative workers could not check every basket of grapes used to make cheap wines and accordingly paid simply by their weight and sugar content. One solution was not to require members to sell all their grapes to the cooperative, but this risked them becoming depositaries for that part of the harvest that could not be sold elsewhere for higher prices. By contrast, when cooperatives forced their members to hand over all their harvest, the economic incentive for growers was to uproot their quality, shy-bearers, and plant high-bearers. In both cases, quality was driven down. Consequently, with the notable exception of Burgundy, wine cooperatives in France remained heavily concentrated in the South until at least the 1950s because in this region most producers already planted only a few varieties of high-yielding vines.59

The early cooperatives therefore failed to provide economic incentives for growers to improve quality, as Charles Gide in particular had hoped they would. They also had difficulties in selling directly to consumers. This was because members had limited information concerning market conditions to be able to monitor to their satisfaction the performance of cooperative managers, who on many occasions were simply fellow growers. Changes in wine quality and frequent, sometimes violent, fluctuations in market prices made it difficult for cooperative members to determine whether the prices they received were satisfactory and fair. The result was that while sometimes it was the cooperative that sold the wine, others preferred to leave it to the growers and avoid what might be considered a poor sale that might discredit the management.60

French cooperatives were also far too small to influence market prices.61 By contrast, a trust controlled approximately four-fifths of the wine market in California at this time, and this served for a couple of ambitious attempts by the very large landowners in the Midi to corner the market.62 Bartissol in 1905 proposed a marketing board that would sell annually 20 million hectoliters of branded wine in bottles directly to consumers. In case of overproduction, all growers would absorb the costs of distilling to reduce supply to support prices. However, many growers were reluctant to sign long-term contracts with an independent company. Even if a monopoly had increased wine prices, the capital requirements (300 million francs) and logistics of such a huge operation led to it remaining just a project. Palazy’s proposal in 1907 was more modest and involved the direct participation of growers, who would sell wine to wholesalers and retail merchants. With a capital of 48 million francs, growers were required to enter agreements for five years, and the company hoped to sell a minimum of 12 million hectoliters of wine. Although it claimed to have twenty thousand members and control 9 million liters of wine, it failed in 1906 as the Société civile de Producteurs de Vins naturels du Midi et de l’Algérie, and again in 1909 as the Société coopérative de Producteurs du Vins naturels du Midi, to negotiate discount privileges with the Bank of France and the Ministry of Finance.63 Just as important was the question of growers’ commitment, as there were strong incentives for them to remain outside the trust, as the potential benefits of higher prices would have been enjoyed by all, regardless of whether a grower was a member. When overproduction and low wine prices reappeared in the 1930s, growers looked directly to the state to resolve them, rather than create a private monopoly. Transaction costs associated with compliance were therefore reduced and absorbed by the state, with the resulting legislation (Statut du Vin) both regulating markets and helping the small producers.

The widespread protest in the Midi in 1907 marked a turning point in French wine history. Both powdery mildew and phylloxera had threatened the future of the nation’s winegrowers in a most dramatic way, but in both cases they required a scientific solution rather than market intervention by the state. The 1900s were not the first time that growers had been faced with overproduction, low prices, and widespread financial losses, but markets now showed no signs of correcting themselves automatically. Biotechnological advances encouraged growers to plant high-yielding varieties, and imports from Algeria increased year by year. The situation facing winegrowers in the 1900s was not dissimilar to that of Europe’s cereal producers in the 1870s and 1880s, when falling transport costs led to a growth in imports, and farmers could no longer benefit from high prices after a local harvest shortage, leading to the demand for tariffs to place a floor to domestic prices. A similar scenario of overproduction with wine was delayed by phylloxera. When prices did finally collapse after 1900, increasing tariffs on wines from low-cost producers such as Spain or Italy failed to resolve the problem because the cause of overproduction was found within France itself, and because cheap wines continued to be imported in increasing quantities from Algeria, part of France’s single market. In addition, any recovery in prices because of a domestic harvest shortage such as in 1903 was limited, as growers and merchants were encouraged to turn once more to fraud. The 1905 law provided the possibility of prosecuting the sale of artificial wines, and the creation of the Confédération générale des vignerons du Midi in 1907 established an effective institution to police the sector. This resolved the problem of competition from artificial wines, but not the tendency for wine production to grow faster than consumption, and the sector looked to the government for financial help to distill excess wines from time to time. With the next major crisis in the 1930s, the government had to start restricting the use of high-yielding grape varieties.

By the First World War small producers were becoming less competitive because of the new wine-making technologies and the greater market power of merchants, but in France they were compensated by their ability to influence farm policy. The rapid growth in agrarian syndicates after 1884 was in part the result of the economic demands of farmers in an increasingly competitive market, but it was also encouraged by politicians looking for votes. Cheap credit and subsidies allowed growers to establish wine-making cooperatives that enjoyed economies of scale in production and marketing and allowed small family producers to compete with large commercial wineries. In time, the cooperative proved an efficient institution to disseminate the benefits of agricultural research to small growers, but also for the state to regulate markets by holding back surplus production after large harvests.64 By 1952 cooperatives produced about a quarter of all French wine, and in the Midi about three quarters of all growers belonged to one of the 527 cooperatives.65

One possible solution to the weak domestic demand for French wines was to export. Charles Gide claimed that British and German consumers paid two or three times more than the French and continued:

Why is not the effort made? It is not clear whether the inertia of the French vinegrowers is to blame, or the indifference of English and German consumers, or, and this is probably the real cause, the exactions of the middlemen, of the English and German dealers, who play the part of importers, and who, snatching at bigger profits, try to sell the wines of South France at the same price as their clarets and ports, thus cutting them off from the average mass of buyers66

The following chapter looks at just this question.

1 Ordish (1972:149–50).

2 The Times, August 9, 1900, p. 8, cited in ibid., 148–50. See also Sempé (1898:87–88, 96).

3 Ordish (1972:144).

4 Warner (1960:13).

5 Degrully (1910:325).

6 Ibid., 356.

7 All cited in Warner (1960:37).

8 Sempé (1898:205). The peseta recovered after 1898. For the free port for Spanish wines, see chapter 5.

9 For French exports, see Pinilla and Ayuda (2002:51–85); Simpson (2004:80–108).

10 Stanziani (2003).

11 Sempé (1898:102, table 3).

12 Stanziani (2003).

13 Judt (1979:272). Emphasis in the original.

14 Gide (1907:370).

15 Guyot (1868, 1:i).

16 Loubère (1978:167); Prestwich (1988:10).

17 Gide (1907:370–72).

18 Figures refer to 1895. In Paris there were 27,000 retailers, one for every 87 inhabitants. Excluding Paris, there were 366,000 retailers in 1869 Sempé (1898:104–6).

19 Wright (1964:14).

20 Ibid., 13.

21 Campbell (2004:168).

22 International Institute of Agriculture (1911, 1:256–57).

23 Sheingate (2001:54–55).

24 Ibid., 64. According to this author, the institutional setting for agricultural policy revolved around three distinct variables: the pattern of political competition in each country, the structure of the agricultural bureaucracy, and the organizational strength of different farm groups (p. 39).

25 In the ancien régime, the privileges enjoyed by Bordeaux also restricted markets for Midi wines (Dion 1977:393; Augé-Laribé 1907:34–36). The Midi’s specialization in spirit production encouraged some growers to use high-yielding vines from an early date.

26 Pech (1975:496–97).

27 The parliamentary commission established in 1907 to look into the causes of the national wine crisis noted that the Midi and Algeria were the worst-affected regions in France (Chambre des députés 1909:2307). It was headed by Cazeaux-Cazalet, a deputy from the Gironde.

28 Quoted in Chaffal (1908:61–62).

29 For example, in Ginestas (Hérault) a vineyard was sold in 1901 for 37 percent of its estimated value in 1889, and in Bouches-du Rhône one was sold in 1905 for less than 20 percent of its value seven years earlier (Caziot 1952:226–28). Postel-Vinay (1989:184) suggests that creditors refrained from foreclosing properties in 1906 and 1907, preferring to wait until the wine market recovered.

30 Postel-Vinay (1989:171–77) shows the high levels of debt facing the large vineyards in the Midi.

31 For these conflicts, see Smith (1978: 106–11) and Frader (1991:75, 92–93, 121–25).

32 Caupert (1921:22–28); Augé-Laribé (1907, chap. 10).

33 Carmona and Simpson (1999:311); Simpson (2005).

34 Gide (1907:370).

35 Warner (1960:18). One calculation suggested that a local wine price of 10.7 francs per hectoliter was needed to cover variable costs, and 14.3 francs to cover fixed costs, but this second figure was reached only twice in the Midi during the 1900s (Atger 1907:23–27). For prices, see Pech (1975:512).

36 Warner (1960:14, 40).

37 Degrully (1910:350, 353). Atger (1907:73) suggests a figure nearer 8 million hectoliters.

38 France, Chambre des députés (1909:2307–8).

39 Sempé (1898:175–77). Caupert (1921:36) notes that rail tariffs were cut by 50 percent in 1890.

40 Warner (1960:32).

41 Growers refer to 1900–1909 (Lachiver 1988:588–89). Some contemporaries also argued that high domestic tariffs restricted export markets (Warner 1960, chap. 3).

42 Loubère (1974: xv, 177).

43 Ibid., 3, 189.

44 Frader (1991:141); Lachiver (1988:468).

45 Warner (1960:41); and Frader (1991:145).

46 Loubère (1978:355).

47 Ibid.

48 Caupert (1921:83, 112).

49 Pech (1975:158).

50 Mandeville (1914:43).

51 Cot (1900), cited in Gervais (1913:50).

52 Mandeville (1914:95). The cooperative had a double crusher-stemmer that processed 24,000 kilos per hour; a pump that moved up to 20,000 kilos of crushed grapes per hour; a wine pump with capacity of 180 hectoliters per hour; a hydraulic press with a pressure of 120,000 kilos per square meter, etc. (Arnal, Progrès agricole, August 10, 1913), cited in Mandeville (1914:93).

53 In France, societies for the collective manufacture of cheese (fruitières) date from the twelfth century and remained by far the most common of producer cooperatives, numbering 2,485 against only 39 wine cooperatives in about 1910 (International Institute of Agriculture, 1911, 1:280). In northern Italy a similar institution, the turnario sociale, dates from slightly later. For champagne, see Clique (1931:14). For the Champagne cooperative, see chapter 6.

54 Caupert (1921:111); Gervais (1913); and Mandeville (1914:2, 11).

55 Mandeville (1914:139). This author noted that some cooperatives were not finished and therefore expenditure would rise, reducing these figures slightly.

56 My calculations from ibid., tables 1 and 2. Using the full sample of fifty cooperatives, which includes some that were not finished, in 1913 there were an average of 135.2 growers, enjoying a cellar capacity of 11,200 hectoliters, with a production of 6,400 hectoliters, or 47 hectoliters per grower.

57 Gide (1926:129–31).

58 Simpson (2000, table 5). In Italy, a short-lived cantina sociale was established at Bagno a Ripoli near Florence in 1888, and by 1910 there were reportedly “slightly in excess of 150,” and a further 40 cooperative distilleries were also active (International Institute of Agriculture 1915a, 2:152).

59 The growth in the cooperative movement in Burgundy from the late 1920s involved fine wines produced on miniscule vineyards often of less than half a hectare. The wine price covered the considerable monitoring costs associated with controlling vineyard activities. Growers were paid not just by the grapes’ weight and sugar content, but also by the variety, and growers were obliged to sell all their production to the cooperative. Only certain shy-bearers were permitted, and the vendage was done collectively. See especially Clique (1931:21–60).

60 This was the reason given for the Marsillargúes cooperative, the largest one in the Midi in terms of cellar capacity, at 60,000 hectoliters (Mandeville 1914:111–12). See also Cique (1931: 187).

61 Hoffman and Libecap argue that cooperatives can raise prices only if the product is relatively homogenous, stocks difficult to accumulate, and a significant number of individual growers agree to output cuts that can be easily monitored (Hoffman 1991:397–411).

62 Atger (1907:116–22); Degrully (1910:375–85); Postel-Vinay (1989:180–81). For California, see chapter 9.

63 Caupert (1921:64–65).

64 Knox (1998:15).

65 Calculated from Bulletin de l’Office International du Vin 290 (1955): 40–41. There were fifty cooperatives in the Midi in 1924 (Augé-Laribé 1926:141).

66 Gide (1907:374–75).