CHAPTER 10

![]()

Australia: The Tyranny of Distance and

Domestic Beer Drinkers

The production of wine in Australia has not increased as rapidly as the suitability of soil and climate would appear to warrant. The cause of this is probably twofold. . . . Australians are not a wine-drinking people and consequently do not provide a local market for the product, and . . . the new and comparatively unknown wines of Australia find it difficult to establish a footing in the markets of the old world, owing to the competition of well-known brands.

—Australian Official Year Book 1901–7, 328,

cited in Osmond and Anderson, 1998: 1.

THE AUSTRALIAN WINE INDUSTRY dates from the end of the eighteenth century, but as in California and Argentina, it was only in the two or three decades prior to the First World War that it became commercially important. The early settlers and government authorities were attracted to viticulture because it was a labor-intensive crop, allowing larger settlements than found with extensive livestock or cereal farming. From a social perspective, it was believed that wine-drinking Europeans became less drunk than spirit-drinking Australians, while the government saw wine as a potential export commodity and source of taxation. However, Australia suffered from a small, fragmented national market, and producers were forced to look to the British market. Despite a distance of 20,000 kilometers and receiving no preferential tariffs, exports of unfortified “full-bodied dry red wine” grew from 2,700 hectoliters in 1885 to peak at 45,000 hectoliters in 1902, equivalent to a fifth of those from France and representing 6 percent of Britain’s total imports.1 This market required Australians to be at the forefront of technological change, and Alexander Kelly attempted to cool wines during fermentation as early as the 1860s.2 By contrast, Australia’s own domestic consumption remained at little over 2 liters per capita, often of poor quality, although the production of brandy was becoming an important sideline for large wine producers by 1913.

The first two sections of this chapter look at how Australians learned to grow grapes and make wine, and the advances in wine-making technologies linked to dry table wine production. The next section considers the problems of vertical coordination, or “cooperation” as contemporaries called it, between grape growing and wine making. The final one shows that the Australian commodity chain differed from California in that it was market driven from Britain and explains why attempts to create an alternative Australian distribution network failed.

LEARNING GRAPE GROWING AND WINE MAKING

Vines were brought on the first boat arriving with settlers in 1788, but there were still only around 800 hectares in 1856, when The Times reported that Australian wine production was the pursuit of a few wealthy landlords and “more a fancy than an industry.”3 By 1866 the figure had jumped to 5,500 hectares, as the vine spread from New South Wales to other states where growing conditions were easier, with South Australia accounting for roughly half the area, Victoria three-tenths, and New South Wales a sixth. A half century later, and including only those grapes used for wine, South Australia (57 percent) continued to dominate, followed by Victoria (22 percent), whose production was decimated at this moment because of phylloxera, and New South Wales (18 percent).4

Demand for wine remained limited because of the large distances between settlements, high duties facing interstate trade before federation in 1901, and small size of the major cities, with Melbourne only reaching 100,000 inhabitants in 1861, and Sydney in 1871. Yet despite these problems, contemporaries initially worried more about the lack of grape-growing and wine-making skills so obviously absent among the early British settlers, as well as the fact that many of them also had no appreciation of how wine should taste.

To help resolve these problems, a number of settlers, including John Mac-arthur (1815 and 1816) and James Busby (before 1824 and in 1831), traveled to France to learn grape-growing and wine-making skills and collect vine stock. Busby had already lived in Cadillac (southwestern France) prior to his arrival in Sydney, and his Treatise on the Culture of the Vine, published in Australia in 1825, was inspired by the country’s need to produce export crops. His next book, A Manuel of Plain Directions for Planting and Cultivating Vineyards and Making Wine in New South Wales (1830), was the first to be written on the subject with Australian conditions in mind and was widely distributed within the colony. Busby published his classic Journal of a Tour through Some of the Vineyards of Spain and France after visiting these countries in late 1831, and he made detailed observations on grape varieties, cultivation techniques, and wine making and suggested that the secret of producing fine wines was high levels of capital investment.5 Busby collected 543 different varieties of vines, of which 437 came from Montpellier in southern France, and those that survived the long journey were planted in Sydney’s botanical gardens and circulated among other growers. Just like Arthur Young, another great traveler whom Busby much admired, there is little evidence that he was a particularly successful grower himself.6

The wine boom of the early 1860s led to other important publications, including Dr. Alexander Kelly’s The Vine in Australia (1861) and Wine Growing in Australia (1867), while Ebenezer Ward published a series of newspaper articles on the leading vineyards in Victoria and South Australia. In 1892 George Sutherland’s South Australian Vinegrower’s Manual became the first of many official publications to appear, while the Australian Vigneron and Fruit-Growers Journal, first issued in 1890, allowed state viticulturalists such as Arthur Perkins, Malcolm Burney, and Francois de Castella a forum to inform readers of European advances. Despite the title, this journal represented more the interests of the large winemakers and merchants than the humble grower.7

The shortage of skilled labor was partly eased by immigration. When Charles La Trobe arrived in 1839, Melbourne had only a couple thousand inhabitants, and he encouraged over a hundred vignerons and agricultural laborers from Neuchâtel, one of the few Swiss wine-growing regions, to settle. According to the historian John Beeston, within “ten years of its foundation there were not only numerous small vineyards in Melbourne and nearby areas, but also in Geelong and the Yarra Valley.”8 The Barossa Valley was initially farmed by settlers from Silesia in Prussia, although French experts arrived in the 1880s, including Edmond Mazure and Charles Gelly, who managed the Auldana Vineyard and was considered one of the best local winemakers.9

It soon became apparent that despite the importance of these immigrants in establishing the early industry, many brought with them knowledge and skills that were highly localized and often inappropriate to Australian conditions. Winemakers therefore traveled themselves, so much so that by the early 1890s Thomas Hardy of South Australia argued that they had become more knowledgeable than Europeans:

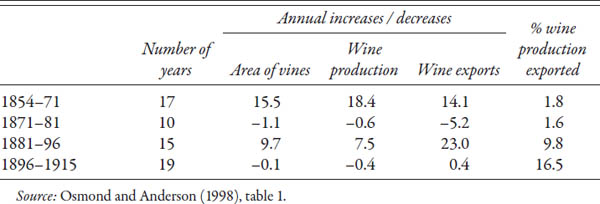

TABLE 10.1

Cycles of Growth and Depression in the Australian Wine Industry, 1854–1916

It is thought by many that the vignerons of Australia have had very little experience, but that is a great mistake; as a rule we know more about wine-making and vine-growing than nineteen out of every twenty that come from Europe: their knowledge is almost always confined to the practices of their own immediate neighborhood, whilst many of us, in addition to 30 or 40 years’ experience here, have had the advantage of the ideas of men from nearly all the wine-growing countries of the world, and also of travel in them ourselves.10

Hardy himself traveled extensively, most notably in the early 1880s when he wrote Notes on Vineyards in America and Europe, which contains detailed descriptions of the industry in California, Portugal, and Spain. Other Australians who studied European wine making included the Basedow brothers, Frank Pen-fold Hyland, Leo Buring, Charles Morris, and Oscar Seppelt.11

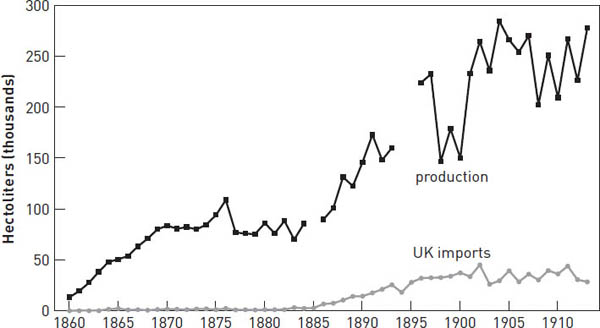

The gold rushes hampered the early industry by creating labor shortages, but they also brought benefits in the form of capital for investment, an increasing number of non-British immigrants, and a potential market for wine. From a very low base, and with not very trustworthy figures, the area of vines increased by an annual 15 percent between 1854 and 1871, wine production by 18 percent, and exports by 14 percent (table 10.1). However, as in California, the excessive production of poor-quality wine restricted demand and lowered prices, and during the following decade output fell from 806,000 to 760,000 hectoliters, and the area under vines from 6,976 hectares in 1871 to a low of 6,227 hectares in 1881.12 The recovery can be dated from the late 1880s as wine production virtually doubled between 1886 and 1891 and coincides with a period when contemporaries were aware of the need to improve quality. While better wine-making facilities began to appear, the rush to plant in the late nineteenth century, especially in Victoria, brought with it a flood of the cheaper grape varieties.

The need to improve wine making is evident in the discussion by the South Australian Vinegrower’s Association concerning the appointment of the state’s first viticulturist. A speech by Thomas Hardy was reported in the Australian Vigneron:

The selection of soil and sites for vineyards; the best available kinds to plant, the best modes of preparing the land and planting, the training, and pruning, and general cultivation, were generally well-known already, and beginners could always easily get the advice necessary for all these operations from those who had a long experience. Therefore he did not consider that we wanted or could be taught much more than we knew already by anyone coming from Europe in those matters. . . . A man who, having had a good training in the chemistry of wine, would, after some experience of our climate and general conditions, enable him to give advice in the all-important matter of fermentation, how it might be regulated and controlled in our variable weather during the vintage, how certain defects in our wines, arising from imperfect fermentation, could be overcome or prevented, and how wines which might get into bad condition could be rectified or improved.13

The problem, as has been noted before, was that the high temperatures found in many areas led to cessation of the vinous fermentation and acetic or lactic fermentation taking place, producing an unstable and “sweet sour wine.”14 The subsequent appointment of Arthur Perkins in 1892, a twenty-one-year-old English speaker who was a graduate of Montpellier’s L’École Nationale d’Agriculture and had practical experience in Tunisia and knowledge of the rapid advances taking place in the production of dry table wines in hot climates, proved to be inspirational. In addition, the entrepreneurial leadership provided by Thomas Hardy and others resulted not just in the appointment of professionals such as Perkins, but also in the establishment of Roseworthy College, just west of the Barossa Valley.15 South Australia enjoyed one other important advantage over the other colonies: it has remained phylloxera free even until this day.

Government assistance in the state of Victoria was very different. Phylloxera first appeared in Geelong in 1878, and the diseased vines were uprooted and destroyed with growers receiving compensation. Victoria actively encouraged the planting of labor-intensive crops to increase the number of farmers, with a bonus of £2 per acre being offered for each new acre of vines (£3 for fruit cultivation), which led to around 4,500 hectares of vines being planted by 1,400 vignerons between 1889 and the end of 1893.16 Most vignerons had little or no experience, and they lacked capital and the skills to make sound wine. These planting bonuses produced considerable opposition from established growers because the increase in poor-quality wines led to a fall in grape prices,17 and the problem was resolved only with the reappearance of phylloxera in Rutherglen after 1897.18

By 1898 Victoria already had two of the five agricultural colleges open in Australia (Dookie in 1896 and Longeronong in 1889), a viticulture college established at Rutherglen, and a horticultural school at Burnley. In 1898 Raymond Dubois was appointed principal of Rutherglen, and shortly after he was given the task of leading the fight against phylloxera, which was again devastating the district.19 The viticulture college, however, failed initially to live up to expectations, and when the Victoria’s minister of agriculture visited it in February 1901 he found new dormitories but no students.20 Dubois was now instructed to visit wine producers and teach modern wine making, and with Percy Wilkinson and Edmund Twight he also translated from French a number of important books, including those by Roos (Wine Making in Hot Climates) and Pierre Viala and Louis Ravaz (American Vines: Their Adaptation, Culture, Grafting, and Propagation).21

Finally, although New South Wales benefited from Sydney being Australia’s largest protected urban market, viticulture grew only slowly, and growers complained on the eve of federation of the lack of state support, compared to that received in Victoria: “no bonuses to assist them; secondly, only recently have they have been offered expert advice; thirdly, they have no experimental stations or places of instruction; fourthly, the dissemination of information etc. has been conducted on such spasmodic and unsatisfactory lines as to prove little or no practical use.”22

ORGANIZATION OF WINE PRODUCTION

The abundance of land and the weakness of demand led to most growers planting other crops among their vines. In the Barossa Valley, for example, the “three primary industries”—mining, grazing, and viticulture—proceeded side by side during the 1860s, while Ebenezer Ward noted that at one Victorian vineyard the owner had alternated walnut trees with vines with the intention of uprooting the least successful.23 Most vineyards were also small. In Victoria in 1890 before the planting bonus there were 850 growers with more than 0.8 hectare, but 511 of these had only between 0.8 and 4 hectares. A further 244 farmed between 4 and 12 hectares; 68 between 12 and 24 hectares; and 13 between 24 and 36 hectares. There were only 14 vignerons with more than 40 hectares of vines, with the largest being 144 hectares.24 A significant number of growers held less than 0.8 hectare. The total number of Victorian growers peaked in 1896, with 2,975 vignerons cultivating an average of just over 4 hectares each, before declining to 1,776 in 1914 (with an average holding of 5 hectares).25 However, these figures are distorted by the inclusion of producers who grew grapes for uses other than wine. In 1914, for example, about two-fifths (700) of growers were found in the Mildura district, where no grapes were used for wine making. By contrast, Rutherglen’s 116 growers produced 16,711 hectoliters, or 40 percent of the state’s production in that year, giving an average of 144 hectoliters per grower.26 The small scale of grape-growing activities was also found in New South Wales, while in the Adelaide region in 1892 three quarters of the 753 growers worked between 0.4 and 4 hectares of vines; 175 between 4 and 12 hectares; 46 between 12 and 24; 17 between 24 and 36, with just 7 with more than 36 hectares.27

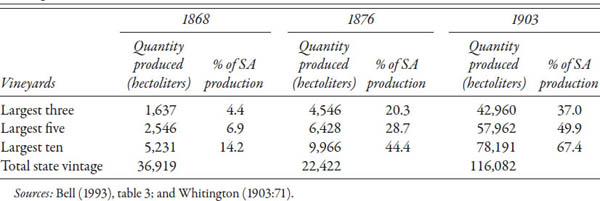

Even the largest vineyards were relatively modest affairs compared with California. According to Whitington, Fowler’s Kalimna vineyard in the Barossa Valley was the biggest in South Australia in 1903 with 132 hectares of vines, followed by Kelly’s Tatachilla vineyard (124 hectares) in the McLaren valley.28 The Kalimna vineyard bought large quantities of grapes produced in the neighboring district, but the Tatachilla vineyard started making wine only in 1903, after losing a contract to supply grapes to Thomas Hardy. By contrast, by far the biggest winemaker in the Barossa (and in Australia) was Seppeltsfield, producing an estimated 20,000 hectoliters, or five times Kalimna’s production in 1903. This winery had less than 50 hectares of vines of its own and bought grapes from 165 private growers within a radius of 25 kilometers of the estate.

If vineyards remained generally small family concerns, the increasing economies of scale associated with the new wine-making technologies in hot climates such as Rutherglen or the Barossa eroded the competitive position of the small winemaker.29 As early as 1882 Thomas Hardy noted that “the manufacture of wine is now almost wholly gone into the hands of those who make a business of it, and do not follow it merely as a secondary pursuit,” leading to a concentration in the industry (table 10.2).30 By 1900 the new wine-making technologies included refrigerators, continuous presses, aero-crushing turbines, sterilizers, and pasteurizers, and these helped create economies of scale in four important areas. First, considerable skills were required in wine making if growers were going to produce a dry table wine that would keep. By the 1890s the leading wineries were attempting to control the temperature of the must during fermentation and using cultivated yeasts. Hardy, for example, claimed to “keep a highly-paid man as an expert in the chemical and bacteriological department, and we have highly-paid skilled men in the manufacture of the wine, and it is that part of the business which is the primary business, not a secondary one.”31 Second, new wine-making technologies and cellar designs helped to cut labor costs, an important consideration in a high-wage economy such as Australia’s. Third, merchants demanded large quantities of wines of a uniform style that could be repeated each year, which was impossible for small producers to achieve. Finally, large-scale wine production encouraged distilling and the development of the brandy and fortified wine industries, which after the 1906 legislation was possible only on a large scale. By 1914 a number of houses, such as Penfold or Seppelt, were reinforcing their corporate brands through the sale of brandy and dessert wines. Brandy was a highly profitable business but open only to the large producers, as a government excise officer had to have permanent offices at the distilleries, allowing Penfold to claim that it was a “Government guarantee” that all its brandy was made from the wine of grapes, and that the state laws on maturing the brandy were properly respected.32

TABLE 10.2

Leading Winemakers in South Australia, 1868, 1876, and 1903

The new gravity-flow Seppeltsfield winery that opened in 1888 was one of the most advanced of the period. To keep labor costs to a minimum, the winery was built down a hillside, with the sixty fermenting tanks (each with a capacity of 90 hectoliters) arranged on three terraces. Wooden chutes allowed the winemaker to direct the must and wine to the desired vats, and in 1890 tin-platted copper cooling coils were installed to regulate the temperature.33 Center pumps were used to mix the different parts of the liquid, to keep the temperature inside the vat uniform, and to obtain the maximum coloring and extractive matter by causing the juice to repeatedly pass through them. Seppelt started using cultivated yeasts imported from Europe in the early 1890s, but by 1899 its laboratory was propagating its own.34 The winery had two steam-powered crushers and hydraulic presses that could each process 100 tons of grapes a day. Even by international standards the Seppelt winery was impressive, and B. W. Bagenal, a student for three years at Montpellier and representative of the London importers in Adelaide for over two years, noted that he had personally visited seven of the ten best French and Algerian vineyards cited in a recent book, and “he had confidence in saying that there was no place he knew of where the industry was better carried on than at Seppeltsfield.”35

The high level of vertical specialization in grape growing and wine making found in South Australia was less common elsewhere in Australia.36 The advantages of specialization were also hotly debated within the profession. In particular, Arthur Perkins spoke of the “two separate classes with antagonistic interests—vignerons on the one hand, winemakers on the other.”37 He blamed winemakers for the low prices being paid in 1899 and argued that the creation of state-sponsored regional depots would save growers the cost of storing wine before shipment and allow wines to be blended, which would remove the problem of limited production from family vineyards. Dubois in Victoria argued that small growers should form wine-making cooperatives and obtain modern equipment and, “more important than anything, and cannot be too much emphasised,” benefit from technical education.38 By contrast, and not unnaturally, the large wine producers and their trade paper, Australian Vigneron, as well as London importers believed that large, privately owned wineries buying grapes from specialist growers were more efficient. The presence of independent growers did allow however for a rapid response to upswings in demand. The £2 bonus offered to Victorian growers, which saw the area of vines increase by 50 percent between 1890 and 1894, would not have occurred if growers also had to invest in new cellars.39 Between 1889–91 and 1911–13 Australian wine production increased from 147,000 to 256,000 hectoliters, and while not all of this expansion took place in hot climate areas and the introduction of new technologies was inevitably slow in some wineries, contemporaries linked the ability to produce better wines with the growth in the area of vines. As W. & A. Gilbey wrote in their annual letter to The Times on the state of the wine market in 1908, “Australian wines have improved in quality to a remarkable extent in the last few years. The inferior vintages are now distilled into brandy, and the wines remaining are, with exceptions, excellent.”40

Burgoyne and Seppeltsfield illustrate how winemakers coordinated with their growers to adapt to changes in demand. The British importer Burgoyne bought the Mount Ophir vineyard in 1893, and the investment in new wine-making facilities led one contemporary to note that “it would be difficult to find in any part of the world a winery in which California labor saving appliances and the most approved European methods of securing the best treatment of the wine are so completely adopted.” Burgoyne contracted out for most of his grapes and bought wine from other producers, blending it all in cellars that had a capacity of 34,000 hectoliters (750,000 gallons). Burgoyne was interested only in “full-bodied red wines” of less than 15 degrees, which were exported after nineteen months. The expansion of trade saw grape prices rise from about £2 to £5 per ton by 1909, but this specialization for a niche market had its risks. In early 1909, in the midst of the local devastation caused by phylloxera, the company demanded price cuts to remain competitive in the British market.41 D. B. Smith, chairman of the Vinegrower’s Committee, argued that growers would not replant but turn their land to “other purposes” if prices were reduced. He told growers that they were too dependent on the London market for dry red wines and should consider growing grapes for sweet wines, noting that “there were only three or four buyers of wine for the London market, while there are upwards of 20 for the Australian sweet wines.” Burgoyne backed down, and a full page advertisement appeared in the Rutherglen Sun and Chiltern Valley Advertiser under the title “For the Sake of the Industry,” offering £7 per ton of grapes for “Carbinet, Shiraz and Malbec” and £6 10s per ton for other varieties for the next (1910) vintage. This offer was subject to “certain technical conditions,” namely, that growers replant their phylloxera-devastated vines.42 While the dry red wine market was very profitable for Burgoyne between 1885 and 1914, it became much less so in the interwar period when demand switched to fortified wines. Being located in an area where conditions were optimal for dry red wines perhaps explains the firm’s failure to spot the shift in demand in Britain to dessert wines in the interwar period, as it required the company to look for supplies in other, more suitable areas such as Milawa.43

The Seppelt winery also adapted to changing market conditions by changing the grape prices it offered, with the price for cabernet sauvignon, for example, being cut from £7 per ton in 1899 to £4 17s. 6d. in 1911, while the price of Shiraz was increased from £4 to £4 17s. 6d., and white hermitage and riesling from £3 5s. to £4 5s. between the same years.44

As Burgoyne discovered in 1909, growers were not totally dependent on an individual wine producer. Furthermore, they could leave the industry at times of low prices as their investment was limited to vines, which threatened to leave the capital-intensive wine-making firms without grapes. Growers could, and at times did, simply exit, with perhaps the most famous being the Yarra Valley (Victoria), where in the 1920s, in the words of Beeston, “the advent of the Jersey cow was equally devastating as phylloxera had been fifty years before in Geelong.”45

IN SEARCH OF MARKETS

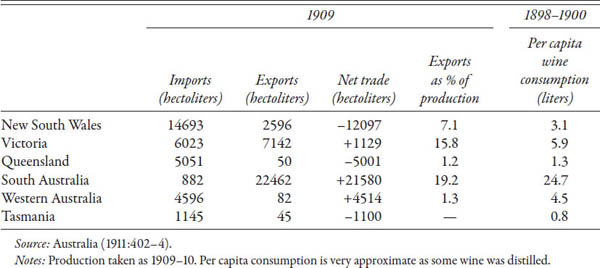

A major problem facing the new industry in Australia was the lack of markets. Not only did Australia have a much smaller population compared to Argentina or the United States, but the dominance of British people among the settlers discouraged wine consumption. As late as 1890 it was claimed that “more than half of the Australian wine drunk here is consumed by Italians, French and Germans.”46 Sales outside individual states were also restricted because of high tariffs and remained limited even with free trade after October 1901. In 1909, for example, the last year that figures are available, only 7.1 percent of New South Wales’s production, 15.8 percent of Victoria’s, and 19.2 percent of South Australia’s was sold to other states (table 10.3).47

TABLE 10.3

Australian Interstate Trade and Wine Consumption

Wine quality and industrial organization were significantly influenced by the nature of market demand, although there were important differences between the domestic and international markets. The early South Australian industry, as elsewhere, was limited to local rural markets and on-farm consumption, and wines were often adulterated before being drunk.48 As Mücke noted in 1866, “hundreds of wine cellars, belonging to men of the middle and poorer classes, are filled with wines spoiled by unskillful treatment, which have swallowed up all their capital and destroyed all their hopes.”49 High state tariffs allowed producers in New South Wales and Victoria access to growing urban markets (table 10.4), but Richard Twopenny wrote in his Town Life in Australia, first published in 1883, that Australian wines were “too heady, and for the most part wanting in bouquet, whilst their distinctive character repels the palate, which is accustomed to European growths.” Yet he claimed that some were much better than the expensive, imported wines, and that despite a duty of 10 shillings a dozen, “large quantities of Adelaide wine are drunk in Melbourne,” although its chief characteristic was its “sweetness and heaviness.”50 By the turn of the century Raymond Dubois lamented that internal tariffs allowed Victorian growers high profits, “peddling their inferior wines in small quantities to local markets,” and he believed that one-third of Victoria’s wine was unfit for consumption as wine and had to be distilled, “a positive proof that there is something fundamentally wrong” in the manufacturing methods adopted in the industry.51 A study of the chemical composition of a sample of 103 wines in the Melbourne area showed that a third had been adulterated with salicylic acid.52

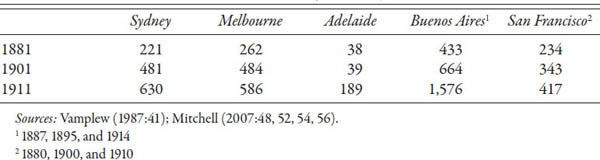

TABLE 10.4

Select Urban Centers in the New World, 1881–1911 (thousands)

In the 1890s large numbers of small producers in Victoria created poor-quality wines that inevitably lacked uniformity.53 There were also problems for the casual drinker: “Try and get a glass of Colonial wine in a Melbourne hotel, and in nine cases out of ten you will be served at an outlay of 6d. with a small glass, of which measure it takes from 8 to 14 to fill a common wine bottle, and such a bottle is taken from a shelf in a bar, where its contents have been stewing in the hot atmosphere, after having been uncorked and left half full, perhaps, a fortnight before!”54

If Victoria and New South Wales had the country’s two largest cities as captive markets, this was not the case with producers in South Australia. Attempts to produce wines for export in the 1870s failed,55 but twenty years later the South Australian industry had been transformed by a handful of winemakers to one where important economies of scale were achieved in production and the major markets were Britain and, after federation, the urban centers of Melbourne and Sydney. Between 1885 and 1913 Australian wine imports in Britain increased from 0.27 to 2.84 million liters, peaking in 1902 at 4.5 million (fig. 10.1). In 1902 British imports from Australia were equivalent to 19 percent of those from France, 24 percent from Spain, and 25 percent from Portugal, and they were 250 times greater than those from the Cape.56 The British market accounted for virtually all of Australia’s wine exports and the equivalent of a fifth of the country’s harvest in that year. The rapid growth in exports was achieved by producers in South Australia and Victoria, who each accounted for roughly half of the British market.57

Figure 10.1. Australian production and UK imports. Sources: Osmond and Anderson (1998: table 2) and Laffer (1949:124–25)

The British demand was for dry red table wines, often confusingly referred to as a “Burgundy type” and described as being somewhere “between the heavily fortified wines on the one hand, and light wines, such as clarets and hocks on the other.”58 A British study in the early 1870s claimed that approximately 60 percent of South Australian wines found in two samples of fifty-six and seventy wines, respectively, had been “fortified,” but this was based on the assumption that no “natural” wine could be stronger than 14 or 15 degrees alcohol, a claimed disputed by the South Australian government.59 Virtually all Australia’s exports, some 99 percent in 1907, paid the minimum shilling duty per gallon, although by this date it had increased to wines under 30 degrees proof.60 By contrast, no Australian port or sherry type wines were exported before 1914, as producers could not compete with Portugal and Spain.

Australian producers of nonfortified table wines enjoyed a number of advantages over those from Europe to offset the significant transport and transaction costs that distance created. One factor was that Australia’s wines, if properly treated, had “naturally far greater keeping qualities than many European wines.”61 Quality also fluctuated much less from one harvest to the next, although this did not automatically imply that a homogenous wine was produced, as The Times noted in 1893: “At present one of the principal complaints which are made by buyers of Australian wine is the absence of uniformity, but this inequality is an inequality of manufacture, which is purely accidental, and to be distinguished from the fundamental inequality produced by the uncertain climate of France and Germany.”62

Quality differences between vineyards and grape varieties were resolved by blending, as the minimum quantity of wine accepted by shippers was usually considerably beyond that produced by most growers. Thus Blandy Brothers suggested that “it is almost useless to consign small parcels of wine, 10 or 20 hogsheads, which they are not in a position to repeat each year,” while Pownall offered to buy red Australian wines “suitable for the English market in parcels of 1000 to 10,000 gallons.”63

Yet these advantages would have been insufficient in the absence of an efficiently organized commodity chain. Significant barriers to trade existed between Britain and Australia. The first was caused by the 20,000 or so kilometers between buyer and seller. In the late nineteenth century this required a shipping time of six weeks, instead of the three days from France, and implied freight costs of approximately three times more.64 Another major problem was that the long sea voyage and the extremes in temperature caused by the change in seasons as the ships crossed the equator resulted in all wines, “especially the young wines and wines that have not been thoroughly well made” to undergo a “very considerable and detrimental change.”65 Wines required several months rest on arrival, and faulty or young ones were often permanently ruined. The problems of asymmetric information created by distance and the possibility of wine undergoing significant changes in quality encouraged opportunistic behavior on the part of both Australian exporters and British importers. Australian producers might believe that they exported a good wine, but British merchants could claim that it arrived in poor condition and they were only willing to pay low prices. One prominent London West End merchant who imported 60 hogsheads of South Australian wine because of its growing popularity found it so “ill-fermented” that it resolved never to import any more directly from Australia.66 The result was that even the leading Australian producers found it difficult to find agents for their wines, as the Pall Mall Gazette noted in 1884:

In the European wine trade there is seldom a change of agencies, but no man holds an agency for Australian wines long, or cares to invest money in the venture. The Auldana agents have been many, but all have retired from their speculation. Fells no longer pushes Irvine’s wines. Why is this? There surely is a good profit to be made in the trade. The reason must be found in the absence of friendly cohesion, or other unexplained cause between the wine-grower and his representative. Penfold & Co. are moving heaven and earth to secure an agent, but men fight shy of laying out their capital and energy for another’s advantage, for there is a feeling that no abiding arrangements of a mutual nature can be made with any grower. Mr. Pownall is very vexed with his shipments recently received from Adelaide; some arrived sour, and very many are mousy, and he puts it all down to the extreme poorness of the grapes from which it was made.67

Without agents, Australian producers would have had little alternative but to use the spot market (auctions), where prices rarely covered production costs of cheap, young French wines, let alone one that had been matured a year and a half on the other side of the world. For this particular late nineteenth-century market to work, therefore, trusted agents were required at both ends of the chain: in Australia to check that only acceptable wines were shipped; and in London to determine the appropriate remedies to correct the wines after the journey. One of the first serious attempts at promoting Australian wine in Britain was in 1871 by the author A. C. Kelly, who started selling his wine from the Tintara Vineyard Company (McLaren valley) through an English wine merchant, Peter Burgoyne. The business failed and the company’s assets passed to Thomas Hardy, who retained Burgoyne as his agent for the British market, “thus cementing Burgoyne’s connections with the Australian wine industry.”68 Another early attempt was that of Patrick Auld, who established the Auldana Vineyards at Magill (Adelaide) and a company called Auld, Burton & Company in London in 1871, under the registered name of “The Australian Wine Company.” This too failed, in 1885, and was bought by Walter Pownall, who continued to use the Emu brand.69

By the final decade of the nineteenth century it was these two British companies that controlled Australian wine imports in Britain, and in particular Peter Burgoyne, who claimed in 1900 that over the previous thirty years “fully 70 per cent of the wine exported from Australia to England had passed through his hands.”70 In 1893, as noted above, Burgoyne bought the Mount Ophir vineyard (Victoria), and according to one report in the Wine and Spirit Trade Record of 1912, “the maintenance of the special characteristics of each brand is effected by the careful blending of the produce of various vineyards, according to soil, and variety of grape, whereby their quality is increased.”71 Burgoyne had agents who selected wines in Australia, while in London the firm had around 4,500 hogsheads of wine in bond and a similar quantity at the Pelham Street premises in 1912.72 The newly arrived wines were treated in London:

After the necessary rest . . . the wines are racked bright from the lees, and as a rule receive a preliminary fining. It is from the wines thus treated that the blends are made up. After a rest of three weeks or more in the vats the blends are drawn off into hogsheads and again fined. When absolutely brilliant—that is, after a rest of three or four weeks—the wines are again racked bright off the finings into clean casks. They are then allowed to rest again before bottling. The object of this treatment is to ensure the smallest possible crust or deposit in the bottle.73

The wines were then sold either by the cask unbranded or by the bottle, using the Ophir (Burgoyne) brand. Burgoyne claimed to have invested £300,000 in advertising them in Britain. “Burgoyne’s Australian Wine” placards were found “on every railway station in England,” but he also resorted to other, more ingenious methods to sell his wines. Edmond Mazure, manager of Auldana Vineyard in Adelaide, noted how his clerk picked out the birth notices from the “leading London papers” and sent each mother a bottle of wine with the note that although it was good, “he trusts the lady will not take it until she has consulted her medical adviser.” In the words of Mazure, this achieved “a double advertisement, the first with the recipient, and the other, which is probably even more valuable, with the doctor.”74 Finally, in February 1905, Burgoyne entered the local Australian wholesale and retail trade, establishing an agency for a number of leading European brands of alcohol, selling under Burgoyne’s Own Brand (B.O.B.), and holding large stocks of very fine wines—hocks, ports, sherries, and so on.75

The Australian producers inevitably resented the control exercised by the two British importers and lobbied their state governments to create an alternative marketing system. The South Australian Government Central Wine Depot was originally established in London in 1894 with the objective of providing either a place for growers’ wines to recover before they were sold to their agents or consigned to the depot’s manager, who would find an agent for them.76 Opposition by Burgoyne and the London trade press to the depot was immediate and vitriolic, and it appears to have been boycotted by the London merchants.77 The London correspondent of the Australian Vigneron, a writer close to Burgoyne, published a monthly condemnation of the depot’s activities for Australian readers. In Australia the depot was criticized for losing large amounts of government money, for failing to make wine producers independent of Burgoyne, and for refusing to communicate to British merchants the name of the wine producer or to the producer the name of its customer. The depot was at a major commercial disadvantage because, although wine quality was checked by Perkins in Adelaide before shipping, it was often sent in small parcels, which made it difficult to sell. In addition, the depot was not the legal owner of the wines and thus could not blend them to compete directly with Burgoyne. Instead, and to the annoyance of other London merchants, the manager E. B. Young signed an exclusive agreement with the Blandy Brothers wine firm, who bought the wine to sell under the depot’s Orion brand. By 1900 Young claimed that he had sold South Australian wine to over four thousand customers, “including most of the best wholesale houses in London and the provinces, large wine merchants, and grocers, as well as a number of high-class restaurants and clubs, who are now retailing the depot wines,” and sales had increased from about 1,650 to 4,565 hectoliters between 1896 and 1900. The last figure was just a fifth of what Burgoyne claimed to have handled.78

At the turn of the century the South Australian and Victorian governments both held parliamentary enquiries into the benefits of central wine depots in the organization of the wine trade. Opposition to them came from Burgoyne, who threatened to end buying wines in Australia itself,79 but as the Victorian commissioners noted, there was also a “great conflict of testimony amongst expert witnesses as to the best means for the state to promote the industry.”80 The debate over the best use of public funds led to four very different proposals, of which only one involved a London depot. One alternative was to subsidize a British retail chain to stock and sell Australian wines. In December 1898 the Australian Vigneron reported that Thomas Lipton had offered to open a depot in Melbourne for Victorian wines and to advertise them in Great Britain in exchange for £5,000 for eight years, while a similar offer was apparently received from W. & A. Gilbey.81 Neither was accepted, and in 1911 Burgoyne (2,700,000 liters) and Pownall (750,000) still dominated exports from South Australia and Victoria, but the British retailer Gilbey (625,000) now came a close third.82

Other alternatives included local wineries and state depots located in the major ports to benefit small producers. The problem was one of creating the correct incentives because while many in the industry wanted government funds, it was widely believed that subsidies should be paid only for producing “sound and unadulterated wines” and not “bad wines,” which then had to be distilled.83 Public-funded cooperatives or depots had to be able to reject grapes and wines that were of poor quality, but, as Perkins noted, while it was possible to determine that a wine was “sound and unadulterated,” on “the question of quality none will agree.”84 The fear was that if growers of poor-quality grapes received support, this would lead to an expansion in their production given the ease to plant a vineyard, while there was a “grave danger of the wineries being made repositories for large quantities of wines of inferior quality—in fact a dumping ground for the rubbish left after the sound, marketable article has been disposed of in the ordinary way.”85 Many established producers therefore feared that an ill-conceived state intervention would lead to the growth in output of poor-quality wines, dragging prices down, so the demand for intervention by the small growers came to nothing. In Victoria, many abandoned the sector, especially with phylloxera ravaging in the state, thereby removing large amounts of poor-quality wines from the market. The support for a London depot among the large producers also remained limited, especially as Burgoyne’s threat of abandoning the market would have left producers with the risk of sending their wines to London at their own cost and accepting the market price there.86

The Australian experience was very different from that of Argentina and California because Australia’s domestic market was so small and was heavily fragmented, a result of both distances and internal customs duties before 1901. The last quarter century prior to the First World War saw a major increase in the scale of production of the leading wineries. The specialist skills and equipment required to make dry table wines in hot climates were not profitable in small wineries. By the last decade of the nineteenth century, dry red table wines were being exported to the British market despite the difficulties for a commodity chain that stretched around the world. Strict control was required on the quality of both the wines leaving Australia and those entering the Britain. Attempts at creating public institutions, such as the South Australian Government Depot, broke down, in part because of the opposition of competitors like Burgoyne and Pownall, but also because the semipublic nature of a depot made it difficult to reject poor-quality wines, and management’s lack of experience and capital made it hard to build up stocks and establish new markets.

Export markets demanded large quantities of wines of similar styles, while the domestic market encouraged winemakers to produce brandy and dessert wines. Brandy producers benefited not only from economies of scale in the production, but also from the possibilities of import substitution behind high tariffs and limited competition because of the excise tax. Brandy and dessert wines were also considerably easier to brand than table wines. In this respect, companies such as Seppelt had much in common with the California Wine Association or Gonzalez Byass in that they were able to take advantage of growing economies of scale in production and marketing behind government protection.

1 Laffer (1949:124–25).

2 Kelly (1861:115–20).

3 Cited in Dunstan (1994:26) and Osmond and Anderson (1998:4).

4 Figures for 1910, Year Book 1912, 396–97. When all vines are considered, including grapes for wine, the table, and raisins, South Australia and Victoria both had two-fifths of the total, and New South Wales a sixth.

5 See chapter 1.

6 Busby (1825/1979:xix). Busby described Young as “that acute and accurate observer.” Busby had an estate in the Hunter Valley, although there is no evidence of him visiting it. The contribution of Busby to Australian viticulture is told in Beeston (2001) and Faith (2003). For Young’s failure as a farmer, see Mingay (1975:7–8).

7 From July 1906 it became known as the Wine and Spirit News and Australian Vigneron, claiming that “the policy of this paper is to cater for the needs of the wine-maker and the wine and spirit merchant (Australian and import), and to energetically support the claims of the wine-grower” (255).

8 Faith (2003:26) and Beeston (2001:38).

9 Bouvet and Roberts (2004).

10 Australian Vigneron, February 1891, p. 177.

11 Beeston (2001:128, 130, 133); Bishop (1998:65, 72).

12 Figures from Osmond and Anderson (1998:40). The area of vines includes figures for table grapes and dried fruit.

13 Australian Vigneron, November 1891, p. 137.

14 Ibid., November 1890, p. 116.

15 Faith (2003:54). See also Bishop (1980).

16 Some 900 of them planted less than 4 hectares each of vines (Pope 1971:28, 29).

17 Australian Vigneron, June 1894, p. 38. Critics claimed that the bonus led to the production of poor-quality wines because vines were planted on unsuitable land or unsuitable grape varieties were planted on suitable land, and because of the “ignorant handling in fermentation by unskilled persons who rushed into the business” (ibid., June 1898, p. 21). One established grower complained that “we can thank the Victorian Government for bringing down the price of wine by giving the planting bonus. If it had spent the same amount of money in advertising our wines, we would have done the planting” (Victoria, William O’Brien, 1900:45).

18 Phylloxera’s reappearance in the Rutherford district in the final years of the century brought strong condemnations from growers and led to the sacking of Bragato, the government official in charge.

19 Australian Vigneron, February 1898, p. 155; July 1898, p. 59; and October 1899, p. 117. For the demand for agricultural research in Australia at this time, see especially McLean (1982).

20 Australian Vigneron, February 1901, p. 204.

21 The Viticultural Station at Rutherglen distributed 350 copies each of these first two translations. Other studies translated included Dubois and Wilkinson (1901a), Dubois and Wilkinson (1901b), Gayon (1901), Mazade (1900), and Foex (1902).

22 Australian Vigneron, July 1898, p. 41.

23 Beeston (2001:82); Ward (1864/1980:43).

24 Australian Vigneron, July 1890.

25 Victoria Year Book 1903, 391, and 1914–15, 713.

26 Australian Vigneron, June 1914, p. 293. No dried fruit was produced at Rutherglen. Many of the growers sold their grapes, and the wine was produced by firms such as Burgoyne. In the next three largest areas, average production was, for Ararat, 106 hectoliters; for Stawell, 76.5 hectoliters; and for Shepparton, 56.9 hectoliters. My calculations.

27 Ibid., April 1892, p. 219.

28 This paragraph is based on Whitington (1903). By contrast, Thomas Hardy in Victoria (1900:38) claimed to have 200 hectares of vines, presumably in a variety of different locations purchased grapes from 30–40 part-time growers, equivalent to a further 200–240 hectares.

29 This retreat from wine making by growers was one factor in the decline in support for both the Australian Vigneron in the 1900s and the South Australian Vigneron Association, which by 1911 had a membership of only forty-five. Australian Vigneron, June 1911, p. 241.

30 Cited in Aeuckens (1988:148).

31 Victoria (1900:38).

32 Mills (1908:17).

33 Australian Vigneron, May 1897, p. 11; Bishop (1998:71–72, 79). The journal stated that coolers had been in use “for the past 18 years,” but an earlier article (November 1890, pp.116–17) failed to mention this despite dealing specifically with the problems of controlling temperature during fermentation and the Seppelt winery. Salter could not use the coils until 1895 because of a lack of water (Bishop 1988:79).

34 Bishop 1988:74–75.

35 Australian Vigneron, March 1898, p. 188. The book referred to most probably was Ferrouillat and Charvet, Les celliers (1896).

36 Australian Vigneron, January 1891, pp. 155–56 and March 1902:236 for New South Wales; and Victoria (1900:33).

37 Australian Vigneron January 1899, p. 169. Elsewhere Perkins wrote that “to-day the grower should be wine-maker, his perishable crop should not be under the whip hand of the wine-maker” (Victoria 1900:14).

38 Australian Vigneron, August 1900, pp. 71–73.

39 Perkins, for example, complained in the 1890s that in the old areas of production in South Australia the increase in vines was not always accompanied by a growth in storage capacity. In 1896 over 350 tons of grapes (the crop of 100 hectares) in Tanuda (Barossa) remained unpicked because of the lack of cellar facilities. Ibid., February 1898, p. 162.

40 Cited in ibid., January 1908, p. 27.

41 The company denied growers’ claims that prices had been cut. Prices were fixed each year in accordance with demand and the estimated size of the future harvest.

42 This paragraph is based on reports in Australian Vigneron, April 1904 and February 1909; and the Rutherglen Sun and Chiltern Valley Advertiser, July 9, 1909.

43 Faith (2003:71) notes that the “previous overwhelming influence” of the Burgoyne family had started to decline because Peter Burgoyne’s son Cuthbert mistakenly believed that the future was for light wines, not fortified ports.

44 Bishop (1988:62).

45 Beeston (2001:176).

46 Australian Vigneron, December 1890, p. 151.

47 The figures would be larger if the wine used for brandy production and sold to other states were included.

48 One report talks of a mixture of newly pressed (or partly fermented) grape juice and raw spirits, which, when added with heavy metal contamination contained in the spirit and the presence of undesirable fusel oils, made a concoction that was highly addictive (Bell 1993:151).

49 Adelaide Observer, July 28, 1866, cited in Bell (1993:153).

50 Twopenny (1883/1973:67–68).

51 Victoria Department of Agriculture (1900:8). Thomas Hardy disagreed, arguing that distilling was a response to the demand for alcohol to produce sweet wines. Australian Vigneron, September 1900, p. 101.

52 Victoria (1900:13).

53 Australian Vigneron, September 1893, p. 90. The same article noted the need for an organization that prevented the “placing on the market say 50 or 100 small parcels of wine of various qualities, differing individually more or less each recurring vintage.”

54 Ibid., December 1890, p. 151.

55 The East Torrens Winemaking and Distillation Company, the South Auldana Vineyard Association, and the Tintara Vineyard Company. See below.

56 British imports of Australian wines in 1913 were still equivalent to 20 percent of imports from France or Spain, or 17 percent of those from Portugal (Wilson 1940:362–63).

57 Britain imports between 1893 and 1899 comprised 50.7 percent from South Australia, 46.4 percent from Victoria, and just 2.8 percent from New South Wales (Australian Vigneron, May 1901, p. 21.

58 Ibid., March 1902, p. 236.

59 South Australia claimed that natural wines could contain in excess of 14.8 degrees (Bell 1994:34). Fortifying also occurred in Britain. Thudichum and Dupre (1872:744) wrote that “to many of these wines, which had been carelessly shipped, brandy had been added after their arrival in England.”

60 Ridley’s, May 1907, p. 368. Thomas Hardy noted between 1880 and 1892 that he had shipped “many thousands of gallons of pure natural wines to England,” and only one shipment went above the 26 percent proof limit, requiring him to pay 2s. 6d. duty per gallon instead of 1s (Australian Vigneron, August 1892, p. 69).

61 Australian Vigneron, January 1910, p. 29.

62 The Times, May 24, 1893, cited in ibid. August 1893, p. 74.

63 A hogshead was approximately 275 liters, and 1,000 gallons some 4,546 liters.

64 Australian Vigneron, July 1892, p. 48. E. Burney Young gives these costs as 5s. 6d. per hogshead between Bordeaux and London, and 15–20s. from Australia. Young was not an entirely independent observer, as he would become the manager of the South Australian Government Bonded Depot in London.

65 Ibid., July 1892, p. 47.

66 Ibid., October 2, 1893, p. 114.

67 Ibid., January 1894, pp. 171–72. Penfold & Co. had established an import house in London by the turn of the century. Pall Mall Gazette, December 3, 1893, cited in ibid., March 1903, p. 202.

68 Aeuckens (1988:157). The Emu brand was registered in 1883.

69 The company changed its name to W. W. Pownall in 1895 and remained the second largest exporter of Australian wines before the First World War.

70 Australian Vigneron, September 1900, p. 115.

71 Cited in ibid., May 1912, p. 203.

72 Ibid., May 1912, p. 202.

73 Ibid., May 1912, p. 203.

74 Ibid., December 1900, p. 164, and February 1901, p.72.

75 Ibid., December 1905, p. 344.

76 By contrast, the depot trade with other commodities, such as butter, fruit, and frozen meat, was profitable and uncontroversial.

77 South Australia (1901, no. 24, p. 68, 2297). Thomas Hardy noted that “the large buyers would not touch the depot.” The 1901 Select Committee also questioned whether, if the depot in the future concentrated just on the wholesale trade, this would provoke a boycott by the London merchants (ibid., 54). Burgoyne also had a particularly fiery temper, which led to a number of important and sometimes very public arguments. For his disputes with Dr. Alexander Kelly, see Beeston (2001:75); and with Pr. Perkins of Roseworthy and the winemaker John Christison, see the Australian Vigneron, March and April 1902; February 1903.

78 South Australia (1901, no. 24, p. iii). Burgoyne claimed to have been responsible for 25,000 of the 36,000 hectoliters of Australian wine imports. Australian Vigneron, March 1902, p. 235. The figures shipped under “Government Certificate” from Adelaide were much smaller—2,320 hectoliters in 1899–1900 and 3,860 hectoliters the following year (South Australia. Parliamentary Papers no. 43. 1915:67).

79 As early as 1894 Burgoyne had complained that when his representative was away from Australia for some months, shipments were far from satisfactory as “native wood casks were used by many shippers, and complaint was made of the carelessness in the execution of the orders” (Australian Vigneron, September 1894, p. 83). He repeated these complaints in a letter in March 1903 to Benno Seppelt, which he asked to be read at the Winegrowers Association, stating that after the forthcoming harvest he would end buying wines in Australia itself (ibid., March 1903, pp. 202–3).

80 Victoria (1900:10).

81 Australian Vigneron, October 1896, p. 97; December 1898, p. 150; January 1899, p. 176.

82 Ibid. January 1912, p. 25; February 1912, p. 71. Figures are approximate.

83 South Australia (1901), Perkins, 109, and Paul de Castella, 31.

84 Ibid., Perkins, 109.

85 Victoria (1900), Bragato, 21. Australian Vigneron, March 1898, p. 129.

86 Ibid., March 1896, p. 388; April 1897, p. xvi; and February 1898, p. 167. In South Australia, it was argued that “the half-dozen larger capitalist growers” were “quite independent of any central cellar.”