CHAPTER 9

![]()

Big Business and American Wine:

The California Wine Association

The California Wine Association would “cultivate more vineyard acreage, crush more grapes annually, operate more wineries, make more wine, and have a greater wine storage capacity than any other wine concern in the world.”

—Ernest Peninou and Gail Unzelman, 2000:33

WINE HAS TWO very different histories in the United States. On the East Coast the attempts to plant European vines (Vitis vinifera) failed repeatedly because of the excessively harsh winters for the cold-sensitive European vine or endemic cryptogammic diseases such as downy and powdery mildew, anthracnose, and black rot, which thrived in areas of high humidity, as well as phylloxera.1 From the late eighteenth century a number of new vines appeared east of the Rocky Mountains that were either domestications of native American species (V. labrusca and V. rotundifolia) or naturally occurring hybrids between American and European varieties, such as concord or catawba. These varieties were often resistant to the fungus diseases and could withstand the harsh winters, but they produced a strong, disagreeable, “foxy” flavor in the wine. Some of the labrusca hybrids were also not very resistant to phylloxera. As the grapes were naturally low in sugar and high in acidity, sugar and water were added, and in the second half of the nineteenth century merchants blended these wines with those produced in California.

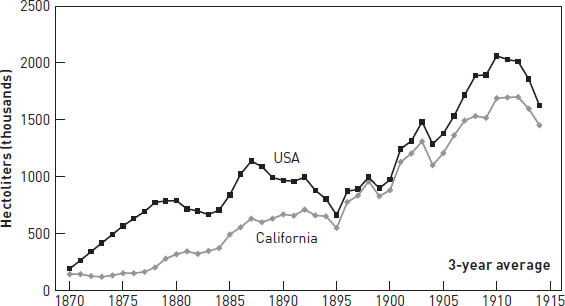

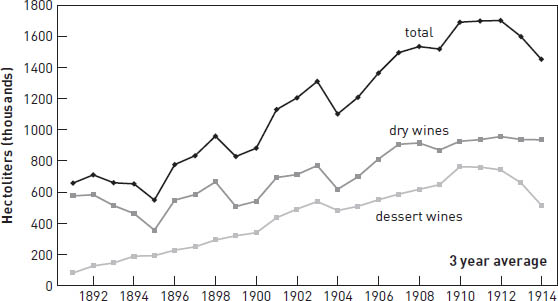

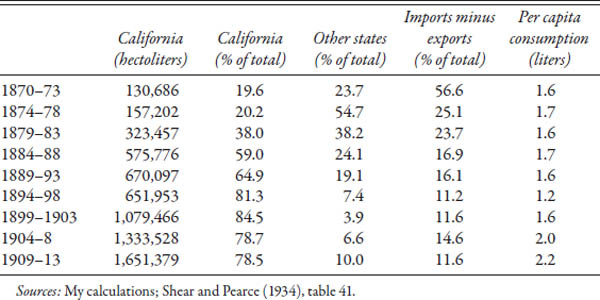

By contrast, by 1901 California accounted for nine-tenths of the nation’s wine production, but had just 2.4 million of its 91.2 million inhabitants. Viticulture was introduced into Baja California by the missions, the first of which was founded in San Diego in 1769, although the earliest reference to the planting of grapes dates from 1779, at the San Juan Capistrano mission.2 After the missions were secularized in 1833, the vineyards were neglected and eventually abandoned. Privately owned vineyards began to appear as early as 1818, but the size of the industry was small as California’s population was just fourteen thousand inhabitants on the eve of the gold rush. By 1852 it had jumped to a quarter of a million. As powdery mildew was devastating Europe’s vineyards, the California Farmer declared in 1855 that “California may become the vineyard of the world,” and the California Horticulture Society noted that the state possessed 10 million acres (approximately 4 million hectares) of potential vineyards, and that the European industry employed directly and indirectly five million people.3 Viticulture grew rapidly, so although the United States imported thirty-eight times more wine than it produced in 1840, the consumption of domestic wines was nearly four times greater than consumption of imports by 1886.4 California wine output quadrupled between 1866–69 and 1883–86, doubling again by 1898–1901, and once more in the following decade (fig. 9.1). On the eve of the First World War, output stood at 2.16 million hectoliters, of which 44 percent was dessert wine (wines that had been fortified with brandy) and 56 percent dry table wines. By 1913 California had 134,000 hectares of grapes, 69,000 of which were for wine, 45,000 for raisins, and 20,000 thousand for table grapes. An estimated 15,000 heads of families were directly engaged in viticulture, with many more being employed in wine making and ancillary industries.5 The United States, or more correctly California, had gone from producing virtually no wine to producing as much as Germany. Technological change was also important, but while California farmers developed new technologies in many branches of agriculture that made them more productive than their European competitors,6 the wine industry remained dependent on French scientific knowledge and equipment before 1914. European contemporaries were astonished not by the rapid growth of the sector or the nature of the technology used, but by the distinct organizational structure of the industry. The creation of a wine trust that controlled the industry was unique and even inspired imitations in the Midi, although these came to nothing.7

Figure 9.1. U.S. and California wine production, 1871–1912. Source: California State Board of Agriculture (1912:191) and Shear and Pearce (1934: tables 6 and 10)

This chapter looks at how the industry developed. The first part shows how producers adapted grape growing and wine making to local conditions; the next considers the relationship between growers, winemakers, and San Francisco’s merchants that led to the creation of the California Wine Association (CWA); and the third part examines the difficulties in selling to consumers accustomed to drinking beer and whisky rather than wine. Despite the success of the CWA, consumption of dry wines was strictly limited outside the small group of immigrants from southern Europe, and it was dessert wines that proved to be the most dynamic sector in the decade or two prior to Prohibition.

CREATING VINEYARDS AND WINERIES IN A LABOR-SCARCE ECONOMY

The initial growth of viticulture was slow, and in 1850 the main center of production was on fertile land around Los Angeles, using the mission grape variety, which was well suited for the production of fortified sweet wines in the hot southern climate, especially when wine-making skills were poor, but not for table wines. The population of Los Angeles as late as 1880 was just 11,183 inhabitants—very small compared with the major market of San Francisco, which saw its population increase from 34,776 to 233,959 between 1850 and 1880.8 Local merchants tried to increase their wine supplies to compete with the expensive European imports. The firm Kohler & Frohling, which dominated the Los Angeles trade at this time, together with two other promoters, established a cooperative at Anaheim, some 32 kilometers south of Los Angeles.9 This allocated fifty plots of 8 hectares to each settler and set aside more land for housing, schools, and other public use. Between 1857 and 1859 the cooperative paid $20,000 for 22,789 days of field work in the preparation of the vineyards, fencing, and digging irrigation ditches. The vine growers were from Germany and were a diverse group, with little or no practical knowledge of grape growing. The cooperative was ended once the vineyards were established, but the colony continued to maintain a strong communal spirit. A further 600 hectares were added in the early 1870s to meet the needs of the growing population, with a large part of the land being planted with vines. Kohler & Frohling purchased most of the wine, and output jumped from 11,000 hectoliters in 1864 to 47,000 in 1884. This was the last good harvest before a mysterious new vine disease, subsequently named Pierce’s disease, destroyed the vines and forced growers to switch to walnuts and oranges instead.10

The rapid growth of San Francisco following the Gold Rush encouraged local merchants to search for wine supplies nearer to the market, with one of the most important ventures being the Italian-Swiss Colony. This was founded by Andrea Sbarboro, a native of Genoa, and originally conceived as a grape-growing cooperative, ostensibly to solve unemployment problems among Italians and Italian-Swiss in the city.11 Sbarboro proposed to pay the workers part of their wages in company shares, thereby making them partners in the project. In 1881 some 600 hectares of land were bought north of Sonoma in a village named after the Piedmont wine town of Asti. The scheme failed as a cooperative because the workers rejected their shares and insisted on receiving full wages, so the business was run instead as a joint stock company, but with a strong paternalistic tendency.12 The Italian-Swiss Colony prospered at wine making and integrated forward into distribution, selling its chianti-type wine under its “Tipo” label in raffia-covered bottles imported from Italy. Pietro Rossi, a Piedmontese chemist, was the driving force behind the colony, and he established one of the first laboratories in California to control wine quality.

There were also a number of very large private estates. Agoston Haraszthy’s Buena Vista vineyard by the early 1860s included over 160 hectares of vines, which Haraszthy believed to be the “largest in the United States” at the time.13 Buena Vista was relatively modest, however, compared to Leland Stanford’s Vina Ranch between Red Bluff and Chico, which had 1,450 hectares of vines by 1887, although all 64,000 hectoliters of wine produced in 1890 had to be distilled because of its poor quality.14 Stanford’s original purpose was to produce a cheap, light, dry wine, but the land was too fertile and climate too hot so instead the ranch specialized in the production of brandy and sweet wines, with the former winning a high reputation.15 Other large vineyards included the Italian Vineyard Company, which had 800 hectares of vines in a single field near Cucamonga in the early 1890s, and the Riverside Vineyard Company, with 1,000 hectares of vines.16

California and other parts of the New World suffered a shortage of both skilled and unskilled labor, and the amount of physical labor required for planting new vineyards, constructing wineries and cellars, and building roads was immense. New investment was poured into the industry at moments of high wine prices, leading to short periods of rapid expansion. For example, between 1877 and 1887 California’s production jumped from 150,000 hectoliters to 579,000, and in Napa alone the number of wineries increased in a decade, from 49 (in 1881) to 166 (in 1891).17 In 1889 Edward Roberts estimated that the five thousand vineyards in California employed some thirty thousand to forty thousand men in “cultivating, picking, storing, pressing, bottling and in otherwise caring for the crop and preparing the wine for the consumers.”18 Until the last decade or so of the nineteenth century, a significant part of this labor force was provided by Chinese.

The Chinese had a reputation as being cheap, hard working, and quick to learn. By the late 1880s they had come to dominate the state’s wine labor market, and both Haraszthy and Stanford used them extensively on their estates. Controversy had surrounded their use from the beginning, but it was widely recognized that some form of cheap labor was required if California was going to develop its huge agricultural potential. However, the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which both restricted the entry of new Chinese and prohibited the naturalization of those that had arrived, together with the growing hostility toward them, effectively ended the flow of new immigrants, and the Chinese population in California dropped from seventy-five thousand in 1880 to forty-six thousand by 1900.19 The problem was especially acute on the large estates: one contemporary suggested that growers were in the same predicament as the cotton planters had been after Civil War and believed that many vineyards would end up being subdivided and worked as small farms.20 By the late 1880s Chinese labor had become scarce and was no longer considered cheap, so growers looked to a new group of immigrants—Italians, who sometimes also brought vine-growing skills with them. Between 1890 and 1910 California’s Italian population quadrupled, from fifteen thousand to over sixty thousand, which also led to an increase in demand for grapes to produce wine.

From the start, California’s vineyards and wineries were designed to save on labor. To facilitate cultivation, vines were often located on valley bottoms and planted in long, straight rows. The rich soils had the advantage of producing higher yields than those on the hillsides, a fact that growers exploited as the price differential between the shy and heavy bearers was not sufficient in most areas to encourage the production of better wines. Vines were extensively planted, with about 2,500 to the hectare, and the two rows of 2.1–2.4 meters each allowed a horse to plow with two or three furrows in both directions. By the end of the century this had changed, so that on most modern vineyards the vines were being planted with one row about 1.8 meters wide and the other diagonal row 3 meters, permitting the use of double plow teams on the wider row.21 The rapidly growing farm-implements business of California led to new specialized equipment being produced for the vine, including gang plows with up to four shares to stir the middle of the row. A variety of methods for training the vines were adopted, but not those that obstructed cultivation, such as were popular in Germany, France, and other countries.22 According to the historian Vincent Carosso, viticulture in California actually used less labor per hectare than many other crops.23 By the turn of the century a single man was able to work a good, well-cultivated vineyard in full production of 8 hectares, with hired labor needed only for the harvest. The winegrower George Husmann wrote in 1883 that wine production was simple: “The very ease of the pursuit, which allowed anyone, even with the simplest culture and the most common treatment, to raise a fair crop and make a drinkable wine, has led many, in fact a large majority, to embark in grape growing who knew but little about it, and did not try to learn more.” Yet he continued by noting that “easy as are grape culture and wine making here, there is a vast field for improvement; and nowhere else perhaps are rational knowledge and proper skills more needed.”24

The first task was to find a more suitable grape variety than the mission, and growers such as Antoine Delmas, Charles Lefranc, and Emile Dresel were instrumental in bringing large quantities of cuttings into the state. The Hungarian immigrant Agoston Haraszthy made a highly publicized visit to Europe in 1861 and claimed to have collected 1,400 different grape varieties—perhaps 300 was more likely—and he also had 100,000 cuttings and rooted vines sent to his Buena Vista vineyard and winery at Sonoma.25 Any growers’ resistance to change in the old vineyards was ended with the spread of phylloxera, which destroyed large numbers of mission vines that otherwise might have remained in production. According to Haraszthy’s son Arpad, the mission variety declined from about 80 percent of California’s vine stock in 1880 to 10 percent a decade later, when an estimated 90 percent of the state’s wine grapes were of “the best foreign varieties.”26 However, the transformation had only just begun. Professor (later Dean) Eugene W. Hilgard of the University of California’s College of Agriculture noted in 1884 that “among the most important and at the same time most difficult questions still to be settled for California viticulture, is the special adaptation of grape-varieties to local climates and soils, and to desirable blends; and before these points are settled, many heavy losses and disappointments will be sustained.”27 Economic incentives, as elsewhere, generally encouraged growers to plant heavy bearers rather than those appropriate for fine wines.

California may have had one or two of the world’s largest vineyards, but these were exceptions. Just as in Europe, the vast majority belonged to small, family farmers, and originally many dedicated part of their land and labor to other activities.28 In 1888 George Husmann noted:

We have thousands, perhaps the large majority of our wine growers . . . who are comparatively poor men, many of whom have to plant their vineyards, nay, even clear the land for them with their own hands, make their first wine in a wooden shanty with a rough lever press, and work their way up by slow degrees to that competence which they hope to gain by the sweat of their brow. Of these, many bring but a scanty knowledge to their task.29

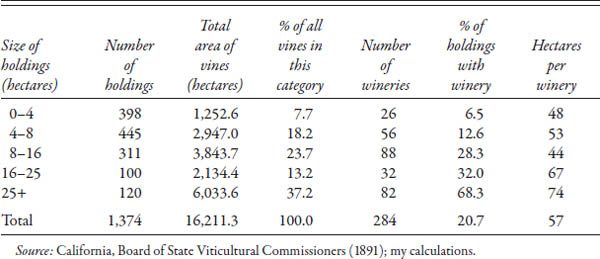

In 1889 there were an estimated 65,000 hectares of vines and 5,000 growers producing grapes for both wine and the table, giving an average holding of 13 hectares.30 When those used for wine production alone are considered, the 1891 survey shows that there were approximately 2,750 growers with more than 2 hectares (5 acres) of vines covering an area of 35,000 hectares.31 For Napa and Sonoma, which at this time accounted for 46 percent of the area of California’s vines destined for wine production, the average holding was 12 hectares, slightly less than the state average. In these two counties there were 531 holdings larger than 8 hectares, but these accounted for three-quarters of all vines, and the largest 220, with more than 16 hectares, occupied half the vineyard area (table 9.1). In total there were 41 vineyards with more than 50 hectares (125 acres), representing a fifth of the total area, and 85 percent of them had their own wineries.32 At the other extreme, 61 percent of holdings accounted for 26 percent of the vines, but only 1 in 10 had their own wineries. If growers with less than 2 hectares were included, the extremes in property ownership would be even greater. In Sonoma, for example, there were 9,068 hectares of vineyards cultivated in 815 holdings of over 2 hectares, but these statistics exclude “at least five hundred acres of small vineyards of less than five acres (two hectares), planted for family use.”33

TABLE 9.1

Vineyards and Wineries in Napa and Sonoma Counties, 1891

The advantages of the family grape-producing farm, namely, low monitoring and supervision costs associated with labor and the absence of incentives for land abuse, were offset by their lack of scale in wine production and their weakness in marketing the wine. When production was just for local consumption, these problems were unimportant for family growers. However, the rapid growth in California’s wine production after 1880 was not based on the expansion of rural, local markets but was linked to urban demand, both in San Francisco and in distant markets such as New York, Chicago, and New Orleans. The distinct economic advantages offered by small, family grape producers in association with large-scale wine making facilities were appreciated by Percy T. Morgan of the California Wine Association, who, while noting in 1902 that merchants were organizing “great vineyard companies with ample capital for the laying out and planting of vast tracts of wine grapes,” added that “it is not from these great tracts that the larger portion of the tonnage for wine purposes will be derived. It is from the small vineyardist, cultivating from ten to fifty acres (four to twenty hectares); cultivating and looking after his lands individually, and thereby obtaining from 30% to 50% more tonnage to the acre than is possible from the great vineyard tracts, that the very remunerative results will accrue.”34

If grape growing in a hot climate was easier than in cooler regions such as Champagne and Burgundy, wine making presented more problems. The first obstacle in California was the lack of practical knowledge shown, for example, by the fact that because most Europeans and “all Germans,” picked their grapes as late as possible, many Californian winemakers initially did the same. Late picking maximizes the grape’s sugar content, an important consideration in northern Europe, but hardly a problem in Southern California, or indeed anywhere else in the state. Instead growers in hot climates needed to pick early to conserve the grapes’ acidity, which helped preserve the wine, as well as learn not to mix ripe with unripe grapes, to exclude moldy or rotten grapes, to choose a vessel with adequate size for fermentation, to clean and disinfect all the utensils, and so on.

The early 1880s saw a rapid increase in the construction of commercial wineries using labor-saving designs. They were cut deep into the hillsides, and grapes were taken by horses and wagons to the top floor for crushing. Where this was not possible, grapes were moved to the top floor by an elevator. Once the grapes were crushed, the juice fell by gravity to the fermenting vats on the floor below and finally to the bottom of the winery to mature. Hand pumps were labor-intensive, and winemakers started investing large sums at the turn of the century to introduce gasoline and then electricity generators. Pumping was crucial, not just to move wine from one barrel to another, but also to provide the cool water needed to reduce the temperature of the fermenting must.35

The development of viticulture in the cooler coastal regions around San Francisco made it much easier, at least in theory, to produce dry table wines. Indeed, as the hot and dry summers allowed the grapes to mature sufficiently, winemaking was easier than in Missouri and the eastern states, or in central and northern Europe. George Husmann’s wines produced on the Talcoa Vineyard in Napa were fully fermented after six days and cleared enough to be sold to merchants six weeks later for maturing; they were then shipped “as far East as Connecticut, when not more than a year old, and arrive in perfect condition.”36 Yet many winegrowers were not so successful. Eugene Hilgard, in a famous article in the San Francisco Examiner of August 8, 1889, blamed the serious overproduction at that time on the poor quality of wines being produced. According to Hilgard, the reasons for the poor wines included (1) the wrong choice of grape varieties; (2) growers cultivating too large an area so that grapes were not harvested at the correct moment; (3) grapes not properly sorted prior to crushing; (4) fermentation tanks that were kept too full so that there was no room for a protective cover of carbon dioxide; (5) the use of excessively large fermentation tanks and hot grapes; and (6) improper handling of the fermentation and subsequent activities.37 The solution for Hilgard was the development of scientific wine making, and this could only be achieved through the construction of large industrial wineries.

Charles Wetmore, a leading member of the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners, strongly disagreed with Hilgard on the need for larger wineries and in particular the separation of grape-growing activities from wine production. He believed that small wineries could produce fine wines, and that if growers stopped making their own wines, their economic incentives would be to use grape varieties that maximized output rather than quality.38 Other writers, such as Husmann and Bioletti, also insisted that fine wines were best made in smaller cellars, “under the constant, watchful supervision of the proprietor, who must himself be an expert connoisseur in wines and must know just how to handle the product at every stage during, as well as after, its manufacture.”39 However, these fine wines accounted for perhaps only 5 percent of the state’s production, and there is no doubt that by the turn of the twentieth century, when skilled enologists and laboratories in wineries were very scarce and market demand was for cheap dry and dessert wines, these were most economically made in large, modern wineries.40

Change happened fast. The 1891 survey reports over six hundred wineries, but Edward Adams wrote a few years later that there were only between two hundred and three hundred winemakers that were “equipped with the plant necessary to produce good wine on any commercial scale.”41 The Census of Manufactures gives a lower-bound estimate of the factory share of the value of wine output as just 13 percent in 1880, but this rises rapidly to 38 percent in 1890 and 78 percent by 1900.42 The Pacific Wine and Spirits Review also noted that while previously nearly every vineyard had had its own fermenting house and storage cellar, by 1900 most growers sold their grapes to winemakers, “except to a limited extent in some of the older districts.”43

PRODUCTION INSTABILITY AND THE CREATION OF THE

CALIFORNIA WINE ASSOCIATION

There were five major players in the California wine trade in the late nineteenth century: grape producers; winemakers; San Francisco shippers; the East Coast bottlers and distributors; and consumers, who were themselves deeply divided between those who drank alcohol and those who were temperate. The development of new markets after 1880 created incentives to expand production, but new coordination arrangements were required between the different links in the commodity chain if an adequate return on the high levels of capital investment now required was to be achieved. In particular, commercial growers needed a market for their grapes; winemakers required both a supply of grapes, to benefit from the potential economies of scale associated with the new wine-making equipment, and a ready market for the wine; and local merchants found it necessary to maintain their competitive position and block out East Coast merchants dealing directly with local producers. While some of these problems were not dissimilar to those found in Europe at this time, they were solved in very different ways. The weak bargaining power of small growers in the California wine industry made it impossible to obtain concessions from government to create new institutions such as those found in France. By contrast, the favorable business climate for large enterprises led to the creation of a trust that integrated both horizontally and vertically, from the production of grapes through to the distribution of wines.

The California wine industry switched from boom to bust on a number of occasions. After a period of rapid growth, which saw the area of vines increasing by 50 percent between 1873 and 1876, the industry plunged into depression because of the difficulties associated with marketing outside California.44 In Napa, savings banks refused to make loans on vineyard property as they considered that vines did not increase the land’s value, and elsewhere farm animals were allowed to wander in the vineyards before the vines were pulled up and sold for firewood.45 The recession was ended by phylloxera in France, which led to a sharp increase in wine prices, and prosperity was reinforced by higher tariffs in 1874 and then again in 1883. Imports fell from 372,000 hectoliters in 1873 to 129,000 in 1885.46 Between 1877 and 1887 the area of vines in Sonoma Country increased from 2,800 to 8,780 hectares, while in Napa the increase was from 1,360 to 5,840 hectares. For Eugene Hilgard, writing in 1884, only the appearance of phylloxera in California itself and the impact of the Exclusion Act were obstacles to future growth.47 The boom lasted until 1886, when a large, inferior crop caused prices to collapse, but harvests continued to grow because of the excessive plantings in the early 1880s.48 The wine crisis resulting from the panic of 1886 continued well into the 1890s as the economy suffered the severe downturn of 1893.

The wine crisis of the decade from 1886 to 1895 was typical of those affecting the New World in this period, and not dissimilar to the mévente of the Midi in the 1900s. As supply exceeded demand in the major markets, merchants cut back on their wine purchases, so winemakers required fewer grapes. Although wine production had undoubtedly improved in California, a significant amount of cheap and adulterated wines were sold in the major markets, and the price differential between quality and quantity wines was reduced. Charles Wetmore noted in 1894 that “the man who gets ten tons of grapes to the acre gets 10 cents for wine; the man, who on a steep hillside, gets two tons and a half, gets 12 cents; and the 12-cent wine is mixed with the 10-cent.” Some growers responded to low prices by grafting high-yield, low-quality varieties to their better vines, while others carried out only the minimum operations necessary, leading to disease running “unchecked in vineyards.” Over 12,000 hectares of vines were uprooted in the early 1890s.49 Yet as George Husmann noted in the 1896 edition of his book, the asset-specific nature of wine-making installations made wine owners even more vulnerable to downturns: “It was very clear to them that their immense storage houses, casks and machinery, and all the capital it had cost to build up their trade, would be wholly unremunerative if the vineyards died out, and they would be in worse plight than the producers, who had at least their lands, to cultivate in some other crops.”50

California’s wine crisis of the early 1890s affected both growers and winemakers, with adulterated wines driving down the price of genuine ones. The large number of growers that had no wine-making facilities (around four-fifths in 1891) were particularly vulnerable, and the Pacific Rural Press in 1894 claimed they depended on “three or four firms of San Francisco” for their livelihood. This grower’s newspaper argued that a large percentage of the fifty million dollars invested in the wine industry belonged to the growers and producers, so the merchants’ offer of five or six cents per gallon after the 1893 harvest gave a return on capital of just 2.5 percent, leaving growers nothing for labor and expenses.” Despite these low prices, the newspaper claimed there was “no overproduction of wine in this State, unless it be in the ‘brick vineyards’ of San Francisco.”51

To resolve the problems of poor quality and artificial wines, Professor Hilgard in 1889, along with others, proposed district cooperatives for labeling, bottling, and marketing wine and criticized the winemakers and merchants for emphasis on “pretty bottles and beautiful labels” rather than attempting to improve quality. As the established banks refused to lend on wine, an attempt was made to create a grape growers’ and wine merchants’ bank, but this failed because of its inability to secure financing, and the growing distrust between the two sides of the industry.52

A combine was proposed that would allow both growers and winemakers to pool their production and give them absolute control over the wine making and marketing. The original idea was for a growers’ contract lasting several years, with prices increasing over time, but with the contracts only becoming binding when 75 percent of the total acreage of wine grapes had been secured.53 Several hundred of the largest producers signed up, including Pietro Rossi and Andrea Sbarboro of the Italian-Swiss Colony, and the California Wine-Makers Corporation (CWMC) was established in 1894. Within a few months the price of ordinary wine increased from 6 cents to 12½ cents per gallon, in part because the CWMC was allowed good credit facilities, and in part because of the small harvest of 1894.54 To sell the wine, the CWMC entered into a five year agreement with the California Wine Association, an organization also created in 1894 by the leading West Coast wine dealers (see below). Postcontractual opportunistic behavior quickly appeared when harvests recovered and lower prices followed. By the summer of 1897 a “wine war” had broken out between the two rival organizations, caused by the CWA’s refusal to pay the prices demanded by the CWMC, and the CWMC, in violation of the contract, selling a million gallons (3.8 million liters) of wine and an option on another 1.5 million gallons directly to the New York house of A. Marshall & Co., thereby allowing a powerful East coast merchant direct access to producers.55 Although the CWMC controlled perhaps 80 percent of the state’s wine producers by 1897, the CWA had 80 percent of the wine produced,56 and the legal defeat for failing to honor the initial agreement saw the CWMC effectively disappear in 1899.57 Almost immediately Henry J. Crocker, ex-president of the CWMC, attempted to start a new organization. He circulated over 1,400 letters to the state’s grape growers in which he offered contracts for seven years and demanded a minimum of 80 percent of the state’s wine grapes.58 The Pacific Rural Press noted that these grape prices could be achieved only if merchants paid artificially high prices for their wine, and that, with the exception of raisins, no other combine had been able to attract 80 percent of the crop.59 Crocker’s project failed because of the diversity of the growers’ interests. One difficulty was that of assessing grape quality, especially as many of the smaller producers were beginning to plant shy-bearing European varieties on the hills, which produced small quantities of quality wine rather than the heavy bearers found on the plains. Another problem was that any organization that monopolized grape production would naturally want to use the best wine-making facilities available, and those small growers that already possessed older wine-making facilities feared that their investment would become worthless if these facilities were no longer used and they ceased to be winemakers.60 Higher grape prices would also encourage new plantations and therefore depress future wine prices.61 Finally, many growers without wine-making facilities resented being locked into long-term contracts, especially as they were benefiting from the competition from three major buyers: the CWA, Lachman & Jacobi, and the Italian-Swiss Company.62

The possibility for growers to have wineries competing for their grapes proved short-lived, however, as the CWA took control of half of both Lachman & Jacobi and the Italian-Swiss Company.63 Yet there were limits to how far the CWA could dictate grape prices to the growers, as Percy Morgan noted in a letter to the company’s stockholders in 1903:

The policy of your management is to encourage Grape Growers to feel that they have a friend and partner in the Wine Merchant who is willing to share with them whatever prosperity the business affords. With this view prices were paid for grapes during the vintage which caused the largest part of the profit which has hitherto been derived from wine making to inure to the growers. This policy should meet the approval of all well-wishers of the industry, for unless grape growing is remunerative the business would languish and there would be no incentive to plant the new acreage necessary to off-set the damage by phylloxera and to supply the increasing demand for Dry Wines.64

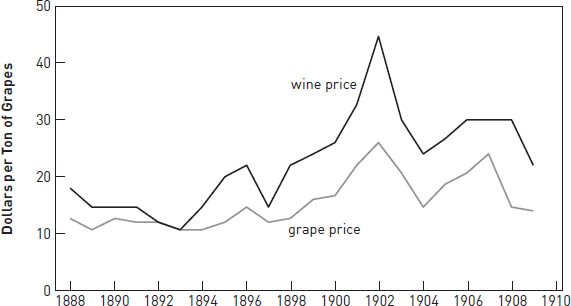

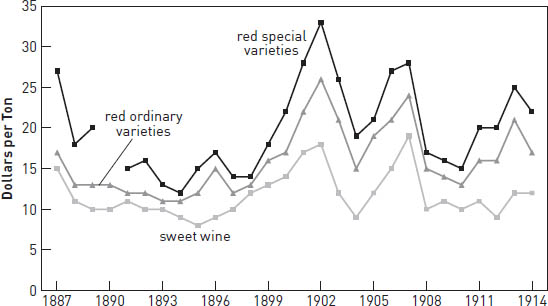

The increase in production and wine prices in real terms from the late nineteenth century suggests that CWA successfully regulated the sector, especially as other fruit farmers in California were experiencing a decline in prices at this time.65 Furthermore, the fact that grape prices in general moved in line with both dry and dessert wine prices suggests the grape growers also shared that prosperity (figs. 9.2 and 9.3). Although no information is available on how many grapes the wineries outsourced, the CWA owned over 3,000 hectares, or less than 5 percent of California’s wine grape acreage, but was responsible for 84 percent of wine output.66

Figure 9.2. California grape prices and wine prices (equivalent per ton of grapes), 1888–1907. Source: Shear and Pearce (1934: table 26). The authors note that the “data are based on somewhat fragmentary and, at times, conflicting trade quotations.” The wine price has been converted into an equivalent per ton of grapes.

THE CALIFORNIA WINE ASSOCIATION AND THE MARKET FOR CALIFORNIA’S WINES

In January 1904 Percy T. Morgan noted that the “quality and general excellence” of California’s wines were “no longer in question,” but that per capita wine consumption in the United States was less than a fiftieth of that in “wine drinking countries like France and Italy.” He claimed that “almost every rolling hill and fertile valley of California could be profitably covered with vines,” so that the future of the industry was “principally, if not entirely, dependent upon an expanding market.”67 Morgan did not have to worry about foreign competition, as the rapid growth in the California wine industry between the late 1870s and 1880s had taken place against a background of wine shortages in France because of phylloxera and high U.S. import duties on foreign wines in 1874 and again in 1883. Exports of French wines to the United States declined from 236,000 hectoliters in 1873 to 23,000 in 1889, while California’s production increased from 95,000 to 587,000 hectoliters, and out-of-state exports rose from 19,000 to 310,000 hectoliters, between the two dates.68 As Carlo Cipolla noted, the character of the wine industry changed dramatically, from selling two-thirds of California wine production in the state at the end of the 1870s to only 10 percent by the end of the 1890s.69 In about three decades California increased its output tenfold, and its share of U.S. wine consumption rose from one-fifth to four-fifths (table 9.2).

Figure 9.3. California prices for dry red and dessert wines, 1891–1913. Source: Shear and Pearce (1934: table 25)

For contemporaries, a major restriction to the growth of the industry was adulteration and fraud, and in 1906, despite the supremacy of the state’s wines in the national market, California growers and merchants complained that their best wines were sold under foreign labels and their poorer ones, together with those from every other wine-producing state in the country, under the California brand.70 The motives, as one writer at the end of the century noted, were obvious: “A bottle of wine, which as domestic, could be sold at a good profit for fifty cents, with no extra expense except the affixing of a new label, may bring, as imported, a dollar and a half, and the customer be just as well pleased and as well served. Labels of all known brands, with imitations of special corks, bottles, or other peculiarities, are kept constantly in stock in all cities, at trifling cost, to be used for this purpose.”71 Adulteration was also the consequence of poor wine-making techniques, and in California as elsewhere, some producers turned to chemists not just to improve wine quality, but to cover their errors.72 Complaints of adulteration and the fraudulent use of the “California brand” inevitably coincided with the low wine prices and glutted markets such as the late 1880s and early 1890s, but the nature of market demand led to very different solutions in California from those in Europe. The problems associated with wine adulteration were solved by three interconnected strategies: horizontal consolidation and vertical integration; the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906; and the tax reform for brandy in 1891.

TABLE 9.2

Origin of Wines Consumed in the United States

Agoston Haraszthy as early as 1862 had proposed that the California wine industry fund an agent in San Francisco to organize the sale of the state’s wines and vouch for their authenticity.73 In 1872 a joint-stock association, the Napa Valley Wine Company, was formed to promote the region’s wine in eastern cities.74 In San Francisco itself the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners sponsored in 1888 a permanent exhibition that allowed consumers to purchase locally branded wines.

However, it was a private initiative that led to the California Wine Association being created in August 1894 when seven of the state’s largest wine firms formed a trust with a capital stock of $10 million.75 All assets of these seven wine houses were turned over to the CWA, although wine would still be sold under some of their labels and trademarks. In 1900 the CWA acquired half interests in the three largest independent wine houses still remaining and continued to buy up other wineries. It recovered quickly from its considerable losses in the San Francisco fire of 1906, and in the same year work started on a huge wine complex called Winehaven on a 19-hectare site at Richmond, which had storage for some 378,500 hectoliters, or about 25 percent of California’s output, and wine-manufacturing facilities for 140,000 hectoliters.76 This was an experiment in horizontal consolidation and vertical integration—from grape growing to distribution—on a massive scale.

A major objective of the CWA was to improve wine quality, and in 1896 Husmann claimed that there had been rapid advances, in part because of the planting of better grape varieties in adequate locations, but also because wine making was being conducted more scientifically.77 In that year Bioletti argued that the high temperatures found during fermentation explained “nine tenths of the trouble to which our wines are subject.”78 Wineries were quickly modernized, and Lachman noted in 1903 that “in the last eight years rapid progress has been made in the manufacture and maturing of wines, wine making having been conducted on more scientific lines,” and the Pacific Wine and Spirit Review (hereafter PWSR) also noted the improvements in wine quality with the separation of wine making from grape production.79 Neither comment is completely objective, as Lachman was a CWA director and its chief taster and the PWSR was also dependent on the same organization, but it has been said that the CWA never produced a bad wine, or an outstanding one.80

Although vertical integration helped the CWA to control the quality of its own wines, large quantities of California wines were still reportedly being sold under foreign labels. In addition, poor-quality wines of dubious origin, such as those that the PSWR dubbed as being manufactured chemically in Ohio’s “brick vineyards,” were sold as originating from California, thereby damaging the state’s reputation. The CWA particularly welcomed the Federal Pure Food and Drugs Act because previous regulations had covered only interstate trade, and it had been possible to legally ship a barrel labeled “poison” between two states and then sell it as wine if the destination state had not passed its own pure food law.81

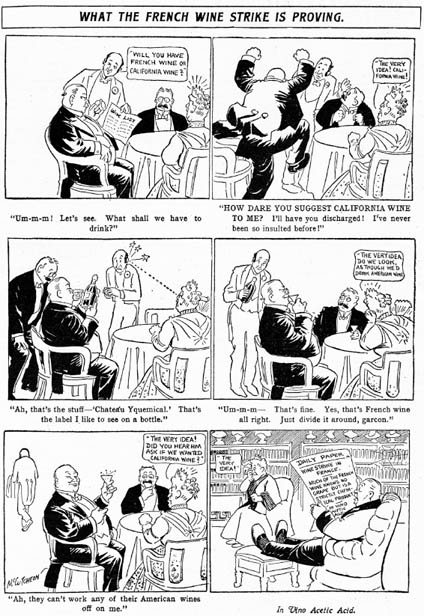

However, as in other wine regions, what was considered fraud and what legitimate was often very parochial, and in the same issue that PWSR criticized the brick vineyards, highly favorable comments were made concerning the “more than 2,000,000 bottles of genuine champagne” annually produced in the United States.82 California wines that were described as a particular French type, such as “Burgundy” or “Champagne,” were also rejected for the Paris Exposition of 1900. A couple of months later the same journal reproduced a cartoon (fig. 9.4) from the Chicago Tribune that neatly combines both the East Coast prejudice against genuine fine California wines and the widespread adulteration of French wines and the Midi protests, which was widely reported in the international press during that year.83

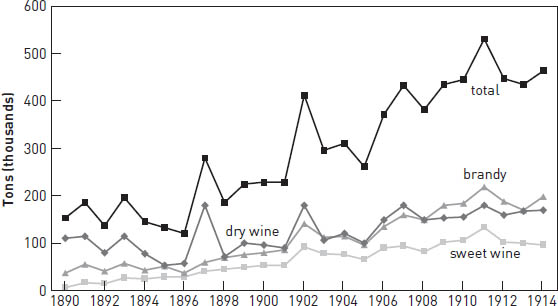

The third major factor in improving quality was legislation that allowed California’s winemakers to fortify their wines with domestic grape brandy and not pay the $1.10 a gallon tax on brandy. This made dessert wine the cheapest form of alcohol on the market and allowed producers to profitably distil their unstable wines and produce sweet fortified wines.84 It also implied that they did not have to resolve the technical problems associated with making wines in a hot climate and therefore was especially attractive to producers in the Central Valley. California’s total wine production increased by a factor of four between 1891–93 and 1911–14, but for dry wines the increase was just a third compared with dessert wines, which saw their production multiply ninefold (fig. 9.5). Fortified wines kept longer when open, deteriorated less through transportation, and were easier to brand because quality could be kept constant from one year to the next, all factors that encouraged the CWA to increase their production. By 1913 dessert wines accounted for 45 percent of all California’s production, of which 46 percent was classified as port, 31 percent as sherry, 12 percent as muscatel, and 9 percent as angelica, a wine named after Los Angeles.85 There was also a major growth in the production of brandy, and the economies of scale found in both dessert wine production and distilling86 and the legal requirements of having to have an excise officer present at all times benefited a large producer such as the CWA. On the eve of the First World War brandy production used 40.8 percent of wine grapes, compared with 35.5 percent for dry wines and 23.7 percent for dessert wines (fig. 9.6).87

During its first decade, the CWA distributed wines in bulk to wholesalers, but Morgan talked of a change in company strategy in 1905 when he informed stockholders that he wanted to create brands of bottled wines and advertise them “in the hope of educating the public to a greater appreciation of the excellence of the better varieties of Californian wines.”88 A decade later, in 1917, he wrote:

Figure 9.4. Cartoon, “What the French Wine Strike Is Proving,” Pacific Wine and Spirit, July 1907, p. 14. Attributed to Chicago Tribune, June 12, 1907. Courtesy of Special Collections, University of California Library, Davis.

Figure 9.5. California production of dry and dessert wines, 1891–1913. Source: Shear and Pearce (1934: table 10)

Until the coming of the California Wine Association only a few wineries tried to deliver their original packages direct to the consumer and build up a following for their label. The large dealers almost always sold California wines in bulk to distant jobbers who either bottled them with a domestic or foreign label known in their particular localities, or sold them to retailers who pursued a similar course. Moreover, these distributors and retailers had neither the knowledge not the facilities to age and handle wines properly. Only a large firm with capital could select from millions of gallons, blend to standards, market under labels that could gain the confidence of the public, and stand back of the label wherever sold.89

A number of reasons can be cited for why horizontal consolidation and vertical integration on this massive scale were chosen as a means of controlling quality in the U.S. market. In the first instance, the distance between California and its major markets (New York, New Orleans, and Chicago) was significant. It could be argued that the Midi or Algerian producers also faced problems of distance in France when they sold their wines in Paris and the industrial North, but in this case they were selling to consumers already accustomed to wine drinking. California, by contrast, had to create new markets, so the comparison should be with selling French or Spanish wine to the reluctant wine drinkers in London rather than Paris. A second point was the limited political voice of the sector, and in particular of the growers. A final one is the heavy capital investment and asset-specific nature of this technology that led to wine production being just one of many sectors that participated in the “great merger movement.” According to Naomi Lamoreaux, consolidations became common to escape price competition, especially in capital-intensive, mass- production industries where no single firm had a clear-cut advantage, and where expansion had been rapid in the years leading up to the depression of 1893.90 This description matched clearly that of the California wine industry at this time. Most of the large, capital-intensive wineries had been constructed only a few years earlier, and the possibilities of collusion in the wine market were very difficult. One important consideration in the case of the CWA was the need to establish its own distribution networks. Although information for the United States is limited, retail wine prices fell much less in the major centers of consumption, such as Paris or Buenos Aires, than in areas of wine production.91 By integrating forward and controlling distribution, winemakers could both obtain higher prices and guarantee a market for their wines. This helped provide the market stability for the group to invest in brand names.

Figure 9.6. Grapes used in wine and brandy production. Source: Shear and Pearce (1934: table 42)

Finally the improvement in the reputation of California wines also allowed a few independent wineries to begin to specialize in fine wines for niche markets, with the smaller Napa wineries such as Inglenook, Charles Krug, Beringer, and Salmina (Larkmead) consistently taking awards and bottling their best wines with labels displaying “Napa” as their appellation.92 By 1901 the Pacific Rural Press claimed that fine wines accounted for 5–10 percent of the state’s output.93

Wine was a small player in the U.S. alcohol industry, and while over the half century prior to the First World War annual per capita consumption increased from 1.2 to 2.2 liters, beer consumption jumped from 20.1 to 79.2 liters, although spirits fell from 9.5 to 5.7 liters. Beer consumption increased not just because prices remained stable, but also because quality improved significantly as the average size of breweries increased twenty-four-fold between 1873 and 1914.94 The success of the California wine industry was limited, and at the very best wine consumption in the state increased from around 20–25 liters per capita in the 1880s and 1890s to 36 liters in the mid-1900s, a figure that was little more than half the 60 liters found in Argentina or Chile.95 However, the industry made major strides in improving both quality and market organization. At the College of Agriculture the work of individuals such as Eugene Hilgard and Frederic Bioletti was important to help growers tackle phylloxera and improve wine making. By 1914, California was part of the international scientific network that included research institutes in the Midi, Algeria, and Australia. The difficulties associated with making dry wine in hot countries were only beginning to be resolved on the eve of the First World War, but by this date a winery with adequate facilities and the correct expertise was able to produce an acceptable vin ordinaire. Prohibition ended much of this research, and the considerable human capital that had accumulated in the state’s vineyards and wineries over the previous quarter century was lost, contributing to the delay, not just in California but in the New World in general, in the development of suitable wines for the European markets.96

What made California very different from other wine regions in this period, however, was the consolidation of the leading firms to create the CWA, and the degree of vertical integration of wine making and distribution that occurred. This allowed the CWA to sell branded wines in bottles directly to retailers and guarantee their purity. The fact that these were ordinary table or dessert wines rather than fine wines increased, rather than diminished the achievement. However, while the CWA appears to have had considerable success in producing a drinkable wine to sell among consumers who had originated from Europe’s wine-producing regions it was less successful in creating new markets, especially outside the major centers of New York, Chicago, and New Orleans. There is little doubt that the CWA used its market power to fix grape and wine prices, but the rapid growth in the industry between 1894 and 1914 also suggests that all sectors of the industry benefited to some degree. The CWA brought greater stability to the market, and California probably suffered less during the turbulent 1900s than any other-wine growing region in the world, with the years of greatest difficulties being in the late 1880s and early 1890s, immediately prior to the founding of the CWA.97

Growers had limited political voice to influence legislation as their French counterparts did, but the CWA could manipulate prices which would have been unacceptable in countries where wine was an important item of popular consumption, such as Argentina. The industry benefited significantly from the high import tariffs and the elimination of the excise tax used to fortify domestic wines, which allowed a rapid growth in dessert wines and brandy, two commodities that were well suited to the company’s large-scale industrial wineries. Unfortunately, while wine was of only modest importance to the U.S. economy, the same was not true for the alcohol industry as a whole. The latter was opposed by an increasing number of citizens, who succeeded in getting Prohibition approved by the federal government. Prohibition became effective in January 1920 and lasted until it was repealed in 1933. According to the wine historian Thomas Pinney, “even though the industry was not absolutely finished off, it was seriously diminished, obstructed, and distorted.”98 However, Prohibition made the sale of alcohol illegal, not its manufacture or consumption. Between 1920 and 1933 the area of vines actually doubled, and while some of the grapes were used for the table, to make fresh grape juice and raisins, a considerable, but an unknown quantity was turned into wine in private homes. The demands of home producers led to growers grafting their vines with varieties that produced poorer wines, but that had grapes with thicker skins that could withstand better transportation.99 One estimate by the Wickersham Commission suggested that 4.2 million hectoliters of wine were produced annually between 1922 and 1929, slightly more than double what had been commercially produced in the final year be-fore Prohibition.100 Warburton, by contrast, believed that consumption of all wines—sacramental, medicinal, and homemade—increased by 65 percent between 1911–14 and 1927–30, while beer consumption declined by 70 percent and spirits rose by 10 percent. Wine consumption increased more because it was the easiest form of alcohol to produce at home.101 For the CWA, however, Prohibition made redundant its vast network of wineries and cellars, while scientific progress was halted as early as 1916 when the Regents of the University of California prohibited research on alcoholic fermentation and all applied research in wine and wine grapes.102

Californians had to relearn their wine after the end of Prohibition in 1933. Large areas of premium grape varieties had been either uprooted or grafted with poor-quality heavy bearers to produce table grapes. Wines were made by untrained winemakers in unsanitary conditions, leading W. V. Cruess to note that “after Repeal, the outstanding characteristic of our wines was instability.”103 The challenges following repeal were not dissimilar to those facing the industry in the 1880s, and it is fascinating to see how differently the sector responded. The University of California provided important scientific work, but a significant part of this research was directed toward understanding basic viticulture and viniculture practices associated with producing fine wines, rather than helping those producing for the initially vastly more important market for ordinary table and dessert wines. Local growers’ associations such as the Napa Valley Wine Technical Group helped information circulate. It was the fine wine producers that first used varietal and geographical labeling to separate their better-quality products from the rest of the industry that still used European place names (“California claret,” etc.). The CWA was not re-created, but the problems of having to vertically coordinate grape growing, wine making, and marketing remained. Instead of a highly integrated Californian firm that dominated the national wine market, out-of-state bottlers and distilleries moved into the area in early 1940s to purchase local wine-making businesses to guarantee supplies for the East Coast as the industry changed from the producer of “a bulk commodity” to a business that was “predominantly brand oriented.”104 Finally, winemakers succeeded in educating their drinkers, and in the words of James Lapsley, between the 1930s and 1980s “the public’s expectation of ‘wine’ shifted from a fortified, often oxidized or spoilt beverage, produced from indistinct grape varieties, to a table wine possessing distinct flavor attributes derived from varietal grapes and from processing.”105

1 Amerine (1981:1–3), on which this paragraph is based.

2 Pinney (1989:238) believes that viticulture probably was not practiced before this date.

3 Leggett (1941:68); Pinney (1989:262).

4 Peninou, Unzelman, and Anderson (1998:255–56); Crampton (1888:184).

5 California Board of State Viticultural Commissioners (1914:2, 4).

6 For the rapid development of technology and market organization in California, see especially Morilla Critz, Olmstead, and Rhode (1999).

7 See chapter 3.

8 Carter et al. (2006, 1:110).

9 Kohler & Frohling already bought the produce of some 142 hectares of vineyards each year. Pinney (1989:254–56); Carosso (1951).

10 Carosso (1951:60–67); Pinney (1989), pp.285–94.

11 Palmer (1965:251–75).

12 Pinney (1989:328).

13 Ibid., 277. It failed financially after it was turned into a joint-stock company.

14 Ibid., 321–25.

15 Husmann (1899:561). The Vina Ranch became part of the endowment of Stanford University and was eventually sold and the vines uprooted.

16 Husmann (1903:417).

17 Heintz (1977:16, 18).

18 Roberts (1889), cited in Heintz (1977:36).

19 Heintz (1977:50).

20 Hilgard (1884:5).

21 Husmann (1896:194). See also Charles Krug in California Board of State Viticultural Commissioners (1888:45).

22 Husmann (1896:219).

23 Carosso (1951:19).

24 Husmann (1883:iv).

25 Pinney (1989:279). The vineyard failed because the vines were too close, the attempts at producing sparkling wines were unsuccessful, and phylloxera destroyed many vines (Amerine 1981:9). Agoston Haraszthy was proclaimed by the state the “father” of California viticulture in 1946, but Thomas Pinney, among others, has challenged some of his supposed successes, showing that he was not the first to bring superior grape varieties to California—Jean Louis Vignes and Kohler & Frohling had already played an important role in this—or to have introduced the zinfandel grape (Pinney 1989:263, 184; Sullivan 2003, esp. chap. 6).

26 Haraszthy, cited in Carosso (1951:132).

27 Hilgard (1884:3).

28 Pinney (1989:337).

29 Husmann (1888:iii).

30 Roberts (1889:199). The figure includes vines for table grapes and raisin. Sullivan (1998) gives a figure of 36,500 hectares for vines at this time.

31 California Board of State Viticultural Commissioners (1891). My calculations. The figures are clearly approximate, as the size of many vineyards is rounded to 10, 15, 20 acres, etc. In addition, there are few vineyards that specifically state that they had young vines not yet in production (these are excluded from table 9.1). Some growers also switched between producing grapes for the table and grapes for wine, according to market prices.

32 Tulveay Vineyard is excluded as no information is provided concerning whether it had wine-making facilities.

33 De Turk (1890:45).

34 Morgan (1902:95), which reproduces an earlier article in the Sacramento Bee. Morgan probably exaggerates the competiveness of the small farm, not just because his organization would benefit most from an increase in the supply of grapes, but also because the political support of grape producers, numerically by far the largest sector of the industry, helped justify the CWA’s demands for high tariffs and federal legislation to control adulteration and fraud.

35 The Inglenook winery is an example of the first type, and Eshcol winery of the second. Both buildings still stand today. Heintz (1999:102, 211).

36 Husmann (1883:284).

37 Cited in Amerine (1981:11–12). See also Husmann (1883:288) for a similar list of complaints.

38 Wetmore (1885:27). The Board of State Viticultural Commissioners and the University of California clashed over resources and research priorities frequently during the 1880s (Carosso 1951:141–43; Pinney 1989, chap. 13).

39 Husmann (1899:559).

40 Bioletti (1909:384).

41 Adams (1899:520).

42 Olmstead and Rhode (2010:280).

43 Pacific Wine & Spirits Review, December 1906, p. 43.

44 Carosso (1951:74, 95).

45 H. W. Crabb, quoted in Husmann (1883:171); and Hilgard (1884:1).

46 California State Board of Agricultural (1912:199).

47 Hilgard (1884:4–5).

48 Carosso (1951:134).

49 Wetmore (1894), cited in Pinney (1989:355–56).

50 Husmann (1896:260).

51 Pacific Rural Press, June 9, 1894, p. 438.

52 Carosso (1951:136–37).

53 The price of grapes and wine was expected to increase by 80–100 percent, depending on the grape variety and whether production was in the plain or hills. See Pacific Rural Press, July 28, 1894, p. 50; June 23, 1894, p. 406.

54 Ibid., March 30, 1895, p. 199. The newspaper noted in May 1895 (p. 324):

the first pro rate distribution for the deliveries during the month of April has just been made, and makes our wine makers feel once more that they are not owned, body and soul, by a few wholesale dealers, who paid about what they pleased to those who were in sore need of money, and ruined the prices outside, but cutting each other’s throats, regardless of what became of the ‘goose that laid the golden egg.’

The 1895 harvest was also small, “but the quality of the product was the best for many years.” Ibid., October 26, 1895, p. 271. See also Adams (1899:517–24).

55 The response of the CWA was to reduce its own wine prices, with the object of discouraging Marshall and other eastern dealers from competing directly with the large California wine houses (Pacific Rural Press, June 5, 1897, p. 353).

56 Peninou and Unzelman (2000:79).

57 The CWMC was required to pay $101,000 to the CWA, although the final settlement was $8,000 (Pacific Rural Press, May 13, 1899, p. 289). Sales of wine and other assets continued for several years.

58 Ibid., July 8, 1899, p. 30.

59 Ibid., August 12, 1899, p. 111; August 19, 1899, p.114.

60 Crocker assured producers that the grapes would be sent to the nearest winery. Ibid., August 19, 1899, p. 114.

61 This problem is discussed in chapter 11.

62 Ibid., August 18, 1900, p.102.

63 Peninou (2000:82, 89). In 1911 the Italian-Swiss Colony had an annual output of 225,000 hectoliters from eight different wineries.

64 February 26, 1903, letter to stockholders (CWA minutes, vol. 2, February 26, 1903:240).

65 Olmstead and Rhode (2010:285) note that rising wine prices would be incompatible with “persistent overproduction.” For other fruit prices, see Rhode (1995:780–84).

66 Peninou (2000:125, 134). It is not clear whether the CWA acreage includes that of other companies associated with it, such as the Italian-Swiss Colony.

67 Morgan (1904:36).

68 Cipolla (1975: 299) for French imports. Calculations refer to wine imports in casks; for California wine production and for out-of-state sales, Pacific Rural Press (April 21, 1900:246).

69 Cipolla (1975:303).

70 The Pacific Wine & Spirits Review (December 1906:20), writes

Heretofore the greater part of California’s best wines have gone to the Eastern markets in bulk and they have been sold to hotels, cafes and high-class bars, only to appear under French labels, while the commoner wines have gone into consumption as the products of California. . . . In other words . . . if California wines of the higher class had not largely masqueraded under foreign labels, the industry would have had a far greater development.

71 Adams (1899:519).

72 The commissioner of agriculture in 1887, noted that wine adulteration “has increased in amount and in the skillfulness of its practitioners until at the present day it requires for its detection all the knowledge and resources which chemical science can bring to bear upon it, and even then a large part doubtless escapes detection.” Crampton (1888:207).

73 Haraszthy (1862:xxi), cited in Carosso (1951:54).

74 Carosso (1951:93); Heintz (1999:97–98).

75 Carpy & Co., Kohler & Van Bergen, Dreyfus & Co., Kohler & Frohling, Lachmann Co., Napa Valley Wine Co., and Arpad Haraszthy & Co. Haraszthy withdrew shortly afterward.

76 Peninou and Unzelman (2000:104).

77 Husmann (1896:258).

78 Bioletti (1896:39). See also Hilgard (1886).

79 Lachman (1903:25); PWSR (December 1906:43).

80 Amerine and Singleton (1977:286).

81 PWSR (May 1907:14).

82 Ibid., 39. My emphasis.

83 Ibid. (July 1907:14).

84 Seff and Cooney (1984:418).

85 Angelica was fortified grape juice rather than a wine. Calculated from California State Agricultural Society (1915:140).

86 See Amerine and Singleton (1977:171).

87 Period refers to 1909–13. Shear and Pearce (1934, table 42).

88 CWA minutes, vol. 2, February 26, 1903, p. 265.

89 Percy Morgan (1917), cited in Peninou and Unzelman (2000:125). See also p. 94.

90 Lamoreaux (1985:45, 87).

91 For Buenos Aires, see table 11.7.

92 Lapsley (1996:67–68); Heintz (1990)

93 Pacific Rural Press (December 14, 1901:372).

94 Shear and Pearce (1934, table 2); Siebel and Schwarz (1933:78).

95 The figure for 1878–82 was 24 liters, and for 1888–92, 22 liters. My calculations, from Cipolla (1975, table 2) for 1907; and PWSR, January 1909, p. 6, for 1906–1908. However, this source includes wines that were exported out of state by rail but not boat. The 36 liters also includes those wines used for distilling for brandy.

96 Grapes continued to be produced for grape juice, raisin, and table grapes, but different varieties were used.

97 The CWA failured to buy grapes in 1908 because of the drop in demand because of Prohibition.

98 Pinney (2005:11). It was repealed in part because of the need to increase taxes and create employment.

99 This was not new, as Arpad Haraszthy noted in 1888 that “considerable quantities of wines” were made in San Francisco by the Italian, French, Spanish, and Portuguese population. These were for home consumption, or sold in a “small way to their neighbours and friends.” California Board of State Viticultural Commissioners (1888:13).

100 The figures are 111 and 55 million gallons, cited in Pinney (2005:20).

101 Warburton (1932:260); Mendelson (2009:50–51). Mendelson argues that illegal producers were more attracted to spirits because of the high ratio of alcohol to volume.

102 Lapsley (1996:47).

103 Creuss (1937:12), cited in Lapsley (1996:51).

104 Lapsley (1996:95, 110)..

105 Ibid., 1.