CHAPTER 8

![]()

From Sherry to Spanish White

Sherry is a foreign wine, made and drunk by foreigners; nor do the generality of Spaniards like its strong flavour, and still less its high price, although some now affect its use, because its great vogue in England, it argues civilisation to adopt it.

—Richard Ford, 1846/1970:177

SHERRY IS A NAME GIVEN to a wide variety of wine types produced in the geographical region around the Bay of Cadiz, including Jerez de la Frontera, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, and El Puerto de Santa María, although for brevity the region is referred to here as Jerez.1 Exports to the British market grew rapidly from the late 1820s to a peak in 1873 at about 30 million liters and accounted for 37 percent of the wine drunk in that market. Sales then declined even more rapidly and were no greater in the early 1890s than they had been seventy years earlier. This chapter shows the nature and limits of organizational change in the production and sale of sherry over the century. Despite an apparent flexibility in responding to increased demand in international markets, the rapid drop in sales was caused by the decline in the reputation of sherry, as merchants in Jerez and especially Britain sold adulterated and cheap imitation wines. Although there was much talk about protecting the name of sherry in Jerez, this proved difficult because of the diversity of interests within the producing region itself. The big export houses responded to weaker demand for their fine sherries by moving down-market to achieve volume, and they were better able to weather the economic difficulties and appearance of phylloxera than either the growers or the traditional winemakers. While the political influence of small growers in France allowed them to capture market power from the merchants by establishing regional appellations and cooperatives, this did not happen in Jerez. Instead the large shippers consolidated their economic power and maintained the right to export whatever wines they wished as “sherry,” arguing that as the British government was unwilling to recognize sherry as being exclusive to Jerez, they had to compete with producers of “sherries” from countries such as South Africa.

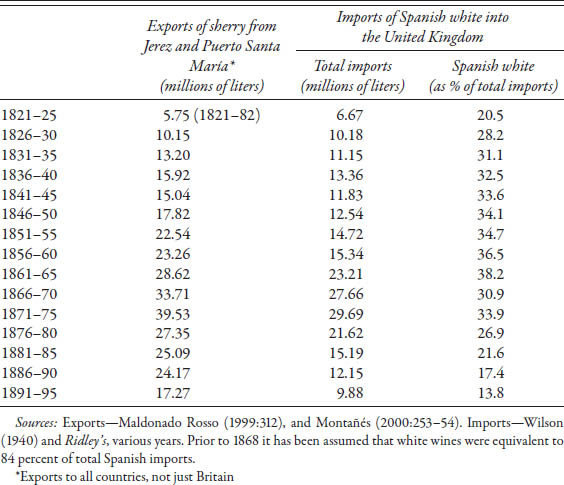

TABLE 8.1

Trade in Sherry and Spanish White Wine

THE ORGANIZATION OF WINE PRODUCTION IN JEREZ

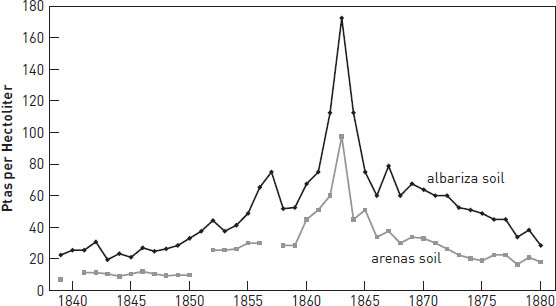

Richard Ford perhaps exaggerated the contribution of foreigners to sherry production but not the importance of the British market, which accounted for 87 percent of all exports at the height of the region’s prosperity in the early 1860s.2 A study in the 1880s estimated that more than half the region’s wines were exported, and this would include virtually all the fine sherry.3 There are few figures for production for the nineteenth century, but movements in exports (table 8.1) and prices (fig. 8.1) show the general trends. Exports to all markets rose from an annual average of less than 10 million liters in the 1820s to almost 40 million in the early 1870s, and the price of must in Jerez tripled between 1850–53 and 1860–63. In 1863 Thomas G. Shaw calculated the value of sherry imports to Britain at ten million pounds,4 and Spanish trade statistics suggest that sherry accounted for an eighth of all exports in the late 1860s.5 Prices from the late 1860s then declined rapidly, and sherry began to lose market share in Britain after 1873, especially to French wines.

Figure 8.1. Price of must in Jerez, 1840–1880. Source: Gonzalez y Álvarez (1878:39–55)

Although both port and sherry producers depended heavily on the British market, there were important differences in the organizational structure and distribution of market power along the two commodity chains. The Jerez wine trade was much older, with sack being popular in Britain from in the sixteenth century if not before, although by the second half of the eighteenth century wine imports were small.6 At this time the sherry trade was limited to two types of young wines: those shipped while still on their lees in October or November, and those shipped after they had been racked in March and April. In both cases the wines were blended with older and stronger wines or strengthened with wine spirit.7 Institutional arrangements reflect this trade in young wines. The Gremio de Vinatería de Jerez fixed annual prices for grapes and must, allowed growers with over 10 aranzadas (4.5 hectares) of vines the possibility to establish retail premises for the local sale of their wines, and restricted the sale of wines produced outside the region.8 Local growers could not be merchants, and the storing of wines by merchants was prohibited. The growth in British demand (and perhaps the development of the solera, a new wine-producing technique), encouraged John Haurie and a group of growers and exporters to successfully challenge several of the guild’s privileges and led to important organizational changes in the industry from the last third of the eighteenth century.9 Large city bodegas (cellars) were built to store and mature wines. By the mid-nineteenth century there were three very different groups involved in the sherry trade: the cosecheros (responsible for growing and crushing the grapes); the almacenistas (for the fermenting and maturing of wines); and the extractores (for exporting). Vertical integration of the different activities into a single enterprise remained limited.10 While brokers (corredores or encomenderos) in the eighteenth century linked sellers in Jerez with foreign buyers, it was the sherry firms themselves who established exclusive contracts with agents in the British market in the nineteenth century. These agents acted as wholesale merchants, selling to local retailers who often sold sherry under their own names (brands). As the distance between agent and exporter was considerable—a letter between London and Jerez took sixteen to twenty days in the 1830s11—agency agreements were carefully crafted and sometimes led to formal partnerships or even intermarriage. Robert Blake Byass, the London agent of the company Gonzalez, Dubosc & Co., became a partner in 1855, and the company was changed to Gonzalez Byass some years later. A granddaughter of the firm’s founder, Manolo González, married one of Alfred Gilbey’s sons in the 1870s, and two of Gilbey’s granddaughters would marry González boys in the 1920s.12

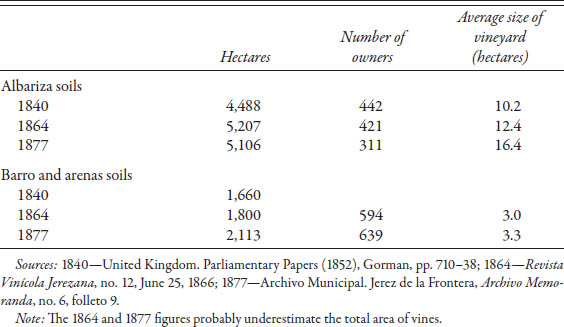

Grapes were grown on three major soil types. The best was the albarizas, a brilliant white, chalky soil, which had an excellent capacity for storing the winter rains. According to one nineteenth-century expert, Parada y Barreto, the wines produced on this soil were “fine, clean and strong, but of scarce production.”13 On the barros or clay soils, the yields were twice as much, but quality was less and labor inputs were greater because weeds grew in profusion. Finally, the arenas or sandy soils had good yields and were easy to cultivate but produced the poorest wines.14 A detailed survey at the beginning of the nineteenth century lists forty-three different varieties of grapes to be found in the Sanlúcar–Jerez region, but even at this early date a handful of varieties predominated. The palomino or listan, a white grape, was found on about 50 percent of the albarizas soil, and the perruno on another 20 percent, and sixty years later Parada y Barreto noted an even greater concentration of the palomino.15 By the 1840s there were perhaps 6,000 hectares of vines in Jerez, and this would increase by at least a third over the next quarter century before stabilizing at about 8,500 hectares.16 This growth in the area of vines was much less than the increase in wine exports. Part of the difference was made up by drawing on stocks of old wines or employing more labor in the vineyard to increase yields, but in particular there was a significant increase in the use of wines produced outside the Jerez region, either for blending with local wines or for exporting directly as “sherry.”17

As in other wine regions, there were many small plots of vines, and on the arenas and barros soils six hundred growers had an average of 3 hectares (6.8 aranzadas) each in the mid-1860s. Larger holdings that required wage labor were more common on the better albarizas soil, and as early as 1840 some 85 percent of vines were found on holdings of between 4.5 and 45 hectares, with four holdings even larger. At the other extreme 40 percent of the growers (171) owned less than 4.5 hectares, each worked predominantly by family labor, although these accounted for only 11 percent of the albarizas vines (table 8.2).

In the first half of the nineteenth century the grapes were crushed and fermented on the farm, but by the second half burned sulfur was used to impregnate the grapes so they could be brought to Jerez for crushing.18 The wine was usually racked off the lees between January and March and fortified with 12–36 liters of alcohol per butt (equivalent to 2–6 percent of the volume).19 Tales of travelers drinking perfectly good unfortified wines from the region were no doubt sometimes true, but, as with all wines, production conditions could vary significantly from one year to the next. Sherry requires a minimum strength of 15.5 percent alcohol for its proper development, and this strength was not achieved if weather was unfavorable at the time of the vintage or if there was an incomplete fermentation.20 After racking, the wine was kept for several years in contact with the air. The high alcohol content and the special conditions found in the sherry bodegas produces a film made up of microorganisms living on the surface of the wine (the flor), which protects it from acetification and allows the wine to develop its distinctive flavor.21 Adding alcohol, often in greater quantities than that noted above, also allowed shippers to export younger wines, which helped undermine the product’s reputation.

TABLE 8.2

Distribution of Holdings in Jerez de la Frontera

The exact nature of the trade in old sherries is difficult to establish. Price lists indicate that sherry was sold on occasion by the vintage and estate in the first half of the nineteenth century, but this became increasingly rare as the century progressed.22 In fact, even the so-called vintage sherries probably contained wines produced from different years. The inability of winemakers to control sufficiently the chemical changes that took place during fermentation using traditional, unscientific methods led to an “enormous variety” of sherries being produced.23 Chance could result in two butts producing very different types of wine despite having come from the same vineyard, been pressed together, and subsequently been stored side by side. It also implied significant annual variations: a butt of must laid down each year on one of William and Humbert’s vineyards between 1933 and 1936 produced the following wines: an amontillado, a fino viejo, a palo cortado, and an oloroso.24 Consequently, unblended sherry could not be finally characterized until it was three or four years old, when it was divided into two main groups: finos (including finos, manzanilla, and amontillados) and olorosos (including palos cortados, olorosos, and rayas). Sweet wines, pedro ximenez and moscatel, were also produced locally. While this allowed producers the possibility to develop wines for different drinking occasions, it created considerable confusion for foreign consumers: “The public knows so much now of vintages and growths of Champagnes, Ports, Clarets, and to a lesser degree of Burgundies and Hocks. . . . With Sherry the case is different, and the consumer knows nothing but vague names such as Vino de Pasto, Amontillado, Oloroso, etc; the result is that he has less means of judging what price he ought to pay.”25

The fact that sherry is a mixture of wines of different vintages makes it difficult to date accurately the shift from exporting young wines to older ones. Thus in 1833 James Busby noted that “the higher qualities of sherry are made up of wine the bulk of which is from three to five years old, and this is also mixed in various proportions with older wines,” although he also noted that cheaper sherries were being exported after only two years.26 The solera system was gradually developed from the very late eighteenth century through to the mid-nineteenth century and consisted of wines of a similar type, but at different stages of development, stored in rows of large casks. As Busby noted, “what is withdrawn from the oldest and finest casks is made up from the cask which approach them nearest in age and quality, and these are again replenished from the next in age and quality to them. Thus, a cask of wine, said to be fifty years old, may contain a portion of the vintages of thirty or forty seasons.”27 If only small quantities of wine were removed, the new wine assumed the characteristics of the older one in a few months. Initially the solera did not significantly reduce the skills or capital requirements, as fine sherries entered the solera only after four years.28 However, soleras were also developed for producing cheap, young wines. The solera system was crucial as it reduced storage costs associated with maturing the wine and allowed exporters to sell wines with the same characteristics year after year regardless of the nature of the harvest, which was essential if brand names were to be created. It was also particularly useful for production of the lighter sherries, the finos.

In the first half of the nineteenth century there had been a strong preference in England for wines that were heavy and sweet to be drunk after meals, such as port, madeira, malaga, and sherry. Around the middle of the century there was a drift toward lighter, drier wines, often consumed as an aperitif or with meals.29 This change in fashion is impossible to quantify, but it did not go unnoticed by contemporaries. Denman, writing in 1876, noted that the

general public taste has so manifestly altered that the wine trade is being revolutionised. The strong old Sherries and Ports of the past are gradually being supplemented by lighter qualities, which our fathers would scarcely have recognised as wines. Instead of strong draughts derived from added alcohol, and cloying sweetness from added saccharum, persons are looking for wine flavour, and bouquet and cleanness upon the palate.30

Although storing the wine for a long time could produce excellent finos, it required a considerable outlay of capital. The solera system, on the other hand, produced an equally acceptable drink after only a few years, and the slow decline in the importance of the almacenista can be attributed to both the growth of the solera system and the switch in demand for younger, lighter wines.

A few export houses dominated the trade. Between 1852 and 1865, for example, the houses of Garvey, Domecq, and González (Byass) accounted for a third of all exports from Jerez, and the leading five houses rarely exported less than half of all the sherry. Although at times there were suspicions of collusion between the largest firms,31 the fragmentation of business in England and the low entry costs to exporting implied that shippers were required to compete on price and provide a wide range of different-quality sherries to their foreign agents. However, while the dozen or so leading houses could not stop other individuals from shipping wines, these often lacked adequate trade connections in the British market to distribute their wines.

SHERRY AND THE BRITISH MARKET

As sherry and port accounted for approximately three quarters of British imports in the 1850s, wine merchants naturally looked first to these regions for sources of cheap wines after the reduction in import duties in the early 1860s. Ridley’s thought that “with regard to white wines suitable for British requirements, we have at present seen nothing capable of competing successfully against Sherry: French productions, except at very high rates, are for the most part of a very indifferent quality, and, unless fortified up to 30 per cent, will not be safe as regards keeping properties.”32

Sherry sales increased, and the price of must in Jerez tripled between 1850–53 and 1860–63 (fig. 8.1). This was not caused so much by structural problems associated with normal supplies being inadequate for the increased British demand, as Sir James Tennent and others had feared, but rather by the short-term effects of vine disease (powdery mildew) and drought. Between 1853 and 1856 harvests fell from about 60,000 or 70,000 butts, valued at £7 each, to 18,000 or 20,000 butts, which were sold for £16–£20 each, even though quality was poor.33 This temporary sharp drop in the supply of fine sherry led to high wages and considerable prosperity in Jerez for those with wine stocks. It did not last, and prices fell quickly after 1863, when the postoidium wines became sufficiently mature to export.

Jerez was traditionally a high-cost wine-producing region because of low yields, high labor requirements, and taxation.34 After 1860 the shippers therefore looked for supplies of cheaper wines elsewhere, a process helped by the opening of new railways, and especially the direct link between Madrid and Jerez, which was completed in 1866.35 The transport costs between the white wine–producing region of Montilla in Córdoba and Jerez, for example, were cut from £8 to £2 per barrel, encouraging the exporter Gonzalez Byass to established wine-making facilities in that city.36 Established shippers increased volume and looked to reap economies of scale by supplying cheap wine because, as one newspaper noted, it was irrelevant to the exporter if “he buys at four and sells at six, than if he makes the purchase at eight and realises it at ten.”37 Some of these inferior wines were mixed with sherry, but others were exported after only a few months through Jerez’s commercial networks. Ridley’s responded to this change by adding prices for a sixth wine to its list—“Sound Cadiz White Wine”—which sold at £14–£16, compared with the five traditional qualities of sherry, which ranged from £22 to £250 a butt.38

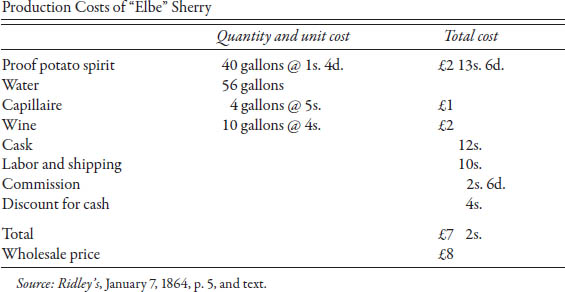

TABLE 8.3

Production Costs of “Elbe” Sherry

Jerez producers were not the only ones who supplied imitation sherries, and in 1863 a group of twenty-nine Jerez shippers gave Ridley’s a gift of £100 for “discovering, exposing, and frustrating traffic in spurious Wines”—wine that had been shipped from London to Cadiz and returned as “Sherry.”39 The British retailer Gilbey’s was one of the first to import “sherry” from South Africa shortly after the Crimean War, which until 1860 benefited from colonial preference.40 Australia, likewise, began producing an imitation. However, the product that did the most harm was Hamburg “sherry,” which was manufactured from cheap industrial alcohol produced from sugar beet or potatoes and, according to the Medical Times and Gazette was “in its original state, . . . a light German wine of poor quality, not possessing in that condition sufficient preserving powers to render it suitable for shipment, or, indeed, for consumption as a natural wine in its own country.”41 An attempt was made to overcome these defects by adding spirit and saccharine. One recipe for “Elbe” sherry is given in table 8.3, and, as the author noted, the return of capital of around 13 percent could be considerably increased if more water, and less wine, was added.

Although from 1865 this type of wine was prohibited from entering Britain for reasons of public health, it is clear that similar wines were being sold.42 Indeed, Gilbey’s, which in 1875 was responsible for 5 percent of all wine sold in Great Britain, dropped “Castle Hambro Sherries” from its lists only in 1877.43 As one senior partner noted, “for some years past we felt that we could not give that assurance of their genuiness as wine as we wished to do, and we decided some years ago not to ship them. In fact, we thought that they rather interfered with the status of our business generally.”44 The reputation of sherry had been damaged much earlier, as Thomas G. Shaw observed in his important book in 1863: “Sherry has long been the favourite wine, but the quantity of bad quality now shipped and sold under its name has already injured its reputation; while the high prices of any that is good and old offer an opening for the introduction of another white kind.”45

One of the reasons why adulteration was relatively easy was the high alcoholic content of sherry. From the late 1870s wine shortages caused by phylloxera in France encouraged sherry exporters to use the cheaper industrial alcohol to fortify their less expensive wines to remain competitive. The extent to which these were prejudicial to health is difficult to assess, but the public concern hastened the decline in popularity of the drink.46 By contrast, the better sherries, when properly matured, required less alcohol than those that were exported after only a few months.

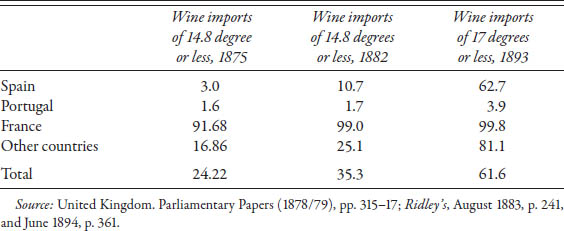

In Jerez the shippers explained the decline in British imports after 1873 to the higher duty that their wines had to pay because of their greater strength compared with French wines, and they launched a major publicity campaign to reduce them.47 Not all were convinced in Britain, and it was argued that a reduction in duty from half a crown to a shilling a gallon would have only a marginal impact on retail prices and might not even be passed on to the consumer.48 Duty on imported wines was finally cut in 1886, when the shilling duty was extended to wines of between 14.8 and 17 degrees. As table 8.4 shows, by the early 1890s almost two-thirds of Spanish wines paid the lower duty, although red wines, mainly from Tarragona, now accounted for 70 percent of total exports. The fact that sherry exports did not recover with the lower duties after 1886 can be explained once more in part by adulteration, with producers illegally using German spirits and salicylic acid as preservatives in their attempts to reduce the alcoholic content of the cheaper sherries so as to enter the lower tax bracket.49 Although perhaps the quantities adulterated were small, it reinforced once more in the public mind the notion that cheap sherries were dangerous.

TABLE 8.4

Alcoholic Strength of UK Wine Imports, 1856–1893 (percent)

The widespread concerns about adulteration also threatened the reputation of fine sherry. The Times in 1873 carried a letter from a Dr. Thudichum that drew attention to the supposed health hazards caused by the addition of gypsum in the crushing of the grapes and sulfur in the fumigation of the casks, activities that were common everywhere in Jerez. Thudichum’s claims were

disseminated throughout the length and breadth of the land by a local Press ever hungry for copy and not too careful either as to its accuracy or the mischief that would naturally accrue from its publication. Thus it has happened that, outside the Trade Papers themselves, little or nothing has been published to disabuse the public mind of the wrong impressions under which it labours as to the supposed unwholesome character of Sherry.50

Six years later Robert Houldsworth, a partner of Gonzalez Byass, complained that doctors, “a very powerful section of the community,” “have been running down sherry lately.”51 The asymmetries of information, where the buyer has insufficient knowledge of the quality of a product prior to purchase, were now accompanied by supposedly informed advisors arguing against drinking even fine sherry bought from reputable merchants, and this situation was ended only when the Lancet vindicated the drink in a report published twenty years later.52 This failure to adapt to the more impersonal markets of the late nineteenth century and the inability of the legislation in Britain to reduce the threat of adulteration suggest the need for a closer look at the shippers’ interests in Jerez, and the difficulties in developing self-enforcement mechanisms to control quality.

PRODUCT INNOVATION AND COST CONTROL

The independence of the almacenistas, who bought young wines from growers to mature in their cellars for future use in blending, was eroded even before the fall in prices after 1863, as the large shippers integrated backward and purchased their businesses to guarantee stocks of fine wines.53 Those almacenistas that remained independent found a much more competitive market after 1863, in part because of their overvalued stocks bought at the height of the boom, but also because of the spread of the solera system, which shortened the maturing time required for wine production. Exporters, by contrast, were able to limit the effects of lower prices by selling large volumes of cheap, young wines, often without their brands. These were brought directly from growers and the shippers prepared them in their cellars, without the need for the almacenistas.54 The widespread publicity given to the annual shipping lists, which ranked shippers according to the volume of exports regardless of the quality of the wine, provided an additional incentive for them to move down-market. Under pressure from the London wine trade, the publication of these lists was ended in 1878.55

The solera system allowed wine quality to remain constant from one year to the next, which facilitated the development of brands. Gonzalez Byass, for example, had a number of old soleras, such as Matusalén, Apóstoles, or Tio Pepe, expensive wines that sold in the late 1870s for five shillings or more a bottle, about five times the price of “cheap” sherries.56 Harvey’s famous Bristol Cream dates from about the same time,57 while Berry Brothers listed William and Humbert’s Dry Sack at four shillings a bottle in 1909, equivalent to the price for a bottle of Scotch whisky.58 The relatively high price of these sherries saw them being sold through traditional distributional channels of specialist wine merchants rather than by grocers who owned an off-license. They were for immediate drinking as, unlike port, sherry does not improve once in the bottle. Genuine sherry was simply too expensive to brand for the mass market, and in any case many British retailers preferred to sell their own brands. Trade was “hand-to-mouth,” with retailers keeping low stocks and then ordering small lots of highly specific wines directly from the Jerez shippers.59

The decline of sales in the British market after 1873 was partly offset by rising French demand for cheap wines because of phylloxera, and between 1886 and 1892 France imported about 110,000 hectoliters of sherry and white wines a year compared with Britain’s 140,000 hectoliters. Total exports therefore remained strong until the late 1880s, but the growth in demand of cheap, young sherries was accompanied by a major decline in the quantity of mature wine to be found in Jerez, and by 1895 it was estimated that there were no more than 8,000 butts of wine older than thirty years in “the whole district.” This switch to young wines also affected relative grape prices, and in 1882 it was noted that “prices for new wines from the best soils have declined, whereas wines from inferior soils have fetched fair prices.”

The large sherry houses not only benefited from the growth in French demand, but also looked to develop new markets. Around 1872 the firm Santarelli Hermanos began to sell bottled sherry in Spain,60 and markets were found especially in Madrid and new export markets created in Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and South America.61 Another market for cheap wines was the commercial production of brandies from the mid-1870s, using French stills and experts brought over to provide technical assistance.62 In 1887 the British consul noted that production was still in its “infancy”63 but two years later reported that “portable stills are being distributed amongst the vineyards of his district by an influential company recently formed, and an increased amount of capital is yearly being invested in this new brand of Jerez commerce,” while in Jerez itself, “several Houses” established large scale distilleries using the “Charente system.”64 Brandy for the first time gave the large sherry houses a major product to sell in the domestic market, but they found much cheaper wines for its production in La Mancha.

There were a number of even more ambitious attempts to diversify output, including an attempt in the early 1880s at producing sparkling sherry, which was “practically the typical sherry in an aerated form—a sort of concentrated sherry and seltzer.” It failed, as did the attempt a decade later to produce champagne using the champenois method with imported skilled labor from Épernay.65 Attempts to produce and promote nonalcoholic sherry were no more successful.66

The boom in Jerez in the mid-1860s had created business fortunes and widespread prosperity, with local wages doubling.67 Labor requirements were high, at an estimated annual 182 days work per hectare on the albarizas soil, 107 days on the barros, and 93 days on the arenas soil.68 Following the drop first in prices and then in exports, there followed a succession of business closures, widespread unemployment, and major social unrest. Employers cut costs by paying lower wages as well as using less labor. A group of workers petitioned the mayor of Jerez in the summer of 1866, noting that while the wages of day laborers had declined by half from the early 1860s, food prices had not fallen.69 In August 1882 El Guadelete, a local newspaper, wrote that “the majority of the vineyards in Jerez are found badly cultivated or virtually abandoned, covered in weeds or handed over to tenants who, with few resources, cultivate themselves obtaining a very small salary for their work with the selling of the grapes.”70 Some owners experimented with sharecropping, with “day labourers who, for the consideration of receiving from one-third to one-half of their produce, agree to cultivate and to properly keep up their possessions.”71 Although sharecropping had a long and successful history in some wine regions, such as Beaujolais and Tuscany, this would not be the case in Jerez, where the contract was primarily used by landowners to avoid having to negotiate with a militant labor force.72 The short-term nature of these contracts encouraged the sharecropper to maximize output with no concern for the long-term future of the vines.

There were also a number of possibilities for introducing labor-saving technologies. The substitution of the secateurs for the pruning knife in the 1870s and 1880s reduced the skills required for pruning and hence wages and was bitterly opposed by the workers, many of whom owned small plots of vines themselves but depended on seasonal employment on the large estates.73 Ridley’s noted in 1883 that a foreman had been murdered, “and the reason is supposed to be that he had been using scissors for pruning.”74 Elsewhere, labor-intensive methods continued to be used, with tillage being carried out using the azada, a type of hoe that was considerably more labor-intensive than plows. There were few changes in wine making, as the grapes were crushed by feet rather than machines, and, unlike in most other wine-producing regions, women were rarely employed in the vineyards before the turn of the century.75

Some in Jerez even regarded the approach of phylloxera as a blessing and hoped that wine shortages would produce “abnormally high prices.”76 When it finally appeared in 1894, it spread quickly, destroying virtually all the vines by 1909, by which date only a third of the area (2,640 hectares) had been replanted and the rest of the land was being used for cereals.77 The failure of prices to improve and financial hardship was one explanation for the slowness of replanting, but there were also the difficulties associated with finding suitable American roots because of the high limestone content on the albarizas soil, resulting in the early vines performing badly and leading to the vine disease chlorosis. The area of vines in the province of Cadiz fell from 21,000 hectares in 1882 to 6,000 hectares in 1904, leading to a loss of between three and four million days employment.78

WINE QUALITY AND THE DEMAND FOR A REGIONAL APPELLATION

Jerez was the only region of the four discussed in this section that had failed to establish a regional appellation by the early twentieth century, even though as early as 1844 Jacobo Walsh complained about the “deplorable state” of trade with England and the need for growers to establish in Jerez a “Gran Compania” that would export only local wines.79 A second, much wider debate began in the mid-1860s, when a newly created newspaper representing the interests of the growers and almacenistas claimed that exporters had “abstained from buying old wines from the almacenistas,” and later that “22 or 24,000 botas” of wine had been bought from outside Jerez and El Puerto de Santa María by train.80 Death threats were made to shippers for using wines produced outside these regions as sherry, and in 1871 it was noted that “within the last few days much damage has been wilfully caused in the vineyards by the discontents; in some places by cutting off all the branches and shoots, and in others by sweeping with a hard broom all the fruit.”81 The response of the exporters was not to deny claims of using outside wines, but rather to blame the poor local harvests and the need to be able to export very cheap wines to compete in the British market.82 This market for cheap wines led the agronomist Fernández de la Rosa in 1886 to propose two distinct “town brands”: one for local wines, and one for wines that had been produced outside the city.83 Growers and small winemakers continued to demand an exclusive sherry brand for locally produced wines, while the exporters argued that businesses located in Jerez or El Puerto should also be included, regardless of where wines came from. In 1914 the shipper Domecq suggested that local wines should be called “Jerez” rather than “Sherry,” as the “latter expression has become, to some extent, a generic term used to denote all manner of imitations of the original and genuine product.”84

This failure to create a regional appellation despite widespread local support can be explained by the lack of political voice of growers, and the fact that phylloxera helped strengthened the exporters’ control of the commodity chain as they integrated backward. By 1912–13 some forty houses owned 1,000 hectares of the 2,500 hectares that had been replanted in Jerez and were responsible for 30,000 botas of the 34,000 exported.85 When in 1935 a controlled appellation was finally established—the Consejo Regulador de la denominación de origen Jerez-Xérès-Sherry—the shippers were still able to buy outside wines when harvests were poor or prices high.86

The region of Jerez saw some of Europe’s worst rural violence in the half century prior to the First World War, with the anarchist “black hand” creating panic among property owners in the 1880s, and the city itself being stormed by unemployed rural workers in 1892. In France the Waldeck-Rousseau law of 1884 legalized trade unions in an attempt to encourage moderate workers to participate and reduce the influence of extremists. No such law existed in Spain, and the short periods when workers’ organizations were legalized often coincided with bitter strikes, followed by the inevitable repression. In rural Andalucía there was an increasing spiral of social conflicts occurring from the 1880s, followed by problems in 1902–3, 1918–20, and 1931–33, while during the Second Republic (1931–36) the agrarian problem and attempts at land reform, especially in areas such as Jerez, have been identified by historians as the single most important cause of the Civil War.87

It is tempting to argue that the increasing inequality and the lack of a legitimate political voice among field workers, small growers, and bodega workers forced them into radical nonparliamentary politics and violence, while the shippers used their political influence to block any attempts to establish a local appellation and thereby restrict their profits. Indeed, Temma Kaplan has claimed that “the evolution of anarchism in Northern Cádiz Province was inextricably tied to the declining prosperity of independent winegrowing peasants, pruners, and coopers after 1863, and their collective response to their condition.”88 Yet neither the winegrowers nor the bodega workers were attracted to radical politics. Laborers in the vineyards remained skilled and even in the 1900s earned at least double what day laborers were paid in cereal farming.89 It was workers in this second group—laborers who drifted from farm to farm for seasonal employment over the wide expanse of the Jerez plain and experienced a major decline in their employment opportunities—who were attracted to anarchism.90 By contrast, those who worked in the vineyards and bodegas belonged to the labor aristocracy and were more likely to follow moderate republicanism (and, when legalized, the moderate Union general de trabajadores) rather than preparing for revolution.91

The decline in demand for old, fine sherries was to be permanent. In 1895, even as harvests suffered because of phylloxera, the shipper Gonzalez Byass auctioned a considerable quantity of old sherry, which they considered in excess of requirements.92 A few years later Edward VII disposed of some sixty thousand bottles of sherry from the royal cellars.93 The shift toward cheaper wines was underlined by the Asociación Gremial de Exportadores, the shippers’ pressure group founded in 1910, which argued that for consumers sherry was not linked to a geographic area but was a generic name used for certain wines throughout the world. It therefore opposed any move to establish a regional appellation, claiming it would increase costs and reduce their competitiveness.94

By the late nineteenth century shippers were increasingly competing in the British and French cheap wine markets. Brand names for cheap sherries were weak, and the sale of large quantities of foreign wines as “sherry” implied that Jerez’s merchants had little option but to buy from low-cost producers such as La Mancha if they wished to compete in this segment of the market. The several thousand small growers in Jerez lacked the political support to create a regional appellation, as did the shippers to achieve legislation in London that limited the use of the word “sherry” to wines produced from Jerez, along the lines incorporated in the Anglo-Portuguese Commercial Treaties of 1914 and 1916.95 Trade did eventually recover in the twentieth century, but for cheap, rather than old mature sherries.96

1 Other local wines from Chiclana, Chipiona, Puerto Real, Rota, and Trebujera were also sometimes sold as sherry, as were those from el Condado (Huelva), Lebrija and the Aljarafe (Sevilla), and Montilla (Córdoba).

2 For the role of foreigners, see especially Maldonado Rosso (1999:264–69) and FernándezPérez (1999:77–79; also Ridley’s, various years.

3 In the mid-1880s the province of Cadiz produced 450,000 hectoliters, of which Jerez contributed 175,000, El Puerto de Santa María 120,000, Sanlúcar 65,000, and Chiclana 62,000. Local consumption was between 180,000 and 200,000 hectoliters (Archivo Ministerio de Agricultura, Madrid, legajo 82.2).

4 Quantities shipped were 66,321 butts (of 500 hectoliters each), and the price in Jerez was 40–250 pounds per butt (Shaw 1864:235).

5 Sherry represented a fifth of the country’s total exports in terms of value in 1850–54 (almost three times more than ordinary table wines), while sherry and other fortified wines (vinos generosos), accounted for half of all wine exports in terms of volume (Prados de la Escosura 1982, table 7; Dirección General de Aduanas, various years).

6 The early history of sherry “sack” is covered in Jeffs (2004, chap. 3).

7 Referred to in Jerez as mosto and vino en claro, respectively (Maldonado Rosso 1999:48–54). This was done by one of three different ways: arropado (or abrigo), the addition of concentrated grape syrup for making sweet wine; cabeceado, using older wines of higher strength; and encabezado, adding spirits to strengthen white wines.

8 Ibid., 60. Other guilds were established in Sanlúcar and El Puerto de Santa María.

9 Haurie’s legal victory was accompanied by the creation of a more liberal wine market by the real orden of 1776. Ibid., 133–39.

10 One major exception was Domecq, who in 1840 owned 460 aranzadas of vines in the Marcharnudo region. Visitors such as Busby, Ford, and Vizetelly have left accounts of Domecq’s business. In his study of thirty probate inventories of bodega owners for the period 1793–1850, Maldonado Rosso (1999:222–27) finds that twenty-one owned some vines, but only seven of these had more than 10 percent of their assets invested in vineyards.

11 Ibid., 333.

12 Faith (1983:45); Fernández-Pérez (1999:72–87); and Maldonado Rosso (1999:288–96).

13 Parada y Barreto (1868:71) estimates between one and half and two botas per aranzada. 5,000 hectares and a yield of 22 hectoliters per hectare, implies a maximum of 110,000 hectoliters, a figure that needs to be reduced by a sixth because of losses occurring during the wine-making process, maturing, and transportation. Even if all this wine was exported, it would have accounted for only a quarter of total sherry exports in the early 1870s.

14 Parada y Barreto (1868:59, 79).

15 Ibid., 114, 116.

16 López Estudillo (1992:50–53) provides a detailed discussion on the accuracy of contemporary estimates of the area of vines.

17 Simpson (1985b:174–84) considers the changes in grape varieties, increased labor inputs, and improved vineyard techniques on yields.

18 Jeffs (2004:178).

19 The bodega barrels were about 600 liters, compared with the 500 liters for those used in shipping. One-sixth of the wine was lost as ullage. Old sherries especially can reach naturally high levels of alcohol, if only because about 5 percent of the wine is lost each year through evaporation.

20 González Gordon (1972:143).

21 Ibid., chap. 5; Jeffs (2004, chap. 10).

22 Jeffs (2004:214–15); Montañés (2000:263). Appendix 2.A.5 shows that “old” sherry was still common, but the “Old Golden, Very Fine 1847” (Gonzalez Byass?) probably refers to a solera started in that year, rather than a vintage wine.

23 González Gordon (1972:105–6). This writer notes that “this was undoubtedly caused not only by the yeasts in the must itself but also by microorganisms existing in the vessels used.”

24 Jeffs (2004:209). Sherries change their character with age, and this classification refers to 1959.

25 Ridley’s, March 1892, p. 165.

26 Busby (1833:15). For the early development of the solera, see Maldonado Rosso (1999, chap. 9). The workings of the solera are described in González Gordon (1972:118–23). and Jeffs (2004:212–21).

27 Busby (1833:15).

28 Parada y Barreto (1868:129) and Vizetelly (1876:105) both give four years.

29 Drummond and Wilbraham (1958:337) note the custom of taking an aperitif before dinner was probably introduced in England in the early nineteenth century, although they do not specifically mention sherry.

30 Denman (1876:3). For a general survey of the problems, see Tovey (1877:158–61).

31 This is hinted at in Ridley’s, February 1856, p. 3.

32 Ibid., May 1860, p. 5.

33 In 1860 it was noted that exports since 1855 had been “supplied from the large stocks on hand, and not by late vintages” (ibid., February 1860, p. 5.

34 United Kingdom. Parliamentary Papers (1878/79), p. 176; and Ridley’s, April 1887, p. 166.

35 Revista Vinícola Jerezana, 1/9 10.5.1866. This newspaper continued,

the exporters . . . not being able to pay . . . the high prices then being asked, had to look to other . . . areas; as a result, Montilla wines began to compete with our better wines, and those from the Condado (Huelva) and Sevilla, with the poorer ones. This novelty led to fierce competition in our region . . . and . . . was the origin of the adulteration of Jerez’s wines.

36 United Kingdom. Parliamentary Papers (1878/79), p. 169; also p. 119. See also Espejo (1879–80, 4:651–52).

37 Revista Vinícola Jerezana, 1/6 25.3.1866, p. 44.

38 Ridley’s, February 1867, p. 2.

39 Ibid., September 1863, p. 16. George Ridley was subsequently given the Cross of the Order of Carlos III in 1870. Ibid., March 1870, p. 4.

40 Waugh (1957:6).

41 Quoted in Tovey (1883:7). Emphasis in original.

42 United Kingdom Consular Reports (1865), no. 53, p. 657. Jerez produced its own version of Hamburg sherry according to the British consul’s report of 1865:

During the past year large quantities of wines have been introduced into the district from Malaga and Alicante; but these wines have not proved serviceable or usable, their peculiar, earthy and tarry character being impossible to overcome; as, although mixed with other wines but in small quantities, the unpleasant flavour and “smell” is always distinguishable to a judge of wine.

This did not stop the wines being used, however. “The low spirituous compounds are made up with molasses, German potato-spirit, and water; to which some colouring matter, and a small quantity of wine are added; much in the same manner that the ‘Hamburg-sherries’ have been manufactured to which of late the London Custom-House has, very properly, refused admission.”

43 Faith (1983:12); Ridley’s, January 1877, p. 3. “Castle” was the brand name of Gilbey’s. Given Gilbey’s insistence on quality, it seems unlikely that their version was prejudicial to health. However, it created confusion for consumers.

44 United Kingdom. Parliamentary Papers (1878/79), H. P. Gilbey, p. 149.

45 Shaw (1864:217).

46 United Kingdom. Parliamentary Papers (1878/79), pp. 121, 122, 170, 266.

47 See especially Pan-Montojo (1994:103–10).

48 The British authorities were concerned primarily with the implications on revenue, as a too liberal duty risked encouraging an increase in consumption of strong wines at the expense of spirits. In terms of alcohol content, spirits were already taxed more than wine (although tax on beer was less). There was also concern that lower duties would result in strong wines being imported to be illegally distilled, even though cheaper alternatives, such as alcohol produced from maize, oats, sugar, and other products, existed. United Kingdom. Parliamentary Papers (1878/79), pp. 26, 55, 162, 182.

49 Ridley’s, February 1888, p. 58, 62, 70; October 1888, p. 474.

50 Ridley’s, November 1898, p. 762.

51 United Kingdom. Parliamentary Papers (1878/9:176.

52 See Jeffs (2004), pp.93–6 and 174–7.

53 John Haurie (nephew) told his buyers in 1857 that the firm had secured the stocks of the three largest Almacenistas in Jerez, which added to our own, enable us to offer sound wines as will maintain the reputation of our former shipments” (Ridley’s, October 1857). Emphasis in the original. In 1862 Gonzalez Byass bought 92 butts of old sherry for £10,000. Ibid., July 1862, pp. 2, 3.

54 Domecq, for example, shipped large quantities of “light low” wines in 1864 and 1865 that did not carry the firm’s brand. Ibid., January 1866, p. 7. Likewise, Gilbey’s imported unbranded sherry and white wine from Gonzalez Byass. For the impact of this cheap wine trade on a shipper’s profits, see especially Montañés (2000).

55 Ridley’s, February 1878; also March 1871; January 1874.

56 Gonzalez Byass’s 1878 price list for Cadiz, reproduced in Montañés (2000:264). Tio Pepe was introduced at the lower duty of 1s a gallon. Retail prices calculated from Simpson (2005b, table 1).

57 Harrison (1955:106) gives 1882 as the date for Bristol Cream, and it is not shown in Harvey’s 1867 price list reproduced opposite Harrison’s p. 115. However, Ridley’s, July 12 1880, p. 209, cites an auction of one of Harvey’s customers where twenty-two dozen cases of Dark Gold Sherry, Bristol Milk, bottled December in 1862, and twenty-three cases of Old Pale Sherry, Bristol Cream, also bottled in 1862, selling at around a pound sterling per bottle.

58 Appendix 2.A.5.

59 “Instead of selling to market Houses parcels of several hundred butts at a time, and leaving the latter to distribute them, the majority of comparatively small Wine Merchants go to the Shipper direct and order their butt, hogshead or even quarter-cask from head-quarters. Each has his own fancy as to the proportion of “dulce,” colour or style as the case may be, and each parcel, however small, has to be made up separately on these lines.” Ridley’s, March 1892, p. 164.

60 El Guadalete, April 22, 1908. González Gordon (1972:36) suggests another company, J. de Fuentes Parrilla, as being the first, between 1871 and 1873. The first bottle factory in Jerez was not established until 1896 (ibid., 172).

61 Revista Vitícola y Vinícola, November 16, 1884, p. 7; and Fernández de la Rosa (1909, 2:261).

62 González Gordon (1972:183). Spirits (aguardiente) had traditionally been produced in the region for fortifying wines, but the low import duties led to large quantities of German industrial alcohol being imported. In Jerez itself there were eight modern alcohol factories by 1886, with a capacity of 30–40,000 hectoliters, although production was limited at the time to 8,000 hectoliters. Nevertheless, these 8,000 hectoliters required about 70,000 hectoliters of poor quality wine. Archivo Ministerio de Agricultura, Madrid, legajo 82–2.

63 United Kingdom Consular Reports, Cadiz (1888), no. 103, p. 135.

64 Ibid. (1890), no. 714 (Cadiz for 1889), p. 4; and Ridley’s, January 1890, p. 34.

65 Ridley’s (June). Three Jerez firms marketed the drink at the high price of 52s. per dozen f.o.b. Ridley’s, April 1881, pp. 106–7; June 1891, p. 409.

66 Ibid., July 1881, p. 207.

67 Ponsot (1986) gives an increase from slightly under 10 reales (2.5 pesetas) to 19 reales from the early 1850s to the early 1860s. In Catalonia, by contrast, wages increased from 2 pesetas to 2.2 pesetas (Garrabou and Tello 2002:629). See also Simpson (1985b:180–82); López Estudillo (1992:48).

68 As these refer to tax estimates for 1857, they are probably a minimum. Montañés (1997:69).

69 Revista Vinícola Jerezana, 1/9, 10.5.1866, p. 70. In December the same newspaper (1/23, 10.12.1866, p. 179) noted that “the cultivation of our vines, the basis of our wealth, is decaying visibly.”

70 El Guadelete, August 12, 1882.

71 United Kingdom Consular Reports (1885), part 6 (Cadiz for the year 1884), p. 928. See also Crisis Agrícola y Pecuaria (1887–89, 3:168; 4:34), both cited in Zoido Naranjo (1978:69).

72 Landowners preferred the less radical workers as tenants. See López Estudillo (1992:67–68). For sharecropping and viticulture, see Carmona and Simpson (forthcoming).

73 Fernández de la Rosa (1909:466); Revista Vitícola y Vinícola (1884), no. 3, p. 6; Crisis Agrícola y Pecuaria (1887–89), vol. 4, no. 236, p. 36.

74 Ridley’s, December 12, 1883, p. 358.

75 Vizetelly (1876:16) noted that “advocates of woman’s rights will regret to hear that the labours of the softer sex are altogether dispensed with in the vineyards of the South of Spain,” but the socialist newspaper El Viticultor (October 6, 1900, no. 56) noted that women were being employed at the harvest at between three quarters and one peseta a day, compared with the three pesetas earned by men.

76 United Kingdom Consular Reports (1896), no. 1839 (Cadiz), p. 3.

77 Archivo Municipal, Jerez de la Frontera, legajo 523.

78 Quevedo y García Lomas (1904:57–58). The number of workers in Jerez’s vineyards fell from an estimated 5,000 in the 1880s to 2,400 in 1921 according to Montañés (1997:139).

79 Walsh (1844:3–5). Walsh envisaged a public company that would require no privileges and remain independent of the state.

80 Revista Vinícola Jerezana, January 1866, p. 1; June 1867, p. 283. This was equivalent to 110,000–120,000 hectoliters.

81 Ridley’s, May 1871, p. 7.

82 Cabral Chamorro (1987a:178).

83 Ibid., 181.

84 Ridley’s, February 1907, p. 103.

85 Cabral Chamorro (1987a:191).

86 Ibid., 193–94. The 1935 law provided a minimum length for maturing wine and a minimum alcoholic strength, controlled grape yields, fixed minimum export prices, and restricted exports to 60 percent of a shipper’s stock in a single year. As elsewhere, there have been frequent modifications of the clauses. Fernández García (2008:195–96).

87 Preston (1984:159–60); Malefakis (1970). The level of conflict varied significantly within Andalucía.

88 Kaplan (1977:12). This claim has been convincingly challenged by Cabral Chamorro (1987a). See also Montañés (1997).

89 In 1905–6 vine growers earned 2–3.5 pesetas a day, compared with the 0.5–1.25 earned by agricultural workers. This second group, however, was given food equivalent to 0.75 peseta. Archivo Municipal, Jerez de la Frontera, Protocolo Municipal 404 (1905–6).

90 Cabral Chamorro (1987b) and Montañés (1997). For the segmented local labor markets and their influence on conflicts in Andalucía, see Carmona and Simpson (2003, chap. 3).

91 Cabral Chamorro (1987b).

92 In total, some 2,500 butts (Ridley’s, March 1895, p. 159). Ridley’s noted in May 1895 that “the very fine Wines fetched good prices, and the medium Wines fair ones, although, on the other hand, the cheaper descriptions, which showed signs of a hurried preparation for shipment, cannot be said to have sold particularly well” (304). The sale made £66,000, an average of £26 per butt.

93 Jeffs (2004:103).

94 Cabral Chamorro (1987a:192).

95 Shippers recognized the importance of the collective brand, resulting in the creation of a lobby in London in 1910, a fact particularly welcomed by Ridley’s, which hoped it would “stop the rot” (January 8, 1913, p. 9). The Asociación de Exportadores de Vinos was founded in 1885, and the Asociación Gremial de Criadores Exportadores de Vinos in 1889 (González Gordon 1972:41).

96 Fernández (2010); Jeffs (2004).