CONCLUSION

![]()

THIS BOOK has followed the growth and development of wine production from mostly small-scale family operators in southern Europe to a worldwide concern, with large-scale industrial producers using scientific wine-making methods and modern marketing techniques to sell their wine. Change was not uniform, and by 1914 major differences were found in the organization of production and marketing of commodity wines in places as far-flung as France, California, South Australia, and Mendoza. Even within a country such as France, new and differing institutions had appeared that altered market incentives for growers, wine-makers, and merchants in places such as Bordeaux, Reims, and Montpellier. The changes that occurred in the half century or so before the First World War can be fully understood only by taking a broad view of the sector. In particular, while the international transfer of scientific knowledge and production technologies was becoming increasingly common, most producers found themselves in two very distinct camps: those supplying markets where wine was the alcoholic beverage of choice, and those where new marketing systems had to be developed to allow wine to compete with other well-established drinks, such as beer and spirits. The divergence between the Old and New Worlds has also been explained here by the differences in resource endowments and the highly favorable growing conditions for grapes in the New World, and the political strength of growers to influence government policy in Europe. This part of the book looks briefly at the changes that took place among traditional producer countries in Europe and then offers some comments concerning the obstacles facing the producers in the New World. It finishes with reflections on the extent to which the organization of the wine industry today is the result of changes that took place before 1914.

OLD WORLD PRODUCERS AND CONSUMERS

In Europe’s wine-producing countries, rising real wages, falling transport costs, and growing urbanization contributed to per capita consumption increasing significantly, and by 1914 the French (including their children) drank on average around 150 liters per person per year, while consumption reached 120 liters in Italy, 90 liters in Portugal, and 85 liters in Spain. These levels are impressive especially considering that large areas of Europe’s vineyards were decimated by phylloxera and growers also had to fight other new vine diseases, such as powdery and downy mildew. In the case of France, the only country for which reasonably accurate figures exist, output collapsed from an annual average of 57 million hectoliters between 1866 and 1875 to 30 million between 1886 and 1895. In response to these domestic shortages, France switched from exporting the equivalent of 5 percent of domestic production to importing 19 percent of its needs.

Phylloxera-induced shortages and the resulting higher wine prices produced a variety of responses among growers and winemakers. First, in large areas of Spain, for example, there was a major increase in production as land and labor were diverted away from extensive livestock and cereal production to viticulture. Technical change was limited, and wines were made stable for export by adding spirits, often produced from cheaper vegetable matter such as sugar beet and potatoes rather than grapes. By the late 1880s perhaps a third of Spain’s production was exported to France.

Elsewhere, technological change played a greater role, in part because the fight against phylloxera led to large amounts of scientific research, which allowed growers to choose grape varieties better suited to their vineyards. For most producers, profitability was positively correlated with yields rather than quality, encouraging them to increase output, so that while production was little different in France at the beginning and end of our period (1850–1914), the area under vines declined by about a third. At the extreme, growers in the Midi used irrigation and heavy inputs of chemicals and planted hybrid vines that produced yields of over 100 hectoliters per hectare. Regions specialized according to their comparative advantage, and the Midi’s thin, low-alcohol wine was blended with Algeria’s wines for their good color and high alcohol content, thereby creating a cheap, drinkable alcoholic beverage for the Parisian and industrial consumers.

Changes in wine-making technologies were potentially as important as anything that took place in the vineyard, and by the 1900s the leading producers were controlling the temperature of the must during fermentation, correcting its acidity, and using cultivated yeasts. The new wine-making technologies and cellar designs increased the amount of wine produced from a ton of grapes and cut labor costs, an important consideration as in many areas farm wages were increasing. Winemakers were also now able to consistently produce drinkable commodity wines in hot climates. There was a much lower incidence of vine disease in these regions; land was usually considerably cheaper than in northern Europe; and large areas of vines could be easily cultivated using plows. There followed a major relocation of the industry, and France’s four departments in the Midi and Algeria saw their production increase from the equivalent of a fifth of France’s domestic consumption in 1852 to a half by the 1900s. In the rest of Europe, the shift to hotter regions occurred more slowly, in part because phylloxera took longer to destroy traditional areas of viticulture, but also because of the much slower diffusion of new wine-making technologies and the weaker integration of the national market.

The high prices of the 1880s led to adulterated wines becoming common in both producer and nonproducer countries, and their presence continued when prices collapsed at the turn of the century. While fraud had always been present in food and beverage markets, the growing physical separation between producers and consumers and the development of new preservatives allowed manufacturers to mask food deterioration and lower costs, making food adulteration imperceptible to consumers. By 1900 consumers often had little guarantee of where the product had been made, what percentage of it was made from grapes, or indeed whether it was actually safe to drink. Furthermore, the French economist Charles Gide believed that the presence of cheap, spirit-based drinks had finally checked the growth in wine consumption.1 The combination of stagnant demand, widespread adulteration, and the recovery in domestic production following the replanting with high-yielding vines after phylloxera led to overproduction. Markets failed to self-correct because growers and merchants had financial incentives to adulterate wines, especially after a poor harvest when prices increased; growers in the Midi sold their wines at a loss in five out of seven years between 1900 and 1906, provoking massive demonstrations.

The sector’s success in increasing output and consumption in the face of destruction caused by vine disease makes its failure to develop export markets all the more important. Except when phylloxera devastated French domestic production, trade between producer countries was restricted by high tariffs. Among nonproducers, Britain imported over half its food and was potentially a major wine market. This urban and relatively rich country, with a long tradition of importing fine wines, passed legislation in the early 1860s that was specifically designed to encourage the import and consumption of cheap wines, especially among the growing urban middle classes. Wine consumption increased by 140 percent between 1856–60 and 1871–75, but although import duties remained stable and real wages continued to increase, per capita consumption then declined so that on the eve of the First World War it was similar to what it had been a hundred years earlier on the eve of Waterloo.

The attempts to convert a country of nonconsumers to become wine drinkers failed because private firms were unable to maintain or even guarantee wine quality. Unlike producer countries, where legislation was passed that defined wine as being made from crushed grapes and prohibited the sale of imitations, the law remained more lenient in nonproducer countries such as Britain. Alcoholic drinks such as Hamburg sherry, or Britain’s infamous “basis wines,” which were manufactured from imported grape juice and other substances and then mixed with French wines and sold as claret, even damaged the reputation of fine clarets and sherries. The important economies of scale found with some foods and beverages in processing, packaging, and distribution encouraged firms such as Cadbury’s and Lipton’s to spend heavily on branding and advertising were therefore absent with cheap wines whose quality could change radically from one harvest to the next. There was insufficient volumes of business to make mass publicity profitable for chains stores such as Gilbey’s and the Victoria Wine Company.

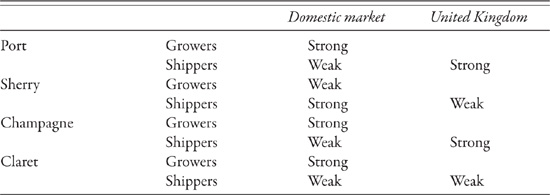

TABLE C.1

Negotiating Strength of Growers and Shippers in Domestic and British Markets in the Early Twentieth Century

The problems associated with adulteration and fraud encouraged Europe’s growers, winemakers, and merchants to try and redefine the nature of the industry. The speed at which new economic institutions such as regional appellations and cooperatives appeared reflected the political structure and relative negotiating strength of the growers and shippers in each country. In France Jules Ferry famously declared in 1884 that the Third Republic “will be a peasants’ republic or it will cease to exist.”2 In exchange for votes, French politicians were happy to adopt policies that protected small family producers, but the rural elites in Spain and Portugal continued to enjoy considerably more political power. Consequently growers in Bordeaux and Champagne were successful in creating the framework for a regional appellation before 1914, but not those in Jerez. Growers in Porto also lacked electoral influence, but the Portuguese government backed their demands in the face of opposition from British shippers. The situation in the British market was different, however, as both Bordeaux and Jerez shippers faced competition from clarets and sherries produced in other countries, but the port wine shippers persuaded the British government to protect their product in the 1916 treaty. Champagne producers, by contrast, had much stronger brands, in part because the wines had to be bottled at source.

Technological change and market integration also produced tensions along the commodity chain for cheap table wines. In particular, problems of vertical coordination between grape producers and winemakers arose at the beginning of the twentieth century because of the growing economies of scale that were associated with the new wine-making technologies. Even under optimal conditions, with the new vineyards planted on the fertile plains to allow plows to operate between the long rows of vines and thereby save labor, a family farm was rarely more than 8 or 10 hectares. In reality the high concentration of vines and their haphazard planting, together with the fragmentation of property, led to most vineyards in the Old World being much smaller. By contrast, changes in wine-making technologies increased capital and skill requirements and threatened traditional family wine making, while improved transportation allowed merchants to obtain wines from much wider areas, permitting them to avoid particular regions after poor harvests, and making it harder for small producers to sell their surplus produce.

A number of influential French writers, such as Charles Gide and Michel Augé-Laribé, saw wine cooperatives as a solution as they allowed the efficient family vineyards to coexist alongside large, capital-intensive wineries. Cooperatives promised to produce better-quality wines at a lower cost than those made in the small “peasant” cellars and provide cheap storage space for wines to mature, rather than having to be sold immediately, and thereby allow growers to enjoy higher prices. They also offered the possibility for processing the wine lees—the remains of the grapes after they had been crushed—to make alcohol and tartaric acid. A typical French wine cooperative on the eve of the First World War had about 160 members, whose members each had an average production of just 50 hectoliters of wine, coming from little more than a hectare of vines. However, there were formidable organizational problems in creating cooperatives, including the lack of capital, the absence of experienced management, and the difficulties associated with measuring grape and wine quality. Government legislation eased credit restrictions and led to the number cooperatives in France jumping from thirteen in 1908 to seventy-nine in 1913, of which fifty were found in the South. Considerably interest was also shown in Italy and Spain, but in these countries the cheap credit needed to construct new wineries was lacking until at least the interwar period.

NEW WORLD PRODUCERS AND CONSUMERS

The vine followed European settlement in the New World and North Africa, but commercial production became important only at the end of the nineteenth century, as Algerian production increased from a million hectoliters in 1885 to 8.4 million by 1910 on the back of its privileged access to French markets, while in the New World it went from virtually nothing in the 1870s to 3.8 million hectoliters in 1910 in Argentina, 2 million in Chile, 1.8 million in California, and 0.2 million in Australia. Much of the growth coincided with the introduction of new wine-making technologies that incorporated significant economies of scale and lowered unit production costs.

The very different factor endowments of the New World implied that the industry developed its own style and characteristics, and producers enjoyed a number of important advantages over those in northern Europe. Grape growing was relatively easy, as the warm conditions allowed the fruit to mature fully and there was a much lower incidence of disease and rot. Land was cheap and the vines started producing after just three years, rather than the four or five common in most of Europe. Vineyards were extensively cultivated, allowing plows to operate freely along the rows, reducing labor inputs to a minimum. A number of very large vineyards existed, but even in the labor-scarce New World, considerable quantities of grapes were still produced on small, family-operated vineyards rather than on large estates. Thus in Napa and Sonoma in California, only 37 percent of the vines were found on holdings greater than 25 hectares in 1891, and in Victoria, Australia, only 27 of the state’s 850 growers had more than 24 hectares in 1890.

By contrast, and to a much greater extent than in either the Midi or Algeria, specialist grape growers supplied the new industrial wineries because the high and consistent grape quality made it much easier for winemakers to negotiate contracts with such growers, thereby reducing potential conflicts at harvest time. Wineries were purpose-built to reduce the costs of crushing large quantities of grapes in short periods of time and the labor-intensive processes of moving wine around the winery in an age before electric pumps. The new wineries’ greater capacity permitted investments in laboratories, technicians, and fermentation cooling systems to be spread over larger quantities of wine, helping to erode the competitive position of the small wine maker.

A favorable terroir also allowed more homogenous wines to be produced. These were not necessary better than Europe’s vin ordinaire, but they did allow merchants to accumulate large batches of wines with similar characteristics from one year to the next. Yet despite the hopes of some contemporaries that their countries would soon be able to supply Europe with cheap table wines, the reality was that the New World industry, with the exception of Australia, remained one of import substitution depending on tariffs and protected markets. Production was often located at considerable distances from major markets, and the structure of the commodity chain differed according to whether producers were able to sell to immigrants who originated in Europe’s wine-producing regions such as in Argentina, or whether they had to create new markets as in Australia and California.

In California, the growth in demand, new wine-making technologies, and widespread adulteration of wines required new forms of business organization if the high levels of capital investment in vineyards and winery equipment were not left idle. Growers lacked political support, but a lenient regulatory environment toward trusts encouraged the formation in 1894 of the California Wine Association, a combine created by the leading San Francisco wine dealers. By 1897 the CWA controlled 80 percent of wine sales and integrated vertically from grape growing to distribution on a massive scale. By controlling distribution, it achieved the necessary market stability for it to invest in brand names, and growers in California probably suffered less during the turbulent 1900s than in any other wine-growing region in the world. Yet the vast majority of U.S. citizens were unaccustomed to drinking wine, and the economies of scale associated with the production and marketing of dessert wines, as well as a favorable tax regime, led to a much faster growth in their production than table wines, so that by 1913 they accounted for 45 percent of all Californian wines, of which 46 percent was classified as port, 31 percent as sherry, 12 percent as muscatel, and 9 percent angelica. However, although politicians considered wine to be sufficiently unimportant and permitted the CWA to act with relative freedom, they were unwilling to ignore the powerful Prohibition lobby, which made it illegal to sell wines and other forms of alcohol after 1919.

The high entry costs to marketing wines on the U.S. East Coast before Prohibition was overcome by a producer-led commodity chain. By contrast, in Australia it was a market-led chain that was created to sell dry, red table wines in London, some 20,000 kilometers away, despite freight costs being three times greater than those facing French exporters. Trade was dominated by two major London houses that specialized in Australian wines: Walter Pownall and, in particular, Peter Burgoyne, who claimed in 1900 to have exported fully 70 percent of the wine sent from Australia to England between 1870 and 1900 and to have invested £300,000 in advertising so that “Burgoyne’s Australian Wine” placards were found “on every railway station in England.” Australian producers resented the control exercised by the two British importers, but attempts to create an alternative marketing system failed. Winemakers such as Hardy or Penfold lacked the resources and scale to establish permanent representation in London, and attempts to create government-sponsored companies suffered from a lack of finance. In addition, any publicly owned institution, whether it was a regional cooperative in Australia or a depot in London, suffered from selection problems because of the need to be able to reject substandard grapes and wines. As Arthur Perkins noted in 1901, it was possible to detect whether a wine was sound or unadulterated, but on “the question of quality none will agree.” The Australian industry remained divided in 1914, with approximately 20 percent being high-quality table wines destined for the British market and much of the rest being low-grade wines for domestic consumption. As in California, the leading wineries, such as Seppeltsfield and Penfold, turned increasingly to brandy and fortified wines, which were both easier to brand and market than table wines and popular among infrequent drinkers as they enjoyed a much longer shelf life once opened.

Finally, in the early twentieth century a dozen or so massive wineries dominated the Cuyo industry in Argentina. Wine quality was sufficiently homogenous to allow these wineries to brand their own wines, but production techniques remained primitive because the Mediterranean immigrants were unwilling to pay a premium for better-quality wines. During the periodic crises, when the major winemakers simply refused to buy the growers’ grapes, disused wineries were reopened, allowing supplies to be maintained in a glutted market and keeping prices low. In Mendoza and California the political climate was relatively permissive to big business and trusts, and both regions with less than 5 percent of their nation’s population produced around 95 percent of the domestic wine supply. Unlike in California, however, wine was considered an integral part of the Argentine diet, and the Buenos Aires government was unwilling to permit a trust or monopoly to manipulate prices, while regulators were much less concerned in the United States.

THE WINE INDUSTRY IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

Today’s distinctive organizational structures in the Old World and the New World were clearly visible by the First World War. In Europe the industry was fragmented into hundreds of thousands of small, family farms, while in the New World it was dominated by a handful of large, highly integrated firms such as the CWA, Domingo Tomba, and Burgoyne. Producers in places such as Bordeaux, Burgundy, and Champagne had long provided small quantities of fine wines to a limited number of connoisseurs, but now the combination of new production technologies, institutional innovations, and organizational structures offered the possibilities of producing better-quality commodity wines everywhere. Yet progress was slow as the economic incentives to make the necessary investment remained weak for at least half a century after 1914, so there was no reason for producers to plant shy-instead of heavy-bearing vines, invest in the new wine-making equipment, or study the basic principles of viticulture and enology. As late as the 1960s, production and consumption in the alcoholic beverage industry was still “country and culture specific,”3 and only with the major changes in consumption habits in the past thirty or forty years has it become profitable to improve the quality of cheap wines. But as consumers in countries such as Italy, France, and Spain steadily moved up the quality ladder, they not only stopped drinking large quantities of cheap wine, but also switched to other types of alcoholic beverages and soft drinks. High tariffs limited trade and kept production country specific, and this perhaps explains why even today it is difficult for European consumers to find foreign wines outside specialist stores. A combination of growers’ reluctance to scrub up “inferior” vines and productivity improvements have led to large quantities of wine being produced that no one wants to drink. Today Bordeaux’s best clarets may sell for astronomical prices, but vast quantities of this region’s cheaper wines remain unsold and destined for the still.

Change was initially driven by shifts in demand in nonproducer countries, and in particular Britain and the United States. In the former, millions of tourists were introduced to wine during their package holidays on the Mediterranean coast. Rising living standards and the possibility of purchasing cheap wine in supermarkets at home led to a huge increase in sales, while a new generation of writers led by Hugh Johnson, who published his first Wine Atlas in 1971, helped to educate the more adventurous consumer.

In California commercial wine production had to effectively start from scratch after Prohibition. As James Lapsley notes, the work of Hilgard and Bioletti suggests that on the eve of Prohibition California had passed the first phase of avoiding bacterial spoilage and was firmly in the second phase of improving quality through the use of pure yeast cultures, sulfur dioxide, and cooling, and if Prohibition had come ten years later, a “scientific understanding of winemaking would have had time to spread and take hold throughout the industry.”4 Instead, by the 1930s, after Prohibition was repealed, most winemakers could not produce a drinkable, good dry wine and consumers were unable to appreciate one, so that about three quarters of production was dessert wines and approximately half of all dry wine was homemade from purchased grapes. Change was slow, and in the late 1940s almost all the quality producers in Napa were also still producing bulk and generic wines. However, by this time the region has achieved “a critical mass where social organization for regional promotion and interchange of technology was assured.”5

A similar story is found in Australia, where Burgoyne’s influenced disappeared after the First World War with the growth in the British demand for dessert rather than dry table wines. There was no prohibition in Australia, but the strong temperance movement, on the one hand, and a migrant population with a tradition of strong spirits and beer, on the other, limited the size of the domestic market for dry table wines. As in California, even in the mid-1960s more fortified wines were produced than table wines, but now there was a “giant leap in output” of the classical grape varieties, as well as important advances in winemaking technologies that allowed for a “remarkable improvement in the quality of light table wines made from Riesling, Semillon, Cabernet and Shiraz grapes grown in Australian irrigated vineyards.”6

In Europe, if wine quality was slow to change, the set of economic institutions chosen on the eve of the First World War was a major factor in determining the future structure of the industry. Over the twentieth century the small family grower continued to enjoy the protection of the state, although the nature of institutions such as cooperatives and appellations d’origine contrôlées adapted over time to reflect the shifts in economic and political influence of producers. In France the creation of a wine monopoly, such as those proposed by Bartissol or Palazy in the 1900s, became unnecessary as growers looked directly to the state to resolve the problems of overproduction and low wine prices when they reappeared in the 1930s. Legislation was passed that regulated markets favoring small producers, and the transaction costs associated with complying with the new regulations were absorbed by the state. From the 1950s state intervention increased and spread to other European countries, helping the small family grower to remain in business today, but often at the expense of slowing producers’ response to shifts in market demand and leading to persistent structural problems of overproduction.

The switch from commodity to fine wine production has been slow over the last couple of centuries. In his recent book David Hancock talks of how British merchants in the eighteenth century happily exchanged information among themselves to perfect wine-making technologies, just as James Lapsley finds producers doing in the Napa Valley after the Second World War.7 Collective invention and product innovation that led to better-quality wines improved the region’s reputation and made it easier for all producers to sell their wines. There was also recognition of the need for the generic promotion of regional wines, as the potential for advertising was considerably greater than for what a single grower could achieve. Perhaps not so much has changed since the times of Busby, Civit, and Haraszthy, who, in their attempts to emulate Europe’s great wine producers, discussed the extent that technology can substitute for terroir.

1 Gide (1907).

2 Wright (1964:13).

3 Lopes (2007:1).

4 Lapsley (1996: 51).

5 Ibid., 135.

6 Simon (1966:xi, 3).

7 Hancock (2009); Lapsley (1994:204).