CHAPTER 11

![]()

Argentina: New World Producers and

Old World Consumers

To sell what the couple of dozen wineries do here (Mendoza) would need in France a hundred merchants . . . and need the output of several thousand producers.

—José Trianes, 1908:26

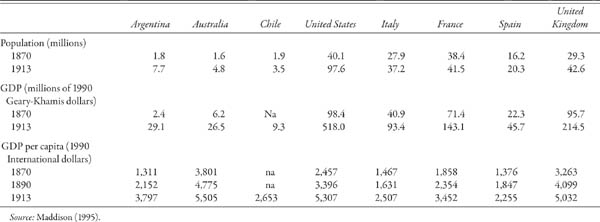

ARGENTINA between 1869 and 1914 embarked on a period of exceptional growth, with per capita income increasing by an average of 5 percent a year and population jumping from 1.74 million to 7.89 million. By 1914 Argentina had a higher per capita income and real wages than in most European countries (table 11.1).1 Economic growth was caused by exogenous factors as falling transport costs and external demand gave farmers a comparative advantage in the production of raw materials (hides and wool) and later foodstuffs (wheat and frozen meat). High wages attracted European migrants and were accompanied by large flows of capital to construct railways, port facilities and urban amenities. Between 1869 and 1914 the population of Buenos Aires grew from 182,000 to 1,576,000 inhabitants at an average rate of 6.5 percent a year; it was the second most populous on the Atlantic seaboard, after New York, and three times larger than Madrid or Rome.2

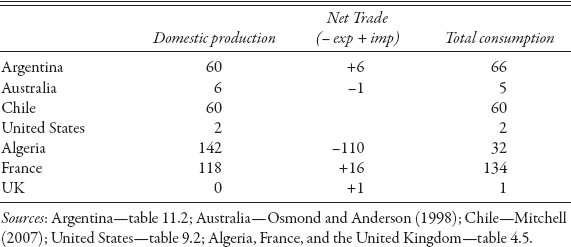

Grape-growing conditions in Mendoza were exceptional, and once this region was connected by rail with Buenos Aires (1884) and producers learned the art of controlling fermentation in the hot climate, the possibilities of selling large quantities of cheap branded wines in the rapidly growing market appeared endless. With the exception of Algeria, Argentina’s industry grew faster than anywhere else in the world between 1885 and 1914, making it the seventh largest producer, with an annual per capita consumption of 60–70 liters, considerably more than either the United States (2 liters) or Australia (5 liters). Yet contemporaries found little to praise because the industry appeared incapable of eliminating the frequent deep recessions into which it was plunged, and despite high standard of living per capita wine consumption remained less than half that of France.

TABLE 11.1

Population, GDP, and GDP per Capita in Various Countries, 1870–1914

Factor endowments in Argentina were similar to those in Australia and California, as labor and capital were scarce and nonirrigated land was abundant. One major difference was that most immigrants were already wine consumers, and some had firsthand knowledge of the industry, although frequently this had been acquired in regions that showed few of the characteristics of their new country, especially as Argentina’s vines depended on irrigation. By the final decade of the nineteenth century, a dozen or more large wineries dominated the industry, supplied by large numbers of independent specialist family grape producers. Just as in California, a relatively small region (Cuyo) accounted for over nine-tenths of the country’s output but had just 5 percent of the nation’s population in 1914.3 While big business and “trustification” were as much features of the Argentine economy as they were in the United States, attempts at collusion by Mendoza’s leading wineries had only limited success. This was because if the large wineries could usually count on the active support of the local provincial government in Mendoza, the federal government in Buenos Aires was unwilling to accept blatant price-rigging for an item that was part of the country’s staple diet.

This chapter first looks at the growth of the industry after 1885 and its organization at the turn of the century. The second section examines the response of different groups to the major slump in 1901–3 and shows that although attempts to self-regulate the industry were generally successful, wine quality remained poor because consumer choice was determined by price. Finally, the chapter considers the response of different sectors to the collapse in wine prices after 1913 and shows the difficulties leading producers faced in passing the costs of adjustment on to growers and restricting supply.

ESTABLISHING THE INDUSTRY

The Cuyo region, which contains the provinces of Mendoza and San Juan, is located in the extreme west of the country, at the foot of the Andes. In this arid region, with an annual rainfall of just 200 millimeters, crops can grow only with irrigation fed by the melting snow during the hot summer months. The criolla vine was introduced into the region from what is present-day Chile as early as the sixteenth century, but in the early 1880s the region still specialized in fattening cattle for the Chilean market, and the population of Mendoza was just 9,900 inhabitants and that of San Juan, 10,600.4 The victory of the centralist state and enforcement of the constitution, the creation of a national currency (1881), and the opening of a rail link between Mendoza and Buenos Aires changed the local economy and allowed commercial wine production to become a serious proposition.

A revival of interest in viticulture occurred a decade or two before the railways. In 1870 Eusebio Blanco translated Henry Marchard’s Traité de la Vinification, adding notes of his own, and in 1887 Emilio Civit wrote Los Viñedos de France y los de Mendoza and advised Tiburio Benegas, who was the provincial governor (and also his brother-in-law), on the future of the local industry. In both cases, the recommendation was to produce fine wines, copying the best French practices. In part this was because of the French influence on the local wine industry in neighboring Chile, but also because poorly made wines would not survive the long trip to Buenos Aires, and only fine wines selling at high prices would be profitable for producers.5

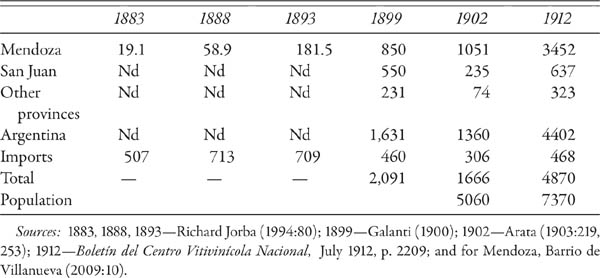

The works of Blanco and Civit influenced state policy toward the sector, although interest in fine wine production remained limited. A local law in 1881 exempted growers from taxes on new vineyards, a new irrigation law was passed in 1884, attempts were made to attract European settlers, and the Banco de la Provincia de Mendoza was created in 1888.6 However, the rapid growth in viticulture owed more to market incentives than government backing, and in particular the creation of a rail link between Mendoza and Buenos Aires. Wine output increased fourfold between 1883 and 1899 (table 11.2), driven by population growth, import substitution, and growing per capita income. On the eve of the railway link, Mendoza had just 2,000 hectares of vines, but fifteen years later this had increased to 21,500, with an additional 13,000 in neighboring San Juan.7

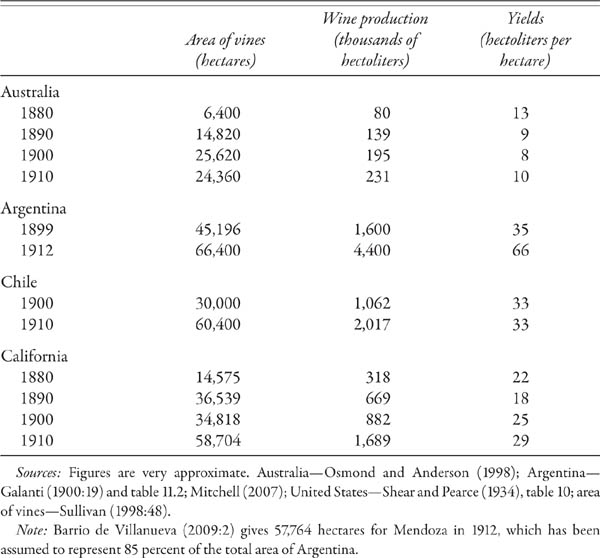

As in other regions of the New World, natural conditions were ideal: long hours of sunshine created grapes full of sucrose, and there was no phylloxera or other vine disease, with the exception of powdery mildew. Irrigation allowed yields that were considerably greater than those found in California or Australia (table 11.3). However, the need for irrigation implied that before 1885 most land was already owned by the provincial elite, who used sharecropping arrangements to plant and cultivate their vines.8 Because the local Creole labor force showed little interest in full-time employment in the vineyards, much of the labor was supplied by European immigrants, who planted the vines “in the same way as was done in their home country.”9 The obligations and rights stipulated in these contracts varied over time depending on the relative scarcity of labor and price of wine. Two contracts in particular were used: the contratistas de plantación (planting contracts) and the contratistas de viñas (cultivation contracts). With the planting contracts, the landowner provided the cuttings, work animals, and farm tools, and the sharecropper received a cash payment for each surviving vine that he had planted, together with the produce of the last harvest or two. Planting was relatively easy given the soft soil and irrigation and could be done with cheap plows and without the need for trenching.10 The lack of viticulture experience initially found among the landowners contrasted with that of the immigrants, and the latter often made the strategic decisions as to which grape varieties to plant or the spacing between vines.11

TABLE 11.2

Wine Production and Imports, Argentina, 1883–1912 (thousands of hectoliters)

By contrast, the cultivation contracts were annual contracts used in mature vineyards. They included a fixed cash payment that was paid monthly and a small share of the harvest, often no more than 5 percent. Jules Huret noted in 1913 that Domingo Tomba’s 200-hectare estate was worked in plots of 10–12 hectares per family, often of Chilean origin.12 With both contracts, families supplemented household income with a few sheep, pigs, chickens, and a small vegetable patch. By 1936, 35 percent of Mendoza’s vineyards and 68 percent of the vine area were cultivated using this type of contract.13

TABLE 11.3

Production and Yields in the New World

Sharecropping contracts allowed the traditional provincial elites to own large areas of vines, and the thirty leading landowners in Mendoza saw their holdings increase from 714 hectares in 1883 to 6,317 in 1900, equivalent to a third of the total area at both dates. However, as the contracts established before 1900 were made under conditions of labor shortages and high grape prices, immigrants enjoyed very favorable terms, and many saved enough to become owners themselves. Just as in the Midi, the creation of wine estates was therefore accompanied by a major increase in the number of small vineyards, and a total of 1,486 plots of vines (82 percent of the total) planted between 1886 and 1895 had less than 10 hectares, allowing a skilled part-time workforce to be available for employment on the large plantations and in the wineries.14

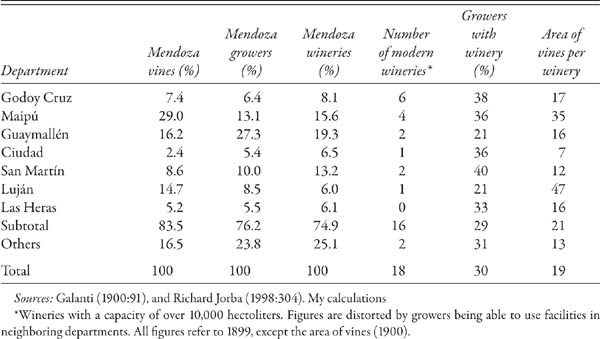

The average winery in Mendoza in 1900 received grapes from only 13 hectares of vines, although this increases to an average of 21 hectares when just the major producer regions are considered, and 47 hectares in the department of Luján (table 11.4). By contrast, 18 of the 1,082 wineries produced more than 10,000 hectoliters; in San Juan the figure was 7 of the province’s 612 wineries. In reality, the number of wineries that operated in any particular year fluctuated significantly, as growers preferred to sell their grapes to large wineries when prices were high but crushed them themselves when they had no buyers. Despite the presence of small wineries, a dozen or more dominated the industry, although the wine they produced was of poor quality and virtually all sold within the year.15 In 1899 the largest sixteen wineries (1.7 percent of the total), accounted for 39 percent of all the capital invested in Mendoza’s wineries, while in San Juan the extremes were even greater, with seven wineries (1.1 percent) accounting for 41 percent of the capital stock.16 Three years later the Tomba winery produced 91,250 hectoliters of wine (about 12 percent of Mendoza’s total, equivalent to approximately 1,500 hectares of vines in full production), the Giol y Gargantini winery produced 58,255 hectoliters, Arizu 57,022, and Barranquero, with two wineries, produced a total of 54,754 hectoliters. The leading ten wineries, eight of them were foreign owned, produced 445,137 hectoliters or a third of the province’s total.17 In the period 1908–10 winemakers bought almost three-fifths of their grapes from specialist growers, and by 1914 it was claimed that several wine-makers produced 160,000 hectoliters, four times more than the largest in France.18 Finally, foreign-born owners of vineyards increased from 29 percent of the total to 52 percent between 1895 and 1914, and from 28 percent of the wineries to 69 percent.19

Despite the favorable conditions for wine production, a rapidly growing labor supply, access to capital markets, and the presence of a dozen or more modern wineries, contemporaries were unanimous in their opinion of the poor quality of the work carried out in both vineyards and wineries. According to Pedro Arata, head of the 1903 commission that studied the industry: “The great majority of growers and winery owners believed that planting vines and making wine was like buying cows and bulls, turning them out into a field and selling immediately the calves, and leaving it all to Nature as is done in the Province of Buenos Aires.”20

Arata’s negative comments have been widely quoted by historians, but one obvious explanation for his bitter criticism is that his report was made at the depths of a major recession. Grape prices fell to levels that barely covered growers’ variable production costs, so that only the most important tasks were carried out in the vineyard, and yields were kept high by excessive irrigation. The 1903 commission also noted that the short-term nature of sharecropping contracts encouraged the contratistas to maximize output, without considering the longterm consequences for the vine.21 In addition, workers were often slow to switch from planting and pruning methods that were suitable to their native wine- producing regions to those needed for the rich, irrigated soils of Mendoza and San Juan.22 Growers planted “French varieties,” in particular malbec, cabernet (sauvignon and gros cabernet), sémillon, and pinots, so that by 1903 only 26 percent of the area of vines comprised the old criollas. However, the canes brought from Chile because of the ban on vines from phylloxera-affected Europe led to large numbers of sterile plants and low yields.23

TABLE 11.4

Size of Wineries in Mendoza, circa 1900

Harvesting also left much to be desired because unskilled labor was paid by piecework, resulting in no attempt to select the most suitable fruit or separate the grapes properly from the stems and leaves. There were also other problems peculiar to the region. The French geographer Pierre Denis noted that the dryness of the atmosphere caused ripe grapes to remain longer on the vine without any harm, and a longer harvest reduced the number of migrant workers required and allowed growers to cultivate a larger area.24 Indeed, the huge size of some of the wineries can only be explained by the possibility of stretching the harvest over three or four months.25 Grapes that remained on the vine for this length of time, rather than for a month or six weeks, lost moisture and weight but gained in sugar content. This encouraged growers to overirrigate and benefited the winery owners, who bought the grapes by weight and added water to the must to reduce the alcoholic strength from 16 to 12 degrees.26 It did little to improve wine quality.

Arata’s report criticized the unscientific nature of wine making that often took place in unhygienic conditions. The addition of tartaric acid to the must was limited by its cost, and despite abundant supplies of cold water very few wineries had invested in cooling equipment.27 Yet the government enquiry of 1903 also noted that large amounts of capital invested in winery equipment had been wasted because producers “forgot” the basics of production and conservation of sound wines.28 Most contemporaries were unanimous in their condemnation of the poor quality of the vast majority of wines at the turn of the twentieth century, but they were also divided as to whether this was caused by the lack of wine-making skills or by the nature of market demand. Consumers drank red wines almost exclusively—wines that were “very dense, with lots of color, a high alcoholic strength and rich in dry extract.” Water was almost always added; the question was who along the commodity chain added it.

REDEFINING THE INDUSTRY

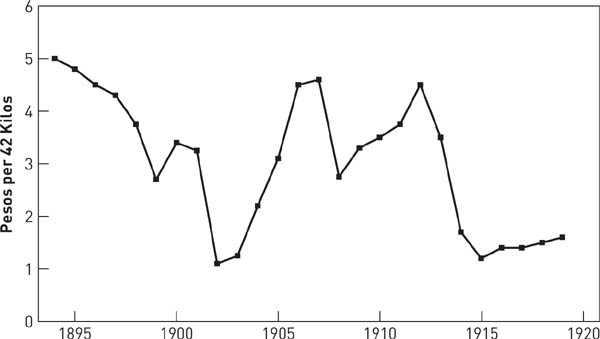

Elías Villanueva, Mendoza’s provincial governor and eleventh largest wine producer, argued in 1902 that the crisis occurred not because wine quality had suddenly deteriorated, but because merchants lacked money to make purchases, and wine was an expenditure that many consumers reduced at times of financial difficulties.29 The high profits of the 1890s had encouraged growers and winery owners to go heavily into debt, and after 1901 they faced a credit squeeze brought about by a sharp contraction of foreign investment and outflow of gold to cover the trade deficit. Grapes, which had sold for around 3.4 pesos per 46 kilos in 1900 and 3.25 in 1901, fell to 1.1 pesos in 1902 and 1.25 in 1903 (fig. 11.1). Wine prices also declined, though by less.30 Among the numerous casualties of the crisis was the family firm Benegas e Hijos, perhaps Mendoza’s best-known wine producer, which was forced to offer shares in the company to its main creditors in order to remain in business.31

Figure 11.1. Grape prices in Mendoza, 1893–1920. Sources: Suárez (1914: Estadística) and (1922:viii)

Although short-lived, the crisis highlighted a number of structural problems facing the industry. As in other countries, the poor quality of many wines made adulteration easy and especially attractive when prices were high. Wine producers demanded a national law to protect their product and which would be enforced. An additional problem in Mendoza was that the large wineries reacted to the decline in demand by refusing to buy the grapes of small producers. These were therefore forced to open their old cellars and sell the wine immediately after fermentation because of their lack of storage capacity and limited access to credit, all of which contributed to the “discredit of the product” and falling prices because of the excess of supply. Weather conditions also made wine making especially difficult in 1902, and the lack of buyers led to large amounts of wine being left to spoil in the large wineries’ cellars.32

Four groups were deeply affected by the crisis: the Mendoza provincial government, which depended heavily on the sector for taxes; the banks, which had large quantities of nonperforming loans; the large wineries, with their unsold stocks; and the growers, who risked being left with grapes that they could not sell. On the eve of the 1903 harvest, an attempt at an agreement between the large producers, bankers, and “a few growers” to rent wine-making facilities and cellar space to the small producers so they would not dump poor quality wines on a saturated market, as had been done in 1902, was ridiculed in the local press for shifting all the adjustment costs onto the grape growers. The leading regional newspaper, Los Andes, called on all groups to make sacrifices, but this was limited to controlling adulteration.33

As in other wine districts at this time, many contemporaries believed that the real cause of the crisis was underconsumption, which was blamed on the poor quality of wine and widespread adulteration found along the entire commodity chain. A national law of 1893 permitted the sale of wines made from raisins, fermented pomace (petiot), or other products, but these had to be clearly labeled as such and paid higher taxes than “natural” wines.34 Mendoza’s provincial law of 1897, by contrast, prohibited the production of all wines made from substances other than fresh grapes, while that of 1902 doubled taxes on red wine with less than 26 per 1000 dry extract to stop producers watering down their wines. The real challenge, as everywhere, was enforcement, which implied creating some independent entity that could legally check what was happening in winemakers’ and merchants’ cellars. The collapse in wine prices in 1902, the abysmal quality of the wines that year, and the threat by some politicians in Buenos Aires to reduce tariffs on Chilean wine imports pushed the large producers and local government into action. Villanueva was successful in getting the Ministerio de Agricultura de la Nación to create the previously mentioned national commission headed by Pedro Arata to investigate the industry’s problems, and this included provisions for inspecting wine cellars as well as destroying diseased and adulterated wines. The commission soon faced local opposition to its work. The newspaper Los Andes complained that the large winery owners were quick to applaud the activities of the commission when it removed poor-quality wines from small producers’ cellars but placed legal obstacles to it entering their own.35 In particular, the manager of Governor Villanueva’s own winery refused permission for the destruction of 1,000 hectoliters of spoiled wine, and it required a second visit by the commission, when some 500 hectoliters were finally removed.36

A new national wine law was passed in 1904 (Ley Nacional de Vinos, no. 4363) which defined wine as being made only from fresh grape juice, with certain enological exceptions, such as the addition of tartaric or citric acid. Red wines had to contain between 24 and 35 per 1,000 dry extract (white wines less than 17 percent), and imported wines had to be sold in their original casks, with certificates proving the place of origin. The only activities permitted in a winery now were the manufacture of wine, distilling of wines and pomace, and refining of spirits. The making of artificial wines from raisins and pomace had to take place in establishments other than wineries and was strictly controlled. Finally, wines that had become spoiled and diseased had to be destroyed.37

As in other countries, the law reflected local conditions and the interests of certain groups within the industry. Imported table wines were strong in alcohol and high in extract as they were mainly blended with domestic wines, and the new law discriminated against them. The maximum 35 per 1,000 in extract permitted in domestically produced red wines was to discourage the watering down of wines before sale, and the minimum level was to encourage the production of wines that could compete with imports.

The Centro Vitivinícola de Mendoza was created in 1904, in part as a response to fraud, and it merged the following year with the Sociedad de defensa vitivinícola nacional, a similar organization of wine merchants in Buenos Aires, to form the Centro vitivinícola nacional (CVN), based in the capital. This geographic shift on the part of Mendoza’s largest producers was caused by a convergence of interests between themselves and the capital’s leading wine merchants, as imports declined from around a quarter of consumption in 1900 to a tenth by 1912.38 To control fraud the CVN paid the federal government for five new sub-inspectors, which led to a number of prosecutions.39

Unlike European countries, a high share of Argentina’s production was located in a small geographical area, and industrial concentration was exceptionally high. Mendoza accounted for four-fifths of the nation’s production in 1902–3, and just twelve producers (who enjoyed close links with the provincial government) produced a third of the total.40 The industry contributed as much as a half of the province’s tax revenue and 60 percent of Mendoza’s gross industrial output as late as 1914.41 The problems of 1901–3 led the provincial government to consider the need to control wine adulteration to protect its revenue base as well as to use government funds to diversify the local economy and reduce its dependence on the sector. The arrival of Emilio Civit as governor in 1907 marked a turning point and led to conflicts between politicians and the leading wineries.42 In 1907 the Dirección de Industria was created to provide technical assistance to the sector, and within this institution the Oficina Química had the responsibility for inspecting wineries and the capacity to levy fines and destroy wine that was deemed as illegal. All wine-making facilities had to be registered (those unregistered were considered illegal), and every building where wine was made, stored, or sold was liable to surprise inspections. The first director was Enrique Taulis, who as a Chilean was supposed to provide an element of impartiality. Fines, which totaled $166,177 in 1908, rose to $388,883 two years later, provoking fierce opposition from some of the large producers.43

The control of fraud was highly controversial and depended on the continued vigilance of government inspectors, paid for by an often reluctant industry. Los Andes in October 1909, for example, criticized “the almost complete lack of vigilance” of the retail trade in Mendoza, in part because of the inept government controls, but also because of the “favors” shown toward some owners who were friends of “politicians.”44 Writers closer to the large wineries thought otherwise, and one considered government enforcement as bordering on being excessive.45 A tribunal consisting of the leading winery owners was established when Taulis was forced to resign after fierce opposition from the sector, and fines fell in 1912 and 1913 to 5 percent of the 1908 level.46 Although some artificial wines inevitably continued to be produced, they had ceased to be the industry’s major concern by 1910.

The extreme difficulties facing the industry between 1901 and 1903 encouraged large producers to propose changes that went beyond just controlling adulteration. The first initiative was in November 1901 when Tiburcio Benegas suggested the creation of a trust whereby each member placed 5 percent of their wine in a new company in exchange for shares. By this system, the industry’s leaders hoped not just to limit supply, but also to preserve their control of the industry. While the Benegas project originated from within the sector, that of Elías Villaverde the following year came from the provincial government and involved greater state involvement. The proposal consisted of using funds raised by new production and sales taxes on wine to improve quality by investing in better equipment and scientific skills. Finally, Horacio Falco, a highly influential member among the leading producers, returned from Europe with a “project to save the industry” in 1903, which turned out to be little more than another attempt by the large wineries to create a company that they themselves controlled, to restrict supplies by buying up surplus wine when necessary.47

There were several major obstacles to the creation of a wine trust such as the California Wine Association, and the Mendocino newspaper Los Andes described the local attempts as both “ridiculous” and “impossible.”48 Unlike California (or Australia), wine was the national drink, and therefore any suspicion of a Mendoza cartel creating monopoly prices led to politicians in Buenos Aires demanding imports from Chile or elsewhere.49 The low quality of much of the wine also implied that a trust that did not include all the major wineries would suffer from problems associated with free riders—independent producers who did not contribute to the costs of regulating the market but increased their output to take advantage of higher prices. By the autumn of 1903 the promise of better grape and wine prices following the February harvest ended the debates among major producers who had been proposing collusion or a trust.

The low prices and problems of finding wineries willing to purchase their grapes also left small growers reflecting on the need to create cooperatives. In 1903, at the depth of the depression, a number of growers proposed a “sindicato” to tackle specific problems facing the industry, including transport, marketing, and the shortage of wine-making equipment. It was neither a genuine producer cooperative nor a trust, and interest quickly faded. A short-lived cooperative, the Helvecia winery in Maipú, appeared in 1903.50 When Leopold Mabilleau, director of the Social Museum in Paris, spoke in Mendoza in 1912, he explained the need to overcome excessive individualism and advocated a collectivist approach to problems, noting the success of French farmers in creating cooperatives.51 However, in France, as shown in chapter 3, the state responded positively to demands by small farmers, especially by providing access to capital markets, which favored the creation of producer cooperatives. In Mendoza it was the interests of the large wine producers that the provincial government responded to, and these were reluctant to see small growers form cooperatives that might threaten their supplies of grapes.

The industry’s problems were resolved by the renewal of massive capital imports and immigration, leading to the Argentina’s economy growing at an annual 7 percent between 1903 and 1913.52 Demand for wine also increased dramatically. The area of vines grew from 22,875 hectares in 1904 to 57,764 hectares in 1912; wine output jumped from 1.1 million hectoliters to 3.5 million; imports declined from a million hectoliters to half a million; and annual per capita consumption increased from 41 liters to 72 liters (1913).53 Capital investment was used to modernize and raise winery capacity, rather than increase the number of firms, so that while the 1,064 bodegas producing less than 10,000 hectoliters in Mendoza in 1899 fell to 956 in 1910–14, those above this figure increased from 18 wineries in 1899 to 60 in 1910, 76 in 1912, and 96 in 1914, by which time the three largest bodegas produced a total of 350,000 hectoliters and required grapes from around 6,000 hectares.54

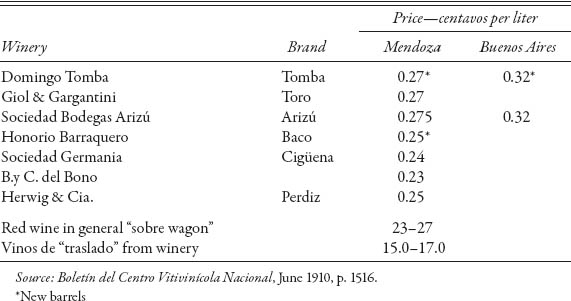

As elsewhere in the New World, major winery investment reduced production costs by saving expensive labor, as well as capturing the economies of scale that could be achieved by building wineries on green-field sites. The hot, dry climates produced grapes of high quality, and scientific wine-making processes and selective blending in theory now allowed a wine to be produced in large quantities and of a consistent and better quality from one year to the next that could be branded. A handful of firms, including Benegas and López, had begun to do just this in the final year or two of the nineteenth century, and the number increased to thirty-six brand names during the first decade of the new century.55 The result was that a much greater percentage of ordinary commodity wine was sold under producer brand names in Buenos Aires than in Paris or Madrid (table 11.5). While contemporaries had been highly critical of the diversity of wine produced in Mendoza because of the poor wine-making conditions at the turn of the century, a decade later they bemoaned the fact that there was little to distinguish between the output of the largest producers, in part because of the widespread use of the malbec variety.56 This uniformity, and perhaps collusion between the leading producers, led to minimal price differences for their wines (table 11.5). As most consumers were of Mediterranean extraction, the demand was for a strong, alcoholic wine, which was then watered down, for both taste and economy. The only guarantee that a brand offered in these conditions was that it would be the consumer, rather than an intermediary, who added the water. Migrant labor (golondrinas) did not drink branded wine in Italy, and they were unwilling to pay a premium for it in Argentina. This uniformity and low quality of wine is also shown by the fact that it sold for only a third more than the vinos de traslado, wines produced by independent growers in small wineries and sold immediately after fermentation to be blended with the produce of the big houses to meet their orders. In this way, the large wineries were able to adjust their supply to meet demand for their branded wines in the final market. However, when the big producers stopped buying as prices fell after 1914, these wines were sold directly to dealers in Buenos Aires, forcing down the prices of all wines, branded and unbranded.

TABLE 11.5

Selected Wine Prices and Brand Names, June 1910

By the first decade of the twentieth century contemporaries such as José Trianes and José Alazraqui were aware of the important differences between the Argentine and European wine industry.57 Yet while the production and commerce of cheap wines were more vertically integrated in Argentina than in Europe, they were less so than in California and probably in Australia. Wine quality undoubtedly improved in the decade after 1901, but because consumers were primarily interested in price, there were no financial incentives to improve quality to the levels found in either Australia or California, where producers had to create new markets among consumers unaccustomed to drinking wines. The attempts to establish competitions and adjudicate prizes for the best wines, for example, came much later and appear to have created little consumer interest.58 Mendoza’s wine industry before 1914 lacked figures of the stature of Eugene Hilgard and George Husmann in California, or Thomas Hardy and Arthur Perkins in South Australia. Highly observant commentators such as Pedro Arata and Amerino Galanti were not involved in wine making, while the influence of people such as Aaron Pavlovsky, Paul Pacottet, or Leopoldo Suárez was limited, at least prior to 1914.59 The wine-making experiments, especially those of Algeria, Australia, and California, were rarely mentioned in the local wine press. This can be explained by the fact that immigrants still looked to their origins for solutions: Italy (and especially the Scuola di Viticoltura e di Enologia in Conegliano in Treviso), France (essentially Bordeaux), and Spain. In addition, market incentives and local investment devoted to scientific research were simply not considered necessary by the industry. Wineries sold all they could produce in times of high demand, and when prices collapsed they simply reduced their grape (and wine) purchases from small producers and looked to the provincial government for a solution.

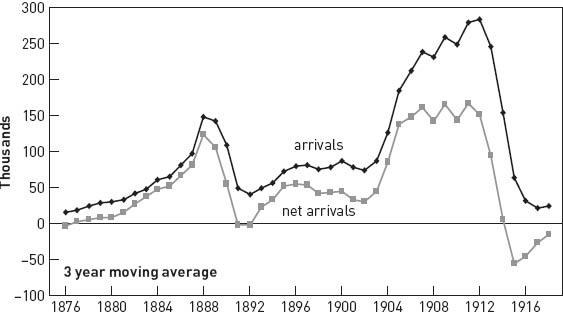

Figure 11.2. Argentine immigration, 1875–77 to 1917–19. Source: Mitchell (2007:105–6)

THE LIMITS TO GROWTH AND THE RETURN TO CRISIS

The rapid growth of the Argentine economy was brought to a sudden halt when GDP collapsed by 10 percent in 1914 as financial problems in London provoked a repatriation of capital, creating an economic depression that lasted until the end of 1917.60 Growers who had sold their grapes for 4.5 and 3.5 pesos a quintal (42 kilos) in 1912 and 1913 had to accept just 1.7 and 1.2 pesos in 1914 and 1915 (fig. 11.1). Against a background of credit shortages, contemporaries once more reflected on the industry’s shortcomings. As the Boletín del Centro Vitivinícola Nacional noted in January 1914: “only at critical moments . . . does the sector worry about its collective interests and then, as if woken from a dream concerning its own grandeur, it agitates madly to find a way to return to tranquility . . . and sleep once more.”61

TABLE 11.6

Availability and Consumption of Wines in Various Countries, 1909–13 (liters per capita)

One explanation given by some contemporaries for the crisis was the lack of demand for wines. Movements in consumption and immigration were closely linked, and the sharp decline in arrivals after 1914 affected sales (fig. 11.2). In 1869, when the foreign population numbered 12 percent, per capita consumption was 23 liters per year; by 1895 the foreign population was 21.5 percent and per capita consumption had risen to 32 liters; finally, by 1914, 30 percent of the Argentina’s population was foreign born and wine consumption reached 62 liters per head (table 11.6).62 The fact that this was less than half the figure in France, despite Argentina’s high wages, led some to argue that the problem was not overproduction but rather underconsumption, and that the difference could be attributed to the presence of greater adulteration.63

The income elasticity of wine is difficult to measure, but there was a tendency for French per capita consumption to increase with living standards, at least until the First World War. Yet a simple link between higher wages and wine consumption is deceptive, as wine was traditionally drunk much more in regions of production than in areas where the vine was absent. In France wine consumption was common over comparatively large areas of the country, but some regions, such as Brittany, produced and consumed very little wine. Per capita consumption in both Spain and Italy was lower than in France, in part because the vine was absent in a greater number of regions where there was no wine-drinking tradition. The fact that in the period 1885–95 almost two-thirds of Spanish emigrants to Argentina left from Galicia and Asturias—regions that accounted for 14 percent of Spain’s population but less than 2 percent of its vines and wine production—inevitably restricted demand.64 This also helps to explain why, with a few notable exceptions, such as Balbino Arizu, Miguel Escorihuela, and José Gregorio López, Spaniards in Mendoza’s wine industry were significantly less important than Italians.65 Yet even in Italy, the major source of immigrants before 1900 was Veneto, a region responsible for 4 percent of Italy’s wine, although by 1900 Sicily, a major southern wine producer, had become equally important.66 Immigrants from regions such as Galicia or Veneto inevitably limited the potential wine market in Argentina.67

Market volatility was common in all wine regions because high prices encouraged the planting of vineyards that would become productive only three or four years later, when market conditions might be very different. The rapid increase in output in Argentina after 1910 can thus be partly explained by the high grape prices of 1906 and 1907, while the high prices between 1909 and 1912 increased supply after 1913 and 1914.68 Volatility was greater in Argentina, however, in part because it operated under New World production conditions, with specialist growers and rapid population growth, and in part because it sold in a market with European characteristics, where wine was considered a basic consumption item, and therefore the Buenos Aires government would not tolerate price manipulation by producers.

The high fixed costs along the commodity chain implied that wine prices in Buenos Aires fluctuated much less than grape prices in Mendoza, which could double or halve from one harvest to the next.69 Pedro Arata estimated that when the price of grapes in Mendoza was three and half centavos a quintal (46 kilos), wine cost 23.7 centavos a liter in Buenos Aires, but when grapes fell by 70 percent, wine prices fell by only 35 percent (table 11.7). Retailers purchased wine only at prices at which they could make a profit, grapes were bought by wineries if producers believed they could sell the wine, but grapes were always collected and crushed in primitive wineries if the growers believed that the wine could be sold at a price above the immediate cost of harvesting and fermentation.70

TABLE 11.7

Correlation between Grape Prices and Wine Prices

Grape price in Mendoza |

Wine price in Buenos Aires |

3.50 pesos @ 42 kilos |

23.7 centavos per liter |

3.00 |

22.0 |

2.50 |

20.4 |

2.00 |

18.7 |

1.50 |

17 |

1.00 |

15.4 |

Source: Arata (1903:204).

In Mendoza the creation of new vineyards required relatively little capital, and the use of planting contracts allowed landowners to increase their area of vines without even having to pay wages. Small holders could plant vines on their own land by working during periods of low seasonal demand for wage labor. By contrast, the high capital cost of the new wineries implied that investment in new facilities was linked to the availability of credit and when producers could be sure of being able to sell their wines at a sufficiently high price in Buenos Aires to cover their production costs. This separate ownership of vines and wine-making facilities led to an unbalanced growth between the two sectors because when large wineries failed to purchase grapes from independent producers, aggregate supply was not diminished. As noted with the 1901–3 downturn, an important number of wineries reopened and producers dumped their young wines in the market.71 The same was true in 1914, when an additional seven hundred wineries opened compared with the previous year, and when the large wineries refused to buy the vino de traslado the producers sold it directly in the major markets at important discounts in relation to the branded items.72 Belated attempts at collective action on the part of the leading producers to purchase these wines failed because few were actually willing to commit themselves and buy, so prices remained a third lower than the previous year in the principal markets.

Specialist grape producers in both Australia and California had greater negotiating strength and market instability probably was less than in Argentina.73 This was because of the better-quality table wines produced there, and consequently the need for winemakers to guarantee a supply of high-quality grapes when markets recovered. In addition, grape producers in general enjoyed more dynamic labor markets in the large, diverse local economies of San Francisco and Melbourne than growers did in Mendoza, which was a thousand kilometers from Buenos Aires. If winemakers refused to buy their grapes, growers could exit the industry. The absence of a large urban center nearby on the scale of San Francisco or Melbourne also made it harder for Mendoza’s growers to sell their surplus grapes for the table, although small amounts began to be sent to Buenos Aires in 1903.74 In their favor, although the size of family vineyards was similar to that of other New World producers, yields in Mendoza were significantly greater because of irrigation (table 11.3), and before 1914 market downturns were short, so that many growers carried low levels of debt.75 Those growers in Mendoza and San Juan who were contracted to large producers were also partly protected because as contratistas they received a fixed salary, even though Pedro Arata reported labor leaving the region in 1903.76

The response by Mendoza’s leading wineries to the cyclical downturns was clear: the costs of adjustment should be borne by other sectors. In Europe, producers reacted to overproduction by demanding that “surplus” wine be removed from the market to bring supply and demand back into equilibrium at previous price levels. However, in the New World this was harder to achieve because any recovery in wine prices would immediately lead to a renewed growth in planting vineyards by specialist growers, and an even greater overproduction a few years later. To resolve this problem, Mendoza’s leading wineries colluded to keep grape prices artificially low, at a little more than a peso per 42 kilos between 1914 and 1919 (fig. 11.1). This was hardly enough to cover variable production costs in the vineyards, but it significantly reduced the incentives to increase the supply of grapes by new plantings.77

In the wider Argentine economy, as in the United States, industrial supply “moved toward ‘trustification,’ . . . capital concentration and big business” during the first decade of the twentieth century.78 While there is plenty of evidence that the large wine producers colluded to restrict competition in their grape purchases, there is little to suggest that a trust such as the California Wine Association was ever seriously considered. As Mendoza’s leading daily newspaper, Los Andes, noted in 1903, the large producers found it more attractive to capture tax revenue from the provincial government, which they could use to regulate supply, than to invest their own money in risky enterprises.79 The Mendoza law of 1916 (ley 703) in particular created a cooperative that allowed the leading wineries to use public funds to remove from the market unwanted wine. Past attempts to create similar voluntary organizations had failed because insufficient producers were willing to participate, so a punitive tax was now levied on the production of those who remained outside the scheme.80 The cooperative was run by the large wineries and from the start was highly controversial. Its life proved short, as Argentina’s Supreme Court determined it to be unconstitutional, ruling that a provincial government could not create a private monopoly.

The failure of the Argentine industry to improve wine quality was criticized by contemporaries and historians alike.81 Much of the wine was of poor quality, adulteration was common prior to 1903 if not later, and advances in wine making were slow compared with those found in other regions with hot climates, such as Algeria and Australia. Interest in improvements occurred only at times of major market disruptions, and even then more time and energy were given to discussing attempts at market regulation than scientific progress. Yet it was also equally true that not only had a dozen or more wine producers become very rich, but considerable wealth had also filtered down the industry, so much so that a grower in 1912 with 50 hectares of vines was considered sufficiently wealthy to enjoy a box seat at the Colón opera house in Buenos Aires.82

These two visions of the industry were perfectly compatible. Many regarded as fanciful the suggestions that the industry should start exporting wine during the downturn after 1914. According to the Centro vitivinícola nacional in its album to celebrate the country’s centenary in 1910, about 95 percent of Argentina’s wine production was vin ordinaire, and the remaining 5 percent of better quality was blended with imports and then sold under foreign labels.83 Prosperity was found in making cheap wines in large quantities, not small quantities of fine wine, and Mendoza’s spectacular growth was based on the demand for cheap, strong, red wines to be consumed with water. This fact alone explains the limited interest in state investment in specialist research institutions and the lack of curiosity by winemakers in the new technologies being developed elsewhere. While companies such as Penfold and Hardy were shipping unfortified table wines from Australia to England, producers in Mendoza were discussing whether it was possible for such wines to survive the journey to Buenos Aires.84 Wine quality did improve over the 1900s, but producers still expected to sell the vast majority of their wines during the year of production, unlike in Australia, where wines spent about nineteen months maturing before export.

In Europe wineries were limited in size, partly by the need to crush large quantities of grapes quickly before they deteriorated. This particular restriction was absent in Mendoza as the harvest was allowed to stretch over three or four months, and the result was some of the world’s largest wineries, who depended on specialist growers for large quantities of their grapes. Yet the coordination mechanisms between specialist growers and independent industrial wineries were far from perfect. Grape prices were strong most years before 1914, but the specialist growers were forced to maintain basic wine-making facilities for those times when the wineries failed to buy their grapes and wines, such as occurred in 1902 and 1914. The system benefited the large wineries as they did not have to buy unwanted grapes and wine at times of weak demand, but it failed to stop the small producers flooding the Buenos Aires market with cheap wines that had barely finished fermenting. Industrial wineries now found that consumers showed little brand loyalty, and the price of all wines was dragged down. By contrast, the small growers, despite frequent support by the local press, failed to get the necessary political backing before 1914 to create some form of cooperative or a “Mendoza” brand, as this was opposed by the large producers, who feared that it would threaten the flexibility they enjoyed in the grape and wine markets.

Finally, the high level of dependence of the Mendoza provincial government on the sector proved in time to be a double-edged sword. Although many of the governors were themselves wine producers, the importance of wine as a source of revenue encouraged the government to attempt to diversify away from the crop. Wine was often taxed, which raised costs and, between 1912–14 and 1930–34, contributed to the decline of Mendoza’s share of national production from 82 percent to 70 percent.85 Crucially the sector was also dependent on other provinces and especially Buenos Aires for its markets. National politicians threatened to reduce import taxes when they thought that Mendoza’s producers were colluding or quality deteriorated because of fraud. Wine in Argentina was a basic necessity, and a cheap and plentiful supply for the urban middle and lower classes would be a centerpiece of Peronismo.86

1 Williamson (1995).

2 Rock (1993:114); Gallo (1993:83–84). The population of Madrid in 1910 was 600,000; Rome, 543,000; and Paris, 2.9 million (Mitchell 1992:73–74).

3 By 1914 Mendoza and neighboring San Juan accounted for 98 percent of the country’s wine, of which 95 percent was consumed outside these two provinces. Boletín del Centro Vitivinícola Nacional, June 1915, p. 156; Centro Vitivinícola Nacional (1910:17). For population, Mitchell (2007:38).

4 Population figures are for 1869. Small quantities of wine were sold to the coastal region in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, but trade slowed with independence and the civil wars and anarchy that followed. See Rivera Medina (2006) and Coria López (2006).

5 Blanco (1870:15), cited in Richard Jorba (2008:7).

6 Richard Jorba (2006:77–81). Tax relief was given only if there was a minimum of 1,260 vines per hectare. Official attempts to recruit labor had limited success but were unnecessary after 1885.

7 Together these two provinces had 76 percent of the country’s vines in 1899 and produced 85 percent of the wine in terms of volume and 87 percent in terms of value (Galanti 1900, appendix). The two provinces had 83 percent of the capital invested in vineyards and 93 percent in bodegas.

8 Mendoza and San Juan are oases in the desert, with little more than 80,000 hectares cultivated (or around 3 percent of the region) in Mendoza, and 70,000 hectares in San Juan in the late nineteenth century (Richard Jorba 2006:24).

9 Pacottet (1911:viii).

10 Simois and Lavenir (1903:117). Richard Jorba (2007), in a study of twenty-six contracts, found that 65 percent of tenants were Italian, 19 percent French, and the rest probably Spanish.

11 Richard Jorba (2007:180).

12 Huret (1913:229). This seems large. Suárez (1922:xi) argued that it has been demonstrated that a worker could cultivate 6 hectares a year. However, the area obviously also reflects family size.

13 Salvatore (1986:232).

14 Richard Jorba (1994, cuadro 3). A total of 886 plots had less than 2 hectares, and 1,211 had less than 5 hectares. In 1919 there were 2,940 properties of less than 5 hectares; 1,078 between 5 and 10; 745 between 10 and 20; 535 between 20 and 50; 171 between 50 and 100; and 84 of more than 100 hectares (Suárez 1922:x).

15 Kaerger (1901), cited in Barrio de Villanueva (2009:16). See also Simois and Lavenir (1903: 127) and Arata (1903:202).

16 Galanti (1900:92, 136), my calculations. These wineries had a minimal capacity of 10,000 hectoliters. The average in Mendoza was 463,000 pesos, and in San Juan, 346,000 pesos.

17 Barrio de Villanueva (2008b, cuadro 1). They used electricity or steam power.

18 Centro Vitivinícola Nacional (1910:17); La Prensa, April 24, 1914, p. 12.

19 Salvatore (1986:233). The number of foreigners in Argentina was 30 percent of the total population in 1910.

20 Arata (1903:192). For the commission, see below.

21 Simois and Lavenir (1903:120). For a wider discussion on the incentive structures and contracts in viticulture, see Carmona and Simpson (1999:292–94) and Carmona and Simpson (forthcoming).

22 Richard Jorba (2006:114–15); Simois and Lavenir (1903:120); and Arata (1904:147).

23 Simois and Lavenir (1903:118, 123–24).

24 It also encouraged a trade in grapes. Denis (1922:86–87) noted that in Mendoza there was “a division of labor which seems to the European visitor as strange as the climate which partly explains it.”

25 The 1908 harvest, for example, stretched from mid-February to the end of May. The largest winery, Tomba, crushed some grapes in vats of 50 hectoliters, which were brought by rail to the winery with the wine fermenting (Pacottet 1911:78, 82).

26 Simois and Lavenir (1903:126); La Prensa, April 8, 1914, p. 12.

27 As in other regions with hot climates, the major difficulties were the lack of acidity in the must and the high temperatures produced in the fermenting vats, caused not just by climatic conditions, but also by the high sugar content of the grapes. A number of wineries had purchased Müntz and Rousseaux cooling systems, but these were considered expensive and were designed for small wineries where water was scarce (Simois and Lavenir 1903:130–35).

28 Ibid., 128. A major problem was that equipment was often imported and more appropriate to Europe’s wine regions than Mendoza’s.

29 El Comercio, October 22, 1902, p. 2, cited in Barrio de Villanueva (2008a:339). GDP shrunk 2 percent in 1902 but recovered quickly the following year (Sturzenegger and Moya 2003:114).

30 Arata (1903:253).

31 Barrio de Villanueva (2005:46–56).

32 Simois and Lavenir (1903:127, 143) noted that “mannite affected wines were in abundance in 1902.”

33 Los Andes, January 17, 1903, p. 4.

34 Balán (1978:76–77).

35 Los Andes, March 17, 1903, p. 4).

36 See especially Barrio de Villanueva (2008a:336).

37 Barrio de Villanueva (2007:7–9). Fine wines that had been bottled were exempt from these restrictions on extracto seco.

38 Market control was fragmented in Buenos Aires between those merchants who dealt with imported wines (which were blended with domestic or artificial wines) and those who depended exclusively on domestic supplies.

39 Barrio de Villanueva (2006:200).

40 Table 11.2 and Barrio de Villanueva (2008b:89).

41 Richard Jorba (2008:7), who writes that viticulture allowed the province “an important degree of independence” with respect to the federal government; and Coria López (2008, anexo viii). Local industries were developed to supply the sector. See especially Pérez Romagnoli (2006).

42 Barrio de Villanueva (2006:210–12).

43 Bottaro (1917).

44 Los Andes, October 7, 1909.

45 Alazraqui (1911:90). Taulis, who was responsible for control in Mendoza, suggested that fraud accounted for only 15 percent of consumption, with most occurring in Buenos Aires (Boletín del Centro Vitivinícola Nacional, June 1909, p. 1155).

46 Bottaro (1917); La Prensa, April 6, 1914, p. 8.

47 These projects are described in greater detail in Barrio de Villanueva (2006:190–98) and Mateu (2007:14–15).

48 Los Andes, August 1901, p. 4.

49 The Buenos Aires newspaper La Nación warned of the dangers of a cooperative organized by speculators among wine producers, which claimed to protect the interests of the industry, consumers, and government. Cited in Los Andes, January 15, 1903.

50 Mateu (2007:15).

51 La Tarde, September 18, 1912, cited in ibid., 13.

52 Sturzenegger and Moya (2003:114).

53 Barrio de Villanueva (2009:1).

54 Figures refer to 1910, 1912, and 1914. As noted above, the number of wineries that operated in each year varied. The provincial governor in 1910 noted that 910 wineries used modern methods, and only 250 traditional ones. See Barrio de Villanueva (2009:5–7).

55 Barrio de Villanueva (2003:39, 42); Richard Jorba (1998:306). One of the functions of the CVN was to facilitate registration of brands by producers.

56 Galanti (1900:26–27); Simois and Lavenir (1903:200); Galanti (1915:34); and Boletín del Centro Vitivinícola National, December 1910, p. 1671. For the 1930s, see Trianes (1935:37).

57 Trianes (1908:26) quote at the beginning of this chapter; and Alazraqui (1911:85), who noted that winemakers assumed many of the merchants’ functions.

58 Barrio de Villanueva (2003).

59 Pacottet was an agronomist and head of viticultural research at the Institut National de France and author of a number of works on grape and wine production; Pavlovsky directed Mendoza’s Escuela de Agricultura and was a winery owner.

60 Sturzenegger and Moya (2003:93); Rock (1993:141–42).

61 Boletín del Centro Vitivinícola Nacional, January 1914, p. 2757.

62 Bunge (1929:128). Per capita consumption refers to the years 1895–99 and 1910–14.

63 La Prensa, April 17, 1914, p. 12, for example, claimed, but without supporting evidence, that annual consumption was actually 140 liters per person, including adulterated wines.

64 Sánchez Alonso (1992:89; 1995:292–93); and Simpson (1985a:359–60). Figures for wine refer to 1889. Catalonia was the only region that supplied a significant number of emigrants (12 percent) and was a major wine region (22 percent of vines). In later years both Alicante and Almeria, traditionally wine-importing provinces, would have high levels of emigration, but to Algeria and France rather than Argentina.

65 Arizu originated from Unzué (Navarra), Escorihuela from Tronchón (Teruel), and López from Algarobo (Malaga). See especially Mateu (2009); Bragoni (2008). For the presence of Spanish as contratistas, see note 10 above.

66 Devoto (2004:100). Sicily produced 15 percent of Italy’s wine in 1895–99 (Mondini 1900:31).

67 Ramon Muñoz (2009) makes a similar point for olive oil exports.

68 An exact fit is difficult to establish, however, because annual production fluctuated for a variety of reasons. In Mendoza estimates of the area under vines are very inexact, and it is not possible to know to what extent the official statistics include young, unproductive vines. See especially Suárez (1922:56) and La Prensa, April 14, 1914, which complained that in Mendoza “it costs less to plant vines than count them.”

69 La Prensa, April 12, 1914, p. 11.

70 It was widely believed that prices were imposed on the grower by the large wineries. Ibid., April 6, 1914, p. 9; April 10, 1914, p. 9.

71 There were reportedly 1,742 wineries in operation in 1902 compared with 1,082 in 1899 and 1,010 in 1907 (Barrio de Villanueva 2009, cuadro 6).

72 La Prensa, April 10, 1914, p. 9.

73 In California the CWA provided stability. The demand for wine depots suggests, however, that the problem was also present, although to a lesser extent, in South Australia and Victoria.

74 Barrio de Villanueva (2008a:334). Growers had successfully lobbied to abolish the tax on grape exports out of the province and to get the rail freight costs reduced in time for the 1903 harvest.

75 La Prensa, April 10, 1914, p. 9, noted that the growers who suffered most were the new producers whose vines had just started producing.

76 Arata (1903:196–97).

77 The area of vines officially increased during this period, but this reflects the poor quality of official statistics rather than incentives for growers.

78 Rocchi (2006:9).

79 Los Andes, September 20, 1903, p. 4.

80 This was eight pesos per hectoliter of wine and six pesos per quintal of grapes, when market prices the previous year had been just six and three pesos, respectively (Mateu 2007:16).

81 Mateu and Stein (2006); Stein (2007).

82 La Industria, May 4, 1911, p. 5, cited in Barrio de Villanueva (2009:1).

83 Centro Vitivinícola Nacional (1910:xx).

84 Arata (1904 :111–35).

85 Liaudat (1934:18).

86 Stein (2007:102).