CHAPTER 2

![]()

Phylloxera and the Development of

Scientific Viti-Viniculture

The Midi’s high yielding viticulture is perhaps the most industrial of France’s farming systems, caused as much by the high levels of capital used as the production systems employed: a monoculture; the degree of mechanization in the vineyard and winery; the use of piece work and the creation of a salaried proletariat; and labor disputes between property owners and unions.

—Michel Augé-Laribé, 1907:11

EUROPE’S GROWERS, winemakers, and merchants had to adapt to a series of important exogenous shocks in the half century prior to the First World War. On the demand side, the decline in transport costs produced by the railways, rapid urbanization, and rising incomes led to per capita wine consumption in France reaching more than 160 liters in the 1900s, and there were significant increases in other countries, such as Italy, Portugal, and Spain. The growth in consumption was all the more impressive given that the vine disease phylloxera vastatrix destroyed large areas of Europe’s vineyards. The destruction initially was greatest in France, and rising prices encouraged wine merchants to look for new sources of supply in previously neglected regions in countries such as Spain or Algeria, while in the New World they spurred growers to increase production and become less dependent on imports from the Old World. The boom ended with the recovery in French domestic production and by the early 1900s prices collapsed, leading to protests by growers, especially in the Midi. Other countries, such as Spain, suffered less from the low prices because phylloxera was now destroying their own vines in large quantities and thereby reducing the supply of wine.

The only long-term solution to phylloxera was to uproot the dead vines and replant using American, disease-resistant roots stock, and grafting European scions. Considerable scientific research was undertaken to find suitable vines that produced both a drinkable wine and adapted successfully to the site-specific characteristics of each vineyard. The new vines produced higher yields, but they were more susceptible to other diseases, which required heavy expenditure on chemicals, so small growers had either to spend valuable cash or risk heavy crop losses. Scientific advances were just as spectacular in the wineries, with Pasteur’s work on fermentation providing an understanding of the causes of fermentation and how to keep wines in good condition. One major breakthrough of the period was the ability to produce good, cheap wines in hot climates, which allowed a rapid reallocation of production to these new regions, so that by 1914 the Midi and Algeria produced the equivalent of about half of French wine consumption. Montpellier became the world’s center for new wine-making technologies, but advances were quickly reported in other regions with hot climates thanks to individuals such as Frederic Bioletti (University of California), Arthur Perkins (Roseworthy, South Australia), and Raymond Dubois (Rutherglen, Victoria).

The new, modern wineries were capital intensive, and because of the economies of scale, production costs of a liter of wine were lower and wine quality better than in the small, family-operated wineries. They also needed large quantities of grapes if they were to be worked at full capacity, and in the Midi and Algeria, unlike in the New World, these were usually produced by winemakers integrating backward into grape production. Large, high-yielding vineyards were planted on the fertile plains and valley floors, and owners used labor-saving plows and introduced new work practices to coordinate wage labor in vineyards. Increasing wine output in these regions no longer depended on small growers using their underemployed labor to slowly extend their vineyards to create new capital assets; instead, producers looked to commercial banks for credit to plant vineyards on a major scale and create modern wineries. While small, family vineyards producing grapes remained competitive, they found it increasingly difficult to compete with the scale-dependent methods used in wine making.

This chapter looks at the growth in wine consumption in the second half of the nineteenth century and shows the impact of phylloxera on the French market, and how the stimulus of higher international prices led to a wine boom in Spain. Finally it discusses the development of scientific viticulture and wine making, and the appearance of large-scale wineries in the Midi and Algeria.

THE GROWTH IN WINE CONSUMPTION IN PRODUCER COUNTRIES

The railways transformed Europe’s economy. As early as 1858 Paris was connected to all the country’s major wine regions, and prior to phylloxera in the late 1860s French railways annually transported three million tons of wine and spirits, a figure that had tripled by 1913.1 Transport costs fell by four-fifths in the Midi, helping the region to become “une veritable monoculture de la vigne” by 1900.2 The railways pushed Europe’s wine frontier into regions long known to contemporaries as being especially suitable for the vine—the Midi (France), La Mancha (Spain), and Puglia (Italy)—allowing them to specialize for the growing urban markets.3

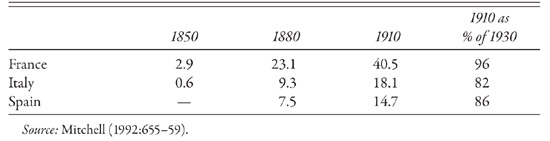

TABLE 2.1

The Growth of Railways in France, Italy, and Spain, 1850–1910 (thousands of kilometers)

The railways, by helping to integrate markets, encouraged urbanization. The percentage of the population living in French towns and cities of more than ten thousand increased from less than 10 percent in 1800 to 15 percent by 1850 and 25 percent by 1890, with Paris having more than 2.5 million inhabitants in 1896.4 By 1910, 27 percent of France’s population lived in centers of more than twenty thousand, and 59 percent worked outside the agricultural sector. In Spain and Italy, the urban population was 23 and 28 percent, respectively, and the nonagricultural labor force was 34 and 41 percent in 1910.5

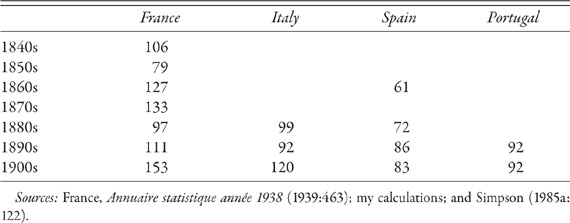

Living standards also improved significantly. Between 1850 and 1913 gross domestic product (GDP) per capita doubled in France, Italy, and Spain.6 Real wages of unskilled urban workers increased in France by about two-thirds between 1850 and 1910, and a similar improvement seems likely for Italy and Spain.7 Engel’s law suggests that consumers devote a smaller proportion of their income to food when living standards improve, but demand elasticities behave very differently according to the food item. Rising incomes in late nineteenth-century London, for example, resulted in a rapid growth in the consumption of fresh fruit, vegetables, milk, and meat but a falling demand for bread. In Europe, rising incomes led to an increase in wine consumption. In France, expenditure elasticities in 1852 for alcoholic beverages (wine, beer, and cider) among farm laborers were strongly positive, and an increase in household income of one franc produced a growth in consumption of one and a half francs. Price elasticities were equally strong at –1.33, so that “expenditure on beer and wine increased rapidly when income improved, but quickly retreated when these drinks became more expensive.”8 In France wine consumption rose from 76 liters per capita in 1850–54 to 108 liters in 1890–94, peaking at 168 liters in 1900–1904.9 The quantity consumed by producers and their families (and therefore exempt from taxes) grew from 5 to 9 million hectoliters between 1850–54 and 1900–1904, while the increase in off-farm consumption jumped from 18 to 42 million hectoliters.10 Information for the other major producer counties, such as Spain, is much less reliable, but lower levels of urbanization and living standards help explain why consumption remained lower than in France on the eve of the First World War (table 2.2).11 One major restriction in all producer countries was indirect taxes, which, because they were levied by volume rather than ad valorem, increased in relative terms during periods of low wine prices.

TABLE 2.2

Per Capita Wine Consumption in Producer Countries, 1840s–1900s (liters)

The growing market integration had an impact not just on the quantity of cheap wine produced but also on the quality. In central France it was noted:

there have been great improvements in the making of wines going on for some years. The thing is very easy to understand; formerly we had no railways, and frequently very poor roads, so the wine was only drunk on the spot, now we are beginning to send the wine upon a large scale to Paris, and some rather distant districts of France; therefore the wine must be able to bear the journey, and to travel in any temperature, and so on.12

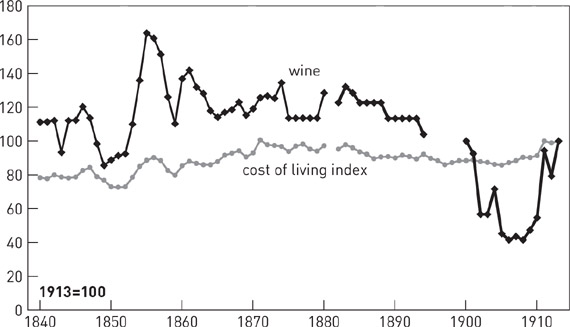

Figure 2.1. Price movements in Paris, 1840–1913. Source: Singer-Kérel (1961:452–53 and 472–73)

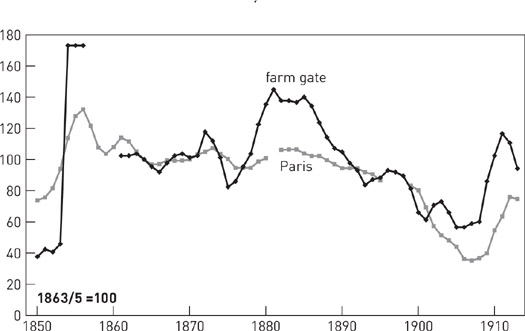

Wine quality and harvest size varied considerably, and, as noted in chapter 1, a major function of merchants was to reduce price volatility for urban consumers by blending wines from a variety of sources to compensate for these significant local annual fluctuations. As a result, prices peaked in Paris in 1855 with the appearance of powdery mildew but then remained remarkably stable until the end of the century when they fell sharply, despite the collapse in domestic wine production during the 1870s and 1880s. The movements in wine prices in Paris reflect those of the general price index, with the exception of the significant jump in the mid-1850s and fall in the 1900s (fig. 2.1). Farm-gate prices, by contrast, rose sharply, first during the powdery mildew epidemic and then during the 1870s and 1880s because of phylloxera (fig. 2.2).

PHYLLOXERA AND THE DESTRUCTION OF EUROPE’S VINES

The activities of botanists in studying and classifying local varieties, and growers in improving them, encouraged the movement of plants from one country to another.13 With the faster shipping times in the Atlantic trade and increased trade in plants, European farmers suffered from a number of new and devastating diseases, such as potato blight, pébrine, powdery mildew, phylloxera, and foot-and-mouth. Governments often responded by banning imports of plants and live animals, but once the diseases had breached national boundaries policies were needed to eradicate or control their spread.

Figure 2.2. French wine prices, 1850–1913. Sources: France. Annuaire statistique année 1938 (1939:62–63) and Singer-Kérel (1961:472–73)

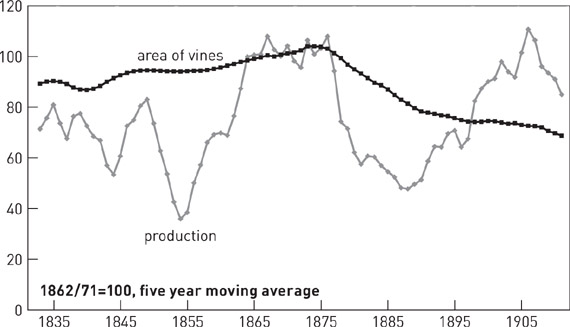

The first major new vine disease was powdery mildew, which appeared in the 1840s, although its economic impact was delayed by a decade or so. Powdery mildew caused French production to slump to just 17.6 million hectoliters between 1853 and 1856, and output between 1851 and 1861 surpassed 41.7 million hectoliters only once, a figure that the country had averaged during the decade between 1832 and 1841 (fig. 2.3).14 Wine prices doubled in the 1850s, causing French farm laborers, whose household income increased by 53 percent and food expenditure by 44 percent, to actually cut drink consumption by 25 percent,15 while nationally per capita wine consumption fell by 21 percent between 1849–51 and 1859–61. The shortages were short-lived, however, as it was found that dusting the vines with sulfur checked the spread of this fungal disease, and the recovery in French output by the late 1850s is an indicator of the widespread use of chemicals.16 Powdery mildew had now become endemic, reappearing especially in damp, warm years, increasing growers’ annual production costs.

Some European growers imported vines that were immune to powdery mildew from eastern and southern regions of the United States, and by doing so they inadvertently introduced a new disease.17 Phylloxera, which was first noticed in 1863, spread much more slowly than powdery mildew, but its long-term economic consequences were considerably greater. This tiny aphid attacked and destroyed the root system of Europe’s Vitis vinifera species, usually killing the plant within a couple of years. In time phylloxera destroyed virtually all Europe’s vines, and permanent barriers to its devastation existed only in a few areas, such as on the sandy soils of the Camargue.18 In France between 1868 and 1900, some 2.5 million hectares of vines were uprooted at an estimated cost of fifteen billion francs, while chemicals, imports of vines, replanting, and grafting added another twenty billion.19 Yet the speed of this devastation varied significantly across the continent, as suggested in map 3. In Spain, some 277,000 hectares were infected fifteen years after the disease had been first identified in 1878, but the following fifteen years saw a million hectares of vines destroyed and another 125,000 infected.20 Even so, the major wine-producing region of La Mancha only became infected in the 1930s. The spread of phylloxera was even slower in Italy, where as late as 1912 less than 10 percent of the nation’s vines had been infected.21

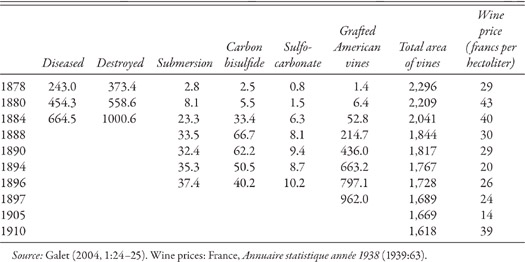

In France, wine output, which had averaged 57.4 million hectoliters in 1863–75, fell to 31.7 million in 1879–92 before recovering to 52.5 million in 1899–1913 (fig. 2.3).22 The French government offered a prize of 300,000 francs in June 1873 for an effective remedy to save the nation’s vines, and although some 696 suggestions had already been studied by October 1876, it was never awarded.23 A number of temporary solutions halted phylloxera’s march, but all were expensive as they had to be applied annually. In 1873 the flooding of vineyards was shown to be successful, but this required relatively large and compact holdings on level ground close to good supplies of cheap water. Two chemical solutions were also used: injecting the vines’ roots with liquid carbon bisulfide or spraying with sulfocarbonate. Although costly, they allowed growers to remain in production while wine prices were strong in the 1870s and 1880s and offered fine wine producers more time to adapt. Indeed, as chapter 5 shows, the phylloxera epidemic actually witnessed a major increase in fine wine production in Bordeaux. From 1884 the effects of phylloxera in France slowed, in part because of the widespread destruction that had already taken place, and in part because of the introduction of quarantine and restrictive measures in unaffected areas (table 2.3)24

Figure 2.3. Area of vines and wine production in France, 1833–1911. Source: Lachiver (1988:582–83)

As Jules-Émile Planchon, professor of botany at Montpellier, remarked, the phylloxera paradox was that the source of the disease, namely, certain indigenous American vines, was also its long-term cure.25 Planchon had argued as early as 1877 that by grafting European scions (the chosen grape variety) to American phylloxera-resistant rootstock, both vines would retain their own characteristics: the rootstock its immunity to phylloxera and the scion its traditional wine quality.26 However, French scientific opinion split into two distinct camps: the “chemists,” who wanted to save the country’s ungrafted vinifera vines, and the américainistes, who demanded the import of large quantities of American phylloxera-resistant vines.27 Prior to the mid-1880s the French government sided with the chemists, passing legislation for local authorities to control the movement of vines, destroying infected vineyards, and providing grants for chemicals. However, from the very late 1870s the use of grafted vines became increasingly popular, and the declaration of a four-year tax moratorium on vineyards replanted with American vines in 1886 marks the turning point of the French government in its switch in support to the américainistes. The slow response of the central government to replanting can be explained by the demand of local growers to keep foreign vines out of disease-free villages and regions, especially while there was still hope that chemists might suddenly discover a miracle solution that would make replanting unnecessary, just as they had done earlier with powdery mildew and potato blight. Finally, the quality of the wine produced using American vines was initially atrocious.

TABLE 2.3

Phylloxera and the Response of French Growers, 1878–97 (thousands of hectares)

The new vine diseases not only caused interruptions in wine supplies but also radically changed the organization and skills required in viticulture. In prephylloxera viticulture there were few barriers to entry for growers, as production, as noted in chapter 1, consisted essentially of two inputs: land, which was often marginal for other crops, and labor. This now changed, as the uprooting of dead vines and replanting implied heavy capital costs. Deeper plowings were required to prepare the land if the new, postphylloxera vines were to maximize their output, and this required expensive steam plows, which produced considerable savings over hand labor but were impractical on small or fragmented holdings.28 A distinction appeared in some areas between intensive, high-yielding “capitalist” viticulture, and low-yielding, less-intensive “peasant” farming.29 Vineyards were no longer self-sufficient, as growers could not replace vines by layering but had to purchase from nurseries the American rootstock that was suitable for the conditions on their own vineyard and compatible with the chosen European scions. Some combinations performed much better than others, and this information was not easily available to growers. The new vines were more delicate and susceptible to fungus diseases, requiring expenditure for sulfur for powdery mildew, or “Bordeaux mixture” (copper salts) for downy mildew. Finally, the economic life of the vines was between twenty and thirty years, considerably shorter than for traditional vines. There were some benefits, however, as the destruction caused by phylloxera forced governments to make significant contributions to scientific research, which led to a much greater understanding of viticulture, and its divulgence in a number of classics on the subject, such as Gustave Föex’s Cours complet de viticulture (1886) and Viala and Vermorel’s seven-volume Traité général de viticulture ampélographie (1910). The new vines also came into production earlier, and the development of hybrids allowed significantly larger yields, forming the basis for a new “industrial viticulture.”

Hybrids can occur naturally, but those of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were the result of the deliberate crossing of two different species in an attempt to “combine the desirable wine quality of European vinifera varieties with American vine species’ resistance” to American pests and diseases, especially the phylloxera louse.30 As direct production hybrids required less care and chemicals than vinifera vines, they became the “easiest way to obtain cheap wine in difficult times” and were quickly adopted by commodity wine producers.31 According to the historian Harry Paul, much of the bad reputation for direct producers came from the indiscriminate spread of a number of infamous varieties, which the French government would eventually ban.32

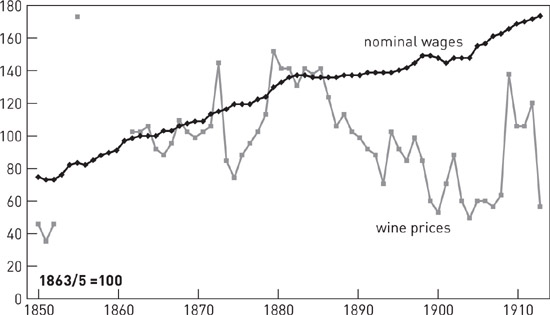

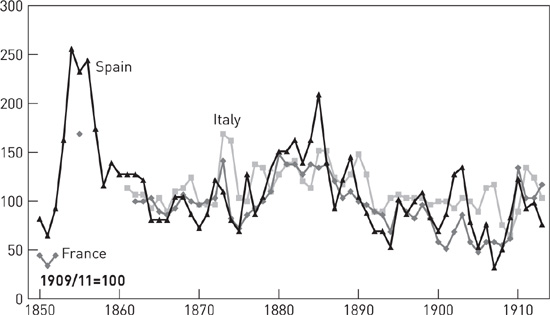

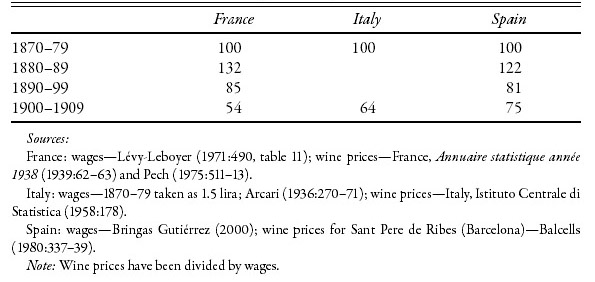

The increase in capital requirements to replant and combat vine diseases was accompanied by rising labor costs, as nominal farm wages increased by about 20 percent over the final quarter of the nineteenth century in France, and similar increases were found in parts of Italy and Spain. However, until about 1885 or 1890 growers were more than protected from rising production costs by high wine prices. This situation changed dramatically from the final decade of the century when the two indices diverged, with wages continuing to increase in many areas but wine prices falling everywhere. Growers now faced a sharp drop in profits unless they could reduce labor inputs or increase yields, as suggested by the drop in competitiveness of almost a half in France between the 1870s and 1900s, a third in Italy, and a quarter in Spain (table 2.4, fig. 2.4).

TABLE 2.4 Changes in Relative Wine Prices and Wages in Europe, 1870–1910

Figure 2.4. Movement in nominal wages and wine prices in France, 1850–1913. Sources: wages—Bayet (1997); wine prices—France. Annuaire statistique année 1938 (1939:62–63)

As the phylloxera epidemic was spread over many decades, the moment when a particular vineyard was infected was often crucial in determining how growers responded. The Midi was one of the first major regions hit, allowing replanting to take place during a period of high wine prices. Others were not so lucky, and failed to replant, so that the area of vines in France declined by almost a million hectares, equivalent to 40 percent, from its peak in 1874 to 1,535,000 hectares in 1914, although higher yields implied that output did not change significantly (fig. 2.3).33

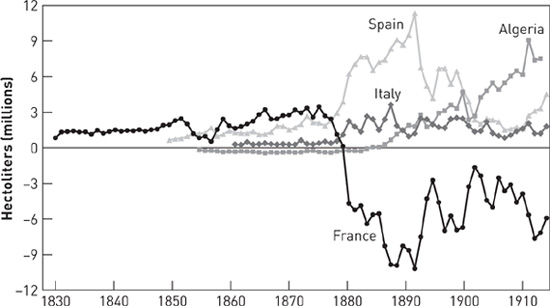

Figure 2.5. Net exports of wine from the major producer countries, 1831–1913. Source: national trade statistics

Figure 2.6. International wine prices, 1850–1913. Sources: France. Annuaire statistique année 1938 (1939:62–63); Italy. Istituto Centrale di Statistica (1958:178); and Balcells (1980:337–39)

PHYLLOXERA AND THE INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE IN SPAIN AND ITALY

The rapid and early destruction of vines by phylloxera in France led to major changes in the international wine market, as the country switched from being a net exporter to an importer in 1879, requiring imports equivalent to 22 percent of total domestic wine supply between 1886 and 1895 (fig. 2.5). The presence of common exogenous shocks—shortages caused by new vine diseases and greater market integration—resulted in wine prices in France, Italy, and Spain moving in similar directions (fig. 2.6). Spanish producers benefited most from France’s domestic shortages because their vineyards were closer to the major wine centers of Bordeaux and Cette than were those of Italy, and their wines better matched the French requirements for blending.

Powdery mildew ruined Europe’s harvests in the 1850s, and overnight Spain became a major force in the international market for cheap table wines, as the incidence of the disease was less there. Wine prices in the Mediterranean provinces such as Alicante tripled between 1851 and 1855, as low transport costs allowed producers to export to France. By contrast, while there were plenty of potential wine-producing regions in Spain’s interior, high transport costs made production unprofitable.34 As one contemporary wrote:

Large as is the extent of country in Aragon and Navarre cultivated with vineyards, it is small in comparison with what it might be if the demand for the wines of those provinces should continue, and what it certainly will be when the railroads now in course of construction are completed to the French frontier, as well as to Bilbao and Barcelona, which lines will be of equal benefit to the vineyards of Old and New Castile, many of which, like those of Aragon, have been as little known to the rest of Spain as they are to the rest of Europe.35

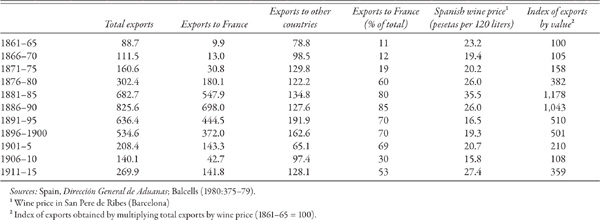

When phylloxera devastated French harvests and international prices rose again from the 1870s, the railways allowed many more Spanish growers to respond than had been possible a couple of decades earlier. The export boom drove up wine prices (table 2.5), leading to higher wages and land prices and producing widespread regional prosperity.36 The French market required wines of good color and an alcoholic content of up to 15 percent to mix with their low-strength wines of the South and Southwest. In fact, exporting strong wines made economic sense as French import duties and transport costs were the same for all wines up to this strength, and fortifying wines with alcohol before shipping helped overcome the persistent problem of their poor keeping quality. The high prices, however, significantly reduced the wine available for distilling, and Spanish producers and exporters turned instead to foreign “industrial” alcohol produced from potato spirits or sugar beets. Imports jumped from less than 150,000 hectoliters a year during much of the 1870s to over a million hectoliters in 1886, when it was noted in the important wine province of Tarragona (Catalonia) that “the commerce of true wines has been greatly diminished for some time in this area, as a considerable quantity of those that are exported have only a small base of wine, the rest is composed of water, foreign alcohol, colouring materials and tartaric, citric and sulphuric acids, the last of which is harmful to the health.”37

TABLE 2.5

Exports of Spanish Table Wines, 1861–1915 (millions of liters)

Industrial spirits were also used for the home market, and one contemporary estimate suggested that if Spain exported 8 million hectoliters of wine, the 12.5 million hectoliters left for domestic consumption was augmented by a further 4 million of wines fabricated using foreign alcohol.38 Complaints concerning the absence of “good” wines and the presence of adulterated ones became as common in Spain as elsewhere, a subject we shall return to in the next chapter.

Spanish growers responded to increased demand in a variety of ways, reflecting in particular local resource endowments. Perhaps the most dramatic change was La Mancha, a huge central plain that was ideally suited to the vine once the region was connected by rail to the country’s major urban markets and ports. Yields were low, just 10 hectoliters in Ciudad Real in the 1880s compared with 24 hectoliters in Barcelona, but production costs were 25 percent less per hectoliter.39 Costs were low because plows could be used between the widely spaced vines, and the hot, dry conditions permitted the goblet pruning system, removing the necessity of using stakes or trellises. The region was also phylloxera free until the 1930s and suffered less from other diseases because of climatic con-ditions, allowing growers to continue using traditional vines and planting systems.

Increasing output by using more land and labor in response to high prices and export demand was the most common, but not the only, response of Spanish producers. From the late eighteenth century the small but highly dynamic sherry export sector witnessed significant investment in cellars and wine-making equipment and a division of labor between grape production, maturing wines, and exporting (chapter 8). The rapid growth in export demand for cheap table wines now led to the creation of industrial bodegas, or large wineries, which were established, often by foreigners, around the Spain’s Mediterranean ports.40 Because there were few economies of scale to be achieved in wine making until the 1890s, these bodegas acted primarily as depositaries for collecting wines for blending, creating special wine types such as port, or adding industrial alcohol or artificial coloring. The poor quality of many local wines encouraged some of these houses to integrate backward into wine making to ensure a better commodity or encourage winegrowers to make improvements. Producers along the Mediterranean littoral in Catalonia and Valencia copied production systems found in southern France, using sulfur to clean utensils and alcohol to strengthen wines, racking the wine from the lees, and maturing it in wooden casks. Iron crushers for grapes and presses for the pomace also became more common.41 However, Spain’s industrial wineries in the 1870s and 1880s enjoyed few economies of scale, capital was tied up in stock rather than equipment, and wine in the large fermenting vats ran the risk of overheating.42

By contrast, the attempts to produce premium table wines were less successful. One pioneer was the Marqués de Riscal in the Rioja region, who in the 1860s hired an enologist (Jean Cadiche Pineau) and imported fine vine varieties (cabernet sauvignon, malbec, and sémillon rouge), as well as copying the bordelaise wine-making methods. Riscal was never going to compete with Bordeaux’s grand crus, but a major market existed in the late nineteenth century for blending wines to create good, ordinary claret that could be shipped from Bordeaux to Britain at £4 a hogshead (see chapter 4). When this market disappeared at the turn of the century, Riscal reinvented itself by selling much smaller quantities of bottled wine under its own brand name. Yet prices were low and remained stable from one harvest to the next, a clear indication that consumers were insensitive to annual changes in quality and suggesting that the problem of producing premium wines was as much one of demand as one of inadequate technology or lack of wine-making skills.43

The rapid response of thousands of small growers to high wine prices illustrates the market-oriented nature of Spanish viticulture rather than a simple response to growing population pressure, as suggested for an earlier period by Le Roy Ladurie and others. It did not to last, and the boom was brought to an end by the increase in French tariffs in 1892 in response to rising domestic production in that country, resulting in a 75 percent decline of Spanish exports between 1886–90 and 1901–5 (table 2.5).44 A second shock was phylloxera, which destroyed a third of Spain’s vines between the late 1880s and First World War. Because of the depressed international market, even the phylloxera-induced shortages failed to increase domestic prices in the early 1900s. The growers’ response to the collapse in demand varied. In Barcelona, the divergent movement of wine prices and wages created considerable social tensions. Sharecropping, which had been considered an integral part of the success of local viticulture, was now regarded as an instrument of exploitation by landowners, and there were widespread demands for land reform.45 By contrast, the decline in French demand for wines strengthened the industrial bodegas in Spain. The laws of 1887 and 1892 severely restricted imports of foreign alcohol, which encouraged local producers to develop a range of domestic brands of alcohol-based drinks, such as liquors or brandy, that enjoyed economies of scale in production and marketing, thereby benefiting the industrial wineries.46

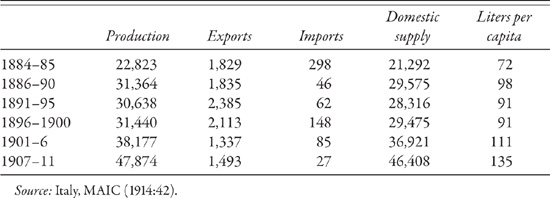

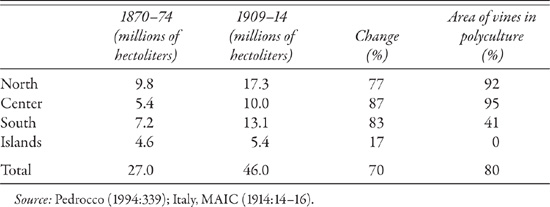

The experience of Italy in the half century prior to 1914 was similar in many ways to that of Spain, although a growing population and rising wages increased domestic demand to a greater extent, and exports peaked in 1891–95 at just 8 percent of output, significantly less than Spain in absolute and relative terms (tables 2.5, 2.6). France was the major export market until it was closed to Italian wines in 1888 and then replaced by Austria-Hungary until 1904. Figure 2.6 shows wine prices rising until the late 1880s, but the area of vines increased by 42 percent and yields by 45 percent between 1880–84 and 1909–13.47 The late unification of the country resulted in viticulture being widely practiced in each of the old states: 38 percent of wine was produced in the North in 1909–13, 22 percent in the center, 29 percent in the South, and 12 percent in the islands, although two-thirds came from six regions–Sicily, Puglia, Tuscany, Campina, Emilia, and Piedmont.48 Phylloxera first appeared in Italy in 1879, but as late as 1914 perhaps only 7–10 percent of the vines were dead or dying, the great majority of these being in Sicily and the South, areas where the vine was predominantly cultivated on its own, and not intercropped.49

Sicily had long been famous for its strong, sweet wines, most notably marsala, which traced its history back to the arrival of the British merchant John Wood-house in 1770. The rapid growth in wine output in the late nineteenth century, from 4.2 million hectoliters in 1870–74 to 7.7 million in 1879–83, however, was linked to cheap table wines. Phylloxera then devastated the island, and as wine prices fell because of the recovery of French production, vineyards were returned to extensive cereals and laborers emigrated in huge numbers to, among other places, Mendoza, Argentina, where they helped establish a new industry (see chapter 11).

TABLE 2.6

Production, Trade, and Consumption of Italian Wine, 1884–1911 (thousands of hectoliters)

In the southern region of Puglia, the area of vines increased from 134,000 hectares in 1879–83 to 282,000 in 1913, and production was 5.2 million hectoliters, or 11 percent of the country’s total. Like the Midi and La Mancha, Puglia benefited from low-cost land, which had previously been used for extensive cereals or grazing. The large estates were worked by sharecroppers, and if yields were low because of the dry climate, so too were the risks of vine disease. This low-cost but isolated region was linked by the railways to Italy’s major urban markets after unification.

Yields were also low in central and northern Italy, but this was because the vine was just one of several crops produced on the same plot (table 2.7). This allowed farmers to vary labor inputs in relation to commodity prices but made it very difficult for contemporaries to estimate output or production costs.50 In Tuscany, the large estates (fattoria) were divided up into small farms (podere) and let to sharecroppers, with the landowner marketing relatively large quantities of wine. The nobility and gentlemen farmers of Florence’s Accademia dei Georgofili tried to improve the local wines, but much chianti remained poorly made from an excessively large number of grape varieties, fermented in musty wooden barrels and sold in the famous straw-covered fiasco.51 By the late nineteenth century the loudest calls for change in viticulture and wine making came from northern Italy, and especially from Ottavio Ottavi. Experts called for the creation of regular vineyards, rather than having vines hanging from trees; the specialization in a few tested and tried grape varieties; and the creation of large-scale, scientific wineries.52 Changes eventually came, but well after 1914 because, as elsewhere in Europe, the vast majority of consumers were unwilling to pay a premium for better-quality wine.

TABLE 2.7

Wine Production by Region in Italy, 1870–74 and 1909–14

WINE MAKING, ECONOMIES OF SCALE, AND THE SPREAD OF

VITICULTURE TO HOT CLIMATES

The appearance of new vine diseases such as powdery mildew, phylloxera, and downy mildew was a major determining factor in growers’ pursuit of technological change in viticulture. Indeed, it is a classic example of the “Red Queen” effect, namely, farmers being required to innovate simply to keep yields stable.53 Other changes, such as the introduction of wire trellises or plows, had important labor-saving characteristics. While these changes increased capital requirements, however, they did not reduce the competitive advantage of the small, family-operated vineyard. This was not the case with technological change associated with some of the new wineries from the 1890s.

Pasteur’s Etudes sur le vin was first published in 1866 and, according to Amerine and Singleton, “represents the application of the scientific revolution to the wine industry.”54 Pasteur identified the existence and activities of bacteria and yeast in wines and argued that the spoilage of wine was due to aerobic microorganisms producing acetic acid, which could be avoided by careful wine-making techniques. Pasteur showed that the grape’s natural yeasts produced very different results, and he advocated instead the use of selected yeasts that had been scientifically produced in laboratories to achieve a better fermentation. These allowed a quicker and more predictable fermentation, as dangerous microorganisms could be “swamped” by the addition of large number of wine-yeast cells.55 The problem was especially acute in hot climates where the high temperatures in the vat ended fermentation prematurely and the unfermented sugar left in the wine allowed bacteria to appear that quickly ruined the wine, a development made more likely by the wine’s lack of acidity. Excess heat was produced by three major factors: the initial temperature of the grapes, the heat generated by the rapid speed of the fermentation (which in turn was caused by the high quantity of sugar in the grapes), and the small amounts of heat lost through radiation and conduction in the vat. In theory, grapes could be collected in the early morning while they were still cool, and the wine fermented in small vats of less than 35 hectoliters, which reduced the heat loss because of the relatively large surface area. Yet neither was feasible even on small vineyards. For producers, especially the larger ones, the secret was to slow the rate of fermentation, which would limit the heat produced. Two very different methods were initially used: in parts of southern France, grapes with a very high level of acidity and low sugar content were grown; whereas in Algeria, where conditions were hotter, the fermenting must itself was cooled.

Viticulture excellence in regions of hot climates was limited to fortified dessert wines, such as port, sherry, and madeira, which had their fermentation interrupted prematurely by the addition of grape alcohol. However, there was little demand for dessert wines in Europe’s wine-producing countries. Instead, the expansion of cultivation in the Midi after the railways was linked to the aramon grape variety, which was planted on a massive scale. This provided large quantities of thin, watery wines with a good acidity, but with an alcoholic content of only about 8 percent. The lack of sugar in aramon grapes considerably reduced the difficulties of wine making by limiting the heat generated during fermentation but produced a very unattractive wine for consumers. They were, however, ideal for blending with wines that were strong in alcohol content and color but lacked acidity. Initially these wines came from countries such as Spain, where the problems of high temperatures during fermentation were solved by their strengthening with alcohol before shipping. When the 1892 tariff effectively closed this market, the Midi merchants looked to Algeria, where growers chose the carignac and alicante bouschet grape varieties because their color, body, and alcohol complemented perfectly the acidity of the aramon. In Algeria the vintage was started early, when the grapes were capable of producing wine with 8 percent alcohol, but by the time the harvest had finished the figure had reached 12 or 14 percent. The higher acidity of the early wine helped complement the lower levels found toward the end of the season.56 Early picking, however, carried an important economic loss, and Algerian wine in the 1880s and early 1890s was notorious for its poor quality.57 However, by 1914 new wine-making technologies allowed a stable, dry wine to be produced in large quantities and at a cheaper cost per hectoliter than could be achieved in small wineries.

The limited number of grape varieties found on the large estates in the Midi and Algeria produced huge harvests that had to be crushed in a short time period. New wineries were now designed to handle large quantities of grapes quickly, allowing animal-drawn carts to deliver the grapes directly to the hoppers prior to crushing. It was recommended that fermentation take place in well-ventilated buildings, “open freely to all winds, and constantly swept by draughts,” to allow the heat to escape, but the wine was then best matured in the cool of cellars, which in the Midi were often separate buildings.58 Wine was moved from the vat to the barrels by hand and later by electric pumps. One very large winery in Aude had twenty fermenting vats, each holding about 350 hectoliters and with a daily capacity of 1,400 hectoliters, which was fed from 215 hectares of vines and producing 30,000 hectoliters of wine.59 In Algeria after 1895 the wooden vats were replaced by brick ones, and around the turn of the century by reinforced cement amphoras.60 To crush the grapes aero-crushing turbines were deployed, which, instead of using rollers, applied a centrifugal force projecting the grapes against the vertical wall of the fixed cylinder of the turbine. When driven by steam, a turbine was able to crush from 180 to 200 tons a day, equivalent to about ten times the output of a medium-sized proprietor.61

The prolonged maceration at excessive temperatures gave Algerian wines a disagreeable earthy taste. This was the result of winemakers trying to ferment all the sugar out of the must, and devatting the wine fifteen or eighteen days after fermentation started. The problem was avoided if the must was cooled and a regular, short fermentation of five or six days carried out.62 In 1887 Paul Brame successfully devised a system whereby the temperature of the must was reduced by pumping it through tubes that were immersed in water, although it was only after Algeria’s “deplorable vinification” of 1893 that the system became widely adapted.63 By the turn of the century it was noted that “there is probably not a single large cellar in Algeria, Oran, or Constantine which does not possess one or more of these machines, and by their use the production of a sound, completely fermented wine has been possible in all cases.”64 This interest soon faded, however, given the relatively high cost of cooling large amounts of water in hot climates to produce cheap commodity wines. Other problems included the loss of color and extract in the wine, qualities the Midi merchants required.

The use of cultured yeasts became common in the large wineries after George Jacquemin established a commercial supply in 1891,65 and they permitted a second method for controlling the temperature during fermentation, namely, sulfiting, or the pumping of sulfur anhydride through the must, which also became widely used in the 1890s. Sulfur dioxide was popular in wine making as it killed most undesirable organisms found in musts and wines. Wine yeasts can tolerate moderate concentrations, although it had long been known that, used in sufficiently high doses, it stopped fermentation completely.66 In the South of France sulfur was often burned in casks before introducing the must, but by the late nineteenth century more efficient sulfurizer pumps were used so that the gas arrested the reproduction of the wine yeast and rendered it inactive for a certain time, but without killing it. By delaying fermentation, grapes could be transported to wineries situated in cooler areas, or begun at night. At the turn of the century a winery at Villeroy (Cette) produced 2,500 hectoliters of white wine annually this way,67 but sulfiting was initially less successful with red wines because they were fermented with their skins, encouraging the leading winemakers to increase the output of white wine.68 Some specialists suggested separating the process of maceration (extraction of tannins and coloring from the grape skins, seeds, and stem fragments) from that of fermentation (conversion of sugar into ethyl alcohol and carbon dioxide).69 By the 1920s sulfiting—along with night fermentation, medium-sized fermenting vats (40–100 hectoliters), and cellars that were open to cool night air—was considered adequate in “not excessively hot” regions.70 The process was usually much cheaper than cooling, and the result was that most wines were made this way in hot climates after the First World War, sometimes with excessive amounts of sulfur anhydride, leading to a disagreeable taste and aroma in the wine.

Pasteurization involved the heating of diseased wines to destroy all microorganisms and was carried out in wine merchants’ cellars rather than in wineries.71 In part this was because diseases often became apparent only after the wine had been sold, but also because of expense, with wine producers using sulfuric acid and other sulfides as cheaper substitutes.72

The new wineries that appeared in the Midi and Algeria from the 1890s were efficient in a number of areas. The capital cost for constructing a small wine cellar was approximately double that of the largest cellars,73 and according to Roos, the larger wineries produced a hectoliter of wine for about half the cost of the smaller ones.74 In addition, 5–15 percent more wine was extracted from the grapes.75 Better-quality wine was produced because skilled technicians were hired and scientific practices were used in wine making. These were indivisible inputs, implying that the total cost varied little whether a 100 or 10,000 hectoliters were produced. The new technology therefore resulted in both lower production costs and better-quality wines that could be sold for higher prices than those made in the old, family cellars. At times of scarcity and high prices, small growers had little trouble selling their wines straight from the fermenting vats, but when market conditions changed after 1900, they found themselves excluded from the market, as the wholesalers bought better-quality wines in bulk from the large producers (chapter 3). The major weakness of the large industrial wineries was that they often carried debt, which made them especially vulnerable in the early 1900s.

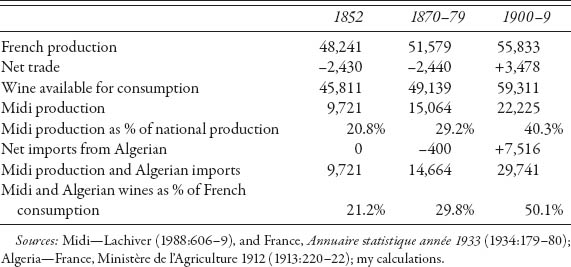

The new wineries offered greatest returns to producers in hot climates because of the nature of the technology and the need to have large supplies of grapes.76 They contributed to a radical shift in the locus of production of cheap bulk wines from Europe’s center to its southern periphery. In particular, the Midi and Algeria saw their output increase from the equivalent of less than 15 percent of domestic consumption in the 1820s to 50 percent by 1910 (table 2.8). The new wine-making technology was also a crucial factor in the expansion of viticulture in the New World. In theory, at least, the technology available in 1914 therefore made it possible to make a high-quality dry wine for popular consumption in most viticulture regions, something that was not true twenty years earlier. In reality, wine producers chose their technology and production methods to maximize profits rather than quality, and the preference of most consumers was for cheap alcoholic wines rather than better-quality but more expensive ones.

TABLE 2.8

Growth in Midi and Algerian Production and French Wine Consumption (thousands of hectoliters)

LA VITICULTURE INDUSTRIELLE AND VERTICAL INTEGRATION:

WINE PRODUCTION IN THE MIDI

Historians today often argue that small family farmers were more efficient than plantations in the production of commodities such as coffee, sugar, or cotton in the late nineteenth century because family workers had much greater incentives than wage laborers to properly care for the plants and to work quickly.77 The same was usually true with grape production, and to this day small family vineyards remain highly competitive next to the large estates. This in part explains that, despite the appearance of scientific wine production, the integration of grape production and wine making remained the norm in Europe, and as late as 1934 some 86.5 percent of all French wine production outside the Midi was found in wineries of less than 400 hectoliters, an amount that could often be supplied from the family vineyard. By contrast, in the Midi about half of all wine was produced in small wineries, and 8 percent, or almost 2.5 million hectoliters, in those of more than 5,000 hectoliters.78 The slow spread of large wineries outside areas of hot climates was caused primarily by the high transaction costs associated with obtaining grape supplies. The new wineries required grapes from the equivalent of perhaps twenty or thirty times what a family vine-grower could produce, so the owners had to take the strategic decision as to whether to integrate backward into grape production themselves or purchase their needs from independent suppliers. In the New World, as shown later, the large wine producers sourced a large part of their needs from independent growers, but in Europe the number of grape varie-ties grown was much greater and quality was highly varied because of climatic conditions, making it difficult for growers and wine-makers to create an efficient payment system for grapes. Fine wine producers in Bordeaux resolved the problem through direct cultivation and paying high wages, but this was not profitable for most cheap commodity wine producers, outside a few new areas of production.

By contrast, winemakers in the Midi and Algeria created large, integrated wineries on “green field” sites, and the problems associated with controlling work effort in the vineyards were reduced by a radical restructuring of production. There was significant inequality in landownership in the Midi, which probably increased during the second half of the nineteenth century. Rather than a source of conflict, however, the extremes in property ownership encouraged cooperation among growers. Even before phylloxera, the high demand for skilled labor on the large estates and the excess supply of labor on family farms helped to compensate for each other. This was particularly true of tasks such as pruning, with large owners being willing to let skilled vinedressers work a six-hour day, finishing at two or three o’clock each afternoon so that they could work their own vines.79 The prospects of repeat work the following year provided incentives for the vinedressers to work diligently.

The mutual links between large and small properties were reinforced by phylloxera. The early appearance of the aphid in the region saw growers demanding state involvement to find a scientific solution to the disease. Local institutions, such as the University in Montpellier and the École nationale d’agriculture (La Gaillarde), played a major role in the introduction of American vines.80 The Midi’s large landowners were closely involved with these institutions, and through formal and informal labor contracts they provided a steady flow of information to the smaller growers. They lent equipment, money, the use of their wineries, information, and often the vines themselves in exchange for labor service.81

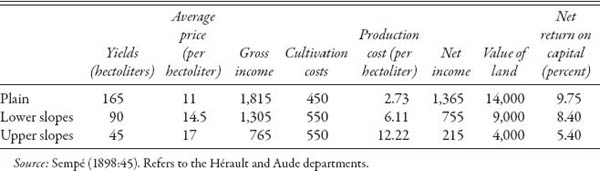

Augé-Laribé coined the term “industrial viticulture” for the large wine estates, first in the Midi and then later in Algeria. These were established on the fertile plains rather than the hills, and growers used large quantities of pesticides, fungicides, artificial fertilizers, and even irrigation to improve yields. When the black rot appeared in 1887, it “was so frightening that vignerons turned from vines grafted on Vitis vinifera to direct-producing hybrid vines, which scientists had singled out because of their resistance to diseases.”82 But disease was not the only factor. Rising production costs, the low opportunity cost on the old hillside vineyards, and the difficulties in obtaining sufficiently high prices to offset the lower yields associated with the better vines also drove many traditional growers to plant high-yielding hybrids on flat, fertile plains instead.83 According to one contemporary, consumers demanded first and foremost wine, regardless of its quality, which encouraged growers to maximize yields: “it was a secondary detail whether the wine was good; during those years all wines were expensive, irrespective of their bouquet, color, or alcoholic strength. The trade paid more to the producers of quantity than those of quality.”84 Yields reached 59 hectoliters per hectare in the Midi in the period 1911–14 but 105 hectoliters on the huge estate of the Compagnie des Salins du Midi (CSM) when national average was only 33.5 hectoliters.85 The industrial vineyards became considerably more profitable than those of the small hill farmers (table 2.9).

TABLE 2.9

Production Costs in the Midi in the Late Nineteenth Century (in francs)

Growers increased yields by choosing new grape varieties such as the aramon, by carrying out only a light pruning, and by using significant quantities of artificial fertilizers. Being the first to suffer from phylloxera had the advantage that replanting took place at a time of wine shortages and rising prices, which attracted large quantities of outside capital to be invested in the region.86 The need to replant after phylloxera allowed landowners to redesign vineyards and grow vines on trellises in long, straight lines so that plows and horse-drawn sprays could move between them with ease, thereby cutting labor inputs and reducing monitoring costs associated with wage labor.87 Augé-Laribé gives the example of a grower in Coursan (Aude), where plowing costs on the main vineyard of 50 hectares were four days, compared with the six days that were required on some of his other small plots.88 Work skills were reduced by replacing pruning knives with secateurs from the late nineteenth century.89 As Jules Guyot, perhaps the leading writer on viticulture at this time, noted, “skilful men certainly do more and better work with the knife, but when the proprietor is obliged to employ any ordinary vigneron or labourer to prune his vineyard, the secateur is preferable. It requires long practice to use the knife well and quickly.”90 As supervisors could easily walk between the rows to check an individual’s work, they achieved greater control over the speed and quality of operations such as pruning, spraying, cultivation, and harvesting. Guyot writes: “A simple glance along the line of vines, permits the owner to spot the skill or the negligence of his vinedressers, just as the foreman can control with the same ease the quantity and quality of work of each of his workers.”91 The increasing labor scarcity in southern France attracted migrant labor from Spain (for vineyards in Pyrénées-Orientales, Aude, and Hérault) and Italy (for those in Var), and these worked in gangs (colles), which consisted of ten to fifteen skilled vinedressers who contracted for employment and benefited estate owners in that both the organization and monitoring were effectively subcontracted.92

According to one study at the turn of the twentieth century, economies of scale began to be important on vineyards of over 30 hectares and reached their maximum at between 60 and 80 hectares, with diseconomies appearing on estates of over 90 or 100 hectares.93 This went a long way to resolve the problems associated with supplying the large new wineries with sufficient grapes. However, the estates had to be compact, as the potential economies of scale were quickly lost if the vineyard was fragmented into a number of small plots. This implied that there were often problems in establishing large vineyards in traditional areas of production as the land was already heavily fragmented into hundreds of plots.

In Algeria the area of vines increased from 17,614 hectares in 1878 to 174,490 hectares twenty-five years later.94 Production was frequently large scale, with capital being provided by French banks, skilled labor by temporary Spanish migrants, and cheap, unskilled labor by local workers. In the first decade of the twentieth century, there were fifty-three wineries with a capacity of 10,000 hectoliters or more, and eighty-four vineyards with over 100 hectares.95

The appearance of powdery mildew in the 1850s acted as a major incentive for merchants to develop new sources of supply, integrating producers in the Midi with consumers in northern France and developing links between Spain’s coastal regions and southern France. However, trade was still limited because of the high transport costs. By the time phylloxera started to devastate French vines in the late 1870s, European growers were much better placed to deal with the resulting shortfall. The increase in prices was more moderate than it had been with powdery mildew, as French merchants imported around a third of Spanish production. Phylloxera changed the nature of traditional viticulture, as growers needed both physical and human capital in what had been previously an occupation that required virtually no off-farm inputs, and skills were handed from father to son. Growing market specialization and new technologies also produced significant changes in wine making. Large, modern wineries not only lowered production costs but also produced better-quality wines. The problems of oversupply in the early 1900s were caused in part by fraud, but also by rising yields, resulting in part from the spread of hybrids and the better keeping quality of wine.

These changes also contributed to a major geographical reorganization of the industry within Europe and the Mediterranean basin. The reduction in transport costs allowed low-cost producers in areas such as the Midi, La Mancha, and Algeria to compete in both national and international markets. This specialization was based partly on low regional wages, but also on the capital intensiveness and greater skills found in the new vineyards and wineries. A distinction can also been made between Algeria, with its large, modern wineries and cooling equipment, and the Midi, which resorted, in part at least, to planting a highly acidic grape variety. By 1900 the Midi’s most serious competition was no longer from wines produced from grapes in other French regions, but rather from the sale of adulterated wines.

1 Price (1983:245, 296).

2 Lachiver (1988:410). For example, after 1858 the cost of transporting a muid of wine from Montpellier to Lyon fell from 50 to 7 francs (Degrully 1910:324). The cost from Montilla (Córdoba) to Jerez fell by 75 percent. See chapter 8.

3 Water transport remained the most economical, and as late as 1903–5 some 40 percent of the wine that entered Paris’s bonded warehouses came by boat, compared to 53 percent brought by rail and 7 percent by road (Richard 1934:20). My calculations.

4 In France the figure was 8.8 percent in 1800; in Italy, 14.6 percent; and in Spain, 11.1 percent. By 1890 in France the figure was 25.9 percent; in Italy, 21.2 percent; and in Spain, 26.8 percent (De Vries 1984:45–46). For Paris, Pinchemel (1987:146–47).

5 Simpson (1995, table 8.5).

6 Maddison (1995:104–8). The increase was 109 percent in Italy, 107 percent in France, and 97 percent in Spain.

7 Williamson (1995:164–66). For Italy, wages increased by two-thirds between 1880 and 1910. Rosés and Sánchez-Alonso (2004:407) give an increase of 53 percent for nonskilled urban wages between 1854 and 1914 in Spain.

8 Postel-Vinay and Robin (1992:503–4).

9 Nourrisson (1990:321).

10 Calculated from Degrully (1910:320–21).

11 For Spain, see Archivo Ministerio de Agricultura, leg. 68, exp. 1, cited in Pan-Montojo (1994: 41).

12 United Kingdom. Parliamentary Papers (1878/79), F. R. Duval, no. 5545, p. 273.

13 One of the first volumes of any importance was Simon de Roxas Clemente y Rubio, Ensayo sobre las variedades de la vid común que vegetan en Andalucía (1807). For a general background of the connection between the “Industrial Enlightenment,” technological change, and economic growth, see Mokyr (2004).

14 Calculated from Lachiver (1988:582). No production figures exist for 1842–49.

15 Meat increased by 27 percent and bread by 7 percent (Postel-Vinay and Robin 1992:506–7).

16 If this took place too close to the harvest it would affect the taste of the vine, and in warm weather excessive spraying made workers ill. The Médoc châteaux were reluctant to use sulfur on a large scale before 1857–58 (Loubère 1978:79).

17 As early as 1872 Jules-Émile Planchon of Montpellier University suggested that the large imports of plants, rather than cuttings, had provided the medium for introducing the phylloxera aphid into Europe (Campbell 2004:108). By contrast, Ordish (1972:5) argues that the faster shipping times allowed the aphid to survive on plants imported by scientists and growers. Total imports of all plants to France jumped from 460 tons in 1865 to 2,000 tons by the 1890s (Robinson 2006:522).

18 For the very few isolated areas in Europe that survived phylloxera, see Campbell (2004:275–77). Prices for the better land in the region of Aiguesmortes rose after the outbreak of phylloxera from 100 francs a hectare to 3,000 (Ordish 1972:94–96).

19 Galet (1988), cited in Paul (1996:16). Trebilcock (1981:157) suggests a “final bill” in excess of £400 million (10 billion francs), equivalent to 37 percent of the average annual GDP for 1885–94.

20 García de los Salmones (1893, 1:14); Spain, Ministerio de Fomento (1909:192–93). In 1893 some 14,871 hectares had been replanted, compared with 323,858 hectares in 1909.

21 Loubère (1978:175).

22 Calculated from Lachiver (1988:582–83).

23 Ordish (1972:68, 70).

24 Pacific Rural Press (1901:372)

25 Cited in Guy (2003:89–90).

26 Campbell (2004:160).

27 For details, see Pouget (1990); Paul (1996); and Campbell (2004).

28 Deep plowing facilitated the rooting and growth of young vines and economized hand labor. In the words of one contemporary, “spend more money and labor in getting your land into good order and you will have to spend less in trying to keep it in good order” (Bioletti 1908:54).

29 Carmona and Simpson (1999:307) describe this in Catalonia.

30 Robinson (2006:351).

31 Paul (1996:75). Because hybrids were not officially encouraged, much of the research was undertaken on private initiative, and growers received technical information from nurserymen, whose “chief interest was to sell” (p. 101).

32 Ibid., 103, 105. Restrictions began in 1919, and all new plantations were banned in 1975.

33 The area reached 1.66 million hectares in the mid-1930s before slowly declining once more.

34 Spain suffered less from powdery mildew than either France or Portugal. Wine prices in Alicante jumped from 10–15 dollars per pipe (100 gallons) in 1851 to 35–50 dollars in 1855, while exports increased from just 200 or 300 pipes to 23,767 from the port of Alicante (United Kingdom. Parliamentary Papers 1859:12–13). For a discussion on supply elasticities during powdery mildew and phylloxera shortages, see especially Nye (1994).

35 United Kingdom. Parliamentary Papers (1859:31). Small quantities of Navarra wine did reach France at this time (Lana 2002:165–96).

36 In landlocked Navarra, wine prices averaged only 60 percent of those in Barcelona between 1841 and 1865, but the railways helped to narrow the gap to 84 percent during the period between 1875 and 1894. It then opens to 77 percent between 1894 and 1900 as Navarra had greater difficulties in adapting to the loss of the French market (Balcells 1980; Lana 1999:211–14).

37 Consejo Provincial de Agricultura, Industria y Comercio, in Crisis Agrícola y Pecuaria (1887–89, 3:132:26).

38 Antúnez (1887:16); Simpson (1985a:346–52). There are no reliable figures for the area of vines or wine output until the late 1880s, just when the export boom was ending. One estimate suggests that the area under vines grew by a third between 1858 and 1888, with the greatest growth occurring during the last decade (Pan-Montojo 1994:384–93).

39 Simpson (1995:211).

40 Pan-Montojo (2003). Ridley’s, March 1882, pp. 73–74, regretted that there were not more, as it claimed that winegrowers attempted to maximize yields by gathering the harvest too early to avoid grapes falling to the ground.

41 Navarro Soler (1875:184–201), quoted in Pan-Montojo (1994:90–91). The quality of these cheap wines improved, so that, according to one report, “in former times these Spanish red wines were abominable, because they were put in skins instead of being put in wooden casks, and the consequence was that they were almost undrinkable in France, whereas now they are much better.” United Kingdom. Parliamentary Papers (1878/79), Lalande and Guestier, no. 5191, p. 250.

42 This was especially true for sherry in Jerez (Maldonado Rosso 1999:228–57; Montañés 2000; and Pan-Montojo 2003:316).

43 For the Marqués del Riscal, see especially González Inchaurraga (2006). In the Rioja region, the Riscal bodega was founded in 1862 and Murrieta in 1872, while Vega Sicilia in Valladolid dates from 1864 (Pan-Montojo 1994:82–97).

44 Prosperity for domestic growers remained linked to the French market. In 1923 it was noted that “if France takes 3 million hectolitres, wine is sold at 40 pesetas a hectolitre in Spain; if she takes no more than a million, it is sold at 15” (El Progreso Agrícola y Pecuario 1289, April 7, 1923, p. 220).

45 Carmona and Simpson (1999).

46 Pan-Montojo (2003:323–27).

47 Calculated in Simpson (2000, table 3).

48 MAIC (1914:24–27). By contrast, 45 percent of the population lived in the North, 17 percent in the center, 25 percent in the South, and 13 percent in the islands.

49 Loubère (1978:178). According to this author, when grape production was accompanied by other farming activities on the same plot of land, the “vines hung on trees and in widely spaced rows, did not encourage the aphid” (p. 175). Measuring the area of vines and wine production in Italy in this period was very difficult as there were officially 3.5 million hectares of vines found in polyculture, and only 0.89 million as the sole crop in 1913.

50 Marescalchi (1924).

51 Loubère (1978:63–64). Giuseppe Acerbi in the early nineteenth century gives eighty-seven varieties used in Tuscany. Cited in Italy, Ministero dell’ agricoltura e delle foreste (1932:55). For Tuscany, see especially Biagioli (2000).

52 Loubère (1978:63–64).

53 For the Red Queen effect, see Olmstead and Rhode (2002).

54 Paul (1996:156).

55 Amerine and Singleton (1977:53).

56 Bioletti (1905:14).

57 Isnard (1954:179–87).

58 Roos (1900:130).

59 The producer was Jouarres, at Minervois. Barbut, cited in Loubère (1978:199).

60 Isnard (1954:204).

61 Roos (1900:56–65). This machine was used by the Compagnie des Salins du Midi.

62 Ibid., 209.

63 Isnard (1954:189–90). The British consul general noted that “this remarkable progress in the history of Algerian viticulture is due, I understand, to the untiring efforts of M. Brame, of Fouka” (1898:3).

64 Bioletti (1905:39). This author describes two differently types of machines: attemperators, which pumped water or other cooling liquids through a tube in vat; and refrigerators, which consisted of a spiral tube outside the vat, through which the wine was pumped, and which was cooled by a cold liquid on the outside.

65 Pinney (1989:353).

66 Jullien (1824:xv) defines muet as being “wine whose fermentation is stoped by sulphur.”

67 Bioletti (1905:50).

68 Trianes (1908).

69 A useful survey of the different methods is found in Castella (January 1922).

70 Marcilla Arrazola (1922:105).

71 Roos (1900:226).

72 Gayon (March 17, 1904, p. 294).

73 In 1903 it was estimated that the cost of construction and equipping a wine cellar with a capacity of 200 hectoliters was 4,500–5,000 francs, compared to 160,000–200,000 francs for one of 20,000 hectoliters. Using a depreciation rate of 6 percent, this implied an annual charge of 1.35–1.50 francs per hectoliter for the smaller one, against 0.48–0.60 franc for the larger cellar. The 200-hectoliter cellar required an additional 50 percent capacity (100 hectoliters) for fermenting vats, while the larger one only needed 20 percent more (4,000 hectoliters). The area of land was 50 m2 and 2,000 m2, respectively (0.25m2 and 0.10m2 per hectoliter), and the building costs were 6 and 4 francs the square meter. Roos, Progrès agricole et viticole, February 8, 1903, cited in Mandeville (1914:86–88).

74 Mandeville (1914:93).

75 Ibid., 75.

76 In relative terms, they were many fewer in Europe than the New World. In the Midi there were 130 wineries by 1903 with a minimum capacity of 10,000 hectoliters each, although this was equivalent of only one for every 180,000 hectoliters of wine produced, implying that smaller wineries remained the predominant form of production. In Algeria there were 53 large wineries, equivalent to one for every 145,000 hectoliters, compared to the 34 wineries, or one for every 40,000, in Mendoza, Argentina. Gervais 1903; my calculations; and Barrio de Villanueva 2008b, cuadro 1). The Midi’s harvest is taken as 23.4 million hectoliters in 1903.

77 Clarence-Smith (1995:157). For the efficiency of small-scale production of sugar cane, as opposed to the large economies of scale in its processing, see Dye (1998).

78 Galet (2004); my calculations.

79 Smith (1975:365).

80 La Gaillarde was the leading center in France in promoting the use of American vines. Already in 1889 it had 400 varieties, and this figure would grow to 3,500. From 1881 Gustave Foëx, author of the future classic of European viticulture Cours complet de viticulture (1886), became its director (Paul 1996:22–25).

81 Frader (1991:36, 69).

82 Paul (1996:14).

83 See Gide (1901:226–27).

84 Génieys (1905:38). Wines from the Midi were sold by alcoholic strength and color (AugéLaribé (1907:192).

85 Pech (1975:201–2). The CSM had 700 hectares of vines in 1900 and produced over 100,000 hectoliters. Its land was sandy and phylloxera free but used direct producers such as aramons and terrets, and massive amounts of fertilizers (ibid., 154).

86 The Credit Foncier lent an estimated 20 million francs to growers between 1882 and 1902, equivalent of approximately 10 percent of the total cost of replanting in the department, assuming a cost of 1,500 francs per hectare. The bank favored larger producers for economic and technical reasons (Postel-Vinay 1989:169).

87 Génieys (1905:38) notes that “the period between 1890 and 1900 saw the triumph of the Aramon, planted on the old water meadows and trained on wire trellises and pruned according to the Guyot, Quarante, Royat, methods.” See also Gide (1901:218–19).

88 Augé-Laribé (1907:118).

89 Smith (1975:371).

90 Guyot (1865:37), English edition. See also Loubère (1978:83) and Frader (1991:31).

91 Guyot (1861:19).

92 Smith (1975) and Frader (1991:75).

93 Cited in Augé-Laribé (1907:119–22).

94 Isnard (1954:117).

95 Gervais (1903) and Isnard (1954, 2:518). There were a further 144 vineyards of between 50 and 100 hectares, and 746 between 20 and 50 hectares.