Chapter 10. Preparing the Organization

Imagine that you are setting out on a trekking expedition to a remote mountainous area. The first step in planning your expedition is to understand the landscape that you will be trekking on, and to plot the best route for your trek. Having done this, you then need to prepare yourself. You need to assemble your team and get them physically as well as mentally prepared for the trip. And you need to gather the supplies and tools that your team will need to survive and succeed. Without careful preparation, undertaking the trek would be dangerous, no matter how well you understand the terrain and the route.

Such is the case in planning your expedition to tap into the power of the Global Brain. In the previous chapter, we focused on understanding the terrain of opportunities, and deciding on a course of action for your organization. After you have identified the opportunities, you need to look inward and ensure that your organization has the capabilities it needs to capitalize on the opportunities.

In this chapter, we offer advice on how to make your organization “innovation ready.” We consider two components of a firm’s readiness for network-centric innovation initiatives: organizational readiness and operational readiness.

Organizational readiness refers to the people dimension of the capabilities needed for network-centric innovation. Essentially, it is about creating the right environment within the organization to encourage and support participation in network-centric innovation. This includes creating an “open” mindset, getting leadership on board, creating the appropriate organization structure, and communicating the innovation strategy internally and externally. Operational readiness refers to the process dimension of the capabilities. This includes designing processes for project selection, partner selection, risk management, integrating internal and external processes, and management of intellectual property rights. Operational readiness also involves creating the tools and technologies to support externally focused innovation and metrics to track your progress and assess your success.

The starting point for readying the organization is to change the mindset of the organization regarding network-centric innovation. This is the most important and the most difficult step in organizational readiness because it goes against the entrenched proprietary mindset that most organizations have regarding innovation. Let us look at the challenges in changing the innovation mindset, and how firms can overcome these challenges.

Opening Your Organization’s Mind

As we noted in Chapter 1, “The Power of Network-Centricity,” a central challenge for organizations embarking on a network-centric innovation initiative is to create a mindset that encourages looking outward and becoming more accepting of the ideas of outsiders. This is especially challenging when intellectual property and secrecy is at stake. Consider InnoCentive, the much-talked about “innovation marketplace” created as a spin-off from Eli Lilly several years ago. Dr. Alph Bingham, a founder and board member of InnoCentive, recalls the stiff resistance his team faced within Eli Lilly. When they presented the concept internally, the internal R&D and legal teams balked at the heretical notion that Lilly’s secret R&D problems would be posted online for the whole world to see. It was a heretical idea for scientists used to the image of “Skunk Works”—the legendary R&D organization within Lockheed where scientists and engineers toiled away in complete secrecy, walled out from the world and even from within the other parts of the organization. But the InnoCentive team persisted, and today, the concept of an open marketplace for innovation seems quite logical.

The responsibility for creating the “open” mindset rests largely with executive management, and it begins with the CEO of the company. In our experience, organizations that have made headway have often been mandated by the CEO to adopt a collaborative and externally focused mindset. It helps if the CEO publicly declares the intent and the goals for the firm to change its innovation strategy. This leaves people with very little choice but to get on board. For example, when P&G’s CEO A.G. Lafley proclaimed in 2000 that half of P&G’s new products would come from its own labs and half would come through them, it catalyzed people into action.1 As Tom Cripe, associate director of P&G’s External Business Development (EBD) group told us, “Our senior management has been very focused on this and they repeat it at each and every internal forum, and when they do that, it slowly grows on you, and helps to evolve a culture where people are more receptive to ideas coming from other places.”2

Overcoming the “We Know Everything” (WKE) Syndrome

Malcolm S. Forbes said, “Education’s purpose is to replace an empty mind with an open one.” So it goes with changing the innovation mindset. There is no greater enemy of learning than our overconfidence that we already know everything. Indeed, we are prisoners of what we know, because we tend to reject other peoples’ ideas when we believe we know all we need to know. A lot has been written about the “Not Invented Here” (NIH) syndrome—a culture that rejects ideas, research, and knowledge because it wasn’t originated within the organization. We look at this syndrome somewhat differently as the “We Know Everything” (WKE) syndrome, which we define as an organizational mindset that is closed to external ideas and knowledge because of the belief that internal knowledge and expertise is sufficient, and there is no need for importing external expertise.

The WKE syndrome is particularly dangerous for companies with a long and illustrious history of R&D accomplishments, such as Boeing, Kodak, 3M, DuPont, Merck, Motorola, Sony, and IBM. These companies practically invented their industries, and rightfully consider themselves to be the pioneers of their markets. They have also been associated with legendary innovations, and they have within their ranks some of the most talented scientists and engineers. Furthermore, in many of these organizations, the average tenure of researchers and engineers is quite long, and they have a tremendous amount of accumulated knowledge and experience. In such an organization, it is hard to believe that someone outside the organization can tell you something you don’t already know!

Consider 3M as an example. It has more than 6,000 scientists and researchers in its R&D setup working in 30 core technology or scientific areas ranging from adhesives, abrasives, and films to fiber optics, imaging, and fuel cells. These scientists work at R&D units at different levels of the organization—in the division labs, in the sector labs, and in the corporate labs. 3M has such deep scientific in-house talent that its scientists and engineers have formed several informal groups or networks based on their specific research areas to share their knowledge and research findings (akin to IEEE-type forums inside the company). 3M has struggled to overcome the WKE syndrome. Explicit acknowledgement from senior management—particularly the CEO or the CTO—that the WKE exists in their organizations can be the most important first step in this regard. In the case of 3M, Jay Ihlenfeld, senior vice president of R&D, played a key role in helping the organization to acknowledge this challenge and to start working on addressing it.3

It is also very likely that even the mere admission of such a problem, let alone specific actions to overcome it, is likely to create confusion and resistance within the organization. For example, when Merck’s new R&D chief, Peter Kim, acknowledged that the company’s internal talent was unlikely to be sufficient to replenish the company’s R&D pipeline for the future, he immediately sparked protest within the scientific establishment of the company. Merck R&D veterans such as Emilio Emini (senior vice president of vaccine research), Kathrin Jansen (a research manager who played a key role in the development of the cervical cancer vaccine), and Scott Reines (a top researcher in psychiatric diseases) all left Merck. One of Kim’s main jobs was to instill in Merck’s R&D setup the notion that it didn’t know everything. And, more importantly, there was a need to treat smaller companies looking for potential collaboration with Merck with respect and humility—not as an “arrogant” partner. Specific counseling sessions were conducted—in the words of Dr. Merv Turner, Merck’s head of licensing, “We sent our guys to charm school.”4

Such interventions done by senior management can instill a mindset that acknowledges the limitations of the company’s internal knowledge base and is more inviting of external ideas.

The Power of “Letting Go”

The flip side of the WKE syndrome is the firm’s ability to “let go” of its proprietary knowledge and intellectual assets, or cede control over the innovation process in order to advance the overall innovation agenda. This action is particularly challenging for organizations used to controlling every aspect of their innovation activities as well as “hoarding” every single intellectual property asset.

As companies collaborate with external entities (whether other firms or individuals) in innovation initiatives, they have to become comfortable with the notion of loosening control over the innovation process. And they have to become comfortable with the idea that they have to contribute some or all of their “proprietary” knowledge to enhance the innovation effort. Such a need to let go might come as an unpleasant surprise to senior management, too. In Chapter 2, “Understanding Network-Centric Innovation,” we described IBM’s realization of this need while working on developing the first Olympics Web site (for the Atlanta Olympics). In the words of IBM’s Irving Wladawsky-Berger, who led that project in the mid-1990s, such realization can be momentous.

I remember when we did the Web site for the Atlanta Olympics in ’96. My people who did that Web site used Apache instead of IBM’s proprietary product. They reported to me at the time and I said, “Well, why are you using Apache?” And they said, “Because it’s much better. You want a good Web site or do you want to push your own product?” And, I said, “No, we must have a good Web site, because nobody cares what the stack is. They want the Web site to work well.” And this was the first time anybody had put up Olympic results on a Web site. So we really wanted to make sure it worked. And eventually they said, screw it. Let’s ditch the IBM product, which has almost no market share and is inferior, and join forces with Apache. At the time, this seemed revolutionary. Now you look at that and you say, it seems to be common sense.

The concept of “letting go” is something that an organization has to get comfortable with over time. In fact, some companies realize that they are letting go of things that they never really did control as much as they thought they did. There is an illusion of control that is greater than the reality. However, even if it is an illusion, getting everybody in the organization to acknowledge it is a challenge for senior managers. And, as the example of IBM showed, sometimes it might also percolate from scientists and engineers working on the project up the hierarchy to senior managers.

Preparing the organization to adopt such a mindset requires the senior executives to communicate the benefits of letting go. This process becomes more challenging when the expected returns from letting go are not contemporaneous or even in the same product market or business division. In other words, the payoff from letting go can be distant in both space and time. Furthermore, often the very act of letting go might in the short term disrupt the firm’s existing revenue stream making it even more painful and increasing the resistance within the organization. Thus, the ability of the senior management to see the broader innovation agenda and communicate how “letting go” can actually prove to be beneficial (or even necessary to sustain the growth of the firm) becomes crucial.

An analogy from parenting might help illustrate the challenge and the benefits of letting go. As a parent, you might have the illusion of control over your child’s aspirations, careers, and interests, and so letting go can be quite difficult. However, you really don’t have as much control over your child as you think you do. And the more you let go, the greater the confidence and autonomy you build in your child. Similarly, for an organization, the more it is able to let go of its control or knowledge in an innovation initiative, the more it will likely gain from the participation of collaborators.

Structuring the Organization

After a firm achieves an enlightened innovation mindset, the next aspect of readiness is to create the appropriate structure for the organizational entity that leads network-centric innovation. In this regard, we have encountered two frequent questions, “Do we need to have a dedicated unit to lead our network-centric innovation initiatives?” and “Should we create a new organizational unit or use our R&D unit (or other existing organizational units) to provide this leadership?” Our answer to both of these questions is—it depends!

In some firms, existing organizational units (for example, corporate R&D unit, business development unit, and so on) can evolve or transform to spearhead the network-centric innovation initiatives. In other cases, new units and new positions need to be established to provide the leadership. Three factors shape such decisions:

• Does the company have a history of participating in collaborative R&D ventures?

• Is the innovation space the company is mostly focused on for collaboration clearly defined or more diffused in nature? Further, how diverse are the company’s innovation partners likely to be?

• Are the initiatives being considered by the company related to its existing products and services or to new/emerging business areas?

Let us start with the first issue. If a company has a long and considerable collaborative experience (for example, joint ventures in R&D, technology consortiums, and so on), then it is likely that elements of the collaborative spirit as well as associated competencies are present within the organization. If so, there is no need to create new organizational units dedicated to network-centric innovation initiatives. Instead, the firm can rely on transforming one or more existing units that already has the experience to take on the new responsibilities related to leading and coordinating the company’s network-centric innovation initiatives.

A good illustration of this collaboration history is P&G’s EBD group—a unit with more than 50 people. EBD has shouldered a considerable part of the responsibility for P&G’s Connect+Develop initiative right from the early stage in the late 1990s. The EBD group already had considerable experience in interacting with external entities for technology commercialization and licensing deals, and as such, it only needed to evolve further to interact and coordinate with a larger number of external partners (including product scouts, innovation capitalists, and so on). Other business units utilize the services of EBD to seek out external innovation opportunities, negotiate deals, and interact with external partners, and in return, these internal clients contribute to EBD’s budget. Thus, in the case of P&G, its prior collaboration experience enabled it to transform existing organizational units such as EBD to assume the responsibility to coordinate the network-centric innovation activities.

On the other hand, if a company’s collaborative experience is limited or not widely dispersed across the organization, creating a new unit may be necessary to signal the shift in the company’s approach to innovation. This is the approach that Kodak adopted. The company has a 100-year old tradition of being a highly vertically integrated company with abundant internal technological resources. However, as Kodak started undergoing a major transformation from being a chemical/analog company to becoming a digital company, the company realized it couldn’t make this shift on its own, and that it needed to be much more aggressive about “going out” to get the breakthrough ideas. So, in recent years, Kodak has created new organizational units and new positions, like the External Alliance Group, to facilitate the development of new partnerships with external innovation networks. The new organizational units are helping Kodak break down the cultural barriers related to externally sourced innovation and establish systems and processes to identify and collaborate with a wide range of external partners, ranging from early stage firms to individual inventors to academic scientists.5

The second issue relates to the nature of the innovation space and the diversity of partners. Evidently, if you are participating in the Orchestra model, much of the innovation space is clearly defined and you are likely to interact with a relatively less diverse set of network partners. In this context, the role of a dedicated organizational unit would largely be to establish the standard set of practices that the different parts of the company need to follow. While the unit might assume a strong leadership role in the initial stages, as the processes and practices take root in different parts of the organization, it can step back and pursue a more supportive role.

On the other hand, if the company is participating in the Creative Bazaar model or the Jam Central model, the uncertainties associated with the innovation space and the need to interact with a much more diverse set of partners demand a very different role for the organizational unit responsible for network-centric innovation activities. First, as companies like IBM and Sun have realized, partnership with innovation communities and other such entities often involve spontaneous or unplanned interactions between a company’s employees and such external partners. A dedicated organizational unit can help to increase the coherence of these interactions and to facilitate the interactions in such a way that they advance the company’s innovation agenda. More specifically, to ensure that value generated through these interactions are captured and do not “fall through the cracks.” The more diverse the set of innovation partners, the more diverse the set of innovation capabilities needed. So another role for the organizational unit is to seek out and assemble capabilities from different players. In sum, in a diffused innovation space and with a diverse partner network, the dedicated organizational unit acts less as a process enforcer and more as a clearinghouse for best practices and skills.

The final issue to consider in defining the appropriate structure is whether the innovation initiative relates to the company’s existing markets (products/services) or does it take the firm into very new arenas? If the firm is staying close to existing markets, then it is likely that the company will have to create strong linkages between the organizational unit spearheading network-centric innovation activities and the R&D units within individual business divisions associated with those existing markets/products. For example, 3M has focused on using its corporate R&D unit to lead its network-centric innovation activities. However, given that many of these initiatives relate to existing products and markets, the early focus has been on bringing together the divisional R&D units to develop a coherent plan for network-centric innovation.

On the other hand, if the initiatives relate to emerging or new business areas, a very different structure might be needed. For example, in the case of DuPont, the bio-based materials area is one market where the company intends to actively pursue network-centric innovation approach. Thus, it has created new positions to coordinate external innovation sourcing activities in the bio-based materials business area. These new structural arrangements are not yet tied to the R&D units in other business areas. However, it is expected that as DuPont’s innovation strategy expands to other corners of the organization, eventually those linkages would also be established.

Overall, we believe that dedicated units are likely to be helpful to spearhead and provide coherence to a company’s network-centric innovation activities. However, the extent of influence and control such organizational units should exercise depends on the nature of the firm’s portfolio of network-centric innovation initiatives.

Leading and Relating with Partners

When participating in network-centric innovation, companies might often need to lead their networks and at the very least, relate well to other network partners. In the four models of network-centric innovation that we discussed in this book, the nature of such leadership and relational capabilities needed are quite different.

Earlier, we discussed how, in the Orchestra model, a company such as Boeing has to exercise leadership in ways that bring coherence to the goals and activities of the network members and instill a sense of fairness and predictability in the processes related to value creation and value appropriation.

In our discussion with managers in such companies, one leadership theme has come again and again to the forefront: the need to project an image of decisiveness without implying a “high-handed” approach to decision making. Such decisiveness can relate to one or more of the following issues: who gets to play, what is the architecture that will guide the play, and how will the play proceed?

Indeed, most of the companies that play the role of an adapter (complementor, innovator) in the Orchestra model seek decisiveness from the network leader. Decisiveness helps them evaluate the opportunity to participate in the network with much more clarity. And it helps them plan their contributions to the network in ways that lend stability to their own goals and strategies.

Even in the case of the Creative Bazaar model, although the company playing the role of the innovation portal might not interact directly with all the network partners, its ability to create a level playing field for all participants is a critical element of leadership. The leadership role includes bringing more transparency to the innovation process—for example, making explicit what the company is looking for, how it would evaluate the innovative product ideas, and how it would go about bringing such ideas to the market. While companies such as Kraft have put out calls on their Web sites for customer participation in innovation, the emphasis should be on informing the inventor community about how that process of such innovation sourcing will unfold.

In the two community-led models—Jam Central and MOD Station—while a company might not play a direct leadership role, it can still provide considerable support to the community innovation goals and thereby offer an element of more indirect leadership. In this case, leadership is more like good citizenship. After the leader gains the trust of the community and is accepted into the fold, the community members expect it to contribute towards the innovation agenda. In some cases, employees of the company might play leadership roles in the community based on their own individual expertise and capabilities—for example, some of IBM’s employees play such roles in the Linux community. In some other cases, contributions might take the form of harnessing the company’s expertise in innovation management for the benefit of the community-led project. For example, some of the large pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer and Eli Lilly have started making such contributions to the community-led innovation projects in the biomedical industry.

Turning to relational capabilities, two important themes run through the different models of network-centric innovation.

The first theme relates to the potential asymmetry in power and resources between the larger and the smaller participants or network members in all four models of network-centric innovation. It is obvious in the cases of both the Orchestra and the Creative Bazaar models. It is even evident in the community-led projects, too, as members range from individuals to large companies to non-profit entities. As such, an important relational capability is the ability to interact with a diverse set of partners with a varying extent of resources and influence on the innovation process.

As one manager of a large consumer products firm put it, “the first competence that we have focused on developing here is to be able to interact with our smaller partners without making them feel overwhelmed. We don’t want to be perceived as the 800-pound gorilla trying to steal their ideas—rather we want to come across as the senior partner who has the responsibility to look out for the welfare of all of our partners, including the smaller firms. And, we spend considerable effort in educating our managers as to what this means with regard to their day-to-day interactions with our partners.”

Another theme relates to the ability to build trust through more open communication and interactions. Again, trust is equally important in the Orchestra model as in the Jam Central model although the mechanisms to build such trust among network partners might vary. When Dial, Inc. acquires the help of national inventor associations to communicate to individual inventors, it is focusing on building such trust with its potential contributors. Similarly, when Boeing builds an extensive IT-based virtual collaboration system to enhance information sharing among its partners, it is focusing on facilitating trust-based interactions in the network.

Or as P&G has discovered in playing the role of the innovation portal, trust builds with each additional interaction with an external partner. The company calls this the Weed’s law6—“The second deal with a partner takes half the time as the first one did. And, the next deal takes half of that time, and so on....” As we discussed in Chapter 5, “The Orchestra Model,” cultivating relationships with a selected set of innovation capitalists and other intermediaries helps P&G to use the mutual understanding and trust developed through repeated interactions to accelerate the overall innovation process. Thus, the ability to identify appropriate mechanisms to build such trust in different contexts can critically shape the success of a firm in network-centric innovation.

Managing Dependencies by Staying Flexible

By definition, network-centric innovation creates dependencies between the firm and its collaborators—dependencies on innovation plans of other partner companies and dependencies on the capabilities of external inventors and other such entities. For example, a company that develops a software application to run on Salesforce.com’s AppExchange platform is joined at the hip with the platform and its future. Similarly, when an innovation capitalist such as Evergreen IP decides to focus on a particular market (say, toys) and cater to the innovation needs of a selected set of large client firms, it is in effect creating a dependency that links its portfolio of projects with the market needs of its clients. Even in the Jam Central model, when companies commit to a particular community-led project and start contributing resources and expertise to move the innovation forward, they create dependencies that might be less explicit, but no less relevant. So it is important for a firm to acknowledge such dependencies and create sufficient flexibility in its strategy to manage the associated risks.

One dimension of flexibility relates to the innovation assets that the company contributes to the innovation effort. The ability to identify alternate deployment opportunities for such assets can enable the company to reduce or manage the dependencies on the network-centric innovation project. Recall Boeing’s 787 development project. Many of the new technologies being developed by the Japanese firms also involve deeper expertise that those companies could apply to other projects—particularly, their own independent initiatives in aircraft manufacturing.

Another approach to bring flexibility to the innovation strategy is to participate in more than one innovation network, if possible. Hedging one’s bets might allow a company to balance the associated risks and manage the technological and market dependencies. For example, some of the companies building applications on Salesforce.com’s AppExchange platform have incorporated standards and architecture that enable them to port add-on solutions to other customer-relationship management (CRM) solutions and thereby reduce their risk. The objective of such an approach is to manage the “distance” or separation between the company’s own innovation goals and the goals of the network-centric innovation projects it participates in.

We now turn to the second half of preparing the organization—operational readiness for network-centric innovation. We start with the processes that are needed to support the innovation effort.

Processes to Support Network-Centric Innovation

When most companies decide to look outside for innovative ideas, more than likely such initiatives would start out in an ad-hoc fashion. However, as more and more resources get committed to such initiatives, the need for clearly defined processes soon becomes apparent. Unless basic processes are established to guide and manage the company’s participation in external innovation initiatives, the organization’s ability to derive returns from such activities can be seriously hampered.

Our discussions with managers in companies such as 3M, DuPont, Unilever, P&G, and Kodak lead us to conclude that establishing processes early in the evolution of the firm’s network-centric innovation initiatives is critically important, as this helps bring discipline to the innovation activities. Although the specifics of the different processes and their implementation depend on the particular organizational context, we point to some generic processes that are needed to support network-centric innovation (NCI).

The most important process is the selection of business areas within the company that would be most appropriate for pursuing network-centric innovation initiatives. How should the company decide its nature and level of involvement? Who should make such decisions? What criteria should be considered in making such a decision?

Another focus for NCI processes should be the selection of external innovation networks and network partners. It is critical that a company has a coherent set of policies for selecting its partners (whether it is an individual firm or an innovation community) that it could implement organization-wide. Large companies may already have established processes for selecting partners for joint ventures and technology alliances. For example, 3M has a steering committee that evaluates all potential candidate projects for external collaboration and selects the most suitable based on a set of criteria, including the ability to define parameters for success and relevance to business. As the diversity of partners increases, such processes might need to be modified to include a host of other factors that might not have been of importance in one-on-one partnerships. Typically, such processes should consider factors such as the company’s prior relationships, complementarity of technology/expertise, and so on.

Third, processes also need to be established to identify and manage the risks associated with participating in network-centric innovation projects. Participating in community-led innovation projects poses different types of risks than participating in innovation networks that the company leads. For example, in entertaining ideas from amateur inventors and customers, there are IP-related risks and companies need to institute processes to mitigate these risks. On the other hand, when participating in an open project such as Linux or TDI, a company might allow its employees to make intellectual contributions. Different types of risks are associated with this scenario. Thus the nature of the risk varies with the type of innovation project. Some of these risks are likely to be those that the company has not faced before. Also, many of the relationships the company creates as it pursues its network-centric innovation agenda might require careful consideration of the legal implications. It is a good idea to institute processes to vet the different projects for the legal issues involved.

In addition to the preceding areas, processes might also be established to manage other aspects of a company’s participation including sharing knowledge with external partners, coordinating innovation activities with external partners, and managing relationships with a diverse set of network partners.

The overall objective of the process infrastructure should be to enable the company to use a uniform yardstick to monitor and measure performance in the NCI activities across the different business units of the organization and to ensure a level of repeatability in such performance.

Deploying Tools and Technologies

Over the past few years, a wide range of tools and technologies to support collaborative innovation have been created. Some of these tools facilitate communication and knowledge sharing among network members while some other tools enable coordination and management of collaborative innovation processes.

As we saw earlier in the book in the case of Boeing and its development of the 787, the use of appropriate information technology (IT) tools can significantly enhance the quality of collaboration among partner firms and lead to more effective participation in such external innovation projects. Similarly, in the TDI project, the Web-based infrastructure provided by the non-profit organization TSL was instrumental in facilitating the collaboration among the scientists and other participants of the network.

IT-based tools can be used in four areas of network-centric innovation:7

• They can be used as process management mechanisms to instill structured product development processes and to bring a level of rigor and stability to the innovation activities. Although some of the tools might implement generic and industry-specific process models (for example, the Capability Maturity model in the software industry or the Stage Gate model in product development), several proprietary process models also exist (for example, PACE). These tools and technologies enable network members to integrate their innovation processes without losing control over them.

• They facilitate basic project management functions—scheduling, coordinating, and managing resources related to a complex project, whether it is an Orchestra model project like the Boeing 787 or a Jam Central project like TDI. Some of these tools provide a virtual “command center” or “war room” with access to all project information through a common interface.

• They support information sharing among the different network members. They utilize different data and information standards (for example, ISO-STEP) to handle different types of information (including graphics, audio, video, and so on). Some of the tools also offer more versatile facilities capable of combining structured and unstructured information in real-time.

• They provide communication support ranging from facilities for a community of innovators to come together to highly secure forums for a defined set of partner firms to interact and share documents.

Although these tools and technologies can be implemented separately, there are some comprehensive tools that include most of the preceding functionalities. For example, Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) tools provide a wide range of features and functionalities to support network-centric innovation projects, particularly in the Orchestra and the Creative Bazaar models. In particular, functionalities related to project resource management, product platform management, product data management, and collaboration management assume considerable significance in the network-centric innovation project context.

For example, in the aerospace and defense industry, Northrop Gunman uses PLM solutions to support its collaborative development of the U.S. Navy’s next-generation destroyer. The project, a good example of the Orchestra model, involves multiple partners and the company utilizes PLM solutions from Dassault Systems (a leading PLM solutions provider) to support its collaborative design and development activities.8 Similarly, Herman Miller (the office furniture manufacturer) has implemented PLM solutions to support collaborative design activities between the company and its partners (including customers and dealers).9

Although PLM and other such tools might vary in their features and functionalities, the key issue here is how well those features support the network members to achieve the overall innovation goals. The more integrated the tools are with the underlying innovation processes in the network and the capabilities of the network members, the greater the potential returns from such tools. Thus, the bottom line for companies is to use these technologies to devise an integrated innovation environment that embraces the network members and brings coherence to their activities and contributions.

Measuring “Success”

An important element of operational readiness is the ability to evaluate the company’s performance and returns from network-centric innovation. This ability demands the creation of an appropriate portfolio of innovation metrics.

As the old adage goes, “Be careful about what you measure.” Measuring the wrong thing could lead a company down the wrong path. For example, counting the number of partners might give a false sense of the intensity of the collaborative activity of the company. Similarly, counting the number of patents produced through collaboration might again give a wrong picture of innovation success because patents don’t “pay the bills.” Thus, identifying the right set of innovation metrics is of utmost importance.

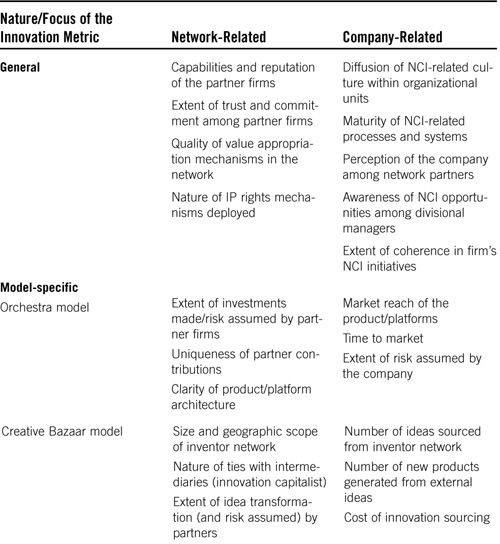

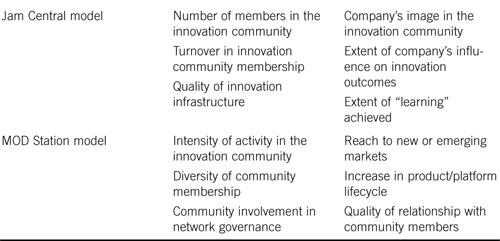

Network-centric innovation metrics differ in nature and focus. Some metrics are more generic and apply to all models of network-centric innovation, while others are specific to the model the company participates in and the role it assumes. While some metrics are defined at the level of the innovation network, others focus on the company and reflect the impact of the company’s participation on its internal activities and outcomes.

Table 10.1 provides an inventory of the metrics that fall into each of these categories. Note that this list of metrics is only meant to be representative, and not exhaustive.

Table 10.1. Metrics for Network-Centric Innovation (NCI)

The first set of metrics relates to the overall network. These metrics allow a company to evaluate whether it is partnering with the “right” network and might also indicate when the company might have to rethink its collaboration strategy. For example, for a company such as Dial, Staples, or P&G that plays the role of an innovation portal in the Creative Bazaar model, a valuable metric would be the reach and geographic scope of its network—the number of inventors and intermediaries that the company has been able to reach out to. Similarly, for a company playing the role of innovation sponsor in the Jam Central model, a useful measure would relate to the stability of the innovation community—the number of members in the community and the average turnover in membership. Such measures indicate the overall quality of the network and inform on the current and future innovation potential of the network, and thus could help a company to continuously evaluate whether it is partnering with the right set of external entities.

The second set of metrics, which relates to the impact of the collaboration on the company, indicates how well the company is fairing or gaining from its participation in the innovation project. Going back to the Creative Bazaar example, the number of external ideas entering a company’s product development pipeline or the number of new products that can be traced back to such external sources indicates the clear and the most direct impact of the company’s participation in the network. Similarly, a company playing the role of innovation catalyst might consider the number of new markets that it has been able to expand as an indication of the impact of its participation in the network.

Some of the company-specific measures could be more generic and relate to the internal innovation infrastructure or capabilities. For example, an audit of the company’s internal innovation processes—process maturity—might indicate its overall preparedness to identify and exploit different types of network-centric innovation opportunities. Similarly, perceptual measures can also be used to understand the company’s overall performance. For example, measures that capture the company’s image among network partners could prove to be very useful in evaluating and building relational and leadership competencies. Similarly, internal measures that reflect the extent of managers’ awareness of network-centric innovation opportunities might indicate the cultural and behavioral issues that might impact the company’s performance in network-centric innovation.

As Table 10.1 shows, a company can utilize a range of measures. Given that each measure provides a unique view or perspective of success in network-centric innovation, it is imperative that a company adopt a portfolio of such measures. Most importantly, the selection of the metrics should reflect the company’s desired focus in participating in network-centric innovation.

Conclusion

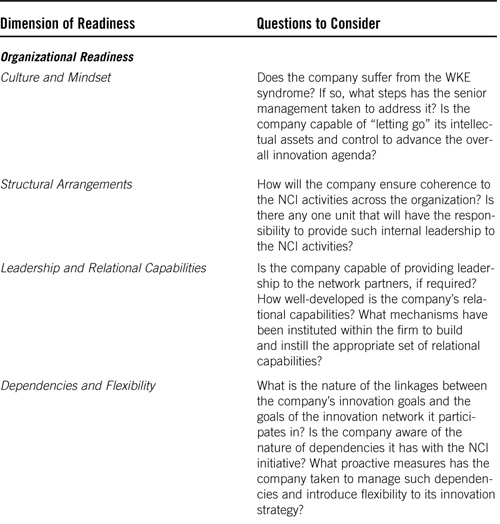

In this chapter, we considered many of the issues that companies have to carefully address to prepare their organization to navigate the network-centric innovation landscape. Table 10.2 captures these different issues.

Table 10.2. Dimensions of Network-Centric Innovation Readiness

As we noted in the beginning of this chapter, our task here has been to identify the important dimensions of such network-centric innovation readiness. As each individual company charts its own path in the network-centric innovation landscape, it will need to acquire the particular set of resources and capabilities that would enable it follow that unique path. With this focus on organizational preparedness, we come to the end of our journey that we started in Chapter 3, “The Four Models of Network-Centric Innovation,” by describing the landscape of network-centric innovation.

In the next chapter, we broaden our horizon and consider the global context for network-centric innovation—specifically, the opportunities and potential for companies in emerging economies like India, China, Russia and Brazil, to participate in network-centric innovation and how large companies can leverage talent in emerging economies for innovation.