8. The Challenge Driven Enterprise Playbook

“The price of success is hard work, dedication to the job at hand, and the determination that whether we win or lose, we have applied the best of ourselves to the task at hand.”

—Vince Lombardi

Overview

Part I, “Challenge Driven Innovation,” discussed the inherent limitations of traditional innovation models and then provided a theoretical and applied framework for firms to substantially improve their innovation effectiveness going forward. The work of well-known business leaders and world-class academics, the authors’ observations from years of business experience with both unwieldy bureaucracies and with emerging open innovation marketplaces, including InnoCentive, meaningfully informed the practical approaches promoted. Chapter 6, “The Challenge Driven Enterprise,” and Chapter 7, “Transformation,” introduced CDE and discussed at length the issues and stakes to be considered by the CEO and Board of Directors as they contemplate transformational change. This chapter provides a general and actionable framework for planning and initiating the requisite corporate transformation. In addition, a number of techniques and considerations based upon years of field experience are identified.

The Playbook

In football, the playbook is essential, enabling the orchestration of many players in highly dynamic game situations. Its actual utility is in its simplicity, economy, and modular form. By predefining both general and special purpose plays, the coach can direct the team to execute against most any strategy in a highly efficient and coordinated fashion. And importantly, the coach can flexibly adjust the plays to react to emerging challenges and opportunities on the field. The goal in assembling The CDE Playbook is to provide a similar toolset for implementing the Challenge Driven Enterprise that leaders can adapt and apply as needed. The playbook is intended to be reasonably comprehensive and may be used as the basis of an overall plan for the enterprise. It is important, though, to recognize that every organization is different and that significant judgment should be applied. Assume that you as the coach must choose the plays from the book that make sense in your organization.

The analogy of football is actually a powerful one. While the focus in this chapter is the playbook, it should not be lost on the reader that every game has an uncertain outcome. Winning is a function of the strategy of game play, resilience and talent of the players, preparedness, and esprit de corps of the team—indeed, many factors, obvious and subtle. Great coaches consider every dimension and strive to leave little to chance. Now the rules of the game are changing and the coach must rethink everything. But there is one constant; it is still about winning. And great coaches know how to adapt and win.

The CDE Playbook is organized into seven sections that are broadly applicable and logically sequenced, recognizing that a number of these activities will be going on in parallel and that different parts of the organization may be executing against the playbook at various speeds and on different timelines. For example, some organizations will run pilot activities while they build the business case and secure “buy in” and approval from senior leadership, while others will take a top down enterprise-wide approach from the onset.

Challenge Driven Enterprise Playbook

I. Board of Directors and C-Level Commitment

II. Promote Early Trial and Adoption

III. Virtualize the Business Strategy

V. Create and Empower CDE Task Force

VI. Align and “Ready” the Organization

VII. Select Enablers and Enroll Partners

Generally, the CEO and senior leadership roles are the focus in this chapter because it simplifies the discussion. However, there will clearly be cases in which senior managers, directors of the company, and others will drive the transformational change. It is understood that these concepts will be adapted as needed. Further, organizations should not hesitate to scale down the approach to divisions or departments, providing they recognize that a CEO sponsored transformational agenda is the ideal approach recommended by the authors. Use of the playbook is equally valid in other sectors, such as government, education, and even the Not-for-Profit (NFP) world. Finally, we provide guidance and ideas at the end of the chapter on translating the playbook to various applications.

I Board of Directors and C-Level Commitment

Not surprisingly, this first section of The CDE Playbook may well be the most important. The resolve and determination needed to successfully evolve the organization is considerable and not without risks. CEOs and Boards of Directors must commit in no uncertain terms and see it through to the end. But, before the CEO pronouncements are published in The Wall Street Journal and questions are answered on quarterly investor calls, the Board of Directors and CEO must intensely consider the Challenge Driven Enterprise and all the implications. The actual decision to be made is whether to substantially reengineer the enterprise, adopting CDE as the framework on which the business will operate, well into the future.

Planning, Budgeting, Measuring, and Self-Funding

Resources, including capital and personnel, must be allocated and available for the transformational efforts needed to be successful. Planning and budgeting are significant considerations, yet we can provide only guidance here in terms of broad generalities. Certain activities can be managed for modest investments of resources and money—for example, pilots and strategic planning. At the other end of the spectrum, “reengineering the enterprise” is a substantial undertaking and will involve considerable efforts and costs. Finance will “own” the multiyear plan to manage the economics and metrics: modeling benefits and costs, building the budgets, ensuring accountability and transparency, and instilling a measurement rigor into the organization. It also means finance will have a crucial role in the deployment of CDE, tracking progress, and reporting on gains to leadership and to Wall Street. It is worth noting that as mentioned in earlier chapters, many organizations have chosen metrics that actual perpetuate the current systems, rewarding the wrong behavior. A critical analysis of the measures appropriate for the company going forward is important in driving the needed change.

Dividends will begin to accrue surprisingly early in the transformation that can be directed toward later phases of the program. This represents a significant opportunity from a financial perspective, but also for corporate messaging. Gains from early investments will be reinvested and largely fund ongoing implementation as the company continually improves its competitiveness—a powerful message. We recommend building your plan and setting financial assumptions such that the transformation is entirely self-funding and potentially profitable in 3 to 5 years.

For some organizations, this is not only a significant investment in the future of the company, but it may also qualify as restructuring. And as such, there may be opportunities to apply beneficial accounting treatments to related expenses and, in some cases, you may quality for R&D credits or other inducements. You should use experts in financial accounting, taxation, financing, and other areas to uncover all the opportunities. The financial implications are significant and the technical expertise of the finance team will be tested, so the CFO should plan accordingly.

Rationalizing the organization, particularly in the context of this approach, creates another opportunity: Programs that run counter to the long-term objectives of the program should be considered for reductions or eliminated altogether, further freeing up capital to support the program. Why build a new factory when you will likely use contract manufacturing capacity available in Asia or elsewhere? Strategy and Finance should take the point on assessing the current portfolio of major projects to identify candidate expenditures that can be better applied, completely consistent with the principles of CDE. Consider viewing this exercise as its own Challenge: Which programs may be scaled back or canceled to generate $20MM annually, which can be applied to the CEOs mandate?

There is significant time and work in planning such an undertaking. Some organizations may begin with early trials and others will aggressively move right to full-blown reengineering efforts. The choice depends upon the corporate culture, resources, and the CEOs confidence in the organization’s capability to change.

Finally, organizations are exceedingly adept at judging the CEO and their level of commitment by how they allocate resources and their management attention. At the risk of hyperbole, bold means bold. Any less and the organization will discount the change from the onset and seriously handicap the likelihood of success.

Commitment

Enrolling the board, investors, employees, partners, and other stakeholders is vital. The CEO must enroll and engage all his constituents and bring them along as partners in the journey ahead. The Board must be sold on the long-term benefits, the risk reward tradeoffs, and the time table to deliver on the vision. Employee engagement is vital to the success of the initiative, requiring a significant and ongoing enrollment and communications strategy. Investors must understand how the economics of the business will change, expected short- and long-term implications to share price and dividends and other structural implications to the company’s financials. Partners must understand that the company will be going through a transformation, and for some partners, this will create opportunity. And there will be other stakeholders as well, running the gamut from the banks to the analyst community. The CEO must anticipate the reactions of all these entities and have a plan to enroll them as partners.

The potential conflicts that exist with CEOs, senior executives, and corporate boards making major commitments with long-term implications have already been discussed (the CEO Conundrum from Chapter 7). Leaders seek to capture upside while steering away from risk and instinctively avoid engaging in programs they believe could fail big, particularly when the benefits may be years away. And as a general rule, this strategy serves executives well. Unfortunately, this risk aversion can also lead to catastrophic failures (for example, the U.S. auto industry). Even when the future viability and competitiveness of a company or industry is clearly in question, executives often cannot bring themselves to make the really tough structural choices. Too often it takes a crisis to bring leaders and organizations to commit to change, as demonstrated during the recent recession. CDE represents an opportunity to remake the organization in the face of increasing competition, substituting an aging model for a new more agile, innovative, and efficient one. Organizations with real vision and courage opt for change well before staring into abyss. Some may never make the commitment. But for those that do, it is important that they fully comprehend the consequences—a significant reengineering of the enterprise which means rewriting the strategy, reallocating resources, and focusing significant leadership attention toward bringing the CDE to life for the organization. They must commit fully to the vision. After the decision is made and ratified by the Board, it is time to act.

II Promote Early Trial and Adoption

In any case, promoting pilots to demonstrate the potential for “open” and “networked” concepts to change the rules is a good strategy. This section discusses using trials most effectively to secure early learnings, create internal wins, and support adoption.

Creating early wins and success stories can capture the imagination of the organization and provide tremendous opportunities to apply the basic concepts and to learn from early trial. Coupled with the clear message from the top of the organization that change is coming, leadership and staff can see the opportunity not only to get on the bus, but also to help drive.

Utilize Challenges Strategically and Organize Events Around Them

You need to teach the organization about the concepts, while establishing the foundation on which broader programs and efforts will be built. Organizing challenge events for maximum effect can be incredibly effective at this stage. For example, enrolling the entire organization in identifying new product ideas or focusing an R&D group on proving out open innovation on an important high-profile project is both empowering for staff and will also create an excitement and buzz. Business development can be tasked to identify the potential partnerships to accelerate product innovation. There is no limit to the number or variety of events that could be constructed to illustrate and highlight the concepts behind CDE. However, focusing on a few events with broad visibility and high volume potential may have maximum effect. These pilots need strong leadership and sufficient resources to ensure success.

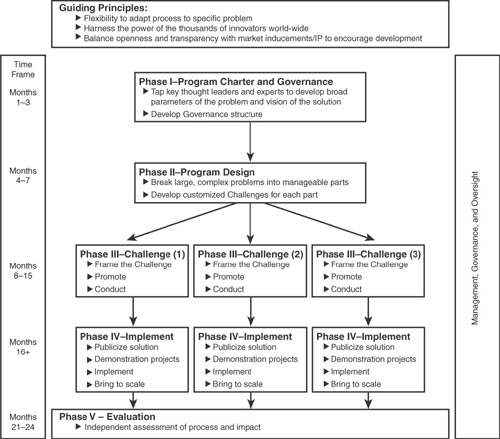

InnoCentive frequently designs programs for corporations. Figure 8.1 outlines a typical pilot structure for early stage Open Innovation adopters.

Figure 8.1. InnoCentive sample pilot structure

Source: InnoCentive

Further, this can be a crucible for understanding the scale of behavioral and cultural change needed in the months and years ahead and identifying gaps in capabilities and skill sets needed in the organization going forward. Thoughtful choices at this stage can have a big impact. But remember, the status quo will instinctively protect the status quo. If you want the organization to prove to itself the great potential inherent in breaking the mold, you need to give permission to employees in the organization, encourage them to take risks, and be vigilant in ensuring that bureaucracy and passive aggression does not impede employee’s efforts. Hand-picking leaders and projects to ensure success at this stage may be necessary.

Evaluate Business Impact and Document Learnings

Rigorously evaluate the pilot programs, translating the results into tangible business terms and impact. Properly designed, the measurements can have a strong economic basis and translate effectively to financial performance. CDE is about strategy and competitiveness. Resist the temptation to message the programs simply in terms of the numbers. Cost-savings, for example, is important and alone may justify the leadership focus, but it will not be sufficient to inspire the organization or to support the transformational vision. And it could actually work against the overall strategic message. In addition to the economics, relate the successes to advancing the mission in other tangible and intangible ways, for example, improving product time-to-market and beating out the competition or reducing manufacturing defects and thus improving customer satisfaction. Bringing a product to market in record time that was identified through partnership should be heralded as a coup for the company, and it signals that you don’t need to invent it to profit from it. This can keep the message anchored in strategic terms, while ensuring the economic basis justifying the overall program is intact and beyond question.

After the results are in, success stories should be promoted across the organization to maximize effect.

Promote the Successes

Successes are beachheads, early wins on which the larger programs will be built. They are the basis of many of the stories that will be told as the transformation builds. Promote not only the ideas, but also the divisions and departments that made them successful. Make heroes out of the leaders and practitioners. In doing so, you give further permission to think boldly in the organization. These are triumphs and are powerful portents of the change to come. Make these stories legendary.

III Virtualize the Business Strategy

At its heart, the CDE is an organization that has virtualized its business strategy and that expertly orchestrates the execution of its vision. It has transformed structurally and culturally to achieve its goals and to maximize shareholder returns. However, effectively translating those words into action requires more than just dedication and making assignments. It requires a compelling strategy with rigorous attention to detail and new structural, operational, and financial models of the business. Such an undertaking cannot be managed without risk. The prudent CEO invests heavily to ensure the strategy is comprehensive, risks are understood and minimized, and that progress can be metered and adjusted as the program progresses.

Establish Guiding Principles

Guiding principles establish a basis of expectation and a benchmark against which important decisions can be made consistently across the organization. By weaving CDE concepts into the principles, the CEO effectively distributes his expectations and delegates responsibility for CDE at the same time. The CEO should communicate these guiding principles frequently to senior leadership and with staff wherever possible.

The following example illustrates the point:

Sample Guiding Principles

We will...

• Orchestrate value creation through partnering, markets, and ecosystems

• Externalize functions, projects, and work wherever possible

• Eliminate fixed cost and infrastructure; and maximize capital flexibility

In a nutshell, these principles state that in the twenty-first-century enterprise, value is created by what you do that is of value to your customer and nothing more. How you do it, from research to manufacturing are secondary. Winning companies will be masters at orchestrating the people and networks to capture that value. And by doing so, they will create shareholder value.

Evolve the Business Strategy

This is an exercise not only on focusing on what’s important, but also on converting the organization from its bloated and inflexible “bureaucratic” form to the virtual “network” form with all its inherent benefits. And it can be both clarifying and liberating. Be careful, if the effort to remake the strategy is not focused, it runs a real danger of collapsing under its own weight. P&G committed to enabling every aspect of open innovation in a company that had been closed and inward focused; it did not rethink whether to sell toothpaste or how big the consumer products market actually is.

Ask provocative questions:

• Could new business opportunities be exploited if we had more resources at our disposal? What could that mean to the future of the company?

• Could we substantially reduce time to market for new products and features if we engaged innovators around the world in product development and R&D processes?

• Is it possible to improve efficiency without reducing customer satisfaction by shifting customer service and other services to companies that specializes in those capabilities?

It is understood that none of these are purely financial decisions of course, but recognize that power of challenging the process to push the potential benefits to the limits. Every area of the business represents an opportunity for reengineering.

Consider using experienced practitioners or consultants to assist the organization in virtualizing the strategy for one simple reason: They have no pride of ownership in the existing strategy of the company. For some organizations, the optimal approach will be to allocate senior strategy resources and those of trusted advisors to develop the initial guiding principles and high-level planning to drive the more expensive effort of redesigning the company strategy at which time using more traditional internal and external consultants and partners may be appropriate. In any event, it is vital that the senior team “own” the process at all times.

Model Long-Term Shareholder Value Implications

The strategy has been overhauled, early candidate projects identified, and the execution plans finalized, but it remains vital that all these efforts be tied to the long-term value of the company and directly to shareholder returns. It is understood that nothing is known with certainty; however, the financial rigor needed to operate in the CDE can be applied to the decision making even at this stage. For example, you can estimate the implications of the competition gaining five points of market share at your expense due to more inspired product innovation. The goal at this stage is not absolute precision. It is to objectively compare the organization as it exists today against the CDE vision and to translate the benefits for shareholders, analysts, employees, and other stakeholders.

Long-term shareholder value can be addressed qualitatively and quantitatively by focusing on the important strategic questions, thoughtfully valuing choices and options, and applying common sense thresholds to the analyses. Taken together, this can establish the case for virtualizing the business and do so in compelling terms. And in so doing, the CEO can create measurable and tangible goals for the organization. P&G calculated that it needed 50 percent of its innovation to come from the outside to continue to deliver on its growth in EPS commitments. And then it did exactly what it promised.

IV Establish the CEO Mandate

Successful CEOs focus the organization on a small number of key initiatives and some choose a single theme or strategy that defines their administration. The CDE can rise to that level, due to the strategic, structural, and competitive implications of its adoption. By making the CDE a mandate, everyone in the organization will understand the importance and commitment attached to this program by the CEO and the Board of Directors.

Jim Collins and Jerry Porras, in their book Built to Last, discussed the power of what they called Big Hairy Audacious Goals (or BHAGs) whose clarity and simplicity can drive impressive focus. They said “A true BHAG is clear and compelling, serves as unifying focal point of effort, and acts as a clear catalyst for team spirit. It has a clear finish line, so the organization can know when it has achieved the goal; people like to shoot for finish lines.”1 Examples of BHAGs potentially relevant to your organization could include commitments to “30% of innovation coming from the outside within 5 years” or “50% of the workforce being virtual or variable in 5–10 years.”

The use of simple and clearly articulated goals has a secondary benefit: it challenges the organization to think differently and boldly and reinforces strategy at every sounding. HR will ask, “Should we be hiring that many people if our goal is the virtual organization?” And manufacturing may ask, “Can we outsource manufacturing instead of building the next factory?” Elevating the CDE to that of a core strategy ensures that the entire organization understands the CEOs resolve and commitment to its success. And therefore, the entire organization will “own” the strategy and feel it has permission to challenge the status quo.

In communications, it is imperative that organizations tie CDE to long-term shareholder objectives and other key strategies of the company—for example, the need to improve time-to-market for products, to maximize capital available for investment in the business, or to react quickly to changing business conditions. When understood, this approach yields singular objectives that can compel both the core strategy and its adoption.

Enroll Senior Leadership

The senior leadership team must be unified in the vision and must charge forward to execute the strategy with all the zeal and passion of the CEO. This of course requires that they be fully enrolled as partners in the transformation. Their engagement is crucial and without their support, success will be elusive. The CEO should recognize that as the CDE principals are applied, the definition of senior management’s respective departmental responsibilities could be altered substantially. And they will be keenly aware of the implications. Further, the makeup of the senior team itself could change. The best advice is to sell the senior team on the vision and involve them in key elements of the planning. Be open and honest in describing the future state and their role in it and the potential new opportunities that may emerge. Make every attempt to find these leaders appropriate seats on the bus, but don’t be afraid to counsel out executives who will not or cannot adapt accordingly. The whole senior leadership needs to be on the bus or efforts will be compromised.

Clearly any transformation of this magnitude will have far reaching implications and the CEOs commitment to this initiative must acknowledge the need for substantial cultural change, only possible with the support of leadership. She must demand accountability and drive engagement using every tool at her disposal, including bonus programs, recognition programs, hiring, promotion, and firing (more on this later). These can be crucial to projecting and actualizing the mandate.

You must eliminate the ‘More is better’ management culture. Notions of bigger is better must be replaced with lean and mean. In fact less is more. As mentioned in the prior chapter, we’ve all been indoctrinated in the myth that bigger must be better in all things: headcount, budget, support staff, assets, and so on. This mentality must be broken, and the CEO has unique opportunity to reset these elements of culture, particularly management culture in the organization.

Communicate Clearly, Openly, and with Conviction

The CEO and senior team must couple their efforts with clear and transparent communication to everyone involved. Consider the importance of the CEO speaking to the business as part of an effective program to drive irrevocable change into the organization. The CEOs voice will not only communicate the importance and commitment vital at this stage, it will also help manage the organization’s natural anxiety that comes with any kind of change. This is not just an effort to reengineer the enterprise or to restructure spending; the CEO must convey a clear and unambiguous belief that this is vital to the future of the organization, and perhaps to the long-term viability of the company, and that new opportunity will emerge as a result. If the organization hears clear and transparent language coming in earnest from their CEO, it can understand the need for change and be open to it. The anxiety will never go away, but may be reduced, enabling the organization to focus on the future rather than dwelling on the present. Through use of this language, the CEO mandate becomes apparent. Reengineering the enterprise is a form of renewal. The reaction of many will be anxiety and fear; others will be intrigued and energized. Some will hear the opportunity of a lifetime knocking at their door.

So after the overall strategies have been articulated, business models updated, and the organization enrolled, it is now time to convert all the thinking, choices, models, and assumptions into a cogent multiyear plan for execution. Operationalizing it requires a dedicated and focused team, which is discussed next in Section V, “Create and Empower the CDE Task Force.”

V Create and Empower the CDE Task Force

In the prior chapter, the argument was made that the effective CEO focuses on the strategy, culture, and senior leadership. She must enable the organization to change, not by micromanaging the details, but by empowering the organization and holding it accountable. In general terms, operationalizing the transformation requires installing a capable task force to oversee the details of implementation, recognizing that overcoming cultural and structural hurdles will require talented leadership and real perseverance. In a large organization, this task force can be expected to play an important role for 2 to 5 years depending on the degree of transformation required, the size of the organization, and the complexity of the business. This section discusses the key responsibilities of this team and its charter.

Installation of the Overall Champion and Leader of the CDE Task Force

This initiative must have an overall operating champion with impeccable credibility and substantial leadership ability. This must be someone who can inspire the change needed while acting as a trusted agent of the CEO. Potential candidates will be many things, including a strategist, a tactician, a field marshal, and a politician, if they are to be successful. And the choice of this leader is one of the more important that the CEO will make with respect to bringing CDE to life in her organization.

We recommend that a senior leader be chosen and dedicated to this program, potentially someone who is prominent in the succession line to the chief executive position. And as such, this person will be fully capable to appreciate the far-reaching implications of her actions and the importance of her mission, while having a deep understanding of the current organization and the way things are done today. The Champion will report on progress to the CEO and to the Board of Directors as needed and should not be afraid of controversy or change.

Coordination of Strategy, Execution, and Progress Reporting

The CDE task force will take primary responsibility for executing the vision, engaging the whole organization in culture change and change management activities, and measure and report back on progress to the CEO. In large organizations, the task force is a dedicated team that includes extended teams that reach across the business. Positioning is important and the task force must be viewed as an extension of the CEOs office with the entire mandate that entails.

The task force should be afforded significant authority, responsibility, and accountability. Although this initiative is a CEO-level mandate, the task force should manage the program and should only require intervention by the CEO around key strategic decisions and some early operational matters. Early in the process, the CEO may intercede more frequently, reinforcing the goals, expectations, and gravity of the mandate.

The CDE task force should be in constant communication with leadership in targeted areas of the business, requiring each of these areas to identify opportunities, operationalize plans, and to update the task force periodically on progress. The task force will be the air traffic control system for implementing the CDE and depending on the overall plan established by the organization, there may be a few or several departments, divisions, or functions at various stages of execution at any point in time.

Each targeted area of the business must provide a cogent plan that is realistic and aggressive, while balancing risk and long-term gain. In addition, these plans must be reconciled across the organization in time and space. Programs behind schedule or in need of attention will become apparent through this level of tracking. The task force will also have excellent visibility into key wins, emerging best practices, and where talented CDE capable leaders are developing.

As we have said before, the status quo is quite effective at maintaining itself. Experience teaches us that these exercises typically produce incrementalist plans at best in their first iterations. Reasons given will be “we cannot jeopardize the customer experience, can we?” or “we already employ the smartest people in our field!” or “now is not the best time to reorganize.” These reactions should all be expected. They are natural, but what happens next is the most important. You must demand these teams, functions, and divisions to come back, again and again, until plans that comprehend and embrace the change needed are presented. This is an area where outside advisors or dedicated practitioners can play a vital role in challenging and supporting these efforts.

The CDE task force should apply good management oversight in addition to common sense to ensure that the various functions will effectively and efficiently transform the organization to the desired state while managing risk across the entire system. For example, the heavier use of outsourced providers should be balanced to give the organization sufficient power and influence to ensure quality and dependable service levels, particularly for critical functions. Choosing technologies and tools to enable the future state are also examples in which consolidated requirements across the teams and standardizing training and methods could provide substantial benefits.

Identify and Prioritize Internal Opportunities for Reengineering

Not all the opportunities will be identical, and some will clearly drive more upside than others. Look for opportunities to have significant impact in the early years, big hitters, and low-hanging fruit. Leadership already has a good idea where to start. Why are you hiring 1,000 engineers? Should you be building call centers when India has excess capacity at a substantially lower cost base? Can you license the technology rather than buying the company? And by focusing on a few high-impact opportunities for reengineering, the likelihood of success increases as does the magnitude of the gains for the early wins.

Some organizations find that creating new structures are particularly effective when fresh ideas run the risk of being hamstrung by the existing culture or organization and in some cases go so far as to create entirely new companies. This can be a useful tactic, particularly suited in applications such as creating entirely new products or establishing new business lines, although its scalability for broad transformation is limited.

So whether identifying key functions, projects, or divisions, thoughtful selection of initial targets in the early years may prove far superior to tackling every aspect of the change at once. Likelihood of success will be higher, early dividends will be secured, success stories created, and risks minimized. But to be clear, this approach must be part of an overt, committed, comprehensive plan for change. Anything less may run the risk of undermining the transformation.

Cross-Fertilize Opportunities

In this process, the CDE task force should look for every opportunity to use its coordination role to unlock upside for the company and shareholders. One manufacturing division may be developing capacity or capabilities unknown to another. Or R&D agendas could be advanced more efficiently if rationalized and executed through open innovation and partnership channels. In the strategy, planning, and ongoing execution phases of the project, the task force must maintain a deep understanding of the various touch points between efforts as well as overall opportunities to “connect the dots” wherever possible. Any opportunity to leverage learnings, methods, and resources should be exploited. Further, with critical focus, significant and surprising opportunities will be identified for synergy and elimination of waste.

Regular Communications

Regular communications are critical in the tone, intensity, and excitement because they can improve execution efforts and constantly reinforce the central transformational theme across the organization.

You need a well-defined CDE scorecard for the whole company and periodic summary-level progress reports. They should have a fairly wide distribution published regularly on the intranet for access by the entire organization. Further by communicating and archiving best practices, success stories, tips and advice from the gurus, and so on, a new body of learning and methods emerges that will be invaluable. And integrating these communications efforts with broader internal and external corporate communications will further reinforce the message and the resolve to transform the company.

Finally, the CDE task force, while being held accountable by the CEO, must hold the entire organization accountable, not only to execute the CDE agenda, but also to deliver fundamental and durable change. The task force is the sharp point of the spear, and its efforts can make or break the overall initiative. While its authority comes from the CEO commitment whose constant support and visible attention is vital to the success of the transformation, it must own the transformation and provide its own strong leadership.

VI Align and “Ready” the Organization

The CDE requires a significant paradigm shift from that of most organizations today. Along with that shift comes the implication that most parts of the organization will undergo change, some more so than others. The prior section focused on establishing the CDE task force, an effort with a beginning, middle, and end. Now we consider opportunities to align and “ready” the entire organization for the transformation. Some of these activities belong to the CEO, some to the task force, and some to other areas of the organization. We will discuss management systems, reducing barriers to adoption, capabilities, key roles, and other considerations in this section.

Remake the Management Systems

Our management systems define how the organization functions internally and with the rest of the world. These systems include structure and hierarchy, information flow and decision making, and process controls among others.

We must rethink these areas because they both enable and constrain organizational behavior. Want to change the behavior? Consider changing the systems. For example, the US military found that the new realities of warfare required more empowerment and agility in the field after generations of training soldiers to operate in highly structured command and control environments began to fail. It became clear after 2001 that the systems were no longer able to meet the challenges of modern warfare. Consequently, chain of command, training programs, recruitment, and rules of engagement have adapted considerably in support of the military’s mission.

While each corporation’s systems are unique, the basics structures are similar, largely because they are all based on the bureaucratic form (need to minimize transaction costs, etc). We mention two related areas as foundational alterations you should consider for remaking your management systems: functional decoupling and competition.

Most of your functions are tightly coupled. Consider how sales is related to marketing or products relationship with manufacturing. The old form required this linkage to maximize scale economies. In the new world, every business leader should be striving for efficiency and while marketing must “own” the message, sales is paying the bill, literally and figuratively. By adopting an outcome mentality, inside and out, each function will hold its own ecosystem more accountable than in the past, highlighting gaps and challenges, while suffering less the bureaucracy and inefficiency that many organizations have become accustomed. The second, but related, concept is competition. Here we go even further to say that product may call out manufacturing for not being cost effective for example. Controls must be in place, but if manufacturing cannot improve its operations and match external costs standards then there may be a business case for moving contracts outside. The controls must ensure that business objectives are met across the system, but we all know that a substantial share of inside work is inefficient and poorly managed. By redefining functional coupling and introducing competition, accountability, transparency, and efficiency are all brought front and center. And in the process, the organization will begins evolve itself toward the network form and will begin to exercise its new orchestration skillset in the process.

Address Structural Barriers to Adoption

There are many structural barriers to adoption, some of which were discussed in prior chapters. The CDE task force, with timely engagement of the CEO, should be breaking down barriers as they emerge and identifying future roadblocks to adoption.

For example, the legal function is likely entrenched in protecting the organization, staff, and existing assets as it has done for years. Opening up processes, actively and aggressively in-licensing and out-licensing technology, using emerging talent networks, and partnering as a primary strategy are all examples of new behaviors and capabilities that will stress existing practices. HR is traditionally tasked with managing employees. As a consequence, developing robust and reliable talent pools of virtual workers will almost certainly fall outside its base of experience. The same realizations will be made whether looking at brand management, product development practices, financial accounting, and many other areas of the company. The point is that the CDE task force needs to play an aggressive leadership role in identifying roadblocks, efficiencies, and even key strategic decisions that must be made to keep the overall CDE transformation on schedule.

Most of these barriers to adoption will repeat themselves over and over as each company manages its own journey. Therefore, the organization in the early planning stages should proactively reach out to firms who are further along, experienced consultants, and others to identify best practices and templates for change that recognize the complexities and likely roadblocks. The Task Force should work diligently to eliminate the roadblocks and barriers to changes as early as possible in the process.

Developing Critical Skills: Problem Solving

As stated in earlier chapters, critical skills in problem solving are vital and often (usually) represent an underdeveloped skill set in organizations. Leadership must recognize these deficits and compensate carefully to ensure that the Challenges are well designed, that they align with important and strategic goals, and that the results are tangible and measurable. Consider building and adopting a methodology and developing training curriculum. New hires should be screened for critical reasoning skills. Some staff may show particular promise in identifying and formulating problems (Challenges) and could be candidates for shared resource pools to support the broader CDE efforts in the organization.

Engage Innovation, HR, and Business Development Functions Early

As we’ve said, strategy and orchestration are the fundamental areas where real value is created in the network model; accordingly, business functions such as innovation, HR, and business development have particularly important roles to play in support of the transformation. Although every part of the organization will require examination and potentially restructuring, these three areas will be specifically discussed here.

First among these is the innovation function, the lifeblood of many organizations. Encompassed by this term are business innovation, product development, traditional research and development; even marketing, creativity, and inventiveness are necessary ingredients to beating out the competition. Innovation too often measures itself by the number of strategists, researchers, patents, or the number of product development centers under construction. Instead, it should focus on understanding which problems and opportunities matter to the business. The mindset must change from running experiments to developing, finding, and exploiting solutions. Now these organizations will continue to require staff sufficient to manage the business to be sure, but the focus and overall profile may change considerably. So these organizations must build up skills in program management, partner orchestration, problem definition, and vendor relations. It must provide oversight and leadership to what are often complex programs. In some cases, these organizations will become systems integrators.

Innovation leadership may require new management tools, including options analysis and financial modeling. Most dramatically, you must be a portfolio manager and “network” orchestrator, whose only measure of success is enabling the company and its products to dominate its markets to enhance shareholder value.

HR similarly is redefined in this model. As previously discussed, this role is more strategic than ever and must now enable access to talent on a global scale in a world where people and skills are accessed on-demand. HR must be both a thought leader and the agent provocateur in areas ranging from how best to manage variable versus fixed labor costs to how the organization can tap virtual communities, including customers, retirees, and innovation markets. HR is now front and center as the organization identifies opportunities to virtualize its business model to remain competitive.

The last area highlighted is business development, which plays an increasingly core role as an enabler in the network model. Already expert in identifying value creating opportunities between business partners and structuring mutually beneficial engagement models, this function is more vital than ever. The importance of this function is apparent in organizations such as Procter & Gamble, who now places portions of their open innovation programs under powerful new global business development functions to drive efficiency and focus.

And leaders in these areas must now be evangelists and key lieutenants in driving the transformational change as they lead their departments with newly expanded charters.

Assess Compensation and Incentive Systems Top to Bottom

Plan to completely overhaul position descriptions, goals, and compensation design. There must be an unwavering focus on shareholder value and it should drive measurement and compensation systems for all staff at all levels. Most staff cannot tie their execution to dividends and share price directly, not because it is impossible, but because we too often lack the discipline. Even building the basic linkage between individual responsibilities and key stated corporate strategies is shockingly lacking in most organizations. These systems must be realigned to drive the transformation needed.

New goals and targets should be created that track and reward progress against key transformational elements of the agenda. Goals like percent of innovation from the outside, or proportion of variable versus fixed spend, or amount of capital freed up for investment in programs are all good examples of targets that can be established.

This work should begin early and be performed in a coordinated fashion across the organization with the goal of formalizing the objectives and quickly cascading them throughout the enterprise. Identifying opportunities to redefine roles consistent with needs of the organization is part of this work. New skills and capabilities will be needed and many roles, titles, and responsibilities will change across the organization.

Recognition Systems and Behavioral Change

Traditional and nontraditional recognition systems can have a powerful impact on behavior, including performance appraisals, compensation and incentive structures, and special recognition programs such as a President’s Club. Use these tools liberally to encourage adoption.

Again, do not underestimate an organization’s resolve to protect the status quo, a natural reaction to change that is difficult in any organization. Anticipate push back and work to resolve early. Be particularly vigilant in identifying pockets of passive aggression that are difficult to spot but that can have toxic implications for the success of the program. For example, actual research has shown that in some cases, open innovation test projects were selected teams by product teams with a low likelihood of success to increase likelihood of failure in order to generate negative proof points to protect the status quo.

VII Select Enablers and Enroll Partners

This section discusses the role of technology and partners in enabling CDE and ensuring its successful realization. We have discussed commitment, strategy, trials and adoption, and even the leadership needed in support of implementation. However, it is often difficult for organizations to change from within without enablers and partners to assist in the work ahead. Enabling technology, management consultants, trusted partners, and the like improve the odds and help in avoiding unnecessary pitfalls—not unlike the health-minded individual who chooses a gym and a personal trainer to achieve the goals that he could likely accomplish on his own. He knows the right tools can improve the odds and positively impact time to results.

Depending on the needs of the organization, several opportunities may exist to support change through tools and other enablers. A number are discussed next.

Methodology and Training

In this context, methodology refers to having a well-defined and documented approach, complete with best practices, templates, case studies, and training modules. InnoCentive’s Challenge Driven Innovation approach is an example. More general-purpose methodologies also exist in areas that address open innovation, change management, cultural change, and business process outsourcing, to name a few. Assess these methodologies and select one or more for deployment. Typically organizations will train and certify individuals, teams, and areas of their business on its use. There are scale economies here, and the greater the percentage of the organization using the methodology, the greater the benefits that can accrue. Creating a common language alone is valuable, but many of the methodologies provide much more, including management tools, measurement and analytics, best practices, and so on. Choose well and then immerse the company in its use.

Mass adoption of methodologies, technology, and processes require a programmatic approach to facilitate adoption and utilization. In the early stages, the focus should be on key leaders and practitioners who will be involved in early trial activities in addition to resources being set aside within the CDE task force, but ultimately a significant share of the overall staff should have exposure to the key concepts, tools, and so on.

HR and corporate training have roles to play here in addition to resources experienced in change management. The organization may also engage outside training firms, management consultants, and other resources to assist as needed. These programs should be integrated into existing programs, new employee training, internal certifications, and compliance programs both to attain efficiencies and to reinforce that the content is now part of the core learnings for effective employees. Large organizations may consider their own CDE University where content can be stylized based upon level and domains.

Sustaining the focus and competencies is critical. Depending on the roles, staff should be encouraged to keep its knowledge bases current. These can be done through refresher courses and reinforced by promoting communities of practice. Organizing in a symposia format can be particularly engaging for mid- and senior-level leaders and managers. For example, senior manufacturing leadership can be trained in examples relevant to their domains while also creating their own informal communities of practice. Coupled with use of intranet sites, discussion boards, and internal working papers, the knowledge, language, and capability building can be easily sustained.

Open Innovation and Other Partnering Opportunities

CDE is built around fundamental principles, and one of those is that business can sustain themselves only through agility, innovation, and financial flexibility. Their costs of innovation continue to increase, often faster than the revenue line, while the competition is increasingly nimble. Increasingly costly and inefficient innovation organizations represent a particularly intriguing reengineering opportunity through open innovation.

Open innovation companies such as InnoCentive already have tools, methodologies, and even global innovation networks available on demand for companies. Management consultants such as Accenture and Monitor Group have dedicated innovation practices with considerable experience in organizational design, change management, and even business process reengineering. Partners such as these can significantly “de-risk” the value proposition and costs for businesses. You need to evaluate the landscape, identifying vendors and partners with potential to enable the CDE journey, and forging the partnering relationships to manage and sustain the change.

Timelines and the Institutionalization of the CDE

Remember the term e-business? Used mostly in the 1990s, it had particular usefulness as businesses tried to think through how technology and global networks would impact them. Interestingly, almost with a whimper, the term fell out of use. It was not that the principles were withdrawn from the marketplace or that they were discredited—quite the contrary. The concepts became pervasive, the toolsets matured, and success stories entered the history books. In other words: e-business became just business.

This is the institutionalization needed by corporations as they engage the future. With their business models virtualized, they will be assembling and disassembling assets to capitalize on market opportunities, building global ecosystems to extend their reach and amplify their resources, and engaging millions to drive breakthrough innovation to get that next generation network router to market before the competition. At some point, the CDE must become simply how you do business.

We believe that CEOs and Boards of Directors should assume 5 to 10 years are necessary for the transformation to fully take hold, although efforts may be generating dividends to the top and bottom line much sooner. Institutionalization means that the organization isn’t applying these principles because they’ve made commitments to the CDE task force or to finance—it is because they are practitioners and disciples of the new management science. In 5 to 10 years, cultures, people, and organizations can change dramatically.

Use the Playbook, Adapt as Needed, and Play to Win

This playbook is designed to structure your thinking, organize your actions, and focus your efforts. It may also provide other kinds of benefits such as a basic language and project management framework for charting the approach. It contains all the basic organizing elements to begin and substantially manage the journey to becoming the CDE. Depending on the CEO and his leadership style and the company and its culture, the plays can be adapted to suit various approaches.

For example, consider these three basic approaches:

• Transformation: The CEO announces and launches an effort to transform the company; the future (and the present) demands it.

• Evolutionary, not Revolutionary, Change: The CEO makes “Open” a core value and challenges the organization to embrace its use.

• Strategic Capability Building: The CEO instructs the organization to “implement” CDE much like Six Sigma or Total Quality Management.

There are many levels of commitment and approach. The plays support each with simple variation of sequence, timing, and emphasis. Further, you can freely adapt the CDE Playbook to support implementation in different contexts. By making logical substitutions and applying common sense, the playbook will apply for divisions, departments, small business, government, and even the Not-for-Profit (NFP) sector.

Transformational change on any scale is difficult. Expect setbacks along the way, but seek every opportunity to learn through the process. Don’t be afraid to experiment and revise the plans based upon the learnings. Invest in practices that are working and reset those that are not. Add to the playbook as institutional learnings and best practices emerge. But at all times, persevere and never withdraw from the commitment to change.

Finally, the CDE Playbook alone cannot transform the organization. A thoughtful approach is necessary but not sufficient to ensure success. Again quoting the famous football legend:

“Coaches who can outline plays on a blackboard are a dime a dozen. The ones who win get inside their players and motivate.”

—Vince Lombardi

Lombardi was not advising coaches to throw away the playbooks. Instead he was talking about the real vision and leadership required to make magic happen. That is the topic of the last chapter.

Case Study: How the Prize4Life Foundation Is Crowdsourcing ALS Research

At age 29, Avi Kremer was diagnosed with ALS (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease). “What do I do now?” he asked his doctor. “Prepare a will,” the doctor replied.2

ALS is a rare disease, striking 2 out of 100,000 people, usually between the ages of 40–70. Not only is there no known cure for ALS, but there is only one FDA-approved treatment that is only modestly effective Most patients die within 2–5 years of diagnosis. On top of that, accurate diagnosis is often elusive and difficult. Avi himself was misdiagnosed twice by doctors who attributed his symptoms of uncontrollable hand cramps and inability to lift the same weights as before to “stress” and pronounced him “in great health,” before he was correctly diagnosed.3

Although its cause is unknown, ALS’ symptoms are torturously similar: a progressive loss of all motor control, beginning with the hands, feet, speech centers, and eventually even to control of breathing itself. All the while, however, the mind typically remains perfectly intact and sharp, trapped inside the totally paralyzed body.

As Avi researched the disease and his options, he began to realize that the doctor’s advice to “make a will” was truly one of the few concrete steps open to him as an ALS sufferer. There were no medications to delay or ameliorate the symptoms except one drug, which prolonged life at most 2–3 months at a cost prohibitive to many payers.

But Avi, a former Captain in the Israeli army who had just been admitted to Harvard Business School two months before his diagnosis, decided to do more than just make a will. He decided to apply all his training, brainpower, and resources available to him at Harvard to make the biggest impact he could on the development of treatments and possibly even a cure for ALS. His first tack: to figure out why more wasn’t being done in ALS drug development? The answers here proved easy to find. First, ALS was a rare disease—only a total of 640,000 people worldwide have it. Second, those patients who do have ALS die quickly, meaning it is difficult to recruit enough patients to run large clinical trials. Third, because the disease’s cause was not known and there were no biomarkers to evaluate its progression, the main way to tell if a given therapy had value was to see whether patients lived or died, leading to long clinical trials. The upshot of these three factors was that while the market was attractive, ALS clinical trials were difficult, expensive, and risky. So how could this be changed? As Avi examined his options for the few years of life left to him, he saw he could:

• raise money for ALS research, as Michael J. Fox has done for Parkinson’s Disease.

• launch a drug company that would pursue a promising therapy.

• offer a prize, à la the Ansari X PRIZE, to the first person or team to make a step toward a cure.

The idea for the third option came from a class that Avi attended, where Jill Panetta, then Chief Scientific Officer at InnoCentive, had spoken about the role of prizes in spurring research and solutions in a given area. For example, the Ansari X PRIZE had given birth to the commercial space industry by offering a $10 million prize to the first team from private industry to devise a spacecraft capable of carrying three people 100 kilometers above the earth twice within two weeks.

Avi wanted to do something similar for ALS, and he formed the Prize4Life Foundation to do just that. Prize4Life would award $1 million to the first person or team that identified and validated an ALS biomarker (a way to track disease progression) that could be used to de-risk ALS clinical trials.

The prize approach had several advantages. First, it would bring attention and a laser-like focus to the specific need for a clinically relevant ALS biomarker (a critical missing tool in the drug development landscape). Second, the prize presented a novel way to get funding for the disease—donors would only pay if the prize were awarded. This appealed to an entrepreneurial class of donors, attracting new sources of money to the field. Third, the prize would be global, meaning that anyone from anywhere in the world could compete for it. This unique aspect of the prize model, to incentivize individuals and teams from diverse disciplines to consider how to translate their expertise to the challenge of ALS, supported InnoCentive’s previous experience that with seemingly intractable problems, solutions often come from someone outside the field.. Finally, the publicity around the prize—the largest that Prize4Life partner InnoCentive had ever offered at the time—would help generate increased awareness for the disease.

Prize4Life put a two-year end date on its prize award—an extremely aggressive timeline. “It can often take a researcher two years just to get an NIH grant funded,” said Melanie Leitner, Ph.D., Chief Scientific Officer at Prize4Life. Nonetheless, Prize4Life’s Scientific Advisory Board believed that despite the very high bar, there was a reasonable likelihood that it could be met in two years. “Given the urgency of the need it, was worth taking the risk,” Leitner said.

More than 50 teams from 18 countries competed for the prize, and 12 submissions were received by the deadline. “We have often said that one of the best things the incentive prize model can do is attract a wide variety of people to think about a particular problem in new and different ways, and the submissions we received demonstrate that, as a complement to front-end funding and support, the prize model can truly help accelerate the discovery of answers to very focused problems,” Leitner said.

At the end of two years, no team had met all the criteria for the prize, but two were very close: a dermatologist with no previous ALS research experience, and a long-time ALS researcher who decided to narrow his focus specifically to the ALS biomarker challenge. Given how close the two had come to solving the challenge, Prize4Life awarded both solvers $50,000 Progress Prizes to reward their efforts to date and reissued the prize for another two years.

“If this Challenge hadn’t been issued, there is little chance I would have even pursued this idea,” said the dermatologist, Dr. Harvey Arbesman. “This approach has been an effective way to get people across disciplines, from all around the world, to think about ALS and has been an effective way to tap new perspectives from outside the field. I am greatly encouraged by the results of our research thus far and am hopeful it will have a positive impact on ALS treatment in the future.”

Seward Rutkove, the other Progress Prize winner, said, “When I became aware of the Challenge, I had already been pursuing this very research in neurological diseases for several years. In a way it was a lucky coincidence, but participating in the Challenge helped to refine my thinking. It led me to apply my technology research specifically to ALS focusing on both the animal studies and device development. In our case, participation has effectively sped the development of a handheld device to sensitively measure disease progression.”

A year later, Rutkove submitted a revised proposal based on his additional research and work. Prize4Life’s independent Scientific Advisory Board unanimously agreed that Rutkove had met all the criteria of the challenge. He had identified a clinically relevant biomarker of disease progression and was awarded $1 million.

Although $1 million is a big prize, it is a very small price to pay for the discovery, and it highlights the productivity of the prize approach. “The Alzheimer’s Disease field has recently seen major progress in the identification of useful clinical biomarkers, but this has followed an enormous financial investment (over $100 million) in the form of the ADNI consortium, which was initiated in 2004,” Leitner said. “The Parkinson’s Disease field has also just initiated a $40+ million effort to identify new Parkinson’s Disease biomarkers.”

Going forward, Prize4Life will continue offering specific prizes for specific solutions. “We believe in the model. The right prize for the right question can lead to major breakthroughs,” Leitner said.

Avi added, “Prizes are risk-free; you only pay for what you want.”

The bottom line? In a relatively short time and at much lower cost than traditional research, Prize4Life is proving that open innovation and incentive prizes can be a very powerful toolset to accelerate breakthroughs in even the most complex areas of R&D.