Chapter 1. Introducing the .NET Framework 4.5

As a Visual Basic 2012 developer, you need to understand the concepts and technology that empower your applications: the Microsoft .NET Framework. The .NET Framework (also simply known as .NET) is the technology that provides the infrastructure for building the next generation’s applications that you will create for the Desktop, the Web, the Cloud, and over the most recent operating systems such as Windows 8. Although covering every aspect of the .NET Framework is not possible, in this chapter you learn the basis of the .NET Framework architecture, why it is not just a platform, and notions about the Base Class Library and tools. The chapter also introduces important concepts and terminology that will be of common use throughout the rest of the book.

Supported Operating Systems

Visual Studio 2012 and the .NET Framework 4.5 run on Windows 8, Windows 7, and Windows Vista with Service Pack 2. Applications built with the .NET Framework 4.5 cannot run on Windows Vista without SP 2 and, most importantly, on Windows XP.

What Is the .NET Framework?

Microsoft .NET Framework is a complex technology that provides the infrastructure for building, running, and managing next-generation applications. In a layered representation, the .NET Framework is a layer positioned between the Microsoft Windows operating system and your applications. .NET is a platform but also is defined as a technology because it is composed of several parts such as libraries, executable tools, relationships, and integrates with the operating system. Microsoft Visual Studio 2012 relies on the new version of the .NET Framework 4.5. Visual Basic 2012, C# 5.0, and F# 2012 are .NET languages that rely on and can build applications for the .NET Framework 4.5. The new version of this technology introduces important new features that will be described later. In this chapter you get an overview of the most important features of the .NET Framework so that you will know how applications built with Visual Basic 2012 can run and how they can be built.

Where Is the .NET Framework?

When you install Microsoft Visual Studio 2012, the setup process installs the .NET Framework 4.5. .NET is installed to a folder named %windir%Microsoft.NETFramework4.0.30319 (see the paragraph titled “Differences Between .NET 4.0 and 4.5” later in this chapter for details about versioning). If you open this folder with Windows Explorer, you see a lot of subfolders, libraries, and executable tools. Most of the DLL libraries constitute the Base Class Library, whereas most of the executable tools are invoked by Visual Studio 2012 to perform different kinds of tasks, even if they can also be invoked from the command line. Later in this chapter we describe the Base Class Library and provide an overview of the tools; for now you need to notice the presence of a file named vbc.exe, which is the Visual Basic Compiler and a command-line tool. In most cases you do not need to manually invoke the Visual Basic Compiler because you will build your Visual Basic applications writing code inside Visual Studio 2012, and the IDE (Integrated Development Environment) invokes the compiler for you. But it is worth mentioning that you could create the most complex application using Windows’ Notepad and then run Vbc. Finally, it is also worth mentioning that users can get the .NET Framework 4.5 from Microsoft for free. This means that the Visual Basic Compiler is also provided free with .NET, and this is the philosophy that has characterized the .NET development since the first version was released in 2002.

The .NET Framework Architecture

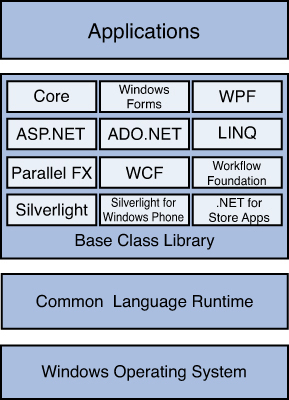

To better understand the structure of the .NET Framework, think about it as a layered architecture. Figure 1.1 shows a high-level representation of the .NET Framework 4.5 architecture.

Figure 1.1. The .NET Framework 4.5 layered architecture.

The first level of the representation is the operating system; the .NET layer is located between the system and applications. The second level is the Common Language Runtime (CLR), which provides the part of the .NET Framework doing the most work. We discuss the CLR later in this chapter. The next level is the Base Class Library (BCL), which provides all .NET objects that can be used both in your code and by Visual Basic when creating applications. The BCL also provides the infrastructure of several .NET technologies that you use in building applications, such as WPF, Windows Forms, ASP.NET, WCF, and so on. The last level is represented by applications that rely on the previous layers.

Although the various frameworks exposed by the BCL are discussed later in the book, in this chapter, now you get an overview of the library and can understand how it works and how you can use it.

Differences Between .NET 4.0 and .NET 4.5

The .NET Framework 4.5 is basically a replacement of the .NET Framework 4.0. In fact, they both have the same version number. In particular, the version number of an assembly of .NET 4.0 is 4.0.30319.261, whereas the version number of an assembly of .NET 4.5 is 4.0.30319.17626. From a practical perspective, you can consider .NET 4.5 as an update for 4.0. If you try to install the .NET Framework 4.5 on a machine where .NET 4.0 is already installed, this will be simply overwritten in the same directory and new assemblies and tools, specific to the new version, will be added. As a consequence, applications that you created with Visual Studio 2010 (including the Express editions) will still run with no problems, but will not take advantage the new version’s features. As another consequence, migrating a project from Visual Studio 2010 to Visual Studio 2012 should be painless. Of course version 4.5 provides a lot of changes and improvements at the architecture level, so installing the new version will update existing assemblies of the .NET 4.0 (if any) with more recent files but will also update the architectural infrastructure of the Common Language Runtime. If you’re a developer, you should be comfortable searching for .NET files and tools in the same location as the previous version; this will be good for both Visual Studio 2010 and 2012, avoiding confusion and saving some time.

The Common Language Runtime

As its name implies, the Common Language Runtime provides an infrastructure that is common to all .NET languages. This infrastructure is responsible for taking control of the application’s execution and manages tasks such as memory management, access to system resources, security services, and so on. This kind of common infrastructure bridges the gap that exists between different Win32 programming languages because all .NET languages have the same possibilities. Moreover, the Common Language Runtime enables applications to run inside a managed environment. The word managed is fundamental in the .NET development, as explained in the next paragraph.

Writing Managed Code

When talking about Visual Basic 2012 development and, more generally, about .NET development, you often hear about writing managed code. Before the first version of .NET (or still with non-.NET development environments), the developer was the only responsible person for interacting with system resources and the operating system. For example, taking care of accessing parts of the operating system and managing memory allocation for objects were tasks that the developer had to consider. In other words, the applications could interact directly with the system, but as you can easily understand, this approach has some big limitations both because of security issues and because damages could be dangerous. The .NET Framework provides instead a managed environment. This means that the application communicates with the .NET Framework instead of with the operating system, and the .NET runtime is responsible for managing the application execution, including memory management, resources management, and access to system resources. For example, the Common Language Runtime could prevent an application from accessing particular system resources if it is not considered full-trusted according to the Security Zones of .NET.

Speaking with the System

You can still interact directly with the operating system, for example invoking Windows APIs (also known as Platform Invoke or P/Invoke for short). This technique is known as writing unmanaged code that should be used only when strictly required. This topic is discussed in Chapter 48, “Platform Invokes and Interoperability with the COM Architecture.”

Writing managed code and the existence of the Common Language Runtime also affect how applications are produced by compilers.

.NET Assemblies

In classic Win32 development environments, such as Visual Basic 6 or Visual C++, your source code is parsed by compilers that produce binary executable files that can be immediately interpreted and run by the operating system. This affects both standalone applications and dynamic/type libraries. Actually Win32 applications, built with Visual Basic 6 and C++, used a runtime, but if you had applications developed with different programming languages, you also had to install the appropriate runtimes. In.NET development things are quite different. Whatever .NET language you create applications with, compilers generate an assembly, which is a file containing .NET executable code and is composed essentially by two kinds of elements: CIL code and metadata. CIL (formerly known as MSIL) stands for Common Intermediate Language and is a high-level assembly programming language that is also object-oriented, providing a set of instructions that are CPU-independent (rather than building executables that implement CPU-dependent sets of instructions). CIL is a common language in the sense that the same programming tasks written with different .NET languages produce the same IL code. Metadata is instead a set of information related to the types implemented in the code. Such information can contain signatures, functions and procedures, members in types, and members in externally referenced types. Basically metadata’s purpose is describing the code to the .NET Framework. Obviously, although an assembly can have an .exe extension, due to the described structure, it cannot be directly executed by the operating system. In fact, when you run a .NET application the operating system can recognize it as a .NET assembly (because between .NET and Windows there is a strict cooperation) and invoke the Just-In-Time compiler.

The Execution Process and the Just-In-Time Compiler

.NET compilers produce assemblies that store IL code and metadata. When you launch an assembly for execution, the .NET Framework packages all the information and translates it into an executable that the operating system can understand and run. This task is the responsibility of the Just-In-Time (JIT) compiler. JIT compiles code on-the-fly just before its execution and keeps the compiled code ready for execution. It acts at the method level. This means that it first searches for the application’s entry point (typically the Sub Main) and then compiles other procedures or functions (methods in .NET terminology) referenced and invoked by the entry point and so on, just before the code is executed. If you have some code defined inside external assemblies, just before the method is executed the JIT compiler loads the assembly in memory and then compiles the code. Of course, loading an external assembly in memory could require some time and affect performance, but it can be a good idea to place seldom-used methods inside external assemblies, the same way as it could be a good idea to place seldom-used code inside separated methods. The .NET Framework 4.5 introduces important improvements to performance by enabling the so-called Parallel JIT Compilation. This improvement takes advantage of multicore processor architectures and runs the JIT process on a background thread that works on a separate processor core. In this way, the JIT compilation is faster and, therefore, the application execution is also faster.

The Base Class Library

The .NET Framework Base Class Library (BCL) provides thousands of reusable types that you can use in your code and that cover all the .NET technologies, such as Windows Presentation Foundation, ASP.NET, LINQ, and so on. Types defined in the Base Class Library enable developers to do millions of things without the need of calling unmanaged code and Windows APIs and, often, without recurring to external components. A type is something that states what an object must represent. For example, String and Integer are types, and you might have a variable of type String (that is, a text message) or a variable of type Integer (a number). Saying Type is not the same as saying Class. In fact, types can be of two kinds: reference types and value types. This topic is the specific subject of Chapter 4, “Data Types and Expressions”—a class is just a reference type. Types in the BCL are organized within namespaces, which act like a kind of types’ containers, and their name is strictly related to the technology they refer to. For example, the System.Windows.Controls namespace implements types for drawing controls in Windows Presentation Foundation applications, whereas System.Web implements types for working with web applications, and so on. You will get a more detailed introduction to namespaces in Chapter 3, “The Anatomy of a Visual Basic Project,” and Chapter 9, “Organizing Types Within Namespaces.” Basically each namespace name beginning with System is part of the BCL. There are also some namespaces whose names begin with Microsoft that are still part of the BCL. These namespaces are typically used by the Visual Studio development environment and by the Visual Basic compiler, although you can also use them in your code in some particular scenarios (such as code generation).

The BCL is composed of several assemblies. One of the most important is MsCorlib.dll (Microsoft Core Library) that is part of the .NET Framework and that will always be required in your projects. Other assemblies can often be related to specific technologies; for example, the System.ServiceModel.dll assembly integrates the BCL with the Windows Communication Foundation main infrastructure. Also, some namespaces don’t provide the infrastructure for other technologies and are used only in particular scenarios; therefore, they are defined in assemblies external from MsCorlib (Microsoft Core Library). All these assemblies and namespaces will be described in the appropriate chapters.

Programming Languages Included in .NET 4.5

Microsoft offers several programming languages for the .NET Framework 4.5. With Visual Studio 2012, you can develop applications with the following integrated programming languages:

• Visual Basic 2012

• Visual C# 5.0

• Visual F# 2012

• Visual C++ 2012

You can also integrate native languages with Microsoft implementations of the Python and Ruby dynamic languages, respectively known as IronPython and IronRuby.

Where Do I Find IronPython and IronRuby?

IronPython and IronRuby are currently under development by Microsoft and are available as open source projects from the CodePlex community. You can download IronPython from http://ironpython.codeplex.com. You can find IronRuby at http://ironruby.codeplex.com.

There are also several third-party implementations of famous programming languages for .NET, such as Fortran, Forth, or Pascal, but discussing them is neither a purpose of this chapter nor of this book. It’s instead important to know that all these languages can take advantage of the .NET Framework base class library and infrastructure the same as VB and C#. This is possible because of the Common Language Runtime that offers a common infrastructure for all .NET programming languages.

Additional Tools Shipping with the .NET Framework

The .NET Framework also provides several command-line tools needed when creating applications. Among the tools are the compilers for the .NET languages, such as Vbc.exe (Visual Basic compiler), Csc.exe (Visual C# compiler), and MSBuild.exe (the build engine for Visual Studio). All these tools are stored in the C:WindowsMicrosoft.NETFrameworkv4.0.30319 folder. In most scenarios you will not need to manually invoke the .NET Framework tools because you will work with the Microsoft Visual Studio 2012 IDE, which is responsible for invoking the appropriate tools when needed. Instead of listing all the tools now, because we have not talked about some topics yet, information on the .NET tools invoked by Visual Studio is provided when discussing a particular topic that involves the specific tools.

Windows Software Development Kit

When you install Visual Studio 2012, with the .NET Framework and the development environment, the setup process will also install the Windows SDK on your machine. This software development kit provides additional tools and libraries useful for developing applications for the .NET Framework. Microsoft released the Windows SDK that provides tools for building both managed and unmanaged applications. The Windows SDK is installed into the C:Program Files (x86)Microsoft SDKsWindowsv8.0A folder for 32-bit systems or into the C:Program FilesMicrosoft SDKsWindowsv8.0A folder for 64-bit systems. It includes several additional tools also used by Microsoft Visual Studio for tasks different from building assemblies, such as deployment and code analysis, or for generating proxy classes for Windows Communication Foundation projects. Also in this case you will not typically need to invoke these tools manually because Visual Studio will do the work for you. You can find information on the Windows SDK’s tools in the appropriate chapters.

What’s New in .NET Framework 4.5

Assuming you have some knowledge of .NET Framework 4.0 and previous versions, following are new additions introduced by .NET 4.5 for your convenience:

• .NET for Windows 8 Store Apps, a subset of the Framework that developers can use in conjunction with the Windows Runtime to build Windows 8 apps for Windows 8.

• Portable Class Libraries, which allow writing reusable code across multiple platforms like desktop, Silverlight, Windows Phone, and Xbox. They are discussed further in Chapter 17, “Creating Objects: Visual Tools and Portable Libraries.”

• Support for HTML5, unobtrusive JavaScript, asynchronous HTTP requests, modules, and handlers in ASP.NET.

• Asynchronous input/output (I/O) operations against files (see Chapter 18, “Manipulating Files and Streams” and Chapter 44, “Asynchronous Programming”).

• Support for ZIP archives (see Chapter 18).

• Architectural improvements that include support for arrays larger than 2 GB in 64-bit applications, better performance in the Garbage Collection process, faster application startup with background JIT, and better performance when retrieving resources.

• A new programming model for HTTP applications with the new System.Net.Http and System.Net.Http.Headers namespaces.

• Support for generic types, multiple scopes, and support for naming conventions in the Managed Extensibility Framework.

Additional new features and updates target specific technologies; these are discussed in the appropriate chapters.

How .NET Meets Windows 8 and the Windows Runtime

As you might know, Windows 8 is the new operating system from Microsoft that also provides the so-called Windows 8 Store Apps that you can build with Visual Studio 2012 and the .NET languages (in addition to HTML 5/JavaScript). Windows 8 Store Apps rely on a special framework called Windows Runtime (WinRT). WinRT is a framework based on the COM architecture and on unmanaged resources, and the possibility of building Windows 8 Store Apps for .NET developers is due to the presence of a subset of the .NET Framework, which is specific for WinRT and that wraps WinRT’s objects into a managed fashion. This explanation is important to make you understand the focus of this book. This book is language-oriented and focuses on Visual Basic 2012 with the .NET Framework 4.5; most of the language-related concepts explained up to Chapter 20, “Advanced Language Features,” (with the exclusion of the My namespace) will be also valid for Windows 8 development and WinRT, but the .NET Framework and WinRT are two completely different platforms exposing different libraries and types. Therefore, concepts explained about desktop and web development or strictly related to the .NET Framework will not also be valid for the Windows Runtime. Just to provide an example, in both .NET and WinRT (with the layer of the .NET subset) you use the System.IO namespace to manipulate files and directories, but the way you do it is different because the same namespace exposes different classes according to the runtime platform. This explanation can be disregarded if you plan to build only classic desktop or web apps for Windows 8 with the .NET Framework, as well as for Windows 7, Windows Vista with Service Pack 2, Windows Server 2008, and Windows Server 2012.

Summary

Understanding the .NET Framework is of primary importance in developing applications with Visual Basic 2012 because you will build applications for the .NET Framework. This chapter presented a high-level overview of the .NET Framework 4.5 and key concepts such as the Common Language Runtime and the Base Class Library. It also explained how an application is compiled and executed. You even got an overview of the most important command-line tools and the .NET languages.