After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

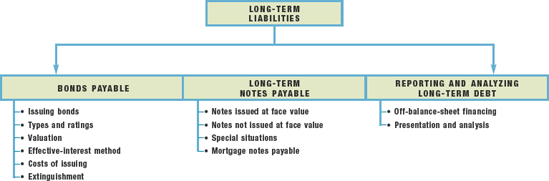

Long-term debt consists of probable future sacrifices of economic benefits arising from present obligations that are not payable within a year or the operating cycle of the company, whichever is longer. Bonds payable, long-term notes payable, mortgages payable, pension liabilities, and lease liabilities are examples of long-term liabilities.

A corporation, per its bylaws, usually requires approval by the board of directors and the stockholders before bonds or notes can be issued. The same holds true for other types of long-term debt arrangements.

Generally, long-term debt has various covenants or restrictions that protect both lenders and borrowers. The indenture or agreement often includes the amounts authorized to be issued, interest rate, due date(s), call provisions, property pledged as security, sinking fund requirements, working capital and dividend restrictions, and limitations concerning the assumption of additional debt. Companies should describe these features in the body of the financial statements or the notes if important for a complete understanding of the financial position and the results of operations.

Although it would seem that these covenants provide adequate protection to the long-term debtholder, many bondholders suffer considerable losses when companies add more debt to the capital structure. Consider what can happen to bondholders in leveraged buyouts (LBOs), which are usually led by management. In an LBO of RJR Nabisco, for example, solidly rated 9⅜ percent bonds due in 2016 plunged 20 percent in value when management announced the leveraged buyout. Such a loss in value occurs because the additional debt added to the capital structure increases the likelihood of default. Although covenants protect bondholders, they can still suffer losses when debt levels get too high.

A bond arises from a contract known as a bond indenture. A bond represents a promise to pay: (1) a sum of money at a designated maturity date, plus (2) periodic interest at a specified rate on the maturity amount (face value). Individual bonds are evidenced by a paper certificate and typically have a $1,000 face value. Companies usually make bond interest payments semiannually, although the interest rate is generally expressed as an annual rate. The main purpose of bonds is to borrow for the long term when the amount of capital needed is too large for one lender to supply. By issuing bonds in $100, $1,000, or $10,000 denominations, a company can divide a large amount of long-term indebtedness into many small investing units, thus enabling more than one lender to participate in the loan.

A company may sell an entire bond issue to an investment bank which acts as a selling agent in the process of marketing the bonds. In such arrangements, investment banks may either underwrite the entire issue by guaranteeing a certain sum to the company, thus taking the risk of selling the bonds for whatever price they can get (firm underwriting). Or they may sell the bond issue for a commission on the proceeds of the sale (best-efforts underwriting). Alternatively, the issuing company may sell the bonds directly to a large institution, financial or otherwise, without the aid of an underwriter (private placement).

Presented on the next page, we define some of the more common types of bonds found in practice.

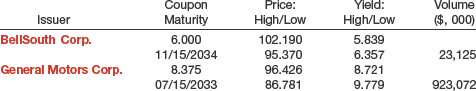

How do investors monitor their bond investments? One way is to review the bond listings found in the newspaper or online. Corporate bond listings show the coupon (interest) rate, maturity date, and last price. However, because corporate bonds are more actively held by large institutional investors, the listings also indicate the current yield and the volume traded. Corporate bond listings would look like those below.

The companies issuing the bonds are listed in the first column, in this case, a telecommunications company, BellSouth Corp., and the automaker General Motors Corp. Immediately after the names is a column with the interest rate paid by the bond as a percentage of its par value, with its maturity date below. The BellSouth bonds, for example, pay 6 percent and mature on November 15, 2034. The General Motors bonds pay 8.375 percent, quite a bit more.

The BellSouth bonds have a current yield of 6.3 percent based on the closing low price of 95.370 per $1,000. The high/low prices are based on trading in a five-day period, in which the volume traded on the exchange amounted to $23,125 million. The General Motors bonds, at the high price of 96.426, yield 8.721 percent. The GM bonds had volume of nearly $1 billion dollars.

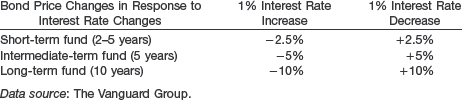

Also, as indicated in the chapter, interest rates and the bond's term to maturity have a real effect on bond prices. For example, an increase in interest rates will lead to a decline in bond values. Similarly, a decrease in interest rates will lead to a rise in bond values. The data reported below, based on three different bond funds, demonstrate these relationships between interest rate changes and bond values.

Another factor that affects bond prices is the call feature, which decreases the value of the bond. Investors must be rewarded for the risk that the issuer will call the bond if interest rates decline, which would force the investor to reinvest at lower rates.

Source: The Bond Market Association (www.investinginbonds.com) (accessed March 2007).

The issuance and marketing of bonds to the public does not happen overnight. It usually takes weeks or even months. First, the issuing company must arrange for underwriters that will help market and sell the bonds. Then it must obtain the Securities and Exchange Commission's approval of the bond issue, undergo audits, and issue a prospectus (a document which describes the features of the bond and related financial information). Finally, the company must generally have the bond certificates printed. Frequently the issuing company establishes the terms of a bond indenture well in advance of the sale of the bonds. Between the time the company sets these terms and the time it issues the bonds, the market conditions and the financial position of the issuing corporation may change significantly. Such changes affect the marketability of the bonds and thus their selling price.

The selling price of a bond issue is set by the supply and demand of buyers and sellers, relative risk, market conditions, and the state of the economy. The investment community values a bond at the present value of its expected future cash flows, which consist of (1) interest and (2) principal. The rate used to compute the present value of these cash flows is the interest rate that provides an acceptable return on an investment commensurate with the issuer's risk characteristics.

The interest rate written in the terms of the bond indenture (and often printed on the bond certificate) is known as the stated, coupon, or nominal rate. The issuer of the bonds sets this rate. The stated rate is expressed as a percentage of the face value of the bonds (also called the par value, principal amount, or maturity value).

If the rate employed by the investment community (buyers) differs from the stated rate, the present value of the bonds computed by the buyers (and the current purchase price) will differ from the face value of the bonds. The difference between the face value and the present value of the bonds determines the actual price that buyers pay for the bonds. This difference is either a discount or premium.[206]

If the bonds sell for less than face value, they sell at a discount.

If the bonds sell for more than face value, they sell at a premium.

The rate of interest actually earned by the bondholders is called the effective yield or market rate. If bonds sell at a discount, the effective yield exceeds the stated rate. Conversely, if bonds sell at a premium, the effective yield is lower than the stated rate. Several variables affect the bond's price while it is outstanding, most notably the market rate of interest. There is an inverse relationship between the market interest rate and the price of the bond.

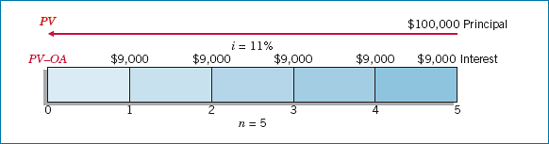

Here we consider an example to illustrate the computation of the present value of a bond issue. Assume that ServiceMaster issues $100,000 in bonds, due in five years with 9 percent interest payable annually at year-end. At the time of issue, the market rate for such bonds is 11 percent. The time diagram in Illustration 14-1 depicts both the interest and the principal cash flows.

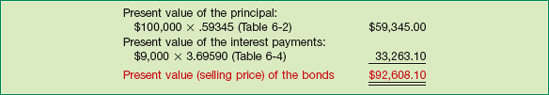

The actual principal and interest cash flows are discounted at an 11 percent rate for five periods as shown in Illustration 14-2.

By paying $92,608.10 at the date of issue, investors realize an effective rate or yield of 11 percent over the five-year term of the bonds. These bonds would sell at a discount of $7,391.90 ($100,000 − $92,608.10). The price at which the bonds sell is typically stated as a percentage of the face or par value of the bonds. For example, the ServiceMaster bonds sold for 92.6 (92.6% of par). If ServiceMaster had received $102,000, then the bonds sold for 102 (102% of par).

When bonds sell at less than face value, it means that investors demand a rate of interest higher than the stated rate. Usually this occurs because the investors can earn a greater rate on alternative investments of equal risk. They cannot change the stated rate, so they refuse to pay face value for the bonds. Thus, by changing the amount invested, they alter the effective rate of return. The investors receive interest at the stated rate computed on the face value, but they actually earn at an effective rate that exceeds the stated rate because they paid less than face value for the bonds. (Later in the chapter, in Illustrations 14-6 and 14-7, we show an illustration for a bond that sells at a premium.)

Two major publication companies, Moody's Investors Service and Standard & Poor's Corporation, issue quality ratings on every public debt issue. The following table summarizes the ratings issued by Standard & Poor's, along with historical default rates on bonds with different ratings. As expected, bonds receiving the highest quality rating of AAA have the lowest historical default rates. Bonds rated below BBB, which are considered below investment grade ("junk bonds"), experience default rates ranging from 20 to 50 percent.

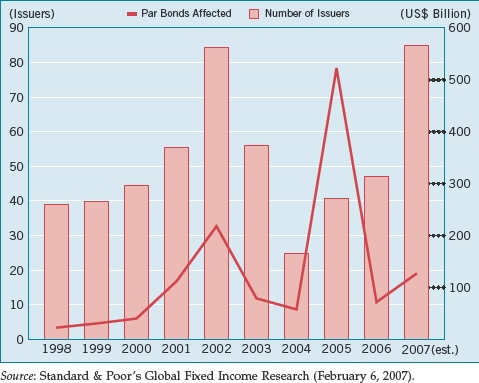

Debt ratings reflect credit quality. The market closely monitors these ratings when determining the required yield and pricing of bonds at issuance and in periods after issuance, especially if a bond's rating is upgraded or downgraded. Data on recent downgrades suggest that the number of "fallen angels" (downgraded debt) is on the rise.

Source: Standard & Poor's Global Fixed Income Research (February 6, 2007).

As recently as 1999, the number and amount of upgrades exceeded downgrades. However, following a decline in 2003, the number of fallen angels increased from 2004–2006, and 2007 is estimated to come in at record levels. It is not surprising, then, that bond investors and companies who issue bonds keep a close watch on debt ratings—both when bonds are issued and while the bonds are outstanding.

Source: A. Borrus, M. McNamee, and H. Timmons, "The Credit Raters: How They Work and How They Might Work Better," Business Week (April 8, 2002), pp. 38–40; Standard and Poors, Global Fixed Income Research, "Fallen Angel Activity" (February 6, 2007); and S. Scholtes, "Bondholders Seek Stability," Financial Times (December 19, 2007), p. 38.

When a company issues bonds on an interest payment date at par (face value), it accrues no interest. No premium or discount exists. The company simply records the cash proceeds and the face value of the bonds. To illustrate, if Buchanan Company issues at par 10-year term bonds with a par value of $800,000, dated January 1, 2010, and bearing interest at an annual rate of 10 percent payable semiannually on January 1 and July 1, it records the following entry:

Buchanan records the first semiannual interest payment of $40,000 ($800,000 × .10 × 1/2) on July 1, 2010, as follows.

It records accrued interest expense at December 31, 2010 (year-end) as follows.

If Buchanan Company issues the $800,000 of bonds on January 1, 2010, at 97 (meaning 97 percent of par), it records the issuance as follows.

Recall from our earlier discussion that because of its relation to interest, companies amortize the discount and charge it to interest expense over the period of time that the bonds are outstanding.

The straight-line method amortizes a constant amount each interest period (in this case 20 interest periods).[207] For example, using the bond discount of $24,000, Buchanan amortizes $1,200 to interest expense each period for 20 periods ($24,000 ÷ 20).

Buchanan records the first semiannual interest payment of $40,000 ($800,000 × 10% × ½) and the bond discount on July 1, 2010 as follows:

At December 31, 2010, Buchanan makes the following adjusting entry:

At the end of the first year, 2010, the balance in the Discount on Bonds Payable account is $21,600 ($24,000 − $1,200 − $1,200). Over the term of the bonds, the balance in the Discount on Bonds Payable will decrease by the same amount until it has zero balance at the maturity date of the bonds.

If instead of issuing the bonds on January 1, 2010, Buchanan dates and sells the bonds on October 1, 2010, and if the fiscal year of the corporation ends on December 31, the discount amortized during 2010 would be only 3/12 of 1/10 of $24,000, or $600. Buchanan must also record three months of accrued interest on December 31.

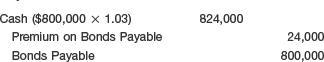

Premium on Bonds Payable is accounted for in a manner similar to that for Discount on Bonds Payable. If Buchanan dates and sells 10-year bonds with a par value of $800,000 on January 1, 2010, at 103, it records the issuance as follows.

With the bond premium of $24,000, Buchanan amortizes $1,200 to interest expense each period for 20 periods ($24,000 ÷ 20).

Buchanan records the first semiannual interest payment of $40,000 ($800,000 × 10% × ½) and the bond premium on July 1, 2010 as follows:

At December 31, 2010, Buchanan makes the following adjusting entry:

Amortization of a discount increases bond interest expense. Amortization of a premium decreases bond interest expense. Later in the chapter we discuss amortization of a discount or premium under the effective-interest method.

The issuer may call some bonds at a stated price after a certain date. This call feature gives the issuing corporation the opportunity to reduce its bonded indebtedness or take advantage of lower interest rates. Whether callable or not, a company must amortize any premium or discount over the bond's life to maturity because early redemption (call of the bond) is not a certainty.

Companies usually make bond interest payments semiannually, on dates specified in the bond indenture. When companies issue bonds on other than the interest payment dates, buyers of the bonds will pay the seller the interest accrued from the last interest payment date to the date of issue. The purchasers of the bonds, in effect, pay the bond issuer in advance for that portion of the full six-months' interest payment to which they are not entitled because they have not held the bonds for that period. Then, on the next semiannual interest payment date, purchasers will receive the full six-months' interest payment.

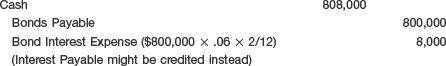

To illustrate, assume that on March 1, 2010, Taft Corporation issues 10-year bonds, dated January 1, 2010, with a par value of $800,000. These bonds have an annual interest rate of 6 percent, payable semiannually on January 1 and July 1. Because Taft issues the bonds between interest dates, it records the bond issuance at par plus accrued interest as follows.

The purchaser advances two months' interest. On July 1, 2010, four months after the date of purchase, Taft pays the purchaser six months' interest. Taft makes the following entry on July 1, 2010.

The Bond Interest Expense account now contains a debit balance of $16,000, which represents the proper amount of interest expense—four months at 6 percent on $800,000.

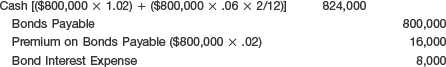

The illustration above was simplified by having the January 1, 2010, bonds issued on March 1, 2010, at par. If, however, Taft issued the 6 percent bonds at 102, its March 1 entry would be:

Taft would amortize the premium from the date of sale (March 1, 2010), not from the date of the bonds (January 1, 2010).

The preferred procedure for amortization of a discount or premium is the effective-interest method (also called present value amortization). Under the effective-interest method, companies:

Compute bond interest expense first by multiplying the carrying value (book value) of the bonds at the beginning of the period by the effective interest rate.[208]

Determine the bond discount or premium amortization next by comparing the bond interest expense with the interest (cash) to be paid.

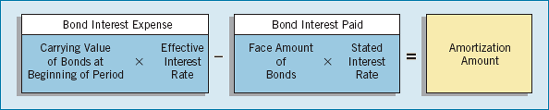

Illustration 14-3 depicts graphically the computation of the amortization.

The effective-interest method produces a periodic interest expense equal to a constant percentage of the carrying value of the bonds. Since the percentage is the effective rate of interest incurred by the borrower at the time of issuance, the effective-interest method matches expenses with revenues better than the straight-line method.

Both the effective-interest and straight-line methods result in the same total amount of interest expense over the term of the bonds. However, when the annual amounts are materially different, generally accepted accounting principles require use of the effective-interest method. [1]

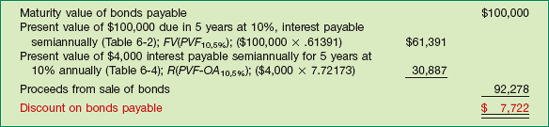

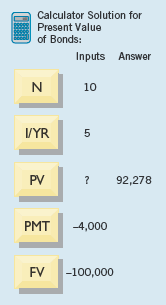

To illustrate amortization of a discount under the effective-interest method, Evermaster Corporation issued $100,000 of 8 percent term bonds on January 1, 2010, due on January 1, 2015, with interest payable each July 1 and January 1. Because the investors required an effective-interest rate of 10 percent, they paid $92,278 for the $100,000 of bonds, creating a $7,722 discount. Evermaster computes the $7,722 discount as follows.[209]

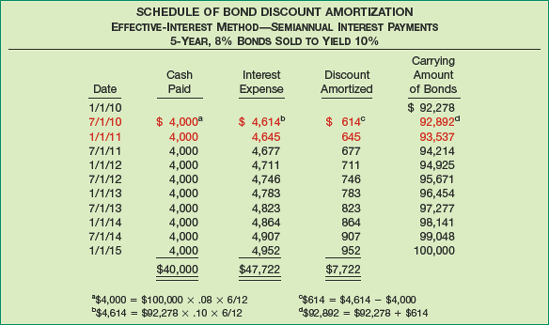

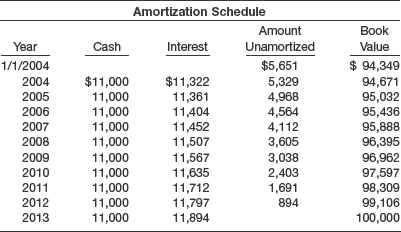

The five-year amortization schedule appears in Illustration 14-5.

Evermaster records the issuance of its bonds at a discount on January 1, 2010, as follows:

It records the first interest payment on July 1, 2010, and amortization of the discount as follows:

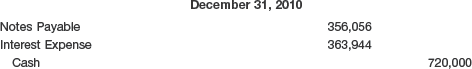

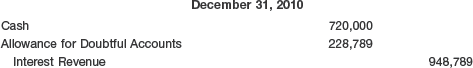

Evermaster records the interest expense accrued at December 31, 2010 (year-end) and amortization of the discount as follows:

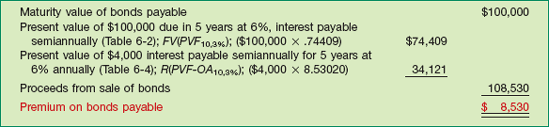

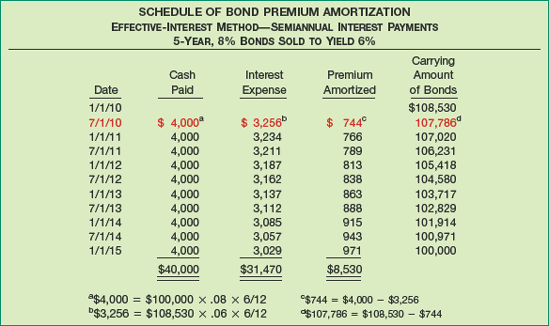

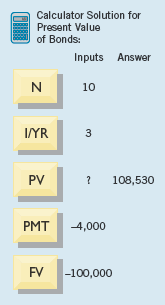

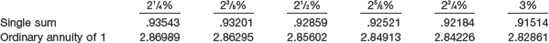

Now assume that for the bond issue described above, investors are willing to accept an effective interest rate of 6 percent. In that case, they would pay $108,530 or a premium of $8,530, computed as follows.

The five-year amortization schedule appears in Illustration 14-7.

Evermaster records the issuance of its bonds at a premium on January 1, 2010, as follows:

Evermaster records the first interest payment on July 1, 2010, and amortization of the premium as follows:

Evermaster should amortize the discount or premium as an adjustment to interest expense over the life of the bond in such a way as to result in a constant rate of interest when applied to the carrying amount of debt outstanding at the beginning of any given period.

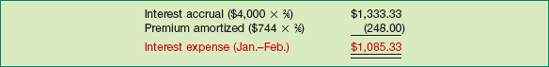

In our previous examples, the interest payment dates and the date the financial statements were issued were the same. For example, when Evermaster sold bonds at a premium (page 698), the two interest payment dates coincided with the financial reporting dates. However, what happens if Evermaster wishes to report financial statements at the end of February 2010? In this case, the company prorates the premium by the appropriate number of months, to arrive at the proper interest expense, as follows.

Evermaster records this accrual as follows.

If the company prepares financial statements six months later, it follows the same procedure. That is, the premium amortized would be as follows.

The interest-accrual computation is much simpler if the company uses the straight-line method. For example, the total premium is $8,530, which Evermaster allocates evenly over the five-year period. Thus, premium amortization per month is $142.17 ($8,530 ÷ 60 months).

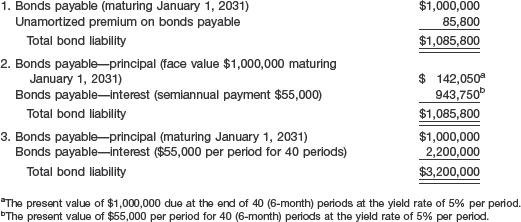

Discount on bonds payable is not an asset. It does not provide any future economic benefit. In return for the use of borrowed funds, a company must pay interest. A bond discount means that the company borrowed less than the face or maturity value of the bond. It therefore faces an actual (effective) interest rate higher than the stated (nominal) rate. Conceptually, discount on bonds payable is a liability valuation account. That is, it reduces the face or maturity amount of the related liability.[210] This account is referred to as a contra account.

Similarly, premium on bonds payable has no existence apart from the related debt. The lower interest cost results because the proceeds of borrowing exceed the face or maturity amount of the debt. Conceptually, premium on bonds payable is a liability valuation account. It adds to the face or maturity amount of the related liability.[211] This account is referred to as an adjunct account. As a result, companies report bond discounts and bond premiums as a direct deduction from or addition to the face amount of the bond.

The issuance of bonds involves engraving and printing costs, legal and accounting fees, commissions, promotion costs, and other similar charges. Companies are required to charge these costs to an asset account, often referred to as Unamortized Bond Issue Costs. Companies then allocate these Unamortized Bond Issue Costs over the life of the debt, in a manner similar to that used for discount on bonds. [2]

We disagree with this approach. Unamortized bond issue cost in our view is an expense (or a reduction of the related liability).

Apparently the FASB also disagrees with the current GAAP treatment and notes in Concepts Statement No. 6 that debt issue cost is not considered an asset because it provides no future economic benefit. The cost of issuing bonds, in effect, reduces the proceeds of the bonds issued and increases the effective interest rate. Companies may thus account for it the same as the unamortized discount.

There is an obvious difference between GAAP and Concepts Statement No. 6's view of debt issue costs. However, until an issued standard supersedes existing GAAP, unamortized bond issue costs are treated as a deferred charge and amortized over the life of the debt.

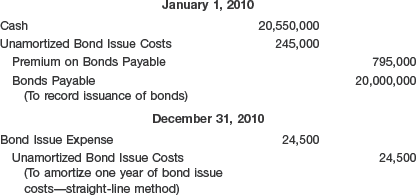

To illustrate the accounting for costs of issuing bonds, assume that Microchip Corporation sold $20,000,000 of 10-year debenture bonds for $20,795,000 on January 1, 2010 (also the date of the bonds). Costs of issuing the bonds were $245,000. Microchip records the issuance of the bonds and amortization of the bond issue costs as follows.

Microchip continues to amortize the bond issue costs in the same way over the life of the bonds. Although the effective-interest method is preferred, in practice companies may use the straight-line method to amortize bond issue costs because it is easier and the results are not materially different.

How do companies record the payment of debt—often referred to as extinguishment of debt? If a company holds the bonds (or any other form of debt security) to maturity, the answer is straightforward: The company does not compute any gains or losses. It will have fully amortized any premium or discount and any issue costs at the date the bonds mature. As a result, the carrying amount will equal the maturity (face) value of the bond. As the maturity or face value will also equal the bond's market value at that time, no gain or loss exists.

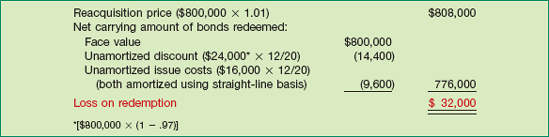

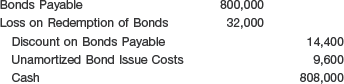

In some cases, a company extinguishes debt before its maturity date.[212] The amount paid on extinguishment or redemption before maturity, including any call premium and expense of reacquisition, is called the reacquisition price. On any specified date, the net carrying amount of the bonds is the amount payable at maturity, adjusted for unamortized premium or discount, and cost of issuance. Any excess of the net carrying amount over the reacquisition price is a gain from extinguishment. The excess of the reacquisition price over the net carrying amount is a loss from extinguishment. At the time of reacquisition, the unamortized premium or discount, and any costs of issue applicable to the bonds, must be amortized up to the reacquisition date.

To illustrate, assume that on January 1, 2003, General Bell Corp. issued at 97 bonds with a par value of $800,000, due in 20 years. It incurred bond issue costs totaling $16,000. Eight years after the issue date, General Bell calls the entire issue at 101 and cancels it.[213] At that time, the unamortized discount balance is $14,400, and the unamortized issue cost balance is $9,600. Illustration 14-10 indicates how General Bell computes the loss on redemption (extinguishment).

General Bell records the reacquisition and cancellation of the bonds as follows:

Note that it is often advantageous for the issuer to acquire the entire outstanding bond issue and replace it with a new bond issue bearing a lower rate of interest. The replacement of an existing issuance with a new one is called refunding. Whether the early redemption or other extinguishment of outstanding bonds is a nonrefunding or a refunding situation, a company should recognize the difference (gain or loss) between the reacquisition price and the net carrying amount of the redeemed bonds in income of the period of redemption.[214]

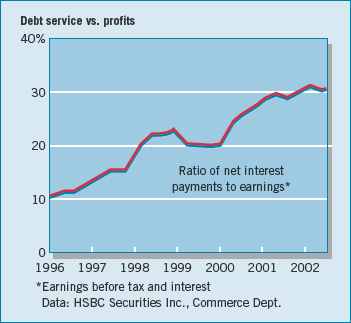

As the opening story in the chapter indicated, high debt levels translate into high interest costs, which are a drag on profitability. The chart below shows that the ratio of interest payments to earnings has been on an upward trend. This is bad news for companies that have a lot of debt on their balance sheet.

However, in a low interest rate environment, as experienced at least through 2008, companies with debt-laden balance sheets benefit when interest rates fall. Exelon Corp., a Chicago-based energy company, is a good example. Exelon has been refinancing its long-term debt by retiring bonds with 6.5 percent rates in exchange for newly issued bonds with rates ranging from 3.7 percent to 5.9 percent. This refinancing saved Exelon approximately $30 million dollars in annual interest costs. Exelon was able to get out of its higher cost debt when the getting was good. Other debt-laden companies might not fare so well if interest rates rise before they can refinance.

Source: Adapted from Gregory Zuckerman, "Climb of Corporate Debt Trips Analysts' Alarm," Wall Street Journal (December 31, 2001), p. C1; and James Mehring, "The Dead Weight of Debt," Business Week (February 24, 2003), p. 60.

The difference between current notes payable and long-term notes payable is the maturity date. As discussed in Chapter 13, short-term notes payable are those that companies expect to pay within a year or the operating cycle—whichever is longer. Long-term notes are similar in substance to bonds in that both have fixed maturity dates and carry either a stated or implicit interest rate. However, notes do not trade as readily as bonds in the organized public securities markets. Noncorporate and small corporate enterprises issue notes as their long-term instruments. Larger corporations issue both long-term notes and bonds.

Accounting for notes and bonds is quite similar. Like a bond, a note is valued at the present value of its future interest and principal cash flows. The company amortizes any discount or premium over the life of the note, just as it would the discount or premium on a bond.[215] Companies compute the present value of an interest-bearing note, record its issuance, and amortize any discount or premium and accrual of interest in the same way that they do for bonds (as shown on pages 692–700 of this chapter).

As you might expect, accounting for long-term notes payable parallels accounting for long-term notes receivable as was presented in Chapter 7.

In Chapter 7, we discussed the recognition of a $10,000, three-year note Scandinavian Imports issued at face value to Bigelow Corp. In this transaction, the stated rate and the effective rate were both 10 percent. The time diagram and present value computation on page 332 of Chapter 7 (see Illustration 7-9) for Bigelow Corp. would be the same for the issuer of the note, Scandinavian Imports, in recognizing a note payable. Because the present value of the note and its face value are the same, $10,000, Scandinavian would recognize no premium or discount. It records the issuance of the note as follows.

Scandinavian Imports would recognize the interest incurred each year as follows.

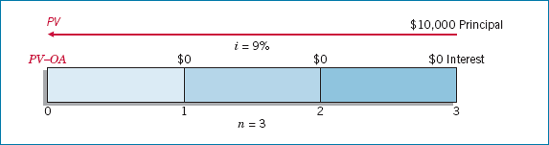

If a company issues a zero-interest-bearing (non-interest-bearing) note[216] solely for cash, it measures the note's present value by the cash received. The implicit interest rate is the rate that equates the cash received with the amounts to be paid in the future. The issuing company records the difference between the face amount and the present value (cash received) as a discount and amortizes that amount to interest expense over the life of the note.

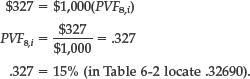

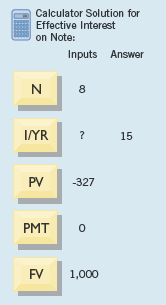

An example of such a transaction is Beneficial Corporation's offering of $150 million of zero-coupon notes (deep-discount bonds) having an eight-year life. With a face value of $1,000 each, these notes sold for $327—a deep discount of $673 each. The present value of each note is the cash proceeds of $327. We can calculate the interest rate by determining the rate that equates the amount the investor currently pays with the amount to be received in the future. Thus, Beneficial amortizes the discount over the eight-year life of the notes using an effective interest rate of 15 percent.[217]

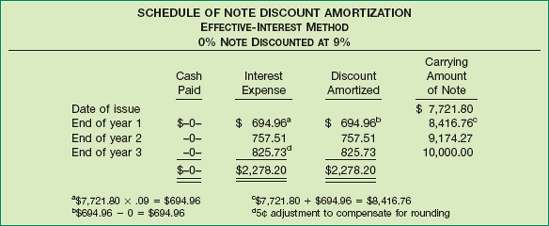

To illustrate the entries and the amortization schedule, assume that Turtle Cove Company issued the three-year, $10,000, zero-interest-bearing note to Jeremiah Company illustrated on page 333 of Chapter 7 (notes receivable). The implicit rate that equated the total cash to be paid ($10,000 at maturity) to the present value of the future cash flows ($7,721.80 cash proceeds at date of issuance) was 9 percent. (The present value of $1 for 3 periods at 9 percent is $0.77218.) Illustration 14-11 shows the time diagram for the single cash flow.

Turtle Cove records issuance of the note as follows.

Turtle Cove amortizes the discount and recognizes interest expense annually using the effective-interest method. Illustration 14-12 (on page 705) shows the three-year discount amortization and interest expense schedule. (This schedule is similar to the note receivable schedule of Jeremiah Company in Illustration 7-11.)

Turtle Cove records interest expense at the end of the first year using the effective-interest method as follows.

The total amount of the discount, $2,278.20 in this case, represents the expense that Turtle Cove Company will incur on the note over the three years.

The zero-interest-bearing note above is an example of the extreme difference between the stated rate and the effective rate. In many cases, the difference between these rates is not so great.

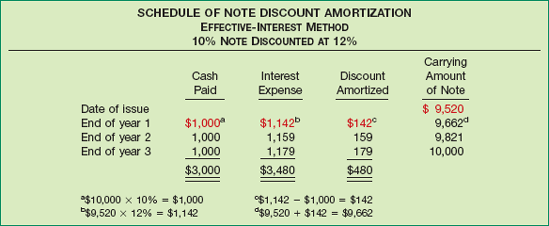

Consider the example from Chapter 7 where Marie Co. issued for cash a $10,000, three-year note bearing interest at 10 percent to Morgan Corp. The market rate of interest for a note of similar risk is 12 percent. Illustration 7-12 (page 334) shows the time diagram depicting the cash flows and the computation of the present value of this note. In this case, because the effective rate of interest (12%) is greater than the stated rate (10%), the present value of the note is less than the face value. That is, the note is exchanged at a discount. Marie Co. records the issuance of the note as follows.

Marie Co. then amortizes the discount and recognizes interest expense annually using the effective-interest method. Illustration 14-13 shows the three-year discount amortization and interest expense schedule.

Marie Co. records payment of the annual interest and amortization of the discount for the first year as follows (amounts per amortization schedule).

When the present value exceeds the face value, Marie Co. exchanges the note at a premium. It does so by recording the premium as a credit and amortizing it using the effective-interest method over the life of the note as annual reductions in the amount of interest expense recognized.

Sometimes, companies may receive property, goods, or services in exchange for a note payable. When exchanging the debt instrument for property, goods, or services in a bargained transaction entered into at arm's length, the stated interest rate is presumed to be fair unless:

No interest rate is stated, or

The stated interest rate is unreasonable, or

The stated face amount of the debt instrument is materially different from the current cash sales price for the same or similar items or from the current fair value of the debt instrument.

In these circumstances the company measures the present value of the debt instrument by the fair value of the property, goods, or services or by an amount that reasonably approximates the fair value of the note. [5] If there is no stated rate of interest, the amount of interest is the difference between the face amount of the note and the fair value of the property.

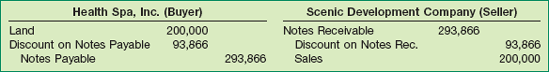

For example, assume that Scenic Development Company sells land having a cash sale price of $200,000 to Health Spa, Inc. In exchange for the land, Health Spa gives a five-year, $293,866, zero-interest-bearing note. The $200,000 cash sale price represents the present value of the $293,866 note discounted at 8 percent for five years. Should both parties record the transaction on the sale date at the face amount of the note, which is $293,866? No—if they did, Health Spa's Land account and Scenic's sales would be overstated by $93,866 (the interest for five years at an effective rate of 8 percent). Similarly, interest revenue to Scenic and interest expense to Health Spa for the five-year period would be understated by $93,866.

Because the difference between the cash sale price of $200,000 and the $293,866 face amount of the note represents interest at an effective rate of 8 percent, the companies' transaction is recorded at the exchange date as follows.

During the five-year life of the note, Health Spa amortizes annually a portion of the discount of $93,866 as a charge to interest expense. Scenic Development records interest revenue totaling $93,866 over the five-year period by also amortizing the discount. The effective-interest method is required, unless the results obtained from using another method are not materially different from those that result from the effective-interest method.

In note transactions, the effective or market interest rate is either evident or determinable by other factors involved in the exchange, such as the fair value of what is given or received. But, if a company cannot determine the fair value of the property, goods, services, or other rights, and if the note has no ready market, the problem of determining the present value of the note is more difficult. To estimate the present value of a note under such circumstances, a company must approximate an applicable interest rate that may differ from the stated interest rate. This process of interest-rate approximation is called imputation, and the resulting interest rate is called an imputed interest rate.

The prevailing rates for similar instruments of issuers with similar credit ratings affect the choice of a rate. Other factors such as restrictive covenants, collateral, payment schedule, and the existing prime interest rate also play a part. Companies determine the imputed interest rate when they issue a note; any subsequent changes in prevailing interest rates are ignored.

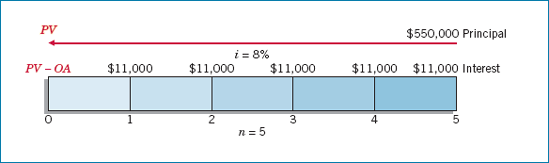

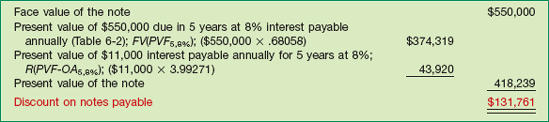

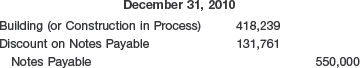

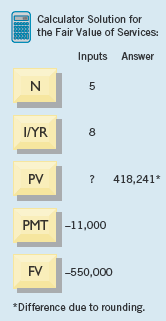

To illustrate, assume that on December 31, 2010, Wunderlich Company issued a promissory note to Brown Interiors Company for architectural services. The note has a face value of $550,000, a due date of December 31, 2015, and bears a stated interest rate of 2 percent, payable at the end of each year. Wunderlich cannot readily determine the fair value of the architectural services, nor is the note readily marketable. On the basis of Wunderlich's credit rating, the absence of collateral, the prime interest rate at that date, and the prevailing interest on Wunderlich's other outstanding debt, the company imputes an 8 percent interest rate as appropriate in this circumstance. Illustration 14-15 shows the time diagram depicting both cash flows.

The present value of the note and the imputed fair value of the architectural services are determined as follows.

Wunderlich records issuance of the note in payment for the architectural services as follows.

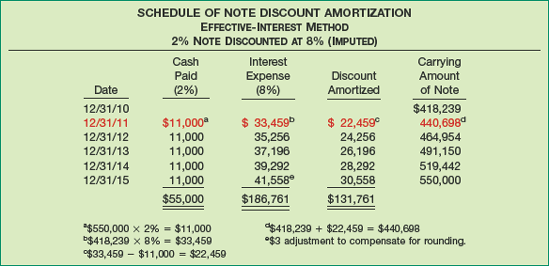

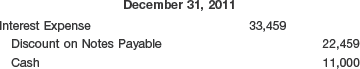

The five-year amortization schedule appears below.

Wunderlich records payment of the first year's interest and amortization of the discount as follows.

The most common form of long-term notes payable is a mortgage note payable. A mortgage note payable is a promissory note secured by a document called a mortgage that pledges title to property as security for the loan. Individuals, proprietorships, and partnerships use mortgage notes payable more frequently than do corporations. (Corporations usually find that bond issues offer advantages in obtaining large loans.)

The borrower usually receives cash for the face amount of the mortgage note. In that case, the face amount of the note is the true liability, and no discount or premium is involved. When the lender assesses "points," however, the total amount received by the borrower is less than the face amount of the note.[218] Points raise the effective interest rate above the rate specified in the note. A point is 1 percent of the face of the note.

For example, assume that Harrick Co. borrows $1,000,000, signing a 20-year mortgage note with a stated interest rate of 10.75 percent as part of the financing for a new plant. If Associated Savings demands 4 points to close the financing, Harrick will receive 4 percent less than $1,000,000—or $960,000—but it will be obligated to repay the entire $1,000,000 at the rate of $10,150 per month. Because Harrick received only $960,000, and must repay $1,000,000, its effective interest rate is increased to approximately 11.3 percent on the money actually borrowed.

On the balance sheet, Harrick should report the mortgage note payable as a liability using a title such as "Mortgage Notes Payable" or "Notes Payable—Secured," with a brief disclosure of the property pledged in notes to the financial statements.

Mortgages may be payable in full at maturity or in installments over the life of the loan. If payable at maturity, Harrick classifies its mortgage payable as a long-term liability on the balance sheet until such time as the approaching maturity date warrants showing it as a current liability. If it is payable in installments, Harrick shows the current installments due as current liabilities, with the remainder as a long-term liability.

Lenders have partially replaced the traditional fixed-rate mortgage with alternative mortgage arrangements. Most lenders offer variable-rate mortgages (also called floating-rate or adjustable-rate mortgages) featuring interest rates tied to changes in the fluctuating market rate. Generally the variable-rate lenders adjust the interest rate at either one- or three-year intervals, pegging the adjustments to changes in the prime rate or the U.S. Treasury bond rate.

Reporting of long-term debt is one of the most controversial areas in financial reporting. Because long-term debt has a significant impact on the cash flows of the company, reporting requirements must be substantive and informative. One problem is that the definition of a liability established in Concepts Statement No. 6 and the recognition criteria established in Concepts Statement No. 5 are sufficiently imprecise that some continue to argue that certain obligations need not be reported as debt.

What do Krispy Kreme, Cisco, Enron, and Adelphia Communications have in common? They all have been accused of using off-balance-sheet financing to minimize the reporting of debt on their balance sheets. Off-balance-sheet financing is an attempt to borrow monies in such a way to prevent recording the obligations. It has become an issue of extreme importance. Many allege that Enron, in one of the largest corporate failures on record, hid a considerable amount of its debt off the balance sheet. As a result, any company that uses off-balance-sheet financing today risks investors dumping their stock. Consequently (as discussed in the opening story), their share price will suffer. Nevertheless, a considerable amount of off-balance-sheet financing continues to exist. As one writer noted, "The basic drives of humans are few: to get enough food, to find shelter, and to keep debt off the balance sheet."

Off-balance-sheet financing can take many different forms:

Non-Consolidated Subsidiary: Under GAAP, a parent company does not have to consolidate a subsidiary company that is less than 50 percent owned. In such cases, the parent therefore does not report the assets and liabilities of the subsidiary. All the parent reports on its balance sheet is the investment in the subsidiary. As a result, users of the financial statements may not understand that the subsidiary has considerable debt for which the parent may ultimately be liable if the subsidiary runs into financial difficulty.

Special Purpose Entity (SPE): A company creates a special purpose entity to perform a special project. To illustrate, assume that Clarke Company decides to build a new factory. However, management does not want to report the plant or the borrowing used to fund the construction on its balance sheet. It therefore creates an SPE, the purpose of which is to build the plant. (This arrangement is called a project financing arrangement.) The SPE finances and builds the plant. In return, Clarke guarantees that it or some outside party will purchase all the products produced by the plant. (Some refer to this as a take-or-pay contract). As a result, Clarke might not report the asset or liability on its books. The accounting rules in this area are complex; we discuss the accounting for SPEs in Appendix 17B.

Operating Leases: Another way that companies keep debt off the balance sheet is by leasing. Instead of owning the assets, companies lease them. Again, by meeting certain conditions, the company has to report only rent expense each period and to provide note disclosure of the transaction. Note that SPEs often use leases to accomplish off-balance-sheet treatment. We discuss accounting for lease transactions extensively in Chapter 21.

Why do companies engage in off-balance-sheet financing? A major reason is that many believe that removing debt enhances the quality of the balance sheet and permits credit to be obtained more readily and at less cost.

Second, loan covenants often limit the amount of debt a company may have. As a result, the company uses off-balance-sheet financing, because these types of commitments might not be considered in computing the debt limitation.

Third, some argue that the asset side of the balance sheet is severely understated. For example, companies that use LIFO costing for inventories and depreciate assets on an accelerated basis will often have carrying amounts for inventories and property, plant, and equipment that are much lower than their fair values. As an offset to these lower values, some believe that part of the debt does not have to be reported. In other words, if companies report assets at fair values, less pressure would undoubtedly exist for off-balance-sheet financing arrangements.

Whether the arguments above have merit is debatable. The general idea of "out of sight, out of mind" may not be true in accounting. Many users of financial statements indicate that they factor these off-balance-sheet financing arrangements into their computations when assessing debt to equity relationships. Similarly, many loan covenants also attempt to account for these complex arrangements. Nevertheless, many companies still believe that benefits will accrue if they omit certain obligations from the balance sheet.

As a response to off-balance-sheet financing arrangements, the FASB has increased disclosure (note) requirements. This response is consistent with an "efficient markets" philosophy: the important question is not whether the presentation is off-balance-sheet or not, but whether the items are disclosed at all. In addition, the SEC, in response to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, now requires companies to provide related information in their management discussion and analysis sections. Specifically, companies must disclose (1) all contractual obligations in a tabular format and (2) contingent liabilities and commitments in either a textual or tabular format.[219]

We believe that recording more obligations on the balance sheet will enhance financial reporting. Given the problems with companies such as Enron, Dynegy, Williams Company, Adelphia Communications, and Calpine, and the Sarbanes-Oxley requirements, we expect that less off-balance-sheet financing will occur in the future.

The off-balance-sheet world is slowly but surely becoming more on-balance-sheet. New interpretations on guarantees (discussed in Chapter 13) and variable interest entities (discussed in Appendix 17B) are doing their part to increase the amount of debt reported on corporate balance sheets.

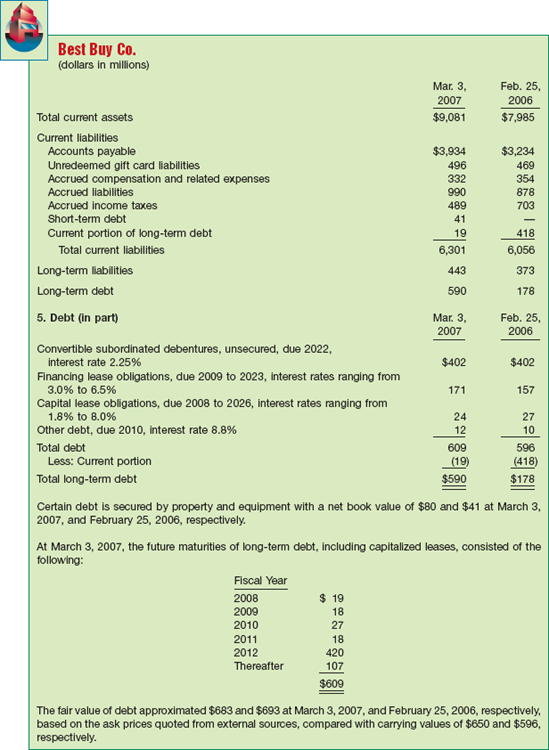

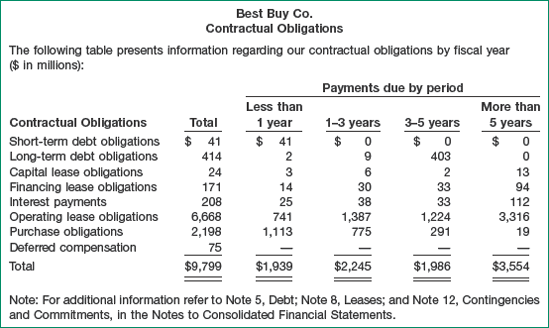

In addition, the SEC recently issued a rule that requires companies to disclose off-balance-sheet arrangements and contractual obligations that currently have, or are reasonably likely to have, a material future effect on the companies' financial condition. Companies now must include a tabular disclosure (following a prescribed format) in the management discussion and analysis section of the annual report. Presented below is Best Buy's tabular disclosure of its contractual obligations.

Enron's abuse of off-balance-sheet financing to hide debt was shocking and inappropriate. One silver lining in the Enron debacle however is that the standard-setting bodies in the accounting profession are now providing increased guidance on companies' reporting of contractual obligations. We believe the new SEC rule which requires companies to report their obligations over a period of time will be extremely useful to the investment community.

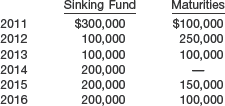

Companies that have large amounts and numerous issues of long-term debt frequently report only one amount in the balance sheet, supported with comments and schedules in the accompanying notes. Long-term debt that matures within one year should be reported as a current liability, unless using noncurrent assets to accomplish retirement. If the company plans to refinance debt, convert it into stock, or retire it from a bond retirement fund, it should continue to report the debt as noncurrent. However, the company should disclose the method it will use in its liquidation. [6], [7]

Note disclosures generally indicate the nature of the liabilities, maturity dates, interest rates, call provisions, conversion privileges, restrictions imposed by the creditors, and assets designated or pledged as security. Companies should show any assets pledged as security for the debt in the assets section of the balance sheet. The fair value of the long-term debt should also be disclosed if it is practical to estimate fair value. Finally, companies must disclose future payments for sinking fund requirements and maturity amounts of long-term debt during each of the next five years. These disclosures aid financial statement users in evaluating the amounts and timing of future cash flows. Illustration 14-18 shows an example of the type of information provided for Best Buy Co. Note that if the company has any off-balance-sheet financing, it must provide extensive note disclosure. [8]

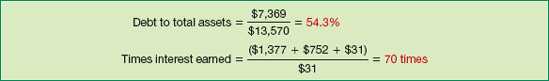

Long-term creditors and stockholders are interested in a company's long-run solvency, particularly its ability to pay interest as it comes due and to repay the face value of the debt at maturity. Debt to total assets and times interest earned are two ratios that provide information about debt-paying ability and long-run solvency.

The debt to total assets ratio measures the percentage of the total assets provided by creditors. To compute it, divide total debt (both current and long-term liabilities) by total assets, as Illustration 14-19 shows.

The higher the percentage of debt to total assets, the greater the risk that the company may be unable to meet its maturing obligations.

The times interest earned ratio indicates the company's ability to meet interest payments as they come due. As shown in Illustration 14-20, it is computed by dividing income before interest expense and income taxes by interest expense.

To illustrate these ratios, we use data from Best Buy's 2007 annual report. Best Buy has total liabilities of $7,369 million, total assets of $13,570 million, interest expense of $31 million, income taxes of $752 million, and net income of $1,377 million. We compute Best Buy's debt to total assets and times interest earned ratios as shown in Illustration 14-21.

Even though Best Buy has a relatively high debt to total assets percentage of 54.3 percent, its interest coverage of 70 times indicates it can easily meet its interest payments as they come due.

iGAAP and U.S. GAAP have similar definitions for liabilities. iGAAP related to reporting and recognition of liabilities is found in IAS 1 ("Presentation of Financial Statements") and IAS 37 ("Provisions, Contingent Liabilities, and Contingent Assets").

Similar to U.S. practice, iGAAP requires that companies present current and noncurrent liabilities on the face of the balance sheet, with current liabilities generally presented in order of liquidity.

Under iGAAP, the measurement of a provision related to a contingency is based on the best estimate of the expenditure required to settle the obligation. If a range of estimates is predicted and no amount in the range is more likely than any other amount in the range, the "mid-point" of the range is used to measure the liability. In U.S GAAP, the minimum amount in a range is used.

Both GAAPs prohibit the recognition of liabilities for future losses. However, iGAAP permits recognition of a restructuring liability, once a company has committed to a restructuring plan. U.S. GAAP has additional criteria (i.e., related to communicating the plan to employees) before a restructuring liability can be established.

iGAAP and U.S. GAAP are similar in the treatment of asset retirement obligations (AROs). However, the recognition criteria for an ARO are more stringent under U.S. GAAP: The ARO is not recognized unless there is a present legal obligation and the fair value of the obligation can be reasonably estimated.

iGAAP and U.S. GAAP are similar in their treatment of contingencies. However, the criteria for recognizing contingent assets are less stringent in the U.S. Under U.S. GAAP, contingent assets for insurance recoveries are recognized if probable; iGAAP requires the recovery be "virtually certain" before recognition of an asset is permitted.

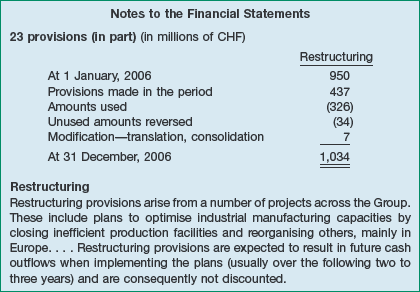

As indicated, iGAAP and U.S. GAAP differ as the criteria to be used in recording restructuring liabilities. The following disclosure by Nestlé Group in its 2006 annual report reflects application of iGAAP to a restructuring situation.

As indicated in the chapter, the establishment of restructuring liabilities for future costs can be used as a "cookie jar" to manage net income. That is, companies can set up a liability and related expense charge in one period to reduce income and then reduce the liability in future periods to increase net income. For example, when Nestlé makes the following entry for the unused amounts reversed in 2006, it is able to increase its income by 34 million CHF.

We are not implying that Nestlé is using its reserve in inappropriate ways. Our point is that less-stringent iGAAP rules for establishing restructuring liabilities could be used as an earnings management tool.

As indicated in the Convergence Corner for Chapter 2, the IASB and FASB are working on a conceptual framework project, part of which will examine the definition of a liability. In addition, this project will address the difference in measurements used between iGAAP and U.S. GAAP for contingent liabilities. Also, in its project on business combinations, the IASB is considering changing it definition of a contingent asset to converge with U.S. GAAP.

Practically every day, the Wall Street Journal runs a story about some company in financial difficulty. Notable recent examples are Delphi, Northwest Airlines, and United Airlines. In most troubled-debt situations, the creditor usually first recognizes a loss on impairment. Subsequently, the creditor either modifies the terms of the loan or the debtor settles the loan on terms unfavorable to the creditor. In unusual cases, the creditor forces the debtor into bankruptcy in order to ensure the highest possible collection on the loan. Illustration 14A-1 shows this continuum.

To illustrate, consider the case of Huffy Corp., a name that adorned the first bicycle of many American children. Before its bankruptcy, Huffy's creditors likely recognized a loss on impairment. Subsequently, the creditors either modified the terms of the loan or settled it on terms unfavorable to the creditor. Finally, the creditors forced Huffy into bankruptcy, and the suppliers received a 30 percent equity stake in Huffy. These terms helped ensure the highest possible collection on the Huffy loan.

We discussed the accounting for loan impairments in Appendix 7B. The purpose of this appendix is to explain how creditors and debtors report information in financial statements related to troubled-debt restructurings.

A troubled-debt restructuring occurs when a creditor "for economic or legal reasons related to the debtor's financial difficulties grants a concession to the debtor that it would not otherwise consider." [9] Thus a troubled-debt restructuring does not apply to modifications of a debt obligation that reflect general economic conditions leading to a reduced interest rate. Nor does it apply to the refunding of an old debt with new debt having an effective interest rate approximately equal to that of similar debt issued by nontroubled debtors.

A troubled-debt restructuring involves one of two basic types of transactions:

In addition to using cash, settling a debt obligation can involve either a transfer of noncash assets (real estate, receivables, or other assets) or the issuance of the debtor's stock. In these situations, the creditor should account for the noncash assets or equity interest received at their fair value.

The debtor must determine the excess of the carrying amount of the payable over the fair value of the assets or equity transferred (gain). Likewise, the creditor must determine the excess of the receivable over the fair value of those same assets or equity interests transferred (loss). The debtor recognizes a gain equal to the amount of the excess. The creditor normally charges the excess (loss) against Allowance for Doubtful Accounts. In addition, the debtor recognizes a gain or loss on disposition of assets to the extent that the fair value of those assets differs from their carrying amount (book value).

Assume that American City Bank loaned $20,000,000 to Union Mortgage Company. Union Mortgage, in turn, invested these monies in residential apartment buildings. However, because of low occupancy rates, it cannot meet its loan obligations. American City Bank agrees to accept from Union Mortgage real estate with a fair value of $16,000,000 in full settlement of the $20,000,000 loan obligation. The real estate has a carrying value of $21,000,000 on the books of Union Mortgage. American City Bank (creditor) records this transaction as follows.

The bank records the real estate at fair value. Further, it makes a charge to the Allowance for Doubtful Accounts to reflect the bad debt write-off.

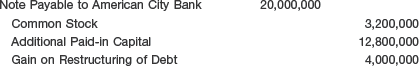

Union Mortgage (debtor) records this transaction as follows.

Union Mortgage has a loss on the disposition of real estate in the amount of $5,000,000 (the difference between the $21,000,000 book value and the $16,000,000 fair value). It should show this as an ordinary loss on the income statement. In addition, it has a gain on restructuring of debt of $4,000,000 (the difference between the $20,000,000 carrying amount of the note payable and the $16,000,000 fair value of the real estate).

Assume that American City Bank agrees to accept from Union Mortgage 320,000 shares of common stock ($10 par) that has a fair value of $16,000,000, in full settlement of the $20,000,000 loan obligation. American City Bank (creditor) records this transaction as follows.

It records the stock as an investment at the fair value at the date of restructure.

Union Mortgage (debtor) records this transaction as follows.

It records the stock issued in the normal manner. It records the difference between the par value and the fair value of the stock as additional paid-in capital.

In some cases, a debtor's serious short-run cash flow problems will lead it to request one or a combination of the following modifications:

Reduction of the stated interest rate.

Extension of the maturity date of the face amount of the debt.

Reduction of the face amount of the debt.

Reduction or deferral of any accrued interest.

The creditor's loss is based on expected cash flows discounted at the historical effective rate of the loan. [10] The debtor calculates its gain based on undiscounted amounts. As a consequence, the gain recorded by the debtor will not equal the loss recorded by the creditor under many circumstances.[220]

Two examples demonstrate the accounting for a troubled-debt restructuring by debtors and creditors:

The debtor does not record a gain.

The debtor does record a gain.

In both instances the creditor has a loss.

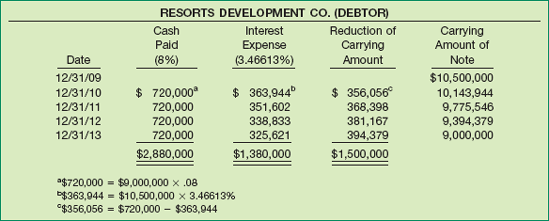

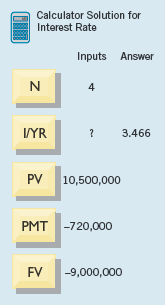

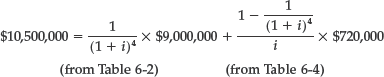

This example demonstrates a restructuring in which the debtor records no gain.[221] On December 31, 2009, Morgan National Bank enters into a debt restructuring agreement with Resorts Development Company, which is experiencing financial difficulties. The bank restructures a $10,500,000 loan receivable issued at par (interest paid to date) by:

Reducing the principal obligation from $10,500,000 to $9,000,000;

Extending the maturity date from December 31, 2009, to December 31, 2013; and

Reducing the interest rate from 12% to 8%.

The total future cash flow, after restructuring of $11,880,000 ($9,000,000 of principal plus $2,880,000 of interest payments[222]), exceeds the total pre-restructuring carrying amount of the debt of $10,500,000. Consequently, the debtor records no gain nor makes any adjustment to the carrying amount of the payable. As a result, Resorts Development (debtor) makes no entry at the date of restructuring.

The debtor must compute a new effective interest rate in order to record interest expense in future periods. The new effective interest rate equates the present value of the future cash flows specified by the new terms with the pre-restructuring carrying amount of the debt. In this case, Resorts Development computes the new rate by relating the pre-restructure carrying amount ($10,500,000) to the total future cash flow ($11,880,000). The rate necessary to discount the total future cash flow ($11,880,000), to a present value equal to the remaining balance ($10,500,000), is 3.46613%.[223]

On the basis of the effective rate of 3.46613%, the debtor prepares the schedule shown in Illustration 14A-2.

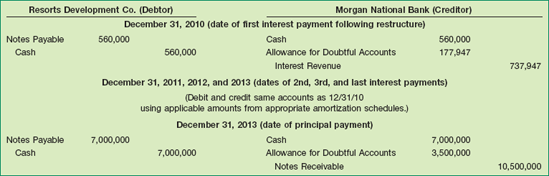

Thus, on December 31, 2010 (date of first interest payment after restructure), the debtor makes the following entry.

The debtor makes a similar entry (except for different amounts for debits to Notes Payable and Interest Expense) each year until maturity. At maturity, Resorts Development makes the following entry.

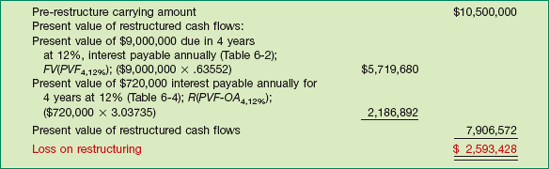

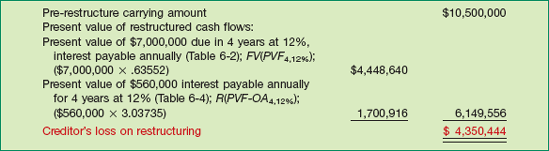

Morgan National Bank (creditor) must calculate its loss based on the expected future cash flows discounted at the historical effective rate of the loan. It calculates this loss as shown in Illustration 14A-3.

As a result, Morgan National Bank records bad debt expense as follows (assuming no establishment of an allowance balance from recognition of an impairment).

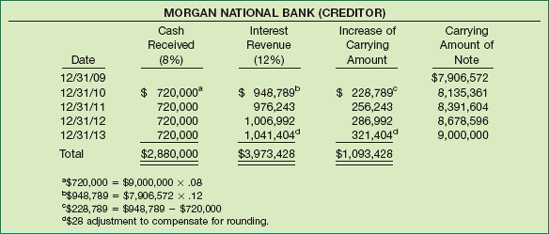

In subsequent periods, Morgan National Bank reports interest revenue based on the historical effective rate. Illustration 14A-4 provides the following interest and amortization information.

On December 31, 2010, Morgan National Bank makes the following entry.

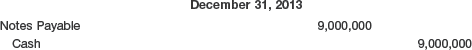

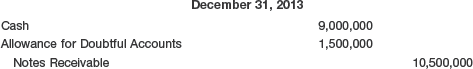

The creditor makes a similar entry (except for different amounts debited to Allowance for Doubtful Accounts and credited to Interest Revenue) each year until maturity. At maturity, the company makes the following entry.

If the pre-restructure carrying amount exceeds the total future cash flows as a result of a modification of the terms, the debtor records a gain. To illustrate, assume the facts in the previous example except that Morgan National Bank reduces the principal to $7,000,000 (and extends the maturity date to December 31, 2013, and reduces the interest from 12% to 8%). The total future cash flow is now $9,240,000 ($7,000,000 of principal plus $2,240,000 of interest[224]), which is $1,260,000 ($10,500,000 − $9,240,000) less than the pre-restructure carrying amount of $10,500,000.

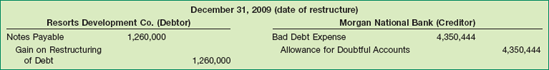

Under these circumstances, Resorts Development (debtor) reduces the carrying amount of its payable $1,260,000 and records a gain of $1,260,000. On the other hand, Morgan National Bank (creditor) debits its Bad Debt Expense for $4,350,444. Illustration 14A-5 shows this computation.

Illustration 14A-6 shows the entries to record the gain and loss on the debtor's and creditor's books at the date of restructure, December 31, 2009.

For Resorts Development (debtor), because the new carrying value of the note ($10,500,000 − $1,260,000 = $9,240,000) equals the sum of the undiscounted cash flows ($9,240,000), the imputed interest rate is 0 percent. Consequently, all of the future cash flows reduce the principal balance, and the company recognizes no interest expense.

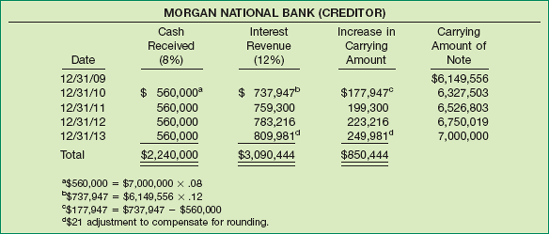

Morgan National reports the interest revenue in the same fashion as the previous example—that is, using the historical effective interest rate applied toward the newly discounted value of the note. Illustration 14A-7 (on page 722) shows interest computations.

The journal entries in Illustration 14A-8 demonstrate the accounting by debtor and creditor for periodic interest payments and final principal payment.

The accounting for troubled debt is complex because the accounting standards allow for use of different measurement standards to determine the loss or gain reported. In addition, the assets and liabilities reported are sometimes not stated at cost or fair value, but at amounts adjusted for certain events but not others. This cumbersome accounting demonstrates the need for adoption of a comprehensive fair-value model for financial instruments that is consistent with finance concepts for pricing these financial instruments.

FASB Codification References

FASB ASC 835-30-55-2. [Predecessor literature: "Interest on Receivables and Payables," Opinions of the Accounting Principles Board No. 21 (New York: AICPA, 1971), par. 16.]

FASB ASC 835-30-35-2. [Predecessor literature: "Interest on Receivables and Payables," Opinions of the Accounting Principles Board No. 21 (New York: AICPA, 1971), par. 15.]

FASB ASC 470-50-45. [Predecessor literature: "Rescission of FASB Statements No. 4, 44, and 64 and Technical Corrections," Statement of Accounting Standards No. 145 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2002).]

FASB ASC 835-30-15-3. [Predecessor literature: "Interest on Receivables and Payables," Opinions of the Accounting Principles Board No. 21 (New York: AICPA, 1971).]

FASB ASC 835-30-05-2. [Predecessor literature: "Interest on Receivables and Payables," Opinions of the Accounting Principles Board No. 21 (New York: AICPA, 1971), par. 12.]

FASB ASC 470-10-50-4. [Predecessor literature: "Balance Sheet Classification of Short-Term Obligations Expected to Be Refinanced," FASB Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 6 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1975), par. 15.]

FASB ASC 505-10-50-3. [Predecessor literature: "Disclosure of Information about Capital Structure," FASB Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 129 (Norwalk, Conn.: 1997), par. 4.]

FASB ASC 470-10-50-1. [Predecessor literature: "Disclosure of Long-Term Obligations," FASB Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 47 (Stamford, Conn.: 1981), par. 10.]

FASB ASC 310-40-15-2. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting by Debtors and Creditors for Troubled Debt Restructurings," FASB Statement No. 15 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, June, 1977), par. 1.]

FASB ASC 310-10-35. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting by Creditors for Impairment of a Loan," FASB Statement No. 114, (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, May 1993), par. 42.]

Note: All asterisked Questions, Exercises, and Problems relate to material in the appendix to the chapter.

(a) From what sources might a corporation obtain funds through long-term debt? (b) What is a bond indenture? What does it contain? (c) What is a mortgage?

Potlatch Corporation has issued various types of bonds such as term bonds, income bonds, and debentures. Differentiate between term bonds, mortgage bonds, collateral trust bonds, debenture bonds, income bonds, callable bonds, registered bonds, bearer or coupon bonds, convertible bonds, commodity-backed bonds, and deep discount bonds.

Distinguish between the following interest rates for bonds payable:

yield rate

nominal rate

stated rate

market rate

effective rate

Distinguish between the following values relative to bonds payable:

maturity value

face value

market value

par value

Under what conditions of bond issuance does a discount on bonds payable arise? Under what conditions of bond issuance does a premium on bonds payable arise?

How should discount on bonds payable be reported on the financial statements? Premium on bonds payable?

What are the two methods of amortizing discount and premium on bonds payable? Explain each.

Zopf Company sells its bonds at a premium and applies the effective-interest method in amortizing the premium. Will the annual interest expense increase or decrease over the life of the bonds? Explain.

Briggs and Stratton recently reported unamortized debt issue costs of $5.1 million. How should the costs of issuing these bonds be accounted for and classified in the financial statements?

Will the amortization of Discount on Bonds Payable increase or decrease Bond Interest Expense? Explain.

What is the "call" feature of a bond issue? How does the call feature affect the amortization of bond premium or discount?

Why would a company wish to reduce its bond indebtedness before its bonds reach maturity? Indicate how this can be done and the correct accounting treatment for such a transaction.

How are gains and losses from extinguishment of a debt classified in the income statement? What disclosures are required of such transactions?

What is done to record properly a transaction involving the issuance of a non-interest-bearing long-term note in exchange for property?

How is the present value of a non-interest-bearing note computed?

When is the stated interest rate of a debt instrument presumed to be fair?

What are the considerations in imputing an appropriate interest rate?

Differentiate between a fixed-rate mortgage and a variable-rate mortgage.

What disclosures are required relative to long-term debt and sinking fund requirements?

What is off-balance-sheet financing? Why might a company be interested in using off-balance-sheet financing?

What are some forms of off-balance-sheet financing?

Explain how a non-consolidated subsidiary can be a form of off-balance-sheet financing.

* What are the types of situations that result in troubled debt?

* What are the general rules for measuring gain or loss by both creditor and debtor in a troubled-debt restructuring involving a settlement?

*

In a troubled-debt situation, why might the creditor grant concessions to the debtor?

What type of concessions might a creditor grant the debtor in a troubled-debt situation?

* What are the general rules for measuring and recognizing gain or loss by both the debtor and the creditor in a troubled-debt restructuring involving a modification of terms?

* What is meant by "accounting symmetry" between the entries recorded by the debtor and creditor in a troubled-debt restructuring involving a modification of terms? In what ways is the accounting for troubled-debt restructurings non-symmetrical?

* Under what circumstances would a transaction be recorded as a troubled-debt restructuring by only one of the two parties to the transaction?

Bonds payable, due January 1, 2019

$2,000,000

Discount on bonds payable

88,000

Bond interest payable

80,000

Show how the above accounts should be presented on the December 31, 2011, balance sheet, including the proper classifications.

Bank loans payable of a winery, due March 10, 2014. (The product requires aging for 5 years before sale.)

Unamortized premium on bonds payable, of which $3,000 will be amortized during the next year.

Serial bonds payable, $1,000,000, of which $250,000 are due each July 31.

Amounts withheld from employees' wages for income taxes.

Notes payable due January 15, 2013.

Credit balances in customers' accounts arising from returns and allowances after collection in full of account.

Bonds payable of $2,000,000 maturing June 30, 2012.

Overdraft of $1,000 in a bank account. (No other balances are carried at this bank.)

Deposits made by customers who have ordered goods.

Instructions

Indicate whether each of the items above should be classified on December 31, 2011, as a current liability, a long-term liability, or under some other classification. Consider each one independently from all others; that is, do not assume that all of them relate to one particular business. If the classification of some of the items is doubtful, explain why in each case.

Discount on bonds payable

Interest expense (credit balance)

Unamortized bond issue costs

Gain on repurchase of debt

Mortgage payable (payable in equal amounts over next 3 years)

Debenture bonds payable (maturing in 5 years)

Premium on bonds payable

Notes payable (due in 4 years)

Income bonds payable (due in 3 years)

Instructions

Indicate how each of these items should be classified in the financial statements.

On January 1, 2010, Divac Company issued $300,000 of 9%, 10-year bonds at par. Interest is payable quarterly on April 1, July 1, October 1, and January 1.

On June 1, 2010, Verbitsky Company issued $200,000 of 12%, 10-year bonds dated January 1 at par plus accrued interest. Interest is payable semiannually on July 1 and January 1.

Instructions

For each of these two independent situations, prepare journal entries to record the following.

The issuance of the bonds.

The payment of interest on July 1.

The accrual of interest on December 31.

Instructions

Prepare the journal entries to record the following.

The issuance of the bonds.

The payment of interest and the related amortization on July 1, 2011.

The accrual of interest and the related amortization on December 31, 2011.

Instructions

Prepare the journal entries to record the following. (Round to the nearest dollar.)

The issuance of the bonds.

The payment of interest and related amortization on July 1, 2011.

The accrual of interest and the related amortization on December 31, 2011.

Instructions

Set up a schedule of interest expense and discount amortization under the straight-line method.

Instructions

Set up a schedule of interest expense and discount amortization under the effective-interest method. (Hint: The effective interest rate must be computed.)

Chinook Corporation incurred the following costs in connection with the issuance of bonds: (1) printing and engraving costs, $15,000; (2) legal fees, $49,000, and (3) commissions paid to underwriter, $60,000. What amount should be reported as Unamortized Bond Issue Costs, and where should this amount be reported on the balance sheet?

McEntire Co. sold $2,500,000 of 10%, 10-year bonds at 104 on January 1, 2010. The bonds were dated January 1, 2010, and pay interest on July 1 and January 1. If McEntire uses the straight-line method to amortize bond premium or discount, determine the amount of interest expense to be reported on July 1, 2010, and December 31, 2010.

Cheriel Inc. issued $600,000 of 9%, 10-year bonds on June 30, 2010, for $562,500. This price provided a yield of 10% on the bonds. Interest is payable semiannually on December 31 and June 30. If Cheriel uses the effective-interest method, determine the amount of interest expense to record if financial statements are issued on October 31, 2010.

Instructions

Prepare the journal entries to record the following transactions.

The issuance of the bonds on June 30, 2010.

The payment of interest and the amortization of the premium on December 31, 2010.

The payment of interest and the amortization of the premium on June 30, 2011.

The payment of interest and the amortization of the premium on December 31, 2011.

Show the proper balance sheet presentation for the liability for bonds payable on the December 31, 2011, balance sheet.

Provide the answers to the following questions.

What amount of interest expense is reported for 2011?

Will the bond interest expense reported in 2011 be the same as, greater than, or less than the amount that would be reported if the straight-line method of amortization were used?

Determine the total cost of borrowing over the life of the bond.

Will the total bond interest expense for the life of the bond be greater than, the same as, or less than the total interest expense if the straight-line method of amortization were used?

Instructions

Prepare the journal entry at the date of the bond issuance.

Prepare a schedule of interest expense and bond amortization for 2010–2012.

Prepare the journal entry to record the interest payment and the amortization for 2010.

Prepare the journal entry to record the interest payment and the amortization for 2012.

$10 million, 10-year, 13% unsecured bonds, interest payable quarterly. Bonds were priced to yield 12%.

$25 million par of 10-year, zero-coupon bonds at a price to yield 12% per year.

$15 million, 10-year, 10% mortgage bonds, interest payable annually to yield 12%.

Instructions

Prepare a schedule that identifies the following items for each bond: (1) maturity value, (2) number of interest periods over life of bond, (3) stated rate per each interest period, (4) effective interest rate per each interest period, (5) payment amount per period, and (6) present value of bonds at date of issue.

The bonds are callable at 101 (i.e., at 101% of face amount), and on January 2, 2010, Prebish called $1,000,000 face amount of the bonds and retired them.

Instructions

Ignoring income taxes, compute the amount of loss, if any, to be recognized by Prebish as a result of retiring the $1,000,000 of bonds in 2010 and prepare the journal entry to record the retirement.

(AICPA adapted)

Instructions

Prepare the journal entries necessary to record issue of the new bonds and the refunding of the bonds.

Instructions

Prepare journal entries to record the retirement of the old issue and the sale of the new issue on June 30, 2011.

Prepare the entry required on December 31, 2011, to record the payment of the first 6 months' interest and the amortization of premium on the bonds.

Instructions

Ignoring interest, compute the gain or loss and record this refunding transaction.

(AICPA adapted)

Purchases land having a fair market value of $300,000 by issuing a 5-year, zero-interest-bearing promissory note in the face amount of $505,518.

Purchases equipment by issuing a 6%, 8-year promissory note having a maturity value of $400,000 (interest payable annually).

The company has to pay 11% interest for funds from its bank.

Instructions

Record the two journal entries that should be recorded by McLean Company for the two purchases on January 1, 2011.

Record the interest at the end of the first year on both notes using the effective-interest method.

On January 1, 2011, Spartan Inc. purchased land that had an assessed value of $390,000 at the time of purchase. A $600,000, zero-interest-bearing note due January 1, 2014, was given in exchange. There was no established exchange price for the land, nor a ready market value for the note. The interest rate charged on a note of this type is 12%. Determine at what amount the land should be recorded at January 1, 2011, and the interest expense to be reported in 2011 related to this transaction.

On January 1, 2011, Geimer Furniture Co. borrowed $4,000,000 (face value) from Aurora Co., a major customer, through a zero-interest-bearing note due in 4 years. Because the note was zero-interest-bearing, Geimer Furniture agreed to sell furniture to this customer at lower than market price. A 10% rate of interest is normally charged on this type of loan. Prepare the journal entry to record this transaction and determine the amount of interest expense to report for 2011.

Instructions

Prepare the journal entry to record the initial transaction on January 1, 2010. (Round all computations to the nearest dollar.)

Prepare the journal entry to record any adjusting entries needed at December 31, 2010. Assume that the sales of Durdil's product to this customer occur evenly over the 3-year period.

Instructions

Prepare the required note disclosure for the long-term debt at December 31, 2010.

Instructions

Prepare journal entries for Strickland Company and Moran State Bank to record this debt settlement.

How should Strickland report the gain or loss on the disposition of machine and on restructuring of debt in its 2010 income statement?