After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

According to one study, revenue recognition has been the largest single source of public-company restatements over the past decade. The study noted the following:

Restatements for improper revenue recognition result in larger drops in market capitalization than any other type of restatement.

Revenue problems caused eight of the top ten market value losses in a recent year.

Of the ten companies, the leading three lost $20 billion in market value in just three days following disclosure of revenue recognition problems.[308]

As a result of such revenue recognition problems, the SEC has increased its enforcement actions in this area (as evidenced in the opening story). In some of these cases, companies made significant adjustments to previously issued financial statements. As Lynn Turner, a former chief accountant of the SEC, indicated, "When people cross over the boundaries of legitimate reporting, the Commission will take appropriate action to ensure the fairness and integrity that investors need and depend on every day."[309]

Inappropriate recognition of revenue can occur in any industry. Products that are sold to distributors for resale pose different risks than products or services that are sold directly to customers. Sales in high-technology industries, where rapid product obsolescence is a significant issue, pose different risks than sale of inventory with a longer life, such as farm or construction equipment, automobiles, trucks, and appliances.[310]

As indicated in Chapter 10, telecom companies such as Global Crossing and Qwest Communications swapped fiber-optic capacity to increase revenue. The SEC has expressed concern that dot-coms also are increasing their revenue by including product sales in their revenue even though they are acting only as the distributor (intermediary) on behalf of other companies. Instead, dot-coms should be reporting only a distribution (brokerage) fee for selling another company's products.[311]

Consider Priceline.com, the company made famous by William Shatner's ads about "naming your own price" for airline tickets and hotel rooms. In one of its quarterly SEC filings, Priceline reported that it earned $152 million in revenues. But that included the full amount customers paid for tickets, hotel rooms, and rental cars. Traditional travel agencies call that amount "gross bookings," not revenues. And much like regular travel agencies, Priceline keeps only a small portion of gross bookings—namely, the spread between the customers' accepted bids and the price it paid for the merchandise. The rest, which Priceline calls "product costs," it pays to the airlines and hotels that supply the tickets and rooms.

However, Priceline's product costs came to $134 million, leaving Priceline just $18 million of what it calls "gross profit" and what most other companies would call revenues. And that's before all of Priceline's other costs—like advertising and salaries—which netted out to a loss of $102 million. The difference isn't academic: Priceline stock traded at about 23 times its reported revenues but at a mind-boggling 214 times its "gross profit." This and other aggressive recognition practices led the SEC to issue stricter revenue recogniton guidance indicating that if a company performs as an agent or broker without assuming the risks and rewards of ownership of the goods, the company should report sales on a net (fee) basis. [1]

Source: Jeremy Kahn, "Presto Chango! Sales Are Huge," Fortune (March 20, 2000), p. 44.

In general, the guidelines for revenue recognition are quite broad. On top of the broad guidelines, certain industries have specific additional guidelines that provide further insight into when revenue should be recognized. The revenue recognition principle provides that companies should recognize revenue[312] (1) when it is realized or realizable and (2) when it is earned.[313] Therefore, proper revenue recognition revolves around three terms:

Revenues are realized when a company exchanges goods and services for cash or claims to cash (receivables).

Revenues are realizable when assets a company receives in exchange are readily convertible to known amounts of cash or claims to cash.

Revenues are earned when a company has substantially accomplished what it must do to be entitled to the benefits represented by the revenues—that is, when the earnings process is complete or virtually complete.[314]

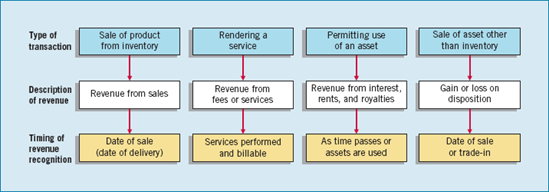

Four revenue transactions are recognized in accordance with this principle:

Companies recognize revenue from selling products at the date of sale. This date is usually interpreted to mean the date of delivery to customers.

Companies recognize revenue from services provided, when services have been performed and are billable.

Companies recognize revenue from permitting others to use enterprise assets, such as interest, rent, and royalties, as time passes or as the assets are used.

Companies recognize revenue from disposing of assets other than products at the date of sale.

These revenue transactions are diagrammed in Illustration 18-1.

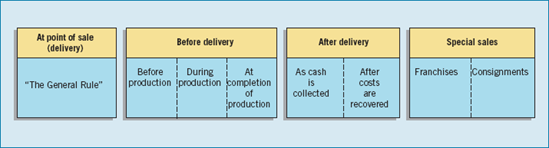

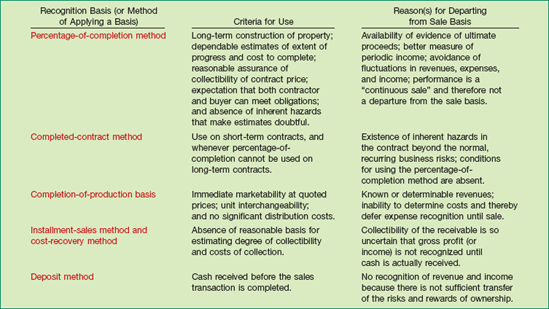

The preceding statements are the basis of accounting for revenue transactions. Yet, in practice there are departures from the revenue recognition principle. Companies sometimes recognize revenue at other points in the earning process, owing in great measure to the considerable variety of revenue transactions.[315]

An FASB study found some common reasons for departures from the sale basis.[316] One reason is a desire to recognize earlier than the time of sale the effect of earning activities. Earlier recognition is appropriate if there is a high degree of certainty about the amount of revenue earned. A second reason is a desire to delay recognition of revenue beyond the time of sale. Delayed recognition is appropriate if the degree of uncertainty concerning the amount of either revenue or costs is sufficiently high or if the sale does not represent substantial completion of the earnings process.

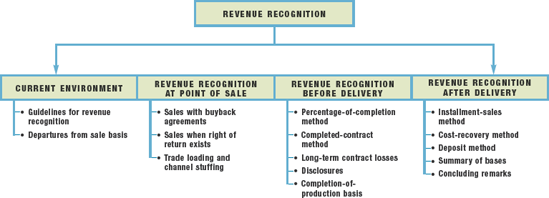

This chapter focuses on two of the four general types of revenue transactions described earlier: (1) selling products and (2) providing services. Both of these are sales transactions. (In several other sections of the textbook, we discuss the other two types of revenue transactions—revenue from permitting others to use enterprise assets, and revenue from disposing of assets other than products.) Our discussion of product sales transactions in this chapter is organized around the following topics:

Revenue recognition at point of sale (delivery).

Revenue recognition before delivery.

Revenue recognition after delivery.

Revenue recognition for special sales transactions—franchises and consignments.

Illustration 18-2 depicts this organization of revenue recognition topics.

According to the FASB's Concepts Statement No. 5, companies usually meet the two conditions for recognizing revenue (being realized or realizable and being earned) by the time they deliver products or render services to customers.[317] Therefore, companies commonly recognize revenues from manufacturing and selling activities at point of sale (usually meaning delivery).[318] Implementation problems, however, can arise. We discuss three such problematic situations on the following pages.

If a company sells a product in one period and agrees to buy it back in the next accounting period, has the company sold the product? As indicated in Chapter 8, legal title has transferred in this situation. However, the economic substance of the transaction is that the seller retains the risks of ownership. The FASB has curtailed recognition of revenue using this practice. When a repurchase agreement exists at a set price and this price covers all cost of the inventory plus related holding costs, the inventory and related liability remain on the seller's books. [3] In other words, no sale.

Whether cash or credit sales are involved, a special problem arises with claims for returns and allowances. In Chapter 7, we presented the accounting treatment for normal returns and allowances. However, certain companies experience such a high rate of returns—a high ratio of returned merchandise to sales—that they find it necessary to postpone reporting sales until the return privilege has substantially expired.

For example, in the publishing industry, the rate of return approaches 25 percent for hardcover books and 65 percent for some magazines. Other types of companies that experience high return rates are perishable food dealers, distributors who sell to retail outlets, recording-industry companies, and some toy and sporting goods manufacturers. Returns in these industries are frequently made either through a right of contract or as a matter of practice involving "guaranteed sales" agreements or consignments.

Three alternative revenue recognition methods are available when the right of return exposes the seller to continued risks of ownership. These are: (1) not recording a sale until all return privileges have expired; (2) recording the sale, but reducing sales by an estimate of future returns; and (3) recording the sale and accounting for the returns as they occur. The FASB concluded that if a company sells its product but gives the buyer the right to return it, the company should recognize revenue from the sales transactions at the time of sale only if all of the following six conditions have been met. [4]

The seller's price to the buyer is substantially fixed or determinable at the date of sale.

The buyer has paid the seller, or the buyer is obligated to pay the seller, and the obligation is not contingent on resale of the product.

The buyer's obligation to the seller would not be changed in the event of theft or physical destruction or damage of the product.

The buyer acquiring the product for resale has economic substance apart from that provided by the seller.

The seller does not have significant obligations for future performance to directly bring about resale of the product by the buyer.

The seller can reasonably estimate the amount of future returns.

What if the six conditions are not met? In that case, the company must recognize sales revenue and cost of sales either when the return privilege has substantially expired or when those six conditions subsequently are met, whichever occurs first. In the income statement, the company must reduce sales revenue and cost of sales by the amount of the estimated returns.

Some companies record revenues at date of delivery with neither buyback nor unlimited return provisions. Although they appear to be following acceptable point-of-sale revenue recognition practices, they are recognizing revenues and earnings prematurely.

For example, the domestic cigarette industry at one time engaged in a distribution practice known as trade loading. As one commentator described this practice, "Trade loading is a crazy, uneconomic, insidious practice through which manufacturers—trying to show sales, profits, and market share they don't actually have—induce their wholesale customers, known as the trade, to buy more product than they can promptly resell."[319] In total, the cigarette industry appears to have exaggerated a couple years' operating profits by as much as $600 million by taking the profits from future years.

In the computer software industry, a similar practice is referred to as channel stuffing. When a software maker needed to make its financial results look good, it offered deep discounts to its distributors to overbuy, and then recorded revenue when the software left the loading dock.[320] Of course, the distributors' inventories become bloated and the marketing channel gets too filled with product, but the software maker's current-period financials are improved. However, financial results in future periods will suffer, unless the company repeats the process.

Trade loading and channel stuffing distort operating results and "window dress" financial statements. If used without an appropriate allowance for sales returns, channel stuffing is a classic example of booking tomorrow's revenue today. Business managers need to be aware of the ethical dangers of misleading the financial community by engaging in such practices to improve their financial statements.

Investors in Lucent Technologies were negatively affected when Lucent violated one of the fundamental criteria for revenue recognition—the "no take-back" rule. This rule holds that revenue should not be booked on inventory that is shipped if the customer can return it at some point in the future. In this particular case, Lucent agreed to take back shipped inventory from its distributors, if the distributors were unable to sell the items to their customers.

In essence, Lucent was "stuffing the channel." By booking sales when goods were shipped, even though they most likely would get them back, Lucent was able to report continued sales growth. However, Lucent investors got a nasty surprise when distributors returned those goods and Lucent had to restate its financial results. The restatement erased $679 million in revenues, turning an operating profit into a loss. In response to this bad news, Lucent's stock price declined $1.31 per share, or 8.5 percent. Lucent is not alone in this practice. Sunbeam got caught stuffing the sales channel with barbeque grills and other outdoor items, which contributed to its troubles when it was forced to restate its earnings.

Investors can be tipped off to potential channel stuffing by carefully reviewing a company's revenue recognition policy for generous return policies and by watching inventory and receivable levels. When sales increase along with receivables, that's one sign that customers are not paying for goods shipped on credit. And growing inventory levels are an indicator that customers have all the goods they need. Both scenarios suggest a higher likelihood of goods being returned and revenues and income being restated. So remember, no take-backs!

Source: Adapted from S. Young, "Lucent Slashes First Quarter Outlook, Erases Revenue from Latest Quarter," Wall Street Journal Online (December 22, 2000); and Tracey Byrnes, "Too Many Thin Mints: Spotting the Practice of Channel Stuffing," Wall Street Journal Online (February 7, 2002).

For the most part, companies recognize revenue at the point of sale (delivery) because at point of sale most of the uncertainties in the earning process are removed and the exchange price is known. Under certain circumstances, however, companies recognize revenue prior to completion and delivery. The most notable example is long-term construction contract accounting, which uses the percentage-of-completion method.

Long-term contracts frequently provide that the seller (builder) may bill the purchaser at intervals, as it reaches various points in the project. Examples of long-term contracts are construction-type contracts, development of military and commercial aircraft, weapons-delivery systems, and space exploration hardware. When the project consists of separable units, such as a group of buildings or miles of roadway, contract provisions may provide for delivery in installments. In that case, the seller would bill the buyer and transfer title at stated stages of completion, such as the completion of each building unit or every 10 miles of road. The accounting records should record sales when installments are "delivered."[321]

Two distinctly different methods of accounting for long-term construction contracts are recognized.[322] They are:

Percentage-of-Completion Method. Companies recognize revenues and gross profits each period based upon the progress of the construction—that is, the percentage of completion. The company accumulates construction costs plus gross profit earned to date in an inventory account (Construction in Process), and it accumulates progress billings in a contra inventory account (Billings on Construction in Progress).

Completed-Contract Method. Companies recognize revenues and gross profit only when the contract is completed. The company accumulates construction costs in an inventory account (Construction in Process), and it accumulates progress billings in a contra inventory account (Billings on Construction in Process).

The rationale for using percentage-of-completion accounting is that under most of these contracts the buyer and seller have enforceable rights. The buyer has the legal right to require specific performance on the contract. The seller has the right to require progress payments that provide evidence of the buyer's ownership interest. As a result, a continuous sale occurs as the work progresses. Companies should recognize revenue according to that progression.

Companies must use the percentage-of-completion method when estimates of progress toward completion, revenues, and costs are reasonably dependable and all of the following conditions exist. [5]

The contract clearly specifies the enforceable rights regarding goods or services to be provided and received by the parties, the consideration to be exchanged, and the manner and terms of settlement.

The buyer can be expected to satisfy all obligations under the contract.

The contractor can be expected to perform the contractual obligations.

Companies should use the completed-contract method when one of the following conditions applies:

when a company has primarily short-term contracts, or

when a company cannot meet the conditions for using the percentage-of-completion method, or

when there are inherent hazards in the contract beyond the normal, recurring business risks.

The presumption is that percentage-of-completion is the better method. Therefore, companies should use the completed-contract method only when the percentage-of-completion method is inappropriate. We discuss the two methods in more detail in the following sections.

The percentage-of-completion method recognizes revenues, costs, and gross profit as a company makes progress toward completion on a long-term contract. To defer recognition of these items until completion of the entire contract is to misrepresent the efforts (costs) and accomplishments (revenues) of the accounting periods during the contract. In order to apply the percentage-of-completion method, a company must have some basis or standard for measuring the progress toward completion at particular interim dates.

As one practicing accountant wrote, "The big problem in applying the percentage-of-completion method ... has to do with the ability to make reasonably accurate estimates of completion and the final gross profit."[323] Companies use various methods to determine the extent of progress toward completion. The most common are the cost-to-cost and units-of-delivery methods.[324]

The objective of all these methods is to measure the extent of progress in terms of costs, units, or value added. Companies identify the various measures (costs incurred, labor hours worked, tons produced, floors completed, etc.) and classify them as input or output measures. Input measures (costs incurred, labor hours worked) are efforts devoted to a contract. Output measures (with units of delivery measured as tons produced, floors of a building completed, miles of a highway completed) track results. Neither are universally applicable to all long-term projects. Their use requires the exercise of judgment and careful tailoring to the circumstances.

Both input and output measures have certain disadvantages. The input measure is based on an established relationship between a unit of input and productivity. If inefficiencies cause the productivity relationship to change, inaccurate measurements result. Another potential problem is front-end loading, in which significant up-front costs result in higher estimates of completion. To avoid this problem, companies should disregard some early-stage construction costs—for example, costs of uninstalled materials or costs of subcontracts not yet performed—if they do not relate to contract performance.

Similarly, output measures can produce inaccurate results if the units used are not comparable in time, effort, or cost to complete. For example, using floors (stories) completed can be deceiving. Completing the first floor of an eight-story building may require more than one-eighth the total cost because of the substructure and foundation construction.

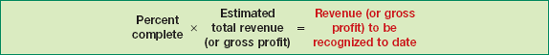

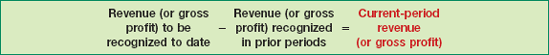

The most popular input measure used to determine the progress toward completion is the cost-to-cost basis. Under this basis, a company like EDS measures the percentage of completion by comparing costs incurred to date with the most recent estimate of the total costs required to complete the contract. Illustration 18-3 shows the formula for the cost-to-cost basis.

Once EDS knows the percentage that costs incurred bear to total estimated costs, it applies that percentage to the total revenue or the estimated total gross profit on the contract. The resulting amount is the revenue or the gross profit to be recognized to date. Illustration 18-4 shows this computation.

To find the amounts of revenue and gross profit recognized each period, EDS subtracts total revenue or gross profit recognized in prior periods, as shown in Illustration 18-5.

Because the cost-to-cost method is widely used (without excluding other bases for measuring progress toward completion), we have adopted it for use in our examples. [6]

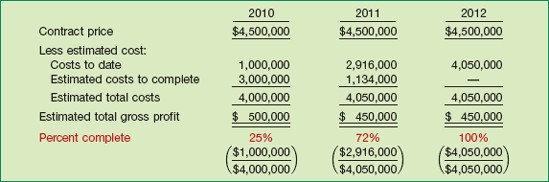

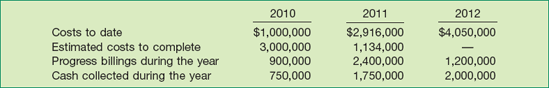

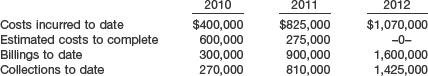

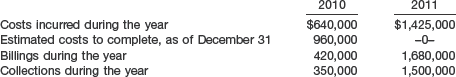

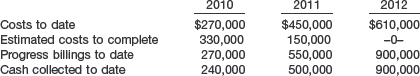

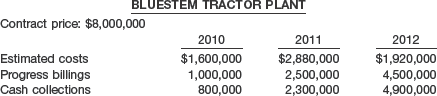

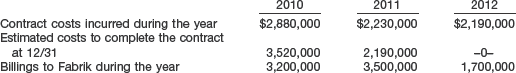

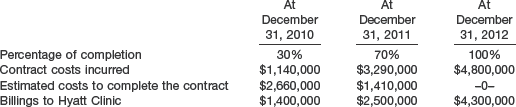

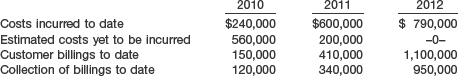

To illustrate the percentage-of-completion method, assume that Hardhat Construction Company has a contract to construct a $4,500,000 bridge at an estimated cost of $4,000,000. The contract is to start in July 2010, and the bridge is to be completed in October 2012. The following data pertain to the construction period. (Note that by the end of 2011 Hardhat has revised the estimated total cost from $4,000,000 to $4,050,000.)

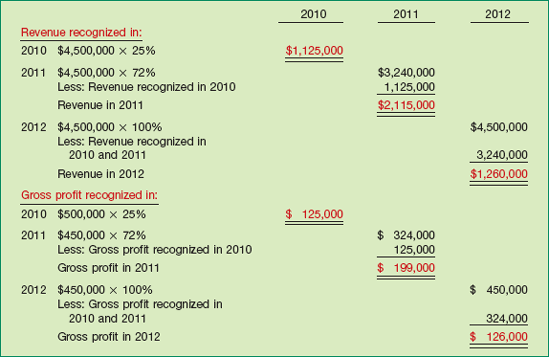

Hardhat would compute the percentage complete as shown in Illustration 18-6.

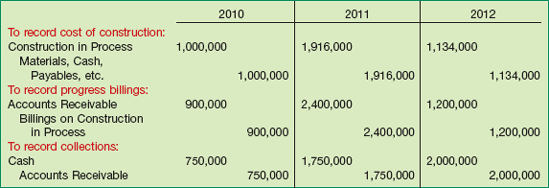

On the basis of the data above, Hardhat would make the following entries to record (1) the costs of construction, (2) progress billings, and (3) collections. These entries appear as summaries of the many transactions that would be entered individually as they occur during the year.

In this example, the costs incurred to date are a measure of the extent of progress toward completion. To determine this, Hardhat evaluates the costs incurred to date as a proportion of the estimated total costs to be incurred on the project. The estimated revenue and gross profit that Hardhat will recognize for each year are calculated as shown in Illustration 18-8 (on page 941).

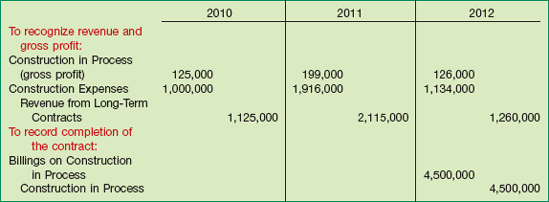

Illustration 18-9 shows Hardhat's entries to recognize revenue and gross profit each year and to record completion and final approval of the contract.

Figure 18-9. Journal Entries to Recognize Revenue and Gross Profit and to Record Contract Completion—Percentage-of-Completion Method, Cost-to-Cost Basis

Note that Hardhat debits gross profit (as computed in Illustration 18-8) to Construction in Process. Similarly, it credits Revenue from Long-Term Contracts for the amounts computed in Illustration 18-8. Hardhat then debits the difference between the amounts recognized each year for revenue and gross profit to a nominal account, Construction Expenses (similar to Cost of Goods Sold in a manufacturing company). It reports that amount in the income statement as the actual cost of construction incurred in that period. For example, Hardhat uses the actual costs of $1,000,000 to compute both the gross profit of $125,000 and the percent complete (25 percent).

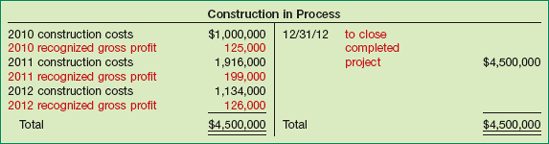

Hardhat continues to accumulate costs in the Construction in Process account, in order to maintain a record of total costs incurred (plus recognized profit) to date. Although theoretically a series of "sales" takes place using the percentage-of-completion method, the selling company cannot remove the inventory cost until the construction is completed and transferred to the new owner. Hardhat's Construction in Process account for the bridge would include the following summarized entries over the term of the construction project.

Recall that the Hardhat Construction Company example contained a change in estimate: In the second year, 2011, it increased the estimated total costs from $4,000,000 to $4,050,000. The change in estimate is accounted for in a cumulative catch-up manner. This is done by, first, adjusting the percent completed to the new estimate of total costs. Next, Hardhat deducts the amount of revenues and gross profit recognized in prior periods from revenues and gross profit computed for progress to date. That is, it accounts for the change in estimate in the period of change. That way, the balance sheet at the end of the period of change and the accounting in subsequent periods are as they would have been if the revised estimate had been the original estimate.

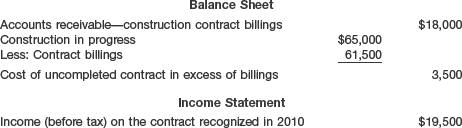

Generally, when a company records a receivable from a sale, it reduces the Inventory account. Under the percentage-of-completion method, however, the company continues to carry both the receivable and the inventory. Subtracting the balance in the Billings account from Construction in Process avoids double-counting the inventory. During the life of the contract, Hardhat reports in the balance sheet the difference between the Construction in Process and the Billings on Construction in Process accounts. If that amount is a debit, Hardhat reports it as a current asset; if it is a credit, it reports it as a current liability.

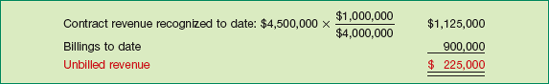

At times, the costs incurred plus the gross profit recognized to date (the balance in Construction in Process) exceed the billings. In that case, Hardhat reports this excess as a current asset entitled "Cost and recognized profit in excess of billings." Hardhat can at any time calculate the unbilled portion of revenue recognized to date by subtracting the billings to date from the revenue recognized to date, as illustrated for 2010 for Hardhat Construction in Illustration 18-11.

At other times, the billings exceed costs incurred and gross profit to date. In that case, Hardhat reports this excess as a current liability entitled "Billings in excess of costs and recognized profit."

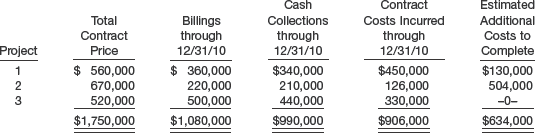

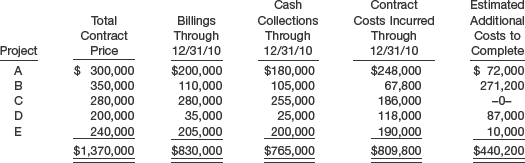

It probably has occurred to you that companies often have more than one project going at a time. When a company has a number of projects, costs exceed billings on some contracts and billings exceed costs on others. In such a case, the company segregates the contracts. The asset side includes only those contracts on which costs and recognized profit exceed billings. The liability side includes only those on which billings exceed costs and recognized profit. Separate disclosures of the dollar volume of billings and costs are preferable to a summary presentation of the net difference.

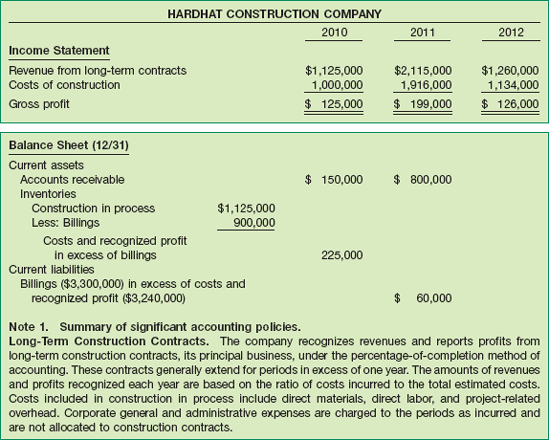

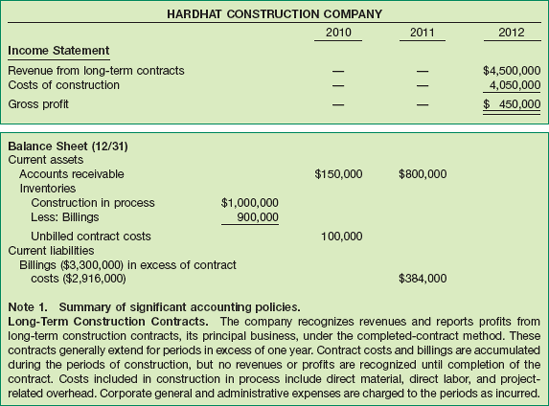

Using data from the bridge example, Hardhat Construction Company would report the status and results of its long-term construction activities under the perentage-of-completion method as shown in Illustration 18-12 (on page 943).

Under the completed-contract method, companies recognize revenue and gross profit only at point of sale—that is, when the contract is completed. Under this method, companies accumulate costs of long-term contracts in process, but they make no interim charges or credits to income statement accounts for revenues, costs, or gross profit.

The principal advantage of the completed-contract method is that reported revenue reflects final results rather than estimates of unperformed work. Its major disadvantage is that it does not reflect current performance when the period of a contract extends into more than one accounting period. Although operations may be fairly uniform during the period of the contract, the company will not report revenue until the year of completion, creating a distortion of earnings.

Under the completed-contract method, the company would make the same annual entries to record costs of construction, progress billings, and collections from customers as those illustrated under the percentage-of-completion method. The significant difference is that the company would not make entries to recognize revenue and gross profit.

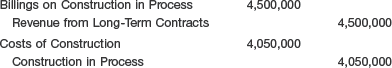

For example, under the completed-contract method for the bridge project illustrated on the preceding pages, Hardhat Construction Company would make the following entries in 2012 to recognize revenue and costs and to close out the inventory and billing accounts.

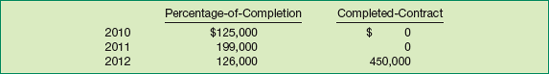

Illustration 18-13 compares the amount of gross profit that Hardhat Construction Company would recognize for the bridge project under the two revenue-recognition methods.

Under the completed-contract method, Hardhat Construction would report its long-term construction activities as follows.

Two types of losses can become evident under long-term contracts:[325]

Loss in the Current Period on a Profitable Contract. This condition arises when, during construction, there is a significant increase in the estimated total contract costs but the increase does not eliminate all profit on the contract. Under the percentage-of-completion method only, the estimated cost increase requires a current-period adjustment of excess gross profit recognized on the project in prior periods. The company records this adjustment as a loss in the current period because it is a change in accounting estimate (discussed in Chapter 22).

Loss on an Unprofitable Contract. Cost estimates at the end of the current period may indicate that a loss will result on completion of the entire contract. Under both the percentage-of-completion and the completed-contract methods, the company must recognize in the current period the entire expected contract loss.

The treatment described for unprofitable contracts is consistent with the accounting custom of anticipating foreseeable losses to avoid overstatement of current and future income (conservatism).

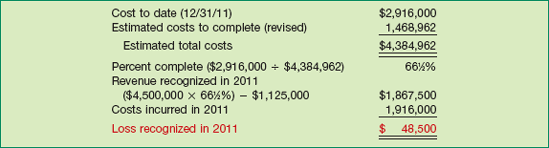

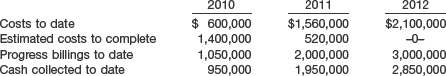

To illustrate a loss in the current period on a contract expected to be profitable upon completion, we'll continue with the Hardhat Construction Company bridge project. Assume that on December 31, 2011, Hardhat estimates the costs to complete the bridge contract at $1,468,962 instead of $1,134,000 (refer to page 940). Assuming all other data are the same as before, Hardhat would compute the percentage complete and recognize the loss as shown in Illustration 18-15. Compare these computations with those for 2011 in Illustration 18-6 (page 940). The "percent complete" has dropped, from 72 percent to 66½ percent, due to the increase in estimated future costs to complete the contract.

The 2011 loss of $48,500 is a cumulative adjustment of the "excessive" gross profit recognized on the contract in 2010. Instead of restating the prior period, the company absorbs the prior period misstatement entirely in the current period. In this illustration, the adjustment was large enough to result in recognition of a loss.

Hardhat Construction would record the loss in 2011 as follows.

Hardhat will report the loss of $48,500 on the 2011 income statement as the difference between the reported revenues of $1,867,500 and the costs of $1,916,000.[326] Under the completed-contract method, the company does not recognize a loss in 2011. Why not? Because the company still expects the contract to result in a profit, to be recognized in the year of completion.

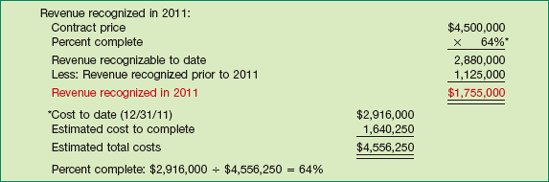

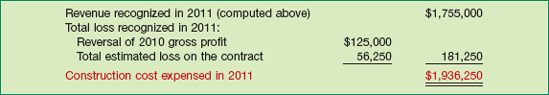

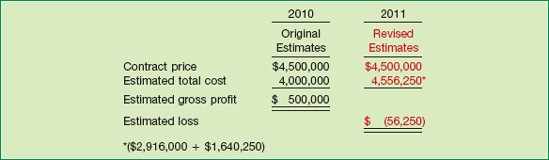

To illustrate the accounting for an overall loss on a long-term contract, assume that at December 31, 2011, Hardhat Construction Company estimates the costs to complete the bridge contract at $1,640,250 instead of $1,134,000. Revised estimates for the bridge contract are as follows.

Under the percentage-of-completion method, Hardhat recognized $125,000 of gross profit in 2010 (see Illustration 18-8 on page 941). This amount must be offset in 2011 because it is no longer expected to be realized. In addition, since losses must be recognized as soon as estimable, the company must recognize the total estimated loss of $56,250 in 2011. Therefore, Hardhat must recognize a total loss of $181,250 ($125,000 + $56,250) in 2011.

Illustration 18-16 shows Hardhat's computation of the revenue to be recognized in 2011.

To compute the construction costs to be expensed in 2011, Hardhat adds the total loss to be recognized in 2011 ($125,000 + $56,250) to the revenue to be recognized in 2011. Illustration 18-17 shows this computation.

Hardhat Construction would record the long-term contract revenues, expenses, and loss in 2011 as follows.

At the end of 2011, Construction in Process has a balance of $2,859,750 as shown below.[327]

Under the completed-contract method, Hardhat also would recognize the contract loss of $56,250, through the following entry in 2011 (the year in which the loss first became evident).

Just as the Billings account balance cannot exceed the contract price, neither can the balance in Construction in Process exceed the contract price. In circumstances where the Construction in Process balance exceeds the billings, the company can deduct the recognized loss from such accumulated costs on the balance sheet. That is, under both the percentage-of-completion and the completed-contract methods, the provision for the loss (the credit) may be combined with Construction in Process, thereby reducing the inventory balance. In those circumstances, however (as in the 2011 example above), where the billings exceed the accumulated costs, Hardhat must report separately on the balance sheet, as a current liability, the amount of the estimated loss. That is, under both the percentage-of-completion and the completed-contract methods, Hardhat would take the $56,250 loss, as estimated in 2011, from the Construction in Process account and report it separately as a current liability titled "Estimated liability from long-term contracts." [7]

Construction contractors usually make some unique financial statement disclosures in addition to those required of all businesses. Generally these additional disclosures are made in the notes to the financial statements. For example, a construction contractor should disclose the following: the method of recognizing revenue, [8] the basis used to classify assets and liabilities as current (the nature and length of the operating cycle), the basis for recording inventory, the effects of any revision of estimates, the amount of backlog on uncompleted contracts, and the details about receivables (billed and unbilled, maturity, interest rates, retainage provisions, and significant individual or group concentrations of credit risk).

Halliburton provides engineering- and construction-related services, in jobs around the world. Much of the company's work is completed under contract over long periods of time. The company uses percentage-of-completion accounting. The SEC started enforcement proceedings against the company related to its accounting for contract claims and disagreements with customers, including those arising from change orders and disputes about billable amounts and costs associated with a construction delay.

Prior to 1998, Halliburton took a very conservative approach to its accounting for disputed claims. As stated in the company's 1997 annual report, "Claims for additional compensation are recognized during the period such claims are resolved." That is, the company waited until all disputes were resolved before recognizing associated revenues. In contrast, in 1998 the company recognized revenue for disputed claims before their resolution, using estimates of amounts expected to be recovered. Such revenue and its related profit are more tentative and are subject to possible later adjustment than revenue and profit recognized when all claims have been resolved. As a case in point, the company noted that it incurred losses of $99 million in 1998 related to customer claims.

The accounting method put in place in 1998 is more aggressive than the company's former policy, but it is still within the boundaries of generally accepted accounting principles. However, the SEC noted that over six quarters, Halliburton failed to disclose its change in accounting practice. In the absence of any disclosure the SEC believed the investing public was misled about the precise nature of Halliburton's income in comparison to prior periods. The Halliburton situation illustrates the difficulty of using estimates in percentage-of-completion accounting and the impact of those estimates on the financial statements.

Source: "Failure to Disclose a 1998 Change in Accounting Practice," SEC (August 3, 2004), www.sec.gov/news/press/2004-104.htm. See also "Accounting Ace Charles Mulford Answers Accounting Questions," Wall Street Journal Online (June 7, 2002).

In certain cases companies recognize revenue at the completion of production even though no sale has been made. Examples of such situations involve precious metals or agricultural products with assured prices. Under the completion-of-production basis, companies recognize revenue when these metals are mined or agricultural crops harvested because the sales price is reasonably assured, the units are interchangeable, and no significant costs are involved in distributing the product.[328] (See discussion in Chapter 9, page 445, "Valuation at Net Realizable Value.")

Likewise, when sale or cash receipt precedes production and delivery, as in the case of magazine subscriptions, companies recognize revenues as earned by production and delivery.[329]

In some cases, the collection of the sales price is not reasonably assured and revenue recognition is deferred. One of two methods is generally employed to defer revenue recognition until the company receives cash: the installment-sales method or the cost-recovery method. A third method, the deposit method, applies in situations in which a company receives cash prior to delivery or transfer of the property; the company records that receipt as a deposit because the sale transaction is incomplete. This section examines these three methods.

The installment-sales method recognizes income in the periods of collection rather than in the period of sale. The logic underlying this method is that when there is no reasonable approach for estimating the degree of collectibility, companies should not recognize revenue until cash is collected.

The expression "installment sales" generally describes any type of sale for which payment is required in periodic installments over an extended period of time. All types of farm and home equipment as well as home furnishings are sold on an installment basis. The heavy equipment industry also sometimes uses the method for machine installations paid for over a long period. Another application of the method is in land-development sales.

Because payment is spread over a relatively long period, the risk of loss resulting from uncollectible accounts is greater in installment-sales transactions than in ordinary sales. Consequently, selling companies use various devices to protect themselves. Two common devices are: (1) the use of a conditional sales contract, which specifies that title to the item sold does not pass to the purchaser until all payments are made, and (2) use of notes secured by a chattel (personal property) mortgage on the article sold. Either of these permits the seller to "repossess" the goods sold if the purchaser defaults on one or more payments. The seller can then resell the repossessed merchandise at whatever price it will bring to compensate for the uncollected installments and the expense of repossession.

Under the installment-sales method of accounting, companies defer income recognition until the period of cash collection. They recognize both revenues and costs of sales in the period of sale, but defer the related gross profit to those periods in which they collect the cash. Thus, instead of deferring the sale, along with related costs and expenses, to the future periods of anticipated collection, the company defers only the proportional gross profit. This approach is equivalent to deferring both sales and cost of sales. Other expenses—that is, selling expense, administrative expense, and so on—are not deferred.

Thus, the installment-sales method matches cost and expenses against sales through the gross profit figure, but no further. Companies using the installment-sales method generally record operating expenses without regard to the fact that they will defer some portion of the year's gross profit. This practice is often justified on the basis that (1) these expenses do not follow sales as closely as does the cost of goods sold, and (2) accurate apportionment among periods would be so difficult that it could not be justified by the benefits gained.[330]

The use of the installment-sales method for revenue recognition has fluctuated widely. At one time it was widely accepted for installment-sales transactions. Somewhat paradoxically, as installment-sales transactions increased in popularity, acceptance and use of the installment-sales method decreased. Finally, the profession concluded that except in special circumstances, "the installment method of recognizing revenue is not acceptable." [9] The rationale for this position is simple: Because the installment method recognizes no income until cash is collected, it is not in accordance with the accrual accounting concept.

Use of the installment-sales method was often justified on the grounds that the risk of not collecting an account receivable may be so great that the sale itself is not sufficient evidence that recognition should occur. In some cases, this reasoning is valid, but not in a majority of cases. The general approach is that a company should recognize a completed sale. If the company expects bad debts, it should record this possibility as separate estimates of uncollectibles. Although collection expenses, repossession expenses, and bad debts are an unavoidable part of installment-sales activities, the incurrence of these costs and the collectibility of the receivables are reasonably predictable.

We study this topic in intermediate accounting because the method is acceptable in cases where a company believes there to be no reasonable basis of estimating the degree of collectibility. In addition, the sales method of revenue recognition has certain weaknesses when used for franchise and land-development operations. Application of the sales method to franchise and license operations has resulted in the abuse described earlier as "front-end loading." In some cases, franchisors recognized revenue prematurely, when they granted a franchise or issued a license, rather than when revenue was earned or the cash is received. Many land-development ventures were susceptible to the same abuses. As a result, the FASB prescribes application of the installment-sales method of accounting for sales of real estate under certain circumstances. [10][331]

One could work out a procedure that deferred both the uncollected portion of the sales price and the proportionate part of the cost of the goods sold. Instead of apportioning both sales price and cost over the period of collection, however, the installment-sales method defers only the gross profit. This procedure has exactly the same effect as deferring both sales and cost of sales, but it requires only one deferred account rather than two.

For the sales in any one year, the steps companies use to defer gross profit are as follows.

During the year, record both sales and cost of sales in the regular way, using the special accounts described later, and compute the rate of gross profit on installment-sales transactions.

At the end of the year, apply the rate of gross profit to the cash collections of the current year's installment sales, to arrive at the realized gross profit.

Defer to future years the gross profit not realized.

For sales made in prior years, companies apply the gross profit rate of each year's sales against cash collections of accounts receivable resulting from that year's sales, to arrive at the realized gross profit.

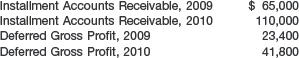

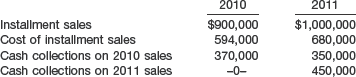

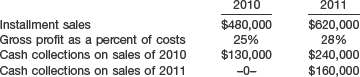

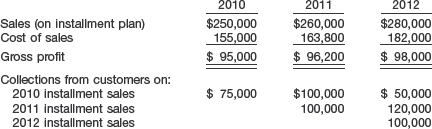

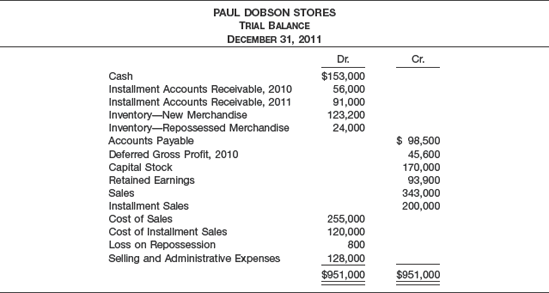

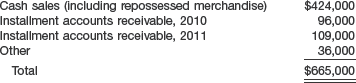

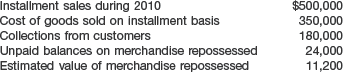

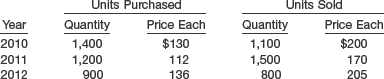

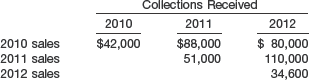

Special accounts must be used in the installment-sales method. These accounts provide certain special information required to determine the realized and unrealized gross profit in each year of operations. In computing net income under the installment-sales method as generally applied, the only peculiarity is the deferral of gross profit until realized by accounts receivable collection. We will use the following data to illustrate the installment-sales method in accounting for the sales of merchandise.

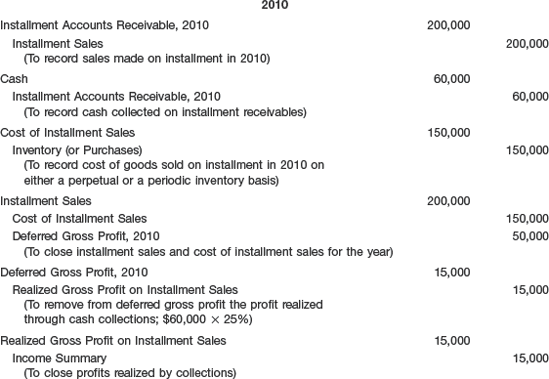

To simplify this example, we have excluded interest charges. Summary entries in general journal form for the year 2010 are as follows.

Illustration 18-19 shows computation of the realized and deferred gross profit for the year 2010.

Summary entries in journal form for year 2 (2011) are as follows.

Illustration 18-20 shows computation of the realized and deferred gross profit for the year 2011.

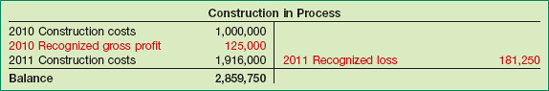

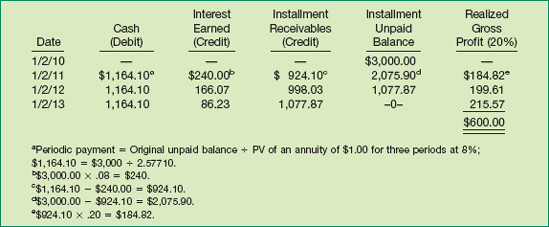

The entries in 2012 would be similar to those of 2011, and the total gross profit taken up or realized would be $64,000, as shown by the computations in Illustration 18-21.

In summary, here are the basic concepts you should understand about accounting for installment sales:

How to compute a proper gross profit percentage.

How to record installment sales, cost of installment sales, and deferred gross profit.

How to compute realized gross profit on installment receivables.

How the deferred gross profit balance at the end of the year results from applying the gross profit rate to the installment accounts receivable.

In addition to computing realized and deferred gross profit currently, other problems are involved in accounting for installment-sales transactions. These problems are related to:

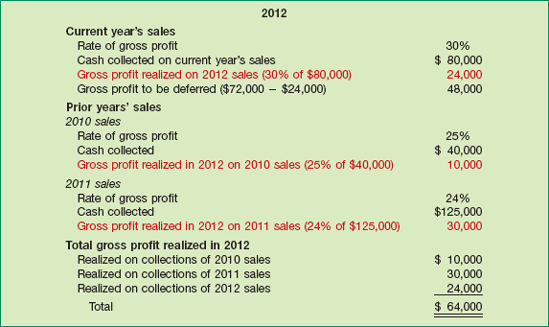

Interest on Installment Contracts. Because the collection of installment receivables is spread over a long period, it is customary to charge the buyer interest on the unpaid balance. The seller and buyer set up a schedule of equal payments consisting of interest and principal. Each successive payment is attributable to a smaller amount of interest and a correspondingly larger amount of principal, as shown in Illustration 18-22. This illustration assumes that a company sells for $3,000 an asset costing $2,400 (rate of gross profit = 20%), with interest of 8 percent included in the three installments of $1,164.10.

The company accounts for interest separate from the gross profit recognized on the installment-sales collections during the period, by recognizing interest revenue at the time of its cash receipt.

Uncollectible Accounts. The problem of bad debts or uncollectible accounts receivable is somewhat different for concerns selling on an installment basis because of a repossession feature commonly incorporated in the sales agreement. This feature gives the selling company an opportunity to recoup an uncollectible account through repossession and resale of repossessed merchandise. If the experience of the company indicates that repossessions do not, as a rule, compensate for uncollecible balances, it may be advisable to provide for such losses through charges to a special bad debt expense account, just as is done for other credit sales.

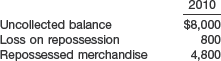

Defaults and Repossessions. Depending on the terms of the sales contract and the policy of the credit department, the seller can repossess merchandise sold under an installment arrangement if the purchaser fails to meet payment requirements. The seller may then recondition repossessed merchandise before offering it for re-sale, for cash or installment payments.

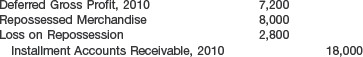

The accounting for repossessions recognizes that the company is not likely to collect the related installment receivable and should write it off. Along with the installment account receivable, the company must remove the applicable deferred gross profit using the following entry:

This entry assumes that the company will record the repossessed merchandise at exactly the amount of the uncollected account less the deferred gross profit applicable. This assumption may or may not be proper. To determine the correct amount, the company should consider the condition of the repossessed merchandise, the cost of reconditioning, and the market for second-hand merchandise of that particular type. The objective should be to put any asset acquired on the books at its fair value, or at the best possible approximation of fair value when fair value is not determinable. A loss can occur if the fair value of the repossessed merchandise is less than the uncollected balance less the deferred gross profit. In that case, the company should record a "loss on repossession" at the date of repossession.[332]

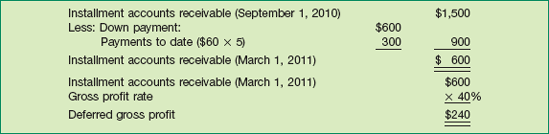

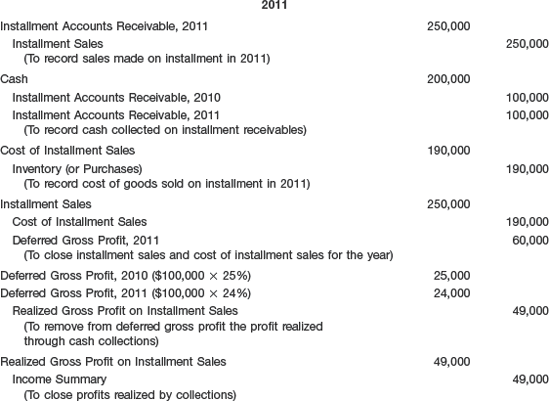

To illustrate the required entry, assume that Klein Brothers sells a refrigerator to Marilyn Hunt for $1,500 on September 1, 2010. Terms require a down payment of $600 and $60 on the first of every month for 15 months, starting October 1, 2010. It is further assumed that the refrigerator cost $900, and that Klein Brothers priced it to provide a 40 percent rate of gross profit on selling price. At the year-end, December 31, 2010, Klein Brothers should have collected a total of $180 in addition to the original down payment.

If Hunt makes her January and February payments in 2011 and then defaults, the account balances applicable to Hunt at time of default are as shown in Illustration 18-23.

As indicated, Klein Brothers compute the balance of deferred gross profit applicable to Hunt's account by applying the gross profit rate for the year of sale to the balance of Hunt's account receivable: 40 percent of $600, or $240. The account balances are therefore:

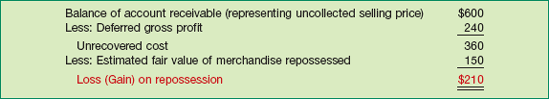

Klein repossesses the refrigerator following Hunt's default. If Klein sets the estimated fair value of the repossessed article at $150, it would make the following entry to record the repossession.

Klein determines the amount of the loss in two steps: (1) It subtracts the deferred gross profit from the amount of the account receivable, to determine the unrecovered cost (or book value) of the merchandise repossessed. (2) It then subtracts the estimated fair value of the merchandise repossessed from the unrecovered cost, to get the amount of the loss on repossession. Klein Brothers computes the loss on the refrigerator as shown in Illustration 18-24.

As pointed out earlier, the loss on repossession may be charged to Allowance for Doubtful Accounts if a company carries such an account.

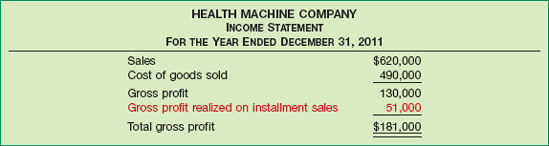

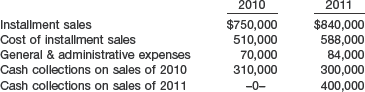

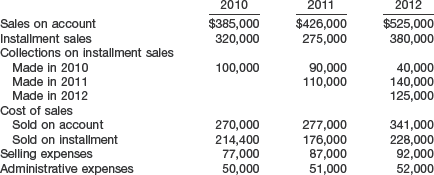

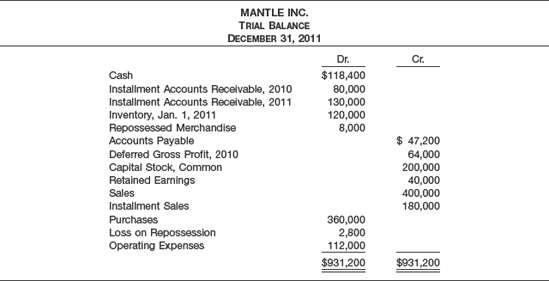

If installment-sales transactions represent a significant part of total sales, it is desirable to make full disclosure of installment sales, the cost of installment sales, and any expenses allocable to installment sales. However, if installment-sales transactions constitute an insignificant part of total sales, it may be satisfactory to include only the realized gross profit in the income statement as a special item following the gross profit on sales. Illustration 18-25 shows this simpler presentation.

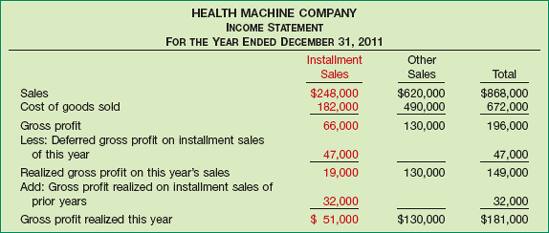

If a company wants more complete disclosure of installment-sales transactions, it would use a presentation similar to that shown in Illustration 18-26.

The presentation in Illustration 18-26 is awkward. Yet the awkwardness of this method is difficult to avoid if a company wants to provide full disclosure of installment-sales transactions in the income statement. One solution, of course, is to prepare a separate schedule showing installment-sales transactions, with only the final figure carried into the income statement.

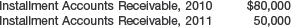

In the balance sheet it is generally considered desirable to classify installment accounts receivable by year of collectibility. There is some question as to whether companies should include in current assets installment accounts that are not collectible for two or more years. Yet if installment sales are part of normal operations, companies may consider them as current assets because they are collectible within the operating cycle of the business. Little confusion should result from this practice if the company fully discloses maturity dates, as illustrated in the following example.

On the other hand, a company may have receivables from an installment contract, resulting from a transaction not related to normal operations. In that case, the company should report such receivable in the "Other assets" section if due beyond one year.

Repossessed merchandise is a part of inventory, and companies should report it as such in the "Current assets" section of the balance sheet. They should include any gain or loss on repossession in the income statement in the "Other revenues and gains" or "Other expenses and losses" section.

If a company has deferred gross profit on installment sales, it generally treats it as unearned revenue and classifies it as a current liability. Theoretically, deferred gross profit consists of three elements: (1) income tax liability to be paid when the sales are reported as realized revenue (current liability); (2) allowance for collection expense, bad debts, and repossession losses (deduction from installment accounts receivable); and (3) net income (retained earnings, restricted as to dividend availability). Because of the difficulty in allocating deferred gross profit among these three elements, however, companies frequently report the whole amount as unearned revenue.

In contrast, the FASB in SFAC No. 6 states that "no matter how it is displayed in financial statements, deferred gross profit on installment sales is conceptually an asset valuation—that is, a reduction of an asset."[333] We support the FASB position, but we recognize that until an official standard on this topic is issued, financial statements will probably continue to report such deferred gross profit as a current liability.

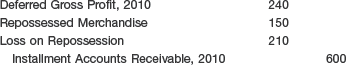

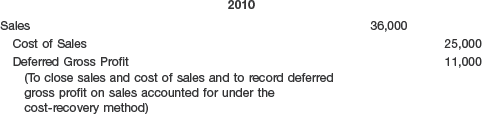

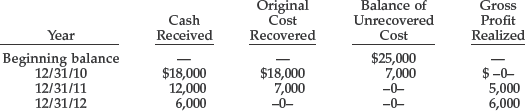

Under the cost-recovery method, a company recognizes no profit until cash payments by the buyer exceed the cost of the merchandise sold. After the seller has recovered all costs, it includes in income any additional cash collections. The seller's income statement for the period reports sales revenue, the cost of goods sold, and the gross profit—both the amount (if any) that is recognized during the period and the amount that is deferred. The deferred gross profit is offset against the related receivable—reduced by collections—on the balance sheet. Subsequent income statements report the gross profit as a separate item of revenue when the company recognizes it as earned.

A seller is permitted to use the cost-recovery method to account for sales in which "there is no reasonable basis for estimating collectibility." In addition, use of this method is required where a high degree of uncertainty exists related to the collection of receivables. [11], [12], [13]

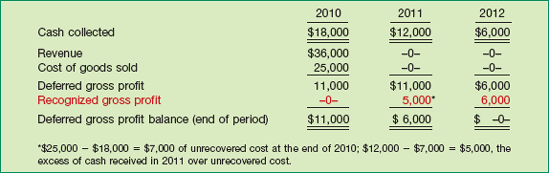

To illustrate the cost-recovery method, assume that early in 2010, Fesmire Manufacturing sells inventory with a cost of $25,000 to Higley Company for $36,000. Higley will make payments of $18,000 in 2010, $12,000 in 2011, and $6,000 in 2012. If the cost-recovery method applies to this transaction and Higley makes the payments as scheduled, Fesmire recognizes cash collections, revenue, cost, and gross profit as follows.[334]

Under the cost-recovery method, Fesmire reports total revenue and cost of goods sold in the period of sale, similar to the installment-sales method. However, unlike the installment-sales method, which recognizes income as cash is collected, Fesmire recognizes profit under the cost-recovery method only when cash collections exceed the total cost of the goods sold.

Therefore, Fesmire's journal entry to record the deferred gross profit on the Higley sale transaction (after recording the sale and the cost of sale in the normal manner) at the end of 2010 is as follows.

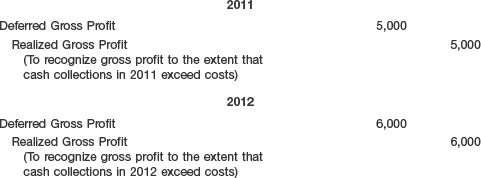

In 2011 and 2012, the deferred gross profit becomes realized gross profit as the cumulative cash collections exceed the total costs, by recording the following entries.

Suppose you purchased a gift card for spa services at Sundara Spa for $300. The gift card expires at the end of six months. When should Sundara record the revenue? Here are two choices:

At the time Sundara receives the cash for the gift card.

At the time Sundara provides the service to the gift-card holder.

If you answered number 2, you would be right. Companies should recognize revenue when the obligation is satisfied—which is when Sundara performs the service.

Now let's add a few more facts. Suppose that the gift-card holder fails to use the card in the six-month period. Statistics show that between 2 and 15 percent of gift-card holders never redeem their cards. So, do you still believe that Sundara should record the revenue at the expiration date?

If you say you are not sure, you are probably right. Here is why: Certain states (such as California) do not recognize expiration dates, and therefore the customer has the right to redeem an otherwise expired gift card at any time. Let's for the moment say we are in California. Because the card holder may never redeem, when can Sundara recognize the revenue? In that case Sundara would have to show statistically that after a certain period of time, the likelihood of redemption is remote. If it can make that case, it can recognize the revenue. Otherwise it may have to wait a long time.

Unfortunately Sundara may still have a problem. It may be required to turn over the value of the spa service to the state. The treatment for unclaimed gift cards may fall under the state abandoned-and-unclaimed-property laws. Most common unclaimed items are required to be remitted to the states after a five-year period. Failure to report and remit the property can result in additional fines and penalties. So if Sundara is in a state where unclaimed property must be sent to the state, Sundara should report a liability on its balance sheet.

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers, "Issues Surrounding the Recognition of Gift Card Sales and Escheat Liabilities," Quick Brief (December 2004).

In some cases, a company receives cash from the buyer before it transfers the goods or property. In such cases the seller has not performed under the contract and has no claim against the purchaser. There is not sufficient transfer of the risks and rewards of ownership for a sale to be recorded. The method of accounting for these incomplete transactions is the deposit method.

Under the deposit method the seller reports the cash received from the buyer as a deposit on the contract and classifies it on the balance sheet as a liability (refundable deposit or customer advance). The seller continues to report the property as an asset on its balance sheet, along with any related existing debt. Also, the seller continues to charge depreciation expense as a period cost for the property. The seller does not recognize revenue or income until the sale is complete. [14] At that time, it closes the deposit account and applies one of the revenue recognition methods discussed in this chapter to the sale.

The major difference between the installment-sales and cost-recovery methods and the deposit method relates to contract performance. In the installment-sales and cost-recovery methods it is assumed that the seller has performed on the contract, but cash collection is highly uncertain. In the deposit method, the seller has not performed and no legitimate claim exists. The deposit method postpones recognizing a sale until the company determines that a sale has occurred for accounting purposes. If there has not been sufficient transfer of risks and rewards of ownership, even if the selling company has received a deposit, the company postpones recognition of the sale until sufficient transfer has occurred. In that sense, the deposit method is not a revenue recognition method as are the installment-sales and cost-recovery methods.

Illustration 18-29 summarizes the revenue-recognition bases or methods, the criteria for their use, and the reasons for departing from the sale basis.[335]

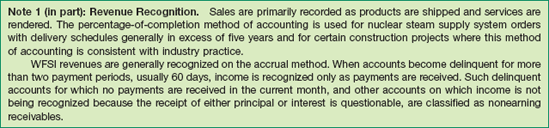

As indicated, revenue recognition principles are sometimes difficult to apply and often vary by industry. Recently, the SEC has attempted to provide more guidance in this area because of concern that the revenue recognition principle is sometimes being incorrectly applied. Many cases of intentional misstatement of revenue to achieve better financial results have recently come to light. Such practices are fraudulent, and the SEC is vigorously prosecuting these situations.

For our capital markets to be efficient, investors must have confidence that the financial information provided is both relevant and reliable. As a result, it is imperative that the accounting profession, regulators, and companies eliminate aggressive revenue recognition practices. It is our hope that recent efforts by the SEC and the accounting profession will lead to higher-quality reporting in this area.

The general concepts and principles used for revenue recognition are similar between U.S. GAAP and international GAAP (iGAAP). Where they differ is in the detail. As indicated in the chapter, U.S. GAAP provides specific guidance related to revenue recognition for many different industries. That is not the case for iGAAP. Also the SEC has issued broad and specific guidance for public companies in the United States related to revenue recognition. Again, the IASB does not have a regulatory body that provides additional guidance.

The IASB defines revenue to include both revenues and gains. U.S. GAAP provides separate definitions for revenues and gains.

Revenue recognition fraud is a major issue in U.S. financial reporting. The same situation occurs overseas as evidenced by revenue recognition breakdowns at Dutch software company Baan NV, Japanese electronics giant NEC, and Dutch grocer AHold NV.

A specific standard exists for revenue recognition under iGAAP (IAS 18). In general, the standard is based on the probability that the economic benefits associated with the transaction will flow to the company selling the goods, rendering the service, or receiving investment income. In addition, the revenues and costs must be capable of being measured reliably. U.S. GAAP uses concepts such as realized, realizable, and earned as a basis for revenue recognition.

iGAAP prohibits the use of the completed-contract method of accounting for long-term construction contracts (IAS 13). Companies must use the percentage-of-completion method. If revenues and costs are difficult to estimate, then companies recognize revenue only to the extent of the cost incurred—a zero-profit approach.

In long-term construction contracts, iGAAP requires recognition of a loss immediately if the overall contract is going to be unprofitable. In other words, U.S. GAAP and iGAAP are the same regarding this issue.

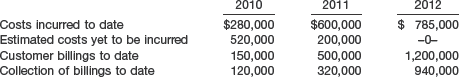

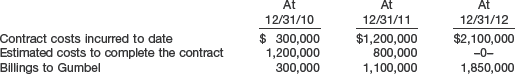

As mentioned, iGAAP does not permit the completed-contract method of accounting for long-term construction contracts. If costs or revenues cannot be reliably determined, then how does a company report revenues related to its construction contracts using iGAAP? To illustrate, assume the following facts for England Construction Co. for a contract to build a dam at Windswept Canyon.

The contract price to construct the dam is $400 million.

Estimated incurred costs are $54 million in 2010, $180 million in 2011, and $126 million in 2012.

England uses iGAAP but is uncertain as regards these cost numbers.

In this situation, England recognizes revenue up to the cost incurred until the cost numbers can be more reliably determined. For example, assume that England incurred $55 million in costs in 2010. The presentation on its income statement would be as follows.

Under iGAAP, zero profit is recognized. Once costs can be reliably determined, the percentage-of-completion method is used in future periods.

The FASB and IASB are now involved in a joint project on revenue recognition. The objective of the project is to develop coherent conceptual guidance for revenue recognition and a comprehensive statement on revenue recognition based on those concepts. In particular, the project is intended to improve financial reporting by (1) converging U.S. and international standards on revenue recognition, (2) eliminating inconsistencies in the existing conceptual guidance on revenue recognition, (3) providing conceptual guidance that would be useful in addressing future revenue recognition issues, (4) eliminating inconsistencies in existing standards-level authoritative literature and accepted practices, (5) filling voids in revenue recognition guidance that have developed over time, and (6) establishing a single, comprehensive standard on revenue recognition. Presently, the Boards are evaluating a "customer-consideration" model. It is hoped that this approach (rather than using the earned and realized or realized criteria) will lead to a better basis for revenue recognition. For more on this topic, see http://www.fasb.org/project/revenue_recognition.shtml.

To supplement our presentation of revenue recognition, in this appendix we cover two common yet unique types of business transactions—franchises and consignments.

As indicated throughout this chapter, companies recognize revenue on the basis of two criteria: (1) when it is realized or realizable (occurrence of an exchange for cash or claims to cash), and (2) when it is earned (completion or virtual completion of the earnings process). These criteria are appropriate for most business activities. For some sales transactions, though, they do not adequately define when a company should recognize revenue. The fast-growing franchise industry is of special concern and challenge.

In accounting for franchise sales, a company must analyze the transaction and, considering all the circumstances, use judgment in selecting one or more of the revenue recognition bases, and then possibly must monitor the situation over a long period of time.

Four types of franchising arrangements have evolved: (1) manufacturer-retailer, (2) manufacturer-wholesaler, (3) service sponsor-retailer, and (4) wholesaler-retailer. The fastest-growing category of franchising, and the one that caused a reexamination of appropriate accounting, has been the third category, service sponsor-retailer. Included in this category are such industries and businesses as:

Franchise companies derive their revenue from one or both of two sources: (1) from the sale of initial franchises and related assets or services, and (2) from continuing fees based on the operations of franchises. The franchisor (the party who grants business rights under the franchise) normally provides the franchisee (the party who operates the franchised business) with the following services.

Assistance in site selection: (a) analyzing location and (b) negotiating lease.

Evaluation of potential income.

Supervision of construction activity: (a) obtaining financing, (b) designing building, and (c) supervising contractor while building.

Assistance in the acquisition of signs, fixtures, and equipment.

Bookkeeping and advisory services: (a) setting up franchisee's records; (b) advising on income, real estate, and other taxes; and (c) advising on local regulations of the franchisee's business.

Quality control.

Advertising and promotion.[336]

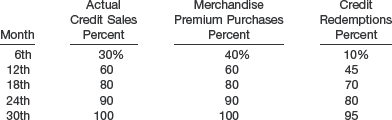

In the past, it was standard practice for franchisors to recognize the entire franchise fee at the date of sale, whether the fee was received then or was collectible over a long period of time. Frequently, franchisors recorded the entire amount as revenue in the year of sale, even though many of the services were yet to be performed and uncertainty existed regarding the collection of the entire fee.[337] (In effect, the franchisors were counting their fried chickens before they were hatched.) However, a franchise agreement may provide for refunds to the franchisee if certain conditions are not met, and franchise fee profit can be reduced sharply by future costs of obligations and services to be rendered by the franchisor. To curb the abuses in revenue recognition that existed and to standardize the accounting and reporting practices in the franchise industry, the FASB issued rules which form the basis for the accounting discussed below.

The initial franchise fee is payment for establishing the franchise relationship and providing some initial services. Franchisors record initial franchise fees as revenue only when and as they make "substantial performance" of the services they are obligated to perform and when collection of the fee is reasonably assured. Substantial performance occurs when the franchisor has no remaining obligation to refund any cash received or excuse any nonpayment of a note and has performed all the initial services required under the contract. Commencement of operations by the franchisee shall be presumed to be the earliest point at which substantial performance has occurred, unless it can be demonstrated that substantial performance of all obligations, including services rendered voluntarily, has occurred before that time. [15]

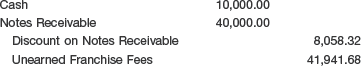

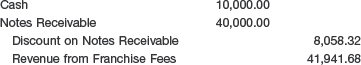

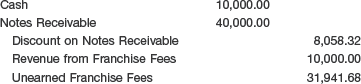

To illustrate, assume that Tum's Pizza Inc. charges an initial franchise fee of $50,000 for the right to operate as a franchisee of Tum's Pizza. Of this amount, $10,000 is payable when the franchisee signs the agreement, and the balance is payable in five annual payments of $8,000 each. In return for the initial franchise fee, Tum's will help locate the site, negotiate the lease or purchase of the site, supervise the construction activity, and provide the bookkeeping services. The credit rating of the franchisee indicates that money can be borrowed at 8 percent. The present value of an ordinary annuity of five annual receipts of $8,000 each discounted at 8 percent is $31,941.68. The discount of $8,058.32 represents the interest revenue to be accrued by the franchisor over the payment period. The following examples show the entries that Tum's Pizza Inc. would make under various conditions.

If there is reasonable expectation that Tum's Pizza Inc. may refund the down payment and if substantial future services remain to be performed by Tum's Pizza Inc., the entry should be:

If the probability of refunding the initial franchise fee is extremely low, the amount of future services to be provided to the franchisee is minimal, collectibility of the note is reasonably assured, and substantial performance has occurred, the entry should be:

If the initial down payment is not refundable, represents a fair measure of the services already provided, with a significant amount of services still to be performed by Tum's Pizza in future periods, and collectibility of the note is reasonably assured, the entry should be:

If the initial down payment is not refundable and no future services are required by the franchisor, but collection of the note is so uncertain that recognition of the note as an asset is unwarranted, the entry should be:

Under the same conditions as those listed in case 4 above, except that the down payment is refundable or substantial services are yet to be performed, the entry should be:

In cases 4 and 5—where collection of the note is extremely uncertain—franchisors may recognize cash collections using the installment-sales method or the cost-recovery method.[338]

Continuing franchise fees are received in return for the continuing rights granted by the franchise agreement and for providing such services as management training, advertising and promotion, legal assistance, and other support. Franchisors report continuing fees as revenue when they are earned and receivable from the franchisee, unless a portion of them has been designated for a particular purpose, such as providing a specified amount for building maintenance or local advertising. In that case, the portion deferred shall be an amount sufficient to cover the estimated cost in excess of continuing franchise fees and provide a reasonable profit on the continuing services.

In addition to paying continuing franchise fees, franchisees frequently purchase some or all of their equipment and supplies from the franchisor. The franchisor would account for these sales as it would for any other product sales.

Sometimes, however, the franchise agreement grants the franchisee the right to make bargain purchases of equipment or supplies after the franchisee has paid the initial franchise fee. If the bargain price is lower than the normal selling price of the same product, or if it does not provide the franchisor a reasonable profit, then the franchisor should defer a portion of the initial franchise fee. The franchisor would account for the deferred portion as an adjustment of the selling price when the franchisee subsequently purchases the equipment or supplies.

A franchise agreement may give the franchisor an option to purchase the franchisee's business. As a matter of management policy, the franchisor may reserve the right to purchase a profitable franchise outlet, or to purchase one that is in financial difficulty.

If it is probable at the time the option is given that the franchisor will ultimately purchase the outlet, then the franchisor should not recognize the initial franchise fee as revenue but should instead record it as a liability. When the franchisor exercises the option, the liability would reduce the franchisor's investment in the outlet.

Franchise accounting also involves proper accounting for the franchisor's cost. The objective is to match related costs and revenues by reporting them as components of income in the same accounting period. Franchisors should ordinarily defer direct costs (usually incremental costs) relating to specific franchise sales for which revenue has not yet been recognized. They should not, however, defer costs without reference to anticipated revenue and its realizability. [16] Indirect costs of a regular and recurring nature, such as selling and administrative expenses that are incurred irrespective of the level of franchise sales, should be expensed as incurred.

Franchisors must disclose all significant commitments and obligations resulting from franchise agreements, including a description of services that have not yet been substantially performed. They also should disclose any resolution of uncertainties regarding the collectibility of franchise fees. Franchisors segregate initial franchise fees from other franchise fee revenue if they are significant. Where possible, revenues and costs related to franchisor-owned outlets should be distinguished from those related to franchised outlets.

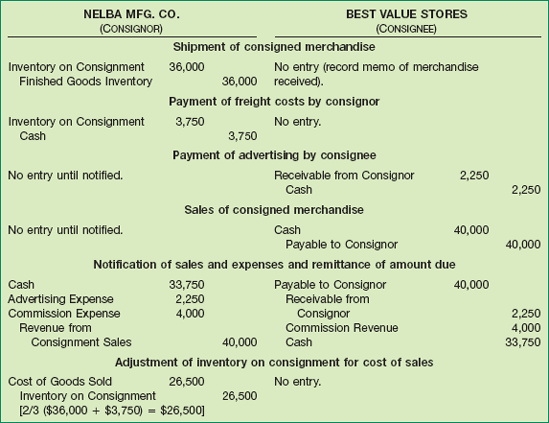

In some cases, manufacturers (or wholesalers) deliver goods but retain title to the goods until they are sold. This specialized method of marketing certain types of products makes use of a device known as a consignment. Under this arrangement, the consignor (manufacturer or wholesaler) ships merchandise to the consignee (dealer), who is to act as an agent for the consignor in selling the merchandise. Both consignor and consignee are interested in selling—the former to make a profit or develop a market, the latter to make a commission on the sale.

The consignee accepts the merchandise and agrees to exercise due diligence in caring for and selling it. The consignee remits to the consignor cash received from customers, after deducting a sales commission and any chargeable expenses.

In consignment sales, the consignor uses a modified version of the sale basis of revenue recognition. That is, the consignor recognizes revenue only after receiving notification of sale and the cash remittance from the consignee. The consignor carries the merchandise as inventory throughout the consignment, separately classified as Merchandise on Consignment. The consignee does not record the merchandise as an asset on its books. Upon sale of the merchandise, the consignee has a liability for the net amount due the consignor. The consignor periodically receives from the consignee a report called account sales that shows the merchandise received, merchandise sold, expenses chargeable to the consignment, and the cash remitted. Revenue is then recognized by the consignor.

To illustrate consignment accounting entries, assume that Nelba Manufacturing Co. ships merchandise costing $36,000 on consignment to Best Value Stores. Nelba pays $3,750 of freight costs, and Best Value pays $2,250 for local advertising costs that are reimbursable from Nelba. By the end of the period, Best Value has sold two-thirds of the consigned merchandise for $40,000 cash. Best Value notifies Nelba of the sales, retains a 10 percent commission, and remits the cash due Nelba. Illustration 18A-1 (on page 966) shows the journal entries of the consignor (Nelba) and the consignee (Best Value).

Under the consignment arrangement, the consignor accepts the risk that the merchandise might not sell and relieves the consignee of the need to commit part of its working capital to inventory. Companies use a variety of different systems and account titles to record consignments, but they all share the common goal of postponing the recognition of revenue until it is known that a sale to a third party has occurred.

SUMMARY OF LEARNING OBJECTIVE FOR APPENDIX 18A

FASB Codification References

FASB ASC 605-10-S99-1. [Predecessor literature: "Revenue Recognition in Financial Statements," SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 101 (December 3, 1999), and "Revenue Recognition," SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 104 (December 17, 2003).]

FASB ASC 605-10-S99-1. [Predecessor literature: "Revenue Recognition in Financial Statements," SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 101 December 3, 1999), and "Revenue Recognition," SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 104 (December 17, 2003).]

FASB ASC 470-40-25. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Product Financing Arrangements," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 49 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1981).]

FASB ASC 605-15-25-1. [Predecessor literature: "Revenue Recognition When Right of Return Exists," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 48 (Stamford, Conn.: FASB, 1981), par. 6.]

FASB ASC 605-35-25-57. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Performance of Construction-Type and Certain Production-Type Contracts," Statement of Position 81-1 (New York: AICPA, 1981), par. 23.]

FASB ASC 605-35-05-7. [Predecessor literature: Committee on Accounting Procedure, "Long-Term Construction-Type Contracts," Accounting Research Bulletin No. 45 (New York: AICPA, 1955), p. 7.]

FASB ASC 910-405. [Predecessor literature: Construction Contractors, Audit and Accounting Guide (New York: AICPA, 1981), pp. 148–149.]

FASB ASC 910-605-50-1. [Predecessor literature: Construction Contractors, Audit and Accounting Guide (New York: AICPA, 1981), p. 30.]

FASB ASC 605-10-25-3. [Predecessor literature: "Omnibus Opinion," Opinions of the Accounting Principles Board No. 10 (New York: AICPA, 1966), par. 12.]