ACTIVITY 18

Look Beyond Appearances

“We need to give each other the space to grow, to be ourselves, to exercise our diversity. We need to give each other space so that we may both give and receive such beautiful things as ideas, openness, dignity, joy, healing, and inclusion.”

—Max De Pree

***

Appearances can be deceiving as we tend to make decisions and judgments based on very limited information. Visual observations provide only surface details, often by design. Men may wear caps to cover baldness; women may wear high heels to appear taller. When we notice someone pulling into an accessible parking space, hopping out, and running into the store, seemingly obvious that they are not disabled, we judge them for it. We conclude that they are lazy or inconsiderate, and we may even become angry that they have robbed the spot from someone who actually needs it. Our reaction may be to just shake our heads in disbelief and continue about our business, or our sense of morals may compel us to throw them a disapproving look or even say something to let them know that they have been caught. We want them to know that they are not “pulling the wool over our eyes!”

Not all disabilities are visible. According to Accessibility.com, about 25 percent of adults in the United States have a disability, and most invisible disability metrics in the United States say that the number could be as high as 20 percent or more for Americans with an invisible disability. That said, there is a high likelihood that we have co-workers with invisible disabilities. There are no outward signs of injury, ailment, or impairment, nor do they use assistive devices such as a cane or wheelchair. From our vantage point, they have no medical issues whatsoever. When we encounter someone experiencing severe migraines, asthma, or sickle cell anemia, for example, we are prone to judge them when their health challenges lead to absenteeism, missed deadlines, or the belief that they are not doing their fair share of the work. A person with an invisible disability may seem perfectly healthy yet live with many challenges. Their battle with extreme fatigue or cognitive impairments may go unnoticed, deceiving us into believing that all is well. We are oblivious to incapacitating pain, dizziness, or weakness, which periodically or constantly prevents them from functioning as well as everyone else. Further, our disbelief heightens when we encounter young people experiencing ailments that we associate with aging, like rheumatoid arthritis or chronic back pain. Meet 22-year-old Darryl. He's been a sales associate at a locally owned bookstore for six months. In addition to working with customers, the nature of the work requires accepting and inspecting shipments, conducting and managing inventory, maintaining store cleanliness, and participating in seasonal refreshes of the store signage and displays. Darryl is hard working, is attentive to the needs of customers, and gets along well with co-workers. By all accounts, Darryl is the model employee. As the Christmas season approached, it was time to do a major refresh to include retrieving stored items, assembling and hanging decorations, and moving furniture. The team of four was working late to start the process. Everybody had a job to do. Darryl, who stood 6 feet 2 inches and weighed about 225 pounds, was assigned the role of retrieving boxes from storage. When he respectfully declined the task citing chronic back pain from a sports injury, no one took him seriously. His weight, height, and consistent pleasant demeanor hid his condition. One co-worker expressed utter disbelief when she announced, “Oh, all of a sudden, your back hurts at a time when we rely on you the most!” Even the store owner was shocked as Darryl had never disclosed his condition. In that moment, Darryl felt his character and integrity under attack. If only they knew how much he wanted the same thing, the ability to live life on his terms—not the terms his back pain imposed. Usually, we don't spot these challenges and may find it difficult to understand or believe that someone with a hidden impairment genuinely needs support. We believe what we see, and if it can't be seen, it simply does not exist.

Invisible disabilities include mental, physical, or neurological conditions that go undetected but can impact a person's movement, senses, or activity. Managing an invisible disability is often accompanied by the stress of hiding it. Many suffer in silence rather than disclose the condition for fear of being judged, labeled, or stigmatized. Why risk the possibility that a co-worker may laugh in disbelief, turn in disgust, or diminish the disclosure, when what is needed is to be understood? Many feel that they are not supported at work and feel pressured to prove ailments are real. In a post on BBC.com, Nessa Corkery shares that during her first years of school, she was diagnosed with dyslexia. Mayo Clinic describes the condition as a learning disorder that involves difficulty reading due to problems identifying speech sounds and learning how they relate to letters and words (decoding). As an adult, she studied nursing and landed a position in a hospital. She explains, “I have always been a very confident person and hate to let people think that just because my brain processes things differently that I am not able to do what others can do.” The support available while in school, which helped her succeed, fell short in the workplace. Eventually she realized that she was not able to keep up no matter how hard she tried. She states, “It looked like I was complacent and just didn't care, but I just found it difficult to retain everything at the pace the others could. Nursing staffing shortages are a constant issue, so staff nurses are usually too stressed to take the time to teach students. I found it very difficult to ask for extra help as I was already considered a hindrance.” One of their greatest difficulties is managing the pressure of getting things done as expected, whether it's an internal self-imposed pressure or pressure felt from colleagues. To be able to say, “I just can't do this today,” or ask for help would go a long way in creating a sense of belonging and inclusion. Our lack of sensitivity to someone's disability, especially an invisible one, can lead to misunderstandings, resentment, and frustration. It is impossible for us to be empathetic until we have acknowledged there is a situation for which to be empathetic. If someone uses a prosthetic limb or is visually impaired, it can be easier to understand the difficulties they may face and support them. For others where impairments are not visible, such as depression, multiple sclerosis, or epilepsy, it's often a different story. Thus, it's best to avoid judging and determining ability by what we observe. In addition, we need to be mindful of our language. Everyday terms such as retarded, crazy, nuts, and psycho that we use to describe dislike can diminish the work experience of colleagues and should be avoided. We are ignorant to the harm we are causing and can substitute these terms with alternatives such as outrageous, absurd, or illogical. Our inclusion journey requires that we seek what lies beneath the surface, despite what we see on the outside.

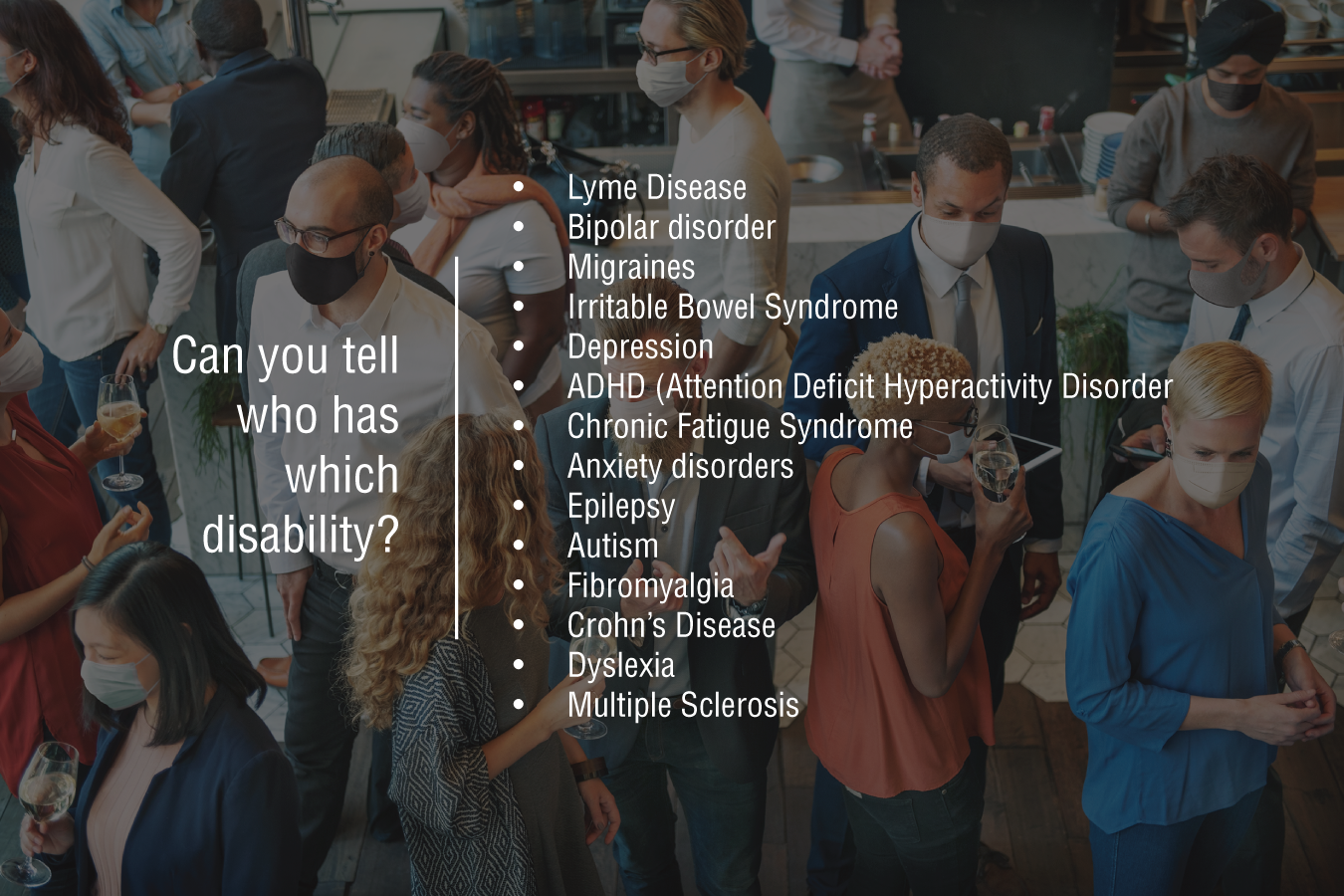

Figure 18.1: Can you tell who has which disability?

Actions

Resist the Temptation to Make a Visual Diagnosis

Visual observations tell only part of the story. Champions of inclusion strive to learn more. Examine types of invisible disabilities. See Figure 18.1 to get started. Get to know the psychological impact as well as challenges and limitations. Choose not to judge based on appearances. Decide now how you will respond when you become aware that a disability exists.

Make Support Ongoing

Everyone, regardless of ability, requires the support of others to be successful. Rather than ignoring or responding in disbelief to the revelation that a co-worker lives with an impairment, be supportive. Listen more than you talk, and step in or step up when a colleague is discriminated against or disrespected (see Activity 26, “If You See Something, Say Something.”) Join or create an employee resource group that focuses on disability in an empowering forum with allies to network and raise issues.

Consider a Day in the Life

Inhabit the shoes of people with invisible disabilities by listening to their stories. Check out:

YouTube.com: The Hell of Chronic Illness, Sita Gaia, TEDxStanleyPark:www.youtube.com/watch?v=sKtbhZpTpbcYouTube.com: Confronting the Invisible, Olivia Larner, TEDxFurmanU:www.youtube.com/watch?v=4QyUdMFNb6s

Simulations of invisible disabilities:

YouTube.com: The Party: a virtual experience of autism, 360 film, posted by The Guardian:www.youtube.com/watch?v=OtwOz1GVkDgYouTube.com: I Wanna Go Home, VR Intellectual Disability Simulation, Enliven, Social Enterprise:www.youtube.com/watch?v=YwnHfdXbras

Action Accelerators

YouTube.com: Invisible Disabilities:www.youtube.com/watch?v=f9OEEU90qdsMindPathCare.com: “Do you know when you're using harmful ableist language?”:www.mindpath.com/resource/do-you-know-when-youre-using-harmful-ableist-languageCdmys.org: “Did You Know? Invisible Disabilities,” Center for Disability Rights:www.cdrnys.org/blog/development/did-you-know-invisible-disabilitiesYouTube.com: Sherpas: Climbing the Mountain of Bi-Polar, Debbie Foster, TEDxCrestmoorParkWomen:www.youtube.com/watch?v=YnihCgrsz3sForbes.com: “Ableism in the Workplace: When Trying Harder Doesn't Work,” by Nancy Doyle:www.forbes.com/sites/drnancydoyle/2019/11/24/ableism-in-the-workplace-when-trying-harder-doesnt-work/?sh=3a29b41915ae

Sources Cited

- Mauro Galluzzo. “We Need to Talk about Dyslexia at Work,”

BBC.com, July 2, 2019,www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20190702-we-need-to-talk-about-dyslexia-at-work