CHAPTER 28

Search

While widespread availability of search technology is only about 15 years old, its implications continue to accumulate. Work and commerce, medical care and mate finding, crime and education all are being reshaped by an effectively infinite base of information made usable by various types of search, indexing, and related technologies. In addition, search is closely related to substantial changes in how knowledge is generated, stored, and distributed.

It remains to be seen how the search era will be positioned in the grand sweep of human intellectual progress. In the short term, several interrelated facets of search should be noted: context, value, impact, and future constraints.

Why Search Matters: Context

Search is in many ways the defining tool of the Internet age. Digital data is ever easier to generate, more of our entertainment takes digital form, globally dispersed actors can find each other and coordinate, and the number of sources of information continues to multiply. As we saw in Chapter 6, the long tail of content production requires search and other matching technologies (including word of mouth and algorithmic “if you liked this you might like that” matching).

Information Volume Is Multiplying

Many sources of information have been separated from their location. Compare the Internet to national and university research libraries, which required dozens or hundreds of years to assemble, cost millions of dollars to sustain and maintain, and employed large staffs of experts in such specialties as acquisitions, cataloging, bookbinding, and archival management. Early search technologies used text-string matching, but Google's major breakthrough was in hyperlink analysis: Links were, in essence, votes on a given site's value. In the past decade, metadata matching and semantic analysis (does the searcher mean “field” as in wheat, magnetic, or career?) have made strides. As a result, technology has made billions of megabytes of information available to billions of people. Those people can be any-where and in any number, so information access is no longer restricted by physical presence. In addition, the virtual resource can be used by as many people as need it at a given instant, unlike physical books or microfilms.

Furthermore, raw data can be consumed and transformed without traveling to physical laboratories or research stations. Weather satellite data, Web-based laboratories for remote experimentation, virtual shared instruments, and worldwide access to webcams or data buoys are only a few examples of shared data sources. National and international statistical authorities are further sources of information that scholars can transform into more formalized outputs.

Finally, repositories of knowledge have different gatekeepers. Books and paper journals are no longer the definitive word in some fields, given how long editorial review and publishing can take. Blogs, e-mails, and videos can find a worldwide audience in just hours, not months or years. As a result, formal cataloging systems for books and journals are not necessarily the authoritative taxonomies of a given field.

Search Changes Information Access

In some ways, access to knowledge has been democratized—many tools, formerly restricted to researchers at a relatively few well-endowed research institutions, including search engines themselves, are now widely available. One example would be LexisNexis licenses, which cost tens of thousands of dollars.*

At the same time, however, literacy is not universal, and search literacy requires a particular form of skill and discernment that is not equally distributed. Search results frequently lack context and in many instances do not speak for themselves. Knowing what one is looking for can be surprisingly difficult, notwithstanding the simplicity implied by the clean input screen. Finally, search results are not objective, yet the results imply an algorithmic ranking in order of fitness, accuracy, or popularity that cannot be assumed yet is difficult to consciously override.

Search Technologies Reinforce Economic Trends

Search has long been recognized as a stage in many transactions, but Google-scale digital search also plays a role in several broad-based economic tendencies.

- Search costs factor into nearly every economic transaction: As buyers and sellers both need to discover each other, compare needs and capabilities, and coordinate, search engines have facilitated easier matching of parties to a transaction.1

- Although many people casually speak of an “information economy,” Stanford professor Paul Romer developed an academic formulation for it around 1990. Commonly known as new growth theory, the Romer theory asserts that land, labor, and capital are no longer the building blocks of a modern economy. Instead, he asserts that ideas create a significant fraction of an economy's value. Conventional economics would portray the end of the petroleum era as implying the end of transportation. But in Romer's view, human innovation will develop new fuel sources and economically viable technologies for utilizing them, then harvest market rewards for doing so.2 In such an environment, search technologies become essential for making an information economy run.

- In Thomas Friedman's formulation, “the world is flat” insofar as certain kinds of value creation become physically removed from their consumption.3 Nurses have to be in the same room as their patients to give injections or take temperatures, but equity analysts or radiologists can be thousands of miles away from the user of their knowledge. Search is both a cause and an outcome of the flattening process as it makes both formal and informal knowledge accessible to anyone with an Internet connection at any time.

- Information is no longer distributed only by broadcast methods. Two influential books—Chris Anderson's The Long Tail4 and Nassim Nicholas Taleb's The Black Swan5—both analyze how power-law distributions explain increasing numbers of events. In the physical world, distributions of height must absolutely fall on a Gaussian distribution, and all examples are within 1 order of magnitude: Every human stands between 1 foot tall and 10 feet tall. In contrast, information landscapes, most obviously the World Wide Web, see billions of page views on a fat-tail distribution where about 1% of Web sites receive roughly 50% of all traffic.6 The remaining half is spread over billions of pages, some with tiny audiences, the so-called long tail of the power-law distribution. Here there are no barriers as to who can serve as editorialist, editor, or publisher. To navigate online auction sites, bookstores, or music services, search becomes an essential service. To perhaps oversimplify, there would be no long tail of content without search engines, and the world would have less need for search without long tails.

Search Changes the Rules of Information Assembly

For thousands of years, assembling information has conferred many benefits, including strategic or tactical advantage, prestige, and erudition. Because books were so valuable, many titles were chained to the shelves in Greek libraries and later in the Sorbonne and elsewhere.7 The invention of the public circulating library was closely connected to the realm of political organization: Benjamin Franklin was intimately involved in both the development of public libraries and the American Revolution. Such a connection separates him from many political figures, regardless of era.

Over the centuries, the emphasis of libraries migrated from assembly (as at Alexandria) to classification. The most notable example of the latter was the French encyclopedists, including Denis Diderot, but the U.S. Library of Congress system stands as another significant milestone. In the Internet period, assembly, such as at the Internet Archive, has fallen to a lower priority, given the power and ubiquity of search. Because Google and its peers render both classification and assembly less important, finding information, rather than owning or organizing it, is often the predominant task.

The Wide Reach of Search

Because search has so rapidly become part of the pattern of everyday life for so many people, remembering how life was transacted before AltaVista, Excite, Google, and Bing can be difficult. A brief list suggests some of the many domains that have already been reshaped by this transformative technology. Each of these is at least a $100 billion industry in the United States; Google is less than 15 years old, making the transformations that much more remarkable.

Media

While Google obviously reinvented the advertising model, other media industries have been deeply affected. YouTube (part of Google) helped change video viewing habits from scheduled to searched. MP3 files are routinely searched online rather than scanned in physical bins. Google News assembles stories with algorithms rather than editors. Such resources as the Internet Movie Database (IMDb), owned by Amazon, figure prominently in search results. Finally, search and matching technologies are at the core of the success of Netflix relative to its physical competitors.

Retail and Secondary Markets

Finding used auto parts, or rare baseball cards, or any of the other millions of items on Craigslist or eBay would be impossible without search. Amazon invested so heavily in its A9 search service that it competed head-to-head with Google for a brief while. Extensive comparison shopping based on price, quality, or location becomes a matter of mouse clicks rather than hours or days of work.

Healthcare

According to the Pew Internet and American Life Project, 80% of Internet users (or 59% of all U.S. adults) search for medical information online.8 This has significant implications for the entire healthcare industry, from the doctor-patient relationship to sellers of niche (and potentially ineffective) remedies.

Employment

People born before 1980 will remember requesting friends to mail the Sunday help-wanted ads from remote cities, which would then arrive the following Thursday, so that application letters could be mailed to post office boxes. In a very short time, the entire process of job hunting has been transformed, largely by search.

Automobiles

From a situation where information asymmetry was extreme (see Chapter 3), and buyers greatly mistrusted both new- and user-car sellers, the Internet has helped bring about greater transparency into both vehicle pricing and used-car history.

Travel

In some ways, search leveled the playing field between small hotels and megachains as do-it-yourself trip planning replaced visits to a travel agent or supplemented branded toll-free reservations systems. Air fares get easier to compare every year, in part by the addition of new features to the major search engines. In multiple ways, search helped alter and diminish the role of the travel agent.

Hospitality

As with lodging, millions of online word-of-mouth recommendations for restaurants have reshaped the industry. With mobile search, finding “Chinese restaurants near me” becomes a simple matter, complete with directions.

Real Estate

While real estate agents have not been disintermediated (see Chapter 21), the search technologies available at a range of sites have reshaped the house-hunting and rental process. Once again, the combination of search and location-based technologies proves to be particularly powerful.

Valuing Search

Even before the Web, according to Kevin Kelly, the founding editor of Wired*, U.S. searches added up to 111 billion a year, most of them directory assistance telephone calls, but he also counted librarian queries. After the invention of free search engines, people appear to be asking more questions: The measurement firm comScore estimated 3 billion searches per day at Google alone. Twitter serves more than 1.5 billion searches per day. The list goes on.

In Kelly's rough estimate, an unnamed Google employee hypothetically and unscientifically values these searches as follows. Here are his assumptions in a thought exercise:

1/4 of all searches are really easy ones (like ‘american airlines’) that save the user maybe 30 seconds;

1/4 are a little hard and save maybe 5 minutes;

1/4 are just wasting time, and

1/4 are hard ones that lead to substantial savings—like diagnosing your serious disease, or choosing the right college, or the right vacation destination.

Suppose it takes 10 searches on average to get one of these “hard” answers, but when you get it, you've saved maybe 3 hours. That averages out to 6 minutes saved/search. Figure average income of $25,000/year, or $12.50/hour. So we get a value of $1.25/search by this metric.9

Assuming the U.S. audience as 2 billion searches per day at that $1.25 per search, and Google's market share of roughly 65%, that would mean that Google creates $584 billion of value for its U.S. users per year.

Given these unofficial numbers and that this is only a thought experiment, even if the numbers are off by a factor of 5, it still means that Google creates 25 cents of value with the average search, at a cost to serve in the range of 0.2 cents. That would represent a hundredfold ratio of customer well-being to cost, a stunning value proposition by any measure.

A more rigorous valuation was performed by the McKinsey Global Institute.10 Again, the numbers get very large. Moving beyond the conventional metrics for search valuation—time savings, price transparency, and increased awareness—the McKinsey study instead proposes a model with nine inputs:

- Better matching of information to need

- Time savings

- Increased awareness

- Price transparency

- Long-tail access

- People matching

- Problem solving

- New business models

- Entertainment

Building from these disparate categories, the study estimated global measurable value created by search at $780 billion. Importantly, some of this fails to register in gross domestic product: Increased consumer surplus from getting a better deal, for example, or from saving time as in the previous example, is not counted. In any event, the magnitude of these sources of value, economic and otherwise, will only grow in the coming years.

Looking Ahead

In the past decade, search has facilitated the broadly decentralized production of information. Finding one's way among a continually growing volume of data and information will be shaped in part by three current forces:

- The growth of hidden data. Online but hidden databases (for example, an airline reservation system behind a search screen and firewall) are known as the “deep Web.” Because they are hidden, search engine crawls discover only a tiny fraction of online information.11 Deep Web information is hidden for a reason, often because it is proprietary and a source of competitive advantage.12

- Generation of semantic metadata. Organizing information often relies on metadata, which is handled in two basic ways. In the top-down approach, semantics (systems of meaning) are built to coordinate data, especially for machine-to-machine transactions, such as financial transactions. These formal semantic maps, known as ontologies, tend to be extensive, labor intensive, and rigid. There are definitely some circumstances in which they are essential; in other situations, ontologies can be little more than a nuisance, particularly if they are implemented but not maintained.

Several ambitious efforts are under way to build a “semantic Web,” utilizing semantics to power database-like Internet queries rather than text-string-based searches.13 George W. Bush attended Yale University and later was elected president of the United States. Asking “How many U.S. presidents attended Yale University?” of a search engine would not work, but querying a database of U.S. presidents would be trivial. Freebase (which is now part of Google) is an attempt to organize information (such as the whole of Wikipedia) with sufficient disambiguation and classification to make queries possible. Other semantic Web efforts focus on scientific publishing, situations in which a working vocabulary is potentially easier to define and organize.

- Human-assisted tagging. In contrast to ontologies imposed from the top down, tagging works from the bottom up. It is the practice of site visitors attaching metadata to an item, commonly a news story or a photo, based on a personal view. There is no effort made to reconcile conflicting terminology; there are no authoritative answers. Instead, simple visualizations such as tag clouds (see Figure 28.1) show popularity of various tags. In the absence of an abstract, tags work well for both image data and text as cost-effective first approximations: They do a “good enough” job of answering a simple question: What is this picture or blog post about?14

Finally, a major question for search in the future concerns “following the money:” How does the escalating competition between search engines questing for better results and largely invisible search engine optimization (SEO) providers affect how information is organized, found, and distributed? Before they founded Google, Sergey Brin and Larry Page stated:

FIGURE 28.1 Tag Cloud Indicating Relative Popularity of Terms at the Author's Blog Page

[From] historical experience with other media, we expect that advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers. Since it is very difficult even for experts to evaluate search engines, search engine bias is particularly insidious.15

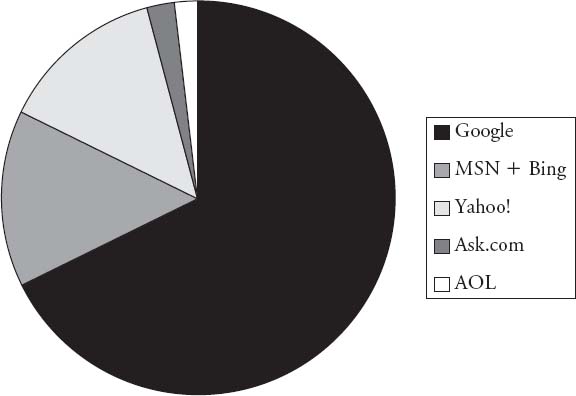

Because search has become the organizing and access mechanism for the majority of online information, Google in particular is making significant decisions behind the scenes as to what people can and cannot find easily, what is important, and what will be commercially valuable to Google. (See Figure 28.2.) The power that comes from “organizing the world's information,” to quote Google's mission statement, means that the company also has a disproportionate influence on what the world knows. Algorithms may seem impersonal, but as we saw in Chapter 22, code is highly political. Google, Microsoft, and InterActive Corp (with Ask) both reflect and shape economic and cultural power with their results, and their users would be wise to bear economic motives in mind when reviewing the apparently objective results.16

FIGURE 28.2 Search Engine Market Share, August 2010

Source: Nielsen.

Frontiers of Search

Text-string searching continues to get better, and mobility brings with it geographic facets of context sensitivity: Typing “pizza” in Tampa brings up nearby restaurants. Type-ahead or auto-fill sometimes can shorten the process. Other innovations in search are making their way into commercialization:

- Video search, of both the images and the audio.

- Mobile search, which includes more precise geolocation input than is available from most PC searches.

- Queries, which build on structured data, as opposed to the free-text nature of search engines. An example might be “tell me all books about roses written in German” or “list the winners of the Best-Actress Oscar who have children.”

- Social search, finding things my friends liked.

- Natural-language questions and answers, which allow people (not machines) to ask and answer complex, nuanced questions: “what car should I buy?” or “where should I go on vacation?” Services including Quora have significant potential in this direction.

- Image search, which involves teaching computers to see the difference between a cat and a fish without a human naming the file or tagging the photo.

- Item search, using cell phone cameras to generate queries, such as “what is this part, or building, or person?” or “where am I standing?”

- Personalized search, which knows my particular uses of certain terms, the sources I routinely reject, and the times of day or of the week that I want certain kinds of responses.

Notes

1. An early paper identified this dynamic, which has obviously scaled and grown more complex in the intervening decade. See John Lynch and Dan Ariely, “Wine Online: Search Costs Affect Competition on Price, Quality, and Distribution,” Marketing Science 19, no. 1 (Winter 2000): 83–103.

2. David Warsh, Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (New York: Norton, 2006).

3. Thomas Friedman, The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century (New York: Farrar Strauss & Giroux, 2005).

4. Chris Anderson, The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More (New York: Hyperion, 2006).

5. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (New York: Random House, 2007).

6. In 1997, 1% of sites attracted 70% of traffic; 2003 figures reaffirmed the hypothesis with weblog data. See Jakob Nielsen, “Zipf Curves and Website Popularity,” www.useit.com/alertbox/zipf.html, and Jason Kottke, “Weblogs and Power Laws,” February 9, 2003, http://kottke.org/03/02/weblogs-and-power-laws.

7. Foster Stockwell, A History of Information Storage and Retrieval (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2001), p. 35.

8. Susannah Fox, “The Social Life of Health Information, 2011,” Pew Internet & American Life Project, May 12, 2011, http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1989/health-care-online-social-network-users.

9. Kevin Kelly, “The Value of Search,” October 16, 2007, www.kk.org/thetechnium/archives/2007/10/the_value_of_se.php.

10. Jacques Bughin et al., “The Impact of Internet Technologies: Search,” McKinsey & Company (July 2011), www.mckinseyquarterly.com/Measuring_the_value_of_search_2848.

11. Alex Wright, “Exploring a ‘Deep Web’ That Google Can't Grasp,” New York Times, February 22, 2009, www.nytimes.com/2009/02/23/technology/internet/23search.html?th&emc=th.

12. Gerry Smith, “Yale Social Security Numbers Exposed In Latest Case of ‘Google Hacking’,” HuffingtonPost.com, August 24, 2011, www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/08/24/yale-social-security-numbers-google-hacking_n_935400.html.

13. See Toby Segaran, Colin Evans, and Jamie Taylor, Programming the Semantic Web (Sebastapol, CA: O'Reilly, 2009).

14. Gene Smith, Tagging: People-Powered Metadata for the Social Web (Berkeley, CA: New Riders, 2008).

15. Sergey Brin and Lawrence Page, “The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine” (1998), http://infolab.stanford.edu/~backrub/google.html.

16. For more on this topic, see Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You (New York: Penguin, 2011).

*One published figure quoted $300 per hour.

*A full-color magazine created in San Francisco that is now owned by Condé Nast and has been publishing stories about technology and related topics since 1993.