CHAPTER 36

Information, Technology, and Innovation

The implications of such a massive transformation are obviously impossible to catalog, much less predict. What follows are some selected areas of business impact resulting from the shifts in the computing, communications, and social infrastructure over the past 20 years or so.

Macro Issues

Business will continue to come in multiple shapes and sizes, and the diversity is important to recognize: Construction or agriculture will always behave differently from banking or health care, but, nevertheless, each sector will see instances of what Carlota Perez described as “synergy” in Chapter 1. The speed of innovation, adoption, and transformation of technologies by their users will continue to accelerate, and, as we have seen, retail might now be facing what music confronted more than a decade ago: a sea of change in customer expectation and behavior with far-reaching consequences for the entire industry.

That said, there are three developments to watch.

- Mobile payments are a logical consequence of rapid smartphone deployment. Smartphone penetration in the United States is at 33% in 2011, up from 20% in 2010. Making the smartphone into a wallet (as in Japan) or a bank branch (as in Kenya) is possible, but the question is whether the technology solves a problem that isn't a problem: Credit cards have a broad installed base in the United States, and a smartphone is more easily lost. Merchants might be hesitant to install more terminals after already paying handsomely for the current device. That said, other countries might see different patterns of adoption, as was the case with text messaging prior to 2005.

- Business will become more “social.” Well beyond putting up a Facebook “like” button, companies will be faced with workers, recruits, partners, and customers who seek more nuanced interactions than are typically provided by a Web site or toll-free call center. Whether it is collaboration to solve a problem, genuine excitement over some happy outcome, prepurchase or preemployment research, or concern over product safety, people want to interact in rich, rapid, personalized ways. This might involve product promotion (Groupon), way-finding (Foursquare), social networking (Facebook Places), or other forms of involvement (Kickstarter or Shopkick). The trend toward social commerce often takes the form of games, and we can expect this tendency to become more pronounced.

- Innovation will be a competitive requirement in more and more sectors. Whether it is the evolution of microfinancing and peer-to-peer lending in financial services, person-to-person coordination for overnight stays (Airbnb), or something as simple yet powerful as Craigslist, established entities can no longer assume the same barriers to entry from previous decades will continue to be effective.

Globalization

While it's difficult to quantify globalization, the fact that there will soon be 4 billion mobile phones in circulation points to a more connected future for every country, save the occasional North Korea or Somalian exception—and in Somalia, the pirates are equipped with an impressive information infrastructure, so the connection is of a different sort.1 As we have seen, the creative uses of the technology for good and for ill are most impressive, and as learning spreads faster on that infrastructure, the cycle of experimentation, innovation, and diffusion will only get faster. Consider that the iPhone was launched in the United States in 2007 and promptly redefined the technology landscape; by 2011, it was available in 105 countries and looks to become popular among China's 700 million mobile phone subscribers now that Apple has distribution partners. This speed is completely unprecedented.

It's also useful to bear in mind the differences in adoption patterns: The mobile phones that are transforming life in Africa, for example, are not doing so with Angry Birds or Facebook but with election fraud monitoring, medical innovations, and banking. At the same time, in the developed world, those “serious” applications have enormous potential even while entertainment, “grooming” (flirting), and social coordination remain important.

A final facet of globalization relates to evolving notions of property rights. When intellectual property, such as songs, movies, and books, can be digitally copied and distributed globally for little cost, maintaining property rights obviously becomes problematic. As we saw with regard to copy protection in Chapter 4, technologically locking down bits in software form has yet to be a long-term solution: People working in pursuit of a shared (possibly illegal) objective can coordinate too easily, and the Internet is too good at moving bits for this to be viable.

An alternative conception of property rights helps Linux work. The General Public License (GPL) is the license protocol that ensures that any programmer's contribution to the software will be recognized as building on the free software with which he or she began. That is, unlike other free software licenses (such as Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD)), the GPL ensures that the free software that is modified cannot have more restrictive conditions imposed as it is redistributed after the changes are contributed. The notion is known as copyleft, or the opposite of copyright in that it protects the freedom of the artifact and the freedom of programmers to add to the code base rather than the property rights of a person or commercial entity.2

Wikipedia uses similar licensing. The result is a substantial public commons that is legally protected from commercial exploitation: People who contribute to a free public good know it will remain free and public and not get commercialized for private gain. At global scale, for certain kinds of goods, this kind of licensing encourages innovation, as Ushahidi (Chapter 12) shows. At the same time, it gives people in developing countries an alternative to the license fees collected by an Apple or Microsoft. Copyleft does not work very well for private goods, however, so the issue of maintaining property rights to movies, for example, remains difficult, especially given the size of the markets involved.

Strategy

While the firm remains a key element in strategic thinking, larger and more fluid entities are also increasing in importance. Technology platforms, human and organizational networks, and even coordinated individuals without corporate identity can alter the strategic landscape.

Platforms

Perhaps more than other industry, the computing and communications sector is characterized not only by product or brand competition (Ford versus Toyota or Pepsi versus Coke) but by platform competition. Platforms imply standards, often-complex ecosystems of suppliers, influencers, content partners, and third-party software developers. Microsoft won one round of platform competition in the 1990s, to be sure, but today the primary contenders appear to be Apple and Google (including allies such as HTC and Motorola) in smartphones, with Nokia and Microsoft a potentially interesting combination. Google dominates search-related advertising; Facebook is similarly strong in demographically targeted display ads. SAP and Oracle control the majority of enterprise software, with various open-source options getting more plausible every year. HP and IBM control a substantial portion of infrastructure, but “platform as a service” cloud vendors, including Amazon, are rewriting the entire book on data centers. Facebook's surge in revenue coincided with the popularity of social gaming supported by the likes of Zynga, the company behind FarmVille and other popular titles. One estimate from the University of Maryland pegs the Facebook app ecosystem employment at roughly 150,000 people, drawing about $15 billion in wages.3

In each of these cases, there is no winner of market share differentiated only by price or performance. Instead, the number of existing users leads to network effects that can be decisively high, as at Facebook (compared to MySpace in particular). Apple's quality of design and user experience matter, to be sure, but Google's Android platform, while notably less elegant, has more users. Instead, the customer weighs the totality of the system, which can include many other entities outside the primary vendor. This breadth and dynamism means that platform builders must walk the fine line between defining a coherent vision and not locking down the potential for the market to take the platform in new directions. Apple did not design the iPad as a teaching tool for children with autism, for example, but it excels in that role thanks to some clever applications expertly designed by people addressing those particular needs.

One way of thinking about this platform dynamic is a shift in emphasis from nodes (centers of mass, or assets) to links: connections. The force driving that transformation is the growth of networks—superficially, digital data conduits and, more crucially, the new possibilities for human connection that ride on those links. Networks and their implications have historically overturned existing rules of business strategy, whether the network was comprised of ships (England), wires (AT&T), or distribution centers (Wal-Mart). In each of these historical revolutions, the definitions of who was competing, what they were competing for, and what constituted an advantage shifted in ways that rendered many conventional strategic choices ineffective or even dangerous. We are at another such juncture today.

Consider an example of one way networks alter strategy. Just as al Qaeda has no intention of invading New York, neither does BitTorrent seek to become a record label or movie studio. In such unconventional confrontations, the insurgent doesn't want what the incumbent wants—market share, profitability, or whatever—but its goals may impede or deny the corporate pursuit of these goals. This particular asymmetry of objectives makes business strategy much harder to set; once an actor no longer contends with an outside party with either identical or mirror-image objectives, definitions of success and failure can become much more difficult to identify or counter.

Listening to the Warriors

As business strategy in the past has borrowed from military strategy for insight, we can benefit from current thinking about fighting new kinds of adversaries. In an article in the Washington Post, defense analyst John Arquilla put matters succinctly. “It takes a tank to fight a tank. It takes a network to fight a network,” he said, quoting his own book, In Athena's Camp.4 That book, cowritten with David Ronfeldt, makes several compelling arguments about what the editors call “netwar,” a fight among networked components. Significantly, this is not necessarily fought on the Internet; that notion they usefully distinguish as “cyberwar.” The entire concept of netwar carries directly into the field of business strategy, helping define new guidelines for achieving advantage in a networked environment.

When Arquilla and Ronfeldt speak of the great powers and say “Look around. No ‘good old-fashioned war is in sight,’”5 they could easily be describing key aspects of the corporate landscape. While geopolitical combat can pit nonstate actors (whether nongovernmental organizations, religious sects, or terrorist organizations) against nation-states, businesses confront constraints from such noncorporate entities as AARP, Napster and then Grokster, and Linux, not to mention governments in their standard-setting and regulatory capacities. Arquilla and Ronfeldt point out that in these types of conflict, “disruption may often be the intended strategic aim rather than destruction.”6

Summing up, Arquilla and Ronfeldt contrast chess, the old strategy archetype, with Go, a fascinating emblem of the new (at least in the West). Go, they assert,

is more about distributing one's pieces than massing them. … It is more about developing web-like links among nearby stationary pieces than about moving specialized pieces in combined operations. It is more about creating networks of pieces than about protecting hierarchies of pieces.7

This extended analogy serves nicely as a thought exercise for aspiring network strategists. Corporate strategy has often been a pursuit of mass, an exercise premised on given rather than malleable industry structure, an exercise in vertical integration rather than horizontal connection. As our networks reach deeper and future innovations take increasing advantage of the dominant network models, we will see more and more business dynamics that, for better and worse, parallel what we are seeing as a new chapter in military strategy.

One Path from Military Strategy to Business Management

To understand the contours of classic business strategy, it is helpful to discern its western military heritage: Competitors are seen as enemies and the marketplace is typically a battleground. The similarities are more than rhetorical. Modern business strategy's kinship with military theory dates primarily to the mid-nineteenth century, when a cadre of graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point came into positions of authority. West Point trained the first of America's engineers, who went on to design such key infrastructure as railroad bridges in the Civil War. The ability to impose one's will across time and distance required lines of authority and communication that transcended physical proximity. The West Point training emphasized the importance of written orders, similar to business memoranda. Later, war veterans played key roles in the growth of commercial railroads, which employed the engineering point of view both in how they operated and, more subtly, in the organizational design necessitated by the first distributed, coordinated national enterprises.

What are the key tenets of classic business strategy that emerged from these military origins? In its simplest form, an organization or military operation should resemble a pyramid: Power and intelligence are concentrated at the top and trickle down to the wide bottom of the hierarchy, where both power and intelligence are presumed to be minimal. The ultimate goal is the familiar “command and control,” which necessitates getting subordinates to do what you want while preventing them from doing what you don't. The obvious drawback to such an objective is the chaotic nature of combat, the aptly named fog of war that limits commanders' knowledge of cause and effect as well as their ability to either command or control distributed, self-organized (and to some degree self-interested) forces.

By the 1990s, military strategists like U.S. Marine Lieutenant General Paul K. Van Riper became aware that this advantaged position mentality would not serve in the new battlefield. No longer was his the rhetoric of command and control; instead, Van Riper granted that “warfare is uncontrollable once you unleash it, so the best you can do is control your use of force within the phenomenon itself.” The new battlefields of war and work were more fluid, dynamic, and interconnected, and thus called for new strategic agility. “Commander's intent”—what needed to be done—came from the top; plans of action—how to do it—were now left to units closest to the action. Pyramids were out; natural phenomena like swarms were in. But the transition from models to operations was rarely simple. Both military and business leaders have learned that networks shape competition in complex ways, and devising strategic frameworks to cope with those complexities has been far more difficult than expected.

U.S. military strategy, meanwhile, is being reshaped by multiple forces:

- The notion of the “three-block war” in which armed insurgents are battled in one city block, peacekeeping is the mission next door, while in the third sector, armed forces deliver humanitarian aid

- Insurgents who blend in with local populations, as in Afghanistan

- The rise in the use and effectiveness of improvised explosive devices, often detonated by mobile phones

Challenging Porter

Today, one still hears echoes of old military thinking in the work of business strategists like Michael Porter, whose body of work dominates MBA curricula and strategy consulting methodologies alike. Porter explores the ways in which proper corporate strategy defends advantageous business positions. Although this classic perspective holds some valuable lessons, Porter's strategic orientation misses the explosive dynamics typical of network behavior. His new theory of shared value, meanwhile, has yet to take hold with the power of the still-canonical five forces, which have held sway since 1979.8

Strategic thinking, in his formulation, occurs within a context of these forces: those exerted by customers, suppliers, competitors, potential competitors, and product substitutes. Several events of the past decade, however, challenge that perspective. It was particularly easy in 1999 to say that networks change everything, and Porter (in a March 2001 article in Harvard Business Review) was correct to assert that overenthusiasm led some managers and investors to forget the basics that don't change, profits being foremost. But three examples of networked challenges to existing businesses would seem to break Porter's model and confirm the disruptive power of the new models, particularly ones that deny the ability of corporations to create “unique sustainable competitive advantage” through coercive or other forms of consumer lock-in.

The three entities are Napster, Linux, and ecoterrorist cells. In each case, a networked entity is not competitor, or supplier, or customer. Even so, the entity poses a formidable challenge to incumbents' definitions of business as usual. These entities fail to respond to conventional interventions, such as price cuts, market exit, or merger and acquisition activity. Further, none of the three entities is a business, and as such none plays by the same rules as businesses. The disrupters are something more significant than competitors, insofar as they don't threaten market share as much as they challenge the foundational assumptions of an entire economic (and often social or cultural) sector. Networks have the potential not only to compete with firms but to transform entire markets that constituent firms take largely as given.

The facts of the music industry are for the most part well known: Napster grew to 20 million users in about a year, the sum of whom downloaded the equivalent of 1.5 to 2 times the entire U.S. volume of compact discs sold in 2000. Napster was not conceived as a business but as a guerilla technology, so it did not need to profit to succeed. At the same time, neither did it treat the existing music industry with much respect. The incumbents used their lobbying power to render Napster illegal, and it effectively ceased operations in 2001. It's noteworthy that, contrary to the labels' complaints, CD sales in fact decreased after the service was shut down by court order. Porter's landscape has no place for Napster in the music industry, and his advocacy of lock-in tactics was confronted by an open network that explicitly denied the industry's right to charge upward of $12 to $15 for a collection of songs when only one was going to be played.

Linux is built by a much smaller online community of thousands of technologists, but the distribution channel is similar to Napster's. Even though Microsoft lacked full copyright control over someone else's intellectual property the way record labels did, it responded in much the same way as the music industry by trying to brand the operating system and the principles it was built on as “un-American.”9 This tactic appeared to backfire even as Microsoft was tightening its grip on users through means both technical (usually involving Internet Explorer, as when RealNetworks sued Microsoft over the use of bundling with Windows Media Player) and economic (new enterprise software licensing terms). One mistake might be to take a Porterian view of Linux the software distribution as a product substitute when in fact Microsoft's far bigger concern is presumably with the network of users and developers who connect with each other in a completely new way—Linux the idea and network that once again exist entirely outside the Porter five forces.

Tom Malone of MIT's Sloan School nailed the point in his Harvard Business Review article. He states that Linux is more than a science-fair project of supersmart programmers, more than “a neat Wired magazine kind of story:” “This interpretation, while understandable, is shortsighted. What the Linux story really shows us is the power of a new technology—in this case, electronic networks—to fundamentally change the way work is done.”10

A final example is a hazy and more troubling one. At the outset, I should make clear that I am not applauding this group's activities but rather analyzing the implications of its organization. A band of radical environmental activists, operating most visibly in America's Pacific Northwest, utilizes a cell structure to avoid detection and resist infiltration. Each group is autonomous, sharing only broadly defined goals within a loosely defined movement. The groups use a variety of methods, most illegal and some life-threatening, to interrupt logging and bioengineering. Political insurgents have operated in cells for millennia (the groups in the Bible certainly weren't the first), but what's new is the Internet's ability to connect today's groups, and to spread their messages, while preserving anonymity. As their Web site states: “The Earth Liberation Front (ELF) is an international underground organization that uses direct action in the form of economic sabotage to stop the exploitation and destruction of the natural environment.”11

The ELF is not a group but an extremely loose network. There is no centralized authority, no membership list, no physical headquarters. Where do these groups fit on, for example, Weyerhaeuser or Boise Cascade's Porterian radar? Rather than competing with these and other timber companies, at their most extreme the ELF and similar groups deny the right of the businesses even to exist in the first place. What is an appropriate, or even feasible, strategic response? Porter's battlefield is cleanly defined (in large measure by a highly visible and fairly rigid industry structure), resembling, as many have said, a chess board. The real world is far messier as the ELF and other groups move the competition and disruption into culture and politics.

Speaking of the three challenges to Porter, members of the World Economic Forum, MBA faculties, and other business-political groups have been struggling both to understand and to respond to these new types of phenomena that utilize distributed and loosely coupled networks to disrupt and even disable various forms of centralized and tightly defined hierarchies. In conventional economic terms, there is no set model: The ELF destroys economic value, Linux creates it, and Napster redistributed it. The three examples confirm that even if it doesn't change literally everything, the Internet is redefining the competitive landscape in ways that extend far beyond what current businesses have had to confront.

Organizations

The firm, while still important, is no longer the default model for organizing resources to get work done. Similarly, the record label and publishing house are challenged by direct-to-market content distribution models. As both examples (Wikipedia) and tools (Ushahidi) get better and more recognized, it seems unlikely that organizational innovation will slow. An example can be found in Barack Obama's 2008 presidential campaign: Utilizing grassroots fundraising methods building on candidate Howard Dean's 2004 breakthrough, along with social media tools including Web video, text messaging, and a Facebook-like MyBarackobama.com infrastructure, the campaign set records for fundraising and participation. The same methods are expected to contribute to the first billion-dollar presidential campaign in 2012.

Regardless of the shape of the organization, today's tools mean that talent matters significantly: Even with high unemployment overall, the role of difference makers in government, nonprofits, start-ups, and of course the corporate sector relates heavily to the information and technology landscapes. Whether it is Apple design chief Jonathan Ive, Wieden+Kennedy social media account executive Iain Tait (who spearheaded the Old Spice campaign that more than doubled sales), Facebook chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg, or Silicon Valley green technology investor Vinod Khosla, talented individuals are in high demand.

New organizational forms are emerging in many sectors.

- Mobile virtual network operators (MVNOs) are basically mobile phone companies that rent infrastructure from other parties. Virgin Mobile was among the first of these. Bringing a brand but not needing to buy wireless spectrum or build networks or billing systems, MVNOs are quite common: More than 500 were in operation as of 2011, though not all of these will survive. Amazon's Whispernet distribution service on the Kindle reader is an MVNO.

- The one-deal-at-a-time retailers we saw in Chapter 21 merge shopping, social networking, and entertainment. Supply chains, accounting, merchandising, and customer service all need to be reinvented for such companies as Gilt Groupe, Backcountry.com, and Amazon's woot! unit.

- Athletic conferences, professional sports leagues, and select individual franchises are reinventing what it means to be a television network. The University of Texas is undertaking the newest experiment in revenue-generating content distribution: It signed a $300 million, 20-year deal with ESPN in 2011.

Marketing

Given the primacy of the traditional four Ps of the field—product, price, promotion, and placement—when price goes to zero for several categories, it's newsworthy. The music and news industries are visible examples, but other industries that formerly capitalized on expertise and relationship management have seen the price for those services drop to zero: Ask a stockbroker or travel agent about the transition. Maps, online education (but not certification), and international voice telephony are other settings where up to billions of dollars—in the case of telecoms—of revenue have vaporized.

The emergence of free stuff means responding in some industries or capitalizing in others. Some musicians have responded to free downloads with heavy touring schedules: The Dave Matthews Band earned more than $500 million over 10 years on the road.12 Television networks found success with Hulu but appear to be unsure what to do with it, given that the revenue model does not mirror that of cable networks. Thousands of startups run on Skype; many companies post assembly instruction videos free on YouTube; Asus computers uses peer-to-peer networking provided by BitTorrent to help distribute software downloads. Free is hard to compete with, to be sure, but it presents ample opportunities as well.

Another key marketing dynamic is transparency. As social media empowers conversations among customers and between customers and a brand, the one-size-fits-all model or corporate branding—“Built Ford Tough!”—is being joined by a more human dimension in which the customers' voices are incorporated into the brand. The Skittles Web site color is dictated by the number of social media mentions, which are incorporated into the site, along with, at times, user-generated content, such as videos. Transparency is tricky, however, since it requires a corporate culture to show through to the world. Managing this process remains among the most challenging aspects of the current environment.

Transparency can also be a fluke: The U.S. raid that killed Osama bin Laden was being tweeted in real time by an information technology contractor who wondered why all the helicopters were converging on his small, out-of-the-way village. China's earthquake in 2008 was live on Twitter before the U.S. Geological Survey had anything. Apple has had photos of iPhone prototypes make their way onto the Web via such sites as Gawker, Gizmodo, and the like.

It's a familiar business school discussion. “Let's talk about powerful brands,” begins the professor. “Who comes to mind?” Usual suspects emerge: Coke, Visa, Kleenex. “OK,” says the prof, “what brand is so influential that people tattoo it on their arms?” The answer is, of course, Harley-Davidson.

There is another category of what we might call “tattoo brands,” however: sports teams. Measuring sporting allegiance as a form of brand equity is both difficult and worth thinking about, both because sports can be seen as information goods and because technology is changing the fan experience.

For a brief definition up front, The Economist's statement will do:

Brand equity is the value of the brand in the marketplace. Differentiation demonstrates unique value to customers, and how this is communicated is important to building brand equity. Brands that have a meaningful point of difference are more likely to be chosen repeatedly by consumers and ultimately have a much higher potential for growth than do other brands.13

That is, people think more highly of one product than another because of such factors as word of mouth, customer satisfaction, image creation and management, track record, and a range of tangible and intangible benefits of using or associating with the product.

Our focus here will be limited to professional sports franchises, which generally have three primary revenue streams:

- Television rights

- Ticket sales and in-stadium advertising

- Licensing for shirts, caps, and other memorabilia

Of these, ticket sales are relatively finite: A team with a powerful brand will presumably have more fans than can logistically or financially attend games. Prices can and do rise, but for a quality franchise, the point is to build a fan network beyond the arena. Television is traditionally the prime way to do this. National and now global TV contracts turn viewership into advertising revenue for partners up and down the value chain from the leagues and clubs themselves. That Manchester United and the New York Yankees can have fan bases in China, Japan, or Brazil testifies to the power of television and, increasingly, various facets of the Internet in brand building. Twitter is a prime example.

Sports fandom exhibits peculiar economic characteristics. Compared to, say, house or car buying, fans do not research various alternatives before making a presumably “rational” consumption decision: Team allegiance is not a “considered purchase.” If you are a Boston Red Sox fan, your enthusiasm may or may not be relevant to mine: Network effects and peer pressure can come into play (as at a sports bar) but are less pronounced than in telecom, for example. If I am a Cleveland Cavaliers fan, I am probably not a New York Knicks fan: A choice in one league generally precludes other teams in season. Geography matters, but not decisively: One can comfortably cheer for San Antonio in basketball, Green Bay in football, and St. Louis in baseball. At the same time, choice is not completely independent of place, particularly for ticket buying (as compared to hat buying).

Finally, switching costs are generally psychic and only mildly economic (as in having to purchase additional cable TV tiers to see an out-of-region team, for example). Those psychic costs are not to be underestimated: Just because someone lives in London with access to several soccer clubs, allegiances are not determined by the low-price or high-quality provider on an annual basis. Allegiance also does not typically switch for reasons of performance: Someone in Akron who has cheered, in vain, for the Cleveland Browns is not likely to switch to Pittsburgh even though the Steelers have a far superior championship history. All in all, sports brand equity is unlike most products'.

Given the vast reach of today's various communications channels, it would seem that successful sports brands could have a global brand equity that exceeds the club's ability to monetize those feelings. I took five of the franchises ranked highest on the Forbes 2010 list of most valuable sports brands and calculated the ratio of the estimated brand equity to the club's revenues. If the club were able to capture more fan allegiance than it could realize in cash inflows, that ratio should be greater than 1. Given the approximations I used, that is not the case.

For a benchmark, I also consulted Interbrand's list of the top global commercial brands and their value to see how often a company's image was worth more than its annual sales. I chose six companies from a variety of consumer-facing sectors (thus ruling out IBM, SAP, and Cisco), and the company had to be roughly the same as the brand (the Gillette brand is not the parent company of Procter & Gamble).

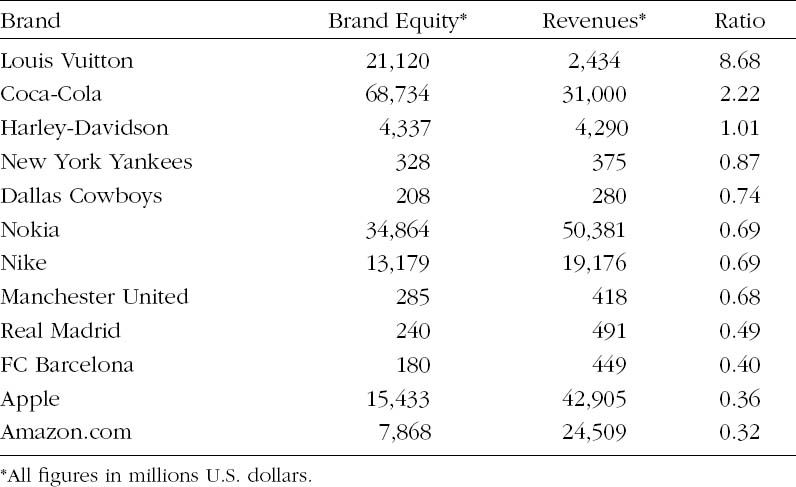

Three points should be made before discussing the results, which are summarized in Table 36.1.

- Any calculation of brand equity is a rough estimate: No auditable figures or scientific calculations can generate these lists, as Interbrand's methodology makes clear.14

- Forbes and Interbrand used different methodologies. We will see the consequences of these differences shortly.

- Corporate revenues often accrued from more brands than just the flagship: People buy Minute Maid apart from the Coca-Cola brand, but the juice revenues are counted in the corporate ratio.

All told, this is not a scientific exercise but rather a surprising thought-starter.

TABLE 36.1 Ratio of Brand Equity to Revenues for Selected Brands, 2010

The stunning 8:1 ratio of brand equity to revenues at Louis Vuitton is in part a consequence of Interbrand's methodology, which overweights luxury items. Even so, six conclusions and suggestions for further investigation emerge:

- The two scales do not align. The New York Yankees, the most valuable sports brand in the world, is worth 1/24 that of Amazon. One or both of those numbers is funny.

- Innovation runs counter to brand power. New Coke remains a textbook failure, while Apple's brand is worth only about a third of its revenue. Harley-Davidson draws its cachet from its retrograde features and styling, the antithesis of innovativeness.

- Geography is not destiny for sports teams. Apart from New York and Madrid, the cities of Dallas, Manchester, and Boston (not included here but with two teams in Forbes' top 10) are not global megaplexes or media centers; London, Rome, and Los Angeles are all absent.

- Soccer is the world's game, as measured by brand: Five of the 10 most valuable names belong to European football teams. The National Football League has 2 entries, and Major League Baseball 3 to round out the top 10 list. Despite the presence of more international stars than American football, and their being from a wider range of countries than MLB's feeders, basketball and hockey are absent from the Forbes top 10.

- Assuming for the sake of argument that the Interbrand list is overvalued and therefore that the Forbes list is more accurate, the sports teams' relatively close ratio of brand equity to revenues suggests that teams are monetizing a large fraction of fan feeling.

- Alternatively, if the Forbes list is undervalued, sports teams have done an effective job of creating fan awareness and passion well beyond the reach of the home stadium. Going back to our original assumption, if tattoos are a proxy for brand equity, this is more likely the case. The question then becomes: What happens next?

As more of the world comes online, as media becomes more participatory, and as the sums involved for salaries, transfer fees, and broadcast rights at some point hit limits (as may be happening in the National Basketball Association), the pie will continue to be reallocated. The intersection of fandom and economics, as we have seen, is anything but rational, so expect some surprises in this most emotionally charged of markets.

Supply Chains

When things went wrong in the past, customers might not know for months, if ever. As systems interconnect and social media tools give anyone access to a global audience, bad news now travels fast and sometimes widely: A wave of suicides at Foxconn, a contract electronics manufacturer, made global front-page news in part because of the company's highest-profile customer: Apple. Procurement managers now have the challenge of competing with nonindustry speculators who invest purely for profit; corn is one such commodity that has been transformed by interconnected global markets and the supercharged electronic trading systems that accompany such networks.

Apart from the speed of bad news, there's the long tail: Stock-keeping unit counts at Amazon, Netflix, and eBay are staggering. Managing inventory in such a world is an entirely different exercise compared to traditional retail. Given the primacy of search, matching technologies, and social word of mouth in connecting dispersed communities of buyers with unique tastes with big, dispersed inventories, supply chains can be challenging. Even Redbox, the kiosk-based DVD rental company, has had to be extremely clever about getting discs from where they're returned to the next available machine: College students will rent in Ann Arbor, for example, then drive south for spring break, returning DVDs at various locations down I-75. Standard planning software cannot accommodate such unpredictable behavior at a micro level; thinking more broadly, however, spring break is a predictable event, and algorithms can “learn” over time.

The IT Shop

The long evolution from the days of centralized, predictable tasks on mainframe computers—the heyday of the data processing group—to highly distributed, user-driven environments has entered a new phase in many companies. Three trends bear brief mention: clouds, consumerization, and “deperimeterization.”

- Cloud computing is by no means the answer to everything, but it is greener, more capital-efficient, and more responsive to changing circumstances than many on-premise hardware solutions. Finding how and where clouds make sense, and finding risk-mitigated ways to build them, will continue to be a priority for the industry.

- What Doug Neal at IT services vendor CSC has called “consumerization” will continue to accelerate. Employees will experience mobility, data analytics, and real-time responsiveness in consumer settings, then bring their expectations to the corporate computing world. The information technology organization as a controlling gatekeeper is in some companies evolving to the concierge-like role: The chief information officer at the enterprise software vendor SAP says his goal is to become device-agnostic, given the pace of innovation in smartphones and tablets.15

- Keeping information secure is harder in a mobile environment. Whereas a firewall metaphor was useful for a time, the untethering of so much of the infrastructure means that boundaries between inside and outside, and between us and them, are dissolving. It's a clumsy word, but the enterprise has become deperimeterized. That tendency pushes security from an enclosure project (keep our stuff safe and the bad guys out) to a much more complex task of education, prevention, and risk management.

Implications

The consequences of these and the other trends discussed in this book are not simple or easily summarized. At a broad level, five clusters of issues emerge.

- Change happens fast. More than once executives have expressed exasperation that the world is moving too fast for their company's internal processes, cultural comfort, and planning cycles. In addition to the impracticality of slowing the world down, getting companies to move faster can be impossible. The stakes are high indeed.

- The worlds of technology and information are increasingly dominated by platforms and systems, which require different levels of strategy and execution compared to product-centric environments. System thinking is difficult to coax from a single organization; from an ecosystem of self-interested optimizers, it is, again, nearly impossible. Platform strategies, when executed well, are powerful indeed: Think of Intel, or PayPal, or Facebook.

- Organizations are challenged to find the right size and shape from which to address their constituencies. This is no less true of militaries, governments, and nonprofits than it is of traditional businesses. Lower costs of coordination, faster customer and competitor behaviors, and lightweight infrastructure mean that jobs, tasks, roles, and supervisory relationships are all changing.

- One facet of the organizational question relates to physical place as it relates to cyberspace. Where are physical assets, face-to-face collaboration settings, and backup resources located? At the same time, place/space is reshaping personal identity, relationships inside and away from work, and the range of possibilities for convening problem solvers, fans, concerned parties, or bad guys for that matter.

- Finally, risk is, well, riskier in a more connected world. Whether in financial markets, organized crime, or just random events, the web of interconnection puts entities into the position of feeling effects generated far away. In addition, the speed of connection accelerates: The AIDS virus was spread by a flight attendant who worked on airplanes flying a reasonably fast 500 miles per hour. Cyberviruses move at two-thirds the speed of light, or about 120,000 miles per second. That's a factor of about 124,000 times faster. Are decision processes and reaction times accelerating in parallel? Hardly. And with more information comes more noise. Therein lies the challenge in a nutshell: In a time of extreme speed and scale, how do human decisions and processes keep up?

The Last Word …

Is innovation. If information technology is to have broad social impact—and if, as Carlota Perez suggests, we are in the phase of economic history in which information technologies are absorbed into a multitude of everyday artifacts and processes—businesses, governments, and other institutions must move beyond the straightforward practice of optimizing existing practices. All of these organizations must innovate, in more domains, at deeper levels. Such processes as education, death and dying, and career management are ripe for reconceptualization and reinvention.

That need for innovation is also reflected in the realities of the workplace, wherever it might be located. To generate the required number of new jobs and to address the negative outcomes of past decisions (whether environmental damage, certain forms of discrimination, or public health issues), innovation needs to be the human mandate, rather than a deterministic technological outcome, of the information age.

Notes

1. Neal Ungerleider, “Somali Pirates Go High Tech,” Fast Company, June 22, 2011, www.fastcompany.com/1762331/somali-pirates-go-high-tech.

2. GNU General Public License, Version 3 June 29, 2007, www.gnu.org/copyleft/gpl.html.

3. “UMD Study Finds Facebook Applications Create More Than 182,000 New U.S. Jobs Worth $12.19B+,” University of Maryland, news release, September 19, 2011, www.rhsmith.umd.edu/news/releases/2011/091911.aspx.

4. John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt, In Athena's Camp: Preparing for Conflict in the Information Age (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1997).

5. Ibid., p 1.

6. Ibid., p. 3.

7. Ibid., p. 11.

8. “Oh, Mr. Porter,” The Economist, March 10, 2011, www.economist.com/node/18330445.

9. The head of Microsoft's operating systems group stated: “Open source is an intellectual-property destroyer…. I can't imagine something that could be worse than this for the software business and the intellectual-property business. I'm an American; I believe in the American way. I worry if the government encourages open source, and I don't think we've done enough education of policymakers to understand the threat.” Andrew Leonard, “Life, Liberty and The Pursuit of Free Software,” Salon.com, February 15, 2001, www.salon.com/2001/02/15/unamerican/.

10. Thomas Malone and R Laubacher, “The Dawn of the E-lance Economy,” Harvard Business Review 76, no. 5 (September/October 1998): 144—152.

11. http://earth-liberation-front.org/.

12. Annie Lowrey, “In a dying industry, Dave Matthews Band has found its niche – and big money,” Washington Post, January 8, 2011, www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/01/08/AR2011010804596.html.

13. http://going-global.economist.com/blog/2011/04/08/the-value-of-brand-equity/.

14. www.interbrand.com/en/best-global-brands/best-global-brands-methodology/Overview.aspx.

15. Bob Evans, “Global CIO: Inside SAP: 2,500 iPads Are Only the Beginning,” Information Week, January 13, 2011, www.informationweek.com/news/global-cio/interviews/229000630.