CHAPTER 12

Mobility

By looking at the ways that mobile phones and data devices are transforming developing economies, a contrast with more familiar patterns can emerge. While convenience, social needs, and an extension of desktop computing patterns can be observed in the United States and other locales in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), in Kenya, the devices, payment processes, and application portfolio can differ significantly. In what is being termed “frugal innovation” or “reverse innovation,” the developing countries are pioneering new uses and mental frameworks, showing more mature markets the way forward on critical axes such as disaster responsiveness.

Bottom Up

It's easy to look at the worldwide adoption of the mobile phone in quantitative terms and be amazed. The speed with which literally billions of the world's poorest people have gained access to or even possession of mobile telephony and then data services is staggering. In the late 1990s, it was commonplace to say “half the world has never made a phone call.” That might have been true in 1985, but by 2000, it was nonsense. Even so, United Nations' Secretary General Kofi Annan said so. So did Al Gore, HP chief executive Carly Fiorina, and AOL founder Steve Case.

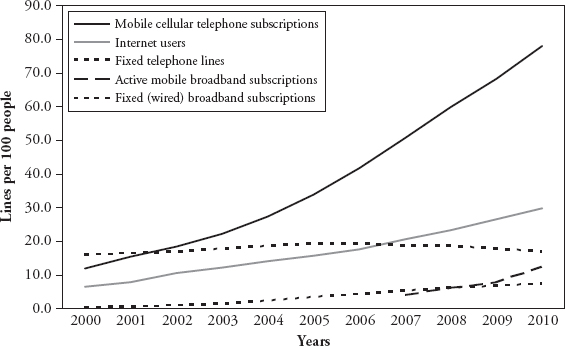

As Clay Shirky pointed out in a terrific essay from 2002, however, such assertions ignored truly explosive growth, first in land lines then in cellular: “[H]alf again as many land lines were run in the last 6 years of the 20th century as were run in the whole previous history of telephony.” That's a lot. But mobile phones were growing far faster: a tenfold (1,000%) increase in the five years ending in 2000.1 That near billion then multiplied another five times in the following 10 years: That's an estimated 5 billion mobile phones on a planet of roughly 6.8 billion. India alone added 128 million subscribers—in one year.2 The macro situation is summarized in Figure 12.1.

The infrastructure is keeping pace with the handsets: According to the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), 90% of the world's population has cellular coverage. Even Africa, at 50% coverage of the rural population, has grown from 20% only seven years earlier.3 This is astounding growth: Again according to the ITU, “in 1985, some three billion people, or around half of the world's population, lived in economies with a teledensity (telephone lines per 100 inhabitants) of less than one. The global average teledensity was around seven.”4 Now there are about as many telephone connections as there are people, which is not the same as saying those connections are equally distributed. Even so, the planet has reached 100% teledensity, statistically anyway.

Three key business innovations helped facilitate this rapid growth. First, the lack of credit and banking structures for billions of people precluded adoption of the post-paid model, in which the carrier gives the subscriber credit up front and (ideally) collects bills based on use after the fact. Prepaid phones allowed users to pay “by the drink” and reduced credit risk for the carriers. Mom-and-pop convenience stores allow users to top-up minutes, multiplying the reach of the carrier beyond expensive company stores.

FIGURE 12.1 Mobile Telephones Compared to Other Technologies, 2000–2010

Source: International Telecommunications Union.

Second, the price of handsets was often subsidized in the West by long-term contracts: A Verizon cell phone might be only $40, but the two-year service contract, at (say) $50 per month means that the product/service bundle will cost the customer $1,240 over the life of the contract. That leaves plenty of pricing flexibility to sell the $40 handset at a loss. With the recognition of the size of the prepaid markets in such populous countries as Brazil, India, and Mexico, handset manufacturers were spurred by two factors: the size of the market for low-price phones and tough competition from each other. Motorola, to take one example, lost significant market share to South Korean companies in the early 2000s; Nokia, which sells well in the developing world, lost the smartphone market to Apple and the Google Android coalition a few years later. For both reasons, along with Chinese manufacturing costs and expertise, carriers in the developing world can offer low-cost handsets for a reasonable percentage of per capita monthly income. The Chinese firm Huawei also aggressively targeted the carrier equipment market, winning market share from Sweden's Ericsson for cellular transmission equipment.5

Finally, monthly subscription or per-minute prepaid charges dropped substantially in the face of competition. For many countries accustomed to government-sanctioned (or-run) telecom firms, the introduction of competition involved some cognitive dissonance, but prices in country after country dropped steeply after a second or third wireless carrier entered (or was allowed to enter) the market. Other entrants, in the form of wholesalers, helped lower costs as they helped network owners pay off capital investment as well as serve additional market segments.

But rather than look at teledensity and similar numbers, it's important to understand the qualitative differences that this rapid adoption of mobility is introducing. Jenny Aker and Isaac Mbiti undertook a systematic study titled “Mobile Phones and Economic Development in Africa” in 2010. They identify several mechanisms of impact, which I adapt slightly here.

- Mobile phones can improve access to and use of information, thereby reducing search costs, improving coordination among agents, and increasing market efficiency.

- This increased communication should improve firms' productive efficiency by allowing them to better manage their supply chains.

- Mobile phones create new jobs to address demand for mobile-related services, thereby providing income-generating opportunities in rural and urban areas.

- Mobile phones can facilitate communication among social networks in response to shocks, thereby reducing households' exposure to risk.

- Mobile phone-based applications and development projects—sometimes known as m-development—have the potential to facilitate the delivery of financial, agricultural, health, and educational services.6

Search Costs

Given the high degree of information asymmetry in the developing world, getting buyers and sellers on the same page can have substantial benefits. For agricultural goods, taking grain to market on foot or over long distances generally precluded bargaining: The price discovery effort was so great that hauling the crop home to wait for a better price was generally impractical. Simply being able to know the price before setting out is a significant advancement. Labor can be hired more efficiently as well, with faster responsiveness to changing conditions than can be achieved through newspapers, for example.

A Harvard economist found far-reaching benefits for the use of mobile phones in Indian sardine markets. Offshore, the fishermen had to commit to a port for fuel reasons without knowing the price or even if a buyer and ice would be available. If the fisherman guessed wrong, fish were dumped into the water at the port. An estimated 5% of the catch was wasted outright, and most fishermen sailed in and out of only one port even though multiple fish markets operated in a nine-mile range.

With the introduction of basic cell phone service around the turn of the twenty-first century, markets worked significantly better. Thirty-five percent of fisherman sailed to alternate ports once they got confirmation of a buyer. Fishermen's profits went up 8% while consumer prices fell 4%, presumably because the surplus fish were not wasted as often. Reduction in information asymmetry resulted in much closer pricing at markets up and down the coast. Better communication made one particular fishery market work better, and similar examples can be found in many developing economies.7

Supply Chain Efficiency

When the McKinsey Global Institute sought to explain the extraordinary growth in U.S. productivity between 1995 and 2000, technology in and of itself was difficult to isolate as a driver. Coupled with managerial innovation, however, such technologies as bar code scanning, electronic data interchange, and warehouse management software led to Wal-Mart and its supplier network helping to generate a substantial portion of that productivity increase. With 27% market share in the mid-1990s and a 48% productivity advantage over its peers, Wal-Mart's overall impact moved the aggregate U.S. productivity needle all by itself.8

While it's early and the large-scale managerial innovation for developing world supply chains is still primarily in the future, some examples are already showing up:

- In India, mobile phone calls are valuable even when the recipient does not pick up. The “missed call”* message on the phone conveys ample information at no cost since a call was not completed. When a businessman finishes a meeting, for example, he calls the taxi driver who had dropped him and waited, who does not answer but knows to pull the car to the front door of the meeting place.

- DHL, the global logistics firm, is experimenting with social networks as the “last mile” for package delivery in crowded urban environments. If a woman is taking public transit from location X to location Y, would she mind carrying a small parcel along in the trial bring. BUDDY program? Initial indications are positive, particularly in places with high carbon dioxide footprints and strong civic awareness.9 Given that supply chains in South America include burros to take goods into poor neighborhoods, for example, overlaying social networks with logistics networks might work in some cities.

- Surveys in Africa found that something as simple as ordering replenishment of dwindling supplies via mobile phone should improve the percentage of stockouts in both consumer and business-to-business transactions. In addition, in line with the search costs mentioned earlier, low-cost suppliers are more easily identified, particularly by small business owners. Previously, replenishment often required travel to place an order. Finally in the world of small services business, many types of tradespeople found that 24-hour access was an important facet of their business.10

Mobile Phone Industry Impact

Just as the wireline telephone companies were often dominant players in their countries' economies, wireless companies generate noteworthy impact in the countries in which they operate. Wireless providers in Kenya, for example, employ more than 3,000 people directly.11 In Senegal, while wireless officially employed only 415 people in 2007, 30,000 people worked in Internet cafés, call centers, and the like.12 In addition, building a wireless network often requires capital investment in power generation and transmission, wireline backhaul networks, roads, rights-of-way, cell towers, billing and switching centers, and/or satellite uplinks. New businesses need legal determinations, business loans, real estate, and other services. The sum of all those categories of impact will certainly have increased in the intervening years in many developing countries.

Once again, numbers, even when available, do not tell the whole story. Mobile phones are changing the role of women in economies across the world, as when some daring Saudi Arabian women took to the roads in June 2011, driving cars as a form of social protest. Just as groups of women play a leading role in microfinance, they often help organize and run phone-sharing businesses in rural villages.13 In Bangladesh, 50,000 women were estimated to make their living as “phone ladies” in 2002, a number that grew to 220,000 by 2008.14

Even in the poorest countries, a support industry for mobile phones has emerged. Given the low penetration of electricity, for example, enterprising businesses have emerged to charge mobile phones by transporting them to nearly villages or by building charging stations from car batteries or other apparatuses. Repairing is another frequent business opportunity: The hacking skill of a street vendor is often impressive, particularly when many mobile devices are designed not to be repaired, much less by someone who's possibly illiterate, self-taught, and lacks access to factory tools, software, and documentation. Whole physical shopping areas have emerged for a wide variety of mobile-related services in such cities as Kabul, Cairo, Mumbai, and elsewhere.15

Risk Mitigation

Aker and Mbiti say little other than that mobility helps reinforce the vitality of kinship networks, which has important roles for both the economy and society of many African countries. Hearing about impending weather would be another example for mobility-conferred advantage for farmers or other people exposed to the elements. Informal reference checks (“Does this person show up for work reliably?” “Does this customer pay her bills on time?”) can become practical only in a mobile environment, particularly when written literacy may be limited. Penn State University's WishVast project in Kenya is an example of trying to use mobility to increase trust among potential economic participants who may lack kinship connections but wish to do business.16

Kinship networks in migratory cultures use mobility in complex ways. Women who grew accustomed to a certain degree of freedom while male heads of households left home for seasonal work, for example, now often have mobile phones with no balance—and thus no outbound calling—on which they get calls from the physically absent but emotionally very present male.17 Mobile communications is changing gender relations in many other ways as well, as we will see.

Transparency can do more than help families and householders. The prospect of election monitoring, for example, should decrease corruption, ideally improving the place of the rule of law, enforceability of contracts, and other preconditions for economic advancement. Ushahidi, Swahili for “witness,” is an open-source mapping and coordination platform first used in the 2008 Kenyan elections but since adapted to a wide variety of crisis-monitoring applications. In Mexico, for example, it was the basis for a vote fraud-monitoring tool called Cuidemos el Voto, or “Let's protect the vote together.” Ushahidi has also been deployed in Haiti, in Japan, and in various countries during the swine flu outbreak. Wired applications would never have had the same impact or the same portability.

Similarly, controversy surrounds the role of mobile phones in the so-called Arab Spring of 2011, when 11 countries experienced major protests, civil uprisings, or a change of regime in the span of only six months or so. The Egyptian unit of Vodafone, through its advertising agency JWT, posted a video claiming it was the catalyst for the uprising that culminated in the removal of President Hosni Mubarak. Egyptian radicals claimed in response that political factors were far more important than any commercial representations of what JWT called “Our Power.”18 The issues are big and complicated, but in short, to say that mobile phones aid in risk mitigation only at the household level understates the case.

Apps for Change*

As The Economist clearly pointed out, mobility is making a bigger difference in the developing world than it is in OECD countries, where it is far from trivial. But rather than Facebook, photo-sharing, or Angry Birds, the apps that matter in Africa, India, and elsewhere affect life expectancy, income per household, and the survival of democracy. In these areas, innovation in Africa and elsewhere is actually outpacing what is possible where more established alternatives to mobility—such as clinics, branch banks, or long-standing rule of law—have become part of the landscape. Indeed, a wide body of thought and practice is springing up around the notion of “reverse innovation” or its relative, “frugal innovation,” in which new products and services are designed for the special needs of emerging markets rather than being old, stripped-down, or ill-fitting versions of offers first seen in the United States, wealthy parts of Australasia, or Europe.19 Reverse innovation need not involve telecommunications—important new marketing practices involve smaller packaging for soap, for example—but clearly some exciting possibilities ride on the wireless airwaves.

The entire notion of a semiopen platform on which third-party applications can be developed is new; before 2008, getting software onto a cellular carrier's devices was difficult. Revenue sharing, security, bandwidth limitations, time to market, and a lack of unifying standards meant that few start-ups dared develop for the mobile phone or, more precisely, dozens of them: Button location, screen size and resolution, programming language, and localization of language and currency posed daunting technical problems even before questions of revenue, marketing, sales, and customer service were brought into the discussion.

Even without looking at the smartphone application explosion on Android and Apple, clever use of text messaging and other rudimentary data tools is making possible substantial gains in many areas: Most mobile phones in the developing world lack large screens and powerful data capabilities, as do the carrier networks in the latter instance. Two examples follow.

Mobile Money

Mobile financial applications, commonly known as m-money or m-banking, came to market in 2005 in several developing countries. Specifics vary: The application might come from a mobile carrier, a bank, or a joint effort; it might allow international money transfers or not; payment and storage of value options vary. According to Mobile Money Live, 20 million people in developing countries should have access by 2012.20

The basic functionality generally allows mobile subscribers or banking customers to store value in an account accessible by the handset, convert cash in and out of the stored value account, and transfer value between users by using a set of text messages, menu commands, and personal identification numbers (PINs).

As with Ushahidi, Kenya is leading the way. Safaricom's M-Pesa mobile money program launched in 2007,* with rapid uptake: About two years later, roughly 40 percent of Kenyans had already used the service to send or receive money. A popular feature is remittance from Kenyans abroad: M-Pesa allows someone in England, say, to send part of his or her paycheck home, at rates lower than Western Union, with greater coverage. Within Kenya, M-Pesa charged roughly 60% less than the post office for a simple transfer.

According to the carrier, in only two years, the cumulative value of the money transferred via M-Pesa was over $3.7 billion—nearly 10 percent of Kenya's annual gross domestic product. A fascinating question relates to whether M-Pesa is a mobile wallet or a mobile bank: It began as a transfer mechanism but now offers seamless links to interest-paying savings accounts. More questions relate to whether groups or individuals will change their saving or spending habits and whether various forms of fraud might slow the rapid growth of the service. As microfinance evolves, entities such as post offices will likely emerge as partners with carriers, development agencies, and other trusted entities to build capability further.

Side Effects of Mobile Money: Afghanistan

Afghanistan in 2001 had little infrastructure and no banking system; all transactions were conducted in cash at the time that American troops were deployed to the country. As of 2010, 97% of the country remains “unbanked,” but mobile money is proving to reduce corruption. The country has a teledensity approaching 50: 12 million cell phones in country of 28 million.

According to two former U.S. Army officers, one of whom served in Afghanistan (the other was in Iraq):

In 2009, the Afghan National Police began a test to pay salaries through mobile telephones rather than in cash. It immediately found that at least 10% of its payments had been going to ghost policemen who didn't exist; middlemen in the police hierarchy were pocketing the difference. Salaries for Afghan police and soldiers are calculated to be competitive with Taliban salaries, but beat cops and deployed soldiers had been receiving only a fraction of the amount paid by U.S. taxpayers because of corruption in the payment system. Most Afghan cops assumed that they had been given a significant raise when, in fact, they simply received their full pay for the first time—over the phone.21

Mobile Health

Given the state of healthcare in much of the developing world, replicating western methods will have only limited success. Decentralized approaches, peer-to-peer practices, and remote diagnostics and treatment all show great promise. Thus far, many health initiatives are philanthropically funded, but a new generation of indigenous entrepreneurs is launching a series of home-grown applications in the field of so-called m-health.

Data collection is one prime opportunity. Given the state of health statistics, rapid knowledge of infectious outbreaks, for example, can deliver significant benefits to patients, caregivers, and aid organizations. Basic information provision is another opportunity. HIV-positive patients in several African countries receive text messages reminding them about their medication schedule. University student Josh Nesbit built a simple SMS application for health-delivery workers in Malawi in 2007 that merged with other efforts to become Medic Mobile, an open-source platform helping to provide a management layer for information gathering, patient follow-up, and other nontherapeutic aspects of healthcare: Time savings from not having to walk miles to report symptoms or coordinate treatment amounted to thousands of hours in the pilot tests.22

Bright Simons is a Ghanaian entrepreneur who developed mPedigree, a simple text-based system for identifying counterfeit pharmaceuticals. Globally, an estimated 10% to 25% of all drugs sold are fake, but in some developing countries, the number can reach 80%, according to the World Health Organization. With mPedigree, a scratch-off panel on the packaging reveals a number code. The patient texts the number to a validation site, which signals whether the number is legitimate. As of mid-2011, the program was running in Ghana, India, Rwanda, and the Philippines.23

Sensors of many shapes and sizes are being coupled to mobile phones for remote diagnosis and monitoring. Mobile instruments able to measure everything from electrocardiograms, to blood slides, to blood pressure are being tested; remote access to even basics such as body weight and temperature has value and represents an improvement over the current situation in which a caregiver can be hundreds of miles away. Just for comparison, Germany has 3.4 doctors for 1,000 citizens; Kenya has 1.4 for every 10,000 people.

Looking Ahead

Mobility in the developing world represents several things. First, it is both an instance of and a platform for frugal innovation. Second, it is emerging in cultural ways that differ from the path to mobility in the OECD countries, given that landlines in many countries were nearly nonexistent. The overlay of cellular networks on top of tribal, kin, and other networks will be fascinating to watch and to learn from. Third, the difference between applications that range from the trivial to the helpful in the West and the truly life-altering possibilities presented by job hunting, agricultural price discovery, and healthcare provision on the mobile net is substantial: Rarely can anyone on a smartphone claim that the device is a matter of life-changing importance, whereas the millions of people connecting for the first time are voting with their precious income on exactly that fact.

Notes

1. Clay Shirky, “Half the World,” Clay Shirky's Writings About the Internet, September 3, 2002, www.shirky.com/writings/half_the_world.html.

2. “A Special Report on Telecoms in Emerging Markets: Mobile Marvels,” The Economist, September 24, 2009, www.economist.com/node/14483896.

3. International Telecommunications Union, 2010 World Telecommunication/ICT Development Report, www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/opb/ind/D-IND-WTDR-2010-PDF-E.pdf.

4. Tim Kelly, “Twenty Years of Measuring the Missing Link,” www.itu.int/osg/spu/sfo/missinglink/kelly-20-years.pdf.

5. “Huawei Aims to Beat Ericsson in New Gear Orders,” Bloomberg Businessweek, November 17, 2010, www.businessweek.com/news/2010-11-17/huawei-aims-to-beat-ericsson-in-new-gear-orders.html.

6. Jenny Aker and Isaac Mbiti, “Mobile Phones and Economic Development in Africa,” Center for Global Development Working Paper 211 (June, 1 2010): 8, www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/1424175/.

7. Robert Jensen, “The Digital Provide: Information (Technology), Market Performance, and Welfare in the South Indian Fisheries Sector,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122, no. 3 (2007): pp 879–924, http://qje.oxfordjournals.org/content/122/3/879.abstract-fn-1. See also “To Do with the Price of Fish,” The Economist, May 10, 2007, www.economist.com/node/9149142.

8. McKinsey Global Institute, “US Productivity Growth 1995–2000: Understanding the Contribution of Information Technology Relative to Other Factors,” October 2001, www.mckinsey.com/mgi/publications/us/index.asp.

9. www.forbes.com/sites/billbarol/2010/11/26/bring-buddy-dhl-crowdsources-your-grandma/ www.livinglabs-global.com/showcase/showcase/392/bringbuddy.aspx.

10. Jonathan Samuel, Niraj Shah, and Wenona Hadingham, “Mobile Communications in South Africa, Tanzania and Egypt: Results from Community and Business Surveys,” Vodafone Policy Papers Series no. 3 (March 2005): 44–52.

11. Timothy Waema, Catherine Adeya, and Margaret Nyambura Ndung'u, Kenya ICT Sector Performance Review 2009–2010, researchICTAfrica.net, www.researchictafrica.net/publications/Policy_Paper_Series_Towards_Evidence-based_ICT_Policy_and_Regulation_-_Volume_2/Vol%202%20Paper%2010%20-%20Kenya%20ICT%20Sector%20Performance%20Review%202010.pdf.

12. Mamadou Alhadji LY, Senegal ICT Sector Performance Review 2009/2010, resear-chICTAfrica.net, p. 27, www.researchictafrica.net/publications/Policy_Paper_Series_Towards_Evidence-based_ICT_Policy_and_Regulation_-_Volume_2/Vol_2_Paper_20_-_Senegal_ICT_Sector_Performance_Review_2010_English_Version.pdf.

13. “Grameen Phone—Turning Local Women into Telecom Entrepreneurs,” http://social-enterprise.posterous.com/grameen-phone-turning-local-women-into-teleco.

14. Alfred Hermida, “Mobile Money Spinner for Women,” BBC, October 8, 2002, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/2254231.stm.

15. For an example, see the work of smartphone ethnographer Jan Chipchase at http://janchipchase.com/2006/10/value-added-services/.

16. http://sites.google.com/site/thewishvastproject/.

17. I am indebted to my student Amanda Hahnel for relating this insight from her internship in India.

18. “Vodafone Denies Using Arab Spring to Sell Phones,” Channel 4 news, June 3, 2011, www.channel4.com/news/vodafone-denies-using-arab-spring-to-sell-phones.

19. See, for example, “First Break All the Rules: The Charms of Frugal Innovation,” The Economist, April 15, 2010, www.economist.com/node/15879359.

20. www.wirelessintelligence.com/mobile-money/.

21. Dan Rice and Guy Filippelli, “One Cell Phone at a Time: Countering Corruption in Afghanistan,” September 2, 2010 blog post, http://smallwarsjournal.com/blog/2010/09/one-cell-phone-at-a-time-count/.

22. N. Mahmud, J. Rodriguez, and J. Nesbit, “A Text Message-Based Intervention to Bridge the Healthcare Communication Gap in the Rural Developing World,” Journal of Technology and Health Care 18, no. 2 (2010): 137–144.

23. www.mpedigree.net/mpedigree/index.php.

*In South Africa, the same practice is called “beeping” and may have different meanings attached to the number of rings that precede the disconnection.

*I borrow the title from a Nokia-sponsored competition for which I was a judge. The winning idea activated one's social network in the event of need for blood donation.

*With help from a U.K. development organization, the Department for International Development; Safaricom is part of U.K.-based Vodafone: www.dfid.gov.uk/Global-Issues/Emerging-policy/Wealth-creation-private-sector/Finance/.