CHAPTER 13

Work

What constitutes work, where it happens, who does it, and how it is rewarded are all in flux. Multiple macro-level forces are responsible, and a full treatment of the question is out of our current scope. The interaction between people's work and their technologies has always been important, however, so some attention to the question is in line here.

The Big Picture: Macro Trends

Ever since its founding, the United States has steadily produced more and more economic value. In 1900, U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, in current dollars, was $268. By 1950, that figure had multiplied seven times to about $2,000. Between 1950 and 2000, the multiple was 18. To put that per capita figure in perspective, real GDP rose from $294 billion to $9,817 billion: a 33-fold increase. (The ratio of 18 to 33 suggests that total population nearly doubled, which it did, from 151 million to 281 million.)

The role of agriculture has changed in surprising ways. The number of farms in the United States in 1950 was almost the same as in 1900, a little over five and a half million after having peaked in the mid-1930s. By 2000, the number of farms had dropped to 2.2 million, but the average size, possibly reflecting the rise of organic farms, was actually dropping from its high in 1994. The amount of total acreage in farms reached its peak in 1953: For all the talk of urbanization in the late nineteenth century, it turns out that in 1950, the United States was still robustly rural, in land use terms anyway.

The surprising amount of farm acreage belied a strong population shift, however. In 1900, 41 percent of the U.S. workforce was employed in agriculture. The number fell to 16% in 1945 and to less than 2% in 2000, with most workers part time. Agriculture was less than 1% of GDP by that time, a ninth of what it had been in 1945.1

Where did people go when they left the farms, which were mostly located in the Midwest? South and west, of course: The 13 states that constitute the Census Bureau's West region (every state west of Texas) combined to grow from 13% of U.S. population in 1950 to 22.5% 50 years later. Surprisingly, the South increased only from 31% to 36%. Before talking about macroeconomic effects of computing, one has to appreciate the impact of other technologies, such as air conditioning, on where people live: Such fast-growing states as Virginia, Georgia, Texas, and Arizona can be uncomfortable and unhealthy without climate control. Air conditioning in turn raises the importance of electric power, which was still a novelty in the rural South in 1950.

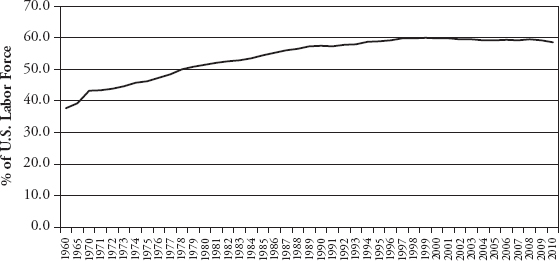

Along with internal migration, the second half of the twentieth century was marked by broad social change: Political and economic involvement by women became broader, in terms of numbers, and deeper, in terms of impact. Women doubled their participation in the workforce, from 30% to 60% (see Figure 13.1, which begins at 1960), and now women often, but not routinely, hold seats as chief executives, senators, Supreme Court justices, and astronauts. Women also constitute well over half of the college population only a generation after having gained admittance to the leading private universities. The United States is also a much older nation than in 1950. Life expectancy at birth has risen from 68 to 77. Both of these trends relate closely to changes in medical technology and, for women, birth control. It will require further study to determine how much the increase in life expectancy relates to computing: Trends in immunization, smoking, nutrition, and cardiac interventions are, I suspect, far more important.

FIGURE 13.1 Female Participation in the U.S. Labor Force, 1960–2010

Source: U.S. Census.

In demographic terms, the automobile stands out among technologies with major impact. The pervasiveness of its influence tracks closely with the invention and habitation of the suburb—a term that did not exist at the time of the 1900 census. But from 1910 until 1950, when the percentage of population in suburbs more than tripled, to 23% of the population, the rise of the automobile literally reshaped the landscape. In the 50 years of the information age that constitutes our focus here, the percentage of population in suburbs more than doubled: Fully half the U.S. population now lives in suburbs, a striking testimony to the geographic transition caused by the automobile.

Shifting from residence to occupation, manufacturing grew at agriculture's expense, as the air conditioning—and automobile-related figures would suggest. But while manufacturing employment peaked in 1979 at over 19 million jobs, it had been declining since 1953 as a percentage of total employment: The drop, from 1 job in 3 to 1 in 12, constitutes another defining characteristic of the past half century.

Where

As the world and the North American economy become more virtual, businesses are encountering new layers of the paradox of place. An Internet connection can link two people by voice, text chat, or video almost any-where in the developed world, with many developing nations catching up fast. As coordination costs drop, work can more easily migrate to low-wage locales. For product work, that migration implies moving factories. More recently, services from radiology, to call centers, to coding have begun to be outsourced and/or offshored. One shorthand prediction calls China the emerging factory to the world, with India its back office. But costs are only one aspect of the tension between place and space.

The dynamics of place affect many business choices. Locating a factory or distribution center near a prime customer, as Dell's suppliers have near Austin, tightens tolerances on deliveries and can support higher levels of customer service. Moving research and development operations near major university centers, as Novartis and other companies have around MIT and Harvard, can impose high wage scales onto employers. For employers outside those sectors that do not require such specialized (and localized) expertise, Massachusetts is undesirable as a new business destination, and high housing prices are noted as a major deterrent to job growth there.

Richard Florida's influential book, The Rise of the Creative Class,2 argued that rather than lobbying with tax breaks and other inducements for large Toyota or Mercedes factories, states and localities in search of jobs should instead seek to attract creative individuals. Because these people can do such tasks as stock picking, screenwriting, or software architecture essentially any-where, they tend to migrate to places with good music and culture, interesting restaurants and diverse populations, and strong educational institutions. After arriving, they put their skills and networks together and make jobs for themselves and others. Florida's examples—San Francisco, Minneapolis, and Pittsburgh, among many others—appear to support his thesis. But another characteristic joins these places: Essential but noncreative people such as plumbers, police officers, teachers, and support personnel can get priced out of cities that he lists as exemplars.

The commuting distance for the working people who make creative centers work is increasing. These jobs matter for quality of life. Places like Marin County, California, and Greenwich, Connecticut, are undeniably appealing in many ways. But what happens when auto repair shops and dry cleaners can't survive? Many skilled jobs can be performed remotely, to be sure, but how can affluent, attractive locales keep nurses, delivery truck drivers, and other people whose skills are in short supply right now? Societies at all stages of economic development are experiencing the effects of selective job mobility in the aftermath of the Internet and cellular telephony revolutions.

There's another recent phenomenon of skills and place: Workers in skilled jobs (such as information technology) often are trained at academic centers far from an employer base. Kathy Brittain White served as chief information officer at Cardinal Health before founding Rural Sourcing, an American company that seeks to provide the cost savings of displacing work to a lower-cost, lower-wage environment. Her twist to the offshore model is locating programming and support centers in such places as Greenville, North Carolina—home to East Carolina University, which now enrolls more than 20,000 students.

Rural Sourcing uses networks to take relative isolation and turn it into comparative advantage. In a parallel move, Google opened major facilities in New York, Ann Arbor, and Pittsburgh, the latter because of Carnegie Mellon's powerful computer science presence. In the nineteenth century, proximity to water power made New England mill towns economic engines for the shoe and textile industries that were centered there. Detroit built on access to freighter ports that delivered the bulk materials for the auto industry (and on the venture capital provided by timber barons enriched by the need for mass-produced wooden furniture and building supplies).

Today, university towns are vying to attract knowledge-intensive industries, but what are the other sources of advantage for the next 25 years? If home-schooling continues its strong rise in popularity, more people might move to places without demonstrably good school systems. Telemedicine could reduce the urge to live near major medical centers. Long commutes have multiple negative side effects,3 so towns with light traffic will likely increase in appeal. Online shopping addresses the concern about the lack of quality retailers in a given place. Many such wildcards remain to be played.

Far from the fields that White is cultivating, the place of cities remains contested and important. The public intellectual Jane Jacobs, a powerful voice in twentieth-century American urbanism, lacked academic credentials but argued for the organic aspects of cities. She opposed zoning, for example, reasoning that people should be able to live near their work. Her energy and ideas helped defeat some of the more sweeping “urban renewal” efforts of the 1950s and 1960s as citizen movements began to oppose the bulldozing of neighborhoods that happened to lie in the path of expressways. Criticized for advocating gentrification, she herself was priced out of Greenwich Village in the 1990s and found Toronto more hospitable to her thinking (and financial means) than her adopted New York, which she tended to idealize. Jacobs's crusade served as a reminder that the cost of the suburban model can be measured only partially in fuel consumption or rising commute times.4

The best-selling author Thomas Friedman famously asserted that “the world is flat” in his book of that name: Anyone any-where can participate in the global economy via various connections.5 Florida replied that, rather than being flat, “the world is spiky” in that concentrations of talent and resources matter more than the ubiquitous access Friedman chronicles. Instead of forcing these two arguments into false opposition, it is useful to use the insights of both to examine how connection is changing work, culture, and economics.

The uncomfortable juxtaposition of globalization and locality is not a new phenomenon—just look at England in the twilight of empire. If people earn money only from local sources but spend it on goods and, increasingly, services from “away,” eventually money needs to come back into the locality: Just as a multicrop family farm is no longer a viable option for many, neither is a self-sustaining local economy. Somehow, money needs to come in as well as leave, and the current trade imbalance and federal debt levels both ratchet up that imperative.

Outputs

One of the great but difficult thinkers of the twentieth century, the economist and satirist Thorstein Veblen, wrestled with people's interconnected relationships both to what Karl Marx* named the means of production and to the consumption of mass-produced goods. Veblen attributed a nobility to work that he called the “instinct of workmanship”: Man the maker “has a sense of the merit of serviceability or efficiency and of the demerit of futility, waste, or incapacity.” By contrast, what Veblen memorably named “conspicuous consumption” was “ceremonial” in that it sorted people by reputation, the basis of an ultimately unwinnable competition.6

By mentioning Veblen I raise an unanswerable question. The people who buy mass-produced stuff, often called “consumers,” want in some deep-rooted way to shape their environment beyond just piling up purchased goods. How much people want to stand out as unique, and how much they want to create something tangible, is of course impossible to differentiate or quantify, and sometimes an artifact embodies both consumption (or conspicuousness) and workmanship. But the current business landscape provides too many examples for this to be a fad: There's something very potent afoot in the rise of cooking shows, in “maker” culture, and in such phenomena as Habitat for Humanity.

Harvard professor Daniel Bell identified what he called the coming of postindustrial society more than 30 years ago, but it took the Internet for us to feel what it's like to transcend factories the way factories had trumped farming roughly a half-century before he wrote. As information about stuff becomes more valuable than stuff itself, the activities of creation and individualization take on a new shape in both tangible and intangible realms. First, in an economy largely devoted to nonessentials, there exists some (essential?) desire to make meaningful stuff, not just ideas and decisions. Second, we can see a broad-based quest to differentiate oneself by differentiating one's stuff. Finally, there's a sense of entitlement, related to the “affordable luxury” trend embodied by Starbucks, itself a primo customizer: I want the best (of something) made for me because I'm worth it.

Skills

Like many others, I persist in believing that the transformative power of computing lies ahead of us. Whether it's in genome-aware therapeutics, or rich-media self-publishing, or low-cost avionics that make small jets feasible as air taxis, the majority of digital innovations that will remake the economy are as yet uncommercialized. And compared to such landmarks as the invention of the steam engine or the factory system, our 50 years of computing represents enormous change in short time. The daunting fact is that the change to come looms even bigger.

In the interim, the demands of a digital economy contribute to complex and difficult demographic issues: skill- and education-based bifurcation, along with a changing racial composition. In the middle of the twentieth century, factory work paid better than farm work and was widely accessible at the low end. People could leave farms, enter manufacturing with no or few skills and little education, and stay afloat. A further correlate here is decentralization: Factory work collects resources in one place while services industries (and powerful communications networks) disperse them. What are the consequences of the growth of the South and West without a heavy reliance on industrial centers such as Milwaukee, Pittsburgh, or Detroit?

Prior to and during World War II, the internal migration of black Americans from the rural South to the industrial Midwest led to such varied changes as a rebirth of popular music, a power base for the Democratic party, and the rise of a black middle class. Only one or two cultural hops separate Henry Ford from Diana Ross, Lyndon Johnson, and the Cosby Show. Look a little closer and you see the Rolling Stones, Magic Johnson's National Basketball Association, and Oprah Winfrey, who was born in Mississippi but made her name in Chicago.

Now the opposite dynamic is at work as manufacturing automation and globalization release workers to take jobs in lower-paying categories, such as hospital food service or big-box retail; in raw numbers, the biggest job creators for several years after 2001 were Home Depot and Lowe's, and of course Wal-Mart's net role in employment remains hotly disputed. Retail and other services often teach their workers how to use automated systems but rarely prepare them to enter a better-paying sector. How the shift to services interrelates with America's racial picture, including of course the emerging Hispanic majority, will be critically important to track.

As the CIA's World Factbook puts the issue:

The onrush of technology largely explains the gradual development of a “two-tier labor market” in which those at the bottom lack the education and the professional/technical skills of those at the top and, more and more, fail to get comparable pay raises, health insurance coverage, and other benefits. Since 1975, practically all the gains in household income have gone to the top 20% of households.7

The consequences of such a bifurcated populace touch sociology, politics, economics, and even ethics, so I won't even attempt a summary comment. Perhaps this trend is the result of moving farther and farther from a subsistence economy. One of the things we'll be tracking as this research progresses is the changing composition of the economy away from food, clothing, and shelter to transportation, entertainment, and other luxuries. The interplay of rapid population growth, rapid increase in the amount of livable and available real estate, wider education, suburbanization, and the shift to a services economy all contribute to making the task of assessing information's role highly problematic.

Work

What have computers and the digital revolution done to work? Answers vary considerably. In 1992, Robert Reich (later Bill Clinton's secretary of labor) devised a tripartite schema to classify the workers of the world, seeing global workforces as already having been divided into three groups: routine producers (e.g., call center reps or assembly-line workers), inperson servers (waiters or nurses), and symbolic analysts who manipulate pure information for large profits (Wall Street quants). Digitization in the service of high leverage made the “symbolic analysts” rich and skewed income distribution. Seeing the relation of rich to poor less than 20 years later, Reich may have been onto something crucial, but his tepid solution—training and education—has failed to shift the terms of the debate, partly because school systems change incredibly slowly and require levels (and types) of investment that are for a number of reasons politically impossible in the United States.

A decade later, Richard Florida defined the engine of the new economy as the “creative class,” 38 million of whom comprised 30% of the workforce. For the winners, digitization empowers flexible work that gives great meaning:

In this new world, it is no longer the organizations we work for, churches, neighborhoods, or even family ties that define us. Instead, we do this ourselves, defining our identities along the varied dimensions of our creativity. Other aspects of our lives—what we consume, new forms of leisure and recreation, efforts at community-building—then organize themselves around this process of identity creation.8

Surely 30% of the workforce can't work at ad agencies or Disney. No, says Florida:

I define the core of the Creative Class to include people in science and engineering, architecture and design, education, arts, music and entertainment, whose economic function is to create new ideas, new technology and/or new creative content. Around the core, the Creative Class also includes a broader group of creative professionals in business and finance, law, health care and related fields.

The core and the doughnut are linked not by geography or income or skills but by a value set:

[A]ll members of the Creative Class—whether they are artists or engineers, musicians or computer scientists, writers or entrepreneurs—share a common creative ethos that values creativity, individuality, difference and merit. For the members of the Creative Class, every aspect and every manifestation of creativity—technological, cultural and economic—is interlinked and inseparable.9

Whatever its relation to life as most people know it, Florida's book resonated. It led to a thriving consulting business helping cities attempt to become more economically competitive. How? Not with tax incentives for auto plants but by luring more of those 38 million people with more tolerant attitudes, better mass transit, more authentic espresso bars, and the other factors that separate Toronto from Topeka or Minneapolis from Modesto.

In the intervening years, however, much has happened to cast doubt on Florida's vision of the future. What exactly do those creative people do to help the U.S. balance of trade deficit? Movies, mergers and acquisition deals, and Microsoft all contribute to exports, but not to the degree that farm goods do, and none approaches the aerospace sector's international impact. What happens when offshore competition threatens large numbers of those 38 million jobs? Legal research, programming, equity analysis, and even moviemaking and distance learning are already being produced and delivered from afar in lower-wage settings—what will be next?

More fundamentally, just how creative are those 38 million people? Job titles can be deceiving: A good friend of mine was for a time an architect at HOK, the sports division of which has given us such modern monuments as Camden Yards in Baltimore or AT&T Park in San Francisco. What was our young Howard Roark's creative contribution? Bathrooms for the Hong Kong airport.

Matthew Crawford, in a recent book called Shop Class as Soulcraft, raises similar doubts.10 Beginning with the observation that many high schools are dropping shop class because it fails to train people to be symbolic analysts, Crawford challenges the reader to think deeply about the value of work. Because it often lacks real output, modern bureaucratic life, defined largely by office automation, can be unfulfilling. In contrast to the carpenter whose windows can't leak, or the farmer who feeds people with tangible crops or livestock, the office worker (creative or not) lacks physical boundaries to define the real from the artificial or the possible from the impossible.

As Crawford notes, quoting Robert Jackall's Moral Mazes (now 20 years old), office memos are crafted to be unincriminating no matter how subsequent events play out. Taking a firm stand is often seen as career limiting, so most eventualities remain unforeclosed; every statement is hedged. Along similar lines, after receiving a PhD from the University of Chicago, Crawford works for a think tank generating position papers that begin not with the facts but with a position, reasoning backward to convenient truths. It is intellectual bad faith of the first order, and he quits. Worse yet, in his circles of occupational hell, are jobs built on teams with their indeterminate appropriation of credit and blame, along with the human resource-driven trust-building games that frequently pass the point of self-parody.

In contrast, the author points to his work as a motorcycle mechanic. No symbolic analyst he, Crawford confronts physical limits every day and pays a steep price for failure. If he drops a washer into a crankcase, at times he must tear down the engine block to retrieve it and cannot in good conscience bill the customer for all of the hours involved. Mistakes, stupid or otherwise, have concrete consequences. On the positive side of the ledger, when he fixes a broken fork, returns a dead bike to life after 10 years off the road, or hears the particular sound of a well-tuned engine, he derives great satisfaction. He also contends that mechanical work can be more intellectually engaging than knowledge work, implicitly challenging Florida's new world order.

In some measure, we are fighting a new stage of the philosophical battle joined by Rene Descartes (1596–1650), who separated thought from emotion and thereby physicality. Craft work (fixing or building things) joins the practice of medicine, certainly, but also full-throated singing as moments where mind and body unite. Sport constitutes another similar realm, as does cooking, the recent enthusiasm for which might be seen as a reassertion of the satisfaction that can come only when head, hands, and palate unite in a primal act—that of feeding another person. Compare the gestalt of today's many cooking shows to the treatment of the modern workplace in current television programming and the contrast is obvious: Julia Child, enshrined at the Smithsonian, is a hero while cubicle America's cultural icon has yet to transcend the comic strip Dilbert.

Shop Class as Soulcraft also makes the pragmatic point that fixing things cannot be offshored; one can make a healthy living as an electrician, for example, or an auto repairman. Last time I was in for an oil change, my mechanic was telling me about one manufacturer's switch to a fiber-optic system bus—he knows more computer networking than I ever will. To service appliances or furnaces today is to have studied hundreds of hours of digital control and monitoring technology. High schools, however, generally operate under the principle that college-bound students will have better careers than those who work in jobs that require mere training. But what economists call the education premium can no longer be assured today, much less in 50 years when today's high school graduates will almost certainly still be working.

There's also the matter of permanence. As Crawford notes, many of today's appliances are built to break and not be repaired. How does today's work give people the opportunity to build something that will last beyond their life span? For teachers, this is one of the true joys of the profession. For most knowledge workers, the answer is less clear. True craftsmen raise a red flag about throw-away work. As Michael Ruhlman, known more for his books on chefs and cooking, reported in a book on wooden boats:

I asked Gannon why wooden boats were important to him—why had he devoted his life to them? Ross seemed surprised by my apparent ignorance regarding what to him was plain, and his blazing eyes burned right through me.

“Do you want to teach your daughter [then three years old] that what you do, what you care about, is disposable?” he asked. “That you can throw your work away? It doesn't matter?”11

Whether in passing down the family farm or painting “& Sons” on the service van, craft work is often connected to future generations that bureaucracy cannot sustain. This lack of long-term continuity may be another reason why the modern office lacks heroic images in popular culture.

Looking Ahead

Tom Malone of MIT explores the future landscape of work through the lens of its institutions. In his 2004 book, The Future of Work, he lays out various scenarios primarily concerned with the coordination and collaborative facets of organizations.12 He sees the future as more decentralized, less hierarchical, and more democratic. If it comes to pass, Malone's vision foreshadows the demise of The Offices Michael Scott and his kin. Pettiness and incompetence are eternal, however, so it is worth pondering both what will happen to a Michael in a Maloneite world and what manner of successor will emerge instead.

In the end of any analysis, work cannot be categorized with any precision. It is both universal and specifically grounded in time, place, and individual. It offers both rewards and challenges (some of which may overlap), utilizes groups and solo contributors, and defines us in multiple ways. The diversity of the perspectives mentioned here is itself incomplete, missing, for example, the perspective of the Japanese salaryman, the unionized autoworker, or the classic professions of law or clergy (both of which themselves are in the midst of deep change). I have made no mention of wages, which are retreating in many settings. The appeal of Dan Pink's vision of Free Agent Nation (2002), for example, has been replaced by the reality of the less glamorous name for continuous partial employment: “temping.”

As to the question What have computers done to work?, the answer is probably less clear than it will be in another 25 years, when the changes to economies, workplaces, and individual performance will separate themselves from the end of the oil/automotive/steel age that wound down in the late twentieth century. The exciting news comes in the realization that the future of work is not yet defined, making it contingent on the attitudes and actions of many people.

Notes

1. Carolyn Dimitri, Anne Effland, and Neilson Conklin, “The 20th Century Transformation of U.S. Agriculture and Farm Policy,” U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Electronic Information Bulletin Number 3, June 2005, www.ers.usda.gov/publications/eib3/eib3.htm.

2. Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class: and How It's Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life (New York: Basic Books, 2002).

3. Annie Lowrey, “Your Commute Is Killing You: Long Commutes Cause Obesity, Neck Pain, Loneliness, Divorce, Stress, and Insomnia,” Slate, May 26, 2011, www.slate.com/id/2295603/.

4. “Jane Jacobs, Anatomiser of Cities, Died on April 24th, aged 89,” The Economist, May 11, 2006, www.economist.com/node/6910989.

5. Friedman, The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century (New York: Farrar Strass & Giroux, 2005).

6. For a brief introduction to Veblen, see The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics at www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Veblen.html. For more extended treatment, see John Patrick Diggins, The Bard of Savagery (New York: Seabury, 1978).

7. CIA World Factbook, www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/us.html.

8. Florida, Rise of the Creative Class, pp. 7–8.

9. Ibid., p. 8.

10. Matthew B. Crawford, Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry Into the Value of Work (New York: Penguin, 2009).

11. Michael Ruhlman, Wooden Boats: In Pursuit of the Perfect Craft at an American Boatyard (New York: Penguin, 2001), p. 7.

12. Thomas W. Malone, The Future of Work: How the New Order of Business Will Shape Your Organization, Your Management Style and Your Life (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004).

*German political philosopher and progenitor of social science, whose ideas underlie modern communism (1818–1883).