CHAPTER 18

Music Business Models

The business model disruption framework as it applies to music has multiple moving pieces: Tastes change, attitudes toward intellectual property sharing differ significantly by demographic, and the place of recorded music in modern life is also in a period of deep transition. The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), which began as a standards body, became perhaps the most disliked lobbying group in the country by suing music lovers, which was a curious strategy, to put it charitably. Music is a small but visible industry (moving and storage was about the same size, but Mayflower never had the Grammy Awards), and it was also disrupted early in the Internet's life cycle, before telecom or newspapers, for instance. How did technology-related events and trends disrupt the music industry's business model to such an extent that its trade association felt compelled to adopt such an extreme position?

Incumbent Model Pre-2000

It is tempting to say that Napster changed everything, and peer-to-peer (p2p) file sharing is clearly a hugely important factor in the media landscape. It is not the only factor, however, and a series of services have in fact disappeared, sometimes permanently: In addition to Napster, Pirate Bay and Limewire have been subject to legal challenges. But as we will see, the music industry business model had a number of problems before the Napster watershed.

Customer Value Proposition

The goal before the Internet era was to sell physical artifacts that carry music: cassettes, long-playing (LP) records, compact discs. As platforms evolved, record companies could sell the exact same content multiple times, which was one driving impetus behind the high-resolution formats that came to market in the late 1990s: Super Audio Compact Disc (SACD) and High Definition DVD (HD-DVD). Unfortunately for the record labels, at the same time that Napster and later the iPod popularized MP3 files, the audio-buying public was viewing SACD versus HD-DVD as a reprise of VHS-Betamax: People remembered buying machines that became worthless when the other standard emerged as dominant, making software, spare parts, and resale difficult. By the time Sony's SACD format won the standards war, the market had little enthusiasm for music players that required a new form of physical media.

Profit Formula

Record companies recognized million sellers with gold records as far back as 1942, but it was in the period between 1970 and 1980 that the industry saw huge sales of LPs: A handful of efforts from Michael Jackson, Pink Floyd, Fleetwood Mac, the Eagles, and other artists sold in excess of 40 million copies over their lifetime. For a number of reasons, labels sought a 10-million-seller rather than ten 1-million-unit milestones: The industry first became album driven (in that 8 to 12 songs were bundled into a 40-minute LP rather than being sold individually), then hit driven. The profit formula also was predicated on keeping artists in a disadvantaged position with regard to contract provisions and enforcement: Senator Orrin Hatch (a Utah Republican who has written more than 300 songs) once remarked that music is the only industry in which, after you pay off the mortgage, the bank still owns the house.1

Key Resources

Control of physical factories was essential: While pirate physical copies of LPs then CDs were available in some foreign countries, the complexity of manufacturing helped maintain the labels as an oligopoly. The labels viewed cassette taping with alarm in the 1970s, but the audio quality of tapes was inferior in most cases, as was the quality of the cover artwork, for which the LP format was ideally suited from a graphics perspective. Finally, the artist and repertoire function of discovering new bands was essential: Much like baseball scouts, certain individuals developed a track record in discovering successful new acts.

Key Processes

In addition to the supply chain of discovering talent, packaging albums, and distributing physical media, two other processes deserve mention. Touring was often an important tool for building support for a new release. Also, music is a prototypical information good insofar as it presents a sampling problem: The only way to know if you like a book, video game, movie, or song is to experience the artifact itself. Statistics, reviews, and word of mouth help, to be sure, but radio played a key role in solving the sampling problem for recorded music. Later, just at the dawn of the CD format, MTV pioneered the music video that performed a similar function. Getting a song onto radio and, later, cable television often made the difference between a hit and a miss. Not surprisingly, money and favors could be exchanged in this pursuit, most notoriously in the payola scandal that cost disc jockey Alan Freed (who coined the term “rock ‘n’ roll”) his career in the 1950s, but also as recently as 2005, when then New York attorney general Eliot Spitzer settled out of court with three major labels, each of which paid a multimillion-dollar penalty.

Technology Evolution and Industry's Response: The Case of Home Taping and MTV

In the late 1970s, the labels had succeeded in making disco music a perfect fit for the mass-distribution model. The problem was that the intense focus on the genre had run the industry into a cul-de-sac: As me-too acts multiplied, the American audience's appetite for disco dropped sharply, and there were few acts of other styles in the pipeline. Despite this saturation, the industry focused its public relations, legal, and lobbying efforts on stigmatizing and if possible outlawing the practice of cassette recording. One industry campaign featured a cassette-shaped skull and crossbones with the tagline “Home taping is killing music.” Rather than exploiting this new, popular technology, labels fought it. The RIAA's president claimed that for every album that was bought, another went unbought because of taping. The RIAA also claimed that 425 million hours of music were taped even though blank tape sales were only half of that total.

Record sales had fallen 11.4% in 1981 and were rumored to be headed for another double-digit decrease in 1982. That year Columbia Records alone fired 300 people from the label while such superstar acts as Blondie and Fleetwood Mac canceled tour dates.

Enter MTV, a venture launched in 1981 by Warner Communications, which sold it to Viacom in 1985. MTV introduced a new musical vocabulary including heavy doses of synthesizers and electronic drum machines into the American market, initially including British pop acts like Duran Duran and the Eurythmics that enjoyed huge success in the 1980s. The technology innovation of replacing or augmenting the top-40 single with a cable TV music video changed the promotion landscape dramatically and introduced fresh “inventory” into the supply side of the music pipeline. In the end, the “crisis” in the music industry was not the fault of the tapers—who did not cease and desist even as the industry subsequently logged unprecedented profits—but had to a large extent resulted from stagnation in musical innovation at the major labels.

Michael Jackson's Thriller LP is widely credited as the first release to consciously utilize the new MTV promotional medium (e.g., by hiring commercial directors to make music videos as mini-movies): It sold between 26 and 40 million copies, depending on who's counting. At the same time, MTV's technology further intensified the music business's blockbuster economics that are in part responsible for the current situation. Being able to pass video costs on to the performer allowed labels to avoid confronting the vast potential of the new medium while limiting risk.

Business Model Disruption Pre-Napster

The 1990s witnessed at least a dozen changes to the music industry business model that helped set the stage for the knockout punch that Napster delivered. Any one by itself was not crippling but, en masse, these changes shifted the foundations of the industry sufficiently that labels were unable to respond to the challenge of p2p, in large measure because the customer value proposition was perceived to be unfair to both consumers and artists, who continued to enjoy favorable fan response.

- Piracy had become an issue. As of 2001, about a quarter of CDs sold worldwide were suspected of being counterfeit. The ease of copying CDs on personal computers was one impetus for the SACD and HD-DVD formats, which incorporated copy protection schemes that, much like the DVD, would eventually have been broken anyway. At the turn of the century, the odds were less than 50% that a given CD was legitimate in such markets as China, Russia, and Brazil.

- As large-format retailers gained in scale in the 1990s, they did more to dictate what was stocked. Just as they did in other industries, Target, Best Buy, and Wal-Mart gained in power relative to their suppliers, in this case both the labels and independent “rack jobbers” who stocked mom-and-pop operations. Such music-centric chains as HMV, Tower, and Wherehouse disappeared entirely.

- Those large-format retailers helped shift an industry institution, the top-40 or Hot 100 list, to a more data-driven basis. In 1991, point-of-sale data replaced editors' phone calls to a few retail buddies. Garth Brooks was an instant beneficiary: Country music was found to be seriously underrepresented in the informal lists. Market research replaced taste and intuition in signing artists, leading to a homogenization of styles around a few themes, hip-hop and country among them.

- Another factor led to a lack of fresh new acts. Reselling consumers the same music they had liked years or decades earlier was profitable and easy, particularly given favorable royalty arrangements in contracts that did not anticipate emerging formats. Music industry revenue nearly doubled between 1989 and 1994, largely on the strength of back catalog sales.

- At the same time that nonmusic retailers increased their presence, radio was consolidating. Clear Channel came to own 11% of U.S. broadcast outlets but controlled 20% of ad revenue. Four broadcast groups controlled 63% of stations with a top-40 format. Once again, homogenization of musical genres, rather than diversity, was one outcome.

- Even as it struggled with its own business model, satellite radio challenged physical music providers for share of wallet. The extreme variety and high audio quality made Sirius and XM credible alternatives to owning a CD collection, particularly for automobile listening.

- MTV shifted its programming over time to the point where it seldom played new music videos. Meanwhile, the cost of producing a single music video, often borne by the artist, climbed to potentially more than $2 million.

- Touring became an attractive revenue stream, but it was also subject to industry consolidation. Eventually, the Ticketmaster-Live Nation merger of 2010 meant that venue owners confronted a powerful alliance of concert booking and ticketing entities that could dictate terms. Clear Channel also operated in this market segment, leading to charges that radio airplay was being used as a negotiating tactic with non-Clear Channel promoters.

- Recording artists won congressional support for an overturn of work-for-hire contact language that the RIAA had previously helped codify into law. The language would have had the effect of denying artists' claims to copyright, particularly as new formats emerged.

- The DVD, priced at about the same $16 point for which labels sold CDs, became the fastest-selling technology in U.S. history. In the four years after the format's launch in 1998, DVD players outsold CD players 3:1.

- In another legal setback, the labels' practice of setting minimum advertised prices (MAPs; very close to price fixing) was found to be illegal in 2003. Consumers were supposed to receive small checks, and the labels were supposed to donate music to nonprofit institutions. The loss was small monetarily, but at the time that the RIAA was suing its customers, the MAP verdict was further bad publicity, leading consumers to feel, rightly or wrongly, that they were being treated unfairly by the labels.

- Retailers speak of “share of wallet” and fast food franchises of “share of stomach.” Music's “share of ear” diminished rapidly in the 2000 time frame as cell phones grew rapidly in availability and use. Nextel, to take one example, reported that minutes per user per month increased 65% between 2001 and 2002, to 11 hours per month. Presumably some of this time had previously been spent listening to music.

- Similarly, the DVD and video game occupied part of the day for those aged 16 to 24 in particular, who a generation earlier were spending more time listening to music.

- Finally, the Internet, apart from its file-sharing capabilities, constituted a diversion from traditional ways of finding and listening to music.

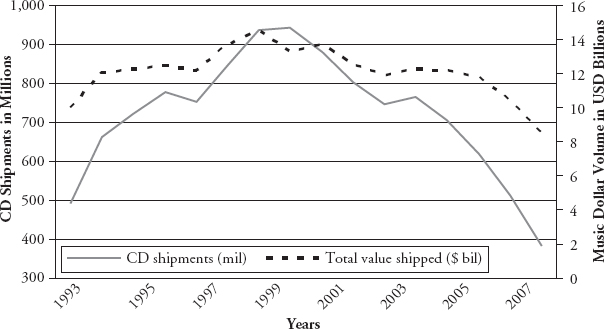

These changes combined to create a slowdown: Compared to the doubling that occurred between 1989 and 1994, purchases of recorded music increased only an average of .4% per year between 1996 and 2002, as Figure 18.1 illustrates.

Business Model Disruption Post-Napster

Against the backdrop of so many challenges to the core business model, from stale inventory of new acts, to poor perception of the labels by consumers, to heavy overhead in the cost structure of music production and distribution, Napster hit the industry like a lightning bolt: In November 2000 alone, 1.75 billion songs were downloaded via the service. That number, annualized, projected to 21 billion songs, or about 1.5 billion CDs. In 2000, the U.S. retail channel moved about 1 billion CDs. In essence, the “inferior” technology (with a poor interface, complicated naming conventions, and obvious audio inferiority) effectively surpassed the entire retail channel as a distribution mechanism in one year. In addition, it was a highly centralized system in contrast to later file-sharing arrangements, but at its peak there were reportedly 25 million users and 80 million songs, and the system never once crashed.

FIGURE 18.1 CD Shipments and Total Music Dollar Volume, 1993–2007

Data Source: Recording Industry Association of America.

With public perception of the labels already low because they were perceived to be exploiting both customers and artists, ripping off the companies was morally less complicated for college-age students than was, say, stealing books from a public library. When the labels began suing music lovers (or mistakenly suing people who did not listen to music), that perception took a further downturn. Meanwhile, the holding companies within which the labels resided were dissatisfied with their poor performance: Labels simultaneously faced pressure from artists long ill-served by standard contract practices, from listeners, from retailers that moved CD selling space to more profitable ventures, and from their bosses.

Enter Apple, a company with a substantially more positive public persona. The iPod was neither the first nor the most powerful MP3 player. It did employ systems thinking to create a seamless, easy user experience, and co-founder Steve Jobs' background in Hollywood while at Pixar gave him familiarity with the entertainment industry. Here as elsewhere, the business model was more a shift in perception rather than a technology breakthrough. As one industry analyst noted in 2002, “The music label executives we spoke with are so sure piracy is destroying their business, that they seemed strangely uninterested in the truth.”2 Apple was able to bridge the CD and MP3 models for a significant portion of the market by simultaneously satisfying the labels (in part with copy protection) and customers (with ease of use, clever marketing, and hardware integration) in ways the labels by themselves could not.

Another brand play was being made by artists themselves. While the most common tactic is buying (or rerecording) one's back catalog, other artists are releasing directly to various forms of download. Perhaps the most famous and successful episode for experiment was Radiohead's experiment in name-your-own-price downloads, which let fans (legally) pay nothing for the album In Rainbows. While many paid nothing (or downloaded p2p copies), the average amount paid was £4 ($5.70 at the time). Once it was released in physical formats, the album sold 3 million units in all formats; a limited edition box set of LPs and CDs with other extras sold 100,000 units at $80 apiece. Thus, the band conducted a real-world experiment in versioning information goods, letting the market segment into multiple price tiers in exchange for varying bundles of value. The experiment has also never been successfully repeated, even by the same band.

By 2010, download sales, never on the scale of physical CD sales, had stagnated.3 Streaming services such as Pandora and Grooveshark were adding users at a rapid rate at the same time that iPod sales slowed (nearly a fifth between 2009 and 2010) in the face of smartphone and tablet adoption.

Touring remained big business: The 13 highest-grossing tours ever, each of which made more than $200 million in 2010 dollars, all occurred after 2001—in other words, after Napster. Significantly, nearly all (with the exception of the Backstreet Boys in 2001) were acts in their 40s or older: the Rolling Stones, U2, Cher, Madonna, the Police, and Bruce Springsteen, for example. Although so-called 360-degree deals are coming into favor (where the label helps promote, and takes a cut of, merchandise and tour revenues, for example), generally bands rather than labels keep most of the tour profit.

Because the hardware is locked down more tightly than CDs or DVDs, game platforms have generated surprising revenues for bands and labels: Inclusion of a track in a sports title or in Rock Band or another music game generates revenues, though labels typically are—unsurprisingly—unhappy with the royalty rates. In the three years after the launch of the plastic-guitar game genre, revenues were reported in the $2.3 billion range, but sales dropped rapidly when the fad passed; in 2010 Viacom sold its music-games business, which like other console games faced a major disruption of its own from low-tech social games such as FarmVille.

Looking Ahead

It's hard to imagine an industry responding much worse than the record labels did when faced with such a significant challenge. Taking profit margins almost as a birthright, most decisions—including appeals for legislation—were premised on maintenance of the status quo. Several decisions have proved crucial, most falling into the mind-set/worldview camp rather than a technology challenge per se:

- Customers resisted bundle pricing when they could emotionally identify the valuable assets in the bundle. Existing margins, however, became a baseline assumption even though Internet music distribution destroyed the logic for a physical package of multiple songs.

- Having limited contact with the consumers of their products, labels compounded the perception issue by suing users, planting corrupted files in p2p networks, clinging to unrealistic pricing ($16.99 for a physical CD), and making other profit-driven moves that detracted from the user experience.

- Continuing to think of music as a product rather than a service inhibited innovation along the lines of what worked for Apple, Pandora, Spotify, and other distributors of online music files and streams. Even in 2011, innovation came from Amazon even as EMI, one of the remaining four major labels, bounced between reluctant owners: Citicorp repossessed the label from a private equity group whose debt to the bank went unpaid, then in turn sold pieces of it at a loss to Sony and Universal (part of Vivendi).

- Managing demographics in a taste-driven business is never easy, but the quest for megahits may preclude the development of an ecosystem with varying levels of popularity (the so-called long tail) and proliferation of niches.

For the music industry to recover even partially, online distribution will need to be managed in a seamless web of actors, channels, and audiences. Live music, television, streaming, and licensing can all contribute to overall revenue. Both extreme localization and global megastars play a role in the ecosystem. Finally, the place of a music label in talent identification, content generation, and digital distribution needs to be redefined from a blank sheet. Music matters to many people, but making it profitable for the various entities in the industry remains a challenge.

Notes

1. Orrin Hatch quoted in “Rights Issue Rocks the Music World,” USA Today, September 16, 2002, www.usatoday.com/life/music/news/2002-09-15-artists-rights_x.htm.

2. Josh Bernoff of Forrester Research quoted in Dan Bricklin, “The Recording Industry is Trying to Kill the Goose That Lays the Golden Egg,” September 9, 2002, www.bricklin.com/recordsales.htm.

3. Glenn People, “Growth in Sales of Digital Downloads Slows to a Trickle,” Reuters, December 10, 2010, www.reuters.com/article/2010/12/11/us-downloadsidUSTRE6BA09620101211.