CHAPTER 20

Healthcare

The solution seems obvious: to get all the information about patients out of paper files and into electronic databases that … can connect to one another so that any doctor can access all the information that he needs to help any given patient at any time in any place.

—“Special Report: IT in the Health-Care Industry,” The Economist, April 30, 2005

There's no question that U.S. medicine is approaching a crisis. Depending on who's counting, tens of millions of Americans carry no health insurance. Between 44,000 and 98,000 people are estimated to die every year from preventable medical errors such as drug interactions; the fact that the statistics are so vague testifies to the problem. The United States leads the world in healthcare spending per capita by a large margin ($7,500 versus about $5,000 for the runners-up: Norway, Canada, and Switzerland), but U.S. life expectancy ranks twenty-seventh, near that of Cuba, which is reported to spend about 1/25th as much per capita. Information technology (IT) has made industries such as package delivery, retail, and mutual funds more efficient; can healthcare benefit from similar gains?

Any assessment of the impact of information and communications technologies on the U.S. healthcare system must consider their effects on the multiple business models already in place. Unlike, say, Napster and the music industry or even the multithreaded issues of news, publishing companies, and the Internet, U.S. healthcare is so incredibly vast, with dozens if not hundreds of business models, that there is no single “it” to be disrupted.

The farther one looks into this issue, the more tangled the questions get. Let me assert at the outset that I believe electronic medical records are a good idea. But for reasons outlined later, IT by itself falls far short of meeting the challenge of rethinking health and healthcare. At the same time, those invested in the status quo should probably not get too comfortable, given some weak signals in the area of social media in particular.

Definitions

What does the healthcare system purport to deliver? If longevity is the answer, clearly much less money could be spent to bring U.S. life expectancy closer to Australia, where people live an average of three years longer with per capita expenditures 57% lower than in the United States But health means more than years: the phrase “quality of life” hints at the notion that we seek something nonquantifiable from doctors, therapists, nutritionists, and others. At a macro level, no one can assess how well a healthcare system works because the metrics lack explanatory power: We know, only roughly, how much money goes in to a hospital, health maintenance organization (HMO), or even economic sector, but we don't know much about the outputs.

Thinking of life expectancy, Americans at large don't seem to view death as natural, even though it's one of the very few things that happens to absolutely everyone. Within many outposts of the healthcare system, death is regarded as a failure of technology, to the point where central lines, respirators, and other interventions are applied to people who are naturally coming to the end of life. This approach of course incurs astronomical costs, but it is a predictable outcome of a heavily technology-driven approach to care.

At the other end of the spectrum, should healthcare make us even “better than well?” As the bioethicist Carl Elliott compellingly argues in his book of that name,1 a substantial part of our investment in medicine, nutrition, and surgery is enhancement beyond what's naturally possible. Cosmetic surgery, steroids, implants, and blood doping are no longer the exclusive province of celebrities and world-class athletes. Not only can we not define health on its lower baseline, it's getting more and more difficult to know where it stops on the top bound as well.

If health is partially defined by what people ingest, why stop with vitamins and supplements? What about the less healthy inputs that can be named as contributors to pulmonary conditions, obesity, or mouth cancers? That is, do both negative and positive contributors to people's wellbeing get included in the accounting? Are cigarette sales factored into the healthcare accounting? As a result of the definitional issues inherent in the subject matter and the massive scale of the enterprise, trying to name the U.S. healthcare “system” invites conceptual misery.

Healthcare as Car Repair for People?

Speaking in gross generalizations, U.S. hospitals are not run to deliver health; they are better described as sickness-remediation facilities. The ambiguous position of women who deliver babies demonstrates the primary orientation. Many of the institutional interventions and signals (calling the woman a “patient,” for example) are shared with the sickness-remediation side of the house even though birth is not morbid under most circumstances. Some hospitals are turning this contradiction into a marketing opportunity: Plushly appointed “birthing centers” have the stated aim of making the new mom a satisfied customer. “I had such a good experience having Max and Ashley at XYZ Medical Center,” the intended logic goes, “that I want to go there for Dad's heart problems.”

Understanding healthcare as sickness remediation has several corollaries. Doctors are deeply protective of their hard-won cultural authority, which they guard with language, apparel, and other mechanisms, but the parallels between a hospital and a car repair garage run deep. After Descartes philosophically split the mind from the body in the 17th century, medicine followed the ontology of science to divide fields of inquiry—and presumably repair—into discrete units.

At teaching hospitals especially, patients frequently report feeling less like a person and more like a sum of subsystems. Rashes are for dermatology, heart blockages set off a tug-of-war between surgeons and cardiologists, joint pain is orthopedics or maybe endocrinology. Root-cause analysis frequently falls to secondary priority as the patient is reduced to his or her compartmentalized complaints and metrics. Pain is no service's specialty but many patients' primary concern. Systems integration between the subspecialties often falls to floor nurses and the patient's advocate if he or she can find one. The situation might be different if one is fortunate enough to have access to a hospitalist: a new specialty that addresses the state of being hospitalized, which the numbers show to be more deadly than car crashes.

The division of the patient into subsystems that map to professional fields has many consequences. Attention focuses on the disease state rather than the path that led to that juncture: Preventive care lags far behind crisis management in glamour, funding, and attention. Diabetes provides a current example. Drug companies have focused large sums of money on insulin therapies, a treatment program that can change millions of people's lives, and more recently on obesity drugs. But when public health authorities try to warn against obesity as a preventive attack on diabetes, soft-drink and other lobbies immediately spring into action.

Finally, western medicine's claim to be evidence based contradicts the lack of definitive evidence for ultimate consequences. The practice of performing autopsies in cases of death where the cause is unclear has dropped steadily and steeply (from 19% of all U.S. deaths in 1972 to 8% in 2003), to the point where doctors and families do not know what killed a sizable population of patients. A study at the University of Michigan estimated that almost 50% of hospital patients died of a condition for which they were not receiving treatment.2 It's potentially the same situation as storeowner John Wanamaker bemoaning that half of his advertising budget was being wasted, but not knowing which half.

Following the Money

Healthcare costs money, involves scarcities and surplus, and employs millions of people. As such, it constitutes a market—but one that fails to run under conventional market mechanisms. (For example, excess inventory, in the form of unbooked surgical times, let's say, is neither auctioned to the highest bidder nor put on sale to clear the market.) The parties that pay the most are rarely the parties whose health is being treated; the parties that deliver care lack detailed cost data and therefore price services only in the loosest sense; and the alignment of patient preference with some notion of greater social good through the lens of for-profit insurers has many repercussions.

Consider a few market-driven suboptimizations:

- Chief executives at HMOs are rewarded for cost cutting, which often translates to cuts in hospital reimbursement. Hospitals, meanwhile, are frequently not-for-profit institutions, many of which have been forced to close their doors in the past two decades.

- Arrangements to pay for certain kinds of care for the uninsured introduce further costs, and further kinds of costs, into an already complex set of financial flows.

- As the British social researcher Richard Titmuss showed more than 30 years ago in The Gift Relationship,3 markets don't make sense for certain kinds of social goods. In his study, paying for blood donation lowered the amount and quality of blood available for transfusion; more recently, similar paradoxes and ethical issues have arisen regarding tissue and organ donation.

- Insurers prefer to pay for tangible rather than intangible services. Hospitals respond by building labs and imaging centers as opposed to mental health facilities, because services like psychiatric nursing are rarely covered.

- Once they build labs, hospitals want them utilized, so there's further pressure (in addition to litigation-induced defensiveness) for technological evidence gathering rather than time-consuming medical art such as history taking and palpation, for which doctors are not reimbursed.

- Many medical schools can no longer afford for their professors to do nonreimbursable things such as teach or serve on national standards bodies. The doctors need to bring in grant money to fund research and insurance money for their clinical time. Teaching can be highly uneconomical for all concerned. One reason there is a shortage of nurses, meanwhile, is that there is a shortage of nursing professors.

- As a result, conditions with clear diagnoses (such as fractures) are treated more favorably in economic terms, and therefore in interventional terms, than conditions that lack “hard” diagnostics (such as allergies or neck pain). Once again, the vast number of people with mental health issues are grossly underserved.

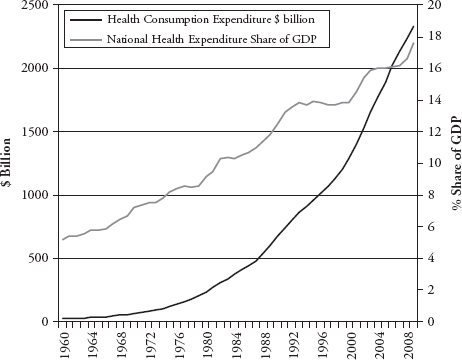

If the trend does not reverse soon, healthcare expenditures are projected to double as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) in only 25 years, according to the Congressional Budget Office. (See Figure 20.1.)4

FIGURE 20.1 U.S. Healthcare Costs in Dollars and as a Percent of GDP

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Where Information Technology Can and Cannot Help

IT has made significant improvements possible in business settings with well-defined, repeatable processes, such as originating a loan or filling an order. Medicine involves some processes that fit this description, but it also involves a lot of impossible-to-predict scheduling, healing as art rather than science, and institutionalized barriers to communication.

IT is currently used in four broad medical areas:

- Billing and finance

- Supply chain and logistics

- Imaging and instrumentation

- Patient care

Patient registration is an obvious example of the first; waiting rooms and foodservice the second; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appointments, blood tests, and bedside monitoring the third; and physician order entry, patient care notes, and prescription writing the fourth. Each type of automation introduces changes in work habits, incentives, and costs to various parties in the equation.

Information regarding health and information regarding money often follow parallel paths: If I get stitched up after falling on my chin, the insurance company is billed for an emergency department visit and a suture kit at the same time that the hospital logs my visit—and, I hope, flags any known antibiotic allergies. Meanwhile the interests and incentives are frequently anything but parallel: I might want a plastic surgeon to suture my face; the insurer prefers a physician's assistant. From the patient's perspective, having systems that more seamlessly interoperate with the HMO may not be positive if that results in fewer choices or a perceived reduction in the quality of care. On the provider side, the hospital and the plastic surgeon will send separate bills, each hoping for payment but neither coordinating with the other. Bills frequently appear in a matter of days, with every issuer hoping to get paid first, before the patient realizes any potential errors in calculating copay or deductible. The amount of time and money spent on administering the current dysfunctional multipayer system is difficult to conceive: One credible estimate suggested 21% of excess spending, or $150 billion in 2008, came from administrative costs.5

Privacy issues are nontrivial. Given that large-scale breaches of personal information are almost daily news in 2011,6 what assurance will patients have that a complex medical system will do a better job shielding privacy than Citigroup or LexisNexis? With genomic predictors of health—and of potential costs for insurance coverage—around the corner, how will patients' and insurers' claims on that information be reconciled?

Currently a number of services let individuals combine personal control and portability of their records. It's easy to see how such an approach may not scale: Something as trivial as password resets in corporate computing environments already involve sizable costs. In light of that complexity, think about managing the sum of past and present patients and employees as a user base with access to the most sensitive information imaginable. With portable devices proliferating, the many potential paths of entry multiply both the security perimeter and the cost of securing it.

Hospitals already tend to treat privacy as an inconvenience—witness the universal use of the ridiculous johnnie gowns, which do more to demean the patient than to improve quality of care. The medical record doesn't even belong to the person whose condition it documents. American data privacy standards, even after the enactment of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), lag behind those in the European Union. From such a primitive baseline, getting to a new state of shared accountability, access, and privacy will take far more diplomacy than systems development.

Spending on diagnostic technology currently outpaces patient care IT. Hospitals routinely advertise less confining MRI machines, digital mammography, and 3D echocardiography; it's less easy to impress constituencies with effective metadata for patient care notes, for example. (Some computerized record systems merely capture images of handwritten forms with only minimal indexing.) After these usually expensive machines produce their intended results, the process by which diagnosticians and ultimately caregivers use those results is often haphazard: Many tests are never consulted or compared to previous results—particularly if they were generated somewhere else. NIH doesn't just stand for National Institutes of Health; not invented here is also alive and well in hospitals.

Back in the early days of business reengineering, when technology and process change were envisioned as a potent one-two punch in the gut of inefficiency, the phrase “Don't pave the cowpaths” was frequently used as shorthand. Given that medicine can be routinized only to a certain degree, and given that many structural elements contribute to the current state of affairs, it's useful to recall the old mantra. Without new ways of organizing the vastness of a longitudinal medical record, for example, physicians could easily find themselves buried in a haystack of records, searching for a needle without a magnet. Merely automating a bad process rarely solves any problems, and usually creates big new ones.

Change comes slowly to medicine, and the application of technology depends, here as always, on the incentives for different parties to adopt new ways of doing things. Computerized approaches to care-giving include expert knowledge bases, automated lockouts much like those in commercial aviation, and medical simulators for training students and experienced practitioners alike. Each of these methods has proven benefits but only limited deployment. Further benefits could come from well care and preventive medicine, but these areas have proven less amenable to the current style of IT intensification. Until the reform efforts such as the Leapfrog initiative to mobilize employer health insurance purchasing power can address the culture, process, and incentive issues in patient care, the increase in clinical IT investment will do little to drive breakthrough change in the length and quality of Americans' lives.

Disruptive Innovation

Apart from clinical IT, however, several potential disruptions appear to be taking shape. Brief descriptions of some of these are accompanied by potential winners and losers.

Channel Innovation

Recall that healthcare IT focused on four areas: billing and finance, supply chain and logistics, imaging and instrumentation, and patient care. If “patient care” is rephrased as “customer service,” it's clear that companies already good at some of these processes might have potential in some aspect of medicine. As it turns out, such retailers as Wal-Mart, CVS, and Walgreens are putting clinics in selected stores to address routine matters that would often otherwise require an emergency department visit.7

Potential winners: Patients get the right level of care with extreme convenience. Payors get excellent performance for money, if the visit is reimbursed at all, since profitable economics are engineered into the self-selecting population. Retailers give customers more reason to visit. Emergency rooms should benefit by having the private market triage some low-intensity patients out of the system.

Potential losers: Hard to see any, apart from physician prestige.

Telemedicine

Particularly in the developing world, where doctors and clinics cannot meet the need in many countries, mobile phones are connecting people to medical resources in new ways. Real-time diagnostic indicators can be easily transmitted by, and often read on, mobile devices. Cameras can be used as sensors, so the mobile phone becomes a rudimentary blood lab. Text-message reminders to take necessary medication are increasing compliance and improving outcomes. Geolocation can help identify safe water, malarial ponds, and other public health resources. The list goes on, but many of these techniques will migrate from Asia and Africa to North America and Europe in a fascinating pattern of “reverse” globalization.

Potential winners: Citizens, entrepreneurs.

Potential losers: Hard to see any downside, but traditional modes of cure might see decline in prestige.

Online Communities

Imagine living alone, in a big city or a rural town, and having a serious condition, such as multiple sclerosis. Even with insurance, physician and nurse visits can only provide so many answers. What will be the sequence of the disease? How do I choose a good wheelchair? What are the side effects of a given treatment regimen? Web sites such as www.patientslikeme.com have emerged to accumulate and deliver real-world advice and support to many disease communities.8

An important advantage of peer communities over therapeutic providers is in compliance and motivation. In weight loss, for example, having a doctor say “lose 15 pounds” does little in the way of motivation. Finding a community, perhaps one with a shared or individual goal, can make a huge difference. Individually, such behavioral motivators as stickk.com use the academic insight that small symbolic wagers and similar techniques can be highly effective in changing people's patterns. At the group level, the team of Northwestern University alums at workplaces in Chicago will work harder to lose their collective 500 pounds if a charitable donation to the United Way and bragging rights over the Illinois alumni are at stake.

Potential winners: Anyone who has felt isolated while in ill health.

Potential losers: It's hard to call this disruptive, in that most physicians won't claim to be effective motivators, but online communities do have the potential to diminish the doctor's cultural authority when shared research and motivated interest lead the group to start recommending diagnostic or treatment protocols.

Rethinking Devices

A typical ultrasound machine for sale in the United States typically costs in the range of $100,000 and is approximately the size of a washing machine. Portable units closer to the dimensions of a laptop PC have been in various stages of development for roughly a decade and are starting to gain market traction. From the standpoint of an incumbent—GE or Siemens, for example—the new models are not a threat insofar as radiologists at major medical centers would not be satisfied with the limited flexibility and image quality of the portables, so these companies are in fact “disrupting themselves” with certain models.

But the innovation goes beyond engineering and marketing at device manufacturers. What are the implications for the business processes that the technology supports? New kinds of technicians, and training, and treatment protocols are necessary to wrap around the technology. Rather than potentially disrupting nonexistent radiologists in the developing world, the technology has the potential to create whole new “lines of business” compared to stethoscopes or other health technology alternatives.

Portable ultrasound has also been implicated in more than 100 million missing women in Asia: Because of various cultural concerns, girl babies are less desired than boys. Ultrasound imaging can give prospective parents advance notice of a fetus's sex, and gender-driven abortion is common even while illegal. While technologists cannot tell parents the sex, the ultrasound report is sometimes delivered in a pink or blue envelope, and the parents can act on the winked information.9

Potential winners: Hardware manufacturers, wireless carriers, patients.

Potential losers: Patient privacy could become an issue.

Checklists

Surprisingly, the simple checklist is a radical idea in healthcare and in practice is anything but simple. Much like aviation, where the concept originated, many healthcare procedures are complex, life critical, and prone to simple human error: the wrong side of the body is operated on, sponges are left inside the body, bandages and intravenous lines are not changed at the right intervals. Harvard surgeon Atul Gawande has been a leader in a worldwide effort to introduce checklists into surgery, with dramatic results.10

The idea of a checklist introduces multiple issues. Surgeons are known to be skilled and expected to be in charge of the proceedings, but anything as complex as surgery is a team event, and surprisingly little time is spent on improving team performance: Even the simple act of having the team members introduce themselves by name was found to make a difference. Much like business process steps that people are less inclined to perform sloppily if they hand off to a known associate as opposed to an anonymous “other,” surgery goes better if the person behind the mask is a person with a name. Similarly, giving nurses the authority, and the responsibility, to stop a procedure if a critical step, such as the preoperative administration of antibiotic, is not followed shifts responsibility from the artisanal surgeon to the entire team.

Checklist formulation, however, is hard to do well. Put in too many steps, and they get skimmed or the list is disregarded. Fail to spell out, in the fewest words possible, every task, and debates begin about the intent. Include only the essentials, be they trivial or monumental, and checklists save lives: When Captain Chesley Sullenberger and his crew successfully ditched his USAirways A320 in the Hudson River in 2009, they were following checklists, not acting out heroic improvisations. Another aviation checklist includes the imperative “Fly the airplane:” Restarting an engine can become so engrossing that pilots have neglected other higher priorities, such as watching out the window.

While checklists disrupt few business models, they are improving performance, changing authority relationships, and forcing hospital administrators and doctors themselves to revisit their assumptions about the origins of improved patient outcomes. As Gawande writes:

[I]f someone discovered a new drug that could cut down surgical complications with anything remotely like the effectiveness of the checklist, we would have television ads with minor celebrities extolling its virtues…. Government programs would research it. Competitors would jump in to make better and better versions.11

Looking Ahead

With so any moving parts, healthcare delivery and reimbursement in the United States is impossible to characterize except in the broadest possible terms. There will be no Napster, it is safe to say, no Skype, and no Facebook that will dominate. At the same time, changing mores about participation, about cultural differences (in both attitudes and genomes), and about cost and transparency are driving change. The current trajectory is unsustainable, the baby boom generation is entering its most expensive phase of healthcare life, and the numbers prove emphatically that the current model is broken. Fixing little corners, often quietly, will be the norm, and like a path of footsteps in the sand, we most likely will have to look back to figure out when we changed direction.

Notes

1. Carl Elliott, Better Than Well: American Medicine Meets the American Dream (New York: Norton, 2003).

2. Atul Gawande, Complications: A Surgeon's Notes on an Imperfect Science (New York: Picador, 2003), p. 67.

3. Richard Titmuss, The Gift Relationship: From Human Blood to Social Policy (New York: New Press, 1997 reprint).

4. “The Long-Term Outlook for Medicare, Medicaid, and Total Health Care Spending” www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/102xx/doc10297/Chapter2.5.1.shtml.

5. See, for example, Uwe Reinhart, “Why Does U.S. Healthcare Cost So Much: (Part II: Indefensible Administrative Costs),” New York Times Economix blog, November 21, 2008, http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/11/21/why-does-us-health-care-cost-so-much-part-ii-indefensible-administrative-costs/.

6. Note the large number of insurers and providers with data breaches at www.privacyrights.org/data-breach#CP.

7. Gary Ahlquist, Minoo Javanmardian, and Ashish Kaura, “The Pharmacy Solution,” Strategy + Business, February 23, 2010, www.strategy-business.com/article/10103?gko=8ec98.

8. For some leading indicators related to social media and health information, see Susannah Fox, “The Social Life of Health Information, 2011,” May 12, 2011, Pew Internet & American Life Project, www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Social-Life-of-Health-Info.aspx.

9. “The War on Baby Girls,” The Economist, March 4, 2010, www.economist.com/node/15606229/.

10. This entire section relies on Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right (New York: Henry Holt, 2009).

11. Ibid., p. 158.