CHAPTER 35

Innovation

“Innovation” is a word that veers into the realm of motherhood and apple pie: It's good because it's good. If innovation is in fact essential to the American future, however, it must move beyond personal idiosyncrasy, magic, and luck. Merely because innovation does not result from relatively rote application of algorithms does not mean it cannot be learned, measured, or codified. Two examples, among many others, may serve as inspiration going forward.

Amazon

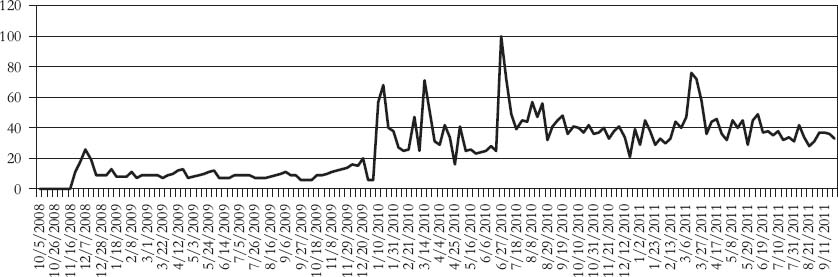

After more than 15 years on the Web, Amazon.com remains a pioneer in online commerce. From the days when its peers were E*TRADE and Dell, then through the periods of iPod and Google ascendency, Amazon is the one company that can claim a consistent leadership position on the Web. It serves as an information-age exemplar because of its combination of innovation and execution, and especially its mastery of platform economics. Today, Amazon continues to help define the Internet as a consumer environment, with rules, limits, and opportunities often different from those experienced in physical channels. Operating under assumptions at variance with conventional businesses, and a survivor of the 2000 dot-com bubble, Amazon is a harbinger of successful business practices in a connected economy. (See Figure 35.1.)

Amazon.com opened for business in July 1995 as an exclusively Internet-based effort. After books, Amazon initially expanded into books on tape, videotapes, and sheet music. It then moved into compact discs, becoming the top Internet music merchant in its first quarter of operation. In late November 1998, Amazon announced that it was temporarily expanding into holiday gifts, including electronics, toys, gadgets, and games. This move, while expected, came earlier than most observers predicted, providing another instance where Amazon acted proactively and forced other industry players to respond. Such expansion established a pattern that has persisted: Amazon moves unexpectedly and faster than conventional wisdom would dictate. More than once, actions that were judged as rash in the investment and business press—such as moving into tools and hardware, or the Amazon Prime prepaid two-day shipping plan—turned out to be successful.

FIGURE 35.1 Amazon.com Share Price and Revenue Performance

Data Source: Yahoo! Finance, Standard & Poor's.

The business was started by Jeff Bezos, who studied computer science and electrical engineering at Princeton before working in investment banking until 1994. His interest in the Internet as a consumer environment began when he saw the growth rate of World Wide Web traffic in the spring of 1994. As Bezos recalled in an interview:

I came across a statistic that the growth rate of Web usage was 2,300 percent a year. … It turned out that, though you couldn't measure the baseline usage, you could measure growth rate. And things rarely grow that quickly…. Just anecdotally, I could tell that the baseline was nontrivial. And therefore it looked like the Web was going to get very big very fast.1

Bezo's immediate business goal—“Get big fast”2—reflects an understanding of power-law economics, the driving force in the software industry that is Amazon's main progenitor. Indeed, the story of how Bezos came to choose books as his domain has become part of Internet folklore. In the summer of 1994, he intensively researched different products to sell online, then chose books from among 20 different candidates. He and his wife moved to Seattle in part to capitalize on the area's large supply of talented computer programmers and focused on the opportunities presented by the fact of books being information goods, by the fragmentation of both supply and demand, and by the demanding inventory needs of a book retailer being easier to meet with connections to distributors' warehouses than with in-house stock. In his analysis, Bezos anticipated Chris Anderson's insight into the long tail of power-law distributions: Vast selection meeting sparse demand in an online marketplace is a formula that defines multiple sectors that Amazon has entered.

It is important to note that, from the outset, Amazon operated on a business model built to exploit the online environment rather than from the standpoint of a product focus. This perspective directly contradicts conventional business wisdom that urges executives to set business goals and then to “enable” those goals with technology. Bezos, like FedEx's Fred Smith and other visionaries, instead studied a set of emerging technological capabilities and wrapped a business around them.

How Amazon Delivers Value

Amazon has consciously built a fourfold value proposition, each dimension of which directly relates to an understanding of the leverage uniquely generated by the online medium:3

- Convenience. The Internet is open for business all the time, across time zones. The Amazon Web site offers multiple paths to a given item: via reviews, categorical browsing lists, multiple dimensions of search capability, referral from a previous search, e-mail notification, a variety of recommendation engines, or personalized messages on the Web interface. The Web site is designed to minimize download time, and the mobile applications are similarly user-centric. (While the site was initially designed for home shoppers, before mass broadband was deployed Amazon would log significant traffic bursts at lunch hour as customers connected over their employers' corporate networks). Through its alliance with Sprint, Amazon can nearly instantly download a Kindle book anywhere there is a Wi-Fi or Sprint cellular signal.

- Selection. No matter what the retail category, Amazon delivers unprecedented selection: New and used items, physical and virtual information goods (book, movie, and music downloads), and international presence begin a list of ways in which Amazon has redefined retail. The virtualization of inventory—affiliates hold many stock-keeping units (SKUs), reducing Amazon's risk while delivering selection—was pioneered early in the company's history, then expanded. Table 35.1 shows the scale of the selection advantage compared to category leaders.

TABLE 35.1 Item Selection Comparison across Online Retailers

- Price. Amazon owns inventory for a much shorter time than physical retailers. As a result, Amazon can sell for less because it is on the right side of debt interest (see below). Labor contributes less to selling price: Amazon's revenue per employee is more than $1 million versus roughly $200,000 for Target. Even with shipping added to an order under $25 (which many shoppers mentally discount as the cost of convenience), Amazon comes out to be roughly 8% to 15% cheaper than a physical retailer, in large measure because it aggressively avoids exposure to sales tax.

- Customer service. Amazon has a call center but keeps the phone number well hidden. Customers are trained to self-service their accounts online, and the company's customer service metrics are exceptionally high even with the lack of human touch. The company's network of warehouses sets the industry standard for fast delivery, even with the large SKU count.

Execution

Amazon's extraordinary performance on some traditional measurements indicates some benefits of its business model. The foremost of these may be cash flow: Amazon's operating cycle—the time from payment to suppliers until payment from customers—is in fact negative. Given that credit card companies typically pay Amazon within 24 hours of an order's receipt, and given that Amazon pays its suppliers 46 days after receipt of goods, the firm has use of the customers' money for several weeks before bills come due. At Best Buy, in contrast, inventory is held, on average, for 74 days, or 30 days after the supplier was paid.

Other metrics are similarly revealing of best-in-class execution:

- Amazon scores extremely high grades on the American Customer Satisfaction Index, not just in its sector but compared to many business categories.4 Other rankings, including those from ForeSee5 and BIGresearch,6 also rank Amazon on top.

- The customer base is in the range of 75 million people, with offerings customized for each individual who logs in.

- Google has indexed more that 107 million Amazon pages, which provides a rough estimate of SKU count. Because those pages are heavily viewed, Google ranks them highly in core search results, meaning that Amazon needs to spend less on paid search advertising.

- Amazon processes 24 orders per second.7

- Eighty-one million people visit per month, ranking Amazon in the top 20 of Web destinations worldwide.

Innovation

In keeping with the hypothesis that superb execution is necessary but no longer sufficient for business success, Amazon (like Apple) excels at innovation. The firm is responsible for several developments that are now part of the online landscape:

- From early in the company's history, Amazon has utilized user-generated content in the form of product reviews and reviews of the reviews. Amazon, in short, utilized social media before anyone called it that.

- In addition to user recommendations, Amazon helped customers navigate its large product selection with specialized search (after its A9 service did not dent Google in head-to-head competition in 2005) as well as collaborative filtering of the sort used at Netflix: People who liked this item also liked that one. All three forms of navigation are essential to making long-tail product selection work.

- The shopping-cart metaphor and one-click shopping both came from Amazon.

- Opening up Amazon's distribution network to competitors or merely third parties of any sort turned Amazon from a store into a commerce platform.

- Turning its expertise with Web-based customer service and very large data centers into a profit center, Amazon made another platform play with Amazon Web Services, a pioneering cloud computing offering.

- While Amazon has digitized many forms of media (including music and television), its Kindle book platform is reinventing the entire publishing industry. Physical bookstores, publishers, and authors all find themselves reacting to Amazon's Kindle moves. In late 2011, Amazon expanded from e-readers into tablets, with the intent of tightening the link to the shopping experience rather than confronting the Apple iPad as a general-purpose device.

- Amazon is reinventing the publishing value chain, integrating most every function from writer acquisition, self-publishing, branding (for example signing the self-help author Timothy Ferriss to Amazon's own Imprint, bypassing the conventional publisher's role), print-on-demand, and audiobook publishing as well as used-book selling.

- Amazon pioneered the Gold Box, the predecessor of one-deal-at-a-time sites such as Gilt Groupe and woot!

- In 2005, Amazon launched Prime, its prepaid free two-day shipping membership.

- The Amazon smartphone app, including instantaneous bar-code scanning, helped lead the way to hybrid local–mobile commerce. One form of this model essentially turns any physical retailer into an Amazon showroom.

Lessons from Amazon

Given its long history, its large scale, its inability to be categorized, and its operational excellence, Amazon is a hard company to copy. That said, four lessons may be applicable in other efforts:

- Focus on the customer. Amazon's share price has been volatile in part because the company is not afraid of big bets (whether in warehouse networks, server farms, or now hardware device development). The company is also hard for analysts to value because it has no peers that share its key operational components. Thus, rather than managing to Wall Street expectations, Amazon manages to customer behavior.

- Identify inefficiencies, then invent ways to reduce or eliminate them. Nowhere is this truer than in Amazon's redefinition of book publishing. Several layers of intermediaries find themselves cut out of the extended Kindle ecosystem.

- Try things, collect data, and adjust. Amazon relentlessly innovates. Not every experiment pays off, as when the site presented variable prices for DVDs in 2000.8 The tabbed model for different product departments did not scale well, so the site was redesigned to put more emphasis on customization for the individual shopper than on the store's many product categories. The Kindle reader has evolved rather than being assumed to be perfect upon release: Other companies put usability issues on the customer whereas Amazon continually tweaks, monitors, and alters.

- Watch the platform. Amazon's logistics system, opened to affiliates from an early date in the company's history, is one platform. Cloud computing is another. The reading Kindle is a third major platform, with the color Kindle Fire potentially a fourth. Going forward, Amazon (which already offers a credit card) could move into mobile payments. The merchant could expand its footprint in digital media. The point is that platform plays require entrepreneurial initiative, deep pockets, a wide web of relationships, and an engaged customer base. Amazon has all of the above. As winners from IBM, Microsoft, and Google have shown, the stakes of platform plays can be lucrative indeed. There is little reason to doubt Amazon's chances of extending its track record.

Crowds

The Internet, particularly its mobile variant, dramatically lowers coordination costs, as we have seen repeatedly. The possibilities for crowds to mobilize to solve problems are multiplying, providing a second rich resource for innovation.

Tools

Several examples might point the way to other possibilities.

- InnoCentive utilizes a challenge model to pose hard problems to groups of people who, often from different disciplinary perspectives, contribute insights. Sponsor companies pay only for results. On top of money, participants get the intrinsic rewards of being self-directed, creative, and recognized for making a difference.

- As we saw in Chapter 11, Foldit turns protein folding into an online game and has begun to crack long-standing scientific problems.

- A key stage in innovation is need identification. With geographic mapping tools such as Ushahidi (see Chapter 12), London Potholes (http://yourpotholes.crowdmap.com/), or Safecast (which tracks Japan's radiation levels), ground truth is easier to obtain.

- Using tools of mass sentiment, including Facebook and Twitter, as well as Google Trends (see Figure 35.2), mass behavior can be mined to generate insight on needs, if not to generate solutions. The analytics and visualization tools noted in Chapters 29 and 30 are highly relevant here.

FIGURE 35.2 Google Trends Data for Interest in Search Term “Ushahidi”

Data Source: Google Trends.

Video

To illustrate a different angle on the crowd dynamic, I'd like to discuss a video by TED producer Chris Anderson.9 In it he looks at the proliferation of online videos as tools for mass learning and improvement. Starting with the example of self-taught street dancers in Brazil, Japan, Los Angeles, and elsewhere, he argues that the broad availability of video as shared show-and-tell mechanism spurs one-upmanship through imitation and then innovation. The level of TED talks themselves, Anderson argues, provides home-grown evidence that cheap, vivid multimedia can raise the bar for many kinds of tasks: futurist presentations, basketball dunks, surgical techniques, and so on.

Five factors relative to usability are important in the case of Web video being radically accessible.

- The low barrier to entry for imitator/innovator #2 to post her contribution to the discussion may inspire, inform, or infuriate imitator/innovator #3. Mass media did some of these things (in athletic moves, for example: Watch a playground the week after the Super Bowl or a halfpipe after the X games). The lack of a feedback loop, however, limited the power of broadcast to propagate secondary and tertiary contributions.

- Web video moves incredibly fast. The speed of new ideas entering the flow can be staggering once a video goes viral, as its epidemiological metaphor would suggest.

- The incredible diversity of the online world is increasing every year, so the sources of new ideas, fresh thinking, and knowledge of existing solutions multiply as well. Credentials are self-generated rather than externally conferred: A dance video gets views not because its creator went to Julliard but because people find it compelling and tell their friends, followers, or colleagues.

- Web video is itself embedded in a host of other tools, both social and technical, that are also incredibly easy to use. Do you want to tell someone across the country about an article in today's paper newspaper? Get out the scissors, find an envelope, dig up his current address, figure out correct postage (pop quiz: how much is a first-class stamp today?), get to a mailbox, and wait a few days. Want to recommend a YouTube or other Web video? There are literally hundreds of tools for doing so, essentially all of which are free and have short learning curves.

- Feedback is immediate, in the form of both comments and views counters. The reputational currency that attaches to a “Charlie bit my finger” or “Evolution of dance” is often (but not always) nonmonetary, to be sure, but emotionally extremely affecting nonetheless.

With such powerful motivators, low barriers to participation, vast and diverse populations, rapidity of both generation and diffusion, and a rich ancillary toolset relating to online video, Anderson makes a compelling case for the medium as a vast untapped resource for problem solving on multiple fronts. In addition, because video involves multiple senses, the odds that a given person will grasp my ideas increases as the viewer can hear, watch, or read text relating to the topic. In the face of an urgent need to innovate, the tool set is, fortunately, powerful and accessible.

Looking Ahead

Innovation has never been more needed—one study suggests that innovation per capita peaked well over 100 years ago—or more possible. Open platforms, starting with the Web itself, allow the harvesting of more effort. Wireless hardware puts tools in the hands of millions more people every year. Distributed sensors, radios, and geographic information can be cleverly combined in ways never before possible. Perhaps most important, harvesting the “people power” of good questions, good ideas, and good challenges recalibrates the investment model of many categories of innovation. As the MIT response to the DARPA balloon challenge illustrated (see Chapter 3), getting the incentive model right to drive the right people to participate was more important than any algorithm or piece of code.

Notes

1. Dickson Louie and Jeffrey F. Rayport, “Amazon.com: Portrait of a Cybercorporation,” Electronic Commerce Advisor (September/October 1997): 5.

2. Doreen Carvajal, “The Other Battle Over Browsers: Barnes & Noble and Other On-Line Booksellers Are Poised to Challenge Amazon.com,” New York Times, March 9, 1998, www.nytimes.com/1998/03/09/business/other-battle-overbrowsers-barnes-noble-other-line-booksellers-are-poised.html.

3. Bezos spells out the value proposition in an interview in William C. Taylor, “Who's Writing the Book on Web Business?” Fast Company (October 31, 1996), www.fastcompany.com/magazine/05/starwave2.html.

4. www.theacsi.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=206:acsiscores-february&catid=14&Itemid=259.

5. “Top 100 E-Retailers: ForeSee Results Quantifies Relationship Between Customer Satisfaction and Purchase Intent,” ForeSeeResults.com, May 10, 2011, www.foreseeresults.com/news-events/press-releases/top-100-e-retailerssatisfaction-predicts-intent-spring-2011-foresee.shtml.

7. Linda Bustos, “10 Reasons Not to Copy Amazon,” GetElastic.com, July 9, 2010, www.getelastic.com/10-reasons-not-to-copy-amazon/.

8. Craig Bicknell, “Online Prices Not Created Equal.” Wired, July 9, 2000, www.wired.com/techbiz/media/news/2000/09/38622.

9. Chris Anderson, “How Web Video Powers Global Innovation,” TED Talks, September 2010, www.ted.com/talks/chris_anderson_how_web_video_powers_global_innovation.html.