CHAPTER 6

Power Laws and Their Implications

While many people are accustomed to seeing bell curves explaining many facets of everyday reality, these statistical distributions do an extremely poor job of explaining information, or risk, or social network landscapes. Instead, power laws explain both the leviathans of the Internet—Facebook or Google—and the millions of YouTube videos that apparently nobody watches. The behavior of systems that conform to these curves is both predictable and new as compared to scenarios involving physical widgets sold through physical stores in local markets.

A Bit of History

Back at the turn of the century, the Internet sector was in the middle of a momentous slide in market capitalization. Priceline went from nearly $500 a share to single digits in three quarters. CDnow fell from $23 to $3.40 in about nine months ending in March 2000. Corvis, Music Maker, Dr. Koop—2000 was a meltdown the likes of which few investors had ever seen or imagined. Science was invoked to explain this new world of Internet business.

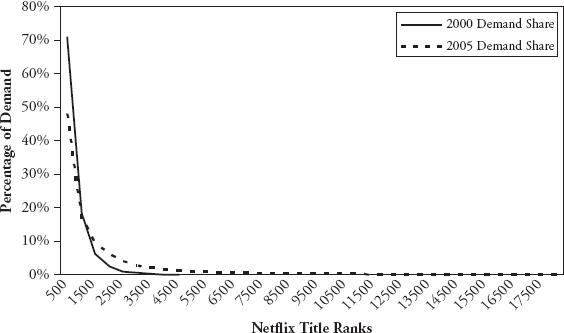

Bernardo Huberman, then at Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), and others found that the proportion of Web sites that got the bulk of the traffic fell far from standard market share metrics: As of December 1, 1997, the top 1% of the Web site population accounted for over 55% of all traffic.1 This kind of distribution was not new, as it turned out. A Harvard linguist with the splendid name of George Zipf counted words and found that a tiny percentage of the English language accounts for a disproportionate share of usage. A Zipf distribution, plotted on a log-log scale, is a straight line from upper left to lower right. In linear scale, it plunges from the top left and then goes flat for the characteristic long tail of the distribution: Twosies and then onesies occupy most of the x-axis, as seen in Figure 6.1.

Given such “scientific” logic, investors began to argue that the Internet was a new kind of market, with high barriers to entry that made incumbents' positions extremely secure. Michael Mauboussin, then at CS First Boston and now at Legg Mason, wrote a paper in late 1999 called “Absolute Power.”2 In it he asserted that “power laws … strongly support the view that on-line markets are winner-take-all.” But winners don't take all: Since that time, Google has challenged and surpassed Yahoo, weblogs have markedly deteriorated traffic to online news sites, and MySpace lost its early lead in social networking. Is the Zipf distribution somehow changing? Were power laws wrongly applied or somehow misunderstood?

In 2004, Chris Anderson, editor of Wired, had a different reading of the graph. Instead of looking at the few very big winners at the head, he focused on the long tail. In an article that became a book, Anderson explained how a variety of Web businesses have prospered by successfully addressing the very large number of niches in any given market. Jeff Bezos, for instance, at one time estimated that 30% of the books Amazon sold weren't in physical retailers. Unlike Excite, which couldn't make money posting banner ads against the mostly unique queries that came into the site, Google uses Adwords to sell nearly anything to however many people search for something related to it, one search at a time. Netflix carries far more inventory than a neighborhood retailer can and can thus satisfy any film nut's most esoteric request. eBay matches a vast selection of goods with a global audience of both mass and niche customers.

FIGURE 6.1 Generic Power Law Graph

Source: Wolfram Alpha LLC. 2011. Wolfram | Alpha, www.wolframalpha.com.

Long-Tail Successes

Amazon, eBay, Google, and Netflix—the four horsemen of the long tail, as it were—share several important characteristics. First, they either offload physical inventory to other parties (in the Netflix case, its warehouse network includes customers' kitchen tables) or have developed best-in-the-world supply chain management (Amazon). Google touches as few invoices as possible and no physical product whatsoever.

Second, each company has invested in matching large, sparse populations of customers to large, sparse populations of products. That investment might take the form of search: AltaVista founder Louis Monier worked at eBay for a time; Amazon tried to make a run at Google in general search with A9 in 2006 before retrenching and innovating in more focused “search inside the book” and mobile/location services. As Netflix showed, other technologies are powerful in the long tail as well: Using collaborative filtering, social reviewing, and audience surveys, both Amazon and Netflix have become expert at predicting future desires based on past behavior.

This sparseness, combined with the Internet's vast scale, is the defining characteristic of the long tail. As YouTube illustrates, people are happy to create content for small or even nonexistent audiences. At the same time, producers of distinctive small-market goods (like weblogs, garage demo music, and self-published books) can through a variety of mechanisms reach a paying public. Thus, the news is good for both makers and users, buyers and sellers to the point that libertarian commentator Virginia Postrel has made huge selection a political issue, writing on the virtues of the choice and variety we currently enjoy.3

Cautionary Tales

In his hugely influential tandem of books, The Black Swan and Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Nicholas Taleb raised the contrast between power laws and Gaussian (bell curve) distributions to the level of cultural criticism.4 He asserted that risk, wealth, fame, and information on networks all fit long-tail distributions, noting that fat-tail risk (global financial meltdown, tsunamis, Hurricane Katrina, etc.) is both always with us and all-too-frequently left unacknowledged by the ubiquitous bell curves employed by financial analysts. The events of 2008 seemed to bear him out, for reasons we will see in Chapter 7 on risk. For our purposes, it is important to focus on the loss of the “average” as a meaningful concept in power law scenarios. We will return to the implications of this fact soon.

The second caution about the long tail comes from a different direction. Dan Frankowski was working on an early social data set at the University of Minnesota: the MovieLens film rating system. He and his coresearchers found that as data got sparser (such as with a large list of movies, many of which got only a handful of votes), it became easier to link a public comment on a message board, for example, with a private data point (a rating on MovieLens or, hypothetically, a rental at Netflix). Whereas rating or commenting on a hit movie at the head of the distribution was reasonably anonymous, moving out onto the tail, especially in conjunction with expressions related to other titles in the sparse space, significantly increased the odds of reidentification.5 This dynamic is informing many other technologies aimed at finding important relationships in large, noisy data sets.

Facts of Life

Living in a long tail has new costs, opportunities, and risks. Recent research suggests that the long tail is getting both longer and more lucrative. MIT's Erik Brynjolfsson and his colleagues compared Amazon's sales data from 2000 to 2008. After quantitatively rigorous analysis, the conclusions are vivid: “The … results provide empirical evidence that Amazon's Long Tail has become longer and fatter in 2008 than in 2000. As sales ranks increase, book sales decline. Such a decline is at a slower pace in 2008 than in 2000.”6

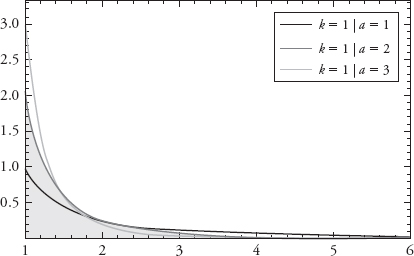

At about the same time, University of Pennsylvania Professor Serguei Netessine and his colleague Tom F. Tan analyzed movie rental data that was part of the data set made available to Netflix prize* researchers. They came to a similar conclusion comparing customer habits in 2000 versus 2005: There was a marked drop in demand for the top 500 titles, the “knee” of the curve was thicker, and 15% of demand came from titles ranked below 3,000, which is the inventory of a typical physical video store. As Figure 6.2 illustrates, the long tail at Netflix grew both fatter and longer after the year 2000, just as it had at Amazon.7

FIGURE 6.2 Changing Power Law Distribution at Netflix

Source: Tom F. Tan and Serguei Netessine, “Is Tom Cruise Threatened? Using Netflix Prize Data to Examine the Long Tail of Electronic Commerce,” Wharton working paper. knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/papers/1361.pdf.

Implications

For merchandising, selection can become a basis of competition in ways it could never be in physical stores. Especially for digital goods, such as Kindle books or music and movie downloads, the lack of physical inventory rewrites the rules on competition. Demand planning, production planning, and logistics of getting the right number of units to where demand is expected to materialize are no longer issues. As with app stores for basically the same reason, digital downloads remove much of the risk from the seller, which can pay royalties after sale without up-front investment in inventory.

As we saw, long tails of supply can now be matched more effectively with sparse communities of demand. The net result is that formerly neglected items find larger audiences, and while they may or may not become hits (as in the case of Soulja Boy*), some songs, videos, and eBay items do climb out of the long tail of obscurity. Price and availability will change accordingly: If World War II recruiting posters become popular for whatever reason, people with access to such artifacts will be more likely to bring them to market. Inventory items can thus move up or down the power law curve.

Both eBay and Amazon shift the risk of holding physical inventory onto extensive networks of partners. Netflix, Apple, and Google are striving to become purely digital in their content businesses. Compared to Best Buy or Tower Records of the 1980s, the organizational shape, capital requirements, growth prospects, and hiring needs of a twenty-first-century content business are completely different.

Outside the entertainment realm, Linux and Wikipedia turn out to exhibit long-tail traits on the supply side: A small number of very busy contributors do a huge percentage of the work, but the long tail of contributors of single items turns out to be a significant population as well.8 Not all contributions are of equal weight: If a solitary contributor writes one piece of code or biography that wouldn't have been completed otherwise, it is a potentially important win for the overall effort. The Internet commentator Clay Shirky makes this point clearly: Traditional organizations cannot afford to have large numbers of contributors who don't contribute much. Pareto reigns, on the logic that “we can have 5% of the population do 85% of the work.” Indeed, that would be a fortunate company. But in the connected, global world of voluntary, loose organizational forms, low coordination costs enable the perhaps quirky, perhaps uninspired contributions of the long tail to be harvested at low if any cost.9

Looking Ahead

For these reasons, management is changing at places like developer networks, as we will see in Chapter 17: One-tenth of 1% of Google Android applications have more than 50,000 downloads; 79% of titles have reached fewer than 100 people. Because of the app store structure, however, no product planner needs to develop ulcers about slow-selling titles: All the risk is borne by the developers as Apple and Google much prefer to gain market share in hardware.10 At the same time, managing the entire ecosystem presents new challenges: With low barriers to entry and hundreds of thousands of applications to manage, even something as simple as paying application developers can be a real headache. In addition, maintaining the platform's attractiveness is vitally important but involves many intangibles and competitive pressures, just as product development does, but in a far less constrained space. Long tails also change the possibilities for how people and resources organize to get work done, as we see in the next chapter.

Notes

1. Lada A. Adamic and Bernardo A. Huberman, “The Nature of Markets in the World Wide Web,” Quarterly Journal of Electronic Commerce 1 (2000): 5–12.

2. www.capatcolumbia.com/Articles/Reports/Grl_260.pdf.

3. Virginia Postrel, “I'm Pro-Choice,” Forbes magazine, March 28, 2005, http://dynamist.com/articles-speeches/forbes/choice.html.

4. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (New York: Random House, 2007), and Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets (New York: Random House, 2005).

5. Dan Frankowski, Dan Cosley, Shilad Sen, Loren Terveen, and John Riedl, “You Are What You Say: Privacy Risks of Public Mentions, paper presented at SIGIR '06, August 6–11, 2006, Seattle, Washington, www.cs.cmu.edu/~wcohen/10-802/fixed/Frankowski_et_al._SIGIR_2006.html.

6. Erik Brynjolfsson, Yu (Jeffrey) Hu, Michael D. Smith, “A Longer Tail?: Estimating the Shape of Amazon's Sales Distribution Curve in 2008,” 2009 Working Paper, http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~bakos/wise/papers/wise2009-p10_paper.pdf.

7. Tom F. Tan and Serguei Netessine, “Is Tom Cruise Threatened? Using Netflix Prize Data to Examine the Long Tail of Electronic Commerce,” Wharton Working Paper, September 16, 2009, http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/papers/1361.pdf.

8. See Ed H. Chi, Niki Kittur, Bryan Pendleton, Bongwon Suh, “Long Tail Of user Participation in Wikipedia,” Xerox PARC blog post, May 15, 2007, http://asc-parc.blogspot.com/2007/05/long-tail-and-power-law-graphs-of-user.html.

9. Clay Shirky, “Institutions versus Collaboration,” TED video, 2005, www.ted.com/talks/clay_shirky_on_institutions_versus_collaboration.html.

10. Distimo App Store census, May 2011, www.distimo.com/.

*An innovative competition sponsored by the video rental firm: Machine learning and other statistical experts competed for a $1 million prize, along with other bonuses, awarded to teams that improved Netflix's algorithmic matching of user attributes with predicted enjoyment of a given movie title.

*DeAndre Cortez Way created a rap career on the basis of an online video (“Crank That,” which reached #1 on the Billboard Hot 100) that spawned countless YouTube tributes and imitations.