CHAPTER 11

Crowds

The Internet is remarkable for its ability for convene groups of people. These groups, which we will call crowds for the sake of convenience, can get work done in two basic ways. The first of these, commonly called crowdsourcing, takes big tasks and divides them among a large number of usually voluntary contributors. Examples would be Amazon Mechanical Turk or Flickr's tagging mechanism to generate words to describe photos. The second function of crowds is to process information with market mechanisms. This function was popularized by James Surowiecki's book on the wisdom of crowds.1

Crowdsourcing: Group Effort

Perhaps the most extraordinary of Linux founder Linus Torvalds's discoveries was not technical but psychological: Given a suitably hard but interesting problem, distributed communities of people will work on it for free. The first decade of the twenty-first century has witnessed the growth of crowdsourcing to include several defining artifacts of the Internet, including Amazon, Facebook, Flickr, and Wikipedia.

Crowds can do amazing things. England's Guardian newspaper was playing catch-up to the rival Telegraph, which had a four-week head start analyzing a mass of public records related to an expense-account scandal in the House of Lords. Once it obtained the records, the Guardian could not wait for its professional reporters to dig through 2 million pages of documentation and still publish anything meaningful. The solution was to crowdsource the data problem: Let citizen-readers look for nuggets of meaningful information.

Twenty thousand volunteers assisted, digging through more than 170,000 documents in 80 hours. Net cost to the newspaper: £50 for temporary server rental (from Amazon) and less than two person-weeks to build the site. By making the hunt for juicy news bits into a game—complete with leaderboards—and making feedback easy, as well as by spicing up the game by using politicians' headshots, the Guardian helped build reader identification with the paper at the same time it found investigative threads for further follow-up.2

Recent scholarship has identified four challenges to successful crowdsourcing:

- How are participants recruited and retained?

- What contributions do participants make?

- How are contributions combined into solutions to a given problem?

- How are users and their contributions evaluated?3

By sorting along these dimensions, several buckets of crowdsourcing emerge.

Evaluating

The simplest tactic is to ask people for their opinion. Amazon product reviews were an important step, but then the site went a step further and asked people to review the reviews. Netflix uses viewer feedback to recommend movies for both the reviewer and for people who share similar preferences. eBay's reputational currency—have buyer and seller been trustworthy in past transactions—is a further use of crowds as evaluators. Rotten Tomatoes builds movie reviews off user ratings.

More recently, Digg and Technorati have refined the evaluation function to rate larger bodies of content, including news items. In addition, with the tagging function, Delicious helped pioneer the evaluation as classification: Rather than merely saying I like it, or I like it 6 stars out of 10, tagging uses masses of community input to say, of a photo, that's a sunset, or of a news story, that's about product recalls. Flickr's community had generated 20 million unique tags as of early 2008; by 2011, the site hosted more than 5 billion images. In contrast to rigid, formal taxonomies, such people-powered “folksonomies” are excellent examples of “good-enough” solutions: Unlike the Library of Congress cataloging system, for example, which is costly, authoritative, and cannot scale without expensive people with esoteric skills, there are no “right” or “wrong” tags on Flickr, only more and less common ones. Crowdsourcing scales to absolutely huge sizes, as we see soon. The behavioral patterns, at scale, of anonymous evaluators are also unpredictable and merit considerable further study.

Sharing

Through a variety of platforms, it has become trivially easy to share information with groups of any size, reaching into the hundreds of millions. The original sharing architecture at scale was probably Napster, in which the material that was shared belonged to other people. Since then, YouTube, Flickr, and blogging tools have expanded the range of possibility beyond words to images and video. An incredible 48 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute as of mid-2011, up from half that sum one year prior. On the downstream side, YouTube records 3 billion page views every day.4

More substantive knowledge can also be shared. Such idea-gathering and problem-solving sites as Innocentive and NineSigma pose hard business and engineering problems on behalf of such clients as Eli Lilly and Procter & Gamble. The power is in a very small number of people who can speak to the issue, not a mass of worker bees. More recently, Quora launched a question-based site that is hybrid of broad- and narrow-casting: Expertise self-selects and answers are voted up or down by subsequent readers. Anyone can post any question, but getting experts' attention is something of an art form. The richness of the conversations, across an amazing variety of topics, is stunning, and to date no money changes hands.

Creativity is a further category of sharing. Threadless solicits T-shirt design ideas and prints and sells the most popular ones. Quirky crowd-sources new product development, soliciting both original ideas and influential changes to those concepts. Both iStockphoto and Flickr get the work of photographers into the hands of massive audiences. In all cases, recognition is one major currency of motivation.

Networking

Compare, for a moment, Facebook to Yahoo of 1998. What, really, does Facebook deliver? In contrast to free e-mail, horoscopes, weather, classified ads, maps, stock quotes, and an abundance of other content, Facebook builds only an empty lattice, to be populated with the life histories, opinions, photos, and interactions of its 600 million-plus members. LinkedIn, MySpace (for a time), Orkut, and the rest of the social networking sites can also be viewed through the lens of crowdsourcing. That is, they answer the four questions with a compelling combination of good engineering, chutzpah (regarding privacy), networked innovation (in games and charitable contributions especially), editorial and related rule setting, and, most crucially, major network effects: The more of my friends who join, the more compelled I am to become a member.

Building

Linux and Wikipedia possess a structure that separates them from other types of sites. By building an “architecture of participation,” to use the technical publisher Tim O'Reilly's apt phrase,5 these efforts have shown the way for what Harvard law professor Yochai Benkler (see Chapter 8) has called “commons-based peer production.”6 Nobody is “in charge,” in that tasks are taken up voluntarily in response to self-identified needs. Multiple efforts might be directed at the same issue, making crowdsourcing “wasteful” of resources when viewed from a traditional managerial perspective. As we saw in regard to long tails, however, there is room in these participatory architectures for both heavy contributors and extremely casual ones.

Much like natural selection, competing solutions can be compared or possibly interbred to create “offspring” with the best characteristics of the previous-generation donor ideas. When Darwinian struggle does ensue (check the Wikipedia edits history for some sense of how vigorous these contests can be), the overall intellectual quality of the effort is usually the winner. The quality of Linux, particularly in the domains most valued by its user-builders—robustness and security—testifies to the magic of the crowdsourced approach.

A different approach to writing code is to turn it into a game, specifically a contest. TopCoder takes software tasks and breaks them into chunks, with specific performance criteria. Prize money goes to the top two entries in most cases. Importantly, a subsequent contest for the community, which currently numbers more than 300,000, is to test the winning code. Programmers compete not just for money but also (yet again) peer recognition. In a classic two-sided platform play, TopCoder attracks both talented programmers but also top-shelf clients including NASA, Eli Lilly, and the National Security Agency. Such interest comes because the model works: Defects run well below the industry average while project completion is about 50% faster.7

Grunt Work

Finally, crowds can do mundane tasks in networks of undifferentiated contributors. The SETI@home project, in which computing cycles were harvested from screen savers to chug through terabytes of radiotelegraphic space noise in the search for life outside earth, is crowdsourcing of people's computers. The zombie-bot networks of exploited machines that generate spam or denial-of-service attacks constitute a dark-side example of crowdsourcing, albeit involuntary.

Amazon's Mechanical Turk (named for an eighteenth-century chess-playing automaton with a human hidden inside) delegates what it calls HITs: Human Intelligence Tasks. Naming the subjects of a photograph is a classic example, as is scanning aerial photographs for traces of wreckage, as when the noted balloonist and pilot Steve Fossett crashed in Nevada.8 The Guardian example noted earlier shows how random volunteers, needing no special expertise or creativity, can help parse large data sets.

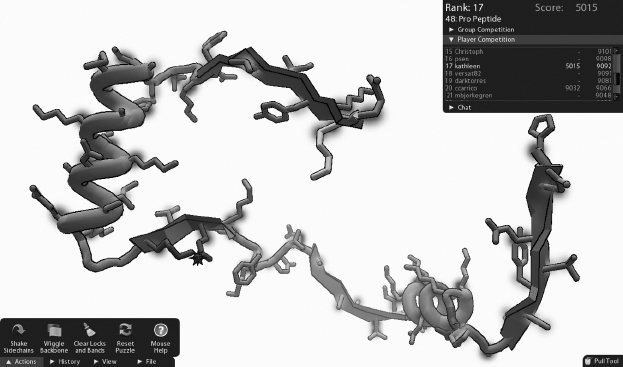

FIGURE 11.1 Foldit: An Online Game that Lets Crowds Try to Solve Biochemical Puzzles

Source: University of Washington Center for Game Science.

Grunt work can be fun, for the right people. Scientists at the University of Washington have helped create a 3-D online game called Foldit to apply human ingenuity, at a mass scale, to protein folding problems: People, it turns out, are better at spatial reasoning than computers. (See Figure 11.1.) Before drugs can be designed, the crystal structure of the target must be understood. In 2011, the game helped solve the structure of a protein that is related to the AIDS virus. Three different players made key contributions on which the research team could build. The structure of the M-PMV retroviral protease had been a mystery for roughly a decade; the gamers helped solve it in 16 days.9

Information Markets and Other Crowd Wisdom

Crowds also can accomplish work through market mechanisms. We've seen markets process information for a long time: When the National Basketball Association addressed the scandal surrounding its referee Tim Donaghy*, the situation highlighted the secrecy with which the league assigns refs to games. Referees are prohibited from telling anyone but immediate family about travel plans, because the Las Vegas point spread moves if the refereeing crews are revealed ahead of game time. That point spread is a highly nuanced information artifact of a market compensating for new information about relevant inputs to the outcome of a game.

Information markets hold great potential but, like real markets, suffer from bubbles, information asymmetry, and other externalities. Nevertheless, such exemplars as Hollywood Stock Exchange (HSX) (now owned by financial information giant Cantor Fitzgerald), the Iowa Electronic Markets (IEM) for political futures, and start-ups like Fluid Innovation are leading the way toward wider implementation.

It seems clear that U.S. financial markets suffered an extended aftermath of an inflated mortgage-products market, but it turns out that financial scholars can't agree on what a bubble is. According to Cornell University's Maureen O'Hara in the Review of Financial Studies,10 the “less controversial” approach is to follow one scholar's mild assertion that “bubbles are typically associated with dramatic asset price increases, followed by a collapse.” Begging the question of what constitutes a collapse, the issue for our purposes concerns the potential for bubble equivalents in information markets. It's worth discussing some of the larger issues.

How Do Crowds Express Wisdom or, to Use a Less Loaded Phrase, Process Information?

Several ways of processing information come to mind. In many cases, crowdsourcing and information markets overlap when enough tags have been contributed, or enough votes tabulated, to give the recommendation the weight of an informal market mechanism:

- Voting, whether officially in the process of politics, or unofficially with product reviews, Digg or similar feedback (“Was this review helpful?”). All of these actions are voluntary and unsolicited, making statistical significance a moot point.

- Surveys, constructed with elaborate statistical tools and focused on carefully focused questions. Interaction among respondents is usually low, making surveys useful in collecting independent opinions.

- Convened feedback, a catch-all that includes tagging, blogs and comments, message boards, trackbacks, wikis, and similar vehicles. Once again, the action is voluntary, but the field of play is unconstrained. Compared to the other three categories, convened feedback can contain substantial noise, but its free form allows topics to emerge from the group rather than from the pollster, market maker, or publisher.

- Betting, the putting of real (as at IEM) or imagined (at HSX) currency where one's mouth is. Given the right kind of topic and the right kind of crowd, this process can be extremely powerful, albeit with constrained questions. We will focus on the market process for the remainder of our discussion.

What Kinds of Questions Best Lend Themselves to Group Wisdom?

On this topic of targets for collective information processing Surowieki is direct: “Groups are only smart when there is a balance between the information that everyone in the groups shares and the information that each of the members of the group holds privately.” Conversely, “what happens when [a] bubble bursts is that the expectations converge.”11 In contests and other group effort scenarios such as those noted earlier, bubbles are less of an issue, but markets as processing mechanisms appear to have this particular weakness.

Cass Sunstein, a University of Chicago law professor when he wrote it, agrees in his book Infotopia.12 He states: “This is the most fundamental limitation of prediction markets: They cannot work well unless investors have dispersed information that can be aggregated.” Elsewhere in a blog post he notes that in an informal experiment with University of Chicago law professors, the crowd came extremely close to the weight of the horse that won the Kentucky Derby, did “pretty badly” on the number of lines in Shakespeare's Antigone, and performed “horrendously” when asked the number of Supreme Court invalidations of state and federal law. He speculates that markets employ some self-selection bias: “[P]articipants have strong incentives to be right, and won't participate unless they think they have something to gain.”13

The best questions for prediction markets, then, involve issues about which people have formed independent judgments and on which they are willing to stake a financial and/or reputational investment. It may be that the topics cannot be too close to one's professional interests, as the financial example would suggest, and in line with the accuracy of the HSX Oscar predictions, which traditionally run about 85%.

Where Is Error Introduced?

The French political philosopher Condorcet (1743–1794) originally formulated the jury theorem that explains the wisdom of groups of people, when each individual is more than 50% likely to be right. Bad things happen when people are less than 50% likely to be right, however, at which time crowds then amplify error.

Numerous experiments have shown that group averages suffer when participants start listening to outside authorities or to each other. What Sunstein called “dispersed information” and what Surowiecki contrasts to mob behavior—independence—is more and more difficult to find. Many of the start-ups in idea markets include chat features—they are, after all, often social networking plays—making for yet another category of echo chamber.

Another kind of error comes when predictions ignore randomness. Particularly in thickly traded markets with many actors, the complexity of a given market can expose participants to phenomena for which there is no logical explanation—even though many will be offered. As Nassim Nicholas Taleb pointed out in The Black Swan, newswire reports on market movement routinely and fallaciously link events and price changes: It's not uncommon to see the equivalent of both “Dow falls on higher oil prices” and “Dow falls on lower oil prices” headlines during the same day.14

Varieties of Market Experience

Some of the many businesses seeking to monetize prediction markets are listed next.

- Newsfutures (now Lumenogic) makes a business-to-business play, building internal prediction markets for the likes of Eli Lilly, the Department of Defense, and Yahoo.

- Spigit sells as enterprise software to support internal innovation and external customer interaction. Communities are formed to collect and evaluate new ideas.

- Intrade is an Irish firm that trades in real money (with a play money sandbox) applied to questions in politics, business (predictions on market share are common), entertainment, and other areas. The business model is built on small transaction fees on every trade.

- Other prediction markets or related efforts focus on sports. YooNew was a futures market in sports tickets that suffered in the aftermath of the 2008 credit crunch. Hubdub used to be a general-purpose prediction market but it has since tightened its focus.

Apart from social networking plays and predictions, seemingly trivial commitments to intellectual positions work elsewhere. Sunstein's more recent book, called Nudge, was coauthored with the Chicago behavioral economist Richard Thaler.15 It points to the value of commitment for such personal behaviors as weight loss or project fulfillment. For example, a PhD candidate, already hired as a lecturer at a substantial discount from an assistant professor's salary, was behind on his dissertation. Thaler made him write a $100 check at the beginning of every month a chapter was due. If the chapter came in on time, the check was ripped up. If the work came in late, the $100 went into a fund for a grad student party to which the candidate would not be invited. The incentive worked, notwithstanding the fact that $400 or $500 was a tiny portion of the salary differential at stake. A Yale economics professor who lost weight under a similar game has cofounded stickK.com, an ad-funded online business designed to institutionalize similar “commitment contracts.” These commitments are a particular form of crowdsourcing, to be sure, but the combination of both real and reputational currencies with networked groups represents a consistent thread with more formal market mechanisms.

Looking Ahead

It's clear that crowds can in fact be smart when the members don't listen to each other too closely. It's also clear that financial and/or reputational investment are connected to both good predictions and fulfilled commitments. Several other issues are less obvious. Is there a novelty effect with prediction markets? Will clever people and/or software devise ways to game the system, similar to short-selling in finance or sniping on eBay? What do prediction bubbles look like, and what are their implications? When are crowds good at answering questions and when, if ever, are they good at posing them? (Note that on most markets, individuals can ask questions, not groups.) Can we reliably predict whether a given group will predict wisely?

At a larger level, how do online information markets relate to older forms of group expression, particularly voting? In the United States, the filtration of a state's individual votes through the winner-take-all Electoral College is already controversial (currently only Maine and Nebraska allot their votes proportionately), and so-called National Popular Vote legislation has been in states with 77 electoral votes—not yet enough to overturn the current process. Will some form of prediction market or other crowd wisdom accelerate or obviate this potential change?

Any process that can, under the right circumstances, deliver such powerful results will surely have unintended consequences. The controversy over John Poindexter's Futures Markets Applied to Prediction (FutureMAP) program, which was canceled by DARPA* in July 2003, will certainly not be the last of the tricky issues revolving around this class of tools.16

As blogging, social networking, and user-generated content proliferate, we're seeing one manifestation of a larger trend toward delegitimization of received cultural authority. Doctors are learning how to respond to patients with volumes of research, expert and folk opinion, and a desire to dictate rather than receive treatment. Instead of trusting politicians, professional reviewers, or commercial spokespeople, many people across the world are putting trust in each other's opinions: Zagat is a great example of “expert” ratings systems being challenged by masses of uncredentialed, anonymous diners.

Zagat also raises the issue of when crowds can be “wise,” cannot possibly be “wise,” or generally do not matter one way or the other: For all the masses of opinions coalescing online, at the end of the day, how many serve any purpose beyond amplified venting? At the same time, businesses are getting more skilled in harvesting the wisdom of crowds, so while there will always be anonymous noise, mechanisms are emerging to collect the value of people's knowledge and instincts.

Notes

1. James Surowiecki, The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economies, Societies and Nations (New York: Doubleday, 2004).

2. Michael Andersen, “Four Crowdsourcing Lessons from the Guardian's (Spectacular) Expenses-Scandal Experiment,” Niemen Journalism Lab blog, Harvard University, June 23, 2009, www.niemanlab.org/2009/06/four-crowdsourcing-lessons-from-the-guardians-spectacular-expenses-scandal-experiment/.

3. Anhai Doan, Raghu Ramakrishnam, and Alon Y. Halevy, “Crowdsourcing Systems on the World-Wide Web,” Communications of the ACM 54 (April 2011): 88.

4. “Thanks, YouTube community, for two BIG gifts on our sixth birthday!” Youtube, May 25, 2011, http://youtube-global.blogspot.com/2011/05/thanks-youtube-community-for-two-big.html.

5. Tim O'Reilly, “The Architecture of Participation,” June 2004, http://oreilly.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/articles/architecture_of_participation.html.

6. Yochai Benkler, The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 206), p. 60.

7. Alpheus Bingham, and Dwayne Spradlin, The Open Innovation Marketplace: Creating Value in the Challenge-Driven Enterprise (London: FT Press, 2011), pp. 158–161.

8. Michael Arrington, “Search for Steve Fossett Expands to Amazon's Mechanical Turk,” TechCrunch blog, September 8, 2007, http://techcrunch.com/2007/09/08/search-for-steve-fossett-expands-to-amazons-mechanical-turk/.

9. Kyle Niemeyer, “Gamers Discover Protein Structure that Could Help in War on HIV,” Ars Technica, September 21, 2011, http://arstechnica.com/science/news/2011/09/gamers-discover-protein-structure-relevant-to-hiv-drugs.ars.

10. Maureen O'Hara, “Bubbles: Some Perspectives (and Loose Talk) from History,” Review of Financial Studies 21, no. 1 (2008): 11–17. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1151603.

11. Surowiecki, Wisdom of Crowds, pp. 255–256.

12. Cass R. Sunstein, Infotopia: How Many Minds Produce Knowledge (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 136–137.

13. “Are Crowds Wise?” Lessig blog post, July 19, 2005, http://lessig.org/blog/2005/07/are_crowds_wise.html.

14. Taleb, The Black Swan, p. 74.

15. Thaler and Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness (New York: Penguin, 2009).

16. www.iwar.org.uk/news-archive/tia/futuremap-program.htm.

*Tim Donaghy resigned from his position as a National Basketball Association referee when it was found that he had bet on games he officiated (and whose outcome he presumably affected). He later served time in federal prison for his role in a larger betting scandal.

*Founded in 1958 in response to Sputnik, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency serves as the research and development function for the U.S. Department of Defense. Its work led to GPS, the Internet, both stealth and unmanned aviation technologies, and other still-classified innovations.