The very moment Apple announced in 2006 that all new Mac models would come with Intel chips inside, the geeks and the bloggers started going nuts. “Let’s see,” they thought. “Macs and PCs now use exactly the same memory, hard drives, monitors, mice, keyboards, networking protocols, and processors. By our calculations, the Mac should be able to run Windows!”

Now, some in the Cult of Macintosh were revolted by the very idea. Who on earth, they asked, wants to pollute the magnificence of the Mac with a headache like Windows?

Lots of people, as it turns out. Millions of switchers have been tempted by the Mac’s sleek looks, yet worried about leaving Windows behind entirely. Then there are the people who love Apple’s iLife programs, but have jobs that rely on Microsoft Access, Outlook, or some other piece of Windows corporateware. Even true-blue Mac fans occasionally look longingly at some of the Windows-only games, Web sites, palmtop sync software, or movie download services they thought they’d never be able to use.

Today, there are two ways to run Windows on a Mac with an Intel chip:

Restart it in Boot Camp. Boot Camp lets you restart your Mac into Windows. At that point, it’s a full-blown Windows PC, with no trace of the Mac on the screen. It runs at 100 percent of the speed of a real PC, because it is one. Compatibility with Windows software is excellent. The only drag is that you have to restart the Mac again to return to the familiar world of Mac OS X and all your Mac programs and files.

Run Windows in a window. For $80 or so, you can buy a program like Parallels or VMWare Fusion, which lets you run Windows in a window.

You’re still running Mac OS X, and all your Mac files and programs are still available. But you’ve got a parallel universe—Microsoft Windows—running in a window simultaneously.

Compared with Boot Camp, this virtualization software offers only 90 percent of the speed and 90 percent of the software compatibility. But for thousands of people, the convenience of eliminating all those restarts—and gaining the freedom to copy and paste documents between Mac OS X and Windows programs—makes the Windows-in-a-window solution nearly irresistible.

Tip

There’s nothing wrong with using both on the same Mac, by the way. In fact, the Parallels/VMWare-type programs can use the same copy of Windows as Boot Camp, so you save disk space and don’t have to manage two different Windows worlds.

Both techniques require you to provide your own copy of Windows. And both are described on the following pages.

Note

Remember, running Windows smoothly and fast requires a Mac with

an Intel chip inside. To find out if yours does, choose

![]() →About This Mac. In the resulting dialog box,

you’ll see, next to the label Processor, either “Intel” something or

“PowerPC.”

→About This Mac. In the resulting dialog box,

you’ll see, next to the label Processor, either “Intel” something or

“PowerPC.”

If your Mac has a PowerPC chip, skip this chapter. There are programs that let you run Windows, but excruciatingly slowly. Frankly, it’s not worth the effort.

To set up Boot Camp, you need the proper ingredients:

An Intel-based Mac. All Mac models introduced in 2006 and later have Intel chips inside.

A copy of Windows XP or Windows Vista. Windows XP needs Service Pack 2. If you have an earlier copy, you’re not totally out of luck, but you’ll need a hacky approach, which you can read about online. Let Google be your friend.

For Windows Vista, you need the Home Basic, Home Premium, Business, or Ultimate Edition. In both cases, an Upgrade disc won’t work; you need a full-installation copy. Also, Boot Camp requires the normal 32-bit editions of Windows. The fancy 64-bit versions won’t work.

At least 10 gigs of free hard drive space.

Then you’re ready to proceed.

Open your Applications→Utilities folder. Inside, open the program called Boot Camp Assistant.

On the Introduction screen, you can print the instruction booklet, if you like (although the following pages contain the essential info). There’s a lot of good, conservative legalese in that booklet: the importance of backing up your whole Mac before you begin, for example.

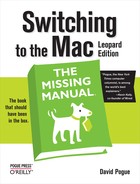

When you click Continue, you get the dialog box shown in Figure 8-1—the most interesting part of the whole process.

Figure 8-1. How much hard drive space do you want to dedicate to your “PC”? It’s not an idle question; whatever you give Windows is no longer available for your Mac. Drag the vertical handle between the Mac and Windows sides of this diagram.

You’re being asked to partition—subdivide—your hard drive (which can’t be partitioned already), setting aside a certain amount of space that will hold your copy of Windows and all the PC software you decide to install. This partitioning process doesn’t involve erasing your whole hard drive; all your stuff is perfectly safe.

The dialog box offers handy buttons like Divide Equally and Use 32 Gigs, but it also lets you drag a space-divider handle, as shown in Figure 8-1, to divide up your drive space between the Mac and Windows sides.

Here’s where things get tricky, though. If you choose an amount less than 32 gigabytes for the Windows partition, the Windows XP installer lets you choose between two Windows drive formats:

FAT32. This unappetizingly named scheme is older and, if you ask power users and network nerds, more limited. For example, it’s only available on disks smaller than 32 gigabytes.

But the advantage of using FAT32 is that, when it’s all over, you’ll be able to drag files back and forth from the Windows side to the Mac side. (This works only when you’re in Mac OS X; when you’re in Windows, you can’t see the Mac side of the hard drive without a commercial program like MacDrive [www.macdrive.com].)

NTFS. If you choose a partition size greater than 32 GB, you must use the NT File System. It’s a more modern, flexible formatting scheme—it offers goodies like file-by-file access permissions, built-in file compression and encryption, journaling (a safety feature), and so on.

But on a Boot Camp Mac, NTFS is a drag. It means that when you’re running from the Mac side, you can see what’s on the Windows partition, but can’t add, remove, or change any files.

Note

All this applies only to Windows XP. Windows Vista always uses NTFS. You don’t have a choice.

Most people choose to dedicate a swath of the main internal hard drive to the Windows partition. But if you have a second internal hard drive, you can also choose one of these options:

Create a Second Partition. The Boot Camp Assistant carves out a Windows partition from that drive.

Erase Disk and Create a Single Partition for Windows. Just what it says.

On the Start Windows Installation screen, you’re supposed to—hey!—start the Windows installation. Grab your Windows XP or Vista disc and slip it into the Mac. Its installer goes to work immediately.

Following the “I agree to whatever Microsoft’s lawyers say” screen, Microsoft’s installer asks partition you want to put Windows on. It’s really important to pick the right one. Play your cards wrong, and you could erase your whole Mac partition. So:

Windows XP. Choose the partition (by pressing the up or down arrow keys) called “C: Partition3 <BOOTCAMP>.”

Windows Vista. Choose the one called “Disk 0 Partition 3 BOOTCAMP.”

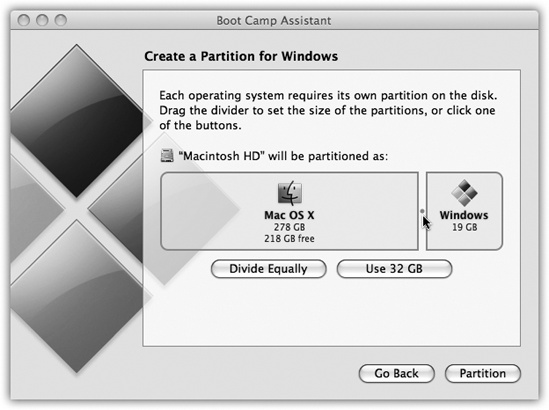

When you press Enter, you now encounter another frightening-looking screen (Figure 8-2). Here, Windows invites you to format the new partition.

Windows XP. If your Windows partition is less than 32 gigs, you get to choose between FAT32 or NTFS —a decision that, presumably, you’ve already made, having read the previous pages. Proceed as shown in Figure 8-2.

Windows Vista. Click “Drive options (advanced),” click Format, click OK, and finally click Next. Your Windows partition is now formatted for NTFS, like it or not.

Now a crazy, disorienting sight presents itself: Your Mac,

running Windows. There’s no trace of the familiar desktop, Dock,

or ![]() menu; it’s Windows now, baby.

menu; it’s Windows now, baby.

Walk through the Windows setup screens, creating an account, setting the time, and so on.

At this point, the Mac is actually a true Windows PC. You can install and run all your old Windows programs, utilities, and even games; you’ll discover that they run really fast and well.

But as you probably know, every hardware feature of a Windows requires a driver—a piece of software that tells the machine how to communicate with its own monitor, networking card, speakers, and so on. And it probably goes without saying that Windows doesn’t come with any drivers for Apple’s hardware components.

That’s why, at this point, you’re supposed to insert your Leopard installation DVD; it contains all of the drivers for the Mac’s graphics card, Ethernet and AirPort networking, audio input and output, AirPort wireless antenna, iSight camera, brightness and volume keys, Eject key, and Bluetooth transmitter. When this is all over, your white Apple remote control will even work to operate iTunes for Windows.

(It also installs a new Control Panel icon and system-tray pop-up menu, as described later in this chapter.)

Note

Unbeknownst to you, this DVD is actually a dual-mode disc. When you insert it into a Mac running Mac OS X, it appears as the Leopard installer you know and love. But when you slip it into a PC, its secret Windows partition appears—and automatically opens the Mac driver installer!

When you insert the Leopard disc, the driver installer opens and begins work automatically. Click past the Welcome and License Agreement screens, and then click Install. You’ll see a lot of dialog boxes come and go; just leave it alone (and don’t click Cancel).

A few words of advice:

If you see, “The software you are installing has not passed Windows Logo testing,” click Continue Anyway. (As if Apple’s going to pay Microsoft to have its software certified for quality!)

If the installation seems to stall, Windows may be waiting for you to click OK or Next in a window that’s hidden behind other windows. Inspect the taskbar and look behind open windows.

Windows XP concludes by presenting the Found New Hardware Wizard. Go ahead and agree to update your drivers.

When it’s all over, a dialog box asks you to restart the computer; click Restart. When the machine comes to, it’s a much more functional Windows Mac. (And it has an online Boot Camp Help window waiting for you on the screen.)

From now on, your main interaction with Boot Camp will be telling it what kind of computer you want your Mac to be today: a Windows machine or a Mac.

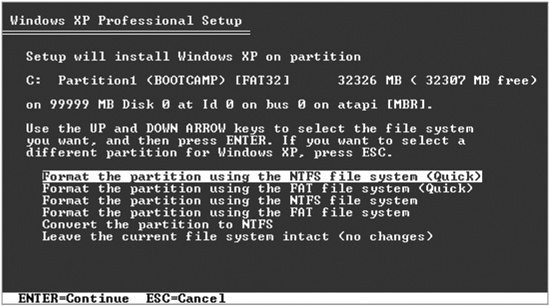

Presumably, though, you’ll prefer one operating system most of the time. Figure 8-3 (top and middle) shows how you specify your favorite.

Tip

If you’re running Windows and you just want to get back to Mac OS X right now, you don’t have to bother with all the steps shown in Figure 8-3. Instead, click the Boot Camp system-tray icon and, from the shortcut menu, choose Restart in Mac OS X.

From now on, each time you turn on the Mac, it starts up in the operating system you’ve selected.

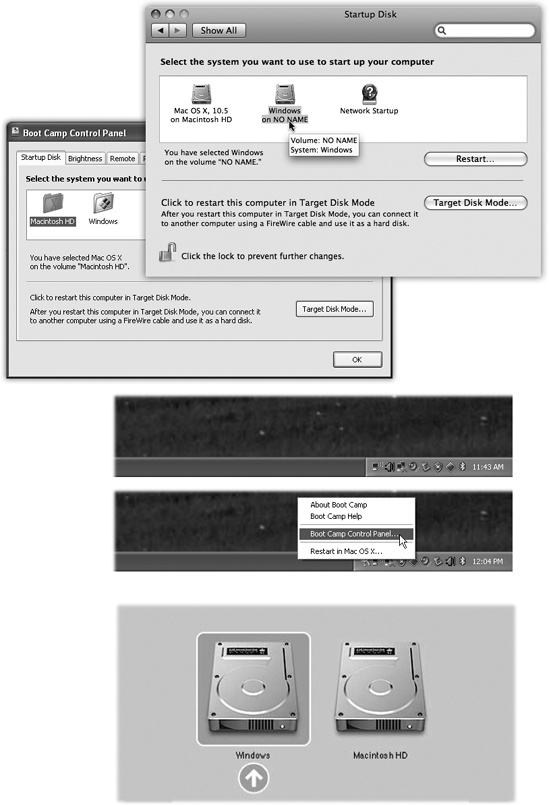

If you ever need to switch—when you need Windows just for one quick job, for example—press Option key as the Mac is starting up. You’ll see something like the icons shown in Figure 8-3 (bottom).

Tip

To upgrade to Windows Vista: Restart your Mac using Windows. Insert your Vista installation or upgrade disc.

Follow the instructions that came with Vista.

A Mac keyboard and a Windows keyboard aren’t the same. Each has keys that would strike the other as extremely goofy. So if you’re trying to trigger a familiar Windows keystroke, you might find this substitution guide handy:

Windows Keystroke | Apple keyboard |

|---|---|

Control-Alt-Delete | Control-Option-Delete |

Alt | Option |

Backspace | Delete |

Delete (forward delete) | |

Enter | Return or Enter |

Num lock | Clear (laptops: Fn-F6) |

Print Screen | F14 (laptops: Fn-F11) |

Print active window | Option-F14 (laptops: Option-Fn-F11) |

Alt key | Option key |

Similarly, the Alt key is the Windows equivalent of the Option key.

Tip

You know that awesome two-finger scrolling trick on Mac laptops (Desktop Pictures (Wallpaper))? Guess what? It works when you’re running Windows, too.

Figure 8-3. Top: To choose your preferred operating system—the one that

starts up automatically unless you intervene—choose

![]() →System Preferences. Click Startup Disk, and

then click the icon for either Mac OS X or Windows. Next, either

click Restart (if you want to switch right now) or close the

panel. The identical controls are available when you’re running

Windows, thanks to the new Boot Camp Control Panel. Middle: To

open the Boot Camp control panel, choose its name from its new

icon in the Windows system tray. Bottom:This display, known as the

Startup Manager, appears when you press Option during startup. It

displays all the disk icons, or disk partitions, that contain

bootable operating systems. Just click the name of the partition

you want, and then click the Continue arrow.

→System Preferences. Click Startup Disk, and

then click the icon for either Mac OS X or Windows. Next, either

click Restart (if you want to switch right now) or close the

panel. The identical controls are available when you’re running

Windows, thanks to the new Boot Camp Control Panel. Middle: To

open the Boot Camp control panel, choose its name from its new

icon in the Windows system tray. Bottom:This display, known as the

Startup Manager, appears when you press Option during startup. It

displays all the disk icons, or disk partitions, that contain

bootable operating systems. Just click the name of the partition

you want, and then click the Continue arrow.

And now, the finer points of Boot Camp...

When you’re running Mac OS X, you can get to the documents you created while you were running Windows, which is a huge convenience. Just double-click the Windows disk icon (called NO NAME or Untitled), and then navigate to the Documents and Settings→[your account name]→My Documents (or Desktop).

If you formatted your Windows XP partition using the FAT format as described earlier, you can copy files to or from this partition, and even open them up for editing on the Mac side. If you used NTFS, though, you can only copy them to the Mac side, or open them without the ability to edit them.

Tip

Actually, there’s no reason your Windows “drive” has to be called NO NAME or Untitled. You can rename it as you would any other icon, either in Windows or in Mac OS X. (That’s if you used the FAT format. If you used NTFS, you can’t change the name in Mac OS X.)

On the other hand, while you’re running Windows, you generally can’t access your Mac files; Windows doesn’t even see the Mac hard drive.

One way to around this is to buy a $50 program called MacDrive (www.mediafour.com).

Another solution: use a disk that both Mac OS X and Windows “see,” and keep your shared files on that. A flash drive works beautifully for this. So does your iDisk (.Mac Services) or a shared drive on the network.

The problem with Boot Camp is that every time you switch to or from Windows, you have to close down everything you were working on and restart the computer. You lose two or three minutes each way. And you can’t copy and paste between Mac and Windows programs.

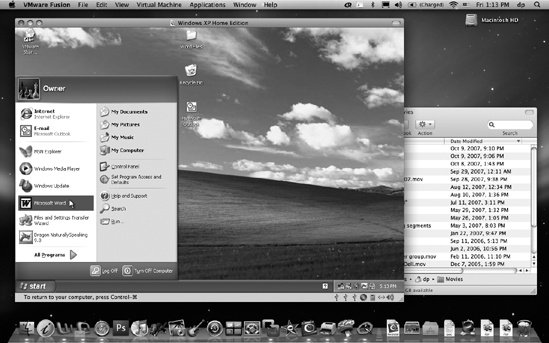

There is another way: an $80 utility called Parallels Workstation for Mac OS X (www.parallels.com), and its $80 rival, VMWare Fusion (www.vmware.com). These programs let you run Windows and Mac OS X simultaneously; Windows hangs out in a window of its own, while the Mac is running Mac OS X (Figure 8-4). You’re getting about 90 percent of Boot Camp’s Windows speed—not fast enough for 3-D games, but plenty fast for just about everything else.

Figure 8-4. The strangest sight you ever did see: Mac OS X and Windows XP. On the same screen. At the same time. Courtesy of VMWare Fusion. Parallels is very similar.

Once again, you have to supply your own copy of Windows for the installation process. This time, though, it doesn’t have to be Windows XP or Vista. It can be any version of Windows, all the way back to Windows 3.1—or even Linux, FreeBSD, Solaris, OS/2, or MS-DOS.

Virtualization software on an Intel Mac is a beautiful thing. You can be working on a design in iWork, duck into a Microsoft Access database (Windows only), look up an address, copy it, and paste it back into the Mac program.

And what if you can’t decide whether to use Boot Camp (fast and feature-complete, but requires restarting) or Parallels/Fusion (fast and no restarting, but no 3-D games)? No problem—install both. They coexist beautifully on a single Mac, and can even use the same copy of Windows.

Together, they turn the Intel-based Macintosh into the Uni-Computer: the single machine that can run nearly 100 percent of the world’s software catalog.

Mastering Parallels or Fusion means mastering Windows, of course, but it also means mastering these tips:

You don’t have to run Windows in a window. With one keystroke, you can make your Windows simulator cover the entire screen. You’re still actually running two operating systems at once, but the whole Mac world is hidden for the moment so you can exploit your full screen. Just choose View→Full Screen.

Conversely, both Parallels and Fusion offer something called Coherence or Unity mode, in which there’s no trace of the Windows desktop. Instead, each Windows program floats in its own disembodied window, just like a Mac program; the Mac OS X desktop lies reassuringly in the background.

Tip

In Fusion’s Unity mode, you can access your Computer, Documents, Network, Control Panel, Search, and Run commands right from Fusion’s Dock icon or launch palette, so you won’t even care that there’s no Start menu.

In Parallels, press Alt+Ctrl+Shft to enter or exit Coherence mode. In Fusion, hit Ctrl-

-U for Unity mode.

-U for Unity mode.To send the “Three-Fingered Salute” when things have locked up in Windows (usually Ctrl+Alt+Delete), press Control-Option-

(Fusion) or Ctrl+Fn+Alt+Delete

(Parallels). Or use the Send Ctrl-Alt-Delete command in the

menus.

(Fusion) or Ctrl+Fn+Alt+Delete

(Parallels). Or use the Send Ctrl-Alt-Delete command in the

menus.You can drag files back and forth between the Mac and Windows universes. Just drag icons into, or out of, the Windows window.

If you have a one-button mouse, you can “right-click” in Parallels by Control-Shift-clicking. In Fusion, Control-click instead. On Mac laptops, you can right-click by putting two fingers on the trackpad as you click (Trackpad Gestures).

When you quit the virtualization program, you’re not really “shutting down” the PC; you’re just suspending it, or putting it to sleep. When you double-click the Parallels/VMWare icon again, everything in your Windows world is exactly as you left it.

Your entire Windows universe of files, folders, and programs is represented by a single file on your hard drive. In Parallels, it’s in your Home→Library→Parallels folder. In Fusion, it’s in your Home→Documents→Virtual Machines folder.

That’s super convenient, because it means that you can back up your entire Windows “computer” by dragging a single icon to another drive. And if your Windows world ever gets a virus or spyware infestation, you can drag the entire thing to the Trash—and restore the entire thing from that clean backup.