In an era when security is the hottest high-tech buzzword, Apple was smart to make security a focal point for Leopard. Mac OS X was already virus-free and better protected from Internet attacks than Windows. But Mac OS X 10.5 is the most impenetrable Mac system yet, filled with new defenses against the dark arts.

On the premise that the biggest security threat of all comes from other people in your home or office, though, the most important security feature in Mac OS X is the accounts system.

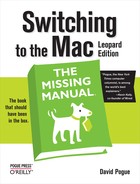

The concept of user accounts is central to Mac OS X’s security approach. Like the Unix under its skin (and also like Windows XP and Vista), Mac OS X is designed from the ground up to be a multiple-user operating system. You can configure a Mac OS X machine so that everyone must log in—that is, you have to click or type your name and type in a password—when the computer turns on (Figure 13-1).

Upon doing so, you discover the Macintosh universe just as you left it, including your documents, files, and folders; your preference settings (Web browser bookmarks, desktop picture, screen saver, icons on the desktop and in the Dock, and so on); email account(s), including personal information and mailboxes; your personally installed programs and fonts; your choice of programs that launch automatically at startup; and so on.

This system means that several different people can use it throughout the day, without disrupting each other’s files and settings. It also protects the Mac from getting fouled up by mischievous (or bumbling) students, employees, and hackers.

If you’re the only person who uses your Mac, you can safely skip most of this chapter. The Mac never pauses at startup time to demand the name and password you made up when you installed Mac OS X, because Apple’s installer automatically turns on something called automatic login (Setting Up the Login Process). You will be using one of these accounts, though, whether you realize it or not.

Furthermore, when you’re stuck in line at the Department of Motor Vehicles, you may find the concepts presented here worth skimming, as certain elements of this multiple-user system may intrude upon your solo activities—and figure in the discussions in this book—from time to time.

Tip

Even if you don’t share your Mac with anyone and don’t create any other accounts, you might still be tempted to learn about the accounts feature because of its ability to password-protect the entire computer. All you have to do is to turn off the automatic login feature described in Setting Up the Login Process. Thereafter, your Mac is protected from unauthorized fiddling when you’re away from your desk or when your laptop is stolen.

Figure 13-1. When you set up several accounts, you don’t turn on the Mac

so much as sign into it. A command in the ![]() menu called Log Out summons this sign-in

screen, as does the Accounts menu described later in this chapter.

Click your own name, and type your password (if any), to get past

this box and into your own stuff.

menu called Log Out summons this sign-in

screen, as does the Accounts menu described later in this chapter.

Click your own name, and type your password (if any), to get past

this box and into your own stuff.

When you first installed Mac OS X, you were asked for a name and password. You may not have realized it at the time, but you were creating the first user account on your Macintosh. Since that fateful day, you may have made a number of changes to your desktop—adjusted the Dock settings, added some favorites to your Web browser, and so on—without realizing that you were actually making these changes only to your account.

You’ve been saving your documents into your own Home folder, which is the cornerstone of your own account. This folder, generally named after you and stashed in the Users folder on your hard drive, stores not only your own work, but also your preference settings for all the programs you use, special fonts that you’ve installed, your own email collection, and so on.

Now then: Suppose you create an account for a second person. When she turns on the computer and signs in, she finds the desktop exactly the way it was factory-installed by Apple—stunning Earth-in-space desktop picture, Dock along the bottom, the default Web browser home page, and so on. She can make the same kinds of changes to the Mac that you’ve made, but nothing she does affects your environment the next time you log in.

In other words, the multiple-accounts feature has two components: first, a convenience element that hides everyone else’s junk; and second, a security element that protects both the Mac’s system software and everybody’s work.

Suppose somebody new joins your little Mac family—a new worker, student, or love interest, for example. And you want to make them feel at home on your Mac.

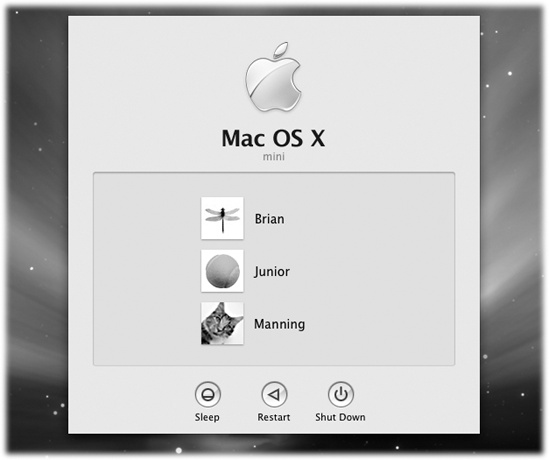

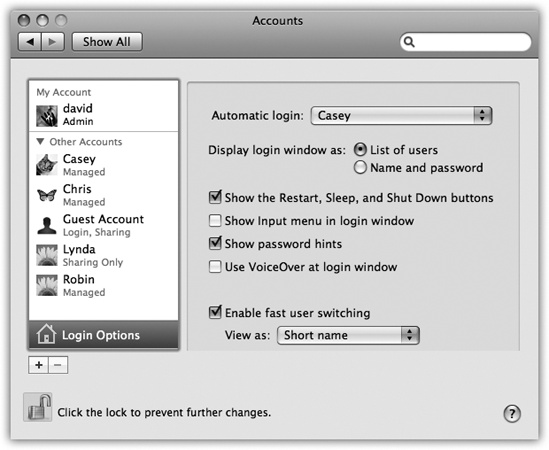

Begin by opening System Preferences (Chapter 15). In the System Preferences window, click Accounts. You have just arrived at the master control center for account creation and management (Figure 13-2).

To create a new account, start by unlocking the Accounts panel.

That is, click the ![]() at lower-left, and fill in your own account

name and password.

at lower-left, and fill in your own account

name and password.

Now you can click the + button beneath the list of accounts. The little panel shown at bottom in Figure 13-2 appears.

As though this business of accounts and passwords isn’t complicated enough already, Mac OS X 10.5 offers several types of accounts. When you create an account, you’re expected to specify which type that person gets.

To do that, open the New Account pop-up menu (Figure 13-2, bottom). Its five account types are described on the following pages.

If this is your own personal Mac, just beneath your name on the Accounts pane of System Preferences, it probably says Admin. This, as you could probably guess, stands for Administrator.

Because you’re the person who originally installed Mac OS X, the Mac assumes that you are its administrator—the technical wizard in charge of it. You’re the teacher, the parent, the resident guru. You’re the one who will maintain this Mac. Only an administrator is allowed to:

Install new programs into the Applications folder.

Add fonts that everybody can use.

Figure 13-2. Top: The screen lists everyone who has an account. From here, you can create new accounts or change passwords. If you’re new at this, there’s probably just one account listed here: yours. This is the account that Mac OS X created when you first installed it. You, the all-wise administrator, have to click the

to authenticate yourself before you

can start making changes. Bottom: In the revamped Leopard

account-creation process, the first step is choosing which

type of account you want to create.

to authenticate yourself before you

can start making changes. Bottom: In the revamped Leopard

account-creation process, the first step is choosing which

type of account you want to create.Make changes to certain System Preferences panes (including Network, Date & Time, Energy Saver, and Startup Disk).

Use some features of the Disk Utility program.

Create, move, or delete folders outside of your Home folder.

Decide who gets to have accounts on the Mac.

Open, change, or delete anyone else’s files.

You’ll find certain settings all over Mac OS X that you can change only if you’re an administrator—including many in the Accounts pane itself. Administrator status also plays an enormous role when you want to network your Mac to other kinds of computers, as described in the next chapter.

As you create accounts for other people who’ll use this Mac, you’re offered the opportunity to make each one an administrator just like you. Needless to say, use discretion. Bestow these powers only upon people as responsible and technically masterful as yourself.

Most people, on most Macs, are ordinary Standard account holders (Figure 13-2). These people have everyday access to their own Home folders and to the harmless panes of System Preferences, but most other areas of the Mac are off limits. Mac OS X won’t even let them create new folders on the main hard drive, except inside their own Home folders (or in the Shared folder described in Fast User Switching).

A few of the System Preferences panels display a padlock

icon (![]() ). If you’re a Standard account holder, you

can’t make changes to these settings without the assistance of an

administrator. Fortunately, you aren’t required to log out so that

an administrator can log in and make changes. You can just call

the administrator over, click the padlock icon, and let him type

in his name and password (if, indeed, he feels comfortable with

you making the changes you’re about to make).

). If you’re a Standard account holder, you

can’t make changes to these settings without the assistance of an

administrator. Fortunately, you aren’t required to log out so that

an administrator can log in and make changes. You can just call

the administrator over, click the padlock icon, and let him type

in his name and password (if, indeed, he feels comfortable with

you making the changes you’re about to make).

A Managed account is the same thing as a Standard account—except that you’ve turned on Parental Controls. (These controls are described later in this chapter.) You can turn a Managed account into a Standard account just by turning off Parental Controls, and vice versa.

That is, this account usually has even fewer freedoms—because you’ve limited the programs that this person is allowed to use, for example. Use a Managed account for children or anyone else who needs a Mac with rubber walls.

This kind of account is extremely useful—if your Mac is on a network (Chapter 14).

See, ordinarily, you can log in and access the files on your Mac in either of two ways:

In person, seated in front of it.

From across the network.

This arrangement was designed with families and schools in mind: lots of people sharing a single Mac.

This setup got a little silly, though, when the people on a network each have their own computers. If you wanted your spouse or your sales director to be able to grab some files off of your Mac, you’d have to create full-blown accounts for them on your Mac, complete with an utterly unnecessary Home folder that they’d never use.

That’s why the Sharing Only account is such a great idea. It’s available only from across the network. You can’t get into it by sitting down at the Mac itself—it has no Home folder! Finally, of course, a Sharing Only account holder can’t make any changes to the Mac’s settings or programs.

In other words, a Sharing Only account exists solely for the purpose of file sharing on the network, and people can enter their names and passwords only from other Macs.

Once you’ve set up this kind of account, all the file-sharing and screen-sharing goodies described in Chapter 14 become available.

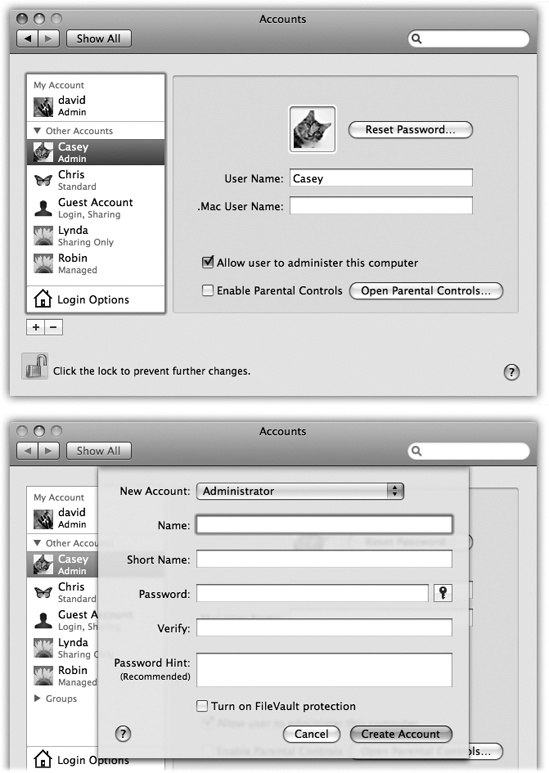

A group is just a virtual container that holds the names of other account holders. You might create one for your most trusted colleagues, another for those rambunctious kids, and so on—all in the name of streamlining the file-sharing privileges feature described in Setup: Sharing Any Folder. The box on the facing page covers groups in more detail.

Mac OS X has always offered a special account called the Guest account. It was great for accommodating visitors, buddies, or anyone else who was just passing through and wanted to use your Mac for awhile. If you let such people use the Guest account, your own account remains private and un-messed-with.

But before Mac OS X 10.5, there was a problem: Any changes your friend made—downloading mail, making Web bookmarks, putting up a raunchy desktop picture—would still be there for the next guest to enjoy, unless you painstakingly restored everything back to neutral. The Guest account was like a hotel room shared by successive guests. And you were the maid.

In Leopard, any changes your guest makes while using your Mac are automatically erased when she logs out. Files are deleted, email is nuked, setting changes are forgotten. It’s like a hotel that gets demolished and rebuilt after each guest departs.

The Guest account isn’t listed in the New Account pop-up menu (Figure 13-2). That’s because there’s only one Guest account; you can’t actually create additional ones.

So to use the Guest account, bring it to life by turning on “Allow guests to log into this computer.” You can even turn on the parental controls described earlier in this chapter by clicking Open Parental Controls, or permit the guest to exchange files with your Mac from across the network (Chapter 14) by turning on “Allow guests to connect to shared folders.”

Just remember to warn your vagabond friend that once he logs out, all traces of his visit are wiped out forever. (At least from your Mac.

All right. So you click the + button. From the New Account pop-up menu, you choose the type of account you want to create.

Now, on the same starter sheet, you fill in the most critical information about the new account holder:

Name. If it’s just the family, this could be Chris or Robin. If it’s a corporation or school, you probably want to use both first and last names.

Short Name. You’ll quickly discover the value of having a short name—an abbreviation of your actual name—particularly if your name is, say, Alexandra Stephanopoulos.

When you sign into your Mac in person, you can use either your long or short name. But when you access this Mac by dialing into it or connecting from across the network (as described in the next chapter), use the short version.

As soon as you tab into this field, the Mac proposes a short name for you. You can replace the suggestion with whatever you like. Technically, it doesn’t even have to be shorter than the “long” name, but spaces and most punctuation marks are forbidden.

Password, Verify. Here’s where you type this new account holder’s password (Figure 13-2). In fact, you’re supposed to type it twice, to make sure you didn’t introduce a typo the first time. (The Mac displays only dots as you type, to guard against the possibility that somebody is watching over your shoulder.)

The usual computer book takes this opportunity to stress the importance of a long, complex password—a phrase that isn’t in the dictionary, something made up of mixed letters and numbers. This is excellent advice if you create sensitive documents and work in a big corporation.

But if you share the Mac only with a spouse or a few trusted colleagues in a small office, you may have nothing to hide. You may see the multiple-users feature more as a convenience (keeping your settings and files separate) than a protector of secrecy and security. In these situations, there’s no particular urgency to the mission of thwarting the world’s hackers with a convoluted password.

In that case, you may want to consider setting up no password—leaving both password blanks empty. Later, whenever you’re asked for your password, just leave the Password box blank. You’ll be able to log in that much faster each day.

Password Hint. If you gave yourself a password, you can leave yourself a hint in this box. If your password is the middle name of the first person who ever kissed you, for example, your hint might be “middle name of the first person who ever kissed me.”

Later, if you forget your password, the Mac will show you this cue to jog your memory.

Turn on FileVault protection. FileVault has more on this advanced corporate-security feature. (This option isn’t available for Sharing Only accounts.)

When you finish setting up these essential items, click Create Account. If you left the password boxes empty, the Mac asks for reassurance that you know what you’re doing; click OK.

You then return to the Accounts pane, where you see the new account name in the list at the left side.

Here, three final decisions await your wisdom:

.Mac User Name. Each account holder might well have her own .Mac account (especially because Apple offers a family-pack deal on these accounts). Since the .Mac service is growing in importance and features—email address, Web site, iDisk, syncing, Back to My Mac, and so on—it’s convenient to associate each account with its own .Mac name.

Enable Parental Controls. “Parental controls” refers to the feature that limits what your offspring are allowed to do on this computer—and how much time a day that they’re allowed to spend glued to the mouse. (You can turn on parental controls only for Standard and Guest accounts, even though the checkbox appears for Admin accounts too.) Details are in Parental Controls.

Allow user to administer this computer. This checkbox lets you turn ordinary, unsuspecting Standard or Managed accounts into Administrator accounts, as described above. You know—when your kid turns 18.

The usual Mac OS X sign-in screen (Figure 13-1) displays each account holder’s name, accompanied by a little picture.

When you click the sample photo, you get a pop-up menu of Apple-supplied graphics; you can choose one to represent you. It becomes not only your icon on the sign-in screen, but also your “card” photo in Mac OS X’s Address Book program and your icon in iChat.

Figure 13-3. Once you’ve selected a photo to represent yourself (left), you can adjust its position relative to the square “frame” (right), or adjust its size by dragging the slider. Finally, when the picture looks correctly framed, click Set. (The next time you return to the Images dialog box, you can recall the new image using the Recent Pictures pop-up menu.)

If you’d rather supply your own graphics file—a digital photo of your own head, for example—then choose Edit Picture from the pop-up menu. As shown in Figure 13-3, you have several options:

Drag a graphics file directly into the “picture well” (Figure 13-3). Use the cropping slider below the picture to frame it properly.

Click Choose. You’re shown a list of what’s on your hard drive. Find and double-click the image you want.

Take a new picture. If your Mac has a built-in camera above the screen, or if you have an external webcam or a camcorder hooked up, click the little camera button. The Mac counts down from 3 with loud beeps to help you get ready, and then takes the picture.

In each case, click Set to enshrine your icon forever (or until you feel like picking a different one).

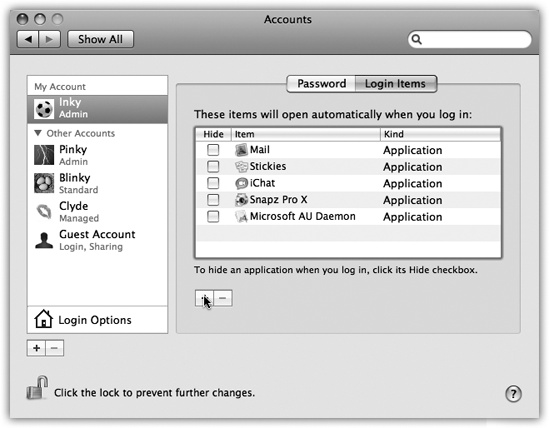

There’s one additional System Preferences setting that your account holders can set up for themselves: which programs or documents open automatically upon login. (This is one decision an administrator can’t make for other people. It’s available only to whoever is logged in at the moment.)

To choose your own crew of self-starters, open System Preferences and click the Accounts icon. Click the Login Items tab. As shown in Figure 13-4, you can now build a list of programs, documents, disks, and other goodies that automatically launch each time you log in. You can even turn on the Hide checkbox for each one, so that the program is running in the background at login time, waiting to be called into service with a quick click.

Figure 13-4. You can add any icon to the list of things you want to start up automatically. Click the + button to summon the Open dialog box where you can find the icon, select it, and then click Choose. Better yet, if you can see the icon in a folder or disk window (or on the desktop), just drag it into this list. To remove an item, click it in the list and then click the button.

Don’t feel obligated to limit this list to programs and documents, by the way. Disks, folders, servers on the network, and other fun icons can also be startup items, so that their windows are open and waiting when you arrive at the Mac each morning.

Tip

Here’s a much quicker way to add something to the Login Items list: right-click its Dock icon and choose “Open at Login” from the shortcut menu.

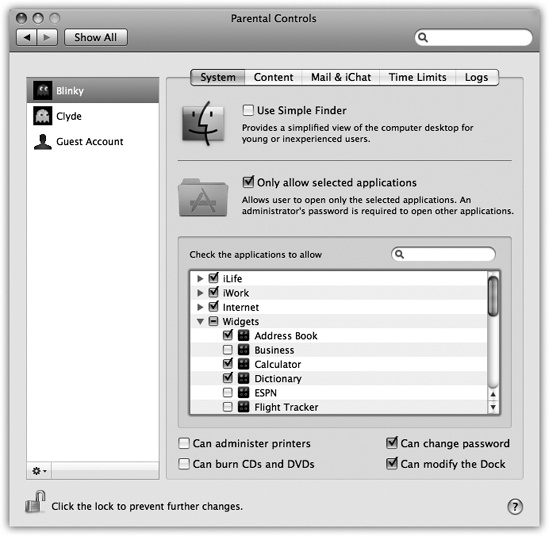

If you’re setting up a Standard or Guest account, the Parental Controls checkbox affords you the opportunity to shield your Mac—or its very young, very fearful, or very mischievous operator—from confusion and harm. This is a helpful feature to remember when you’re setting up accounts for students, young children, or easily intimidated adults.

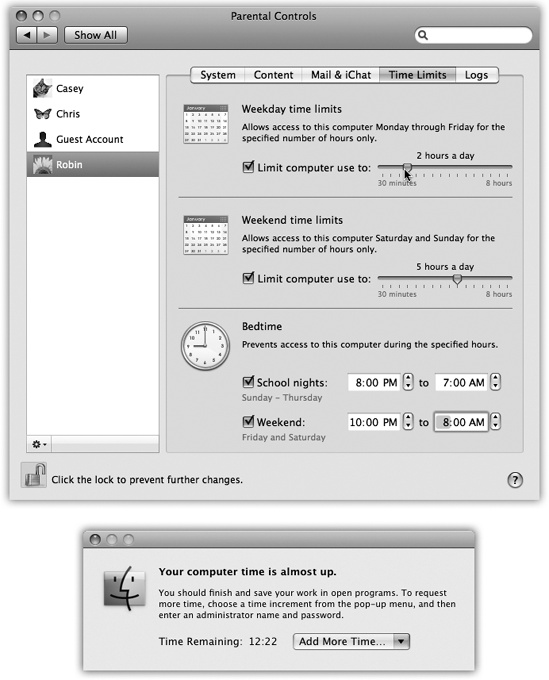

You can specify how many hours a day each person is allowed to use the Mac, and declare certain hours (like sleeping hours) off-limits. You can specify exactly who your kids are allowed to communicate with via email (if they use Mail) and instant messaging (if they use iChat), what Web sites they can visit (if they use Safari), what programs they’re allowed to use, and even what words they can look up in the Mac OS X Dictionary.

Here are all the ways you can keep your little Standard account holders shielded from the Internet—and themselves. For sanity’s sake, the following discussion refers to the Standard account holder as “your child.” But some of these controls—notably those in the System category—are equally useful for people of any age who feel overwhelmed by the Mac, are inclined to mess it up by not knowing what they’re doing, or are tempted to mess it up deliberately.

Note

If you use any of these options, the account type listed on the Accounts panel changes from “Standard” to “Managed.”

On this tab, you see the options shown in Figure 13-5. Use these options to limit what your Managed-account flock is allowed to do. You can limit them to using certain programs, for example, or prevent them from burning DVDs, changing settings, or fiddling with your printer setups.

(Limiting what people can do to your Mac when you’re not looking is a handy feature under any shared-computer circumstance. But if there’s one word tattooed on its forehead, it would be “Classrooms!”)

On the panel that pops up when you click Configure, you have two options: “Use Simple Finder” and “Only allow selected applications.”

Figure 13-5. In the Parental Controls window, you can control the capabilities of any account holder on your Mac. In the lower half of the System tab window, you can choose applications and even Dashboard widgets by turning on the boxes next to their names. (Expand the flippy triangles if necessary.) Those are the only programs these account holders will be allowed to use. (The new Search box helps you find certain programs without knowing their categories.)

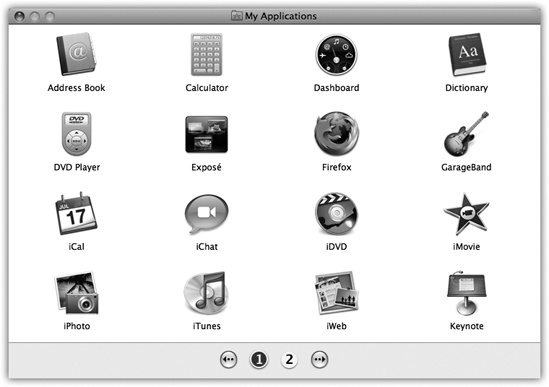

If you’re really concerned about somebody’s ability to survive the Mac—or the Mac’s ability to survive them—turn on “Use Simple Finder.” Then turn on the checkboxes of the programs that person is allowed to use.

Suppose you’re the lucky Mac fan who’s been given a Simple

Finder account. When you log in, you discover the barren world

shown in Figure 13-6.

There are only three menus (![]() , Finder, and File), a single onscreen

window, no hard drive icon, and a bare-bones Dock. The only

folders you can see are in the Dock. They include:

, Finder, and File), a single onscreen

window, no hard drive icon, and a bare-bones Dock. The only

folders you can see are in the Dock. They include:

My Applications. These are aliases of the applications that the administrator approved. They appear on a strange, fixed, icon view, called “pages.” List and column views don’t exist. The Simple person can’t move, rename, delete, sort, or change the display of these icons—merely click them. If you have too many to fit on one screen, you get numbered page buttons beneath them, which you click to move from one set to another.

Documents. Behind the scenes, this is your Home→Documents folder. Of course, as a Simple Finder kind of soul, you don’t have a visible Home folder. All your stuff goes in here.

Figure 13-6. The Simple Finder doesn’t feel like home—unless you’ve got one of those Spartan, space-age, Dr. Evil-style pads. But it can be just the ticket for less-skilled Mac users, with few options and a basic one-click interface. Every program in the My Applications folder is actually an alias to the real program, which is safely ensconced in the off-limits Applications folder.

Shared. This is the same Shared folder described in Fast User Switching. It’s provided so that you and other account holders can exchange documents. However, you can’t open any of the folders here, only the documents.

Trash. The Trash is here, but you won’t use it much. Selecting or dragging any icon is against the rules, so you’re left with no obvious means of putting anything into your Trash.

The only programs with their own icons in the Dock are Finder and Dashboard.

Otherwise, you can essentially forget everything else you’ve read in this book. You can’t create folders, move icons, or do much of anything beyond clicking the icons that your benevolent administrator has provided. It’s as though Mac OS X moved away and left you the empty house.

To keep things extra-simple, Mac OS X permits only one window at a time to be open. It’s easy to open icons, too, because one click opens it, not two.

The File menu is stunted, offering only a Close Window command. The Finder menu only gives you two options: About Finder and Run Full Finder. (The latter command prompts you for an administrator’s user name and password, and then turns back into the regular Finder—a handy escape hatch. To return to Simple Finder, just choose Finder→Return to Simple Finder.)

The

menu is really

bare-bones: You can Log Out, Force Quit, or go to Sleep.

That’s it.

menu is really

bare-bones: You can Log Out, Force Quit, or go to Sleep.

That’s it.There’s no trace of Spotlight.

Although the Simple Finder is simple, any program (at least, any that the administrator has permitted) can run from Simple Finder. A program running inside the Simple Finder still has all of its features and complexities—only the Finder has been whittled down to its essence.

In other words, Simple Finder is great for streamlining the Finder, but novices won’t get far combating their techno-fear until the world presents us with Simple Keynote, Simple Mail, and Simple Microsoft Word. Still, it’s better than nothing.

By tinkering with the checkboxes here, you can declare certain programs off-limits to this account holder, or turn off his ability to remove Dock icons, burn CDs, and so on.

You can restrict this person’s access to the Mac in several different ways:

Limit the programs. At the bottom of the dialog box shown in Figure 13-5, you see a list of all the programs in your Applications folder (an interesting read in its own right). Only checked items show up in the account holder’s Applications folder.

Tip

If you don’t see a program listed, use the Search box, or drag its icon from the Finder into the window.

If, for instance, you’re setting up an account for use in the classroom, you may want to turn off access to programs like Disk Utility, iChat, and Tomb Raider.

Limit the features. When you first create them, Standard account holders are free to burn CDs or DVDs, modify what’s on the Dock, change their passwords, and view the settings of all System Preferences panels (although they can’t change all of these settings).

Depending on your situation, you may find it useful to turn off some of these options. In a school lab, for example, you might want to turn off the ability to burn discs (to block software piracy). If you’re setting up a Mac for a technophobe, you might want to turn off the ability to change the Dock (so your colleague won’t accidentally lose access to his own programs and work).

“Content,” in this case, means “two options we really didn’t have any other place to put.” Actually, what it really means is Dictionary and Safari.

Mac OS X comes with a complete electronic copy of the New Oxford American Dictionary. And “complete,” in this case, means “it even has swear words.”

Turning on “Hide profanity in Dictionary” is like having an Insta-Censor”. It hides most of the naughty words from the dictionary whenever your young account holder is logged in (Figure 13-7).

This feature is designed to limit which Web sites your kid is allowed to visit.

Frankly, trying to block the racy stuff from the Web is something of a hopeless task; if your kid doesn’t manage to get round this blockade by simply using a different browser, he’ll just wind up seeing the dirty pictures at another kid’s house. But at least you can enjoy the illusion of taking a stand, using approaches of three degrees of severity:

Allow unrestricted access to Web sites. In other words, no filtering. Anything goes.

Try to limit access to adult Web sites automatically. Those words—“try to”—are Apple’s way of admitting that no filter is foolproof.

In any case, Mac OS X comes with a built-in database of Web sites that it already knows may be inappropriate for children—and these sites won’t appear in Safari while this account holder is logged in. By clicking Customize and then editing the “Always allow” and “Never allow” lists, you can override its decisions on a site-at-a-time basis.

Allow access to only these Web sites. This is the most restrictive approach of all: It’s a whitelist, a list of the only Web sites your youngster is allowed to visit. It’s filled with kid-friendly sites like Disney and Discovery Kids, but of course you can edit the list by clicking the + and − buttons below the list.

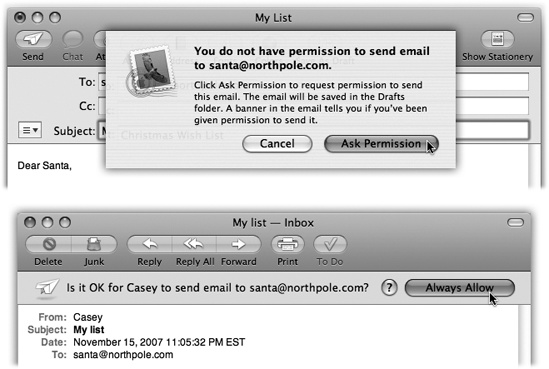

Here, you can build a list of email and chat addresses, corresponding to the people you feel comfortable letting your kid exchange emails and chat with. Click the + button below the list, type the address, press Enter, lather, rinse, and repeat.

For reasons explained in a moment, turn on “Send permission emails to,” and plug in your own email address.

Now then: When your youngster uses Apple’s Mail program to send a message to someone who’s not on the approved list, or tries to iChat with someone not on the list, he gets the message shown at top in Figure 13-8. If he clicks Ask Permission, then your copy of Mail shortly receives a permission-request message (Figure 13-8, bottom); meanwhile, the outgoing message gets placed in limbo in his Drafts folder.

Figure 13-8. Top: If your kid tries to contact someone who’s not on the Approved list, he can either give up or click Ask Permission. Bottom: In the latter case, you’ll know about it. If you’re convinced that the would-be correspondent is not, in fact, a stalker, you can grant permission by clicking Always Allow. Your young ward gets the good news the next time he visits his Drafts folder, where the message has been awaiting word from you, the Good Parent.

If you add that person’s address to the list of approved correspondents, then the next time your young apprentice clicks the quarantined outgoing message in his Drafts folder, the banner across the top lets him know that all is well—and the message is OK to go out.

Note

This feature doesn’t attempt to stop email or chat using other programs, like Microsoft Entourage or Skype. If you’re worried about your efforts being bypassed, block access to those programs using the Forbidden Applications list described above.

When your underling fires up iChat or Mail, she’ll discover that her Buddy List is empty except for the people you’ve identified.

Handling the teenage hissy fit is your problem.

Clever folks, those Apple programmers. They must have kids of their own.

Figure 13-9. Top: If this account holder tries to log in outside of the time limits you specify here, she’ll encounter only a box that says, “Computer time limits expired.” She’ll be offered a pop-up menu that grants her additional time, from 15 minutes to “Rest of the day”—but it requires your parental consent (actually, your parental password) to activate. Bottom: Similarly, if she’s using the Mac as her time winds down, she gets this message. Once again, you, the all-knowing administrator, can grant her more time using this dialog box.

They realize that some parents care about how much time their kids spending front of the Mac, and some also care about which hours (Figure 13-9):

How much time. In the “Weekday time limits” section, turn on “Limit computer use to,” and then adjust the slider. A similar slider appears for Weekend time limits.

Which hours. In the “Bedtime” section, turn on the checkbox for either “School nights” or “Weekend,” and then set the hours of the day (or, rather, night) when the Mac is unavailable to your young account holders.

In other words, this feature may have the smallest pages-to-significance ratio in this entire book. Doesn’t take long to explain it, but it could bring the parents of Mac addicts a lot of peace.

The final tab of the Parental Controls panel is Big Brother Central. Here’s a complete rundown of what your kids have been up to. Its four categories—Websites visited, Websites blocked, Applications, and iChat—are extremely detailed. For example, in Applications, you can see exactly which programs your kids tried to use when, and how much time they spent in each one. Figure 13-10 shows the idea.

Figure 13-10. These logs track everything your kid tried to do; it’s spying, sure, but it’s for the good of the child. (Right?) Use the pop-up menus at the top to change the time period being reported (Today, This Week, or whatever) and how they’re grouped in the list—by date or by application/Web site.

If you see something that you really think should be off limits—a site in the Websites Visited list, an application, an iChat session with someone—click its name and then click Restrict. You’ve just nipped that one in the bud.

Conversely, if the Mac blocked a Web site that you think is really OK, click its name in the list, and then click Allow. (And if you’re wondering what a certain Web page is, click it and then click Open.)

If you’re an administrator, you can change your own account in any way you like.

If you have any other kind of account, though, you can’t change anything but your picture and password. If you want to make any other changes, you have to ask an admin to log in, make the changes you want made to your account, and then turn the computer back over to you.

Hey, it happens: Somebody graduates, somebody gets fired, somebody dumps you. Sooner or later, you may need to delete an account from your Mac.

When that time comes, click the account name in the Accounts list and then click the minus-sign button beneath the list. Mac OS X asks what to do with all of the dearly departed’s files and settings:

Save the home folder in a disk image. This option presents the “I’ll be back” approach. Mac OS X preserves the dearly departed’s folders on the Mac, in a tidy digital envelope that won’t clutter your hard drive, and can be reopened in case of emergency.

In the Users→Deleted Users folder, you find a disk image file (.dmg). If you double-click it, a new, virtual disk icon named for the deleted account appears on your desktop. You can open folders and root through the stuff in this “disk,” just as if it were a living, working Home folder.

If fate ever brings that person back into your life, you can use this disk image to reinstate the deleted person’s account. Start by creating a brand-new account. Then copy the contents of the folders in the mounted disk image (Documents, Pictures, Desktop, and so on) into the corresponding folders of the new Home folder.

Do not change the home folder. This time, Mac OS X removes the account, in that it no longer appears in the Login list or in the Accounts panel of System Preferences—but it leaves the Home folder right where it is. Use this option if you don’t intend to dispose of the dearly departed’s belongings right here and now.

Delete the home folder. This button offers the “Hasta la vista, baby” approach. The account and all of its files and settings are vaporized forever, on the spot.

Note

If you delete a Shared Only account, you’re not offered the chance to preserve the Home folder contents—because a Shared Only account doesn’t have a Home folder.

Once you’ve set up more than one account, the dialog box shown

in Figure 13-1 appears

whenever you turn on the Mac, whenever you choose ![]() →Log Out, or whenever the Mac logs you out

automatically. But a few extra controls let you, an administrator, set

up either more or less security at the login screen—or, put another

way, build in less or more convenience.

→Log Out, or whenever the Mac logs you out

automatically. But a few extra controls let you, an administrator, set

up either more or less security at the login screen—or, put another

way, build in less or more convenience.

Open System Preferences, click Accounts, and then click the Login Options button (Figure 13-11). Here are some of the ways you can shape the login experience for greater security (or greater convenience):

Automatic login. This option eliminates the need to sign in at all. It’s a timesaving, hassle-free arrangement if only one person uses the Mac, or if one person uses it most of the time.

When you choose an account holder’s name from this pop-up menu, you’re prompted for his name and password. Type it and click OK.

From now on, the dialog box shown in Figure 13-1 won’t appear at all at startup time. After turning on the machine, you, the specified account holder, zoom straight to your desktop.

Figure 13-11. These options make it easier or harder for people to sign in, offering various degrees of security. By the way: Turning on “Name and password” also lets you sign in as >console, a troubleshooting technique for people who are comfortable typing Unix commands.

Of course, only one lucky person can enjoy this express ticket. Everybody else must still enter their names and passwords. (And how can they, since the Mac rushes right into the Automatic person’s account at startup time? Answer: The Automatic thing happens only at startup time. The usual login screen appears whenever the current account holder logs out—by choosing

→Log Out, for example.)

→Log Out, for example.)Display login window as. Under normal circumstances, the login screen presents a list of account holders when you power up the Mac, as shown in Figure 13-1. That’s the “List of users” option in action.

If you’re especially worried about security, however, you might not even want that list to appear. If you turn on “Name and password,” each person who signs in must type both his name (into a blank that appears) and his password—a very inconvenient, but more secure, arrangement.

Show the Restart, Sleep, and Shut Down buttons. Truth is, the Mac OS X security system is easy to circumvent. Truly devoted evildoers can bypass the standard login screen in a number of different ways: restart in FireWire disk mode, restart at the Unix Terminal, and so on. Suddenly, these no-goodniks have full access to every document on the machine, blowing right past all of the safeguards you’ve so carefully established.

One way to thwart them is to turn off this checkbox. Now there’s no Restart or Shut Down button to tempt mischief-makers. That’s plenty of protection in most homes, schools, and workplaces; after all, Mac people tend to be nice people. (Another approach: use FileVault, which is descibed in FileVault.)

Show Input menu in login window. If the Input menu (Exposé & Spaces) is available at login time, it means that people who use non-U.S. keyboard layouts and alphabets can use the login features without having to pretend to be American. (It also means that you have a much wider universe of difficult-to-guess passwords, since your password can be in, for example, Japanese characters. Greetings, Mr. Bond-san.)

Show password hints. As described earlier, Mac OS X is kind enough to display your password hint (“middle name of the first person who ever kissed me”) after you’ve typed it wrong three times when trying to log in. This option lets you turn off that feature for an extra layer of security. The hint will never appear.

Use VoiceOver at login window. The VoiceOver feature (VoiceOver) is all well and good if you’re blind. But how are you supposed to log in? Turn on this checkbox, and VoiceOver speaks the features on the Login panel, too.

Enable fast user switching. This feature lets you switch to another account without having to log out of the first one, as described in Fast User Switching.

View as. If you do, in fact, turn on Fast User Switching, a new menu appears at the upper-right corner of your screen, listing all the account holders on the machine. Thanks to this pop-up menu, you can now specify what that menu looks like. It can display the current account holder’s full name (Name), the short name (Short Name), or only a generic torso-silhouette icon (Icon) to save space on the menu bar.

Once somebody has set up your account, here’s what it’s like getting into, and out of, a Mac OS X machine. (For the purposes of this discussion, “you” are no longer the administrator—you’re one of the students, employees, or family members for whom an account has been set up.)

When you first turn on the Mac—or when the person who last

used this computer chooses ![]() →Log Out—the login screen shown in Figure 13-1 appears. At this

point, you can proceed in any of several ways:

→Log Out—the login screen shown in Figure 13-1 appears. At this

point, you can proceed in any of several ways:

Restart. Click if you need to restart the Mac for some reason. (The Restart and Shut Down buttons don’t appear here if the administrator has chosen to hide them as a security precaution.)

Shut Down. Click if you’re done for the day, or if sudden panic about the complexity of user accounts makes you want to run away. The computer turns off.

Log In. To sign in, click your account name in the list. If you’re a keyboard speed freak, you can also type the first letter or two—or press the up or down arrow keys—until your name is highlighted. Then press Return or Enter.

Either way, the password box appears now (if a password is required). If you accidentally click the wrong person’s name on the first screen, you can click Back. Otherwise, type your password, and then press Enter (or click Log In).

You can try as many times as you want to type the password. With each incorrect guess, the entire dialog box shudders violently from side to side, as though shaking its head “No.” If you try unsuccessfully three times, your hint appears—if you’ve set one up. (If you see a strange

icon in the password box, guess what?

You’ve got your Caps Lock key on, and the Mac thinks you’re

typing an all-capitals password.)

icon in the password box, guess what?

You’ve got your Caps Lock key on, and the Mac thinks you’re

typing an all-capitals password.)

Once you’re in, the world of the Mac looks just the way you left it (or the way an administrator set it up for you).

When you’re finished using the Mac, choose ![]() →Log Out (or press Shift-

→Log Out (or press Shift-![]() -Q). A confirmation message appears; if you

click Cancel or press Esc, you return to whatever you were doing. If

you click Log Out, or press Return, you return to the screen shown

in Figure Figure 13-1,

and the entire sign-in cycle begins again.

-Q). A confirmation message appears; if you

click Cancel or press Esc, you return to whatever you were doing. If

you click Log Out, or press Return, you return to the screen shown

in Figure Figure 13-1,

and the entire sign-in cycle begins again.

It’s all fine to say that every account is segregated from all other accounts. It’s nice to know that your stuff is safe from the prying eyes of your co-workers or family.

But what about collaboration? What if you want to give some files or folders to another account holder?

You can’t just open up someone else’s Home folder and drop it in

there. Yes, every account holder has a Home folder (all in the Users

folder on your hard drive). But if you try to open anybody else’s Home

folder, you’ll see a tiny red ![]() icon superimposed on almost every folder

inside, telling you “Look, but don’t touch.”

icon superimposed on almost every folder

inside, telling you “Look, but don’t touch.”

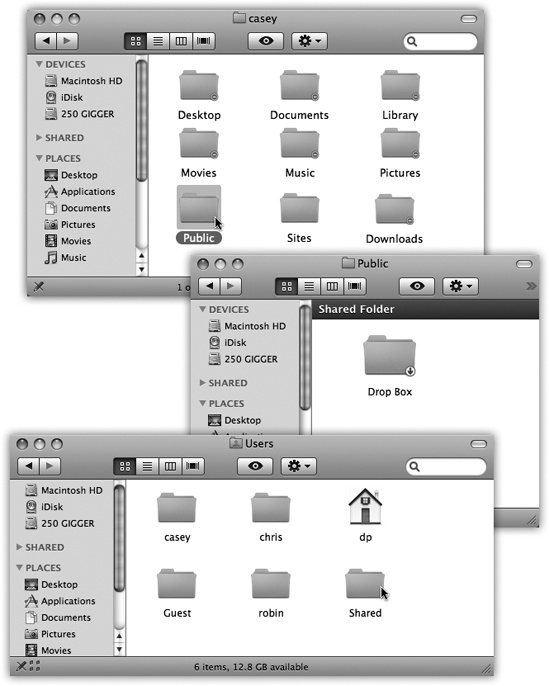

Fortunately, there are a couple of wormholes between accounts (Figure 13-12):

Figure 13-12. Top: In other people’s Home folders, the Public and Sites

folders are available for your inspection. These two folders contain

stuff that other people have “published” for the benefit of their

co-workers. Middle: In the Public folder is the Drop Box, which

serves the opposite purpose. It lets anyone else who uses this Mac

hand in files to you; they, however, can’t see what’s in it. Bottom:

Inside the Users folder (to get there from a Home folder, press

![]() -up arrow) is the Shared folder, a wormhole

connecting all accounts. Everybody has full access to everything

inside.

-up arrow) is the Shared folder, a wormhole

connecting all accounts. Everybody has full access to everything

inside.

The Shared folder. Sitting in the Users folder is one folder that doesn’t correspond to any particular person: Shared. Everybody can freely access this folder, inserting and extracting files without restriction. It’s the common ground among all the account holders on a single Mac. It’s Central Park, the farmer’s market, and the grocery-store bulletin board.

The Public folder. In your Home folder, there’s a folder called Public. Anything you copy into it becomes available for inspection or copying (but not changing or deleting) by any other account holder, whether they log into your Mac or sign in from across the network.

The Drop Box. And inside your Public folder is another cool little folder: the Drop Box. It exists to let other people give files to you, discreetly and invisibly to anyone else. That is, people can drop files and folders into your Drop Box, but they can’t actually open it. This folder, too, is available both locally (in person) and from across the network.

The account system described so far in this chapter has its charms. It keeps everyone’s stuff separate, it keeps your files safe, and it lets you have the desktop picture of your choice.

Unfortunately, it can go from handy to hassle in one split second. That’s when you’re logged in, and somebody else wants to duck in just for a second—to check email or a calendar, for example. What are you supposed to do—log out completely, closing all your documents and quitting all your programs, just so the interloper can look something up? Then afterward, you’d have to log back in and fire up all your stuff again, praying that your inspirational muse hasn’t fled in the meantime.

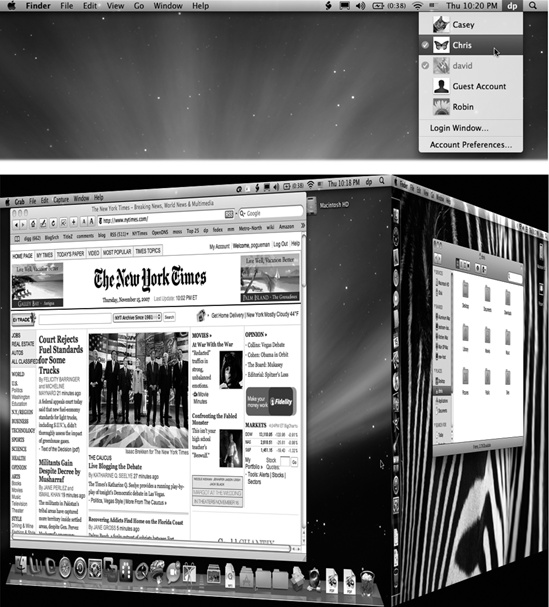

Fortunately, that’s all over now. Fast User Switching—which works just as it does in Windows—lets Person B log in and use the Mac for a little while. All of your stuff, Person A, simply slides into the background, still open the way you had it; see Figure 13-13.

When Person B is finished working, you can bring your whole work environment back to the screen without having to reopen anything. All your windows and programs are still open, just as you left them.

To turn on this feature, open the Accounts panel of System

Preferences (and click the ![]() , if necessary, to unlock the panel). Click

Login Options, and turn on “Enable fast user switching.” (You can see

this dialog box in Figure 13-11.)

, if necessary, to unlock the panel). Click

Login Options, and turn on “Enable fast user switching.” (You can see

this dialog box in Figure 13-11.)

The only change you notice immediately is the appearance of your own account name in the upper-right corner of the screen (Figure 13-13, top). You can change what this menu looks like by using the “View as” pop-up menu, also shown in Figure 13-11.

That’s all there is to it. Next time you need a fellow account holder to relinquish control so that you can duck in to do a little work, just choose your name from the Accounts menu. Type your password, if one is required, and feel guiltless about the interruption.

Figure 13-13. Top: The appearance of the Accounts menu lets you know that Fast User Switching is turned on. The circled checkmark indicates people who are already logged in, including those who have been “fast user switched” into the background. The dimmed name shows who’s logged in right now. Bottom: When the screen changes from your account to somebody else’s, your entire world slides visibly offscreen as though it’s mounted on the side of a rotating cube—a spectacular animation made possible by Mac OS X’s Quartz Extreme graphics software.

Mac OS X has a spectacular reputation for stability and security. At this writing, not a single Mac OS X virus has emerged—a spectacular feature that may even have played a part in your decision to go Macward. There’s no Windows-esque plague of spyware, either (downloaded programs that do something sneaky behind your back). In fact, there isn’t any Mac spyware.

The usual rap is, “Well, that’s because Windows is a much bigger target. What virus writer is going to waste his time on a computer with eight percent market share?”

That may be part of the reason Mac OS X is virus-free. But Mac OS X has also been built more intelligently from the ground up. Listed below are a few of the many drafty corners of a typical operating system that Apple has solidly plugged:

The original Windows XP came with five of its ports open. Mac OS X has always come from the factory with all of them shut and locked.

Ports are channels that remote computers use to connect to services on your computer: one for instant messaging, one for Windows XP’s remote-control feature, and so on. It’s fine to have them open if you’re expecting visitors. But if you’ve got an open port that exposes the soft underbelly of your computer without your knowledge, you’re in for a world of hurt. Open ports are precisely what permitted viruses like Blaster to infiltrate millions of PCs. Microsoft didn’t close those ports until the Windows XP Service Pack 2.

Whenever a program tried to install itself in the original Windows XP, the operating system went ahead and installed it, potentially without your awareness.

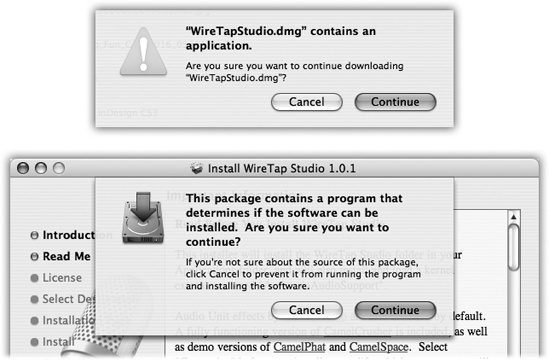

In Mac OS X, that never happens. You’re notified at every juncture when anything is trying to install itself on your Mac. In fact, you’re even notified when you’re opening a disk image or .zip file that could contain an installable program (Figure 13-14).

Unlike certain other operating systems, Mac OS X doesn’t even let an administrator touch the files that drive the operating system itself without pestering you to provide your password and grant it permission to do so. A Mac OS X virus (if there were such a thing) could theoretically wipe out all of your files, but wouldn’t be able to access anyone else’s stuff—and couldn’t touch the operating system itself.

Figure 13-14. Mac OS X hovers like a stage mother, always informing you when you’re at a point where something virusy could be happening. It warns you when you download a compressed file that could contain a runnable program (top), and even when an installer has to run a tiny sub-program before the installation (bottom).

You may already know about the Finder’s Secure Empty Trash option (Rescuing Files and Folders from the Trash). But an option on the Erase tab of the Disk Utility program can do the same super-erasing of all free space on your hard drive. We’re talking not just erasing, but recording gibberish over the spots where your files once were—once, seven times, or thirty-five times—utterly shattering any hope any hard-disk recovery firm (or spy) might have had of recovering passwords or files from your hard drive.

Safari’s Private Browsing mode means that you can freely visit Web sites without leaving any digital tracks—no history, no Downloads list, nothing (Tabbed Browsing).

Every time you try to download something, either in Safari or Mail, that contains executable code (a program, in other words), a dialog box warns you that it could conceivably harbor a virus—even if your download is compressed as a .zip or .sit file.

Those are only a few tiny examples. Here are a few of Mac OS X’s big-ticket defenses.

If you have a broadband, always-on connection, you’re open to the Internet 24 hours a day. It’s theoretically possible for some cretin to use automated hacking software to flood you with files or take control of your machine. Mac OS X’s firewall feature puts up a barrier to such mischief.

Fortunately, it’s not a complete barrier. One of the great joys of having a computer is its ability to connect to other computers. Living in a cement crypt is one way to avoid getting infected, but it’s not much fun.

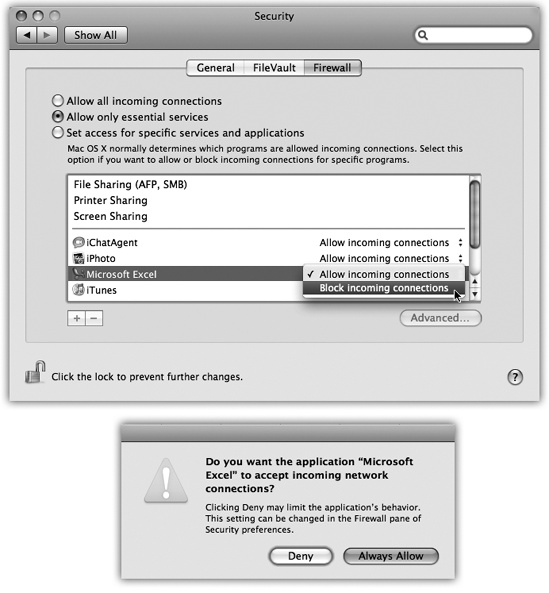

So if you open the Security panel of System Preferences, and click the Firewall tab, you see something like Figure 13-15 at top. It offers three settings:

“Allow all incoming connections” is the same as having no firewall at all. Now, most of the Internet’s cretins are far more interested in tapping into Windows machines than Macs, but you never know. Best to avoid this one.

“Allow only essential services” is the closest thing Leopard has to “block every thing.” It gives access only to a small, fixed set of deep-seated services that Mac OS X needs to get by.

Figure 13-15. Top: Apple’s new firewall in Mac OS X 10.5 looks like this. It lists the programs that have been given permission to receive communications from the Internet. At any point, you can change a program’s Block/Allow setting, as shown here. Bottom: From time to time, some program will ask for permission to communicate with its mother ship. If it’s a program you trust, click Always Allow. You can also click the + button to navigate your Applications folder and manually choose programs for inclusion. For more power and flexibility, install a shareware program like Firewalk or Brickhouse (available from www.missingmanuals.com, for example).

“Set access for specific services and applications” is the best choice for most people. It blocks all incoming pings except those addressed to programs and features that you’ve approved.

And how do they get approved? Above the horizontal line (Figure 13-15, top), features of Mac OS X itself are listed. They get added to this list automatically when you turn them on in System Preference: File Sharing, Printer Sharing, and so on.

Non-Apple programs can request passage through your firewall, too (Figure 13-15, bottom); if you click Always Allow, they appear below the line in this list.

Now, there are a few footnotes regarding the firewall:

If you’re using Mac OS X’s Internet connection sharing feature (Internet Sharing), then it’s important to turn on the firewall only for the first Mac—the one that’s the gateway to the Internet. Leave the firewall turned off on all the Macs “downstream” from it. You want to protect your Macs from the nasties of the Internet; you don’t need them giving each other the cold shoulder.

Similarly, if you’ve bought a router to distribute your Internet connection to multiple computers, it probably has its own firewall circuitry built in. In that case, turn off Mac OS X’s own firewall.

Two useful features are hiding behind the Advanced button (which is visible in Figure 13-15):

- Enable Stealth Mode

is designed to slam shut the Mac’s back door to the Internet. See, hackers often use automated hacker tools that send out “Are you there?” messages. They’re hoping to find computers that are turned on and connected full-time to the Internet. If your machine responds, and they can figure out how to get into it, they’ll use it, without your knowledge, as a relay station for pumping out spam or masking their hacking footsteps.

Enable Stealth Mode, then, makes your Mac even more invisible on the network; it means that your Mac won’t respond to the electronic signal called a ping. (On the other hand, you won’t be able to ping your machine, either, when you’re on the road and want to know if it’s turned on and online.)

- Enable Firewall Logging

creates a little text file where Mac OS X records every attempt that anyone from the outside makes to infiltrate your Mac. (To view the log, click the Open Log button. The file opens in Console for your inspection.)

The Security pane of System Preferences is one of Leopard’s most powerful security features. Understanding what it does, however, may take a little slogging.

As you know, the Mac OS X accounts system is designed to keep people out of each other’s stuff. Ordinarily, for example, Chris isn’t allowed to go rooting through Robin’s stuff.

Until FileVault came along, though, there were several ways to circumvent this protection system. A sneak or a showoff could, for example, remove your hard drive and hook it up to a Linux machine or another Mac. He’d then be able to run rampant through everybody’s files, changing or trashing them with abandon. For people with sensitive or private files, the result was a security hole bigger than Steve Jobs’ bank account.

FileVault is an extra line of defense. When you turn on this feature, your Mac automatically encrypts (scrambles) everything in your Home folder, using something called AES-128 encryption. (How secure is that? It would take a password-guessing computer 149 trillion years before hitting paydirt. Or, in more human terms, slightly longer than two back-to-back Kevin Costner movies.)

This means that unless someone knows (or can figure out) your password, FileVault renders your files unreadable for anyone but you and your computer’s administrator—no matter what sneaky tricks they try to pull.

You won’t notice much difference when FileVault is turned on. You log in as usual, clicking your name and typing your password. Only a slight pause as you log out indicates that Mac OS X is doing some housekeeping on the encrypted files: freeing up some space and/or backing up your home directory with Time Machine.

Tip

This feature is especially useful for laptop owners. If someone swipes or “borrows” your laptop, they can’t get into your stuff without the password.

Here are some things you should know about FileVault’s protection:

It’s useful only if you’ve logged out. Once you’re logged in, your files are accessible. If you want the protection, log out before you wander away from the Mac. (Or let the screen saver close your account for you; in Logout Options.)

It covers only your Home folder. Anything in your Applications, System, or Library folders is exempt from protection.

An administrator can access your files, too. According to Mac OS X’s caste system, anyone with an administrator’s account can theoretically have unhindered access to his peasants’ files—even with FileVault on—if that administrator has the master password described below.

It keeps other people from opening your files, not from deleting them. It’s still possible for someone to trash all your files, without ever seeing what they are. There’s not much you can do about this with FileVault on or off—all a malicious person needs to do is start deleting the encrypted files, and your data is gone. (FileVault works by encrypting your Home folder into eight-megabyte chunks.)

Shared folders in your Home folder will no longer be available on the network. That is, any folders you’ve shared won’t be available to your co-workers except when you’re at your Mac and logged in.

Backup programs may throw a tizzy. FileVault’s job is to “zip” and “unzip” your Home folder as you log in and out. Backup programs that work by backing up files and folders that have changed since the last backup may therefore get very confused.

Even Time Machine (Time Machine) doesn’t always play well with FileVault. For one thing, it can copy the encrypted Home folder only when it’s closed—that is, when you’re logged off. So you don’t get the continuous hourly backups that everyone else gets.

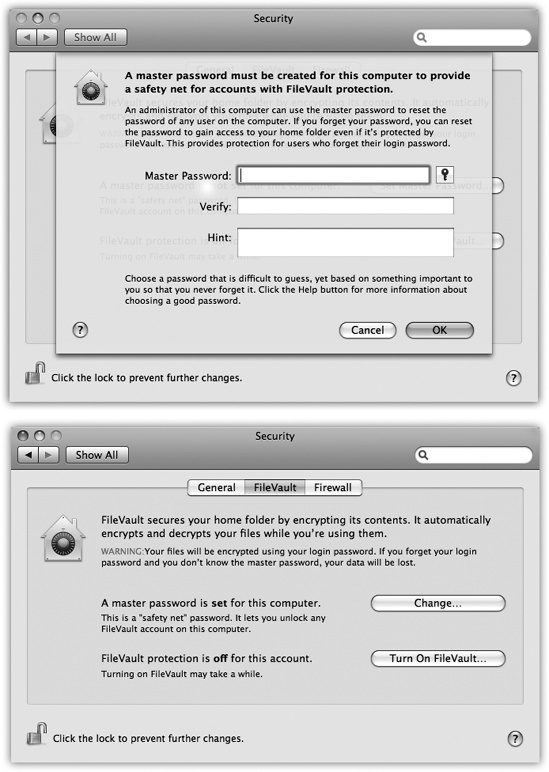

Figure 13-16. Top: To turn on FileVault for an account, you must start by making up a master password: a skeleton key that can get you into somebody’s account even if they forget their password. (You have no idea how often this happens.) Type in your master password twice, and give yourself a hint Bottom: When you click OK, you see that the Security dialog box now says, “A master password is set for this computer.” In the event of an emergency, you’ll get the hint when you click an account name at the Login screen, and then click Reset Password. Now you can click Turn On FileVault to begin the encryption process.

Second, in times of tragedy, Time Machine can restore only your entire Home folder; you can’t recover individual documents or folders in it.

If you forget your password and your administrator forgets the master password, you’re toast. If this happens, your data is permanently lost. You’ll have no choice but to erase your hard drive and start from scratch.

To turn FileVault on, proceed like this:

In System Preferences, click Security, and then click FileVault. Click Set Master Password.

If you’re the first person to try to turn on FileVault, you need to create a master password first. The master password is an override password that gives an administrator full power to access any account, even without knowing the account holder’s password, or to turn off FileVault for any account.

The thinking goes like this: Yeah, yeah, the peons with Standard accounts forget their account passwords all the time. But with FileVault, a forgotten password would mean the entire Home folder is locked forever—so Apple gave you, the technically savvy administrator, a back door. (And you, the omniscient administrator, would never forget the master password—right?)

When you click Set Master Password, the dialog box shown at top in Figure 13-16 appears.

Click “Turn On FileVault.”

You’re asked to type your account password. A dialog box appears offering some additional security options.

Note

You can also turn on FileVault for an account at the moment you create it in System Preferences→Accounts.

Click “Turn On FileVault” again.

Now Mac OS X logs you out of your own account. (It can’t encrypt a folder that’s in use.) Some time passes while it converts your Home folder into a protected state, during which you can’t do anything but wait.

After a few minutes, you arrive at the standard login window, where you can sign in as usual, confident that your stuff is securely locked away from anyone who tries to get at it when you’re not logged in.

Note

To turn off FileVault, open System Preferences, click Security, and then click Turn Off FileVault. Enter your password and click OK. (The master password sticks around once you’ve created it, however, in case you ever want to turn FileVault on again.)

As you read earlier in this chapter, the usual procedure for

finishing up a work session is for each person to choose

![]() →Log Out. After you confirm your intention to

log out, the Login screen appears, ready for the next

victim.

→Log Out. After you confirm your intention to

log out, the Login screen appears, ready for the next

victim.

But sometimes people forget. You might wander off to the bathroom for a minute, but run into a colleague there who breathlessly begins describing last night’s date and proposes finishing the conversation over pizza. The next thing you know, you’ve left your Mac unattended but logged in, with all your life’s secrets accessible to anyone who walks by your desk.

You can prevent that situation using either of two checkboxes, both in the Security panel of System Preferences:

Require password to wake this computer from sleep or screen saver. This option gives you a password-protected screen saver that locks your Mac after a few minutes of inactivity. Now, whenever somebody tries to wake up your Mac after the screen saver has appeared (or when the Mac has simply gone to sleep according to your settings in the Energy Saver panel of System Preferences), the “Enter your password” dialog box appears. No password? No access.

Log out after __ minutes of inactivity. If you prefer, you can make the Mac sign out of your account completely if it figures out that you’ve wandered off (and it’s been, say, 15 minutes since the last time you touched the mouse or keyboard). Instead, it presents the standard Login screen.

Note

Beware! If there are open, unsaved documents at the moment of truth, the Mac can’t log you out.

The information explosion of the computer age may translate into bargains, power, and efficiency, but as noted above, it carries with it a colossal annoyance: the proliferation of passwords we have to memorize. Shared folders on the network, Web sites, your iDisk, FTP sites—each requires another password.

Apple has done the world a mighty favor with its Keychain feature. The concept is brilliant. Whenever you log into Mac OS X and type in your password, you’ve typed the master code that tells the computer, “It’s really me. I’m at my computer now.” From that moment on, the Mac automatically fills in every password blank you encounter, whether it’s a Web site in Safari or Opera, a shared disk on your network, a wireless network, an encrypted disk image, or an FTP program like Transmit or RBrowser. With only a few exceptions, you can safely forget all of your passwords except your login password.

These days, all kinds of programs and services know about the Keychain and offer to store your passwords there. For example:

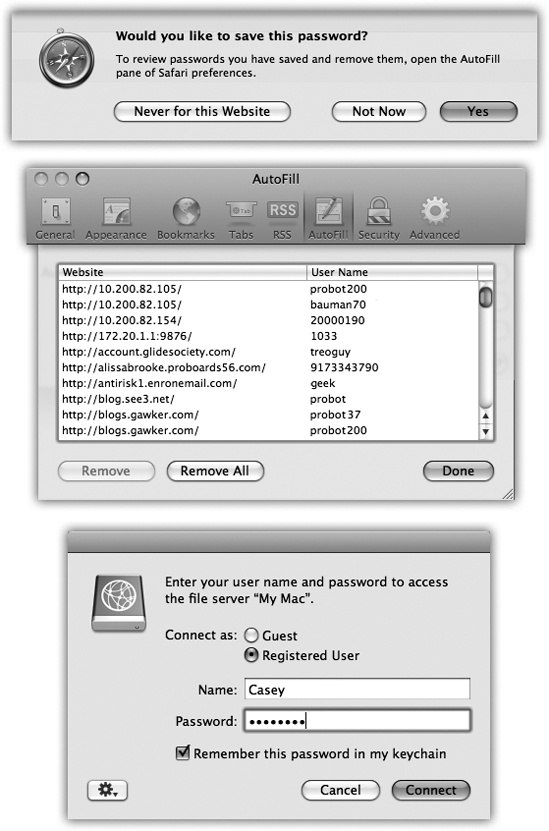

In Safari, whenever you type your name and password for a certain Web page and then click OK, a dialog box asks: “Would you like to save this password?” (See Figure 13-17, top.)

Note

This offer is valid only if, in Safari→Preferences, you’ve clicked the AutoFill tab and turned on “User names and passwords.” If not, the “Would you?” message never appears.

Note, too, that some Web sites use a nonstandard login system that also doesn’t produce the “Would you?” message. Unless the Web site provides its own “Remember me” or “Store my password” option, you’re out of luck; you’ll have to type in this information with every visit.

When you connect to a shared folder or disk on the network, the opportunity to save the password in your Keychain is equally obvious (Figure 13-17, bottom).

You also see a “Remember password (add to Keychain)” option when you create an encrypted disk image using Disk Utility.

Apple’s Mail program stores your email account passwords in your Keychain. Your .Mac account information is stored there, too (on the .Mac pane of System Preferences).

Microsoft’s Entourage program offers to store your passwords. So do FTP (file-transfer) programs like RBrowser and Fetch; check their Preferences dialog boxes.

A “Remember password” option appears when you type in the password for a wireless network or AirPort base station.

The iTunes program memorizes your Apple Music Store password, too.

If you work alone, the Keychain is automatic, invisible, and generally wonderful. Logging in is the only time you have to type a password. After that, the Mac figures, “Hey, I know it’s you; you proved it by entering your account password. That ID is good enough for me. I’ll fill in all your other passwords automatically.” In Apple parlance, you’ve unlocked your Keychain just by logging in.

But there may be times when you want the Keychain to stop filling in all of your passwords, perhaps only temporarily. Maybe you work in an office where someone else might sit down at your Mac while you’re getting a candy bar.

Of course, you can have Mac OS X lock your Mac—Keychain and all—after a specified period of inactivity (Logout Options).

If you want to lock the Keychain manually, so that no passwords are autofilled in until you unlock it again, you can use any of these methods. Each requires the Keychain Access program (in your Applications→Utilities folder):

Lock the Keychain manually. In the Keychain Access program, choose File→Lock Keychain [Your Name] (

-L), or just click the big padlock at

upper left. Click the Lock button in the toolbar of the

Keychain Access window (Figure 13-18).

-L), or just click the big padlock at

upper left. Click the Lock button in the toolbar of the

Keychain Access window (Figure 13-18).Choose Lock Keychain [Your Name] from the Keychain menulet. To put the Keychain menulet on your menu bar, open Keychain Access, choose Keychain Access→Preferences. In Preferences, click General, and then turn on Show Status in Menu Bar.

Figure 13-17. Top: Safari is one of several Internet-based programs that offer to store your passwords in the Keychain; just click Yes. The next time you visit this Web page, you’ll find your name and password already typed in. Middle: At any time, you can see a complete list of the memorized Web passwords by choosing Safari→Preferences, clicking AutoFill, and then clicking the Edit button next to “User names and passwords.” This is also where you can delete a password, thus making Safari forget it. Bottom: When you connect to a server (a shared disk or folder on the network), just turn on “Remember this password in my keychain.”

Lock the Keychain automatically. In the Keychain Access program, choose Edit→Change Settings for Keychain [your name]. The resulting dialog box lets you set up the Keychain to lock itself, say, five minutes after the last time you used your Mac, or whenever the Mac goes to sleep. When you return to the Mac, you’re asked to re-enter your account password in order to unlock the Keychain, restoring your automatic-password feature.

Whenever the Keychain is locked, Mac OS X no longer fills in your passwords.

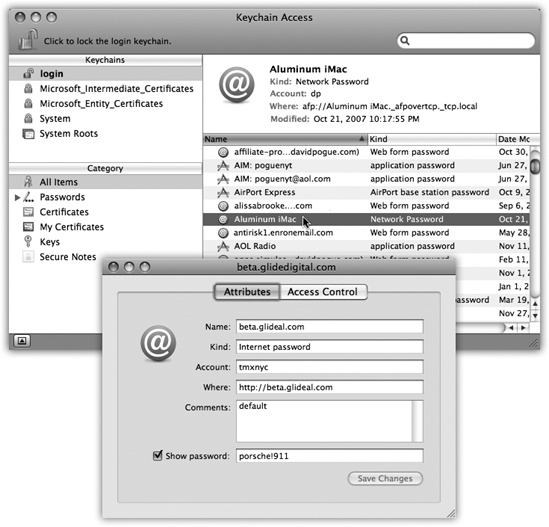

To take a look at your Keychain, open the Keychain Access program. By clicking one of the password rows, you get to see its attributes—name, kind, account, and so on (Figure 13-18).

Figure 13-18. In the main Keychain list, you can double-click a listing for more details about a certain password—including the actual password it’s storing. To see the password, turn on “Show password.” The first time you try this, you’re asked to prove your worthiness by entering your Keychain password (usually your account password). If you then click Always Allow, you won’t be bothered for a password-to-see-this-password again.