When you first turn on a Mac that’s running Mac OS X 10.5, an Apple logo greets you, soon followed by an animated, rotating “Please wait” gear cursor—and then you’re in. No progress bar, no red tape.

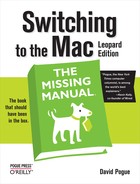

Figure 2-1. Left: On Macs configured to accommodate different people at different times, this is one of the first things you see upon turning on the computer. Click your name. (If the list is long, you may have to scroll to find your name—or just type the first few letters of it.) Right: At this point, you’re asked to type in your password. Type it, and then click Log In (or press Return or Enter; pressing these keys usually “clicks” any blue, pulsing button in a dialog box). If you’ve typed the wrong password, the entire dialog box vibrates, in effect shaking its little dialog-box head, suggesting that you guess again. (See Chapter 13.)

What happens next depends on whether you’re the Mac’s sole proprietor or have to share it with other people in an office, school, or household.

If it’s your own Mac, and you’ve already been through the Mac OS X setup process described in Appendix A, no big deal. You arrive at the Mac OS X desktop.

If it’s a shared Mac, you may encounter the Login dialog box, shown in Figure 2-1. Click your name in the list (or type it, if there’s no list).

If the Mac asks for your password, type it and then click Log In (or press Return). You arrive at the desktop. Chapter 13 offers much more on this business of user accounts and logging in.

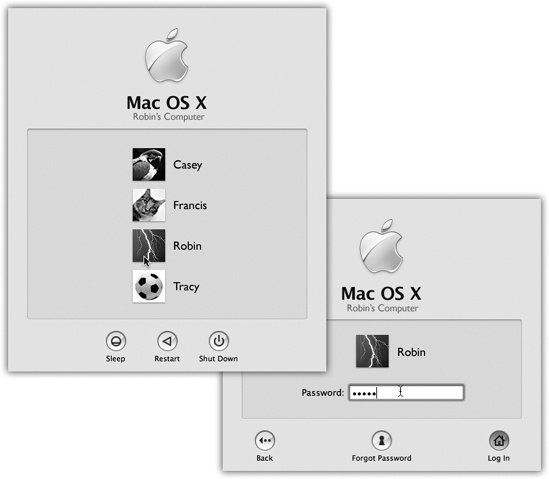

The desktop is the shimmering, three-dimensional Mac OS X landscape shown in Figure 2-2. On a new Mac, it’s covered by a starry galaxy photo that belongs to Leopard’s overall outer-space graphic theme.

If you’ve ever used a computer before, most of the objects on your screen are nothing more than updated versions of familiar elements. Here’s a quick tour.

Figure 2-2. The Mac OS X landscape looks like a more futuristic version of the operating systems you know and love. This is just a starting point, however. You can dress it up with a different background picture, adjust your windows in a million ways, and, of course, fill the Dock with only the programs, disks, folders, and files you need.

In the Mac world, the icons of your hard drive and any other disks attached to your Mac generally appear on your desktop for quick access.

Note

If you prefer the setup in Windows, where disks remain safely caged in the My Computer window—Leopard can accommodate you. Choose Finder→Preferences, click General, and turn off the checkboxes of the disks whose icons you don’t want on the desktop: Hard disks, External disks, and so on.

From now on, you’ll have to look in the Sidebar (The Finder Sidebar) or the Computer window (Go→Computer) to find those disk icons.

This row of translucent, almost photographic icons is a launcher for the programs, files, fo lders, and disks you use often—and an indicator to let you know which programs are already open. In Leopard, they now rest on what appears to be a polished, highly reflective shelf.

Because the Dock is such a critical component of Mac OS X, Apple has decked it out with enough customization controls to keep you busy experimenting for months. You can change its size, move it to the sides of your screen, hide it entirely, and so on. The Quick Look Slideshow begins a complete discussion of using and understanding the Dock.

The ![]() menu at the top left of the screen houses

important Mac-wide commands like Sleep, Restart, and Shut Down. In

a sense, it’s like the Start menu on a diet: It lists recent

programs, system-wide functions, and includes a quick way to jump

to System Preferences.

menu at the top left of the screen houses

important Mac-wide commands like Sleep, Restart, and Shut Down. In

a sense, it’s like the Start menu on a diet: It lists recent

programs, system-wide functions, and includes a quick way to jump

to System Preferences.

The first menu in every program, in boldface, tells you at a glance what program you’re in. The commands in this Application menu include About (which tells you what version of the program you’re using), Preferences, Quit, and others like Hide Others and Show All (which help you control window clutter, as described in Moving windows among screens).

The File and Edit menus come next, exactly as in Windows. The last menu is almost always Help. It opens a miniature Web browser that lets you search the online Mac Help files for explanatory text.

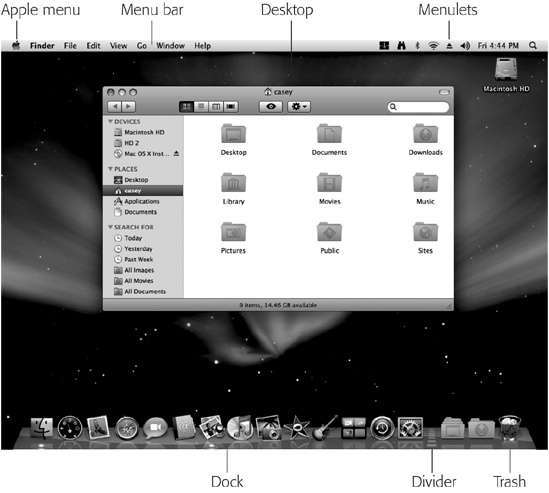

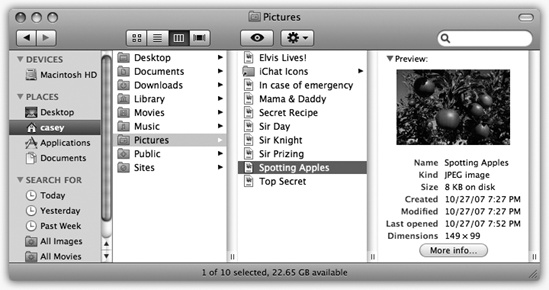

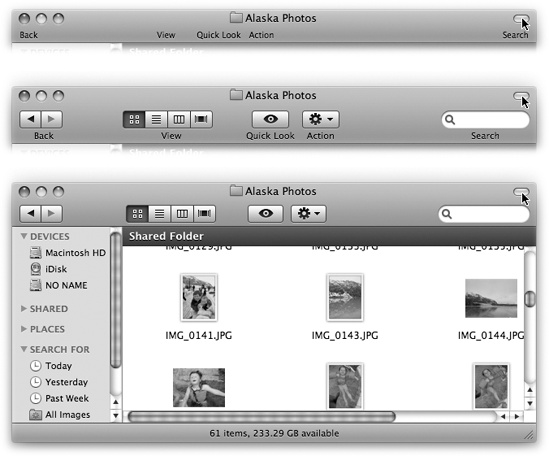

You can view the files and folders in a desktop window in any of four ways: as icons; as a single, tidy list; in a series of neat columns; or as giant document icons that you flip through like they’re CDs in a record-store bin (called Cover Flow view). Figure 2-3 shows the four different views.

Every window remembers its view settings independently. You might prefer to look over your Applications folder in list view (because it’s crammed with files and folders), but you may prefer to view the Pictures folder in icon or Cover Flow view, where the larger icons serve as previews of the photos.

To switch a window from one view to another, just click one of the four corresponding icons in the window’s toolbar, as shown in Figure 2-3.

Figure 2-3. From the top: The same window in icon view, list view, column, and Cover Flow views. Very full folders are best navigated in list or column views, but you may prefer to view emptier folders in icon or Cover Flow views, because larger icons are easier to preview and click. Remember that in any view (icon, list, column, or Cover Flow), you can highlight an icon by typing the first few letters of its name. In icon, list, or Cover Flow view, you can also press Tab to highlight the next icon (in alphabetical order), or Shift-Tab to highlight the previous one.

You can also switch views by choosing View→as Icons (or View→as

Columns, or View→as List, or View→as Cover Flow), which can be handy

if you’ve hidden the toolbar. Or, for less mousing and more hardbodied

efficiency, press ![]() -1,

-1, ![]() -2,

-2, ![]() -3, or

-3, or ![]() -4 for icon, list, column, or Cover Flow view,

respectively.

-4 for icon, list, column, or Cover Flow view,

respectively.

The following pages cover each of these views in greater detail.

Note

One common thread in the following discussions is the availability of the View Options palette, which lets you set up the sorting, text size, icon size, and other features of each view, either one window at a time or for all windows.

Apple gives you a million different ways to open View Options.

You can choose View→Show View Options, or press ![]() -J, or choose Show View Options from the

-J, or choose Show View Options from the

![]() menu at the top of every window.

menu at the top of every window.

In an icon view, every file, folder, and disk is represented by a small picture—an icon. This humble image, a visual representation of electronic bits and bytes, is the cornerstone of the entire Macintosh religion. (Maybe that’s why it’s called an icon.)

Mac OS X offers a number of useful icon-view options, all of

which are worth exploring. Start by opening any icon view window,

and then choose View→Show View Options (![]() -J).

-J).

In Mac OS X Leopard, it’s easy to set up your preferred look for all folder windows on your entire system. With one click on the “Use as Defaults” button (described below), you can change the window view of 20,000 folders at once—to icon view, list view, or whatever you like.

The "Always open in icon view" option lets you override that master setting, just for this window.

For example, you might generally prefer a neat list view with large text. But for your Pictures folder, it probably makes more sense to set up icon view, so you can see a thumbnail of each photo without having to open it.

That’s the idea here. Open Pictures, change it to icon view, and then turn on "Always open in icon view.” Now every folder on your Mac is in list view except Pictures.

Note

The wording of this item in the View Options dialog box changes according to the view you’re in at the moment. In a list-view window, for example, it says “Always open in list view.” In a Cover Flow-view window, it says “Always open in Cover Flow.” And so on. But the function is the same: to override the default (master) setting.

Mac OS X draws the little pictures that represent your icons using sophisticated graphics software. As a result, you (or the Mac) can scale them to almost any size without losing any quality or clarity.

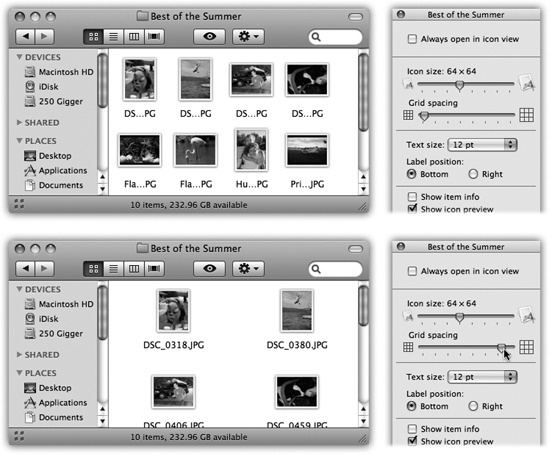

In the View Options window (Figure 2-4), drag the Icon Size slider back and forth until you find a size you like. (For added fun, make little cartoon sounds with your mouth.)

You can control how closely spaced icons are in a window. If you want see a lot of them without making the window bigger, you can pack ‘em in like sardines. Figure 2-4 shows all.

Figure 2-4. Drag the “Grid spacing” slider to specify how tightly packed you want your icons to be. At the minimum setting (top), they’re so crammed that it’s almost ridiculous; you can’t even see their names. But sometimes, you don’t really need to. At more spacious settings (bottom), you get a lot more “white space.”

Using this slider, you can adjust the type size for your icons And for people with especially big or especially small screens—or people with aging retinas—this feature is handy indeed.

Click either Bottom or Right to indicate where you want an icon’s name to appear, relative to its icon. As shown in Figure 2-5, it lets you create, in effect, a multiple-column list view in a single window.

While you’ve got the View Options palette open, try turning on “Show item info.” Suddenly you get a new line of information (in tiny blue type) for certain icons, saving you the effort of opening up the folder or file to find out what’s in it. For example:

Folders. The info line lets you know how many icons are inside each without having to open it up. Now you can spot empties at a glance.

Graphics files. Certain other kinds of files may show a helpful info line, too. For example, graphics files display their dimensions in pixels.

Sounds and QuickTime movies. The light-blue bonus line tells you how long the sound or movie takes to play. For example, an MP3 file might say “03’ 08,” which means three minutes, eight seconds.

.zip files. On compressed archives like .zip files, you get to see the archive’s total size on disk (like “48.9 MB”).

You can see some of these effects illustrated in Figure 2-4.

Figure 2-5. The View Options dialog box for an icon view window offers the chance to create colored backgrounds for certain windows or even to use photos as window wallpaper (bottom). Using a photo may have a soothing, annoying, or comic effect—like making the icon names completely unreadable. (Note, by the way, how the icon’s names have been set to appear beside the icons, rather than underneath. You now have all the handy, freely draggable convenience of an icon view, along with the more compact spacing of a list view.)

This option pertains primarily to graphics, which Mac OS X often displays only with a generic icon (stamped with the file type, like JPEG, TIFF, or PDF). But if you turn on “Show icon preview,” Mac OS X turns each icon into a miniature display of the image itself, as shown in Figure 2-5. It’s ideal for working with folders full of digital photos.

Tip

A small but delicious point: You can tell just by looking at a PDF file’s icon whether it’s longer than one page. The icon for a one-page PDF has a curled upper-right corner. But on a multi-page PDF, only the first page’s corner curls down. And in the gap it reveals, you can see a tiny bit of the actual FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTION: All About “Leopard” showing!

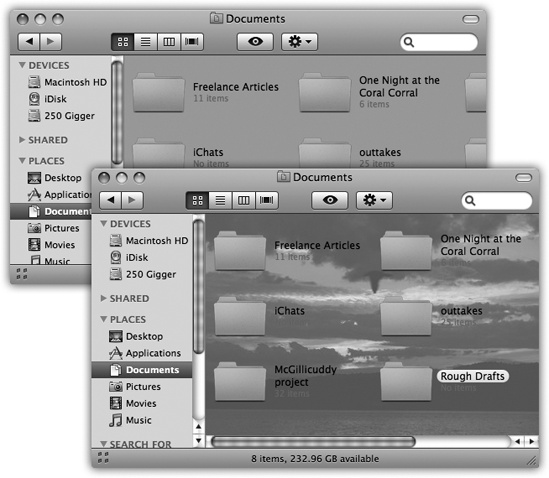

Here’s another Mac OS X luxury that other operating systems can only dream about: You can fill the background of any icon view window on your Mac with a certain color—or even a photo.

Color-coordinating or “wallpapering” certain windows is more than just a gimmick. In fact, it can serve as a timesaving psychological cue. Once you’ve gotten used to the fact that your main Documents folder has a sky-blue background, you can pick it out like a sharpshooter from a screen filled with open windows. Color-coded Finder windows are also especially easy to distinguish at a glance when you’ve minimized them to the Dock.

Note

Background colors and pictures disappear in list, column, and Cover Flow views.

Once a window is open, choose View→View Options

(![]() -J). The bottom of the resulting dialog box

offers three choices, whose results are shown in Figure 2-5.

-J). The bottom of the resulting dialog box

offers three choices, whose results are shown in Figure 2-5.

White. This is the standard option (not shown).

Color. When you click this button, you see a small rectangular button beside the word Color. Click it to open the Color Picker (UP TO SPEED: The Color Picker), which you can use to choose a new background color for the window. (Unless it’s April Fool’s Day, pick a light color. If you choose a dark one—like black—you won’t be able to make out the lettering of the icons’ names.)

Picture. If you choose this option, a Select button appears. Click it to open the Select a Picture dialog box, already open to your Library→Desktop Pictures folder. Now choose a graphics file—one of Apple’s in the Desktop Pictures folder, or one of your own. When you click Select, you see that Mac OS X has superimposed the window’s icons on the photo. As you can see in Figure 2-5, low-contrast or light-background photos work best for legibility.

Incidentally, Mac OS X makes no attempt to scale down a selected photo to fit neatly into the window. If you have a high-res digital camera, therefore, you see only the upper-left corner of a photo in the window. Use a graphics program to scale the picture down to something smaller than your screen resolution for better results.

This harmless-looking button can actually wreak havoc—or restore order to your kingdom—with a single click. It applies the changes you’ve just made in the View Options dialog box to all windows on your Mac (instead of only the frontmost window).

If you set up the frontmost window with a colored background, big icons, small text, and a tight grid, and then you click Use as Defaults, you’ll see that look in every disk or folder window you open.

You’ve been warned.

Fortunately, there are two auxiliary controls that can give you a break from all the sameness.

First, you can set up individual windows to be weirdo exceptions to the rule; see "Always open in icon view,” above.

Second, you can remove any departures from the default window view—after a round of disappointing experimentation on a particular window, for example—using a secret button. To do so, choose View→Show View Options to open the View Options dialog box. Now hold down the Option key. The Use as Defaults button magically changes to say “Restore to Defaults,” which means “Abandon all the changes I’ve foolishly made to the look of this window.”

In general, you can drag icons anywhere within a window. For example, some people like to keep current project icons at the top of the window and move older stuff to the bottom.

If you’d like Mac OS X to impose a little discipline on you, however, it’s easy enough to request a visit from an electronic housekeeper who tidies up your icons by aligning them neatly to an invisible grid. In Leopard, you can even specify how tight or loose that grid is.

Mac OS X offers an enormous number of variations on the “snap icons to the underlying rows-and-columns grid” theme:

Aligning individual icons to the grid. Press the

key while dragging an icon or several

highlighted icons. (Don’t press the key until after you begin

to drag.) When you release the mouse, the icons you’ve moved

all jump into neatly aligned positions.

key while dragging an icon or several

highlighted icons. (Don’t press the key until after you begin

to drag.) When you release the mouse, the icons you’ve moved

all jump into neatly aligned positions.Aligning all icons to the grid. Choose View→Clean Up (if nothing is selected) or View→Clean Up Selection (if some icons are highlighted). Now all icons in the window, or those you’ve selected, jump to the closest positions on the invisible underlying grid.

These same commands appear in the shortcut menu when you right-click anywhere inside an icon-view window, which is handier if you have a huge monitor.

Tip

If you press Option, you swap the wording of the command. Clean Up changes to read Clean Up Selection, and vice versa.

Note, by the way, that the grid alignment is only temporary. As soon as you drag icons around, or add more icons to the window, the newly moved icons wind up just as sloppily positioned as before you tidied up.

If you want the Mac to lock all icons

to the closest spot on the grid whenever you

move them, choose View→Show View Options (![]() -J); from the “Arrange by” pop-up menu,

choose Snap to Grid.

-J); from the “Arrange by” pop-up menu,

choose Snap to Grid.

Even then, though, you’ll soon discover that none of these grid-snapping techniques move icons into the most compact possible arrangement. If one or two icons have wandered off from the herd to a far corner of the window, they’re merely nudged to the grid points closest to their current locations. They aren’t moved all the way back to the group of icons elsewhere in the window.

To solve that problem, use one of the sorting options described next.

If you’d rather have icons sorted and bunched together on the underlying grid—no strays allowed—make a selection from the View menu:

Sorting all icons for the moment. If you choose View→Arrange By→Name, all icons in the window snap to the invisible grid and sort themselves alphabetically. Use this method to place the icons as close as possible to each other within the window, rounding up any strays.

The other subcommands in the View→Arrange By menu work similarly (Size, Date Modified, Label, and so on), but sort the icons according to different criteria.

As with the Clean Up command, View→Arrange By serves only to reorganize the icons in the window at this moment. If you move or add icons to the window, they won’t be sorted properly. If you’d rather have all icons remain sorted and clustered, try this:

Sorting all icons permanently. You can also tell your Mac to maintain the sorting and alignment of all icons in the window, present and future. Now if you add more icons to the window, they jump into correct alphabetical position; if you remove icons, the remaining ones slide over to fill in the resulting gap. This setup is perfect for neat freaks.

To make it happen, open the View menu, hold down the Option key, and choose from the “Keep Arranged By” submenu (choose Name, Date Modified, or whatever sorting criterion you like). Your icons are now locked into sorted position, as compactly as the grid permits.

In windows that contain a lot of icons, the list view is a powerful weapon in the battle against chaos. It shows you a tidy table of your files’ names, dates, sizes, and so on. In Leopard, alternating blue and white background stripes help you read across the columns in a list-view window.

You have a great deal of control over your columns, in that you get to decide how wide they should be, which of them should appear, and in what order (except that Name is always the first column). Here’s how to master these columns:

Most of the world’s list-view fans like their files listed alphabetically. It’s occasionally useful, however, to view the newest files first, largest first, or whatever.

When a desktop window displays its icons in a list view, a convenient new strip of column headings appears (Figure 2-6). These column headings aren’t just signposts; they’re buttons, too. Click Name for alphabetical order, Date Modified to view newest first, Size to view largest files at the top, and so on.

Figure 2-6. You control the sorting order of a list view by clicking the column headings (top). Click a second time to reverse the sorting order (bottom). You’ll find the identical ▴ or ▾ triangle—indicating the identical information—in email programs, in iTunes, and anywhere else where reversing the sorting order of the list can be useful.

It’s especially important to note the tiny, dark gray triangle that appears in the column you’ve most recently clicked. It shows you which way the list is being sorted.

When the triangle points upward, the oldest files, smallest files, or files beginning with numbers (or the letter A) appear at the top of the list, depending on which sorting criterion you have selected.

Tip

It may help you to remember that when the smallest portion of the triangle is at the top (▴), the smallest files are listed first when viewed in size order.

To reverse the sorting order, click the column heading a second time. Now the newest files, largest files, or files beginning with the letter Z appear at the top of the list. The tiny triangle turns upside-down.

One of the Mac’s most attractive features is the tiny triangle that appears to the left of a folder’s name in a list view. In its official documents, Apple calls these buttons disclosure triangles; internally, the programmers call them flippy triangles.

Either way, these triangles are very useful: When you click one, the list view turns into an outline, which displays the contents of the folder in an indented list, as shown in Figure 2-7. Click the triangle again to collapse the folder listing. You’re saved the trouble and clutter of opening a new window just to view the folder’s contents.

By selectively clicking flippy triangles, you can, in effect, peer inside two or more folders simultaneously, all within a single list view window. You can move files around by dragging them onto the tiny folder icons.

Choose View→Show View Options. In the dialog box that appears, you’re offered on/off checkboxes for the different columns of information Mac OS X can show you: Date Modified, Size, Kind, and so on.

The View Options for a list view include several other useful

settings; choose View→Show View Options, or press ![]() -J.

-J.

Always open in list view. Turn on this option to override your system-wide preference setting for all windows. See in "Always open in icon view" for details.

Icon size. These two buttons offer you a choice of icon size for the current window: either standard or tiny. Unlike icon view, list view doesn’t give you a size slider.

Fortunately, even the tiny icons aren’t so small that they show up blank. You still get a general idea of what they’re supposed to look like.

Text size. As described in Text size, you can change the type size for your icon labels, either globally or one window at a time.

Show columns. Turn on the columns you’d like to appear in the current window’s list view, as described in the previous section.

Use relative dates. In a list view, the Date Modified and Date Created columns generally display information in a format like this: “Sunday, March 9, 2008.” (As noted below, the Mac uses shorter date formats as the column gets narrower.) But when the “Use relative dates” option is turned on, the Mac substitutes the word “Yesterday” or “Today” where appropriate, making recent files easier to spot.

Calculate all sizes. See the box on the facing page.

Show icon preview. Exactly as in icon view, this option turns the icons of graphics files into miniatures of the photos or images within.

Use as Defaults. Click to make your changes in the View Options box apply to all windows on your Mac. (Option-click this button to restore a wayward window back to your defaults.)

You’re stuck with the Name column at the far left of a window. However, you can rearrange the other columns just by dragging their gray column headers horizontally. If the Mac thinks you intend to drop a column to, say, the left of the column it overlaps, you’ll actually see an animated movement—indicating a column reshuffling—even before you release the mouse button.

If you place your cursor carefully on the dividing line between two column headings, you’ll find that you can drag the divider line horizontally. Doing so makes the column to the left of your cursor wider or narrower.

What’s delightful about this activity is watching Mac OS X scramble to rewrite its information to fit the space you give it. For example, as you make the Date Modified (or Created) column narrower, “Sunday, March 9, 2008, 2:22 PM” shrinks first to “Sun, Mar 9, 2008, 2:22 PM,” then to “3/9/08, 2:22 PM,” and finally to a terse “3/9/08.”

If you make a column too narrow, Mac OS X shortens the file names, dates, or whatever by removing text from the middle. An ellipsis (...) appears to show you where the missing text would have appeared. (Apple reasoned that truncating the ends of file names, as in some other operating systems, would hide useful information like the number at the end of “Letter to Marge 1,” “Letter to Marge 2,” and so on. It would also hide the three-letter extensions, such as Thesis .doc, that may appear on file names in Mac OS X.)

For example, suppose you’ve named a Word document “Ben Affleck—A Major Force for Humanization and Cure for Depression, Acne, and Migraine Headache.” (Yes, file names can really be that long.) If the Name column is too narrow, you might see only “Ben Affleck—A Major...Migraine Headache.”

Tip

You don’t have to make the column mega-wide just to read the full text of a file whose name has been shortened. Just point to the icon’s name without clicking. After a moment, a yellow, floating balloon appears—something like a tooltip in Windows—to identify the full name.

And if you don’t feel like waiting, hold down the Option key. As you whip your mouse over truncated file names, their tooltip balloons appear instantaneously. (Both of these tricks work in list, column, or Cover Flow views—and in Save and Open dialog boxes, for that matter.)

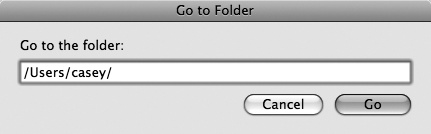

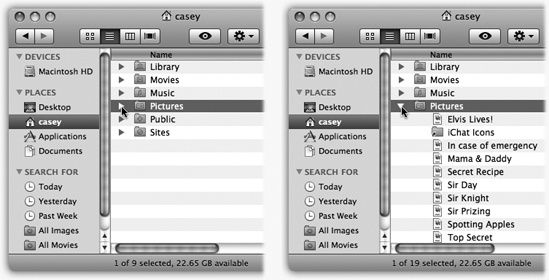

The goal of column view is simple: to let you burrow down through nested folders without leaving a trail of messy, overlapping windows in your wake.

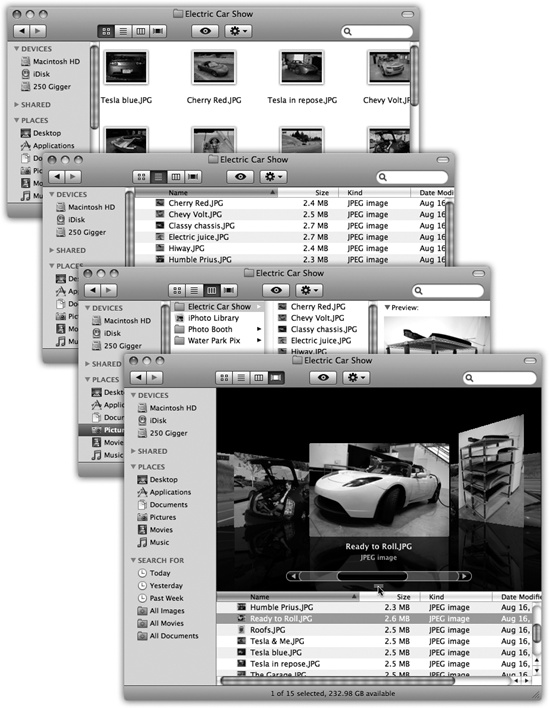

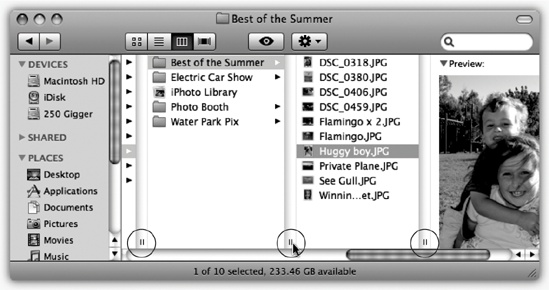

The solution is shown in Figure 2-8. It’s a list view that’s divided into several vertical panes. The first pane (not counting the Sidebar) shows whatever disk or folder you first opened.

Figure 2-8. If the rightmost folder contains pictures, sounds, Office documents, or movies, you can look at them or play them, right there in the Finder. You can drag this jumbo preview icon anywhere—into another folder or the Trash, for example.

When you click a disk or folder in this list (once), the second pane shows a list of everything in it. Each time you click a folder in one pane, the pane to its right shows what’s inside. The other panes slide to the left, sometimes out of view. (Use the horizontal scroll bar to bring them back.) You can keep clicking until you’re actually looking at the file icons inside the most deeply nested folder.

If you discover that your hunt for a particular file has taken you down a blind alley, it’s not a big deal to backtrack, since the trail of folders you’ve followed to get here is still sitting before you on the screen. As soon as you click a different folder in one of the earlier panes, the panes to its right suddenly change, so that you can burrow down a different rabbit hole.

Furthermore, the Sidebar is always at the ready to help you jump to a new track; just click any disk or folder icon there to select a new first-column listing for column view.

The beauty of column view is, first of all, that it keeps your

screen tidy. It effectively shows you several simultaneous folder

levels, but contains them within a single window. With a quick

![]() -W, you can close the entire window, panes and

all. Second, column view provides an excellent sense of where you are.

Because your trail is visible at all times, it’s much harder to get

lost—wondering what folder you’re in and how you got there—than in any

other window view.

-W, you can close the entire window, panes and

all. Second, column view provides an excellent sense of where you are.

Because your trail is visible at all times, it’s much harder to get

lost—wondering what folder you’re in and how you got there—than in any

other window view.

Tip

In Leopard, for the first time, you can change how Column view

is sorted; it doesn’t have to be alphabetical. Press

![]() -J to open the View Options dialog box, and

then choose the sorting criterion you want from the “Arrange by”

pop-up menu (like Size, Date Created, or Label).

-J to open the View Options dialog box, and

then choose the sorting criterion you want from the “Arrange by”

pop-up menu (like Size, Date Created, or Label).

The number of columns you can see without scrolling depends on the width of the window. In no other view are the zoom and resize controls as important as they are here.

That’s not to say, however, that you’re limited to four columns (or whatever fits on your monitor). You can make the columns wider or narrower—either individually or all at once—to suit the situation, according to this scheme:

To make a single column wider or narrower, drag its right-side handle (circled in Figure 2-9).

Figure 2-9. What you want to do most of the time is adjust one column. Adding the Option key as you drag the handle lets you adjust all columns at once.

To make all the columns wider or narrower simultaneously, hold down the Option key as you drag that right-side handle.

And here’s the tip of the week: Double-click one of the right-side handles to make the column precisely as wide as necessary to reveal all the names of its contents.

Best of all, you can Option-double-click any column’s right-side handle to make all columns just as wide as necessary.

Just as in icon and list view, you can choose View→Show View Options to open a dialog box—a Spartan one, in this case—offering additional control over your column views.

Always open in column view. Once again, this option lets you override your system-wide preference setting for all windows. See in "Always open in icon view" for details.

Text size. Whatever point size you choose here affects the type used for icons in all column views.

Show icons. For maximum speed, turn off this option. Now you see only file names—not the tiny icons next to them—in all column views.

Show icon preview. In Leopard, you can request that the tiny icons in column view display their actual contents—photos show their images, Word and PDF documents show the first page, and so on. Of course, this feature isn’t always terrifically useful, since the icons are the size of a hydrogen atom; but now and then, you can get the general gist of what’s in a file just by its overall shape and color.

Show preview column. The far-right Preview column can be handy when you’re browsing graphics, sounds, or movie files. Feel free to enlarge this final column when you want a better view of the picture or movie; you can make it really big. Almost Quick Look big.

The rest of the time, though, the Preview column can get in the way, slightly slowing down the works and pushing other, more useful columns off to the left side of the window. If you turn off this checkbox, the Preview column doesn’t appear.

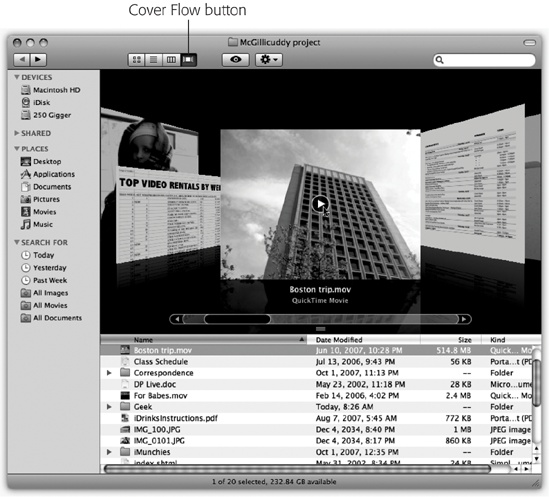

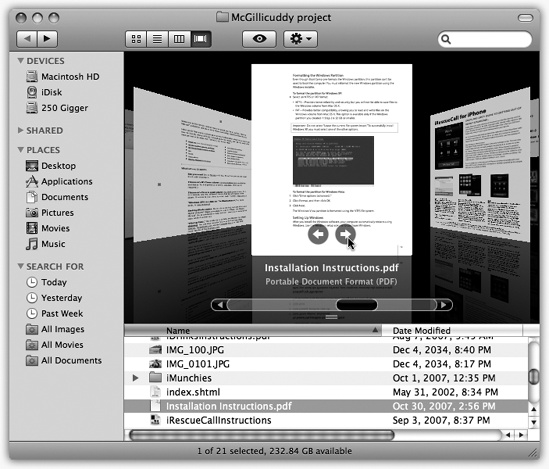

As you can sort of see from Figure 2-10, Cover Flow is a visual display that Apple stole from its own iTunes software, where Cover Flow simulates the flipping “pages” of a jukebox, or the CDs in a record-store bin. There, you can flip through your music collection, marveling as the CD covers flip over in 3-D space while you browse.

The idea is the same in Mac OS X, except that now it’s not CD covers you’re flipping; it’s gigantic file and folder icons.

To fire up Cover Flow, open a window. Then click the Cover Flow

button identified in Figure 2-10, or choose View→as

Cover Flow, or press ![]() -4.

-4.

Figure 2-10. The bottom half of a Cover Flow window is identical to list view. The top half, however, is an interactive, scrolling “CD bin” full of your own stuff. It’s especially useful for photos, PDF files, Office documents, and text documents. And when a movie comes up in this virtual data jukebox, you can point to the little ▸ button and click it to play the video, right in place.

Now the window splits. On the bottom: a traditional list view, complete with sortable columns, exactly as described above.

On the top: the gleaming, reflective, black Cover Flow display. Your primary interest here is the scroll bar. As you drag it left or right, you see your own files and folders float by and flip in 3-D space. Fun for the whole family!

The effect is spectacular, sure. It’s probably not something you’d want to set up for every folder, though, because browsing is a pretty inefficient way to find something. But in folders containing photos or movies (that aren’t filled with hundreds of files), Cover Flow can be a handy and satisfying way to browse.

And now, notes on Cover Flow:

You can adjust the size of Cover Flow display (relative to the list-view half) by dragging up or down on the grip strip area just beneath the Cover Flow scroll bar.

Multipage PDF documents are special. When you point to one, circled arrow buttons appear on the jumbo icon. You can click them to page through the document—without even opening it for real (Figure 2-11).

QuickTime movies are special, too. When you point to its jumbo display, a ▸ button appears. Click it to play the movie, right there in the Cover Flow window (Figure 2-10).

You can navigate with the keyboard, too. Any icon that’s highlighted in the list view (bottom half of the window) is also front and center in the Cover Flow view. Therefore, you can use all the usual list-view shortcuts to navigate both at once. Use the up or down arrow keys, type the first few letters of an icon’s name, press Tab or Shift-Tab to highlight the next or previous icon alphabetically, and so on.

Cover Flow shows whatever the list view shows. If you expand a flippy triangle to reveal an indented list of what’s in a folder, the contents of that folder now become part of the cover flow.

The previews are actual icons. When you’re looking at a Cover Flow minidocument, you can drag it with your mouse—you’ve got the world’s biggest target—anywhere you’d like to drag it: another folder, the Trash, whatever.

As the preceding several thousand pages make clear, there are lots of ways to view and manage the seething mass of files and folders on a typical hard drive. Some of them actually let you see what’s in a document without having to open it—the Preview column in column view, the giant icons in Cover Flow, and so on.

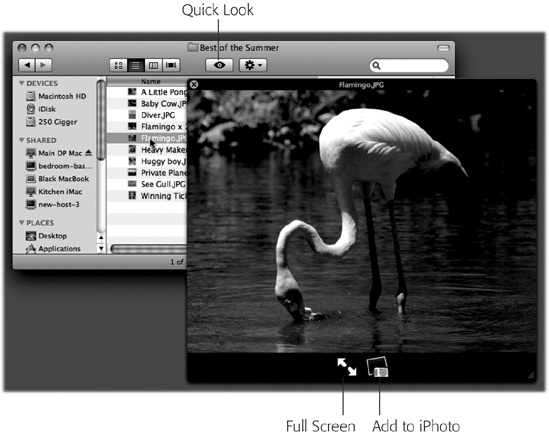

Quick Look, a star feature of Leopard, takes this idea to another level. It lets you open and browse a document nearly at full size—without switching window views or opening any new programs. You highlight an icon (or several), and then press the Space bar (or click the eyeball icon at the top of the window).

Figure 2-12. Once the Quick Look window is open, you can play the file (movies and sounds), study it in more detail (most kinds of graphics files), or even read it (PDF, Word, and Excel documents). You can also click another icon, and another, and another, without ever closing the preview; the contents of the window simply change to reflect whatever you’ve just clicked. Supertip: Quick Look even works on icons in the Trash, too, so you can figure out what something is before you nuke it forever.

The Quick Look window now opens, showing a nearly full-size preview of the document (Figure 2-12). Rather nice, eh?

The idea here is that you can check out a document without having to wait for it to open in the traditional way. For example, you can find out what’s in a Word, Excel, or PowerPoint document without actually having to open Word, Excel, or PowerPoint, which saves you about 45 minutes.

You might wonder: How, exactly, is Quick Look able to display the contents of a document without opening it? Wouldn’t it have to somehow understand the internal file format of that document type?

Exactly. And that’s why Quick Look doesn’t recognize all documents. If you try to preview, for example, a Final Cut Pro video project, a sheet-music file, a .zip archive, or a database file, all you’ll see is a six-inch-tall version of its generic icon. You won’t see what’s inside.

Over time, people will write plug-ins for those nonrecognized programs. Already, plug-ins that let you see what’s inside folders and .zip files await at www.qlplugins.com. In the meantime, here’s what Quick Look recognizes right out of the box:

Graphics files and photos. This is where Quick Look can really shine, because it’s often useful to get a quick look at a photo without having to haul iPhoto or Photoshop out of bed. Quick Look recognizes all common graphics formats, including TIFF, JPEG, GIF, PNG, RAW, and Photoshop documents.

PDF and text files. Using the scroll bar, you can page through multipage documents, right there in the Quick Look window.

Audio and movie files. They begin to play instantly when you open them into the Quick Look window. Most popular formats are recognized (MP3, AIFF, AAC, MPEG4, H.264, and so on). A scroll bar appears so that you can jump around in the movie or song.

Microsoft Word, Excel, and PowerPoint documents. Because these formats are so common, Mac OS X comes with a Quick Look plug-in to recognize them. Move through the pages using the vertical scroll bar; switch to a different Excel spreadsheet page using the Sheet tabs at the bottom.

Fonts. Totally cool. When you open a font file in Quick Look, you get a crystal-clear, huge sampler that shows every letter of the alphabet in that typeface.

vCards. A vCard is an address-book entry that people can send by email to each other to save time in updating their Rolodexes. When you drag a name out of Apple’s or Microsoft’s address books and onto the desktop, for example, it turns into a vCard document. In Quick Look, the vCard opens up as a handsomely formatted index card that displays all of the person’s contact information.

Pages, Numbers, Keynote, and TextEdit documents. Naturally, since these are Apple programs, Quick Look understands the document formats.

HTML (Web pages). If you’ve saved some Web pages to your hard drive, here’s a great way to inspect them without firing up your Web browser.

To exit the Quick Look display, press the Space bar again.

Here are some stunts that make Quick Look even more interesting.

Zoom in or out. Option-click the preview to magnify it; drag inside the zoomed-in image to scroll; Shift-Option-click to zoom back out. Or press Option as you turn your mouse’s scroll wheel. (PDF documents have their own zoom in/zoom out keystrokes:

-plus and

-plus and  -minus.)

-minus.)Full screen. When you click the Full Screen arrows (identified in Figure 2-12), your screen goes black, and the Quick Look window expands to fill it. Keep this trick in mind when you’re trying to read Word, Excel, or PDF documents, since the text is usually too small to read otherwise. (When you’re finished with the closeup, click the Full Screen button again to restore the original Quick Look window, or the

button to exit Quick Look

altogether.)

button to exit Quick Look

altogether.)Tip

How’s this for an undocumented shortcut?

If you Option-click the eyeball icon in any Finder window, you go straight into Full Screen mode without having to open the smaller Quick Look window first. Kewl.

Figure 2-13. Once the slideshow is underway, you can use this control bar. It lets you pause the slideshow, move forward or backward manually, enlarge the current “slide” to fill the screen, or end the show. The Index view is especially handy. (You can press

-Return to “click” the Index View

button.) It displays an array of labeled miniatures, all at

once—a sort of Exposé for Quick Look. Click a thumbnail to

jump directly to the Quick Look document you want to

inspect.

-Return to “click” the Index View

button.) It displays an array of labeled miniatures, all at

once—a sort of Exposé for Quick Look. Click a thumbnail to

jump directly to the Quick Look document you want to

inspect.Previous

Pause

Next

Index View

Add to iPhoto

Exit Full Screen

Exit Quick Look

Add to iPhoto. This icon appears in the Quick Look windows of graphics files that you’re examining. Click it to add the picture you’re studying to your iPhoto photo collection.

Keep it going. Once you’ve opened Quick Look for one icon, you don’t have to close it before inspecting another icon. Just keep clicking different icons; the Quick Look window changes instantly with each click to reflect the new document.

Highlight a bunch of icons, and then open

Quick Look. The screen goes black, and the documents begin their

slideshow. Each image appears on the screen for about three seconds

before the next one appears. (Press the Esc key or

![]() -period to end the show.)

-period to end the show.)

It’s a useful enough feature when you’ve just downloaded or imported a bunch of photos or Office documents and want a quick look through them. Use the control bar shown in Figure 2-13 to manage the playback.

Note

This same slideshow mechanism is available for graphics in Preview and Mail.

For years, most operating systems maintained two different lists of programs. One listed unopened programs until you needed them, like the Start menu in Windows. The other kept track of which programs were open at the moment for easy switching, like the Windows taskbar.

In Mac OS X, Apple combined both functions into a single strip of icons called the Dock.

Apple starts the Dock off with a few icons it thinks you’ll enjoy: Dashboard, QuickTime Player, iTunes, iChat, Mail, the Safari Web browser, and so on. But using your Mac without putting your own favorite icons in the Dock is like buying an expensive suit and turning down the free alteration service. At the first opportunity, you should make the Dock your own.

The concept of the Dock is simple: Any icon you drag onto it (Figure 2-14) is installed there as a button.)

A single click, not a double-click, opens the corresponding icon. In other words, the Dock is an ideal parking lot for the icons of disks, folders, documents, programs, and Internet bookmarks that you access frequently.

Here are a few aspects of the Dock that may throw you at first:

It has two sides. See the whitish dotted line running down the Dock? That’s the divider (Figure 2-14). Everything on the left side is an application—a program. Everything else goes on the right side: files, documents, folders, disks, and minimized windows.

It’s important to understand this division. If you try to drag an application to the right of the line, for example, Mac OS X teasingly refuses to accept it. (Even aliases observe that distinction. Aliases of applications can go only on the left side, and vice versa.)

Figure 2-14. To add an icon to the Dock, simply drag it there. You haven’t moved the original file; when you release the mouse, it remains where it was. You’ve just installed a pointer—like a Macintosh alias or Windows shortcut.

Divider

←Programs side Everything else→

Open programs

Minimized document windows

Its icon names are hidden. To see the name of a Dock icon, point to it without clicking. You’ll see the name appear above the icon.

When you’re trying to find a certain icon in the Dock, run your cursor slowly across the icons without clicking; the icon labels appear as you go. You can often identify a document just by looking at its icon.

Folders and disks sprout stacks. If you click a folder or disk icon in the right side of the Dock, a list of its contents sprouts from the icon. It’s like X-ray vision without the awkward moral consequences. Turn the page for details on stacks.

Programs appear there unsolicited. Nobody but you (and Apple) can put icons on the right side of the Dock. But program icons appear on the left side of the Dock automatically whenever you open a program, even one that’s not listed in the Dock. Its icon remains there for as long as it’s running.

You can move the tiles of the Dock around by dragging them horizontally. As you drag, the other icons scoot aside to make room. When you’re satisfied with its new position, drop the icon you’ve just dragged.

To remove a Dock icon, just drag it away. (You can’t remove the icons of the Finder, the Trash, the Dock icon of an open program, or any minimized document window.) Once your cursor has cleared the Dock, release the mouse button. The icon disappears, its passing marked by a charming little puff of animated cartoon smoke. The other Dock icons slide together to close the gap.

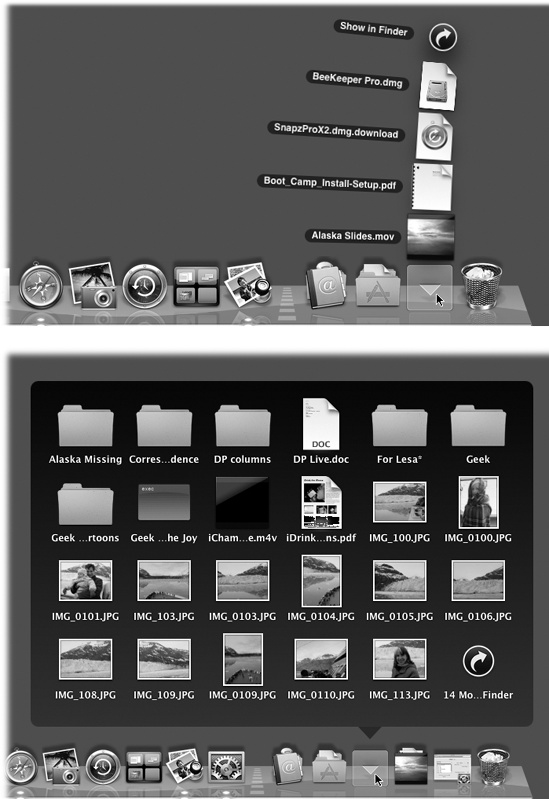

A stack is what you get when you click a disk or folder icon on the Dock—and it’s one of Leopard’s marquee new features. The effect is shown in Figure 2-15.

Tip

If you press Shift as you click, the stack opens in slow motion. Amaze your friends.

In essence, Mac OS X is fanning out the folder’s contents so you can see all of them. If it could talk, it would be saying, “Pick a card, any card.”

Sometimes there are too many icons in a folder to fit in a fan. In that case, the stack becomes a grid instead (Figure 2-15, bottom). The grid, of course, holds many more icons than the fan, although it’s not as pretty.

But you can force a certain Dock folder to sprout a fan or a grid all the time, rather than letting Mac OS X decide. From the Dock folder’s shortcut menu (Using the Dock), choose “View content as”→Fan or “View content as”→Grid (instead of the factory setting, “View content as”→Automatic).

From now on, you’ll always get the fan, or always get the grid.

Note

When your Dock is positioned on a side of the screen instead of the bottom, you always get the grid, never the fan. The View As command doesn’t even appear in the shortcut menu.

Truth is, though, that both the grid and the fan have limited storage space for icons; the exact number depends on your monitor size. In any case, if there are too many icons to display at once, the last icon says, “24 more in Finder” (or whatever the number is). Click that icon to open the folder’s regular window, where all the contents are available.

Of course, then you’ve defeated the fan’s step-saving purpose.

Maybe that’s why many Mac fans choose View Content As→List from each Dock folder’s shortcut menu (an option in version 10.5.2 and later). Now, when you click a folder in the Dock, you get a simple pop-up list of everything in that folder.

When you first install Mac OS X 10.5, you get a couple of starter stacks just to get you psyched. One is called Downloads; the other is Documents. (Both of these folders are physically inside your Home folder. But you may well do most of your interacting with them on the Dock.)

The Downloads folder, new in Leopard, collects three kinds of Internet arrivals:

Files you download from the Web using Safari

Files you receive in an iChat file-transfer session

File attachments you get via email using Mail.

Unless you intervene, they’re sorted by the date you downloaded them.

It’s handy to know where to find your downloads, and nice not to have them all cluttering your desktop.

Figure 2-15. Top: When you click the icon of a folder or disk on the Dock (just one single click), you get this effect: a rainbow that shows what’s inside. Click an icon to open it, just as though you’d double-clicked it in a window. You can even Option-click one icon after another, opening them all while the stack remains arrayed before you. Or grab an icon and drag it right out of the stack—into another window, say. Bottom: If there are too many icons to fit in the arc (as determined by your monitor size), you get this grid instead. Alas, here, too, space is limited. If there are more than fits on the grid, click the “35 more in Finder” icon at the lower right. You go to the folder’s standard Finder window, where you can see the complete list of icons.

Creating a new stack is easy. Just drag any folder or disk icon onto the right end of the Dock. That’s right: All folders and disks become stacks when clicked on the Dock.

Therefore, to get a stack off the Dock, drag its folder icon away from the Dock and let go. You’re not deleting the actual folder—just its Dock shortcut.

Tip

When you first add a folder icon to the Dock, its shortcut menu (Using the Dock) starts out saying “Display as”→Stack. In this condition, folder icons on the Dock start out change to reflect their contents. The Downloads folder, for example, takes on the icon of whatever was most recently added to it. That can be a little disorienting, since you can’t get to know a folder by its icon—it keeps changing!

The solution is simple: From the “Display as” section of the Dock folder’s pop-up menu, choose Folder.

The bottom of the screen isn’t necessarily the ideal location for the Dock. All Mac screens are wider than they are tall, so the Dock eats into your limited vertical screen space. You have three ways out: Hide the Dock, shrink it, or rotate it 90 degrees.

To turn on the Dock’s auto-hiding feature, choose

![]() →Dock→Turn Hiding On (or press

Option-

→Dock→Turn Hiding On (or press

Option-![]() -D).

-D).

When the Dock is hidden, it doesn’t slide into view until you move the cursor to the Dock’s edge of the screen. When you move the cursor back to the middle of the screen, the Dock slithers out of view once again. (Individual Dock icons may occasionally shoot upward into Desktop territory when a program needs your attention—cute, very cute—but otherwise, the Dock lies low until you call for it.)

On paper, an auto-hiding Dock is ideal; it’s there only when you summon it. In practice, however, you may find that the extra half-second the Dock takes to appear and disappear makes this feature slightly less appealing.

Many Mac fans prefer to hide and show the Dock at will by

pressing the hide/show keystroke, Option-![]() -D. This method makes the Dock pop on and

off the screen without requiring you to move the cursor.

-D. This method makes the Dock pop on and

off the screen without requiring you to move the cursor.

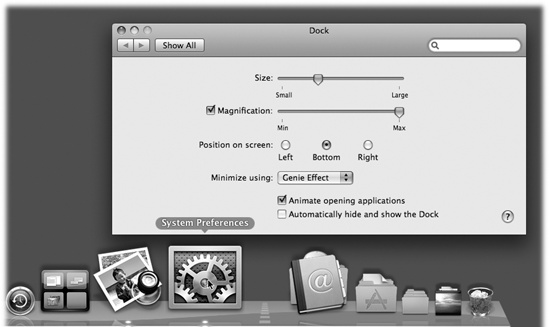

Depending on your screen’s size, you may prefer smaller or

larger Dock buttons. The official way to resize them goes like

this: Choose ![]() →Dock→Dock Preferences. In the resulting

dialog box, drag the Dock Size slider, as shown in Figure 2-16.

→Dock→Dock Preferences. In the resulting

dialog box, drag the Dock Size slider, as shown in Figure 2-16.

There’s a much faster way to resize the Dock, however: Just position your cursor carefully in the Dock’s divider line, so that it turns into a double-headed arrow. Now drag up or down to shrink or enlarge the Dock.

You may not be able to enlarge the Dock, especially if it contains a lot of icons. But you can make it almost infinitely smaller. This may make you wonder: How can you distinguish between icons if they’re the size of molecules?

The answer lies in the ![]() →Dock→Turn Magnification On command. What

you’ve just done is trigger the swelling effect shown in Figure 2-16. Now your Dock

icons balloon to a much larger size as your cursor passes over

them. It’s a weird, magnetic, rippling, animated effect that takes

some getting used to. But it’s another spectacular demonstration

of the graphics technology in Mac OS X, and it can actually come

in handy when you find your icons shrinking away to

nothing.

→Dock→Turn Magnification On command. What

you’ve just done is trigger the swelling effect shown in Figure 2-16. Now your Dock

icons balloon to a much larger size as your cursor passes over

them. It’s a weird, magnetic, rippling, animated effect that takes

some getting used to. But it’s another spectacular demonstration

of the graphics technology in Mac OS X, and it can actually come

in handy when you find your icons shrinking away to

nothing.

Figure 2-16. To find a comfortable setting for the Magnification

slider, choose ![]() →Dock→Dock Preferences. Leave the Dock

Preferences window open on the screen, as shown here. After each

adjustment of the Dock Size slider, try out the Dock (which

still works when the Dock Preferences window is open) to test

your new settings.

→Dock→Dock Preferences. Leave the Dock

Preferences window open on the screen, as shown here. After each

adjustment of the Dock Size slider, try out the Dock (which

still works when the Dock Preferences window is open) to test

your new settings.

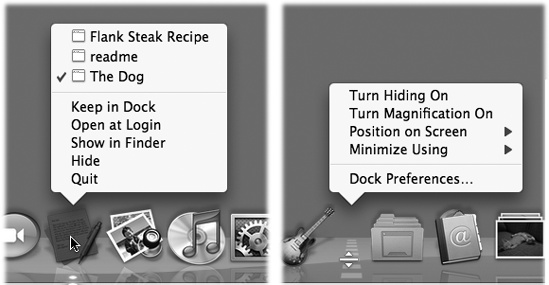

Yet another approach to getting the Dock out of your way is to rotate it, so that it sits vertically against a side of your screen. You can rotate it in either of two ways:

You’ll probably find that the right side of your screen works better than the left. Most Mac OS X programs put their document windows against the left edge of the screen, where the Dock and its labels might get in the way.

Note

When you position your Dock vertically, the “right” side of the Dock becomes the bottom of the vertical Dock. In other words, the Trash now appears at the bottom of the vertical Dock. So as you read references to the Dock in this book, mentally substitute the phrase “bottom part of the Dock” when you read references to the “right side of the Dock.”

Most of the time, you’ll use the Dock as either a launcher (you click an icon once to open the corresponding program, file, folder, or disk) or as a status indicator (the tiny, shiny reflective spot, identified in Figure 2-14, indicate which programs are running).

But the Dock has more tricks than that up its sleeve. You can use it, for example, to pull off any of the following stunts.

The Dock isn’t just a launcher; it’s also a switcher. For example, it lets you:

Jump among your open programs by clicking their icons.

Drag a document (such as a text file) onto a Dock application (such as the Microsoft Word icon) to open the former with the latter. (If the program balks at opening the document, yet you’re sure the program should be able to open the document, add the

and Option keys as you drag.)

and Option keys as you drag.)Hide all windows of the program you’re in by Option-clicking another Dock icon.

Hide all other programs’ windows by Option-

-clicking the Dock icon of the program

you do want (even if it’s already in

front).

-clicking the Dock icon of the program

you do want (even if it’s already in

front).

Each Dock icon has its own very useful shortcut menu (Figure 2-17). For example:

[Window names.] The secret Dock menu of a running program usually lists at least one tiny, neatly labeled window icon, like those shown in Figure 2-17. This useful feature means that you can jump directly not only to a certain program, but to a certain open window in that program—just as though you were using the Windows taskbar.

Keep In Dock/Remove From Dock. Whenever you open a program, Mac OS X puts its icon in the Dock—marked with a shiny, white reflective spot—even if you don’t normally keep its icon there. As soon as you quit the program, its icon disappears again from the Dock.

If you understand that much, then the Keep In Dock command makes a lot of sense. It means, “Hello, I’m this program’s icon. I know you don’t normally keep me in your Dock, but I could stay here even after you quit my program. Just say the word.” If you find that you’ve been using, for example, Terminal a lot more often than you thought you would, this command may be the ticket.

On the other hand, what if a program’s icon is always in the Dock (even when it’s not running) and you don’t want it there? In that case, this command says Remove From Dock instead. It gets the program’s icon off the Dock, thereby returning the space it was using to other icons. (You can achieve the same result by dragging the icon away from the Dock, but evidently too many Mac fans weren’t aware of this trick.)

Use this command on programs you rarely use. When you do want to run those programs, you can always use Spotlight to fire them up.

Open at Login. This command lets you specify that you want this icon to open itself automatically each time you log into your account. It’s a great way to make sure that your email Inbox, your calendar, or the Microsoft Word thesis you’ve been working on is fired up and waiting on the screen when you sit down to work.

To make this item stop auto-opening, choose this command from its Dock icon again, so that the check mark no longer appears.

Show In Finder. This command highlights the actual icon (in whatever folder window it happens to sit) of the application, alias, folder, or document you’ve clicked. You might want to do this when, for example, you’re using a program that you can’t quite figure out, and you want to jump to its desktop folder in hopes of finding a Read Me file there.

Hide/Show. This operating system is crawling with ways to hide or reveal a selected batch of windows. Here’s a case in point: You can hide all traces of the program you’re using by choosing Hide from its Dock icon. (You could accomplish the same thing in many other ways, of course; in Moving windows among screens.)

What’s cool here is that (a) you can even hide the Finder and all its windows, and (b) if you press Option, the command changes to say Hide Others. This, in its way, is a much more powerful command. It tells all the programs you’re not using—the ones in the background—to get out of your face. They hide themselves instantly.

Quit. You can quit any program directly from its Dock shortcut menu. (Finder and Dashboard are exceptions.) You don’t have to switch into a program in order to access its Quit command.

You might be thankful for this quick-quitting feature when your boss is coming down the hallway and the Dilbert Web site is on your screen where a spreadsheet is supposed to be.

Tip

If you hold down the Option key—even after you’ve opened the pop-up menu—the Quit command changes to say Force Quit. That’s your emergency hatch for jettisoning a locked-up program.

Sort by, Display as, View content as. If you right-click a folder on the Dock, you get a shortcut menu containing these three sections. They govern how the folder’s contents are listed in the pop-out display, as described in Three Ways to Get the Dock Out of Your Hair (grid, fan, or list, for example), and how they’re sorted.

Dock icons are spring-loaded. That is, if you drag any icon onto a Dock icon and pause—or, if you’re in a hurry, tap the Space bar—the Dock icon opens to receive the dragged file.

Note

It opens, that is, if the spring-loaded folder feature is turned on in Finder→Preferences.

This technique is most useful in these situations:

Drag a document icon onto a Dock folder icon. The folder’s Finder window pops open, so that you can continue the drag into a subfolder.

You drag a document into an application. The classic example is dragging a photo onto the iPhoto icon. When you tap the Space bar, iPhoto opens automatically. Since your mouse button is still down, and you’re technically still in mid-drag, you can now drop the photo directly into the appropriate iPhoto album or Event. You can drag an MP3 file into iTunes or an attachment into Mail or Entourage the same way.

Once you’ve tried stashing a few important folders on the right side of your Dock, there’s no going back. The folders you care about are always there, ready for opening with a single click.

Better yet, they’re easily accessible for putting away files; you can drag files directly into the Dock’s folder icons as though they were regular folders.

In fact, you can even drag a file into a subfolder in a Dock folder. That’s because in Leopard, the Dock’s folders are spring-loaded. When you drag an icon onto a Dock folder and pause, the folder’s window appears around your cursor, so you can continue the drag into an inner folder (and even an inner inner folder, and so on). Spring-Loaded Folders: Dragging Icons into Closed Folders has the details on spring-loaded folders.

Tip

When you try to drag something into a Dock folder icon, the

Dock icons scoot out of the way; the Dock assumes that you’re

trying to put that something onto the Dock.

But if you press the ![]() key as you drag an icon to the Dock, the

existing Dock icons freeze in place. Without the

key as you drag an icon to the Dock, the

existing Dock icons freeze in place. Without the

![]() key, you wind up playing a frustrating game

of chase-the-folder.

key, you wind up playing a frustrating game

of chase-the-folder.

At the top of every Finder window is a small set of function icons, all in a gradient-gray row (Figure 2-18). The first time you run Mac OS X 10.5, you’ll find only these icons on the toolbar:

Back, Forward. The Finder works something like a Web browser. Only a single window remains open as you navigate the various folders on your hard drive.

The Back button (◂) returns you to whichever folder you were just looking at. (Instead of clicking ◂, you can also press

-[, or choose Go→Back—particularly handy if

the toolbar is hidden, as described

below.)

-[, or choose Go→Back—particularly handy if

the toolbar is hidden, as described

below.)The Forward button (▸) springs to life only after you’ve used the Back button. Clicking it (or pressing

-]) returns you to the window you just

backed out of.

-]) returns you to the window you just

backed out of.Figure 2-18. If you

-click the upper-right toolbar button

repeatedly, you cycle through six combinations of large and

small icons and text labels. (Three examples are shown here.)

Tip: This same

-click the upper-right toolbar button

repeatedly, you cycle through six combinations of large and

small icons and text labels. (Three examples are shown here.)

Tip: This same  -clicking business cycles through the same

toolbar variations in Mail, Preview, and other programs that

have toolbars.

-clicking business cycles through the same

toolbar variations in Mail, Preview, and other programs that

have toolbars.View controls. The four tiny buttons next to the ▸ button switch the current window into icon, list, column, or Cover Flow view, respectively. And remember, if the toolbar is hidden, you can get by with the equivalent commands in the View menu at the top of the screen—or by pressing

-1,

-1,  -2,

-2,  -3, or

-3, or  -4 (for icon, list, column, and Cover Flow

view, respectively).

-4 (for icon, list, column, and Cover Flow

view, respectively).Quick Look. The eyeball icon opens the Quick Look preview for a highlighted icon (or group of them).

Action (

). This little pop-up menu contains the same

commands you’d see if you right-clicked something.

). This little pop-up menu contains the same

commands you’d see if you right-clicked something.Search bar. This little round-ended text box is yet another entry point for the Spotlight feature described in Chapter 3.

Between the toolbar, the Dock, the Sidebar, and the large icons of Mac OS X, it almost seems like there’s an Apple conspiracy to sell big screens.

Fortunately, the toolbar doesn’t have to contribute to that

impression. You can hide it by choosing View→Hide Toolbar or

pressing Option-![]() -T. (The same keystroke, or choosing View→Show

Toolbar, brings it back.)

-T. (The same keystroke, or choosing View→Show

Toolbar, brings it back.)

But you don’t have to do without the toolbar altogether. If its consumption of screen space is your main concern, you may prefer to collapse it—to delete the pictures but preserve the text buttons; see Figure 2-18.

You can drag toolbar icons around, rearranging them

horizontally, by pressing ![]() as you drag. Taking an icon off the toolbar

is equally easy. While pressing the

as you drag. Taking an icon off the toolbar

is equally easy. While pressing the ![]() key, just drag the icon clear away from the

toolbar. It vanishes in a puff of cartoon smoke. (If the Customize

Toolbar sheet is open, you can perform either step

without the

key, just drag the icon clear away from the

toolbar. It vanishes in a puff of cartoon smoke. (If the Customize

Toolbar sheet is open, you can perform either step

without the ![]() key.)

key.)

You can also get rid of a toolbar icon by right-clicking it and choosing Remove Item from the shortcut menu.

It’s a good thing you’ve got a book about Mac OS X in your hands, because the only user manual you get with Mac OS X is the Help menu. You get a Web browser-like program that reads a set of help files that reside in your System→Library folder.

Tip

In fact, you may not even be that lucky. In Leopard, the general-information Help page about each topic is on your Mac, but thousands of more nichey or more technical pages actually reside online, and require an Internet connection to read.

You’re expected to find the topic you want in one of these three ways:

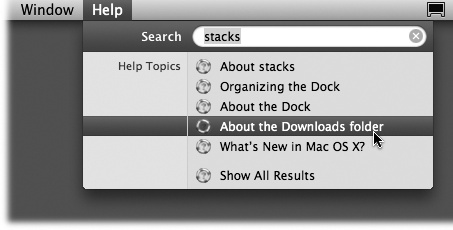

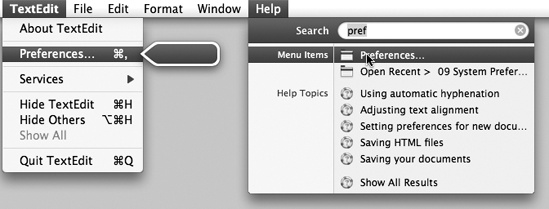

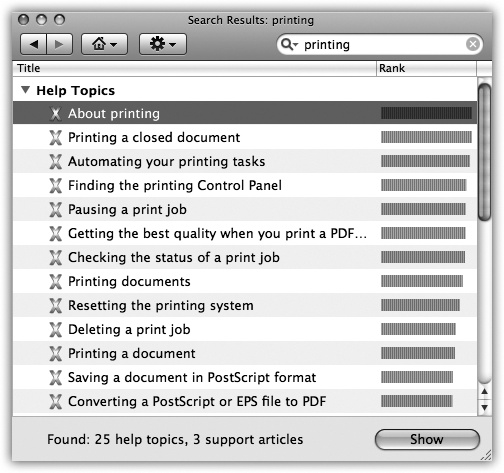

Use the new Search box. When you click the Help menu, a tiny search box appears just beneath your cursor (Figure 2-19). You can type a few words here to specify what you want help on: “setting up printer,” “disk space,” whatever.

Figure 2-19. In Leopard, you don’t have to open the Help program to begin a search. No matter what program you’re in, typing a search phrase into the box shown here produces an instantaneous list of help topics, ready to read.

The menu now becomes a list of Apple help topics pertaining to your search. Click one to open the Help browser described next; you’ve just saved some time and a couple of steps.

Tip

The results menu does not, however, show all of Help’s results—only the ones Apple thinks are most relevant. If you choose Show All Results at the bottom of the menu, the Help browser opens (described below). It shows a more complete list of Help-search results.

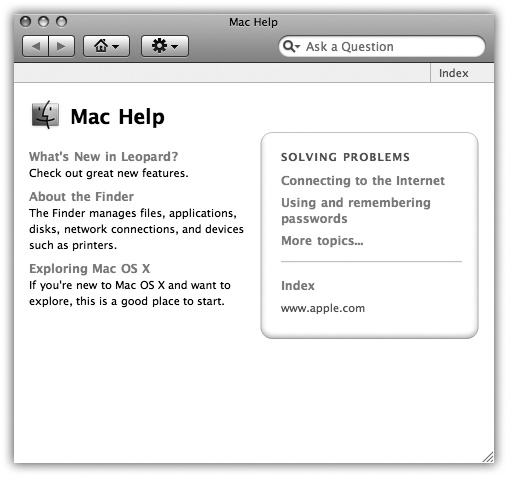

Drill down. Alternatively, you can begin your quest for assistance the old-fashioned way: by opening the Help browser first. To do that, choose Help→Mac Help. (This works only in the Finder, and only when nothing is typed in the Search box. To empty the Search box, click the

button at the right end.)

button at the right end.)After a moment, you arrive at the Help browser program shown in Figure 2-20. The starting screen offers several “quick click” topics that may interest you. If so, keep clicking text headings until you find a topic that you want to read.

You can backtrack by clicking the ◂ button at the top of the window. And you can always return to the starting screen by clicking the little Home icon at the top.

Figure 2-20. The Mac OS X Help system no longer bunches together the help pages from every program on your Mac. When you’re in the Finder, you get the general Macintosh help screens. When you’re in iPhoto, you get only iPhoto help screens. And so on. But using the Home pop-up menu, you can switch to another program’s Help system even if that program isn’t open.

Tip

Annoyingly, the Leopard Help window insists on floating in front of all other windows; you can’t send it to the back like any normal program. Therefore, consider making the window tall and skinny, so you can put it beside the program you’re working in. Drag the ribbed lower-right corner to change the window’s shape.

Use the “Ask a Question” blank. Type the phrase you want, such as printing or switching applications, into the Search box at the top of the window, and then press Return. The Mac responds by showing you a list of help-screen topics that may pertain to what you need (Figure 2-21).

This Search box usually gives you a more complete list of results than you’d have gotten by using the Search box in the Help menu, as described above.

Note

Actually, there’s one more place where Help has cropped up in Leopard: in System Preferences dialog boxes. Click the blue, circled question-mark button in the lower-right corner of each System Preferences panel to open a Help page that identifies each control.

Figure 2-21. The bars indicate the Mac’s “relevance” rating—how well it thinks each help page matches your search. Double-click a topic’s name to open the help page. If it isn’t as helpful as you 893 hoped, click the ◂ button at the top of the window to return to the list of relevant topics. Click the little Home button to return to the Help Center’s welcome screen.